From NORM by-products to building materials

J. Labrincha*,a; F. Puertas†,a; W. Schroeyers‡; K. Kovler§; Y. Pontikes¶; C. Nuccetelli**; P. Krivenko††; O. Kovalchuk††; O. Petropavlovsky††; M. Komljenovic‡‡; E. Fidanchevski§§; R. Wiegers¶¶; E. Volceanov***,†††; E. Gunay‡‡‡; M.A. Sanjuán§§§; V. Ducman¶¶¶; B. Angjusheva§§; D. Bajare****; T. Kovacs††††; G. Bator††††; S. Schreurs‡; J. Aguiar‡‡‡‡; J.L. Provis§§§§ * University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

† Eduardo Torroja Institute for Construction Sciences (IETcc-CSIC), Madrid, Spain

‡ Hasselt University, CMK, NuTeC, Diepenbeek, Belgium

§ Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

¶ KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

** National Institute of Health, Rome, Italy

†† Kiev National University of Construction and Architecture, Kyiv, Ukraine

‡‡ The University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

§§ Ss Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Skopje, Macedonia

¶¶ IBR Consult BV, Haelen, Netherlands

*** Metallurgical Research Institute - ICEM SA, Bucharest, Romania

††† University POLITEHNICA Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

‡‡‡ TUBITAK MRC, Kocaeli, Turkey

§§§ Spanish Institute of Cement and its Applications, Madrid, Spain

¶¶¶ Slovenian National Building and Civil Engineering Institute (ZAG), Ljubljana, Slovenia

**** Riga Technical University, Riga, Latvia

†††† University of Pannonia, Veszprém, Hungary

‡‡‡‡ University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

§§§§ University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom

a Two equal first authors: coordinators of this chapter.

Abstract

The cementitious materials and ceramic industries are frequently looked as targets for the recycling and valorization of several wastes, residues, and by-products, generated from a wide variety of industries. In general, only technical (and chemical) aspects are covered on each attempt for recycling a waste in a particular product, while radiological features are rarely considered. This chapter aims to give new and more complete insights on the recycling of several industrial wastes, on four groups of construction materials: (1) construction materials based on Portland cements (both as cement itself and as concrete), (2) construction materials based on alkali-activated binders, (3) ceramics and glass-ceramics, and (4) gypsum.

For each by-product a separate section will describe (1) the technical (and chemical) aspects of the use as part of a construction material and (2) the resulting radiological properties of the designed product, when they are available.

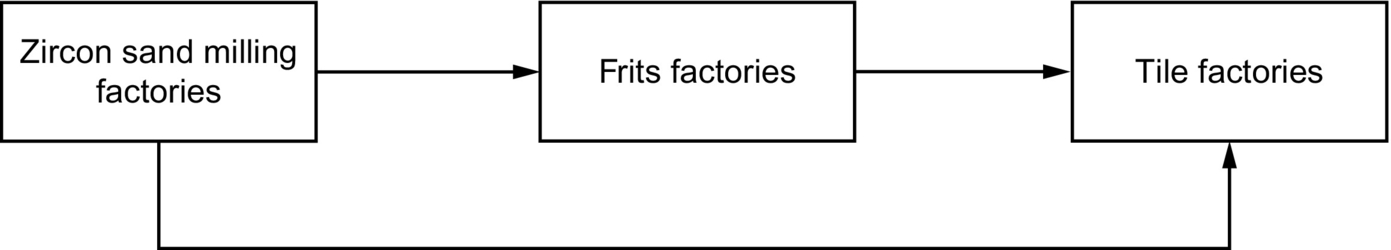

Some ceramic industries also use radiologically active components, namely zircon and zirconia (in glazes, refractories, etc.). The radiological consequences of their production, further use/manipulation by other industrial sectors (e.g., ceramic glazes and frits production), and on the final costumers are also briefly reported.

Keywords

Cement; Concrete; Geopolymer; Ceramic; Phosphogypsum; Activity concentration index; By-product recycling

7.1 Introduction

7.1.1 Recycling of industrial by-products in building materials

The cementitious materials and ceramics industries are excellent targets for the recycling and valorization of some wastes, residues, and by-products, from a wide variety of industries.

Given the environmental challenges inherent in Portland cement manufacture (high thermal and electrical energy demand, need to quarry large quantities of limestone and clay and the emission of greenhouse gases, especially CO2), the study and development of cements based on the reuse of waste of varying origin is a priority line of research and technological innovation in the pursuit of industry sustainability. A broad range of types of waste can be used in blends with Portland cements, representing an environmentally friendly and clinker-saving way of production.

Of the 27 types of cement listed in the European Standard EN 197-1:2011 (Sanjuán and Argiz, 2011), 26 contain some manner of mineral addition which can include industrial residues such as siliceous or calcareous fly ash, blast-furnace slag, or silica fume. All of the aforementioned additions are industrial by-products and dependent on the content of natural radionuclides some of them are listed as naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORMs). The trend of industrial by-product recycling is expected to continue. The draft of the common cements standard prEN 197-1:2016 includes five new cement subtypes with higher amounts of by-products; in particular, siliceous fly ash and blast-furnace slag. In addition to the earlier, new potential cement constituents are being explored, such as ground coal bottom ash, paper sludge ash, silicon-manganese slag, copper slag, and so on (Argiz et al., 2013; Vegas et al., 2006; Sabador et al., 2007; Frias et al., 2006; García Medina et al., 2006; Siddique, 2003).

Industrial waste and by-products are used not in blends with Portland cement, but may also be added during clinkerization itself, partially or totally replacing the virgin raw materials in the raw meal (limestone in particular) or contributing as secondary fuel. Very different types of waste or by-products can be used as partial raw meal replacements, including crystallized blast-furnace slag (Puertas et al., 1988), waste from the manufacture of clay-based products (Puertas et al., 2010), aluminum recycling (Paval) (Blanco-Varela et al., 2000), etc. Efforts are also being made to use alternative fuels in OPC production: in countries such as the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, and Norway, these fuels account for over 60% of the total. The sources vary widely in nature, including shredded tires, solvents, water treatment plant sludge and used oil, among others (Pontikes and Snellings, 2014).

Another avenue for manufacturing eco-efficient cements is the development of new materials wholly different from ordinary Portland cement. Due to their mechanical and durability properties, versatility alkali-activated cements (also known as geopolymers) are among the most prominent of these new materials (Palomo et al., 2014). These cements are defined as the binders resulting from the chemical interaction between alkaline solutions and natural (clay; possibly thermally treated) or the result of human activity (industrial waste or by-products) aluminosilicates with a high- or low-Ca content, possibly having also Fe. Alkaline activation calls for two basic components: (1) a solid precursor that is prone to dissolution (most often amorphous or vitreous) and (2) an alkaline activator. The aluminosilicates may be natural products such as metakaolin or industrial by-products such as blast-furnace slag or aluminosiliceous fly ash. The alkaline solutions able to interact with aluminosilicates to generate such new binders include alkaline metal or alkaline-earth hydroxides (ROH, X(OH)2), weak acid salts (R2CO3, R2S, RF), strong acid salts (Na2SO4, CaSO4·2H2O), and R2O(n)SiO2-type siliceous salts known as waterglass (where R is an alkaline ion such as N, K, or Li). From the standpoint of end product strength and other properties, the most effective of these activators are NaOH, Na2CO3, and sodium silicate hydrate (waterglass). Industrial by-products are presently also being studied for use as possible alkaline activators. Patents have been awarded for the use of industrial waste or by-products such as ash from rice husks, silica fume, and urban and industrial vitreous waste as potential alkaline activators to replace the family of substances known as water glass (Puertas and Torres-Carrasco, 2014). Here also, the main components of these cements may be NORMs.

The foregoing is indicative of the high potential for reuse and valorization of industrial waste and by-products in the manufacturing of cement and other construction materials. To be apt for such purposes, the waste must exhibit certain chemical, physical, and microstructural characteristics that favor their reactivity and behavior. Next to the binder described so far, the aggregates to be used for mortar and concrete production can also be residues and NORM in particular. Considering that they could be used in a proportion close to 80% in concrete volume, they might have a substantial contribution in the concentration of radionuclides in the final building materials.

The main ceramics which are produced using raw materials that can contain enhanced concentrations of natural radionuclides are refractories as well as tiles in which zirconia (the main source of natural radionuclides) is mixed with other constituents. In refractories, the applications cover the production of either prefabricated units (bricks) or the use as a mortar for in situ applications, for example, in kilns. Not every zirconia can be considered as NORM and in some cases only smaller amounts of zirconia are used, hence, not every refractory has enhanced levels of natural radionuclides. This is controlled by the composition of the refractory, which depends on the required properties in terms of temperature, chemical corrosive circumstances, and whether abrasion is an issue. Refractories with enhanced levels of natural radionuclides can be found in the glass industry (kilns) and sometimes in the ceramic brick or tiles kilns. Zirconium is also a common opacifier of ceramic glazes. In general, the glazes show activity concentrations below 1 kBq/kg for the main natural radionuclides, and only their production deserves control.

