6

6

The Before- and Afterlife of Meter

If life is not always poetical, it is at least metrical. Periodicity rules over the mental experience of man, according to the path of the orbit of his thoughts. Distances are not gauged, ellipses not measured, velocities not ascertained, times not known. Nevertheless, the recurrence is sure.

—Alice Meynell, The Rhythm of Life

See, they return; ah, see the tentative

Movements, and the slow feet,

The trouble in the pace and the uncertain

Wavering!

—Ezra Pound, “The Return”

Few writers benefitted more from the boom in soldier poetry and the explosion of popular verses during the First World War than the poets associated with what we now call “modernism.” But modernist writers, especially, deserve reconsideration and recontextualization within the shifting cultural and educational contexts of the Edwardian and Georgian eras. In “Prolegomena,” published in Harold Monro’s Poetry and Drama in 1912,1 Ezra Pound writes, “I believe in an ‘absolute rhythm,’ a rhythm, that is, in poetry which corresponds exactly to the emotion or shade of emotion to be expressed. A man’s rhythm must be interpretive, it will be, therefore, in the end, his own, uncounterfeiting, uncounterfeitable.” If the poetry of Newbolt was arguing for a collective “metrical” national identity (that Newbolt and Bridges nonetheless understood as highly individualized), then Pound replied with an even more individualized idea of rhythm—something that begins and ends with each poem. In “A Few Don’ts,” published in Poetry magazine in 1913, Pound continues to imagine rhythm as individual and authentic as opposed to the collective counterfeit of metric patterns—a divide, I argue, between an at-once individual and universal “rhythm” and an elite, external, and artificial “meter” that he narrates as if it is distinct from his own metrical investigations, the expired product of another age. It is important to recall, too, that the artificial “meter” of patriotic poetry was already an abstracted, misrepresentative description for rhythm. To Pound, the collective military-metrical project I described in chapter 4 is read as derivative; they merely “shovel” in words to “fill a metric pattern or to complete the noise of a rhyme-sound.”2 Pound not only misunderstands the upsurge in a rousing Edwardian English accentual rhythms as “metric” (and forgivably so), he is also suspicious of the simultaneous obsession with defining English meter for the discipline of English literary study and linguistic science. Pound advocates a simultaneous awareness of and need for historical forms as well as a complete disregard for them at the moment of writing. He writes “[p]ay no attention to the criticism of men who have never themselves written a notable work. Consider the discrepancies between the actual writing of the Greek poets and dramatists, and the theories of the Graeco-Roman grammarians, concocted to explain their meters.” Rather than reading metrical explanations, he suggests, “let the candidate fill his mind with the finest cadences he can discover, preferably in a foreign language” (4, 5). If grammar fixes and stabilizes, so, too, by extension, does meter. Pound’s desire for a rhythmic fluidity rests on a descriptive rather than prescriptive approach to poetic form; and yet “to describe” would be also to fix. By assuming that “cadences” can be absorbed phenomenologically, somehow at the level of “instinct,” Pound both troubles and supports the assumption of inherent abstract national rhythms so promoted by the grammarians of the eighteenth century through Henry Newbolt. And yet, rather than a universal “Englishness,” the cadences and rhythms Pound supposes for poetry are somehow universally “poetic”—beyond the realm of grammar or meter, and require the “shock and stroke” of each individual.3

Pound’s belief in an at once “universal” and “individual” rhythm was, in many ways, as class-determined as Saintsbury’s or Bridges’s. By shoveling words into preexistent molds, poets employing a metric pattern without making it their own were guaranteeing their obsolescence and displaying their vulgarity, their lack of an elite understanding of ancient forms. (Indeed, the class implication of Pound’s day-laborer word choice shows that he is much more aligned with the educated elite than the common man that he implies he would be freeing from the shackles of meter.) He admits that he has devoted himself to “the ancients” (“pawed over”) in order “to find out what has been done, once and for all, better than it can ever be done again” and yet he concludes, “I doubt if we can take over, for English, the rules of quantity laid down for Greek and Latin, mostly by Latin grammarians.” Pound reveals his familiarity with Bridges’s experiments here, but puts himself in Bridges’s role: the only mention of Bridges, however, is to admit that “Robert Bridges” is “seriously concerned with overhauling the metric, in testing the language and its adaptability to certain modes.”4 Yet his vitriol against “the metric” is every-where evident; Pound continues to elaborate on the violence of traditional metrics: “don’t chop your stuff into separate iambs. Don’t make each poem stop dead at the end, and then begin every next line with a heave. Let the beginning of the next line catch the rise of the rhythm wave, unless you want a definite longish pause.”5 Pound’s language supports the narrative of a violent break with the past as well as the violence that meter can do to a poem. He narrates “rhythm” as an ideal hybrid form that mediates between the individual and the community, and yet his assumption that any and all metrical systems are hegemonic and rigid belies his ignorance of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century poetics. Indeed, the modernist revival of the term “cadence” rather than “meter” or “rhythm” marks a return to Lindley Murray’s original 1795 definition of versification, back to elocution and performance imagined through the image of the printed page. Everything should be fluid; even the “pause,” a primary element of versification, is abstracted into “definite longish.” Though bad poetry will begin the next line “with a heave,” Pound will redraw the lines of poetic tradition by declaring in his Pisan Cantos more than forty years later the famous statement I quoted earlier: “To break the pentameter, that was the first heave” (Canto 81). The first “heave” was really Pound’s misreading of nineteenth-century meter, or rather, collapsing a variety of metrical experiments into one collective project of predictable verses. Pound did not “break” the pentameter, as his five-beat line roughly demonstrates, but he dares us to dwell on his “that” after the “break” of the midline caesura, as if to cast his line precariously into four beats. But I have shown the artificiality of “that” break, or Pound’s imagined divide, and argued why and how the pen-tameter and the four-beat line would have been something that so many poets invested with meaning, and how one or the other could be read as variously “natural” or “artificial.” Pound knew that to retroactively impose a structure on the past would allow him to bury it, exhume it differently, and make it part of his own invention. However, this same retroactive imposition of stability is strikingly similar to what was happening in English meter with the burial and exhumation of classical meters from the end of the nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. The perceived stability of English metrical forms was based on a variety of factors, but it was the supposed stability of classical meters on which English meter was ostensibly, partially, and perhaps erroneously based in the late nineteenth century. In fact, fewer and fewer poet-critics believed in this particular classical metrical genealogy. Pound’s infamous “break” with the pentameter and his restrictions against using “strict iambs” obfuscates the rich heritage of experiment, debate, and contested metrical discourses that circulated throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Later on in “A Retrospect,” Pound muses, “I think progress lies rather in an attempt to approximate classical quantitative metres (NOT to copy them) than in a carelessness regarding such things.”6 He adds the note, “let me date this statement to 20 August 1917,” significantly indicating that, in 1917, there were various kinds of experiments at work in the field of English meter and that vers libre was just one of a multitude of possibilities in the early twentieth century. Pound neglects to mention, perhaps because he would rather not acknowledge it, that meter in the Victorian era was similarly experimental, contested, and varied—a proliferation of concepts rather than a unified field.

