7A Caste: Social Relations, Cultural Formations

In Part I, we have looked critically at deity, texts, myth, ritual and worship, and teachers and founders, often considered to be key ‘features’ of a (world) religion. We have discovered how these categories often group together very diverse phenomena. This prompted us to develop other ways of thinking about religion and religious traditions in South Asia and beyond. In this chapter we look at a topic that at first sight does not appear to fit with this approach: caste. Unlike the other categories, which are held to be common across religious traditions, caste is often seen to be quintessentially Indian, if not the grounding principle of Hinduism (Dumont 1980). In Chapter 7B, which will start Part II of this book, we shall explore how this view of Hinduism as caste-based developed in the modern period, although, as always, with older roots. Here in Chapter 7A,* to conclude Part I, we explore the diversity of social relations and cultural formations that are covered by the umbrella term ‘caste’. In doing so, we shall look at both historical and ethnographic approaches and ideological systems. This will help us to contextualize how the umbrella term came to be used, as well as to realize that the diverse phenomena that it covers were and are historically and socially produced, just like other social formations across the world.1 This will help us to be open to a much more flexible way of understanding such social phenomena, and the many ways in which they are related to the equally complex term, ‘religion’.

Case Study: The Meos of Mewat

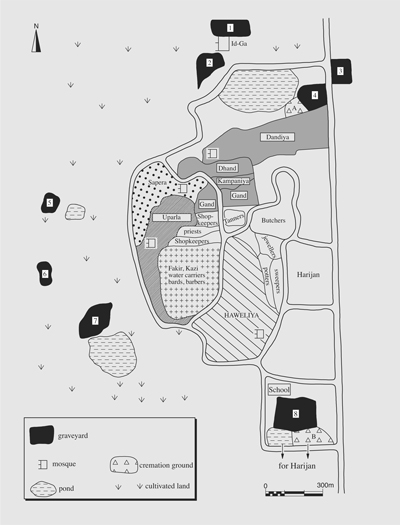

Figure 7A.1 shows a map of an Indian village, drawn in the 1980s. This village, Bisru, in northwestern India, was where the French anthropologist, Raymond Jamous, lived at the time. He was studying the kinship relationships of a particular caste group, the Meos, who integrated him into their own kin networks as the bhai (brother) of Abdulaziz, a university-educated Meo, his first contact there. The region in which Bisru is located is called Mewat, ‘the land of the Meos’. It forms a triangle between Delhi, Agra and Jaipur. This is said to have been the territory of the Pandavas, the cousins of the great Mahabharata epic. An important Meo caste myth, the Pandun ke kara, identifies the Pandavas as their own caste ancestors. Like the Pandavas, they see themselves as a warrior and ruling caste, describing themselves by the regional term for ruler, that is, Rajput. Meos are one of the most important groups in the Mewat region and have spread out beyond it in both India and Pakistan. You might wonder why …

Figure 7A.1 Map of Bisru village (reproduced courtesy of Sophie Archambault de Beaune).

Key: Bard (Mirasi): Muslim low-caste singers who retell the past glories of the family they serve at life-cycle events;

Fakir: here, specific caste of Muslim funeral priests (similar to Hindu mahabrahmin funeral priests) – generally, Muslim wandering ascetic; Harijan: here, ‘untouchable’ leatherworkers and sweepers;

Id-Ga: the mosque kept for Muslim festivals such as Id/Eid;

Kazi: Saiyads/Sayyids, descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, usually regarded as higher status than Indian-origin Muslims;

Priests: here, (Hindu) Brahmins; Shopkeepers: here, Baniyas (see text).

The map shows that this village, like many in South Asia, is divided into sections. The labels in the different sections are the names of the different castes or segments of castes who live in that part of the village. You might already be looking to see where the Meos live and wonder why you cannot find the label. What you will find are the names of the seven Meo lineages of the village: Haweliya, Dandiya, Dhand, Gand, Kampaniya, Sapera and Uparla. They in fact fall into three groups, centred around three ‘lineage houses’ in the village where their respective caste-segment panchayats are held. The panchayat is the key local group that sorts out disputes, makes decisions about members who go against the caste ritual and social rules, organizes festival processions and so on. Such caste-related panchayats are an essential part of the social fabric of South Asia. Does this then confirm the view that caste is an essential and unchanging aspect of Hinduism?

Task

As you look at the map and key carefully and think about Abdulaziz’s name, how many clues can you find that disrupt or at least cause you to question this view? How many different groups can you locate in this village? What other questions would help you understand social groupings and relations in this village and beyond?

