WE LIVE IN an age transformed by the power of social media and technology: there have never been more ways to communicate, so quickly and efficiently. Thankfully, we also benefit from unprecedented openness – we can freely share our innermost thoughts, feelings and challenges if we want to – not just with our friends and family but also with complete strangers. We have seen this with many issues that have been previously stigmatised, including mental health and sexuality. We’re seeing the start of a similar revolution on menstruation but there’s still a way to go. So, why do we still shy away from ‘female things’? Is there still an unspoken ‘otherness’ about being a woman, despite 49.5 per cent of the world’s population being female? Unfortunately, for one in 10 women, who have this very misunderstood, poorly explained disease, endometriosis, the social movement has only just begun – and it couldn’t have come a moment too soon. But what exactly is endometriosis?

It was like opening a door into another world that I had no clue how to navigate, who to talk to, how to get support, or get myself better. – Zoe

Endometriosis – or ‘endo’, as women with the condition often come to call it – is commonly considered to be a gynaecological disease, or a disease of the female pelvic organs. But on another level, it is also a system-wide hormonal disease that strikes right at the cellular level, because endometriosis occurs when cells that act like those that line the womb (uterus) are found elsewhere, usually in the pelvis, in places where they are extremely unwelcome: on the lining of the peritoneal wall (the inside lining of the abdomen and pelvis), in the ovaries, in the vagina, on or even in the bowel or bladder, and sometimes, rarely, in far-flung corners of the body, such as the diaphragm, the covering of the heart (pericardium), the lungs (causing a cyclical cough, or cyclical coughing up of blood), in abdominal scars, including the navel, or belly button. In exceptionally rare cases, it has even been known to present in men.

So what happens then? Well, we know that endometriosis is a disease that grows in response to hormones – principally oestrogen – coming from the ovaries. Oestrogen is the hormone that causes your womb lining to thicken each month. The endometriosis tissue responds to the body’s oestrogen and likely bleeds ‘internally’ with no place to go. Over time, this monthly internal bleeding can lead to inflammation and scarring – referred to as ‘adhesions’ – that can cause surfaces within the pelvis to stick together. The misplaced endometriosis tissue may develop its own blood supply to help it grow, and a nerve supply to communicate with the brain, which is one possible reason why some women with endometriosis may suffer from such debilitating pain. But women with endometriosis can also suffer from a wide range of other symptoms and issues, such as a range of digestive symptoms (constipation, diarrhoea, nausea and IBS type symptoms), painful sex, subfertility, pelvic pain either persistently throughout the month or at certain times, and fatigue. Strangely, not every woman with endometriosis gets pain but many of them do – and we could write a book alone on the pain associated with endometriosis. When thinking about the symptoms of endometriosis, it can be helpful to look at where all the organs are located in a woman’s pelvis. There’s a useful illustration of this at the start of this book (see page xxi).

Theories abound as to why women get endometriosis and what causes it – the truth is we do not know conclusively, as yet, why some women get it. But we can describe some of the characteristics of it that will help us to understand it a little better.

Above all, we know that you are more likely to have endometriosis if you have a relative with it. But, in truth, the genetics of endometriosis is complex and remains unexplained. Most researchers feel that endometriosis is inherited by what is termed as ‘a polygenic/multifactorial mode’, which means that it is caused by a combination of genes and the environment. Yet there are a number of factors that specifically make it difficult to determine the exact ‘mode’ of inheritance of endometriosis.

First and foremost is the fact that endometriosis can only be diagnosed invasively by surgery. This can result in under-reporting of patients with the disease since the diagnosis relies on an invasive test.

Another issue is that endometriosis may not actually be one disease but a number of similar diseases that are currently grouped together under the definition of ‘endometriosis’, as evidenced by the different sites in the body where it can be found. So there is, as yet, no ‘genetic’ test for endometriosis. Many of the women we spoke to talked of their own mum’s sufferings, or that of other family members who perhaps never realised they had endometriosis.

I think my mum definitely had endo but she wasn’t diagnosed. Her sister did have endo and was luckily diagnosed. – Lucy

Putting genetic factors aside, another widely accepted and supported explanation for why women develop endometriosis is ‘Sampson’s theory’, first put forward in the 1920s by gynaecologist Dr John Sampson, that suggests it occurs due to ‘retrograde menstruation’. This is where some of the blood and cells that are shed from the womb lining during a period pass backwards up through the Fallopian tubes into the pelvis and stick to the pelvic cavity wall instead of leaving the womb through the vagina as part of the monthly period. Yet we know that nearly 90 per cent of women experience retrograde menstruation and most women with retrograde menstruation do not end up with endometriosis. Because of this, studies to date have focused on differences in the womb lining of women with endometriosis and researchers are now investigating whether the pelvic wall lining (peritoneum) plays a role in the establishment of the condition, or whether it is altered in women with endometriosis.

We also know from research that endometriosis cells have been found in the foetus, which supports the theory that the disease process is laid down in some women from the start of their lives. The lining of the womb in a newborn baby can show signs of activity immediately after birth and, in some cases, show changes similar to those seen at menstruation in women. So, the womb in a newborn baby is capable of shedding its lining, yes, ‘menstruating’. Indeed, visible vaginal bleeding occurs in one in 20 newborn female babies. And what’s fascinating is that endometriosis has been seen in a newborn baby – possibly due to plugging of the womb at the level of the cervix, the womb outlet – leading to a backward, or retrograde, flux of the blood and cells contained in menstrual debris. These findings are causing researchers to speculate that endometriosis, especially in children and young adolescents, could originate from retrograde bleeding soon after birth.

Some researchers think that endometriosis could be an immune system problem or that a local hormonal imbalance enables the endometrial-like tissue to take root and grow after it is pushed out of the uterus. Others believe that in some women, certain pelvic wall or abdominal cells mistakenly turn into endometrial cells (metaplasia). These same cells are the ones responsible for the growth of a woman’s reproductive organs in the embryonic stage. It’s believed that something in the woman’s genetic makeup, or something she’s exposed to in the environment later in life, changes those cells so that they turn into endometrial tissue outside the uterus. There’s also some thinking that damage to cells that line the pelvis from a previous infection can lead to endometriosis.

Despite these theories we still have unanswered questions, questions that research still needs to answer. Most experts agree that there are many factors that may all have a role in the development of endometriosis, including genetic factors, retrograde menstruation, metaplasia, immunological and hormonal reasons.

We’ve looked at what endometriosis is and some of the theories about why women get it, let’s now take a look at one of the challenges of this disease: getting a diagnosis.

Most young women have some pain and discomfort, leading up to, during and after their period. This is normal, and most girls get told that their periods will calm down in a couple of years as hormone levels become more settled; for most girls they will. But ‘period pain’ should not be so bad that you cannot get up, go to school, college or work, or carry on with your normal life. If your pain is interfering with everyday activities, at any age, it is not normal.

