Chapter four. Producing Movies Inevitably Gets You Stoned (And Is Really, Really Hard) *or A Union Dose of Some Shirley Jackson Optimism Goes a Long Way

CO-PRODUCER: Sometimes connotes an involvement in financing the film. At other times, it can be defined as a producer with less power than those under the plain ol'“Producer” credit. In other words, more of a catcher than a pitcher.

Synonyms: One of the other producers

Example:“If the job of co-producer is anything like the job of co-author, it must suck ass.”2

-----------------------Original Message-------------------------

From: elinor@repress.com

Sent: January 9, 2009 4:58 PM

To: Lloyd Kaufman < lloyd@troma.com>

Subject: Louis Su

Dear Lloyd,

I like how you set the book up with your talk about the 1969 Mustang, the different producing models and then segue into your early directing/producing career. You also present an informative myriad of ways to obtain your producing skills—via school, working on movies, etc. I’m not really clear where Louis Su fits into the whole picture, but anything to deter our young producers from considering pornographic filmmaking as a viable gateway to a producing career in this modern age!

Perhaps in this chapter you could talk about some of the challenges that producers face?

Can’t wait to see more pages from you soon!

Best,

Elinor

Sent via BlackBerry by AT&T

-------------------------End Message----------------------------

I scrolled through this message on my BlackBerry as I waited for my luggage to plop itself onto the carousel at JFK. Pattie and I had been visiting our daughter Charlotte in Yemen, which is, yes, as I recently learned, a real country. While watching the hypnotic spin of other people’s suitcases, I thought about what Toxie would do if he were in Yemen. And then I was jarred by a loud buzz from my BlackBerry again.

-----------------------Original Message-------------------------

From: bigfriggindeal@aol.com

Sent: January 9, 2009 5:01 PM

To: Lloyd Kaufman < lloyd@troma.com>

Subject: Re: Interview with John Carpenter

Dear Lloyd:

We got your interview request and while John is flattered you thought of him, unfortunately he will be unavailable to participate. Best of luck with the book!

-Max

Assistant to John Carpenter

-------------------------End Message----------------------------

Pattie jabbed me with her elbow and told me to stop exhaling so noisily. I two-finger typed a quick response to Max:

-----------------------Original Message-------------------------

From: lloyd@troma.com

Sent: January 9, 2009 5:04 PM

To: John Carpenter < bigfriggindeal@aol.com>

Subject: Re: Re: Interview with John Carpenter

Thanks, Max. I do come to LA at least once a month on business. Is there a chance Mr. Carpenter might be available to be interviewed for my book on another date? This book, my fourth, is a very important project for educating young filmmakers about being true to their own selves … . Thanks!

This message was sent from Lloyd’s phone.

Please forgive typos!

-------------------------End Message----------------------------

By this point, my luggage was doing laps on the carousel in front of me. I heaved it off and bundled myself up to brace myself against the heartless NYC winter cold ahead of me on the other side of customs. My pants started buzzing again. I got a little excited, then smiled and breathed a sigh of relief as I realized it was just my BlackBerry. I pulled off a glove and took it out again to find an instantaneous message from Mr. Carpenter!

-----------------------Original Message-------------------------

From: bigfriggindeal@aol.com

Sent: January 9, 2009 5:07PM

To: Lloyd Kaufman < lloyd@troma.com>

Subject: Re: Re: Re: Interview with John Carpenter

Hey Lloyd,

John’s schedule is pretty packed for the foreseeable future, so it looks like it won’t work out. Sorry about that. But again, best of luck with the book! And feel free to let me know when it’s heading to press -- I’d love to read it!

-Max

Assistant to John Carpenter

-------------------------End Message----------------------------

Oh, yeah, like I was going to send a copy of this book (for which my publishers will make me shell out $19.95) to John Carpenter’s handler because he’d “love to read it.” You’d think that someone who’s been alive and thriving in the business for nearly four full decades running his own independent film studio would occasionally get to pull some big “muckety-muck”Halloween strings, but alas, alack, such is not the case. After 40 years of producing movies, it’s never too late to be insulted—remember that, dear reader.

I started thinking about The Lottery, that short story by Shirley Jackson that they make you read in grammar school. If you’ve never been subjected to it, consider yourself lucky. It starts off great. It’s a small town, a beautiful hot summer day in June—it’s obviously a place where everyone knows everyone else. While reading it, you might picture red-checkered picnic tablecloths, ice cream, hot dogs, friendly greetings at the local store, beautiful nebulous hairless boys. Then you realize it’s the day of the annual town lottery. Wow! The lottery! Someone’s gonna win big today! What’ll they win?!

There’s a dramatic, suspenseful buildup as every Tom, Dick, and Harry waits to see whether his or her number is going to be called. Finally, a winner is chosen. Lucky Tessie Hutchinson. And what does she win? She wins the opportunity to be stoned to death—literally stoned to death with rocks by her fellow town residents. This beautiful story ends with Tessie’s neighbors, all sexes, ages, and sizes, slowly but surely pelting her to death, bit by bit, stone by stone.

The Ultimate Self-Stoning Job, or There’s a Hole in My Begel Bagel, Man: a Short History of David Begelman

Some people do anything to climb to the top of the producing food chain, only to be stoned to death. Take David Begelman, the infamous Hollywood producer who, in 1960, co-founded the Creative Artists Agency (CAA), a talent agency that represented completely unknown actors and directors such as Woody Allen, Marilyn Monroe, Peter Sellers and Richard Burton, to name a few. After 13 years of agent-ing, he left CAA to take over Columbia Studios, where he produced such movies as Close Encounters of the Third Kind (a movie that can’t even begin to surpass Troma’s Invasion of the Space Preachers in its level of importance and sheer number of fans).

