1. Do you feel you’re getting shorter over time?

2. Have any back problems?

3. Do you ever get a sore neck? Frequently? Often?

4. Are you a cell phone user? Sometimes? Exclusively?

5. Have you been told that you have elevated hemoglobin A1c?

6. Do charbroiled foods show up frequently in your diet?

7. Any memory problems?

8. Do you have a weight problem even though you watch your calories like a hawk?

9. Is your waist-to-hip ratio greater than 1?

10. Do you eat a lot of foods and drinks stored in plastic containers?

11. Are you one of those people who are “cold all the time”?

12. Have you been told you have reduced bone mass?

13. Are you menopausal?

14. Do you pretty much avoid dairy products?

15. Do you eat proportionally way more animal protein than vegetables?

In 1951, the proceedings of the august National Academy of Sciences featured seven studies by the same two authors, chemists Linus Pauling and Robert Corey, reporting on their research on protein structure and its relationship to protein function. That same year, Pauling delivered a lecture entitled “Molecular Medicine,” the term he had first coined two years earlier and one that crystallized the practical application of the seven collaborative papers in the proceedings. Practically speaking, Pauling stated that if we understand the structure of human biology at the molecular level, we can understand how and why it functions as it does. As he is reputed to have put it, “Get the structure right, and the function will follow.”

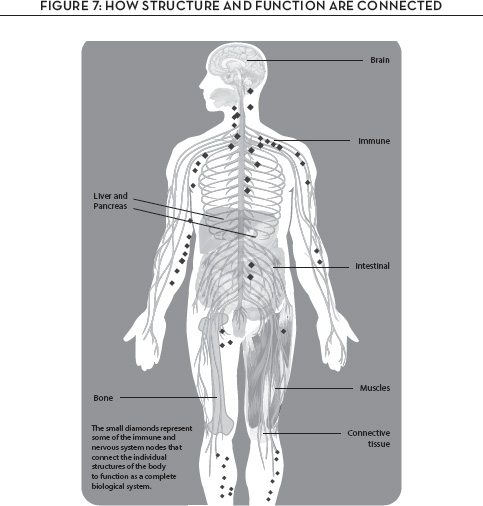

We think of physiological structure as our skeleton, muscles, connective tissue, and organs—see Figure 7—and we assume the structure to be immutable and permanent. Not so. For one thing, everything in our body is replaced on a regular basis—our red blood cells every three months, the mucosa of our digestive tract every few days, our bones every few years. At the molecular level, the level of the smallest building blocks of those structural elements, the proteins that make up our organs and connective tissue, the calcium compound—called hydroxyapatite—that is the bone mineral of our skeleton, plus the lipids of our fat stores, the amino acids of our muscles, and the nucleic acids of our DNA are all being broken down and remade every day. In other words, structure is always changing.

That is significant because structure affects function. When we know what each building block is, why it is where it is, and how it connects to the other building blocks and levels of structure in the body, we can also know how the building blocks affect function. And if we follow Pauling’s insight about the relationship between structure and function—that is, that our structure at every level can change—we come to understand how function can therefore change as a result.

It is really only now, in the wake of the genomic revolution, that the health implications of that relationship are being fully recognized in medicine. If creating and maintaining structure are ongoing processes from which function emerges, then we can see chronic illnesses as originating precisely in a structural problem in the body manifesting itself as functional symptoms. We can try to correct the functional symptoms, but if the underlying structural problem is not resolved, the condition will continue; in fact, it will progress.

What the genomic revolution has taught us is that we can speak to and affect our structure. Our genes carry information pertinent to the creation of our structure at every level—molecular, cellular, at the level of tissue and organ structure, at the level of the whole organism. As in a hologram, each level of structure is reflected within the others, and each is seen inside the others. But factors of our environment, lifestyle, and diet can reach into all the dimensions of this hologram to influence the way genetic messages are expressed. Environment, lifestyle, and diet can all place epigenetic marks on the genes, turning the volume up or down on specific genes, as we put it in Chapter 2. This means that our structure at every level and therefore our function can change as a result.

This chapter is about how that physiological process works to affect our health.

SPEAKING TO OUR STRUCTURE . . . BUT MAYBE NOT ON A CELL PHONE

It’s almost a cliché to talk about the body’s structure in terms of architecture, but it is not entirely inappropriate to do so. Like a building—say, a city skyscraper—the human body is engineered for stability; both skyscraper and human are able to withstand the power of nature and the force of gravity over time and remain upright.

But now endow the skyscraper with the ability to move. Will the engineering for stability that went into it when it was stationary still be adequate for the building in motion? Probably not; keeping the structural components aligned is much more complicated in a moving building than in a stationary one. Some reengineering is needed.

Now add another engineering challenge: The skyscraper must not only maintain its stability while it is in motion; at the same time, it must keep all its functions operating—communications, repair, energy production, and mechanical work. That is a formidable engineering challenge requiring a lot of complex interactions. Yet it is exactly what the human body is expected to do.

But this complexity in the body’s structural architecture creates its own challenges. Life happens, as they say, and some of its events just may, for example, distort the alignment of the bones, muscles, or nerves. You’ve probably had a sore neck at some point in your life, or you pulled out your back, or you got tennis elbow even if you never played tennis. These are signals that something structural is out of line.

And when the structural alignment is altered, then, by definition, the function is altered as well. Pain is one such alteration, but so is the appearance of inflammation, or a swelling in the body, or a change you can’t see in one or more of the core physiological processes like defense or transport.

