THE DIAGNOSIS JOURNEY in chapter 1 was quite challenging, wasn’t it? You’re probably thinking that the treatment of endometriosis should surely be more straightforward, shouldn’t it?

Well, this is a disease that doesn’t always play by the rules. If diagnosis was frustrating, choosing treatments is very much about selecting a route, trying it out and then choosing plan B if the first route doesn’t work out. We can think of it as a bit like satellite navigation, or GPS – we plan a route, but then traffic comes along, or a road gets closed, so we have to divert off and take an altered course. Let’s take a closer look at what this really means.

We’ve established a few essential aspects of endometriosis, notably that:

So, we just then need to factor in to the ‘route planning’:

Putting all that together sounds quite complex, doesn’t it? Well, it is. And on top of that, we can throw into the mix the fact that there are very few drugs that are specifically licensed for the treatment of endometriosis, and this in itself is a huge stumbling block.

The first form of treatment that many women will receive will be in the form of pain medication. There is a wide range of medication available to help control pain. Some of these are available over the counter and are used regularly for conditions like endometriosis, and others are prescription only and are generally taken for shorter periods of time.

Pain medications are an important aspect of pain management for many women with endometriosis, however, there are significant side – effects with some of them. For example, opioids can cause drowsiness and, in long-term use addiction, whereas NSAIDs (see below) can damage the stomach lining.

It’s important to discuss your pain with the GP as some women find referral to pain clinics and access to pain psychology services really helpful. We’ll look at these in Chapter 3.

In general, women will start out on the lower dose hormonal treatments before embarking on more ‘heavy-duty’ treatments. In fact, nearly all the women we interviewed had already tried one treatment long before they had even been diagnosed with endometriosis: the combined contraceptive pill (COCP). That’s a mix of female hormones both released by the ovaries – oestrogen, which is the main female sex hormone, combined with progestin. The two hormones ‘trick’ the woman’s body into believing she is pregnant by stopping the ovaries from releasing an egg every month – this is called ‘anovulation’.

So why is this relevant to women with endometriosis? Well, whilst a woman is on the combined pill, her periods are likely to be lighter and less painful (and the pill can even lessen the pain she may experience outside her periods) so although it is licensed as a contraceptive – i.e., to stop a sexually active woman becoming pregnant – it is also used to improve the symptoms of endometriosis.

It can be effective for some, but it is not without issues, and some women experience side effects.

Many women take the combined pill as teenagers before they receive a diagnosis, taking it for three weeks of the month and having a one-week break where they may have a lighter bleed than a normal period.

Nicole started taking the pill when painkillers weren’t working as well as previously. ‘My mum took me to the doctors, they gave me mefenamic acid and ibuprofen and just said “oh get on with it”, you know, “this is your life, this is what being a woman is like”, so I carried on until I was about 16 and then they said “okay, we’ll try the pill”, so they put me on the pill and it was all right. I’d get three weeks of okay and then a week where obviously I took a break because they didn’t really know it was endometriosis.’

Sophie also waited until she was 16 to start taking the pill and found it really helped her symptoms at this point: ‘I regularly saw the GP who wanted to start me on the pill but my mum was not keen on this so I didn’t go on it until I was 16. At this point, it really helped with my periods and helped to make them a lot lighter.’

Not all women found the pill helped when they were teenagers. Saskia was one of these girls: ‘I went on the pill for a little while when I was about 13, 14 maybe, and the GP said: “well, periods do hurt and there can be a bit of pain, but maybe you can try going on the pill for a little while and see if that helps”, and it didn’t really but nobody said it was a big deal and as a teenager you trust what your parents are saying and what the doctors are saying.’

Amanda went to her doctor with heavy, painful periods in her teens and was given the pill. She tells us that it was effective, but her symptoms returned as soon as she came off it. ‘When I got married, when I decided to come off the pill because it wasn’t a problem if I fell pregnant, I had awful pains, I’d pass out, doubled-over every period.’

Whilst women either got some, or a lot of relief from the pill when they were suffering as teenagers, they consistently reported that their symptoms came back once they stopped, with many women referring to the way the pill had ‘masked’ their disease. It is in looking back that perhaps women felt they did not have the complete picture, because they did not have a diagnosis.

The contraceptive pill still is an important and effective treatment for heavy, painful periods and, whilst we await a better diagnostic tool, we can expect that women with symptoms will continue to be prescribed this treatment, but we can hope that communication between women and doctors about endometriosis may improve, so that women receive a possible diagnosis for their symptoms, and coming off the pill and the symptoms returning is not a surprise.

So, if coming off the pill may be a problem, surely one solution is to go back on it? Well, it’s not quite that simple and there are many reasons why a woman may want to – or have to – stop taking the pill, including trying to get pregnant.

It’s worth also considering that when the pill is prescribed to women with a diagnosis of endometriosis, it may be taken in a slightly different way than when taken as a contraceptive. Why is this?

Gynaecologists who prescribe the pill to women with endometriosis may prescribe it to be taken ‘back to back’. What that means is that instead of having three weeks on and then a break for a week to have a light bleed, women may take it without any break at all, perhaps for a period of three months or longer (‘tri-cycling’), when they then have a short break to have a bleed. In this way, periods are minimised and therefore the bleeding from endometriosis lesions is also minimised.

Thea started taking the pill in this way following major surgery for bowel endometriosis. She started by tri-cycling the pill, taking it for three months and then having a short break, but then started taking it continuously: ‘I take the combined pill now and it was my consultant who put me on that. I was originally on it on a tri-cycle basis but then when I saw him in the follow-up appointment he said that I could take it continuously. He said to me there was no reason why you can’t, he basically said it’s better for me the fewer cycles I have, the less chance of it reoccurring.’ So, we’ve seen that the pill may have a role to play to help women, but what can women do if this route is not working or is not a viable option, perhaps due to the side – effects a woman experiences?

At this stage, one of the questions you might have is this: if endometriosis is a disease that depends on hormones – and in particular oestrogen, the main female sex hormone – why would a treatment that combines both oestrogen and progestin, the synthetic form of progesterone, be used to treat symptoms of endometriosis?

Well, this is a difficult and interesting question. Progestogens (the term that describes the body’s natural progesterone and synthetic progestins) are thought to work by stimulating ‘atrophy’ or regression – wasting away – of endometrial lesions. But their effectiveness in treating endometriosis is not just linked to their ‘growth inhibiting’ actions, but linked to the fact that they can cause anovulation. This is when the ovaries do not release an oocyte (a cell that forms an egg) during the menstrual cycle). They also result in lower oestrogen levels, slow down blood vessel growth, and are anti-inflammatory.

