EIGHT

The Taiping Rebellion: A Military Assessment of Revolution and Counterrevolution

Rarely in the course of human history do we see a mighty empire decline so precipitously and helplessly as the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) of China. This dramatic decline manifested itself most poignantly in the mid-nineteenth century through a number of devastating popular uprisings all over the country, severely shaking the foundation of Manchu rule over this vast nation. In the southwest, the ethnic Miao rebelled in Guizhou province, and the Hui Muslims took up arms against the government in Yunnan from 1855 to 1873, establishing a small but violently defiant peasant government at Dali. In the north and northwest, Muslims in Shanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, and Qinghai also rose up to rebel against the dynasty in 1862. The rebellion spread to Xinjiang, where it was not put down until 1877. The fire of destruction sprang up not just in the border regions, but also in the heartland of China. In Shandong, Henan, and Anhui provinces, the Nian uprising (1851–1868) presented a powerful blow to the confidence and structure of the government. Of all these tremendous popular rebellions, however, none matches the scale, intensity, and level of destruction of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864).

Even when placed in global perspective, China's Taiping Rebellion, which resulted in the death of at least 25 million people, is the most destructive civil war in history. When compared with the other bloody civil war that was unfolding almost at the same time in the United States, where a little over 600,000 lives were lost, the Taiping Rebellion is staggeringly immense in its devastation. This chapter attempts to elucidate only the main strands of the military side of the Taiping Rebellion.

THE COURSE OF THE WAR

To call the Taiping Rebellion a war is to render justice to what really transpired in China during those years. “Rebellion” often implies a sense of transiency, ephemeral significance, and failure. Yet the Taiping rebellion lasted fifteen years. It involved troop movements of tens of thousands at an unprecedented frequency and the massive mobilization of land and naval forces on an unprecedented scale. It was fought in eighteen of China's provinces. Undoubtedly, the Taiping Rebellion was the largest peasant war in China's long history.

The rebellion was led by a small group of visionary peasant rebels, the chief of whom was a man named Hong Xiuquan. Hong belonged to the Hakka minority of south China, a people who had migrated from north China centuries before. Although ethnically Han Chinese, the Hakkas spoke a dialect distinct from those of the native southerners. Often meeting with hostility and discrimination, they maintained a strong sense of identity and tended to dwell in their own separate communities. Hong followed the traditional career path in his youth by diligently preparing for the imperial examinations. Four times he traveled from his home village in Guangdong province to the southern metropolis of Canton (Guangzhou) to take the exam, and four times he failed. Amid enormous anguish and frustration, Hong encountered Protestant missionaries in Guangzhou; their proselytizing literature would provide him with a powerful Christian vision as the ideological basis of the Taiping Rebellion. With his hopes of pursuing a position as a scholar-official dashed, Hong started to organize rebellious forces in neighboring Guangxi province, where years of arduous preaching and secret recruiting among the Hakka communities resulted in a major eruption in 1850, the year that marked the beginning of the momentous Taiping Rebellion.

The armed revolt against the Qing government began on Hong Xiuquan's thirty-seventh birthday, January 11, 1850. At a gigantic birthday feast in Jintian village, Guangxi, Hong virtually declared war against the Qing dynasty in front of tens of thousands of his followers. Immediately Hong and his Taiping rebels started to seize nearby county governments, mobilizing new recruits along the way, and rapidly became a nightmare for the ruling regime.

Key to the swift success of the Taiping armed rebellion was the command structure at its highest level. On top of the military echelon was of course Hong Xiuquan himself, who was called the “Heavenly King” (tian wang). Second in command was the “Eastern King,” Yang Xiuqing, a former coal miner and the most brilliant military commander of the Taiping forces. Following Hong and Yang were four other “kings,” with equal command power. The stunning cohesiveness of this supreme command is without a doubt the most important factor contributing to the impressive military victories of the Taipings in the early stages of their revolt. As time went by, the tragic erosion of this cohesiveness and the internecine power struggle among the six supreme commanders laid the foundation for the ultimate demise of the Taiping uprising.

