CHAPTER 3

Farming and feudalism

1000–1700

As in the other chapters in this volume, so Sweden’s modern borders set the geographical limits of the present analysis. For earlier and later periods this is less problematic than for the period covered by this chapter: in prehistory there were no fixed national borders, which means that all choices are equally valid when selecting a region for archaeological study; in later periods the national borders had stabilized. Not so in this period, when the nation did exist, but not with its present-day borders. For the period treated here the discussion must reflect the political reality that until the seventeenth century the southernmost provinces of what is now Sweden, among them the rich agricultural lands of the province of Skåne, were part of Denmark, while some of the westernmost provinces were held by Norway. There is also the matter of Sweden’s eastern provinces, which comprised what is now Finland, and are omitted from this overview.

One way to describe the effect of these territorial changes is to say that ‘Sweden’ ultimately moved westwards, losing Finland in the east but gaining provinces in the south and west. Shifting borders are a common phenomenon, the result first of the establishment of the European nation-states in the Middle Ages, with their attempts to fix their borders, and thereafter the innumerable wars and peace treaties that eventually led to the more definite borders of eighteenth-century Europe.

Within ‘Sweden’ itself, the landskap (provinces) are a deep-rooted historical constant. They were formed when the Swedish state was established in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and though they have not been administrative units since the seventeenth century, Swedes still talk about themselves as coming from ‘Västergötland’ or ‘Småland’.

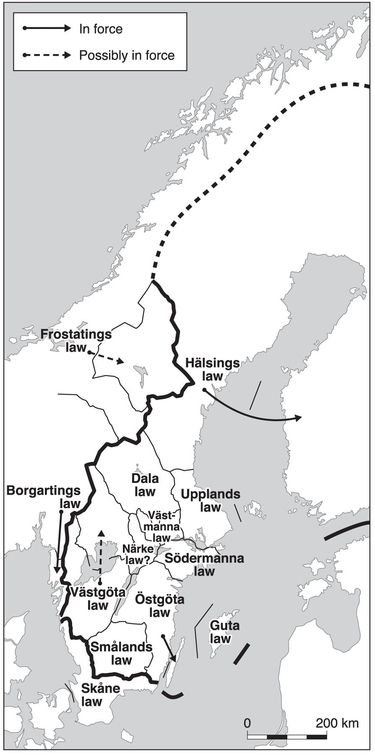

Figure 3.1 Medieval legal jurisdictions and regional laws. The arrows show their scope in about 1300. It is not certain that Västgöta law was in force in Värmland, which may have had its own law, now lost. Närke probably had its own law. Source: Myrdal 1999, for this and all other figures in this chapter.

New sources for a new era

Where prehistory differs from history is in its source material, for it is only with the survival of written sources that individual people and events become visible to us. The fact that the boundary between prehistory and the Middle Ages is drawn in the eleventh century in Scandinavia, later than in much of continental Europe, is a reflection of the lack of written sources before then (rune-stones excepted). The first written sources, on parchment, are from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, while it is only from the thirteenth century that written records survive in any quantity. Instead, archaeological remains, along with a relatively plentiful visual record, are crucial to our knowledge of agrarian conditions in the Middle Ages.1

One theme in this chapter is that Sweden was a part of Europe, one on the fringe but likewise included in the larger whole. The periodization chosen here is thus designed to help the reader to draw comparisons with the rest of Europe. Thus there is no ‘Early Middle Ages’ in this book. Instead, the ‘late Iron Age’ and the ‘Viking Age’ (c. 500–1000) are followed immediately by the ‘High Middle Ages’ (c. 1000–1350), while the subsequent periods are the ‘Late Middle Ages’ (c. 1350–1500) and then the ‘early modern period’ (c. 1500–1700).

A short presentation of the most important sources will give an indication of what is available. Amongst the most significant written sources are the short documents called charters (brev or diplom), which in the main are records of land and landownership. They survive in their tens of thousands. Another important source of information is medieval law. Ten regional law codes have survived from the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries (Fig. 3.1), followed in the mid fourteenth century by a unified law that applied to the whole of Sweden (the landslag, or Magnus Erikssons landslag). There are also a number of narrative sources of various kinds.

Archaeology is one of the strongest sources. Sweden might never have had the magnificent castles or cathedrals of the rest of Europe, but several smaller strongholds have been excavated, along with a number of medieval villages and farms. From the town middens comes a wealth of wooden objects. There are few surviving illuminated manuscripts that were produced in Sweden, but there is a rich vein of ecclesiastical art, not least the many church murals of the fifteenth century. To handle this plurality of sources a method has to be developed that takes into account the specific information each type of source can deliver.2

The sixteenth century brought with it a veritable flood of written sources. Sweden was to become one of the most well-organized states in Europe, and there have been few purges of the Crown’s archives over the centuries. From at least the 1540s, every farm has in principle appeared in the official record several times a year, in tithe and tax registers. Indeed, everything that fell under the aegis of the state was carefully documented. Sweden’s official records also stand out cartographically, for in the seventeenth century–first in the 1630s and 1640s, and again in the 1690s and around 1700–detailed maps of most villages were prepared.3

A feudal society

The period this chapter addresses is described as ‘feudal’, the main reasons being that the bare bones of the social structure remained basically unchanged from the thirteenth century until the eighteenth, and that it was to be found–in its broad outlines–across most of Europe. The term has been questioned, not least since Sweden is often singled out as an exception because of the relatively strong position enjoyed by its bönder (variously, farmers, peasants, or peasant-farmers), and for that reason it is worth defining the various meanings of bonde as they are used here. Before 1000, they should be thought of as ‘farmers’– people who farmed–albeit totally different from farmers in modern times. The term ‘peasant’ is a good approximation for the Middle Ages up to the seventeenth century, as the farmers now formed part of a complex society –a state that extracted surplus production –but were not yet farmers in the modern sense. For the eighteenth century we will use the term ‘peasant-farmer’ (see p. 122) to mark the difference from the ‘farmer’ of the mid nineteenth century onwards. Thus ‘peasant’ in this chapter is closely related to ‘feudalism’, which in the popular mind is often thought synonymous with hierarchy and oppression. Certainly the social system brought varying degrees of repression, but the change after about 1000 meant a greater freedom for many, and the new social web allowed changes that were advantageous to the lower classes. Feudalism as mere oppression is a simplification, because it was open to societal organization from below.

Among scholars two definitions of feudalism prevail: one ‘narrow’ and one ‘broad’. In the more narrow sense ‘feudalism’ denotes a system in which vassals held their land in fief from the monarch, and further down the hierarchy vassals held land from other vassals. This has also been described more vaguely as a decentralized political system. Critics argue that the system of fiefs and vassals is a later construction, and not valid for most of Europe during the Middle Ages.4 Personal bonds certainly played a role, in Sweden as elsewhere, but in this chapter I will make use of the broader approach outlined by Marc Bloch.5 Bloch was inspired by Marxism, but forged his own concept. Generally speaking, in the Marxist tradition feudalism is used to describe a social structure dominated by the relationship between landlords and peasants, emphasizing the latter’s violent suppression and exploitation; indeed, serfdom is frequently taken to be a central feature of feudalism. This is a description that denotes ‘capitalism’ as a step forward, but many Marxists have used ‘feudalism’ in a wider sense; namely as an entire social system, in which the social relationship between the landlords and peasants is just one part of an larger societal whole. Some even declare that a market economy is a typical feature of feudalism.6

Following scholars who make use of the broader definition of feudalism, I take this type of social web to correspond to the technological complex. The complex formed a package of elements introduced at much the same time (‘technological complex’ is a concept to which I will return). The social structure was not determined by just one or even a few fundamental factors such as landownership, but by an elaborate latticework of conjoined social institutions. The nobility, the Church, landownership and the dues it generated, the state, and taxation were all parts of this feudal structure, but there were also collective entities such as the village community and the relatively independent town councils.

