CHAPTER 1

The Low-Cost Carrier Business Model

Definition

Various definitions for low-cost carriers (LCCs) exist today (Dietlin 2004; Kumar 2005; Doganis 2006; Hunter 2006; Holloway 2008). Although marginally different, most researchers define LCCs as carriers which, through a variety of operational processes, have achieved a cost advantage over full-service carriers (FSCs). However, these definitions often do not capture the effect of transferring cost advantages to consumers in the form of lower fares. It is therefore important to stress that in the context of this book, a low-cost carrier will be defined as a carrier which translates these cost savings into lower, more affordable fares for the travelling public. This chapter examines some of the main characteristics of LCCs in terms of service offering, network structure, marketing, and fleet and labor utilization, which have enabled them to achieve this cost advantage and consequently offer lower fares to customers.

Key Elements of the LCC Business Model

Service Offering

The key focus of the LCC business model is on the “atomization” of the product into the greatest possible number of discrete elements. LCCs are concentrated only on the most basic transportation function, which forms the core product. Other elements of the product are either not offered at all, or are offered separately, incurring additional charges for the customer. This results in cost reductions and/or creates opportunities for additional, so-called ancillary revenues for LCCs. The three most common “frills” removed from the LCC service offering are complimentary food and beverages, assigned seating, and free baggage allowances.

On most LCCs, food and beverages are very limited and often come at an additional charge. This not only decreases the cost and complexity of catering, but also reduces the need for the required facilities and extended galley space in the aircraft. Assigned seating is a similar “luxury” that very few LCCs offer. Following the model of Southwest Airlines, European-based carriers such as Ryanair have no preseating arrangements and operate on a first-come, first-served basis. Due to the importance attached to priority seating by customers, however, some airlines such as easyJet have started issuing “speedy boarding” tickets that can be purchased in advance. Other LCCs, such as Asian LCCs AirAsia and SpiceJet, have also introduced online advance seat purchase for customers wanting to choose their seats beforehand, while all other passengers are assigned seats at check-in. A further element of the business model concerns checked-in baggage. The majority of LCCs today charge passengers per piece of checked-in luggage, and some even apply strict rules on permissible luggage weights per passenger (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008).

This pay-per-service approach is, to varying degrees, applied by most LCCs. There is, however, a broad spectrum between the minimalist approach, such as that offered by Ryanair, and other LCCs such as WestJet, where some or all of these services are complimentary. Furthermore, these operating practices are no longer unique to the LCC business model. Particularly in the North American market, network carriers have also started introducing these cost-saving measures. United Airlines and Air Canada, for example, have been charging customers for food on domestic flights and have introduced fees for the check-in of bags.

Network Structure and Scheduling

Point-To-Point versus Hub-and-Spoke Structures

The route structure that traditional airlines have adopted is a so-called “hub-and-spoke” system. “Spoke” flights concentrate the passengers in one or more “hub” airports and passengers transfer to an onward flight to either their final destination or, usually for transcontinental city pairs, to a further “hub” where they transfer to “spoke” flights to their final destination (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008).

This is a very costly operation, as the often-expensive infrastructure at hubs such as runways, gates, and ground equipment has to be geared to short, very strong surges in traffic, which allow the rapid transfer of passengers between flights. The downtimes between these surges, however, lead to a low average utilization of the facilities. Furthermore, diseconomies of scale can arise because in peak times hubs have to deal with added congestion on the ground as well as in the air leading to delays and higher fuel and labor costs (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008).

For many network airlines, particularly ones of considerable size with strong market presence or based at a strategic location, such as Emirates or Lufthansa, this model has been effective, as it enables many city pair choices and certain economies of scale. Most LCCs, however, try to avoid the complexities and costs of hub-and-spoke networks by operating a point-to-point route structure. Under this structure, the LCC serves a more widely spread route network offering nonstop flights between city pairs. Some LCCs still operate bases, which allow for economies of scale, but in contrast to traditional carriers, there are fewer peaks or downtimes. This allows for the continuous and improved utilization of facilities and employee services, thereby reducing costs.

Although most LCCs only offer point-to-point services, many still have so-called “focus cities,” which serve a large network of destinations, even though there is no attempt to consolidate or connect passengers. There are also exceptions such as Jazeera Airways (Kuwait) that actually connects passengers through Kuwait International Airport hub, or Go-Air (India) that offers connections through its hub in Mumbai, India.

Due to the costs associated with traffic surges at hubs, efforts have also been made by network carriers to reduce peaks at hubs. Delta and Lufthansa, for example, have been spreading flights more evenly across the day at their hubs in Atlanta, Cincinnati, and Salt Lake City (Hirschmann 2004), and Frankfurt, respectively (Mederer and others 2008).

Usage of Secondary Airports

A commonly applied operating practice for LCCs is the usage of secondary or regional airports.1 These airports generally have three main advantages in comparison to primary airports: lower airport charges, the availability of slots,2 and reduced congestion.

In contrast to primary airports, secondary airports often offer lower airport charges to airlines. Due to their limited service offering in terms of airport infrastructure and, in the case of remote airports, lower input costs (for example, lower land rents), secondary airports often benefit from lower operating costs and increased efficiency (Forsyth 2003). In addition, due to the benefits that low-cost operations can bring to an airport and its surrounding area, some LCCs have been able to obtain favorable arrangements with local governments for the usage of secondary airports. In Rimini, Italy, for example, the respective airport authority subsidized Ryanair to start operations from their airport in 1998 (Calder 2002). However, when the airport’s management changed a couple of years later, the arrangement had to be renegotiated and Ryanair cancelled its flights to Rimini. This is a good example of the bargaining power the airline had achieved.

Secondary airports have another advantage in that they often do not suffer from the type of congestion experienced at major airports, and consequently offer the required capacity for LCC development. With ever-rising air traffic, primary airports such as New York’s La Guardia, London’s Heathrow, and Amsterdam’s Schiphol have experienced substantial challenges with regard to congestion and lack of capacity. Between June 2012 and 2013, for example, La Guardia Airport experienced over 12 percent in delays by airlines resulting from “national aviation system delays,” which include nonextreme weather conditions, airport operations, heavy traffic volume, and air traffic control issues (RITA BTS 2013).

By contrast, most secondary airports across Europe and the United States were previously significantly underutilized. These secondary airports were historically built to serve low-frequency regional flights for travel onward from hubs to smaller- or medium-size towns. For example, Orio al Serio Airport in Italy was initially only meant to create a link between Rome and Bergamo. Until the arrival of low-cost airlines, the airport had not served any international routes. Other local airports used to have a military function but were abandoned over time. These have only now been recommissioned for civilian use with the entry of LCCs.

