CHAPTER 1

Early farming households

3900–800 BC

The introduction of agriculture to Scandinavia in about 4000 BC marks the dividing line between the Neolithic and Mesolithic periods. Scandinavia thus has an agrarian history that spans at least six thousand years, while a few ecofacts from southern Denmark suggest the possibility that the advent of agriculture in fact predated the accepted start of the Neolithic period by five hundred years. This first chapter of the history of agriculture in Sweden will treat the Neolithic and Bronze Age up to 800 BC.1

Archaeology and agrarian history

Archaeological finds are silent. They are tangible in a very real sense, but they cannot convey their meaning in words. This is not the same thing as being unable to convey ideas, however. Archaeological theories and methods amount to taking a really good look at mute objects, viewing them from all angles in an attempt to understand voiceless people’s actions and ideas. The requirements of archaeology mean that the many thousands of years of prehistoric agrarian history bear little resemblance to the thousand or so years of written agrarian history. In part, this is a product of the inherent difference in the substance of archaeological finds and written remains, but it also reflects the fact that prehistoric peoples and societies were different. Prehistory is a remote, different, elusive, and extraordinarily long period.

It is the strength of a long-term perspective that phenomena that only slowly evolve, and which may appear insignificant at any given moment, can be studied in a broad overview. Fundamental changes can be distinguished from the continuous, chaotic flow of events. My main theme in this chapter, however, is the complete opposite; here it is the unchanging elements in early agricultural households–their composition, division of labour, and fundamental thinking–that are to the fore. Agriculture is one of the greatest forces of change to the landscape and the environment. Its effects are noticeable over decades and centuries, and in recent years it has become apparent that agricultural policy decisions can have consequences for the landscape from one year to the next. Yet today’s cultivated landscape began to take shape many thousands of years ago.

Beginning in about 1000 BC there were clearance cairns, lynchets, stone walls, and a good deal more to be seen lying in the landscape; remains that can be mapped and combined to form a picture of the fossil cultivated landscape of a distant past that lies as much amongst the landscape of today as it lies underneath. This fossil cultivated landscape, with its farmyards, fields, meadows, and droves, is an excellent source of information about ancient agriculture. Agriculture before about 1000 BC was very different to what it would become, and for this earlier period there are hardly any traces of a fossil cultivated landscape to study. The landscape of that era must be reconstructed with more indirect methods, which, while a challenge, is not an impossibility.

Agriculture in the Neolithic and Bronze Age used relatively simple tools. People rarely cleared stones or used the same ground for any length of time, two things that were to be the distinguishing marks of later periods. Agriculture exploited large areas of land with minimal labour –the term ‘extensive agriculture’ suits it well–which would seem to be part of the reason why no fossil cultivated landscape survives from this period. The importance of working with their own hands and their own bodies outweighed the use of draught animals. Mouldboard ploughs and harrows did not exist, nor, obviously, any machinery. Manure was not used, at any rate not systematically. Scythes and all other iron tools did not exist. This was, after all, the age of stone and bronze. Agriculture used simple technology and little energy. The designation ‘low energy technology’ is apt. However, the fact that the tools were simple does not mean that they were unsophisticated; indeed, far from it.

Silent and different people

The landscape, agriculture, and actions of the prehistoric population, like the broad patterns of their lives, must be understood from their material culture. By ‘material culture’ is meant the buildings and objects of all kinds, from clothing to tools, that they used, but also a variety of things such as cooking refuse, tattoos, murals, and earrings. It is the way in which they created and used their material culture that articulated their relationship with one another and their environment. Words and thoughts, work and patterns of life, all exist as material culture–as the archaeological finds of a once living people’s material culture.

In the present context, it is people’s work in creating and maintaining a cultivated landscape that is paramount. For the period before 1000 BC this landscape survives in countless traces, barely distinguishable to the untrained eye. From archaeological excavation sites and from geological samples there is the evidence of pollen grains, pieces of bone, charred seeds, and other remains from the prehistoric landscape’s flora and fauna. These are small fragments of our picture of the prehistoric landscape and prehistoric people’s relationship to the landscape.

Archaeology’s mute source material creates silent archaeological people. This has both its limitations and its opportunities compared with the study of written history, although in this chapter it is the advantages that are more in evidence. However, it is not merely the nature of the source material that makes the people appear different from us. They were different. Prehistoric people had very different types of house and clothing than we do now, organized themselves as communities differently, and supported themselves in different ways. They spoke languages that would be unintelligible to us, thought in different ways, and had different emotions. As people they were both similar to us and different from us, and they would be as incomprehensible to us as we would be to them should we chance to meet.

Prehistoric people can be labelled ‘pre-industrial’, ‘pre-scientific’, and ‘primitive’; the latter meaning that they approached very different circumstances from our own with a different kind of logic. Yet it is the very profundity of these differences that mean it is more interesting to approach the people of the Stone Age and Bronze Age by taking our lead from present-day, non-Western societies in Australia and Africa, rather than by attempting to draw a line from recent peasant societies in Scandinavia back in time through the Middle Ages to the Iron Age. In capturing the different ways of life in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, I will not build on explicit ethnographical analogies, neither on ethnographical–historical comparisons, but rather on the archaeological finds. The comparisons hover in the background, of course, impossible to ignore completely: the words to describe what we find cannot be pulled out of thin air.

In archaeological agrarian history, change is viewed in terms of the immensely long perspective of the prehistoric period; yet if at the same time prehistoric societies are thought of as fundamentally different to our own, this becomes problematic. After all, the central question remains how and why change occurred. How are we to know which changes were important, or what the causes of change might have been, in societies that are so hard for us to understand? This is one of archaeology’s paradoxes, and one that the reader would do well to bear in mind over the following pages, and particularly in this chapter’s conclusions, which range over the first three thousand years of Scandinavian agriculture. There is no simple way around the paradox.2

The European background

From 5500 to 5000 BC, agricultural settlements were built across the central European continent from the Ukraine in the east to France in the west. Similar houses, graves, objects, and ways of life go by the name of Linearbandkeramik kultur (Linear Band Pottery Culture, or LBK), and are found in the region of the Baltic’s southern coastline by 5000 BC. The seashore was home to the hunter-gatherers. In the LBK settlements, long-houses were built with slanted roofs supported on posts that were sunk in postholes. Each of these long-houses was the equivalent of a household, perhaps a constellation better described as an extended family than as a nuclear family. In this way the tradition was established in northern Europe of long-house farms and long-house settlements that was to last thousands of years, spanning the Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and only fading in the historical period with the shift to family-based agriculture accommodated in other kinds of house. But for now the long-house and the household were one and the same.

