MORAL RIGHTS AND FILMS ON TELEVISION

THE YEAR THAT Charlie Chaplin initiated his lawsuit against the imitator Charles Amador, Chaplin’s good friend and business partner, Douglas Fairbanks, launched a lawsuit of his own. Like Chaplin, Fairbanks used copyright law to increase American filmmakers’ power and control over their work. The Fairbanks case involved a few films that he made at the beginning of his movie career. In a contract with the Majestic Motion Picture Company, Fairbanks had included a provision stating that the legendary D. W. Griffith was to direct all of the films in which he appeared. Griffith did indeed proceed to work on—even if he did not direct—Fairbanks’s films for Majestic. After about a year, however, first Griffith and then Fairbanks left Majestic for new opportunities. Fairbanks’s star rose quickly in Hollywood, and his early films began to increase in value. Majestic’s owners decided to cash in on their early investment in the star. First they sold Fairbanks’s early films and all of their attendant rights to the Triangle Film Corporation. Then, in 1922, Triangle attempted to sell the Leader Company the right to reedit the films into two-reel serials.

Fairbanks immediately filed for an injunction to stop the Triangle-Leader deal. He had merely been an employee of Majestic when they made the original films, and he did not hold the copyrights. Fairbanks could not stop Majestic from selling the films to Triangle. But when Triangle attempted to license the right to reedit the films, Fairbanks argued that even though he was not the copyright owner, the new versions in the less prestigious two-reel, serial format would be “detrimental to [his] standing in his profession, in that he has never appeared in a two-reel picture, but has only appeared in feature pictures of five or more reels.”1

The panel of New York State Supreme Court justices who decided the case looked to Fairbanks’s original contract with Majestic for guidance. Although the contract failed to give Fairbanks any rights in the film, it did stipulate that Griffith was to direct the films, and, moreover, the contract gave Fairbanks the right to review the final cut of his films. A few decades later, lawsuits, contracts, and industry norms determined that final cut contracts govern the initial, theatrical release of a film but not subsequent theatrical, television, or video releases. In 1922, however, Fairbanks’s final cut case had virtually no judicial precedent, and there were no industry norms to invoke. Nevertheless, the court sided with Fairbanks and granted the temporary injunction. The judges decided that the contract perpetually protected Fairbanks’s artistic vision; he had the right to continue to oversee the aesthetic quality of his work even after the first theatrical run of his films.2

The judges who heard Fairbanks’s case did not offer much insight into their thought processes. They may have been responding to Fairbanks’s unusual position in the film industry. His career was a contradiction, an amalgam of art and commerce. Fairbanks was a global box-office star who made prestige movies. More importantly, Fairbanks had successfully fought for creative autonomy in the studio system. After leaving Majestic, Fairbanks started his own production company, and just a few years before launching his copyright case, Fairbanks—along with Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, and Mary Pickford—cofounded United Artists, a company that gave many filmmakers control over the distribution of their films. Fairbanks was thus emerging as an independent artist in the highly collaborative, commercial and, for many, still socially suspect medium of the movie.3

The year 1922 also proved to be a special year for film copyright. In addition to the Fairbanks and Chaplin cases, a third case involving artistic integrity in Hollywood was launched the same year. In this case, a New York court stopped a film company from using the name of the successful writer James Oliver Curwood to advertise a film adaptation of one of his stories, agreeing with Curwood that the film so transformed his story that it no longer resembled the original at all.4

Whatever the reason, the court chose to protect Fairbanks from the commercial machine of the Hollywood studio system, which always finds new ways to repackage its content. The Fairbanks case is largely forgotten, but it is perhaps the first to take on what would become one of the most important, lucrative, and complicated elements of the Hollywood studio system: the licensing of residual rights. In 1922 all but a handful of avant-garde and cult films seemed destined to be forgotten after their initial theatrical runs. But with the continuous cycle of new technologies from small-gauge home film formats to television to home video to the internet, the repackaging of films for new media has continually expanded the market for Hollywood and offered new outlets for old content.

Like Fairbanks, Hollywood filmmakers have continually seen themselves as casualties of the advance of technology and commerce. They made films for one format, and then their work was changed to suit the demands of another. In the 1920s only a few filmmakers like the United Artists founders saw themselves as having enough autonomy to demand that studios remain faithful to their creative products. With the rise of the auteur theory and the attendant restructuring of the studio system in the 1960s, however, things changed. Studios gave directors increased artistic control, and they began to market directors as the sole creators behind the highly collaborative and complex process of making movies. Directors then started to view themselves as a new breed of artist whose work requires unprecedented protection against the perceived threat of new media. They launched a campaign in courts and in Congress to prevent truncated, colorized, low-resolution, or otherwise manipulated versions of their work from being distributed. And, I argue, the larger discourse of auteurism slowly began to infiltrate both the language of court decisions and the design of proposed legislation. Eventually we ended up with a regime in which film directors and even the studios themselves have been cast as victims of new media rather than, as has historically been the case, its greatest beneficiaries.

While we have many accounts of the rise of the idea of Romantic authorship and its impact on copyright law since the eighteenth century, we do not yet have a persuasive narrative about how U.S. copyright law came to treat Hollywood directors as a special category of artistic geniuses. Indeed, we still need to recognize that directors have historically been given greater protection than their counterparts in other media. It is no coincidence that the majority of U.S. cases involving the potential for moral rights (a concept and doctrine discussed below) have involved films and filmmakers. This expanded protection for Hollywood directors is a far stranger phenomenon than protections offered to novelists and playwrights. While few books or plays are written entirely in cultural and physical isolation, studio filmmaking is a highly collaborative process that requires an elaborate financial and industrial infrastructure. Moreover, the vision of a film director as an individual creator is a myth that has been perpetuated largely by the studios. American auteur cinema began as a way of competing with the popularity of European and independent films in the 1960s, and by the 1980s it had become a full-blown marketing strategy, akin to the star system. In the United States, auteurism is a phenomenon that the Hollywood studios never fully lost control over, and, as we will see below, studios have won just about every battle over film authorship. At moments in this battle for expanded rights, the studios may have briefly lost some control over auteurs like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, but in the end the rise in protection for film directors has served largely to increase studio control over new media.5

WHAT ARE MORAL RIGHTS?

Before looking at film directors’ campaign for expanded rights, it is necessary to describe the kinds of rights they sought. To put it simply, as the auteur theory moved from Europe to the United States, American film directors wanted the same legal rights as European directors. This is a goal that should have been impossible, because European and U.S. copyright law are built on very different foundations. Both the Continental European and Anglo-American copyright traditions emerged out of the same concern: how to protect individual creations without hampering the free flow of ideas. And until the late nineteenth century, as Jane Ginsburg has shown, Continental and Anglo-American law continued to reflect similar social and judicial ambivalence about reconciling these goals. In the end, however, the two traditions diverged sharply.6

Since the first U.S. Supreme Court copyright decision, Wheaton v. Peters (1834), American law has treated copyright as the artificial creation of governments. Copyright is an ingenious bargain devised by legislators and courts. It rewards authors and artists with a limited monopoly on their expression in order to provide an incentive for producing culture and knowledge in the first place. Once the limited time period ends, however, the work enters the public domain and becomes the property of society. From the perspective of U.S. copyright law, authors and artists do not possess any natural or inalienable connection to their work; they only have the rights bestowed on them by Congress.

A number of provisions of U.S. law serve to dissociate the creator and the copyright, reinforcing both the artificiality and fleetingness of copyright.

Under the “work for hire” doctrine, for example, companies often hold the copyrights to their employees’ creations.7 Under this doctrine, employers are legally the “authors” of their employees’ work. Most film copyrights, for example, are held by studios or production companies, which become the corporate authors. Fairbanks’s films were works for hire made for the Majestic Company, the copyright owner and author.

