Q: | How many politicians does it take to change a lightbulb? |

A: | Both houses of Congress and a president to sign the bill into law. |

By 2014, the whole U.S. will be changing its lightbulbs, thanks to a federal law passed in 2007 that phases out traditional incandescent bulbs in favor of compact fluorescent lamps, a.k.a. CFLs. Countries around the world are changing their lightbulbs, too: The European Union and Australia have already banned incandescent bulbs, and Canada, India, and other countries have made plans to replace all or some incandescents with CFLs.

Regular lightbulbs haven't changed a whole lot since Thomas Edison invented them in 1879; they're basically mini-heaters that give off light as a byproduct. They work by passing an electric current through a long, thin filament, which heats up and gives off light. The glass bulb is filled with an inert gas, such as argon, that keeps the filament from oxidizing (combining with oxygen and burning out).

CFLs are a bit different. They have two parts: a glass tube (coated on the inside with phosphor and filled with gas) and a ballast, which provides the lamp's starting voltage and regulates its current. When you turn on a CFL, electricity flows through the ballast into the gas, causing the gas to give off ultraviolet light. This light then excites the tube's phosphorous coating, which gives off visible light. Unlike standard fluorescent lights (the kind found in classrooms, offices, and stores), CFLs are small, come in a variety of shapes, and can fit in your existing light fixtures.

Tip

Fluorescent lights have a reputation for giving off harsh, unflattering light. Some CFLs have diffusers to soften their light, making them less like the overhead lights at your office and more like the softer, warmer light of the bulbs at home. To get softer light, look for the color temperature rating on the package: bulbs with the "warmest" light (which is easier on the eyes) have ratings of less than 3,000 kelvins; bulbs with ratings above 5,000 kelvins give off much harsher light.

CFLs have several advantages over incandescent bulbs:

They're cooler, producing about 90% less heat, so you're far less likely to burn yourself on a CFL.

They use about a quarter of the energy to produce the same amount of light.

They last about 10 times longer, so each CFL means 10 bulbs you don't have to replace.

As you've probably guessed from this list, CFLs save a lot of energy. Over its long lifetime, a single CFL will cost you $30 to $45 less in electricity than a succession of incandescent bulbs. And because CFLs use less energy, they reduce the amount of greenhouse gases spewed by power plants. Lighting accounts for 19% of the total electricity use in the U.S., and that means the benefits of CFLs add up fast: If Americans replaced all their incandescent bulbs with CFLs, it would prevent 158 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions over the next year—that's equivalent to taking about 30 million cars off the road.

Note

In the summer, incandescent and halogen bulbs can increase the cost of cooling your home. These bulbs give off most of their energy as heat—making your air conditioner work that much harder.

When you see the potential for reduced greenhouse gas emissions and sheer cost savings, it's no surprise that governments are eager to replace Thomas Edison's old invention with new-and-improved CFLs. What does that mean to you, the consumer? CFLs cost more than incandescent bulbs, but the long life and lower energy costs more than make up the difference. And you don't need to wait for incandescent bulbs to get outlawed before you make the switch—as your old lightbulbs burn out, replace 'em with CFLs.

Shopping for CFLs is a little different from buying regular lightbulbs. You're probably used to buying bulbs based on watts: a 100-watt bulb for bright light, a 40-watt bulb for softer light, and so on. But as the box on Calculate power use for free explains, watts measure power, not brightness. Because CFLs use less power, their wattage is much lower than what you're used to. So you can't replace a 40-watt incandescent bulb with a 40-watt CFL and get the same light—the CFL will be much brighter. Fortunately, most CFL packages tell you their incandescent-bulb equivalents.

When you want to know how much light a CFL will produce, think in terms of lumens, which measure light. Table 2-2 compares the number of watts used by incandescent bulbs and CFLs to produce the same number of lumens. For example, a 60-watt incandescent bulb and a 13- to 18-watt CFL both produce about 890 lumens.

Tip

When shopping for CFLs, look for the Energy Star label, which means that the bulbs meet or exceed performance requirements for heat production and energy use. CFLs without such a label may have a shorter lifespan, for example.

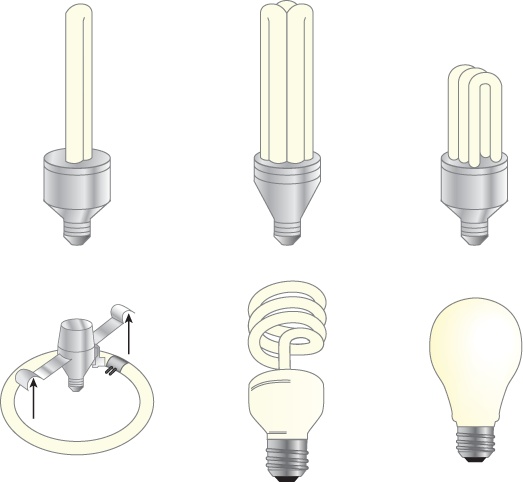

You can buy CFLs in a variety of styles and shapes, from twisty tubes to round ones that resemble incandescent bulb. Some CFLs have multiple tubes (two, four, or six); others have spiral or circular tubes. The number and size of the tubes determine how bright the bulb is—more surface area means more light.

