The LEED system gives you a sense of how to make your newly built or remodeled home healthy, easy on the earth, and efficient. This section explains some of the key pieces of the green building puzzle in more detail so you can design and build your earth-friendly home or redo your current place to make it greener.

Tip

When designing a house, think small. Smaller homes cost less to heat and cool, and cozy, multi-use rooms may be preferable to large, rarely used ones. (Should You Downsize? lists other advantages of downsizing.) Work with your architect to see where you can scale back.

To help plan your new home, scan the home energy audit checklist on Evaluating Your Home's Energy Use. Whether you're building from the ground up or renovating, that list can help you focus on ways to conserve energy and improve efficiency. And be sure to discuss these issues with your contractor:

Efficient ventilation, lighting, and appliances. Insist on Energy Star–rated products whenever possible. And go for the most efficient equipment you can afford to save energy dollars down the road.

Insulation. To keep your home snug, use a nontoxic insulation made from stuff like soybeans or cotton (see Insulation). The kind you choose should have a high R-factor, which measures how well it keeps heat from getting transferred from inside your house to outdoors or vice versa.

Windows and doors. Energy Star rates windows, skylights, and exterior doors. Efficient windows and skylights have multiple panes with a gas (such as argon) between them and a spacer to hold the panes in place, as well as special coatings to reflect infrared and ultraviolet light. Doors may have a foam core or some other type of insulation. Windows and external doors should seal tightly to keep air from leaking around them.

Renewable energy. Consider going off the grid—at least partially—and getting your home's power from the sun, wind, or ground. The next section tells you how.

As you learned in the last section, the best first step in greening your building project is focusing on efficiency, which helps you reduce costs and your household's toll on the planet. And an energy-efficient home puts you in a good position if you decide to take things to the next level by getting some or all of your power from renewable sources. You might even get a grant or rebate to help pay for it (see Grants, Rebates, and Tax Credits).

With renewable energy, there's no one-size-fits-all answer. Consider factors like your home's location and climate, the impact of a particular technology on the environment and neighborhood (you don't want neighbors picketing your home and filing lawsuits, now do you?), and your budget. Discuss these issues with your architect or contractor to figure out the best choices for your home. The following sections discuss some options.

Note

Chapter 10 looks at alternative and renewable energy technologies in detail. This section focuses on applying some of those technologies to homes.

Solar energy has been around for as long as the Earth has circled the sun—and it's free. Take advantage of the sun's light and warmth by drawing back the curtains and opening the blinds. Letting the sunshine in to spread its warmth is called passive solar energy. When you're building a new home, consider these ways of making the most of such energy:

Choose your site carefully. If you live in a cold climate, try to situate the house so it gets maximum exposure to the south or southwest (assuming you're in the northern hemisphere, that is). If you live in a hot climate, minimize southern and southwestern exposure instead.

Include a sunroom. In cold areas, a sunroom or solar greenhouse on the southern side of your home can trap heat and warm the inside air. From there, a convection system can distribute the warm air throughout the house. If you want to use this room in the summer, install shades and close them to keep it from getting too hot.

Take advantage of windows. To warm your house with sunlight, put large windows and glass doors along south- and southwest-facing walls (and smaller windows along the north-facing wall). Install thermal drapes (which you can buy just about anywhere) and open them during the day and close them at night. In hot climates, make the south-facing windows smaller and cover them during the day, and avoid putting skylights on south- and west-facing roofs.