Not only can employers rather than the creators hold copyrights, but, in addition, a copyright holder may sell the copyright in his or her work to someone else, making a copyright merely another transferable commodity. The Majestic Film Company, for example, sold all of the rights in Fairbanks’s films to Triangle. Triangle then attempted to license some rights to the Leader Company.

In the United States, an author may also forgo copyright’s protection and rewards entirely by dedicating a work to the public domain. Before the 1909 Copyright Act, U.S. authors had to actively seek a copyright by registering their work with the U.S. Copyright Office. The default status of all works, in other words, was as part of the public domain. After the passage of the 1909 Act, creators still needed to affix a copyright notice to their work, and since the 1976 Act, all work is automatically protected by copyright if it meets the basic criteria. But creators may still use licenses to give away some or all of their rights in the work.8

These facets of the law reinforce the fact that U.S. copyright exists as a legal construction that can be bought, sold, traded, or dissolved. There is nothing natural, inevitable, or obvious about copyright—at least not in the Anglo-American tradition. It is based on the market-driven and culture-driven theory that rewarding authors and artists is valuable because it benefits society. In the end, however, all work is made for and eventually belongs to society at large.

French copyright law, in particular, and Continental copyright law more generally have been built on a different philosophical foundation. French law assumes that creative work flows from the personality of its creator. As a result, creators of copyrighted work retain some control over their work even after the economic rights have been given away. French law separates the economic rights from natural or moral rights (droit moral). Moral rights have nothing to do with morality. Instead, in this context, the term moral rights refers to a bundle of additional rights given to the creator of a work. Moral rights include “(1) the right of paternity, i.e. the right to be identified as the author of the work; (2) the right of integrity, i.e. the right to object to derogatory treatments of a work; (3) the right of divulgation or of dissemination, i.e. the right to decide when and how a work should be made public (including the right not to make it public); and (4) the right … to withdraw a work from commerce.”9 In the moral rights tradition, commerce and social benefit are ultimately secondary to the author’s or artist’s sacrosanct right to protect his or her creation and reputation. (A cynic might note that reputations often hold economic value as well, and it is difficult to separate moral from pecuniary rights.) When Douglas Fairbanks argued that the reediting of his films would damage his reputation, for example, he invoked the equivalent of the right of integrity. The reediting of his films, he insisted, would have damaged his reputation and gone against his intentions in making the films. The judge in the case effectively created the right of integrity for Fairbanks by finding it hidden or implied in Fairbanks’s contract.

As the Fairbanks case suggests, the United States has not entirely eschewed moral rights or denigrated the status of authors and artists. U.S. law protects many of the rights contained in the moral rights bundle through related legal doctrines like libel, slander, privacy, unfair competition, and misrepresentation (known as passing off). Contracts can also be used to protect authors’ rights, and in 1990 the United States adopted limited moral rights in the Visual Artists Rights Act, which excludes motion pictures. It would be too easy to oppose moral rights and U.S. copyright. What we find when we look at the legislative history and case law surrounding moral rights for filmmakers is that policymakers and judges have consistently been swayed by filmmakers’ pleas for moral rights. Over and over again, courts and Congress have come to the brink of adopting moral rights for filmmakers. But, in the end, the interests of the studios have always prevailed.

CONGRESS AND HOLLYWOOD’S ROCKY RELATIONSHIP WITH MORAL RIGHTS IN THE 1930S

The Fairbanks decision came at a time when Congress was divided about moral rights and about the role of copyright in fostering international trade, two issues that have been integrally linked. Copyright and international trade policies have remained in tension largely because of the irreconcilable foundations of Anglo-American and Continental copyright law.

U.S. copyright law has always—perhaps not surprisingly—been geared toward the protection of national interests. The first U.S. Copyright Act of 1790 limited its benefits to American citizens or residents, and the law was not updated to allow foreign authors to copyright their works until 1891.

What many European authors saw as state-sanctioned piracy prevented the United States from entering the international copyright agreement, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, when it was first ratified in 1886. After a later revision in 1928, the member states placed pressure on the United States to join the Convention. The 1928 agreement, however, contained a significant impediment for the United States: at the suggestion of the French delegation, it included a moral rights provision.10

Throughout the 1930s, Congress wavered about whether or not to join the Berne Convention. Two U.S. presidents and the Register of Copyrights, Thorvald Solberg, pushed for Berne membership, and between 1930 and 1941 at least seven separate bills proposed that the United States enter into the agreement. Hollywood’s leaders paid close attention to Congress’s deliberations, and both the studios and the talent guilds took part in the debates over Berne membership and the adoption of moral rights in the United States.

When the issue of joining the 1928 convention came before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, President Herbert Hoover enthusiastically expressed his support for joining. Although the bill under consideration never made it past the committee stage, a few years later the House of Representatives passed another piece of legislation, the Vestal Bill, that again called for the United States to join the Berne Convention. The Vestal Bill contained a number of provisions that would have harmonized U.S. copyright law and Continental law. The bill would have required the United States to eliminate its registration requirement, making all eligible works automatically protected by copyright at the time of their creation. The bill would also have extended the term of copyright to fifty years after the author’s death.11

The Hollywood studios were integrally involved in the drafting of the Vestal Bill, and they supported both joining Berne and introducing moral rights into U.S. copyright law. The Vestal Bill, however, lost support in the Senate after a Democratic senator from Washington State, Clarence Dill, denounced it as un-American. Harmonization with the Berne Convention, after all, would have dramatically transformed U.S. copyright law and brought it much closer to European law. It would not be the last time that moral rights would be accused of being un-American.12

Congress’s interest in moral rights did not end with the Vestal Bill, however. In 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt initiated a new move to join the Berne Convention when he sent the text of the agreement to the Senate, asking that they consider ratifying it. Over the next few years, the Senate ordered studies of the issue and considered a number of drafts of a bill proposed by Senator F. Ryan Duffy, a Democrat from Wisconsin. Just a few years after the Vestal Bill, Hollywood now opposed the Duffy Bill, Berne membership, and moral rights.

Why did the studios change their position on Berne and moral rights? During the brief period between the two bills, many European countries had adopted strict tariffs and quotas on U.S. film imports, and Hollywood moguls argued that they had little to gain by entering into an agreement with European regulators who had grown increasingly hostile to the American film industry. The Duffy Bill also contained a number of exemptions for charitable organizations, broadcasters, and others, which all corporate copyright holders seemed to oppose uniformly. The biggest controversy in Hollywood, however, surrounded the congressional testimony of screenwriter John Howard Larson, future member of the Hollywood Ten. Testifying on behalf of the Screen Writers Guild, Larson delivered a stirring indictment of the treatment of writers in Hollywood. Larson garnered a lot of press, and his picture of the plight of writers seemed to suggest that screenwriters supported the adoption of moral rights. In theory at least, moral rights legislation might have proven to be a boon to screenwriters if it allowed them to control their work after it fell into the hands of producers, who were only interested in the bottom line. But Larson had not been briefed on all of the details: the Duffy Bill contained a specific exemption that would have permitted studios to alter scripts without violating the moral rights of writers. Only a few days after Larson appeared before Congress, the Screen Writers Guild sent a follow-up letter to the Senate clarifying that it was now opposed to the Duffy Bill.13 Without the support of Hollywood studios, screenwriters, and rights holders from other industries, the Senate indefinitely deferred the Duffy Bill.

The legislative skirmishes of the 1930s proved the incompatibility of moral rights and the Anglo-American tradition. American copyright law is based on statutory compromise and the idea that copyright is a negotiable commodity. Moral rights emerge from a fundamental belief in the inalienable rights of artists. Once those natural rights become subject to negotiation and compromise, they necessarily dissipate.

