INTRODUCTION

Stereotypes, Opposition, and “the Sixties”

IN 1970, DRAMA CRITIC ROBERT BRUSTEIN COMPLAINED THAT IN America revolution had been reduced to a form of theater. What had once appeared to be legitimate opposition to the morally bankrupt policies of the United States government had become little more than costume drama. Groups such as the Weathermen and the Black Panther Party, he wrote, “certainly have the ability to transform their rhetoric into violent action, and are now suffering the consequences in even more violent official retaliation.” Nevertheless,

both actions and rhetoric are an extension of theatricality, and proceed through the impulse to impersonation. When the Weathermen lock arms down a Chicago street, chanting “We love our uncle, Ho Chi Minh” . . . or when the Panthers, in paramilitary costumes, have their pictures taken serving breakfast to ghetto children, then the link with public relations and play acting becomes obvious. Indeed, the alleged murder of an alleged Panther informer in New Haven bore sufficient similarities to the plot of a recent movie . . . to make one suspect that life was imitating art.1

Shortly after the appearance of Brustein’s essay, journalist Robert L. Gross of the Miami Herald stated the argument in even starker terms. “Posing is the key,” Gross wrote. “Revolution has become the giant put-on of the era.”2 To many, these arguments would have seemed preposterous. How, in the face of mass protests, police riots, shootouts with authorities, threats against heads of state, and even bombings, could anyone think of trivializing the political conflicts taking place in the United States by referring to them as mere “theater”? The answer, according to Brustein, lay in the guaranteed right to free political speech. By allowing individuals to “speak their minds,” American culture had succeeded in replacing direct action with “radical verbal displays.”3 It should have come as no surprise therefore that no matter how loudly these “revolutionaries” called for meaningful action, their cries seemed to fall upon deaf ears. Stripped of its efficacy by the putative tolerance of contemporary American society, political activism appeared to be more caricature than rebellion.

But what if the “verbal displays” Brustein lamented represented, in their very theatricality, a form of resistance that neither he nor Gross recognized? This book argues that the political work of individuals such as Eldridge Cleaver, and organizations such as the Youth International Party (Yippie) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) may in fact mark the emergence of a different approach to political dissent. Rather than dismissing these individuals and organizations for having missed the point of Black Power, the counterculture, or the gay liberation movement, I suggest that they may instead be understood as efforts to negotiate the challenges of presenting radical politics at a time when, as Brustein and others pointed out, the possibility of opposition appeared to have been historically foreclosed. To reframe these political tactics, I place the visual and verbal media games of Cleaver, the Yippies, and the GAA next to the contemporary social and cultural analyses of a number of their critics, each of whom was, in his or her own way, perplexed by the crisis of theatricality that Brustein described. Black Panther Party founder Huey Newton, documentary filmmaker Norman Fruchter, countercultural theorist Theodor Roszak, and film critic Parker Tyler—all politically progressive, these authors worried at length over the damage that activists like Cleaver, the Yippies, and the GAA might do to the various causes they advocated. At the same time, however, each author recognized that the way in which the dominant social order seemed only to thrive on images of opposition also jeopardized the very possibility of meaningful dissent, at least as traditionally performed. Faced with this predicament, each one argued in his own way for the importance of what one might call a nonrepresentational politics, that is, the enactment of a “real” alternative in the present.4 Thus, to give but one example, in contrast to the media games of Abbie Hoffman, which seemed only a juvenile provocation of authority, Roszak celebrated the “authentic” sexuality, the “free love,” as it were, of the counterculture.

But was it really so simple? Was there really nothing more to the Yippies’ media mythmaking than childish pranks? Had Cleaver really mistaken his rhetoric of armed revolution for an actual uprising? Had the GAA, by employing media “zaps” to call for gay rights, turned the fight for gay liberation into a modest proposal for social reform? Put differently, one might ask, as many did, if each of these individuals and organizations had “sold out” their particular struggles, allowing a legitimate, systemic critique to be co-opted. When approaching their work in terms of the aesthetic, the very aspect that so bothered Brustein, those acts that seemed so thoroughly compromised begin to look quite different. After all, as others have noted in discussions of contemporary art and culture, it was in the 1960s that the very oppositions that had structured so much thinking about politics, the avant-garde, and so on—radical/compromised, alienation/assimilation, outside/inside—became far less stable than had been previously assumed.5 Thus, for example, the artist’s desire to “detach” himself or herself from society and mass culture in an effort to focus solely on his/her chosen medium, so famously described in 1939 by critic Clement Greenberg, appeared to have withered. In place of the hermetic practices of the “avant-garde” there emerged a new generation of artists willing to truck with the objects and images of popular culture.6 Beer cans, comic books, Coca-Cola bottles, pin-up girls—all surfaced, seemingly untransformed, in the work of artists such as Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and Mel Ramos. Whether this changing cultural/political perspective was grounded in the collapse of colonialism, as Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have argued; the transition to “late capitalism,” as proposed in Fredric Jameson’s classic essay; or any other constellation of historical conditions and events, it is nevertheless clear that, in writing the history of “the sixties,” any attempt to oppose “real” politics to its co-opted imitation will most likely run into serious difficulties.7

At the same time, however, these more recent discussions of the collapse of clear political oppositions tend to view this as cause for hope or lament. In the case of Hardt and Negri, for example, the end of any notion of a position that truly stands outside of or removed from the dominant political and cultural formation has given rise to a sense of the “common”—both the collectively produced experiences, languages, and affects that have been expropriated or privatized for the good of the neoliberal “free market,” and the shared experience of life in this economic era. Recognizing the true significance of the common, they argue, will be the necessary first step toward the creation of a truly humane, and truly democratic social order. For Jameson, in contrast, the breakdown of any clear notion of opposition has brought us to an impasse, one in which our ability not just to speak politically but even to determine our position and thus orient ourselves in relation to the current crisis has been critically impaired. Faced with a world in which our sense of history has been largely erased, one in which events, images, styles, and so on, seem to stretch out before us simultaneously, interminably, we have become overwhelmed, caught up in the effective “schizophrenia” of the “hysterical, or camp sublime.”

I am neither so optimistic, nor so anxious. Instead, in the pages that follow I would like to begin to think of this sense of collapse itself as something of a historical phenomenon, while maintaining, at the same time, a sense of the conflict, the antagonism, that was, nevertheless, always present. For that is the fascinating irony—one might say contradiction—that seems to have driven the individuals and organizations discussed herein: the sense that all conflict has been evacuated, stripped of its true significance, even in the face of profound bloodshed, oppression, and exploitation. Something had to be done, and yet, as all antagonism seemed to be neutralized as a simple matter of differing opinions, as the real seemed to have given way to an endless series of images, no one could say just what that something was. On this note, I would like to make clear that my goal in revisiting and reinterpreting the work of the Yippies, the GAA, and Cleaver is not to suggest that the late 1960s marked the point in American political history at which grassroots organizational efforts had to be left behind in favor of the politics of imagery and media performance. The reader should not be left feeling, in the end, as if s/he has to choose between being an “old-fashioned” protester and a mythmaker. This kind of simple, contrarian reversal of calls for “real” politics would hardly be worthwhile. It is not my intention to offer a set of simple oppositions between competing political strategies, fetishizing one as “progressive” and dismissing the other as passé. That is precisely the type of argument I hope to problematize. For as the thinkers and activists discussed in the following chapters demonstrate, the politics of mythmaking was not so much an effective solution but an exploration of what seemed a disavowed paradox at the heart of much contemporary thinking about political activism, namely, that all calls for “direct” action proceeded according to formal conventions determined largely by the media. This book, in other words, is not a story of “good” ironic performance’s victory over “bad” grassroots organizing—and, by extension, a hopeful gesture toward the inevitable end of domination in all its forms—but an invitation to consider the difficulties that face political movements in our time and the historical moment in which a number of individuals and organizations seemed to engage those difficulties in an unexpectedly self-conscious manner.

