Chapter 5

Showing Up for Yourself When Shit Gets Hard

Showing up for yourself when times are good can be hard enough; showing up for yourself when you’re going through a rough patch can feel downright impossible. But, of course, that’s when you need to show up for yourself the most.

In late August 2015, my husband disappeared. Like, didn’t-hear-from-him-for-days, hadn’t-shown-up-for-work, I-called-the-police disappeared. After three days, he returned to our Brooklyn apartment. But the next weekend, after he’d spent a few days in the hospital and a couple more on our couch, he left home again—this time for good, though I wouldn’t know it was permanent until months later.

Not a single day that followed made any sense. The fact that this could happen—that our seemingly normal life together could fracture so catastrophically, so suddenly, and in such a jagged, unfamiliar way—was shocking, and it was that shock, along with the grief, that completely gutted me. As September turned to October, I lost my appetite and then 10 pounds; all the padding disappeared from my face and left me looking older. Then I began to feel so tender, it was like I no longer had any skin at all.

I knew on some level that I wasn’t OK—that nothing was OK—but I also didn’t know what to do with that. So I went to work each day like nothing was wrong (while also doing everything I could to save my marriage). My friends kept reminding me to practice self-care, a well-meaning comment that I found unintelligible. Like, a sheet mask or manicure wasn’t going to do a goddamn thing. The truth was, I was scared—of my dark, uncertain future but also of losing myself in my grief. I was afraid if I let myself lie down, even for a second, I wouldn’t be able to get back up.

But after three long months of white-knuckling my former life, it finally dawned on me on Thanksgiving: Oh . . . this is where I live now. That night, I surrendered. I bought myself two pairs of cozy pajamas—an outfit designed for the sole purpose of lying down. This was when I fully understood what it meant to show up for myself. It wasn’t about taking a bubble bath; it was admitting to myself, Things are bad, and they are going to be bad for a while. It was dressing not for the life I wanted, but for the life I had.

My new pajamas couldn’t save me, or my marriage, which would officially end two years later. But they helped. Because when you feel raw from head to toe, covering your body in something clean and soft and fresh and white feels very, very good. In this moment of trauma, I learned to dress myself by looking to how we dress all wounds. (One first aid website advises: A little bleeding is OK; it helps flush dirt and other contaminants out of the wound.) Wearing my winter-white pajamas and wrapped in my crisp and cozy all-white bedding, I was both the nurse and the patient. A little bleeding is OK.

It would be awhile before I felt true happiness again, but even on my worst days, putting on clean clothes always made me feel a little bit less bad, a little bit more human. And after months of feeling powerless, suiting up to face my unhappy reality gave me a tiny sense of control.

In that moment, I realized that things are good until they are not, and they are bad until they are not. So often, the bad times happen without any sort of warning. But I found it comforting to remember that the good periods also tend to happen without warning. This isn’t to say you can’t actively work toward improving bad situations; you can. But turning a corner, moving on, getting to the other side, whatever you want to call it, is a complicated thing that is often governed by, I don’t know . . . the wind? So instead of trying to change The Big Thing—which was fundamentally unchangeable—I just tried to make myself comfortable. I didn’t try to feel happy; I tried to feel less bad. I accepted beauty and joy wherever I could get it and trusted that these small things would help me hang on until the wind started blowing my way again. And you know what? They did.

This chapter is about doing what you can to feel a tiny bit better as you embark on your journey to the other side of whatever shit situation may befall you.

Let’s get started.

Dealing with Bad Times

“Normal” doesn’t really exist anymore.

When you’re going through a rough patch it can be incredibly disorienting to watch your “normal” life—your routine, your concentration, your favorite things, your stable moods—move somewhere beyond your reach, or disappear entirely. But this is, in large part, what loss is. Everything feels different because everything is different. You’re in a Bad Time; of course nothing will be normal.

I know how frustrating that can be. So not only is this shitty thing happening in my life, you might think. But now it’s affecting every area of my life??? Including the things I enjoy and care about and want to be doing? That’s . . . so fucking rude!!! And it IS fucking rude!!! Truly, one of the worst aspects of dealing with something traumatic or terrible is how big it is. Your stress and anger and grief aren’t restricted to when you’re engaging with the bad thing; you carry it with you everywhere. It might be harder to be good to your friends and your partner, to engage in your favorite hobbies, to excel at work . . . whatever. We all know this on some level, but when it’s your turn to go through something bad, it can still catch you by surprise. It’s important to allow yourself some time and space to grieve the loss of your old “normal,” and to allow yourself to make peace with the fact that things have changed.

Don’t look down.

When you’re in crisis, there will likely be a lot of big, scary, stressful tasks on your path forward. There will also be a lot of hypothetical questions that make you want to throw up (e.g., “How will I ever introduce future dates to my children?” after a divorce). Thinking about the amount of work—logistical and emotional—that you’re going to have to do can be panic inducing. And if you let yourself think about the future too much, or try to game out of every possible outcome, you can quickly find yourself overwhelmed and frozen, unable to do anything, including basic survival tasks.

There will be a handful of top-level tasks that you truly need to handle ASAP without thinking too much about them. But once you’ve taken care of, say, hiring a lawyer or figuring out your options for taking time off work, there’s a limit to what you’ll be able to do next. In that moment, it’s very easy to spin out over of dozens of imagined “someday” scenarios that may or may not ever happen. It feels a bit like being on a tightrope that is stretched across a river of alligators, a big fiery pit, and God knows what else. The other side is so far away, you sort of don’t believe it exists.

Should you find yourself in this spot, try to remember this mantra: Don’t look down. Instead, take one step. Then take another. Don’t imagine in vivid detail exactly how bad it would feel to fall into the shark pit or the quicksand or whatever horror you’re convinced is waiting for you in the final stretch. Don’t think about how many steps you still have to go. Focus on this step—and know that “doing nothing” might be the step.