Raising Questions

Perhaps your first query will have been: If caste is basically a feature of Hinduism, why are there so many mosques in this village, why does Abdulaziz have a Muslim name and why are there Meos in Pakistan? According to Jamous (2003: 17), ‘The Meo themselves say that they are at once a caste and a Muslim community.’ This clearly suggests that, at least for the Meo, caste and Muslim identity are not felt to be incompatible. We explore this below. Here we note that in this village the Meo are what anthropologists call the ‘dominant caste’, the most important group in terms of both numbers and status. Locals themselves identify this village as a Meo village, by contrast with other villages in the area where other similar status caste groups, such as (Hindu) Jats or Thakurs, are dominant. The particular dominant caste acts as the jajman in the village or area, the patron of the other castes who render service to them. Can you now identify any of these service castes from the map?

Such service may be daily – very low-caste sweepers remove waste from outside Meo and other high-caste houses, for example. Alternatively it may be provided on ritual occasions – travelling Muslim Mirasi lowish caste bards sing the myths of Meo families at birth and marriage; Hindu brahmins from outside Bisru provide ‘deeper’ genealogies for the Meo, confirming their right to power. Service castes in Bisru, as elsewhere, are divided into clean castes (such as the Mirasi) and unclean castes (including the sweepers); we shall return to the reasons later. See if you can identify other service castes in Bisru, their status and their religious affiliation as you read the rest of this chapter.

Looking back at the map and still querying the caste equals Hindu model, you may also have wondered why one section has funeral priests, apparently high status descendants of Muhammad, water carriers, singing bards and barbers all living together. In this village they are all Muslim (again disrupting the Hindu paradigm) and are also clean service castes in relation to the higher status Meos. Is this then just a Muslim village?

On the other hand, you may have noticed that there are both burial and cremation grounds, the former used by Muslims, the latter generally by Hindus. You may have spotted the brahmin priests and wondered which other groups in the village are Hindu. And whether the Harijans, or untouchables, regard themselves as Hindu, Muslim, or neither. You might also wonder if people who identify with other religious traditions live in this village or the surrounding area and how these different social/caste groups with varying religious affiliations relate to one another locally and in terms of larger regional and global issues. To explore these issues we are first going to look at three different terms that have all fed into the English umbrella term ‘caste’. They are not simply interchangeable but are sometimes used as if they are. To show this, we shall interrogate these categories in terms of relations in and around Bisru, centring as they do on the Muslim Meos and their negotiations for stability through the changing politics that have affected local life.

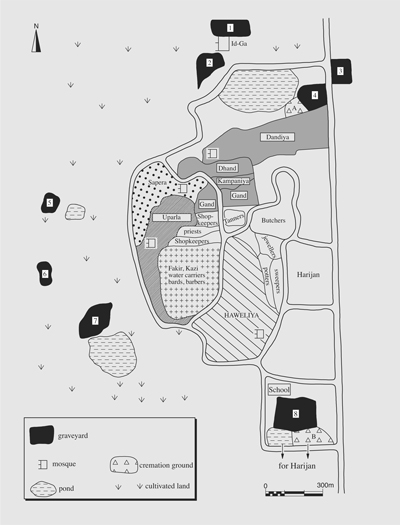

Casta, Varna and Jati

The word ‘caste’ does not have a simple equivalent in Indian languages. It is an outsider term, a European mode of classification. It comes from the Portuguese word ‘casta’, used primarily during the Iberian colonization of South America to hierarchize different ‘races’ [Europeans, various types of Creole, (local) Indians, Africans and so on]. Early Portuguese travellers in India may have been interested in applying similar notions when they spoke of ‘Brahmenes’ and others, although whether this was assumed to be a fundamental feature of Indian society by these travellers has been questioned by scholars (see Dirks 2001: 19). However much this was the case, as we move into the British colonial period the idea of caste as a natural hierarchical feature of Indian society – similar to the casta taxonomies of colonial South America – became increasingly entrenched. The historian Nicholas Dirks explores the development of what he calls the ‘ethnographic state’. Interested in categorizing its subject people for more effective rule, colonial officials used tools such as the census (see also Chapter 9), as well as regional Gazetteer reports and photos (Figure 7A.2) to gain knowledge of caste groupings. Dirks argues that this colonially derived casta view of caste as a comprehensive system also became the model for more recent anthropological accounts of caste, driving scholars to look for the fundamental and all-embracing system that distinguished Hinduism as such. The famous French anthropologist, Louis Dumont, provides a key example.