Paying particular attention to the problem of political representation, of politics as representation, this book seeks to read “the sixties” anew, drawing on the theoretical frameworks developed more recently in fields such as visual culture and performance studies, among others, to rethink the practices employed by those claiming to act in the name of an existentialist-inspired “personal authenticity.” In the chapters that follow it will become quite clear that without the work of authors such as Peggy Phelan, Craig Owens, Sue-Ellen Case, Judith Butler, Homi Bhabha, José Muñoz, Matthew Tinkcom, and others, this project may never have been conceived. As Jonathan Dollimore points out, however, these more recent debates over the prospect of a performance-based politics are possible only “because theoretical insights have already been struggled towards by thinkers, writers, activists, and others in specific historical and political struggles where the representative structures of oppression have been massively (if still only ever contingently) in place.”8 With this in mind, I have chosen to focus less on the writings of contemporary theorists than on the works of writers and thinkers of the period. For this reason, three authors in particular will provide the historical and conceptual framework for much of what follows: Herbert Marcuse, Susan Sontag, and Jacob Brackman. In the years between 1964 and 1971, each of these writers attempted to theorize the political ramifications of what they saw as a social and cultural order that had rendered personal authenticity meaningless. Throughout the 1960s Marcuse attempted to describe the historical, dialectical relationship between the flourishing of personal liberty on one hand, and the death of “real” opposition on the other. In works like One-Dimensional Man and “Repressive Tolerance,” he argued repeatedly that “technological society” had succeeded in reconciling desire with the commodity form. From sex to works of art, virtually all of the forms that had once expressed individual dissatisfaction with society had been colonized, circumscribed by a social order that sought to eliminate opposition through a spurious tolerance.

Marcuse’s argument concerning “one-dimensional” society’s conquest of “higher culture” leads to a reconsideration of the contemporary writings of Susan Sontag, who, in her essays on art and camp, struggled repeatedly with notions of authenticity and theatricality in the context of American culture. Not unlike Marcuse, whose influence she openly acknowledged, Sontag wanted desperately to foster what she called an “erotics of art,” a form of direct experience that would distance the viewer from an era dominated by an overwhelming tendency to separate form from content, and to understand “Being-as-Playing-a-Role.”9

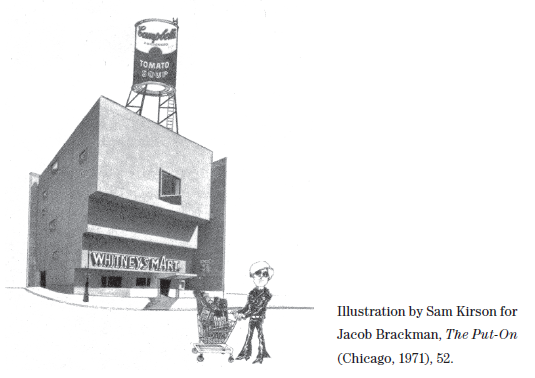

Finally, I will turn to the work of film critic Jacob Brackman, whose 1971 text The Put-On constituted an attempt to comprehend the rapid proliferation of what Sontag called the “Camp sensibility.” Where in 1964 Sontag had written that practices of camp were almost the exclusive province of “homosexuals,” by the late 1960s, according to Brackman, the popularization of these practices had made it difficult to take any statement at face value. The put-on, a mode of inauthentic self-presentation based in the performance of stereotypical identities, had become the basis for an almost standardized form of (mis)communication. By placing these analyses next to one another and using them to reframe the political careers of Cleaver, the Yippies, and the GAA, this book demonstrates that the very theatricality decried by Brustein, Gross, and others might be read not as an indicator of utter political impotence but as a series of critical inflections of the increasingly problematic language of “real” politics. Rather than attempting to separate the political from the aesthetic, I seek here to investigate the extent to which a great deal of sixties activism revealed each to be unthinkable without the other.

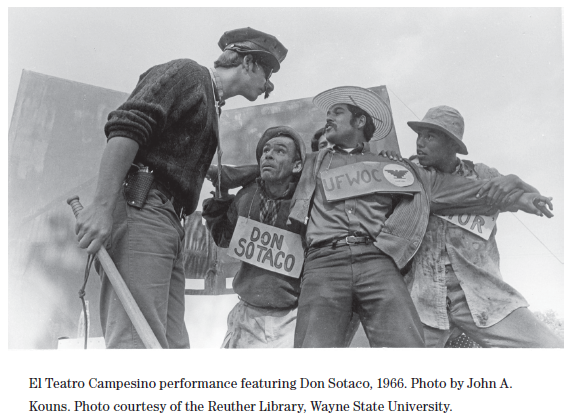

For Brustein, political activism in the United States had reached a dead end because the United States lacked the “adequate machinery for the redress of grievances and for social change.”10 As a result, those who found themselves marginalized by the dominant social order could do little more than stage “ineffective” or minimally disruptive demonstrations. Political opposition had been successfully channeled, he argued, because rather than squelching differing opinions American society had welcomed them. Dissent had been smothered by an overwhelming permissiveness. Unlike earlier periods, when an author may have suppressed a work to avoid provoking the authorities, playwrights in 1970 were “more likely to shelve their works for fear of displeasing the revolutionary young.” Consequently, “Anti-Vietnam war plays have become a cliché, and black dramatists indict white audiences weekly from the stages of establishment theaters.”11 It was in no way surprising, that is, to see a play like Hair go from Joseph Papp’s experimental Public Theater in the East Village to Broadway within a mere six months. Nor was it any longer unusual to find that groups such as El Teatro Campesino and the Black Revolutionary Theater, both of which were founded as guerrilla theater troupes in 1965, had by the end of 1970 earned critical acclaim, bookings on conventional stages, and upper-class, white audiences. Simply put, it had become virtually impossible to provoke theater-goers’ outrage—a problem lampooned in Brian DePalma’s 1970 film Hi Mom!, where well-dressed white men and women are frightened yet exhilarated when painted black, berated, and abused by black radicals in whiteface during the performance of a play called Be Black, Baby.12 For Brustein, like many others, it was one thing to stage “actos” for United Farm Workers picket lines, or to compose something like street happenings for young black actors, or even to condemn the war in small, off-Broadway venues. But when productions of La Conquista drew praise from white theater critics, or when LeRoi Jones and the Black Arts Repertory Theater School accepted government funding, one could not help but suspect that something was amiss.

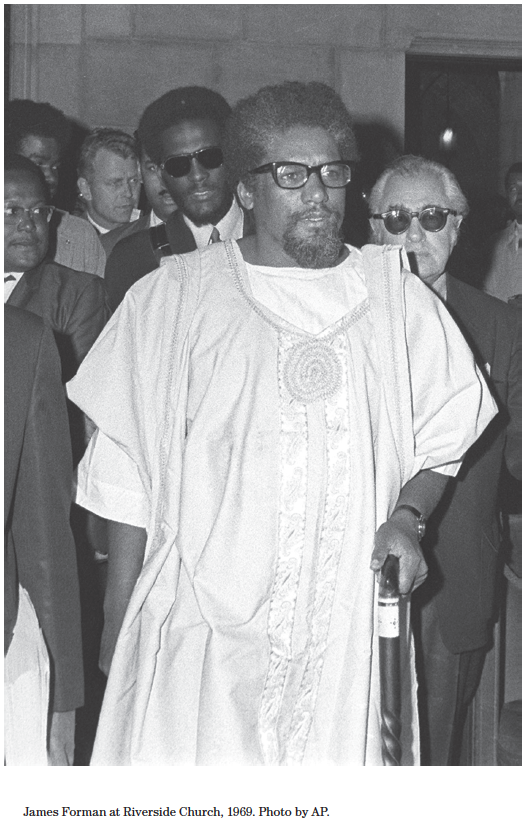

In the end, however, for Brustein, more disturbing than the effects of this permissiveness in the theater were its consequences in the realm of politics. Though they claimed to be wary of any false sense of liberation, militants and radicals quickly latched onto these “extended verbal freedoms” all the same. Given the mass media’s hospitality toward radical ideas and opinions, the result of this “muscle-flexing and tub-thumping” was “not revolution but rather theater.” When, for example, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee spokesman James Forman, or Sonny Carson of the Congress of Racial Equality interrupted church services and community meetings to demand racial justice, reparations, and so on, “then we know that the incidents have been staged for the newspaper reporters and television cameras, and should, therefore, be more properly evaluated by aesthetic standards than by political criteria.”13