Southern and central Scandinavia was part of this northern European long-house tradition. Starting in around 3900 BC, the first Scandinavian long-houses were built to house agricultural households. They have been found in Denmark in the south up to central Sweden and the region around Lake Mälaren. Much of what follows centres on the long-house farms’ households. The geographical perspective is the artificial one of the modern state of Sweden. For the Stone Age and Bronze Age this imposes arbitrary geographical distinctions, but it does offer an interesting ecological gradient. The southernmost part of the country, the plains of Skåne and Halland, is a continuation of the European plains, and from there the gradient stretches as far north as central Italy is to the south–through a landscape of primary rock, marked by glaciation and land-upheaval, to the snow-covered fields of Lapland.3

Complex change

The spread of agriculture to new regions is sometimes said to conform to a three-step process:4

(i) Availability. Agriculture is known to the people of the region, but they do not cultivate the land themselves.

(ii) Substitution. Agriculture makes noticeable inroads into the subsistence economy.

(iii) Consolidation. Agriculture becomes the dominant source of food and other necessities.

The first of agriculture’s ecofacts–charred grain and the bones of domesticated animals–are found together with Funnel-Beaker pottery, and thus the rise of Funnel-Beaker Culture marked the advent of substitution, the second stage. The first stage had by then lasted at least a thousand years, with its associated archaeological culture named for Ertebølle, an archaeological site in Jutland, of which there are finds in Sweden in Skåne, Blekinge, and southern Halland. Ertebølle Culture ceramics were fired at lower temperatures, have thicker walls, and are less varied in shape and more sparsely decorated than the pottery of Funnel-Beaker Culture. The two kinds of ceramic can be used to distinguish between older and more recent modes of life during the pivotal period of 4000–3800 BC. Equivalent changes had taken place in northern Poland and Germany some 500–600 years before.

There are two schools of thought on how the two pottery styles and ways of life succeeded one another over time. By contrasting the detailed dating of sites where only Ertebølle ceramics are found with those with only Funnel-Beaker ceramics, it seems that the former existed until 3800 BC, while deposits of the latter began in 3900 BC. One lifestyle might very well have replaced the other in less than 50–100 years; a matter of two or three generations of people taking a vital decision. Yet equally, sites where both kinds of pottery have been found can be used to argue that they were in use at the same time, at which point, instead of a sudden break, the change in lifestyle appears as a process that spanned up to ten or twelve generations over the course of 250–300 years. The chronological problems remain to be solved.

The greatest problem faces those who advocate the latter view, for it requires that the people of the older lifestyle lived generation after generation knowing of agriculture but not adopting it. Are agricultural ecofacts ever found in conjunction with Ertebølle Culture finds? Actually, the answer is yes, for three Ertebølle potsherds from Skåne show the impressions of grain. All three were found together with Funnel-Beaker potsherds, but it is not possible to determine whether the Ertebølle potsherds ended up in the refuse before or after the first Funnel-Beaker potsherds, although at the problematic site of Siretorp in Blekinge it has been established with a reasonable degree of certainty that the place was used by turns by people who used Ertebølle pottery and people who used Funnel-Beaker pottery.

The introduction of agriculture to the southernmost areas of the Scandinavian peninsula appears as a complex and as yet poorly understood process. Over the course of several generations, people adopted very new ideas and to varying extents changed their way of life. In central Sweden the process was apparently more straightforward. Archaeological finds of Funnel-Beaker artefacts and of cultivated plant and domestic animal ecofacts have been made in exactly the same terrain as finds from the older fisher–hunter–gatherer tradition. The contrast in material culture, ritual, and lifestyle is immense, and it certainly confuses the issue of whether people from southern Sweden did indeed move to central Sweden, taking with them not only their aspirations but also their domestic animals and seed-corn. A chronological difference between the earliest dates for Funnel-Beaker Culture in Skåne and in central Sweden cannot be proved, however.

From the composition of finds of ecofacts it would seem that agriculture in the period 1200–800 BC was the wholly dominant way of life as far north as present-day Västergötland and Uppland. Perhaps this had also been true around 2000 BC, but there is insufficient evidence both there and in the areas to the west and north of Lake Vänern. In limited areas of the country, agriculture dominated earlier than this. Further, it should not be thought that agriculture was introduced simultaneously to a large area, let alone to the country as a whole, whereupon it grew gradually in importance. The availability–substitution–consolidation model is a simplification of a reality that is hard to grasp, and in many ways it is more fruitful to consider a different three-stage model of non-linear change.

Agriculture was introduced in 3900 BC in southern Sweden, as far north as Bohuslän, Västergötland, Närke, Västmanland, and Uppland, and possibly even up to Dalsland and southern Värmland. In form it was relatively similar across the entire region, although with a degree of ecological variation from south to north in terms of the choice of plants cultivated and, more indistinctly, the kind of livestock kept: wheat was more common in the south, barley in the north; and it is possible that sheep and goats were more usual in the north, unlike the south, where cattle and swine dominated.

After 3300 BC, during the Middle Neolithic, the variations across the agricultural areas of southern Sweden were no longer determined by ecology, but by culture. A variety of archaeological cultures, which in muted fashion equated to people’s various lifestyles, was linked to a variety of kinds of agriculture, with different choices of plants and domesticated animals. In the Funnel-Beaker Culture, wheat and cattle predominated; in the Battle-Axe Culture they grew barley, and possibly kept more sheep and goats than cattle; while in the Pitted Ware Culture, agriculture played a less important role, but they still had herds of pigs. Agriculture did not grow in importance, except in the plains; what it did do was change.

Then in the Late Bronze Age, from 1100 BC, agriculture once again became similar across the entire region from Skåne to Uppland, although at a guess the levelling out of cultural differences had already begun during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, starting in 2300 BC. The same plants were cultivated and the same animals kept, with only a few small differences between southern and central Sweden. Hunting and fishing diminished in importance as a source of food.