The fundamental difference between the Taiping rebels and most other peasant uprisings in Chinese history lies in the unique vision of their leaders. The Taipings were by and large inspired by prototypical Christian ideas, dedicated to eradicating “demons” and “Confucianists.” Theirs was an ecumenical vision with a long-range strategy that aimed to create a brand-new “world order” for “the new times.” It was just such a vision that propelled the rebels to launch a widespread, large-scale assault on the government forces over a vast region of China. They were seldom concerned only with local campaigns. To them, every military campaign served the cosmic purpose of creating a new world order. Within a couple of years, the Taipings moved triumphantly from the back country of Guangxi province to central China, taking Quanzhou, Daozhou, Yuezhou, Hanyang, Hankou, and Wuchang. By the end of 1852, the Taipings had developed an army of over 200,000 troops. In April 1852, the Taiping high command met in Daozhou to map out a grand strategy. It was decided that instead of going straight to Beijing, the Taipings would aim to capture Nanjing toward the mouth of the Yangzi River.

The response from counterinsurgency forces on the government side was miserably ineffectual. To begin with, the Qing troops were not prepared to deal with rebellions of this size and ferocity. Yet the strategic miscalculation on the part of the court that the Taipings were local by nature and therefore best left to be dealt with by local magistrates created a magnificent opportunity for the rebels to charge forward without being seriously impeded. At the beginning of 1853, the forces of the Qing were heavily deployed in the provinces of Henan and Zhili in north-central China, a clear indication that the government had no clue about the Taipings' strategy of striking east first. In early February 1853, Hong Xiuquan led an army of over 100,000 eastward down the Yangzi River, assisted by an armada of over 10,000 water craft of different sizes. The rebels cut through feeble opposition at various cities along the way. A month later, they arrived at the outskirts of the city of Nanjing. Days of intense fighting finally broke the defenses, and the rebels established Nanjing as the capital of a new political regime with Hong Xiuquan at its head.

Shaken by the stunning defeats of its forces, the court in Beijing settled on a strategy to sandwich the new Nanjing regime. The plan called for the setting up of two massive army groups, the Southern Front and the Northern Front, that would presumably squeeze Nanjing in the middle. To counter this formidable challenge, the Taiping rebels responded by launching two major campaigns simultaneously to relieve the pressure. The first was the Northern Expedition, which aimed to capture the imperial capital of Beijing. The second was the Western Expedition to wipe out the enemy forces in the central provinces and divert the troops besieging Nanjing. The Northern Expedition got under way soon after the rebels settled down in Nanjing. In May 1853, Lin Fengxiang, Li Kaifang, and Jie Wenyuan of the Taiping cause led more than 20,000 elite soldiers northward, only to be stopped by the mighty Yellow River in Henan province where all the boats along the river had been destroyed by the local magistrates. Undeterred, the rebels moved westward along the south bank of the river in search of a ferry route, which they succeeded in locating several hundred miles further west. After crossing to the north bank, the Taiping rebels penetrated into the Beijing area, capturing Baoding and reaching the outskirts of the capital. There a critical mistake was made. Instead of directly storming into Beijing, a move which could have succeeded, the rebels roamed outside and moved toward the nearby metropolis of Tianjin, thus allowing the government forces to regroup after their initial panic and to organize effective counterattacks. The imperial forces broke the dikes of the Grand Canal to flood the rebel positions. Shortages of provisions, severe weather, and tactical blunders finally rendered the two-year-old Northern Expedition a total disaster, with virtually all the Taiping soldiers and commanders committed to the campaign killed by the government forces.

The Western Expedition fared slightly better. The rebels moved swiftly to capture such strategic choke points as Anqing, Pengze, Hukou, and Jiujiang. While fighting in Hunan, the Taiping encountered their nemesis in Zeng Guofan, whose Hunan Army would be the ultimate victor over the Taipings in 1864. But during the Western Expedition the Taipings beat Zeng Guofan hands down, propelling him to make two suicide attempts in the face of the agony and humiliation of defeat. Unfortunately for the rebels, they were abruptly called back to reinforce the besieged city of Nanjing at the very point that their offensive was succeeding. This effectively ended the Western Expedition in March 1856.