The taboo that requires a woman’s common bodily functions to remain largely unspoken of, is a stumbling block when it comes to diagnosing and treating endometriosis. But let’s start at the very first challenge facing women – and probably the most fundamental issue for endometriosis – the notion that period pain is ‘normal’. How can people know and distinguish between ‘normal pain’ and pain that is a problem, pain that might indicate disease may be present? How do we know what is ‘normal?’

Let’s call this first stage ‘the unknown unknown’: quite simply, we just don’t know what we don’t know. For many with endometriosis, the first stumbling block is this: that the perception of women’s pain is quite clearly embedded in our society and that starts with education at home, often by other women, so, unfortunately for some teenagers, their ‘norm’ was also their mother’s or their grandmother’s pain. Amy explains: ‘I was in one of those families where my mum and my nan said, “It was really bad for us as well, we’re just unlucky as a family.”’

How deeply ironic for a disease that has a hereditary component that the pain and disease of some mothers and grandmothers – who very sadly may have had the disease and not even have known it – should be one of the reasons why women may delay seeking help for pain.

If we expect women to be in pain, how do we break that down? How do we dispel the myth that pain is inseparable from having a period, and secondly, how do we help people to understand the important – and early – indicators of this common disease, endometriosis? Perhaps a good place to start would be in health education in schools, but even there, as Preena explains, there is no mention of common diseases that affect periods, such as endometriosis. ‘I had no idea about any of these things when I was young, and I think many young girls suffer from it but unfortunately they’re not told about it, either at school or university.’

So, let’s move to stage two, the ‘known unknown’: you’re becoming aware that there is a problem, but have absolutely no idea what’s wrong, you just know things are definitely not ‘normal’ with your periods. Perhaps over-the-counter pain relief isn’t enough to help manage your symptoms and maybe you have even already been to see your GP. At this stage, your symptoms may cause you to take time off work, or to miss school.

Whatever it is, when we asked women to talk us through their journeys with endometriosis, many of them started by talking about the challenges they faced early on as a teenager, even if they weren’t diagnosed with endometriosis until many years later.

Endometriosis symptoms may be experienced at any age, ranging from when a girl reaches puberty to menopause. However, it can be especially difficult for those who suffer significantly when they are still at school, and unfortunately a myth persists that teenagers don’t get endometriosis. Sophie’s friend would take her to the medical room when she had her period as the pain she experienced made her vomit ‘It was very embarrassing, because every time my friend would go back to the classroom, the teacher would ask what was wrong and my friend would say, “oh it’s tummy pains again”, and all the pupils would laugh and think I was really weak and not coping with period pains.’

Beth experienced a lot of fatigue. ‘Everyone thought I was lazy because I missed quite a lot of school every month. They would get my mum in and said I wouldn’t pass my exams, and this is coming from an A-star student. So there was an obvious disconnect with how people saw me and how tired I was feeling, from doctors, teachers, the school nurse, everyone.’

How bizarre is it that we do not routinely talk to young women about knowing what may not be ‘normal’ and the symptoms of endometriosis? In most countries, there is still limited education about menstrual health, what’s normal and what is not, and the subject of endometriosis is barely touched upon, if it is raised at all. And even worse – how awful is it that we potentially leave women to suffer for years and years as a result?

During this stage – which could last a few months or for many years – women are on their way to getting help, even if this is frustratingly slow sometimes. They’re seeing doctors, sometimes quite a few of them. This part of the ‘known unknown’ is very tricky – they’re entering a world of knowledge and possibility but there is often stark inconsistency of diagnoses and advice. Of course, no two women with endometriosis are the same and there is a vast range of symptoms, but there are two very key people in this stage: the GP and the gynaecologist. We’ll take a detailed look at their roles in Chapter 3, The right care in the right place for you.

Let’s get back to the actual disease itself, because the symptoms of it are a whole story in themselves, and one of the reasons why endometriosis can be so hard to identify. The long diagnosis time for endometriosis isn’t just about the lack of information for teenage girls. When it comes to symptoms and subsequent tests, we’re entering an even more challenging arena where women and clinicians need to work together to find answers.

For a start, we know the symptoms may or may not correlate to the severity of disease. Rather confusingly, ‘superficial’, ‘mild’, ‘peritoneal’ or ‘stage 1’ disease, which may involve a few spots of endometriosis in one or two areas, or spread across the inside of the pelvis, may cause persistently disabling symptoms, whilst some women with deep or severe disease may not necessarily experience symptoms that are as debilitating.

We know this conundrum and all we can do is face it and be honest. There is simply no pattern or explanation as to why symptoms are so variable and also why there are so many different symptoms. We should also note that some of these symptoms overlap with many other diseases, some of which women with endometriosis may also have, which rather complicates the situation.

If there is one thing that has frustrated women with this disease, it is probably this alone: that it may have taken an inordinate amount of time for unpleasant, sometimes disabling symptoms to be pinned down to a cause, and perhaps even to be taken seriously. Unfortunately, a large number of women are told a whole bunch of things that turn out, with hindsight, to be not quite right – on top of this, a huge number of tests may be endured and a lot of doctors may be seen along the way. Sadly, this can have a significant emotional impact. But let’s take a closer look at the symptoms first.

Pain can be very hard to describe or even for others to understand, particularly when it relates to the inside of our bodies. For many women, endometriosis involves some level of pain, but this is certainly not the case for all women. However, for many women, pain is what defines endometriosis for them. Some women are in pain for a very long time before they seek help, whereas others seek help much quicker.

