1

The Beginning of the End

FLANKED BY THE LORD MAYOR OF LONDON AND THE ARCHBISHOP OF Canterbury, Winston Churchill stood up in the Mansion House on November 10, 1942, to deliver some good news: Britain had at last won a decisive victory in the Middle East. Rightly, the prime minister sensed that the war had reached a turning point, but he was determined that his words should not encourage complacency. “Now this is not the end,” he went on to warn, before turning the phrase for which his speech is famous. “It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”1

Whatever the moment represented, it had certainly been a long time coming. For three whole years the news had invariably been bad. “In our wars the episodes are largely adverse, but the final results have hitherto been satisfactory,” Churchill reflected, before reminding his audience how “in the last war we were uphill almost to the end.” Then he quoted a former Greek prime minister who had once observed that Britain always won one battle—the last. “It would seem to have begun rather earlier this time,” he suggested, to laughter. It was the sound not of hilarity but of relief.

For “largely adverse” was a typically British understatement when used to describe a war in which disaster had pursued disaster. After Norway and Dunkirk in 1940, and Greece and Crete in 1941, there was no hiding the fact that 1942 had also been calamitous so far. In February the German pocket battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst had steamed through the Straits of Dover unopposed. A few days later Singapore surrendered, and the Japanese marched eighty-five thousand British Empire troops into a captivity many of them would not survive. Churchill had depicted the thirty-three-thousand-strong garrison of the Libyan port of Tobruk as the linchpin of British resistance to Hitler. But in June, while he was in Washington to confer with Franklin D. Roosevelt, it too had capitulated. He would not forget how the president had wordlessly passed him a pink slip of paper bearing the news before solicitously enquiring if there was anything he could do to help. “Defeat is one thing;” Churchill wrote in his memoirs, “disgrace is another.”2

The beleaguered prime minister had returned from Washington to London to face down criticisms that his strategy was failing as well as calls to resign his role as minister of defence—a tactic that he reckoned was the first step along the road to forcing him out altogether. He was a man who “wins debate after debate and loses battle after battle,” claimed one skeptic during a parliamentary debate on his direction of the war. Although Churchill easily survived the vote of confidence that followed the debate and set off soon afterward to see the situation in Egypt for himself, it was hard to deny that his critics had a point, not least when the Dieppe Raid proved a fiasco that August.3

At the Mansion House, Churchill now finally had something he could brandish at his critics. “Now we have a new experience. We have victory—a remarkable and definite victory,” he announced, to cheers. At the end of October, a predominantly British force had attacked the Germans at El Alamein; a few days later, once the midterm elections had passed, United States troops landed at the other end of North Africa. The German army, now in a headlong retreat to avoid being pinched between the Americans and British, had been “very largely destroyed as a fighting force,” the prime minister declared.

If, in the first half of his speech, Churchill sounded cautiously optimistic, in the second half, he bristled with defiance because he knew what would come next. Having been a minister during the previous war, he knew from personal experience that the prospect of the end of the current one—no matter how long the final victory might be in coming—would again trigger a debate between Britain and the United States about the shape of the peace.

The signs were that history was repeating itself. From the safety of the other side of the Atlantic, Roosevelt was already arguing that there was no room for empire in the postwar world, just as his predecessor Woodrow Wilson had done during and after the last war, resisted by the British all the way. When, at the armistice in 1918, Churchill’s private secretary declared that he was so grateful for the American contribution to the victory that he wanted to kiss Uncle Sam “on both cheeks,” Churchill had retorted: “But not on all four.”4

