5

A Pretty Tough Nut

WHILE CHURCHILL AND ROOSEVELT WERE TRADING ACCUSATIONS about each other’s ambitions in the Middle East, Lord Moyne returned to Egypt in February 1944 as Britain’s new minister resident in the Middle East.

Moyne had spent the last six months in Britain sitting on the cabinet committee charged by Churchill with devising a long-term strategy for Palestine, which had instead led to a fudge. The committee had once again recommended partition, but Churchill’s instinctive dislike of the idea and Eden’s doubts about the feasibility of the broader Greater Syria scheme, which was supposed to reconcile the Arabs to the division, led the cabinet to agree that more work was needed on the detail before the new policy could be openly pursued. Moyne returned to Cairo that spring with the unenviable task of trying to make surreptitious headway on a project that had cabinet approval in principle but lacked either Churchill’s or Eden’s endorsement in practice.1

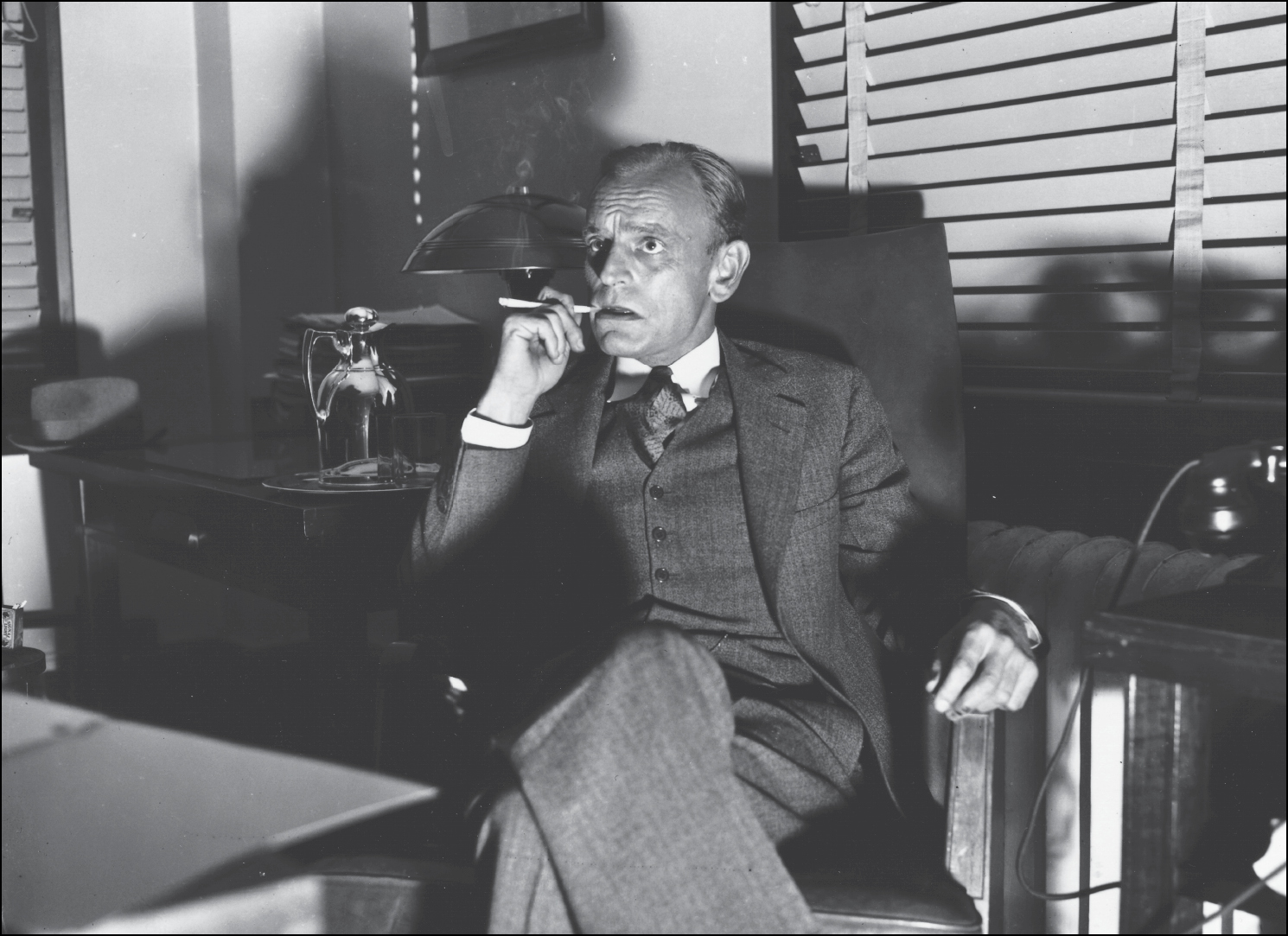

James Landis. “Landis, in spite of everyone’s best efforts, insisted in regarding the British, not the Germans, as his principal enemy,” recalled his colleague Kim Roosevelt.

To add to Moyne’s difficulties, both policies would need American support to succeed, but here the omens were not good either. During Moyne’s absence in London, an abrasive new American representative had arrived in Cairo, to whom the British ambassador Miles Lampson, newly ennobled Lord Killearn for his efforts, had taken an instant and profound dislike. James Landis had been appointed the United States’ director of economic operations in the Middle East, in the wake of the Five Senators’ criticisms of American disorganization. Killearn accused him of taking “a hectoring and bullying attitude towards the Egyptians,” an activity where he had previously exercised a monopoly himself. He recognized the new director as “a pretty tough nut” and now briefed Moyne on his new opponent.2

Landis was certainly a controversial appointment. The son of a missionary, he was the dean of Harvard Law School, a zealous, heavy-drinking, rather tortured workaholic whose low self-esteem drove him ceaselessly to prove himself. On the opposite side of the New Deal to Wendell Willkie, he had made his name drafting tough financial market regulation in the wake of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and then serving first as a commissioner then chairman of the Securities Exchange Commission in the second half of the 1930s. To make a point, he once entertained the pompous chairman of the New York Stock Exchange to a forty-five-cent luncheon brought up from the canteen to his office. Trapped in a dead-end wartime job and looking to escape a marriage that he was deliberately allowing to fail, he jumped at the opportunity to work abroad when Roosevelt offered it to him in September 1943. “Forgive me for running out again,” he wrote to the acting dean of Harvard Law School, after his appointment was announced, “but I honestly think there is a job to do there and that I may make some contributions toward our general future.”3