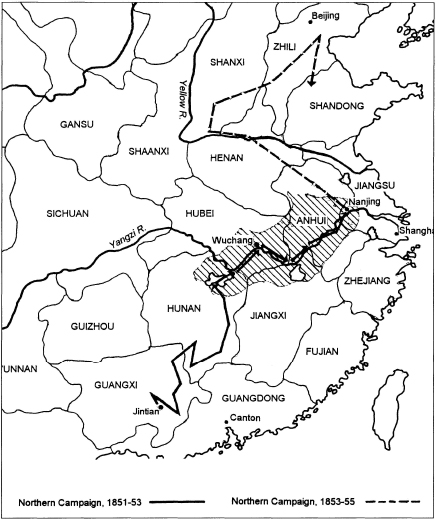

Map 8.1 The Taiping Rebellion, showing main area of Taiping control in 1854. Adapted by Don Graff based upon The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents, vol. 1: History, Franz Michael (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966), map 15.

The year 1856 marks a watershed in the military development of the Taiping Rebellion. A major implosion took place within the Taiping regime. Hong Xiuquan, the Heavenly King of the Taiping Tianguo (Heavenly Kingdom of the Grand Harmony), was believed to be the real younger brother of Jesus Christ. That grand stature gave him enormous power over his followers. But he was not the only prophet in the Taiping camp. Back in 1850, when Hong was temporarily absent from the Taiping base in Guangxi, the Taiping followers began to lose faith in the cause, and trouble started to brew. In a desperate effort to save the situation, Yang Xiuqing, Hong's second-in-command, announced to the world that he could speak on behalf of “God the Father” (tian fu). Yang's stunning announcement secured the unity of the Taiping followers in Hong's temporary absence, but it also created a practical problem. Hong Xiuquan himself was only the younger brother of Jesus Christ, but Yang had made people believe that he himself could now enunciate the will of the father of Jesus Christ. Thus, Yang's words would in theory be more powerful and command more respect than than those of Hong. Yet since Hong's presence as the brother of Jesus was daily and constant, while Yang could only receive “edicts” and instructions from God during temporary trances, Hong acquiesced in the arrangement. The bizarre result was that Yang announced frequently that he was receiving instructions from God so as to restrain Hong and punish him for not having given Yang himself more prestige in the Taiping hierarchy. Hong had to publicly confess his “crimes.” This, of course, became terribly humiliating to Hong, and in 1856 he carried out a bloody coup. Wei Changhui, one of Hong's five kings and Yang Xiuqing's rival, received the order from Hong to carry out the murderous coup in which Yang, his entire family, and several thousands of his security forces were mercilessly liquidated. Wei's hideous killings of the Taiping comrades naturally evoked disgust among the rank and file. Facing pressure from below, Hong Xiuquan eventually pointed the finger at Wei and had him executed. By the end of the year, of the half dozen veteran Taiping leaders, only Hong and an ambitiously independent king named Shi Dakai remained alive. But the implosion had so disturbed Shi that in 1857 he led tens of thousands of the Taiping troops to flee Hong and Nanjing, moving westward to the mountainous area of Sichuan. There he was captured and executed by government forces in June 1863.

Facing increasingly alarming signs of military crisis, Hong Xiuquan decided to promote a new military high command. Another half dozen or so of the young commanders, most in their twenties and thirties, were elevated to the highest military posts. Among them were Chen Yucheng, Li Xiucheng, Li Shixian, and Meng De'en. These young commanders proved to be among the most brilliant military strategists and tacticians in modern Chinese history. Starting in 1856, they led huge peasant armies to break the siege of Nanjing, the Heavenly Capital of the Taiping regime. By 1858 the two major Qing army groups designed to sandwich Nanjing, the Northern Front and the Southern Front, had met serious challenges. Led by the twenty-three-year-old prodigy Chen Yucheng, the Taiping soldiers effectively demolished the Northern Front by the end of 1858, thus greatly relieving the pressure on Nanjing. In May 1859, the Southern Front was also destroyed by Taiping troops after a superb game of deception and joint operations.