By November 1942 Churchill must have feared that, were Uncle Sam to present his other two cheeks to him, it might be difficult to say no. Over a year earlier, after Britain allied herself with Stalin following Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union, he had received a summons to a meeting off Newfoundland from Roosevelt: he crossed the ocean half hoping that the president might declare war there and then. He was to be disappointed, for over dinner on August 9, 1941, Roosevelt, who was wondering what secret deal the British might have stitched up with the Russians, instead asked him to commit to a joint declaration respecting the principles of self-determination and free trade for “all peoples.” Churchill knew that both concepts had ominous implications for Britain and her empire, but he did not dare annoy the man on whom his hopes of victory depended. He and his advisers hurriedly drafted the declaration, which Roosevelt then significantly rewrote, but Churchill then managed to dilute the rewrite somewhat by deleting the president’s reference to trade “discrimination”—the practice on which imperial preference* hinged. But he had no choice but to agree to what would become known as the Atlantic Charter, and it was clear the issues that it broached were not going to go away, particularly once the United States started footing the bill for Britain’s war effort and then, after Pearl Harbor, joined battle herself.

Knowing that he could not win the war single-handedly, Churchill had tried from the outset to “drag the Americans in.” Now that he had managed to do so, he was having to confront the consequences of that strategy’s success. It was only at the Mansion House after the victory at El Alamein that he felt strong enough to mount a sturdy public defense of the empire against the incoming American assault. Although he readily acknowledged that it was American weapons and equipment that had finally enabled a fight with the Germans at El Alamein on equal terms, he emphasized that the battle had been “fought throughout almost entirely by men of British blood.” For a year the British Empire had provided the only resistance to Hitler, he argued, and he had no plans to acquiesce to its breakup now. Britain was not fighting “for profit or expansion,” he insisted, rebutting an accusation that was regularly made—and not just by the enemy—and the time had come to make something else very clear. “We mean to hold our own,” he stated, to cheers. “I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire… I am proud to be a member of that vast commonwealth and society of nations and communities gathered in and around the ancient British monarchy, without which the good cause might well have perished from the earth. Here we are, and here we stand, a veritable rock of salvation in this drifting world.” It is often assumed that these pointed remarks were aimed at Roosevelt. But in fact, Churchill had another American in mind.

NINE WEEKS EARLIER, when the victory proclaimed by Churchill was only a distant and uncertain prospect, a four-engine American bomber had landed at Cairo airport with an important passenger aboard. Once it had taxied to a halt, its padded side door swung open to reveal a large, familiar-looking man dressed in a rumpled suit and pith helmet, who then half raised a hand to acknowledge the small crowd that had turned out to greet him.

Wall-to-wall press coverage of the U.S. presidential election two years earlier made Wendell C. Willkie instantly recognizable: he was the Republican candidate, the dark horse from Ellwood, Indiana, with the booming voice and seismic handshake who had challenged Roosevelt for the presidency but lost. Now made a special envoy by the very man who had defeated him, he had come to Egypt on a thirty-one-thousand-mile odyssey around the world.

This journey was to be a formative experience for Willkie—and one that had dramatic implications for Britain, for when the American politician set out from the East Coast at the end of August 1942, he was one of the most energetic American supporters of Britain. But by the time he reached the West Coast forty-nine days later, he had turned into one of her most outspoken critics. With hindsight it is clear that Willkie helped to trigger the beginning of the end of Britain’s empire in the Middle East.

After posing for press photographs beside his aircraft, Willkie left for the American embassy where the ambassador briefed him on the fragile situation. Ten weeks had passed since the German general Erwin Rommel captured Tobruk and chased the British back to their prepared defenses at El Alamein, just seventy-five miles west of Alexandria. Until that point, Cairo had escaped the rigors of the conflict. The atmosphere of easygoing calm was shattered on July 1. On what was soon dubbed Ash Wednesday, the British embassy and military headquarters, in anticipation of an imminent German attack, incompetently burned their files, scattering charred fragments of secret information and seeding panic across the city.