When it came to agriculture, the boundary that ran across the country that may have been established as long ago as the Early Neolithic seems to have remained in place for the entire period up to and including the Late Bronze Age. The cultivation of barley, but not cattle, has been demonstrated for the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia from the Middle Neolithic. If the conventional model of the introduction of agriculture is applied to the large region north of Uppland, the first step, availability, cannot be said to have ended until 1500–1000 BC, and perhaps even later. This was at least three thousand years later than in Skåne or Västmanland.5

Changes to farms

Between the Early Neolithic and the Late Bronze Age, the composition of farms changed in ways that become understandable if they are seen relative to the long-term changes in agriculture summarized in the previous section. The term gård (farm) is a problematic and probably anachronistic term used in prehistoric archaeology. A farm is a piece of ground that has been settled. It is also a group of people, in historical time often centred on a married couple, a nuclear family, or another female–male relationship. The group is independent and self-sufficient. All this being so, it is reasonable to regard a farm as a household.

In written history, farms are associated with estates, leases, taxes, obligations, and rights; for the prehistoric period, it must be the facts on the ground–the houses and agriculture–that determine how the term ‘farm’ should be used, if at all. A Pitted Ware Culture hut with a group of people tending a herd of pigs does not at first glance seem to be a farm. A Late Bronze Age long-house, possibly with an in-built byre as well as outbuildings, fields, and livestock, does.

The term ‘farm’ is used here for the Neolithic and Bronze Age to mean a dwelling-house for a group of people for whom agriculture provided a significant part of their livelihood. To qualify, the house must be substantial–a long-house, for example –and the agriculture of sufficient importance that it is a part of the fully agricultural lifestyle discussed in the section on the agricultural mindset (see p. 32). This is couched in deliberately vague terms in order to capture the considerable variations that existed during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. With this approach, the term prehistoric ‘farm’ signifies something very different to the farms later in this book.

During the Early Neolithic and Early Middle Neolithic, farms generally consisted of a single house, 8–18 metres long. During the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, farms also consisted of only one house, but it could be double the size, 8–35 metres long. The difference arose from the fact that the kind of agriculture that was not complemented with hunting, fishing, and gathering on a large scale had been established during the Late Neolithic, during what in the three-step model would be consolidation. Agriculture is amongst many things a storage economy, with a pressing need for space to store produce, while fishing, hunting, and gathering are the embodiment of a hand-to-mouth economy. Instead of having different houses in different places for different activities, the households of the Late Neolithic gathered all their activities in a single place–the farm. In the Late Bronze Age, farms had at least two different buildings–a long-house and an outbuilding–and thus several smaller buildings for different purposes replaced a single large one. These long-houses were 9–22 metres long.

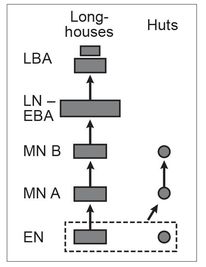

Figure 1.1 It is possible to chart a long-house tradition from the Early Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age. In the Early Neolithic, households moved seasonally between long-houses and huts. In the Middle Neolithic, Pitted Ware Culture ceramics found in conjunction with huts form a distinct tradition. In the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age the long-houses were larger, while in the Late Bronze Age outbuildings were more common than before. (For abbreviations, see Fig. 1.5.) Source: Welinder 1998, for this and all other figures in this chapter.

Fig. 1.1 illustrates in simple form the considerable variation within periods and between different parts of the country. To explain why the farms changed in appearance, it is not enough simply to adduce the functional changes in agriculture.6 With the passage of the first millennia of agriculture, small long-houses that were moved around coppiced woodland gave way to larger long-houses, complete with outbuildings, each sited in an enclosure in an open agricultural plain; small fields cleared with mattocks or by rooting pigs, sown with digging-sticks, gave way to cleared, manured, and bounded fields that were ard-ploughed and sown several years in succession; livestock that roamed the coppiced woodlands day and night, year round, gave way to livestock kept in byres and driven considerable distances to summer pastures.

This picture is more a good guess at how life was lived than a certainty: in places the archaeological evidence is barely sufficient to support it; it is to some extent based on cultural studies and our present understanding of ecology; and in many respects it only holds good for limited areas of the country. It is also freighted with a sense of purposeful development, as well it might in a description of farms and cultivated landscapes that spans three thousand years. The evolutionary element in this picture is real, at least to the extent that each period set the preconditions for the next, but it would be wrong to think that people created their way of life not in response to these preconditions, but to how things might turn out subsequently. Still, it is accurate to say that agriculture and the agrarian landscape changed. What then of the agriculturalists?7

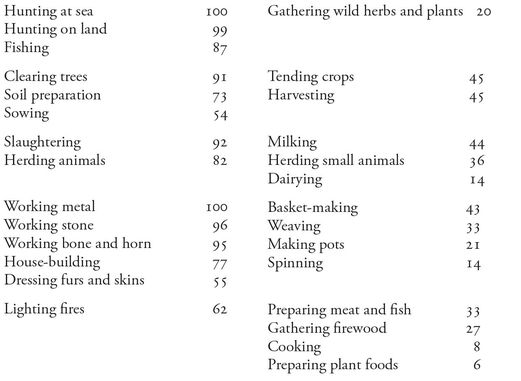

Figure 1.2 A gender index for various household tasks. A value of a hundred means the work was exclusively male, a value of zero means it was exclusively female. An intermediate value means it was done to a varying degree by both men and women. The figures are based on a study of a large number of ethnographical descriptions of different population groups in various parts of the world (after Murdock & Provost 1973).

All farmers are in some respects similar. The ecology of the people and the cultivated landscape remains the same. People, however, are individuals, with feelings and ideas–and groups who adhere to norms and traditions. This is what makes people, people; this is why they must be understood as culture. This is in effect to say that all people are different, yet the emphasis here is on how people in the Neolithic and Bronze Age were very different from modern people, and I will not be placing as much weight on the variations over the three thousand years under consideration.

The crucial element in all this is the household: how it functioned, and why it functioned. When it came to the why and the wherefore, prehistoric people had their own ideas. Of course, they had their own ideas about everything else as well, but here the focus will be on prehistoric views on the household, and more particularly on how the differences between them and us can be better understood if we try to see how prehistoric people explained the course of agriculture and the continuance of the world.

The household

Farm, long-house, and household are terms I use more or less interchangeably. Farms and households were groups of people who cooperated in order to live; the people who formed a household lived together in the same long-house, and survived by their joint efforts. Each household was a farm, and was sustained by it for several generations, through a progression of births and deaths. It seems probable that a household consisted of people drawn from three generations: adults, and their parents and children. Yet this is still little more than conjecture, and exactly how the adults were related to one another is still unknown. Archaeological households have a tendency to be houses with stubbornly anonymous inhabitants.

