Introduction

With the deepening of globalization during the past several decades, educational institutions around the world have been undergoing rapid internationalization. This education internationalization process is reflected in more frequent student and faculty exchange, more cross-region collaborations in joint-degree programs and branch campuses, as well as “importing foreign higher education services and exporting educational programmes abroad” on a larger scale (Huang, 2007, p. 58). Nowhere is this trend of internalization more apparent than the increased cross-border student mobility.

International student mobility, which refers to “international students … taking a full degree abroad or … participating in a short-term, semester or year-abroad program” (Knight, 2012, p. 24) has become an increasingly important part of the global higher education landscape. Between 1990 and 2012, the number of students studying outside their country of citizenship more than tripled (OECD, 2014). The International Consultants for Education and Fairs (2015) reported that approximately five million students studied abroad in 2014, and that, according to the projection made by OECD, there would be eight million students studying abroad by the year 2025. As Jane Knight claims: “[international] student mobility, in its multiplicity of forms, continues to be a high priority of internationalization” (2012, p. 21).

However, in recent years, there have been trends of decline in international student enrollment. Open Doors 2018 reports that the enrollment of new international students has dropped for three consecutive years since 2015 (Institute of International Education, 2018). Behind this decline in international student mobility are a series of anti-globalization movements and events in some countries to reassert national identities. These movements and events, such as the impending British exit from the European Union, President Donald Trump’s “America first” policies, and the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, have fueled tensions and conflicts among nation states and regions, adding uncertainties to the internationalization of education.

Defining International Student

Prior to the 1966–67 survey, a foreign student was defined as a citizen of a country other than the United States, enrolled in an institution of higher education, who intended to return to the home country upon termination of the course of study. Beginning in 1966, the IIE adopted a new definition of foreign student that included all foreign nationals fully enrolled at recognized institutions of higher learning regardless of their visa classification or stated intentions to stay. Beginning with the 1974 survey, the definition was changed again to include only nonimmigrant students (Agarwal & Winkler, 1985, p. 517).

The latest definition used by IIE is more thorough and closer to the definition given by UNESCO: “anyone who is enrolled at an institution of higher education in the United States who is not a US citizen, an immigrant (permanent resident) or a refugee” (as quoted in Kelly, 2012, p. 5). Therefore, one has to be mindful of the diversity in definitions when reading reports prepared by different institutions.

International students crossing national borders are dramatically shaping the cultural, economic, political, and power landscape of the new world order. The Chinese experience offers a particularly enlightening lens into that new order. Drawing on the experience of Chinese students, this chapter provides an overview of international student mobility, with a focus on its trends, reasons, and impacts.

Trends of International Student Mobility

The Uneven Flow of International Students Worldwide

Among the 3.7 million international students who are enrolled at the tertiary level in OECD countries, 56% are from Asia (OECD, 2019). As the largest sending country of international students in the world, China witnessed 662,100 students study abroad in 2018 alone. This number is an increase of 8.83% over the previous year (Ministry of Education, 2019). Between the late 1970s, when China sent out the first dispatch of students overseas after decades of national isolation, and the end of 2015, the total number of Chinese students studying overseas had reached 4.04 million with an average yearly growth rate of 19.06% for nearly four decades (Ministry of Education, 2016). In other words, even though the growth rate of overseas Chinese students has dropped in recent years, the general trend has been upward. On the receiving side, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States together hosted more than 40% of the mobile students who studied in OECD and partner countries (OECD, 2019).

The flow direction of international students is mostly from developing, non-English-speaking countries in the East such as China and India to developed, English-speaking countries in the West such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. According to Perkins and Neumayer (2014), in 2009, the flow of international students from developing to developed countries accounted for 56% of the global total number of mobile students whereas the flow in the other direction only accounted for 0.9%. The other flows were from developed to developed countries (24.6%) and from developing to developing countries (18.3%).

The Flow of Chinese Students to the United States

The largest flow of international students, among the uneven flows worldwide, is from China to the United States. China was the top sending country of international students to the United States in the 1990s and has surpassed India and once again become the top sending country since 2009. The United States has also been the most popular destination for Chinese students in recent decades. In 2017, close to 1.1 million international students enrolled in American colleges and universities, and 363,341 (about 33%) of them were Chinese (Institute of International Education, 2018).