Feudal society had a strict hierarchy, with a specialized warrior caste controlling the state and much of the land, and a specialized religious institution, but it was also formed by predominantly small-scale peasant production, where all peasants paid taxes or rents to the state or the landowners. Counterbalancing hierarchism, a strong communalism prevailed, in Sweden with district courts (häradsting), village communities, and (at least in the Late Middle Ages) largely self-governing parishes.

Feudalism in this broad sense is a European phenomenon, but within the framework of this system there was a wide diversity. According to this definition there is no such thing as a ‘typical feudalism’ to be found, say, in northern France. Equally important is the recognition that general change could occur within the broader framework. Crucial here was the transition from particularistic feudalism before 1500 to ‘state feudalism’ thereafter, by which a decentralized socio-political system was replaced by a centralized system. The nobility and many other elements in the social web did not disappear, but were reorganized under the aegis of the Crown.

Thus I argue that Sweden in the High Middle Ages, in a process already under way in the eleventh century and partly already in the Viking Age (see p. 70), took on a social structure that in its basic contours would have been recognizable across much of Europe. This new social structure was established in the late twelfth and the first half of the thirteenth century, later than in most European countries, and would remain the controlling factor in Sweden until the eighteenth century–and in some respects well into the nineteenth century.

Expansion and crisis, 1000–1450

Demography set the basic rhythm. Following a drop in population in the middle of the first millennium AD, there was a slow recovery in numbers. By combining a variety of sources such as archaeological finds, place names, and, for later periods, written sources, it is possible to reconstruct the broad population trends. Starting in the eleventh century, the rate of population increase continued to rise until the fourteenth century. The Black Death and subsequent outbreaks of plague resulted in a deep trough, and it was only from the middle of the fifteenth century that a new, sustained increase set in.

The estimates of Sweden’s population given here reflect the country’s modern borders by including Skåne (and other provinces in the south and west) but excluding Finland. The earliest numbers are more or less guesswork, from the mid fourteenth century we are on firmer ground, and from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the numbers are reliable because they are based on an enormous quantity of sources. In 1000 the population is estimated to have been between 300,000 and 450,000; in 1350 it was c. 900,000; in 1450 it had fallen to 450,000–500,000; in 1520 it was c. 600,000; in 1600, 1,000,000; and finally in 1720, 1,400,000.7

Before the eleventh century vast expanses of countryside devoid of settlement ran the length of the then border between Denmark and Sweden. Another enormous stretch of nearly uninhabited woodland spanned large tracts of central Sweden, separating Götaland from Svealand. The more densely inhabited plains were generally limited to Skåne, the central parts of Östergötland and Västergötland, and around Lake Mälaren in central Sweden. In the north, there were settlements along the coast and the Dalälven, and on the shores of Lake Storsjön in Jämtland. The Sami lived in the interior of Norrland, where at this time they still primarily lived by hunting and fishing. Reindeer herding had not yet expanded to become the main occupation of most Sami.

Three factors contributed to the long demographic expansion that spanned the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries: social change; technological innovation; and favourable climatic conditions, as temperatures peaked in that particular climate cycle. The population rise had already begun in the eighth century, showing itself as a gradual increase in settlement density in already inhabited areas, and it would continue to rise there in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. By the tenth century, the settlements were encroaching on the fringes of the large woodlands. The first step was to burn the woods to create grazing after taking a few crops. Then settlers established small enclosures as islands in the large woods. From the eleventh century the wooded areas in southern and central Sweden were gradually encroached upon, and absorbed piecewise into an orderly, though sparsely populated, countryside. A network of farms began to stretch out over the southern woodlands.8

The thirteenth century saw an even faster expansion into the large wooded areas, impelled in part by the end of slavery (thraldom). Former slaves moved into the woodlands as settlers. As part of the same process of social change, it was now possible for formal contracts to be drawn up between landowner and tenant, which, by protecting the relationship in law, removed the need for the landowner’s immediate physical control. Another factor in the expansion was iron production. Many of the small forest farms in the south gathered and worked bog ore, and it was also at this time that iron-mining began in Bergslagen, the mountainous district north of Lake Mälaren, further adding to the number of new settlements in that region.

Much of the land clearance was undertaken on what was to be freeholders’ land, although slowly but surely the nobility and the Church showed an increasing interest in reclaiming land in order to increase their incomes from rents and taxes. In his ground-breaking work on rural society in western Europe, Georges Duby has highlighted the change that came when the nobility and the Church gradually became more interested in the expansion during the High Middle Ages.9 Something similar happened in Sweden.

In the far north, massive clearances got underway at the start of the fourteenth century. Surviving correspondence shows that the archbishop of Sweden, together with the country’s leading nobles, organized and defrayed the costs of one such large-scale enterprise in the 1320s. Settlers were shipped north to clear new land and build houses at the mouths of the most northerly rivers.10 This project with recruited settlers had much in common with the German expansion eastwards, which doubtless was to some extent an inspiration for the Swedish nobility at the time.

A new factor was monasticism, the importance of which for the expansion has been overestimated in popular belief. Monasteries were established in Sweden long after the expansion had started. Many of the early monasteries in Sweden were Cistercian, an order that in principle founded its houses on virgin soil, but in reality nearly all of them were sited in the rich and already cultivated plains. That said, the Cistercians did undertake large clearances, as for example at the monastery at Alvastra in Östergötland, on the eastern side of Lake Vättern. The monastery set up outlying farms or granges in the eleventh and twelfth centuries on the western side of the lake in the woodlands of Västergötland, which had been one of central Sweden’s empty tracts in the late Iron Age.11 This and the archbishop’s activities in the far north can be taken as indicators of the increasing interest in economic expansion and reclamation among the Swedish elite in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

During the fourteenth century, expansion on the plains ceased. In the 1310s, southern Scandinavia, like much of continental Europe, was hit hard not only by a series of bad harvests and famines, but also by cattle plagues.12 In the woodlands of southern and central Sweden, the limits to expansion with current techniques were being reached at much the same time, and conflicts over land were on the increase. However, in the woodlands above the Mälaren valley and northwards, land clearance continued apace until 1350.13 In this respect, the differences between north and south are also evident in the regional laws from the decades around 1300. In the southern Swedish laws, restrictions were placed on land clearance, but in the north it was still essentially unrestrained. The northern resources remained to some extent untapped.

The expansion came to an abrupt halt in the middle of the fourteenth century. The cause was plague. Sweden, like the rest of Europe, was struck by three catastrophic epidemics in a twenty-year period: 1350, 1359–60, and 1368–9. Not for nothing is the first epidemic still referred to as digerdöden in Swedish, from the Old Swedish digher, ‘great’, and död, ‘death’; similar terms–the Great Mortality–were used throughout Europe in the Middle Ages, while ‘the Black Death’ was only coined much later.

The first epidemic swept across Sweden in the late summer and autumn of 1350, spreading from the west and south up the coasts and along the roads through the interior. Mortality rates may have been as high as 30–40 per cent, although the elite survived in greater numbers. The nature of the disease is still under discussion–usually it is assumed to have been bubonic plague, but in modern times that disease kills the upper classes as well as the lower classes. The two subsequent epidemics wreaked similar havoc, and by the time they had passed, the population in Sweden had dropped to about half its previous total.14

There followed a long period in the last quarter of the fourteenth century during which epidemics left little trace in the surviving sources. This lull may have been the result of a decline in virulence; certainly it has little to do with source survival, for the quantity of evidence remains large. The economy did not recover, and there was no population increase. A long-running civil war and repression at the close of the fourteenth century contributed to the stagnation. At the start of the fifteenth century the plague returned with a vengeance, with major epidemics in the 1410s and at the start of the 1420s. Thereafter the epidemics became less severe with each recurrence.