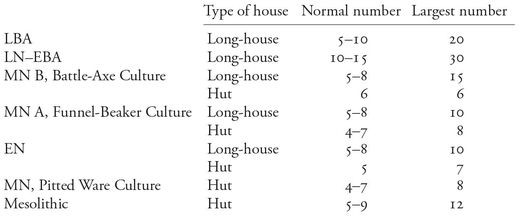

Since the members of a farm household lived under the same roof, the size of the houses can tell us something of the size of the households. The usual method is to assign each person a certain amount of floor-space based on the formulas arrived at in ethnographical research. Thus in small, single-family houses with a floor area of up to 15 m2 each person is said to have 2–2.5 m2 of space; for floor areas of 15–35 m2 each person has 10 m2; while for large houses over 35 m2 the calculation is based on 6–10 m2 per person. For the prehistoric period, the first formula can be used for huts and the smallest long-houses, the second for the larger long-houses. Mesolithic huts before the advent of agriculture by this reckoning housed 10–12 people. In the Middle Mesolithic, huts were generally somewhat smaller, both in the Pitted Ware Culture and in the hunting and fishing grounds of the Funnel-Beaker Culture and the Battle-Axe Culture–places where people did not live in long-houses, in other words.

The long-houses of the Early and Middle Neolithic were relatively small, and after a period when they were somewhat larger in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, they were once again small in the Late Bronze Age. A household in the Early or Middle Neolithic seems to have consisted of six or seven people, and it is uncertain whether their number grew at the start of the Late Neolithic as the increase in long-house size might at first glance indicate, for the simple reason that the new kind of agriculture brought with it tasks that required more space indoors. Similarly, it is equally uncertain whether the households shrank in size during the Late Bronze Age compared with the Early Bronze Age, since some of the larger long-houses’ functions moved out into outbuildings. It would seem that throughout the entire Neolithic and Bronze Age, a normal household consisted of some six or seven persons. This conclusion is problematic, and particularly for the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age the possibility must be entertained that households were in fact larger.

Figure 1.3 The estimated number of inhabitants of different kinds of house in the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age.

In the Early Middle Neolithic, passage-graves were built by households in several regions; in the Late Middle Neolithic, the people of the Battle-Axe Culture buried their dead singly in rows; in some parts of Sweden in the Late Neolithic, each household had its own chambered tomb; while in the Early Bronze Age, groups of mounds were constructed in the south of the country, and cairns in the north on the high ground above the farms. Yet in all this it is unclear how the graves should be related to individual farms and households, or whether all the members of a household were buried in the funerary monuments that are still very much in evidence. The latter was probably the case with grave-fields with single burials in earthenware pots or birch-bark containers in small pits in the Late Bronze Age.

For all periods, however, there are graves for both women and men, for both children and adults. Men’s graves generally occur more frequently than women’s graves, while children’s graves are far more rare than might be expected from what in all likelihood was a high rate of infant mortality. There is much to suggest that not all members of a household were buried in the readily visible monuments. However, indications are that the households were made up of a core group of adult women and men.

Starting with the normal sizes for the households outlined above, they seem to have consisted of some two or three adult women, a similar number of adult men, and between two and four children. A three-generation family with one or more extra people is one possible interpretation, even though it should be borne in mind that it is not self-evident that nuclear families existed in the Stone Age. Whichever the case, the households were built up around a community of work that transcended the boundaries of gender and age.

The shift from larger to smaller long-houses in about 1000 BC has largely been discussed with a view to understanding household structure. The rich archaeological site at Apalle in Uppland offers the opportunity to test some of these ideas. Here, a number of farms and households existed concurrently for several generations. Before 900 BC, the households cooked their food in large cooking pits, and disposed of their refuse in communal mounds of fire-cracked stones. After 900 BC, they all cooked their food indoors and each household had its own refuse heap. Individual households became more distinct, and more private. At the same time, from having primarily grown emmer wheat, they went over to growing hulled barley. Manured and ard-ploughed fields for hulled barley were a long-term investment, one for which it would be an advantage for a farm to assert private ownership. It could be that the period around 900 BC saw the introduction of what in time would become the family-owned farms of the historical period.

The division of labour

Rather than a community of work, it is more usual to talk of the division of labour, by which is meant the allocation by gender of different tasks within the household. Women and men complemented one another. A compilation of ethnographical data from many different societies aside from Western, urban, industrial culture shows that the division of labour follows certain general patterns: hunting and fishing is for men, gathering is for women; the cultivation of the land is men’s work from tree clearance to sowing, and then women’s up to the harvest; men tend the herds of cattle and slaughter them when the moment comes, women care for smaller animals, the milking, and the dairying; men build houses and work with hard materials and hides, the women with soft materials such as wool, osier, bast, and clay; women cook over fires of wood they have gathered, but that have been lit by men. The variations are considerable, however, and this pattern should not be thought of as a set of hard and fast rules, but with that in mind it can still be interesting to refer to them when studying archaeological sites.

The archaeological method for studying the division of labour by gender is to correlate tools found in single graves with sex-determined skeletal remains. Sex-determined skeletons in individual graves have been found from the Battle-Axe Culture of the Late Middle Neolithic and in graves with cremated skeletons from the Late Bronze Age, but otherwise there are few opportunities to relate tools to sex-determined individuals. Tools have also been found in graves where, although the gender of the remains cannot be determined, there are gender-characteristic objects such as men’s swords and women’s bronze-trimmed cord skirts in the Bronze Age, or men’s battle-axes in the Battle-Axe Culture of the Late Middle Neolithic.

Some of the agricultural work can be gender-determined with the help of the tools found in graves. Soil preparation, according to the ethnographical pattern, is men’s work. Sure enough, horn hoes, which were perhaps both digging-sticks and mattocks, were in the Battle-Axe Culture only placed in men’s graves. Similarly, all the surviving petroglyphs of ard-ploughing show men behind the ards. Sickles are one of the more usual grave-goods. In the Late Middle Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, they were for the most part placed in men’s graves, yet by the Late Bronze Age they were just as likely to be placed in women’s graves as men’s. The conclusion is that periodically the harvest was predominantly male work, while in other periods it was a joint effort by women and men; yet the question remains whether grave-goods really lend themselves to so uncomplicated a reading. One sickle was found in the grave of a 9- or 10-year-old child. In many low-technology agricultural societies, children take part in the daily work on the farm, starting with simpler tasks from the age of five or so, and gradually growing into an adult role. Whether this was true of Scandinavia in the Neolithic and Bronze Age is unknown.

