CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

USING THE TOOLS: STUDY AND LEARNING

We gather information from all sorts of places. If you’re a student, you might be taught in a classroom by a teacher, or on your own from a book, an educational film or the Internet. If you’re a businessman or -woman, or even a teacher yourself, you’ll have reports, training documents, journals and so on to read and understand. However you’ve received it, information has to find its way into your long-term storage, so that you can retrieve it whenever you need to – whether that’s in an exam, in a meeting, or to teach to others.

The place where most of us did most of our formal learning is school. Estimates vary as to how much of the information we are taught at school we actually remember for any length of time. According to research by The William Glasser Institute, in California, we retain only ten percent of the information we absorb from reading, while we retain approximately half of the information we see and hear, and personal experience gives us around 80 percent retention. The research also shows that if we actively teach something, we retain around 95 percent of the information we pass on to others.

So, what does this tell us? First, and most importantly, it tells us that when we engage actively in a “live” situation, we are more likely to retain information. Second, it shows us that personal experience (which involves action and the senses) is far more likely to lead to long-term storage and retrieval than detached learning methods, such as reading. When we teach information, not only do we have to repeat it, we also have to have understood it, which reinforces the initial learning, embedding it in the brain.

For me, there are four key skills when it comes to success in learning, no matter what the method:

• Absorbing knowledge effectively

• Note-taking

• Memorizing

• Reviewing

Reading efficiently and effectively

The truth is that much of the information we need to learn, to pass exams or do our job, comes from reading – whether you’re trying to learn a topic at college or learn figures to present at a team meeting. If you want to maximize the efficiency of learning from the printed word, you might think that reading more slowly and deliberately, trying to retain every detail, is the way forward. However, studies show that reading more quickly, as long as you do this properly, is more likely to get the information to stick. The best method is to use a pointer that you can run along the words as you read them. A pen or even your index finger will do. Research indicates that pointing to each word as you read it significantly increases concentration levels during reading, and also – perhaps surprisingly – the speed at which you read.

Making notes on the key points

I recommend that you read for 20 minutes at a time, before finding a suitable stopping point so that you can make notes. You need to identify the key points in the text you’ve read and note them down on a sheet of paper. A Mind Map® is the perfect visual store for information we derive from print. See pages 142–4 on how to create one for your topic. Ideally, you should be able to distil your reading from the memory of what you’ve just read – without looking back, which will slow down the note-taking (but there’s no harm in looking back if you need to).

Memorizing the key points

Once you have your key points, you can organize the information and code it into something you can memorize. Do this in exactly the same way that I taught you to memorize speeches (see pp.144–5). On your Mind Map, number the main points in your topic, write these main points in a list and then turn each into a visual key. Place each visual key along a journey of the appropriate number of stages and – hey presto! – you’ve memorized the important elements of the information you’ve just read.

Memorizing dates

Whether you’re studying history or literature, economics or geography, being able to memorize dates effectively is essential. Let’s say you’re studying history, and you need to commit to memory the key dates in the American War of Independence. The war began on April 19, 1775; the first major battle between British and American troops, the Battle of Bunker Hill, took place on June 17, 1775; the American Navy was established to fight the British on November 28, 1775; on January 9, 1776, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense pamphlet was published; then July 4, 1776, finally saw the American Declaration of Independence.

To memorize these dates and events, you’d use a prearranged journey – perhaps a journey around your school would work well – and then code each event and date into a colourful scene for each stop. So, let’s say that the first stop is the school gates. The information you need to place there is April 19, 1775, the start of the War. I imagine a starting pistol being fired at the school gates and it’s pouring with rain (April showers). I imagine my friend Anne (19 = AN, which gives me the sound trigger for the name Anne) is there, standing under an umbrella. Now I just need to use the Dominic System to add the year. I picture former Vice President Al Gore (17 = AG, Al Gore’s initials) reclining in a comfy leather chair while getting soaked in the rain (75 = GE, my friend Gerry who used to watch movies in his favourite leather chair, which gives me the prop). I follow the same process for each date and event, posting them at consecutive stages along the route, until finally, in the school hall, I have my friend Julie (July) shaking hands with Olympia Dukakis (OD = 04 for the fourth of the month) on stage at a formal speech ceremony (to denote the declaration of independence). Al Gore (AG = 17) has Gwen Stefani’s (76 = GS) feature, which is bleached blond hair, and is standing at the side of the stage.