When Landis set out for Cairo, there was a danger that the “general future” might be bleak. The Roosevelt administration was becoming increasingly concerned about the economic challenge that peace would pose. The war effort absorbed 60 percent of industrial output in the United States: on victory, that demand would fall away, threatening mass unemployment. The answer to that problem was for the country to export itself out of trouble. It did not take long for Landis to realize, once he had reached Egypt, that such an economic strategy would place the Americans on a collision course with their British allies because the biggest obstacle to a successful American export drive in the region was the organization in which the British had invested their hopes of postwar economic revival and influence, the Middle East Supply Centre.

“I stuck my nose into it,” Landis said later. The more he looked, the more he thought that the British Empire resembled one of the great holding companies that the Roosevelt administration had tried to break up in the 1930s. One way that the British were using the Middle East Supply Centre to perpetuate their influence in the region was to handicap American exporters. On the grounds of shipping shortages, the centre limited, among many other things, the import of machines and hand tools. These restrictions not only denied American manufacturers export sales opportunities but also made the region more dependent on manufactured imports than it might otherwise have been. Again, using shipping as its justification, the centre ensured that what imports it did allow into the region came mainly from Britain rather than more distant America. That explained why Ibn Saud wore English socks.4

For Landis, the trading framework established by the British presented not just an economic but also a moral challenge to the United States. A country like Palestine, he noted, had accumulated a dollar trade surplus (principally by exporting oranges to the United States), but its inhabitants’ ability to spend those dollars on luxury American goods was constrained by the currency controls imposed by the British, which affected every country in the sterling area, of which Palestine was part.* Americans could either acquiesce to this or speak out, he said, and it was abundantly clear that he favored the latter option, for acquiescence made the United States complicit in a system whereby the British knowingly depressed living standards in the countries of the sterling area in order to protect their imperial economic system as a whole.