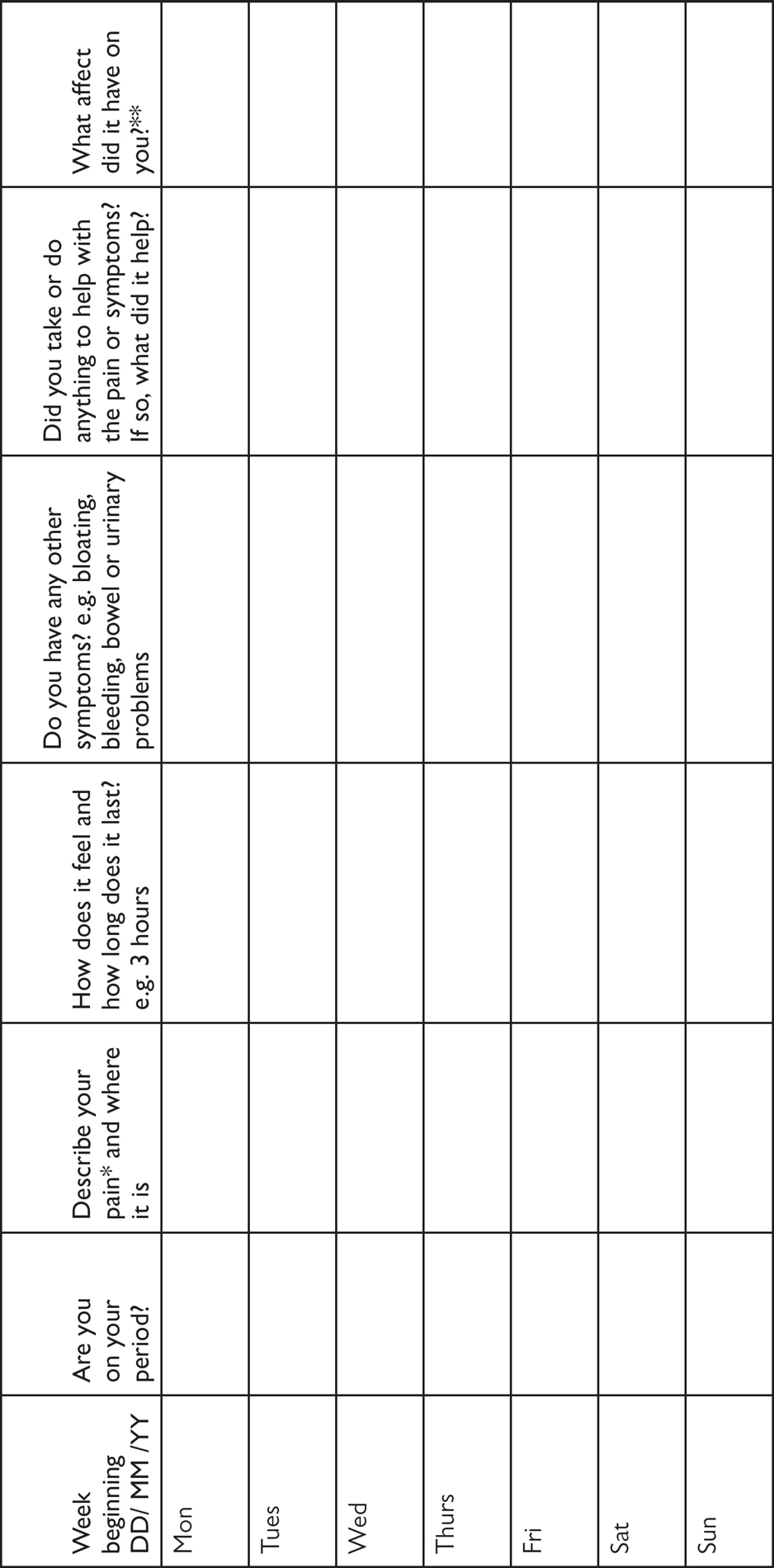

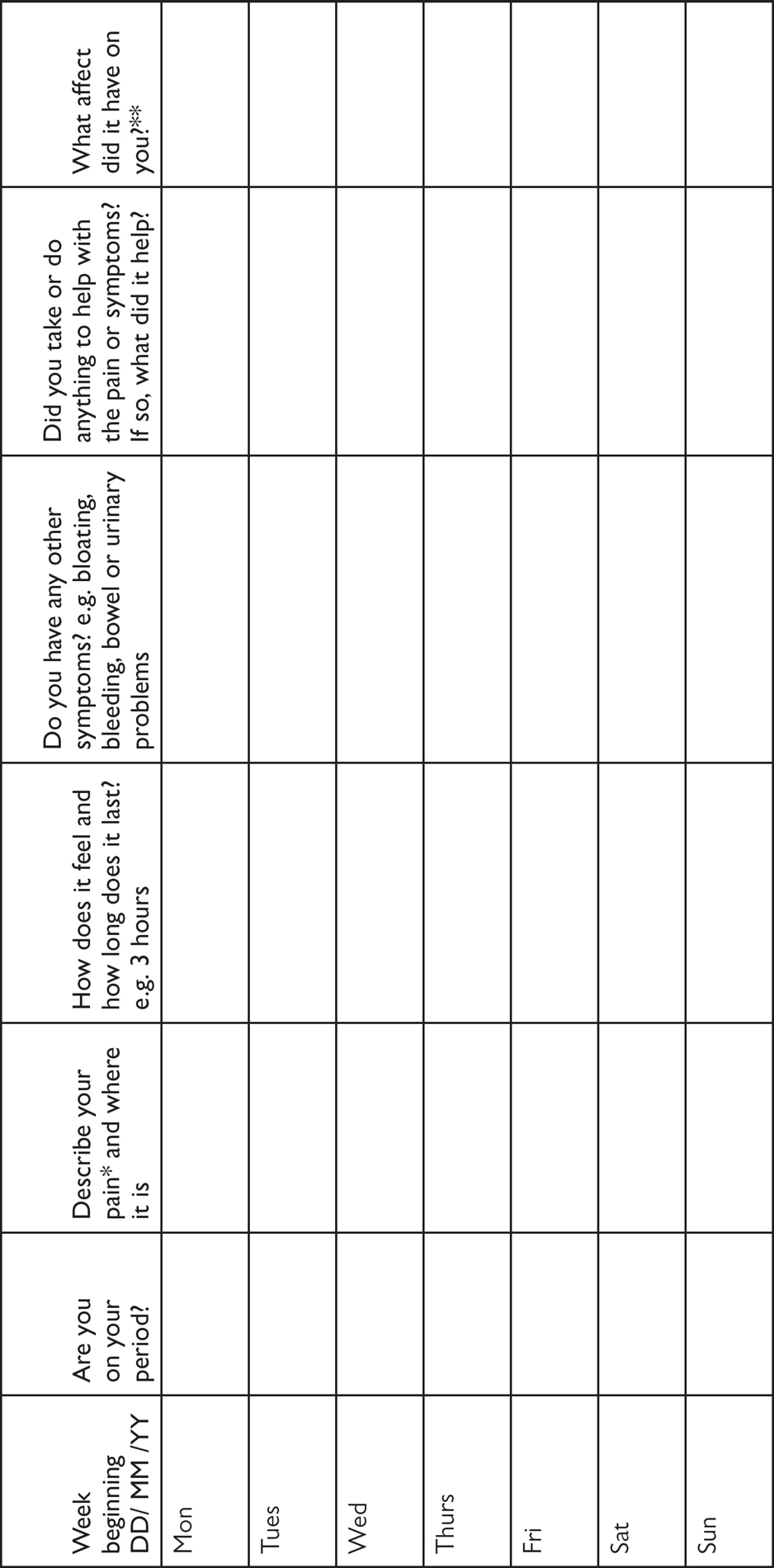

Women’s pain may be constant, or cyclical, occurring each month during the same part of the menstrual cycle. This latter can be hard to monitor – unless actively pursuing pregnancy, women don’t go around thinking, oh, I must be ovulating now … so many women just think of it as ‘intermittent’. Keeping a pain and symptoms diary (see here) to record what your symptoms are, when they occur and how they affect you, will help identify if there is any pattern to your pain. In either case, if the pain lasts over six months, it is referred to as chronic pain.