As I have by now made quite clear, Bridges’s exacting prosodic experiments—themselves evidence of the proliferation of concepts about verse form—have been overshadowed by the more popular free verse experiments of Pound, Eliot, Williams, and other artists associated with the anti-Georgian literary movements of the 1910s and 1920s, embedded though those experiments were with various metrical forms not at all “free.” The divide between poet-prosodists like Bridges and Pound parallels the divide between the formal investigations of linguistics departments and those of English departments, in which the constant search for a “right” answer and the abstraction of metrical form secures that the very freedom it allows will be just flexible enough to survive as the kind of law about which professors like to argue. Pound and Bridges, however, were more alike than either acknowledged. In 1936 Pound refused to write a short memoir of Bridges, joking to Eliot,

I take it all I gotter do is to talk about Britches, not necessarily read the ole petrifaction? … Rabbit Britches indeed!!! … proposed title of article: ‘Testicles versus Testament.’ An embalsamation of the Late Robert’s Britches. All the pseudo-rabbits: Rabbit Brooke, Rabbit Britches … I spose I can cite what I once said of Britches? I managed to dig about 10 lines of Worse Libre out of one of his leetle bookies. Onct. And then there iz the side line of Hopkins…. In fact, the pooplishers ought to donate a Hopkins and the Hopkins letters so az to treat Britches properly. Background for an article that wdn’t be as dull, oh bloodily, as merely trying to yatter about wot he wrote.7

The association of Robert Bridges with Rupert Brooke (Rabbit Brooke) here is significant. Both “rabbits” are infantilized, indeed animalized through Pound’s dialect. Though ostensibly phonetic, Pound’s playful dialects also efface the serious phonetic experiments of Shaw, Bridges, and other phoneticians in the early twentieth century—the very discourse that has continued to trouble over the problem of pronunciation and versification in linguistics to this day. But more importantly, by placing Bridges alongside the war hero Rupert Brooke, Pound essentially devalues Bridges’s experiments, experiments that Pound himself had valued at the start of his career—although he does know that Bridges should be treated “properly,” “wot he wrote” is somehow instantly forgettable, as forgettable as any war poet.

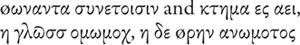

In a letter dated the next day, Pound decides to not even attempt an article about Bridges, saying it would be a “falsification of values” and that Bridges is already “a corpse of the null” (280, 281). His mention, in the prior letter, to The Testament of Beauty is also a show of how frustrating it must have been for Pound that the poet whose legacy he was trying to desperately to unseat had, with The Testament of Beauty, outsold and outshone the kind of poetry Pound wanted to promote. Though Pound only stated his condemnation of Bridges privately, it shows how much Pound revised his views toward poetic mastery in the years after the war. The younger, less famous Pound felt little but envy for the poet laureate in October 1915, when he reviewed Bridges’s Poems Written in 1913 in Poetry Magazine: “beyond dispute, his command of the sheer mechanics of quantitative verse can be looked on with nothing but envy. I have a grave respect for any man who is restless and persistent in the study and honor of his craft.”8 Pound singles out two poems from the volume, “Flycatchers,” which I discussed in chapter 3, and “a brief epigram, bitter as Palladas, full of emotional violence held in by rigid, delicate barriers “[title in Greek]”:

Who goes there? God knows. I’m nobody. How shall I answer?

Can’t jump over a gate nor run across the meadow.

I’m but an old whitebeard of inane identity. Pass on.

What’s left of me today will very soon be nothing. (43)

Though Bridges’s verses, as Pound predicted, have been forgotten in contemporary discussions of literary modernism, exhuming Bridges’s works might “embalm” him (and provide “summation“) differently than the “enbasalmation” Pound eventually imagined. But earlier in the same review, Pound outlines how little poets know of accentual and quantitative verse today, writing a brief history of all verse forms as essentially free (including “vowel-chants” from Egypt and “polyrhythmical sequairies and litanies” from the middle ages) and then continuing to blame the metrical rigidity on mid-Victorian culture:

And after all these things came the English exposition of 1851 and the Philadelphia Centennial, introducing cast-iron house decorations and machine-made wood fret-work, and there followed a generation of men with minds like the cast-iron ornament, and they set their fretful desire upon machine-like regularity…. [T]he indigenous Anglo-Saxon rhythms were neglected because society did not read Anglo-Saxon. And the most imitative generation of Americans ever born on our continent set themselves to exaggerating the follies of England. (41)

Though Pound is aware that Bridges’s name “is almost a synonym for classic and scholarly poetry,” he resents that Bridges’s knowledge of verse form could lead him to name one of the poems in his new volume an “experiment in free verse,” calling it a “smack in the eye” to the provincials who merely imitate machine-like verses. But Pound’s retelling of literary history shows how little he knew of the Anglo-Saxonist movements in England and America, though his own interest in Anglo-Saxon was certainly a product of these. Likewise, by dating “machine-like regularity” of “cast-iron” verses at mid-century, he simplifies the projects of poets whom he knows are more metrically complex than this history allows. But even if Bridges, architecturally, might be compared to “a pseudo-renaissance classic façade,” Pound relents that there are poems in his volume “comparable with the best in the language.” The review reveals both Pound’s wish to be recognized as an authority (amid multiple competing authorities: Saintsbury, Skeat, Mayor, Brewer, etc.) on matters metrical and historical as well as his nearly resentful admiration for Bridges, whom he must admit is already recognized—and should have broader recognition—as a master of multiple metrical forms.