Despite the enormous number of deaths from the very start, it was only some years after 1350 that abandoned farms began to appear in any quantity in the source material: there were still enough people with little or no land who were prepared to take over empty farms after the first epidemic. In the plains of central Uppland, it was noted in the 1370s that a number of farms had been taken back into use (at lower rents), apparently after they had been deserted for a short time. Besides the landless who were prepared to take over farms, there was also the continued flow of people from the woodlands to the plains, where they could get better farmland. It was the small, remote farms deep in the woods that were abandoned first. Some of them were overgrown by trees, others became meadowland for nearby farms. In the more fertile plains, fields from abandoned farms often remained under cultivation, but were taken over by other farms.

The turning-point came in the middle of the fifteenth century. In the 1460s, economic activity began to pick up, as can be seen in a variety of sources. Clear evidence comes from timber-built houses that have been dated using dendrochronology. A number of such houses have been preserved in which the timber can be dated to the thirteenth or early fourteenth centuries. With the great epidemics, the construction of new houses stopped dead in the 1360s, and no timber can be dated to the century following. It was only in the 1460s that felling for timber to build farmhouses resumed.15

As the population increased, some of the abandoned farms were taken back into use, but many of them had ceased to exist when other farms assimilated their land. The result of the upswing, when it came, was that many began to look even further afield for undeveloped land. Clearances in the sixteenth century spread further into the woodlands even before the population had returned to the size it had been in the mid fourteenth century.

The resumption of cultivation was also a reflection of the fact that the north Scandinavian tracts of woodland were something of an agricultural frontier in northern Europe. With ever-more advanced techniques, it became possible to put this kind of land to full use, for example by using transhumance. It also held unexploited resources that the previous drive for land in the High Middle Ages had not reached. It was for these reasons that the late medieval expansion became particularly strong in Norrland, and, it should be noted, in Finland.

The standard of living increased for the population at large at the end of the Middle Ages as a result of farms being larger on average and production methods more efficient, and of taxes and rents decreasing. The ordinary peasant family could consume more expensive foodstuffs, as well as products such as broadcloth and iron. The Late Middle Ages were characterized by the emergence of non-agrarian livelihoods, part and parcel of the rising standard of living across the population as a whole. This favoured regions such as the mining districts in central Sweden. The towns also did better than the countryside. After a pause, new towns began to be founded again in about 1400, well before the general increase in rural population.16

Agricultural technology

Throughout history, human exertions have resulted in the constant development of farming technology, but in certain periods the innovations came more frequently than in others. The High Middle Ages were one such innovative period. During this transformation a new ‘technological complex’ consisting of a whole series of technological innovations was put in place that set in motion a period of relatively rapid transformation.17 Technological change showed some geographical variation, but there were common, Europe-wide factors such as the increased use of iron, improved cultivation systems, and the rising production of cereals per unit area. Increased demand for iron and improved methods of its production fed off each other, with the result that both production and trade intensified. The wave of new towns founded during the eleventh to thirteenth centuries was thus strongly linked to the agrarian transformation then underway. Interdependence between the rural and the urban community, with a gradually more commercialized agriculture, became an essential element in the socio-economic structure.

Of all agricultural technology, ploughing implements remain among the most important (and are a recurring theme throughout this book). Between 1000 and 1300 the quantity of iron used in agriculture grew exponentially, and with it Sweden’s domestic iron consumption as a whole. One important factor was that iron now was required to break the soil–as ploughs and spades. Unlike the ard, the plough has a mouldboard that lifts the sod cut by the ploughshare and rolls it into the furrow created by the previous run along the field. The ard does not have a mouldboard, with the result that the ard-share cuts a furrow in the topsoil, without turning the earth. The plough also nearly always has a coulter, a ‘knife’ that makes the first, vertical cut in the sod, just ahead of the ploughshare.18

During the Middle Ages the plough spread across Sweden in two distinct phases: the first between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries in the south and west of the country; the second in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries when it spread to the north. In southern Sweden, the new ploughs were rigged with wheels in an arrangement similar to that used across most of continental Europe’s fertile plains–the wheel plough. (In regions where ‘heavy’ wheeled ploughs were common, ards–some of them wheel-ards–were used to rake in the seed.) In western Sweden, instead of wheels the new ploughs were supported and steered using runners of the kind common along the North Sea rim, in Norway and Scotland. When the plough spread to northern Sweden, it was the ‘light’ North Sea plough, but made even smaller and lighter so that it could be drawn by a single horse. The small farms of the north often had only one draught horse, used as both dray-horse and plough horse. This type of one-horse plough spread to the whole of northern Scandinavia in the Late Middle Ages.

In eastern Sweden, the ard remained in use until the nineteenth century. The fact that farmers continued to use ards does not mean that technologically speaking they came to a standstill. The most important part of the ard (and the plough) was the share at the front, which cut into the soil. The earliest iron ard-shares, which appeared in Scandinavia in about AD 500, weighed 300–500 grams and were used selectively. Ards made completely of wood, including the ard-share, were in existence until about 1000 (see p. 68).

Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries heavier iron shares came into use, weighing about a kilo. They were not only heavier, but also longer, and thus broke through the topsoil more effectively and gave greater stability. Wooden shares now fell completely out of use. Ploughs were fitted with these larger shares, but so were many ards. The result was two distinct types of ard in existence at the same time: one used to break up the fallow ground that had become overgrown; and one, with a smaller share, to till the soil that had already been broken up. The wheeled ploughs could carry even larger ploughshares, some weighing up to 2–3 kilos.19

The fact that larger iron shares were used for ploughing and tilling had a dramatic effect on the agricultural demand for iron. Scythes and sickles had been the first iron tools, having been introduced to Sweden before and around the start of the first century AD. The wear and tear on an iron share of medieval size has been estimated to be some seven or eight times greater per hectare than that on a scythe–or indeed a sickle–used to cut grain or hay.20 Since any given piece of land would have been harvested only once, but worked several times a year, the wear on an iron share would have been that much the greater. The oldest surviving forge registers, which date from the sixteenth century, show that shares accounted for the vast proportion of the iron that went into agricultural implements.21

In the technological complex a fundamental link was created between the increased use of iron and the improved cultivation systems. A consequence of the more regular use of larger iron shares was that shorter fallow periods became feasible. Wooden shares and small iron shares were incapable of breaking ground that had become overgrown when lying fallow over the summer, so until about 1000 continuous cropping was the norm, with small fields put to the plough every year. In, or slightly before, the eleventh century, a new method was introduced in which some of the ground was allowed to lie fallow each year: the system of two- or three-course rotations. The fallow was allowed to become overgrown with weeds in the summer; in the late summer was used as grazing; in the autumn it was ploughed. The new ploughs and ards were able to break the fallow in these new field systems.

Most probably the proportion of fallow would have been able to increase gradually as more and more farmland came into use. By the thirteenth century, progress was such that fixed rotations were in place for individual field systems, where a third or half of all land lay fallow each year. With each half lying fallow in alternate years, the system is referred to as a two-course, or two-year, rotation. If instead a third lies fallow, with three large fields as a result, it is called a three-course rotation. Around these two archetypes–common all over Europe–there were any number of variations according to the size of the fields and the proportion left to lie fallow.22

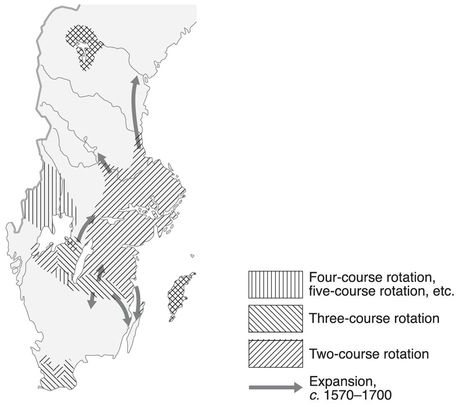

In eastern Sweden, from the Mälaren valley to Östergötland, two-course rotations were the norm. In Skåne in the south, continuous cropping existed alongside two- and three-course rotations, as in parts of Västergötland and on Gotland. In other parts of Sweden continuous cropping continued to dominate. When the regional distribution of different field systems can be established in around 1600 using estate accounts and village maps, it is apparent not much had changed since the High Middle Ages (Fig. 3.2).

