Table 2.1 Selected Air Transport Impact Studies

Research has provided well-documented evidence that the development of air transport services can have a substantial economic benefit for a country or region. The focus of this chapter is to highlight some of this research, particularly the benefits that the entrance of low-cost carriers (LCCs) have brought to air transport and related markets.

There is a wealth of studies assessing the economic impact of air services. The focus of these studies is primarily on the correlation between air transport and gross domestic product (GDP), trade, investment, productivity, employment and/or effects on related industries (ACRP 2008).

The majority of impact studies in current aviation literature are based on input-output analysis. Developed by the economist Wassily Leontief, input-output or interindustry analysis describes and quantitatively portrays the interdependency between different economic sectors (Leontief 1986). It normally measures the direct, indirect, and induced impact of an industry. In the case of aviation, input-output analysis looks primarily at (a) the employment and output in the aviation sector (direct impact); (b) employment and activity originating from aviation’s supply chain (indirect impact); and (c) the employment or economic output resulting from household spending of directly or indirectly employed actors (induced impact) (Ishutkina and Hansmann 2009).

Studies using input-output analysis are particularly useful in mapping the impact of changes in demand. For example, increased demand for air services will consequently be matched by an increase in aviation services offered by airlines. This in turn benefits the industry’s supply chain, as there is increased demand from airlines for aircraft, ground handling, and other products and services. Increased disposable household income, resulting from increased employment, will consequently be re-spent on goods and services. Input-output analyses try to quantify these impacts.

Due to data intensity, the focus of this type of study is often on a specific airport or region and mostly in developed countries. In the United States, for example, a multitude of studies have been commissioned by airports and regions to assess the economic impact of aviation (for example, the Texas Department of Transportation 2011; Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments 2003). Other examples of input-output studies include the “Economic Contribution of Civil Aviation” study by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO 2004), and an economic impact study conducted by the Advisory Council for Aeronautics Research in Europe (ACARE) in 2003 (ACARE 2003).

Although prominently used in aviation literature, input-output analyses fail to capture the enabling or catalytic impacts of aviation and may therefore provide an incomplete picture. Catalytic impacts refer to the economic impact air transport can have on employment and income generated by economic activities which rely on the availability of air transportation (Ishutkina and Hansmann 2009).

Recent studies are increasingly trying to analyze the catalytic effect of air transport. Quantifying the enabling impact of air transport is very complex, however, as it is problematic to isolate the effects of air transportation from uncontrolled variables, such as institutional arrangements or globalization (Ishutkina and Hansmann 2009). Furthermore, it can be difficult to distinguish whether interrelationships are based on correlation or causality. Finally, obtaining the required data on investments and productivity can be challenging, particularly in developing countries.

Both Oxford Economics and Intervista Consulting have produced reports on behalf of aviation organizations such as Eurocontrol, the International Air Transport Association (IATA), and the Air Transport Action Group (ATAG). These studies estimate the enabling effects of aviation on tourism, trade, local investment, and productivity improvement. There are also a handful of academic studies that focus on the enabling effects of aviation (Button and Taylor 2000; Bel and Fageda 2005).

In addition, a number of research papers analyze the impact of changes in air transport policy or regulation of aviation services. The effects of air transport liberalization, domestically and internationally, and its influence on traffic volumes, prices, and networks, and consequently tourism, employment, and GDP, are of particular prominence in these types of studies. The consultancy Intervista, for example, has published a series of studies on the impact of air transport liberalization between 2006 and 2009 (Intervista Consulting 2006–09), as has Oxford Economics (Oxford Economics 2011). The former uses a gravity model that is able to forecast traffic between any two given countries. The model, developed in its core study (Intervista Consulting 2006–09), uses economic, trade, and geographic factors as well as the attributes of the respective air service agreements (ASAs) between the two countries as key variables to forecast traffic volumes. Cross-sectional data from over 800 country pairs were collected, based on the assumption that a specific relationship between traffic, liberalization, and socioeconomic conditions was valid in every market. The study then applied this model to a number of countries including Chile, Singapore, and Uruguay. Although providing a rigorous generic framework for quantifying passenger traffic post-liberalization, the model is unfortunately not able to take into account certain market-specific factors. This limits its validity in certain cases (Ishutkina and Hansmann 2009).