The Hollywood studios have supported harmonization with international copyright law when they successfully negotiated exceptions that benefited their industry. In 1939, just for example, the studios reconsidered the advantages of moral rights on their own terms, and they sent a delegation to a meeting of Berne members. The Hollywood representatives argued that film producers and not directors should be considered the rightful film authors, and producers should hold moral rights in film. In the collaborative and industrial medium of film, after all, it is far from obvious who authors a film. But Hollywood’s occasional support for moral rights legislation is the exception. More often, the studios have opposed harmonization, seeing it as a potential threat to their reliance on corporate ownership. 14

SCREEN CREDIT AND THE COLD WAR

John Howard Larson’s turn toward moral rights as a panacea for the mistreatment of writers in Hollywood portended the desperate situation for writers and other artists during the Cold War. During the era of the blacklist, in particular, credit for work on films became a highly contentious subject. Many blacklisted film writers, actors, and directors found their names removed from films they had worked on and were proud of. On occasion, debates about film credit were taken to court, but writers and the leaders of the talent guilds soon learned that suspected communists had trouble winning the sympathies of U.S. courts.15

One significant dispute about screen credit during the early years of the Cold War involved a court battle over moral rights. The case involved four of the most famous and accomplished Soviet composers, Dmitry Shostakovich, Sergey Prokofiev, Aram Khachaturian, and Nikolai Myaskovsky. Where blacklisted writers wanted credit for their work, the Soviet composers feared that having their names on a film would suggest that they were also responsible for, or at least sympathetic to, the film’s ideological messages. With a blacklist in force in Hollywood and an active Stalinist culture ministry in the Soviet Union, such fears were more than justified.

In particular, the Soviet composers opposed the use of their names and music in the William Wellman–directed defection drama Iron Curtain (1948). Head of the Twentieth Century-Fox music department, Alfred Newman, used public domain compositions of Soviet composers throughout the film, both as incidental music on the score and within the story. The credit sequence also listed the names of the four Soviet composers. Fox released Iron Curtain just one year after the Hollywood Ten appeared as hostile witnesses before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Everyone in Hollywood was fearful of being involved in a film sympathetic to communism or the Soviet Union. But Newman does not seem to have known the stakes of his musical choices in this explicitly anticommunist picture. Although none of the four Soviet composers were working in

Hollywood, their careers were all on the line back in the Soviet Union, and one can understand their desire to protect their reputations. Shortly before the release of Iron Curtain, Communist Party official Andrei Zhdanov led a purge of antirealist, formal experimentation in Soviet music. The four composers Newman had selected for the soundtrack were all condemned for their allegedly anti-Soviet compositions, and the appearance of their compositions in Iron Curtain added fuel to the fire.16

The composers are unlikely to have seen the film, and it is not known if the composers initiated the case themselves or if Stalin’s government launched the case in their names; the latter is more likely. Either way, the complaint claimed that the use of the composers’ names and music in the film suggested that they endorsed Iron Curtain’s clear anticommunist message.17

When New York State Supreme Court Justice Edward R. Koch, who wrote the decision, came to the moral rights claims of the composers, he relied almost entirely on a speculative law review article, since moral rights case law in the United States was so thin. Koch conceded that the existence of moral rights in U.S. copyright law was unclear. If moral rights did exist, he wondered, what kind of test would be used to measure when they had been violated: “good taste, artistic worth, political beliefs, moral concepts …?” Koch entertained the idea that works in the public domain might still be subject to the terms of moral rights, although other aspects of copyright law no longer pertained. The problem in this case, Koch explained, is that the Soviet composers had not invoked moral rights properly. They did not claim, for example, that Newman’s score for Iron Curtain distorted their work; a significantly altered composition might have been a violation of the composers’ rights of integrity. And they did not claim that the work had been incorrectly attributed to them, which might have been a violation of the right of paternity. Instead, the composers feared that audiences would connect them with the film’s message. Justice Koch, however, believed that audiences would not assume a line in the musical credits amounted to an endorsement of the political or ideological bent of a film, and he could not see how the use of the composers’ music interfered with their moral rights, whether or not those rights existed in the United States. Koch escaped having to decide how to apply the doctrine of moral rights although, significantly, he acknowledged that such rights might be applicable to U.S. copyright law.18

The Soviet composers also sued Fox in French court, and there they won their moral rights claim, successfully preventing the continued distribution of the film in France. In the high-stakes political climate of the Cold War, French courts were willing to allow artists to use moral rights to control the public perception of their political sympathies. The Soviet composers’ case further suggests some of the potential power of moral rights arguments and why they have been invoked so frequently in film cases. In the politically suspicious and intolerant climates of Cold War America and Stalinist Russia, reputation was too important to leave in others’ hands. Moral rights promised to give individual artists some control over their names and works when the copyrights belonged to corporations or the work had entered the public domain. Even when the political stakes have been less dramatic, artists have looked to moral rights for some foothold in the collaborative and commercial world of Hollywood.19

SPONSORSHIP AND THE TELEVISION FRONTIER

Although moral rights did not emerge as a weapon in the reputation battles of the Cold War, they did become important in the commercial sphere, especially after the advent of television. The repackaging of films for television (and later home video) proved to be the flash point for the conflict between filmmakers who wanted to preserve the integrity of their films, and Hollywood studios, which wanted to make money by reediting films for the small screen. But Hollywood did not embrace television all at once, and it took time for actors, directors, and studio heads to negotiate the new territory of television exhibition. Moral rights surfaced as a key term in the negotiations.

As Marshall McLuhan famously noted, “the content of any medium is always another medium.”20 And so the enormous backlog of films in studio vaults should have been the natural content pool for early television. A number of factors, however, held the major studios back from releasing their films to television. At first, the studios treated television as competition rather than as a new outlet for films. Theater owners exacerbated the sense of competition by exerting enormous pressure on Hollywood not to upset their long-standing distribution contracts. Another reason that studios held off on releasing films to television is that many film industry leaders hoped that another financial model, such as subscription television, might win out over sponsored advertising. Studios also resisted the lure of television, because the networks were not in a position, at least at first, to offer sufficiently enticing sums for film broadcast rights. A final block in the road to releasing films to television were the negotiations with “talent”—the actors, directors, writers, and musicians—who all wanted and deserved compensation for the rerelease of their work. The talent had, of course, been paid for their contributions to the initial films, but how should they be compensated for the broadcast of their work in this new medium?21

One by one, all of the barriers preventing Hollywood from embracing television began to fall, and studios started to produce material for the small screen. Network prices for films shot up. And through collective bargaining agreements, all of the talent guilds and licensing societies eventually arranged for residual rights to be paid to their members for television exhibition of their work. But compensation was not the only labor issue that stood in the way of Hollywood’s releasing its films to television. Many film stars and directors shared Douglas Fairbanks’s concerns about the impact of reedited or otherwise manipulated versions of their work being prepared for display in a new medium or format. In the case of television, the medium came with a new economic model as well: sponsored advertising. And film talent worried about the interspersing of product pitches during their films.