China-US educational exchanges date back to the nineteenth century. Yung Wing (also spelled as Rong Hong, or Jung Hung), who is considered the father of China’s study-abroad movement in the modern era, came to the United States in 1847 at the age of 19. After finishing 3 years of study at the Monson Academy in Massachusetts, he was enrolled at Yale University in 1850. Upon graduating from Yale in 1854, he returned to China immediately in spite of superior job opportunities in the United States. While studying at Yale, he realized that “the rising generation of China should enjoy the same educational advantage that I had enjoyed; that through western education China may be regenerated” (Chu, 2004, p. 7). Thanks to his persevering efforts in convincing the Qing imperial government to send students abroad, the Qing government sent its first dispatch of 30 teenage students to the United States in 1872. For each of the following three consecutive years, another 30 teenage students were sent, making it a total of 120 between 1872 and 1875. This series of state-led action marks the beginning of Chinese students studying overseas on a relatively large scale. We will provide a detailed account of this historical background in Chap. 2 of this book.

Over the next one hundred years or so, China and the United States engaged in intermittent educational exchanges. During the first half of the twentieth century, educational exchanges between the two countries expanded rapidly, and China had sent more students and scholars to the United States than to any other country during the first four decades (Li, 2008). However, this exchange was put to a full stop in the early 1950s due to the breakout of the Korean War. It was not until after 1978, when China opened its door to the outside world after almost three decades of closure, that educational exchange between the two countries resumed. On December 26, 1978, a group of 50 Chinese scholars and scientists, funded by the Chinese government, left for the United States. This marked the beginning of an increasingly active exchange relationship between the United States and China for years to come.

Number of Chinese students in the United States (2000–2014)

Year | 2000–2001 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | 2011–2012 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number (rank) | 59,939 (1) | 63,211 (2) | 61,765 (2) | 62,582 (2) | 81,127 (2) | 127,628 (1) | 194,029 (1) | 274,439 (1) | 304,040 (1) |

% of all international students | 10.9 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 13.0 | 18.5 | 25.4 | 31 | 31 |

% change over previous year | 10.0 | 5.5 | −4.6 | 0.1 | 19.8 | 29.9 | 23.1 | 16.5 | 10.8 |

Top places of origin of international students in the United States (2017–2018)

Rank | Place of origin | 2017/2018 | % of total | % of change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | China | 363,341 | 33.2 | 3.6 |

2 | India | 196,271 | 17.9 | 5.4 |

3 | South Korea | 54,555 | 5.0 | −7.0 |

4 | Saudi Arabia | 44,432 | 4.1 | −15.5 |

5 | Canada | 25,909 | 2.4 | −4.3 |

One noticeable trend is the increasingly young age of Chinese students studying overseas. Among Chinese students studying in the United States, the percentage of undergraduate Chinese students has been growing rapidly and steadily. In 2005–2006, only 14.9% of Chinese students studied at the undergraduate level, and 76.1% at the graduate level. In 2013–2014, the percentage of undergraduate students reached 40.3 while the percentage for graduate students dropped to 42.1. In 2014–2015, the percentage of undergraduate students (41%) surpassed that of graduate students (39.6%) for the first time. Accompanying the increase in the percentage of undergraduate Chinese students in the United States has been a steady decrease in the average age of Chinese students over the years. In fact, an increasing number of Chinese high school students has entered the United States: in 2009 China surpassed South Korean and became the No. 1 sending country of international high school students in the United States. In 2005–2006, only 65 Chinese students came to the United States to attend high school, whereas in 2013, Chinese students accounted for 46% of the 49,000 international students seeking US high school diplomas (Farrugia, 2014). In 2016, the total number of Chinese students studying in American K-12 schools rose to 35,627 (Lew, 2016).