Another innovation that made inroads into supplies of iron was the introduction of the iron-shod spade, with its blade edged with iron. In Sweden there are many archaeological finds of iron tools from the Iron Age, but no iron-shod spades: the earliest Scandinavian evidence is from Denmark and dates to about 1000; in Sweden they first appear in images and archaeological finds in the twelfth century. Spades made lighter work of land clearance and ditching. The first true ditches, designed to drain water from fields, date from this period, probably as a result of the introduction of the iron spade. Besides improving productivity and making new arable fields available, ditching strengthened the village community, as it demanded a degree of consensus amongst neighbours: even the farmers who did not directly benefit had to be prepared to allow ditches to be dug across their land.

Figure 3.2 The spread of various field systems in Sweden. The two-course system in eastern Sweden and the three-course system in Västergötland and Skåne were established in the High Middle Ages.

Iron-shod spades had another, somewhat unexpected, effect. They encouraged tillage without draught animals. Written sources make occasional mention of poor farmers working without draught animals, and contemporary images– of Adam and Eve– provide the detail of how the spades were used. Some of the small-holders living close to manors had arable land of such a small size that it was realistic for them to work the land with spades. Spade cultivation during the High Middle Ages is referred to not only in Sweden but all over Scandinavia,23 and their use during the expansion period has European parallels. In the Late Middle Ages, as the population plummeted, labour shortages meant that such intensive, small-scale methods could not be maintained (though spade cultivation continued around the North Sea, on the Shetlands and in south-western Norway).

These and other changes, such as the introduction of the harrow, meant that harvests improved in the High Middle Ages, which in turn lead to technological advances in handling the harvest. The hand-flail replaced the less effective threshing-stick, a stick used to beat the grain out of the ears. The hand-flail consists of two pieces of wood joined by a flexible binding. It is much more efficient, but also more difficult to make than the threshing-stick. Another important change came with the advent of the watermill. A large number of archaeological excavations have shown that watermills became increasingly common in Scandinavia after 1000. Danish research on medieval watermills in particular has made great strides, and it is possible to trace their spread with some accuracy, from the early evidence around 1000 to a dramatic increase in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In Sweden they were common by the thirteenth century at the latest (the regional laws had sections on how to handle the problems and property rights connected with the new technology). In the thirteenth century windmills were also introduced, and spread quickly across the whole of Scandinavia.24

Most of Sweden was woodland or plains verging on woodland, and livestock farming had always played a central role, but the technological transformations of the High Middle Ages were directed at arable farming, and there was a relative shift towards arable farming with increased grain cultivation as a result. Since this was the basis of calorie production, more people could be provided for. This intensification of land utilization was the basis for the acceleration in population growth and food production that distinguishes the High Middle Ages.

Livestock farming

Sweden’s brand of animal husbandry showed the influence of its large swathes of woodland. Telling examples of the importance of the great woods to medieval Sweden come from a very different source–miracles. These tales of human misery, of disease and drowning, of people saved by the intercession of patron saints, survive from across the whole of Europe. They offer an insight into the daily lives of ordinary people–and provide an opportunity to draw European comparisons. Often it was children who were in peril, and one particular form of childhood accident unique to Sweden was small children lost in the woods: if they strayed too far from home they could get lost, and the villagers would have to spend days beating the woods. Several times children were said to have gone astray in the woods when they went with adults who were taking livestock to graze, or they were able to find their way home when they saw one of the farm animals and followed it.25 Many small hamlets were like islands in an ocean of trees, and around the villages, in woodland pastures, the cattle roamed. Often the most important objective in mind when swiddening land (clearing it by burning) was the grazing areas opened up in the woodland after one to three years’ harvests of grain (most often rye).26

Although livestock farming did not undergo any dramatic changes in the High Middle Ages, there were some changes, typically connected with commercialization and more particularly with butter production. Since butter was obtained from cream it was an expensive product, one that could be transported over long distances and still be worth the carriage. Butter became an important commodity not only in trade, but also to pay dues and taxes. Increased butter production was linked with technological change. Since time immemorial, people had shaken cream into butter. Now larger amounts of cream were poured into a ‘plunge churn’; a tall, narrow cask, in which a churning-staff that ended in a wooden cross or a disc with large holes in it was pounded up and down. Pictures and wooden remains found in archaeological excavations across north-western Europe make it possible for us to follow the more efficient plunge churn’s progress after 1000.27

In the Late Middle Ages the change in livestock farming was instead influenced by the shortage of labour. During the High Middle Ages almost only adult men tended herds. Their job was to herd the animals through the woods to the best pasture and to protect them from predators. This had once been the work of slaves, and even when slavery became uncommon, in the late thirteenth century, the law codes show that the herdsman’s social status remained low. In the Late Middle Ages this slowly began to change. Women and children began to work as herders, primarily because of the acute labour shortage. Adult men were needed elsewhere. Later, in the seventeenth century, adult herdsmen would disappear completely except for the southernmost part of the country, in Skåne, which followed the continental pattern. Here the village’s common herdsman replaced the private herders, and was to attain a relatively strong social status as both a specialist and a professional.28

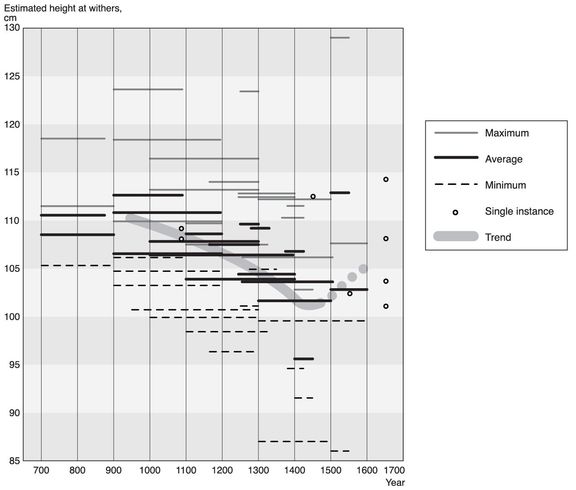

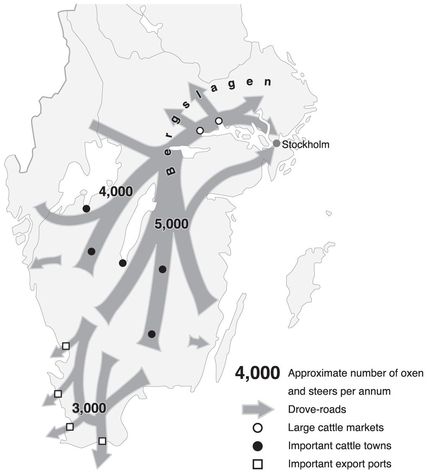

Most livestock were noticeably smaller than modern breeds, and cows more so than most: studies of bone remnants show that, measured at the withers, the average size of a cow dropped from 110 cm in about 1000 to a whisker over 100 cm in the fifteenth century (Fig. 3.3). One reason may have been the accent on obtaining as much butter as possible, which often led to animals being weaned too soon. Quite simply, the calves were undernourished.29 In the sixteenth century the trend turned, and cattle slowly began to increase in size. This was largely thanks to the reason for keeping cattle gradually changing. There was a growing demand for beef cattle, but they had to be strong enough to carry themselves on their own four legs to the market or the shambles.

Figure 3.3 The average height of cows in central and southern Sweden (measured at the withers). Each excavation is denoted by three lines (maximum, average, and minimum values), and the length of each excavation line shows the time span in question. At the end of the period there are a number of sporadic values. The trend (the broad lines) clearly falls throughout the Middle Ages–previously and subsequently, cattle were taller.