Other areas where significant amounts of by-products, such as fly ash, mining tailings, etc., are incorporated are clay-based formulations, ceramic bricks for example. Despite the often notable amount of by-products employed, the concentration of natural radionuclides in such ceramic materials is, in general, similar to that of common ceramic bricks.

7.1.2 Radiological consideration for recycling of industrial by-products in building materials

As discussed in Chapter 4, in Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom a reference level of 1 mSv/year is applied to indoor external exposure to gamma radiation emitted by building materials, in addition to outdoor external exposure (EU, 2014). Therefore, Member States shall ensure that the activity concentrations of the radionuclides are determined (control the external exposure with respect to the reference level) before the materials listed below are placed on the market for use in buildings:

(b) Building materials or additives of natural igneous origin, such as:

• granitoides (such as granites, syenite, and orthogneiss);

• porphyries;

• tuff;

• pozzolana (pozzolanic ash); and

• lava.

(2) Materials incorporating residues from industries processing NORM, such as:

• phosphogypsum;

• phosphorus slag;

• tin slag;

• copper slag;

• red mud (residue from aluminum production); and

• residues from steel production.

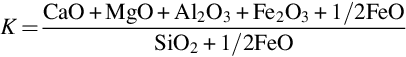

To comply with the Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom requirements Member States shall arrange control measures with regard to their emitted gamma radiation. For screening and evaluation of building materials the Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom uses an activity concentration index (IBSS):

where CRa-226, CTh-232, and CK-40 are the measured activity concentrations (Bq/kg) for, respectively, 226Ra, 232Th, and 40K (EU, 2014).

The activity concentration index and the legislative aspects are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4. It needs to be kept in mind that the activity concentration index is only a screening parameter. In case a value of IBSS>1 is found for a given building material, then it needs to be verified that, upon use in a building, the exposure to gamma radiation is less than the reference level of 1 mSv/year (which is the real criterion for evaluation of building materials). In this chapter the activity concentration index proposed by the Council Directive is used to screen the content of natural radionuclides in several building materials.

The activity concentration index is used only for building materials (or for their constituents if the constituents are also building materials) (EU, 2014). In this chapter (and in Chapter 6) also the “activity concentration index for by-products” is considered, but this purely for the purpose of dilution calculations in order to support the discussion of building materials incorporating a given by-product. Using an “activity concentration index for by-products” would in theory mean that the by-product itself is used (for 100%) as a building material which for most by-products is an unrealistic scenario. In this way the extreme case of NORM by-product incorporation in building materials is discussed. The reported activity concentration indexes are calculated on the basis of the activity concentration for 226Ra, 232Th, and 40K from different literature references. The original values for these activity concentrations are also reported in Chapter 6.

The overall radiation hazard due to ionizing radiation from building materials includes both a gamma radiation component, which depends on their radionuclides content, and a component caused by their radon exhalation. However, most of the standards in the world, which regulate radioactivity of building materials, address the gamma radiation only, and do not require even to test the product for radon exhalation. The evaluation of the excess dose caused by building materials for the radon pathway is indeed rather complicated (Markkanen, 2011). One of the reasons is that the actual correlation between the monitored quantity and radon exhalation rate measured in laboratory and the excess indoor radon concentration on site might be rather poor. Numerous factors, such as temperature (both indoors and outdoors), air pressure and humidity fluctuations, total porosity, pore distribution and pore type (open or close), surface treating done at the building site or type of the coating material applied, influence significantly radon exhalation in dwellings. Finally, it is extremely difficult to take into account the effect of the inhabitant behavior influencing directly air exchange rate in living spaces. That is why most of the standards regulating radioactivity of building materials address the radon exhalation in a very simplified form—through the limitation of 226Ra—the precursor of 222Rn in the 238U radioactivity chain (Kovler, 2011). At present only two national standards (Austrian Standard ÖNORM S 5200 and Israeli Standard SI 5098) address radon exhalation from building products, considering 226Ra activity concentrations, radon emanation coefficient, density and thickness of the product. The detailed review of the standards regulating natural radioactivity of building materials is available in Chapter 4.

In reality, typical excess indoor radon concentration due to building materials is low: not higher than 20 Bq/m3 (Kovler, 2009), which is only 7% of the reference value introduced in the Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom (300 Bq/m3). In other words, radon cannot “compete” by its contribution with the underlying soil, which is correctly considered the most important source of indoor radon. At the same time, the building materials may also be an important source. For example, about 300,000 dwellings with walls made of lightweight concrete based on alum shale (the so-called “blue concrete”) were built between 1929 and 1975 in Sweden (Mjoenes and Aakerblom, 2001). The radon concentrations in these houses can reach 1000 Bq/m3 under low ventilation rate, while the building occupants can get an annual effective dose of 4 mSv/year—only from building material. In addition, the main part of indoor radon at the upper floors of a building originates also from building materials.

The Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom does not provide a guideline that deals separately with the radon exhalation/emanation from only the building materials. In Article 74, dealing with indoor exposure to radon, member states are expected to “promote action to identify dwellings, with radon concentrations (as an annual average) exceeding the reference level” (300 Bq/m3). In other words, radon is regulated at the level of dwellings and no distinction is made between the building materials and the soil as sources of radon. Radon exhalation/emanation is dealt with in this chapter when information is available.

7.2 Portland cement and concretes

7.2.1 Introduction

The beneficial utilization of some industrial by-products in improving the technical, environmental, and cost profiles of fresh and hardened concrete is recognized. By-products such as coal fly and bottom ash, silica fume, and ground-granulated blast-furnace slag are well-known cement constituents in blended cements and also can be added in different proportions to concrete as mineral admixtures. Some others, such as copper slag and coal bottom ash, are being used mainly as concrete aggregates.

New by-products and waste materials are being generated by various industries and the disposal of these residues raises sustainability questions. The use of some waste materials in the cement and concrete industry is a promising alternative.

7.2.2 Coal fly ash

7.2.2.1 Technical properties

The recycling of fly ash (in particular, in concrete construction) has become increasingly important in recent years due to increasing landfill costs and current interest in sustainable development. Coal fly ash is a well-known cement constituent and concrete additive (Argiz et al., 2015; Kovler, 2017). A lot of information can be found at the website of the ECOBA (European Fly Ash Association): Fly ash was successfully used in concrete around the world for the last 50 years. In the United States more than six million tons and in Europe more than nine million tons are used annually in cement and concrete.

Coal fly ash is classified into two main groups: class F and class C fly ash. When the sum of SiO2+Al2O3+Fe2O3 is higher than 70 wt% they are classed as F-type. If not, then they belong to class C (Argiz et al., 2015). In both cases, fly ash consists of fine particles that could contain some heavy metals and natural occurring radionuclides. Its management remains a major challenge all over the world. However, the utilization of fly ash is technically feasible in the cement industry. There are essentially two main applications for fly ash in cement production, (1) first as a raw material to produce Portland clinker and (2) second as a mineral or pozzolana addition. Fly ash can be added to the Portland cement clinker as a pozzolanic constituent in the production of CEM II, Portland-composite cement, CEM IV, Pozzolanic cement or CEM V, Composite cement. Table 7.1 shows the ten cement types according to the European Standard EN 197-1:2011, which are CEM II/A-V, CEM II/B-V, CEM IV/A, CEM IV/B, CEM V/A, and CEM V/B, the amount of fly ash in the cement goes from 6% to 55% (6%–20%, 21%–35%, 11%–35%, 36%–55%, 18%–30%, and 31%–49%, respectively). Incorporation of high amounts of fly ash leads to a decrease in the early strength of cement due to the early low reactivity of fly ash, which could be improved by grinding.

Table 7.1

Fly ash in common Portland cements with K, Clinker; S, Slag; D, Silica Fume; P, Natural Pozzolan; Q, Industrial Pozzolan; V, Siliceous fly ash; W, Calcareous fly ash; T, Burnt Shale; L and LL, Limestone (in LL TOC content ≤0.20 wt% and in L TOC content ≤ 0.50 wt%)

| Main types | Designation | Composition (wt%) | |||||||||||

| Main constituents | |||||||||||||

| Clinker K | S | D | Pozzolan | Fly ash | T | Limestone | Minor constituents | ||||||

| P | Q | siliceous V | calcareous W | L | LL | ||||||||

| CEM II | Portland-fly ash cement | CEM II/A-V | 80–94 | – | – | – | – | 6–20 | – | – | – | – | 0–5 |

| CEM II/B-V | 65–79 | – | – | – | – | 21–35 | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| CEM II/A-W | 80–94 | – | – | – | – | – | 6–20 | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| CEM II/B-W | 65–79 | – | – | – | – | – | 21–35 | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| Portland-composite cement | CEM II/A-M | 80–94 | <- - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6–20 - - - - - - - - - - - - - -> | 0–5 | |||||||||

| CEM II/B-M | 65–79 | <- - - - - - - - - - - -21–35 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -> | 0–5 | ||||||||||

| CEM IV | Pozzolanic cement | CEM IV/A | 65–89 | – | <- - - - - - - 11–35 - - - - - - - - -> | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||||

| CEM IV/B | 45–64 | – | <- - - - - - - - 36–55 - - - - - - - -> | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||||||

| CEM V | Composite cement | CEM V/A | 40–64 | 18–30 | – | <- - - - 18–30 - - - -> | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| CEM V/B | 20–38 | 31–50 | – | <- - - - 31–50 - - - -> | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||||

The use of coal fly ash in blended cements is increasing because it improves some properties of concrete (Argiz et al., 2015). The pozzolanic activity of coal fly ash contributes to increased strength at later ages when the concrete is kept moist. In addition, it leads in general to a lower water demand of the concrete for a given workability. This means a decrease in the water-cement ratio and capillary porosity and reduces bleeding. It also provides a low heat of hydration which is recommended in mass concrete applications to minimize cracking at early ages. Finally, coal fly ash cement in concrete means less concrete permeability as a result of producing a dense material. Given that, it provides a high-concrete resistance to sulfate ions attack, chloride ingress into the concrete, frost-thaw cycles, and alkali-silica reaction.