These associations between the body’s structural alignment and changes in function have been observed since the dawn of medicine in the Ayurvedic and Chinese traditions. Over the course of some two thousand years, the practitioners of these traditions perfected various forms of manipulation—among them therapeutic massage, chiropractic, osteopathy, yoga and other forms of exercise movement, and acupuncture. The driving thrust in all these practices is to create or regain the proper alignment of bones, muscles, and nerves so that the structure can effectively manage the stress and strain of a body in motion.

Here in the West, in at least some sections of the medical establishment, there’s a lingering controversy over the efficacy of manipulative therapy, probably because until recently, we had no direct knowledge of a mechanism by which such therapies could alter cellular function and thereby directly affect health or disease. But as with so many of the shibboleths we grew up with, the findings of the genomic revolution have started to change that. Witness the work of academic neurologist Helene Langevin and her colleagues at the University of Vermont College of Medicine, which is offering a new view of the physiological effect of these kinds of physical medicine. Under very carefully controlled conditions, Langevin’s group has been measuring the effect on cellular function of inserting an acupuncture needle into the skin. Just below the skin is a whole extracellular matrix—sort of like the glue of our connective tissue—full of nerves constituting a signaling system to the brain and other parts of the body. Pass a feather or even your fingernail lightly along your inner arm and you’ll sense this intuitively as you feel a tingling, almost ticklish sensation that is quite pleasant. What is not so intuitive, however, is what Langevin and her group have found out—that this signal going through the skin and the extracellular matrix just below it is also activating specific signal transduction pathways and thereby influencing gene expression. It is regulating cell behavior and therefore cellular function.

If we extrapolate out from the influence of acupuncture on cellular function, we can find implications for various forms of physical medicine—including exercise. It too is a kind of targeted manipulation of the body, and such manipulation, we now know, sends mechanical signals that are translated through the nerves in the extracellular matrix. These signals are received by receptors on the surface of cells within both the nervous and the musculoskeletal systems that then alter the cells’ expression of function. What an amazing connection this represents between our genes, our physical environment, and our health.

I can report on just such a connection in my own case, although I too had long been skeptical about physical medicine, even after hearing from patient after patient about how a specific manipulation therapy had solved a long-term health problem that had resisted all other treatments. I simply assumed the “solutions” were the result of a placebo effect.

Then my back, which I injured during my college basketball days and which periodically “goes out” if I move in a certain direction, became a serious issue. I travel thousands of miles a year, and as if airplanes aren’t uncomfortable enough, sitting in one for eight or ten or fourteen hours with a bad back can be sheer misery. I finally accepted a referral to a nearby chiropractic physician whose manipulation of my back relieved the pain and discomfort in minutes. I now keep a list of chiropractic and osteopathic physicians around the world so I can keep on keeping on while on the road. I can say without any ambiguity that the effect of these treatments is no placebo; it’s real.

There’s another interesting example of speaking to our structure, but with a less happy practical application. The idea that there are structures within the body that create and transmit an electromagnetic field was first articulated by Dr. Robert Becker in his 1985 book, The Body Electric. After all, as Becker pointed out in the book, brain electroencephalograms—EEGs—and the electrocardial or EKG patterns of the heart are reflections of the body’s electromagnetism.

At the cellular level, we also know that when mitochondria convert food to energy, their doing so creates a small electromagnetic field. Controlled studies have demonstrated that when mitochondria are exposed to a high magnetic field, they change their function.

In essence, we are electric beings. Our body’s structure operates like an antenna and a transmitter, picking up and sending out certain frequencies of low-energy radiation. What this means is that our structure and the function derived from it influence the electromagnetic environment around us, and the electromagnetic environment around us can influence our physiology.

So we come to the issue of electromagnetic pollution, the term used by Dr. Devra Davis, founder and president of the Environmental Health Trust,* and to the potential health effects from exposure to certain forms of nonionizing radiation. We all know of the health dangers from exposure to the ionizing kind of radiation—namely ultraviolet and X-ray forms of radiation; nonionizing radiation includes certain frequencies of background radiation in the microwave portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, the region of the spectrum used for cell phone communications.

It’s an emerging area of study, controversial, and potentially profoundly significant, given that estimates as of 2013 are that there are almost as many cell-phone subscriptions as there are people in the world.* That probably means, among other conclusions, that warnings or even cautions about possible health effects don’t have much chance of being heard. That’s too bad, because it’s an issue that ought to be raised, aired, and examined carefully.

Dr. Davis is not the only expert to contend that the structure of our bodies creates a susceptibility to adverse health effects from these nonionizing forms of electromagnetic radiation, and that the adverse effects primarily influence the nervous and immune systems. The influence is subtle but may be profound with long-term exposure. The World Health Organization has also issued a caution; its International Agency for Research on Cancer asserts that radiofrequency radiation, which cell phones emit, may possibly be carcinogenic to humans.*

These warnings have not been scientifically proved—yet. But until we know for sure, it probably makes sense to use a headset with your cell phone and to avoid, as much as possible, putting the phone directly against your ear where it is close to the brain.

PROTEIN STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION AND OUR HEALTH

The core message of the seven papers Pauling and Corey published in 1951 was that alteration in the structure of a protein can then modify the function of the protein and therefore of the individual. Much of the work that led to this conclusion was the landmark research on sickle-cell anemia Pauling carried out in the late 1940s in collaboration with biochemist Harvey Itano. The two men showed that the sickle-cell disease resulted from a genetic alteration in one part of the hemoglobin protein molecule. Simply put, the sickle-cell form of hemoglobin has a different shape from that of normal hemoglobin, and the difference makes the sickle-cell form of the protein molecule less flexible. As a consequence, the sickled form distorts the shape of the red blood cell, which then slices through the bloodstream—like a sickle through a wheat field—and in so doing, damages the body. That damage can produce grave symptoms in numerous organs—the kidneys, heart, liver—and in other tissues, all due to the alteration in the shape of one molecule.