Farms and estates

The feudal structure consisted of several, interconnected layers of social institutions. One was the relationship between those who farmed and the elite who lived by what farmers produced–a relationship that was already undergoing a transformation. Another important building block in the social web was the strengthening of the collective, which for the rural population meant the village community. The overarching change was the gradual establishment of a state apparatus.

The High Middle Ages saw a new relationship between farmers and the elite, but it was also a transitional phase, for the shift was not completed until the fifteenth century. Slavery had been an important element in the social structure until the eleventh century (see p. 71). Although we have a Scandinavian word, thrall (träl), the term ‘slave’ will be used here for two reasons: Scandinavian ‘thraldom’ was no less pernicious a form of slavery than any other, and bore similarities with slavery in other parts of Europe at the time; and as well as träl there were a number of different Scandinavian terms for slave that referred to their specific status, leaving slave the better blanket term.

Slaves and other dependent work-forces enabled the elite, the chieftains and large farmers, to maintain large households and control small territories. This control of labour was the most important way in which resources were transferred to the elite. From the eleventh century the full force of slavery was tempered, and clear rules developed for the manumission of ‘thralls’ that also gave slaves and the half-free some kind of legal protection (in matters such as property rights and marriage). The final unravelling of the system followed in the thirteenth century. From testamentary evidence it would seem that the nobility had freed most of their slaves by the end of the thirteenth century.30

Sweden’s transformation between the eleventh and the fourteenth centuries brought with it legal instruments that made it possible to organize the large-scale transfer of resources to the elite along new lines. It became usual to exact dues from the land systematically, but in its fully developed form the landbo system of fixed-term tenancies did not exist until the thirteenth century.31 A dual manorial system took shape, while waged work became a socially accepted alternative when slavery vanished. Taxes levied from the peasantry also became a part of this new system of exploitation.

What the elite controlled was no longer mainly men, but land. It was crucial to these changes that landownership became more precise –and complex. Land began increasingly to be treated as something to be exchanged, sold, or bought, albeit hedged about with restrictions that gave family and kin various pre-emptive rights to land put up for sale, for example. Ownership also began to be diversified: the right to dispose of land, the right to profit by the land, the right to work the land. Several factors contributed to this shift in the nature of landownership. One was capital investment in the shape of land clearance, ditching, manuring, and other improvements: the laws show a clear connection between investment in land clearance and the legalized, private ownership of land. Another was the rapidly dawning primacy of the written word, with written title-deeds that could be both exact and enduring–unlike verbal agreements. The fact that units of land measurement were specified at much the same time was another factor. More precise land measurements were also connected to the strengthening of the village communities, since both rights and obligations had to be apportioned more exactly.32 The village courts were often held at the parish level, as many of the hamlets and small villages were too small to form their own entities, but the obligations had to be determined village by village–and thus a precise measure was helpful when a discussion came up.

It is often said that serfdom, which bound farmers to the land for life, was never introduced to Sweden, but in the High Middle Ages something very like serfdom was customary for those who were freedmen, or rather ‘half-free’. They were still ‘owned’ in some respects by their landlord; in thirteenth-century regional laws they were referred to in eastern Sweden as fostre (from the same root as the English ‘foster’, as in foster child) and frälsgiven (lit. redeemed) in western Sweden; and they were certainly tied to the land.33 Small-holdings clustered around the manors, often run by such freedmen, who were expected to work the manor’s land as well as their own. They often had no draught animals, and should really be considered ‘crofters’ rather than ‘peasants’. Similarly, larger family farms run by tenants were also directly tied to the manors. This manorial system, which showed similarities to the dual structure that had taken shape in western Europe some centuries before it spread to Scandinavia, dominated on the plains and even in large areas of the southern Swedish woodlands.34

Many of the manors in Sweden were quite small, not more than two or three times larger than a tenant’s or freeholder’s family farm. Such small manors were run directly by the estate’s bryte or villicus (reeve). In a form of sharecropping, he was often equipped with implements and livestock but had to pay half his harvest in rent. Besides the manors, surrounded by ‘crofters’ and tenant farms, there were family farms run by freehold farmers or by tenants that were some way distant from their manors. In some parts of the country this type of family farm already predominated in the High Middle Ages.

The first time we can get a clear picture of the distribution of landownership in Sweden (excluding Skåne and other provinces acquired later) comes around 1520, when some 45 per cent of the land was owned by freehold peasants and 25 per cent by the Church, while the nobility controlled 25 per cent and the Crown 6 per cent.35 During the Late Middle Ages the peasants and the Church had seen their share grow, while the nobility’s had dwindled, but the proportions had not changed dramatically since the broad outlines had emerged in the High Middle Ages. The patterns were far from even, to the extent that in northern Sweden virtually all the land was owned by peasants, but in the plains most was owned by the nobility. Already in the Middle Ages, but more so from the sixteenth century onwards, actual landownership became fixed in various cadastral categories (see p. 121).

When the Black Death and subsequent epidemics swept away half a generation, there was no longer anyone to tend the small plots around the manors, and the half-free just ceased to exist. The manors could no longer continue as before, since they had no dependent work-force, no crofters from whom they could exact labour. Many manors were broken up in a process that is sometimes called the ‘levelling’ of the farms. The tenurial structure that was to emerge would dominate for many centuries, with its numerous family farms of varying sizes and a small number of manors to which dues and taxes were owed.

A typical farm

The written sources allow us to write of a ‘typical farm’ in the period 1000–1350; in this case somewhat larger than the average farm, for the size of the smallest units eludes our knowledge. For the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period, more accurate estimations of not only typical but also average farms can be given. That being so, it seems that a ‘typical’ farm in the High Middle Ages was centred on three buildings: (i) a main dwelling-house; (ii) a threshing barn, where the harvest was stored before threshing; and (iii) a byre, where cattle and other large livestock were stalled. As well as the three central buildings, there was often a granary; barns for hay and straw; a larder to store meat; a härbärge (lodging, lit. harbinger), a store that could also accommodate guests; and a series of other buildings with special functions. The typical farm had at least half-a-dozen buildings. Earlier, a multi-functional house, the long-house, had been the norm (see p. 69), and even as late as the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries there were still examples in northern Sweden of dwelling and byre sharing the same building. By this point the farm with many buildings was well established in the rest of Sweden. Much of Sweden in the High Middle Ages went over to log-built buildings. This imposed limitations on the buildings’ size, for their modules–the dimensions of the structural components used to determine a building’s proportions–were set by the length of the available timber. This was one of many changes in building techniques that favoured the construction of smaller, single-function buildings.36

It seems probable that before the transformation of agriculture in the fourteenth century the arable acreage available to each farm was quite small, but during the expansion at least the farms on the plains increased their amount of arable land. Between 1000 and 1300 such a ‘typical farm’ had about 3–6 hectares put down to crops, which meant its total holding of arable land would have been about double that, at least in the areas where a two-course rotation was practiced. In the Late Middle Ages, the size of the plains farms increased as many farms were consolidated, leaving the typical farm with perhaps 5–7 hectares in crop. As a rule, freeholders had more arable land than tenants, while in the woodland regions the arable acreage had always been smaller.

Turning to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there is detailed information on the size of the arable acreage across Sweden to be gleaned from the surviving village maps. By this time the plains farms generally had 4–6 hectares in crop, while in marginal areas the farms had about 2 hectares of arable land. That the plains farms’ average acreage was less than it had been in the High Middle Ages was primarily an effect of population growth, which prompted farm subdivision (see p. 143). In terms of grain cultivation, barley dominated in much of the country, but all four cereals–barley, rye, wheat, and oats–were grown. Beginning in the sixteenth century it becomes possible to establish the proportions in some detail, and I will return to this later.