To complement these more generic frameworks, there have also been multiple case studies analyzing the effects of liberalization in specific countries or regions. ComMark, for example, produced a report on the economic importance of air transport liberalization in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) in 2006, including country- and region-specific factors in their analysis (ComMark 2006).

The overall challenge with studies of this kind originates from the interrelationship between some of the variables used in impact studies. For example, export and trade figures are intrinsically linked to GDP. When including these variables in the regression analyses, used by most impact studies, it is difficult to isolate the impact of each individual variable on air traffic growth (Ishutkina and Hansmann 2009).

Economic impact studies in aviation are also increasingly highlighting the negative impacts of aviation growth including noise and pollution and the economic cost associated with these negative externalities.

An overview of the key impact studies is provided in table 2.1. A summary of all additional economic studies can be found in appendix C.

Table 2.1 Selected Air Transport Impact Studies

Building upon the research evidence above, the remaining part of this chapter will focus on highlighting some of the more specific effects that have been observed with regard to LCC market entry. These include not only the impact on the air transport market in terms of traffic and fare levels, but also on directly related and even unrelated industries.

Research on the impact of LCCs is still not as common as expected due to the difficulty of linking the impact of increased air transport to any one particular business model. However, a number of studies have identified some common effects related to the entrance of LCCs. Figure 2.1 graphically illustrates the sequence of these effects.

Figure 2.1 Flowchart of LCC Impact

Note: LCC = low-cost carrier; SME = Small and medium enterprises.

Unfortunately research on LCC market entrance is currently almost entirely focused on developed countries and regions, particularly Europe and the United States. This is mostly related to the fact that the more recent emergence of LCCs in new markets means that the required data are often unavailable.

In 1993, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) conducted a study on the impact of LCC entrants on the U.S. airline market. Coining the term “Southwest Effect,” the DoT researchers Randall Bennett and James Craun focused on three different aspects of how Southwest Airlines impacted the aviation market, namely through (a) direct competitive effect in terms of passenger growth and fare reduction on a given route where Southwest had entered; (b) the lowering of fares at surrounding airports through Southwest’s entry; and (c) the role model effect, exhibiting the impact Southwest has on the business models of new entrants in other markets (Bennett and Craun 1993).

Focusing on the California corridor, the study presented evidence that Southwest’s entry had a significant impact on all three aspects outlined above. On the Oakland–Burbank route, for example, where Southwest entered in 1990, prices dropped by 55 percent, and passenger traffic increased sixfold between its entrance and the 3rd quarter of 1992 (Bennett and Craun 1993). The study confirmed some of the prior research that had been conducted by Whinston and Collins (1992), showing that the entry of low-cost airline People Express had resulted in a decrease in the mean fare level of 34 percent on 15 domestic routes between 1984 and 1985 (Whinston and Collins 1992).

Since then, numerous studies have been conducted focusing on the different areas (traffic, competition, and fares) of the Southwest Effect in the U.S. market (Windle and Dresner 1995; Dresdner, Lin, and Windle 1996; Richards 1996; Morrison 2001; Vowles 2001; Pitfield 2008; and Wu 2011). All of these studies confirm, to varying extents, the effect the entry of low-cost airlines has had on the air transport market.

Dresdner, Lin, and Windle (1996), for example, examined the effect of LCCs on other routes serving a specific airport, as well as on routes served by other airlines at surrounding airports. Using data of the top 200 origin/destination (O/D) markets, results indicated that the presence of LCCs contributed to lower yields and increased traffic on the route entered, as well as on competitive routes. Applying a regression analysis, the authors calculated that yields were reduced by approximately 53 percent on routes that Southwest had entered. The presence of LCCs in general resulted in a 38 percent yield reduction on average. On competitive routes originating in or terminating at surrounding airports, yields dropped between 8 and 45 percent if Southwest operated on that route, and between 0 percent and 41 percent if any LCC was present. Focusing on average fares and traffic, Windle and Dresner (1995) calculated an average price drop of 48 percent and a traffic increase of 200 percent on Southwest routes between 1991 and 1994.