The women that we spoke to had lots of descriptions for their pain. Some only experienced pain during their periods, some at other specific times of the month, whereas others had pain throughout the month.

Zoe paints a picture of her pain: ‘It’s either an aching, dragging, heavy feeling from the waist down, or it’s intensely sharp, stabbing. It feels like everything is going to fall out of you.’ The feeling that everything is going to fall out is a description that quite a few women used.

If you have painful symptoms, how can you help others, and particularly healthcare practitioners, to understand this pain? First of all, it can help to explain how it affects your day-to-day life.

Part of describing the pain is explaining the effect of it – and this is key, because pain that causes girls to miss school or work indicates there may be an issue. Preena explains: ‘I would have to miss days off school. The pain wasn’t normal pain that my mum used to experience, this was fold-over on the bed in agony pain, taking the strongest ibuprofen possible.’

Pain that doesn’t respond to over-the-counter painkillers from your pharmacist is an indication that you need to seek help from your doctor. And pain that affects everyday activities, such as sleeping, eating and sitting, should also be a strong indicator to seek medical attention. Madison describes this sort of pain: ‘I couldn’t concentrate, I didn’t want to eat, I couldn’t sleep for the pain, there was no position, sitting, lying, that was comfortable at all.’

Pain sometimes has a knock-on impact and causes other symptoms, such as fainting, nausea and vomiting. Madison goes on to explain, ‘the pain was so excruciating that it was almost like my body just shut down, I would pass out to deal with it and that was a recurring issue for quite a few years.’

Some women that we talked to had pain right from when their periods started, maybe even before. Generally, teenage girls experiencing pelvic pain see their GP, who may prescribe analgesia or perhaps the oral contraceptive pill. And then it may be years, sometimes more than 10 years, before a woman for whatever reason decides to come off the pill and then, out of the blue, she’s again hit with terrible pain.

Not every woman is in pain for years though. Emily’s pain came on very quickly and severely, as she relates ‘I couldn’t lift a kettle with my right hand, I couldn’t drive, massive, massive pain. Of course, I’d no idea what it was, it was really horrible, so the doctor asked lots of questions, sort of leaned on my stomach – I screamed in pain.’

We don’t know exactly why endometriosis lesions cause pain, but they do ‘bleed’ and result in scarring and inflammation and seem to form their own nerve and blood supply, which may explain this. The women we spoke to told us that they were given a variety of reasons for the pain they were experiencing before they were diagnosed with endometriosis. These include being told ‘it will settle down’, ‘it’s normal’, ‘it’s a kidney infection’, the list goes on.

The huge challenge for GPs is that a lot of teenage girls experience period pain, only some of which will be caused by endometriosis, so it can be very difficult for GPs to distinguish who to refer for tests. It can get even more confusing after that, as scans only show up certain types of endometriosis, so women often get discharged back to their GP with no answers.

There’s one type of pain that we haven’t mentioned so far, but this is very important when it comes to endometriosis: pain with sex. And when it comes to this, it can be very hard to raise it with anyone, let alone your doctor. But you can’t afford to be shy about it.

Okay, if there were problems explaining your pelvic pain, things just got a whole lot more difficult. How do you talk to your doctor about sex, where do you start?

I had lots of problems explaining to doctors that I have painful intercourse. They didn’t really seem to understand and suggested it was due to different sizes of penises, or as I am quite small in height, it was down to me. Nobody really knew what to suggest except lubrication, and I found the conversation often got changed quickly. – Sophie

When it comes to explaining your pain to your doctor, including pain with sex, it’s best to be prepared:

We’ll take a closer look at painful sex in Chapter 4.

One of the complicated aspects of endometriosis is that pain isn’t always confined to the pelvis. It is another reason why it can be difficult to diagnose or understand. In particular, a number of women we interviewed experienced leg pain. A few of these women had endometriosis on the bowel, but not all of them.

Lucy’s leg pain was quite disabling. ‘I was prescribed amitriptyline and then nortriptyline [tricyclic antidepressants used to treat neuropathic pain] to try to help with the nerve pain. It was a constant “walking through water” feeling. Some days the leg pains were worse than the endo abdomen pains.’

Endometriosis that affects the ‘obturator’ nerve, a nerve that runs through the pelvis and supplies the inner thighs, can cause pain that radiates down the leg. Endometriosis can also cause leg pain when it affects the ‘pudendal’ nerve, a nerve that supplies part of the vagina and vulva.

Scarlett had terrible bowel pain which meant she couldn’t sit down. She was later diagnosed with bowel endometriosis but the pain was very disruptive to her life. ‘I couldn’t go to work, I just had to lie down because I couldn’t sit down in my job, most people would at least think it reasonable to be able to sit down, but no.’

We think of endometriosis as a gynaecological condition but it has a knock-on impact in quite a few other parts of the body. This is why functions such as walking or sitting can sometimes be seriously affected.

Aside from pain, the women we interviewed were most bothered by a mixture of other symptoms that can broadly be classified as gastrointestinal – such as bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation. It’s worth knowing that, when endometriosis affects other organs, the bowel is the one that is most commonly affected. But it’s complicated. If the pain associated with endometriosis is often enigmatic (i.e., sometimes there’s no pain with a lot of disease, but sometimes there is lots of pain with a little disease), then it’s probably no surprise that the bowels are playing a similar game. So, women with endometriosis-related bowel disease (that’s endometriosis growing on the surface of the bowel sometimes continuing all the way inside it and sometimes causing narrowing) may well experience bowel symptoms, but women who don’t have bowel disease may unfortunately also experience bowel symptoms. Confused? Well, let’s get the lowdown from these belligerent neighbours, the bowels.

Let’s first look at one of the troublesome and uncomfortable symptoms women identified – bloating. Sometimes, it was one of the main symptoms that resulted in women visiting their doctor, as Preena describes. ‘When I was 17 years old, I noticed that I was getting very bloated to an extreme level, and I didn’t know why. I looked like I was six months pregnant.’ Preena ended up being diagnosed with a large ovarian cyst as part of her endometriosis. But why would this cause bloating? Well, unfortunately we don’t fully understand why women with endometriosis experience uncomfortable bloating, but it is likely due to the inflammation from the endometriosis lesions.

Some women with endometriosis experience either diarrhoea or constipation, or both – again, whether endometriosis is on, in, or somewhere near the bowel may or may not affect how symptoms appear. Irrespective of this, the effects are the same: the bowels are not happy and the effects can be very debilitating.

