With utility costs rising and global warming taking its toll, we have more reason than ever to reassess how we use resources. The Alliance to Save Energy estimates that the average U.S. household sends twice as much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as the average car, so it's important for everyone to cut back their energy use. (Technically, power plants are the ones who spew the CO2, but they do it while producing power for us.) As you learned in the last chapter, you can start fighting pollution right in your own home. Same goes for water and electricity: You can do your part to conserve both by making simple changes around the house.

The first step toward conserving electricity—and lowering your utility bills—is to examine how you use energy. This chapter shows you how to give your home a checkup to find out. After that, you'll learn all kinds of ways to increase your home's efficiency, including a whole section about heating and cooling systems, which (in an average home) eat up more than half of the energy you pay for each year. Then you'll get info about how much power your appliances use and, if you're shopping for new ones, how to find the most efficient models. You'll learn other great tips for cutting your electricity bill, saving water, and lighting your home, too. Making even a few of the changes suggested in this chapter will put you well on your way to using less energy and helping the planet.

Most people use more energy at home than anywhere else. That's probably no big surprise: Your utility bills likely tell you as much each month. If you want those bills to tell a different story—like "Wow, look how much money you're saving!"—start by checking your home's energy efficiency. With an efficient home, you'll use less energy—and spend less money—to heat and cool it, light up rooms, and power appliances and gadgets. Being energy efficient is good for the earth, and good for your wallet.

Making your home more efficient is good for your wallet and the planet. The U.S EPA estimates that 17 percent of total greenhouse-gas emissions in the United States come from home energy use, which works out to four metric tons of carbon dioxide sent into the atmosphere every year for each person in America. (A metric ton is 2,200 pounds, about the weight of a small car.) That's one giant-sized carbon footprint!

Note

A greenhouse gas is any gas that contributes to the greenhouse effect, which traps heat inside the earth's atmosphere, absorbing infrared radiation. These gases include water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, halogenated fluorocarbons, ozone, perfluorinated carbons, and hydrofluorocarbons.

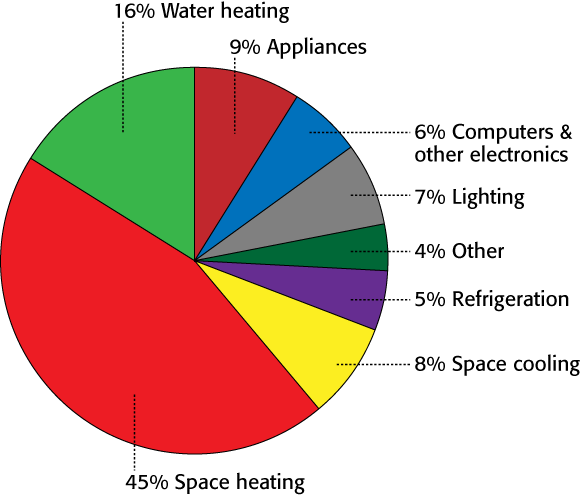

How do you use all that energy? Figure 2-1 shows a typical home's energy use. (This info comes from the U.S. Department of Energy's 2008 Buildings Energy Data Book; some numbers are rounded up.) As you can see, more than half the cost goes to heating and cooling. Water heaters and appliances are also big energy hogs.

Note

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, in 2007 U.S. households used an average of 936 kilowatt hours per month and had an average monthly electricity bill of about $100.

Before you can use all the tips and tricks for making your house more energy smart that you'll learn later in this chapter, you need to get a sense of where you're starting from—how efficient (or inefficient) the home is right now. To find out, perform an energy audit yourself or hire a professional to do one. The audit will reveal some stuff you can fix yourself, and other issues you'll need help with. But checking your home for common problems is a good start in making your home more efficient—and cozier, too.

You already know which rooms feel drafty or are always hotter or colder than others. Those rooms are good places to start your audit, but you should give your whole house a once-over to figure out how to make it more efficient and reduce your energy costs.

Here are the steps in a do-it-yourself home energy audit:

Look at your bills. Pull out your old utility bills, going back a few years if you have them (if you don't, call the energy company for a summary of your account). Spread the bills out and look for patterns. Is there a particular season or month when they spike? What's different about your energy use then that causes the spike? For example, if you live in the snow belt, you know heating costs are a lot higher in January than in April. So you'll want to focus on improvements that can bring down those winter heating costs, such as beefing up your insulation or getting a high-efficiency furnace.

Tip

The Energy Star program, sponsored jointly by the U.S. EPA and the U.S. Department of Energy, can help you interpret your energy bills. Bills in hand, go to www.energystar.gov. On the home page, click Home Improvement, and then (from the left-hand menu) select Home Energy Yardstick. This opens a calculator where you fill in facts about your home, the type of energy you use for heat (such as fuel oil or natural gas), and info from past utility bills. The yardstick compares how your home's energy use measures up to others across the country and recommends ways to improve efficiency.