That is why Pauling termed it a molecular disease, thus distinguishing it from an infectious disease in which a foreign invader causes a reaction that results in a disease process. You can kill the foreigner with an antibiotic, but you cannot kill a protein produced in the body, even if it has a different structure from other proteins. From a medical point of view, managing a molecular disease deriving from the altered structure of molecules requires a far different strategy from the pharmacology approach that can zap foreign organisms.

Many chronic diseases are the result of an alteration in the shape of specific proteins, and not all such alterations by any means are a result of a genetic characteristic as in sickle-cell anemia. Rather, these diseases result from alterations that occur in the protein cells after they are produced in the body. These changes are called post-translational modifications, and they derive from factors or events in the individual’s lifestyle, diet, and environment.

One of the best-known and best-understood examples of this is the altered form of the hemoglobin protein called A1c, or glycohemoglobin, used clinically as a measurement of diabetes. Typically, only a very small amount of the sugar called glucose combines in the blood with hemoglobin, so the level of glucose attached to the hemoglobin protein will be minimal—usually less than 5 percent. But when diabetes is present, with high blood sugar levels, the combination of glucose with the hemoglobin protein produces the altered form of the protein, glycohemoglobin. Levels of A1c above 6 percent are therefore biomarkers of the disease. Just above 6 percent, for example, is considered a signal of early-stage type 2 diabetes, and 8 percent or higher is an indication of poorly controlled diabetes.

Moreover, because the red blood cell where the hemoglobin resides has a four-month lifetime, the level of hemoglobin A1c provides a running record of the average blood sugar level over time. Since a single blood sugar measurement can provide varying results depending on when the person last ate, what he or she ate, and a host of other things going on in the person’s life that might influence insulin action, the A1c test provides information about the diabetic’s long-term control of blood sugar levels. It has become a key tool not just for diagnosing diabetes but for managing it as well.

COOK UP SOME CRUSTY PROTEINS

Hemoglobin is by no means the only protein connecting with sugar in the blood. This process—the sugar reaction of proteins—is called glycation, and it produces what I call “crusty” proteins. What’s crusty about these proteins? Actually, the combination of protein with sugar is precisely similar to what happens when crust forms on the bread you’re baking. You put it in the oven as a blob of dough with no distinguishing feature of appearance or taste. But as it bakes, the top layer, where the temperature is hottest, cooks into a crust that looks and tastes quite different from the inner part of the bread. Food chemists call the formation of the crust a Maillard reaction, the chemical reaction that takes place under heat between the glucose from the starch in the flour and the amino acid from the protein in the flour. This is exactly what happens in the blood, without heat, when blood sugar reacts with the hemoglobin protein to form the hemoglobin A1c, which also qualifies as a crusty protein.

In fact, glycation forms a whole bunch of crusty proteins. They are called advanced glycation end-products—AGEs. Each is a protein structure that is basically foreign to the body, and therefore each can stimulate an immune inflammatory response. And indeed, there are receptors on the surface of our immune cells known as receptors for advanced glycation end-products, or—you guessed it—RAGEs.

But here is where the important health story emerges. The more crusty-protein AGEs in the blood and tissues, the greater the risk for various AGE-related chronic diseases sparked by immune system responses. Put it this way: the more AGEs there are, the more the cells become enRAGEd. That is how the story of altered cellular communication associated with insulin resistance and diabetes gets tied together with altered protein structure to increase the risk for heart disease and arthritis. What look like independent diseases are really caused by the same alteration in the core physiological processes.

There’s more. We’re learning that the glycation products of protein can also be formed in our food and therefore ingested in our diets—with consequences. If you cook foods at high temperatures, advanced glycation end-products turn into glycotoxins. At the Icahn School of Medicine at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital, Dr. Helen Vlassara, professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine, has been evaluating the effects of these glycotoxins in both animals and humans. It’s not pretty. The crusting found in charbroiled meats, for example, produces glycotoxins that initiate an immune inflammatory response in the same way that AGEs produced in the body do—with similar adverse effect on health.

Vlassara’s work has shown rather convincingly that as our diets have become more processed through heat treatment, our intake of glycotoxins has also increased, and that this increased intake has contributed to the rising incidence of such chronic illnesses as type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, and dementia. In animal studies, the progression of these illnesses goes up when the test animals ingest glycotoxins, which cause an increased inflammatory response. In humans, the evaluations note higher blood levels of glycotoxins in people known to have these diseases. The lesson seems to be to reduce the consumption of charred meats and to lower the cooking temperature in general. Reduced cooking temperatures result in reduced production of glycotoxins.

So the bottom line is that as the structure of proteins is altered, there is an alteration in their physiological effect—an alteration in the way they function—whether the altered structure is produced in the body or ingested.

The extreme example is the case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or BSE, first identified in England in 1986. In a way, it all came about thanks to an accident of history. Cattle have traditionally been raised on vegetable foods, and for English cattle, soybean meal was the food supplement of choice for most cattle farmers. But in the early 1980s, the cost of soybean meal began to rise, and since little soy was grown on English farms and no price controls could be put in place, cattlemen turned to an alternative food supplement—namely, the remains of dead and diseased animals, both cows and sheep.