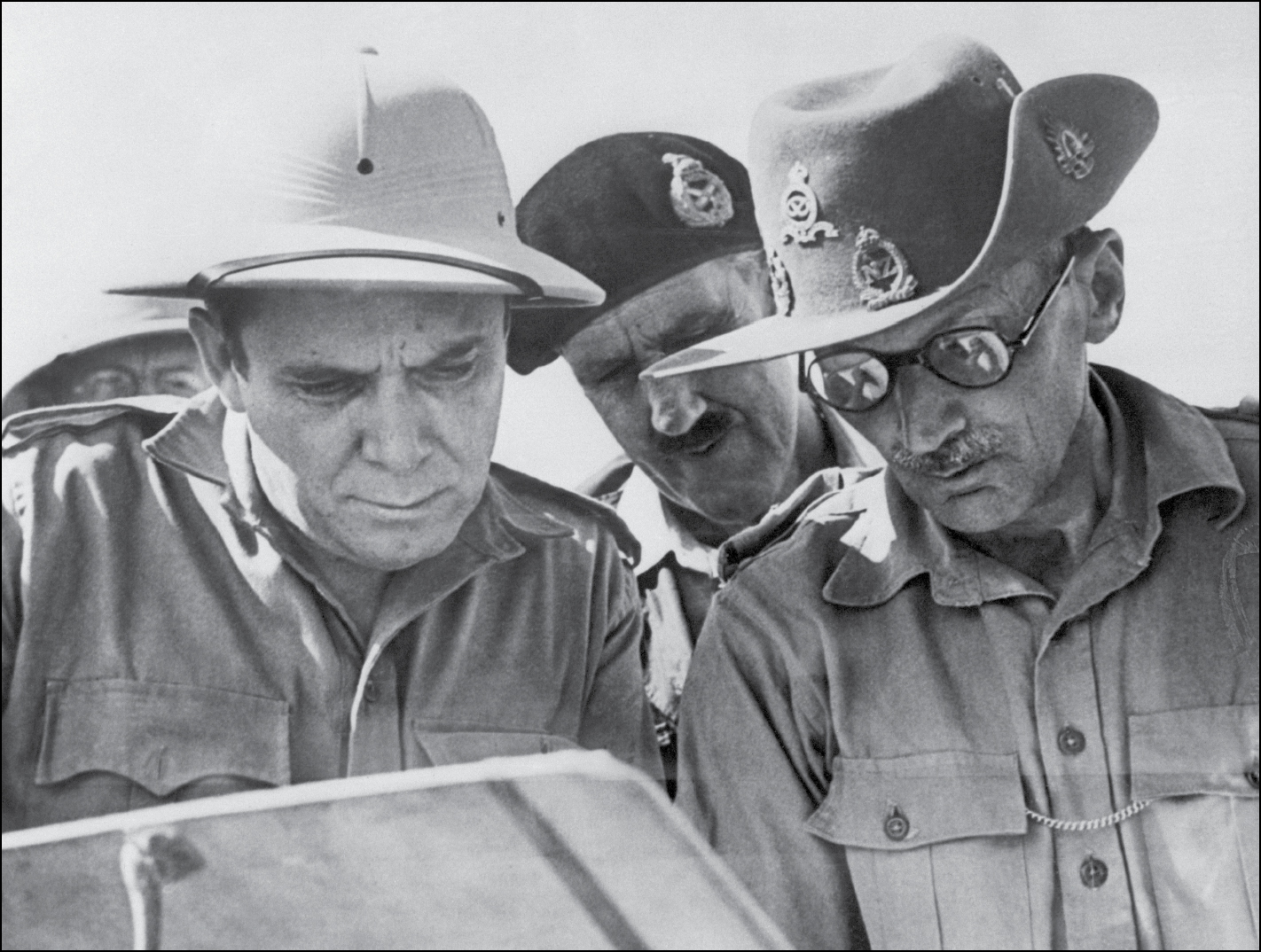

Willkie and Montgomery study a map, August 1942.