The most comprehensive study on the Southwest Effect was completed by Morrison (2001). The author estimated that the entrance of Southwest on a route lowered fares by 46.2 percent. In his calculations for 1998, these lower fares resulted in direct savings of US$3.4 billion for passengers with an additional US$9.5 billion achieved through the effects of actual, adjacent, and potential competition from Southwest on other carriers’ fares.

In Europe, the entrance of LCCs has also led to substantial fare decreases and attendant demand stimulation (Franke 2004; Dobruszkes 2006; and Alderighi and others 2012). According to Dobruszkes (2006), 50 percent of additional seats between 1995 and 2004 were provided by low-cost airlines. On the London–Barcelona route, for example, the entrance of LCCs easyJet and Debonair in 1995 increased traffic by 32 percent within one year of operation. This stands in comparison to a 7 percent growth rate in previous years (U.K. CAA 1998). In the Dublin–London market, between the entrance of Ryanair in 1986 and 2000, traffic demand quadrupled while yields dropped to one-fourth (Franke 2004).

In the European market, particularly low yields persisted over longer periods of time as network carriers such as British Airways responded with aggressive pricing. In some cases this even led to financial difficulties for LCCs, as they had to maintain lower fares for longer than initially intended. Ryanair’s average fare decreased from approximately EUR60 in 2000 to EUR46.50 in 2003, representing a decline of 22.5 percent (Doganis 2006).

Due to the data intensity of this type of research, studies in other aviation markets have been more limited in number and scientific nature. In a study of the Republic of Korea island Jeju, Chung and Wang (2011) showed that LCCs accounted for 35 percent of total passengers in 2009 on the Seoul–Jeju Island route, corresponding to an average growth rate of 161.7 percent between 2005 and 2009. This stands in contrast to a negative growth rate of −0.3 percent for full-service carriers. Furthermore, a report issued under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)–Australia Development Cooperation Program (AADCP) looked at the impact of LCCs in Southeast Asia. Referring to an article in Asia Times in 2004 (Raja 2004), the report highlights that the entrance of LCCs has led to an overall decrease in fare levels in the market. For example, network carriers such as Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines were required to cut fares by almost half in order to compete with Singapore-based LCC Valueair (Damuri and Anas 2005).

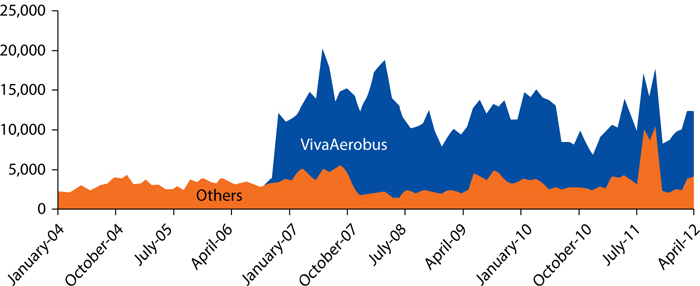

Research highlights the particular importance of the stimulation of new demand resulting from reduced fares. New demand refers to passengers who have, due to a variety of reasons, never flown before. Various studies (Lawton 2002; Campisi, Costa, and Mancuso 2010) emphasize that the traffic generated by LCCs is a result of demand stimulation rather than cannibalization of existing carrier passenger traffic. Box 2.1 highlights this demand stimulation by the example of VivaAerobus in Mexico.

Box 2.1 Demand Stimulation—The Case of VivaAerobus

In 2006, the low-cost carrier (LCC) VivaAerobus entered the Mexican market. Despite not being the first LCC in the market, VivaAerobus’s “lowest cost” model had a tremendous impact on the country’s aviation market. With fares of sometimes up to 50 percent lower than their network competitors, the carrier stimulated considerable new traffic (see figure B2.1). Furthermore, one-third of the carrier’s approximately 50 routes were previously not served, creating new traffic and improving connectivity. According to the company’s research, a quarter of its passengers are actually first-time travelers, which had previously relied on bus or other means of transportation. With similar average fares between VivaAerobus and domestic long-distance bus services, the airline estimated the potential bus-to-air trade-up market to be 300 million passengers in 2012.