So much so, that some of women were diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, long before they received their diagnosis of endometriosis. And, confusingly, some women have both IBS and endometriosis. We’re not yet able to explain fully whether the chances of having a diagnosis of IBS in women with endometriosis are due to misdiagnosis or true ‘comorbidity’ (i.e., that they are linked). Women with endometriosis may be operated on by gynaecologists with variable experience in the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Even during laparoscopy (see here), some gynaecologists may fail to diagnose endometriosis. The diagnosis of bowel endometriosis may be even more difficult for a gynaecologist with limited experience in treating the condition. So, bowel endometriosis may remain undiagnosed even when a diagnosis of endometriosis elsewhere is made. This is relevant because intestinal endometriosis lesions may cause gastrointestinal symptoms and mimic IBS. It’s perhaps not surprising then that women with superficial and/or ovarian endometriosis, and undiagnosed bowel endometriosis, are diagnosed with IBS and receive IBS treatments. The link between endometriosis and ‘true’ IBS remains to be proved.

Amy was very ill with bowel symptoms before she was diagnosed with endometriosis on the bowel. Her diarrhoea was so severe that she kept being hospitalised with it, as she explains ‘I couldn’t eat or drink without setting it off and I think I didn’t eat for a week once, and then I couldn’t drink either, so I ended up having to keep going into hospital to go on a drip.’

For Thea, it was the reverse – she started experiencing constipation with her periods and was very quickly diagnosed with endometriosis on the bowel. ‘I was in agony for two or three days and I would try anything and everything, which never really seemed to make much difference. Once those three days had gone, I would then go to the toilet and then my bowel symptoms just went.’

Nicole continues to suffer IBS-type symptoms with her cycle, and finds this challenging. ‘On my cycle, I have a week when it’s really bad and then it calms down, and then another week where it flares up, then it calms down. At the moment, it’s not so much the pain I get as the IBS. I can’t control it.’

Some women find changing their diet helps them to manage both their pain and their bowel symptoms. We’ll be looking at this further in Chapter 7: Adjusting life.

Endometriosis affecting the bladder or urinary tract is less common. When it occurs, it is far more likely to affect the bladder than the upper part of the urinary tract, such as the kidneys. Sometimes it affects the ureters, the tubes taking urine from the kidneys to the bladder, but again this is relatively rare. A couple of the women we interviewed had endometriosis affecting their bladders, one of whom was Emily. She explains how her bladder is affected: ‘When your bladder gets full, you can hold it, it’s not that, it’s not an incontinence feeling that I get. It starts to hurt and then after you empty, sometimes it hurts more.’

As with the bowel, the type of surgery involved for the bladder deserves special attention, so we’ll look at this in Chapter 2: Making choices: treatment options.

One of the symptoms that often gets ignored but appears to be widespread is fatigue – and actually, the fact that women with endometriosis feel fatigued makes a great deal of sense. First of all, chronic pain can be exhausting and this may make dealing with even small tasks a challenge. Symptoms can disrupt sleep, meaning that you don’t wake feeling refreshed and well. Also, endometriosis has a chronic inflammatory component to it, which means that there could be a knock-on effect on energy levels. We don’t yet understand enough about why chronic inflammation causes fatigue, but it’s thought that inflammation has an effect on the immune system and also on the brain and central nervous system, resulting in fatigue. If you then add on top of that the intriguing role of hormones, symptoms such as digestive problems and heavy bleeding, you’ve got the perfect combination of symptoms that cause persistent tiredness.

Preena struggles with this. ‘I’m often very tired, even when I’ve done nothing to be tired for. Sometimes I get pain from my remaining ovary when I’m walking. It’s just a mixture of things, it’s just the feeling of not being 100 per cent all the time.’

Beth also suffers a lot with fatigue, which has affected her studies, but it was difficult to know how much was due to her symptoms and how much was due to her busy student life. ‘During uni, things were getting worse but it was still just the monthly cycle of pain and bleeding, although fatigue did affect me more, but it’s hard to tell because it’s the first time in your life that you are truly independent and so it is really hard and you know, a degree is difficult and I had quite an active life, exercise, hobbies etc., so it was hard to tell how much was fatigue and how much was just doing a lot of stuff.’

As a final measure, then add on top of that loss of sleep from being in pain and trying to function in a world that doesn’t always understand ‘women’s problems’, then you’ve potentially got a recipe for exhaustion. Sophie says: ‘It’s when you’ve had days of non-stop pain, when you haven’t slept because of pain or can’t do anything because the pain is so bad or you have pain with fatigue. It becomes unbearable. Severe pain drains all your energy supplies so quickly.’

And it’s no wonder that some women therefore described to us how often they simply just don’t feel well, not 100 per cent. Imagine feeling like this for months on end, perhaps even longer. This is another symptom that can be so isolating.

Although women with endometriosis often suffer from extremely painful periods, many women with endometriosis report that their period ‘flow’ is ‘normal’. However some report irregular periods, prolonged bleeding, or premenstrual spotting. Others report that they experience heavy periods. We don’t know if this is related to endometriosis or adenomyosis, where endometriosis-like cells grow in the muscle wall of the womb, which we’ll talk about later in this chapter.

What we can say is that the women we spoke to reported a range of symptoms associated with bleeding, from bleeding after sex, which Nicole experienced: ‘it was when I met my husband and I started bleeding after sex, so I thought “oh this is not right, this is not normal”, so I went to the doctor’, to the frustrations of irregular or heavy bleeding experienced by others. Preena constantly has to plan to take sanitary pads with her, because she never knows when she might start bleeding: ‘I’ve literally got a constant supply of pads in my bag. You don’t want to have to constantly worry about it, that you might bleed on the spot.’

Chloe used to pack extra underwear to take away on holiday with her and take additional clothes to work, in case she bled through them. She used to bleed for 23 days a month. ‘I thought it was normal to take three sets of clothes to work, or to be on painkillers all the time. But then, suddenly, when it is not there, you suddenly go, oh. It was only last year that I stopped taking eight pairs of pants when I went away for two nights.’

When there’s such a wide range of symptoms for this disease, you might well be asking if there’s any correlation at all between symptoms and the type of endometriosis. As we mentioned right at the start, this is very tricky indeed. Why is this?

Well, for a start, there are women that have lots of tiny spots of disease scattered around their pelvis – called superficial or peritoneal disease – but we know that these can be women who have difficult, relentless symptoms. Remember that ‘superficial’ is used as a medical term to mean ‘on the surface’, not how it’s used in everyday life, where ‘superficial’ often implies someone is shallow or phoney. This type of endometriosis can be hard to treat surgically because there may be small amounts but they can be widespread. Beth describes this type of endometriosis and explains why she remains in constant pain. ‘I met with the specialist, and he said this is quite extensive endo. There is ten-plus years of scarring all over your peritoneum, bowel, bladder. There’s little tiny dots, but everywhere, so I never really had to worry about needing a bit of bowel removed or anything like that, but the lesions are everywhere, so it is easy to see why there is pain.’

Sophie also has superficial endometriosis and feels that women like her ‘tend not to be thought of so much’. She describes herself as ‘just someone with lots of pain.’