Figure 7A.2 Casta-type photographs under the Raj. These two photographs appear in William Crooke’s The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, published in Calcutta, 1896. The one on the left is labeled ‘Brahmin Pandit’, the one on the right ‘Two Chamars’ (C.A. Bayly 1990: 293). They are typical of the scientific, taxonomic approach of the ‘ethnographic state’. They are also quite strongly reminiscent of eighteenth-century South American ‘casta’ paintings, a genre that attempted to record and classify different groups in an elaborate racial hierarchy (see Katzew 2004 for examples). RAI 2722 ‘Two Chamars’; RAI 2723 ‘Brahmin Pandit’. Reproduced with permission of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

In his classic study, Homo Hierarchicus, Dumont (1980) located Brahmins at the top of the hierarchy of castes, by virtue of their superior ritual purity. The lower down the hierarchy, the greater the impurity, untouchables at the bottom being those deemed the most polluting. Dumont stressed that, in traditional Indian societies, even the king’s power was secondary to the brahmin’s, as it was dependent on the legitimation of the brahmins who performed the state rituals necessary to sanctioning the king’s position. Similarly, he held that this model worked at more local levels, the brahmins being available as the prime ritual specialists because of their superiority as the purest caste. In Bisru, there are some indicators that might appear to confirm Dumont’s view, such as the polluted status of the untouchable castes, but there is an immediate problem with the brahmins who are certainly not the prime ritual specialists for the Meos, even though they recognize the Meos’ high status. It would be easy to suggest that this is because the Meos are Muslim, and so ‘disrupt’ the ‘proper’ functioning of the caste system. As we shall see below, this approach may be seen to underlie that of both Muslim and Hindu reformers who tried to work on the Meos from the early twentieth century. Below we shall indicate a different approach. Here, however, we note that Dumont’s view, although much criticized (see, for example, Dirks 2001: 4–5; Appadurai 1986, 1988; Sharma and Searle-Chatterjee 1994), remains influential, partly because it was also informed by our second key term, varna.

‘Varna’ is a Sanskrit term that can mean ‘colour’. It is frequently translated as ‘caste’ but this can be very misleading. In brahminical texts, it refers precisely to the four ideal social groups into which society is to be divided. Its mythological basis is to be found in a hymn from the Rig Veda, the ‘Purusha Sukta’, which tells of the sacrifice of the primal cosmic man (purusha). ‘His mouth became the Brahmin; his arms were made into the warrior, his thighs the People, and from his feet the servants were born’ (Rig Veda X.90.12, see Doniger 1981: 31). Like the casta view, it too forms a total system, an ideology, not just a social framework, in which the upholding of varna is thought to uphold order in the cosmos as a whole. Ritual, social and cosmic order (dharma) are guaranteed by people fulfilling the specific duties (dharma) of their own varna: the brahmins2 teaching the Veda, the kshatriyas protecting and ruling the kingdom, the vaishyas producing wealth and the shudras providing service to others. These are spelled out at length in the Dharma Shastra texts such as Manu (c. second century CE, Olivelle 2004: 18–25). Later texts such as the Bhagavad Gita ground the whole system in the Supreme Lord, Krishna, who says: ‘The four-varna system was brought forth by Me, in accordance with qualities (gunas) and actions’ (4.13; on these varna-related qualities, see Box 7A.1).3 Given that this is a Hindu devotional text, and has grown in importance as a defining text of Hinduism since the nineteenth century, it seems reasonable to assume that the ‘caste system’ is indeed the backbone of Hinduism, and that it is rightly seen as a comprehensive one. In addition, the varna system has been used in public rhetoric through the centuries, not least because it represents the interests of those who have promoted it, the brahmins and also, because they have seen it to be in their own interest, Hindu kings. Even Muslim rulers in India have presented themselves as protectors of the four varnas and dharma, using the ideological language of their subjects to articulate their concern to preserve a correctly functioning social order to the benefit of all (Laine 1999; Chattopadhyay 1998).

In Gita 4.13, Krishna links the varnas with actions and ‘qualities’. The ‘qualities’ refer in context to the three gunas, the three ‘strands’ or constituents of mind-matter (prakriti). These are:

These combine together in different proportions, in food, speech, varna, rituals, gift-giving and so on, every aspect of material life. Only the self (atman) is not affected by them. Brahmins, kshatriyas and so on each act according to their own natures and the gunas associated with them (18.41). In terms of food, eating pure sattvic food (which has a good flavour, is mild and easy to digest, such as rice) leads to good health, long life and so on (17.8), whereas the passionate rajasic crave pungent and spicy food leading to sickness, and those tamasic by nature eat leftovers and food unfit for ritual offerings (17.9–10). And so on with the whole of material life. In the Gita, the wise person understands that the self transcends all this, and dedicates all action to Krishna, the Supreme Self.