Despite only serving few destinations at a low frequency, many of these secondary or regional airports were of considerable size. Glasgow’s Prestwick, for example, used approximately 1 percent of its capacity, and Belgium’s Charleroi Airport received around 20,000 passengers per year (54 per day) before low-cost airline Ryanair entered the market (European Commission 2004).

Operating from these high capacity secondary airports has enabled LCCs to design the most efficient schedules to make the best use of their fleets and to avoid congestion (Barbot 2004). A study by Warnock-Smith and Potter (2005) showed that avoiding congestion often results in aircraft productivity gains of more than 50 percent for LCCs in comparison to network carriers.

LCCs in Europe and the United States have built up dense networks around secondary airports. Southwest Airlines, for example, serves secondary airports such as Manchester Boston Regional or Long Island Airport. The European LCC Ryanair uses almost exclusively minor airports to serve larger agglomerations. For example, Ryanair uses Hahn Airport located some 100 kilometers outside Frankfurt or Weeze Airports instead of Düsseldorf Airport (Ryanair 2013). However, with the extensive expansion of LCCs, there has been a shift in both carriers’ networks to sometimes include a few select primary airports. Southwest now offers a high number of daily departures from Los Angeles International Airport (Southwest Airlines 2013), and Ryanair operates flights to Dublin, Gatwick, Birmingham, and Manchester (Ryanair 2013). In order to retain their cost advantage and reduce high charges at these airports, LCCs using primary airports often choose to avoid the rental of expensive ground facilities (for example, jetways) and use older facilities at the airport (De Neufville 2005).

A few LCCs also focus almost entirely on primary airports. Ryanair’s rival easyJet, for example, has been serving primary airports such as Amsterdam’s Schiphol, Paris’s Charles De Gaulle, and Barcelona–El Prat. It also operates easyJet Switzerland, its subsidiary, from its base at Geneva International Airport. AirBerlin and the Spanish Airline Vueling follow a similar strategy. Alternatively, some U.S. LCCs, such as AirTran and JetBlue, base their operations at a prime international hub and serve secondary airports from this base.

In recent years, some primary airports have also been adjusting their offerings to attract LCCs and their high passenger volumes. Hong Kong International Airport, which serves a number of LCCs including AirAsia, Cebu Pacific (the Philippines), Oriental Thai (Thailand) and Jetstar Asia, caters to LCCs by offering them cheaper and better-arranged gates, and simplified procedures that reduce aircraft turnaround time. Some primary airports have even invested in so-called “low-cost terminals,” specifically designed to suit the LCC business model omitting travelators, escalators, and aerobridges. Other primary airports also discount their aeronautical charges and reduce passenger facility service charges (Bentley 2009). Some good examples of LCC terminals (LCCTs) are Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA), Zhengzhou Xinzheng International Airport (ZHCC) in China, and the budget terminal (BT) at Singapore’s Changi International Airport (SCIA). The sustainability of this alternative to secondary airports remains to be seen (Zhang and others 2008).

High Aircraft Utilization

An important factor in the success of LCCs is the high daily level of utilization of their most capital-intensive asset, their aircraft. As research shows, there is a strong negative relationship between operating unit costs and aircraft utilization (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008). Higher daily aircraft utilization is primarily achieved through shorter turnaround times, longer routes, or higher flight frequency (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008).

Most low-cost airlines try to increase the daily utilization of their aircraft by minimizing turnaround time. This is achieved by abolishing seat allocation and consequently shortening boarding procedures, limiting or removing catering, and using less congested and more efficient secondary airports. Ryanair, for example, recorded an average scheduled turnaround time of approximately 25 minutes (CAPA 2013b). Southwest’s turnaround time ranges between 10 and 25 minutes (Schlesinger 2011).

Some LCCs also increase their aircraft utilization by flying longer routes.3 For example, JetBlue operations have an average stage length of 1,088 miles.4 This is due to the fact that JetBlue operates a number of transcontinental flights, for example, between Los Angeles and Boston or between Long Beach and New York. Similarly, easyJet in Europe has extended its traditionally short-haul network to include medium-haul routes such as Geneva to Tel Aviv or Sharm-el-Sheikh to Manchester.

Some LCCs also increase their utilization by simply increasing the number of flights per day. By commencing their first flights very early in the morning, LCCs manage to operate a significant number of flights by utilizing their aircraft between 10 and 14 hours daily. Ryanair, for example, operates its first flight from London’s Stansted Airport to Stockholm at 6:05 a.m. However, higher flight frequency has, in itself, not been proved to be a key success factor for LCCs (Dietlin 2004).