Two years before Pound’s review, Bridges published “A Letter to a Musician on English Prosody” in the same issue of Poetry and Drama (1913),9 in which Edward Thomas published his views of war poetry and where Pound published a number of poems. If Pound’s insistence, in “A Retrospect,” that poets should “compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome,” is abstract and collapses metrical regularity in all its forms to a ticktocking time-keeper, Bridges’s explanation so intricately describes the complexity and difficulty in the history and future of English metrical study that his “letter,” in its very expertise, unseats Pound’s authoritative statements. Even “a musical phrase” is troubled in Bridges’s account. Less a “letter” and more a mini-metrical treatise along the lines of the views Bridges expressed in Milton’s Prosody, the coexistence of these texts in the same periodical shows how, despite Pound’s own narratives of rhythmic invention, he was aware of —though pretended a willing ignorance of—the ways that other poets were explaining and attempting to understand English verse rhythm. Lines from Hugh Sewlyn Mauberly, in particular, gesture to his need for inclusion in this rehistoricization of prosodic form. Participating in the same discourses as Owen, Pound writes, “Died some, pro patria, / Non “dulce” non “et décor” … / walked eye-deep in hell / believing old men’s lies, then unbelieving” (12). Why would Pound, or any poet in the 1920s, buy into the broken promise of poetic form in English? Pound engages with this metrical discourse at the same time that he attempts to reject it so that he can position himself as the arbiter and authority. Like Saintsbury and Patmore rejecting the metrists who came before them, Pound performs the characteristic move of negatively characterizing his predecessors. Though Pound was not a product of the English education system, he was sufficiently educated to understand the ideologies of English poetic form that he refused, yet at the same time could not help but inhabit. Eliot’s poetry and prose are similarly inflected with traces of the rise and fall of meter, and deserve reexamination along historical and prosodic lines, as does the complex prosodic discourse and recasting of tradition evident in the poems of Robert Frost, Mina Loy, H.D., William Carlos Williams, and even, perhaps especially, Yeats.

Eliot defines Pound’s metric according to an “adaptability of metre to mood, an adaptability due to an intensive study of metre, that constitutes an important element in Pound’s technique. Few readers were prepared to accept or follow the amount of erudition [in Personae and Exultations] … or to devote the care to reading them which they demand.”10 Eliot then summarizes Pound’s substantial “erudition” but concludes that the poems require “a trained ear, or at least a willingness to be trained” (167). Eliot, writing in 1917, seems to contextualize Pound’s metric in terms of an “English ear.” And yet this definition and formation of a reading practice according to an “ear” was conceived as a new critical model in the 1920s. “How to read meter” became a question severed from English historicity and politics, cut from any lingering association with metaphysics, and was transformed into a secular and ahistorical reading practice. Pound, Eliot, and other poets of this formative Victorian-Edwardian-Georgian moment, deserve reconsideration within the shifting contexts of English philology and education that I present here, figured literally and allegorically in changing conceptions of metrical form in English.

Make It Old: Robert Bridges and Obsolescence

“As for the nineteenth century,” Pound writes in “A Retrospect,” “with all respect for its achievements, I think we shall look back upon it as a rather blurry, messy sort of period, a rather sentimentalistic, mannerish sort of period.” Until Swinburne, Pound attempts to persuade us, “poetry had been merely the vehicle … the ox-cart and post-chaise for transmitting thoughts poetic or otherwise.”11 Pound is emphasizing the newly mechanistic nature of modernist rhythm, as opposed to the rural, agricultural, provincial meters of old that, without a trace of acknowledgment as to why or how these rural, agricultural, or provincial meters were otherwise conscripted into the service of a national Anglo-Saxon past (working class, nativist, persistent, and steadfast).12 We have seen what Pound made of Robert Bridges, and his recasting of Bridges as a “corpse of the null” has done its work to keep Bridges’s life and work hidden. But what did Bridges make of Pound and the new generations of poets who would prefer that the laureate fade away, back into the Victorian era where he belonged? It is true that Bridges had always been associated with a kind of “older” style; he looked backward toward Milton and to classical verse forms. He published multilingual The Spirit of Man wartime anthology when he was eighty-four years old. But however slow his poetic output might have been in later years, he continued to experiment and to perfect what he felt was a more delicate form of free verse, all the while aware of and attempting to educate his audiences about the histories and possibilities for accentual, syllabic, and quantitative verse traditions in English. In his late-career poem, “Poor Poll,” Bridges reveals his disappointment that his life-long pursuit to reveal the multiplicity of metrical forms, their historicity and possibility, is either too technical for the mass public or rather, too belated. That is, his understanding (just as Pound’s) of English poetics relies on an education that is no longer possible in the national school system, without an intimate knowledge of classical verse forms.

Bridges published “Poor Poll” in 1923. Ostensibly a reference to John Skelton’s 1521 poem, “Speke, Parrot,” which was also written at a time when the ideologies of classical education were under debate, Bridges both commented on the resurgent interest in Skelton and alternative verse forms as well as used the platform of metrical experiment to address the deterioration of Western civilization.13 When it was first privately circulated, on a quarto sheet, he included a preface as well as “metrical elucidations” to flaunt his accomplishment and perhaps obfuscate the latent critique in the poem (this preface and the metrical elucidations were not reprinted with the poem in Bridges’s life-time or in any subsequent edition of his poems). After Milton, he decided to use a twelve-syllable verse line; not only could all speech fit within that structure, but speech and metrical forms from most Western languages:

I saw … that all the old forms of 12 syllable verse, the Greek iambic, the scazon, the French Alexandrine, etc., would be admitted on equal terms. It was partly my wish for liberty to use various tongues that made me address my first experiment to the parrot, but partly also my wish to discover how a low setting of scene and diction would stand; because one of the main limitations of English verse is that its accentual (dot and go one) bumping is apt to make ordinary words ridiculous; and since, on theory at least, there would be no decided enforced accent in any place in this new metre, it seemed that it might possibly afford escape from the limitations spoken of. And thus I wrote “Poor Poll”14

Readers of his collected verse would find the poem under the heading, “Neo-Miltonic Syllabics,” (all in the twelve-syllable line) along with a few other poems in the same style, but unless one were a prosodist who had followed Bridges’s development through the appendices of Milton’s Prosody, or happened to be a colleague in the Society for Pure English, the common reader would encounter a poem that referenced various meters but did not clearly settle into a recognizable accentual-syllabic pattern. The poem is at once welcoming and repelling; the “low setting of scene” is appropriate for a wide audience, but the multilingual references speak to a select few. Bridges’s poem weighed in on the state of English and classical education; written in the same year that Newbolt’s The Teaching of English in England was published (1921), it expresses both joy and regret over the report’s conclusion that literature “must never be treated as a field of mental exercise remote from ordinary life”; it certainly shows agreement that “if a child is not learning good English he is learning bad English, and probably bad habits of thought.”15 But the report and poem diverge; the report states the classics “will always remain, among the best of our inherited possessions, and for all truly civilized people they will always be not only a possession but a vital and enduring influence … ,” yet the status of “civilization,” postwar, is less redeemable in Bridges’s eyes than Newbolt’s. It would seem, through his Neo-Miltonic syllabic meter, that Bridges had discovered and wanted to promote a modern poetic form to replace the classical model, a more capacious, yet still historically respectful English verse form in the post–First World War moment. And yet, like Eliot’s The Waste Land, Bridges’s “Poor Poll” expresses grave doubts that any form can hold in the wake of such tragedy.