Some women may find that using a progestin-only treatment is beneficial for relieving symptoms. These can be prescribed in several different ways, including the mini pill and within an implant placed inside the uterus, called the MirenaTM coil (or intra-uterine system, IUS), which releases small amounts of progestin and lasts for up to five years. The mini pill involves a higher dose of progestin but has the advantage of flexibility – you can stop it whenever you like – whereas the MirenaTM uses significantly smaller amounts of the drug because it is situated inside the uterus and therefore less drug is needed. The MirenaTM needs to be inserted by a trained healthcare professional and must also be removed by one – it’s not a short-term treatment so it does need to fit in with a woman’s long-term plans.

Other progestogen treatments include the long-acting progestin injection (such as Depo-ProveraTM), which is given into the muscle or under the skin every eight or twelve weeks; a progestin implant that is put under the skin in order to offer you an even dose that lasts up to three years (such as NexplanonTM); and a tablet called Norethisterone, which is another synthetic progestin that is taken daily. Essentially, these all have similar effects of reducing the bleeding a woman experiences and therefore minimising bleeding from endometriosis lesions.

What did women tell us about progestogen-only treatments? Experiences were divided – but again we should remind you that every woman responds differently.

Madison has been taking Norethisterone for some years, which is not specifically licensed to be taken for endometriosis in this way but it suits her well: ‘After the bowel surgery I’ve been put onto a medication where I have a very low dose of a drug that stops my periods so I don’t ovulate at all, so since my surgery I have managed to maintain this very low dosage. I’ve had a great recovery from the surgery and I’ve managed to stay very well in terms of endometriosis. I recently had a scan and I don’t actually have any endometriosis showing at all and I haven’t had any recurrence of endometriomas.’

Some women experience excellent symptom relief from the MirenaTM, which can last for up to five years before it needs to be replaced.

Afuah had her MirenaTM coil inserted after many years of endometriosis, including several laparoscopies and two pregnancies. She has experienced long-term symptom relief. ‘Currently, my endometriosis symptoms are well controlled with the MirenaTM coil, which I call “my second friend” because it’s been amazing. I have been quite stable on it. I have been symptom-free on it since then and I have just had it replaced.’

However, five years of symptom relief is certainly not guaranteed. ‘I had a MirenaTM coil inserted,’ Lucy tells us, ‘and then I was fine for two years.’ After this time Lucy found her symptoms started to return.

Some women find that symptoms will be improved rather than eliminated as Emily found: ‘I’ve got the MirenaTM, it’s settled really well for me. It doesn’t solve things but it’s definitely an improvement.’

A MirenaTM coil may be inserted by your gynaecologist, GP or in a family planning or sexual health clinic. Some women may be anxious about having the coil inserted or removed and replaced. It can sometimes be more painful and potentially harder to insert when women have not had children. Some hospital centres that treat women with endometriosis may insert coils under sedation, or sometimes they are inserted at the same time as a laparoscopy when a woman is under a general anaesthetic.

There can be challenges with the MirenaTM coil. It’s not for everybody and it can take a few months to settle, in which time a woman may have to cope with erratic bleeding, which can be troublesome. That said, for some, persistence pays off and things settle down.

Poppy still has bleeding with her coil, and wonders what is happening inside. ‘Although I’m on the MirenaTM now, and I have been for over a year, I still do get a bleed; it’s not every month but I still do get a bleed.’

If the MirenaTM can sometimes be challenging to insert, removal is generally much easier and can often be done by GPs who have trained to do this. The MirenaTM can be a great option for some women but it is not suitable for everyone. Why is this?

Scarlett’s gynaecologist was simply unable to put the MirenaTM coil inside her because her endometriosis was so severe at that stage. ‘I woke up from the surgery and he said to me, “oh there’s been a complication, I couldn’t get the coil in”.’ Scarlett later went on to have a hysterectomy and bowel surgery for severe endometriosis.

So, there may be times when the coil simply cannot be fitted. We also cannot ignore the fact that some women dislike the idea of having an object inserted into an area of the body that is already painful.

The MirenaTM coil, like all the other progestogen treatments mentioned, was developed as a contraceptive and is not specifically licensed for the treatment of endometriosis, however it remains an important treatment option for women with endometriosis. But it isn’t a solution for everyone. So, what other treatment routes are available?

As you can imagine, with a disease like endometriosis it often isn’t a question of having one surgery or one course of treatment and then the job is done – sometimes that is the case, which is wonderful. But for many women, the journey may well involve several different treatments or surgeries – or sometimes even many of them. What happens when we hit a roadblock, or have to take a detour on this long journey?

At this point, the treatments start to get a lot more intense. We’re talking about higher doses of hormones, ones that trick women’s bodies into thinking they’re in the menopause. And that’s a very serious thought, especially for a young woman.

Why would women consider these drugs? Well, firstly the simpler contraceptive-type treatments don’t work for everyone, or perhaps some women don’t achieve long-term symptom relief from them. Secondly, there may be specific times, such as before certain types of surgery, where these drugs are used to dampen down the disease to make the process of surgery more straightforward.

So what are these treatments and how do they work? These treatments are called gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists, or GnRH agonists, and they work by reducing the body’s production of oestrogen and testosterone – you may think of this as the ‘male hormone’ but it is also found in lower levels in women. That’s why they’re not only used for endometriosis, but they’re also an important part of treating certain hormone-dependent cancers, such as prostate cancer in men and certain breast cancers in women. Some of the drugs used are:

There are also others that may be used, e.g. Buserelin and Naferelin, that are delivered by nasal spray.

These drugs work by blocking oestrogen and progesterone production, so the woman is put straight into a temporary menopausal state, her periods cease, and therefore the endometriosis lesions are thought to become less ‘active’. Drugs can be given via an injectable implant either on a monthly, or even three-monthly basis. Once the injection has been delivered, the drug takes effect quickly, but once the month or three months is up, the drug either needs to be re-administered or the effects are reversed. That means not only that the woman will come out of her temporary menopause, but also that any remaining endometriosis will again become active – unless it is removed by surgery at this stage.

These drugs are licensed for six months for the treatment of endometriosis and the three-monthly preparation is not licensed for endometriosis at all, but they can be given for longer or as the three-monthly preparation if a woman wishes. Why are they licensed for only six months? Well, although the effects of the temporary menopause are reversible, these are ‘heavy-duty’ hormones with significant side effects (such as thinning of the bones – increasing the risk of osteoporosis). It is recommended that if women use GnRH analogues beyond six months, that they also take ‘add-back HRT’ with them; that’s using traditional hormone replacement therapy combining small amounts of oestrogen and progestin to help relieve some of the menopause symptoms and side effects.