It was soon after this that Churchill had appeared in Cairo. Having survived the vote of confidence in Parliament, he then flew to Egypt so that he could visit the front, fire the general in command, and insist that his order to fight to the last man must, if necessary, be carried out. All the same the American ambassador was “not hopeful about the future,” Willkie recollected. He blamed “British bungling.”5

The precarious military situation was made worse by the fact that relations between the British and the Egyptians were awful. The British had invaded Egypt in 1882 in order to take over the Suez Canal and safeguard the route to India, and they had never left. “We do not govern Egypt,” Britain’s first consul-general in the country would claim, “we only govern the governors of Egypt.” It was a subtlety lost on the general population. The British let Egypt remain part of the Ottoman Empire, run by a khedive who paid homage to the Ottoman sultan, an arrangement that lasted until the Ottomans declared war on Britain in November 1914. At that point the British dismissed the khedive, declared his uncle sultan, and made Egypt a protectorate. That lasted until 1922, when the sultan declared himself king and the country independent.6

Egyptian independence had come at a cost that made it meaningless, however. To gain their freedom, the Egyptians were obliged to acquiesce to a treaty that granted Britain the right to station ten thousand troops along the Suez Canal and made her responsible for defending the country in the event of an attack, an arrangement that sowed the seeds of the 1956 Suez crisis. The outbreak of war in 1939 brought hundreds of thousands of British imperial troops back to Egypt and with them roaring inflation and food shortages. The invasiveness of the measures required to defend the country would cause endless friction between the Egyptians and the British.

The man at the center of this trouble, whom Willkie met after his briefing from the United States ambassador, was the current British ambassador to Egypt, Sir Miles Lampson. A six-foot-five-inch bully who had long believed Egypt should simply be sucked into the British Empire, he operated out of an office at 10 Sharia Tolumbat in the city, which was known for short as Number Ten. Willkie soon realized why. Although nominally the most senior diplomat in Egypt, Lampson was “for all practical purposes its actual ruler.”7

What riled Lampson most was the way in which Egypt’s king, Farouq, allowed pro-Axis sentiment in his country to flourish. Six months earlier, on February 4, 1942, he had tried unsuccessfully to lance the boil, causing an incident that had only made the situation worse. Following the resignation of the then Egyptian prime minister, the ambassador had issued an ultimatum to Farouq to ask a more compliant politician to take charge or else to abdicate. When, at six o’clock that evening, the king declined to do as he was told, the burly British pro-consul then paid a visit to the royal residence, the Abdeen Palace, with soldiers, tanks, and a letter of resignation, which he presented to Farouq for signature.

Farouq backed down, and Lampson confessed in his diary at the end of a long evening that he “could not have more enjoyed” the confrontation, but the cathartic effect of what would become known as the Abdeen Palace incident was brief. The following day he noted how “we are still faced with the fact that we have a rotter on the Throne and if things go badly with us he will be liable to stab us in the back.” His relationship with the king was a write-off.8

Willkie met both Lampson and Farouq and then headed to the front to see General Bernard Montgomery, who had just taken charge. Given the American ambassador’s views on British military prowess, Willkie’s own expectations were low, but he found Montgomery’s “wiry, scholarly, intense, almost fanatical personality” most impressive. Egged on by the British general, who had repelled an attack by Rommel six days earlier, he declared to the reporters who were accompanying him that they were witnessing “the turning point of the war.”9

For Willkie the burning question was what the British thought would happen once the war was won. Between Cairo and the frontline, he broached it with a group of British officials over dinner in Alexandria. “I tried to draw out these men… on what they saw in the future, and especially in the future of the colonial system and of our joint relations with the many peoples of the East,” he later wrote. Their answers unsettled him. “What I got was Rudyard Kipling, untainted even with the liberalism of Cecil Rhodes.… these men, executing policies made in London, had no idea that the world was changing.… The Atlantic Charter most of them had read about. That it might affect their careers or their thinking had never occurred to any of them.” It was just as he had feared, and he was in no doubt that the British prime minister was to blame.10

WILLKIE HAD BEEN skeptical about Winston Churchill ever since his first encounter with the British prime minister in early 1941, ten months before the United States entered the war. His defeat by Roosevelt was recent, but his presidential ambitions were undimmed. After all, he reminded himself, he had won more votes than any previous Republican candidate; he might now be president were it not for six hundred thousand voters spread across ten states. Although he was already hoping to stand again in 1944, he was an outsider with no political office: he needed to find other ways to stay in the public eye. That was why, in January 1941, he had decided to make sending military aid to Britain his next cause.