According to Brustein, these performances, however “revolutionary” they might have appeared, served only to obscure the “real” issues. The only hope for change, he argued, was to be found in moderation, in “conceding that revolution in America is a stage idea, and turning away from these play actors of the ideal . . . writing off the radical extremes of the current younger generation, and trying to cultivate the genuine warmth and decency that this generation still retains.”14

Like many at this time, Brustein borrowed a great deal from the contemporary writings of Herbert Marcuse. For Marcuse, by the late 1960s, traditional political actions—petitions, marches, sit-ins, and so on—had been rendered almost entirely ineffectual. In his 1966 essay “Repressive Tolerance,” for example, despite a few closing comments regarding possibilities for qualitative change, Marcuse’s tone conveys an unmistakable despair. The “abstract tolerance” of American liberal democracy—abstract “inasmuch as it refrains from taking sides”—offered nothing, he claimed, but a mockery of “true” tolerance.15 Although contemporary cultural and social institutions allowed all sides of a given debate to be heard, “the people,” called upon to evaluate contrasting positions, had been rendered incapable of making crucial distinctions between differing points of view. The tolerance that was said to have made individuals “free” had in fact subjugated them. They were able only to “parrot, as their own, the opinions of their masters.”16 What appeared to be tolerance was little more than a mirage.

The mass media, of course, were instrumental in perpetuating the myth of a thoroughly democratic political culture.17 The press no longer played the role of the “fourth estate” but functioned instead to legitimate the existence of concrete social inequity. This was the result not of some conspiracy but of the “‘normal course of events’ . . . and . . . the mentality shaped in this course.”18 A general acceptance of inequality meant that restrictions on the media had become virtually unnecessary. In the media, “the stupid opinion” could be “treated with the same respect as the intelligent one, the misinformed may talk as long as the informed, and propaganda rides along with education, truth with falsehood.”19 This apparent objectivity could be afforded because nothing was at stake. Indeed, the potential persuasiveness of the “intelligent,” “informed” opinion had been preempted. Value judgments, Marcuse argued, had been placed on all opinions prior to their articulation. But what made the mass media so harmful was the assumed naturalism of their representations. When combined with the unspoken bias of the dominant culture, he wrote, “such objectivity is spurious—more, it offends against humanity and truth by being calm where one should be enraged, by refraining from accusation where accusation is in the facts themselves.”20 The media’s “objectivity” had succeeded only in isolating the vast majority of the public from its “political existence.” Individuals had been stripped of any sense of the potential social importance of their actions. “Real opposition” had been replaced by “the satisfactions of private and personal rebellion.”21 One could do or say virtually anything without posing a significant threat to the status quo. “The publicity of self-actualization,” as he put it, “encourages nonconformity and letting-go in ways which leave the real engines of repression in the society entirely intact.”22 Actual rebellion had been replaced by formulaic expressions. In the name of self-fulfillment individuals had allowed themselves to be nullified, subsumed within a social order that only worked against their best interests.

As some readers will have recognized, Marcuse had lain the groundwork for this theory of “repressive tolerance” in his 1964 book One-Dimensional Man. There he asserted that contemporary society was “irrational as a whole.” It was a “society without opposition,” one in which citizens submitted to the “peaceful production of the means of destruction, to the perfection of waste, to being educated for a defense which deforms the defenders and that which they defend.”23 Marcuse never denied that difference endured in this society, but the oppositionality necessary for dialectical thought, and thus for any meaningful, radical transformation, had essentially vanished. “The manifold processes of introjection seem to be ossified in almost mechanical reactions,” he wrote. “The result is, not adjustment but mimesis: an immediate identification of the individual with his society and, through it, with society as a whole. . . . In this process, the ‘inner’ dimension of the mind in which opposition to the status quo can take root is whittled down. . . . The impact of progress turns Reason into submission to the facts of life, and to the dynamic capability of producing more and bigger facts of the same sort of life.”24 Contemporary society had eradicated virtually any trace of its underlying contradictions. Difference, promoted only to enhance the illusion of inclusiveness, had ceased to be meaningful. One of the ways in which this could be seen most clearly, Marcuse believed, was in the liquidation of oppositionality from the realm of “higher culture.”

In one-dimensional society, the elements of “higher culture” that had once enabled it to stand against the dominant social reality had been expunged. This was not because the content of art had somehow been “watered down,” but because artworks had been reproduced and distributed on a mass scale. Rather than delivering the potential liberation that Walter Benjamin saw in its mechanical reproducibility, mass culture, according to Marcuse, had done just the opposite. It had succeeded in its conquest of individual consciousness by claiming to have delivered the happiness to which it once only alluded. Unlike the “true” work of art, whose promesse de bonheur was invariably, necessarily deferred, the products of mass culture presented themselves as the real fulfillment of individual desires. One-dimensional culture thus appeared to have eliminated the social strictures that had produced the work of “higher culture” as a necessary form of sublimation in the first place. Art had once been meaningful precisely because it was in some important way removed from the demands of profitability. But one-dimensional society had rendered this mode of culture obsolete by blending “harmoniously, and often unnoticeably, art, politics, religion, and philosophy with commercials.”25 It brought these different cultural practices, along with the individuals responsible for them, into alignment with their common historical denominator: the commodity form. Sublimation no longer seemed necessary, therefore, for the desires of the individual appeared to have been accommodated within the social order they contradicted. They had been reconciled with the society that once worked to exterminate them. The utopian promise of art had been superseded by suggestions of a utopia achieved within mass culture. In this context, the modern artist’s statements of alienation were transformed, becoming little more than advertisements for the status quo.

Susan Sontag, writing at roughly the same time, placed the blame for this problem squarely on the shoulders of the critic. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, she argued, the relationship between the critic and the work of art had reached an impasse. Simply put, critics no longer felt compelled to respect art’s objectivity. “In most modern instances,” she wrote, criticism simply rendered works of art “manageable, conformable.”26 By interpreting aesthetic works the art critic implicitly assumed that form and content were somehow distinct, thereby doing violence to the work itself; interpretation, as Sontag put it, “violates art.”27 In response to this critical aggression modern artists had actively thwarted any and all attempts at interpretation by appealing directly to the senses. These artists looked to “elude the interpreters . . . by making works of art whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be . . . just what it is.”28 Among the examples Sontag listed of this new, more insistently present work were the Theater of Cruelty of Antonin Artaud, the Happenings of Alan Kaprow, the novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet, and the films of directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard, and Robert Bresson. The value of these works, in her estimation, was that they defied translation. They forced one to acknowledge the work’s “pure, untranslatable, sensuous immediacy . . . and its . . . solutions to certain problems of . . . form.”29 Yet directness was not the only means of forestalling the incursion of interpretation. In fact, Sontag argued, certain forms of indirectness could achieve the same end. In contrast to the brute materiality of the Theater of Cruelty, Pop Art had used “a content so blatant, so ‘what it is,’” that it too defied any attempt to translate/domesticate the work of art. Upon introducing this idea of Pop Art’s indirectness as a potential form of immediacy, however, Sontag ran head-on into the very same historical dilemma that so vexed Marcuse, namely, that claims to aesthetic “immediacy,” whether direct or indirect, were inherently reconcilable with the demands of consumer capitalism.