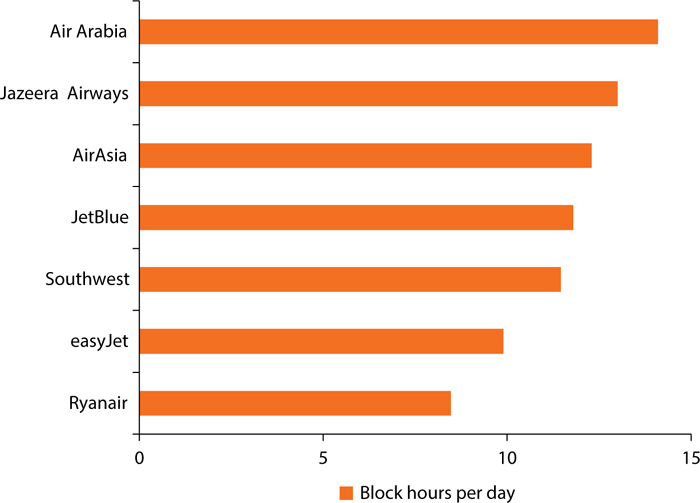

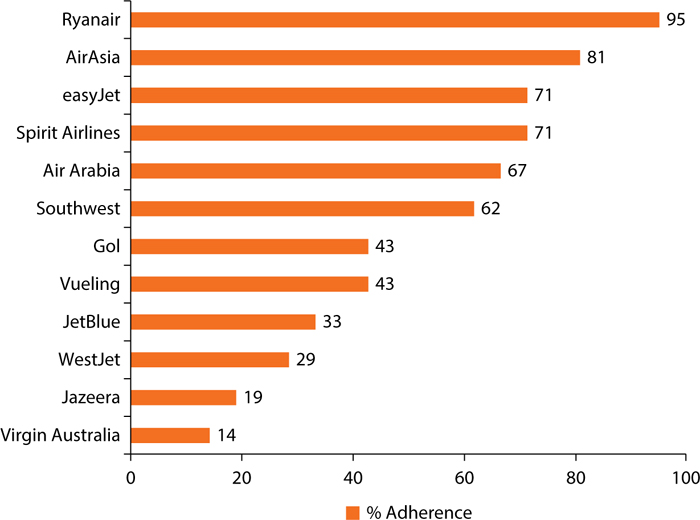

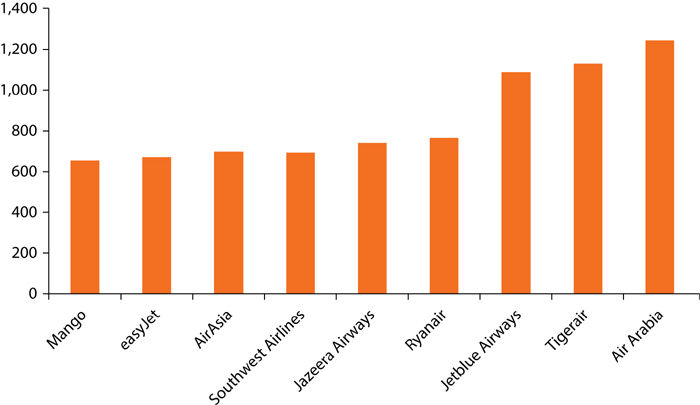

Figure 1.1 provides a comparison of average daily block hours per aircraft of a number of LCCs, showing that most LCCs operate long hours each day. Interestingly, Ryanair appears to tend more toward the lower end of the spectrum. According to aviation data provided by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Airline Data Project (MIT 2013) analyzing a sample of U.S. network carriers and LCCs, LCCs operate on average around an hour longer each day.

Figure 1.1 Average Daily Aircraft Utilization by LCCs, 2011–12

Sources: Based on information from airlines’ annual reports and presentations, SEC filings, Air Finance Journal, and Seat Guru. (See appendix B.)

Note: Fiscal year may not be in line with calendar year for each airline and may vary in some cases. LCC = low-cost carrier.

Shorter Stage Lengths

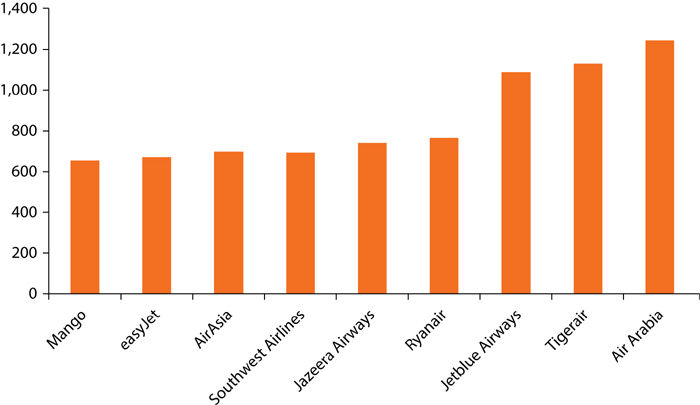

Low-cost airlines operate in networks consisting predominantly of short-to-medium haul routes of fewer than 1,500 miles and/or fewer than six hours of flight time (see figure 1.2).5 This contradicts traditional airline economics, where per mile costs for the same aircraft type are generally higher on shorter rather than on longer flights. Indeed, shorter routes traditionally result in higher costs due to more labor-intensive time spent on the ground due to multiple landings as well as fuel costs (particularly from the fuel-intensive ascent phase), which have to be spread over a shorter revenue generating distance in the air. Furthermore, landing fees and passenger processing costs are fixed, regardless of distance traveled (Dietlin 2004). This cost difference is particularly dramatic when extending a flight from short to medium haul, but becomes more linear with very long stage lengths.

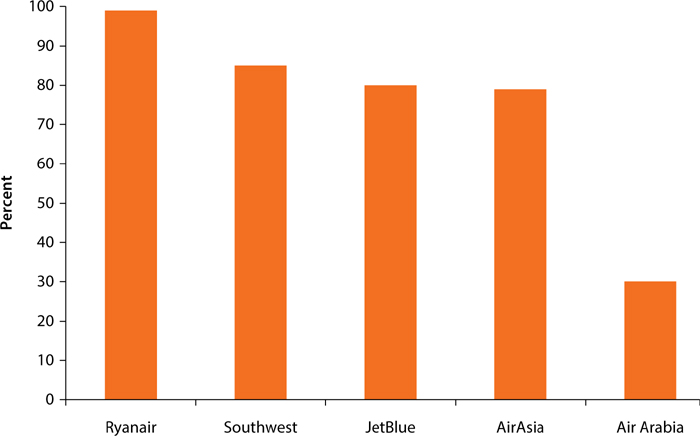

Figure 1.2 LCC Average Stage Length, 2013

miles

Source: Based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: LCC = low-cost carrier.

Short-haul routes, although costlier, generally translate into higher unit revenues, however, due to the effects of scalability and market demand. Combined with LCCs’ overall lower input costs and/or higher productivity this can be a significant competitive advantage over network carriers on short-haul routes. These relative cost advantages that LCCs have over network carriers on short flights resulting from lower distribution or ground handling costs would, however, diminish with increased stage length, as its percentage of the total cost shrinks (Dietlin 2004).

Local demand for long-haul flights may also not generate sufficient traffic to sustain a point-to-point network structure. Furthermore, the low-cost airlines’ purist “no frills” concept would have to potentially be adapted to include in-flight services, which would in turn increase turnaround times and decrease utilization hours. This being said, there have been some low-cost, long-haul airlines that have emerged recently but with varying degrees of success. AirAsia X is one of the few profitable ventures, which has adapted the original low-cost structure by introducing some elements of a network carrier in order to attract sufficient passenger volumes.

Fleet

Fleet Standard and Commonality

Another success ingredient of the LCC model is the use of a single aircraft type fleet. Fleet commonality can decrease costs considerably as it reduces the amount of ground support equipment, training, and spare parts inventories, and allows for standardized handling and maintenance processes as well as flexible crew scheduling. Furthermore, bulk purchases allow discounts from suppliers and economies of scale, as the LCC only has to invest once in fixed fleet costs (for example, specialized equipment) (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008).

On the downside, fleet commonality can reduce flexibility to respond to market changes. Capacity changes are therefore only possible by adding or canceling flights. Moreover, dependency on one aircraft manufacturer may be restrictive.

The most typically used aircraft by LCCs are the Boeing 737 (B737) and the Airbus 320 (A320). Both airliners can accommodate anywhere from 110 passengers in low-density configurations to 220 passengers in high-density, single-class layout, and provide great range flexibility. Boeing’s 737–800 has a range of up to 5,765 kilometers (3,113 nautical miles) (Boeing 2013). The A320 (with sharklets6) can even achieve up to 6,150 kilometers (3320 nautical miles) (Airbus 2013). Although it is difficult to compare unit costs across different aircraft as the cost depends largely upon the direct operating costs (DOC) of an airline, fuel efficiency and maintenance costs can be used as good indicators for LCCs in choosing these types of aircraft. Both models, particularly the newer 737–800 and the A321, perform well with regard to these criteria. Due to the late entrance of LCCs into the aviation industry, they were often able to invest in these newer aircraft types while traditional carriers were still operating with older models. The A320, for example, consumes between 11 and 25 percent less fuel per seat than Airbus’s legacy aircraft, such as the Airbus 300 or 310 (World Bank 2011). Fuel costs are a crucial factor in both LCCs and network carriers, representing between 35 and 40 percent of operating costs (Boeing 2013).