Yet the days of the Taiping were numbered, despite the many impressive military victories they had scored against government forces by the end of 1859. What the Taipings had thus far fought against were mainly the imperial armies of the Eight Banners and the Green Standards, which were notorious for their incompetence and corruption. After the Northern Front and the Southern Front were beaten by the Taipings, the Qing court was forced to place the fate of the empire into the hands of newly formed militia armies led by examination degree-holders and local elites (gentry). The most important of these forces was the Hunan Army led by the scholar-general Zeng Guofan. Zeng was appointed military governor of the Jiangsu and Jiangxi area in the wake of the demolition of the Southern Front in 1859. The Taipings were no match for Zeng, who combined brilliant military strategy with unique methods of training and leadership. Due to increasing friction between the Taipings and the Western powers in the coastal areas, Zeng was able to enlist the help of foreigners in Shanghai and other treaty ports to harass the rebels. The first important victory came to Zeng when he outmaneuvered the Taipings and captured the key city of Anqing in September 1861, which left the vast upstream flank of Nanjing extremely vulnerable to attack. In February 1862, Zeng Guofan launched his final campaign against Nanjing. It lasted over two years, with many bloody battles and troop movements on an epic scale. As the noose tightened around Nanjing, Hong Xiuquan died suddenly of illness on June 1, 1864, leaving his sixteen-year-old son as the new head of the Taiping regime. Fifty days later, on July 19, 1864, Zeng Guofan's artillery barrage finally destroyed a major section of the city wall. The government forces flooded into the city and, amid scenes of slaughter, all of the major Taiping leaders were captured and executed. The fifteen-year ordeal of the Qing dynasty was finally over.

THE MILITARY DIMENSION OF THE TAIPING MOVEMENT

The Taiping Rebellion was simultaneously a military movement and a social revolution. As a military movement, the Taipings closely tied their religious fanaticism to troop organization and command. This religious ferment greatly enhanced the cohesiveness and unity of the Taiping troops and created a strong sense of purpose while fighting the “demons” represented by the Qing court and its armed forces. It is the single most important factor behind the great Taiping victories in the early years of the war. As the Taipings began to settle in the lower Yangzi River area, however, life became more comfortable. The religious ardor was gradually replaced by lax discipline and a taste for secular pleasures, which contributed greatly to the ultimate demise of the cause.

Yet thoughout the war the Taipings posed a formidable military threat to the court. In fact, the rebels consistently routed the government forces. Even as late as 1862, the Taiping generals were able to defeat enemy forces twice the size of their own armies. Looking closely at the strategies and forces of the Taipings, we discover a system unique in the history of Chinese peasant rebellions.

First of all, the Taipings placed civic virtue and puritanical discipline at the top of their military indoctrination. The “Taiping Rules and Regulations” (Taiping tiao gui), the military training manual of the movement, specifically stipulated that all Taiping soldiers were expected to “obey the heavenly regulations” and “cultivate good morals”; they were not to smoke tobacco or drink wine.1 The same manual assigned men and women to separate military units and strictly prohibited sexual relations. Looting was not permitted, which made the Taipings popular in territories beyond their original home base in Guangxi. Strict regulations required harsh punishments for violators; the most common punishment was beheading.

What did this extreme, puritanical austerity mean for the military effectiveness of the Taipings? Of all the important ramifications, nothing stands out so much as the extreme flexibility and agility of the Taipings' troop movements. As a Taiping company commander explained to a French officer at the time, “The days of distress followed the days of opulence and we found it all quite natural. It was just that which made us superior to the imperial troops. When they camp, they need big installations. They have to have fortifications, tents, and so on. We went straight on. If there were houses we stayed there, if not, we slept under the stars.”2

The second unique feature of the Taiping military organization was its utilization of women soldiers in combat units. Since all men and women were regarded as brothers and sisters under God, no one was supposed to face discrimination because of their sex. A woman under the Taiping regime thus had the same privilege or obligation to serve in the army that a man did, as well as the same right to own her own land. To Hong Xiuquan and his associates, the employment of women combat soldiers also provided a powerful ideological weapon against what they regarded as the chief spiritual evil: Confucianism. In the orthodox Confucian order, women were expected to stay indoors and were not supposed to engage in outside social activities, let alone serve in the military. In fact, the prevailing practice of footbinding essentially rendered women useless in any type of military service because they were unable to run. The use of women in Taiping combat units was in direct defiance of the Confucian order, and it was possible because the women of the Hakka minority did not practice footbinding. In the key battles at Guilin and Changsha, Taiping women soldiers performed with valor and were highly praised.