Landis realized that he could not resolve this problem while he was in Cairo. It was a matter of high policy that could only be settled by direct talks between senior British and American officials. Since the American ambassador seemed more interested in “the evanescent building of goodwill through tea and cocktail parties, dinners and ceremonies,” Landis decided to take up the matter himself. Flying back to Washington, he argued that it was time for the United States to question the basis of Britain’s Middle Eastern economic policy because the excuse of shipping and supply shortages, which were the supply centre’s raison d’être, were “no longer plausible.” But there he found that there was little appetite inside the government for such a confrontation in the run-up to D-Day, and he was forced to return to Egypt empty-handed.5

“Landis, in spite of everyone’s best efforts, insisted in regarding the British, not the Germans, as his principal enemy,” recalled a colleague. On his return to Cairo, he decided that his best bet was to starve the Middle East Supply Centre of personnel. Although his staff grew rapidly to fifty, and although he was the United States’ representative in the centre, just thirteen of those fifty staff worked there. Of the rest, half worked with the British on economic warfare against Germany, while the others—some of whom were OSS men working undercover—were engaged in promoting American trade. These last were the most talented, the British noticed, and their zeal was obvious. The general manager of the Egyptian State Railway said that they were badgering him for details of the railway’s current and future procurement plans. They were also adept at finding Egyptian businessmen space on flights back to the United States at a time when seats on airplanes were still in very short supply. “They have just flown a local agent for textile machinery to the USA with high priority and have offered to do the same for the Egyptian manager of one of the principal local cotton textile mills,” a panicky-sounding Killearn reported, midway through March.6

While Killearn had woken up to the fact that Landis and his colleagues threatened the British strategy of trying to corner the Middle Eastern market, Moyne was more complacent, perhaps because the Americans he had worked with during the previous war had been, in his view, inflexible and poorly organized. He felt that “we can reasonably count upon our greater experience, our superior connections and the goodwill and prestige that I believe we shall continue to enjoy for seeing us through.”7

This assumption blinded Moyne to what was actually going on. When he met Landis to discuss the Americans’ understaffing of the Middle East Supply Centre, the American, who was clearly reluctant to confront his British counterpart directly, blamed the State Department for denying him the staff he needed to support the centre. Disingenuously, he said that unless he received more personnel, he would be obliged to end American participation in the venture. Taken in by this, Moyne endorsed Landis’s request in a telegram to London.

The long-heralded Anglo-American talks about the Middle East, which opened a day later in London on April 11, 1944, provided the British with the opportunity to raise this issue. After receiving Moyne’s message, the head of the Foreign Office’s Middle East department, Maurice Peterson, gingerly raised the matter with his opposite number Wallace Murray on April 18. He had heard that “Mr Landis might be compelled to change the status of American participation in the Middle East Supply Centre to that of a mere liaison mission,” he said. “This would be a deplorable development.”8

Murray was infamous for his explosive temper, while his open contempt for British Middle Eastern policy convinced one British official that he “hates our guts… his policy is merely to frustrate our policy.” But before departing for London that spring he had been told not to rock the boat ahead of D-Day, and he was temporarily on his best behavior. “American views ran along the same lines,” he replied vaguely to Peterson’s query about his country’s attitude toward the supply centre. Then he added an important caveat. Although the centre was “useful in the war period… we should not want to perpetuate the barriers and restrictions of the system into the post-war period.” The British seized on Murray’s more positive noises to deceive themselves that “the development through MESC of an autonomous and social services institution for the ME is now agreed Anglo-American policy.” It was only six weeks later—after American manpower to support the centre’s work had failed to materialize—that the penny dropped with Moyne. “Landis… takes every opportunity offered by his position to forward American trade interests,” he wrote. “American cooperation in MESC is indeed a mere pretence.”9

BY THEN, EVENTS in Saudi Arabia had convinced the Americans of their British counterparts’ bad faith. The Americans had not forgotten the attempt by the British ambassador Stanley Jordan the previous October to filch a copy of Aramco’s concession agreement, and they were now watching the British envoy with a mixture of interest and alarm. Jordan was a career diplomat who had last served in Jeddah in the 1920s. A rather straitlaced character, he had been struck on his return to the port after a decade and a half’s absence that the condition of the ordinary Saudi had not changed at all. The only visible difference was the number of palaces that the Saudi royal family had constructed in the meantime. “Bribery and corruption are everywhere,” he reported back to London. The dependability of the British subsidy was not encouraging efforts to address the problem.10