Figure B2.1 Traffic Evolution Pre- and Post-LCC Entrance, Monterrey–Verracruz

number of passengers

Source: VivaAerobus 2012.

Note: LCC = low-cost carrier.

The effects of low-cost airlines go far beyond fare levels and passenger traffic. The correlation between LCC entrance and tourism is particularly well documented in aviation literature.

The European Low Fares Airline Association (ELFAA) has grouped these benefits to tourism into three categories: (a) an increase in tourist destinations due to the usage of secondary airports; for example the London–Strasbourg route, previously used primarily for business, has proved to become a popular tourist destination with the entrance of Ryanair; (b) a more even distribution of traffic throughout the year, reducing “seasonality effects”; and (c) low off-peak fares, which have enabled mid-week holiday travel. This has had the beneficial effect of distributing traffic more evenly across the week and reducing airport congestion (ELFAA 2004).

Although this area is still underresearched, the effects outlined above have been supported by a variety of reports and studies. The European Travel Commission (ETC), for example, has continuously recorded in its annual Tourism Insight Report (ETC 2007) that LCCs have been the main driver for travel growth and tourism demand across Europe. The extension of the European Union (EU) Open Skies to the new EU member states in Eastern Europe in particular has resulted in a significant increase in LCC travel. According to Dobruszkes (2006), LCCs represented about 60 percent of new air services on west–east routes. This stimulated tourism in the region, in particular for cities such as Budapest, Warsaw, Krakow, and Prague, as well as for smaller towns and rural regions. For Krakow for example, the number of foreign tourists rose from 680,000 to almost 2.5 million between 2003 and 2007. In the same time period, foreign tourist arrivals by air increased from 19 percent to 63 percent. This has been driven significantly by the entrance of low-cost airlines, such as Ryanair (Olipra 2012).

Using a dynamic panel data model, Rey, Myro, and Galera (2011) showed that the entrance of LCCs has had a significant impact on tourism demand for the major six comunidades autónomas (CCAA; autonomous communities or provinces) in Spain from the top 10 EU countries in terms of income per capita. The study estimates that a 10 percent rise in the number of visitors using LCCs would increase tourist per capita figures from EU-15 countries by 0.2 percent. With the LCC share of passenger traffic having risen from 10 percent in 2000 to 53 percent in 2009, the projected impact is substantial.

Another study by Hoersch (2003) estimated the impact of Ryanair on the rural area around Frankfurt Hahn (Hunsrueck region). The author notes an increase from 2.17 million of total overnight stays in 1998 to 2.34 million in 2002 in Hunsrueck.

An analysis by the University of Santa Anna, Pisa (2003) estimated that in 2003, more than 480,000 passengers arrived in Pisa on low-cost airlines. Sixty-five percent of those passengers were foreign travelers, with 62.2 percent traveling for tourism and the remaining 37.8 percent for business. The per capita consumption for tourist and business travelers was estimated at around EUR497 (US$664) and EUR431 (US$575) respectively. In total, both tourist and business travelers generated almost EUR150 million (US$200 million).

The entrance of LCCs has particularly affected tourism on islands, as well as in smaller cities and in remote regions where secondary airports are located. This growth in tourism and consequent increase in employment and accommodation revenues has been analyzed by various authors (Signorini, Pechlaner, and Rienzner 2002; Gonçalves 2009; Donzelli 2010; Graham and Dennis 2010; Chung and Wang 2011; and Olipra 2012). Chung and Wang (2011), for example, attribute the growth in the number of tourists and accommodation revenues in Jeju Island almost entirely to the entrance of LCC Jeju Air. Research by Donzelli (2010) also showed that the opening of a new LCC route could result in EUR14.6 million in additional net income per year for locals in southern Italy, resulting largely from tourism income.