The bones of cattle are only found in men’s graves from the Late Middle Neolithic and Late Bronze Age, and the same is true of sheep and goat bones in the Late Middle Neolithic, yet sheep and goats are the only domesticated animals to be found in women’s graves from the Late Bronze Age. These findings point in the same direction as the ethnographical findings. Cattle were men’s business in the Late Middle Neolithic, and come the Late Bronze Age this was still the case, whereas sheep and goats were women’s work. In a Late Bronze Age grave, an earthenware strainer for cheese-making was found with a piece of neck-ring, perhaps indicating that it was a woman’s grave. It should be noted that, though in all ages and places corn has invariably been ground by the women of the household, or in some societies by slaves, the archaeological remains have nothing to say on the matter.

The ethnographical patterns, together with the limited and problematic evidence of grave-goods, give a picture of men who worked the fields and tended the cattle, and women who worked closer to the house and with food. This is perhaps not surprising, but it is a picture that lacks variation and nuance. The discussion continues.8

Thinking agriculturally

Agriculture is in essence the re-creation of the fundamentals of life. Likewise, it is a constant cycle of repetitions. The business of agriculture –the work, and how that work is shared–is ultimately to preserve life and society. In agricultural societies in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, agriculture shaped society and individual patterns of life–and ideologies.

All these societies were illiterate. Their own history and sense of community resided in stories: tales and myths about the origins of humankind, about how people were given agriculture, and about why agriculture, life, and the world prevailed; but also stories in the form of ritualized actions, of sacrifice, cult, and ceremony, the visible stories that by constant repetition ensured that the world would endure. Agriculture belonged to the world of ideas that made life comprehensible to the people of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, and that equipped them to ensure that it would continue in like fashion. Something of this vision can be found in the archaeological remains.

Tales or myths existed to explain the course of life; why year after year the fields yielded harvests and the livestock bore calves, kids, and piglets. Agriculture was not production; it was reproduction. Life was continuously to be recreated. Time revolved. The rhythm of each day and the course of the year was set by sowing and harvest, procreation and birth, and time told equally on agriculture’s people, who were born and died, generation after generation. In their mind’s eye, all was continuous repetition. Change was a striving to remain the same, a striving to guarantee the march of time and life itself. Agriculture’s people in the Neolithic and Bronze Age had to explain the passage of days, years, and life–the constant re-creation of the fundamentals of life–and safeguard the circumvolution of time and existence.

In this perspective the thousands of flint and bronze sickles from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age found far and wide in today’s farming districts become more explicable. They were placed singly or in groups. Several revealing sites show that the sickles were placed vertically or were stacked much like roof-tiles, and at one they were found wrapped in birch bark. The general similarity between all the sites is striking.

Burying sickles in the ground was like sowing corn, for from them would grow the life that would be harvested–with sickles. Sacrifices or magical performances made up the rituals that surrounded sowing and harvest, and the placing of sickles in the ground was part of the yearly cycle, as much an explanation of the mysteries of seed and harvest as were the myths, cult ceremonies, and work; and while there was a time and place for each, yet they remained the same, time and time again.

The basis of re-creation in agriculture is fertility, and the basis for fertility is the encounter between female and male. Sexuality, fertility, and reproduction are the foundations of life, agriculture, and society. In the agricultural societies of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, it was within the ambit of the household that female and male came together; within a household shaped by the division of labour in which male and female met and complemented each other, and so safeguarded the reproduction of the household, society, and life itself. The world would live on as long as the animals, the fields, and the household were fruitful. This for them was the self-evident reason why agriculture worked, and had to work. At the same time it was infinitely complicated, for how to explain, and how to ensure, continuous re-creation?

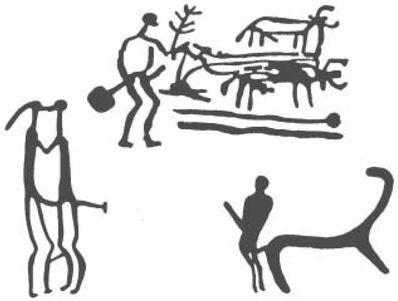

The petroglyphs show the sexuality between women and men, but also between fields and men, and between men and animals. It is of less importance whether these are depictions of actual Bronze Age cult ceremonies, or whether they are illustrations of myths of gods and heroes creating and recreating the world through sexuality. What they do show are people’s thoughts on sexuality and fertility, on how female and male meet and recreate life. It is not a stretch to read the petroglyphs as showing that it is the male element that embodies action, while the female element–fields, livestock, and the women–passively receives life. After all, agricultural tools are much more in evidence in men’s graves than in women’s. It is here that issues such as gender roles, prestige, and status enter the picture.

Ritual

Of all the recurrent actions of a ritual nature, those that are most readily visible are sacrifices. For the Neolithic alone there are some 1,300 known sacrificial sites in Skåne, and the numbers for the entire country and for the Bronze Age are unknown. Sacrificial sites exist throughout the country, wherever there was agriculture in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. The sacrificial offerings were placed at the fringes of wetlands, on the bottom of streams and rivers, in damp hollows, beside large rocks. The sacrificial sites were equipped with narrow walkways, wooden piles, and platforms of logs or branches that made it possible to walk out into the wetland and place the objects, often fully visible on the surface of the peatbogs or in shallow water. Animal bones, charcoal, and the burnt remains of wooden objects, human bones, and skulls are a sign that there were ceremonies and festivities, not merely an unadorned sacrifice. At other, dryer locations the sites were made to stand out by framing them with palisades, ditches, or stone walls.

The sacrificial sites from the early part of the Early Neolithic period contain single objects, at most a handful; the remains, it seems, of a single farm’s offerings, placed over the course of one or two generations, before the farm was moved and a new wetland was selected for its sacrifices. Starting in the Late Early Neolithic, sacrificial sites began to appear that were to have numerous objects placed in them over the course of hundreds or even thousands of years, a number of which sites seem to have been shared by several farms.