Having shelled out £4.5 million in 1943, the Foreign Office took little persuading that it was time to trim how much it paid Ibn Saud, not least because the king’s main source of revenue, the pilgrimage, was now recovering. Since the subsidy was only ever supposed to make up for the king’s loss of revenues during wartime, in early 1944 the British took the step of withholding tariffs paid by pilgrims that they would ordinarily have passed on to the king on the grounds that they were recouping some of their previous year’s subsidy. The Saudis broke the news of this move to the American ambassador and portrayed the measure as a hostile act. The Americans, having long agonized about Ibn Saud’s growing reliance on the British, now feared that the British were using the threat of the withdrawal of their subsidy to coerce the king. Their discovery soon afterward that Jordan seemed to have orchestrated the sacking of one of Ibn Saud’s pro-American advisers only deepened their concern.

At the London talks in April 1944, Peterson raised the issue of Saudi Arabia on day two before his American opposite number Wallace Murray could do so. When Murray commented that Ibn Saud was upset that the British were withholding his money, Peterson, shifting the subject, said that the king had asked Stanley Jordan if he could recommend a Sunni Muslim financial adviser. This clearly came as news to Murray, who immediately appreciated that whoever filled this role would wield great influence and, if the king really was seeking a Muslim, that the British would find it much easier than his own government to find a suitable candidate.

The Americans queried whether the king had been so specific, insinuating that Jordan had suggested a Muslim in order to put them at a disadvantage. From Washington, the secretary of state Cordell Hull insisted that any such adviser must be an American to reflect the “preponderant American economic interests in Saudi Arabia” but conceded that the leader of a military mission, which was also being mooted, might be a British officer, in an attempt to satisfy the Foreign Office. Peterson, however, refused to give ground. In a response to Hull, he asserted that the finance expert had to be a Muslim since the king’s treasury was situated in Mecca, a city that no non-Muslim was allowed to enter.11

That response triggered an angry spat between Washington and London. Such was the collapse in trust that, when Hull answered Peterson, he suggested that Jordan and his American counterpart visit Ibn Saud together and offer him a non-Muslim British military adviser and an American financial adviser and see what the king said. If the British would not go along with this proposal, he threatened to send his own representative to see Ibn Saud alone. That proposal elicited an angry reply from Peterson, who questioned Hull’s assertion that American economic interests outweighed British in Saudi Arabia, by observing that the revenues from the pilgrimage were far greater than those from oil and would continue to be for the foreseeable future.

The two allies were at loggerheads. Although, in Cairo, Landis and Moyne managed to reach agreement that their governments would share the burden of the subsidy in future years, the dispute over the current year’s subsidy meant that payment had still not been made. By now the Americans were receiving increasingly desperate calls for money from the Saudis. The British, however, refused to budge. They had it on good authority from the Saudi ambassador to London that several of the king’s advisers, including his finance minister, habitually exaggerated the country’s problems in order to line their own pockets. By now their lack of faith in the Americans was such that they felt they could not share this intelligence with Washington because they feared that its source would be identified and dry up.

When Moyne and Landis proved unable to break the deadlock, Landis again returned to Washington for talks. At the end of July, Hull decided to act unilaterally. Earlier that year he had intimated that his government would be willing to supply ten million silver riyals to keep the Saudis solvent. He now confirmed that the United States would do this. The American calculation was that the sums involved in keeping the king happy were peanuts compared to the profits that would ultimately accrue from the oil concession, as long as they hung onto it. By doing so, they wrecked British hopes of imposing some financial discipline in Saudi Arabia, where the royalties from Aramco still passed through the finance minister’s personal New York bank account. It was, sighed Moyne, “another of the many cases we have had in the Middle East where the local American idea of cooperation is that we should do all the giving and they all the taking.”12

On September 1, 1944, a new American minister took up residence in Jeddah. Bill Eddy was, like Harold Hoskins, the son of missionaries to Lebanon: the two men were in fact cousins. Before the war he had been a teacher at the American University in Cairo, where he translated the rules of basketball into Arabic. Like Hoskins, he had then been drawn into the OSS. He would later call the moment he arrived in Jeddah as the beginning of the “American invasion of the Near East.”13