Furthermore, Aguilo and others (2007) and Donzelli (2010) highlight that the entrance of LCCs has not only impacted tourism numbers, but has also shifted traffic patterns, thereby reducing seasonality. This is assumed to be due to the flexibility of LCC schedules as well as the affordability of multiple shorter trips a year. However, results of studies estimating the effect on seasonality have been mixed, with some research finding only limited impact on seasonality in their markets (Chung and Wang 2011).

With regard to the impact of LCCs on domestic traffic and tourism, differing opinions have emerged. Whyte (2007), in his analysis of the Australian tourism market, finds that the entrance of LCC Virgin Blue has not resulted in an increase in domestic tourism in Australia, but has just shifted travelers from different transport modes to air travel. In the case of car-to-plane shifts, some smaller regional areas, which cars had previously been driving through, have suffered from the entrance of LCCs. Furthermore, the availability of lower international airfares has enabled people to travel abroad for their holidays.

A number of studies have also focused on other impacts of LCCs. Williams and Balaz (2007) examined the impact of LCCs on flows of labor, migrants, knowledge, business connectivity/investment, and mobile markets (also looking at tourism in particular). In the absence of empirical evidence, the study shows how labor migration can be impacted in its composition due to the availability, frequency, and costs of air travel. A few other studies have also focused on the impact of LCC on migration. According to Button and Vega (2008), the reduced travel costs and increased accessibility that have been achieved through LCCs lower the overall cost of international labor migration. This includes not only the costs of transportation itself, but also the social costs resulting from the separation from families. As the authors observe, LCC entrance does not only reduce the cost of immigration, but can actually induce migration.

Murakami (2010) also looked at the effect of LCCs on social welfare in the United States. His empirical analysis showed that gains from lower fares can be substantial in some cases. Of these gains, 90 percent result from consumer surplus, with the rest originating directly from the profit of LCCs.

The development of air services can have a crucial impact on the aviation market, and consequently on other related and even unrelated industries. As the previous chapter highlights, there are a variety of studies, varying in scope and methodology, assessing the impact of air transport. These often focus on the direct, indirect, and induced impact of air transport—but more recently, also on the catalytic or enabling impact of air transport. They have shown air transport to have a considerable positive impact on employment, GDP, trade, tourism, and productivity, among others.

Although research is still limited, LCCs have been proved to have a significant positive impact on air transport and related markets. Research on the impact of low-cost airlines has been more scarce due to causality issues, but some organizations and scholars have quantified the impact of LCC entry. Particular focus has been on the impact of LCCs on traffic stimulation through lower fares and their overall impact on competition and fare levels in the market. This type of research is still limited in developing countries however.

Tourism has been a key industry in the LCC equation. Due to the nature of LCCs, the key focus in most research has been on leisure travelers, and the effects on tourism, particularly for island states and remote regions. Research on the impact of LCCs in developing countries is, however, still sparse due to the lack of reliable data. This research and knowledge gap remains to be filled.

Having highlighted the positive impact LCCs can have in enabling access to air transport to a wider strata of society, the next chapters identify the opportunities that exist for the development of LCCs in developing countries. Chapter 3 outlines the experiences of two countries that have seen the emergence of LCCs in recent years. Based on the findings from the chosen case studies and complemented by stakeholder interviews, chapter 4 establishes a framework of key criteria that would enable the development of low-cost airlines in developing countries.

ACARE (Advisory Council for Aeronautics Research in Europe). 2003. The Economic Impact of Air Transport on the European Economy.

ACRP (Airport Cooperative Research Program). 2008. Airport Economic Impact Methods and Models: A Synthesis of Airport Practice. Transportation Research Board ACRP, Synthesis 7.

Aguilo, E., Rey, B., Rossello, J., and Torres, C. 2007. “Impact of the Post-Liberalisation Growth of LCCs on the Tourism Trends in Spain.” Rivista di Politica Economica I–II: 39–60.