The custom of making sacrifices in wetlands remained fairly constant throughout the Neolithic and Bronze Age; it was the objects sacrificed that varied. During the Early and Middle Neolithic, the sacrifice of choice was an axe; in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, sickles were more usual. The axes chime with the ring-barked and pollarded trees in the coppiced woodlands that were the basis of agriculture in the Early and Middle Neolithic; the sickles with the harvesting of fields of grain and the gathering of fodder for farms with the storage space of the large long-houses of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.

Sacrifices were also made on the farms themselves, close to the long-houses. In the Early and Middle Neolithic, offerings were placed in pits, often after the objects had been burnt. In the Late Neolithic it became customary to place the offerings inside the long-houses, in the holes for the corner-posts and the posts holding up the roof. In one posthole in a house found at the archaeological site at Fosie in Skåne was a flint sickle; at Västra Skrävlinge, also in Skåne, a posthole contained three flint axes arranged in a triangle with the blades uppermost, with a fourth axe laid across the top.

The changes in sacrificial customs in the Late Neolithic indicate that the households’ ideas about agriculture, life, the annual cycle, and the world’s continued existence now more than before centred on the long-house and the household, the harvest and livestock. This is even more apparent in the Bronze Age, when images of people, livestock, and sexuality were chipped into the rock faces. At Apalle in Uppland the jawbones and skulls of domestic animals were found arranged along the walls of long-houses from the Late Bronze Age, the various kinds laid in different places along the walls or at the thresholds of different rooms. Here people lived and worked surrounded by the heads of their slaughtered animals. Where refuse was collected in mounds of fire-cracked stones, a circle of cow, bull, horse, pig, sheep, and goat skulls was carefully arranged around the foot of the heap, while the cooked and split marrow bones were thrown on it. Livestock were tended, fed, milked, slaughtered, depicted in petroglyphs, and placed in the farm’s buildings and around its enclosure in ritualized patterns; alive and dead, they were a constant presence in people’s lives and thoughts. They were work, food, and myth. Above all, they were the constant re-creation of life, and thus also of death.

Life and death

Agriculture is life, but by the same token, it is death. It is also a metaphor of life and death. However, it is not death as annihilation. Instead, it is death as cessation, part of the constant, seasonal round of sowing–harvest–seed-corn, sowing–harvest–seed-corn. The rhythm of each day or year, even of human life, is one of re-creation and return.

Figure 1.4 The Bronze Age world of ideas, carved in rock? Arable land, livestock, and life itself created in the union of male and female. Petroglyphs (rockcarvings) from Sten-backen and Vitlycke, Bohuslän and Sagaholm, Småland.

Occasionally, there are ard marks under Early Bronze Age burial-mounds in Skåne and Halland. Whether the ground was ritually ploughed because a burial-mound was about to be erected there, or whether the burial-mound was placed in a field that had sustained the dead during their lifetime is a moot point. The burial-mound itself was made from turf from the pastures that gave the livestock life; it rested on and contained agriculture as death and life. Sometimes sickles were placed in the burial-mounds, or quernstones at the outer edges of the mounds or amongst the stones in the barrow itself. At a site at Östra Vrå in Södermanland from the Late Early Neolithic, some eighty quernstones were placed over two pits containing dead children. As we have seen, grave-goods are often used as an indication of the occupations of the dead during the deceased’s lifetime. This may be an accurate assumption, but it may equally be the case that the tools were meant as a reminder of death’s place in the cycle of life.

The drama of life and death was played out within the household, where female and male met in a community of work and in sexuality. The household was the long-house; it was the food cooked over fires in the cooking pits outside or at the hearth inside. Prehistoric people thought in associative patterns, in objects and actions. Life and death, the long-house and the hearth; all were crystallized in the mortuary house, the house built for the dead in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. In the mortuary house at Turinge in Södermanland, which dates from the Late Middle Neolithic, cremated human remains were found in the wall foundations, along with earthenware pots, animal bones, and axes. It all gives an intentional picture of the complex ideas about life, death, hearth and home, fire, harvest, and food in the Battle-Axe Culture.

Fire was the very essence of life. It meant a warm long-house in winter, and cooked food, and the fired earthenware pots to contain it. In the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age, the shattered stones from the hearths and from cooking and brewing were collected outside the long-houses in mounds of fire-cracked stones, with the general household refuse and waste from the slaughter, leaving for posterity a picture of the household and the fire, and therefore of life and the re-creation of life. Beginning in the Later Bronze Age it became usual to cremate the dead. Sometimes the remains were buried in the mounds of fire-cracked stones, but more often the bones were placed in one of the household’s earthenware pots, occasionally even a pot shaped like a house. The barrows where the earthenware pots have been found look the same as the fields’ clearance cairns. When a long-house was moved to a new location, its refuse was ploughed into the fields.

Life and death, long-houses and graves, households and agriculture –all were interwoven at these archaeological sites, an extension of how people thought about the existence and re-creation of everything around them, about the course of time, and about the encounter of female and male in the sphere of the household.

Households were not only groups of people who created, stored, and prepared food together. They also ate as a group. In the Late Early Neolithic and the Early Middle Neolithic, earthenware pots containing food were placed out in wetlands; in the Early Middle Neolithic, they were placed at the thresholds to the dolmens and passage-graves where the bones of the dead lay piled up in the house-like stone rooms; in the Late Bronze Age, wooden vessels and earthenware pots of grain and other food were placed in the stone-walled chamber on a hilltop above Odensala Prästgård in Uppland. The food in all these offerings was a gift from the people to the gods or the powers. Conversely, all food was a gift from the gods or powers to people.

Food was a priority in the household, and between the household and the gods or powers. To take a meal together was a religious act, and a moment when people came together. The attitudes towards the division of labour and ritualized gender roles meant that the internally complementary pairing of female–male is all too easily thought of as corresponding to pairings such as inside–outside and passive–active. Yet it was women who organized, prepared, and shared out the food, and it was women who thus gave the gift of food within the household. Expressed as simple opposites, passive–active could be replaced by give–do: women give–men do. Women were the nexus, for not only did they literally give life, they sustained life with the gift of food. Farming was a means to an end–food–and the shared meal is the essence of agriculture.