Reviewing your learning

The “forgetting threshold” (see p.135) – the point at which our spinning memory plates begin to wobble – exists no matter what you’re trying to memorize. Whether you’re learning information for an exam or to present at an important meeting, knowing when and how to review what you’ve learned is crucial to ensuring that you minimize any forgetfulness when you’re under pressure. The Rule of Five (see pp.76–80) is my favourite method of review, but there are others. Scientists have identified several “effects” of the brain during learning. These can help us to understand why reviewing is so important to effective learning and recall.

The primacy and recency effects

If you try to memorize a list of, say, 20 items without using any strategy, the chances are that the first five to ten items will stick fairly easily. This is known as the primacy effect and it operates because of your patterns of concentration during learning. At the beginning of a list (or any information you’re learning), you’re more attentive and alert. But then as your brain begins to assimilate that information for storage it’s distracted from concentrating on the next wave of information, leading to a sag in learning.

Once you perceive that the information is coming to an end, your concentration levels tend to pick up again, because your brain anticipates the end of the period of concentration, which sort of wakes it up. This is called the recency effect.

The recency effect affects your memory and recall in all sorts of ways. For example, it can significantly influence your memory of things that have happened to you. Imagine that you’ve had a productive, but unexceptional day at work and are driving through the city to get home. You encounter ten sets of traffic lights. The first seven are green and you go straight through them, but the last three are red and you have to stop. When you get home, your partner asks you how the journey was and what your day was like. Your recent memory is triggered – the journey was slow, because the lights were against you, and generally you’ve had a bad day. In reality, of course, this is a poor reflection of what actually happened – but it’s the idea you have in your head because of your most recent experience.

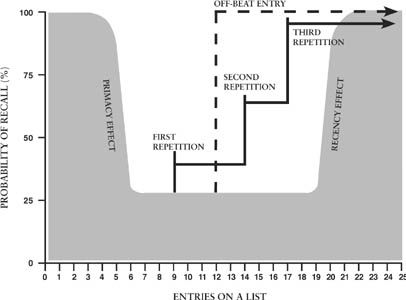

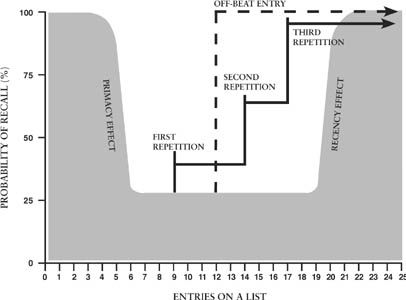

In a graph that shows attention over the course of time, the primacy and recency effects result in a big sag in concentration in the middle (see graph, p.160), so that recall levels drop to about 25 percent. However, there are various techniques that lecturers or speakers use to ensure that the sag is minimized and that the important information is hammered home. The first is repetition: think of advertising campaigns you hear on the radio or TV – how often do you hear the product name? Usually it’s repeated several times, even in a 30-second slot, because your brain absorbs it more willingly if it hears the name more than once.

Another technique often used by speakers or lecturers is to add humour or something off-beat to the talk. An odd shift in pace or content provides a little memory shock, which wakes up your brain cells to keep you alert. The Von Restorff Effect (see pp.65–7) is one such memory shock, and is another great tool to ensure that learning is maximized throughout a speech or lecture.

This is all very well, of course, but it doesn’t help if you’re learning something from print. In this case, taking regular breaks is essential. It is much better to divide your time into, say, six 20-minute bursts of study, than to try to focus for a full two hours before taking a break. It stands to reason that short bursts avoid the negative impact of the primacy and recency effects on your ability to retain information (and so recall it).

This graph shows what happens to our concentration levels as we’re given information. We more easily retain items in a list, for example, at the start of the list (primacy effect) and then at the end of the list (recency effect) than in the middle, where the brain loses focus as it’s busy assimilating all that it’s already heard. Information (or an entry) that is repeated becomes more memorable with each repetition, and off-beat information “wakes up” the brain (see pp.65–7), making that piece of data stand out, and so more memorable.