“Parachute Kids”: An Asian Phenomenon

An important contribution this book makes is its inclusion of young Chinese students studying overseas at the secondary level. Those students are often called “parachute kids,” a term education researchers used to describe “unaccompanied minors” (Popadiuk, 2009, p. 230), “unaccompanied sojourners” (Kuo & Roysircar, 2006, p. 161), or “little overseas students” (Tsong & Liu, 2009, p. 366) from Asian regions such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, and mainland China. Very often these students are dropped off in the United States to go to school while their parents stay in their country of origin (Fu, 1994). Parachute kids first emerged in the 1980s, and during the 1980s and early 1990s, the parachute kids phenomenon gained increased media attention partly because parachute kids were predominently from Taiwan (Hamilton, 1993; Zhou, 1998). There was also an upsurge of parachute kids from Hong Kong in the 1990s. These parachute kids from Taiwan and Hong Kong, typically between eight and 18 years old, attended elementary, middle or high school in the United States. They usually stay with family friends or relatives, or live in home-stay arrangements where a host family serves as the paid caretaker (Hsieh, 2007). Families of parachute kids are also known as “astronaut families” or gireogi gah-jok (goose) families in Korean because the parents have to fly frequently between Asia and the United States (Shih, 2016). The reasons for parachuting include the opportunities for better education in destination countries and fierce competition for limited educational resources at home. Although the term “parachute kids” originally refers to overseas students without the company of their parents, increasingly this term has been used interchangeably with “little overseas students.” After all, most of the young overseas students do study abroad on their own, regardless of whether their parents provide onsite care. In this book, the term “parachute kids” is used to refer to the young overseas student population at the secondary level.

Although a large number of these children in the 1980s and 1990s came from Taiwan and Hong Kong, parachute kids from other Asian countries started to gain increased attention in the 2000s. For example, Kang and Abelmann (2011) pointed out that pre-college overseas studies experienced a dramatic increase in the mid-2000s among South Korean students. Compared to parachute kids from Taiwan who tend to come from wealthy and often entrepreneurial families, parachute kids from South Korea represent a wider socioeconomic range (Lee & Friedlander, 2014).

During the past decade, the number of parachute kids from mainland China has been rapidly rising. Interestingly, media portrayals of the parachute kids tend to focus on the “nouveau riche” aspect of those students, such as their squandering of money, spending behaviors and academic unpreparedness (Huang, 2016; Liu, 2015).2 Indeed, Chinese students who have been studying overseas in recent years are very different from their predecessors who embarked on the same journey two decades earlier. An article in Foreign Policy (Liu, 2015) depicts typical Chinese students studying overseas in the 1980s and 1990s this way: They tended to be among “the nation’s best and brightest”; they are usually “… penniless … didn’t go out to dinner, didn’t go to parties, and assumed that American students were all really rich” and they tended to be “idealistic and patriotic.” In less than two decades, the image of humble and diligent overseas Chinese students has transformed drastically and is replaced by the image of the “nouveau riche,” or “the second-generation scion in a wealthy family, who studies abroad in order to return home to run the family business.” They “pay full tuition, often study finance, business management, or economics, and spend their time clustered together”; and they drive luxury cars and go into the city “for extravagant weekend shopping trips” (ibid).

Where Do International Students Go and Why

Push and Pull Factors

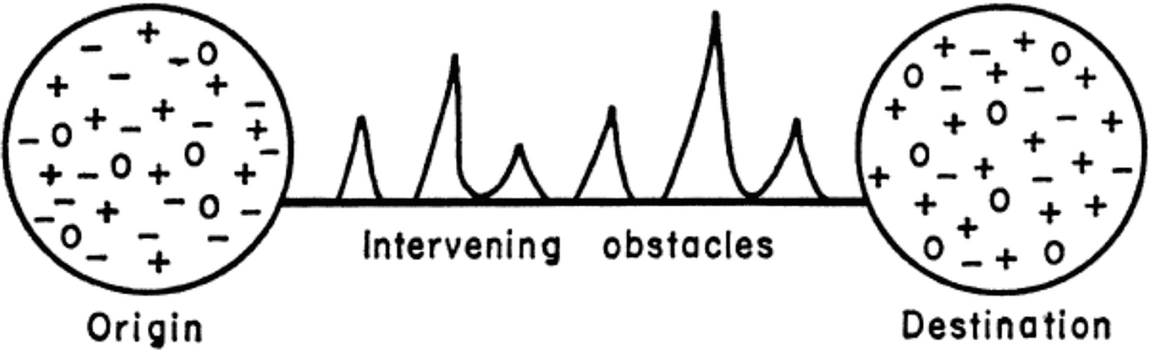

Origin and destination factors and intervening obstacles in migration. (Source: Everett S. Lee, “A Theory of Migration,” Demography, 3 (1966), p. 48)