The quantities of livestock can be reckoned for the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries because of the considerable number of surviving inventories of reeves’ and parish priests’ farms, from which it appears that two oxen and four cows would have been considered the basic herd for a ‘typical’ farm. Sheep, goats, and pigs were usually found on most farms, as were hens. By using a long series of wealth taxes from the 1570s to around 1640, we not only have better information with which to arrive at an average, but also the chance to identify regional differences. In central Sweden a typical farm had 2–3 draught animals (horses or oxen), 3 cows, 2 heifers and steers (young cattle), 2–3 pigs, 5 sheep, and 1 goat; by comparison, the equivalent farm in southern Sweden’s woodlands had 2–3 draught animals (generally oxen), 4–5 cows, 4 neat cattle, 3 pigs, 5 sheep, and 1–2 goats.37 Surprisingly, there are some constants between the ‘typical farm’ of the High Middle Ages–a larger family farm or a smaller manor–and the family farms of the early modern period, both when it comes to acreage and the number of stock. It seems likely that in the Late Middle Ages and the sixteenth century, farms on average had slightly more animals than they had in the High Middle Ages.

In the Late Middle Ages draught horses were used across much of central Sweden. The Late Middle Ages may have seen their numbers increase, but the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a transition back to draught oxen in much of southern and central Sweden; thus by the early modern period, draught oxen were used for the heavy work in most of the country, but in northern Sweden the only draught animals during the whole period were horses.

The village community

Farms that are close to one another will always evolve some sort of collaboration, and villages existed long before agriculture. What happened in the High Middle Ages was that this collaboration between farmers was put on a formal basis and given the protection of the law. The regional law codes of the period contain long paragraphs concerning the regulation of the villages’ common business. This collectivization of production was motivated by the very transformation that it in turn promoted; a process that was seen all across Europe. The village community became a part of the new feudalized social web, and at the same time became a necessity for reasons of a new package of production technology.38

As land clearance gradually began to reach its fullest extent, farms acquired fields that bordered neighbouring farms, and two- or three-course crop rotation demanded joint action. A system of ditches laid out over the fields was another technological development that strengthened the organized village community. Grazing rights on common pastures and harvested fields became of importance when the pressure on land resources grew.

A most important innovation, tying the village community together, was new fencing practices. The villagers created common infields, consisting of fields and pastures enclosed by a single fence, and by joining forces instead of fencing each parcel of land separately the farmers could save themselves considerable time and labour. Every villager then became dependent on all the others’ work. A single gap in the fence would open up all the fields to marauding animals, domestic or wild. No mismanagement could be allowed. This required regulation. In the sections of the regional laws, and indeed the national law, governing village communities, fencing actually took up more paragraphs than any other common task in the villages. If anyone broke the fencing regulations the farmers could invoke the law and turn to a higher court, although then the Crown would share in any fines. Surviving registers of court fines show that disputes rarely advanced to higher courts: the mere threat was enough.

Hundreds of kilometres of wooden fences were built, and gave a distinctive structure to the landscape, dividing it into the fenced inmark (infields) and beyond them the utmark (outlying lands) where livestock were grazed. Even in the eighteenth century, fencing was still the most important communal issue in the majority of Swedish villages.39 It was not only the quantity of fencing that was new, for there was a newfangled kind of fence, as solid as a wall, which spread across Sweden north of Skåne in the High Middle Ages: the withy fence, consisting of a row of paired poles held together with withies, with thick diagonal bracing between. Made properly this fence is almost impossible, and actually dangerous, for livestock or wild animals to break through or jump over. It replaced the wattle fencing that had been common hitherto. A withy fence required an enormous amount of small-sized timber.40 It was for this reason the plains of Skåne were the exception, because of the lack of woodlands there, and hedges, earth banks, and wattle fencing (see p. 57), together with professional herdsmen, were used to keep the animals away from the growing crops.

When the villages’ common fields, the infields, were established they began to be divided into strips so that everyone had a share of each kind of soil. The eastern Swedish law codes went further and imposed a systemized form of strip farming known as solskifte (divisions according to the sun, lit. sun-division), in which farmers were assigned strips in the same order as each farm’s location in the village (see p. 126). Thus the farm furthest to the west in the village held the westernmost strips in each field, and so on. It was in the thirteenth century that villages began to be divided up according to this principle, but it would be several hundred years before the process was completed.41

Written village by-laws were not recorded until the eighteenth century in Sweden, as the extensive sections in the national law on ditches, mills, fences, pastures, and other village affairs made a law-code for every village superfluous. Skåne was again the exception, with its written by-laws from the Late Middle Ages and early modern period, as in the rest of Denmark and Germany.42

Taxation and the nobility

State power, along with an upper class created by the agency of the state, was a fundamental component in a feudal society. The upper classes based their power on landownership, but also on specific duties. The nobility were a warrior caste; the priesthood were religion’s specialists, although only those at the top of the ecclesiastical hierarchy were counted as members of the social elite. The parish priest was very much part of his village, and found his social equals amongst the well-to-do farmers there. Nobility and Church alike bound Sweden tightly to Europe’s feudal social structure.

For a state machinery to be established, regular taxation had to be introduced to Sweden.43 In essence, such taxes were a commutation of service due to the king; a service the king previously had only been able to exact fitfully and on a very small scale. The legitimization of taxes took two approaches: from Svealand down to Östergötland and the Småland coast, ledung (Eng. lething), the naval service that had once been demanded of all free men, was commuted to an annual tax; in Västergötland and other parts of Götaland it was the commutation of gästning (lit. guesting), the king’s right to be lodged and fed as he progressed through the country, which gave the tax its legitimacy. The basic tax, established in the thirteenth century, then grew incrementally with the addition of further special levies.44

The nobility did not have to pay taxes; instead they were to do their social duty by raising and leading mounted troops. The Church enjoyed the same privileges as the nobility. This exemption from taxes was formalized at the end of the thirteenth century, at much the same time as general, permanent taxation was introduced. However, nobility was still in principle determined by eligibility: the noble who could no longer bear the costs of a fully armed and mounted warrior would be degraded to the rank of peasant, and in the wake of the late medieval population collapse this was a common occurrence. In the sixteenth century Swedish nobility finally became hereditary, paving the way for a new phenomenon: the landless noble, wholly dependent on royal service.

Land-rent, ‘rendered’ by tenants for the ‘land’ they leased, appeared at much the same time as the state emerged as a discrete power. Indeed, it was under the state’s aegis that landownership and land-rents could exist. Much later, in the early modern period, the distinction between land-rents and taxes blurred, with the result that the dues paid to noble landlords were thought to be recompense for the tax exemption the tenant enjoyed.

The peasantry were confronted by a number of new dues to be paid; an expansion of the extraction of resources from the lower classes that went hand in hand with the remoulding of the military system, which also affected agriculture. One such factor was a pressing need for warhorses. The warrior caste in part founded their power on a military revolution that gave men-at-arms–the heavy cavalry of the day–a massive advantage compared to the general levy’s foot-soldiers. Horse power was a clinching factor–yet a stallion warhorse might cost six or eight times more than an ox. In Sweden, warhorses were bred in stod (a herd of horses, from which comes the English ‘stud’) consisting of one stallion and usually about ten or twelve mares, which were allowed to roam the woods. The stallion foals were then gathered from the herd to be raised as warhorses. After the drop in (human) population, warhorses were more often bred in fenced parks, converted from abandoned farms. However, the woodland stod were not completely given over until the Late Middle Ages.45

Transformation in the Late Middle Ages

After plague killed around half the population, land-rents were cut. As early as 1353 a letter noted that land-rents had halved because it was no longer possible to find people to work the land. The following decades saw a struggle between landowners, determined to hold land-rents at the same level as before, and their tenants. The attempt was doomed, since the tenants could simply move to an abandoned farm somewhere else if they felt the land-rents were too high. The overall reduction in land-rents is hard to judge because they were paid in money or in kind (often grain or butter), or even in days’ work (corvée), but it has been calculated that by the start of the fifteenth century the average drop was by about a half.46

One source of widespread conflict that came on the heels of farm abandonment was the requirement for tenants to repair buildings and fences. Long into the fifteenth century, shoddy construction was one of the commonest causes of conflict according to the registers of court fines, and several decrees were issued in the fifteenth century to force tenants to undertake repairs, and not simply use the farm and then make off. However, these decrees were to be turned to the farmers’ advantage when the upturn finally came, for if the farmer did more maintenance than was required, he could be recompensed in the form of a tax exemption. This was to be of considerable importance in Sweden’s sixteenth-century expansion.