It can be much more helpful to think about the symptoms than the type of endometriosis when it comes to how women are supported. However, the type of endometriosis is more relevant when it comes to the specific surgical treatment – which we’ll explore a bit more in the next chapter.

Endometriosis can only be definitively diagnosed by laparoscopy, so one of the challenges is that tests such as scans, both ultrasound and MRI, don’t always show up endometriosis.

While endometriomas, or endometriosis cysts on the ovaries, would normally show up on an ultrasound scan or MRI, endometriosis in other areas does not often show up. But the real challenge can be that a woman with suspected endometriosis might end up having a whole range of other tests – some of them to exclude other diagnoses – and these can be extensive.

While there are no definitive blood tests for endometriosis, a woman with suspected endometriosis may well have not only standard blood tests that look, for example, at white blood cell counts and indicators for inflammation, but may also end up having tests such as a CA125 level. This is a test for a protein in the blood, called ‘cancer antigen 125’. It’s more commonly used as a test for ovarian cancer but some – not all – women with endometriosis have raised levels of this marker. It is increased with any condition that leads to ‘inflammation’ in the body, and so it is not helpful on its own as a diagnostic test for endometriosis. Also, a negative test is unable to rule out endometriosis.

Endometriosis can only be definitively diagnosed with a laparoscopy. This type of surgery is used to confirm a diagnosis of endometriosis, because the gynaecologist is able to see first-hand the disease and how it has manifested itself. It also gives them the opportunity to ‘biopsy’ it – to send a sample of it to the lab for analysis, to confirm that it is indeed endometriosis. A laparoscopy may identify signs of previous infection, such as pelvic inflammatory disease or adhesions (scar tissue). Sometimes a woman may be having a laparoscopy for abdominal symptoms where endometriosis is not suspected, so it may be found coincidentally, so there isn’t always time to prepare for the diagnosis.

Most women are nervous before a laparoscopy – after all, if it’s the first time you’re either having an operation or a laparoscopy, it’s an unknown. It involves having a general anaesthetic and most women will have a ‘pre-op’ appointment of some sort, where any tests can be done, such as blood tests, heart rate and blood pressure and the procedure can be fully explained. You’ll normally be weighed and given any specific instructions for the surgery itself, such as when to stop eating and drinking beforehand. These instructions are vital and must be followed exactly.

On the day, having surgery itself can involve a lot of waiting around – checking in for the surgery itself, meeting doctors involved in your care, such as the anaesthetist, who will explain the procedure and the risks of it, signing consent forms for the operation, waiting your turn on the list and then changing into a gown and surgical stockings for the operation. So, you’re now waiting for your first laparoscopy, you’re a little nervous, having never done this before. And it’s surgery – so it’s a big deal to be doing this. But you desperately want and need answers.

An hour or two later after your surgery and you’re in the recovery room, phew, hmm this morphine is definitely helping as you come round, things are really fuzzy, you’re feeling distinctly woozy and ever-so sleepy, maybe a little nauseous and rather sore but for now you’re just going to rest. Ah…

But wait! The gynaecologist is here, they’re beside you, they’ve got a furrowed brow and they’re saying something. What are they saying? They found WHAT? Endo something or other? What’s that?

You’ve entered the third stage – the ‘unknown known’ – you have a diagnosis but you may have absolutely no idea what it means. Some women have been well prepared before surgery, if endometriosis was suspected. But for others, after surgery might be the first time they hear the word ‘endometriosis’ and it can be a real shock, particularly when surgeons start talking about highly sensitive issues, like fertility, when a woman is in the recovery room and still coming round from an anaesthetic.

In an ideal world, the immediate aftermath of surgery wouldn’t be the time to find out you have the most unpronounceable disease that you’ve probably ever heard. This may even be the first time you hear the word. But we never promised you an ideal world, we’re dealing with reality here. You’re one of many patients, your gynaecologist has had a long day in the operating theatre. They may be running behind and they’re doing their best.

Providing high-quality information to women with endometriosis is about more than the timing and manner of those explanations, though clearly those matter. From the women we interviewed, what is explained and who delivers this information is also vital.

Let’s hear again from women, because whether they were diagnosed last week or ten years ago, they are unlikely to forget the moment they found out their diagnosis. As Lucy explains: ‘He woke me up afterwards and he just tapped me on the shoulder and said “I didn’t find any adhesions but I did find endometriosis, good luck!” And walked off.’

If you’re going to find out that you’ve got a disease you’ve never heard of before, the first communication on this is key, Zoe explains: ‘To be told by a surgeon when you’re 21 that it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to have children naturally, and fairly bluntly, it sort of sets the tone for the rest of your endo journey.’

And then for others, it can be more dramatic, as Daisy explains: ‘I remember coming round from my operation and him standing there and I was on morphine and out of it, and he just said “It’s not cancer, it’s an endometrioma”, and I had literally no idea what he meant.’

Immediately after surgery, and on morphine, is not the time to be asking questions about something you’ve never heard of, but sadly sometimes this is all the healthcare system allows. However, some women remember their gynaecologist going into a lot of detail, which can be frightening.

The doctor wasn’t particularly kind in the way he told me about what I had, and he made me feel more scared by what he told me. He told me that it was the worst endometriosis that he’d ever seen, that he wasn’t able to treat it, he had no idea how to deal with such a case, I would never have children … I burst into tears. I felt very bitter that I’d been dropped a bombshell and then left like that without any answers or explanation as to how that would affect me. – Madison

After surgery, it’s worth knowing that your gynaecologist sends a follow-up letter (called a ‘discharge letter’) to your GP to tell them about your procedure, what was found and what the next steps are. You can ask to be sent a copy of it.

We’ll look in more detail at laparoscopic surgery to treat endometriosis in Chapter 2, but here are some hints and tips if you’re about to have a laparoscopy:

Hints and tips if you’re having a laparoscopy

These may be performed in women with endometriosis who have bowel symptoms. Diarrhoea, constipation, bloating and nausea are common, not just with deep endometriosis that develops on or even in the bowel, but with all types of endometriosis as we don’t fully understand it. The investigations can range from sigmoidoscopies and colonoscopies, where a telescope is used to look inside the bowel, to barium enemas, where a substance that shows up on X-rays is inserted into the bowel to see if there is any structural abnormality, and to other types of X-ray.

Amanda was subsequently diagnosed with deep endometriosis in the bowel. She describes the various tests she had: ‘I had enemas and X-rays just to see if anything was going on, and he told me I had a strange-shaped bowel – that was obviously the blockage starting where the endo had infiltrated the bowel. He tried to do a colonoscopy on me and he couldn’t even get the paediatric one through because it was so narrow. It was agony.’

Thankfully, sigmoidoscopies and colonoscopies are usually painless and often performed under sedation – you can read more about this test opposite, where we’ve included hints and tips if you’re having a colonoscopy.