Typical applications of concretes made of coal fly ash cements are roller compacted concrete (RCC), which is a wide spread practice, such as in roads and dams' construction, road subbase, and soil stabilization. Also, coal fly ash has been employed as a lightweight aggregate in construction, an aggregate filler, a bituminous pavement additive, and a mineral filler for bituminous concrete (Blanco-Varela et al., 2000).

Some concrete plants produce concrete with coal fly ash as a mineral additive replacing partially Portland cement (because of pozzolanic properties of fly ash contributing in strength and durability of concrete). European Standard EN 206-1 regulates the replacement of cement with fly ash. For example, 1 kg of cement can be replaced by 2.5 kg of fly ash keeping the durability-related properties (or strength) of concrete unchanged. At the same time, the standard sets a maximum limit for such replacement, because pozzolanic reaction of fly ash occurs only, if calcium hydroxide, which is one of the products of cement hydration, is available. In other words, a presence of a minimum content of cement to trigger pozzolanic reaction of fly ash is vital. EN 206-1 allows replacing maximum 33% and 25% of cements CEM I and CEM II, respectively. If a greater amount of fly ash is used, the excess shall not be taken into account for the calculation of the replacement of cement.

Except a part of cement, fly ash can successfully replace also a part of sand, namely—its fine fraction. The partial replacement of sand in concrete becomes especially important nowadays for several countries, which suffer from the lack of high-quality quartz sand. Fly ash as a replacement of fine sand improves workability and pumpability of fresh concrete mixes. As a partial replacement of sand, fly ash can be introduced in normal-weight concrete mixes by much larger amount, than replacement of cement.

The total content of fly ash in normal-weight concrete mix at the level of 120 kg/m3 is typical, although high-volume fly ash (HVFA) concrete compositions, which were introduced in order to maximize recycling of fly ash in concrete construction, are known (ACI, 2014). LEED (the abbreviation of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) promotes the use of HVFA concrete, which contains up to 40% of fly ash in cement or concrete (PCA, 2005).

The following example adapted from Kovler (2011) demonstrates a typical replacement of both cement and sand by fly ash. Two concrete mixes, the reference concrete and concrete containing 120 kg/m3 of fly ash as a partial replacement of both cement and fine aggregates, are manufactured in the same concrete plant from the same raw materials—Portland cement and aggregates. Concrete compositions are shown in Table 7.2. In this example 30 kg/m3 of cement is replaced with 30×2.5=75 kg/m3 of fly ash, while the rest of fly ash (120–75=45 kg/m3) replaces a part of sand. Total content of fine materials (cement+fly ash) in this concrete mix remains constant, which guarantees the same consistency of fresh concrete at the given water content. With this replacement the main properties of concrete in both fresh and hardened states are assumed to perfectly meet the design specifications.

Table 7.2

Example of mix design for concrete with and without fly ash (kg/m3)

| Raw materials | Reference concrete | Concrete with fly ash |

| Cement | 300 | 270 |

| Coarse aggregates | 1200 | 1200 |

| Fine aggregates | 700 | 610 |

| Fly ash | – | 120 |

| Water | 150 | 150 |

| Total | 2350 | 2350 |

A clear trend is observed in the last years in construction field: the concrete grade gradually increases, because of the need to design buildings and structures for higher loads (e.g., high-rise buildings, bridges, public buildings with large span, etc.), while economizing raw materials, which results in selecting thinner cross-sections for load-bearing elements. This trend results in a gradual increase in the content of cementitious materials. These materials contain often supplementary cementitious materials, such as coal fly ash. In parallel, the uses of coal fly ash in concrete mixes as a partial replacement of either cement or sand (or both) become more and more versatile. Considering this trend, the following typical compositions seem to serve as better basis for estimating the radiological properties of modern concrete.

In Table 7.3 a typical mix design for different modern concrete compositions with and without fly ash is given. This example will be further discussed in the discussion of the radiological aspects.

Table 7.3

Example of mix design for modern concrete compositions with and without fly ash (kg/m3)

| Raw materials | Reference concrete (no FA) | Concrete containing FA as partial replacement of sand | Concrete containing FA as partial replacement of cement and sand | HVFA (high-volume fly ash) concrete |

| Cement | 400 | 360 | 320 | 160 |

| Coarse and fine aggregates | 1850 | 1800 | 1750 | 1700 |

| Fly ash as a partial replacement of cement | 0 | 0 | 50 | 40 |

| Fly ash as a partial replacement of sand | 0 | 90 | 80 | 180 |

| Water | 150 | 150 | 150 | 140 |

| Total | 2400 | 2350 | 2350 | 2220 |

7.2.2.2 Radiological properties

Coal fly ash acts as a source of gamma radiation in concrete due to the presence of the radionuclides 226Ra, 232Th, and, to a lesser extent, 40K. An overview of the activity concentrations of 226Ra, 232Th, and 40K in coal fly ashes produced in several countries is given in Chapter 6. Several authors (Kovler, 2012; Kovler et al., 2005; Chinchón-Payá et al., 2011) measured relatively higher levels of natural occurring radionuclides in coal fly ash, which is currently used in Portland cements and concretes. By contrast, the radon exhalation is controversial because of the low emanation coefficient from the coal fly ash particles, which are generated under high temperatures in coal-firing thermal plants at the process of coal combustion (Kovler et al., 2004). The coal fly ash particles have dense glassy structure, which prevents radon atoms from escaping into the surrounding cement matrix. In spite of the fact that coal fly ash participates slowly in pozzolanic reaction, and then may contribute in radon emanation, like the resulting calcium silicate hydrates, this is neutralized by the strengthening of the overall structure of cementitious matrix, which is accompanied by lowering density and reduction of radon exhalation rate of concrete with time. Drying of concrete in time is another factor reducing radon exhalation of Portland cement—fly ash concrete. These processes are described and discussed in detail by Kovler (2012).

The concentration of natural radionuclides in the resulting Portland cement will be decreased (relative to the material of origin the coal fly ash) since depended on the type of Portland cement (see Table 7.1) only a limited percentage of fly ash (up to 55 wt% of fly ash for pozzolanic cement) can be used. Therefore, recycling of coal fly ash in blended cements can have high environmental and safety advantages.

For estimating the values of I-index calculated by Eq. (7.1) of typical concrete compositions containing coal fly ash, typical activity concentrations reported by Trevisi et al. (2012) for Portland cement and European average soil (as the first approximation of the aggregates, both coarse and fine) are used. As far as coal fly ash is concerned, the minimum and maximum I-indexes (reported for coal fly ash in Chapter 6) will serve as a good assumption representing the variability of the radiological properties of this by-product.

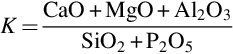

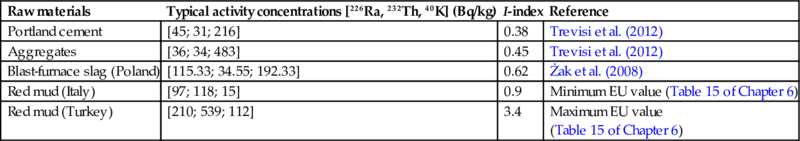

As clearly stated in the Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom, the index should apply to the building material (concrete in our case), and not to its constituents (unless the constituents are also building materials), such as cement, aggregates, or coal fly ash. At the same time, I-index values for concrete constituents calculated by Eq. (7.2) make calculation of the overall I-index of concrete easier. Typical activity concentrations of concrete constituents for the calculation of the I-index value of modern concrete compositions containing coal fly ash are given in Table 7.4.