You can thread these bulbs in to any standard light fixture, but some CFLs don't work with dimmer switches or three-way fixtures, so if you're looking for a bulb that works at different brightness levels, check the package (dimmable CFLs can be a lot pricier). Also, most CFLs are designed for indoor use at warm temperatures, and they won't last as long if you use them outside. If you're looking for a CFL that you can use outdoors—especially if you live in a cold climate—check the temperature range listed on the box. Putting an outdoor-use CFL in an enclosed light fixture, like a lantern-style lamp, helps to protect the bulb from the elements—rain, snow, cold air, and so on.

Now that you know how watts relate to lumens (Table 2-2) and what color temperature is (Let There Be (Compact Fluorescent) Light), here are a few more tips to help you make the switch to CFLs:

Unlike incandescent bulbs, CFLs take time to reach their full brightness—up to three minutes. This is normal—there's nothing wrong with the bulb—but it does take some getting used to.

Turning a CFL on for only a short period shortens the bulb's life. To get the best performance, leave CFLs on for at least 15 minutes at a time. That means CFLs work best in rooms where you leave them on for a while, like a kitchen or family room. They're less suitable for closets or pantries, where you're likely to turn them on and off more frequently and for shorter periods; in these spots, consider LEDs instead (see the box on Disposing of CFLs).

CFLs don't work as spotlights—try LEDs (Disposing of CFLs) when you need a narrow, focused beam of light—but they're great for area lighting, such as table lamps.

As you may have heard, CFLs contain mercury, a toxic metal that, at high doses, can make people sick and cause kidney, lung, and brain damage. An important part of green living is clearing toxins out of your home (see Chapter 1)—so you may be wondering if it's safe to replace your lightbulbs with CFLs.

There's no question that mercury is dangerous, especially for fetuses, infants, and children. And you probably already know to avoid or limit seafood that may contain mercury, like swordfish and tuna. So what kind of risk do CFLs pose? CFLs contain a small amount of mercury: about 4 or 5 mg, which is significantly less than in a typical watch battery, dental filling, or pre-1970 light switch. As long as a CFL's glass stays intact, there's no chance of the mercury leaking into your home. If the glass breaks a small amount of mercury vapor and powder containing mercury get released, and even a small amount can be hazardous. The next section tells you how to deal with that situation. Knowing how to dispose of CFLs safely—whether they're broken or no longer work—will keep mercury from contaminating your home and the local landfill.

Note

CFL companies including Philips ALTO, Feit EcoBulb Plus, Neolite, and Earthmate are starting to make low-mercury bulbs.

Of course, the best way to protect yourself from the potential hazards of a broken CFL is to not break them in the first place. But accidents happen, and when they do these steps will help keep you and your family safe:

Ventilate the room. Get everyone—including pets—out of the room where the CFL broke (make sure no one walks through the broken glass). Open a window and leave the room, closing the door behind you.

Let the room air out for at least 15 minutes.

While you wait, find and put on some protective gear: safety goggles, gloves, and a surgical mask. This may be overkill, but you don't want to accidentally inhale or ingest even a little mercury.

Clean up the glass fragments and any powder by scooping them up with two pieces of cardboard: one to push the CFL fragments and the other to collect them. Don't use a broom, brush, or vacuum cleaner—those will just stir up the powder, plus you want to get the mercury out of your house completely, not leave some stuck to a broom or sitting inside the vacuum. Put the fragments and cardboard into a glass jar or plastic bag. If you use a plastic bag, double-bag the debris and make sure both bags are sealed.

Use the sticky side of some wide tape, like masking tape or duct tape, to clean up any remaining pieces of glass and powder. Put the tape into the glass jar or plastic bag.

Wipe the area with a damp cloth or paper towel, and then put that in the jar or bag, too.

Seal the jar or bag tightly and put it in an outdoor trash can for collection.

Wash your hands thoroughly.

If the CFL broke on a carpet, you'll probably want to vacuum the carpet after you've taken these clean-up steps. If you do, first make sure that you pick up all visible glass and residue. And afterward, remove the vacuum-cleaner bag and place it in a plastic bag. For bagless vacuums, empty the dust compartment into a plastic bag. In either case, seal the plastic bag and put it inside another plastic bag and seal that one, too. Then throw away the plastic bags and wash your hands again.

If a single broken CFL requires careful clean-up, what about the millions of CFLs that will eventually burn out? Will the mercury they contain hurt the environment?

Widespread CFL use will actually reduce the amount of mercury released into the environment. That's because CFLs use so much less energy than incandescent bulbs, and the biggest source of mercury pollution is burning coal. Over a five-year period, a coal-fired electric plant releases 10 mg of mercury for each incandescent bulb it powers. Because a CFL uses only about a quarter as much power, that same plant produces only about 2.5 mg of mercury to power a CFL over the same period. Even when you add to that the 4–5 mg of mercury in a typical CFL, that's still a 25% reduction in mercury released into the environment.

To minimize the environmental impact of mercury from CFLs even more, recycle used CFLs: The bulbs get separated into materials that can be used again, such as glass, aluminum, and mercury. The mercury is then sold to lighting companies to use in new fluorescent lamps and CFLs.

Home Depot and IKEA both have nationwide CFL recycling programs; you can drop off unbroken CFLs at any of their stores. If you don't live near one of those, go to http://earth911.com and find a recycling center in your area. The site lists both local results and mail-in programs.