When your thoughts wander to The Big Horrors, reply with a firm, “Don’t look down,” and focus on whatever is happening right now. Instead of thinking about the next year, maybe let yourself think only about the next month. With practice, you’ll be able to limit your thinking to just the next week. Finally, you’ll be able to focus on just the next twenty-four hours.

Not thinking about the future after my ex left was hard for me, but it wasn’t as difficult as I expected. I realized I had no choice. The alternative—feeling like my heart was going to beat through my chest every day because I was so stressed about what might happen in six months—wasn’t practical.

It was also a huge relief. It’s not like thinking about all the potentially terrible outcomes ever really felt good or effectively prepared me for what might come. Focusing on the present moment gave me the brain space I needed to tackle the tasks, big and small, that were necessary to move forward. Once I stopped looking down every ten seconds and quit thinking about the other side so much, I was able to get across some of the toughest stretches.

I had always thought of the phrase “one day at a time” as a fairly empty cliché, but finally, after several weeks of operating this way, something clicked: Oh, I have to take this one day at a time. There is no other option. It became the best survival mechanism in my tool kit. So if you’re overwhelmed by all of the possible worst-case scenarios, try thinking smaller. Take a tiny next step. When the time comes, take another. And don’t look down.

Embrace rituals.

Even if you’re really struggling, try to identify potential little rituals in your daily life that allow you to briefly connect to something beautiful, pleasurable, or sacred. Rituals serve to acknowledge the magnitude of your situation and to connect what is happening to you in this moment to the rest of humanity, past and present.

And involving your people in bigger rituals can help you feel grounded and supported. In The Joy of Missing Out, Svend Brinkmann writes that communal rituals (like singing “Happy Birthday” or sitting shiva) “are used to focus collective attention on important matters in certain situations. Every individual can seek to cultivate their own small landscape of everyday rituals to endow their lives with form, but this also has to be done at the collective level, where people do things together.”20 So, yeah—go ahead and host a funeral for your pet, have a reverse barn raising after your divorce (where your friends help you pack up your ex’s stuff to sell or donate), or throw a big-ass “I’m coming out” party.

Add structure to your indoor/hideaway behavior.

When you’re struggling, you’ll probably want to spend a lot of time hunkered down in bed or on the couch. And that’s fine! But being a little more thoughtful about that time can go a long way. For example, instead of letting Netflix tell you what to watch for a month straight, you could go through all of the best rom-coms from the past twenty years, or watch every episode of an old sitcom like I Love Lucy. Instead of scrolling through Instagram for hours, you could work your way through the entire Harry Potter series on audiobook. No need to get super ambitious here; the point is to look for small ways to upgrade the behavior that typically leaves you feeling sluggish and blah and turn it into something slightly more energizing.

“Healthy” Coping Mechanisms

If you’re reading this book, there’s a good chance you care about choosing “healthy” coping mechanisms—and it’s easy to believe that going to the gym is the “good” or “right” way to deal, while going out for drinks with friends is “wrong.” But I think it really depends on the person and the situation; when I’m struggling, I try to remind myself that seemingly healthy behaviors can still be used to self-medicate or to avoid dealing with my problems.

When you’re going through a hard time, maybe going for a run would actually be the best thing in that moment. But it could be that the “unhealthy” habit of getting drinks with friends would be the better choice. Or maybe neither would! Sometimes, feelings like anger and grief and stress are not a problem that can be solved!

If you can’t tell if you’re taking a legitimate break from your pain, or avoiding dealing with your life, therapist Ryan Howes suggests having a plan or even a schedule for engaging with whatever is stressing you out. That might mean addressing it daily, or a few times a week, or during weekly therapy sessions. “Having a plan makes a big impact,” Howes says. “Any sort of a plan, really. That’s the way we regain control. And coping is really about taking back some control.”

It’s also helpful to remember that some discomfort is to be expected. As Kelsey Crowe and Emily McDowell write in There Is No Good Card for This, most of us were taught very early in life that loss is intolerable. Grief and loss are painful, and of course we don’t want to tolerate that pain—we want it to go away. But sometimes, you just . . . can’t. Sometimes you’re just going to feel bad.

When You Can’t Do Anything, Clean Your Bathroom

Whenever I’m pacing around my home and/or kind of spiraling, and know I should do something but can’t decide what it should be, I’ll clean my bathroom. I don’t overthink it; I just go. And fifteen to twenty minutes later (which is about how long it takes me to clean my bathroom, despite what I like to tell myself when I’m avoiding doing it), my sink is sparkling and I feel better.

Why cleaning the bathroom? Because it tends to be a short and contained chore—unlike, say, cleaning your closet, which you’ll start with the best of intentions and then somehow spend seventy-five dollars ordering hangers online before falling asleep on piles of clothes—BUT it’s just long enough to help you get clarity on what to do next and to leave you feeling accomplished. It’s basically pressing the reset button in a panic moment. It’s also one area of your home that could always benefit from a little cleaning!

Tackling Basic Tasks

When you’re struggling, everyday tasks (like feeding yourself, sleeping, chores, etc.) can be the hardest to accomplish—which can be very disorienting. Like, “Wait, I can plan a whole funeral while eight months pregnant but can’t wash my hair or make myself dinner???” But yes—it’s a thing! During a rough period, taking care of yourself in the most basic ways might be much, much harder than you’d expect.

It can be a huge shock when you suddenly find yourself unable to complete activities that you previously did without a second thought. In my own life, the fact that I could barely feed myself upset me more than the realization that I wasn’t going to be on top of my game at work for a little while. Suddenly being unable to do the things that you’ve always considered basic care can make you feel helpless; it’s a very vulnerable place to be, and it can be hard to admit you’re there. But if you are there, try not to beat yourself up for not being able to do “simple” tasks—because nothing is simple when your life is falling apart, and it’s pretty well established that humans struggle to complete basic tasks when they are having a hard time. And “humans” includes you.