At the top of his game, Begelman—the virtually and ultimately unheard-of success story of man-turned-agent-turned-studio-mogul—suddenly found himself at the heart of several embezzlement and check forgery scandals. One of his first victims included his client Judy Garland (while he was at CAA), with whom he may or may not have had an affair. 3 He allegedly titled a 1963 Cadillac convertible that had been given to her as part of her compensation for appearances on Jack Paar’s4 television show to himself and then also claimed that Judy had blackmailers demanding $50K for naked photos of her getting her stomach pumped after a drug overdose. Although the story about the photos and money were totally fabricated, her drug problem was not. Rather than let the world potentially see incriminating photos of “Dorothy Gone Wild,”5 Judy paid up and Begelman walked away with $50K. 6

4Jack Paar was an above-par American radio and television talk show host who hosted The Tonight Show from 1957 to 1962.

5Of all her roles, singer/actress Judy Garland is perhaps most famous for playing Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz.

6Now, if he had used that $50K to go produce his own damn movie, he’d be a hero in my book. And by “my book,” I of course mean this one that you are holding in your sweaty hands. However, he probably just bought a boat or something. Yawn.

Nearly 15 years later, actor Cliff Robertson7 received a letter from the IRS stating that he had received $10K from Columbia Pictures. Robertson had never received the money. Upon investigation, a check forgery for $10K was traced to Begelman. Robertson shared the honest story of his victimization and was silently blackmailed and stoned by the Hollywood community for revealing the truth about Begelman. He spent most of the 1980s getting a tan rather than working on movies.

7Cliff Robertson is an Oscar (for Charly, in 1968), Emmy and Lifetime Achievement Award–winning actor with his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, now best known for playing “Uncle” Ben Parker in the Spider-Man movies.

To add insult to injury, Begelman lied on his resume and said he was a Yale alum. Imagine! Trying to pass himself off as a student of my alma mater! Next thing you know, George W. Bush8 will say he graduated from Yale! 9 Begelman even went on to run MGM and Gladden Entertainment, but was never able to repeat the success he enjoyed while at Columbia. By 1995, Begelman declared bankruptcy and committed suicide in a hotel room in Century City, Los Angeles. 10

8George W. Bush, arguably the greatest U.S. president since Abraham Lincoln, coined the phrases “Mission accomplished!” and “Bring it on!”

A Lottery Ticket With a Big “?” on The Prize

Now, let me tell you—because I feel it is my duty to be frank and honest with you—producing movies is a lot like winning a fucking Shirley Jackson lottery in which you may not want to participate. Begelman’s downward career spiral was self-inflicted, but often—no matter how experienced you are or what level you are at—obstacles are going to arise. The producers who make it in this world are the ones who realize there is a hell of a lot of sacrifice involved. And, as Reed Morano emphasized at that star-packed Chinese restaurant in Chapter 3, this is an enormously collaborative business where you have to rely on and work with others—people, equipment, companies. As a successful producer, you think you’ve won big; you’ve made your dream come to life, but you might just end up getting completely stoned11… in fact, it’s pretty much guaranteed that you will get stoned. Let’s just hope it’s not… to death. In fact, my assistant Matt Lawrence can tell you that I consistently get stoned on a regular basis. And I’m definitely not talking about the herbal kind of trip.

11FOOTNOTE GUY: I’m stoned right now.**INDEX GYNO: I’d like to get Oliver Stoned!****FOOTNOTE GUY: I don’t get it.

Matt Lawrence and Resident Troma Bitch

Who is Matt Lawrence?

My name is Matt, and I am Lloyd’s assistant here at Troma. Lloyd is currently asleep at his desk, some partly masticated Twizzler drooling out of his lips, with an empty bottle of Popov and some Judy Garland songs playing on his iPod. With a comatose Kaufman here and a book deadline looming, I suppose it might be Good Samaritan–ly of me to continue where Lord Kaufman left off (or passed out). How about a story?

Recently, Lloyd was given the opportunity to interview John Patrick Shanley for his (i.e., this) book. Yes, you heard right: John Patrick Shanley, famed playwright, screenwriter and filmmaker of Doubt. Award-winning, respected, brilliant—an artist in every sense of the word. Recipient of an Oscar, some Tonys, the WGA Lifetime Achievement Award and oh, the uh, Pulitzer Prize for Drama. So many awards that the man needs his mantelpiece reinforced.

On a chilly, snowy, flurry-filled Friday afternoon, Shanley greeted and ushered us into his spacious, airy apartment, the entire second floor of a beautiful building not far from Union Square. Immaculate and pristine, the walls of each room were painted a different striking, vibrant color. The smell of the apartment was intoxicating. This is how success lives, I thought. In awe, I knew that it’s not everyday one gets to share the same room with an Oscar winner. Of course, I had already met Yacov Levi, who wrote and directed the Troma release The Killer Bra, a true honor in itself, but Shanley had worked with the likes of Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep and Philip Seymour Hoffman. And here he was, agreeing to be interviewed by Lloyd for Produce Your Own Damn Movie, the book and DVD box set!

I quickly set up the camera and audio as Lloyd made (awkward) conversation with Shanley. About five minutes before shooting, Lloyd proffered hard copies of the interview and personal releases12 (which had been e-mailed ahead of time to Shanley). Lloyd also presented Shanley with a DVD of his (i.e., Lloyd’s) newest film, Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead, as a token of his gratitude. Shanley perused the release for a few seconds, then eyed the Poultrygeist DVD cover of its skeleton head with a protruding ax, a protruding chicken monster and a protruding eyeball for a quiet five seconds before saying, “You know, I don’t know if this is a good idea … I think … maybe—I need to speak with my agent.”