By doing so, Willkie threw himself into the greatest political controversy of the moment in the United States. When isolationism was at its height during the 1930s, Roosevelt had been obliged by public pressure to pass a series of Neutrality Acts, which aimed to make America’s embroilment in another world war less likely. The laws stopped the administration from selling arms or lending money to belligerent foreign states. Following the outbreak of war, Roosevelt managed to persuade Congress to dilute the restrictions, allowing arms purchases on cash-and-carry terms, but he was unable to end the veto on loans. By the end of 1940, this was a pressing problem. “The moment approaches,” Churchill warned the president in a letter, “when we shall no longer be able to pay cash for shipping and other supplies.”11

Although Churchill regarded the Atlantic as the bond uniting Britain and America, Willkie and Roosevelt each saw it as a rather useful moat. They knew that the longer Britain held out, the later America would have to enter the conflict, if at all. Churchill’s letter therefore alarmed Roosevelt: at the end of December 1940, the president declared his country “the arsenal of democracy” and proposed a workaround to Congress. Under the Lend-Lease Act, the United States would lend Britain the equipment she needed to fight, in expectation not of payment but the return of the materiel or a like-for-like replacement at the end of the war. Willkie came out in support of this measure midway through the following month and announced that he was going to London to investigate. “Appeasers, isolationists, lip-service friends of Britain will seek to sabotage the program,” he warned, “behind the screen of opposition to this bill.”12

Ever searching for consensus, Roosevelt thoroughly approved of Willkie’s mission. The passage of Lend-Lease through Congress was no foregone conclusion, as isolationism was widespread and cut across party lines; the president was keen to show that there were Republicans who felt the same way that he did. He also wanted his old rival to deliver an encouraging message to Churchill. The prime minister had been seeking reassurance since late December, but until very recently, Roosevelt had been reluctant to give it.

That delay reflected an uncomfortable fact. Not only were there political grounds for Roosevelt’s silence, there were personal ones as well. Churchill’s behavior at a dinner in 1918 (when, said Roosevelt, he had “acted like a stinker… lording it over us”) and several hostile articles that he had then written about the New Deal in the 1930s had left the president with the impression that the prime minister profoundly disliked him. It took a visit to London by his trusted, spiky adviser Harry Hopkins to convince him that this was not the case. Finally, on January 20, Roosevelt wrote a letter for Willkie to give to Churchill, including in it some lines of Longfellow, which, he offered, applied “to you people as it does to us”:

Sail on, Oh Ship of State

Sail on, Oh Union strong and great

Humanity with all its fears

With all the hope of future years

Is hanging breathless on thy fate.

On January 26, 1941, Willkie flew to London; he handed over the missive when he had lunch with the prime minister the following day.

Here was the assurance Churchill had been longing for. In a reply to Roosevelt the next day, he wrote that he was “deeply moved” by the president’s letter, which he interpreted as “a mark of our friendly relations, which have been built up telegraphically but also telepathically under all the stresses.”13

FOR CHURCHILL, WHO was trying to draw the United States into the war, Willkie’s appearance in London in the midst of the Blitz presented a fantastic opportunity. His mother, Jennie, was a New Yorker, and he believed there was a visceral connection between Britain and America. Oblivious to the waves of Irish, Jewish, and Eastern European immigration that had transformed the United States in recent years, he felt sure that nothing would “stir them [the Americans] like fighting in England” and that “the heroic struggle of Britain” represented the “best chance of bringing them in.” With this in mind, on Willkie’s arrival, he later recollected “every arrangement was made by us, with the assistance of the enemy, to let him see all he desired of London at bay.” The press followed the American everywhere he went: “Veni, vidi, Willkie,” wrote one newspaper of his visit.14

Having spent the week in London, on Saturday night Willkie was driven out into the countryside to stay at Chequers with Churchill, who had rather theatrically told him he would be safer there. The prime minister enjoyed entertaining foreign guests, not least because the government hospitality fund would then foot the bill, and the two men passed a convivial eight hours together. “He is the most brilliant conversationalist and exchanger of ideas,” Willkie reported of his host. “He can thrust. He can take, appreciate and acknowledge your thrusts.”15