Whether Eliot could have spoken to the poet laureate about his metrical experiment is speculative. “Poor Poll” was published in June of 1923, a month before Virginia Woolf finished setting the type on The Waste Land (and after years of Ezra Pound “tightening [its] meter”), so there is little hope for the critical discovery that Bridges’s poem is a kind of shadow poem for Eliot’s. The two poems side by side show Bridges, the elder statesman of English meter, and Eliot, the up-and-comer, engaging with the waning power of the classical concept of “meter” in English. Both poems are macaronic: Eliot’s The Waste Land includes lines in German, French, and Italian as well as references to Swinburne and Tennyson. Bridges’s “Poor Poll” includes lines in German, French, Italian, Latin and Greek (all solidly resting in the twelve-syllable lines) and references Pindar, Dante, and Goethe; Bridges’s Sibyl at Cumae is a parrot in a Miltonic cage. The 97-line poem, at first glance, seems an idle, Browningesque narrative about a man discussing the nature of knowledge with his house parrot, but the poem twists and turns into a metametrical allegory and anticipatory elegy for the loss of a particular understanding of English meter and national culture.

I saw it all, Polly, how when you had call’d for sop

and your good friend the cook came & fill’d up your pan

you yerked it out deftly by beakfuls scattering it

away as far as you might upon the sunny lawn

then summon’d with loud cry the little garden birds 5

to take their feast. Quickly came they flustering around

Ruddock & Merle & Finch squabbling among themselves

nor gave you thanks nor heed while you sat silently

watching, and I beside you in perplexity

lost in the maze of all mystery and all knowledge 10

felt how deep lieth the fount of man’s benevolence

if a bird can share it & take pleasure in it.16

The well-trained bird is able to communicate that he is hungry and that he wants to share with the free garden birds, though given proper names (Ruddock and Merle and Finch) can only “squabble” and “give … no thanks nor heed” of Poll’s kindness; the caged bird has the freedom to communicate and to enact benevolence, whereas the wild birds, though in possession of proper names, cannot properly use speech nor manners. Without proper education, without the proper cage of civilizing meter, the bird-subjects are savage. The captive parrot silently watches as the poet wonders beside her and the other birds eat below her, not giving any explanation for her actions; her ability to communicate is linked only to personal need and to a perceived benevolence, not to any sort of inquiry or understanding—a sharp distinction between beast and poet, and an unsubtle reference to the humanist rhetoric of English education more generally.

Bridges imagines, however, that a certain primitivism could teach the English moralists a thing or two. From lines 13–21 the poet muses as to what the bird’s philosophy would be if she indeed could have one, pitting his own ability to reason (“I thought” [l. 13], “thus reason’d I”[l. 19])—as well as the way that this reasoning power makes him a unified “I”—against “the darkness” in which Poll must live. The “feeble candle-power”(l. 17) of her mind, and her “pall,” is both her insipid nature and now gloomy casket-like cage and, of course, her name. The metrical metaphor of the cage becomes a metaphor for cognition more generally:

If you, my bird, I thought, had a philosophy

it might be a sounder scheme than what our moralists

propound: because thou, Poll, livest ín the darkness 15

which human Reason searching from outside would pierce,

but, being of so feeble a candle-power, can only

show up to view the cloud that it illuminates.

Thus reason’d I: then marvell’d how you can adapt

your wild bird-mood to endure your tame environment 20

the domesticities of English household life

and your small brass-wire cabin, who shdst live on wing

harrying the tropical branch-flowering wilderness:

The bird, here, is a symbol of ignorant doom and of domesticated freedom and wildness; the poem imagines her in “the tropical branch-flowering wilderness”(l. 23) with some regret, as if, like this new meter, the parrot is some tamed poetic impulse that cannot recognize the freedom that the cage of form provides. Indeed, Bridges is already the master of both this form and the bird; notice the possessive “my bird,” and the fact that the diacritical mark on the word “ín” oddly forces us to emphasize that Poll lives in darkness, in the cage, in the poet’s mind (just as, recall, Bridges showed us that he was “the only bird” in his Sonnet 21); her inability to recognize either the metrical or mental “cage” in which she finds herself separates her from man. For a meter that is supposed to avoid wrenched pronunciation, this diacritical mark reminds us, too, that we are “in” a form of the poet’s making, that Bridges is mastering us in a meter that we might not understand.

Bridges then describes how man, like the parrot, has been trained to “follow along” or “mimic” without understanding—a model for metrical mimicry that belies deeper ignorance. Whereas this mimicry in both man and bird is commonly praised as “civilized,” the passage quickly turns to a violent indictment of what the false civilization masks.

Yet Nature gave you a gift of easy mimicry

whereby you have come to win uncanny sympathies 25

and morsell’d utterance of our Germanic talk

as schoolmasters in Greek will flaunt their hackney’d tags

tho’ you with a better ear copy ús more perfectly 30

nor without connotation as when you call’d for sop

in irrepressible blind groping for escape

There is much to sift through here; lines 27–29 directly criticized the pedantic classical schoolmasters, who can have no ear for a dead language and yet flaunt their skills nonetheless. It is also a critique of the pedantry Bridges finds in the teaching of English verse—based on no unified theory of meter, English pedagogues model English verses on the classical system without understanding its inadequacy (derived from the misunderstanding of Latin meter). The ictus on the word “ús” in line 30 is the second diacritical mark that the poet employs in the English text of the poem, guiding the reader’s eye to the word, the reader’s voice to emphasize it, good pupils of (inaccurate, worse than useless) scansion that we are.

In the following line (31), this perfect “copy” of our speech is “not without connotation,” tempting us to dig more deeply in the two lines of Greek. Both Greek lines reiterate through intertext Poll’s ability to mimic and inability to truly reason or understand, and thus also refer to the schoolboys—grown up into Bridges’s reading public—who have ironically repeated the forms of grammar without the wisdom to which line 28’s first Greek tag alludes, from a Pindaric Ode (01.22.04) “speaking to the wise.” To the non-classically trained reader (a growing majority in the 1920s), these tags are mere repetitions to the ignorant, and Bridges keeps it that way. In his gloss he only writes “a Greek iambic line”—showing that the meter is the substance; there are three lines here from three different writers—the second from Thucydides (1.22.4), “a possession for all time.” Thucydides was referring to the afterlife of his own work, but here Bridges may mean that these memorized tags are, for better or worse, ‘for all time’ and that, despite the lack of set quantities in English, the “time” of his syllabic meter allows Thucydides a properly “timed” memorial here. The third and most significant translated intertext is in line 29, from Euripides’ Hippolytus (l.612)—a play all about the broken promises of speech—“my tongue swore but my mind is unsworn.” Though the tag seems to refer back to the parrot, who can talk as if she is tame but possesses a “wild-bird mood,” I find it more useful to think of those parroting schoolboys, formed but not transformed by what their tongues have been trained to repeat—the disappointment of a classical education, as in Bridges’s poem “Flycatchers.” Though the lines in Greek demonstrate Bridges’s ability to absorb it in his English meter, his choice of lines is a subtle critique of the misuse and misunderstanding of classical languages and classical education at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth.