12PRODUCING LESSON #155: Always get releases and contracts signed before you begin filming. Logical enough, right? But you’d be surprised how often films, both big and small, begin shooting with contracts not yet signed. In fact, on the megabudget picture The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (a Bruckheimer production), filming is currently going on and—according to sources—even the script has not yet been completed. As a result of this insanity, departments apparently are laying off people until the “producers” see where the script is going.

The sound of the air was sucked out of the room. I was shell-shocked. I immediately looked over at Lloyd, our fearless leader, a pioneer in the business for the past 40 years. Poor Lloyd—poor charming, brilliant, generous and handsome13 Lloyd. The president of Troma Entertainment’s mouth was agape and his ass lay in his arms, courtesy of Mr. Shanley. Shanley kindly ushered us out, elaborating, “You know, when I see a DVD cover with an eyeball popping out, I start to wonder… .” Fair enough, Mr. Shanley. 14

13EDITOR’S NOTE: Lloyd, stop it! Matt’s original adjectives read “nebbishy, often smelly and dumpy.”

14Although, as many Tromites know, the Poultrygeist DVD cover is actually quite benign by today’s standards. But maybe the Shanmeister is straight-up old school?

Lloyd whined, considering the possibility (i.e., the reality) that Shanley did not know who he or Troma was before sitting down for the interview. It dawned on me that this opportunity had been both Lloyd’s and my very own lottery. I had thought working for Troma had finally paid off, as I would now be hobnobbing with the artistic elite. Instead, I found myself packing the camera (i.e., paper) bag with the equipment that we never even used to almost interview a famous director who had no idea who we were. And for Lloyd, a man who has influenced some of today’s biggest filmmakers and been imitated by countless others, it was a private stoning as the result of one lousy DVD cover. Shanley hath casteth-ed a pretty heavy stone. Together, Lloyd and I returned to the Troma offices that afternoon, our tails between our legs. 15

15And, to add insult to injury, Lloyd forgot his hat at Shanley’s apartment. Whether this was a ploy to get back into the Shanley compound or Lloyd is truly senile is up for debate.

I can tell, weeks later, that Lloyd is still bothered by the events that transpired that unfortunate afternoon. Sadly, his neck and back are still tense as I give him his daily full body massage. Who says that working at Troma doesn’t have its perks?

P.S. Dear Mr. Shanley,

If you are reading this sidebar, Lloyd made me write it. I think you have great hair and I loved the way your apartment smelled of fresh apricots. I wish I were there now. If you’re looking for a personal assistant, assistant director (Doubt 2: Doubt Harder), driver, whatever—I’m your man!

Please get me out of Tromaville.

P.P.S. Dear Lloyd,

If you read my postscript to Mr. Shanley, it’s all a lie. However, as a young filmmaker, I can’t afford to burn any bridges, regardless of how I truly feel. Working with you has been incredibly enlightening and I am forever grateful for the wisdom you have imparted to me. I love you.

P.P.P.S. Dear Mr. Shanley,

Ignore my last postscript. I need to cover my tracks and blow smoke up the old man’s ass so he doesn’t fire me.

P.P.P.S. Dear Lloyd,

I’m sorry you had to find out this way.

Now, you may be thinking to yourself, “Of course that would happen to you, Lloyd.” But wait: Lloyd Kaufman getting kicked in the balls may not seem odd, but it happens to everyone. Even people who are actually respected in the industry. Read on:

LLOYD KAUFMAN: What was the third Oscar-winning movie you did, in addition to Gods and Monsters and Crash?

MARK HARRIS: Well, that was an interesting experience. It was called Million Dollar Baby. While I was doing Crash, it was given to Clint Eastwood as an actor, but he said he would only do it if he could direct. The production company approached Paul Haggis to ask if he would step aside as a director and let Clint come on and direct it. Paul acquiesced and gave the movie over and we made a lot of money out of it. It came out before Crash, though—we were halfway through it when that was being made. Everything has its own destiny.

LK: Today, I might give a Production Manager a producer credit, but I notice today regarding Hollywood movies, there are 1,400 producer credits on them. What is that about?

MH: They say “it takes a village to raise a child.” Well, it takes a village of producers to produce a film. There are many different ways to get a cast—one of these is to make an actor a producer. A writer can direct, but you can also give a writer a producer credit!

LK: Is that what they do on television?

MH: Well, television is a different medium—the writers are the executive producers. The executive producers in film take that credit because they are the money-makers, or they brought in a piece of talent. We had a group of people on Crash. Bobby Moresco and Paul Haggis wrote the script and took very little money, so I was the only producer among the three of us, but we all decided to produce and then Cathy Schulman came on because she was part of Bob Yari’s group16 and then we got Don Cheadle as an actor to produce.

LK: So there were five or six producers? That’s nothing.

MH: Yeah, for today that’s nothing, but without one, none of the parts would fit.

LK: Many young people want to win Oscars; what do they have to do as producers to win an Academy Award?

MH: The folks who deal with the Oscars are a club called the Producer’s Guild and the Academy of Arts and Motion Picture Sciences. They have their membership and this is not a public election. They make their own rules. They look at who qualifies most out of their freely flowing subjective criteria.

LK: Meaning that they choose whom of several producers gets to go on stage to accept an Oscar or other award in front of billions of TV viewers around the world?

MH: Yes, right. That doesn’t mean the others don’t deserve it. It just means this club made the decision.

LK: In your case, what happened?

MH: I was shut out of the opportunity to go up on stage, even though I was the one who said Crash shouldn’t be a TV show—we needed to make it as a movie. I got it to all the financiers and was involved in the rewriting, budgeting, editing, and casting. Do I think I deserved to be acknowledged? Absolutely. Did I get to do it? No. That doesn’t take away anything I did.

LK: Was there an explanation?

MH: Yeah, they didn’t feel I did enough. They gave it to Cathy Schulman. She did more in the latter part of getting the crew and all that. She was a good Line Producer and they also gave one to Paul, because he was involved with everything. That’s the way it went. There were many people in the Academy who were upset about how I was treated.