Even if you’re unable to engage in these behaviors at the level you normally would, it’s still important to find a way to do some version of them—particularly if you’re tempted to deprioritize them and instead look for other, sexier ways to feel better. I know that when you’re in crisis mode, you may truly not have the option to do less at work, at school, or as a parent so that you can focus on taking care of yourself. But consider this your gentle reminder that if you’re not sleeping or eating or drinking enough water, you’re probably not going to be able to manage the rest of what’s on your plate. These are the survival tasks; they aren’t something you can blow off for extended periods of time without consequences.

If you’re struggling to take care of yourself and meet your most basic needs, read on for some tips that might be helpful.

Nourishing Yourself

Welcome shelf-stable and frozen foods into your life.

When you’re going through a rough time, your schedule, appetite, and energy levels can be unpredictable, which can mean you end up wasting fresh groceries. That’s why frozen foodstuffs—like vegetables, fish, potatoes, and pierogis—can be a godsend. They don’t require much in the way of prep or cleanup and won’t go bad in three days. Along with frozen foods, consider embracing beans, pasta, peanut butter, packaged ramen, and canned tuna. They last a while and have the added bonus of being relatively cheap.

Don’t sleep on toast and tea.

Toast and tea are classics for a reason, and there are more options for toast than your standard butter with cinnamon sugar (though I eat that for dinner . . . not infrequently). Lately I’ve been into toast with tahini, sliced banana, a drizzle of honey, and dried lavender buds (which you can buy on Amazon). It feels fancy but isn’t fussy, which is my favorite kind of meal.

Remember, it’s OK to eat the exact same meals over and over again.

Once you figure out something that works for you (like toast and tea!), it’s completely fine to just stick with it for a while! My go-to meals when I’m struggling (and even when I’m not, TBH) are Sue Kreitzman’s lemon butter pasta and Smitten Kitchen’s chickpea pasta (see the Further Reading section for links to both recipes); both are fast, easy, inexpensive, and nourishing, and are made from ingredients that will last in your pantry for a while.

Bathing

Remember: You don’t have to take a shower shower to clean yourself.

If you don’t have it in you to take a full shower, you could clean the grossest parts of your body with a soapy washcloth or cleansing towelette to remove odor-causing bacteria. (Grossest parts of your body = “face, underarms, under the breasts, genitals, and rear end,” according to dermatologist Joshua Zeichner.) If the idea of washing/drying your hair is what is overwhelming, get a drugstore shower cap and take more body showers.

Put on clean clothes (or clean underwear), if you can.

Humans shed a lot of odor-causing bacteria in our clothes, which is good news if you want to shower less. If you’re worried you’re starting to smell a little funky, make sure you’re changing your clothes and undergarments regularly. One of my firm rules no matter how bad things get is to always swap the clothes I slept in and for fresh day clothes in the morning—even if I’m just getting back in bed. These day clothes don’t have to be nice or formal or anything, either. Just clean-ish!

Take a bath instead of a shower.

A lot of people find baths relaxing, but they also serve a practical purpose: cleaning your meatsack! And if you don’t have the time or energy or bathtub for a full-on Calgon-take-me-away soak, consider the budget version of it, aka just sitting down on the floor of your tub while your shower runs.

Soak/wash your feet!

God, what a treat.

Sleep

Take note of how much sleep you’re getting.

As I mentioned in Chapter 3, it can be very easy to tell yourself you’re fine . . . while your actual habits tell a different story. And sleep is foundational to our physical and mental health. So make a point of recording how many hours of sleep you’re getting each night, the frequency and duration of naps, and/or notes on how well you’re sleeping.

Know that sleeping all the time (or being exhausted all the time) can be a sign of depression.

It can be difficult to realize you’re sleeping all the time because of mental health issues because it can feel so physical—like, you’re actually tired, so sleeping feels like the correct response. That’s why it’s a good idea to track your sleeping habits, and to talk to your health care provider if you are always exhausted or spending a lot of time sleeping.

Be even more conscious of how much time you’re spending online or streaming shows or movies before you go to bed.

When you’re dealing with a lot, zoning out is very, very appealing. And I hate that when you already have so much going on, you have to worry about whether or not you’re on Instagram too damn much. But being on your phone before bed isn’t doing you any favors, and might in fact be keeping you from a good night’s sleep (or just an extra couple of hours). If at all possible, give yourself a hard cutoff time for phone usage and try to find an analogue way to zone out before bed (e.g., coloring, doing extremely easy crossword puzzles, or reading the paperback equivalent of a reality TV show).

If you have to choose between sleep and other things that might make you feel good (like exercise or cooking at home), choose sleep.

Sleep is so core to our health and to everything we do—don’t skimp on it in the name of other “healthy” activities.

Cleaning Your Space

When life gets rough, it doesn’t take long for our homes to start to reflect that chaos. But it doesn’t take a giant crisis to make taking care of your space difficult! Anyone’s home can be a big ol’ mess, especially if you’re dealing with anxiety, depression, ADHD, chronic illness, or chronic pain. So if/when you need a little help handling your havoc, here are some of my favorite tips from Rachel Hoffman in her excellent book Unf*ck Your Habitat.

Prioritize cleaning things that smell bad or have the potential to smell bad.

So: laundry, the fridge, trash, dishes, litter boxes. If that’s all you can do for now, that’ll still make a pretty meaningful difference in how clean your place is (and how clean it feels).

Or start by tackling the flat surfaces (in five-minute bursts).

As Hoffman puts it, “tidy up your tops”—it’ll give you a lot of bang for your buck. So: Locate the nearest flat surface (like your nightstand or your kitchen table). Got it? Cool. Now set a timer for five minutes and take as much as you can off that surface (and put those things where they belong) in that time. That’s it!

If possible, put a garbage can in every room.

Having a trash can near your bed and one by your couch means your side tables won’t be sacrificed to greasy takeout containers, snotty tissues, empty Gatorade bottles, and crusty contact lenses when you simply don’t have it in you to go to the kitchen or bathroom to toss them.