An improved approach to the basic push-and-pull framework involves distinguishing four groups of factors: (1) push factors in home countries and (2) pull factors in host countries, both of which motivate students to leave their home countries, as well as (3) pull factors in home countries and (4) push factors in host countries, both of which prevent students from leaving their home countries. Tan (2013) regroups the four factors as the following: (1) domestic push factors, (2) external push factors, (3) domestic pull factors, and (4) external pull factors. Students leave their home countries to pursue study in another country when the pushing force exceeds the pulling force. We will provide a more comprehensive review of the push-and-pull framework in Chap. 4. We will further identify the inadequacy of this framework and suggest directions for its improvement in Chaps. 5 and 8.

Push-and-Pull Factors for Chinese Students

For each aforementioned category, push factors in China and pull factors in host countries work together to enable the international mobility of Chinese students. Academically, educational opportunity and educational quality are the most significant factors. First, intense competition in China is an important push factor (Iannelli & Huang, 2014). There has been a rapid expansion of Chinese higher education during the past few decades. College enrollment has steadily risen from 1.66 million in 1980 to 15 million in 2002, with especially substantial increases of 24.31%, 36.78%, and 23.21% for 1999, 2000, and 2001, respectively (Chen, 2002). In 2013, the total enrollment of China’s higher education institutions was nearly 36 million (Ministry of Education, 2015), and the enrollment rate among students between the ages of 18 and 22 reached 37.5%, compared to 15% in 2002 and 3.4% in 1990 (Wu & Lu, 2002). Nonetheless, entering a decent college or university is still competitive and the options of entrance are limited. The National College-Entrance Examination is still the main avenue through which students can access higher education. In 2014, 9.98 million students took the examination, and 9.39 million, or 74.3% of them were admitted (Sina Education, 2015).Academic motives include pursuit of qualifications and professional development; economic motives include access to scholarships, estimated economic returns from study, and prospects for employment; social and cultural factors include a desire to obtain experience and understanding of other societies; and political motives embraced such factors as commitment to society and enhancement of political status and power (p. 795).

The second notable push factor is the dissatisfaction of Chinese students and their families with the higher education system in China. For example, the quality of curricula and teaching methods in China’s higher education system have been considered by Chinese students as “not as advanced and up-to-date as those adopted by higher education institutions in Western countries” (Iannelli & Huang, 2014, p. 808). Corresponding to these push factors in China are pull factors in host countries, such as world-renowned reputation of higher education institutions and their high quality and flexible programs (Azmat et al., 2013; Iannelli & Huang, 2014; To, Lung, Lai, & Lai, 2014). Third, some efforts made by institutions in host countries may serve to pull Chinese students into those countries. For example, the establishment of foundation courses or access courses in China by institutions such as the Northern Consortium UK, which is composed of 11 universities in the United Kingdom, has helped to provide Chinese students with direct access to UK universities (Iannelli & Huang, 2014).

Economically, the rise of China’s economy serves as an indispensable pushing force. Self-sponsored studying overseas used to be a privilege reserved for the few most wealthy and powerful elites in China, but now even many white-collar professionals can afford to send their children abroad. The growing purchase power of these professionals has benefited from improved living standards, accelerated wealth accumulation, skyrocketing real estate price, as well as the overall appreciation of the Chinese currency since the mid-1990s. In spite of the increasing affordability of studying overseas for average Chinese families, its financial cost is still a major consideration for most Chinese families, and thus serves as a push factor in host countries (Azmat et al., 2013). Politically, loosened restrictions on visa and immigration in host countries may serve as a pulling force. Sociocultural factors can serve as both pushing and pulling forces, as demonstrated in existing studies of motivations for mobility among immigrants and international students. For example, Mazzarol and Soutar (2002) listed “the desire to have a better understanding of the Western culture” as a push factor from the home country.