LK: Have they changed the rules?

MH: I don’t know. I’m like Groucho Marx. If anybody wants me as a member, I don’t want to join the club.

You Don’t Have to Be a Shithead to Be a Producer

Mark Harris is a pretty classy guy. 17 First of all, he’s an Oscar winner and he agreed to be interviewed by me, whose highest award is the Franklin, Indiana “B Movie Celebration Lifetime Achievement Award.” Second, I shot the first 20 minutes of the Mark Harris interview with my video camera in the “off” position, only to have David Chien point out my error. Mark kindly agreed to start the interview over again from the beginning. Third, once we finished the interview, I had offered to take Mark to dinner as a thank-you. I was worrying all day about coming up with money to pay for the valet parking for my rented Hyundai among the Bentleys and Rolls Royces at Mozza. 18 But Mark was generous and chose Froman’s Deli down the road. The two of us dined royally for about $35 bucks and had fun bantering with Brenda, our waitress!

17INDEX GYNO: I give you shit all the time, but you’re not so bad yourself, Lloyd. You have to admit. As much as we all want to, especially those who have had the misfortune to work with you for extended periods of time, I don’t think anyone could not like you. In fact, you’re a pretty darn loyal supporter and cheerleader for life. Elinor was totally wrong about you.**EDITOR’S NOTE: Index Gyno has contempt for you, Lloyd. How low can you go—even pretending to be the Index Gyno all the way down here?!

Which Way Went Blair Witch?

So you see, winning the producer lottery—making a successful, award-winning movie—can be disturbing. Sweet, but it can turn sour quickly. Mark Harris continues to produce great movies. The people who made the hit mockumentary The Blair Witch Project have not been so fortunate. 19 These young folks came up with an absolutely brilliant marketing plan that sold the movie through websites, blogs and viral marketing techniques that left you wondering if the Blair Witch story was fact or fiction. They hit the lottery and became an overnight sensation! And then, they couldn’t do it again—and, in my highly regarded opinion, the fault lies totally with their distribution company, which—as I gather—screwed them over by ignoring the strengths of the campaign on their first film. I believe that they were sucked dry, stoned to death—brilliant young guys and gynos who changed the face of filmmaking and marketing. They were brought down by a combination of mediocrity, incompetence, and greed in the upper echelons of the film business. As talented as they were, having won the producer lottery, their film careers were stoned, like an unfaithful Muslim woman under Taliban rule.

19FOOTNOTE GUY: Actually, Lloyd, there was a Blair Witch Project 2, it’s just that no one’s really heard of it. Kind of like me. No one’s really heard of me, because you keep trying to pretend I don’t exist. But I do exist, Lloyd. I do. And I’m sooooo lonely.

It’s been a tough lesson that you cannot control everyone and everything around you as a producer. It’s a lesson I stone myself with repeatedly. There are too many rules and too many unions that were supposedly formed to protect you but end up distracting you and sending you farther and farther away from the piece of art you are trying to create. What you can control is the awesomeness of the script that gives you the story you are going to tell, whether it is your own or that of someone you are collaborating with. Also, you need to control the people you select to work with as your creative team (from the actors down to the crew) and the standards by which your movie will operate.

Climbing High Up at IHOP: lessons from Stan Lee

As a producer, if you want to have a meeting, you need to hold the meeting in a location that will allow you to focus on the meeting. Stan Lee20 introduced me to the beauty that is an IHOP. 21 At an IHOP establishment, there is no need to fuss with valet parking (like at Mozza) and worry that your car seat is going to get jacked too far forward so you won’t be able to slide it back into its perfect spot for your legs or that some bored guy on the late night shift is going to swipe your last condom stashed away in the glove compartment for last-minute emergencies, or, in my case, just rare luck. Furthermore, no matter what time of day—be it morning, noon or night—the IHOP is serving exactly what you need.

20Stan Lee is an American comic book legend, icon, writer, editor, former president and chairman of Marvel Comics, and co-creator of Spider-Man, Daredevil, The Hulk, The Fantastic Four and The X-Men, to name a few.

When that hamburger with fries arrives, well, the ketchup bottle is already there, and it is always full. If, instead, those buttermilk pancakes with strawberries on top slide under your nose, well, the maple syrup is within an arm’s reach, along with boysenberry and blueberry as well—more colors than a gay rights parade! The Sweet’N Low and the sugar, salt and pepper, cream, butter, whatever your condiment22 needs are, they are met, and they are met immediately, within near nanoseconds. IHOP lets you concentrate on your movie script or meeting, because everything you need is at your fingertips. 23

22INDIGNANT FOOTNOTE GUY SAYS: It’s terrible how they’re tearing down all of the landmark buildings and building condiments.

23This portion of the book has been sponsored by IHOP! Good food, good people, good marketing.**EDITOR’S RESPONSE: Neither Focal Press nor its parent company, Reed Elsevier, have received any compensation from IHOP for this thinly veiled advertisement. Why do you always put me in situations like this, Lloyd?

|

| Figure 4.2. |

| Why are pop culture legend Stan Lee and brilliant musician and composer Dennis Dreith (right) ruining their reputations by being photographed with LK and a Poultrygeist poster? |

All of this exists to let your creativity flow forth effortlessly, beautifully, juicily, just like the sirloin steak for $6.99. Nothing can stop you and you can focus on what really counts. Yet, if you choose to meet at that “impressive” three-, four- or five-star restaurant offering a fine selection of “today’s specials,” you are bound to be interrupted countless times for your order of coffee, water and choice of dessert, not to mention the requisite “Are you still working on that?” (when your meal is still clearly only half-eaten) and then, before you can swallow a bite or muster an answer, the “Is there anything else I can get you?” and so on and so forth.