Find and fix air leaks. As much as 30% of the money you spend to heat and cool your home could be going right out the window—or through the mail slot or cracks in the wall. Air leaks aren't the same as ventilation because you can control ventilation; air leaks are always open and undermine your attempts to control the temperature. Here are some places you're likely to find leaks:

Window and door frames

Mail slots

Dryer vents

Spots where phone and cable lines enter the house

Around the chimney

Recessed ceiling lights

External water faucets

Electrical outlets and switches on external walls

Corners

Places where your home's foundation meets the walls and where the walls meet the roof

Places where floors and ceilings meet exterior walls

Mortar between stones or bricks (look for cracks)

Fireplace dampers (make sure they're closed when you're not using the fireplace)

Here's how to check for leaks in those places:

Feel for drafts. If it's cold outside, pass your hand along the spot you're checking, such as a window frame. Cold air coming in against your hand means air is leaking there.

Use a stick of incense. Light the incense and hold it next to a place where you suspect a leak. (Watch out for anything that can catch fire, like drapes.) If the incense smoke goes straight up into the air, the spot is airtight. If the smoke streams into or out of the room, bingo—you've found a leak.

Shine a light on leaks. When it's dark out, grab a flashlight and send a friend outside. Turn out the lights in the room you're checking, and then shine the flashlight at potential leak sites. The other person will see light coming through any large holes. (This method doesn't work well for small cracks.)

Check the attic. If you have an attic, make sure it's insulated enough to keep your house warm in the winter and cool in the summer. You can eyeball your insulation to see whether there's enough by looking across the attic: If the insulation between the joists is higher than the joists, you're probably okay; if it's lower than or level with the joists, it'd be good to add more. And make sure there's plenty of insulation on the exterior walls, too—they're notorious for air leaks.

Get your heating system checked. Even the most energy-efficient, top-of-the-line furnace won't save money and energy if it's connected to leaky ductwork. A thorough assessment of your home's climate-control system is best left to the pros, so if you haven't had it inspected in the past year, make an appointment.

Note

A professional heating inspection not only improves efficiency, but also confirms that your system is safe—making sure, for example, no carbon monoxide is getting into your home. Be sure to have one at least once a year.

In addition to getting a professional inspection done, here are some things to keep an eye out for when you check your heating system during your audit:

Dirty filters. Dust on filters restricts air flow and makes the system less efficient. If your furnace or air conditioner's filter looks dirty, it is—swap it for a clean one. You may need to do this as often as once a month during the heating season.

Tip

Break the cycle of throwing out disposable filters and replacing them with new ones by buying a permanent electrostatic filter instead. These filters are highly efficient (they trap about 95% of dust and airborne particles) and last for the life of your heating/cooling system. Just wash them once a month or so. You can find 'em at any home improvement store.

Dusty AC coils. If your air-conditioning unit's coils are dirty, vacuum them clean.

Leaky ducts. One common problem is leaking ducts, which cause some of the warmed or cooled air to not get where it's going. Instead, it ends up in the attic, basement, crawl space, or garage, wasting energy and money (leaks can reduce your system's efficiency by 25–40%). To find leaks, look for disjointed sections, obvious holes, and dirty streaks on ducts.

Get more out of hot water. Water heaters use lots of energy. If yours is due for replacement, get a high-efficiency or tankless one. Otherwise, make sure the tank and the pipes that carry water from it are well insulated (Getting More out of Your Appliances).

Scope out your appliances. As you saw on How Efficient Is Your Home?, large appliances (including refrigerators) eat up nearly 15% of a home's energy budget. Just about any gadget you can plug in has a label that says how much power it uses. Table 2-1 (How Much Energy Does That Gadget Use?) shows how many watts common appliances use. (The box on Calculate power use for free explains how utility companies use wattage to calculate your bills.) Another way to check energy use is with a power meter—Professional energy audit tells you about 'em.

If you're replacing an older appliance that's a power hog, make sure the new model is Energy Star–rated. To learn about how they rate appliances, go to www.energystar.gov and click the Products tab. (You can find a list of all the websites mentioned in this book on the Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com.)

Note

Refrigerators are particularly big energy users. According to Energy Star, if everyone in the U.S. replaced their pre-1993 fridge with a newer, more efficient model, it'd save $1.7 billion in energy. Of course, no one wants of millions of abandoned fridges taking up space in landfills, so Energy Star has launched a refrigerator-recycling campaign. Go to www.energystar.gov/recycle for details.