That Sontag eventually stumbled over this problem should come as little surprise, for the urgency with which she pressed for a critical “erotics of art” was based, primarily, in the reformulation of psychoanalysis advanced by Marcuse and Norman O. Brown in the 1950s. Brown and Marcuse, Sontag wrote, were two of the first thinkers to give some indication of the “revolutionary implications of sexuality in contemporary society.”30 Like them, Sontag believed that Freud’s theories of sexuality were deeply, inherently political. In Eros and Civilization, published in 1954, Marcuse had argued that Freud’s belief that human culture is necessarily repressive amounted to little more than a defense of the status quo. The repression Freud saw as integral to any orderly and efficient society was, for Marcuse, “surplus repression,” the subordination of individual desires and impulses to the demands of industrial capitalism. The corrective to this surplus repression was to be found, he argued, in revisiting and recovering the developmental state of “polymorphous perversity,” in which eroticism was not restricted to the genitals. By re-eroticizing and accordingly reconfiguring the entire human organism, we might release the body from the type of instrumentality demanded by industrial society.31 Similarly, in his 1959 text Life Against Death, Brown called for the reunification of mind and body. Unlike “revisionist” American Freudians, he believed that psychoanalysis held the key to healing both society and the individual. This would be achieved not through the reeducation of the mind, but through the recognition of the mind’s dependence upon the body. If the primacy of the body could be acknowledged, and an androgynous mode of existence accepted, Brown believed that the neuroses resulting from sexual differentiation and “genital organization” could be overcome. As Sontag summarized his argument, “The core of human neurosis is man’s incapacity to live in the body—to live (that is, to be sexual) and to die.”32 Much like the theory of art presented in Eros and Civilization, Sontag’s “erotics of art” was to constitute a move toward this re-eroticizing of the individual. For Sontag, that is, the attempts to reeducate the senses found in the works of Artaud, Kaprow, Antonioni, and others were not just aesthetic obligations but social imperatives. Through the direct experience of these works and their material refusal to submit to the demands of “critical” thought, she believed that individuals could be transformed. But the “Surrealist sensibility” that functioned through these works had also given rise to the “cooler” works of Pop artists like Andy Warhol. Like Surrealism, both of these newer forms sought to “destroy conventional meanings” and to create new ones through the use of “radical juxtaposition.”33 For Sontag, however, where Kaprow and Artaud had actively challenged viewers’ senses and sensibilities, Pop Art had ultimately looked only to entertain them. Warhol, therefore, was merely the legatee of those surrealists who made it fashionable for the French intelligentsia to frequent flea markets. The particular form of “disinterested wit and sophistication” in which he specialized may have stymied critical interpretation, but it nevertheless failed to acknowledge the more urgent task facing the artist, namely the personally and socially “therapeutic” work of “reeducating the senses.”34 Simply put, Pop Art was plagued by its dependence upon the more insidious form of the Surrealist sensibility known as camp.

The “Camp sensibility,” in Sontag’s phrasing, was not a way of changing the world through aesthetic experience but rather “of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon.”35 Unlike the corrupted aesthetic Marcuse saw in mass culture, in which everyday images and objects presented themselves as truly fulfilling, the camp sensibility found in the world an image of failure. In her “Notes on Camp,” published in 1964, Sontag wrote that camp was “the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things being-what-they-are-not. . . . Camp sees everything in quotation marks. . . . To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role.”36 Unfortunately for Sontag, the “Camp sensibility” proved exceedingly difficult to pin down for this very reason. Following a few introductory remarks on the necessity of understanding camp as a sensibility, she literally reversed her position. “Not only is there a Camp vision, a Camp way of looking at things,” she wrote, “Camp is as well a quality discoverable in objects and the behavior of persons. . . . It’s not all in the eye of the beholder.”37 To access the “Camp sensibility,” it seems, Sontag felt it necessary to work backward from “campy” objects—things such as Tiffany lamps, the National Enquirer, Flash Gordon comics, and the famous Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles. By looking to “the canon of Camp,” she believed it would be possible to extrapolate those characteristics that appealed to—and conditioned—“the Camp eye.”38 Through a brief survey of these objects, she surmised that camp could not be overly serious, overly important, or overly good: “Many examples of Camp are things which, from a ‘serious’ point of view, are either bad art or kitsch.”39 The camp object was one that proclaimed, whether naively or consciously, its own silliness, extravagance, or artificiality. It was an object in which form and content failed to coalesce. Like Baudelaire’s concept of the “significative comic,” the camp object was “visibly double.”40

But it was the relation of camp’s practitioners—as opposed to its objects—to another of Baudelaire’s concepts that Sontag found more worrisome. As she understood it, camp amounted to the reformulation of dandyism for the world of mass culture. Its intimate ties to mass culture, however, had effectively expunged the dandy’s “quintessence of character and . . . subtle understanding of the entire moral mechanism of this world.”41 In place of this character and understanding was mere “aestheticism.” Camp’s affected pleasure in the imperfections of the everyday was thus nothing more than the latest moment in the “history of snob taste.”42 More importantly, though, camp had only taken hold at a moment when “no authentic aristocrats in the old sense exist . . . to sponsor special tastes.”43 In the absence of a true upper class “an improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals,” had come to serve as the “aristocrats of taste.”44 Camp’s appreciation of the mundane, its celebration of the art of the masses, could never have been mistaken for a truly populist—or even avant-garde—project. Rather, it was precisely the opposite.45 Unlike “true” artists, those who appreciated camp were virtually incapable of developing any deeper understanding of the world. Rather than providing a challenge to critical thought, they had merely inverted its standards.

Once again, though, for Sontag, the most profound challenge to critical thought would proceed through the senses rather than the intellect. It was for this reason, among others, that when faced with camp she experienced a “deep sympathy modified by revulsion.”46 In one sense, the “Camp sensibility” actively thwarted any attempt at easy interpretation—hence her decision to approach the phenomenon through a series of “notes” rather than attempting to fix its meaning in an essay. Yet, at the same time, the paradoxical immediacy of campy objects appeared to hold no social or political promise. To the contrary, camp seemed to render the notion of sensuous immediacy virtually nonsensical. As she observed, “Camp . . . makes no distinction between the unique object and the mass-produced object. Camp transcends the nausea of the replica.”47 Camp’s emphasis on surface and the presentation of self as performance, in other words, was not an attempt to foreground the tensions that might be contained within those surfaces and performances but a clever way of accepting, or even celebrating, them. The camp sensibility delighted in images rather than interrogating them. Her accusation of “aestheticism,” therefore, opposed camp not to reality but to the modernist notion of the work of art as a vehicle for critique.

Moreover, what made camp so repugnant was that its effects were virtually inescapable, so much so that Sontag feared her own attempt to define the “Camp sensibility” would result only in “a very inferior piece of Camp.”48 In spite of her efforts to avoid this fate by approaching camp obliquely, through a series of notes, her attempt to distinguish camp from non-camp ended in failure all the same. This is because in her search for the “contemporary Zeitgeist,” as Fabio Cleto has argued, Sontag linked camp “through a paradoxical combination of ‘aristocratic’ detachment and ‘democratic’ leveling of social (and cultural) hierarchies, with the dandification of the . . . masses producing ‘the equivalence of all objects,’ and the transcending of the romantic disgust for the replica, be that the parodic repetition or the infinite technological reproducibility of an original which no longer holds its epistemic privileges.”49 Sontag, in other words, presented postwar America as a culture plagued by a series of crucial indifferences regarding foundational concepts such as originality, objectivity, and aesthetic quality. The revulsion Sontag felt in response to the camp sensibility may have been rooted in a wish to reinstate the work of art in all its sensuous immediacy, but, as Cleto suggests, it was the obsolescence of this type of immediacy to which camp alluded. Camp thus revealed the social aspirations of formalist criticism to be a farce. The sociohistorical conditions that had given birth to camp as a phenomenon had left nothing untouched. Everything, to paraphrase Sontag, had been placed “in quotation marks”—not by camp but by the historical conditions of its emergence. As a result, the grounds from which critique might proceed seemed to have crumbled beneath her feet. Camp was not the opposite of modernist artistic practice but an indication of its collapse. The circumstances that Sontag saw giving rise to the “Camp sensibility” were thus the same as those that had allowed, in One-Dimensional Man, for the apparent reconciliation of art and society. These were the same conditions, moreover, that Marcuse believed had brought about the “repressive desublimation” of human sexuality.