A third unique feature of the Taiping military was that its main organizational principle was the soldier-peasant model. All citizens in the regime were required to serve as soldiers. And conversely, all layers of society were structured according to the military command hierarchy. Although soldiers were paid slightly better than farmers, the ethos and tempo of a farmer's life became the same as for a soldier. Farmers as well as soldiers were subjected to a rigid military command structure. In the Taiping system, “A corporal commands four men. A sergeant commands five corporals…. A colonel commands five captains…. A corps general commands five colonels; altogether he commands 13,125 men.”3

The Taiping army was also remarkable for its innovative tactics. Among the most famous was the excellent use of tunnelling and demolition. This was primarily due to the personal experience of Yang Xiuqing, the Taipings' second-in-command before 1856, who had been a coal miner before the uprising and knew the power of explosives underground. The Taipings produced the best demolition experts in nineteenth-century China. In addition, the Taipings were among the first in modern China to utilize mass war propaganda in (quite literally) demonizing their enemies. These hysterical and xenophobic efforts at consciousness-raising against the Manchu rulers were for the most part quite effective.

Despite all these advantages enjoyed by the Taiping military, the peasant rebellion was eventually quelled. Ironically, the Taipings were defeated not by the regular army of the imperial court but for the most part by an exceptionally intelligent scholar-stateman who saw all the flaws of the emperor's troops and who instead envisioned and commanded a much more effective “gentry” army that eventually defeated the once-invincible Taiping troops.

ZENG GUOFAN'S VIEW OF THE QING MILITARY

Facing a momentous peasant rebellion inspired by prototypical Christian ideals, the ruling Qing dynasty would have collapsed in the mid-nineteenth century had it not been for the military genius of a prominent Confucian scholar, Zeng Guofan (1811–1872). Zeng and his military thought occupy a unique place in Chinese military history. It is true that there have been many military strategists and theorists throughout the annals of Chinese statecraft, and Zeng Guofan himself may not have been the most brilliant or original, but he was exceptional in the sense that he was one of the very few who were both theorists and practitioners of military doctrines. Few influential strategists have had the opportunity of creating, training, and commanding a huge and powerful army based upon self-taught or self-synthesized principles of war.

Zeng Guofan began his career as an outstanding military strategist not because he knew what to do, but rather because he painfully realized what not to do: Whatever the imperial army represented, he must tenaciously avoid. At a time of grave crisis for the dynasty that he supported, the regular armies of the Qing court had proved stunningly inept and ineffectual. Zeng's analysis of the Qing imperial army is classically poignant. In his view, the then current military system had the following five failings:

Hereditary Bureaucratic Military Force

The strategic core of the Qing dynasty's military consisted of two basic forces, the Manchu banners and the Chinese Green Standard Army. The troops served for life or even on a hereditary basis, with no channel for bringing in new blood from outside. As a result, these once-powerful fighting forces had deteriorated into a decadent cohort of unfit soldiers and officers by the time of the Taiping Rebellion. As a Western observer of Zeng's time noted, “The men were as heterogeneous as their clothes. Old and young, strong and decrepit, half-blind or whole deaf, none seemed too miserable objects for service.”4

Failure to Come to the Support of Comrades in Trouble

This piqued Zeng's strongest sentiment against the imperial army. “When I daily ponder over our current military forces,” Zeng wrote, “the most shameful and hateful of all aspects is what is expressed by the four characters bai bu xiang jiu [the defeated cannot expect rescue].”5The reason for this fateful shortcoming, Zeng argued, was the way the court assembled military units in time of war. Fearful of entrenched, personally bonding loyalty between a superior commander and his soldiers, the Qing court constantly broke up solid troop units and regrouped the men into new ones. Thus, the newly formed units were made up of strangers who felt no obligation to help one another. When a battle occurred, units under the same commander failed to cooperate: “One unit of soldiers is defeated, bleeding like a river, yet the other unit nearby, watchfully smiling, stays put, with no intention of offering help and rescue.”6

Jealousy

This went far beyond the normal realm of interservice and interunit rivalry. Instead, it had become a deadly disease of the Qing army. In Zeng's analysis, low military pay and insufficient training were responsible for this problem.

Lack of Discipline and No Concern for “the People”

One historian has noted that “the people of north China feared the Imperial troops more than they feared the rebels.”7 The danger of indiscipline lay not just in the ineffectiveness of the troops, but in the alienation of the people from the government, preparing the way for the dynasty's demise.

Lack of Civilian Control

The banners and the Green Standard Army consisted of professional military men who had grown arrogant and shortsighted. During a crisis such as the Taiping Rebellion, they had proved themselves worthless. Yet it was difficult to impose civilian guidance to counteract the ignorance and incompetence of the imperial army.