The rituals of agriculture

UNTIL THE BEGINNING of the twentieth century, to farm the land and raise livestock was to bring order to the rhythm of the days, the turning of the years, the cycle of life, to crops, animals, and the household, using implements and experience – and rituals. The early farming households in the long-houses of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, 3000–500 BC, created a ritualized pattern of life that assured them the continuation of life, acting in concert with the relevant powers. In the larger, more hierarchical societies of the Iron Age, 500 BC–AD 1000, households used the same traditional rituals and added new ones, which in part had been created in response, and opposition, to the Roman Empire.

Returning mercenaries from the Roman army baked bread from flour that had been ground in rotary querns, a novelty in the German societies of the third century AD. The querns produced the bread of life by turning, like the day and the year; turning on an axle that stood upright like the celestial axis. At first, bread was prestige and cosmology. It was to be found on the great men’s farms, at cult sites, and in men’s graves. Great men and chieftains built halls that imitated the audience chambers of the Roman emperors and officials. Small gold-foil plaques were fastened on the roof-posts and placed in the postholes; tokens stamped with mythical images of the chieftain-couple in life-giving embrace, an assurance to all the chieftain’s followers of good harvests and continued life.

The agricultural areas of present-day Sweden were Christianized in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Much of the household’s ruminations and ritual actions as to daily life and farming were moved from farm, settlement, burial ground, and land to the church, the mass, and the churchyard. Much of life continued as before. Coins, earthenware pots, and animal remains were deposited under the houses as they were built, but now to an ever-increasing degree inside the houses, not under the walls or the threshold. They were intended to keep the good inside the house, no longer to shut out the bad. Household utensils and farming implements were thrown into Västannortjärn, a lake in Dalarna, between AD 1100 and 1400 in a manner reminiscent of another sacrificial site, Käringsjön in Halland, between AD 200 and 400. Was it a similar expression of the same idea of sacrificing to the powers that bestowed on the household and farming year their unbroken order, or was the same expression found for very different ideas by accident? When the relics of St Erik were translated from the old cathedral in Gamla Uppsala to the new in Uppsala in the thirteenth century, the reliquary was carried in procession across the fields in the same way that the goddess Nerthus, as Tacitus noted in Germania in AD 98, rode in her wagon through the countryside spreading fertility.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, one of the girls who had helped shovel the manure from the farm’s dung pit was tossed onto the last cartload being carried to the fields. She was the Dung Bride, and the cart was driven by the Dung King. In the dung pit stood a maypole, similar to the maypoles raised to this day for Midsummer. At Midsummer, the May Lord fought winter and, victorious, ushered in the new farming year with the May Bride at his side. The manured fields were sown, usually by men, with long, powerful strides so that the corn would grow tall and strong. Flax, which they wanted to grow tall, was sown on days with women’s names, because women had long hair. At sowing-time, the Christmas bread, which had been waiting buried in the seed-bin, was crumbled into the seblet with the seed-corn, now a ‘seblet-cake’ that carried the hope of the one harvest to the next. Seblet-cake could also be given to the horses, buried in the fields, or eaten by the labourers on festive occasions. It was made from a sheaf that had been heavily bound in order to make the next harvest abundant. The kneading-trough would be covered with a pair of man’s trousers, in the same way as a woman’s petticoat was put on the threshold when a new cow was to enter the byre for the first time.

On many farms the traditional rituals were kept alive, from force of habit and for safety’s sake, right up to the middle of the twentieth century. Then general education, secularization, and the changing nature of agriculture finished them off. But even today there will probably be a horseshoe over the door, ends pointing up so the luck cannot run out. At Rösten in Östergötland, a phallic stone that has stood close by the farm there time out of mind is still cared for and painted. It is said that the farm will sink into the ground if not. Once when they forgot to paint the stone, the barn burned to the ground.

And of course, there will always be the mumbled, “If God is willing, and the tools don’t break …”

The eternal household

This timeless picture of the household and gender roles, and of how the division of labour was ritualized and mythologized, takes its starting-point in general human experience and scant archaeological finds, independent of time and place. Properly speaking, the challenge of prehistoric archaeology is to determine whether and when different types of household–and gender role–existed, and how they changed. In this chapter I have instead concentrated on the unchanging similarities.

Life expectancy was short in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. The generations succeeded one another rapidly. Thus it was not lone individuals who held a household together over a long period of time; it was the community of work and the female and male elements within the group of people who made up the household or farm. Agriculture in the Neolithic and Bronze Age existed within a framework of households that are reminiscent of families. That is still very much the case today, even if the later chapters in this volume nuance the history of recent centuries, but thus far I have argued that change, particularly in the course of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, was secondary to continuity. It might be of interest, however, to trace how agriculture came to leave an increasing mark on cult and ritual. Animals or animal parts were regularly buried together with human remains. It was only from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age that domesticated animals dominated this particular form of a special relationship with animals. Indeed, in the long perspective this was the era when ritual actions began to be shaped by agriculture.9

Figure 1.5 The three-step model of the introduction of agriculture to Sweden (see p. 22) reveals the differences in its progress in the southern and central areas of the country.

Change

The three-step model of the introduction of agriculture can be used to describe the different rates at which it was introduced in the various parts of the country. Other similar progressions can be followed over the course of the first thousand years of agriculture: crops and livestock; buildings; tools and work; the cultivated landscape; farms and households; food and people. Yet it is not self-evident that one coherent picture can be created from these many strands, nor that the trends that would prove important in the long term can be singled out. In spite of this, it is worth attempting to summarize how the significant changes in the epoch 3900–800 BC came about, and why. In truth what is most striking is not change, but the lack of change. The entire Neolithic and Bronze Age had something in common that can be summed up in one word: ‘long-house’.

Throughout this period people lived in long-houses. Admittedly not all the people of the Funnel-Beaker Culture did so, nor did any of the Pitted Ware Culture, but for the whole period from the Early Neolithic until the Late Bronze Age there were always some people who lived in long-houses, and from the Late Neolithic most of them did. Before the Early Neolithic, long-houses were unknown. However, long-houses were merely the embodiment of something even more important, as we have seen, for throughout the entire Neolithic and Bronze Age, agriculture was practised by family-sized groups of people; by households. The typical composition and size of these groups may have varied somewhat over time, perhaps particularly during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, but in all essentials they remained the same: they were relatively small groups of people who worked together within a household. The word ‘farm’ is not out of place here.