Since the invention of television, film writers, actors, and directors have used the copyright doctrine of moral rights to assert—or at least attempt to assert—control over the use of their work on television. Screen cowboys Roy Rogers and Gene Autry blazed the trail. Rogers and Autry were the reigning cowboy film stars in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, and they both made their careers at the independent Republic Studios, which specialized in B-grade westerns, action films, and serials. While the major studios held on to their films, the small Republic studio began releasing films to television as early as 1948. But when Republic announced that it was releasing Roy Rogers’s film to television, “the King of the Cowboys,” as Rogers was known, protested. He was not motivated entirely by a reverence for his original big screen masterpieces; the future of his career was at stake as well. In 1951, The Roy Rogers Show premiered on television, and Rogers viewed the Republic films as potential competition. Rogers’s lawyers drew on contract law, advertising law, and the emerging legal field of publicity rights to stop Republic from selling the television rights. The lawyers argued that showing the films with sponsored advertising amounted to Roy Rogers’s endorsement of the products advertised, and Republic needed Rogers’s permission for that kind of promotion.22

Television was still relatively new, and the models for translating one medium, film, to another, television, were just being worked out. Taking a first stab at the issue, California trial and appeals courts sided with Rogers. The courts awarded Rogers a permanent injunction, halting the sale of his films to television. The courts decided that Republic needed Rogers’s permission to license his films for airing on television with commercials. As the New York Times reported, after the Roy Rogers cases sponsors began to back away from supporting old films released to television, fearing that other actors would join Rogers’s crusade.23

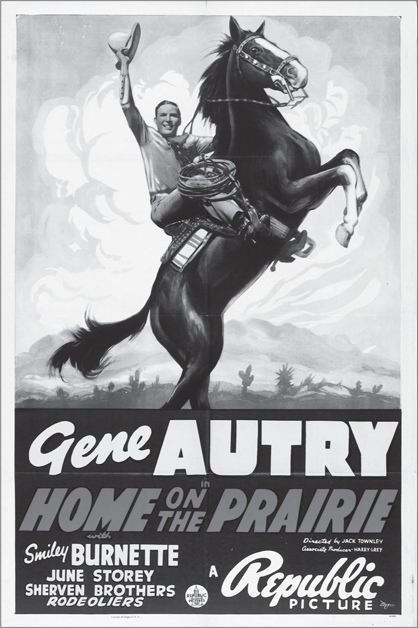

In October of 1951, Gene Autry (fig. 3.1) realized the sponsors’ fears, and he filed his own suit against Republic. Like Rogers, Autry had a television show, and he reiterated Rogers’s successful complaints about sponsorship. Autry added some new claims as well. Autry invoked moral rights, claiming that the pruning of his feature films to fifty-three minutes for airing with commercials in a one-hour television slot violated the integrity of his work.24

The judge who first heard Autry’s case saw the issue differently from the judges who decided the Roy Rogers case. Judge Benjamin Harrison took Autry’s suit very seriously, as one of those special cases that had the potential to determine the future of a new medium. “This case,” he wrote, “presents one of the many questions constantly arising as a result of the impact of television upon the entertainment world.” On the question of whether or not showing a film on television with advertisements required additional permission from the stars, Judge Harrison disagreed with the Rogers decision. Showing advertisements during a film, Harrison observed, was no different than displaying advertisements in a theater in which a film was shown. No one asked the actors’ permission to display a candy ad in the theater lobby while their film was shown inside. Why should stars be allowed to control the advertising that interrupted their films on television?25

The conflicting Rogers and Autry decisions led to confusion in Hollywood, and negotiations between television networks and studio heads over the release of films to television stagnated.26 The Ninth Circuit heard both the Rogers and Autry cases on appeal. On the same day in 1954, the Ninth Circuit decided both cases, and in its decisions the court paved the way for Hollywood to release films for television. Writing for the court, Judge Homer T. Bone cemented the Autry decision: Republic did not need the actors’ permission either to edit their films for television or to release the films to be shown with advertising. But Judge Bone was both a former Socialist Party member and a former senator with a reputation as a corporate watchdog. In his decision, Bone left the door open for future artists to use moral rights claims in order to assert their rights in the face of corporate abuse. Republic had merely cut the films down to fifty-three minutes to be shown with seven minutes of commercials. In this instance, according to the court, Republic had not gone too far. But, Bone warned, “cutting and editing could result in emasculating the motion pictures so that they would no longer contain substantially the same motion and dynamic and dramatic qualities which it was the purpose of the artist’s employment to make.” He warned further that “we can conceive that some such exhibitions could be so ‘doctored’ as to make it appear that the artist actually endorses the products of the programs’ sponsors.”27

FIGURE 3.1 Gene Autry fought Republic Pictures for control over the integrity of his films after they were edited for television.

Bone’s choice of words is telling. Both his fear of an “emasculated” work of art and of a film “doctored” to change its relationship to the advertising suggest a view of intellectual property as an extension of one’s body. The foundation of at least one common view of intellectual property, derived from seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke, holds that the right of personal property stems from our relationship with our bodies. We own and expect control over our bodies, and, by extension, we expect the same rights over our personal property and possessions. The expansion of this perspective to intellectual property underlies the doctrine of moral rights as well. If intellectual property is a natural extension of one’s body, then it is truly brutal to separate creative work from its maker. This Lockean theory of property continually resurfaces in both American jurisprudence and American culture more broadly, despite the fact that it contradicts the legislative bargain of Anglo-American copyright. And by linking moral rights in film with Lockean property theory, Judge Bone established the judicial formula that would eventually lead to the expansion of moral rights for filmmakers.28

After the Ninth Circuit’s decision, the Los Angeles Times joked that television viewers should not “be surprised if Roy Rogers or Gene Autry [came] up sponsored by the makers of such feminine things as perfume.”29 Like Bone, though in a different sense, the Times reporter feared that advertising might prove a threat to the masculinity of the screen cowboys. But the Ninth Circuit’s decision proved to be prescient: audiences do not assume that the actors in a particular film endorse the products advertised during its televised showing any more than they assume that a composer endorses the ideological message of a film in which his or her music is used.

With moral rights temporarily in check, film studios were free to release their films to television without fear of interference from actors or directors. As a result, Republic stopped making new films and its primary business became licensing its old films for television. And just a few months after the conclusion of the Rogers and Autry cases, the major Hollywood studios joined Republic and began releasing their backlogs of films to television networks as well. Although moral rights is rarely, if ever, mentioned in the history of the Hollywood studios’ release of films to television, the decision over Gene Autry’s assertion of moral rights was clearly a pivotal event in that history.30

AUTEURISM COMES TO AMERICA

Hollywood’s embrace of television was just one element of a larger trend toward conglomeration and consolidation. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, every Hollywood studio was either acquired by a large multinational conglomerate or became a diversified communications company on its own. Television distribution, and eventually cable, home video, and internet distribution, all became part of the regular life of a feature film.31

At the same time that Hollywood increased its profits by exploiting new media, however, the films themselves began to lose touch with American and international audiences. A series of financially successful independent films in the late 1960s like Easy Rider (1969), European art films like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), and soft-core pornography like I Am Curious Yellow (1969) showed Hollywood executives that they were failing to reach the growing audience for films with mature subject matter.32

The studios responded to their crisis by giving much more control—both creative and financial—to individual filmmakers. On the one hand, the new power given to directors emulated the model of the European cinemas, which were gaining a foothold in American and international markets. Pioneered by the French New Wave’s call for an author-oriented cinema, the European art-house circuit celebrated a gallery of great directors, from François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard to Ingmar Bergman and Satyajit Ray.

On the other hand, the new economic power given to individual filmmakers resulted from the transformation of the studio system. Ever since the separation of exhibition from production and distribution after the 1948 Supreme Court order, aka the Paramount Decision, Hollywood studios had been moving toward a leaner, blockbuster-driven production model. Studios comprised of stables of writers, actors, directors, and editors seemed cumbersome and bloated. The studios became primarily distributors for films made by independent production companies. In the 1950s, some of the most successful Hollywood directors, like John Ford and Fritz Lang, set up their own independent production companies, and they cut deals with the studios to distribute and often fund their films. In the 1960s, the studios set up a generation of film-school graduates with similar deals. Warner Bros., for example, gave Francis Ford Coppola the seed funds to start his American Zoetrope company, which produced such director-driven films as George Lucas’s THX1138 (1971) and Coppola’s own Apocalypse Now (1979). Universal entered into a distribution deal with BBS, the production company that made Easy Rider. And Paramount started the appropriately named Directors’ Company to finance the films of Coppola, William Friedkin, and Peter Bogdanovich.