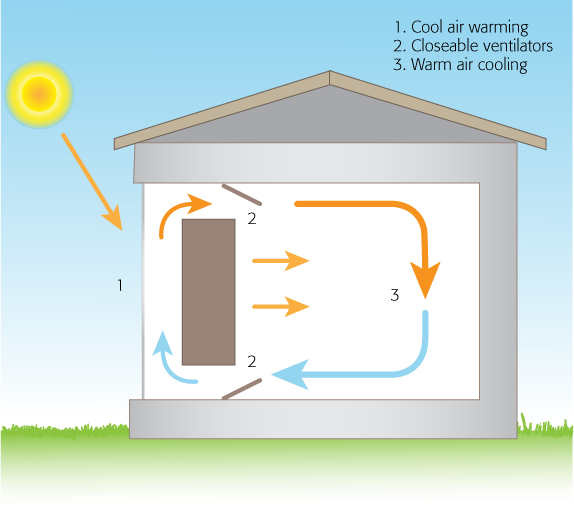

Ventilate. Throw open those windows to take advantage of breezes that circulate air throughout your home. Place windows in spots that maximize cross-ventilation.

Invest in awnings. If windows make south-facing rooms too hot, install retractable awnings to shade them during the hottest part of the day and let light in when the sun isn't shining directly into them. If you don't like the look of awnings, design roof overhangs that protect windows from the summer sun and let in winter sun.

Pick the right materials. Choose building materials that have a high thermal mass, or capacity to store heat, like brick, stone, concrete, and ceramic tile. In rooms where the sun shines directly on the floor, ceramic tiles will store and gradually release the heat they absorb.

Consider a Trombe wall. This kind of exterior wall, built from a heat-absorbing material—like stone, concrete, masonry, or adobe—faces south so it absorbs heat during the day, and then radiates it into your home. One-way vents help circulate air during the day and lessen the amount of heat that escapes at night. An overhanging roof shields the Trombe wall from the hot summer sun but lets the winter sun shine directly on it.

Create a buffer zone. Opening and closing exterior doors lets inside air escape and brings outside air in, making your heating and cooling system work harder. So design entryways to minimize this problem. For back doors, putting a mudroom or utility room between the door and the rest of the house helps keep the main living area comfortable. For front doors, consider adding an anteroom or vestibule between the outside door and the door that leads into the house.

Choose the best ceiling height. Heat rises, so lower ceilings keep cold-climate homes cozy, while higher ceilings make rooms more comfortable in hot climates.

Tip

Use ceiling fans (Heating and Cooling Efficiently) to circulate air and spread warm or cool air evenly throughout a room.

Landscape smart. Plant deciduous trees (the kind that lose their leaves in the fall) to shade windows and doorways in summer and let the light through in winter.

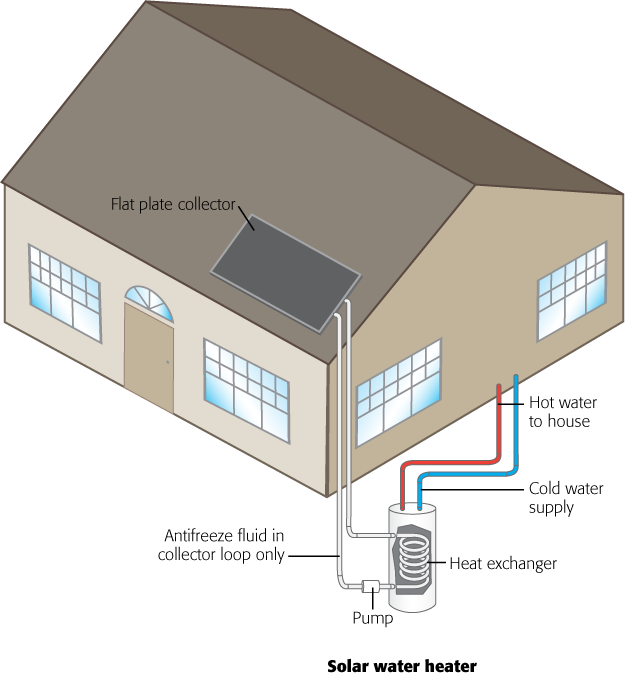

Another option is to install solar thermal panels on the roof or in the yard and connect these to your heating system. The panels collect sunlight and convert it to heat, which is transferred via one of these:

A liquid-based system pipes in heated water or an antifreeze mixture and stores the heat in a tank for warming water and for distributing it throughout the home.