Within a few years after this supplement was introduced, a number of cattle began to show signs of a strange illness. They became unable to stand on all fours, grew aggressive, and seemed demented. After a while, the cattle died. Postmortems showed a spongy degeneration in the brain and spinal cord of the animals; veterinarians gave the disease a name that captured that degeneration—bovine spongiform encephalopathy—but everyone called it mad cow disease. This neurodegenerative disease has a long incubation period, anywhere from about two and a half to eight years; it affects adult cattle between four and five years of age, and it is fatal. But the authorities didn’t wait: after more than 180,000 cattle were found affected, 4.4 million were slaughtered in an all-out eradication program.

The eradication program came too late in one sense, for in time it became clear that the disease had been transmitted to human beings. Those who had eaten products from the animals fed on any of the supplement contaminated with the brain, spinal cord, or digestive tract of the dead animals were affected. The human variant of BSE was given its own name—variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD or nvCJD). By October 2009, it had killed 166 people in the United Kingdom and 44 elsewhere.

The story then turns to the laboratory of Dr. Stanley Prusiner, a neuroscience researcher at the University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine who was studying CJD. Prusiner’s research team found that the infective agent that caused both BSE and CJD was not a virus, as had been proposed, but rather a normal protein that had changed its structure. Prusiner called these altered proteins prions—a combination, sort of, of the words “protein” and “infection.” His finding proved to be a classic example of Pauling’s structure-function model of disease in action. As Prusiner demonstrated, the prions were natural proteins that had undergone a post-translational modification of their shape; the modification rendered the prion protein stable to cooking temperatures up to 600 degrees Fahrenheit and made it infective. Ironically, the shape of the infective prion protein was what is known as a beta-pleated sheet, a structure that was first defined by Pauling and Corey in their 1951 publications.

This story has an element of intrigue not totally absent from the world of science. Dr. Carleton Gajdusek was a Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 for his discovery of the origin of kuru, another incurable neurodegenerative disease, similar to CJD, that afflicted the South Fore people of New Guinea in the 1950s. Gajdusek traced the origin of the disease to the tribe’s ritual eating of the brains of elders who had died. Once this form of cannibalism was stopped, the disease did not recur.

Gajdusek had long been convinced that kuru was caused by a slow-reacting virus, but he was never able to isolate or identify it. Nevertheless, when BSE and CJD emerged in the 1980s, he was sure these were other forms of kuru, caused by the same infective virus.

Stanley Prusiner’s work of course showed something quite different—that it was not a virus but a structurally modified protein that caused all of these neurodegenerative conditions; in fact, Prusiner added scrapie, affecting sheep and goats, to the list.

The battle was on—a fight between those claiming that an infectious virus was the cause, and those supporting Prusiner’s finding that the cause was a structurally modified protein that could be transferred through ingestion. In 1997, the debate was ended when Stanley Prusiner won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of prions and their role in causing neurodegenerative diseases.

There are many lessons to be learned from this story. One is that the world of science is not free from hubris or an unwillingness to change an opinion in the face of new information. Another is that, for the most part, and even if it takes a while, the truth ultimately wins out. Perhaps the most important lesson is that structure influences function, and that structural information that defines our health and disease can be transmitted through the foods we eat.

Nature is highly selective about the information incorporated into a specific structure. The atoms in a molecule of food are arranged as they are because they constitute a particular piece of coherent information that imparts specific intelligence to the body. When this structure is changed, the information inherent in the structure is changed, and the impact on genetic expression patterns and the way the body therefore functions is also changed.

In chemistry and biology, we talk about “native structure,” by which we mean the structure that was present in the plant or animal in its normal state. Did you know that native structure may include handedness—that is, that molecules can be either right-handed or left-handed? Sugars like glucose, for instance, are left-handed, and amino acids are right-handed. If you try to feed someone a right-handed sugar or a left-handed amino acid, that individual will have trouble metabolizing the wrong-handed substance. In fact, the individual is likely to get sick. Yet many synthetically produced substances are an equal mixture of the right- and left-handed versions of a natural substance, only one hand of which is truly natural. A pharmaceutical drug prepared with both right- and left-handed versions can create an adverse effect from the “off-hand” version.

Among other things, this suggests that exceptional care should be taken in messing around with structure—because it is tantamount to messing around with the way the body functions. At the very personal level, the lesson to take away from this bit of science is that the closer to nature the stuff you consume, the more aligned it will be with the functioning of your body—and the better for you. The very rhythm of life is really orchestrated through the structure of substances we ingest. Food is indeed information.

OBESITY IS A STRUCTURAL PROBLEM

Surely one of the dominant health issues of our time is, in structural terms, the adverse health effects associated with an increased waist-to-hip ratio. It’s obesity—technically, central obesity, where the fat stores of the body are concentrated around the waist as intra-abdominal fat. It is by now well known that this type of excess fat accumulation is associated with increased incidence of such chronic illnesses as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, dementia, kidney disease, and both breast and prostate cancers. In fact, the risk of these illnesses is higher from these central fat deposits than from fat residing elsewhere in the body; clearly, this is because the central fat is in direct communication through the bloodstream with the intestinal tract and the liver. Once again, structure—something being where it is in the body—determines function.

To understand how this works—that is, how central deposits of fat so specifically pose a greater risk of chronic diseases than other types of fat—we need to know something about the “personality” of fat deposits. First of all, the cells that make up fat tissue—known as adipose tissue—are called adipocytes. For many years, medicine paid little attention to adipocytes because their only known role was to store extra calories in the form of fat. This all changed starting in the 1990s when further research demonstrated that adipocytes can manufacture and secrete into the bloodstream a family of messenger substances called adipokines. Members of the adipokine family—adiponectin, resistin, and leptin—send messages from the adipose tissue where fat is stored to the rest of the body.