In One-Dimensional Man, Marcuse argued that desublimation, as it existed in contemporary culture, was truly injurious to the individual. It “weaken[ed] the necessity and the power of the intellect, the catalytic force of that unhappy consciousness . . . which recognizes the horror of the whole in the most private frustration and actualizes itself in this recognition.”50 Where the work of art had once served to register one’s dissatisfaction with the social order—an idea that served as the cornerstone of modern art criticism—the technological society’s ultimately enslaving reconciliation of art and mass culture had left the individual incapable of recognizing his or her own unhappiness. Any sense of emancipation one felt within one-dimensional society was nothing more than that society’s “conquest of freedom.” And, much like the artist, whose statements of alienation had become easily assimilable, those who attempted to flout the rules of this social order succeeded only in strengthening its grasp: “Zen, existentialism, and beat ways of life, etc. . . . are no longer contradictory to the status quo. . . . They are rather the ceremonial part of a practical behaviorism, its harmless negation, and are quickly digested by the status quo as part of its healthy diet.”51 Rebellion had been reduced to a set of signifiers so that it might become the ultimate in conformity. Even sexual perversion, which in Eros and Civilization was said to be essentially irreconcilable with a society that attempted to subjugate all activity to the logic of labor, had been successfully co-opted. One could “let go,” as it were, while leaving the “real engines of repression” entirely intact. Asking the reader to compare “love-making in a meadow and in an automobile, on a lovers’ walk outside the town walls and on a Manhattan street,” Marcuse explained that in the former situations, “the environment partakes of and invites libidinal cathexis and tends to be eroticized. In contrast, a mechanized environment seems to block such self-transcendence of libido. Impelled in the striving to extend the field of erotic gratification, libido becomes less polymorphous, less capable of eroticism beyond localized sexuality, and the latter is intensified.”52 The body’s increased sexualization had precluded its true re-eroticization. Perversion, desublimated only to be safely compartmentalized as a leisure activity, no longer upheld the possibility of the erotic as an end in itself. Yet the nausea of the replica, to paraphrase Sontag, seemed to have been transcended.

I will explore the relationship between eroticism and liberation in Marcuse’s thought in greater detail in the next chapter. For now, I want only to stress that, while Marcuse had not abandoned all hope for a radical, total revolution, the source from which that revolution might spring was difficult to identify. Art, sexuality, alternative ways of life: nearly all forms of opposition had been rendered easily assimilable. Compelled nevertheless to designate a source of potential social transformation, he turned to what he called the “substratum” of the technological society, “the exploited and persecuted of other races and other colors” who lived “outside the democratic process.” Given their direct and “immediate” relationship to the failure of American political institutions, the way in which their plight seemed to emblematize the failure of those very institutions, their opposition to authority was “revolutionary even if their consciousness was not. . . . it is an elementary force which violates the rules of the game and, in doing so, reveals it as a rigged game. . . . The fact that they start refusing to play the game may be the fact which marks the beginning of the end of a period.”53 For Marcuse, in other words, the experience of racial oppression provided the critical distance necessary for true critique. Writing in the early 1960s, he praised civil rights activists for their courage. The power of their willingness to “face dogs, stones, and bombs, jail, concentration camps, even death,” he wrote, lay “behind every political demonstration for the victims of law and order.”54 By the time “Repressive Tolerance” appeared, however, his perspective had changed slightly. There he wrote that “the exercise of political rights (such as voting, letter-writing to the press, to Senators, etc., protest demonstrations with a priori renunciation of counterviolence) in a society of total administration serves to strengthen this administration by testifying to the existence of democratic liberties which, in reality, have changed their content and lost their effectiveness.”55 The turn in Marcuse’s thought clearly reflects the public transition from the nonviolent civil rights movement of the 1950s and early 1960s to the openly confrontational politics of Black Power, but the potential catalyst for a true historical transformation remained in the oppositional strategies of “other races and other colors.” Although the willingness to face dogs, stones, bombs, and so on was no longer sufficient, in the face of a virtually totalizing system of repressive tolerance, racial minorities apparently maintained an element of purity and authenticity otherwise lost. Race, in other words, had supplanted perversion as the true lever of social change. Perhaps Marcuse believed that its “indelible” visibility, an enduring reminder of the persistence of concrete inequality, served to render race ultimately unassimilable. Or, given his reference to the “immediate,” “elemental” character of racial opposition, one might read in this attempt to posit a source of revolutionary consciousness a patronizing reverence akin to that of Norman Mailer’s “White Negro.” But whatever the justification, the racial identities that Marcuse saw as perhaps the last hope for radical opposition were, like the forms of “non-conformity and letting go” he dismissed, far less “immediate” than he assumed. In fact, as Jacob Brackman argued, the figures of the “assimilationist” civil rights activist and the militant black liberationist, along with the rhetoric of Zen, existentialism, and beat ways of life, had already been appropriated and redeployed by the practitioners of a satirically campy mode of miscommunication known as “the put-on.”

The put-on, a seemingly playful, aimless conversational misdirection, was not necessarily new. What was new, and troubling, was its inescapability. Although it had once been only an in-group, “outlaw form,” over the course of the 1960s the put-on had become virtually ubiquitous. What was previously “an occasional surprise tactic—called ‘joshing’ around the turn of the century and ‘kidding’ since the twenties,” Brackman wrote, had been “refined into the very basis of a new form of communication.”56 From Warhol’s Brillo Boxes to the maddeningly nonsensical cat-and-mouse interviews given by Bob Dylan, some unsuspecting “victim” was being confounded by a put-on almost everywhere one looked. As Warhol told Gretchen Berg in a 1966 interview ironically titled “Andy Warhol: My True Story,” “I never like to give my background and, anyway, I make it all up different every time I’m asked”57—this, one presumes, was how Andy “put his Warhol on.”58 Similarly, the unapologetic fusion of high art and pop culture one found in his paintings, sculptures, and events such as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable left one uncertain whether this work was truly progressive, or if museums and galleries had simply been reduced to little more than glorified supermarkets. The put-on had thus necessitated a fundamental shift in the way audiences approached the latest works. Viewers had come to assume that a great deal of contemporary work sought to engage them not in some type of purely sensual communion but in an elaborate “con game.” In response, Brackman suggests, critical arguments seemed to shift from determining what qualified as a “good” work to what constituted a “real” work. In this situation, of course, when a critic dismisses “something that others have considered good, he is no longer simply challenging the merits of a specific work; he is telling the public that his colleagues have been taken in by fraud, that they are hoodwinked in their notions of what constitutes art, that none of us really knows for sure anymore what is real and good.”59

To be sure, if this had remained the problem of a few art critics, it would most likely have merited relatively little discussion. What made the unavoidability of the put-on interesting was precisely the fact that it was not merely the problem of determined formalists. The put-on’s cynical irony had tainted virtually every interpersonal exchange. One did not simply reenter the realm of sincerity by stepping outside of the gallery. And, quite interestingly, this proliferation of the put-on had begun, according to Brackman, with Sontag’s attempt to define camp. Her “disjunct essay in Partisan Review,” he wrote, “was read by tens of thousands, but its reverberations affected the culture consumed by hundreds of millions.”60 Whether the popularization of these ideas was actually rooted in the appearance of Sontag’s “Notes” is debatable. After all, Erving Goffman had begun to speak of self-presentation as a type of performance in 1959, and Pierre Bourdieu, writing in France in 1965 of the poses commonly struck in pictures, asserted that the photographic representation of society could only ever be “the representation of a represented society.”61 Nevertheless, for Brackman it was clear that what had once been preserved within the “classy preconscious” of American culture had, in the second half of the 1960s, surfaced as a part of the popular consciousness. In the process, critical judgment had been “clog[ged]” and aesthetic standards “scuttle[d].”62 Although Sontag “had been describing a method of appreciation, her rules were embraced as principles of manufacture.”63 Long before Madonna “struck a pose” and introduced a mass audience to voguing, the put-on had popularized the theatrically queer sensibility of camp. In the process, Brackman argued, that sensibility had been turned into a series of pointless, cruel jokes.