An air-based system uses air to circulate heat through your home.

The results you get with a solar-based system depend on factors including the number and size of the panels, the climate, how much sun your site gets, and so on. In hot, sunny climates, solar energy may meet all your heating and hot-water needs. In cooler climates that have lots of cloudy, snowy, or rainy days, this kind of system may work best as a supplement to a traditional heating system.

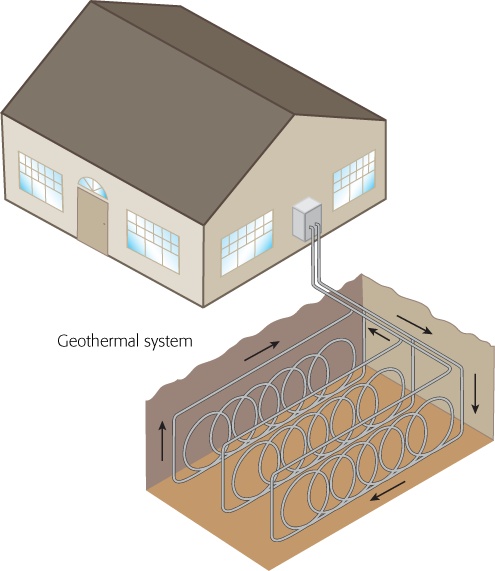

The earth is made of thermal material, storing nearly half of the solar energy that reaches it. So why not tap into this geothermal energy to heat and cool your home?

Throughout the year, the earth stays at a relatively constant temperature just a few feet below the surface, no matter how hot or cold it feels above ground. Geothermal systems—also called geo-exchange, earth-loop, or ground-source heat pumps—use buried pipes to move heat from the ground into your home during the winter (or vice versa during the summer). Here's how they work:

When the ground is warmer than the air, liquid circulates through pipes buried in your yard, absorbing heat. The liquid travels through a geothermal unit, which extracts heat from it and circulates that heat through the house. The cooled liquid then makes another trip through the buried pipes to bring in more heat.

In the summer, the system's geothermal unit removes heat from your home's air by warming the liquid that circulates through the pipes and returning cooler liquid to the house. As this liquid travels through the buried pipes, the cooler earth pulls out the heat, and the liquid is ready for another go-round.

If you live on top of a windy hill, the answer to your quest for clean energy might be blowin' in the wind. A residential wind turbine can lower your electricity bill by 50–90%.

To harness wind power, a turbine sits on top of a tower that's tall enough to be well clear of buildings and trees—usually 80 to 120 feet high. When the wind blows hard enough—more than 7 to 10 miles per hour (about 6 to 9 knots)—the turbine turns, converting the wind's kinetic energy (kinetic means "related to motion") into electricity. When the air is still, your home gets its power from the standard electrical grid.

If you're considering wind-generated electricity, keep in mind that, in general, turbines aren't suitable for urban areas or suburban homes with lots smaller than one acre. Also, remember that no wind equals no power, so you don't want it to be your only energy source. Your site should have an average wind speed of at least 10 miles per hour (8.7 knots); the company that installs the turbine can use government-published wind resource data or use an anemometer (which measures wind speed) to determine how windy your spot is. For an average home, you'll want a turbine that's rated in the range of 5 to15 kilowatts (Calculate power use for free).

Be sure to do the following before you start building a turbine:

Check local regulations. There may be set-back laws, for example, that restrict how close your turbine can be to your neighbors' properties.

Visit a residential turbine in action before you commit. They aren't silent, and you may decide that they're too noisy for you.

Do a cost-benefit analysis. Turbines are expensive; it can cost $10,000–$25,000 to get a small one installed. Make sure that the energy savings you anticipate are worth it. (If the turbine generates more power than you need, you may be able to sell the excess to the local utility company; call to find out.)