The majority of LCCs have a single-type aircraft fleet, but there are some exceptions with SpiceJet and JetBlue having established a “two-type” model, with a fleet of slightly smaller aircraft such as the Bombardier Q400 and Embraer E-190 used for shorter distances.

Aircraft Configuration

A further element of the low-cost business model is a high-density, all-economy configuration. Narrow seat pitches of 28–29 inches are common in LCCs, compared to 31–33 inches in traditional airlines (Doganis 2006). Not all LCCs strictly adhere to this principle however, with LCCs such as Virgin Blue (now Virgin Australia), Southwest, and WestJet having seat pitches between 31 and 34 inches. Similarly, not all LCCs have a one-class policy, with Jazeera Airways and Vueling, for example, offering a business or economy premium class.

Marketing

Pricing

Traditionally airlines offer a range of fares in order to attract different customer demand segments in the market. Each of these demand segments are assumed to have differing time and price sensitivity, as well as what is called “willingness to pay.”

This differentiated fare structure is justified to customers by offering varying levels of service amenities and fare restrictions. Service amenities may include bigger seat pitches and premium meals, distinctive separation of economy from business or first class, whereas fare product restrictions would relate to nonrefundability, cancellation fees, or minimum stays. The purpose of these restrictions is to make lower fares less attractive while still offering a viable option for more price-sensitive customers. The highest unrestricted economy class ticket, the so-called Y Fare, is in some cases almost five times that of the lowest discount fare with restrictions.

The entrance of low-cost airlines with a more homogenous product offering, accompanied by reduced corporate spending and the increased transparency of fares through the Internet, led to a shift in pricing strategy toward “fare simplification.” This involved fewer fare levels, fewer restrictions, and a convergence of the highest and lowest fares offered. Restrictions for tickets on LCCs are in some cases just focused on time of booking, with fares tending to increase closer to the departure date.7 In some cases, multiple fares are even filed with the same identical restrictions. Traditionally, airlines segment passenger demand by creating so-called “fences” with independent unique products by fare class. This has allowed them to forecast demand by fare class and then determine the right allocation against capacity. In the LCC fare simplification model, these fences do not exist and have allowed carriers to promote 100 percent “sell down” to the open fare class (Aircraft Commerce 2006). The benefits of fare simplification overall are still debated, as some network carriers such as Delta and American Airlines have failed in their attempts to simplify their fare structures.

Distribution

Since the early days of the Internet, airlines have implemented electronic, that is paperless, ticketing and have used their websites in order to provide reservation and ticketing capabilities. This development highlighted a break from the traditional and costly travel-agent system that was based on the payment of commissions. In the 1990s, commission payments cost airlines up to 13 percent of their passenger revenue (Belobaba, Odoni, and Barnhart 2009). Looking for a lower cost, competitive edge, low-cost airlines were at the forefront of introducing direct distribution channels through their websites and call centers. Southwest Airlines was the first major airline to develop a website and offer online booking (Southwest Airlines 2012). Cost per booking via an airline’s own system is estimated at around US$1, whereas the cost per booking via a global distribution system (GDS) is between US$5 and US$12 (Perkins 2012).

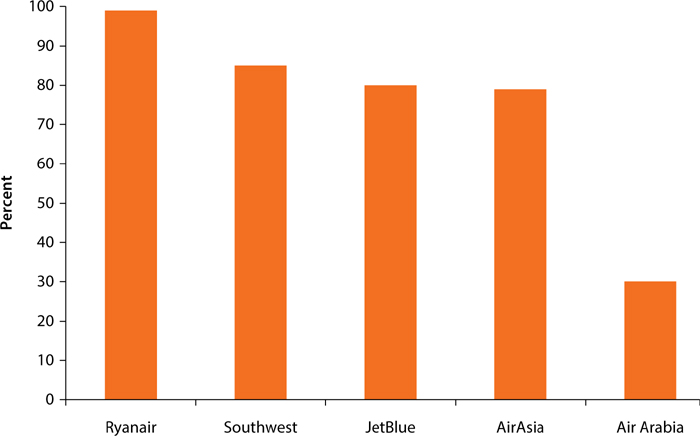

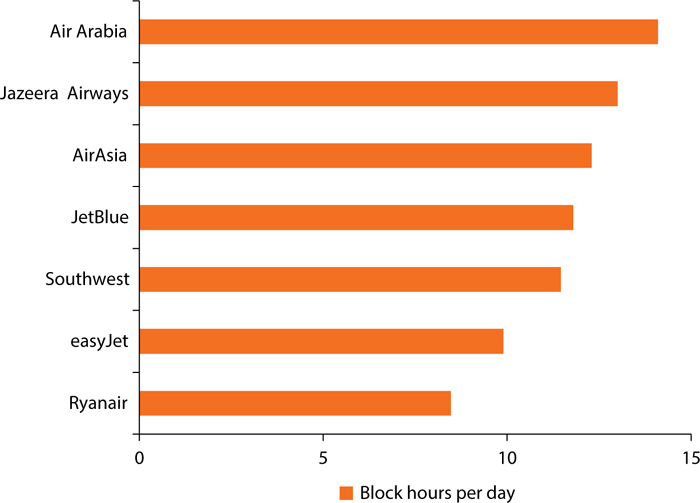

Figure 1.3 shows that the percentage of online distribution of a sample of LCCs is generally between 75 and 99 percent, thereby reducing their costs significantly. However, the success of this strategy is highly dependent on the degree of Internet penetration in a particular region. Middle Eastern LCCs, such as Air Arabia or Jazeera Airways have much lower online distribution (around 30 percent), as overall Internet penetration is much lower (around 35 percent of population in comparison to around 60 percent in Europe). In some countries such as Saudi Arabia, Internet connections only arrived in 1999, and have experienced a slow process of adoption since then (Alterman 2000).

Figure 1.3 Online Distribution as Percentage of Total Distribution, 2011–12

Sources: Based on information from airlines’ annual reports and presentations, SEC filings, Air Finance Journal, and Seat Guru. (See appendix B.)

Note: Fiscal year may not be in line with calendar year for each airline and vary in some cases.