The new model of the autonomous director-general in charge of the creative and commercial elements of a production coincided perfectly with the Americanization and popularization of the auteur theory in the 1960s. French critics writing for the film journal Cahiers du cinéma first elaborated the politique des auteur in the post–World War II period. They described the ability of select directors—John Ford or Howard Hawks—to infuse films with an individual worldview, despite the collaborative, factory-like system of Hollywood. The French critics then turned to filmmaking and built on their understanding of auteurism, with its focus on individual expression and creative autonomy. American film critic Andrew Sarris began to translate the politiques des auteurs for American readers in the 1960s. After a series of articles in the journal Film Culture, Sarris published his book on the auteur theory in 1968, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929–1968. The idea rapidly penetrated both American culture and Hollywood, and both studios and critics had a name for the new model of studio production: auteurism.33

The two cultures of the New Hollywood—the complex commercial machine bent on repackaging films for new media and the director-driven system of semi-independent production—were on a collision course. Moral right would be at the center of coming conflicts between directors and studios.

AUTEURISM ON TRIAL

Two of the early star directors and studio-supported independents, Otto Preminger and George Stevens, were the first to test moral rights in the nascent auteur culture. Preminger and Stevens both became marquee-worthy director-producers in the 1950s. Los Angeles Times gossip columnist Joyce Haber once remarked about Preminger that “his name in an ad or on a marquee is more familiar to moviegoers than those of all but our giant performers.”34

In 1965, both Preminger and Stevens decided to take a stand against the display of films on television, resuming the battle that Autry and Rogers had begun. Preminger and Stevens, however, were not worried about their films being used to endorse products. They feared that commercial interruptions and the shortening of films for television would destroy the integrity of their carefully crafted works of art. In other words, they wanted moral rights protection against Hollywood’s manipulation of films to meet the demands of the new medium.

In the 1950s, Preminger made a series of critically successful films for his own independent company, Carlyle Productions. The outspoken Preminger publicly railed against the showing of films on television, referring to commercial interruptions as “scandalous, barbaric, awful.” He boasted that he successfully withheld his films The Moon Is Blue (1953) and The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) from TV, although the explicit treatment of sex and drug addiction in those films made them unlikely candidates for television in the first place. When Columbia Pictures licensed Preminger’s 1959 masterpiece Anatomy of a Murder to be aired on ABC, Preminger opposed the sale in court. Preminger had a final-cut contract, but by this point, industry norms and court decisions had made clear that final cut did not preclude editing for television. Columbia and its TV subsidiary, Screen Gems, had acquired the television rights to the film, and Preminger’s claim rested on his moral rights assertion, though he did not use that phrase explicitly. Preminger argued that the editing of his film for television would “(a) detract from the artistic merit of Anatomy of a Murder; (b) damage Preminger’s reputation; (c) cheapen and tend to destroy Anatomy’s commercial value; (d) injure plaintiffs [Preminger and Carlyle Productions] in the conduct of their business; and (e) falsely represent to the public that the film shown is Preminger’s film.” If this were a French court, Preminger could have claimed that his rights of integrity and attribution had both been violated. Borrowing the bodily language from the Autry case, Preminger described the edited version of his film as “mutilated.”35

Working with very little time, the New York State Supreme Court issued a temporary injunction, and ABC aired Anatomy of a Murder without commercials in Los Angeles and Chicago. But when the court heard the case again with more time to deliberate, Preminger lost. Justice Arthur Klein reached a conclusion similar to the Ninth Circuit’s decision in the Autry case. If Preminger’s 161-minute film had been cut to 100 minutes, as ABC’s brochure had falsely advertised, Klein decided, “such cuts would not be minor and indeed could well be described as mutilation.” But ABC’s cuts were less extensive, so he allowed the edited and interrupted version to be shown. Across the country, in California, George Stevens’s very similar case—involving the films A Place in the Sun (1951), Something to Live For (1952), and Shane (1953) (fig. 3.2)—ended with a similar conclusion.36

It is strange that Judge Bone in the Autry case and Justice Klein in the Preminger case both considered the amount of material cut from the original film to be the single factor that determined whether or not the integrity had been compromised. A much more valuable test would have been whether the quality or impact or aesthetic importance of the original had been compromised. Quantitative measures can only go so far in assessing the “mutilation” of an original. Eliminating a few key moments can transform a work. On the other hand, more lengthy deletions might have little effect. The numbers of minutes cited in the two cases appear almost arbitrary. A 53-minute Autry movie is acceptable; a 100-minute Preminger movie is too short. The arbitrariness of these assertions suggests that these judges were not willing to take on the aesthetic evaluation necessary to oversee the stewardship of moral rights, although they were willing to lay the groundwork and necessary precedent for subsequent decisions to take advantage of moral rights.

FIGURE 3.2 Shane (1953)—“mutilated” by TV editing?

Not only did courts and the press regularly discuss reediting of films for television as “mutilation” and “dismemberment,” but the public, now tutored in the auteur theory, was starting to use the same language of bodily harm. Both the judge who decided the Stevens case and an allegedly random television viewer from Reseda, California, who was interviewed by the Los Angeles Times, used the same word to describe the editing of films for television: “emasculation.” It is also the word that Judge Bone had used in the Autry case, and with its popularization and formalization in court decisions, the reediting of films for television took on violent, gendered connotations, in addition to absorbing Lockean property theory.37

The Preminger and Stevens cases sent ripples through the film and television industries. The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) began to fear an uprising of auteurs, possibly supported by the public. In 1965, while both the Preminger and Stevens cases were under way, NAB executive Howard Bell recommended to the NAB board that they “establish some standards on frequency and placement of commercial messages” for use when showing “certain types of movies.”38 The NAB waited for the cases to be resolved, however. When the courts effectively stopped the auteurs’ revolt, the NAB decided not to change their methods of sponsorship.

Responding to the Stevens and Preminger cases, director Mervyn LeRoy explained the stakes of the cases for Hollywood directors. LeRoy had been directing high-profile studio movies since the 1920s, including Little Caesar (1931), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), The Bad Seed (1956), Gypsy (1962), and an uncredited directing stint on the Wizard of Oz (1939). Unlike Preminger and Stevens, however, LeRoy was willing to meet the new technology halfway. For example, he helped advertise the television showing of his film Quo Vadis (1951), even though it had thirty-three commercial interruptions. He even expressed a willingness to help edit his films down for television if anyone asked. What was most important to LeRoy was attribution—the assurance that people saw the films and knew who directed them. “A man makes something like a Mervyn LeRoy production,” he explained, “and when its television showing is advertised, they leave out the names of the producers and directors…. I worked for years on Quo Vadis, and I want people to know who made it.”39 LeRoy and many other filmmakers feared losing credit for their work as much as they feared assuming credit for lesser versions of their films. In both scenarios, moral rights would have helped the handful of concerned directors. But, as responses from the studios and television networks make clear, moral rights law would also have hampered or at least complicated the sale of films to television.