Note

Hybrid electricity-generating systems combine solar and wind resources. This makes sense, because the peak operating times for wind and solar systems are at different times of the day and year—in winter, the sun is weaker and wind is typically stronger; in summer, the sun is brighter and the wind tends to be weaker. Wholesale Solar (www.wholesalesolar.com) sells this kind of system for homes.

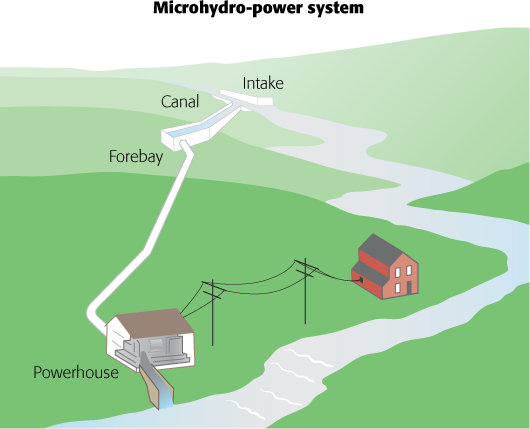

People have been harnessing the power of flowing water ever since they used waterwheels to operate mills. If a river or stream runs through your site, you may be able to use it to create electricity—called microhydro power—and it can generate enough for your whole home.

A microhydro-power system diverts running water and uses it to turn a turbine. The turbine spins a shaft, which can do things like power a pump or create electricity. After it turns the turbine, the water rejoins the river or stream it came from, so these setups have minimal impact on the environment.

Note

In most situations, your home can be as far as a mile away from the turbine and still get electricity from it.

Using running water to create electricity has a couple of advantages over PV cells or wind turbines:

The river keeps flowing—and generating power—day and night, whether it's sunny or cloudy, windy or calm.

A relatively small amount of water flow (as little as two gallons per minute) or a vertical drop of just two feet between the intake (where the water gets diverted from the stream to power the turbine) and the exit (where the water rejoins the stream) is enough to generate electricity.

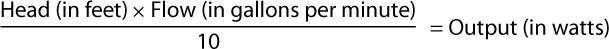

As with solar and wind power, before getting started with a microhydro setup, you need to make sure your site is suitable. Two factors determine how much power the system can produce:

Head. This describes the vertical distance that the water travels between the intake and exit points.

Flow. This is the volume of water.

To calculate how much electricity you can get from your site, use this formula:

As you can see, the greater the vertical drop and the faster the flow, the more energy gets generated.

Biomass is a fancy term for renewable fuel sources. It's applied to things that are grown for fuel and can be replenished with a new crop, like corn or wood pellets, even soybeans, nutshells, and dried cherry pits. Biomass burns more cleanly than regular firewood (but less so than natural gas), sending less ash and greenhouse gases into the air.

If you're interested in heating your home with biomass, you need an EPA-certified stove that limits the amount of particulates (ash) it emits. Look for a label that estimates the stove's smoke output, efficiency, and heat output, or go to www.epa.gov/woodstoves and download a list of certified stoves.

Note

Make sure you get the right stove for your home. A stove's British thermal unit (BTU) output indicates how much space the stove can heat; a higher maximum BTU heats a larger area. When buying a stove, ask how many BTUs you'll need to heat your home.

After you've installed a stove, you'll need biomass to burn in it, which you can get at hardware stores, stove companies, and farm supply stores. The fuel is rated by ash content—the lower it is, the cleaner it burns. That means fewer particulates released into the air and less time you'll spend cleaning the stove. A good pellet stove produces very little ash and you'll probably only need to clean it about once a week.

Water is an increasingly precious resource and everyone should do their part to use less. So build water conservation right into your new home or renovation project by doing things like installing a rainwater-harvesting system (Outdoors) and reusing gray water (Mowing Tips). And be sure to work with your contractor to:

Install efficient faucets. The U.S. EPA puts the WaterSense label on highly efficient bathroom faucets, so insist on such fixtures.