Table 7.4

Typical activity concentration index for concrete constituents in modern concrete compositions containing coal fly ash

| Raw materials | Typical activity concentrations [226Ra; 232Th; 40K] (Bq/kg) | I-index | Reference |

| Cement | [45; 31; 216] | 0.38 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Aggregates | [36; 34; 483] | 0.45 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Coal fly ash (Ireland) | [26, 11, 70] | 0.2 | Minimum value (Table 3 of Chapter 6) |

| Coal fly ash (Greece) | [469; 40; 349] | 2.2 | Maximum value (Table 3 of Chapter 6) |

The I-index calculation is based on European Commission 1999; Radiation Protection 112; Radiological Protection Principles Concerning the Natural Radioactivity of Building Materials; and Directorate-General, Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection.

Note that the I-index, as proposed by Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom, is only used for building materials or for their constituents if the constituents are also building materials: An I-index given for a by-product or cement makes the unrealistic assumption that 100% of the by-product or cement is used as a building material.

The activity concentration index of the hydrated Portland cement-based concrete is slightly lower than in the anhydrous form because of the presence of water (Puertas et al., 2015a,b).

The results of the I-index calculation of modern concrete compositions containing coal fly ash are given in Table 7.5.

Table 7.5

I-index of modern concrete compositions containing coal fly ash

| Raw materials | Reference concrete (no FA) | Concrete containing FA as partial replacement of sand | Concrete containing FA as partial replacement of cement and sand | HVFA (high-volume fly ash) concrete |

| Maximum activity of fly ash (I=2.2) | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.59 |

| Minimum activity of fly ash (I=0.2) | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.39 |

Taking into account that HVFA concrete is mainly used in infrastructure, but rarely applied in dwellings and other inhabited buildings, we can conclude that the I-index unlikely exceeds half of the control value (I=1). In other words, the introduction of coal fly ash into concrete mix does not lead to significant increase of gamma doses. In parallel, radon emanation of concrete, especially in the mixes containing coal fly ash as a partial replacement of sand, is usually reduced, compared with the reference concrete (Kovler, 2012, 2017). Therefore, recycling of coal fly ash in concrete construction does not represent a radiological concern.

7.2.3 Coal bottom ash

7.2.3.1 Technical properties

Coal bottom ash is generated together with fly ash in the boiler of coal-fired power plants. Therefore, its chemical composition is in many cases quite similar. However, as discussed in Chapter 6, there are important differences related to the concentrations of the incorporated trace elements, such as the naturally occurring radionuclides of concern. In addition, there are important differences in the concentrations of (partly-) volatile species, for example, alkali metals.

Most of the scientific papers published regarding studies performed on coal bottom ashes suggest its use as artificial aggregates in road bases (Churcill and Amirkhanian, 1999) and only few attempts deal with their pozzolanic properties in blended cements (Cheriaf et al., 1999; Argiz et al., 2013; Bajare et al., 2013; Bumanis et al., 2013).

7.2.3.2 Radiological properties

For the use of coal fly ash as an aggregate in road bases currently (Jan. 2017), no European directives exist. Therefore, there are no limitations from a radiological point of view in most European Member States.

In some member states, like in Sweden, a specific index for bulk incorporation in construction materials for roads and play grounds is defined (Markkanen, 1995). More information on this specific index can be found in Section 4.5.

In the unlikely case of the use of coal bottom ash in building materials then the tables with activity concentrations given in Section 6.3.1.2 can be used for the evaluation for this specific application.

7.2.4 Slags from iron and steel production

7.2.4.1 Technical properties

Slag is a by-product from the pyrometallurgical processing of various ores. The characteristics of both ferrous (steel and blast-furnace Fe) and nonferrous (Ag, Cu, Ni, Pb, Sn, and Zn) slag must be known in order to assess its possible reuse as building material. The characteristics of slag depend on the metallurgical processes that form the material and will influence its classification as waste or as a reusable product. The properties of different types of slag are discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

Ground-granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBFS) is the main by-product from iron production used in construction. Ground-granulated blast-furnace slag is also a well-known cement constituent and concrete addition. Table 7.6 shows the nine cement types according to the European Standard EN 197-1:2011.

Table 7.6

Use of blast-furnace slag in the common Portland cements

| Main types | Designation | Composition (wt%) | |||||||||||

| Main constituents | Minor constituents | ||||||||||||

| Clinker | S | D | Pozzolan | Fly ash | T | Limestone | |||||||

| K | P | Q | V | W | L | LL | |||||||

| CEM II | Portland-slag cement | CEM II/A-S | 80–94 | 6–20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0–5 |

| CEM II/B-S | 65–79 | 21–35 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| Composite cement | CEM II/A-M | 80–94 | <- - - - - - - - - - - - - 6–20 - - - - - - - - - - - -> | 0–5 | |||||||||

| CEM II/B-M | 65–79 | <- - - - - - - - - - - - - 21–35 - - - - - - - - - - - -> | 0–5 | ||||||||||

| CEM III | Blast-furnace cement | CEM III/A | 35–64 | 36–65 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0–5 |

| CEM III/B | 20–34 | 66–80 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| CEM III/C | 5–19 | 81–95 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| CEM V | Composite cement | CEM V/A | 40–64 | 18–30 | – | <- - - 18–30 - - -> | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||

| CEM V/B | 20–38 | 31–50 | – | <- - - 31–50 - - -> | – | – | – | – | 0–5 | ||||

Pelletized blast-furnace slag resulted from cooled blast-furnace slag. It has a vesicular texture and it is used as a lightweight aggregate and finely grounded as cementitious material.

Air-cooled blast-furnace slag is naturally cooled with moderate sprinkling. The crystallized slag, after crushing, sieving, and removing magnetic matter, can be used as construction aggregate, concrete bricks, road bases, and surface and Portland clinker production raw material.

Steel slag is a by-product of the steel-making process formed from the reaction of flux such as calcium oxide with the inorganic nonmetallic components present in the steel scrap. The two main types of steel slag which can be used for construction are basic oxygen furnace (BOF) steel slag and electric arc furnace (EAF) steel slag. Both types of steel slag are commonly blended with ground-granulated blast-furnace slag, coal fly ash and lime to form pavement material, skid resistant asphalt aggregate and unconfined construction fill.

BOF slags have variable compositions depending on the particularities of the metallurgical process followed and the iron ores used. In general, these slags are being used in low-end applications as their management is typically not a priority. In more detail, the main fields of application of BOF slag are aggregates for road construction (Guttm et al., 1967; Everett and Gutt, 1967) (in bound and unbound mixtures), structural fills, hydraulic engineering, fertilizers, waste water treatment, and internal use in the blast furnace.

Apart from the low-end applications, BOF slags are also used as hydraulic binders in combination with other materials. In Europe, BOF slags are mixed with GGBFS and hydraulic road binder are delivered for the stabilization of the road surfacing and upper and lower layers of the roadbed.

Studies into utilizing slag as concrete aggregates, carried out by several researchers, have shown that these slag-aggregate concretes were stronger in compressive strength than plain concrete. However, slag-aggregate concrete was found to be more vulnerable to sulfate attack in aggressive environments.

The possible utilization of slag as a building material has to be explored and the radiological impact of steel slag should be examined carefully as well during all the stages of its life cycle.

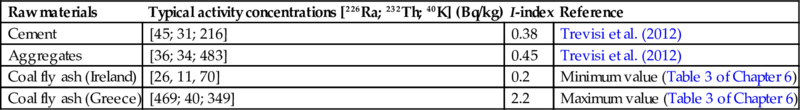

In Table 7.7 a typical mix design for different modern concrete compositions with and without blast-furnace slag is given. This example will be further discussed in the discussion of the radiological aspects.

Table 7.7

Example of mix design for modern concrete compositions with and without blast-furnace slag (kg/m3)

| Raw materials | Reference concrete (no FA) | Concrete containing slag as partial replacement of cement | Concrete containing slaga as a partial replacement of cement and concrete |

| Cement | 400 | 80 | 80 |

| Slag as partial replacement of cement | 0 | 320 | 320 |

| Coarse and fine aggregates | 1850 | 1850 | 1450 |

| Slag as partial replacement of aggregates | 0 | 0 | 400 |

| Water | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Total | 2400 | 2400 | 2400 |

a In this assumption, for a realistic replacement, two different types of slag are to be used in order to replace both cement and aggregates.

7.2.4.2 Radiological properties

Residues from iron and steel production that are used in Portland cement and concretes can contain elevated levels of natural occurring radionuclides (Puertas et al., 2015a,b; Trevisi et al., 2012; Piedecausa et al., 2011a,b). An overview of the radiological properties of the residues is given in Chapter 6. As mentioned before ground-granulated blast-furnace slag is the main by-product from iron production that is currently used as a well-known cement constituent and concrete additive.

In Portland cement, depending of the type of cement larger percentages (up to 95% for blast-furnace cement) can be used (Table 7.6).

For concrete, containing blast-furnace slag, a possible mixing design is given in Table 7.7. For this mixing design, dilution calculations were made in order to calculate the I-index of blast-furnace slag containing concrete, based on the values of the I-index for the constituents (Table 7.8). The result of the I-index calculations is given in Table 7.9.