It’s important to note that for many women, these bowel investigations are being performed prior to diagnosis, meaning that women may be suffering and are desperate for an answer. Bowel investigations can be hard – and performed at a time when you might be quite unwell and without a diagnosis.

If you’re going to have a colonoscopy you will probably be feeling a bit nervous, and maybe a little embarrassed. Please be assured that probably everyone who has this done has felt a little unsure about it. Anything to do with the bowel can have us feeling a little alarmed. So, let’s have an honest, upfront look at this because it may be on your list of investigations if you’re having bowel symptoms related to your endometriosis.

The first part of the colonoscopy – which is sometimes the part that people fear most – is the cleansing of the intestines so that they are clean so that the doctors performing the colonoscopy (basically a long telescope that goes up your bottom) have a clear view.

This normally involves drinking – over the course of 12 or more hours – a special laxative drink. The hospital or pharmacist provides the instructions for your laxative drink. Note that you should always ask for advice about what to do before your colonoscopy from your consultant, a GP, nurse specialist or pharmacist.

You may plan a little ahead, so the day or two before you take your laxative you could eat a light or ‘low-residue’ diet, basically a diet that is quite bland and doesn’t include much fibre. This includes things like mashed potato, eggs, milk, white fish, chicken and white bread.

When you check the instructions on your laxative, it can sound like a lot to drink. Depending on the bowel preparation that is used, this can be up to a couple of litres. It isn’t always the tastiest of drinks so here are a few tips to make it more palatable:

Prepare your drink a little in advance and put it in the fridge; chilling it makes it easier to drink. You may even want to pop some ice into it. It’s also easier to drink with a straw.

Consider preparing it using one of your favourite cordials. Our top recommendation is ginger cordial but take your pick – in fact, pick a couple so you can have a selection and vary it a bit. You might fancy a different flavour for the second serving, if your drink requires it. Add the cordial when you are ready to drink.

Consider how you are going to while away the time whilst you drink the laxative. Perhaps watching the latest box set or movie, or listening to your favourite music. Whatever you plan to do, ensure you have a comfy place to relax in reasonably close proximity to the loo. Stock up on wet wipes, loo roll and nappy rash cream as you may get a bit sore after the bowel movements.

The laxative may start to work before you finish the first round of drinks. Not everyone finds it works as quickly, again we are all different. However, as the hours progress, your bowel will gradually, or maybe even quite rapidly, be emptied.

You won’t be able to eat until after the actual colonoscopy, as the bowel needs to be completely empty.

Feeling rather empty and quite a bit slimmer, you head off to the hospital for your colonoscopy. This is the time for your partner, family member or friend to drive you to and from wherever you need to be, as most colonoscopies are performed under sedation and you won’t be able to drive for 24 hours afterwards.

This is the part we can’t tell you much about. Five seconds of thinking – that telescope thingy is going to go into your bottom and suddenly the gin and tonic feeling of sedation hits, then you’re asleep … then you’re waking up in recovery. It’s all over. You remember nothing. Ah. Partly you are sorry not to have watched the screen for that journey into the depths of your large intestine, partly you are just so relieved it’s over. Afterwards, you might feel a little tired and windy for a while. It’s important to take it easy for the rest of the day and be kind to yourself.

But what may they have found? A colonoscopy may be used as much to exclude diagnoses that affect the bowel (such as inflammatory bowel diseases) when a woman is experiencing bowel symptoms. It would rarely be used to diagnose endometriosis – but it is a common procedure to investigate persistent bowel symptoms.

These are less common, probably because endometriosis of the urological tract—that is the bladder, ureters and kidneys—is less common. However, even in cases where endometriosis is not identified either on or in the bladder, it can cause bladder symptoms such as pain and frequency of passing urine. This is also not fully understood, but it can mean that women end up undergoing tests on this area of the body.

I had repeated renal IVUs and CT contrast scans. I had bladder capacity scans and CTs of my abdomen. I’d had repeated ultrasounds, internal and external. I had lots of blood tests, smears, lots of repeated investigations, internally, vaginally and rectally. – Sophie

In rare cases, endometriosis can block the ureter and urine exiting the kidney, causing the kidney to enlarge (hydronephrosis) and become painful. It is important that this is diagnosed early as it can cause long-term kidney damage if left untreated. An ultrasound or MRI that focuses on the renal tract, or CT intravenous urogram (CT IVU) that uses contrast material injected into veins, will detect hydronephrosis.

These are a lot of tests to be subjected to – and that is the point. You might have a negative ultrasound test, or even an MRI, but you could end up having a whole array of tests and investigations. This is as much a process of exclusion as inclusion but it can be exhausting and upsetting to undergo all these procedures.

Even with the most advanced scans, there are limitations, and it can be hard to pick up a full picture of the disease. Consultant gynaecologist Andrew Kent describes firstly how he relies on taking an accurate history from the woman. ‘If I have a patient who has come to see me with pelvic pain, I will take a detailed history with specific questions about endometriosis and the pain itself. What you are trying to do, in asking these questions, is to ascertain the nature of the pain to give an idea of whether it could be superficial or deep endometriosis or something else. The examination is tailored to confirm or refute the conclusions that you have come to in your patient’s history and allows you to draw up a list of differential diagnoses. A scan is not always required at this stage.’

Ultimately, he explains, only seeing it and feeling the areas of disease through a laparoscopy gives the surgeon all the information that they need to make an assessment about the overall treatment plan. ‘Even with the most detailed scans, you cannot get all the information required to allow a clear treatment plan. You can pick up endometriomas easily with ultrasound and MRI, but even an MRI does not provide you with all the information needed to plan surgery, especially with the more severe forms of the disease.’

If the absence of information and the delivery of a diagnosis of endometriosis is challenging for a woman, it can be even harder to then have to deal with some of the reactions from doctors, family, friends or colleagues, however well-meaning. It’s great when people have actually heard of endometriosis, but it can be equally frustrating dealing with some of the myths about it.

Often this involves women with endometriosis having to explain to others about what is really going on. Since this is a disease that affects everyone very differently, adopting an open and honest attitude to people’s comments can help to clear up any misunderstandings, however frustrating they are.

We’ve already looked at ‘normal pain’ – what it means to be a woman who suffers with painful periods and knowing what is ‘normal’ – as well as some of the myths that surround that. We’ve seen how this impacts on the journey to obtain a diagnosis for endometriosis. Sadly, some of the most common myths relate to things that ‘cure’ endometriosis. We should add at this stage that the notion of ‘curing’ endometriosis is quite controversial, but more of this later.

Sadly, although many women have successful treatment for endometriosis, there is, as yet, no known ‘cure’. Of course, there are many women who feel a lot better after treatment, but this isn’t going to help the woman on the receiving end of this statement to manage her symptoms and handle all that goes with endometriosis.