Some carriers, such as Ryanair, also follow the successful strategy of aligning themselves with a GDS provider in the beginning, but then ending their agreements, as their brands grow stronger. The advantage of this approach is that carriers initially have a wide distribution network and then narrow their distribution channels when shifting ticket sales toward their website (Field and Pilling 2005). Although initially providing a substantial competitive advantage for LCCs, high levels of online booking have become common today.

Labor

Labor represents a considerable expense in an airline’s cost structure. In order to reduce this cost, LCCs are focused on increasing labor productivity by increasing airline “output” (available seat kilometers [ASK] or available seat miles [ASM] per employee).8 This is generally achieved by a higher number of average block hours per employee and a higher passenger per employee ratio. Research by the MIT Airline Data Project in 2012 shows that in the United States, average block hours per pilot for LCCs were around 12 hours longer per month than for U.S. network carriers. An even larger difference is seen for flight attendants. Similarly, the number of passengers per flight attendant was more than double in its last estimate in 2012 (MIT 2013).

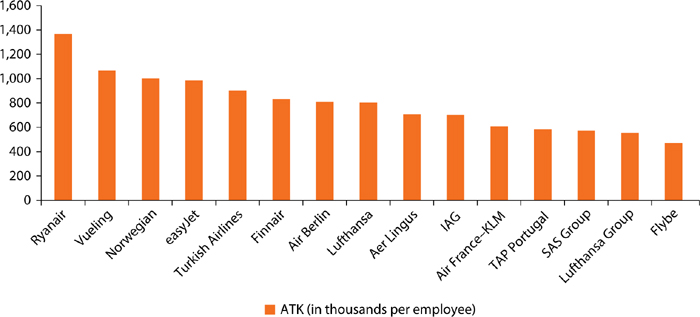

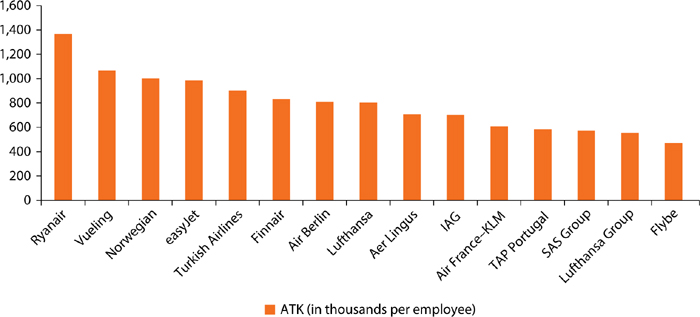

A more recent comparison of labor productivity in Europe by the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (see figure 1.4) shows that LCCs, particularly Ryanair, Vueling, Norwegian, and easyJet, have significantly higher ASK ratios per employee than network carriers, such as Air France or Lufthansa (CAPA 2013a).

Figure 1.4 Labor Productivity Comparison, 2011–12

Source: Based on data from the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (CAPA 2013).

Note: The measure Available Ton Kilometers (ATK) is used here to compensate for cargo-carrying carriers.

In some research, it has been argued that low-cost carriers also pay significantly lower salaries. Harvey (2007), for example, highlights that, on average, pilot salaries at LCCs are 27 percent less than at their full-service airline colleagues. Some also believe that this is due to the lack of unionization in some LCCs, such as Ryanair, thereby allowing for longer hours and lower pay scales. There does not seem to be consensus with regard to this view however. Southwest, for example, a successful LCC with strong unionization, appears to prove the opposite.

Different Types of LCC Models

A significant number of airlines are categorized as LCCs today. This definition, however, is, according to Chris Tarry from the airline magazine Airline Business, “the most over-used term in our industry” (Tarry 2010). As this research demonstrates—and has been established through previous research conducted by Oliviera (2008), Francis and others (2006), Graham and Vowles (2006), and others—even though some common operating practices can be identified across low-cost airlines, there is no one LCC model, nor is there a single driving element responsible for its competitive advantage. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between different subtypes of LCC models, as their scope for success and their impact on an aviation market may vary accordingly.

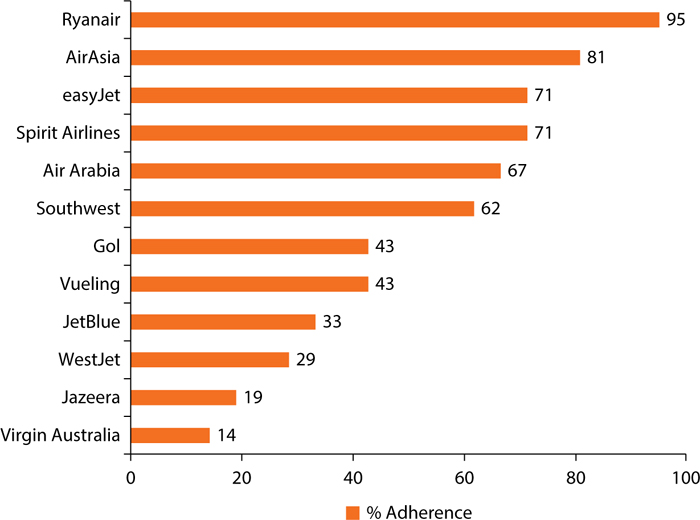

For this purpose, a small sample of LCC carriers was analyzed with regard to their adherence to the most common building blocks, as outlined above.9 These include low unit cost per ASK;10 presence of “frills” (baggage, food and beverages, assigned seating); use of secondary airports; point-to-point structure; high percentage of Internet-based sales; high daily aircraft utilization; homogenous fleet composition; presence of a one-class seating system; and high seating density. Based on previous work by Alamdari and Fagan (2005) and Weisskopf (2010), the authors use a point system to evaluate the extent to which each carrier applied the measures outlined above. (The data collected for each carrier and the point allocation can be found in appendixes A and B).11

As figure 1.5 shows, the level of “adherence” varies significantly, with supposed LCCs such as Virgin Australia operating with a similar business model as network carriers. This is in contrast to more purist LCCs, such as Ryanair and easyJet.

Figure 1.5 Adherence to Low-Cost Model, 2011–12

Sources: Based on information from Weisskopf 2010, airlines’ annual reports and presentations, SEC filings, Air Finance Journal, and Seat Guru. (See appendixes A and B for details.)

Although the level of variability is still significant, in literature (Francis and others 2006; Graham and Vowles 2006; Oliveira 2008) LCCs are often clustered into different groups. For the purpose of this book, LCCs have been assigned to three groups, which are described below.