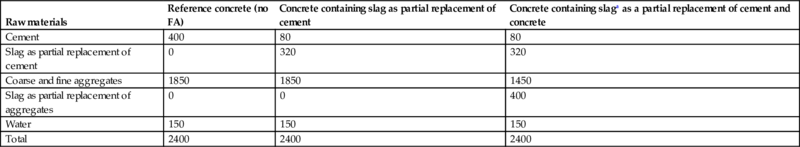

Table 7.8

Typical activity concentration indexes for concrete constituents in modern concrete compositions containing blast-furnace slag

| Raw materials | Typical activity concentrations [226Ra; 232Th; 40K] (Bq/kg) | I-index | Reference |

| Cement | [45; 31; 216] | 0.38 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Aggregates | [36; 34; 483] | 0.45 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Blast-furnace slag (Poland) | [115; 35; 192] | 0.62 | Minimum value (Table 10 of Chapter 6) |

| Blast-furnace slag (Turkey) | [178; 148; 242] | 1.41 | Maximum value (Table 10 of Chapter 6) |

The I-index calculation is based on European Commission 1999; Radiation Protection 112; Radiological Protection Principles Concerning the Natural Radioactivity of Building Materials; and Directorate-General, Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection.

Note that the I-index, as proposed by Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom, is only used for building materials or for their constituents if the constituents are also building materials: An I-index given for a by-product or cement makes the unrealistic assumption that 100% of the by-product or cement is used as a building material.

Table 7.9

I-index of modern concrete compositions containing blast-furnace slag

| Raw materials | Reference concrete (no blast-furnace slag) | Concrete containing slag as partial replacement of cement | Concrete containing slag as a partial replacement of cement and concrete |

| Maximum activity of blast furnace (I=1.41) | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.71 |

| Minimum activity of blast-furnace slag (I=0.62) | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

7.2.5 Copper slag

7.2.5.1 Technical properties

The physico-mechanical characteristics of copper slag suggest that it can be utilized in the cement and concrete industry (Shi et al., 2008). Granulated copper slag exhibits pozzolanic properties, and then, it could be used as a constituent for common Portland cement.

When slowly cooled and milled to be used as fine or coarse aggregate in high-strength concrete, the concrete showed comparable or even superior mechanical properties compared with conventional OPC. Depending of the composition and characteristics of copper slags, they can be used as ballast, abrasive material, fine aggregate in concrete, aggregates in hot mix asphalt pavements, cement raw material, roofing granules, glass, tiles, and so on (Al-Jabri et al., 2006, 2009; Arino-Moreno and Mobasher, 1999; Shi and Qian, 2000; Khanzadi and Behnood, 2009).

In Table 7.10 a typical mix design for different concrete compositions with and without copper slag is given. This example will be further discussed in the discussion of the radiological aspects.

Table 7.10

Example of mix design for modern concrete compositions with and without copper slag (kg/m3)

| Raw materials | Reference concrete (no FA) | Concrete containing slag as a partial replacement of concrete |

| Cement | 400 | 400 |

| Coarse and fine aggregates | 1850 | 1450 |

| Slag as partial replacement of aggregates | 0 | 400 |

| Water | 150 | 150 |

| Total | 2400 | 2400 |

7.2.5.2 Radiological properties

For concrete, containing copper slag, a possible mixing design is given in Table 7.10. For this mixing design, dilution calculations were made in order to calculate the I-index of copper slag containing concrete, based on the values of the I-index for the constituents (Table 7.11). The result of the I-index calculations is given in Table 7.12.

Table 7.11

Typical activity concentration indexes for concrete constituents in modern concrete compositions containing copper slag

| Raw materials | Typical activity concentrations [226Ra; 232Th; 40K] (Bq/kg) | I-index | Reference |

| Cement | [45; 31; 216] | 0.38 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Aggregates | [36; 34; 483] | 0.45 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Copper slag (Poland) | [317; 54; 886] | 1.62 | Minimum value (Table 11 of Chapter 6) |

| Copper slag (Germany) | [770; 52; 650] | 3.04 | Maximum value (Table 11 of Chapter 6) |

The I-index calculation is based on European Commission 1999; Radiation Protection 112; Radiological Protection Principles Concerning the Natural Radioactivity of Building Materials; and Directorate-General, Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection.

Note that the I-index, as proposed by Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom, is only used for building materials or for their constituents if the constituents are also building materials: An I-index given for a by-product or cement makes the unrealistic assumption that 100% of the by-product or cement is used as a building material.

7.2.6 Red mud

7.2.6.1 Technical properties

The potential uses of red mud can be classified into recovery of major or minor constituents and direct uses or incorporation into products such as concrete, tiles, and so on. Within the first group, recovery of iron, vanadium, chromium, titanium dioxide, rare earths, and aluminum oxide has been reported in the literature. With regard to applications in building materials, red mud can be used as a raw material in cement, bricks, roofing tiles, and glass-ceramics production (Thakur and Sant, 1983; Tsakiridis et al., 2004; Vangelatos et al., 2009; Singh et al., 1997; Yang and Xiao, 2008; Romero and Rincón, 2000; Vincenzo et al., 2000; Pontikes and Angelopoulos, 2013).

The use of bauxite residue in Portland cement production has been the subject of some research projects from as early as 1936 (Thakur and Sant, 1983). The iron and alumina contents of the residue are beneficial in the mix raw material to produce clinker. The residue must be pressured before its incorporation to the raw mix in a proportion below 5% (Tsakiridis et al., 2004; Vangelatos et al., 2009). Also, some special cement has been investigated in the past using of mixtures of gypsum and bauxite residue. In particular, the titanium content of the mud was found to be beneficial to cement compressive strength (Singh et al., 1997; Yang and Xiao, 2008).

Artificial aggregates made of red mud require a number of processing steps, including drying, pelletizing, and calcinations. Therefore, it is unlikely that such type of artificial aggregate could be competitive with other types due to the processing cost (Romero and Rincón, 2000).

7.2.6.2 Radiological properties

The radiological properties of red mud are discussed in detail in Chapter 6. On the basis of the activity concentration of naturally occurring radionuclides in red mud calculations can be made regarding the resulting activity concentration index of the concrete.

Especially the production of alkali-activated cement and concretes could enable the incorporation of larger percentages of red mud in concrete. This aspect is discussed in more detail in Section 7.3.5.

7.2.7 Overall discussion of radiological aspects of Portland cements and concretes

Commonly, the concentration of radionuclides, originating from residues, is decreased in the produced Portland cements and concretes due to a dilution effect. This is illustrated in Table 7.13 where the radiological properties of some investigated concretes are given.

Table 7.13

Radiological properties of investigated concrete samples (extracted from NORM4Building database)

| Country | Radionuclide concentration (Bq/kg) | I-index | Number of samples | References | ||

| 226Ra | 232Th | 40K | ||||

| China | 25.8 | 26.8 | 852 | 0.5 | 13 | Xinwei (2005) |

| Estonia | 35.1 | 11.3 | 207 | 0.2 | 1 | Lust and Realo (2012) |

| Hungary | 11 | 6 | 142 | 0.1 | 2 | Szabó et al. (2013) |

| Lithuania | 32 | 17 | 426 | 0.3 | 1 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Luxembourg | 93 | 92 | 110 | 0.8 | 2 | Trevisi et al. (2012) |

| Poland | 18.5 | 16.5 | 350 | 0.3 | 2 | Zalewski et al. (2001) |

| Slovakia | 17.1 | 19.7 | 351 | 0.3 | 34 | Michael (2010), Vladar and Cabanekova (1998) |

| Spain | 23.2 | 21 | 278 | 0.3 | 9 | Chinchon-Paya et al. (2011) |

| Syria | 24.5 | 4.8 | 70 | 0.1 | 6 | Shweikani et al. (2013) |

These values are the mean values of individual entries.

The I-index calculation is based on European Commission 1999; Radiation Protection 112; Radiological Protection Principles Concerning the Natural Radioactivity of Building Materials; and Directorate-General, Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection.

Generally, the uranium series radionuclide concentration in the cement-based materials, in descending order is: Fly ash>Anhydrous calcium aluminate cement>Slags>Anhydrous Portland cement>Limestone=Silica fume (Puertas et al., 2015a,b).

Aggregates often have the greatest influence in the concrete radioactivity because they account for more than 80% of the concrete volume. Radium-rich and thorium-rich materials, for instance, granites and gneiss or others used as aggregates in concrete may enhance the indoor gamma radiation from the walls in buildings (Ackers et al., 1985; Botezatu et al., 2002). In a similar way, some industrial wastes such as blast-furnace slag, coal fly ash, and coal bottom, among others, can cause enhanced activity concentrations of concrete when they are used as aggregates (Kominek et al, 1992: Nuccetelli et al., 2015b; Skowronek and Dulewski, 2001). By contrast, natural stone of sedimentary origin such as limestone or dolomite does not enhance the radionuclide content of concrete mix. From a recent update of Trevisi et al. (2012), reporting summarized data of radioactivity concentrations of building materials in EU countries, some information can be obtained. For 226Ra, 232Th, and 40K averages (and ranges) of EU national values, expressed in Bq/kg, are 60 (14–272), 34 (8–138), and 345 (17–685), respectively (Trevisi et al., 2016). By a detailed analysis of the database it is possible to see that the highest activity concentrations are generally relevant to concretes containing NORM residues.