In all of the early television cases involving moral rights, the courts chose to nurture the new medium of television by protecting studios’ rights to license new versions over individual directors’ rights to protect their artistic vision. Of course, Hollywood directors had been on the other end of the equation for years—fending off complaints that their films destroyed great works of literature. The irony was not lost on everyone. An opinion piece in the New York Times pointed out that Hollywood directors generally responded to such claims by explaining that film is an entirely different medium. But the same directors who liberally adapted novels, like Preminger and Stevens, now sought to stop the new medium of television from tarnishing their work. “Suddenly,” the Times piece accused, “[Hollywood directors] have become worshipers at the shrine of art—their own.”40

From one angle, moral rights are simply a contract issue. Neither individual directors nor the Directors Guild of America were powerful enough to demand perpetual artistic control of their work, so they hoped that the law would recognize an inalienable natural right to control their art; they hoped that moral rights would make up for their lack of negotiating power. After the many reversals in the Rogers, Autry, Stevens, and Preminger cases, however, Hollywood began to solve the issue of television editing and commercial interruptions as they had solved most copyright problems: through contracts and labor guild policies. Hollywood, in other words, kept the problems in-house and out of the courts. Directors and other film talent were required to sign contracts explicitly waiving television rights, even when the contracts gave directors final say in the editing of the theatrical release, i.e., final cut. Standard industry contracts also began to reserve for the studios the right to adapt films infinitely into the future, for “devices not yet invented or imagined,” as contracts started to read.41

The invention of the pseudonym Allen Smithee (with varying spellings) is another example of Hollywood bringing attribution and moral rights in-house. Starting in 1969, the Directors Guild of America developed a policy for those cases in which directors were so horrified by the studio’s version of their films that they wanted their names removed from it. During the Golden Age of the studio system, when directors were on annual contracts to studios and were assigned films to work on, they had no expectation of having their individual vision come through. Critics developed the auteur theory to identify the moments when directors left an individual imprint on a film, despite the factory-like process of the studio system. After the transformation of the studio system in the 1960s, however, directors, critics, and the public all began to expect films to bear the individual vision of their directors. Directors, in turn, began to take steps to protect their reputations and the integrity of their work.

It was at this moment in the late 1960s that directors began to demand that their names be removed from films when they lost control of their vision. Starting with the film Death of a Gunfighter (1969) (fig. 3.3), the Directors Guild formed a board to arbitrate disputes over credit and anonymity. Directors could now appeal to the board, which had the power to decide that a director’s work had been so distorted that he or she had the option of having his or her name removed and replaced with the pseudonym Allen Smithee (or some variation). Directors could always have used pseudonyms. But as a shared pseudonym, the Allen Smithee designation also served as a marker of tensions between directors’ and studios’ intentions. The Allen Smithee pseudonym served as an extralegal compromise to the moral rights dilemma. Directors could withdraw their name from a distorted work, but the studio could still profit from the work. In some ways, the Allen Smithee solution is more effective than the legal version of moral rights. Moral rights might have allowed a director to withdraw a work from circulation. But the Smithee credit and the often well-publicized battles that surrounded its adoption publicly announced the integrity of the directors and often pointed audiences toward the inevitable release of the authentic version, the director’s cut.42

FIGURE 3.3 Death of a Gunfighter (1969), the first film to carry the Allen Smithee credit.

The directors who have taken advantage of the Allen Smithee option have invariably come from the generation reared in the auteurist New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 1970s: Robert Altman, William Friedkin, Dennis Hopper, and many others. And it will be no surprise that directors have frequently petitioned for an Allen Smithee credit when they have been unhappy with the versions of their films that studios reedited for television. Friedkin (The Guardian, 1990), Hopper (Backtrack, 1990), David Lynch (Dune, 1984), and Martin Brest (Scent of a Woman, 1992; Meet Joe Black, 1998) are among the directors who have used the Smithee credit for television versions of their films, even when they attached their real names to theatrical versions.

The New Hollywood auteurs have occasionally asserted their rights by asking to have their names removed from work changed by the studios. More often, however, they have sought to prevent others from building on their names, reputations, and original creations. In general, trademark, unfair competition, and defamation law are better suited than copyright to protecting reputations, especially in a country without moral rights. And Coppola, Lucas, and their cohort have aggressively used these elements of the law. But they also discovered copyright law early in their careers, and they have frequently used copyright law to safeguard the new authorial powers that the studios granted them. Where filmmakers and studios spent the first decades of Hollywood’s existence fighting to use age-old genre conventions without having to ask permission, the New Hollywood auteurs have, on occasion, fought for control of entire genres through copyright law.

In the mid-1970s, three of the most successful auteurs, William Friedkin, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas, made blockbuster genre films—The Exorcist (1973), Jaws (1975), and Star Wars (1977), respectively. If they did not invent the blockbuster, they brought it to a new level, and they each reinvigorated the genres that they worked in. They did not transform the genres, as critic John Cawelti has described the function of many films from the same period, like Chinatown (1974); Lucas, Spielberg, and Friedkin did not criticize or subvert genre conventions. They paid homage to established genres; they amplified the genres’ conventions; and they infused the genres with studio budgets, special effects, and stars. They turned B movies into blockbusters and converted formulaic genre fare into bold authorial statements. All three films also became the subject of copyright lawsuits.43

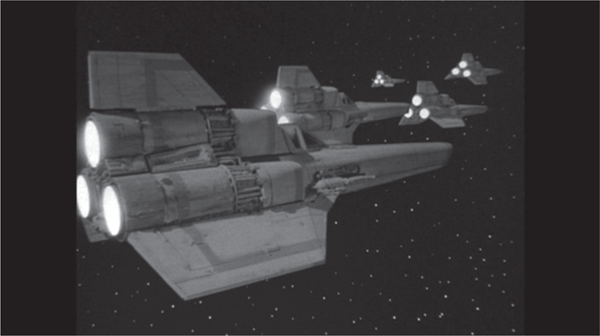

Star Wars, for example, is steeped in the genres of science fiction and fantasy, and it is filled with allusions to other films, including the re-creation of an iconic shot from John Ford’s western, The Searchers (1956). Lucas borrowed most directly, however, from the science fiction serials of the 1930s and 1940s like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, with their outrageous villains, wipe transitions between scenes, and cliff-hanger endings. Despite his generous use of film history, Lucas has always had a low tolerance for work that he thinks takes inspiration from his films. Throughout his career, Lucas has used copyright law to control—or at least attempt to control—the influence of his films. Shortly after the release of Star Wars, Lucas created a licensing bureau to review fan fiction for potential copyright infringement.44 This was an aggressive approach to fans who were simply sharing their own homemade creations with each other. It is especially aggressive considering that science fiction has a long history of stimulating creative work from fans. Lucas took an even stronger stance toward commercial work. Just a year after the release of Star Wars, the science fiction television series Battlestar Galactica (1978–79) appeared on U.S. television screens, presenting Lucas with his first opportunity to respond to a high-profile work that was clearly indebted to the science fiction craze he had started. (Just a few years later, all of the studios were feeding the demand for science fiction with films like Paramount’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Disney’s Black Hole [both 1979].)

Battlestar Galactica clearly owed a lot to Star Wars. Television critic Tom Shales dubbed Battlestar Galactica a “Star Wars superclone” (figs. 3.4 and 3.5). The similarities between the space battles of the film and television show are particularly striking and for good reason: John Dykstra headed the special-effects departments for both. According to Dykstra, Lucas had not sufficiently compensated him for his work on Star Wars, and when Lucas moved his special-effects company, Industrial Light and Magic (ILM), from Van Nuys to San Rafael, Dykstra took over the old building, setting up a special-effects house of his own. Dykstra urgently needed a client to pay the mortgage when the Battlestar Galactica job appeared. Having honed his skills at ILM, Dykstra used many of the same techniques and pieces of equipment—including his own Dykstraflex camera—that had been developed for Star Wars. Dykstra’s contributions to both Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica raised some novel questions for studio copyright lawyers. In Battlestar Galactica, did Dykstra use new techniques of storytelling that were discovered while making Star Wars but available to all once the ideas were uncovered? Or were these techniques so closely identified with Lucas’s authorial style that any use of them infringed on Lucas’s monopoly on expression? Or—another possibility—was Dykstra really a coauthor of both special-effects–laden works?45

Lucas was not flattered by the comparisons between his movie and the television series that resembled it, nor was he willing to attribute the similarities to the genius of his special-effects guru. Lucas published a letter in Variety accusing Battlestar Galactica of selling itself as “Star Wars for TV,” and he claimed that people were mistakenly attributing the workmanlike television series to him. “I got hundreds of letters,” Lucas told biographer Dale Pollock, “from people saying, ‘I think your TV show is terrible.’ It was very upsetting.” Battlestar Galactica’s producer, Glen A. Larson, defended himself in the press, protesting that he had been developing the idea for eleven years, before the success of Star Wars proved to the networks that science fiction could reach a mass audience.46

FIGURES 3.4 and 3.5 Did the Battlestar Gallactica TV series (1978–79) (top) take too much from Star Wars (1977) (bottom). Were both films using the same genre conventions? Or are the similarities the result of the two works having the same special-effects designer?