Now here is where the story gets interesting. Adipocytes send two types of adipokine messages; one is friendly, the other angry. Angry messages spur the adipocytes to release particular kinds of substances. Specifically, these are substances that cause what medical students have for generations recited as the hallmarks of inflammation—rubor, calor, dolor in the Latin of medical school mnemonics: redness, swelling, and pain. That’s what you can get when your adipocytes have been exposed to something they find hostile. By contrast, when the adipocyte is in an environment where its needs are met, its genes express a friendly adipocyte message. Here’s how it works:

Suppose you eat a meal that is too high in fat and way too high in sugar. Your gastrointestinal immune system gets alarmed and sends out an alarm message to your white blood cells. They travel through the bloodstream to the adipose tissue where fat is stored, and there they express their anger to the adipocyte. The adipocyte in turn activates its genes to express the angry adipokines, which then race around the body influencing the heart, arteries, liver, brain, kidneys, and pancreas—where, of course, insulin is produced. The adipocytes are basically saying, “I’m fed up and I am not going to take it anymore, and I am sending out adipokines to let everybody know just how angry I am.”

And since the original alarm message that ignites this expression of angry fat is received in the immune system of the gastrointestinal tract, most angry fat is found in the nearby central regions of the body. It’s the area that gets the first and biggest “hit” from the angry adipokines. For this reason, the greatest risk of chronic illnesses associated with fat accumulation comes from the abdominal fat we see as an out-of-balance waist-to-hip ratio.

But if increased body fat shows risk of chronic illness, it isn’t in and of itself a cause of chronic illness; what causes the illness is how angry the fat is. That is why there are plenty of people with significant amounts of excess fat and no chronic illnesses, whereas many leaner folks may suffer type 2 diabetes, heart disease, or any of the other conditions associated with obesity. It is not being fat that causes disease; it’s the structure of the fat and its resulting function.

THE CALORIE FALLACY

We have long been told that people become obese because they take in too many calories and don’t get enough exercise. This is a very simple expression of the first law of thermodynamics, which states that energy is conserved. So however much energy we take in, measured as calories, that’s how much we must use up in activity or we will conserve the unused difference—that is, store it—as fat.

It all sounds so reasonable. But this is neither a complete explanation of nor any kind of answer to the growing global epidemic of obesity. People are not engines that burn fuel; rather, we are complex physiological beings that regulate energy flow and utilization in very sensitive, intricate ways. We saw in Chapter 9, for example, how subtle are the processes of bioenergetics that keep our energy flowing and control its use.

Have you ever noticed that people who carry extra stored calories as fat are often the hungriest people around? And that they often behave as if they have no energy? Why would this be the case when it seems they have more than enough stored energy to meet their needs? I call it “switched metabolism.” It is as if the bodies of these people don’t recognize how much stored energy they have in their adipose tissue; therefore their bodies demand more quick energy to meet their needs. This turns on the hunger mechanism, which in turn results in more calories stored as fat, and around and around the obesity spiral the person winds.

What causes this? What switches the metabolism? Breakthrough research has finally provided an answer to this question—and it’s all about an individual’s structure and function. So dismiss, please, the notion that an individual inherits obesity genes. Although we do find that obesity runs in families, no gene that causes it has ever been found; I predict none will ever be found. Rather, what we’ve learned is that there are many hundreds of genes that regulate the physiological processes that control bioenergetics and its connection to appetite, fat storage, and metabolism.

First, we know that hormones can influence where and how fat is deposited. Higher levels of the estrogen hormone and of the stress hormone cortisol direct fat deposits to the abdominal area. That means that allostatic load, discussed back in Chapter 7, is connected to obesity.

Second, we know that toxic chemicals can poison mitochondria and direct calories to be stored in adipose tissue for a rainy—that is, food-starved—day that never comes. That sounds like our processes of detoxification and defense may be connected to obesity, and in fact, there has been and continues to be a prodigious amount of research in this area.

The story starts in 2005 with a series of papers, now numbering more than a hundred, by two professors working together but some six thousand miles apart. Dr. David Jacobs, professor of public health at the University of Minnesota, and Dr. Duk-Hee Lee, professor of preventive medicine at South Korea’s Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, set out to explore the relationship between the level of persistent organic pollutants in the body and obesity and type 2 diabetes. We actually encountered these persistent organic pollutants, POPs, back in Chapter 5 in our discussion of bisphenol-A, BPA, the persistent chemical that simply resists breakdown by any known process. Since such POPs are at large in the environment, they often enter our bodies. Jacobs and Lee wanted to know if there was a statistical correlation between POPs, obesity, and the chronic illness type 2 diabetes.

To find out, they consulted the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a comprehensive set of surveys initiated in the early 1960s by the Centers for Disease Control. Aimed at nothing less than assessing the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States, the survey is unique in combining interviews with physical examinations. In 1999, NHANES became an ongoing program that examines a nationally representative sample of some 5,000 people in fifteen counties across the country each year. Demographic, socioeconomic, dietary, and health-related measures are tracked along with medical, dental, and physiological measurements. The compiled data offer a comprehensive picture of the nation’s health and nutrition and represent a treasure trove of information scientists and the public can access.

On first analyzing the NHANES data, Jacobs and Lee were amazed to find that, contrary to common belief, there was not a strong correlation between obesity and type 2 diabetes—unless the individual also showed a slightly elevated blood level of the enzyme gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, GGTP. It is a biomarker that has historically signaled liver injury due to alcohol or drug toxicity. For a modest elevation of GGTP level to indicate a relationship between obesity and diabetes in people with neither an alcohol nor a drug problem was unusual in the extreme.