As if to reinforce the disembodiment of the repeating, insipid and unknowing tongue, line 32 strips away all admiration associated with the domestication of the bird’s tongue by showing how barbarous and uncontrollable it really is.

all with that stumpy wooden tongue & vicious beak

that dry whistling shrieking tearing cutting pincer

now eagerly subservient to your cautious claws

exploring all varieties of attitude 35

The “stumpy wooden tongue and vicious beak,” make the bird’s spirit itself seem dangerous and threatening, a wooden tongue that has ‘sworn’ not to produce any wisdom. Indeed, civilized life contains its own potential barbarism. The parrot’s “irrepressible blind groping for escape” and “dry whistling shrieking tearing cutting pincer” are perverse references to the supposed domesticities of English household life. Domesticity and education both contain deeper threats; easy mimicry, under the guise of “cultivation,” forcibly masks a kind of primal urge and robs us of some important natural instinct—quite a comment on English values embedded here. The poem’s pileup of adjectives begins to gain momentum, the phrases “stumpy wooden tongue” and “vicious beak” mimic the threat, with violent dentals and plosives hammering down. Here is no imitation of man’s benevolence; the uncanny ability to imitate human speech is now reduced to an inhuman “dry whistling,” heard in the nasal, guttural trochaic downbeat of “shrieking, tearing, cutting, pincer.” The bird has been driven mad with mimicry into an entirely physical, violent being, its speech ability alienated from the spiritual; it can only explore “all varieties of attitude / in irrepressible blind groping for escape.” Speech, relegated to the insipid, imitating tongue, is itself dissected from any spiritual meaning, just as the bird figure is reduced to a physical object blindly groping for escape from its artificial environment.

Poll’s savage need to escape is personified as “the very figure & image of man’s soul on earth / the almighty cosmic Will fidgeting in a trap” (ll. 37–38),17 but the poet pities the bird, understanding how the rigidities of parroting Greek tags might inspire a kind of “quenchless unknown desire for the unknown life.”

—a very figure & image of man’s soul on earth

the almighty cosmic Will fidgeting in a trap —

in your quenchless unknown desire for the unknown life

of which some homely British sailor robb’d you, alas! 40

‘Tis all that doth your silly thoughts so busy keep

the while you sit moping like Patience on a perch

———Wie viele Tag’ und Nächte bist du geblieben!

La possa delle gambe posta in tregue —

the impeccable spruceness of your grey-feather’d poll 45

a model in hairdressing for the dandiest old Duke

enough to qualify you for the House of Lords

or the Athenaeum Club, to poke among the nobs

great intellectual nobs and literary nobs

scientific nobs and Bishops ex officio: 50

A British sailor has stolen the bird from its origin and the poem faults him (l. 40) for making the bird “endure” English country life. English and British, as concepts, are called to question here: both have become unbearably tame (the sailor is “simple”) and have forgotten some ancient, wilder, and nobler origin. Bridges gestures to the ancient and noble founder of his meter in line 41: “Tis all but doth your silly thoughts so busy keep,” from Milton’s hymn, 12 syllables—a simplified alexandrine line without the traditional caesura. Now, the bird’s thoughts are also simplified, or “silly,” as she sits “moping like Patience on a perch.” We are reminded that mastery is the only true “bird,” not this poor simple model. But Bridges’s eagerness to demonstrate his own mastery causes the poem to flounder a bit, and the next lines, in German and Italian, seem to perform only the fact that they fit into his metrical experiment.

If one is fluent in German, one might recognize this line from Goethe’s “Bericht: Januar”: “Wie viele Tag’ und Nächte bist du geblieben!” (“for how many days and nights have you stayed”). From the notes, we learn that this line earned inclusion because of another metrical variation—the second to last foot is a dactyl in a line of trochees. Goethe’s poem is an address to Cupid, and demands whether he has become “the only master in the house”—another subtle reference to domesticity and domination. The line from Italian, La possa delle gambe posta in tregue (“The position of your legs after a moment of repose”) is from Dante (also a favorite of Eliot’s) and shows the same metrical variation—that is, a trisyllabic foot in place of a two-syllable foot. Bridges absorbs these foreign lines into his English meter, but he has chosen the lines because they demonstrate the three-syllable foot that he believes the “commonest” foot in the English language. These foreign lines, pardon the pun, had their foot in the door, with Bridges’s invented foot for the new century— the Britannic—marching back into a poem based on the meter of the English master Milton. He seems to flaunt his ability to showcase these lines in the narrative that follows, about Poll’s own ability to imitate a “Duke,” a member of the “House of Lords,” or the “great intellectual nobs and literary nobs.” The properly mastered meter will allow imitation in a number of languages and classes, both high and low. Just as Eliot and Pound imitate lower-class dialects, Bridges shows here how Dante’s vernacular form can be called upon to represent elite learning—vernaculars and elite languages change depending on how those great intellectual and literary “nobs” choose to portray and read them.

The performance of the poet’s virtuosity turns elegiac just after its mid-point, around lines 50 to 60. Here, Bridges stops mocking the bird and starts to sound like a man, in very old age, thinking about what he has or has not accomplished:

nor lack you simulation of profoundest wisdom

such as men’s features oft acquire in very old age

by mere cooling of passion & decay of muscle

by faint renunciation even of untold regrets;

who seeing themselves a picture of that wh: man should-be 55

learn almost what it were to be what they are-not.

But you can never have cherish’d a determined hope

consciously to renounce or lose it, you will live

your threescore years & ten idle and puzzle-headed

as any mumping monk in his unfurnish’d cell 60

in peace that, poor Polly, passeth Understanding —

merely because you lack what we men understand

by Understanding. Well! well! That’s the difference

C’est la seule différence, mais c’est important.

Indeed, the poem begins to personify its maker; Bridges has spent his life attempting to educate himself and other poets about the true potential of English verse, only to arrive surrounded by those who are only interested in parroting, imitating, and abstracting meter without truly understanding the history that lies behind it. The “wh: man should be” casually hints at Bridges’s lost hope for pronunciation reform; his own private shorthand, which “should be” recognized but was never adopted. Likewise, he effaces the hope from earlier in the poem that the bird might have some desire for understanding and now accuses it of the sort of “puzzlement” he experienced at the beginning. He gives up, essentially, in lines 57 and 58: “you can never have cherish’d a determined hope / consciously to renounce or lose it,” as the poet has, and, postwar, as the nation has. The bird is “idle and puzzle-headed” and lacks “what we men understand / by Understanding.” Despite this conclusion, the poet still asks the bird, still asks his poem and his hope for poetic meter: “would you change?” He answers his own rhetorical question in the next twenty lines by showing that ignorance is preferable to eventual dismemberment—both physical and metrical.