The cruelty of these jokes lay in their conscious effort to render virtually all communication suspect. While the “Camp sensibility” more passively viewed being as playing a role, the “put-on artist” intentionally evoked the citational aspect of every statement. For this reason, “conversation with a put-on artist is a process of escalating confusion and distrust. He doesn’t deal in isolated little tricks; rather, he has developed a personal style of relating to others that perpetually casts what he says into doubt. The put-on . . . is rarely climaxed by setting the truth straight.”64 Unlike irony, the put-on worked through the exchange of disinformation. The content of the ironic utterance or gesture, according to Brackman, was essentially fixed; it expressed the opposite of that which was said or done.65 Strictly speaking, therefore, misunderstanding marked the failure of irony. The put-on, on the other hand, “inherently cannot be understood.”66 The “put-on artist,” speaking from no fixed position, refused only to be pinned down. Always one step ahead, through a potentially infinite series of evasions s/he foregrounded the indeterminacy of her/his statements, leaving interlocutors utterly confounded. Most importantly, however, specific examples would nearly always assume one of two forms: “relentless agreement” or “actualization of the stereotype.”

Relentless agreement required the put-on artist to assume her/his opponent’s position. In this situation, Brackman explains, “the perpetrator beats his victim to every cliché the latter might possibly mouth,” thereby pulling the rug from beneath the “victim’s” feet.67 For example, when a “straight . . . but enlightened man, evincing his enlightenment,” asked a young gay man to explain the roots of same-sex attraction, the young man might sound almost apologetic, responding, “Why, of course it’s a sickness, there’s no question. Take me. My father was weak, henpecked. It’s psychological. My mother wouldn’t let me wear long pants till I was fourteen. And then the Army. Well, you know. It’s better than animals. My analyst thinks I’m progressing toward a real adjustment.”68 In contrast, the method of actualizing stereotypes was, at least on its surface, more openly hostile. There, “the perpetrator personifie[d] every cliché about his group, realize[d] his adversary’s every negative expectation: He [became] a grotesque rendition of his presumed identity.”69 In conversation with a “benevolent progressive,” to use another of Brackman’s examples, a “militant Negro” might say, “Don’t make your superego gig with me, ofay baby. Your graddaddy rape my grandmammy, and now you tell me doan screw your daughter? . . . don’t offer me none of the supreme delectafactotory blessings of equalorama, ’cause when this bitch blows you gonna feel the black man’s machete in the soft flesh of your body, dig?”70 For Brackman, however, regardless of the perpetrator or the form, the result of gestures and actions such as these was always the same. The put-on made it impossible to determine just where the put-on artist stood. Rather than eventually revealing her/his “true” position, the put-on continued indefinitely, ultimately suggesting the impossibility of any “true” position. Both sides of the presumed debate were thus exposed as clichés or performances in themselves, and the entire conversation was set adrift.

It is fitting, then, that at the center of Brackman’s attempt to define the put-on, much as in Sontag’s efforts to discuss camp, one finds a fundamental ambivalence. The put-on was naïve, or even politically regressive, Brackman argued, because it proceeded from the basic assumption that the forms of dominant culture could be used against themselves. In spite of its ability to denaturalize existing social positions and relations, the put-on nonetheless remained ultimately reconcilable to that which it destabilized. No matter how “subversive” the put-on might seem, if the “victim” failed to recognize the joke, his or her assumptions were not thrown into question but reinforced. Its exasperating (rather than insurrectionary) confrontations were thus inherently limited. And because of these limitations, Brackman wrote, the put-on was most frequently “employed against the most sympathetic elements among the enemy.”71 Rarely was it used for any purpose other than to confound an individual who might otherwise be persuaded by rational arguments. Police officers, for example, would often be treated with “careful deference,” while a “friendly probation officer or social worker” would be “put on mercilessly.”72 The threat of “real” retaliatory violence, according to Brackman, inevitably caused the put-on artist to lose her/his nerve. For this reason, as far as he was concerned, the put-on was not revolutionary but theatrical. The progression of one-dimensional society thus appeared to have been completed. “Resistance,” taken in by its own ruse, had been successfully colonized.73

Much as Brackman would have liked to dismiss the put-on as nothing more than simple cynicism, however, he was forced time and again to acknowledge the potential oppositionality of these misdirections. At one point he wrote, “Even though it’s really a defensive weapon, the put-on almost always provides an offensive for the questionee, representative of the smaller, more helpless faction, making his group appear In and the larger, more powerful group of the questioner appear Out.”74 The put-on could also be a means of empowering the weak insofar as it tricked the powerful into engaging the essential inadequacy of their own terms. Thus, as a political identity, the “militant Negro” may have been a site of opposition, but not in the sense that Marcuse proposed. The critical edge of this character/caricature lay not in its existence outside the grasp of dominant culture but in its exaggeration of that culture’s stereotypes. Brackman’s analysis therefore pointed to a dilemma overlooked by Marcuse. The political pronouncements of “other races and other colors,” believed by Marcuse to be the site of a potentially powerful opposition, were, according to Brackman, recognized to be thoroughly stereotypical. Rather than simply dismissing these identities for that reason, however, the logic of Brackman’s argument points to the ways in which these stereotypes may have presented a different form of resistance, one that began from a sense of the historical impossibility of transcendence, and thus looked to seed resistance in acts of interpretation.

Looking back on the political activism of the late 1960s with Brackman’s analysis in mind, any number of actions begin to appear different or less settled than they once did. Consider, for example, the work of the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, or WITCH, a loose organization that eventually split from New York Radical Women in the winter of 1968–69. After participating in the bra burnings outside of the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the previous summer, Robin Morgan and friends chose to embody, quite literally, stereotypical notions of feminists as evil or unchristian, dressing in black robes and pointed hats (among other things) to place a hex on Wall Street. That Halloween, to “liberate the daytime ghetto community of the Financial District,” she later wrote,

the Coven, costumed, masked, and made up as Shamans, Faerie Queens, Matriarchal Old Sorceresses, and Guerrilla Witches, danced first to the Federal Reserve Treasury Bank, led by a High Priestess bearing the papier-maché head of a pig on a golden platter, garnished with greenery plucked from the poison money trees indigenous to the area. Bearing verges, wands, and bezants, the WITCHes surround the statue of George Washington on the steps of the building, striking terror into the hearts of Humphrey and Nixon campaigners nearby, who castigated the women for desecrating (with WITCH stickers) the icon of the Father of our Country (not understanding that this was a necessary ritual against a symbol of patriarchal, slave-holding power). The WITCHes also cast a spell rendering the hoarded gold bricks therein valueless—except for casting through windows.75

Using the Republican and Democratic campaigners as their “straight men,” as it were, the WITCHes lampooned both popular clichés about feminism and the dominant forms of American political debate. Was either Humphrey or Nixon really the solution . . . to any of the problems that faced the United States? The fact that supporters of each one considered New York’s Financial District a good place to unearth sympathetic voters certainly suggested otherwise. But beyond this, and more importantly, the action also posed serious questions about the assumed means of addressing what seemed an exceedingly stubborn political impasse.

As Brackman suggested, examples like this are in no way uncommon. The chapters that follow thus present three case studies of political uses of the put-on, illustrating the perceived social utility of the gap between saying and meaning that so preoccupied the film critic. Chapter 1, “Monkey Theater,” will address the group that made perhaps the most obvious and elaborate use of the put-on, the Yippies. In the wake of the riots at the Democratic National Convention in 1968, a number of activists felt a great deal of anger toward Yippie leaders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. Seemingly caught up in their own status as “movement celebrities,” these “leaders” appeared incapable not just of speaking for the movement they called their own but of “speaking truth to power” in any significant fashion. As Todd Gitlin, once a leader of the Students for a Democratic Society, put it twelve years later, “Deprived by resentful constituents of the chance to use the media legitimately as political amplification,” Hoffman and Rubin were cut off from their supposed base.76 Shunned by fellow radicals, the Yippie spokesmen were left to perform ever more outrageous visions of political opposition for viewers they could never hope to influence. This chapter reconsiders the ways in which the Yippies were seemingly co-opted, asking if Hoffman and Rubin were indeed so blinded by their celebrity status that they might have believed that nominating a pig for president was a “revolutionary” act. Were their threats to taint Chicago’s water supply with LSD or to develop a pernicious new sex drug that could be administered to unknowing victims via water pistol anything other than irresponsible publicity stunts? What could it have meant for Hoffman to claim, following the riots in Chicago, that he hoped to fashion himself as a combination of Fidel Castro and Andy Warhol, or to write “FUCK” across his forehead—a move that he initially said would keep anyone from taking his picture—for a studio shoot with fashion photographer Richard Avedon?77 Through an analysis of the Yippies’ various media myths, one begins to see that their tactics may not have been designed simply to provoke the authorities but also to transform the futility of opposition decried by Marcuse, Brustein, Brackman, and others into its own historically specific form of technologically mediated transgression.