As we take another pitstop to hear again from women on their experiences of these drugs, it is worth again considering that these medications form the main body of drugs currently licensed for the treatment of endometriosis – and yet they are only licensed for six months. This is obviously sadly at odds with a disease that can potentially affect a woman for the whole of her reproductive life and occasionally beyond that.

Women told us that, when it came to GnRH agonists, they often experienced a lot of relief from their endometriosis symptoms. Sophie says: ‘Zoladex totally gave me my life back, I managed to get back to work on it.’

Sophie wasn’t able to have add-back HRT throughout her treatment due to a family history of breast cancer and cardiac problems. Some women did take add-back HRT with their GnRH drugs, as Olivia did. She tells us her consultant ‘suggested I try Prostap again but with HRT, so I tried that, and actually it gave me a new lease of life for, I’d say about 12 months.’

A few women had taken GnRH agonists prior to major bowel surgery for endometriosis, women like Thea, who says, ‘He then started me on Zoladex before I had the op. It was about six months, because not only have they got to find the time for those two surgeons to be free together, but he wanted to give it a good amount of time for the Zoladex to kick in, for the inflammation to go down and hopefully make the surgery a bit easier once they’re in.’

Madison also had GnRH treatment before bowel surgery and felt that whilst she had some side effects, the benefits outweighed these. ‘I don’t think it was as bad as I was expecting it to be, I mean the hot flushes weren’t brilliant; I got hot at night, but actually the fact that it stops your periods, I didn’t feel overly emotional on it, so I really didn’t find Zoladex that bad at all. And it obviously did the job for quietening down everything for the next operation.’

But does it work for everyone? No, it doesn’t, unfortunately – but then there isn’t one single treatment that works for all women, so this is no surprise. For some women, the range of side effects outweighed any improvements to their symptoms. Zoe told us, ‘I tried Zoladex, which was a pretty horrific six months. It didn’t really alleviate the pain, it induced menopause, and even with HRT, I just felt so unwell for that period of time.’

Sometimes women may be offered these heavy-duty hormones at a time when perhaps they have not had chance to ask questions, or the effects of it have not been fully explained to them. This occasionally means that women believe they have been given a treatment that would cure them completely. Olivia explains, ‘So for me, I thought it’s like having an infection where you have antibiotics, you’ve just got to do this for a certain while and then you’ll be fine at the end of it, so I was quite happy with that and thought oh, fair enough if it’s helps. The Zoladex didn’t really improve things for me.’

Chloe took GnRH agonists with add-back HRT and weighed the side effects she experienced, such as hot flushes, hair loss and restless legs against the benefits she obtained. Chloe was able to rediscover the woman that she was without endometriosis. ‘The exercise that I do now, there is no way I would have even contemplated cycling to the end of the road, let alone doing 120 miles or whatever … for everything that you lose with the injection, you can gain so much because it gives you and your system the opportunity to see what life could be like. And even if there are some side effects, they aren’t going to be there for ever.’

In short, these treatments can be tough – the side effects individually, the appropriateness of taking HRT as an add-back therapy and the impact of the treatment on a woman are very personal – but these drugs mean that sometimes women return to work, or are able to resume important hobbies and interests, to do the things that make them happy. We leave the final comments on these drugs to Chloe, whose life has been heavily impacted by deep endometriosis:

You talk to the doctors and the doctors are saying, it’s all right, all it’s doing is switching off the signal between your brain and your womb. But your womb and your ovaries are vital organs, so, you know, that’s like a mainframe of what keeps your body going. So as much as it was sabotaging my body, it was also doing a really vital job. So going on Zoladex for me, I think for any woman, is a big deal.—Chloe

Rarely, ‘aromatase inhibitors’ are prescribed for women with endometriosis who have not had success with other treatments or who cannot use them because of their side effects. Aromatase is a protein in the body that is responsible for producing oestrogen. Normally, it is found in the ovaries, and to a much lesser extent in the skin and fat.

Research has shown that aromatase is also found in high levels in the lesions of women with endometriosis, and that inhibiting the aromatase by giving women an aromatase inhibitor suppresses the growth of their endometriosis, and reduces the associated inflammation. The aromatase inhibitors used for endometriosis include letrozole and anastrozole.

To date, only a few studies involving a limited number of women have been carried out, but these studies indicate that aromatase inhibitors markedly reduce the amount of endometriosis and pelvic pain in most women. These drugs are used to treat some breast cancers but they are still in the experimental phase for treatment of endometriosis, and it will take more research to see if, in the longer term, they provide an effective treatment. Like all the hormonal treatments for endometriosis, aromatase inhibitors will not improve a woman’s chance of conceiving, so they should not be used as a treatment for infertility.