It prompted Jacobs and Lee to search for a connection among the three factors. It was a bit mystifying. They knew that a major function of GGTP in the body is to produce glutathione. Glutathione, as we saw in Chapter 9, protects the mitochondria against injury from caustic forms of oxygen and, as we saw in Chapter 5, is a key component in the detoxification of chemicals. Jacobs and Lee wondered if perhaps the slight increase in GGTP could be a result of exposure to chemicals that the body was trying to detoxify by increasing the production of glutathione.

To check this hypothesis, they examined the level of a number of POPs in the blood of obese people, dividing them into those who had type 2 diabetes and those who did not. The stunning results of this analysis constituted a seismic event in the field of chronic illness research. The results showed a much higher level of POPs and of GGTP levels in the obese people with type 2 diabetes than in those who were obese but did not have diabetes. This suggested that the POPs had something to do with the origin of diabetes, but it also raised the question as to whether accumulation of POPs might also have some causal relationship with the obesity epidemic.

The two extended their studies to other countries—notably Korea, where obesity and diabetes are rapidly rising—and found the same correlations. The two men now believed they had unlocked a major new understanding of the role of the environment on structure and therefore on function.

Research groups around the world have doubled down on the analyses by Jacobs and Lee and have confirmed their hypothesis. The connection between POPs and obesity is official—official enough to have been given a name: obesogen, a substance that can create obesity.

Let me recap this, because it is essential—not just for understanding our own bodies, but also in providing a clue to the obesity epidemic in which our country and, increasingly, the rest of the developed and developing worlds are now mired.

Obesity is not solely a matter of excess calories. It is a consequence of too many of the wrong type of calories in the presence of an accumulation of environmental POPs. Add it up:

• Bad information from the food we eat creates angry fat.

• POPs poison our mitochondria, reducing their ability to process food into energy, increasing their production of caustic forms of oxygen, and directing unprocessed food calories into storage in fat cells.

• This leads to a change in our structure resulting in a change in the way our physiology functions.

Perhaps a more apt image is that of a vicious circle: We eat foods that cause angry fat, enabling POPs to accumulate in our fat tissue, making it angrier, reducing the bioenergetic capability of our mitochondria, leading to further fat storage—and spinning the circle into chronic illnesses like type 2 diabetes, now on track to become a global pandemic.

BISPHENOL-A AND THE STRUCTURE-FUNCTION RELATIONSHIP

BPA reenters the story in a major way at this point. We explained back in Chapter 5 how this synthetic compound, the plasticizer used globally in bottles and other containers for all kinds of liquids, dislodges naturally occurring hormones from their receptors and sends its own messages to cells regulating physiological function. It is important to note that the levels of BPA in the environment are very low, so low in fact that it was assumed for years that BPA could not possibly have any impact on human physiology.

That assumption was woefully wrong. In 2012, a landmark paper published in JAMA reported on research by pediatrics investigators at the New York University School of Medicine. A cross-sectional study of children and adolescents had revealed that levels of BPA in the urine of the study subjects were associated to a significant extent with obesity. In the same year, a study in China reported the same association between BPA levels in children and obesity. Obviously, these studies support the Jacobs and Lee finding of the relationship of POPs to obesity. They make it clear that BPA is an obesogen and a risk factor for such chronic illnesses as diabetes and heart disease, among others.

To me, this raises the question that Rachel Carson posed in Silent Spring—namely, how low a level of a substance known to influence human health will produce no effect? What the BPA story tells us is that the answer to this question depends upon the nature of the effect you are looking at. The hormetic effects on structure and function that occur from very low levels of exposure may produce outcomes that are not obvious and that take years to develop.

The studies on BPA in children tell us that obesogens like BPA put epigenetic marks in our book of life and alter the way that genes are expressed. What is even more troubling is to find that some of these epigenetic marks are placed on our genome in germ cells, the cells that can reproduce sexually—that is, eggs in women and sperm in men—and can thus be passed on to subsequent generations. This opens the real possibility that the exposure to a low level of a specific obesogen can alter the genomic expression patterns of the next generation such that the structure and therefore function of that generation’s physiology are altered.

The implications are far-reaching. There are obesogens in our environment, and their association with chronic diseases associated with obesity is now much more than a theory. I believe we are looking at a revolutionary new reality about factors that contribute to changing physiological structure and function in people around the world whose societies are undergoing profound change. Have you ever looked at photographs of people from a century ago? Is it possible that the differences in body structure we see between then and now are simply a matter of changing fashions? Surely not. The change is more fundamental.

One of the most fascinating perspectives on this is in the 1939 book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration by Weston Price, a dentist living in Baltimore at the turn of the last century. Weston and his wife traveled extensively throughout the world over a period of some thirty years. This was at a time—the first quarter of the twentieth century—when many of the peoples they visited in their travels were just undergoing the transition from their indigenous lifestyles and diets to those of an increasingly industrialized society. Price photographed the same families several different times over the thirty years, and he documented changes in the appearance and health of the children, noting particularly the significant alterations that occurred once white flour and sugar had been incorporated into their diets and in the wake of lifestyle habits made “easier” through advancing technologies. Price has been called the Charles Darwin of nutrition for his detailed recording of these observed changes that so tellingly embody how change in structure results in change in function, and his book, considered a classic, is still available.

Whatever Price’s particular observations and whatever his conjectures and conclusions, the question his book raises is an important one. When we consider that in today’s children eyesight is declining, dental appliances are increasingly needed to correct tooth alignment, obesity is on the rise, and allergies, asthma, and eczema are all spiraling upward, it’s worth pondering whether or not such “developments” aren’t the results of epigenetic changes caused by factors of environment, diet, and lifestyle. And it’s worth considering what we can do about it.