Recognize when you need help.

When I was eighteen and living on my own for the first time, my dirty dishes became A Problem. I hated doing them (STILL DO! UGGHHHH WATER CHORES!!!) and I let them pile up in the sink for so long that I was pretty sure the dishes at the bottom were growing mold, but I couldn’t bear to find out. One day, my friend Amelia came by my apartment, saw the mess, and just . . . offered to do the dishes for me. Like, wholeheartedly offered—because she doesn’t mind doing dishes and could probably also see that these dishes needed to be done and I was clearly too stuck in a shame spiral to do it. So even though I felt guilty and embarrassed, I let her do my dishes. It took her like twenty minutes. (She showed me the mold she uncovered and it wasn’t actually that bad or scary!) It was so kind and such a huge gift, but also not that big a deal, you know? My point: When people offer to help you, believe that they mean it. And if no one has explicitly offered, know that it’s still OK to ask for and accept help.

Try to have one positive interaction with your home each day.

“Try to do something—anything really—that allows you to interact positively with your home every day,” Hoffman says. “Whether that’s cleaning, organization, or even just displaying something that makes you happy, aim for getting one thing done every day that makes you feel better about where you live.”

Let Yourself Throw Money at the Problem

Money can’t solve all your problems or bring back the life you’ve lost, but it can still help a lot—particularly when everyday tasks are turning into giant stressors or huge stumbling blocks. Money can pay for everything from grocery delivery to taxis to a professional house cleaning to the cost of a canceled flight. To paraphrase my friend Meg Keene, there will be times when you think, “I do not care about this thing and I will rip out my eyes if I have to think about it for one more second. Hence, I will throw money at it.”21 When you’re struggling, money pays for convenience, and the ability to be a tiny bit less stressed out.

Of course, this won’t always be an option—it obviously requires that you have money, which not everyone does! But if you do have a little money and just aren’t giving yourself permission to spend it, remember the classic Don Draper quote that I will now use completely out of context: “That’s what the money is for!!!”

How to Tell People You’re Going Through a Tough Time

As a fairly private and generally upbeat person, I spent most of my life staying silent whenever I was going through a difficult time. I actively avoided telling people—particularly my coworkers and casual friends, but even close friends, too—that I wasn’t doing well. But there are two big reasons I’ve started doing it more regularly. First, being honest is a relief. Going through a difficult time can feel a lot like carrying a stack of delicate china while walking on a tightrope. What you don’t need at that moment is to have to hide how much you are struggling to keep everything from falling out of your arms—or worse, to pretend it’s a breeze. You may not be able to set down the china or step off the tightrope right now, but you can at least admit that what you’re doing is hard.

Second, being honest gives other people an opportunity to show up for you. When you’re in the midst of a crisis or low period, it can be hard to remember how much people care about you or to believe that their support will actually make you feel better. And hey, maybe it won’t help! But don’t underestimate the power of a supportive friend or community; even just a heartfelt “I’m so sorry to hear that” or “That sounds really tough, and I’m here for you” can make you feel a lot less alone and less afraid. Sure, there might not be anything they can do to change or fix the situation, but your candor opens the door for other forms of support, including hugs, cute kitten videos, a few freezer meals, or just extra kindness and grace. You don’t have to share your private business with everyone you encounter to feel this relief and support; in my experience, it comes from simply telling one or two people a little bit about what’s going on (especially if they are people you see or talk to fairly regularly).

If you struggle with receiving care, consider that when you let people show up for you it’s good not only for you but for them, too, and could in turn be great for your friendship. As Shasta Nelson says, “There are downsides to pretending we don’t have needs: It denies that we’re human, and it robs our friends of the joy of giving. We’re not as fun to play with if we only sit at the bottom of the teeter-totter, never giving our friend a chance to push us up.”22

A lot of us take it as indisputable fact that no one who asks “How are you?” wants a real answer. But . . . is that really always the case? Why have we all decided that this is true? I ask people how they are doing every day, and even if I’m sometimes saying it out of habit, I still want to know. And I’m not unusual in this regard; while there are certainly exceptions to this, it’s likely that the people in your everyday life do actually care on some level. But even if the asker isn’t consciously looking for the most honest answer, they likely won’t recoil in horror when you offer it.

If you’re worried about burdening someone who just wanted to exchange pleasantries, that can be mitigated by what you share and how you share it (more on this in a moment). But in the age of perfectly curated and relentlessly positive social media posts, a lot of people welcome a conversation with someone who is willing to be vulnerable. If we were all a little more honest in the moments that we’re not doing well, maybe we’d all feel a little better.