1. The Purist model: The Ryanair model is found to be the most “pure” LCC business model in the market. Based on the original Southwest Airlines model, the airline has perfected its lowest cost structure through a single fleet type; elimination of free in-flight services; high use of secondary airports; direct sales; e-ticketing; short-haul, point-to-point flights in dense markets with no interlining or transfer;12 a simple network structure; absent or weak feed to long-range flights; single cabin layout; no frequent flyer program; and an optimal level of fleet utilization. With some modifications, easyJet, Spirit Airlines, AirAsia, VivaAerobus (Mexico) and Peach Aviation (Japan) can be seen as applying this model.

2. The Southwest model: Although the Ryanair model was based on the original Southwest model, Southwest Airlines’ cost structure is, in reality, not as tightly managed as that of Ryanair. The airline offers complimentary refreshments aboard, does not charge for baggage, offers wider seat pitches, and actively promotes and sells connecting flights. Therefore, this model has more potential to attract other segments besides leisure travelers. Varying types of spin-offs from the purist concept, as has been applied by Southwest Airlines, can also be seen with Air Arabia, Vueling, Nokair, Spicejet, and Gol.

3. The JetBlue model: This model is making significant moves away from the purist concept, with many frills offered, diversified fleets, and networks composed mostly of primary airports. The model’s focus is on the low-fare business market by making use of multiservice operations with mini-hubs to provide convenient connections and more possibilities in terms of origin/destination (O/D) markets, as well as more complex fare structures including business or economy plus class. To varying extents, this model is used by Virgin Australia, Jazeera, Westjet, and Jetstar.

Although some research such as Alamdari and Fagan (2005) has shown that there is a moderate positive correlation between “adherence” and profitability, there does not seem to be one success strategy in the industry today and market conditions and even cultural factors play a significant role in how LCCs choose or are able to structure themselves.

It should also be noted that LCCs have not been static in their operating practices. As in every industry, LCCs have been adjusting to market conditions and competitive pressures over time, developing and refining their business models to best suit their market. Particularly in more mature markets, the continuing strength of network alliances across the globe has had a significant impact on the “hybridization” of existing and newer generation LCCs.

Are Low-Cost Carriers Really Low Cost?

All of the elements elaborated above comprise the essential difference between network carriers and LCCs—that is, the difference in cost. However, how much of a cost advantage do today’s LCCs really have?

The most widely quoted metric to assess an airline’s cost is cost per available seat miles (CASM; or cost per available seat kilometers [CASK]). CASM calculates the cost of operating one available seat per mile/kilometer. This metric can be used to compare a variety of costs, ranging from fuel to labor. Total CASM or CASK normally includes all DOC such as fuel, labor, maintenance, and other direct expenses (landing fees, capital equipment charges, and so on), as well as indirect or nonoperating costs (IOC), including station and ground expenses, passenger services, ticketing, sales, promotion, and general administration costs. IOC are fixed costs, whereas DOC are variable depending on the number of flights, stage lengths, type of aircraft used, and other factors (Vasigh, Fleming, and Tacker 2008). Although CASM is a valuable indicator when analyzing airlines, it can prove difficult to compare unit costs on a global level due to large differences in basic costs across regions. A network carrier in Asia may operate at a similar unit cost to a low-cost airline in Europe, making a comparison solely based on unit cost futile. This has to be taken into consideration when comparing LCCs and network carriers across regions.

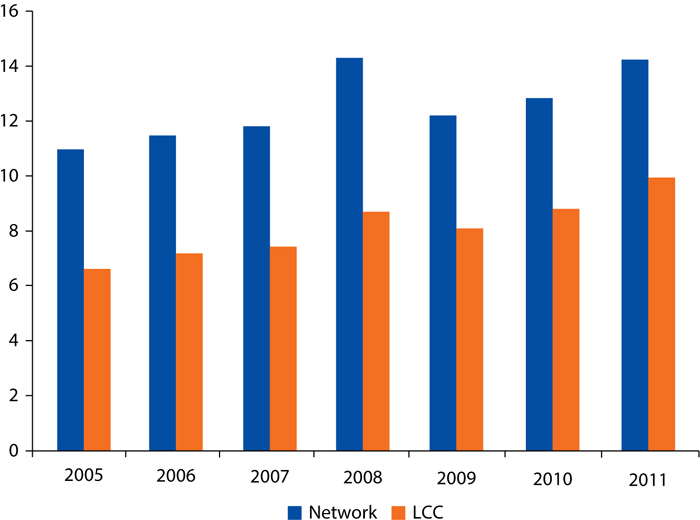

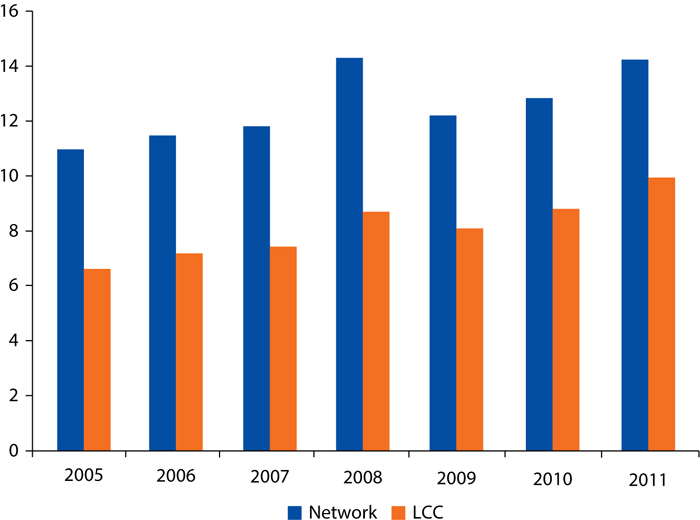

Figure 1.6 shows a comparison of CASM of U.S. network carriers and LCCs between the years 2005 and 2011. As highlighted in the graph, LCCs have been operating with considerably lower unit costs in the past, with costs up to 40 percent lower than network carriers.

Figure 1.6 Comparison of U.S. CASM, Network Carriers, and LCCs, 2005–11

U.S. cents

Source: Based on data from MIT Airline Data Project (MIT 2013).

Note: CASM = cost per available seat miles; LCC = low-cost carrier.