With regard to the radon production in concrete as a result of the presence of 226Ra, it is well-known that it depends on some characteristics of the concrete such as moisture content, porosity, tortuosity, permeability, cracks formation, and thickness of the concrete element. In general, high-moisture content in porous materials increases the radon exhalation rate (Kovler et al., 2005; Stranden et al., 1984; Yu et al., 1996). On the contrary, dehydration of concrete due to aging of materials determines a decrease of the radon exhalation rate.

7.3 Alkali-activated cement and concretes (geopolymers)

7.3.1 Introduction

In 1895 and 1908, for the first time patents demonstrated that the combination of a vitreous slag and different alkaline solutions could be used to develop a material with a performance similar to Portland cement. In the 1960s and the 1970s of the last century, relevant contributions were given by Glukhovsky (1959) at the Institute for Binders and Materials of Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture, focusing on the alkali-carbonate activation of metallurgical slags. In early 1980s (Davidovits, 1982), in France, patented several aluminosilicate-based formulations and introduced the name “geopolymers” for these alkaline materials. Since the 1990s several research groups are working on the development of such alternative construction materials, attempting to optimize the formulations and final (mechanical, chemical, physical, and microstructural) properties. More recently, pilot-scale and industrial trials on the application of alkali-activated binders (concrete, mortars, and related materials) were conducted, and recommendations to the national and international standardization bodies were given for the practical implementations of these alternative building materials.

The alkali-activated materials (AAMs) are derived by the reaction of an alkali metal source (solid or dissolved) with a solid silicoaluminate powder (binder or precursor). This solid can be metakaolin, metallurgical slag, natural pozzolan, fly ash, or bottom ash. The alkali sources used can include alkali hydroxides, silicates, carbonates, sulfates, aluminates, or oxides (Provis and van Deventer, 2014).

According to the chemical composition of the binder, we can distinguish two main systems of AAMs:

(1) High-calcium AAMs [where the binder is mainly blast-furnace slag (BFS)].

(2) Low-calcium AAMs [where the binder is mainly fly ash (FA)].

7.3.2 Blast-furnace slag

7.3.2.1 Technical properties

In the second half of the 20th century alkali-activate slag (AAS) concretes have been successfully applied in different fields of civil engineering, particularly in Eastern Europe: Ukraine, Russia, and Poland (Shi et al., 2006). A historical study of more than 50 years old AAS concrete in Belgium was recently presented (Buchwald et al., 2015). Valuable experience for further development and applications of alkali-activated binders and concretes has been gathered from the existing applications. The lack of uniformly accepted standards is probably the major obstacle toward broader application in the construction industry. The recommendation of RILEM Technical Committee 224-AAM is that a performance-based standards regime should be implemented to provide description and regulation for alkali-activated binders and concretes (Provis and van Deventer, 2014).

Ground-granulated blast-furnace slag is the most frequently used metallurgical slag for the production of alkali-activated slag mortars, and concretes. During the alkali activation process, the vitreous phase of BFS dissolves, forming, mainly, calcium aluminosilicate hydrates (C-A-S-H) afterwards. This reaction depends on a whole series of parameters such as physical and chemical properties of BFS, properties of alkali activator (the nature, concentration, and pH of the activators), and conditions of the reaction (temperature, relative humidity, and curing time). The influence of all of these factors on the structure and properties of alkali-activated blast-furnace slag (AAS) pastes, mortars, and concretes is thoroughly presented in some other publications (Shi et al., 2006; Davidovits, 2008; Provis and van Deventer, 2014; Provis et al., 2015; Pacheco-Torgal et al., 2015).

Properties of AAS are highly affected by the activator nature (type) and concentration. The earliest binder made from BFS was lime-activated BFS. Alkali hydroxides, silicates, sulfates, and carbonates or their mixtures can successfully activate BFS.

The activator is normally used as a solution. On the other hand, one part of the binder can be produced by mixing or intergrinding solid-state activator with the BFS. However, this might cause problems due to the hygroscopic nature of the activator. Furthermore, the heat of hydration released during dissolution of solid activator may enhance the reactivity of BFS. Optimal concentration and dosage strongly depend on the nature of slag, alkali activators used, and curing conditions.

The highest strength is most commonly developed when BFS was activated with sodium silicate (water glass) as demonstrated in Fig. 7.1 (Puertas and Torres-Carrasco, 2014). However, undesirable side effects, such as fast setting and/or high-drying shrinkage, usually accompany the high strength. Such problems might be solved by extending the mixing time. The activation of BFS with NaOH or KOH results in a high-early strength, but when considering the strength at 7 days or later ages, it is usually lower in comparison to BFS activated with sodium silicate.

The selection of a suitable alkali activator most probably has the largest economic and environmental impact on the production of alkali-activated binders or concretes. The large-scale utilization of commercially produced sodium silicate as an activator will face limitations in terms of scalability, cost, practical handling issues, and the environmental cost of this product (Provis et al., 2015). New activators should be investigated in order to contribute to the fabrication of inexpensive binder systems, sustainable processes, and nonhazardous handling. Sodium sulfate, NaOH/Na2CO3 mixture, and the glass waste mixed solution or NaOH/silica fume also proved to be effective as alkali activators for BFS—see Fig. 7.1 (Puertas and Torres-Carrasco, 2014).

Curing conditions have a significant impact on the mechanical properties of AAS, as the provision of proper curing proved to be essential for high-strength development. Curing in water, the most common curing procedure for Portland cement is not recommended, as it might lead to premature leaching and unavoidable loss of strength. More appropriate options of curing at room temperature are sealed curing (in a sealed container) or curing in a humid chamber (Relative humidity>90%). Curing at elevated temperature (heat or steam curing) increases the rate of alkali activation reaction and strength development, whereby irreversible loss of water should be prevented as it might lead to the high-drying shrinkage, micro cracks formation, and strength loss (Marjanović et al., 2015). Steam and autoclave curing are significantly effective in reducing the drying shrinkage of AAS mortars. Unconventional curing by ultrasound or microwaves also has some potential (Komljenović, 2015).

The water/binder ratio plays a dominant role in strength development of AAS. Generally, a lower water/binder ratio induces higher strength. However, it depends on the activator concentration and dosage as well (Fernández-Jimenez et al., 1999). Standard water reducing admixtures, which were developed for the Portland cement systems, usually do not work properly in the alkali activation process due to high-alkaline conditions present (Palacios et al., 2009). The setting time of AAS primarily depends on the dissolution rate of the precursor material and precipitation of the reaction products. The setting time can vary significantly as a function of curing conditions and the type, concentration, and dosage of the activator used. The heat of hydration of AAS is usually lower than OPC (Križan and Živanović, 2002).

The mechanical properties of AAS concrete, such as compressive strength, flexural and splitting tensile strengths, drying shrinkage, etc., are normally assessed by using the standards of ordinary Portland cement concrete. However, some of those methods may be inappropriate for geopolymers (Provis and van Deventer, 2014).

AAS concrete has some advantages with respect to the OPC concrete, such as a low heat of hydration, a high-early strength, and an increased durability in aggressive environments. AAS concrete also shows a greater tensile strain capacity than OPC concrete due to the greater creep, the lower elastic modulus, and the higher tensile strength. Drying shrinkage and tendency to microcrack formation of AAS concrete is usually higher than OPC, particularly under dry conditions. The problem of efflorescence is also frequently present in AAS concrete, due to the high concentration and mobility of alkalis present in the pore solution, and the porosity of hardened AAS (Puertas et al., 2003). The efflorescence is rarely harmful to the product performance, but its avoiding is highly desirable due to the undesirable visual effects. The elastic properties of AAS under applied force, which are of particular importance for construction applications, can be improved by introducing fiber reinforcement such as short fibers or unidirectional long fibers into the AAS matrix. The addition of different types of fibers (polypropylene, polyvinyl alcohol, alkali-resistant glass, steel, carbon, etc.) usually increases flexural and splitting tensile strength, reducing drying shrinkage as well. Some adverse effects on workability and compressive strength were also reported (Puertas et al., 2003).

Concrete durability during long-term exploitation is of key importance for its safe and efficient functioning and it is determined by its ability to resist chemical attacks, abrasion, weathering action, or any other process of deterioration.

AAS usually contains a large amount of alkalis, which means that if AAS is being used in structural applications, an important precondition is met for the alkali-aggregate reaction (AAR) to occur. The role of calcium is known to be important in determining the rate and extent of the alkali silica reaction (ASR). AAS concrete is probably more resistant to ASR than Portland cement concrete due to the lower availability of alkalis and calcium (C-A-S-H with a lower Ca/Si ratio) (Puertas et al., 2009). However, the opposite, a lower resistant to ASR in comparison with Portland cement was also reported (Bakharev et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2015).