Patterns and Impact of International Student Mobility

Researchers in various disciplines, such as demography, geography, economics and education, have made continuing efforts to gauge the patterns and impact of international student mobility. Some of these scholars have adopted the World System Theory to depict general patterns of the mobility.

Uneven Flow of Students and World System Theory

World System Theory has been used to explain the uneven flow of international students around the world. According to this theory (Wallerstein, 2004), the whole world is a capitalist world-economy system, and countries are divided into three groups based on “the degree of profitability of the production processes” (Wallerstein, 2004, p. 28). These three groups are countries engaged in core-like production processes, countries engaged in peripheral production processes, and semi-peripheral countries that have “a near even mix of core-like and peripheral products” (p. 28). The core countries are developed ones that hold hegemonic political and economic power and they are the origin of products, knowledge, skills, ideology and values.Examples of core countries are the United States and United Kingdom. The peripheral countries are usually underdeveloped ones that receive both physical and ideological products from core countries. Examples of this group include many African and South American countries such as Kenya and Ecuador. Semi-peripheral countries are those between core and peripheral countries and they constantly struggle to move up the hierarchical ladder of world order. Examples of semi-peripheral countries include newly industrialized ones such as China and Brazil. According to the World System Theory, there is an “unequal exchange” between the core and peripheral countries (i.e., strong and weak states) because of the “constant flow of surplus-value from the producers of peripheral products to the producers of core-like products” (p. 28). Furthermore, “[s]trong states relate to weak states by pressuring them to accept cultural practices” such as “educational policy, including where university students may study” (p. 55).

One implication of the World System Theory for international student mobility is that a country’s position in the international student exchange network is highly correlated with its economic and political power and influence. Empirical studies have confirmed this argument: when measuring a country’s influence in the world system by the country’s Gross National Product per capita, scholars found that the higher a country’s position is in the world system, the more central it is in the international student exchange network (Barnett & Wu, 1995; Chen & Barnett, 2000). The fact that an increasing number of overseas Chinese students return to China corresponds to China’s move to the core in the world system. In 2018, the total number of overseas Chinese students who returned to China was 519,400, whereas 662,100 Chinese students went overseas to study in the same year. By comparison, the number of returned overseas Chinese students was only 9121 in 2000, while 32,000 left China for overseas studies during that year. In fact, the number of overseas students returning to China rose by double-digit in recent years. For example, the rate of growth are 46.6% and 29.5% for 2012 and 2013, respectively. Even though the increasing rate dropped to 11.19% and 8% for 2017 and 2018, respectively, the general trend has been upward during the past years and will likely to sustain for years to come (Center for China and Globalization, 2015a, b; Ministry of Education, 2019; New Oriental, 2015).

Further, the rise of Asia as a popular destination for international students indicates that the uneven flow is subject to changes. According to a report by the Bangkok Office of UNESCO, the dominance of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia in the network of student mobility met a challenge as early as the mid-1990s. By the early 2010s, some Asian countries such as China, Singapore, and Malaysia had become competitive destinations for foreign students (Tan, 2013, p. 1).The returned students and scholars play a leading role in areas like education, science and technology, high-tech industries, finance, insurance, trade and management and serve as a driving force for the country’s economic and social development. At the same time, many students and scholars staying abroad contribute in various ways such as giving lectures during short-term visits to China, having academic exchanges, conducting joint research, bringing in projects and investments and providing information and technical consultancy (p. 27).

The changing world system prompts us to rethink the categorization of host countries that was previously theorized under the core-periphery framework. Lasanowaski (2009) divides host countries into four categories based on their share in serving international students worldwide. The first group includes the three “major players”, namely, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. They host around half of all international students worldwide. The second group are the “middle powers” which together host around a quarter of all international students. Countries belonging to this group include Germany, France, and China. The third group is the “shape shifters” which account for around 10% of the world’s overseas students: Canada, New Zealand, and Japan. The fourth group includes the “emerging contenders” which account for more than 5% of the total international student mobility. Countries in this group are Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea, and they mostly host the inflow of students from Asian countries. The position of China and the role of the fourth group in this categorization once again substantiate the increasing importance of Asian countries as destinations of international student mobility.