In the household, labour was divided according to gender, and gender roles had different status and prestige. The basic similarity remained, though, that the household was built up around a community of work. This found its expression in ritual, sacrifice, and myths that centred on the continued survival of agriculture, the household, and the world; on the constant cycle of seasons and life. Something that did change, however, was the number of households in a given place. A study of one very limited area of southern Skåne has calculated that it had 2–3 long-houses in the Early and Middle Neolithic, 8 in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, and 13–18 in the Late Bronze Age.10 Naturally agriculture itself was changed in its very fundamentals, from how the soil was prepared to the food that was cooked.

Between 3900 and 800 BC, much of the woodland was transformed into a man-made landscape reminiscent of parkland, and in the plains into solitary groves in a treeless countryside. This was the result of ring-barking, slash and burn clearance (swidden), and the pressure of grazing –and a series of changes in agricultural techniques. These changes can either be seen as a constant stream of innovations, or as a handful of episodes when a number of innovations were introduced at the same time, bringing even greater changes in their wake. The matter is problematic because of the long time perspective. What is simultaneous when viewed over the course of a millennium? The shortcomings of modern dating techniques are another problem. How to understand things to which individual people and households might have reacted, when the margin of error on how objects are dated is as great as 200–400 years?

Tentatively, three major periods of change can be distinguished in Neolithic and Bronze Age Sweden:

(i) The introduction of agriculture, 4000–3800 BC. In the course of a few generations, the cultivation of grain and the keeping of cattle and pigs spread across the southern part of Sweden. The same period saw the spread of a new way of life associated with the long-house.

(ii) The revolution in secondary products, 3000–1500 BC. This period saw the culmination of many changes, the first appearances of which came at very different times. The result was an Early Bronze Age farm that looked very different and was occupied by a household that functioned in a very different manner when compared to the Late Middle Neolithic. Ards, horses and carts, sheep bred for wool, looms, oats and millet, bronze tools, specialized sickles, and earthenware strainers are amongst the distinguishing features of the new period.

(iii) The advent of historical farms, 1000–800 BC. Over the course of a couple of centuries, farms began to be built with outbuildings, sometimes with byres. They had cleared, permanent, manured fields. The innovations of the previous millennia came together in an effective whole, helped along by iron tools, which were first manufactured at this point.

The new efficiency of agriculture cannot only be identified, it can also be calculated. The net biological production of a given area is the sum of the total growth of plants and animals in one year’s growing season, and to a great extent is made up of the green foliage of trees and herbaceous plants. In the Early Neolithic, a household drew on fifty times as much of this production as did its Mesolithic predecessor. By the Late Bronze Age this figure had doubled again, at the same time as a more productive landscape had been created through human intervention and the effect of domesticated animals.

The increasing efficiency was dependent on forest clearance and the depletion of the existing brown forest soil. The gross productivity of the land, that is to say the sum of growing stems, stalks, twigs, leaves, and herbs, dropped. Greater efficiency also resulted in increases in eluviation, erosion, and sand migration. In the long term, agriculture settled into a vicious circle. Increasingly efficient agriculture wrought changes to the landscape, which in turn forced the pace of agricultural efficiency to feed a growing population. Agricultural production increased, but at the price of ever more work. Production increased per unit land area, but decreased per unit time. The question is whether this picture of the interaction of ecology, population growth, and agricultural techniques can explain why farms and the cultivated landscape changed; why people began to act and think in new ways.

The changes to the climate and soil inherent in glacial–interglacial cycling, combined with a slow but steady increase in population, must be part of any account of why the cultivated landscape altered. Yet though the changes to the climate in around 1000 BC were significant, they cannot be the only explanation. The chronological, geographical, and cultural variations were greater than the ecological variations of the cycle. For a satisfactory explanation, we must look also to other factors.

Similar changes to those in Sweden’s cultivated landscape occurred across the whole of northern Europe. However, is not sufficient to say that people in Scandinavia constantly adapted to a stream of ideas from the continent, often from the south. People were quite capable of knowing about new developments on the continent without implementing them. Agriculture itself is one such example, wool-work another. It is not enough for innovation to spread: it must also win approval and be adopted. The tricky question is thus why there might be a wait of many generations before an innovation was embraced.

One possible explanation can be sought in how people form societies. In the smallest groups of people, in other words in households, individuals took decisions on whether to change their lives without the benefit of a clear impression of climate change, population growth, or the stream of innovations from continental Europe. Theirs was a down-to-earth view of their own and their neighbours’ situation. That was all they had to go on. As was at its clearest in the Neolithic, different kinds of agriculture were associated with different lifestyles, and these in turn have been bracketed as ‘archaeological cultures’, of which the Battle-Axe Culture in the Late Middle Neolithic is an example.

In illiterate societies, people and groups of people in, say, households function by meeting and talking, and by using ritualized actions and recognizable objects, and it was this that bound together the various Neolithic cultures and periods. Small groups of people who wanted to demonstrate their affinity elected to change at the same time and in the same manner, in the process choosing a lifestyle that set them apart from the people from whom they wish to distance themselves. Each of the different lifestyles had its own kind of food, produced by different forms of agriculture, amounting to what seems to have been the characteristic social mechanism of the Neolithic.

In the Bronze Age, people organized themselves into larger groups of households under chiefs and their kin who commanded the farms’ surpluses, and not least their herds of cattle. The surpluses were used by the chiefs to conduct ceremonies, to arrange imposing sacrifices and burials, to hold festivities, and to exchange for prestigious objects. The changes in the Bronze Age occurred in societies where people had varying degrees of influence and power. The ones with the power were also the ones who were most aware of the societies on the continent that if collaborated with could give them access to high-status, unusual bronze objects such as chased bowls and elaborate weapons, and not least to the raw materials with which to make bronze objects.

Changes in the cultivated landscape were necessitated in the long term by ecological changes and population growth. Ideas and a knowledge of societies of different types than their own could be obtained from the stream of news from the continent. Change was in part the result of the agriculturalists’ efforts to unite in overcoming the tribulations of daily life and, in due course, to generate a surplus to be used by those who ruled over them. Where once there were groups of households that collaborated within a framework of tribes and clans, households now divided into those who produced a surplus and those who commanded the same surplus. Land, livestock, and property were held less in common and more by the individual. The cleared fields and stalled cattle of a Bronze Age farm should be seen in this perspective. They embodied a form of agriculture that was no longer the collective concern of all who belonged to the group. The rights and duties of agriculture were now firmly tied to individual farming households, and it is in the remains of the Iron Age cultivated landscape that this is at its most evident.11