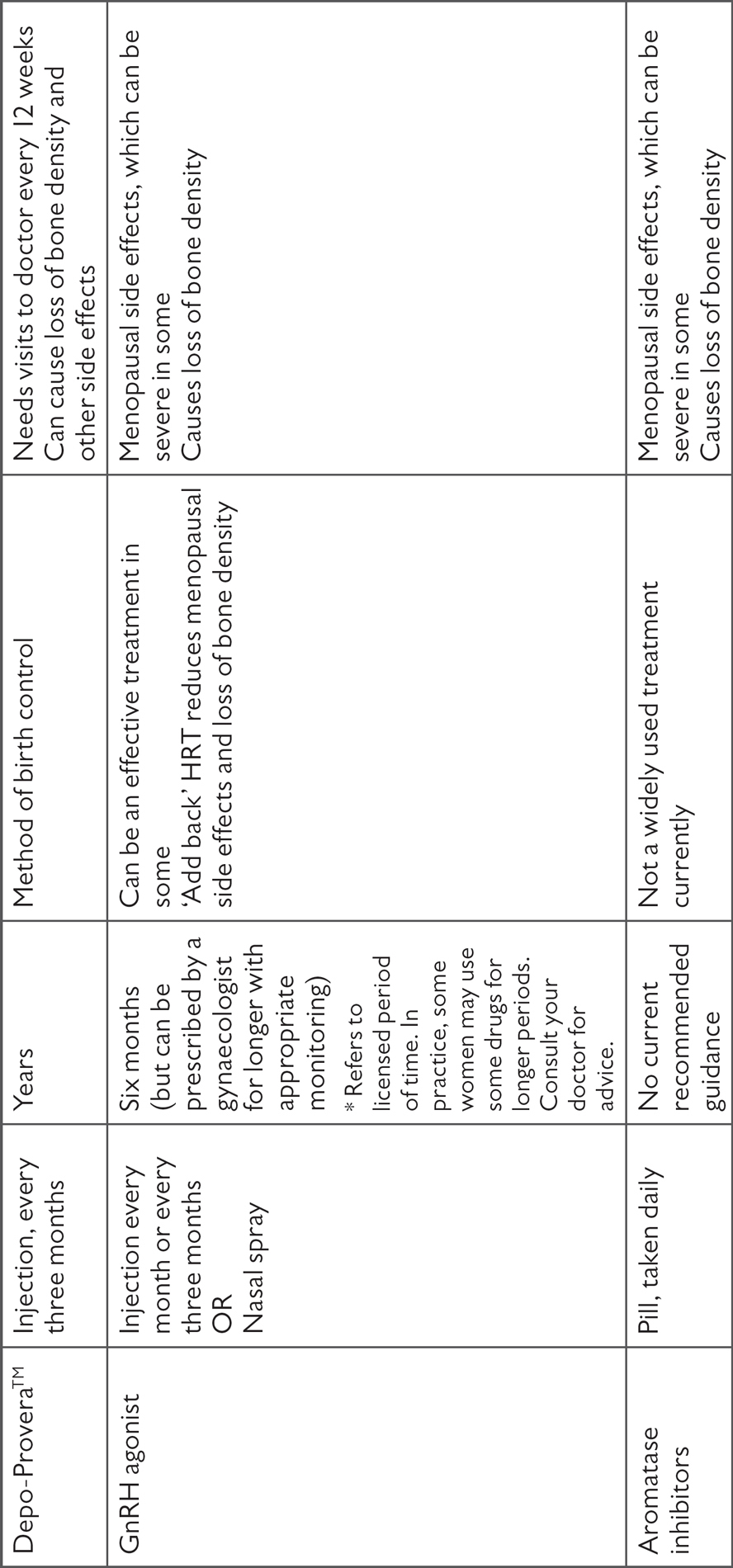

We’ve looked in detail at a lot of different hormonal medication, so let’s take a look at this in summary:

Surgery is a large topic and can be a really important route not only to definitively diagnose endometriosis, but also to manage the disease and its symptoms. The aim of surgery when used as a ‘treatment’ is to completely remove or ‘destroy’ the endometriosis.

Endometriosis surgery, as you can probably imagine, ranges from straightforward to highly complex gynaecological procedures that involve a range of other surgeons and specialities, such as colorectal and urology. Most surgeries for endometriosis are done using a laparoscopic (keyhole) approach. Here, we discuss the role of surgery for endometriosis in general, with a focus on surgery to treat pain, and in Chapter 5, we look specifically at endometriosis surgery for infertility.

Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis always involves a general anaesthetic, so you’re asleep for the operation. It involves making two or more small cuts on the abdomen, usually in the belly button and then others surrounding that, depending on what is to be done. These cuts are about 5–10mm each and are often referred to by the medical team as ‘port sites’ because they will be used to hold a specific instrument – firstly, the laparoscope, which is a short instrument with a camera on the end that the surgeon uses to see what is going on, and secondly a tube that pumps carbon dioxide gas into the abdomen, so it’s inflated to allow room for the surgeons to do their work. There may be up to five or six ports for more complex surgery as many different instruments may be used to move, cut or burn diseased tissue, depending on what is being done. The images from the laparoscope are shown on a large screen and are highly magnified, so everyone in the operating theatre has a really good view of what is going on.

Who’s in the operating theatre? Well, apart from the gynaecologist, there will be the anaesthetist and then a selection of other staff including several scrub nurses, who look after all the instruments, various staff assisting the gynaecologist such as more junior doctors who are specialising in the field and training, as well as doctors assisting the anaesthetist. Everyone is there to make sure the operation goes as smoothly as possible and that the woman is treated with the best possible care before, during and after surgery. Even before a woman is anaesthetised, various observations are made, such as blood pressure and heart rate, and from the moment the anaesthetic is given (normally via a thin tube called a cannula that is inserted into the back of the hand), a team of people are monitoring her constantly.

This team is crucial: they are working closely together and are sometimes standing for long periods of time, performing meticulous work within the confines of a woman’s pelvis, which is a tightly packed place containing lots of different organs and structures.

When you’re under general anaesthetic, you’re given drugs to help with any post-operative pain or nausea. When you wake up in the recovery room, you will be assessed to see how you’re feeling and any medication adjusted accordingly. Once you’re comfortable, you’ll be transferred to a ward – perhaps within a day surgery or short-stay unit – to recover. Usually, this can be quite quick but, again, everyone is different.

Lots of observations are taken in the immediate hours after surgery to check your recovery, and you’re encouraged to try and drink and eat a little afterwards. The nurses will want to know whether you have been able to pee afterwards, as you can’t go home until they know your bladder is working properly. Sometimes it can take a while for the bladder to start working again, which occasionally requires the insertion of a urinary catheter for a day or two – sometimes longer if work has been done on the bladder itself. Very occasionally, a woman may go home with a catheter – you can read more about this later in this chapter.

Endometriosis surgery can be diagnostic, potentially ‘see and treat’, or planned ‘elective’ surgery where you know the likelihood is that the endometriosis is more complicated. The uncertainty about what you’ll find is the biggest challenge with surgery.

Whilst all women referred for a laparoscopy will see a gynaecologist in the outpatient setting prior to their surgery, it’s important to realise that the surgeon who does the laparoscopy may not be the same gynaecologist who they saw in the clinic. This is all to do with the NHS centralised booking systems for surgeries. In some circumstances the surgeon will have not had the opportunity to see any of the patients on their list before the day of their operation, so they may feel concerned about whether the patients will have been prepared appropriately; from a physical, medical point of view, emotionally, and from an educational point of view, with a full understanding of why they’re here for the surgery.

Hopefully, by this point you will have a full understanding of what the surgery involves and what is happening but if you do have any questions or queries, make a note to ask your surgeon.

If the surgeon discovers that their patient has endometriosis, if it’s superficial disease, the surgery is usually straightforward. The surgeon will either be excising it, or burning it away with diathermy (see here). Most surgeons will ‘see and treat’ simple disease. If not, the patient may be asked to come back and have another surgical procedure, or may not be treated and instead offered medical management.