Yet three observations of life in India (and elsewhere in South Asia) show the problems of applying varna directly to social life. First, although there are only four varnas, in actual fact there are thousands of different castes. Bisru itself has at least fourteen labelled on the map, and different regions across the subcontinent have many different local groupings. Second, the varna system does not include the so-called untouchable castes, whose members number hundreds of millions and are themselves divided into many hierarchized groups; Chamar leatherworkers now rank above sweepers in Bisru, as we shall see below. Third, currently and historically many groups have simply not been part of the caste system in their local regions at all. The so-called Tribals are a case in point. To cater for these last two vast groups the categories of Scheduled Castes and Tribes were created in Indian law;4 a different scheme was used in Nepal (see later). Yet the Meos themselves, now a Muslim Rajput high status caste in the Bisru region, were, according to one of their own origin myths, bandits, outside the local social system and preying on it. Although historically it is unclear when they achieved Rajput status, it does seem that Meos in different lineages founded or took over key villages around which locally functioning networks of caste became (re-) organized, notwithstanding the Muslim names and life-cycle rites used by the newcomers who ran the local scene. They were not alone in so doing, either in Rajputana (modern Rajasthan) or elsewhere in the subcontinent. For detailed historical work on how different groups gradually became absorbed into what we might call ‘organized caste society’ in eighteenth-century south India, see Susan Bayly’s (1999) excellent study.

We have then started to see why both ‘casta as system’ and ‘varna as ideology’ give us problems when we look at ‘real life’. Perhaps our third term will help us clarify the umbrella term ‘caste’ a little more. ‘Jati’, literally ‘birth’ in Sanskrit, also means ‘type’ or ‘specific category’. It has the merit of having modern Indian-language equivalents reflecting long-standing indigenous use: ‘zat’ in Punjabi, ‘jat’ in Hindi/Urdu, for example. It too is frequently translated as ‘caste’ and is often associated with anthropological approaches. The social anthropologist, Roger Ballard (1996) and others have argued that, for Punjabis, zat has for the most part been the primary form of identity, despite the strong emphasis on identifying groups on the basis of religion during the colonial period. Such a phenomenon of primarily identifying with kinship group is not peculiar to the Punjab and is found in the Bisru region too.

A jat or zat, then, is a birth or kinship group that links particular families and their descent groups into a larger social whole. The term ‘jati’ or ‘caste’ may, however, be applied at different ‘levels’ of these kinship groups, which often have very complex internal structures. So again we need to proceed with caution! In this chapter, we retain the Sanskrit form jati, which is also used in much anthropological literature, as a construct for ‘caste as based on kinship’, to remind us that we need to look at particular local terminology and social relations to understand the specifics.

Jatis, in the anthropological literature, are characterized as sharing certain features. They are, for example, endogamous, that is, members have a very strong preference for marrying someone from the same jati; they are identified as having a traditional or nominal shared occupation, even if particular members are no longer actually engaged in it; and they normally receive cooked food and water only from those who are of higher or similar (ritual) status to themselves. Relative ritual purity relates to body/ touch (Sharma 1999: 36). Relatively high ritual purity is associated with vegetarian diet and abstention from alcohol and ‘clean’ occupations including shopkeeping. Low ritual purity is linked with meat eating and alcohol consumption and ‘unclean’ occupations, the lowest involving dead animals and human waste.

Let us see how life in Bisru and around relates to such a schema. We will treat marriage last and with it the issue of the different levels at which ‘caste as jati’ can be seen to function. In terms of occupation, then, Bisru (Hindu) jewellers retain their traditional occupation (like, for example, the many jewellers of the Gujarati Soni goldsmith caste who have businesses on the ‘Golden Mile’ in Leicester, UK); but Bisru Chamars, tanners, have turned their back on dealing with dead animals and tanning them. They have raised their caste status by altering their occupation and becoming vegetarian. Functioning as cobblers, their caste is still Chamar, although they are now able to enter Meo houses, unlike their fellow untouchables, the sweepers.

In terms of food, accepting cooked food and water still marks Bisru social hierarchies. Yet although Bisru brahmins condemn Meos for their recent consumption of buffalo meat and will generally not accept cooked food from them, they continue to respect their high status as the dominant caste and some will take tea with them. Yet this is to risk being labelled ‘not a proper brahmin’, even by Meos! Bisru Muslim Nais can act as cooks at public ritual occasions for Meos, because in this region they are seen as sharing descent with Meo clans and hence social status. Elsewhere, Nais, who are barbers, and may be Hindu or Muslim, or neither, have very low-caste polluting status, because they deal with human waste products – hair and nails. This reminds us forcibly that we need to look at localized situations to see how such social relations work. It warns us not to read what is indeed an important local preoccupation, purity, as the only criterion affecting status, nor to read caste relations in terms of a single overarching Hindu system.