Carbonation is one of the most important degradation processes that can significantly affect the long-term durability of concrete infrastructures. The carbonation rate of AAS depends on the properties of BFS. For example, higher amount of MgO present in BFS reduces the carbonation rate (Bernal et al., 2014). The type and concentration of the activator used also influences the carbonation rates, as well as the water/binder ratio, the amount of BFS present in the concrete mixture, and curing conditions.

Frost resistance of AAS becomes important in cold climates when the concrete construction is exposed to freeze-thaw cycling. Deterioration of concrete can appear in two principal forms: internal cracking due to freezing and thawing cycles and surface scaling due to freezing in the presence of deicing salts (usually NaCl). However, the available literature is mainly focused on issues related to internal cracking (Cyr and Pouhet, 2015).

Different methods for testing the frost resistance of Portland cement concretes are available. However, these methods are based on different experimental conditions such as the temperatures of freezing and thawing, cycle count and duration, etc. The curing procedure prior to this or any other type of alkali-activated BFS testing is particularly important, as the proposed curing methods for Portland cement systems might not be appropriate for AAS. Generally, AAS shows very good frost resistance due to favorable characteristics of the air-void/bubble network system (Cyr and Pouhet, 2015). Sodium silicate-activated BFS concrete usually has the least porous structure, highest strength, and best frost resistance.

Chloride penetration through concrete can cause corrosion of the reinforcing steel and deterioration of reinforced concrete structures. This type of deterioration is quite common in concrete structures exposed to deicing salts or sea water. Therefore, the resistance of reinforced concrete structures to chloride penetration is quite important for designing, producing, and maintaining durable concrete structures. A great number of methods for chloride penetration testing developed for Portland cement concretes are available. The RILEM Technical Committee TC 178-TMC: “Testing and Modeling Chloride Penetration in Concrete” has tested four different groups of methods for determining chloride transport parameters in concrete: (1) natural diffusion methods, (2) migration methods, (3) resistivity methods, and (4) colorimetric methods. The RILEM Technical Committee TC 224 AAM (Provis and van Deventer, 2014) suggested that chloride ponding tests such as ASTM C1543, or rapid migration tests such as the Nord Test method NT Build 492, might be more suitable for AAMs testing. Compared with OPC, alkali-activated binders demonstrate better performance against chloride ingress, according to both accelerated (Fig. 7.2) (NordTest NT Build 492) and ponding (ASTM C1543) methods. The NordTest method is considered more reliable as an accelerated way to assess chloride durability of AAMs (Torres-Carrasco et al., 2015).

Corrosion of reinforcing steel in AAS is strongly influenced by the specific BFS chemistry (presence of sulfide). Therefore, the predictions designed for Portland cement concretes may not be applicable to the AAS concretes. Despite the fact that some reports for corrosion of reinforcing steel testing in AAS already exist, the method specifically adapted to the complex chemistry of AAS is yet to be developed.

External sulfate attack is the consequence of impact of sulfate ions present in soils, underground waters, sea water, or industrial waste waters on hardened concrete. Sulfates generally cause harmful effects on cement, depending on the type of cement used, the nature and concentration of aggressive sulfate solution, the presence of different cations and/or salts in sulfate solution, the quality of concrete, as well as concrete exposure conditions. Different methods and criteria were also used to assess the resistance of AAS mortar or concrete to external sulfate attack, most commonly based on (1) expansion, (2) flexural and/or compressive strength, and (3) the strength loss index (Komljenović et al., 2013). More detailed reports are given elsewhere (Shi et al., 2006; Provis and van Deventer, 2014; Pacheco-Torgal et al., 2015). Generally, AAS performs better in sulfate environment than Portland cement systems. However, this performance depends also on the properties of BFS, the type and concentration of the activator, concentration of sulfate solution, and cations present in the solution.

Despite the fact that most of the concrete structures are not exposed to acidic conditions, some concrete structures can be exposed to acidic aggressive environments such as specific industrial processes, acid rains, acid sulfate soils, animal husbandry, or biogenic sulfuric acid corrosion (present in sewage pipes). AAS is expected to demonstrate similar or even better acid corrosion resistance in comparison with Portland cement, due to the significant differences in the reaction products (absence of Portlandite in and low Ca/Si ratio of the BFS-based binder). According to the available literature, AAS generally shows good performance in acidic environments (Komljenovic et al., 2012; Varga et al., 2015).

7.3.2.2 Radiological properties

The radiological properties of blast-furnace slag are discussed in Chapter 6. These data can be used to assess the activity concentration of an alkali-activated cements and concrete based on blast-furnace slag.

Radiological properties of alkali-activated cements and concretes produced on the basis of blast-furnace slag and coal fly ash are discussed in Section 7.3.3.2.

7.3.3 Coal fly ash

7.3.3.1 Technical properties

Development of alkali-activated cements allows using fly ash as an aluminosilicate component (Krivenko, 1992). A specific feature of these systems is the high-initial pH value. When being appropriately used, the alkalis accelerate the first stage of destruction of the initial aluminosilicate structure, and then take an active part in the formation of compounds responsible for the strength characteristics of the material.

An important component of fly ash alkali-activated (AAFA) cement is low-calcium coal ash (up to 10% of CaO by mass, class F according to ASTM classification). In addition, also Class C ash can be used as is the case for several applications in the United States.

Curing conditions of AAFA cements also differ depending on the required properties for tailored applications: (i) special applications require autoclave curing, steam curing, and drying; (ii) common cements are cured in normal conditions (steam curing).

According to the Ukrainian Standard DSTU B V.2.7-181:2009 “Alkaline cements. Specifications” (DSTU B.V. 2.7-181, 2009), AAFA cements can be divided three classes, as shown in Table 7.14.

Table 7.14

Fly ash in the alkali-activated cements

| Class | Designation | Composition (% by mass) | |||

| Main constituents (aluminosilicates) | Alkali (Na or K) metal compounds (over 100%) | ||||

| Granulated blast-furnace slag | Clinker | Fly ash | |||

| AAC I—ASH | Alkali-activated cement with addition of fly ash | 55–90 | 0–10 | 10–35 | 1.5–12 |

| AAC III | Alkali-activated pozzolanic cement | 20–64 | 36–80 | 1.5–12 | |

| AAC V | Alkali-activated composite cement | 30–50 | 5–10 | 40–65 | 1.5–12 |

Based on DSTU B.V. 2.7-181, 2009. Alkaline Cements, Specifications. National Standard of Ukraine, Kyiv.

The main reaction products according the curing conditions are shown in Fig. 7.3 (Krivenko and Kovalchuk, 2002; Krivenko et al., 2006).

The mechanical strength of AAFA cements is similar to OPC or AAS. Their evolution with curing age is shown in Fig. 7.4. Compositions and properties of the cements are given in Table 7.15. Remarkable is the strength gain at older ages: after three years curing samples might harden over 150% of the strength obtained after 28 days.

Table 7.15

Characteristics of alkali-activated cements

| No. | Cement composition, % by mass | Properties | Flow (cone), mm (W/C) | |||||

| Clinker | Fly ash | Granulated blast-furnace slag (S) | Na2CO3 | Plasticizer | Paste of normal consistency, % | Initial setting time, min | ||

| 1 | – | 60 | 40 | 5 | 1 | 25.7 | 75 | 115/0.34 |

| 2 | 10 | 60 | 30 | 5 | 1 | 25.5 | 70 | 112/0.34 |

| 3 | 20 | 80 | – | 5 | 1 | 26.7 | 80 | 108/0.31 |

| 4 | 30 | 70 | – | 5 | 1 | 26.0 | 75 | 110/0.32 |

| 5 | OPC CEM II/A-400 (reference) | 27.8 | 85 | 112/0.38 | ||||

At the same time, AAFA concrete shows other interesting properties (Grabovchak, 2013; Krivenko et al., 2014; Krivenko et al., 2005; Kovalchuk and Grabovchak, 2013; Krivenko et al., 2010): (i) high-corrosion resistance in sea water, in Na2SO4 (10% concentration) and MgSO4 (up to 4% concentration) solutions; (ii) low shrinkage; (iii) high freeze-thaw resistance. These concretes are highly advantageous in massive structures prepared in situ; and (iv) high-temperature resistance (heat- and fire-resistant concretes). Residual strength of such materials after burning at 800°C could reach 500% comparing with the strength in normal conditions.

The durability of AAFA concretes is similar to that of previously presented AAS concretes. Sulfate resistance is outstanding and has no analogs among the traditional materials. There were obtaining concretes with strength classes C15–C40. Frost resistance, weather resistance, water impermeability, and other service properties are similar to those of traditional concretes (Kovalchuk and Grabovchak, 2013; Krivenko et al., 2010).