What followed in the latter part of the fourteenth century and early fifteenth century can probably best be termed a feudal backlash, or ‘the feudal reaction’.47 The population had been reduced by half and land-rents had halved too, but the upper class survived to be provided for after the epidemics. The status quo was untenable. There were two possible solutions. Either the elite would have to find some way to continue with their exactions, or they would be forced to reduce their consumption. The realities of power encouraged the armed portion of the upper classes, especially the higher and more powerful parts of the nobility, to attempt to defend their position. The result was a plunder economy, later matched by a rise in royal taxes.48

Civil war dragged on through the whole of the second half of the fourteenth century. A number of political twists and turns, which need not detain us here, culminated in the arrival of German knights in the autumn of 1363, and a section of the Swedish nobility hastened to join in. They proceeded to conquer much of the country in short order, partly to be able to pay off their creditors at home, partly to establish themselves in the new country. Much of the lower Swedish nobility were annihilated or decided to give ground and become peasants.

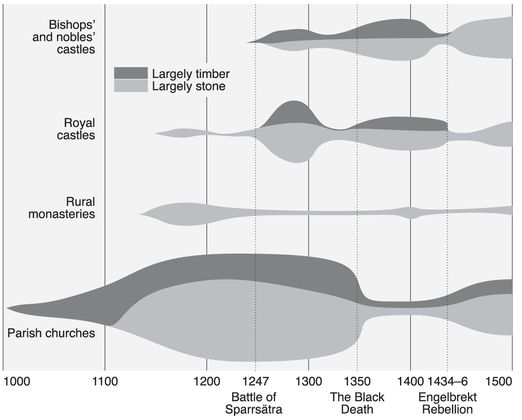

One indicator of this feudal reaction is the level of building activity. All kinds of building, from churches to castles, had been erected or remodelled during the period of expansion in the thirteenth century. After the Black Death investment in castles and fortifications increased, while all other construction work came to a halt (Fig. 3.4). Although many of the new castles were relatively small, the result was an increase in the burden placed on the people. These investments to further control and exploit the people were a dysfunctional reaction on the part of the elite during a period of steep decline in production.49

From peasant rebellion to parliamentary Estate

THERE WAS SOCIAL strife even in prehistoric times. To imagine that pre-feudal society was devoid of social conflict, an egalitarian golden age, is wishful thinking. However, it is only once there are written sources that we can follow the clashes in any detail.

From the thirteenth century up to 1350, many of these disputes were about land rights. Tithes were another controversial issue, and one of the first known uprisings (in 1180–2) began because the peasants in Skåne did not want to pay tithes to their bishop. In the decades before the Black Death one annoyance was fishing rights, which may partly reflect the strain that population growth was putting on food resources. After the great plague epidemics, it was to be the various forms of rural resistance that would dominate the written record.a

Complaints about state taxes had been heard throughout the fourteenth century, but at the start of the fifteenth century protests mounted at the level of taxation. In 1432 they boiled over into a peasant uprising in the northern part of the country, which culminated in 1434–6 with the whole of Sweden in full rebellion, and an alliance of numerous social groups ranged against the king. For the tax-paying peasants, especially the freeholders, the central issue was the lowering of taxes; for the clergy, the Church’s independence; for the native Swedish nobility, it was forcing out the foreign nobles; for the burghers, it was the lowering of tolls and tariffs. The revolt is now known as the ‘Engelbrekt Rebellion’ after its eponymous leader, a member of the lower nobility. A very large number of castles were burned to the ground, never to be rebuilt. The alliance between nobles and peasants collapsed when Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson was murdered in 1436, and the peasant revolt continued until 1438–9. Despite ultimately being put down, it still led to lasting tax reductions.b

The Engelbrekt Rebellion saw the start of a new phase in Swedish political history, when increasingly well-organized and well-equipped armies of peasants became a force to be reckoned with. There was full civil war where the peasant armies played a decisive role in 1457, 1463–71, 1497, and the entire period between 1501 and 1523. The peasants used the same tactic as victorious peasants elsewhere in Europe–they withdrew to the ground which they could master, in Sweden the deep forests. On several occasions they inflicted crushing defeats on the foreign mercenaries drafted in.

As time went on the peasants’ demands grew. They demanded control of the judicial system; they discussed how the country should be run. At first, negotiations were held when the peasant armies were in the field, or when there was a fair, but out of this grew the peasants’ participation in the Diet, which would be put on a formal footing in the sixteenth century.

Notes

As well as the large rebel alliances, there were also local uprisings that were often straightforward peasant revolts, like that in Västergötland in 1483–6; the last major rebellion, in Småland in 1542–3, was another, directed at the new and ever-stronger state. After this, peasant protest in Sweden increasingly went through more peaceful channels, not least ‘the Peasants’, or Estate of the Peasants, in the Diet.

The Swedish Diet continued to operate throughout the seventeenth century, now not only with representatives from the nobility, clergy, and burghers, but also a peasant representative from virtually every county hundred. The Peasants chose to concentrate on a small number of issues, amongst them the adoption and implementation of the Reduction, in which they played a decisive role.

In the seventeenth century there were no major rebellions in Sweden, despite extreme oppression, largely because the peasants continued to be represented in the Diet. That said, the Crown deemed it prudent to keep some soldiers at home to stop attempted rebellions, and there were a number of small uprisings. In the early eighteenth century these uprisings began to escalate, and were directed against the major war then raging– the last Sweden was to wage. Peasant unrest was to be one of the key reasons why Sweden chose a more peaceful path, abandoning its great power ambitions.

During the eighteenth century, the Peasants gradually advanced their position in the Diet, and pursued issues such as property rights and tax reductions. The last major peasant rebellion in Sweden, in 1743, was more of a protest march on Stockholm than a violent revolt. It was put down, but was followed by substantial tax cuts.

By the start of the nineteenth century, the Peasants were engaged in broader political issues, generally taking a liberal or radical stance, and they were to play a crucial role in the transition from Diet to Parliament in 1866. Quite why the close of the nineteenth century would see the Peasants in Parliament forming a conservative bloc is another story altogether.

The civil war finally led in the 1390s to Scandinavia being united under one ruler, Queen Margaret of Denmark, at which point a fixed rate of taxation was imposed to replace decades of extortion. The levels were significantly higher than before, and further taxes were introduced when, at the start of the fifteenth century, the united kingdoms (Denmark, Norway, Sweden) embarked on a war in northern Germany. The reaction from the peasants was not long in coming. Their resistance ran the gamut from loud complaints to full revolt, and reached its first peak in the Swedish rebellion in the 1430s. This was followed by a century of civil war in which peasant armies were a powerful factor (see p. 98). These clashes led to a succession of tax reductions that dragged rates down to an all-time low.