ZENG'S MILITARY INNOVATIONS AND THE DEFEAT OF THE TAIPINGS

The profound defects of the Qing military provided Zeng with a clear sense of direction and purpose when recruiting and commanding an army of his own. Zeng's genius is largely due to his ability to see the true picture (which required a fair amount of courage in the Chinese scheme of authoritarian imperial bureaucracy), and to act upon this picture to incorporate his own remedies into a brand-new fighting force created for the specific purpose of overcoming the court's most formidable enemies. The remedies Zeng worked out in the 1850s and 1860s were nothing short of revolutionary. Indeed, they made Zeng the father of the modern Chinese military system. The specific reforms were as follows:

First, Zeng Guofan completely overhauled the concept of “braves” (yong), and made these troops into a first-rate force. There had been three layers in the Qing military system: “soldiers” (bing), “braves” (yong), and “militiamen” (ding). The soldiers were professional, full-time military men such as the banner and Green Standard troops. They were fully supported by the court, with stable financial backing and regular military structures. They were designed to be the strategic core of the Qing army. The braves were recruited by the court, mostly during times of prolonged rebellion or civil disturbance on a grand scale, as part-time servicemen fully financed by the government. But the braves were much less privileged than the regular troops and their stipends varied a great deal. The militiamen were even less formally organized. They were local by nature. Recruited and trained by local luminaries and gentry heavyweights, militiamen acted as a local security force for the neighborhood or village. Their military usefulness during a time like the Taiping Rebellion was inconsequential, but they could help maintain the Confucian moral order and keep local toughs under control.

When the Taipings marched north through his home province of Hunan in 1852, Zeng was at home fulfilling the filial duty of mourning his mother's death. Burdened with the task of protecting his birthplace from the rebels' ravages, Zeng concluded that the regular soldiers were good for nothing and the militiamen undependable. He opted instead for the braves. It was this choice of yong recruits that enabled Zeng Guofan to create the greatest army of late imperial China: the Hunan Army.

The Hunan Army was an army of recruits. By strengthening this element, Zeng aimed to break with the hereditary character of the Qing standing army. Zeng recruited peasants from the mountain areas of Hunan. His recruiting standards became famous. Recruits were to be “skillful, young and strong; the simple, plain and peasant-like are the best. Never recruit those who are slick, who are urban Philistines, and who are officious and pretentious.”8 All these bad qualities, in Zeng's view, were prevalent among the regulars.

Second, Zeng Guofan steadfastly stressed the importance of civilian command over the military. This reflects the ideal of “excellence in both literary and martial skills” (wen wu shuang quan). Zeng himself is revered as the quintessential scholar-general: a physically unimpressive scholar applying his brilliant intellect to the command of an awesome and ferocious fighting force. Zeng used many fellow literati as his top generals and officers of senior grade. In his Hunan Army, over half of the officers had previously been literary candidates for the imperial examinations; the top 10 percent of the army's officer corps were literati who had already passed an examination. In fact, only at the bottom of the officer ranks did the military candidates outnumber the literary candidates.9 All the prominent leaders of the Hunan Army and other forces created later on the same pattern were without exception members of the literati class. The Hunan Army was in fact an army of peasants led by literati, as if the U.S. Army were being run by Ph.D.s in the humanities.

Third, and perhaps the most significant element in Zeng's military thought and practice, was the cultivation of moral character in all military personnel. This was strictly along the lines of Confucian virtues and mores. For the general, benevolence toward both his soldiers and the people was crucial. He had to be upright, generous, diligent, and caring, both a righteous ruler and a gentleman of good personal attributes. Among the various strands of Confucian virtues, the most important to Zeng was the value of family. A superior officer was expected to act like a father to his soldiers. Zeng often communicated with his officers in such a fashion. The establishment of a strong relationship between a benevolent superior officer and his subordinates was deemed essential in accomplishing military goals. This hierarchical structure of human relationships rooted in Confucian ethics poses a sharp contrast with the ultraegalitarian rigidity of the Taiping military order.