Chapter 2 looks to the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance, two organizations that formed in New York following the Stonewall riots of 1969. At first glance, it may seem an odd choice to include the gay liberation movement in the current discussion. After all, not only were activists like Hoffman, Rubin, and Cleaver accused on more than one occasion of homophobia or antigay bias, but, as so many historians have pointed out, in the wake of the Stonewall riots an authentic visibility became one of the guiding concepts in the struggle for gay and lesbian liberation. Oppression would never end, it was said, if gay men and lesbians refused to “come out,” to show their families, their friends, and the rest of the world who they “really” were. While it is true that the gay liberation movement held a different relationship to visibility than the counterculture, by revisiting these calls for visibility and authenticity in light of the Gay Liberation Front’s efforts to be included within the constellation of progressive causes and organizations known at the time as “the Movement,” the complexities and contradictions of that relationship will begin to emerge. Although, as so many historians of gay liberation remind us, groups like the GLF often took great pains to distance themselves from “queens and nellies,” transsexuals, transvestites, and those lesbians who seemed “too butch,” a reconsideration of radical post-Stonewall gay and lesbian politics reveals the extent to which a certain type of drag was nevertheless highlighted within these very same organizations. This reinterpretation of gay radicalism will give rise to a reevaluation of those organizations like the GAA that were often dismissed as “regressive,” “reformist,” or simply “naïve” for their willingness to engage the mass media and their refusal to abandon practices like camp and cross-dressing. In the end, I argue that it is perhaps more productive to view the practical and ideological divisions within the gay liberation movement not as a case of radicalism versus reformism but, much like the debates outlined in the first chapter, as a struggle over the relationship between politics and performance, “direct action” and aesthetics. In this sense I will, as historian John D’Emilio has urged, put “gay” back into the sixties.78 Unlike D’Emilio, however, who sees returning to the history of gay and lesbian activism as an opportunity to resuscitate a positive model for current political struggles, I will instead read gay liberation as one of a number of indicators that there was something quite queer, in the broadest possible sense, about a great deal of late-1960s activism.

My final case study in chapter 3 looks to the political career of “militant Negro” Eldridge Cleaver. Often seen as the personification of what Michelle Wallace so famously dismissed as “Black Macho,” Cleaver signifies to many the misguidedness of both the major figures of the Black Power movement and the white activists who seemed to accept him as the quintessence of personal and political authenticity.79 Critics have repeatedly rejected Cleaver’s political persona as regressive because of his tendency to enact the very stereotypes of hypermasculinity that had been used to oppress black men since the end of the Civil War. Cleaver spoke repeatedly of the equivalence between black liberation and the reclamation of black masculinity, and, conversely, the “counter-revolutionary” nature of same-sex desire. When confronted, for instance, by an “Infidel” who claimed that black men would always be subservient to white males because the “stem of the Body, the penis, must submit to the will of the Brain,” he responded not with a rational argument but an “erect . . . strong . . . resilient and firm” cock: “When I gave it that squeeze, a wave of strength surged through my body. I felt powerful, and I knew that I would make it if I never betrayed the law of my rod.”80 In response to this type of rhetoric, contemporary feminists accused Cleaver of being blind to the role women had played—and would continue to play—in any movement working toward the total transformation of society.81 More recently, Cleaver has come under fire from authors such as Kobena Mercer, Isaac Julien, Leerom Medovoi, and E. Patrick Johnson for his insistence on equating masculinity and heterosexuality.82 Medovoi, for example, explains that for Cleaver, “Black gay men, because they threatened the simple association of black masculinity with hypersexual virility,” had necessarily been “politically stigmatized as decadents, race traitors, or ‘false’ men.”83 In hopes of reopening the discussion of not only Cleaver but of Black Power politics more generally, this chapter reads Cleaver’s invocation of the “law of [his] rod” first in terms of the set of practices Henry Louis Gates, Jr. has labeled as “Signifyin(g),” and second in relation to the question of, as R. A. T. Judy puts it, “nigga authenticity.” Is it possible that Cleaver, who repeatedly lamented the black male’s social reduction to nothing more than brute physicality, was less interested in redeeming some essential black masculinity than in adopting the pose of “black macho”?84 To reassess the potential value of Cleaver’s political career, I argue, it is necessary to look closely at his enactment of a violent, hypersexualized version of black liberation, from his infamous critical attack on novelist James Baldwin in the essay “Notes on a Native Son” to his threat to kick California State superintendent of public instruction Max Rafferty’s ass. By placing Cleaver’s political actions and pronouncements within the history of the Black Power movement and alongside a close reading of the essays collected in Soul on Ice, I look to demonstrate that those actions that have for so long seemed only offensive may in the end have been rooted, at least in part, in a surprisingly subtle understanding of the politics of race, representation, and commodification.

Finally, in the short concluding afterword, I suggest the continued importance of aesthetic considerations to our analysis of contemporary politics. As so many retrospective texts and exhibitions have recently reminded us, the late 1960s occupy a special place in the American historical imaginary. The object of nostalgic reverence for many on the political left and of outright scorn for those on the right, talk of “the sixties” still has the power to provoke a heated reaction over forty years later. It is curious, therefore, to find that the events and ideologies of that decade are so often treated as all but settled in contemporary politics.85 The 1960s were, for example, the years in which modern imperialism offered one last great surge in Southeast Asia, and individuals, in response, attempted to suppress their differences and to identify with an allegedly revolutionary “class” that would end not only colonial aggression/oppression in the developing world but also poverty, discrimination, and exploitation in the United States and Western Europe. The decade effectively ended (or devolved, depending on one’s critical and political predilections) with the failure of both of these efforts. The United States suffered an embarrassing defeat in Vietnam, and various groups, insisting on the validity of differing subject positions, broke away from “the movement” to draw attention to individualized forms of oppression and liberation. After 1968, as we so often hear, the form of oppositional politics began to change dramatically.86 In this short concluding essay, therefore, I look to problematize this apparent closure. Considering the ways in which the political tactics of the late 1960s, far from simply disappearing, actually became something like the standard form for grassroots politics, I argue that the difficulties confronting contemporary “opposition” are not altogether different from those that gave birth to the ironic performances of that decade. From the more recent grassroots actions of groups and movements like the Yes Men and Billionaires for Bush, and, now, Occupy/Occupy Wall Street, the echoes of the put-ons I describe, and their sense of the aesthetics of politics more generally, can be heard throughout our own, supposedly distinct, era. The reframing of the late-1960s radical left I offer herein is an attempt to complicate our relationship to that period in American history and culture. What lessons could the Black Panthers, the Yippies, or the Gay Activists Alliance hold for groups currently working for equal rights, to end the war in Afghanistan, to combat global warming, or to deliver power to “the 99 percent”? Given these ongoing struggles and the (hardly coincidental) attention paid to the late 1960s in the last ten years, these questions seem perhaps more urgent than ever.