Let us now turn to marriage and the different levels of ‘caste as jati’. We focus first on the Meos. The Meos form a caste at the broadest anthropological level (they are endogamous), and in self-identification as Meos. Within that, they have a complex system of twelve clans or pals (some of which have links with specific territorial units) and fifty-two gots (agnatic kin units, that is, those who share common male descent groups). The territory-linked pals are further divided up into sub-clans or thamba, linked with a village purportedly founded by the thamba’s common ancestor. The term thamba also designates that founding village and its surrounding villages as a political area, within which may live Meos from other descent groups as well as other caste groups, as Bisru shows. Meo marry outside their got or clan and outside their village. They marry within the Meo ‘caste’.5 By contrast, the term ‘Baniya’ (a general term for merchants and shopkeepers, including those who live in Bisru) covers an even broader ‘caste’ group, not strictly a jati in the anthropological sense. For although Baniyas in this area intermarry, they do not form intermarrying groups with, say, Baniyas in Gujarat, a state to the west. Within a particular jati, sections may break away and marry only within their own particular section, effectively splitting the endogamous unit in two or more. Pocock (1972) demonstrates this for Patidars in Gujarat. This was linked with other strategies to improve the status of the section that broke away.

This returns us to the question of the interrelations between casta, varna, jati and other aspects of social groupings that contribute to the notion of ‘caste’. The varna ideal is used as a kind of measure against which particular jatis can negotiate their relative status compared with other local groups. We have already seen the Chamars’ change of diet and lifestyle. The Meos’ own location of themselves as Rajputs with ancestry going back to the Mahabharata Pandava heroes shows a similar strategy, aligning themselves with the kshatriyas of the past as many other Rajput and other groups have done. Working in the other direction, ‘brahmin’ as varna rarely unites brahmins of different brahmin castes who are not endogamous and have very marked differences in status. Some of these are linked with occupation, the so-called mahabrahmin funeral priests being an extreme example through their association with dead bodies. Those who act as purohits, or priests, are also generally thought to have lower status than those who do not, an important point as brahmins are often perceived primarily as ‘the priestly caste’.

Finally, it might be thought that these finer points of caste would break down in urban situations, where people’s intimate backgrounds in terms of region, village and local caste status are less easily open to constant scrutiny. Yet the evidence is to the contrary for many reasons. These include the fact that links between kinship groups and hence between people in different locations remain important, especially in terms of support, whether financial from city back to village, living accommodation and introductions for kin moving to a larger conglomeration, visits back home on ritual occasions or when the dream of employment elsewhere terminates in a slum. In addition, marriage within one’s caste remains an important choice for many, not least because, for example, a caste negotiating higher status provides economic and emotional security of many kinds (Gooptu 2001).

So where does this exploration leave us? We have shown the complexity of the phenomenon often simply referred to as caste. We have seen that it has operated in terms of administrative systems and the demands of those seeking political power, in terms of ideologies and the desires of those wishing to shape society in particular ways, and in localized situations where groups have moved in and out of social relations with one another in terms marked by factors including, but not limited to, ritual and economic power. We have also started to challenge the idea that caste is only ‘properly’ a Hindu phenomenon. The following examples illustrate how caste cuts across religion in South Asia and has also been challenged by pre-modern Hindu voices.

Twisting the Kaleidoscope on Caste

The Rejection of Jati? A Poem from the Twelfth Century

God, O God, mark my prayer:

I shall call all devotees of Śiva equal,

from the Brāhmaṇa at one end

to the lowest-born man at the other end;

I shall call all unbelievers equal,

from the Brāhmaṇa at one end

to the untouchable at the other end;

this is what my heart believes!

In saying this – should I have any doubt,

be it so small as a sesamum bud,

O Lord of the Meeting Rivers,

chop off my nose so that the teeth stick out!