Economic Impact and the Human Capital Framework

It is widely recognized that receiving and educating international students benefit host countries in multiple ways. As Rogers (1984) notes: “there is a consensus that the presence of foreign students enriches intellectual, cultural and social life” (p. 21). Victor Johnson (2003), a former Associate Executive Director for public policy at NAFSA: Association of International Educators, also acknowledges various benefits international students bring to the United States. These benefits include adding diversity to the student body, providing American students with the first close contact with another culture, filling the under-enrolled science courses and providing crucial academic support by hiring international students as teaching and research assistants. Sir Richard Sykes, a former rector of Imperial College London where a third of undergraduates and about half of postgraduates come from outside Britain, attributes the improvement of academic climate to the presence of large numbers of Chinese students. “The Chinese work bloody hard and drive up the standards,” he says, and “other students see that, and they have to compete” (The Economist, 2010).

Another major rationale for recruiting international students among higher education institutions in host countries is economic benefits. In the majority of countries where data are available, international students pay higher tuition fees at public educational institutions than do domestic students enrolled in the same institutions. As American higher education institutions faced an increasingly restrained budget situation after the 2008 financial crisis, many of them turn to the vast Chinese market for a solution. Let us offer a few examples. In 2011, Zinch China, a consulting company that provides service to American colleges and universities, was asked by the provost of a large American university to help recruit 250 Chinese students in order to fill the university’s budget deficit (Bartlett & Fischer, 2011). Another example involves the University of Delaware, where the majority of international students are from China. In the 2011–2012 academic year, the number of Chinese students at this institution reached 517, whereas this number was only 8 in 2007. In order to address its budget challenges, Oklahoma Christian University has also drastically increased the number of international students from China. This university started recruiting international students in 2007, and a quarter of its current 250 international students came from China.

Since international students are considered an important revenue source, it is no surprise that studies have been conducted to estimate the costs and benefits of international students to local economies. These studies typically employ the human capital framework to estimate the costs and benefits (e.g., Throsby, 1999).

One of the earlier efforts in estimating the economic impact was made by Gruebel and Scott (1966). Their estimates of costs include direct education cost, maintenance cost, and transportation cost. Chishti (1984) includes in his estimates such costs as educational and general expenditures, user cost of capital, and various indirect costs such as maintenance costs of foreign students who receive their allowance from US sources. Benefits included in his estimates are tuition revenue and contribution to aggregate demand because foreign students consume goods and services during their stay in the United States. Moreover, he uses the cost of producing equivalent human capital in host country to estimate the value of embodied capital in non-returnees. He concludes that even though tuition paid by foreign students only covers about 37% of the cost of their education in the United States, benefits for the United States outweigh costs in educating foreign students because there are substantial indirect benefits in terms of human capital gains.

Many other studies analyze direct and indirect costs and benefits at the local, regional, and national levels (Throsby, 1991). The report The Economic Costs and Benefits of International Students, which was produced by the Oxford Economics in 2013, quantifies the costs and benefits of international students in Sheffield to the local economy. Both costs and benefits are divided into three categories, namely, direct (which refers to the economic activity resulting from the direct presence of international students at university), indirect (which consists of activity that is supported as a result of local supply-chain purchases, the additional local procurement resulting from these purchases and so on), and induced (which involves activity that is supported by the spending of those employed as a result of direct and indirect impacts).This report further shows how UK and multiple regions within UK have benefited from educating international students.

Description of the Book

Largely based on data collected through large-scale survey, organization archives and in-depth interviews over the years, this book provides a comprehensive examination of the cross-border mobility of Chinese students. We addresses the questions of which Chinese social groups intend to study overseas, why they want to study overseas, what the impacts of the mobility are on China’s social stratification, and what the challenges are in those students’ adaptation to their lives in destination countries. In this book, Chinese students’ international mobility is examined from both ends, namely, the sending end (i.e., China) and the destination end (e.g., America).