The close of the Late Middle Ages was thus to be a time of increased consumption for the majority of Swedes. After the immensely difficult period of the feudal backlash, a period of prosperity beckoned. First land-rents and then taxes had fallen, while production per capita had increased. Not only had the average size of farms increased, with larger fields and meadows, but there were also certain technological changes that followed the shortage of labour. Most importantly, scythes and sickles were made longer so that productivity increased during harvesting and haymaking, the two busiest times of the year.50 Iron production rose, while imports, particularly of textiles, grew. Even servants were often paid in imported cloth. Archaeological excavations show that everyday items such as combs were now mass-produced. The number of high days and holidays increased, and religious guilds–for feasting and praying–were founded in rural districts. People ate and drank more expensively, with ale and meat now within the reach of many. By 1500, the majority of the population were enjoying a degree of prosperity that would long elude their descendants.51

Figure 3.4 Different types of large-scale building in the Swedish countryside. The curves are not immediately comparable (if they had been directly related to the size of the investment, the parish churches’ curve would be far broader). After the Black Death it was the construction of the nobles’ and bishops’ castles that increased first, and only later the Crown’s. Many of these were small fortresses, primarily built of wood, with perhaps only a tower built in stone. All the smaller Crown’s castles were razed when peasant armies in the revolt of 1434–6 singled out these key locations.

State feudalism

Over the course of the sixteenth century the power of the Crown was strengthened. The Church and the nobility were brought under its control. That the Crown was to attain such a strong position in Sweden was paradoxically the result of the relative strength of the peasantry. After a century of revolts, an alliance had been struck between the peasant armies and sections of the nobility, led by a riksföreståndare (regent). Sweden proceeded to become a ‘strong’ state, in the sense that there was a functioning administration that could enlist support for its decisions and then carry them through, and in this it was assumed that all the various groups in society–the taxpaying populace as well as the nobility–would meet their social obligations.

The last and most successful of the nobles to lead the peasant armies, Gustav Vasa, became regent and then proclaimed himself king of a new dynasty in 1523. A permanent base for the machinery of state was established in Stockholm, and an administrative network was built up across the country. A strong Crown heralded the resumption of heavier taxation, but in that there was also an inherent social contract that required the Crown to take the peasantry into consideration. The fact that the peasantry had representatives in the Swedish Diet (parliament) only strengthened the contract.52 This notion would prove to be the fulcrum on which the massive political exertions required by Sweden’s Age of Greatness would turn when ultimately the war economy discussed below was established.

In most essentials the structure of Swedish society remained the same as before. Power derived from landownership, and the leading noble families were generally the same as during the Middle Ages. The nobility’s most important privilege, exemption from taxation, was untouched. Rather than a new society, it would perhaps be more accurate to describe what emerged as a new, formalized structure of power, in which nobility had become hereditary. The period between 1500 and 1700 is often called the Age of Absolutism, referring to the overwhelming power of the state in that period. Using the broad definition of feudalism, the social web as the constituent parts, and with most medieval institutions still in place but now drawn under the aegis of the state, one could equally well call the period the Age of State Feudalism.53

Sixteenth-century expansion, seventeenth-century stagnation

The deterioration in the climate known as the Little Ice Age was already underway in the Late Middle Ages, and was to continue right through to the eighteenth century. The drop in temperatures became particularly steep towards the end of the sixteenth century, and the average temperature then and for the entire seventeenth century was a full degree under what it had been in the medieval warm period.

There have been great strides made in historical climate research in recent years, so we now have a detailed picture of climate change in Sweden. A series of indicators are used to trace climatic variation, such as sea-ice cover in harbours, sledging conditions, and of course purely scientific measures such as tree-rings. The period from the 1570s to the 1640s saw a series of crop failures due to cold weather and heavy rainfall; thereafter the climate gradually changed so that drought became a greater problem in bad years. The most difficult years came at the start of the 1570s, around 1600, and at the end of the seventeenth century. In simple terms, the cold struck harder in the north of Sweden, the drought harder in the south.54

Despite the worsening climate, the population continued to increase, and from the sixteenth century it is possible to describe this in some detail. During the Late Middle Ages there was a general recovery, with abandoned farms brought back into use, but then the rise continued beyond the previous medieval high point. As a consequence of land clearance, woodlands that previously had not been settled were now populated. An extensive form of swidden was used in the sixteenth century to open up the woods for pastures, and at the same time Finnish settlers brought in new swidden techniques adapted to coniferous trees.55 The fact that permanent settlements now covered increasingly large areas of the country was to be a significant factor in the changing use of the woodlands, which now saw a number of diversifications from agriculture. Requisitioning of the woodlands enabled Sweden to be a leading exporter of raw materials (iron, copper), as most of the refining processes of the day needed fuel.

Much of the land clearance took place on Crown land, and the Crown in turn made considerable efforts to encourage this. It enforced its proprietary rights to the deep woodlands with a view to leasing out the ground to settlers, who were also offered a period of tax exemption, often for a decade or more, with the argument that it was recompense for their building work and efforts in land clearance. The Crown’s policy met with the greatest success in southern and central Sweden: in these parts of the country many of the settlers became the Crown’s tenants. The Crown was not alone in this, for also the nobility began to offer settlers exemptions from land-rents, and there was also clearance on peasant land, particularly in the areas where freehold peasants were in the majority.56

Registers taken to keep track of how the cleared land should be taxed reveal the details of the process. The first thing a settler did was to swidden his land–he felled all the trees and then burned what was left. Then he had to grub up all the stumps before the ground could be counted farmland. The turf was cut and turned, after which the land was ploughed and fences erected. Meanwhile the various farm buildings were under construction. The dwelling-house was nearly always first up–both people and animals needed somewhere to live. The byre was usually next, normally before the third year. Until that point, people and animals lived together. After that came the stores for grain and hay, but there was usually a delay of five or six years before the family had time to raise them. These settlers established small-holdings, often far out in woods, and most of them had less than a hectare of arable land when they became liable for tax after some ten or twelve years or more.57

The increase in population at the end of the Middle Ages had been slow, but was to steepen over the course of the sixteenth century, reaching what was for a pre-industrial society an impressive rate of 0.5–0.6 per cent per year over the century, picking up momentum as the century progressed. The increase slowed in the first decades of the seventeenth century, but continued for much of the century so that the average increase amounted to just under 0.3 per cent per year over the century. The rate of increase was not geographically even. In an arc from Småland, across Västergötland and Värmland, and into southern Dalarna, the woodland areas saw an expansion. The plains generally experienced a relative stagnation. This was true even in the formerly Danish–Norwegian areas, for Skåne was hit particularly hard by the wars between Sweden and Denmark in the second half of the seventeenth century, and its population remained constant at about 150,000. In 1700, some 1.4 million people lived within what are now Sweden’s borders, and in the subsequent two decades average population growth slowed, although this in fact meant a slight rise followed by a fall. The country was at war with all its neighbours, and had been struck by famine and plague; it was only with the peace of 1720 that the population began to increase again.58

Living standards and total production

An important issue is whether food production was able increase at the same pace as the population. This question can be approached from two different angles: consumption and production. The first can be estimated from a number of written sources, but average heights have also been widely used as a proxy for living standards. As for production, in broad terms cereal and livestock production rose, but there was a relative shift towards cereal cultivation.

The accounts of both manors and hospitals put figures on the poorest Swedes’ diet. During the years of relative plenty in the sixteenth century, 70 per cent of the calories consumed came from cereals, but in the seventeenth century this increased to 80–90 per cent. At the same time the average calorie intake dropped: calculations based on the figures for farm-hands and paupers indicate an average reduction of one-sixth. However, in the seventeenth century the majority of the population lived above the hunger line, with the exception of years with bad harvests.59 This change is confirmed by average heights. Six excavations from medieval Sweden and ten from medieval Denmark with enough material to be analysed show that the average height was constant for the Middle Ages, around 170–3 cm for men. In northern Sweden the men were taller, 173–4 cm, and in the southernmost plains in Skåne and eastern Denmark they had a mean height of only 170–2 cm. At the middle of the seventeenth century the mean height for males had fallen to 166–7 cm, according to one excavation from northern Sweden with enough skeletons to be analysed statistically. It was only at the start of the nineteenth century that men’s height generally began to increase again (see pp. 133 and 144), and then this change can be followed in conscript registration. Women in the Middle Ages had averaged 160 cm or slightly less.60