Alderighi, M., Cento, A., Nijkamp, P., and Rietfeld, P. 2012. “Competition in the European Aviation Market: The Entry of Low-Cost Airlines.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 223–33.

Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments. 2003. Airports Economic Impacts Study for Monterey, San Benito, and Santa Cruz Counties.

Bel, G., and Fageda, X. 2005. Getting There Fast: Globalization, Intercontinental Flights and Location of Headquarters. University of Barcelona.

Bennett, R., and Craun, J. 1993. The Airline Deregulation Evolution Continues: The Southwest Effect. Office of Aviation Analysis, U.S. Department of Transportation.

Button, K., and Taylor, S. 2000. “International Air Transportation and Economic Development.” Journal of Air Transport Management 6 (4): 209–22.

Button, K., and Vega, H. 2008. “The Effect of Air Transport on the Movement of Labour.” Geojournal 71 (1): 67–81.

Campisi, D., Costa, R., and Mancuso, P. 2010. “The Effect of Low-Cost Airlines Growth in Italy.” Modern Economy 1: 59–67.

Chung, J., and Wang, T. 2011. “The Impact of Low Cost Carriers on Korean Island Tourism.” Journal Transport Geography 19 (6): 1335–40.

ComMark. 2006. Clear Skies over Southern Africa: The Importance of Air Transport Liberalisation for Shared Economic Growth. http://www.tourisminvest.org/Mozambique/downloads/Investment%20climate%20background/Infrastructure/Clear%20Skies%20over%20Africa.pdf.

Damuri, Y. and Anas, T., 2005. Strategic Directions for ASEAN Airlines in a Globalizing World—The Emergence of Low-Cost Carriers in South East Asia. ASEAN–Australia Development Cooperation Program. ASEAN–Australia Development Cooperation Program. http://www.aadcp2.org/uploads/user/6/PDF/REPSF/04-008-FinalLCCs.pdf.

Dobruszkes, F. 2006. “An Analysis of European Low-Cost Airlines and Their Networks.” Journal of Transport Geography 14 (4): 249–64.

———. 2009. “New Europe, New Low-Cost Air Services.” Journal of Transport Geography 17 (6): 423–32.

Doganis, R. 2006. The Airline Business. 2nd ed. Oxon, U.K.: Routledge.

Donzelli, M. 2010. “The Effect of Low-Cost Air Transportation on the Local Economy: Evidence from Southern Italy.” Journal of Air Transport Management 16 (3): 121–26.

Dresdner, M., Chris Lin, J.-S., and Windle, R. 1996. “The Impact of Low-Cost Carriers on Airport and Route Competition.” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 30 (3): 209–328.

ELFAA (European Low Fares Airline Association). 2004. Benefits of LFAs. http://www.elfaa.com/documents/ELFAABenefitsofLFAs2004.pdf.

ETC (European Travel Commission). 2007. European Tourism Trends 2007. http://www.etc-corporate.org/images/library/etc_tourism_insights_2007.pdf.

Franke, M. 2004. “Competition between Network Carriers and Low-Cost Carriers.” Journal of Air Transport Management 10 (1): 15–21.

Gonçalves, S. 2009. The Impact of Low-Cost Airlines on Madeira Islands. ISCTE Business School.

Graham, A., and N. Dennis. 2010. “The Impact of Low-Cost Airline Operations to Malta.” Journal of Air Transport Management 16 (3): 127–36.

Hoersch, S. 2003. Low-Cost Airlines: A Veritable Chance for the Development of Small Airport and Regional Tourism? Bournemouth University. http://www.du.se/PageFiles/5050/ETM%20Thesis%20Hörsch.pdf.

ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization). 2004. Economic Contribution of Civil Aviation. http://legacy.icao.int/ATWorkshop/C292_Vol1.pdf.

Intervista Consulting. 2006–09. The Impact of International Air Service Liberalization Country Studies. [For example, Morocco, Singapore, Chile.] http://www.iata.org/policy/liberalization/agenda-freedom/Pages/studies.aspx.

Intervista Consulting. 2006. The Economic Impact of Air Service Liberalisation. http://www.transportstrategygroup.com/persistent/catalogue_files/products/06EconomicImpactOfAirServiceLiberalization_FinalReport.pdf.