A number of surgeons find that the most unsatisfactory part of their job is how the NHS is set up for them to see their patients after surgery. What’s frustrating is that the patients have just come round from their anaesthetic, maybe they’ve managed a drink or a sandwich, they’re awake, but they’re often a bit drowsy, and struggle to remember what was said. Sometimes, patients don’t even remember anything about what was said to them immediately after their surgery.

Before the NHS became so busy and short-staffed, patients would be invited back for a check-up about four to six weeks after their surgery, with the opportunity for a discussion about the operation, as well as to find out how they were getting on. Unfortunately, surgeons don’t have that opportunity any more so it can be useful to ask for a copy of the letter that your surgeon sends to your GP.

Most patients are offered an appointment to come back to clinic maybe six months later, to see if the surgery has helped or not. Even if the surgery has helped, it is important the patients have had the opportunity to talk about what was found during the surgery properly, and understand what was done, as well as ask any questions.

In an ideal world, most surgeons agree that they would like to see their patients pre-operatively with an endometriosis specialist nurse, who the patient would have seen before the surgery. And the same nurse would phone them after their surgery – to check that they understood what happened and how they are getting on. Sadly, many hospitals won’t have a specialist nurse – and far less have a specialist nurse who has time to phone all the patients who have had surgery.

There is a lot of debate about the type of surgery that is done to remove or ‘destroy’ the endometriosis, so it’s worthwhile taking a moment to explain the differences:

In general, which method of surgery used will vary depending on the type and location of a woman’s endometriosis. Your gynaecologist may use both ablation and excision during your surgery. Excision rather than ablation is usually recommended to treat endometriomas to preserve as much of the ovary as possible.

Unfortunately, even if all endometriosis tissue is removed, relapse of symptoms may occur and up to 30 per cent of women have further surgery within five years. This may not be what we want to hear – we want surgery to be a cure after all – however, we need to be realistic and consider it a treatment rather than a one-off cure.

Let’s hear from women about their surgeries – what were their experiences and what tips do they have for others going through the same thing?

Whilst diagnostic only surgery can be necessary – particularly if the surgical team are not in a position to deal with complex disease, find something unexpected, or it is emergency surgery – it was frustrating, explains Saskia, to have to wait for a second surgery. ‘I had that laparoscopy, and because it was not a planned surgery, they didn’t do a great deal, so I got put back on the waiting list for another lap to be treated properly.’

We’ve seen what a puzzle endometriosis can be, and whilst it might feel frustrating to wake up from one surgery to be told you will need another, it is right for a surgeon not to operate if they have any concerns. They may need to have the right people in the operating theatre to do the operation, for example, a colorectal surgeon may also be needed, so severe or deep disease may not be able to be treated at the same time.

Some women spoke of how much better they felt after surgery, even within quite a short time period. Scarlett tells us ‘I remember waking up and after the first two or three days thinking “I feel so great”, how bad had I been feeling before? – I think I knew I’d felt bad, but it was only when you feel well that you realise how bad you’d been feeling.’

Sometimes women end up having surgery again within a short period of time, which may be to treat new disease or deal with scarring (also known as adhesions). Emily found this was very successful. ‘He booked me in for another lap, which was six or seven months after the first one where he did excision and after that, I felt fantastic, within a week I felt better and had more energy than I had done. He said there wasn’t much there and interestingly, where it had been lasered off, it hadn’t come back.’

For the woman herself, surgery is about much more than just the procedure itself – there’s also the recovery, the risk of complications, time off school, college or work and missing out on social life, exercise and normal day-to-day life. This can be very frustrating. It can also take its toll emotionally, as Scarlett found when she had made the decision to have a hysterectomy, but was also offered another laparoscopy instead: ‘If I’ve just had four other surgeries, why wouldn’t I have to have another surgery? He wasn’t really offering me anything different from anyone else and of course when I told him that I’d been bleeding and the pain when I went to the toilet, he said to me, we need to do an MRI and at this point, I just burst into tears and said I can’t, I don’t want anything other than my (hysterectomy) surgery.’

Most surgeries for endometriosis – even complex disease – are done laparoscopically. Very occasionally, women end up having open surgery – called a laparotomy. This means there is a larger cut in the abdomen, which allows a surgeon to have more access. However, the magnification tools used in the laparoscope are not used in this circumstance, so the field of vision is different. Thea had to have open surgery to deal with a large endometrioma and disease on her appendix. ‘They couldn’t remove the cyst because it was too big to take out through keyhole surgery and the endo was wrapped around my appendix so they said you’re going to have to come back and we’ll do open surgery.’

Women will be given advice by their hospital in terms of what to expect after surgery and how long to expect recovery to take – but this is guidance. After surgery, any concerns should be discussed either with the hospital or with a GP. Some of the risks of surgery include damage to adjacent organs in the pelvis, bleeding or infection.

Recovery can be varied – not only from one person to another, but from one procedure to another. No two people or procedures may be the same. But let’s look at some of the advice from women as to how to manage recovery from a laparoscopy. What does Zoe recommend? ‘Really, it is just about resting, not rushing, and building up your ability to walk and sort of re-inducting yourself back into society, into life.’

Don’t be deceived by the small cuts. Nicole tells us, ‘I think one of the GPs put it really practically for me. If you had a great big gaping wound across you, you’d realise that you couldn’t do stuff and you’d realise that your stomach had been incapacitated. Well, that’s it, just imagine that big scar across your stomach and you can’t move because that’s what you need to do, you need to rest, you need to give your body time to heal, your abdominal wall time to knit back together – because when you look at keyhole, it’s just two little marks and you think, how can I be in so much pain?’

And in terms of preparing for hospital, Thea suggests to ‘always pack more clothes than what you think you need. You might be in there longer. I would definitely say to ask questions. Make sure you understand what they are looking for, what they’re going to do and then just as much as afterwards what are they going to do, what they found, what the step is after that.’

Olivia felt that she was treated with dignity and respect after surgery, because she received excellent explanations of what was done by her consultant. ‘After the surgery, he told me exactly what he’d found, where he found it, how he’d managed it and what he’d done … he treated me like a normal person and discussed and respected the fact that it was my body, which was just a breath of fresh air.’

We’ve seen before that there are different types of endometriosis – the superficial/peritoneal type that can be widespread but doesn’t penetrate deeply into organs, ovarian endometriosis that manifests in ‘chocolate cysts’ or endometriomas, and the deep type of endometriosis, often referred to as ‘severe’. When it comes to surgery, this is probably where these definitions matter the most.