Lucas, however, saw deep similarities between the two works, and he insisted that Fox, the producer of Star Wars, sue MCA/Universal, the producer of Battlestar Galactica. The lawsuit made Lucas look like a sore winner, since Universal had foolishly passed on Star Wars even after Lucas gave them the successful American Graffiti (1973) just a few years earlier. Universal responded by countersuing Fox, making the even more outrageous claim that Star Wars infringed on Douglas Trumbull’s 1972 environmental-themed science fiction film Silent Running, which also featured cute, small robots who beeped. The whole row sounds like internal Hollywood politics, but Lucas’s investment in redefining authorship and ownership was serious, and he pursued the case for years.

In the district court, Universal asked Judge Irving Hill to decide whether or not the case had enough merit to be heard by a jury. A relatively new legal standard held that only the “total concept and feel” needed to be similar for Judge Hill to allow the case to proceed. This new standard, as Siva Vaidhyanathan explains, made film copyright law much “more unpredictable” in the 1970s, as California courts worked out the contours of the new jurisprudential concept. After viewing the film and television show, however, Judge Hill thought that all of the similarities that Lucas saw between his film and the television show were merely similar uses of well-worn science fiction conventions. As an example of the similarities, Fox noted that at one point in the Canadian theatrical release of Battlestar Galactica the word android is abbreviated as “droid,” as it is abbreviated throughout Star Wars. But Hill was not convinced. He “doubt[ed] very much that the plaintiffs own that word,” and he found most of the other examples of similarities to be so general that no one could own them either. Fox’s claims amounted to a purchase on the entire science fiction genre, and “no one,” Hill concluded, “owns the genre of space fantasy and of warfare in space.” Fox continued to push the case, and after three years of delays, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals—the court that initially introduced the “total concept and feel” standard—issued a decision reversing Hill’s ruling and finding sufficient merit to let the case proceed to a trial. Before a jury could hear the case, however, Fox and Universal settled out of court. According to one account, Lucas only agreed to the settlement after he received a personal apology from Universal’s president, Hollywood’s “last mogul,” Lew Wasserman. An apology from Wasserman was no small gesture, and Lucas had successfully proven the power of the auteur in the New Hollywood.47

Fox v. Universal was only the beginning of George Lucas’s lifelong crusade to control both commercial and fan creations that built on Star Wars. Fox’s case against Universal, however, stemmed from a systemic change in the studio system, and not simply from George Lucas’s personal feelings about authorship and intellectual property. At the same time that Lucas tried to change the dynamics of film authorship, similar lawsuits involving films directed by Lucas’s fellow New Hollywood auteurs William Friedkin and Steven Spielberg were also under way.

Like Star Wars, both The Exorcist and Jaws borrowed heavily from genre conventions, which they then polished and marketed with studio support. In Jaws, Spielberg took the low-budget, teen exploitation films that filled drive-in screens, and he added the taut pacing, natural acting, and crisp cinematography of a major studio release. Despite the studio veneer, however, Jaws was true to its roots, and the film announced itself as a classic teen/shark movie from its opening credit sequence. Under the credits we see teenagers drinking around a beach bonfire before the eponymous shark eats a skinny-dipping coed. The Exorcist similarly took the conventions of the low-budget horror film and dressed them up with expensive special effects, Academy Award–nominated performances, and haunting imagery.

In contrast, Film Ventures International (FVI) was exactly the kind of company that produced the low-budget horror films and shark-attack movies The Exorcist and Jaws drew on. Starting in the 1970s, FVI’s president, Edward Montoro, realized that the studios were moving into his territory, and he relocated his company to Los Angeles and developed a new business plan. Montoro began to wait for studios to renew interest in a time-tested genre before he would release a similar film. Montoro very clearly imitated the 1970s blockbusters, and he often announced as much in advertisements. But, in a sense, this is exactly what B-movie producers had always done. When one sea creature or alien invasion film found a large audience, independent producers responded by churning out lookalike films for midnight screenings and drive-ins. Even Hollywood studios made a practice of cycling though genre films after one struck a nerve with audiences. But were the genre pictures of the New Hollywood auteurs different? Did they contain so much personal vision and so many innovations that they demanded more protection than other genre films?

Montoro discovered the answer when he released exorcism and animal-attack films on the heels of Friedkin’s and Spielberg’s hits. In 1974, FVI distributed the exorcism film, Behind the Door, one year after The Exorcist. Two years later, and one year after Jaws, FVI made the Jaws-like bear attack film Grizzly, which by some accounts grossed over $30 million that year. Throughout the 1970s, FVI continued to release low-budget exploitation films, including Beyond the Door II (1977) and Day of the Animals (1977) with Leslie Nielson. Then, in 1981, FVI picked up the U.S. distribution for an Italian film called L’ultimo squalo, which was released in some countries as The Last Jaws, though FVI distributed it in the United States as Great White. One year earlier, Universal had released Jaws 2 (1978), and the studio was preparing Jaws 3-D (1983). Montoro’s run as a B-movie copycat was coming to an end.48

The studios behind both Friedkin’s and Spielberg’s films took FVI to court. They had paid for singular cinematic statements by rising auteurs, and they were not going to share their investment with others. Ironically, Universal Studios, the studio that made Battlestar Galactica, also made Jaws, and in the case against FVI, they were protecting the same broad claim to Spielberg’s authorship that they fought against in the case against Lucas. Of course, intellectual property always looks different when it belongs to you.

There may have been contradictions in Universal’s positions, but Montoro was not the most sympathetic defendant. In fact, he resembles a B-movie antihero himself. While fighting multiple copyright lawsuits against the studios, Montoro also ended up in court for failing to pay actors and directors, and he clearly made a living by capitalizing on the success of others’ films. He may also have ended his career abruptly after absconding with $1 million in company funds. But did Montoro really take Friedkin’s and Spielberg’s original ideas, or was he simply using the genre conventions that they used, too?49

The same court heard both the Exorcist and Jaws cases, although it came down on different sides in each. In The Exorcist case, Warner Bros. did not claim that the story of FVI’s Behind the Door was substantially similar to Friedkin’s. Instead, they used the “total concept and feel” standard in a novel way, arguing that FVI’s film copied The Exorcist’s style of special effects. They claimed that FVI had copied the character of the possessed child Regan as well. The court denied a preliminary injunction, which would have halted exhibition of Behind the Door. Like the Star Wars decision, this court found that both FVI and Friedkin had drawn from the same well of “haunted-house type” effects, and they had not used the effects in a substantially similar sequence. As for the character of Regan, the court explained that no one could own the idea of demonic possession, which the court imbued with some pseudoscientific validity by calling it a “phenomenon.” Moreover, the judges opined, the inner turmoil experienced by the children in both films was the logical response of a person struggling with demonic possession. In other words, these films were both using the same genre elements and similar, logical plot lines.50