7.3.3.2 Radiological properties

The discussion below deals both with the radiological properties of alkali-activated cements and concretes produced on the basis of blast-furnace slag and coal fly ash since in most cases AAMs will merge several by-products that contain naturally occurring radionuclides.

The radiological properties of geopolymers or alkali-activated cement pastes have been recently studied in detail by Puertas et al. (2015a,b). Sample preparation and activation conditions used are shown in Table 7.16.

Table 7.16

Sample preparation and activation conditions of geopolymers used to study radiological features (Puertas et al., 2015a,b)

| Sample | Solution | liquid-to-solid ratio | SiO2/Na2O |

| Water glass-AA Slag | Sodium silicate | 0.4 | 0.86 |

| Glass-AASlag | NaOH/Na2CO3+glass waste | 0.4 | 0.86 |

| N/15Wg-AA fly ash | NaOH 10 M+sodium silicate | 0.3 | 0.19 |

| Glass-AA fly ash | NaOH 10 M+glass waste | 0.3 | 0.11 |

The radionuclide activity concentrations in alkaline cement pastes (Wg-AAS, Glass-AAS, N/15Wg-AAFA, and Glass-AAFA) (see Table 7.17) have been calculated considering the percentage of slag or fly ash in the anhydrous geopolymers and in the activated end products. It needs to be noted that the 40K concentration increases in such activated materials because the potassium impurities, that are often present in the NaOH activator, result in an increased 40K potassium content in the end product.

Table 7.17

Activity concentrations in raw materials (fly ash, BFS, and waste glass) and cements after alkaline activation (in Bq/kg) (uncertainty, k=2) (Puertas et al., 2015a,b)

| Series | 238U | 232Th | 40K | Indexa | |||

| Material | 234Th | 214Pb | 228Ac | 212Pb | 208Tl | ||

| Fly ash | 130±7.1 | 127.4±1.3 | 130.3±1.5 | 133.8±1.3 | 41.33±0.57 | 316.4±5.9 | 1.1815±0.0089 |

| BFS | 156.4±6.8 | 147.2±1.4 | 45.7±0.86 | 42.9±1.2 | 14.71±0.30 | 76.3±2.7 | 0.7448±0.0065 |

| Waste Glass | 11.4±1.1 | 8.73±0.19 | 5.83±0.22 | 6.28±0.12 | 1.867±0.075 | 226.8±4.4 | 0.1338±0.0020 |

| Wg-AAS | 91.5±5.6 | 48.7±1.1 | 22.84±0.71 | 23.3±0.69 | 7.7±0.39 | 77.0±5.0 | 0.3022±0.0054 |

| Waste Glass-AAS | 94.4±6.7 | 54.5±1.4 | 23.78±0.81 | 24.99±0.83 | 8.04±0.41 | 89.2±4.8 | 0.3303±0.0064 |

| N/15Wg-AAFA | 56.4±5.7 | 36.44±0.97 | 67.8±1.4 | 75.1±1.8 | 21.57±0.59 | 578±15 | 0.6531±0.0092 |

| Waste Glass-AAFA | 57.4±3.2 | 37.9±1.1 | 62.2±1.2 | 75.1±1.2 | 22.62±0.63 | 550±14 | 0.6207±0.0084 |

a Note that the I-index, as proposed by Council Directive 2013/59/Euratom, is only used for building materials or for their constituents if the constituents are also building materials: An I-index given for a by-product makes the unrealistic assumption that 100% of the by-product is used as a building material.

A paper of the radiological characterization and impact of alkali-activated concretes has been recently published (Nuccetelli et al., 2017). The publication reports results of a study on five different types of fly ash from Serbian coal burning power plants and their potential use as a binder in alkali-activated concrete (AAC), depending on their radiological and mechanical properties. Five AAC mixtures with different types of coal burning fly ash and one type of blast-furnace slag were designed. Measurements of the activity concentrations of 40K, 226Ra, and 232Th were done both on concrete constituents (fly ash, blast-furnace slag, and aggregate) (see Table 7.18) and on the five solid AAC samples (see Table 7.19). Experimental results were compared by using the activity concentration assessment tool for building materials—the activity concentration index I, as introduced by the RP 112 and EU Basic Safety Standards [RP 122, 1999;24] and in Chapter 4. All five designed alkali-activated concretes comply with EU BSS screening requirements for indoor building materials. Finally, the index I values were compared with the results of the application of a more accurate index-I (ρd), which accounts for thickness and density of building materials (Nuccetelli et al., 2015a) and the annual dose, evaluated with an accurate formula accounting for the actual density and thickness of the AAFAC concrete sample, was also calculated. Considering the actual density and thickness of each concrete sample index-I (ρd) values are lower than index-I values and the annual dose resulted negative, once the background is subtracted, in three cases and less than 2.3E-02 mSv, with uncertainties, in the other two cases. In the paper, a synthesis of main results concerning mechanical and chemical properties has also been provided.

Table 7.18

Natural radionuclide activity concentrations in Serbian fly ash and blast-furnace slag samples used in alkali-activated concretes (Nuccetelli et al., 2017)

| 232Th | 226Ra | 40K | index Ia | |

| (Bq/kg) | ||||

| Fly ash-1 | 90.9±1.7 | 123±5 | 445±7 | 1.01 |

| Fly ash-2 | 112±2 | 163±5 | 416±7 | 1.24 |

| Fly ash-3 | 42.7±0.8 | 56.2±2.1 | 199±3 | 0.47 |

| Fly ash-4 | 66.0±1.2 | 151±5 | 393±6 | 0.96 |

| Fly ash-5 | 78.3±1.5 | 152±4 | 369±6 | 1.02 |

| Blast-furnace slag | 26.5±0.5 | 108±3 | 122±2 | 0.54 |

| Fly ash from RP112 (EC, 1999) | 100 | 180 | 650 | |

| Fly ash (Nuccetelli et al, 2015b) | 80 | 207 | 546 | |

| Slag from RP112 (EC, 1999) | 70 | 270 | 240 | |

| Slagb | 63 | 147 | 246 | |

a Note that the I-index, as proposed by COUNCIL DIRECTIVE, 2013/59/EURATOM, is only used for building materials or for their constituents if the constituents are also building materials: An I-index given for a by-product makes the unrealistic assumption that 100% of the by-product is used as a building material.

b Based on new elaboration of national values given in the EU database.

Table 7.19

Natural radionuclide activity concentrations of alkali-activated concretes (AAC) samples: calculation of index I, index I (ρd), and gamma dose

| AAC samples | 232Th | 226Ra | 40K | index I | I (ρd) | D(ρd) (mSv/year) |

| (Bq/kg) | ||||||

| AAC-1 | 18.4±0.4 | 28.5±1.5 | 232±4 | 0.26±0.01 | 0.23±0.01 | 0.8E-02±1.0E-02 |

| AAC-2 | 18.6±0.4 | 28.8±1.3 | 225±4 | 0.26±0.01 | 0.24±0.01 | 1.4E-02±0.9E-02 |

| AAC-3 | 12.5±0.2 | 21.2±0.9 | 196±3 | 0.20±0.01 | 0.18±0.01 | −6.4E-02±0.6E-02 |

| AAC-4 | 14.9±0.3 | 27.7±1.7 | 218±3 | 0.24±0.01 | 0.21±0.01 | −1.6E-02±1.0E-02 |

| AAC-5 | 16.1±0.3 | 28.3±1.2 | 197±3 | 0.24±0.01 | 0.21±0.01 | −1.9E-02±0.8E-02 |

7.3.4 Steel-melting slags

7.3.4.1 Technical properties

The chemical-mineralogical composition of steel-melting slags varies within wide ranges, and this is the major drawback for recycling (Krivenko, 1986).

Alkali-activated cements made from basic steel-melting slags cured for 28 days in normal conditions show compressive strengths of 15–20 or 20–30 MPa when sodium carbonate or sodium di- and metasilicate are used as activators, respectively. Appreciable hardening is observed at later ages (Kavalerova et al., 2000): 30–42 MPa with sodium carbonate and 46–58 MPa with sodium metasilicate after 1 year; 40–50 and 60–70 MPa, respectively, for the same activators, after 4 years.

Mixtures formulated with low-basic glassy steel-melting slags tend to show slower hardening rates: only by the third day of normal curing the material acquires the resistance achieved after 24 h by the cements made from basic slags. The high-basic steel-melting slags are even less reactive and 14 days curing are required to get the strength of a basic slag formulation after 24 h.

One way to accelerate the hardening rate of such slow reactive systems is mixing with granulated blast-furnace slag. When properly combined with a high-basic crystallized steel-melting slag the obtained mixture acts as a quick-hardening cement: compressive strengths of 52–62, 66–80, and 90–110 MPa after 3, 7, and 28 days curing. The use of these slags also as aggregates in concrete mixtures can increase their consumption rates to up to 90 wt% of the final composition of the construction material (Kavalerova et al., 2000).

7.3.4.2 Radiological properties