Why is this? Well, firstly the type of surgery done for deep endometriosis – disease that may have grown into organs like the bowel and bladder – is very specialised. This type of surgery, usually performed laparoscopically, was able to develop because of advances in the type of laparoscopic instruments available, one of which allowed surgeons to stop any bleeding and another which allowed surgeons to perform surgery by keyhole without losing the gas inserted to inflate the abdomen and allow for a clear view.

This multidisciplinary approach needs the involvement of a much wider team of people, some of whom are other specialist surgeons, such as colorectal consultants or urologists, and others who will be involved in non-surgical interventions, such as clinical nurse specialists or pain consultants.

If you’ve been referred on to tertiary care, to an endometriosis centre with a multidisciplinary team, what can you expect? Earlier, we looked at laparoscopic surgery, both as a tool to diagnose and to treat endometriosis. This second type of surgery is the ‘planned complex’ surgery. These are patients who’ve maybe had previous surgery for endometriosis so the surgeon knows the surgery is going to be difficult, or who during their planning have been noted to have possible scar tissue or disease attached to the bowel or bladder, or deep disease, or disease in places which is going to be difficult to remove without damaging other structures.

Most surgeons will discuss all complex surgical patients at a ‘multidisciplinary meeting’ with other specialists in advance so that they are planned and organised appropriately. The majority of patients will have been seen and given plenty of time to discuss the implications of their surgery, both with the gynaecology team and, if there is bowel involvement, with the colorectal team. In these situations, generally patients are very aware of what the surgery is likely to entail, the risks of the surgery, and have had some discussion about whether or not the surgery will or will not be effective.

Even though the surgeon knows in advance that these surgeries are going to be difficult, they will probably feel a bit more comfortable with the surgery, because they’re less likely to find something that they weren’t expecting. Surgeons are always hoping that perhaps the surgery is going to be less complicated than they have anticipated, but these are surgeries that are likely to be more complicated, and have a higher risk of possible complications. So the surgeon, as well as the patient, has to be prepared to deal with that afterwards, both in terms of managing the patient, breaking the news to them, and explaining what’s happened to the family, if there are any complications.

We don’t know exactly how many women with endometriosis end up with the disease growing next to, on, or actually in the bowel – estimates vary between 5 to 30 per cent of women with endometriosis. Turn back to the diagram of a woman’s anatomy at the start of this book (see page xxi). The lower part of the bowel, which is the rectum, is the most commonly affected place. Why is this? Well, this is next to a place called the pouch of Douglas, which is the name given to the gap between a woman’s uterus and the rectum. When there is disease here, referred to as a ‘rectovaginal nodule’, it can be very painful and is a difficult place to operate on. Why is this?

Consultant gynaecologist Andrew Kent explains: ‘It is challenging surgery because you are not operating on anything that is remotely normal in terms of tissue planes.’ So, endometriosis in this area can distort the normal anatomy and make it hard to see what is going on.

Sometimes this type of surgery would be a ‘two-stage’ process, as in the woman may have had a laparoscopy that established that there was bowel involvement. The downside of this may be that treatment takes longer, but that means, says Andrew Kent, ‘That you can sit down with a patient during the time that we are ‘down regulating’ (i.e., on GnRH drugs) and have a sensible discussion about what we have found and done at the first operation and what the next bigger operation will most likely involve. The only thing that we cannot be absolutely specific on is exactly what type of bowel surgery will be required (in terms of removing the disease by a “shave” or a “disc” or “segmental” resection) as this sometimes only becomes apparent when we start working through the nodule. As a consequence, we consent up to and including a bowel resection and we always do the second procedure with a colorectal surgeon. Sometimes there is an excellent result from the first operation and down regulation and although we think we may need to do a bowel resection, we end up doing a “shave”.’

So what might this surgery involve? The truth is that this can be very varied. If the disease is on the outer surface of the bowel, it may be able to be shaved off without disrupting the bowel. However, sometimes the endometriosis penetrates through the surface of the bowel and this can mean cutting out a small area, or, in more difficult cases, actually removing a whole section of bowel. These can be long operations, as Andrew Kent explains. ‘It can be long complicated surgery which requires a certain skill set from all involved, particularly if carried out laparoscopically.’

Consultant colorectal surgeon Mark Potter explains how he plans for operations on bowel endometriosis. ‘You can get a very good idea of what to expect by looking at the MRI scans. The reason for doing the colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, is to get a much better feel of how the bowel is internally. If I do that examination, I can get a lot of information by the feel of the way the camera goes through the sigmoid colon in the bowel – it helps with the mental image that I’ve got from the MRI scan to counsel people as to whether it’s going to be something that we think is going to be straightforward or not.’

So what happens during bowel surgery? This is a meticulous process of dissection, ‘I personally find it mentally taxing,’ says Mark, ‘making progress maybe a millimetre at a time to begin with. When we’re doing cancer surgery, there are a few very clear anatomical landmarks that we go for once we get into the “surgical plane” and then we can get down and we know where we are. We’ve used that same technique with the endometriosis surgery, except that some of those planes, you really lose them because of the inflammatory process. So you can find the normal plane to within two to three centimetres of the endometriosis. So you might have a little gap between safe zones where you’ve just got to make a decision and go for it.’

Whether this means a woman ends up having endometriosis shaved off the outer surface of the bowel, or ends up with a bowel resection, is very specific to her case.

What happens when surgeons come across something they haven’t seen before? Andrew explains: ‘With the complicated or rare conditions in medicine and surgery, you will occasionally come across something new or that you’ve not seen before. This is where two surgeons working together is particularly useful and where your training and experience is important.’

Many women worry about ending up with a stoma (colostomy or ileostomy) from bowel surgery, which is uncommon. A colostomy is where one end of the large intestine (colon) is brought through an artificial opening on the abdomen (stoma), through which faeces flow. An ileostomy is the term used to describe a similar opening from the small intestine, specifically the ileum. A pouch is placed over the stoma to collect what usually passes out through the rectum and anus (see illustration on page xxi). Very occasionally, women have a temporary colostomy as part of their planned surgery, because it has been recognised that it’s necessary to allow the lower bowel to have a period of rest to heal. It is extremely rare to end up with a permanent colostomy after endometriosis surgery.

Thea had a planned temporary colostomy as part of her bowel surgery. ‘They made it very clear that was the procedure because the part of the bowel that I had removed was basically my rectum, so I had to have the bag in order to let that part heal.’ How did she find living with a colostomy? ‘It was bearable because I knew it wasn’t permanent. I knew it wasn’t going to be forever. A lot of people said to me about how I just got on with things. I had it for eight months and then I had it reversed.’