Go with low-flow showerheads. These can save tens of thousands of gallons of water from going down the drain each year. Look for ones with WaterSense labels or those with a flow rate of 2.5 gallons (or less) per minute.

Opt for less water pressure. Nobody likes a wimpy shower, but you may not need the water going full-blast, either. Ask your plumber to install pressure-reducing valves to slow the flow. According to the EPA, changing the pressure from 100 pounds per square inch to 50 psi reduces water flow by about a third.

Put in low-flush toilets. Since 1994, all toilets produced for homes in the U.S. can use no more than 1.6 gallons per flush, so any new toilet you install will be efficient. If you're outside of the U.S., look for models that use 1.6 gallons of water (or less) per flush.

Tip

Efficient toilets can earn the EPA's WaterSense label, too. Learn more about WaterSense products—including brands and models—at www.epa.gov/watersense.

Check out composting toilets. A composting toilet uses little or no water and produces no waste. Its final product is compost you can use to enrich your lawn or garden. These toilets come in several different designs, but they generally work the same way, using heat and oxygen to break down waste. This process gets rid of germs and reduces the volume of the waste by as much as 90%. (And yes, you can dispose of toilet paper in a composting toilet.) With most models, you have to aerate the waste from time to time (usually by rotating a drum, which you can do by hand or use an electric motor) to make sure that oxygen is doing its job. After a few months, the compost is ready to use.

Note

Local regulations about using toilet-produced compost vary, so check with your city and state before installing a composting toilet.

Will a composting toilet make your bathroom smell like an outhouse? Not if it's properly installed. Regular sewage smells bad due to anaerobic decomposition, which happens in low-oxygen environments, like when the waste is submerged in water. That produces methane and other smelly gases. But a composting toilet uses aerobic bacteria to break down the waste in the presence of lots of oxygen. The process gives off carbon dioxide, water, beneficial enzymes—and no nose-wrinkling smells.

Incorporating efficient systems into your new home or remodeling project is an important part of green construction, and so are the supplies you choose. From lumber to flooring, roof shingles to insulation, green materials come from sustainable sources and are made using responsible manufacturing processes. When choosing materials for building or remodeling, here are some questions to ask:

Does it come from a renewable resource? Look for FSC-certified wood (A Greener Lawn), cork, rubber, recycled and reclaimed materials, and so on. Keep reading for lots of suggestions.

Was it produced responsibly? Try to support companies who strive to minimize energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and waste.

Is it made of recycled materials? Products with recycled content trump ones made from virgin materials.

Is it repurposed? Whenever possible, use salvaged, reclaimed, or refurbished supplies. In one stroke, you keep stuff from being thrown away and cut back on the resources that would be used to make and transport brand-new goods.

Is it durable? The material should last a long time, not require replacement in a few years.

Is it locally available? Pick products made near your site over those shipped a long ways by pollution-producing trucks.

How much packaging does it have? Do your part to reduce wasteful packaging (Rejecting Wasteful Packaging) by selecting products that have little or none, or that use recycled packaging.

The next few sections have lots of suggestions for specific kinds of materials.

Tip

The Pharos Project (www.pharoslens.net) helps consumers evaluate and compare building supplies based on resource sustainability, health, and social justice. The Pharos Lens, a wheel-style graphic that rates products in these categories, appears on product labels and gives additional info about recycled content, durability, and country of origin. Look for the Lens when choosing your materials.

In the U.S. and elsewhere, wood is the material of choice for framing homes. It's a renewable resource, but you want to make sure the wood for your project was harvested from a well-managed forest that grows and harvests trees sustainably instead of plundering old-growth forests. Even with sustainable techniques, the sheer volume of wood used for construction has raised concerns about whether existing resources can support demand. And smaller forests lead to diminished air and water quality, contribute to global warming, and harm ecosystems and biodiversity.

Look for wood that's been certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (A Greener Lawn). FSC-accredited certifiers give the FSC seal of approval to lumber from forests that are well managed, respecting indigenous peoples and the environment.