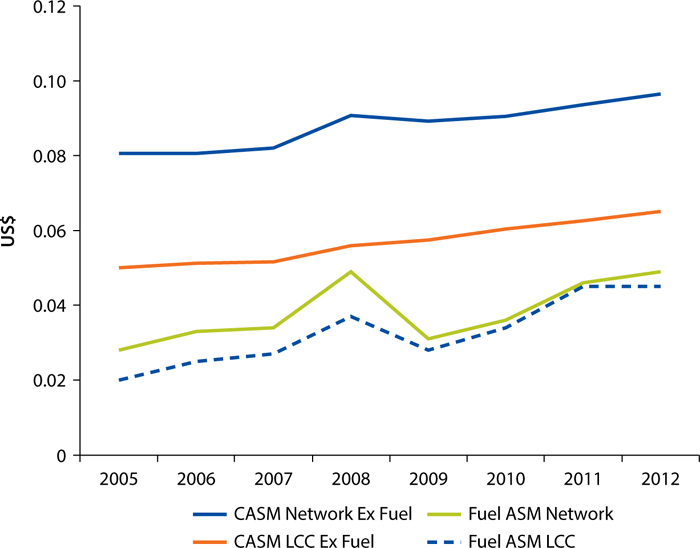

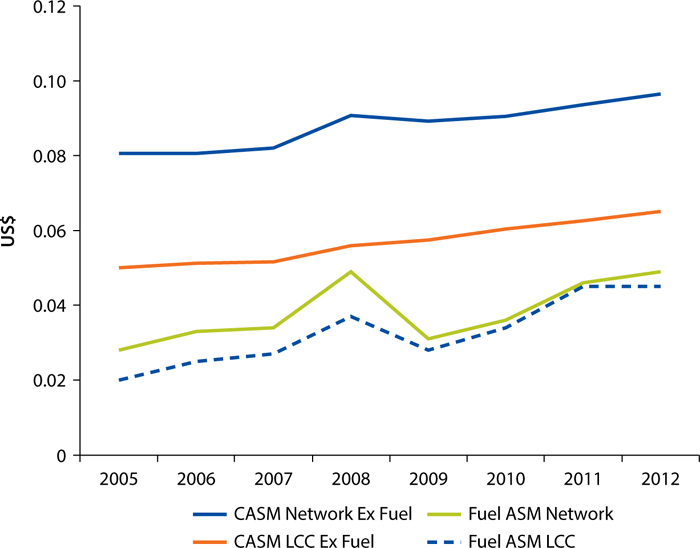

Figure 1.6 also demonstrates that this cost difference has been shrinking since 2005. In 2011, LCC unit costs were around 30 percent lower than those of network carriers, which have adapted their operating practices by introducing cost-reduction measures (for example, baggage and food charges and reducing distribution through travel agents). However, one of the main reasons for this cost convergence lies in the shrinking gap in fuel expenditures. As figure 1.7 shows, for U.S. carriers, the difference in fuel costs has been almost entirely eradicated. This is primarily related to the fact that as network carriers are modernizing their fleets, their fuel efficiency is reducing their costs. This removes one of the competitive advantages LCCs historically had over network carriers and has led some LCCs to adapt their business models to attract more higher yield passengers.13

Figure 1.7 Comparison of Network and LCC Fuel CASM

Source: Based on data from MIT Airline Data Project (MIT 2013).

Note: ASM = available seat miles; CASM = cost per available seat miles; LCC = low-cost carrier.

In other markets, particularly in Europe, this convergence has not been as strong. This is primarily because of the presence of ultra–low cost airlines such as Ryanair and AirAsia gaining considerable cost advantages in other areas (Hazel, Stalnaker, and Taylor 2012).

Conclusion

There are some common building blocks among LCCs, but there is no one low-cost model. As the analysis showed there are some challenges in defining exactly what constitutes the LCC business model. Although there are a number of elements that are common in most LCCs such as limited service offerings, the use of secondary airports, low distribution costs, and/or high labor utilization, there is a broad range of business models under the LCC umbrella. These models diverge considerably in their offering and operating practices. Industry characteristics and target markets, as well as cultural factors, have had a substantial impact on the respective business models.

Particularly in the United States, but also in Europe, many LCCs have been “hybridizing” their models as more mature LCC competition, higher fuel prices, and powerful network alliances have shifted the focus to higher yield opportunities. As the above analysis shows, there are numerous airlines such as JetBlue or Air Arabia that are operating a much more ‘hybridized’ LCC model. Even airlines such as Southwest have shifted more toward traditional models catering to business traffic by using primary airports and adjusting their schedules.

Low cost may not mean low cost anymore. A convergence in costs has occurred over recent years, as network airlines, under competitive pressures from their new counterparts, are becoming more cost sensitive. Fuel prices have had a considerable impact on this convergence as well, with LCCs losing their advantage of more fuel-efficient aircraft due to the fleet renewal process taking place among most traditional airlines.

Despite these recent developments, the lower fares that LCCs have been able to continually offer due to their cost advantages have significantly shaped the aviation market of today. Chapter 2 identifies some of the impacts that LCCs and the growth of aviation have had on the air transport industry and the economy as a whole.

Notes

1. Secondary airports are defined as airports complementary to a city’s primary airport in a multiairport system (De Neufville 2005).

2. A slot is defined as a permission given by a coordinator to use the full range of airport infrastructure necessary to operate an air service at a coordinated airport on a specific date and time for the purpose of landing or takeoff (http://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/air/airports/slots_en.htm).

3. Longer routes are determined as still within the short-to-medium haul frame, and do not refer to long-haul flights.

4. “Stage length” refers to the distance flown by an aircraft between a city pair.

5. A short/medium flight is usually domestic or regional in nature, typically lasting fewer than six hours in duration (per the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation), or is between 200 and 1,500 miles (per the Economics of European Air Transport).

6. Sharklets are 2.4-meter-tall wingtip devices that provide operators with the flexibility of either adding an additional 100 nautical mile range or increased payload capability of up to 450 kilograms.

7. There has been some research disputing this monotonic relationship identifying that the volatility of fares increases four weeks prior to departure.

8. Available seat kilometers is the measure of a flight’s passenger carrying capacity, calculated by multiplying the number of seats on an aircraft by the distance traveled in kilometers.

9. The sample included Ryanair, easyJet, AirAsia, Southwest, Air Arabia, Vueling, Westjet, Gol, Spirit Airlines, JetBlue, Jazeera, and Virgin Australia.

10. Unit costs were translated into PPP International Dollars to provide a more appropriate comparison across different countries.

11. The maximum number of points per element was set at 2. In some cases, 1 point was awarded when airlines only partially adhered to the pure LCC model, for example, in the use of secondary airports where some airlines have mixed strategies. Although the maximum number of points possible is set at 22, LCCs scoring 21 points are also classified as adhering 100 percent, as some data were unavailable.

12. Interlining is a voluntary commercial agreement between individual airlines to handle passengers traveling on itineraries that require multiple airlines.

13. “Yield” refers to a measure of passenger “unit revenue.” “Higher yield passengers” normally refer to business class or first class passengers.

References

Airbus. 2013. “A320 Performance.” http://www.airbus.com/aircraftfamilies/passengeraircraft/a320family/a320/performance/.

Aircraft Commerce. 2006. “Evolution from Legacy to Modern Revenue Management Systems.” Aircraft Commerce (44): 43. http://airlinerevenuemanagement.com/uploads/ISSUE_44-REVENUES_1_.pdf.