That is not how you should run your producer ship. Put all the people and elements in place and at arm’s length to help you do the best possible job you can. Create your own damn cinematic IHOP!

Stan Lee taught me this, and for that, I am forever grateful to Stan the Man. “Excelsior!”24

Who is Terry Jones?

Terry Jones, one of the members of the famed comedy group Monty Python, is a world-class director, screenwriter, actor and author, as well as a Chaucer scholar. His most renowned works are Monty Python and the Holy Grail, 25 Life of Brian, and The Meaning of Life. Subsequent to his Monty Python films, he directed Erik the Viking, Personal Services, and The Wind in the Willows.

En route to taking out the garbage, Terry Jones walks by the loo and hears the chain being pulled, the perfect moment to receive a phone call from me, cinema’s ultimate proprietor of human waste and bodily fluids. The two of us then had a conversation about two different types of producers.

Jones divulged his personal experiences with producers, outlining the differences between what constitutes a “good” producer and what constitutes a “bad” producer. For Jones’ directorial debut, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Michael White, the film’s financier, “foisted” a young producer named John Goldstone on the Pythons. However, the “foisted” Mr. Goldstone turned out to be the “perfect” producer, effectively raising money and creating an efficient and practical structure for the production to follow. Goldstone always trusted the creativity of the director with whom he was working. For example, he would set up casting calls and make suggestions, but never make final casting decisions. Goldstone’s producing style created the ideal environment for Jones and the Pythons. Goldstone would put together the nuts and bolts of the film, while trusting the Python’s directors' aesthetic vision. The six Pythons had a “unified vision,” remarks Jones. “So it would have been impossible for the producer to have the last word anyway.” Goldstone stayed on to produce other Python movies. “Collaboration with a good producer who supports the director’s aesthetic 100% is a great thing.”

Unfortunately, the producer for a recent ill-fated project of Jones thought that he, as producer, would handle the nuts and bolts in addition to being a strong “creative” force. This led to trouble. The UK Film Council supported Jones and his co-writer Anna Söderström’s vision, 26 while the producer only pretended to get behind it. Mr. Bad Producer told Jones that it was going to be a pleasure to work with him, yet continually undermined Jones. Most notably, the production designer was working from the producer’s script and not Jones’s and Anna’s, causing Jones to say, “Producers have no business rewriting my material!”

26Terry and Anna did not originate the script. It was brought to Terry to direct, but the writer did not want Terry and his writing partner Anna to change it. A year later, the writer backed out of the project and it was up to Terry and Anna to do what they wanted with the script. The UK Film Council continued to provide script development funds to Terry and Anna as they continued to work. Unlike the United States, the UK and most other countries have government agencies that subsidize the indigenous and independent arts. However, the United States does have a series of laws, regulations and tax breaks that do help media mega-conglomerates continue their dominance, but nothing specifically allocated for indigenous, independent art.

The producer and his marketing team were also vying for Terry’s main characters to be changed to teenagers. The coup de grace occurred when the producer meddled with a 30-second promo that Terry was preparing for the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. Terry quit and the film officially fell apart. The promo was going to be used to pre-sell27 the film, so Terry wrote and organized the promo, but the producer began to retool, rework, tweak, adjust, or whatever other word the producer might have used to justify unwarranted changes. Jones stated, during our chat, “If this producer interferes with a simple Cannes Film Festival promo, imagine what it would be like if I were to direct the film? I was just lucky to get out before it was too late, because it was obvious the kind of producer I was dealing with up front.”

27More about this in Chapter 6. I hope.

Is there a lesson to be learned from this? Yes! First, the troubled project didn’t originate with Terry, so there was no way he could have final say. If you produce your own damn movie, you are less likely to get stoned to death because you can control the material. And second, if you want to be a strong, creative producer à la Irving Thalberg or David O. Selznick, 28 then be straightforward with your director and make sure that he realizes he is merely a “hired gun.”

28Irving Thalberg (1899–1936) was an Academy Award–winning film producer during the early years of motion pictures; David O. Selznik (1902–1965) was the iconic Hollywood producer of the epic Gone with the Wind (1939), among others.

Who is Danny Draven?

Danny Draven is a producer/director/cinematographer/editor who quickly moved up to the Production Manager/Assistant Director level to produce his own low-budget independent horror films, such as Crypts and Ghostmonth. He is based in Las Vegas. Danny’s book, The Filmmaker’s Book of the Dead, will soon be released by Focal Press.29

29EDITOR’S NOTE: I am appreciative of your plug, Lloyd. I truly am. But it doesn’t really make up for that disgraceful IHOP ad.

When you’re producing low-budget films, you can call yourself a producer, but you’re also doing the job of a line producer. So with my films, I was always not only the producer but also the line producer, as well as the director. But when you’re producing the film, you have to deal with everything. You’ll deal with everything from late actors (I’ve had a few drunk ones) to the cops showing up, the fire department showing up, people wanting to see permits (i.e., “What are you doing here, sir?”) more times than you can count.

On my films, we’ve never been able to afford a production manager, so I end up doing most of the producing work myself. For one, I want to write every check—I want to know where every penny of that budget is going. On these lower-budget films, I don’t trust the line producer enough, because of the circumstances we shoot under—we only have six or eight days to shoot, so I need to know where every $5 and $10 check is going at all times. I have to sign every one of them. And you have to do that, because you have to make sure that every penny you spend is on the screen. You don’t want to be spending $50 or $60 on comforts such as a little refrigerator for your production office—you shouldn’t even have a production office. All money should go on the screen, if you are working with limited means.

Who is Tamar Simon Hoffs?

Tamar Simon Hoffs is a producer/director/writer who rose to recognition with her short film The Haircut, starring John Cassavetes, which appeared as an official selection of the Cannes Film Festival in 1983. Most recently, she directed, wrote, and produced Red Roses and Petrol and Pound of Flesh, both starring Malcolm McDowell.