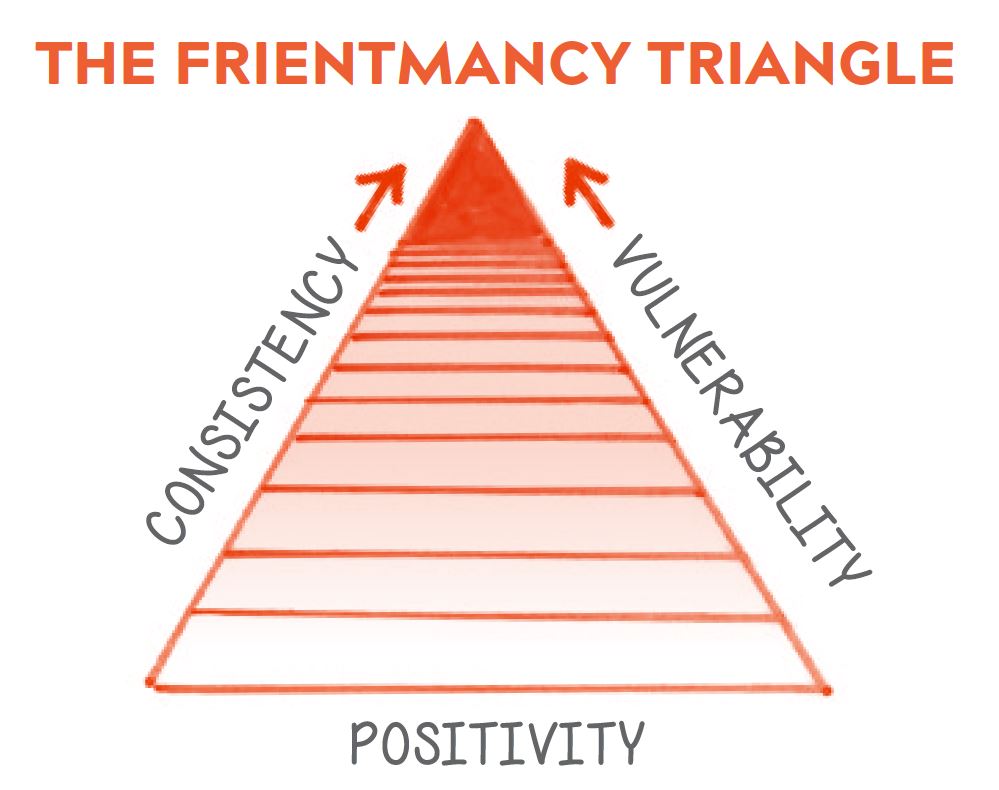

When you’re thinking about whether and how to be more honest, consider two things: what you’re comfortable with sharing and your relationship with the other person. Ideally, what you say should match the level of intimacy you currently have. Nelson frames this kind of opening up in the context of what she calls the “frientimacy triangle.” The three sides of the triangle are positivity (which in this context means genuine interest, joy, amusement, humor, and pleasantness); consistency (i.e., spending time together, which establishes confidence and trust in the relationship); and vulnerability (sharing more personal details, being willing to be exposed and honest).

Positivity, because it’s a baseline requirement, forms the base of the triangle. But in this usage, positivity is not about being intractably upbeat. “Positivity does not refer to what we’re talking about,” Nelson told me. It refers to the joy, interest, humor, gratitude, and warmth that are present in each conversation and in the relationship as a whole. “Even when we’re hurting, we can be grateful, we can be curious, we can affirm other people. It’s still our job to make sure people leave the conversation feeling valued.”

Once a baseline of positivity is established, Nelson says, consistency and vulnerability (the two arms of the triangle) should move upward at roughly the same pace. So if the consistency (the amount of time you’ve spent together, the length of the relationship, and so on) is relatively low (think of a 2 on a scale of 1 to 10), whatever you share will probably be relatively low in vulnerability as well. You can still be honest with people you have met fairly recently, but recognize that a new friend likely isn’t the best audience for every messy detail of your life. “It’s always appropriate to share what’s going on in your life, but we shouldn’t be processing with the people at the bottom of the triangle,” Nelson says.

Let’s say you’re going through a divorce. With the friends who are at level 1 or 2 on both consistency and vulnerability, Nelson suggests you might say, “I’m going through a divorce and not gonna lie, it’s pretty rough. But I am looking forward to making new friends and keeping busy and trying to remind myself that there is plenty of love and fun to be had in the world.” With a level 9 or 10 person—like, say, a sibling you’re really tight with or your lifelong best friend—you might share the ways it’s affecting your children, your fears about dating again, and the fact that you cry yourself to sleep every night. As for everyone in the middle? Aim to share in a way that gives the other person the information and context you feel is most important (whether that’s “I feel sad” or “I need to take a few days off”)while still making clear that you don’t expect this person to react like a very close friend (or a therapist) would. “Share a little and see how the person responds,” Nelson says. “Pay attention to social cues. Are they asking questions? Is it only one-way sharing?”

Nelson says you can practice positivity even when you’re down by thanking the other person for listening, giving them permission to be happy about whatever is going on in their own life, being willing to laugh when you can, and remembering to say, “But enough about me; what’s new with you?”23

If you’re worried that being honest about your feelings will make you seem like a Debbie Downer, I get it—I’ve been there too. These tips have helped me think about my relationships as a whole instead of focusing on every individual interaction. When I zoom out to get that perspective, I can see that it’s perfectly OK for me to be a little more vulnerable and authentic with my friends—in part because we’re all doing our best to bring that genuine positivity, even when things are shit.

Don’t Mistake a Level 4 Friend for a Level 9 Friend

During our conversation, Shasta Nelson said something I’ve been thinking about ever since. We were talking about the levels of friendship, and I commented that most of us probably don’t have that many friends at a level 9 or 10—like, not that many people would reach that level of intimacy in our lives, right? She replied, “Many of us don’t have anyone up there.” She went on to say that if you don’t have a lot of friends in the top tier, it’s easy to treat level 4 or 5 friends like they are level 9 or 10 friends—because they are your “best” friends, even if they aren’t actually your best friends. It’s truly a bummer not to have someone who feels like Your Person, but trying to fast-track friendship in this way tends to backfire. So before you unload on your friends, it can be worthwhile to take an honest look at the relationship. Does the sharing go both ways? Are you Their Person, too? Or are you vaunting them to a higher level of friendship when it’s not really appropriate or earned?

If you’re thinking that being more open would make you feel better but simply have no idea how to respond to “How are you?,” here are some ideas that you can use as a jumping-off point.

What to say

What to say

“Eh, I’ve been better, honestly! I’d rather not get into it, but I’d appreciate any good vibes you want to send my way right now.”

“Honestly, it’s been a rough few [days/weeks]. I’m dealing with some [stressful stuff in my personal life/family drama/family stuff/health problems/stuff] and could use some good vibes right now.”

And try not to overthink the phrase you use to describe the situation here! “Some stressful stuff in my personal life” can cover pretty much everything, and you don’t owe anyone a full explanation on exactly what’s going on with your latest round of IVF and how it’s affecting your body and your marriage. The point is to convey, “I’m not OK and I don’t really want to get into why.” There are no vulnerability police who are going to throw you in jail for not choosing the exact “correct” phrasing for your specific issue.