As a rule of thumb, a 20-minute study period followed by a four-or five-minute break should work well to minimize the influence of primacy and recency. During the mini-rests your memory has a series of reminiscences that consolidate your learning, while you busy yourself with something completely unrelated.

Reviewing the reviews

Whatever you’re trying to learn, and for whatever purpose, once you’ve read the relevant information, distilled it into notes and then memorized it, you need to review it effectively to ensure that it sticks. In 1885, the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus first described the “forgetting curve”, which charts the rate at which memory loses data after it has learned something new. The curve reveals that the most rapid memory loss occurs within the first two hours of memorization. In practice, this means that unless you review and refresh your memory regularly during the process of lengthy memorization, you’ll have to relearn the information that came first at a later date. As long as you review regularly as you memorize, all the information you learn embeds itself deeply within your memory for better long-term recall.

How to review information effectively

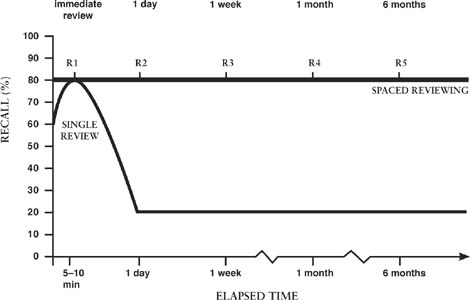

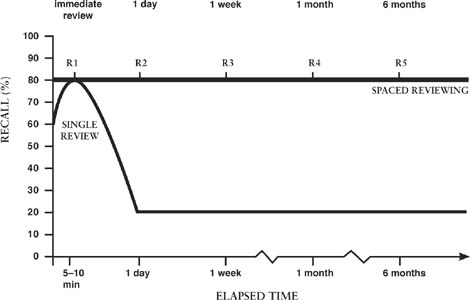

When you read and take notes from a book it’s fairly easy to flick back through the pages if you think you might have missed something, but how does this work if you have to review information that you’ve heard in a meeting or lecture? Perhaps you’re attending a training course for your job or are taking exams. Ebbinghaus discovered that if we take notes as we listen, and then review the notes immediately following the event, we can retain 80 percent or more of the information we absorbed. The lecture can be short or long, provided that, after it’s finished, the first review of the notes happens straightaway. For optimal recall, he concluded that we should then follow this first review with a second review a day later, a third one a week later, a fourth one month later, and a fifth, final review three to six months later (if the content was particularly complex). Ebbinghaus called this the “Distributed-Practice Effect” and noted that “with any considerable number of repetitions, a suitable distribution of them over a space of time is decidedly more advantageous than the massing of them at a single time.”

INSIDE MY MIND: WHEN I WAS A STUDENT ...

I remember the run-up to my school exams as weeks of cramming – relearning information I’d been taught months ago, but had almost entirely forgotten, and trying to memorize other information by rote learning at the last minute. Many of the students I meet these days do exactly the same. I can particularly recall the stress of repeating Spanish words over and over again, in the hope that most would stick long enough to get me through my Spanish oral and vocabulary tests. It’s only now (when, obviously, it’s too late to make a difference to my grades!) that I realize that revision should be an ongoing process. To excel at what they learn, students need to cast aside the last-minute, damage-limitation exercise and instead go through a process of topping up their learning with patterns of review. That’s why I think it’s so important to spend time telling you about my review strategies, so that you can apply them to your own learning in your quest for an amazing memory.

This graph shows what happens when we use a strategy of spaced review, compared with a single review. The latter, performed immediately after learning, shows that recall of the imparted information leaps from 60 to 80 percent. However, if we make no further reviews, within 24 hours recall falls dramatically to only 20 percent, where it stays for the foreseeable future. The information we learned originally would have to be re-learned before we could recall it effectively for, say, an exam. However, if we adopt a spaced review strategy, coming back to the information straightaway, and then a day, a week, a month and six months later, recall can remain at 80 percent, which is what Ebbinghaus called the “Distributed-Practice Effect”.

The illustration above shows the Distributed-Practice Effect as a graph. By spacing the reviews of learned information, increasing the intervals of time between each review, recall can remain at levels as high as 80 percent. This means that you don’t need to re-learn information when you need to call upon it again, because it’s already embedded in your long-term memory.