I’ve made three feature films that all had the same budget: $350K. One of these films was Stony Island, made in 1976. The other was Red Roses and Petrol, made in 2003. The last was Pound of Flesh, which wrapped in early 2009. As a producer on Stony Island, I worked with the director Andy Davis, who taught me my very own invaluable producing lesson #213: you need to have multiple budgets for the movie you want to make. For example, you have your $2 million version, complete with dream cast and union location shoot; the $1 million version of the budget, which calls for filming in far less time; and the $500K version, to be shot on an incredible HD camera. Each time, I’ve ended up with my lowest budget model. And each time, I’ve still been able to make a great movie with wonderful actors that have then gone on to win awards. If you have a good story to tell, you find people who want to work for nothing to tell that story and who are in it for the thrill of making movies. So I always have three budgets—just in case!

The MPAA Lottery

Once you’ve shot your movie, you’ve got to come up with a final cut that the producer and distributor (if you’re lucky enough to be me, the producer and distributor can be the same person) will be happy with (as happy as the director30). Regarding your final cut, one of the challenges that will stand in your way as an independent producer is known as the Motion Picture Association of America, or the MPAA.

30Which, again, if you’re lucky enough, is the same person as the producer and distributor … moi!**FOOTNOTE GUY: You work so hard to be recognized, Lloyd. Just like me! Let’s hear it for the little guy! Anyone?

The MPAA is a group of fascist-loving, homophobic, gun-wielding child pornographers31 in charge of rating movies. They are supposed to rate a movie from the point of view of the elements in it so that the public can learn how much sex and violence is contained therein. The MPAA seem to think this grants them permission to evaluate a film’s artistic contribution. They have a huge double standard, in that they allow movies produced by one of the megaconglomerates to pass through the ratings criteria much more swiftly, with as much of their sex, gore, and violence intact as possible whilst disemboweling an independent film with the same elements.

31EDITOR’S NOTE: This is a false statement. I’m just going to start pointing them out. You have used up all of my patience.

The movies Troma has made for our audiences have had to meet criteria to fit an R rating. The MPAA also won’t even look at a film until it is finished, which too often proves very costly to the filmmaker. Once you’ve made a composite print32 of a movie and then have to go back and recut it, it becomes extremely expensive. It is something that most low-budget independent films can’t afford to do a second time. When you cut the composite film, you have to splice on the picture. The appropriate sync sound is several frames back, so you actually hear it on the projector—the picture and sound are not together. When you join the cut pieces together, the sound is all messed up. It jumps. To fix it, you have to remix the sound tracks, which costs thousands of dollars.

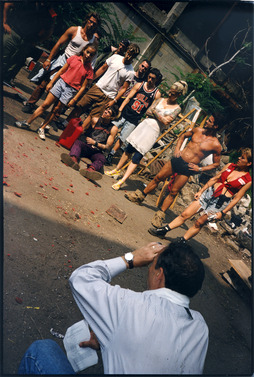

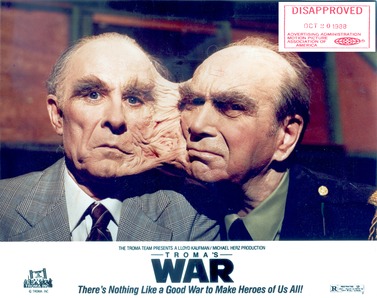

|

| Figure 4.8. |

| Here is a publicity still that the MPAA banned, saying it was “too much” for the American public. |

TakeTroma’s War, one of our masterpieces that was released right around the same time of Die Hard. Die Hard, which came out ahead of Troma’s War, was allowed to keep its significant amounts of serious, realistic blood and violence, but Troma’s War had to cut everything, including goofy slapstick punches and bullet hits—stuff you would see on early morning network news and cartoons33 on television. This ripped the heat out of the movie, not to mention my own heart, and Troma’s War was a flop. Our fans got mad and thought we had sold out. They showed up at our movie and there was no sex or violence. It was all about the contract with our video company: we had to deliver a movie that would get an “R” rating. If we didn’t, they wouldn’t pay us. In other words, we were royally screwed. I wanted to blow my fucking brains out. The president of the MPAA at the time told Michael Herz, in no uncertain terms, that our movie was a no-good piece of shit. 34 So on Troma’s War, we ultimately decided not to listen to the MPAA and instead to deliver the movie as I had shot it and how our video company wanted, saving the pussy version for the theatrical release only.

33There is an added advantage in that early morning news and cartoons on television are often interchangeable.

34The MPAA is never, ever supposed to comment on the aesthetics of a film. So this underscores the arrogance toward independent artists.

Years earlier, Lee Hessel, Executive Producer of Cry Uncle, taught me the trick of obtaining MPAA approval and then putting the footage that was unfairly cut out back in, doing our best to come close to the original running length that the MPAA approved. We got caught with Bloodsucking Freaks, where we re-added 48 minutes to the 54 minutes that had been approved by the MPAA for an “R” rating. If you get caught, as we did, the MPAA can sue you for copyright infringement, that is, using the MPAA letters such as “R” without proper authorization. Our punishment on Bloodsucking Freaks was having to take out advertisements in The Hollywood Reporter admitting our wrongdoing. The MPAA would probably be shocked to see Troma’s gentle, family-friendly movie, Doggie Tails (2003), a cute, charming talking-dog movie for little tikes. Nowadays, films can also be rated on tape, which is a far less expensive process, though we don’t even bother to get our movies stoned (i.e., rated) anymore. We just don’t care about the rating.