With the British taxpayer rather than the cash-strapped Churchill paying, there had been plenty to drink, Willkie reflected afterward, and he had drunk more than the prime minister, whose own capacity for alcohol was fabled. Despite one similarity—both had switched parties in their pursuit of power—the two men did not have a great deal in common. They came from different generations—Churchill was being shot at on India’s North-West Frontier before Willkie was even five years old—and the prime minister’s romantic conception of the blood ties that linked Britain and America must have sounded strange to the son of German immigrants to Indiana. There is no question that Willkie detested imperialism; what Churchill made of Willkie’s views on race and empire, we do not know. The prime minister only recorded “a very long talk with this most able and forceful man.”16

Back in London, Willkie praised the prime minister’s “dauntless courage” and “inspirational leadership” in public, but in private he was critical. Although it was clear that the British people were fully behind Churchill, the late-night conversation at Chequers had revealed that the prime minister was “subject to no doubts about his own greatness and importance—his supreme importance as the greatest man in the British Empire,” and Willkie suspected that he did not listen to advice. At a dinner the following Thursday, Willkie admitted that, although the prime minister might be the right man for the country at that moment, he was “not so sure, however, that Mr. Churchill would be so valuable a leader when it came to the post-war period and economic adjustments and reconstruction were necessary.” Churchill could speak “like a Demosthenes and write like an angel,” he told Vice President Henry Wallace on his return to Washington, but he was altogether “too self-assured.” It was clear, thought Wallace, that Willkie “had no confidence in Churchill.”17

Because there was no political advantage in making these doubts public, Willkie kept his counsel. After being fêted for ten days in Britain, he was dramatically summoned home by the U.S. secretary of state to testify on his experience in the Senate. When he arrived back at LaGuardia Airport four days later, he immediately reassured waiting reporters that “what the British desire from us is not men, but materials and equipment.” That same day Churchill, whom he had fully briefed on the sensitivities of the American debate, made a radio broadcast. In it, he quoted from Roosevelt’s letter and responded to it. Echoing Willkie, he made no mention of needing American manpower to help fight the war. “Give us the tools and we will finish the job,” he growled instead.18

Before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in Washington on February 11, Willkie faced one of the men he had beaten to the nomination the year before. When Arthur Vandenberg, a prominent isolationist, asked him whether his proposal to supply Britain destroyers to safeguard its convoys would not embroil the United States in the war, Willkie argued that “the odds on America keeping out of the war come from aiding Britain.” Having taken the measure of Churchill, he then added an important further argument for American intervention: “If American aid was effective the United States could dominate what happens afterward and influence the type of peace that is finally written.” A day later, following the hearing—in which one of Vandenberg’s colleagues accidentally called Willkie “Mr. President”—the committee voted decisively in favor of Lend-Lease. The Senate passed the bill the following month. The uses to which Britain then put Lend-Lease would become a bone of contention forever after.19

Although Willkie was not directly involved in Roosevelt’s effort to bind Churchill into the Atlantic Charter that August, the charter was a manifestation of Willkie’s desire that the United States should shape the peace. Willkie did not see Churchill again until the prime minister paid a hasty visit to Washington after Roosevelt had declared war following Pearl Harbor. Willkie may not have liked Churchill, but he did not dislike him so much that he did not want to be seen with him. With an eye on 1944, Willkie spied a photo opportunity that would reinforce his image as the president-in-waiting and asked for a meeting.