Salvaged or reclaimed wood is another option. It doesn't use a single new tree, and keeps old lumber from being thrown away. You can get reclaimed lumber from national dealers like Elmwood Reclaimed Timber (www.elmwoodreclaimedtimber.com) or Reclaimed Lumber Company (www.reclaimed-lumber.com). Make sure that the wood has been cleaned and is free of hidden nails (the company should use a metal detector to make sure). And the wood should be kiln-dried to get rid of any creepy-crawlies that might be living in it and prevent warping.

Tip

Tell your contractor you want to use efficient framing techniques to conserve materials. For example, if the contractor uses a 2 X 6 construction method for exterior walls, he may be able to space the studs apart by 24 inches on center (as opposed to the standard 16 inches on center). This method saves lumber and leaves more room for insulation.

And consider alternatives to wood: Plastic lumber, made from recycled or reclaimed plastic, may work for things like decks, walkways, and fencing. It doesn't rot and lasts pretty much forever. (There are also plastic-wood composites.) Plastic lumber comes from two main sources:

Recycled high-density polyethylene, the kind of plastic used to make milk containers.

Recycled polyvinyl chloride (PVC), the kind that's in shower curtains and car dashboards.

There are some downsides to plastic lumber. For one thing, it requires more energy to manufacture than regular wood products. And composites can't be recycled and may end up in landfills. Keep these issues in mind when you're thinking about incorporating plastic lumber into a project.

Good insulation is essential to your home's energy efficiency, but what's the best kind to use? Traditionally, the most common materials are fiberglass and petrochemical-based products such as polyurethane and polystyrene. Fiberglass insulation often contains recycled material, but its fibers can get inhaled (similar to asbestos; see Asbestos), and it sometimes contains formaldehyde. Consider these alternatives when choosing insulation:

Cellulose. Recycled newspapers can be turned into cellulose insulation, which is treated with chemicals to protect it from fire and insects. You can also find borate-treated cellulose, which is processed with a natural substance derived from the mineral boron.

Soy. Instead of sprayed-in foam insulation made from polyurethane, check out soy-based foams.

Cotton. The same fiber that's used to make warm sweaters can keep your house cozy, too. Cotton insulation is made from mill waste and low-grade and recycled cotton that's treated with a nontoxic fire retardant. It's available in batts—big rolled-up layers like the kind fiberglass insulation comes in—and as loose fill. There's no guarantee, though, that this kind of insulation comes from organic farms (nonorganic cotton farming uses lots of pesticides or genetically modified cotton; Genetically Modified Foods outlines some of the problems with genetically modified crops).

Cementitious foam. This blow-in foam is made from magnesium oxide (which is derived from seawater) and blown through a membrane with air to create bubbles. The resulting insulation is nontoxic and nonflammable.

Perlite loose fill. Perlite is a naturally occurring volcanic rock that expands when heated past 1600° F (871° C). It's often used as loose fill in masonry construction, filling the cavities, for example, in concrete blocks.

The drywall that forms the basis for your home's walls is mostly gypsum (a soft, inert mineral). To produce drywall, a layer of gypsum plaster is put between sheets of paper, the whole thing is pressed, and then dried in a kiln. This process takes a lot of energy—according to one estimate, it accounts for 1% of the total U.S. energy use. To minimize the carbon footprint of your building materials, look for drywall made from recycled or synthetic gypsum. Synthetic gypsum uses recycled and reused materials such as coal fly-ash, which comes from power-plant exhaust and would otherwise be waste. (More than 80% of the coal fly-ash sold in the United States goes into gypsum board.) Look for drywall made of at least 75% recycled content, including at least 10% post-consumer recycled content.

Warning

In 2008 and 2009, some homeowners complained that drywall imported from China gave off sulfur gases that caused health problems, including headaches and respiratory problems, and corroded copper pipes, coils, and wiring. Ask your contractor where your home's drywall comes from, and make sure it's a reputable source with a track record of safety.