Whether a woman has a stoma or not after bowel surgery, many women talked to us about how it can take a while for the bowel function to settle. The rectum has an important function, to store waste until you can get to a toilet – if you have all or part of the rectum removed, the body needs to adapt to no longer having this part of the bowel. This can result in some changes to bowel habits including:

Whilst these symptoms, which are sometimes referred to as ‘anterior resection syndrome’, can sound quite alarming, they usually settle well over time. This can take up to a year. However, it requires patience and can mean a woman needs to adapt her life around them. Women we spoke to who had undergone bowel surgery for endometriosis talked about how they had to work out which foods exacerbated their symptoms, and which foods helped.

The other aspect of bowel surgery is that it can feel quite isolating. It’s important that women seek advice and support, whether this is from clinicians or from other women who have undergone similar procedures.

Hints and tips for recovering from bowel surgery

Madison had a bowel resection and tells us how she managed afterwards: ‘I changed my diet quite considerably to make it easier on my bowel and recommendations from friends that had gone through similar surgery.’

So what does that diet involve for her? ‘I drink lots more water to keep hydrated to help the bowel move freely and eat plenty of fruit, green vegetables, good amounts of protein and fibre. I avoid starchy pizza, heavy breads. Things that were too heavy, too processed, tended to clog the bowel up and made it almost constipated which then can make you a bit swollen, but if you’re taking care then you can manage what’s going through the bowel, it means that you can live very normally.’

How would Madison describe bowel surgery? ‘Bowel surgery is quite an intense procedure in terms of recovery and it takes quite a few months to recover from, and the learning process of understanding when you need to go to the toilet, the sense of feeling that you need to go to the toilet is very different after the bowel surgery. No one really prepares you for that.’

What has been the impact of this surgery for Madison, both in the early days afterwards and also now, some years on? ‘I remember very clearly not being able to drive very far in the car for the fear of needing the toilet. For the first few months I really was restricted in terms of where I could go and what I could do, and my bowel movement is probably never normal again but it becomes normal to you, the new process of how you go – but you can get through it very well and adapt very quickly to having a new sensation in that region.’

How’s Madison doing now? ‘Although it was emotionally and physically challenging going through the surgery, it’s the best thing that I ever did. I now live a very normal life and often even forget that I had the surgery.’

It’s important to know that every woman’s experience of bowel surgery is unique, and that seeking information and support from your team – that is, your clinicians, as well as your own support network – is vital.

Surgery on the bladder, ureters and kidneys is rare. When endometriosis affects the urinary tract, the organ most commonly affected is the bladder itself.

What can you expect if you have endometriosis on the bladder? Similarly to the bowel, there may be endometriosis on the outside of the bladder, or it may have penetrated through the bladder wall, so surgery can either involve removing a small area of disease or occasionally removing part of the bladder (a resection). Normally when this happens, a catheter will be left in place for several days up to a couple of weeks, to drain the bladder whilst it heals. A catheter is simply a tube, held in place with a small balloon inside the bladder, which drains urine into a collection bag.

If deep disease has affected the ureters, it’s important to assess whether this is affecting one or both kidneys, which is done by performing a CT IVU (CT intravenous urogram). This looks at how the whole urological system is working, and how urine drains from the kidneys through to the bladder. It enables doctors to see if endometriosis is stopping urine draining through the ureters. If there is any blockage, a small hollow tube called a kidney stent may be temporarily inserted under general anaesthetic to help keep the ureters open until surgery can be performed.

Hints and tips on urinary catheters

If you’re going home with a catheter – whether this is due to bladder surgery or to urinary retention following surgery – you’ll be given detailed instructions from the ward, along with any supplies that you need. Here are a few hints and tips:

It can be hard to acknowledge that occasionally, there are complications from surgery. When surgery is more complex and difficult, there is a greater risk of complications – including damage to other organs, such as the bladder or bowel.

However, it is important to note that complications are very uncommon. That said, complications are the surgeon’s biggest concern and it would be wrong to avoid talking about these because although they are rare; they can be life-changing to that person.

It’s important that women experiencing any complication are treated quickly, kept fully informed and supported. It’s also important to note it can be traumatic and emotionally draining, aside from the physical aspects.

I always say listen to your body. The patient knows their body. The women are their own experts in the disease and how it affects them. – Wendy-Rae Mitchell, clinical nurse specialist

Women spoke extensively about ‘joined-up care’ and this, ideally, is what multidisciplinary teams are about. As Amy describes, this is about so much more than surgery: ‘In terms of going to gynaecologists and specialist centres, I haven’t experienced very joined-up support. Information on how to manage it as a chronic condition has always been very lacking. It’s been dealing with the here and now and focusing on this surgery, but not living as best as you can with this disease.’

As a woman with endometriosis about to undergo surgery, you might be asking, do I really need to have this surgery? Is it definitely going to make my pain better? These are difficult questions to answer with a disease that is very specific to each patient, and where little is known about how it progresses. As a result, there is limited reliable information about the effectiveness of surgery for endometriosis.

On the one hand, it is almost impossible to conduct well-designed clinical trials to evaluate the results of surgery. On the other hand, the results of surgery are influenced by endometriosis type and extent, by the experience of the surgeon, and so on.

Nevertheless, based on the evidence from a few key clinical trials, laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis, to remove or ‘destroy’ the disease, is still recommended by national and international guidelines to improve painful symptoms.

Whenever a woman with endometriosis is considering embarking on surgery, we recommend that she should discuss the possible benefits, risks and complications of surgery, the possible need for further surgery (for example, for recurrent endometriosis, or if complications arise), and the possible need for further planned surgery for deep endometriosis involving the bladder, bowel or ureter.

Furthermore, as we discussed earlier, relapse of symptoms may occur after surgery and up to 30 per cent of women end up having further surgery within five years. Some women combine surgery with hormonal treatment (with, for example, the pill) following the operation – it is thought that this may prolong the benefits of surgery and manage symptoms.

Consultant gynaecologist Dominic Byrne explains: ‘If you have a very young patient with relatively severe disease, it may be wiser to tolerate the disease to some extent rather than run the risk of surgery at a very young age. Some of my patients are just teenagers and that will influence the decision. Also the concept of, if you take away minor disease, it prevents it becoming serious disease is not fully accepted because the pathophysiology of endometriosis is not fully understood. Some people think that peritoneal disease and severe disease may actually have a different mechanism of development. In the past, it has been assumed that less severe disease will progress to more severe disease. That may not be true. It may be that severe disease develops more acutely and it has a different pathway and minor disease might fizzle out or change. There is a lack of understanding of the basic science of the pathology, meaning we cannot predict what is going to happen if you do or don’t intervene. That knowledge is missing.’