Lines 63 (“Well, well”) and 64 (“mais”) are the only lines with definite caesuras and both seem to indicate a reckoning; the pause creating a transition between the renounced hopes of the poet for his caged-bird-free-verse and an attempt at justifying his activities in the face of these lost hopes. He begins his address again, “Well! well! that’s the difference / C’est la seule différence, mais c’est important.” The poem immediately imagines the dangers of all of the acts from which reason has been detached:

Ah! your pale sedentary life! but would you change? 65

exchange it for one crowded hour of glorious life,

one blind furious tussle with a madden’d monkey

who would throttle you and throw your crude fragments away

shreds unintelligible of an unmeaning act

dans la profonde horreur de l’éternelle nuit? 70

Why ask? You cannot know. ‘Twas by no choice of yours

that you mischanged for monkeys’ man’s society,

‘twas that British sailor drove you from Paradise —

I’d hold embargoes on such a ghastly traffic. 75

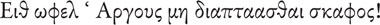

Why ask?, he seems to ask himself, concluding again, “you cannot know.” But then the freedom to have “one crowded hour of glorious life” freed from the civilized cage, even if that hour risks destruction and dismemberment, is called “Paradise.” The Greek line he quotes in line 74 is telling—it’s the first line of Euripides’s Medea, in which the nurse wishes that the ship had never set sail from Argos to arrive in Colchis18 (where Medea commits the darkest of her tragic acts). Medea, the foreigner who is accused of speaking a “barbarous” language to go along with her “barbarous” acts, has also, in effect, been “stolen away” across the water. Bridges, in his ironic stance against all unregulated foreignness in the English language, writes, “I’d hold embargoes on such ghastly traffic,” and though he seems to assert that he would protect us from ruin, we know that his attitude toward English meter has been, by the 1920s, irreparably poisoned.

The sustained address to the parrot throughout the poem can be read as a subjective slide into the poet’s consideration of his own dissatisfaction with his self and his craft. The “I” in the poem moves through states of perception: “I saw”; “I beside you in perplexity / lost in a the maze of all mystery and all knowledge, felt how deeply”; “Thus reason’d I”; “I’d hold embargoes”; and finally, the movement that begins on line 76, “I am writing verses to you.” Bridges flaunts the poem’s antivocality. The diacritical marks must be seen; the dead languages cannot possibly be heard. Though the poet is writing to a bird, his grief is for English poetry, and an audience for that poetry who may be “absolument incapable de les comprendre, / Tu Polle, nescis ista nec potes scrire” —both the French and Latin again telling, in a foreign tongue, how all reason is foreign to a simple creature who can only imitate—she does not know these things and is not able to know them.

I am writing verses to you & grieve that you shd be

absolument incapable de les comprendre,

Tu, Polle, nescis ista nec potes scrire: --

Alas! Iambic, scazon and alexandrine,

spondee or choriamb, all is alike to you — 80

my well-continued fanciful experiment

wherein so many strange verses amalgamate

on the secure bedrock of Milton’s prosody:

not but that when I speak you will incline an ear

in critical attention lest by chánce I míght 85

póssibly say sómething that was worth repeating:

I am adding (do you think?) pages to literature

that gouty excrement of human intellect

accumulating slowly & everlastingly

depositing, like guano on the Peruvian shore, 90

to be perhaps exhumed in some remotest age

(piis secunda, vate me, detur fuga)

to fertilize the scanty dwarf’d intelligence

of a new race of beings the unhallow’d offspring

of them who shall have quite dismember’d & destroy’d 95

our temple of Christian faith & fair Hellenic art

just as that monkey would, poor Polly, have done for you.

These meters, in particular, demonstrate our inability to realize the terms of meter in the early twentieth century—our guide, the scazon from Martial, in which Bridges changes the name to “Polle,” should lead us to understand that line 79 is a quantitative scazon in English; lines 80 and 82 are also English quantitative lines, but though he is littering his lines with clues about the foundations and future of his English meter, their meaning is lost on us.

The poem elegizes what the bird-as-form, bird-as-English-tongue, cannot know. “Alas! Iambic, scazon and alexandrine, / spondee or choriamb, all is alike to you / — my well-continued fanciful experiment / wherein so many strange verses amalgamate / on the secure bedrock of Milton’s prosody” (ll. 79–83). The metrical forms are named, here, like the proper names given to the squabbling birds at the beginning of the poem. The geologic amalgamation of these different forms on the bedrock of Milton should be triumphant, and yet the poem throws its metrical names out as if to challenge the reader to appreciate this gift, the parrot/poet here bored like the bird who shares with the wild birds who disregard his generosity—take it: “all is alike to you.”

Who could go through the poem and truly distinguish one strange verse form from another, the poem seems to ask. Who would even recognize the bedrock of Milton? This lack of critical understanding is signified in the most sustained use of diacritical marks to indicate accent in the entire poem. As if to show that England will not and cannot believe what it cannot see, Bridges writes: “not that but when I speak you will incline an ear / in critical attention lest by chánce I míght / póssibly say sómething that was worth repeating” (ll. 84–86). The poem finally shifts the poet-parrot to the poet-reader, that is, the listening reading public that can only hear experiments, not detect them visually. It is only “when I speak” that we “incline an ear” with critical attention, not when we read. By slipping into iambic pentameter and then reversing the foot in line 86, the poem mocks what is easily repeated out loud and demonstrates that perhaps the preservation of these forms will never be correctly repeated because of the level of training required to read them correctly, and the level of inquiry required to even detect that they exist.

After the “worth repeating:” we might expect to find a list of repeatable forms, a final gesture of what we might still be expected to learn. His parenthetic statement asks us to reflect, finally, after an entire poem of proving that our intellect is not capable of adequate reflection (do you think? [l. 59]). This question at the end of the poem seems an ironic question to the answer his other question set out: “Why ask? You cannot know,” you cannot think, you do not think. Literature becomes mere “pages”— “that gouty excrement of human intellect / accumulating slowly & everlastingly / depositing, like guano on the Peruvian shore, / to be perhaps exhumed in some remotest age” (ll. 87–89). The reference to guano here is particularly telling because of the influence of Huck Gibb’s money on the progress of the Oxford English Dictionary. Gibb’s family fortune, made by the export of Peruvian guano, loaned Gilbert Murray enough funds to publish part one of the dictionary in 1884. Despite this reference to the enormous success in preservation for English language and literature, one dependent on accumulation and standardization, the intellect-as-excrement image is both humorous and damning. Bridges seems to think that his intellectual experiment has already been buried in his lifetime.