If you want to be a little more forthcoming, try one of these:

“Honestly, it’s been a rough few weeks; my mom is having some health problems. But I’m hanging in there!”

“Hey, I just wanted to let you know that my mom was recently diagnosed with cancer. No need to worry—she has great doctors and I have a good support system in place. I don’t really want to talk about it now, but I wanted you to know in case I seem a little distracted or start taking more time off than usual.”

“Hey, I just wanted to let you know that my mom was recently diagnosed with cancer, and her prognosis isn’t good. She’ll be moving into hospice care later this week. I’m doing my best to keep it together, but I’m devastated. I don’t really want to talk about it right now, but I wanted you to know in case I seem [distracted/tired/weepy/out of it/down] or start taking more time off than usual.”

(Of course, you can skip the “I don’t really want to talk about it” if you’re actually comfortable talking about it!)

It’s also a good idea to set some boundaries in terms of sharing this information with others. Doing this is helpful for everyone involved—because if your friends know exactly what your expectations are, they are less likely to gossip and less likely to accidentally tell someone what’s going on. So you may want to add something like, “So far, the only people I’ve told are Kai and Alex. I’d appreciate if you kept this between us for now so I can tell everyone else in my own time.”

And if it’s not something you want to keep super private, you could say something like, “So far, I haven’t told a lot of people but I’m not trying to hide it either.”

Sharing Bad News Far and Wide

One of the worst aspects of experiencing something terrible is having to manage other people’s reactions to your bad news. But even if you know everyone around you will be supportive, having to talk about a painful experience is, well, painful, and sharing the news publicly (or semi-publicly) is often what makes it feel real for the first time.

To share bad news with a group, you can modify one of the scripts from above so it sounds more like this:

“Hi, everyone, I have some bad news to share today: My mom was recently diagnosed with cancer, and her prognosis isn’t good. She’ll be moving into hospice care later this week. I’m doing my best to keep it together, but I’m devastated. I don’t really want to talk about it right now, but I wanted you all to know what is going on.”

You may also want to add something like, “I don’t need anything right now, but I’m also accepting hugs and heart emojis,” which communicates, I don’t want to talk about it, but it’s also OK to let me know you read this and that you care. Most people genuinely just want to know what to do and say and are worried about doing the “wrong” thing; it’s totally OK (and, honestly, a kindness) to tell them exactly what you need!

As for the medium, you have a few options. While some people might argue that bad news has to be shared via phone or IRL, I disagree—I think texts, emails, and even status updates are appropriate in a lot of circumstances.

Email might feel formal, but I prefer it to texting for a few reasons. First, people tend to check their email when they are in the mood to read/receive emails. By sending an email, you increase the chances that they will read it at a time that is good for them, which means they can respond more thoughtfully. Speaking of responses, sending emails means people are more likely to reply via email—which means you can better control when you read and engage with these messages.

That said, texts are perfectly fine. A status update (on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.) can also work if you’ve already told the people in your inner circle and are now trying to reach a more extended network. And if you choose to share the news digitally, you may want to do it either first thing in the morning or in the evening (outside of common working hours) so that people are able to process the information and properly respond.

If you don’t have it in you to communicate the information on your own, don’t overlook the power of good gossip when it comes to sharing bad news. Good gossip here means gossip that you’ve blessed and/or requested—because it means you aren’t burdened with telling people over and over again. This might look like asking one really thoughtful coworker to quietly tell all your other coworker pals that something bad is happening, or asking your BFF to be the one to inform your extended friend group about your divorce news. If you go that route, you may also want to ask the intermediary to share your expectations about privacy and further discussion, like so:

“They asked me to share this with you.”

“You should definitely still feel free to reach out to them.”

“They know I’m telling you but would prefer not to talk about it this weekend at book club.”

Dealing with Nosy Folks

If someone starts asking for a lot of details or trying to engage you in a way that you’re not comfortable with (which may or may not be rooted in a genuine desire to help), here are some responses you can try.

What to say

What to say

“I don’t really want to talk about it, to be honest. Can we change the subject?”

“I’d really prefer not to get into the details. Let’s move on!”

“Honestly, the thing I need right now is to talk/think about it less. So, I’d love to hear what’s new with you!”

“Oh, that’s not a good brunch conversation.”

“I’m actually finding this conversation pretty overwhelming and would like to take a break from it, please.”

If you can, try to keep your tone neutral; they’ll likely be embarrassed, and dealing with their defensiveness or a big wounded shame spiral is the last thing you need right now. Of course, if they really won’t cut it out or you just don’t have it in you to be gentle, it’s OK to be less gracious in your response.

Here’s what you might say if a sharper response is called for.

“That’s actually a really personal question and I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Wow, that’s a really inappropriate question.”

“That’s a really strange thing to say to someone in my situation.”

“That’s a really hurtful thing to say. What the fuck?”

[Deep frown, scowl, side-eye, or some other form of body language that communicates “Oh, absolutely no.”]

Ultimately, what you choose to share, who you share that information with, and how you communicate it is super personal and completely up to you. Figuring out what level of vulnerability you’re comfortable with in different relationships takes experimentation and practice—and might change over time, or depending on what exactly you’re dealing with.

Sometimes, being honest can feel like self-care; other times, it might feel like a burden. But when I’m struggling, I find it helpful to simply remember that I have a choice, that I’m allowed to give a candid answer to “How are you?,” that being vulnerable isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition, and that being a little more honest can actually make me feel a lot better.

Accepting Help

If you need to get better at accepting help, you can follow a similar formula to the one I mentioned in Chapter 2. Accept help from strangers when it’s offered, and then build up to accepting help from people you know when it’s offered. Or, you can take this shortcut: When someone says, “Let me know if you need anything,” let them know if you need anything.