But the MPAA favors movies with mega-conglomerate budgets to plaster ads and billboards all over our highways, buildings, trains and buses. The MPAA and their double-standard “stoning” policy is one of the major reasons so many independent producers have gone out of business. 35 Through the rise of home video, Troma pioneered the strategy of having a home video version or even a “director’s cut” version that is separate from the theatrical version. Luckily, Harvey Weinstein36 also used our strategy, but he was powerful enough to really make this happen on a larger scale without getting paddle-spanked.

35Also, the MPAA is currently lobbying in Washington, D.C., 24/7 to get the FCC to destroy the free, open, diverse and democratic Internet that currently exists. The MPAA has officially come out against “net neutrality.” Please go to YouTube and type in “Lloyd Kaufman Defines Media Consolidation.”

36Harvey Weinstein is an American film producer and studio chairman. He is a co-founder of Miramax Films, and today he runs the Weinstein Company with his brother Bob. He is the most beloved man in the film industry—he’s just like Mother Teresa, if she had been large, bit people’s heads off, and shat down their necks.

Who is Paul Hertzberg?

Paul Hertzberg, founder of CineTel Films, is a very successful producer of science fiction and disaster movies, such as Icarus, Bone Eater, and Gargoyle. He is currently developing a movie called I Spit on Your Grave. 37

The biggest mistake I see producers making is falling in love with a project, without regard to how commercial the film is and thereby having limited chances for financial success in recouping the money from investors. That hurts everybody, including the producer who might have gotten a fee out of it, and it makes it harder for him to go to the investors in the future. It’s one thing to follow your vision, but you’d better make sure that there is a marketplace for your project.

I had to join the Director’s Guild of America (DGA) after working on Rocky in order to continue working production jobs on DGA movies. And remember, I was working on Rocky to further my nontraditional film school knowledge and also to put money back into the company that Michael and I were building. However, when we produced a movie, Troma couldn’t afford to hire the required staff under the Director’s Guild of America rules. 39 So I directed under the name of Samuel Weil40 and while in post-production for Troma’s War, the DGA brought me up on charges, or, in other words, tried to kick me out for directing a non-union movie. The New York Daily News had visited the set and printed a huge Sunday feature describing my supposed direction to actors on the set. Like I ever tell actors what to do. 41 Ha!

39Because I was a DGA member, any movie on which I functioned in a DGA capacity was required to be a DGA signatory, which meant that the Production Mangers, Assistant Directors, Unit Managers, and so on would all have to be DGA members, which would have doubled our budget. Also, the DGA rules require all members to eat a baby once a year and sacrifice a 12-year-old virgin boy to the god Ra.

40EDITOR’S NOTE: Does Sammy know Louis Su?* *Samuel Weil was Lloyd’s maternal great-grandfather.*INDEX GYNO: Yes, they are very similar. I found a reference to a mutually shared weekend in Haiti.

41FOOTNOTE GUY: Lloyd is always barking orders to everyone, even me. I get no respect. When Lloyd steps all over the actors, it’s only figuratively. But he steps on me because I’m so small that he can’t see me.

Stanley Ackerman, a turd at the DGA, seemed to enjoy calling our offices and threatening to kick me out and fine me $15K. I was summoned to the DGA New York headquarters and put on trial, DGA-style. Ackerman used the New York Daily News piece as evidence that I was director of Troma’s War. The article described me telling a large, muscular guy with a pig nose to grunt; it then went on to report how I was dissatisfied by the orgasmic noises coming from a big-breasted gyno. I said to those gathered around the table in judgment, “Is this your evidence—your Troma’s War smoking machine gun? If telling a pig-man to snort louder and telling a bimbo to groan is what you gentlemen consider to be directing—if that’s what you believe is directing—then our profession is in deep trouble.” Everyone except Ackerman laughed. I continued: “Michael Herz is one director and the other credited director, Samuel Weil, is not I, but a symbolic name for the Troma-team collaborative effort.” I was, for our purposes, merely acting in my role as producer/director. “I am a strong producer. In the tradition of David O. Selznick, I need to tell the director and actors what to do.” I was exonerated but later resigned from the union.

Years later I lit into a now very old Stanley Ackerman while I was on the dance floor of the annual DGA awards. I was on the arm of my wife Pat, and she almost killed me. The story of my getting pushed out of the union became legendary within the DGA. 42 The DGA has since improved its rules. Now young DGA members routinely take production jobs on other films to learn and advance their producing careers and DGA rules permit them to direct ultra low-budget movies. 43

42I like to believe that the DGA is embarrassed about this matter and the fact that I am a well-known director who is not a DGA member. Producers and directors are often surprised to discover that I am not a member of the DGA.

43The DGA rules, however, still require the annual eating of at least one baby.**EDITOR’S NOTE:—Gasp!

Any union that would do everything they can to stone its members for trying to create a piece of art is not a union that has its members best interests at heart. I understand that Oscar winner Jon Voight44 went “SAG-Financial Core” (wherein you are allowed to be a member of the union and do nonunion work, yet are unable to vote) in order to do a film he really believed in, but one in which the filmmakers didn’t have enough money for a union production. Because of his daring choice, SAG uninvited him from attending the SAG Awards, for which he was nominated for his performance in the TV show The Five People You Meet in Heaven. Even poor black-listed45 Professor Irwin Corey was fined by the Screen Actor’s Guild for acting in our non-union 1983 production of Stuck on You. As Trent Haaga said earlier, because I produce movies that call for very large casts, my films could never be made using SAG actors under a SAG contract. Our budget would quadruple!

44Jon Voight is an American Oscar, Emmy, and BAFTA (British American Film and Television Alliance)–winning actor perhaps best known for his roles in Midnight Cowboy (1969), Deliverance (1972) and Coming Home (1978). He is also Angelina Jolie’s father and thereby grandfather to hundreds of orphans worldwide.