When it comes to what's underfoot, you've got lots of green choices. If you're installing hardwood floors, be sure to buy FSC-certified (A Greener Lawn) materials. Consider using reclaimed or salvaged wood, as well, and make sure that any finish applied to the wood is low in VOCs (VOCs and You). Here are some other natural flooring options:

Bamboo. Bamboo (which is technically a grass) grows quickly—growers can typically harvest it 4–6 years after planting it—so it's highly renewable. Some bamboo flooring, however, is made with adhesives that can off-gas formaldehyde, so ask about such emissions if you're considering this material.

Tile. There are all kinds of tile to choose from, including ceramic and terracotta, stone (preferably reclaimed), and a wide variety made from recycled materials, like glass, ceramic, porcelain, and even aluminum. Be sure to use a low-VOC adhesive to install them.

Terrazzo. This kind of flooring, which can be made from recycled glass, looks like marble.

Cork. Most of the world's cork comes from Spain and Portugal, where it's harvested from cork oak trees that typically live for a couple of centuries, shedding their bark every decade or so. The bark gets made into flooring that comes in squares or sheets.

Carpeting. The greenest options for carpeting are all-natural or recycled. Look for carpet made from things like organic wool or cotton, sisal (which comes from the agave plant), coir (made from coconuts), sea grass, and jute (made from plants native to Asia; it's what burlap is made of). Recycled carpet is made from old carpet, other textiles, or PET plastic (the kind soda bottles are made from).

Linoleum. You may think of linoleum as the ugly flooring in your grandmother's kitchen. But take a look at today's designs before you dismiss this earth-friendly flooring. It's made from natural materials—linseed oil, pine resin, sawdust, cork dust, limestone, natural pigments, and a jute backing—and is long lasting and low maintenance. So Grandma was more of an environmentalist than you thought.

Note

Some people confuse linoleum with vinyl flooring, but they're different. Vinyl flooring is made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Both making and incinerating PVC produces dangerous dioxins, and the phthalates (chemicals added to PVC to soften it) in it may exacerbate allergies and asthma. Make sure you're getting real linoleum, not vinyl.

These cabinets handy for storing things, but you don't want to have to hold your breath around them. Most of 'em are made from plywood, particle board, or fiberboard—all of which can off-gas formaldehyde. Better options are salvaged cabinets or ones made from regular wood, reclaimed wood, or metal.

A good roof keeps the elements out, is relatively lightweight, and lasts a long time. Environmentally friendly materials include metal (look for lots of recycled content), fiber-cement composite (preferably made with fibers from recycled wood or paper), recycled shingles, and rubber tiles.

Tip

The heat island effect refers to the fact that built-up areas tend to be hotter than rural ones—which affects the local environment and its ecosystems. Roofing materials are a major cause of the heat island effect—dark-colored roofs absorb and give off heat. If you live in a town or city, choose a light-colored roof.

Low-VOC paint contains fewer volatile organic compounds than the regular kind. (Flip back to the box on VOCs and You to read all about VOCs.) For interior walls, use low- or no-VOC paint. Low-VOC means it can have no more than 250 grams per liter (g/L) of VOCs if it's latex based, or 380 g/L if it's oil based. And even if the label says "no VOCs," the paint can still have VOCs up to 5 g/L of the smelly chemicals. No matter what kind you choose, when you're painting inside, be sure to open the windows and have fans going for good ventilation.

Tip

Green Seal—a nonprofit organization that promotes safe, healthy, environmentally responsible products—certifies paint that meets its standards, which include a maximum of 50 g/L of VOCs. To find Green Seal–approved paints, go to www.greenseal.org, click "Find a Certified Product/Service," and then click "Paints and Coatings".

Because of environmental problems caused by the manufacture of PVC (Kitchen and bathroom cabinets), avoid vinyl siding. Instead, consider using siding made of recycled steel or aluminum, fibers and cement, or wood or other cellulose fibers bonded together (this last kind is called reconstituted siding).