(Basava, ‘God, O God’, see Schouten 1991: 26)

This poem is by the twelfth-century Shaiva poet, Basava. According to the fifteenth-century poem-biography of his life, he became the trusted minister of King Bijjala in Kalyana (modern Karnataka, south India), a person of political power. Probably born a brahmin, he rejected his background to worship Lord Shiva, the Lord of the Meeting Rivers, in whose name he signs his poems. We saw in Chapter 3 how Basava’s followers, male and female, wore a small stone lingam around their necks, this community of ‘jangamas’ known for its egalitarian attitude to caste, class and gender, at least within its own ranks (Ramanujan 1973: 62–3). Yet Basava’s poems also show that low and indeed high brahmin caste was for him part of society. Only Shiva’s touch reversed this within the community, not necessarily outside it. It appears though that Brahmins and tanners, washermen and women, did all belong. However, by the fifteenth century the Virashaivas, or Lingayatas, although really consisting of a medley of castes, started to function as a caste group, striving for caste status, rejecting lower caste Lingayat groups. Nonetheless, at the end of the nineteenth century, Lingayatas became heavily involved in educational projects, not least to challenge brahmin monopoly in British government service, while their women do have higher ritual status, education and fewer purity restrictions than in other communities (Mullatti 1989).

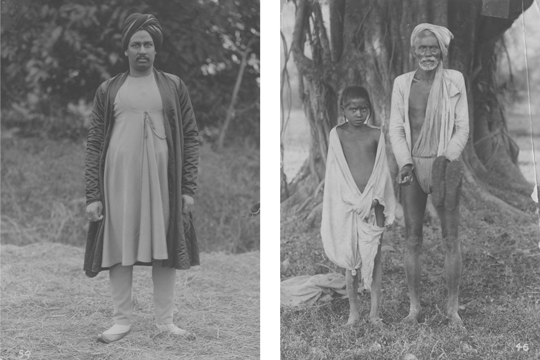

A Christian Fishing Caste

In the village of Kodimunai in southern Kerala (Figures 7A.3 and 7A.4), the majority of the people belong to the Mukkuvar fishing caste. Latin Catholics probably converted in the sixteenth century by Portuguese Jesuits, the Mukkuvar intermarry with Tamil Mukkuvars, and function like any other caste group in that respect. They have a matrilineal system, which means that the husband comes to live with the wife’s family, at least for the first few years of marriage. High-caste Hindu Nayar groups in Kerala are also matrilineal. The Mukkuvar are an untouchable group, however.6 The women tend to sort and sell the fish that the men catch and are vital to the local and caste economy (Figure 7A.5).

Figure 7A.3 The church at Kodimunai. Reproduced courtesy of the photographer, Loyola Ignatius.

Figure 7A.4 Kattumarram used for fishing. Reproduced courtesy of the photographer, Loyola Ignatius.

Figure 7A.5 Fisherwomen on beach, Marina, Chennai. Reproduced courtesy of Jacqueline Suthren Hirst.

Another Systematization: A Nineteenth-Century Law Code

From 1854 to 1963 the categories in the 1854 Muluki Ain (see Box 7A.2) were used in both civil and criminal law in the Kingdom of Nepal and affected people’s personal and political rights. The most powerful and highest ranked category (cord-wearers), for example, were subject to lighter penalties for the same crime than other groups. In 1963 this Code was repealed. The revised Muluki Ain rejected the category of untouchability and recognized all Nepalis as citizens with equal rights under the law.7 It thus changed the principle of a Nepali having ‘ascribed status’ in terms of birth and legal category to one of having ‘achieved status’ via education and ‘national integration’ (Guneratne 2002: 78). Nonetheless, caste continues to be important in negotiating relations with the state, as we shall see below.

Box 7A.2 The Five Hierarchically-Ranked Categories of the Muluki Ain, the Legal Code of 1854, Nepal (Gunaratne 2003: 98)

Cord-wearing (twice-born)

Brahmins, Thakuri, Chetri, comparable Newar groups

Non-Enslaveable Alcohol Drinkers

‘tribal’ groups, e.g. Magar, Gurung, Rai, Limbu, from which army largely drawn

Enslaveable Alcohol Drinkers

‘tribal’ groups, e.g. Tharu, Tamang, Bhote (of Tibetan origin)

Impure Touchables

Newar service castes; includes Muslims and Europeans

..........................................................................................................

Untouchables

including blacksmiths, tanners, musicians, Newar sweepers

If you look at Box 7A.2 carefully, you will see how a single set of categories, specific to Nepal, and politically constructed (see below), incorporates aspects of what we might identify as casta, jati and varna. It also brings groups such as ‘tribals’ or ‘Europeans’ within the same system. Its casta aspect is shown in the very way a total hierarchized system was imposed on Nepali society (through its locally devised principles of high and low status with alcohol drinkers in between). Varna is explicitly recognized in the top category: the ‘cord-wearing’ groups are the top three varnas entitled to wear the sacred thread of the twice-born. Different endogamous service jatis are incorporated into the lowest two categories. Perhaps most importantly we can see how this clear legal framework sought to impose uniformity on people whose actual forms of social grouping were fluid and varied enormously. It can therefore make us alert to other processes of totalizing and negotiation that have happened at local, regional, state and national levels for centuries in South Asia as elsewhere.