In Chapter 1 we looked at the myth about hysterectomy being a cure for endometriosis. So why do some women still end up having hysterectomies? Well, perhaps a woman has very heavy periods as well, or fibroids or adenomyosis, or she may have exhausted all other treatment options and have chosen hysterectomy, alongside removal of all visible endometriosis, as the most appropriate option for her.

‘Hysterectomy’ is a term used to refer to removal of the uterus, but there’s more than one type of hysterectomy:

Women with endometriosis would normally have a total hysterectomy, with or without removal of the ovaries, usually laparoscopically, although ultimately the surgery undertaken is highly personalised. All endometriosis lesions should be removed at the same time.

We talked to some women who had either decided to have a hysterectomy or who had chosen not to.

Chloe did not have much choice as she had very severe disease and faced a hysterectomy with a bowel resection: ‘Even up to the week before my hysterectomy, I went to my GP and said, I don’t know if I have fought enough, I don’t know if I have tried enough to have a baby. I will be forever grateful to him for saying to me, you’ve got as much chance of winning the lottery as you have of having your own baby.’

Zoe was not ready to have a hysterectomy, so she chose not to. ‘After I’d seen the clinical nurse specialist and had an internal scan, an MRI and a blood test, the consultant recommended that I have a hysterectomy. This is a very subjective, personal, enormous decision for a woman to make, and for me, at that time, was not something I was ready for.’

Vicki explains how it is hard for colleagues to understand how she is now: ‘I’m a surgeon and I work with surgeons, and we expect people to be better after surgery, that’s the basis of what we do and if you’re going to believe in your job, you have to believe that – and it isn’t necessarily the case. I am better but I’m not right, and I certainly don’t have the energy or the capacity that I used to. I’d say for the first two and a half, three years, I was still having quite a lot of pain of various types and I still take eight Paracetamol a day. I don’t need a TENS machine or heat pads any more, so that’s better. But I do have days where I know that I’ve eaten the wrong thing, and it’s not quite right and I still have problems with sexual intercourse intimacy, so I’m not back to normal. Or even what you might think was normal for 45. You know, biologically I think it’s quite a bit of my body that’s more in its fifties or sixties and I don’t think my colleagues understand that.’

It is a huge decision to make, and Chloe was disappointed that there was no pre-operative counselling for her: ‘I had a pre-op appointment, but one thing that really got me pre-and post-op was that, I know cancer is hideous and I could never imagine how it must feel to lose your breasts, but if a woman has to face losing her breast through a mastectomy, they have counselling, or they are given some support, but there is none of that for a woman who loses her womb.’

Scarlett is making sure that she lives life to the full now. ‘The one thing I promised myself after my hysterectomy was that if I was going to go through with it, I made a deal with myself that I was going to have an amazing life, so I’m just going to take advantage of every opportunity and do everything I can to help myself and everything I can to help other people – that was my promise.’

Women with endometriosis often have lots of questions about the menopause. They will sometimes experience menopause symptoms much earlier than women without endometriosis as a result of surgery, or treatment with GnRH agonists (‘temporary menopause’). Let’s take a look at some of those questions:

A: When you enter the menopause, whether that is naturally, due to drugs or surgically, your hormone levels will change. Natural menopause happens over many years, so hormone levels change slowly and your periods may take a while to stop, whereas with surgery or drugs, your hormone levels change dramatically quite quickly. Most women will experience menopausal symptoms. Some of these can be quite severe and have a significant impact on your everyday activities. Common symptoms include: hot flushes, night sweats, vaginal dryness and discomfort during sex, difficulty sleeping, low mood or anxiety, reduced sex drive (libido), and problems with memory and concentration. If you are below normal menopause age, you’ll normally take HRT to replace some of the oestrogen lost, reduce some of these symptoms and protect your bones against osteoporosis.

A: Endometriosis usually gets better as you enter the menopause. We think that this is a result of markedly reduced ovarian oestrogen production from the ovaries. Scar tissue can, however, be left and so some symptoms may remain.

A: There is not enough evidence to say whether or not endometriosis will come back when using HRT. As HRT contains oestrogen, it could theoretically stimulate any endometriosis but many women take HRT and do not have a recurrence of endometriosis.

A: The lowest possible dose to relieve symptoms should be used. An oestrogen combined with a progestogen (or tibolone) is recommended because of the theoretical risk of ‘unopposed’ oestrogen treatment leading to malignant changes in any residual endometriosis.

A: Menopause experiences are the same as for women who do not have endometriosis.

A: The majority of women who suffer from endometriosis never develop ovarian cancer. Although several studies report a higher ovarian cancer risk, current evidence suggests that the overall likelihood of you getting ovarian cancer at all remains low, so you should be aware, but not be worried, about the impact of endometriosis on your ovarian cancer risk. While 1.3 per cent of women will develop ovarian cancer in their lifetime in the general female population, this proportion is still under 2 per cent in women with endometriosis. Thus, although there is an increase in risk, your lifetime risk remains low and is not appreciably different from women without endometriosis. To put it in perspective, as a female in the general population, your risk of breast (12 per cent), lung (6 per cent) and bowel (4 per cent) cancers are still higher than your risk of developing ovarian cancer. Certain types of ovarian cancer are more commonly associated with a history of endometriosis. These endometriosis-associated cancers tend to be picked up at an earlier stage and carry a better prognosis. There is no clear evidence so far that transvaginal ultrasound and/or blood CA-125 measurements can pick up these cancers early, or that risk-reducing surgery to remove the ovaries can save lives. To reduce your risk of any cancer, women are advised to try to have a balanced diet with a low intake of alcohol, exercise regularly, maintain a healthy weight and not smoke.

A: Endometriosis after the menopause is rare and, if it is suspected, it should be managed in an endometriosis centre. Post-menopausal endometriosis is usually treated by surgery (GnRH agonists and progesterone appear to be ineffective in post-menopausal endometriosis). Aromatase inhibitors are sometimes used to improve symptoms when surgery is not possible, or as a second-line treatment for recurrences following surgery.

A: Your GP can offer treatments and suggest lifestyle changes if you have severe menopausal symptoms that interfere with your day-to-day life. Eating a healthy, balanced diet and exercising regularly – maintaining a healthy weight and staying fit and strong can improve some menopausal symptoms.