Friends, family and colleagues should adopt a listening, supportive approach – offering empathy and comfort. The experience of others is very unlikely to help a woman at this point in time, however listening to her explain her individual circumstances and challenges is likely to be beneficial to everyone. Asking open-ended questions, showing genuine interest and not jumping to offer solutions – these are excellent ways to approach women with endometriosis.

They think you can just take the tablets and it’s curable, and it’s not like that, so I think, if I’m explicit then he knows he can ask questions. – Lucy, talking about her colleague

This is probably one of the most upsetting things a woman with endometriosis can hear. First of all, it is wholly inappropriate to suggest pregnancy to a woman as a cure for a gynaecological disease. Some women may be desperately struggling to get pregnant – it is estimated that around a third of infertile women seeking fertility treatment have endometriosis and some are only diagnosed as part of this process. Secondly, whilst some – but not all – women experience a reduction in pain through pregnancy and whilst breastfeeding, they may well experience a return of pain and resurgence of the disease once their periods restart.

Some women reported that this comment may come from family, friends and even healthcare practitioners.

We’ll hear more from women about pregnancy in Chapter 5 and what it really means to be a woman with endometriosis, both during and after pregnancy.

This is the opposite of the baby myth, but is equally insensitive. Yes, having a hysterectomy stops periods but this is very unlikely to be appropriate as a first-line treatment in a young woman – and it may only be relevant if endometrial-like cells are specifically affecting a woman within the muscular wall of her uterus or womb – a condition called adenomyosis, which you can read more about later in this chapter. If you have a hysterectomy but not all endometriosis is removed at the same time, you may still experience the symptoms of endometriosis.

Luckily, many women have seen a change in this stance in recent years as Nicole notes:

‘When I was 21, the first thing my consultant said was you can have a hysterectomy. When I saw him after a few years, he told me that, “No, hysterectomy is a last resort because we’ve been finding that women have had hysterectomies, the endometriosis is still there, because there were patches of it where we weren’t expecting it”, so now they will only do it as a last resort unless the woman has particularly asked for it.’

Endometriosis does not affect any one ethnic group more than any other, but we should recognise the importance of racial and cultural differences that may affect attitudes towards pain and fertility, because awareness among some BAME (black and minority ethnic) groups can be lower. Women also reported that sometimes there are damaging stereotypes about different ethnicities and pain thresholds.

‘There are many cultural and social norm factors attributable to the higher level of lack of awareness,’ Afuah tells us. ‘For example, some BAME women don’t like to talk about menstruation, especially in public, to the point that if a woman has their period, the men in the household are not told, even when the woman is suffering pain – the general response is “she is not feeling well”.’

Endometriosis does indeed not have any barriers – women of any race can be affected – but there may be cultural barriers that deter women from seeking help. It’s important to be aware of these. For example, there may be additional pressure to be silent about menstrual problems, and there may also be family pressures to have children. ‘It is a less talked-about condition,’ explains Sanjeev, whose wife has endometriosis. ‘I am the only one who knows about it, about her problem.’

If menstruation is already taboo, raising awareness about endometriosis can be hard, but it needs to be done. Afuah tells us about a woman she has recently worked with. Afuah explains, ‘She encouraged her sister, who had unfortunately undergone FGM (female genital mutilation) during childhood, to seek gynaecological help. Previously, all her sister’s gynaecological problems were assumed to be due to the FGM. In short, her sister was eventually diagnosed with endometriosis.’ Information and education have important roles in this area.

Adenomyosis is defined by the finding of endometrial-like tissue within the muscular wall of the womb, called the myometrium. The cause of it is not known. It can be difficult to diagnose, but increasingly transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are being used. With transvaginal ultrasound, considerable training is needed to recognise the ultrasound pattern of adenomyosis. With MRI, the findings are less dependent on the person doing the scan, but it still depends on an observer who is expert in reporting such scans in gynaecology. Adenomyosis can be easily confused with fibroids (tumour-like overgrowths of smooth muscle in the uterus that are also associated with heavy periods) on ultrasound and MRI. But, a definitive diagnosis of adenomyosis can only be made with a biopsy (sample of tissue) and histological analysis (examination of the tissue with a microscope in the laboratory). This is not commonly performed for the diagnosis of adenomyosis and so the diagnosis is only usually made after hysterectomy (when the womb is routinely looked at in the laboratory).

Even when a woman has suspected adenomyosis, a hysterectomy is a life-changing operation and whether this is something a woman wishes to consider will depend entirely on her individual circumstances and her personal choice.

Let’s take a look now at one of the most used sources on information about endometriosis, its causes, symptoms and treatments – the internet.

Since many people only hear the word ‘endometriosis’ when either they themselves are diagnosed with it, or their partner, family member or friend receives a diagnosis, this may often be followed by a scrabble around on the internet to find out a bit more. This can be helpful, but it can also lead to much confusion, because endometriosis is quite an individual disease, not only in the way it presents, but also in how it affects women on a day-to-day basis. One woman’s endometriosis is definitely not the same as another’s – and so care is definitely required when looking at information on the internet.

There is, however, no doubt that the internet has raised some much-needed awareness about endometriosis – whether that is through social media, celebrities more willingly sharing information about their endometriosis, or the ability to search and access a much wider range of information. The internet has been a very important tool for the sharing of information. This is not just the case for endometriosis – it applies to a wide range of medical conditions or situations. Quite simply, when using the internet, we need to apply two very important human codes: those of common sense and courtesy.

Women identified both the benefits and drawbacks of the internet. Firstly, it was identified as an important way that family and friends could help them, particularly when newly diagnosed. Sophie really appreciated her dad and boyfriend doing this:

‘That evening my boyfriend came home with tons of information printed off the Endometriosis UK website. My dad had done the same. I couldn’t believe these two men were researching period stuff and helping me in my darkest hour… Those actions meant so much.’

But proceed with caution – this isn’t everybody’s way of working, as Scarlett explained:

‘I remember my friend was googling endometriosis because she’s a librarian but I said, I don’t want you to tell me what it says, I want to find it all out for myself.’

Daisy thinks that social media has led younger women to be more assertive, to take action and to ask for help – which may, in turn, lead to a quicker diagnosis than the seven to eight years it takes, on average, to receive a diagnosis of endometriosis: ‘I think we’re lucky with the Internet and Facebook. I think the younger girls definitely seem to be thinking to themselves as soon as they hear about it, right, well, what’s this, what am I going to do about it? Who’s there to help me? And I think that’s really brilliant.’

Poppy echoes the concerns about advice given on social-media sites – it’s important to distinguish between internet chat and the important medical advice given to us by doctors and nurses: ‘I think social media is a really bad thing at times, because it erodes the trust between a woman and her consultant. Sometimes it can be good because you can hear more things and it can actually make you more empowered and more informed, so you can make a more informed choice, but there are too many people out there who are willing to give medical advice when they’ve got none to give.’

A pain and symptoms diary