The Gender Twist: Caste, Religion and Women as Gateways

Broader issues of gender, religion and kinship are also entangled with those of ‘caste’. Here are three brief Meo examples.

As in many other castes, Meo women act as a kind of gateway protecting the honour of the patriline into which they marry. A key ritual in which they maintain its continuity is kuan puja, worship at the well, performed at life-cycle rituals such as birth, circumcision and marriage (Jamous 2003: 29). The worship is given to the Bheru, the god found in stone form beside the well; both well and Bheru are linked with the woman’s marital lineage. The well-being of the patriline is the worship’s clear focus.

By contrast with their ritual importance, Meo women found themselves expendable to larger political, caste and religious ends during the early twentieth century and partition. From the 1920s, Meos were proselytized by the Tablighi Jama’at, an Islamic movement growing out of the Deoband school (see Chapter 8). The Meos’ minimal Islamic practices – some mosque attendance, circumcision, burial and the use of Muslim names – were deemed insufficient. Men and women alike were urged to adopt ‘proper’ Islamic norms. Women in particular were urged to give up Hindu practices such as kuan puja and singing songs.

Targetted by the Arya Samaj and Sanatan Dharma movements in response, many Meo women were subjected to enforced shuddhi, the Arya Samaj’s purification ritual designed to reincorporate men and women into the Hindu fold (see also Chapter 7B on this ritual). In the abduction of women, which was a widespread phenomenon of partition (as in conflicts across the globe), Meo women were taken into Jat and Gujjar families following shuddhi, often in fear of their lives. Meo men were evicted to Pakistan (where they were not welcome either), their extensive lands the target of their caste competitors. As one participant told the anthropologist Shail Mayaram (1997: 191): ‘This was a time of communal frenzy and passion when people forgot humanism (insaniyat). We took away women. That was the system. Women do not have any religion (dharam).’

Nonetheless, when Jamous did his research in the 1980s, Meo women were still ‘resisting regimes’:8 performing kuan puja and singing songs including a satire blaming the Jama’at for all their household and village troubles; and cooking water buffalo despite brahmin rebuffs.

The Politics Twist: Caste Status and the State

There are all sorts of ways in which politics and caste are intertwined, not least the many ways in which political impulsions mould and shape what is seen as ‘caste’ and how it functions in different social and historical contexts. In her discussion of the Meos up to partition, Mayaram (1997) shows very clearly the political influence on caste formations of the Princely States of Alwar and Bharatpur, in whose territories many Meos lived.

Here, we focus on a different example of the interrelation of politics and caste. The Muluki Ain (Chief Law), as we saw above, was brought into force in Nepal in 1854. Jang Bahadur Rana, the Prime Minister, aimed to create a legal system integrating the smaller independent kingdoms forcibly brought under the kingdom of Gorkha in the late eighteenth century. He also wanted to mark the emerging nation of Nepal off from India under the British. In formulating the Code, he drew on aspects of British law as well as Newar (Buddhist) and other local customs (Guneratne 2003). If we look at its ranking, it is apparently based on the purity of the different groups’ presumed lifestyle. Alcohol drinkers (matwari) were incorporated between high-caste Hindus and untouchables. Yet the two categories of matwari clearly show the interest of the state: a higher ranking was given to those useful in military terms to its preservation. They were also those the British identified as ‘martial races’ (including the Gorkhas). The lower, including the Tharus, marginal forest-dwellers, were seen as insignificant to the state. The Oudh Gazeteer said Rana Tharus ‘will on no account take service as soldiers’, being ‘a cowardly race’ (Government of Oudh 1877: 208–9, cited in Guneratne 1998: 755). The state could also change a person’s (caste) categorization. A brahmin who infringed the law could be made to drink alcohol or eat pork, forcing him into the ‘Non-Enslaveable Alcohol Drinkers’ category. His children would then be classified as such. Because a person’s personal and public rights were linked to his jat as defined in the Code, this identity became key to participation in the state and to negotiations to improve jat status. Thus, political processes homogenized a series of differently conceived identities into a set of categories that shaped political and personal identities in turn. In the twentieth century also, culturally widespread endogamous Tharu jats came to conceive of themselves as a single jat, as a result of the changing economic and political policies of the Nepali state (Guneratne 1998).