Instead of being motivated by an abstract ideology like that of the Taipings, a soldier in the Hunan Army was taught to fight not necessarily for the court, nor for his province, nor even for Zeng Guofan, but for his family, his parents, his brothers and sisters. To strengthen the connection between a soldier on the move and his family back home, superior officers were given the power to send a significant portion of a soldier's stipend directly to his family. Misconduct and disgraceful behavior such as desertion or cowardice in battle was interpreted as bringing shame on the family and the clan.10 The cultivation of a morally sound fighting man was the essence of Zeng's military reform.

Fourth, a sweeping reform of military finance was indispensable to Zeng's efforts. Ever fearful of concentrating too much power in the hands of a military commander, the Qing court had devised a system of checks and balances in military finance. The banners and the Green Standard Army were all paid for by the court, but there were independent stipend commissioners to decide the scale and distribution of soldiers' pay, so that commanding officers had little to do with the financial well-being of their subordinates. The Hunan Army was partly funded with government money at the outset, but gradually developed complete financial independence through such means as imposing taxes (lijin) on goods in transit. With this change, a general could decide the pay of his own subordinates. And Zeng chose to pay his troops extremely well. At a time when a farm hand earned five taels of silver per year, an infantry soldier of the lowest grade in the Hunan Army was paid fifty-one taels of silver each year. A battalion commander made more than ten times what an infantry soldier did.11 Even though moral indoctrination played the greatest role in Zeng Guofan's system, such high financial reward greatly enhanced the morale of the troops. But most important, high pay also had a strong moral utility: A well-paid soldier was less likely to loot, gamble, or commit other crimes or unethical deeds.

Following the salient tradition of classical Chinese military doctrine, Zeng Guofan placed supreme importance on the quality and power of commanding generals. Zeng had a reputation for selecting the best people for such posts. Perhaps the most unique aspect of the Hunan Army was the unparalleled control a commander had over his subordinates. It started with recruitment. Zeng Guofan recruited his protégés as army commanders, these army commanders then went on to recruit their own protégés or friends to be division commanders, who also recruited their own people. Commanders at each level had absolute authority over the level immediately below them, but the authority of higher commanding officers could not jump over intervening levels. This reform is of great significance because for the first time in several hundred years, a system of “state-owned” military was beginning to give way to a “general-owned” military. Indeed, Zeng and his many protégés could easily have made themselves independent warlords had they so desired.

Since the Taipings were mostly interested in a war of movement, Zeng's strategic approach tended to favor positional warfare. The key concepts that Zeng emphasized were calmness (wen) and being the “host” (zhu). Calmness meant the time-honored strategic quality of being cautious, planning well, and being rooted in one place. “In a battle,” Zeng ruminated, “one should be calm and steady, which is the first thing one should be; only then should one seek for changes.”12 The strategy of calmness was closely linked to the concept of the host, because Zeng believed that to fight in someone else's territory as a “guest” (ke) has many disadvantages that can easily lead to defeat. To grasp the position of the host requires utilizing to the fullest extent the local support of people from your village, county, or province. It also involves creating situations on the battlefield to which the enemy is forced to respond. The host is always the side that determines the terms of the fight. Zeng's wen and zhu methods would become a prominent feature in twentieth-century Chinese counterinsurgency campaigns, including the Nationalists' efforts to wipe out the Communist forces in the Jiangxi Soviet.

Zeng Guofan had a specific military mission: to defeat the Taiping Rebellion and save the Qing dynasty. In this he succeeded with extraordinary gallantry and efficiency. While the well-trained, well-organized Taipings carried out their social and military campaigns with puritanical rigidity, ideological fanaticism, and utopian collectivism, Zeng trained and commanded his armies with a strong emphasis on family ties, individual responsibility, flexible yet responsible discipline, enhanced military pay, respect for intellectuals serving the army, and a strong bond between officers and soldiers. In the final analysis, Zeng Guofan won and the Taipings lost precisely because the Taipings did not understand the power of human relations as Zeng did. A deep appreciation of the Chinese way of human relations is the core of Confucianism. In this sense, the defeat of the Taipings may be viewed not just as the rout of utopian radicalism, but also as the triumph of Chinese tradition.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