BROWN FAT, BEIGE FAT, AND OBESOGENS

Obesogens interact with all sorts of different cells in our body in all sorts of different ways, but one of the most important interactions is with the heat-producing cells known as brown fat. There are two types of fat cells—white and brown. White adipocytes store fat; brown adipocytes create heat energy. The brown color comes from the fact that the mitochondria in these cells contain so much iron; it’s found in the cytochromes, compounds inside the mitochondrial membrane that are involved in the energy and detoxification processes. (White adipocytes, by contrast, have a different function, storing fat, and therefore a different structure comprising far fewer iron-containing cytochromes.) Thanks to the heat energy that brown fat cells produce, the body can maintain a constant internal temperature even when the external temperature is very low.

Not surprisingly, hibernating animals like bears have high levels of brown fat cells, giving them enough conserved heat energy to get through their dormant period. Infants also have fairly high levels of brown fat. Until recently it was thought that those infant brown fat cells were lost in adulthood, but advanced diagnostic techniques have now identified active brown fat around the neck, shoulders, and upper back of adults.

Obesogens poison brown fat activity, with all sorts of consequences having to do with the production and conservation of heat energy. One consequence is simply that an individual will become increasingly sensitive to cold. Another is obesity: poisoned brown adipocytes may no longer be able to convert a calorie of food into heat, so that calorie will likely be stored as fat in white adipocytes. A sedentary lifestyle is another cause of decreased brown adipocyte activity—it makes them lazy so that they do not convert food to heat very well. It’s yet another good reason, if one were needed, for regular exercise. Certain ingredients in food also diminish brown adipocyte activity. One of the most powerful in doing so, and therefore one of the worst offenders when it comes to obesity, is high-fructose corn sweeteners found in many processed foods and beverages.

But just as there are foods that make brown adipocytes lazy, there are also many that wake them up, increase their activity, and therefore help prevent or reverse obesity. Among these are cayenne peppers and other members of the capsicum family of vegetables, apples and peanuts with their skins, grapes, berries, green tea, cinnamon, virgin olive oil, isohumulones from hops, omega-3 fatty oils from fish, and calcium-rich foods like low-fat yogurt.

One of the most exciting new discoveries in this field is the 2008 discovery of beige fat by a professor of cell biology at Harvard, Dr. Bruce Spiegelman.* Spiegelman found the beige adipocytes, as he termed them, embedded in white fat, and he determined that they could be coaxed into becoming heat-producing, active adipocytes through exercise and changes in diet. In other words, activating beige adipocytes can turn angry fat into healthy fat. As you might expect, that in turn has positive effects on insulin sensitivity and lowers the risk of type 2 diabetes and other chronic illnesses.

What does it mean? Simply this: that a couch potato scarfing down supersized portions of junk food who transforms himself into a regular exerciser consuming unprocessed foods rich in phytonutrients will achieve something beyond a sharp reduction in body weight; he can actually create a new, lower set point—that is, the weight at which his body feels natural, and the weight at which it tends to remain.

Such a transformation represents a change in structure and a resulting change in function with long-term positive effects on health. Contrast this with the fad-diet approaches that produce the yo-yo effect—a counterfeit weight loss from which the dieter almost always rebounds, often back to an even higher weight.

THE CONNECTION OF THE SKELETON TO BROWN FAT

And so our story of structure circles back to the skeleton—the first thing that typically comes to mind when we talk about the body’s structure. After all, it is the skeleton that keeps our structure upright against the force of gravity and allows us to be mobile and active. That’s how I thought of the skeleton when I first began my training years ago; in those days, we had a “real” skeleton hanging in the classroom, and to me, it was a scaffold onto which the body and its parts got attached. I was so wrong.

The human skeleton is the quintessence of getting the structure right and letting the function follow. Of course, the skeleton is bone, but bone consists of the marrow within the mineralized portions of bone, some cortical or compact portions, and some trabecular or meshlike, spongy portions. All are active components that replace themselves throughout our lifetime.

The marrow is where the red and white blood cells in our body are born. Without a healthy bone marrow, we would suffer serious forms of anemia and immune deficiencies. The cortical and trabecular bone, composed of the structural protein called hydroxyapatite, a form of calcium, provides the strength of the skeleton. It also produces signaling substances that talk to other organs in the body, and the other organs in the body produce substances that talk back to the bone. It’s a reminder that the skeleton is a part of one of seven core physiological processes, all interconnected, all controlled by genes communicating with one another and with the external environment.

So you will not be surprised to learn that beige adipocytes produce signaling substances that talk to the skeleton in such a way as to improve bone health. For openers, this means that any alteration in the structure and function of fat cells can have an effect on the structure and function of bone. But that’s only for openers. Listen in on a conversation, and you’ll see what I mean.

The conversation starts when healthy beige adipocytes release a signal called bone morphogenic protein, or BMP, to the bone cells. In response, the bone cells produce signaling substances called osteocalcin and osteoprotegerin that influence insulin activity and blood sugar levels. From brown fat to bone to the insulin-secreting pancreas to the control of blood sugar, the progression is clear: A healthy skeletal structure results in healthy function that can reduce the risk of many chronic diseases.

Another potent example of this is what happens when the skeletal structure is unhealthy—as in the chronic disease known as osteoporosis, characterized by bone loss that increases the incidence of fracture in the wrist, hip, and spine. It is a condition seen all too often in postmenopausal women whose ovaries no longer produce the hormone estrogen, which protects the skeleton, but it is seen in men as well.