Alamdari, F., and S. Fagan. 2005. “Impact of the Adherence to the Original Low-Cost Model on the Profitability of Low-Cost Airlines.” Transport Reviews 25 (3): 377–92.

Alterman, J. B. 2000. The Middle East’s Information Revolution. Center for Strategic and International Studies. http://csis.org/press/csis-in-the-news/middle-easts-information-revolution.

Barbot, C. 2004. “Low-Cost Carriers, Secondary Airports, and State Aid: An Economic Assessment of the Charleroi Affair.” Centro de Estudos de Economia Industrial, do Trabalho e da Empresa. FEP Working Paper No. 159. http://wps.fep.up.pt/wps/wp159.pdf.

Belobaba, P., A. Odoni, and C. Barnhart. 2009. The Global Airline Industry. West Sussex, U.K.: John Wiley & Sons.

Bentley, D. 2009. Low Cost Airport Terminals Report. Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (CAPA). http://centreforaviation.com/reports.

Boeing. 2013. “737–800 Technical Specifications.” http://www.boeing.com/boeing/commercial/737family/pf/pf_800ERtech.page.

Calder, S. 2002. No Frills: The Truth behind the Low-Cost Revolution in the Skies. London: Virgin Books.

CAPA (Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation). 2013a. “European Airline Labour Productivity: CAPA Rankings.” http://centreforaviation.com/analysis/european-airline-labour-productivity-capa-rankings-104204.

———. 2013b. “Ryanair SWOT Analysis—Michael O’Leary’s Maniacal Focus on Being the Lowest Cost Producer.” http://centreforaviation.com/analysis/ryanair-swot-analysis--michael-olearys-maniacal-focus-on-being-the-lowest-cost-producer-96465.

De Neufville, R. 2005. “Le Devenir Des Aéroports Secondaires: Bases D’un Réseau Parallèle De Transport Aérien?” Les Cahiers Scientifiques du Transport 47: 11–38.

———. 2006. “Accommodating Low-Cost Airlines at Main Airports.” Paper presented at the Transportation Research Board. http://ardent.mit.edu/airports/ASP_papers/Accommodating%20Low%20Cost%20Carriers--%20revised.pdf.

Dietlin, P. 2004. The Potential for Low-Costs in Asia. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

DiiO SRS Analyzer. 2013. DiiO Online Database. http://www.diio.net.

Doganis, R. 2006. The Airline Business. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge.

European Commission. 2004. “Commission Decision of 12 February 2004 concerning Advantages Granted by the Walloon Region and Brussels South Charleroi Airport to the Airline Ryanair in Connection with Its Establishment at Charleroi (notified in Number C(2004) 516).” Official Journal of the European Union.

Field, D., and M. Pilling. 2005. “The Last Legacy.” Airline Business 21 (3): 48–51.

Forsyth, P. 2003. “Airport Competition and the Efficiency of Price Structures at Major Airports.” Paper presented at the German Aviation Society, Research Seminar, Leipzig, Germany, November.

Francis, G., I. Humphreys, S. Ison, and M. Aicken. 2006. “Where Next for Low Cost Airlines? A Spatial and Temporal Comparative Study.” Journal of Transport Geography 14 (2): 83–94.

Graham, B., and T. M. Vowles. 2006. “Carriers within Carriers: A Strategic Response to Low-Cost Airline Competition.” Transport Reviews 26 (1): 105–26.

Harvey, G. 2007. Management in the Airline Industry. London: Routledge.

Hazel, B., T. Stalnaker, and A. Taylor. 2012. “Airline Economic Analysis.” Oliver Wyman. http://www.oliverwyman.com/media/OW_Raymond_James_2012_FINAL.PDF.

Hirschmann, D. 2004. “How Hub ‘De-Peaking’ Would Work: Delta Plan Spreads Out Flights, Lengthens Connect Times.” Atlanta Journal Constitution. http://archives.californiaaviation.org/airport/msg31841.html.

Holloway, S. 2008. Straight and Level: Practical Airline Economics. 3rd ed. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

Hunter, L. 2006. Low-Cost Airlines: Business Model and Employment Relations. European Management Journal 24 (5): 315–21.

Kumar, S. G. 2005. “Low-Cost Business Model.” In Low Cost Carriers—Concepts and Cases, edited by R. Barath. Hyderabad, India: The ICFAI University Press.

Mederer, M., G. Klempert, and Lufthansa. 2008. “De-peaking des Lufthansa-Hub-Betriebs am Flughafen Frankfurt” In Advances in Simulation for Production and Logistics Applications, edited by M. Rabe. Stuttgart, Germany: Fraunhofer IRB Verlag.

MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). 2013. MIT Airline Data Project (online). http://web.mit.edu/airlinedata/www/default.html.

Oliviera, A. 2008. “An Empirical Model of Low-Cost Entry.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 42 (4): 673–95.

Perkins, E. 2012. “Airlines Fight with Distribution Systems.” Chicago Tribune (online). http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-10-10/travel/sns-travel-ed-perkins-airlines-fight-with-distribution-systems-20121010_1_gds-first-airline-fare-packages.

RITA (U.S. Research and Innovative Technology Administration) BTS (Bureau of Transportation Statistics). 2013. “Airline On-Time Statistics and Delay Causes.” June 2012–June 2013. http://www.transtats.bts.gov/OT_Delay/ot_delaycause1.asp?display=data&pn=1.

Ryanair. 2013. http://www.ryanair.com.

Schlesinger, J. 2011. “10 Minutes That Changed Southwest Airlines’ Future.” CNBC News, July 15. http://www.cnbc.com/id/43768488.

Southwest Airlines. 2012. South West Airlines One Report. http://www.southwestonereport.com/2012/pdfs/2012SouthwestAirlinesOneReport.pdf.

Southwest Airlines. 2013. http://www.southwest.com.

Tarry, C. 2010. “Focus: Low-Cost Commodity.” Airline Business, January 21. http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/focus-low-cost-commodity-337437.

Vasigh, B., K. Fleming, and T. Tacker. 2008. Introduction to Air Transport Economics: From Theory to Applications. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

Warnock-Smith, D., and A. Potter. 2005. “An Exploratory Study into Airport Choice Factors for European Low-Cost Airlines.” Journal of Air Transport Management 11 (6): 388–92.

Weisskopf, N. 2010. Global Expansion Strategies for Low-Cost Airlines. Unpublished dissertation, University of Edinburgh.

World Bank. 2011. Air Transport and Energy Efficiency. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zhang, A., S. Hanaoka, H. Inamura, and T. Ishikiura. 2008. “Low Cost Carriers in Asia: Deregulation, Liberalisation and Secondary Airports.” Research in Transportation Economics 24 (1): 36–50.