A MEETING BETWEEN Churchill and Roosevelt’s main political rival was always going to be sensitive. When earlier that year the president had found out that Willkie was trying to establish a direct channel of communication with Churchill, he was furious and asked his ambassador in London to frustrate it. “I think the Prime Minister should maintain the friendliest of relations with Mr. Willkie,” said Roosevelt, “but direct communication is a two-edged sword.”20

Churchill was, however, very keen to see Willkie. By the time that he arrived in Washington for Christmas, it was apparent that leading Republicans preferred Willkie to any other potential candidate for 1944; a Gallup poll showed that American voters thought that he was the man most likely to succeed Roosevelt, who was in visible decline. Aware that relations between the president and Willkie were tense and probably not wishing to look as if he were anticipating the president’s retirement, Churchill decided not to broach the issue with Roosevelt. Instead, unwisely, he tried to call Willkie from Palm Beach, where he was having a few days’ rest, in order to arrange a clandestine meeting. A mistake by the switchboard operator meant that he was, without realizing it, put through to Roosevelt instead.

“I am so glad to speak to you,” gushed Churchill, before asking whether the man he thought was Willkie might join him on his train for part of his return journey to Washington.21

“Whom do you think you are speaking to?” the voice came back.

“To Mr. Wendell Willkie, am I not?”

“No,” came the answer, “you are speaking to the president.”

“Who?” asked Churchill, not quite believing his ears.

“You are speaking to me, Franklin Roosevelt,” came the reply. After some small talk, Churchill brought the conversation to a close. “I presume you do not mind my having wished to speak to Wendell Willkie?” enquired Churchill. “No,” Roosevelt responded.

Churchill was not convinced by Roosevelt’s answer. Caught red-handed trying to contact his host’s rival secretly, he had no desire to embarrass himself further. Without explaining why, he denied Willkie the photograph he wanted by insisting that their meeting take place inside the White House in private. Willkie, who like many politicians was thinner skinned than he pretended, leapt to the wrong conclusion. Believing that the prime minister’s refusal was an indication that he had been written off politically by Churchill, he took umbrage. Left skeptical of Churchill by their first encounter, and slighted by the second, it would take only one more altercation, during 1942, to shatter their relationship permanently.

THE CHRISTMAS VISIT revealed other important points of tension between Roosevelt and Churchill, who had already begun to renege on the Atlantic Charter, recasting it as “a simple, rough and ready wartime statement” that was relevant to the countries conquered by Germany rather than “the regions and peoples which owe allegiance to the British Crown.” When during their talks that Christmas, the president returned to the important question of trade discrimination, which Churchill had managed to excise from the Atlantic Charter, the prime minister refused point-blank to discuss it. And the two men had to agree to differ over India to avoid a heated argument.22

Thanks to Churchill’s backsliding, by early 1942 Roosevelt was fending off questions from the press about the Atlantic Charter’s significance and scope. Behind the scenes, the president warned Churchill that he would not release Lend-Lease aid until the British government abandoned imperial preference; the fall of Singapore that February revealed tensions between Britain and her dominions that Roosevelt then exploited to force the beleaguered prime minister to concede. On the same day that the deal was signed—committing Britain and America to the “elimination of all forms of discriminatory treatment in international commerce and to the reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers”—Roosevelt made a broadcast. In it he insisted that the Atlantic Charter applied not just to the countries bordering that ocean but worldwide. That was the basic message that members of his administration would hammer home throughout that summer.23

In July 1942, Roosevelt approached Willkie to undertake another foreign mission, starting in the Middle East. His motives for doing so were mixed. He wanted Willkie to spread the word that America was determined to win the war and to shape a lasting postimperial peace. But it also suited him to have his charismatic old rival out of the way in the run-up to the midterm elections due that November. The Democrats were divided. Roosevelt hoped that this new mission would again show that the Republicans were divided too.

The offer was a godsend for Willkie. By mid-1942, he was convinced that Roosevelt was a spent force; if only he could win the Republican primary a second time, he felt confident of succeeding him in 1944. The mission appealed philosophically and politically to his instincts. It would give him a platform to speak his mind, six weeks’ continuous press coverage, and the material to write a book that would burnish his credentials as an international statesman.

* “Imperial preference” was shorthand for the protectionist system operating across the British Empire whereby Britain, her dominions, and colonies reduced tariffs so that their trade with each other enjoyed a competitive advantage over imports from third countries like the United States, which were more heavily taxed.