In the Jaws case, however, the same court found that Great White resembled Spielberg’s shark film too much to simply be two instances of the same genre or even subgenre. I have not seen Great White, which the court enjoined from further distribution. But reading the court’s comparison, the similarities sound simply like the recipe for a shark movie. “The opening scene in both films,” the decision tells us, for example, “depicts teenagers playing on the beach.” Moreover, “the salty skippers, both … have English-type accents and are experienced shark hunters.” In other instances, the court seemed to stretch very far to find connections. “The local shark expert in Great White…,” the decision explained, “is a combination of two characters in Jaws.” All of the characters that the court describes sound like stock characters from a shark-attack movie: the politician concerned only with the image of the town, reckless teenagers, “salty” skippers. If Great White’s creators combined two characters from Jaws, that is a significant difference, not a similarity. Further, most of the action that the court describes also sounds like predictable genre storytelling: a shark attacking a dingy, a girl who falls into the water only to be saved from a lurking shark at the last minute, a finale in which the skipper is eaten but the shark is ultimately killed. The one persuasive comparison described in the court decision is that the shark in Great White is accompanied by bass tones on the soundtrack, clearly a reference to the signature of John Williams’ unforgettable theme. The two films may have been substantially similar, but the decision does not do a convincing job of outlining the similarities. The originality of a genre film comes from the subtleties, not from the use of stock characters and predictable plots. Nevertheless, the court thought that enough similarity existed for an “ordinary observer” to notice the shared “total concept and feel” of the two works—the standard introduced by the Ninth Circuit.51

It may very well be true that Great White took too many elements from Jaws, and the other FVI films borrowed less from the blockbusters they resembled. But clearly two larger structural elements had collided to reopen debates over the ownership of film ideas. The Ninth Circuit had introduced a vague standard for determining similarity, and Hollywood had redefined film authorship in such a way that rising auteurs felt entitled to new levels of protection for their contributions to genre categories. These were not moral rights cases, although they all used copyright to police the reputation and integrity of filmmakers. This spate of cases, however, revealed that the New Hollywood auteurs were prepared to defend their authorial claims. And it would not be long before Lucas, Spielberg, and others turned to the legal doctrine of moral rights to protect their vision of the auteur.

Contemporaneously with the rise of the New Hollywood auteurs, another group of fiercely independent artists were making their way into British living rooms, challenging social mores and pushing accepted standards of representation. Monty Python’s Flying Circus first aired in Britain on October 5, 1969, but it would take another five years before the show premiered in the United States. When The Flying Circus appeared on New York City’s PBS station, Channel 13, it quickly became the most popular and profitable series in the station’s history, and other PBS stations across the country picked up the show as well. On public television, however, the Pythons only reached a limited market. Then, in 1975, ABC offered to syndicate the show for a national audience. At the time, the Pythons were about to launch a feature film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), and they were reaching for a wider American public. Nevertheless, they turned down the ABC offer, wary of the artistic compromises that would come with commercial television. The Pythons initially made The Flying Circus for the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), and they had not designed the format to be interrupted by commercials or truncated to fit new timeslots. Undeterred, ABC officials did some further investigation, and they learned that Time-Life Films held the U.S. syndication rights to the Python shows. ABC proceeded to license several of the later Python episodes for a late-night program called The Wide World of Entertainment. Thus began the next pivotal chapter in filmmakers’ (and television makers’) campaign for moral rights as protection against television editing. For the first time, however, the artists would triumph against the commercial film studios and television networks (fig. 3.6).52

Still suspicious of commercial television, the Pythons thought they had been assured by ABC executives that the shows would air unchanged and in their entirety, although they understood that there would be commercial interruptions. When the Pythons saw a tape of the ABC show, however, the comedy team realized that it had been misled. ABC cut approximately twenty-four minutes of each 90-minute program. ABC not only abbreviated the shows, however; they cut out more than forty clips that the network deemed offensive or indecent. Sketches lacked endings. Seemingly tame gags, like a cat being used as a doorbell or a woman wiping her feet on a loaf of bread, were excised. According to Python illustrator Terry Gilliam, who served as the lead plaintiff in the case, “all mentions of the body were cut out,” including bleeping out the Pythons’ signature euphemism, “naughty bits.” Earlier judges had warned that television editing might result in the emasculation of films. Did the Pythons losing their naughty bits to ABC’s scissors qualify?53

FIGURE 3.6 Monty Python successfully blocked their work from being edited for U.S. television.

With less than two weeks to the next scheduled airdate, the Pythons asked for an injunction to stop ABC from showing the recut version of The Flying Circus. Like Preminger’s and Stevens’s claims, the Pythons sought to protect their artistic integrity. But this was also a clash of cultures. The iconoclastic Pythons built their reputation on challenging social conventions and the stodgy limitations of television representation. “The Python’s form of experimentation,” Marcia Landy observes,

was at odds with the needs of commercial television to satisfy sponsors, the direct and indirect forms of censorship, and concerns about ratings. In short, the philosophy of the BBC world inhabited by the Pythons and that of the major networks of American television tended to utilize the medium differently.54

Editing The Flying Circus to conform to the very standards that it attempted to subvert robbed the show of its humor and its appeal. In the Python case, courts were asked to decide whether standards of network television nullified the essence of the Pythons’ irreverent humor. Terry Gilliam and the other Pythons did not complain about the number of cuts or the amount of time deleted from the shows, as Preminger and Stevens had. They complained that the continuity, the humor, and the integrity of their shows had been lost. The case would hinge on the qualitative transformation of the shows’ content, rather than an arbitrary quantification of art (minutes cut or percentages deleted).

From a contractual perspective, this case looked a bit different than the Autry, Rogers, Preminger, and Stevens cases. The Pythons had the British television equivalent of a final-cut contract, but in the world of British broadcasting the authorial rights seemed to stretch beyond the first airing of a show. The Pythons also retained the rights to their scripts, and they claimed that the ABC version was an unauthorized adaptation—a derivative work—based on their scripts. The question of who controlled the rights remained in question throughout the many permutations of this case, but judges who heard arguments in it all agreed that the Pythons retained some right to complain about the distortion of their work.55

The Pythons may have had a stronger claim to control their work than the American directors who had gone down the same path before them, but their complaint was couched in the same bodily (Lockean) language. Terry Gilliam called the ABC versions “amazingly bowdlerized and butchered,” and the official complaint used the term that had emerged as the technical legal designation for moral rights violations through television editing: “mutilation.” The Pythons hired young copyright litigator Robert Osterberg to represent them, and they asked for the headline-garnering sum of $1 million in damages. The edited versions of the Python shows, Osterberg argued, had hurt the Pythons’ reputation and falsely represented their work; ABC, moreover, had failed to get the Pythons’ consent before creating a derivative work.56

With only seven days before The Flying Circus’s ABC airdate, Terry Gilliam and Michael Palin flew to New York to testify before Judge Morris Lasker. In a daylong hearing, Judge Lasker heard from ABC executives, the editor who worked in ABC’s Standards and Practices office, and, of course, Gilliam and Palin. The ABC employees explained that they were simply doing the business of a television network, and that canceling a show at this late date would be a significant financial burden. At one point during the day, ABC’s lawyers accused the Pythons of having “unclean hands,” of simply using the case for publicity, but the speciousness of that accusation was soon revealed.57

On behalf of the Pythons, Terry Gilliam spoke eloquently about the dangers of censoring art, and he brought the case back to the larger issues of the clash of corporate and artistic cultures and the right of integrity—the moral rights—at stake in the case. Gilliam worried that the ABC version would give the impression that “Monty Python has finally accepted the standards of commercial television, as opposed to our own standards.” And he explained that “there is an element of integrity in what we have done. Good, bad, or indifferent, it doesn’t really enter into it. It seems to me it is an element of integrity. I think the show that is going out compromises that integrity.”58