I am, of course, not the first or only one to believe that the time may be right for a reconsideration of the methods of late-1960s activism. Since the beginning of the Iraq war in 2003, or, rather, since the United States government’s explicit articulation of its intent to invade Afghanistan and then Iraq in 2001 and 2002, interest in the grassroots political tactics of that period has understandably surged. Yet even before these unilateral military actions were on the table, there was still a great deal of scholarly and popular interest in the relationship in that decade between grassroots politics and media representation. Todd Gitlin, Tom Wells, Doug Rossinow, Julie Stephens—a number of authors in the 1980s and ’90s returned to the question of activism and media coverage in an attempt to determine just what we might learn from the struggles, triumphs, and failures of “the sixties.”87 These reappraisals, and others, were part of what has been described as a larger shift in writing about 1960s grassroots politics, a move away from simplistic divisions between politics and culture toward a more nuanced understanding of the mutual influences of, say, the New Left and the counterculture.88 Much as these authors have made an effort to not simply dismiss culture in favor of “real” politics, however, their generosity appears not to extend to engagements with the mass media. The media’s commercial character, its propensity to turn all opposition into simple spectacle, they suggest, ultimately renders protest impotent. The mass media may have “made” the New Left, in Todd Gitlin’s phrasing, but the inevitable allure of fame that accompanied the media’s attention proved irresistible. For this reason, Gitlin and others conclude, media coverage and “real” opposition are best seen as mutually exclusive. Although willing, in other words, to acknowledge the cross-pollination of politics and culture, arguments such as these remain rooted in a basic assumption that true opposition must transcend the boundaries of a given social order: one must either provide a carefully reasoned argument exposing society’s failure to live up to its own promises, or literally enact an alternative.

As it should by now be clear, this assumed choice between transcendence and “selling out” is, and was, not as clear-cut as it may seem. Thus, in the last ten years, authors such as Marianne DeKoven and T. V. Reed have begun to move beyond this basic position.89 DeKoven returns to the work of Marcuse in a thorough and quite fascinating reading—one that has exerted tremendous influence on my own engagement with his work—and highlights the often self-contradictory language used to describe the utopian political visions of groups like Students for a Democratic Society. Reed, on the other hand, stresses the role of song in the civil rights movement, and the theatrical strategies adopted within, among others, the movement for Black Power. Both authors explore cases in which aesthetics and politics intertwine, thus calling into question familiar assumptions regarding the political value of asserting an authentic personal identity and the necessity for “true” critique to originate from a position excluded by the dominant order. In the end, though, neither fully takes on the relationship between the “emergence of the postmodern,” strategies of political performance, and the mass media. This is precisely what makes the work of media historian Aniko Bodroghkozy so interesting. While many analyses could be said to sacrifice either an understanding of the media for an emphasis on history or an understanding of history for an emphasis on media, Bodroghkozy looks to situate television coverage of political demonstrations and protests within a larger discussion of the popular fascination with youth culture in the late 1960s.90 This is an incredibly rich avenue of inquiry, and Bodroghkozy does a great deal to distance herself from the analyses of authors like Gitlin, arguing that the Yippies’ understanding of the mass media may have been far more sophisticated than earlier authors assumed. But her account stops there, leaving the reader to wonder just what the subtleties of Yippie media theory may have been, or why Bodroghkozy insists on separating this “self-conscious” form of protest from what Sontag labeled the “Camp sensibility.”

But the one effort to reassess “the sixties” that is most closely related to my own is David Joselit’s Feedback: Television Against Democracy. Joselit offers a nuanced reading of the cultural significance of television in postwar America, paying particular attention to the way in which it seems to blur the distinction between commodity and network, the way it presents, in effect, the network as a commodity. Along the way, Joselit offers examples of activists seeking to make use of television and film as weapons in the struggles for Black Power or against the Vietnam War. These examples demonstrate, he argues, in contrast to so many who have written on grassroots politics in the late 1960s, that easy oppositions between the media and “real” dissent underestimate the sophistication of these activists and, more importantly, leave later generations facing a political dead end. As a fellow art historian interested in the televisual (re)presentation of political positions, I find Joselit’s ambition, his hope for a thorough reconsideration of art history’s scope, incredibly exciting. The practice of art history, he suggests, should not be approached as a simple matter of cataloging objects, as it is also, or primarily, a concern with the history of taste, aesthetics, and representational conventions. For this reason, he writes, “If we . . . rethink our critical vocabularies and allow them to migrate into areas of vital concern . . . [we] will find ourselves with much to contribute to the social and political debates of our time.”91 As promising as Joselit’s proposal sounds, however, one finds in Feedback a number of moments in which his own attempts to shift the terms of existing debates through art historical intervention appear to fall short. In spite of his urgings to rethink the simple opposition between “real” politics and television, for example, he nevertheless falls back, at times, on a very similar distinction. Chiding those who stubbornly cling to the notion of an “outside” in the face of the “closed circuits that fashion our public worlds,” he rather puzzlingly asserts that neither “the modernist aesthetic tactic of revolution nor the poststructuralist technique of subversion (which in any event are two sides of the same coin)” can provide an adequate response, “unless one is prepared to wage actual political revolution and to pay its price of massive violence (something those with subversive on their lips might well remember).”92 Perhaps moments like these should come as no surprise, given that Joselit’s title pits, quite literally, television against democracy, an incompatibility or mutual exclusivity suggesting that, ultimately, his arguments may not be so far removed from those of Gitlin and others. Moreover, Joselit at times recapitulates, however unconsciously, Marcuse’s most questionable assertion—both factually and politically—by posing a stark contrast between the media-based actions of white artists and activists and those of their “informationally disenfranchised,” that is, nonwhite, counterparts. Activists like Hoffman and artists like Warhol, as complex as their engagements with the media may have been, nevertheless “presume[d] the possession of an intelligible identity,” forgetting that “such self-possession was not a universal privilege.”93 In contrast, Joselit argues, a film like Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, by virtue of its status as an independent, nonstudio production starring the “Black Community,” offers an example of a less-compromised, more authentic version of media politics.

As I have already indicated, and as the chapters that follow will make clear, when we write the put-on back into the history of the late 1960s, this distinction between those whose actions have been rendered image and those who have been denied that “privilege” becomes far more difficult to maintain. No one was exempt from the system of representation and commodification. Like the “militant Negro,” the “hippie,” and the “homosexual” in Brackman’s examples, Cleaver, Hoffman, Rubin, the members of the GAA, and the “queens and nellies” so frequently condemned within the gay liberation movement seemed on some level to recognize the inseparability of politics and performance. This, I argue, is why they appeared to recite time and again the very terms they claimed to dispute. For this reason it may be more fruitful to read Cleaver’s “shit talking,” Hoffman’s “monkey theater,” and the GAA’s “zaps” not as mere symptoms of personal neuroses or indications of a thoroughly co-opted or misguided radicalism, but as put-ons, campy repetitions of political personae that were, in themselves, little more than repetitions of normative conceptions of opposition, whether in the form of black masculinity, youth culture, or same-sex sexuality. My goal, in other words, is not so much to determine precisely what it meant for Cleaver to denounce Baldwin, for the Yippies to threaten Democratic Party delegates with seduction, or for Sylvia Rivera to wear women’s clothes. Rather, I propose that we should read these actions as performances, analyze them in relation to the forms of nonconformity they recited. Just why, we should ask, did the members of the GAA smile when reminding New York mayor John Lindsay during the taping of his televised talk show that it was “illegal to blow anything in New York”? Why would Hoffman and Rubin have wanted to lead thousands of young people into Chicago for what many said would almost certainly end in a police riot? Why would Cleaver have so willingly embodied the image of black male “supermasculinity” he claimed to detest?

Again, my aim is not to demonstrate that these performances offered a practical counterpoint to, or advantage over, the misguidedly “authentic” statement of political commitment. This would be merely to rephrase the opposition between political purity and co-optedness that practices like the put-on attempted to expose as effectively meaningless. On the contrary, to understand the legacy of the 1960s it is essential that we begin to perceive these two modes of political speech as inextricable. What emerges from the parodic performances outlined herein is the sense of a historically specific form of transgression, simultaneously earnest and campy, claiming to present thoroughly oppositional identities while demonstrating the incredible difficulty of that very enterprise. Where Marcuse and Sontag had hoped for a form of true eroticism or aesthetic practice capable of distancing the individual from the instrumental logic of capital, these stereotypical personae may in fact have been a series of attempts to lead viewers to recognize the impossibility of achieving that distance—whether through racial or sexual difference, an unfettered Eros, or any other ostensible mode of opposition. By reading these enactments of acceptably unacceptable “radicalism” as put-ons, rather than misguided attempts to articulate “real” opposition, we can begin to recognize the perceived urgency of the “impulse to impersonation” condemned by Brustein. In so doing, we may come to see this radical theatricality as a signifier not of the failure of identity politics but of the politics of failed identities.