Though, once spoken, the poem might be “worth repeating,” it laments its own eventual future: both disremembered (never repeated) and its complex metrics, its carefully composed skeletal structures of prosody, essentially “dismembered”19—torn limb from limb. The fate of classical prosody, the “temple of Christian faith & fair Hellenic art,” is told in the last Latin tag, now sequestered to the parenthesis piis secunda, vate me, detur fuga. This line, from Horace’s sixteenth epode “to the Roman people” (Ad Populum Romanium), tempts a reading of England’s future like the fate of Rome Horace describes: “this land shall again be possessed by wild beasts…. The victorious barbarian shall trample upon the ashes of the city … there can be no better destination than this; namely, to go wherever our feet will carry us… .”20 But where would England’s metrical feet carry her? The dismembered feet of England’s meters were already scattered throughout the poetry of the 1920s, destined to survive the rest of the twentieth century only in metrical fragments, ghosts of a civilization that was never quite successful. Bridges, talking to his brass-wire-entrapped parrot, changes the Latin form in his quotation from “datur” to “detur,” a subtle move to the modal to show how escape from ignorance is not just one possibility, but the only possibility; one he exemplified by a life-time of metrical experimentation and one that we are only at the beginning stages of recovering. If one studies the history of meter today, one will see that it involves reassessing the myriad assumptions about meter, the confusions and complications that he tried—as any metrists today tries in his or her own way—to elucidate.

Alice Meynell’s “English Metres”

The story I have begun to tell here is a narrative of masculinity, of a male-centric, Anglo-Saxon identification that suppresses and ignores the ways that women poets writing concurrently were participating in and troubling concepts of English national meter and English national identity. I have not investigated, nor have I given ample space to investigating the implications of the homosociality in the communities imagined by Gerard Manley Hopkins and Wilfred Owen. Nor does space permit me to theorize about the implications of homosexual identification in each of these poet’s oeuvres; both of them were hostile toward women at different points in their careers and believed women to be lesser poets: poetasters and poetesses, mere versifiers (attributed with lesser intellect, in Hopkins, and home-front ignorance, in Sassoon, though Owen was a great admirer of Elizabeth Barrett Browning). There is much work to be done in the ways that assumptions about gender and education impact and play out in the metrical discourses of the period. From Anna Letitia Barbauld’s support of the schoolroom-as-nation to the countless schoolmistresses who wrote metrical histories, grammar books, song-books, and drills (from Jane Bourne to Veronica Vassey), to the slant-rhymes of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to the experiments of the hundreds of “poetesses” (male or female) in the nineteenth century and the subsequent modernist reception, rejection, and repression of these experiments (like Christina Rossetti’s “goblin metrics,” so expertly theorized by Anne Jamison in Poetics en Passant), the gendering of meter—both English and classical, deserves sustained study. Henry Newbolt learned a great deal about meter from Mary Coleridge, and Coventry Patmore learned from Alice Meynell. The absence of women as main characters in this study by no means indicates that women were not participating in, creating, critiquing, and influencing metrical discourses in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yopie Prins’s work in Victorian Sappho (Princeton, 1999) is foundational; Ladies’ Greek (2013) will be as well. Work by Jason Rudy, Linda K. Hughes, Linda Peterson, Emma Major, Ben Glaser, Carrie Preston, and Emily Harrington has begun to correct these male-centric metrical narratives. Because few female poets, beyond Alice Meynell and Adelaide Crapsey, published prosodic treatises or manuals, I have left them out of this initial study, just as I have left out a good many male poets who also wrote about meter (it was such a common practice that nearly every poet wrote something about his or her metrical practice in a private letter at some point). I hope that this book serves as a first step toward expanding our understanding of metrical discourse to include all of the narratives of metrical and national identity that have been suppressed by literary history. As a gesture toward the work that needs to be done, and that will be done, in this area, I want to close this book with another 1923 poem by a poet who participated in the abstraction of meter as corporeally, natively English in complicated and lasting ways. In the same year that Eliot published The Waste Land and Bridges published “Poor Poll,” Alice Meynell published “The English Metres” in her collected Poems. Wilfred Owen’s Poems, edited by Sassoon, had been published in 1920 and reprinted in 1921, and Hopkins’s Poems, edited by Bridges, had been receiving the rare baffled review since its appearance in 1918. Like all of the poets I discuss in this project, Meynell meditates on metrical form in the broader contexts of English national culture in her poems, “The Laws of Verse” and “The English Metres.” These poems provide a suitable postscript to a project in which many poets were concerned that the fate of the “English metres” in the twentieth century would mean their erasure from the script of literary history altogether.

Like Robert Bridges in Sonnet 21, and like Hopkins in “The Windhover,” in Alice Meynell’s “The Laws of Verse,” she makes verse itself the bird, not a poetic inspiration that will fill a form:

THE LAWS OF VERSE

Dear Laws, come to my breast!

Take all my frame, and make your close arms meet

Around me; and so ruled, so warm, so pressed,

I breathe, aware; I feel my wild heart beat.

Dear Laws, be wings to me!

The feather merely floats. Oh, be it heard

Through weight of life—the skylark’s gravity—

That I am not a feather, but a bird.

Here, Meynell addresses Shelley, Bridges, and the laws of verse themselves. The laws of verse seem to be the laws of Christ, of devotion, but she is also the master of these laws.

Addressing meter as “English” in “The English Metres” staunchly positions Meynell among those who believe that classical feet are not only acceptable but perhaps also laudable as representatives of the measure of English poetry. Meynell does not bother to justify her terminology—she writes as if the Greek words for metrical feet are not only appropriate but as if they have become a crucial part of an English landscape. Despite her adoption and naturalization of these laws, this is another subtle elegy for an understanding of meter that will disappear along with classical education. Like Saintsbury, Meynell asserts that “English meters” exist and have characteristics that align them with the nation, and yet there is a metametrical narrative at work in this poem as well, in which the poet mourns the poem’s inability to be understood as a metrical allegory.

THE ENGLISH METRES

The rooted liberty of flowers in the breeze

Is theirs, by national luck impulsive, terse,

Tethered, uncaptured, rules obeyed ‘at ease’

Time-strengthened laws of verse.

Or they are like our seasons that admit 5

Inflexion, not infraction: Autumn hoar,

Winter more tender than our thoughts of it,

But a year’s steadfast four.

Redundant syllables of Summer rain,

And displaced accents of authentic Spring; 10

Spondaic clouds above a gusty plain

With dactyls on the wing.