The Taiping Rebellion has attracted a great deal of scholarly attention. The single most comprehensive study of the conflict, dealing with both the Taipings and their opponents, is Yu-wen Jen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973). Another important work is Franz Michael in collaboration with Chung-li Chang, The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966–1971); this was published in three volumes, the first providing an historical overview and the other two offering translations of Taiping documents with notes and commentary. There are also a number of specialized studies covering particular aspects of the Taiping movement, including Vincent Y. C. Shih, The Taiping Ideology: Its Sources, Interpretations, and Influences (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1967), and S. Y. Teng, The Taiping Rebellion and the Western Powers: A Comprehensive Survey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971). The foreign contribution to the suppression of the Taipings is highlighted in Richard J. Smith, Mercenaries and Mandarins: The Ever-Victorious Army in Nineteenth Century China (Millwood, NY: KTO Press, 1978), while Jonathan D. Spence, God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996) focuses on the Taiping leadership circle and the mind of Hong Xiuquan himself.

The preeminent treatment of the “gentry” armies opposing the Taipings is Philip A. Kuhn, Rebellion and Its Enemies in Late Imperial China: Militarization and Social Structure, 1796–1864 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970); another useful study is Stanley Spector, Li Hung-chang and the Huai Army: A Study of Nineteenth Century Regionalism (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1964). Mary Clabaugh Wright, The Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism: The T'ung-Chih Restoration, 1862–1874 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957) considers reform, foreign relations, and the suppression of the mid-century rebellions from the standpoint of the Qing court in Beijing. For more information on the other rebellions that overlapped with that of the Taipings, see S. Y. Teng, The Nien Army and Their Guerrilla Warfare, 1851–1868 (The Hague: Mouton, 1961); Wen-djang Chu, The Moslem Rebellion in Northwest China, 1862–1878: A Study of Government Minority Policy (The Hague: Mouton, 1966); and Elizabeth Perry, Rebels and Revolutionaries in North China, 1845–1945 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984).

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The monographic literature on the mid-century rebellions and their suppression, extensive as it is, still has several notable gaps. The Miao revolt in Guizhou and the Muslim rising in Yunnan, for example, have been largely neglected. The time is also ripe for a reassessment of Zeng Guofan and the other scholar-generals who defeated the Taiping. The most recent book-length, English-language biographies of Zeng and his important associate Zuo Zongtang were published in 1927 and 1937, respectively.13

NOTES

1. “Taiping Rules and Regulations,” in The Taiping Rebellion, vol. 2, Documents and Comments, ed. Franz Michael (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1971), 139.

2. Quoted in S. P. Mackenzie, Revolutionary Armies in the Modern Era: A Revisionist Approach (London: Routledge, 1997), 82.

3. “The Taiping Military Organization,” in The Taiping Rebellion, vol. 2,133.

4. Mary Clabaugh Wright, The Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism: The Tung-Chih Restoration, 1862–1874 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957), 197.

5. Letter from Zeng Guofan to Jiang Minqiao, in Zeng Wen Zhenggong quanji—shouzha [Complete Works of Zeng Guofan—Letters], vol. 2 (Hunan: ChuanZhong, 1934).

6. Letter from Zeng to Li Shaoquan, in Zeng Wen Zhenggong quanji—shouzha, vol. 2.

7. Wright, Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism, 203.

8. Zeng Guofan, “Zhao mu zhi gui” [Rules of recruitment], in Zeng Wen Zhenggong quanji—za zhu [Complete Works of Zeng Guofan—Miscellaneous Writings], vol. 2 (Hunan: ChuanZhong, 1934).

9. Wright, Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism, 200.

10. Gao Rui, ed., Zhongguo junshi shilue [A brief military history of China], vol. 3 (Beijing: Military Science Press, 1992), 39.

11. Wang Dingan, Xiang jun zhi [Annals of the Hunan Army] (Changsha: Yuelu shushe, 1983), 339.

12. Letter from Zeng to his family (dated fourth day of lunar first month, 1858), in Zeng Wen Zhenggong jiashu [Zeng Guofan's letters home], vol. 5 (Hong Kong: Hongwen shuju, 1953).

13. William James Hail, Tseng Kuo-fan and the Taiping Rebellion, with a Short Sketch of His Later Career (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927); W. L. Bales, Tso Tsungt'ang, Soldier and Statesman of Old China (Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh, 1937). A few more specialized volumes have published in recent years; one example is Lanny B. Fields, Tso Tsung-t'ang and the Muslims: Statecraft in Northwest China, 1868–1880 (Kingston, Ontario: The Limestone Press, 1978).