The Religion Twist: Alternatives to ‘Proper’ Religion

The map of Bisru shows several mosques, each of which tends to function as a neighbourhood and therefore caste-related mosque, much as many Hindu temples do. You probably identified the village as Muslim originally, but may now be a little more puzzled about the Meos’ religious identity. As we saw above, the Meos have been targeted by both Hindu and Muslim reforming groups, resulting in their political marginalization around partition, although with subsequent revival as the dominant caste in some Mewati villages since. We have seen how their practices span ones very similar to Hindu practices and others that are clearly Muslim. Mayaram (n.d.) therefore asks the question: In what ways is it possible to be simultaneously Hindu and Muslim in South Asia? (or Hindu and Christian, Muslim and Sikh). She draws not only from her work on the Meos of India and Pakistan, ‘today one of the largest Muslim communities of the sub-continent’ (p. 4), but also on the Merat, a complexly differentiated group. Together, Rawat, Chita and Merat jatis make up the Merat jati at the wider level. Each separate jati also has Hindu, Muslim and Christian sections. They intermarry within their jati and share a cosmology incorporating gods, goddesses, pirs and ancestors. Both Hindu Rawats and Muslim Merats have been criticized for not manifesting ‘proper’ religious identity. Yet Mayaram argues that such ‘liminal’ groups should be more properly seen as having identities relating to at least one religious tradition. She acknowledges that they have to withstand huge pressures by those who want to ‘singularize, reform and domesticate’ them, because they are seen as contestatory and ‘dangerous from the perspective of state and religious authority’ (p. 8). Yet she finds in their creative theologies and very existence a source of alternative ways of living together. In this, the Meo and Merat pose a strong question to a normative, over-arching model of World Religions, which in Part I of this book we have been seeking to contextualize.

Concluding Thoughts: Diversity, Religion and Religious Traditions

In Chapter 1, we asked you to bear with our definitions of ‘religion’ and ‘religious traditions’, to enter the worlds of our approach as you would if you were watching a play. We hope that you have not sat through Act I as a mere spectator, but have been drawn into it, through the lives and practices of those we have glimpsed, people affected by the ways others represent them, people negotiating and affecting the ways they are represented, agents shaped by their particular contexts, as we all are, yet shaping them in turn. We hope that you have glimpsed just a little of the enormous diversity of South Asian religious traditions, ‘the panoply of ideas, practices and objects that today are commonly recognized as belonging to a religion’, as we said in Chapter 1. Finally, we hope that you will now see why it is so important to look at these ideas, practices and objects in different networks of contexts and through different twists of the kaleidoscope. The World Religions model is an important one. We have seen how some features of it emerge in South Asia in the modern period in relation to ideas of divinity, sacred texts, myth and so on. In Part II we will see how particular views of Hinduism, Buddhism, Indian Islam and Sikhism come to be formed. However, much of the ‘available data’ we have looked at in Part I do not easily fit with such a model. That is why we have looked for alternative ways of ‘cutting across’ the data, to recall Will Sweetman’s (2003a: 50) phrase. Our final discussion point for Part I invites you to think back over the material you have encountered so far to consider some of those alternatives.

Discussion Point to End Part I

In this context [the Meos’ attitude to ‘the act of faith’], Islam is merely one dimension of local social and religious life.

(Jamous 2003: 31)

From the point of view of a World Religions model, Jamous’ statement about the Meos and Islam might seem highly problematic. In this chapter, however, we have seen various perspectives from which we could understand it. Thinking back over the whole of Part I now, what alternative models for looking at the intersections between different aspects of religion and social life have you come across? How, if at all, might they provide a helpful corrective to the World Religions model? What can a stress on diversity and the need to understand specific contexts bring to our understanding of religion in modern South Asia? You may want to bear these questions in mind as you turn to Part II. We shall return to them in Chapter 12.

Further Reading

Dirks, N. (2001) Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

A challenging text that presents a view of caste as a colonial construct.

Mayaram, Shail (1997) Resisting Regimes: Myth, Memory and the Shaping of a Muslim Identity, Delhi, Oxford University Press.

A careful historical study of the Meos through changing modern periods examining the political, religious and other influences in relation to which they have resisted others’ regimes.

Ram, Kalpana (1991) Mukkuvar Women: Gender, Hegemony and Capitalist Transformation in a South Indian Fishing Village, London: Zed Books.

A nuanced ethnographic study helping to deconstruct essentialisms of caste, religion and gender.

Sharma, U. (1999) Caste, Buckingham: Open University Press.

A useful, nuanced introductory text rooted in anthropological method.

Thapar, Romila (2002) Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300, Berkeley: University of California Press.

The comprehensively revised work of a major Indian historian, dealing with issues of caste throughout and particularly in Chapter 2.

* An explanation of the rationale for calling these two chapters 7A and 7B respectively is provided at the beginning of Chapter 7B.