Ishutkina, M., and Hansmann, J. 2009. Analysis of the Interaction between Air Transport and Economic Activity. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Lawton, T. 2002. Cleared for Take-Off. Surrey, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Leontief, W. 1986. Input-Output Economics. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Morrison, S. 2001. “Actual, Adjacent and Potential Competition Estimating the Full Effect of Southwest Airlines.” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 35 (2): 239–56.

Murakami, H. 2010. Time Effect of Low-Cost Carrier Entry and Social Welfare in US Large Air Markets. Hideki Murakami, Graduate School of Business, Kobe University.

Olipra, L. 2012. “The Impact of Low-Cost Carriers on Tourism Development in Less Famous Destinations.” Article as part of the project: The Impact of Air Transport on the Regional Labor Markets in Poland, financed by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Project no. N N114 180039.

Oxford Economics. 2011. Economic Benefits of Air Transport Country Studies. http://web.oxfordeconomics.com/OE_Cons_Aviation.asp#.

Pitfield, D. E. 2008. “The Southwest Effect: A Time Series Analysis on Passengers Carried by Selected Routes and a Market Share Comparison.” Journal of Air Transport Management 14 (3): 113–22.xs

Raja, M. 2004. “No-Frills Flying Takes Off in Asia.” Asia Times, May 22. http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/FE22Df06.html.

Rey, B., Myro, R., and Galera, A. 2011. “Effect of Low-Cost Airlines on Tourism in Spain. A Dynamic Panel Data Model.” Journal of Air Transport Management 17 (3): 163–67.

Richards, K. 1996. “The Effect of Southwest Airlines on U.S. Airline Markets.” Research in Transportation Economics 4: 33–47.

Signorini, A., Pechlaner, H., and Rienzner, H. 2002. “The Impact of Low Fare Carrier on a Regional Airport and the Consequences for Tourism—The Case of Pisa.” 52nd AIEST Congress Publication. In Air Transport and Tourism, edited by T. Bieger and P. Keller. St. Gallen, Switzerland: AIEST.

Texas Department of Transportation. 2011. General Aviation in Texas: Economic Impact 2011. http://ftp.dot.state.tx.us/pub/txdot-info/avn/tx_econ_tech.pdf.

U.K. CAA (United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority). 1998. Single European Aviation Market: The First Five Years. CAP 685 report.

University of Santa Anna, Pisa. 2003. “Study on Low-Cost Airlines.” European Low Fare Airlines Association Presentation at Annual Asia Pacific Low-Cost Airline Symposium 2005. http://www.elfaa.com/documents/ELFAAPresentation-2ndAnnualAsiaPacificLowcostAirlin.pdf.

VivaAerobus. 2012. Overview of VivaAerobus. Unpublished presentation.

Vowles, T. M. 2001. “The ‘Southwest Effect’ in Multi-Airport Regions.” Journal of Air Transport Management 7 (4): 251–58.

Whinston, M., and Collins, S. 1992. “Entry and Competitive Structure in Deregulated Airline Markets: An Event Study Analysis of People Express.” The RAND Journal of Economics 23 (4): 445–62.

Whyte, R. 2007. “Impacts of Low-Cost Carriers on Regional Tourism.” Proceedings of the 17th Annual CAUTHE Conference, Sydney, Australia. http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/3189/1/3189_Whyte_2007.pdf.

Williams, A. and Balaz, V. 2007. “Low-Cost Airlines, Economies of Flow and Regional Externalities.” Regional Studies 43 (5): 677–91.

Windle, R. J., and Dresner, M. E. 1995. “The Short and Long-Run Effects of Entry on US Domestic Air Routes.” Transportation Journal 35 (2): 14–26.

Wu, S. 2011. “The Southwest Effect Revisited: An Empirical Analysis of the Effects of Southwest Airlines and JetBlue Airways on Incumbent Airlines from 1993 to 2009.” Michigan Journal of Business 5 (2): 11–40.