If you’re not sold on this idea, allow me to address some of the common excuses people give for not allowing other people to show up for them.

Reason: “They didn’t really mean it.”

Counterpoint: They did, in fact, really mean it! But also, what’s the worst that could happen if you follow up with, “Hey there, you told me a few weeks ago to let you know if I need anything, and there actually is something I could really use right now”? There’s no harm in taking people at their word in this case. If they didn’t mean it, well . . . they’ll learn a valuable lesson about not letting their mouth write checks that their ass can’t cash (and you’ll learn a valuable lesson about that friendship).

If you’re worried that what you need in this moment is too big or burdensome to ask of this friend, think back to the frientimacy triangle and the levels of friendship from earlier in this chapter. Is this a level 3 friend? If so, then sure, it might not be the best idea to ask them to come to your doctor’s appointment and hold your hand during the exam. But it might be perfectly OK to ask your level 6 friend who has always demonstrated kindness and thoughtfulness to give you a ride to your doctor’s appointment. Don’t get me wrong: It’s great to be considerate and think about whether you’re asking too much of other people. But so often, this results in our never allowing anyone to take care of us, and shouldering these tasks entirely on our own.

Reason: “The thing I need is weird or unconventional and they’ll think I’m a freak if I ask for it.”

Counterpoint: Humans are smart and capable of nuance. I genuinely believe that most people would rather do the right thing for you than whatever society deemed “right” fifty or a hundred years ago. Even if they’ve never been asked to do something “unconventional” for a friend in need before, they will understand if you say, “This might sound strange, but I could really use someone to come keep me company while I do my dishes and laundry. My place is a mess, I’m overwhelmed, it’s giving me a ton of anxiety, and I just need someone to be here with me while I deal with it. I’ll treat you to pizza to make it worth your while.” They may even be flattered—because you’re showing that you trust them and are willing to be vulnerable with them, and letting them know that they too can ask for something unusual when they really need it.

Reason: “I don’t actually really need help, I’m fine.”

Counterpoint: You’re not fine.

How to Tell Someone Their “Help” Is Extremely Not Helpful

When you are going through a difficult time, people will likely attempt to support you. And some folks will, inevitably, get it wrong. If someone else’s behavior is making your bad situation worse, the best thing you can do—for both of your sakes—is to gently correct them and communicate that what they are offering is actually not what you need right now. If you want, you can explain why—a generous move that may ensure they don’t make the same mistake in the future, with someone else—but you don’t have to.

What to say

What to say

“I really appreciate how thoughtful you’ve been since I told you about my situation; it means a lot to me to have a friend who cares about me so much. But right now, I’m feeling a bit overwhelmed by these efforts to make me feel better. Could I ask you to stop fussing over me and instead give me a little space? I promise I’ll tell you if I need something.”

“I know some people in my situation find anecdotes like the one you just told me helpful, but I find them really stressful and scary. Could I ask you to not share stories like that with me in the future?”

“To be honest, I’m not in a place where I’m ready to look at the positives of this situation just yet. I’m still really hurt and angry, and I just need to be hurt and angry for a while.”

“I know you mean well when you say, ‘He’s in a better place,’ but that phrase isn’t helpful or comforting to me right now.”

“Can I ask you to do me a favor and stop sending me articles about using crystals to treat cancer because ‘oncology is a scam’? These articles aren’t helpful to me and are kind of stressing me out.”

And if it feels right, you can add something like:

“What I do need right now is [a hug/the name of a good lawyer/someone to organize a meal train/not to talk about this when I’m at work].”

In most of these situations, it’s best to focus on yourself and your preferences instead of criticizing the other person’s behavior. Because in a lot of instances, the person won’t have done something universally wrong; they will simply have done something that you don’t appreciate. You know what they say: One person’s “how essential oils cured my cancer” article from alternativehealingmooncircle.net is another person’s treasure!

It might also make sense to ask a trusted third party to intervene on your behalf, particularly when you’re dealing with something really serious. That might sound something like this:

“Hey, Ash, it is so incredibly kind of you to offer to sing at the memorial service on Saturday, but Kyle has reiterated to me a few times that the service is meant to be family only. The best thing you can do to be supportive right now is to respect their wishes.”

If the person who is missing the mark is a close friend, you might want to be more direct and vulnerable—because not saying anything can do long-term damage to the friendship, and because you (presumably) do want and need their support in a different way right now. In that case, you might say something like this:

“Shawn, my miscarriage has left me completely devastated. I’m angry and heartbroken and furious, and hearing you say ‘everything happens for a reason’ makes me feel the complete opposite of supported. Please don’t.”

“I know you’re trying to cheer me up by telling me to focus on the positives of getting fired, but it’s actually coming across as dismissive because I’m still really upset. Can you please just be upset with me for a little while?”

“Hey, I know you mean well by sending me these articles related to my diagnosis, but they are actually making me spiral the fuck out. I’d like to request a break from all cancer-related literature until further notice.”

They might honor your request! They might not! But at least now you can feel less guilty about ignoring their daily affirmation DMs.

How to Vent Responsibly

When you’re going through a difficult time, venting can really help. Therapist Ryan Howes says that venting is really about processing. You haven’t come to any real conclusions yet; you just need to get your thoughts out of your head, and you need a warm body to listen. Venting tends to feel good; it helps us name what happened and give it a narrative structure, which is really powerful. But it’s also something that we can easily get lost in, draining our energy reserves and alienating the people who are listening to us in the process.

If you’re worried about venting too much and exhausting your friends, here are some tips that might help.

Let people ask you how you’re doing.

When you’re dealing with a lot, it’s easy to blurt out the latest update to the first person you see without so much as a hello. If you’re worried about falling into that trap, consider holding off until someone actually says, “How are you?” or “How’s everything going with [situation]?” Being asked still isn’t a free pass to dump on them for the next three hours, but this is an easy way to keep your urge to unload in check, and to make sure your friends are interested in your latest download.