Also, if we were to produce a union movie, SAG would get a gross percentage of the movie profits before anyone else involved in the film got any money whatsoever—not the people who wrote it, the people who directed and acted in it, or the people who invested money in it. SAG bureaucrats, the people who do the absolute least to create the engine of jobs a movie production creates and utilized zero artistic ingenuity—they get their money first. In other words, everyone who had absolutely nothing to do with the reason the movie exists in the first place gets a huge chunk off the top before anybody else. This is fundamentally wrong. The 92 percent of actors who never work may or may not agree with me.

Who is Buddy Giovinazzo?

Buddy Giovinazzo is a director/writer who began his career with Troma’s Combat Shock. His most recent feature, Life Is Hot in Cracktown (based on a book he wrote of the same name), stars Kerry Washington, Lara Flynn Boyle, Illeana Douglas and Shannyn Sossamon.

AL: On an A-list film, we’ll do a movie for anywhere from 40 million to 50 million dollars. It’s all about the budget—you take as much money as you can based on how much you think you can sell. We do use the Screen Actors Guild, but I think one of the major problems with America and the economy are the unions—the unions are the reason why America is incapable of producing anything on the level of other countries—because of the way the unions treat their members and the companies that hire their members.

For example, if someone in our business is making $2.5K a week, which is a great salary for anyone in the world, then the union will take 30 percent of that. They take 30 percent of the cost and use it for whatever reason they want. When you have five or six different unions, everyone takes his own share.

BG: Our budget for Life is Hot in Cracktown was $1 million dollars. We had a SAG cast, but a non-union crew. When you’re a small film, like ours was, the unions will sometimes come and try to shut down your production. A union representative will approach the cameraman and say, “Hey, do you want to be a member of our union?” and that question is a crew member’s dream. All crew people want to work on union films, because that’s where the money is. The union rep will offer him direct union membership and shut down the rest of the production.

A lot of times, someone on the crew who wants to be in the union will call the union and complain that we aren’t paying them overtime, and the union will come down and shut you down. We were lucky no one did that on our film, but if I were a bastard director, it would happen. If no one complains, and there’s no money to be had, they don’t shut you down.

AL: The most ridiculous union in the world is the teamster’s union. Every 17-year-old has a driver’s license and yet they need the union to protect them. Like you need a special education to drive a truck. A lawyer will study three years at a university; a doctor will study seven years at school and in residency in order to be a good doctor. A driver needs maybe one or two weeks to learn how to drive and yet a driver on a union movie in New York will cost you $6K, $4K a week, and then the unions will take $2K. This is outrageous. You have to take a certain number of them and you have to have teamster captains—production coordination and a driver coordination. The way that America is forced to use unions … it’s helping un-America. And that’s the reason America is bankrupt.

My Perfect Night In

My taxi had pulled up outside the door of my domicile with the “I Love Tromaville” sticker peeping through the front-door window. This book was getting more and more depressing with each passing day. At least now, within the confines of my own home, 46 I could wallow in my stellar standards of sexual depravity coupled with my superior code of moviemaking ethics and watch our country stone itself in each documented nanosecond on CNN.

46INDEX GYNO: Lloyd, baby, you sound awfully lonely. Do you need a massage?**FOOTNOTE GUY: I do! I need a massage! You have no idea how much your muscles hurt when you’re this small and constantly jumping up and down in the margins of book-land just to get noticed.

Stoning Victims Trey Parker and Matt Stone

Who are Trey Parker and Matt Stone?

Trey Parker and Matt Stone first came to Troma with their brilliant musical movie masterpiece, Cannibal the Musical, which has never once been seen on U.S.television, thanks to the MPAA and those mega-conglomerates, but has been distributed by Troma and has sold an estimated zillion videotapes and DVDs. Parker and Stone later went on to create South Park (that show you may have seen on television in the middle of the night sandwiched between “Slanket” and “Life Alert” infomercials) and, most recently, the movie Team America. They are now working on a new movie—some kind of Godzilla satire, I believe.

Trey Parker: Making a movie is just brutal. We forget that. Trying to remember back to those days where you were making a movie just because it’s was fun—I can’t imagine why we would have done that! We started making Team America and we got totally screwed in our deal. At one point, Paramount said “We’re not making the movie unless you guys do it for free.” So we’re not making any money on this movie. We’re basically making an independent film again, only this time it’s with studio money. But then when you’re here at two in the morning pulling your hair out because you can’t figure out how this scene’s going to go with that scene and you’ve been over it a million times and you’re just like “Why are we doing this? We hate it. We hate making movies.” There’s a time where you really love it and that’s right before shooting. You get this idea and you think “I think we’re going to be able to do this, we’ll put on a show and it’ll be great!” and then the production goes on and on and you get kicked in the balls over and over and you compromise.

Matt Stone: It’s all just a series of compromises from day to day and week to week. You have something in your mind—”OK, this is what the movie should be,” and then every day it’s just, “Well, we can’t do that … there can’t be five Korean soldiers, can we have three?” We can have two. Okay, two. “Well, their faces don’t move for this puppet movie.” OK. “Well, we want to shoot a car chase throughout LA.” Well, we’ve got only one car … . It’s every time you shoot a movie. You just compromise from the day you’ve got the idea until the day it’s in the can.

This Is Fucking Depressing … Anybody Else Want to Stop Reading and Go Out for a Beer?

So you see, part of this business is just about surviving the stoning that comes from everyone from wannabe investors to ratings boards, to the peons who make up the rules about who goes up on stage to accept an Oscar, to having your production shut down by a truck driver. No need to inflict this stoning upon yourself Begelman-style, because it’s going to come at you, no matter how small or big you are, no matter whether you’re a beginner or veteran. Producing a movie is the ultimate lottery ticket—actually, it’s more like the “Mystery” scratch-and-play kind—and speaking of scratch-and-play, I think I’m going to do just that at this very moment, since I’m now at home and no one else is around.