Eddy was as forceful as Landis, and it soon became obvious to Stanley Jordan that his new American counterpart meant business. The American diplomat made it clear that in the future his government was not going to allow the British to restrict the sums that the United States would pay to Ibn Saud. Jordan backed away. Following his first encounter with Eddy, he wrote to the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, arguing that it was time for them to extract themselves from any ongoing financial obligation to the Saudis. “The position of a junior partner being towed along in the wake of the Americans is… a very undignified one for His Majesty’s Government to accept,” he commented, and the advantages of sharing the subsidy with Washington were “few or none.” From Cairo, Lord Moyne agreed. “Conversations with Colonel Eddy have clearly shown that the American conception of what should be given to Saudi Arabia goes far beyond anything which we have had in mind,” he wrote, within a fortnight of Eddy’s appointment. It was an early sign of how the Americans would outgun the British financially in the years to come.14

LANDIS LEFT WASHINGTON to return to Cairo that autumn, determined to finish off the Middle East Supply Centre. The Americans insisted that the Atlantic Charter and, more definitely, the original Lend-Lease agreement had committed Britain to ending trade discrimination. Then, at the Bretton Woods conference that summer, the British had accepted a system that envisaged multilateral free trade. All this was at odds with the restrictions that the Middle East Supply Centre continued to police. When, en route for Egypt, Landis paused in London, he told British officials that his prime objective was “to cut out the red tape” that impeded American exporters selling in the Middle East. Although he was willing to accept ongoing exchange controls that limited the amount of sterling that could be exchanged for dollars, he proposed deregulating the import of all but a select list of commodities in very short supply. In fact, “the only control would be a shipping tonnage programme within which the exporters would have to keep.” Twisting another British argument, that the restrictions were necessary to prevent postwar inflation, he reassured the British that “within the present shipping situation these new proposals might mean only a small increase in imports into the Middle East.”15

The question was, what kind of imports? This was what bothered the British, and it was a legitimate concern. Although the Middle East Supply Centre had dramatically improved the region’s self-sufficiency, imports of basic commodities were still necessary. British officials wondered what would happen when American importers realized that “200 radio sets” were “a better paying proposition than their equivalent shipping space in grain or nitrates.” What was to stop Egyptian importers spending their dollar allowances entirely on luxury goods?16

Initially, the British felt that there was not too wide a gap between their position and Landis’s. That gap rapidly became a chasm when the British circulated a list of nearly a hundred wildly differing imported goods—from specific industrial and agricultural chemicals to entire categories of manufactured products including trucks, passenger cars, and furniture—that they wanted the Middle East Supply Centre to continue to regulate. The item on the list that produced the most immediate discord was tires and inner tubes. The British, whose Malayan rubber plantations were still in Japanese hands, wanted to prevent the Americans—who had created a large synthetic rubber industry—from breaking into the Middle Eastern market where a set of four retreaded tires could change hands for as much as $3,000. When Landis refused to play ball, there was nothing that the British could do about it. By the time he left the British capital, an agreement to relax import controls was in place.17

Moyne, who had been grappling with a special economic mission sent by the State Department to investigate the controls imposed by the Middle East Supply Centre, was pleased to see Landis reappear in Cairo at the end of October. At lunchtime on November 6, 1944, he offered his counterpart a lift, which the American official declined. On his return to his residence, Moyne was shot, fatally, by a pair of Jewish assassins who had been waiting for him.

Moyne did not live to see the verdict of the State Department’s mission, which sealed the centre’s fate with its conclusions that the seas were now safe enough to make import controls unnecessary and that, while Anglo-American collaboration had been real enough, it had “not at any time transformed MESC into a genuine joint undertaking.” Nor did he witness the barely veiled attack on British policy that his American counterpart made that December in what turned out to be a valedictory speech before he resigned the following month. “Peace to me is a vision of free seas, free skies, free trade and freedom in the development of ideas,” Landis declared. “It is not mercantilism, uneconomic or political subsidies, narrow nationalism, group preferences or the fascist conception of one race entitled to dominance over another.”18

Although Lord Moyne’s efforts to encourage Arab unity would lead to the creation of the Arab League, the Middle East Supply Centre, through which the British peer had hoped to prolong British dominance of the region, was dissolved on November 1, 1945. By that time, British ambitions for it were a distant memory.

* The sterling area comprised those countries that either used or pegged their currency to the pound sterling.