Explicitly ask for permission to vent—even if you just want to vent via text.

If you need a friend to lend an ear, consider requesting it in a more formal way. Scheduling time to talk or text about a specific topic isn’t silly; it’s courteous. As therapist Andrea Bonior says, “Texting lets us place something—immediately—into someone else’s consciousness, whether they want it there, and are adequately prepared to deal with it at the moment, or not.”24 Texting something like “When you have a moment, I’d love to talk with you about the latest in this Sam situation” or “If you’re around later and up for it, I’d like to scream about the Sam situation” will go a long way toward communicating respect for their time and energy. (And do be specific about what you want to discuss; just saying “Got a sec?” or “Are you busy?” isn’t cool.) It’s entirely likely they’ll respond, “I can talk now—what’s up?” but they’ll still appreciate that you asked.

If you aren’t looking for advice, say so.

In general, our loved ones want to be helpful and offer solutions to our problems . . . but jumping right to solutions can inadvertently communicate “I don’t want to hear about this anymore; I want to fix this so you’ll shut up about it”—which is maybe not what you want to hear in that moment. So if you know you simply need to vent, or that you aren’t in a place to consider what to do next, tell the other person that up front.

Don’t outright reject all suggestions and attempts to problem-solve.

This might seem at odds with what I said a second ago. And it kind of is! Here’s the thing: Wanting to vent and be validated is totally fine. But only venting, and shutting down whenever the conversation turns to the topic of possible solutions? Not so fine! It’s frustrating to listen to a friend talk endlessly about the same topic, particularly if they are refusing to acknowledge their part in the situation or do anything to feel better. Of course, sometimes there isn’t anything you can do to make things better. But at that point, talking about it for three hours isn’t really making it better either.

Consider the forty-five-minute rule.

A couples therapist once gave me this very good advice: If you’re having an argument or intense conversation, take a break after forty-five minutes. After the forty-five-minute mark, she said, people tend to be too emotionally exhausted to have a productive conversation; a twenty-minute break (at minimum!) can help everyone process and reset a bit. Putting this advice into practice made a huge difference, and I now try to apply it to any negative conversation. Aside from being good for the listener, it’s good for you, too. Because even if you aren’t arguing, you’re still depleting your energy (and probably starting to lose the thread of the conversation) when you vent for that long. So keep an eye on the clock, and remember: There’s a reason most therapy sessions are only fifty minutes long.

Notice if you are repeating yourself.

Ryan Howes says if you find yourself saying the same thing over and over again (or the person you’re talking to keeps responding in the exact same way), you miiiight be ruminating, which can be pretty tiresome for the other person. If you’re just cycling through the same few exchanges (“This is bad! I’m so mad!” “Ugh, I know! It’s so bad!”) and neither of you is bringing up new information or insight, consider wrapping it up soon. Of course, there are exceptions to this, and sometimes a situation is so terrible or tragic or unfixable that all you can do is repeat, “This happened and I’m so upset!” while your friend nods sympathetically and says “It’s awful; I’m so sorry.” But that shouldn’t be the norm in most conversations. So if you’re just rehashing the same points—or if your friend is looking/sounding bored—it might be time to call it quits.

Try not to pre-vent.

Pre-venting is when someone says, “I’ll tell you more about this tonight” . . . and then immediately launches into telling you now . . . and then still wants to discuss it in full when you see them later that night. It’s a variation on repeating yourself, but it can be less obvious because some time passes between the initial conversation and the later one. But if you’ve already established you’re going to talk at not-now-o’clock, try to hold off on emotion-dumping before then. And if you do find yourself getting into the whole story (or, say, 75 percent of it) now, recognize that you don’t really need to rehash or repeat the same details later.

Consider journaling.

I wrote an entire book about journaling, so I admit I’m a bit biased, but the health benefits of journaling are well documented. Dumping your thoughts on a page allows you get everything out and helps you process what you’re experiencing. Set a timer for twenty minutes—any longer than that can actually lead to ruminating—and write freely, without worrying about punctuation, spelling, or the “quality” of the writing. Your writing doesn’t need to be “interesting” because no one is ever going to read it. (You don’t even have to reread it later!) You might find you feel a lot better overall, and that your urge to vent to a friend has mysteriously disappeared.

Give your friend time and space to talk about their life.

I’m of the belief that not every conversation with a friend has to be perfectly balanced in terms of who is talking and who is listening. We’ve all had days when we don’t have much to talk about and a friend has a lot going on, and we’re perfectly happy to listen while the friend vents, and then end the phone call there! It’s fine! But. But. If you only ever contact your friends to vent—or if your “How are you doing?” is perfunctory and communicates “I know this is the correct thing to say” instead of sincere interest—your pals are going to catch on. So be sure you’re leading with “How are you?” sometimes (before you’ve talked about yourself) . . . and actually listen and engage when they answer. And if you know you’re only going to hang out for an hour, remember to cut yourself off after twenty or thirty minutes so they have a chance to talk, too.

Do Even Less

You already know how much I believe in the importance of doing less. When your life is falling apart, might I suggest . . . doing even less? The good news about being in crisis is that you’re allowed to opt out of normal activities. You are allowed to cancel plans; to ask for an extension on a deadline; to take a day off; to cry unexpectedly; to not be your best self. When you’re feeling overwhelmed or guilty, remember: This is exactly why the phrase “family emergency” exists. The emergency is here; it’s yours and it’s happening right now. It’s easy to lose sight of this in the moment—to tell yourself that “real” trauma is something that happens to other people and not to you (especially if you don’t want to admit that what is happening is really, really bad).

Instead of assuming you’ll be able to keep up with your life as normal, try starting with the opposite belief: that you’ll be able to do nothing. Don’t be surprised by the fact that you can do even less right now; rather, let yourself be shocked and proud when you can do anything. Lower your expectations, lower your standards, lower your bar. Do even less.