Medical thinking about osteoporosis saw it not only as the consequence of estrogen loss, but also as stemming from not enough calcium and vitamin D in the diet and not enough weight-bearing exercise by the individual. This is in part true, but there is more to the story. We have now learned that ill health in the bone is influenced by inflammatory signals from other parts of the body—just like angry fat and arthritis. Indeed, there is a strong connection between osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and heart disease. If you have one of these chronic illnesses, you are likely to have the others—for the simple reason that they all share common disturbances of the core physiological processes. It is why functional medicine focuses less on the diagnosis of these individual diseases and more on managing the core physiological imbalances and interconnections that have brought them about.

In fact, our research group at the Functional Medicine Clinical Research Center in 2009 joined with Dr. Michael Holick, a research endocrinologist at Boston University School of Medicine, in a clinical intervention trial that put a group of postmenopausal women on a fourteen-week Mediterranean-style, low-glycemic-load diet enhanced with selective phytonutrient supplements. The results showed two things: first, significant improvement in the biomarkers associated with healthy bone versus women of the same age on a standard diet with no phytonutrient supplement; second, lowered inflammation and improved cardiovascular risk factors in the women on the plan. Interconnections indeed.

Have you heard of denosumab—the brand name is Prolia—a fairly recent drug for the treatment of osteoporosis? It works by blocking the inflammatory signal in bone, thereby preventing bone loss. Clearly, it is based on the understanding that bone inflammation is connected to inflammation in other parts of the body, so it is not surprising that the developer of denosumab is exploring this same drug for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic diseases associated with inflammation.

What we are witnessing in medicine are the practical applications of Pauling’s revolutionary thinking about structure and its relationship to function derived from his molecular medicine model. As researchers and practitioners increasingly see the ways in which genetic expression is influenced by specific factors of environment, lifestyle, and diet, these applications will continue to expand—and health will improve.

Deborah and Bruce, as I’ll call them, are a charming and engaging couple in their early seventies who were referred to our medical and nutritional professionals because they wondered if a change in diet might offer some solution to Bruce’s increasing frailty and immobility. A review of Bruce’s history, physical evaluation, biomarkers, and functional assessment led to the collective conclusion that he was suffering from sarcopenia, the medical term for loss of muscle mass, which seemed to be due to an underlying chronic inflammatory condition. Bruce showed no signs, however, of a traditional autoimmune disease like arthritis; rather, metabolic factors were contributing to the inflammation. We also gave Bruce a bone density test and found results in the range of an osteoporotic female.

No wonder he felt frail and found it difficult to move. The loss of muscle mass with age is a major contributor to disability and injuries and certainly compromises an individual’s strength. Because it happens over time and in increments, it is often not recognized, and of course it is typically thought to be “just a part of aging.” This acceptance of loss of muscle mass as inevitable is a principal reason that we see increasing numbers of older adults holding on to a walker or a cane as they try to get around, or using a motorized device. But the truth is that sarcopenia is now recognized as resulting from a number of factors—chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, lack of weight-bearing exercise, and nutritional imbalances.

In Bruce’s case, a personalized program was designed that would improve his insulin sensitivity, reduce his inflammation potential, and increase his anabolic hormone activity to rebuild lost muscle. The program included daily strength and conditioning exercises; a diet focused on higher protein content, a lower glycemic load, and of course specific phytonutrients; a prescription for low-dose testosterone replacement therapy; and a nutritional supplement program to close the gap of Bruce’s nutritional needs.

We like to give a personalized lifestyle plan at least twelve weeks to work. Everybody is different, of course, but in my view, it takes at least that amount of time to substantially change the structure-function relationship in a person with chronic health problems. Moreover, progress may be slow to start, and not seeing the improvement you hope for in the first days or weeks can be frustrating. If you expect the payoff to take three months, that can often encourage people to stick it out.

That’s what happened with Bruce. There was little visible progress in the first few weeks; indeed, it wasn’t until week nine that the improvements really accelerated. Yet even when the signs were minimal, Bruce told us he found the experience far more profound than he had ever expected. He felt “empowered,” he said, for the first time in his life to take control of his own health, and he was glad to wait the full twelve weeks to know he could be successful at it.

Successful he certainly was. He left his walker behind and became fully mobile without assistance. Our follow-up studies showed increased muscle mass without a significant spike in body weight; in other words, he had replaced fat with muscle. His bone density was showing improvement, as were the biomarkers of inflammation. Most important, he felt “more vital.”

There was another benefit as well. Deborah also lost weight during the twelve weeks, and in her regular checkup, her own doctor commented on a number of improved indicators. In fact, her bone density test had so improved that he said there was no need prescribe a bone loss drug. “Whatever you’re doing,” he told her, “keep it up.”

The Deborah-Bruce twofer tells us something else about health and well-being—namely, that the structure of our social relationships can also determine how our lives function. Pauling’s structure-function model plays out at every level. That is perhaps reflected in the two Nobel Prizes in his own life—one for how structure at the molecular level affects our health, the other, the Peace prize for his global effort to stop atmospheric nuclear weapon testing, at the interplanetary level. In both spheres, what we do to structure can influence how we function.

It is time to put this to work on the personal level. Yours.

CHAPTER 10 TAKEAWAY

1. The structure of the body is related to its function, and nutrition and physical activity play key roles in determining both.

2. Proper structural alignment is important for maintaining good health.

3. Exposure to electromagnetic radiation can result in changes in immune and nervous system function.

4. Elevated blood sugar levels result in the production of glycoproteins that can contribute to many chronic diseases. A low-glycemic-load diet comprising minimally processed foods prevents this problem.

5. Obesity is caused by more than just too many calories; it is also a result of consuming foods that increase inflammation in the body.

6. Exposure to toxins in food and water contributes to obesity.

7. Bone loss can result from such factors as poor nutrition, lack of weight-bearing exercise, digestive problems, inflammation, and insulin resistance.