Shed some lighting costs. Another good-sized chunk of your monthly energy bill pays for lighting. As your old-style incandescent bulbs burn out, replace them with more efficient compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs); Let There Be (Compact Fluorescent) Light has more about them. In the meantime, try using lower-wattage bulbs. Are there places where you could replace a 100-watt bulb with a 75-watt one, or 60 instead of 75? And be sure to turn off lights when you leave a room, just like Mom taught you, or go high-tech with infrared sensors that turn lights on when someone enters the room and off when they leave. Dimmer switches, timers, and solar-powered lights can also reduce your power bill.

If you don't have the time or inclination to do an energy audit, consider hiring a professional to do it for you. They have the know-how, experience, and equipment to find problems you might not catch. For example, they can do a blower door test (which measures how airtight your home is) and take thermographic scans that show where heat is escaping.

To find an energy auditor, try calling your utility company. Many offer free or inexpensive audits. If you'd rather hire an independent auditor instead of using one who works for the utility company, the Energy Star site can help you find one. Go to http://tinyurl.com/ocf24b, select Home Energy Raters and your state, and then click Search to find auditors in your area.

Whichever kind of auditor you go with, the person will conduct a whole-house assessment and compile a list of suggestions for making your home more energy efficient. Common recommendations are things like increasing insulation, replacing old windows, sealing ductwork, and upgrading your appliances. The suggestions can range from quick-and-easy to disruptive-and-expensive. No one wants to spend $20,000 to save fifty bucks a month. If you discover it'll take years for energy savings to recoup the cost of the suggested renovations, consider downsizing (Should You Downsize?) or implementing some of the other energy-saving strategies in this chapter.

Looking over past bills (Evaluating Your Home's Energy Use) is one way to learn about energy use and find trends. Or you can also use a power meter to get up-to-the-minute info about how much energy you're using right now—for a single appliance or your entire home. Once you know that, you can fine-tune your energy consumption and trim those monthly bills. The following sections explain your options.

If you want to know how much it's costing you to run that old air conditioner or new microwave, you can buy a power meter that'll tell you. Plug the meter into an outlet, and then plug the appliance into the meter and turn it on. The meter displays how much power the appliance is using and estimates how much it costs to run. Popular meters include Kill A Watt (www.p3international.com), Watt's Up? (www.wattsupmeters.com), and the EM100 (www.upm-marketing.com). They start at around $100, and can pay for themselves by helping you save money on electricity over the years.

Note

At this writing, the folks at Google are testing PowerMeter, a free service that will work with utility companies' smart meters, those digital doohickeys that collect info about your power use and report it to the utility company. Google PowerMeter will use that same info to display your household's electricity usage online. So if you're away on a business trip, for example, you'll know when to call home and pester the kids to turn off some lights. Your home's info will be secure, private, and presented in almost real time. To learn more about it, visit www.google.org/powermeter.

To keep an eye on how much electricity your household is using, you can buy a whole-house meter (for most models, you'll need an electrician to install it). These gadgets tell you how much power you're using now and how much you've used so far this month, and give you a running total of your costs, based on local rates. So when you see that you're spending more than you planned for the month, you can do things like turn off lights and adjust the temperature by a few degrees.

Whole-house meters start at around $120. Models to try include The Energy Detective (T.E.D.) and The Meter Reader EM-2500. If you're in the U.K., take a look at efergy.com's (yes, that's efergy, not energy) wireless whole-house monitors, which you can install yourself.

You don't need to buy a power meter to learn how much electricity you're using. The box on Calculate power use for free explains a simple formula for calculating how much an appliance is costing you. And once it's released, Google's PowerMeter (see the Note above) will provide a free and easy way to track your household's energy use.

Tip

Some devices' labels don't specify wattage, but they probably list numbers for volts and amps. To figure out wattage, simply multiply the number of volts by the number of amps. Easy, huh?

You can find lots of energy-cost calculators online. You enter info about your household and appliances and they estimate how much it costs you to run certain appliances, keep your house at a certain temperature, and so on. Here are some sites to try:

Consumers Power Online Usage Calculator (www.consumerspower.org/home_energy/billestimator.php) is sponsored by Consumers Power Inc., a private nonprofit cooperative in Oregon. (It bases its estimates on average use for a family of four.)

EnergyGuide (http://energyguide.com/audit/HAintro.asp) offers your choice of a fast-track analysis or a detailed analysis. The results include recommendations for saving energy and money. You can also check specific appliances to see whether it's time to replace them.

Generic Electrical Energy Cost Calculator (www.csgnetwork.com/elecenergycalcs.html) can give you cost estimates for categories like lighting, kitchen appliances, personal care, and so on.

Home Energy Saver (http://hes.lbl.gov)—sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. EPA, and other agencies—can tell you the energy costs of an average home and an energy-efficient home in your area. If you fill out a 19-item questionnaire, the site gives you more details about your power use and how to reduce it.