Chapter 2 of the book provides a historical perspective on the international mobility of Chinese students by examining the experiences of Yung Wing, the “father of overseas Chinese students,” and the subsequent two waves of Chinese students going overseas to study in modern history. The first wave includes the 120 “fortunate sons” who studied in the United States between 1872 and 1881; the second wave includes Chinese students going to Japan to study after 1895, and those studying in America on the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship between 1909 and 1940. A common theme runs through this nearly 200-year history of Chinese students studying overseas: How can China become a modern nation capable of competing with the West on the international scene? The high hopes placed upon those students made them susceptible to criticisms and caused the public perceptions of them to pendulate between patriots and traitors, heroes and villains, and vanguard and scapegoat, even though they had paved the way for China’s modernization. This chapter not only presents factual information on those major historical figures and events relevant to studying overseas, but also provides analysis on the impacts of those events on individuals involved as well as the Chinese society at large.

Chapter 3 describes contemporary China and its education system as the context for the international mobility of Chinese students. It presents an overview of the contemporary Chinese society and education system, including the system’s strengths and weaknesses, especially the key characteristic of examination culture. This chapter also provides information on the internationalization of secondary schools in China, especially international programs in key high schools and the increasing popularity of international schools.

Chapters 4 and 5 address the question of which Chinese social group wants to study overseas and why, with the former chapter focusing on quantitative data and latter on in-depth case studies. Applying the push-and-pull framework and using data on 3001 students at 18 high schools located in three Chinese cities, Chap. 4 depicts a comprehensive picture of the Chinese students who intend to study overseas. Extending the quantitative patterns outlined in Chap. 4 and drawing on in-depth interview data, Chap. 5 presents rich stories of three Chinese students who currently study or work in the US. This chapter also makes suggestions for further developing the push-and-pull framework.

Chapter 6 addresses the question of what impacts international student mobility may have on the Chinese society, especially on its social stratification. Through analyzing original survey data from 1,012 ninth graders at 9 middle schools collected in Beijing in 2015, this chapter examines the differential in the choice of and access to such educational resources as studying overseas among different social strata in China. Particular attention is paid to students from those groups which are at an advantage in building networks and mobilizing social resources, namely, high-ranking officials, wealthy business owners, and white-collar professionals. By analyzing how different social strata differ in their willingness and plan to study overseas, this empirical study has shown that studying overseas, which is considered an option for pursuing high-quality educational resources, has proven to be such a tool for advantaged social classes to maintain their status and for disadvantaged social classes to climb up the social ladder.

Chapter 7 examines Chinese students studying overseas from the destination-country side. Based on a research project which collected data through interviews with 15 Chinese students enrolled at a private American high school and 7 teachers who have worked with them, this chapter presents stories of 3 “parachute kids” as in-depth case studies. Those stories demonstrate the challenges they face in the sociocultural adaptation process because of language barrier, emotional problems, and discipline issues, as well as their lack of bonding with parents.

Chapter 8 investigates the education and training industry that provides supplemental education services on study-abroad-related tests, such as Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), Graduate Record Examination (GRE), Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), and International English Language Testing System (IELTS). Breaking away from existing paradigms that either examines the demand or the supply side of overseas studies, this chapter puts the spotlight on test-preparation schools as the “visible hands” behind the ever-growing study-abroad waves in China. This chapter first introduces the social context, development trajectory of this industry and how multiple local niche markets evolved into an integrated industry. Then, this chapter illustrates how these test-preparation schools helped Chinese students acquire indispensable information regarding how to crack the tests and apply for overseas schools. Chapter 8 further shows the ways in which test-preparation schools instilled in students the meaning of study-abroad and boosted the motivation and demand of overseas studies.

Chapter 9 calls on attention to the potential transformational effect of international sojourning experiences. While running the risk of increasing global inequality, transnational mobility provides opportunities for students to build solidarity with each other and instill in them a cosmopolitan spirit.

Concluding Remarks

In studying the main drives behind international student mobility, a mere examination of the political and economic factors is insufficient; the social and cultural factors also have to be taken into consideration. Here, Bourdieu’s frameworks of social and cultural capital can provide the lenses through which we can discern the systematic trends behind international student mobility. Bourdieu (1986) divided capital into three categories: (1) economic capital, “which is immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the form of property rights” (p. 243), (2) cultural capital, which can exist in three forms, namely, “the embodied state” (i.e., culture and cultivation), “the objectified state” (i.e., material objects and media, such as writings, paintings, monuments, and instruments), and “the institutionalized state” (i.e., institutional recognition such as academic qualifications), and (3) social capital, which refers to “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition … which provides each of its members with the backing of the collectivity-owned capital” (pp. 248–249). Bourdieu further notes that cultural and social capital are convertible to economic capital under certain conditions. Cultural and social capital are highly relevant and appropriate for the study of international student mobility because of the central role of academic qualifications and educational credentials in the mobility process.

In fact, in addition to examining the migration of students across countries or regions from a human capital perspective—which implies that going to another country to study is considered an investment and the motive is to have better job opportunities and thus higher expected income in the future—cross-border migration of international students may also be viewed as a consumption choice. In that case, students not only consider the returns to their educational investment, they also consider the circumstances and the place where they will study (Beine, Noel, & Ragot, 2013).These benefits include the quality of instruction and research, higher expected lifetime income, the prestige of a foreign degree (especially a graduate degree from an American university), and international contacts that may facilitate future business dealings, travel, or research. In addition, there are the benefits of living in another culture during a student’s educational experience (p. 514).

In addition, studies of international student mobility need to look at both the benefits and the potential negative impacts of mobility. Globalization can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it could potentially make the world flat (or less uneven) by providing opportunities for all countries to participate in economic activities, thanks to advancement in technology and communications. Asia seems to be the main beneficiary of globalization. Asian countries and regions that have benefited include China and the “Four Little Tigers” of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. On the other hand, globalization can increase inequality—both within countries and among countries, and weakens cultural diversity, as demonstrated by the stagnant development of Latin American countries and worsened situation of African countries.

Stiglitz (2006) confirms this controversial role of globalization by conducting a systematic comparison between Latin American and African countries on one hand and Asian countries on the other hand. He demonstrates that Latin American countries have been harmed by the Washington Consensus and African countries have been bypassed by globalization due to their colonial heritage, lack of infrastructure, and the AIDS epidemic. In contrast, Asia has managed to make globalization work for them mainly because of their strong governments. Despite being one of the major beneficiaries of globalization, China has paid enormous price: environmental destruction, exploitation of labor, and loss of traditional values/lifestyle to some extent.

This book also calls for closer scrutiny of other controversial issues in international student mobility. These issues include, but are not limited to, diploma mill, phony universities, and the use of educational agencies for recruiting international students. An example of diploma mill is Dickson State University in North Dakota which awarded 4-year degrees to 400 international students who did not fulfill all the graduate requirements (Fischer, 2012).

Another example of this kind involves fraud and crime. In November 2014, Susan Xiao-Ping Su, president and chief executive of Tri-Valley University, was sentenced to 16 years in prison for student-visa fraud, harboring undocumented immigrants and other charges. Federal agents raided this California-based institution in January 2011 because of complaints accusing the university of admitting international students so that they could stay in the United States on student visas while not having to attend classes (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2014). Even worse, a 2011 Chronicle of Higher Education investigative report suggested that Tri-Valley University was only the tip of the iceberg, and similar unaccredited institutions, which exploit loopholes in visa to make money off international students, flourish in states such as California and Virginia where regulations are lax (Bartlett & Fischer, 2011).

International student mobility, like globalization, can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, as part of the worldwide population migration, cross-border mobility among students is affected by the world order and its political and economic forces. This indicates that inequalities among countries may be further increased by the uneven flow of international students, and “brain drain” remains a bleak reality for many developing countries. On the other hand, as a unique kind of population migration, international student mobility can exert influence on the world order due to the transformational function of education and the agency within each individual. Countries are often proactive in making the inflow and outflow of students work in their favor.