Not Common Law, but Equity, is theirs —

Our metres; play and agile foot askance,

And distance, beckoning, blithely rhyming pairs, 15

Unknown to classic France;

Unknown to Italy. Ay, count, collate,

Latins! With eye foreseeing on the time

And numbered fingers, and approaching fate

On the appropriate rhyme. 20

Nay, nobly our grave measures are decreed:

Heroic, Alexandrine with the stay,

Deliberate; or else like him whose speed

Did outrun Peter, urgent in the break of day. (ll. 1–24)

Though these poems were published in 1923, we see that they are rooted in Edwardian concepts of metrical freedom and wartime conceptions of poetic form. For instance, the first stanza calls English meter “by national luck impulsive, terse, / Tethered, uncaptured, / rules obeyed ‘at ease’ / Time-strength-ened laws of verse.” Meter itself is like a soldier ‘at ease,’ still serving the country, but not bound to perform any duty. English laws of verse are “rooted” in history, but this history has taught them to strive toward freedom. Her own diction is “terse” and “tethered” here, as it describes the “impulsive” and “uncaptured” laws of verse, demonstrating that her own practice shows that she admits to adhering to some sort of law, though she also admits that this law has not been “captured” by any adequate description. The English laws of verse are always rooted in England, but they are still “at liberty,” though “by national luck” (and the cultural contexts I outline in the six chapters of this project), they have been strengthened and codified somewhat by the passage of time.

Meynell measures time by metrical seasons (“a year’s steadfast four”) and, like meter, the four seasons “admit inflexion, not infraction.” Just like meter, the seasons might be different than our expectations of them: “winter more tender than our thoughts of it.” Her own four-beat lines, here, are as inevitable as the seasons but nonetheless subtler than any description. In the third stanza, nature is allegorized into meter “redundant syllables of Summer rain, / And displaced accents of authentic Spring.” The metrical feet, rather than taking on the characteristics of actual feet, sprout wings and fly: spondees are clouds, dactyls are “on the wing.” Rather than reference the standard iamb and trochee here, Meynell inserts the most controversial metrical feet (the spondee and dactyl) as if to show how natural these have become—an inevitable part of the English landscape. The “bird” as inspiration, as metrical mastery, as repeating and trapped parrot, has become the metrical foot itself: not the poet or the poem, but that term with which we describe the poem is “on the wing.”

Nor does Meynell adhere to a strict iambic meter, though she could be alluding to “heroic” and “urgent” iambs in Saintsbury’s terms in stanza 5. The poem welcomes dactyls and spondees, and it is not, though it seems like it almost should be, a lesson in expressive reading. Unlike Coleridge’s “Lesson for a Boy,” Meynell does not employ dactylic feet in the line “with dactyls on the wing,” nor are there spondees in the line “spondaic clouds above a gusty plain.” Authentic spring, in Meynell’s metrical allegory is not configured in the line through displaced accents, and even the amphibrach and dactyl of “redundant syllables” seem altogether necessary. There is no stanza in which the form, actual or allegorical, imposes itself; the three lines of pentameter followed by one of trimeter never succumb to a strict iambic except in the playful line in stanza 4: “Our metres; play and agile foot askance.” In Meynell’s poem, agile feet of English meter can play without fear of reproach.

And yet, the fourth stanza alludes to Common Law versus Equity, thus referring to a legal, rather than natural, origin of “our metres.” English meters have “Equity” instead of “Common Law,” where metrical form would be decided solely on precedent and custom (despite how they are rooted in history). By using this legal terminology, Meynell alludes to the British and American system of ethical modification to the rule of law. Modification based on fairness is the rule to which Meynell refers here, and this flexible interpretation of the laws of verse is “unknown to classic France,” and “unknown to Italy” (in stanza 5). Though the English meters are natural, their modification—indeed, codification—might be seen as unnatural or external. The English meters are defined in opposition to their continental counterparts. Even the Latins are seen as too strict, “with eye foreseeing on the time / And numbered fingers, and approaching fate, / On the appropriate rhyme,” their verses leading inevitably and predictably to a conclusion we can count on.

“Nay nobly our grave measures are decreed:” she refers to the history of English verse in this final stanza—the heroic couplet, (those “distant, beckoning, blithely rhyming pairs”) and the Alexandrine, but again, “decreed” and “stay” have a slightly legal tone to them. English meters have all the freedom they need in 1923, and yet unless they are “decreed” noble, deliberate, they might take on too much speed. John (20:1–9) outruns Peter “urgent in the break of day,” to see the resurrected Christ. Here, the poem favors the nobility, the heroism, and the deliberation of the national meters, fearing that without a lawful decree, without the “rooted liberty,” verse might be too young, too eager, too quick to discard the careful wisdom of the past. Because both John and Peter are disciples to a “higher law” (Meynell is Catholic), their reticence to let go of the laws of English meter and the freedom they entail, coupled with the eagerness to rush into a new poetic era, are written into this final stanza.

This reticence, born of a Victorian education that respected the misunderstood laws of verse; this freedom, from Edwardian education and the changing conceptions of poetic form (and Englishness in general); and this eagerness to change the law entirely, especially in the 1920s, are all products of cultural change that affected the status of poetry in England. Like Bridges’s elegiac turn in “Poor Poll,” Meynell’s “English Metres” is an ode to English metrical freedom at the same time that it is an elegy for those who will not understand English meters in the way that Meynell has been deliberately, nobly, luckily educated to understand them. As twenty-first-century critics, we might prefer this eagerness; but we must understand that our critical in-ability to read meter historically is a culturally produced phenomenon, one that this book takes slow, deliberate steps to retrace.

In addition to recovering and recontextualizing poets whose projects seem to fall outside of the received narrative of English literature’s formal evolution— most importantly, reading metrical projects as part of a larger metrical discourse, not discarding formal poetics as merely “formal,” and understanding that “form” meant different things to different poets at different moments— historical prosody reveals how the history of our profession is intertwined with the history of form. Our traditional approach to meter has been to assume that it imposes “order” onto emotions and onto experience. But what if, as I have shown, the allegory for “order” is destabilized to begin with? Maybe the emotional and experiential elements of the poem are not bound to an agreed-upon stability. The instability generated by multiple and competing metrical discourses correlated with an unstable national culture in the nineteenth century, in particular. Poets may identify with certain forms at certain moments and use and manipulate formal conventions, but a ballad written by Wordsworth comments on those conventions differently, say, than a ballad written as an imitation of a popular music hall song at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries or, indeed, differently than the lyrics to a popular song on the radio today. Metrical forms circulate, change, and accrue different meanings at different moments, and this is as readable and important in our understanding of the formation of “poetry” as a concept as the poems themselves.

If we accept that many of our contemporary associations with the word “meter” became fixed in the nineteenth century, what other ways were educational and institutional discourses influencing the reception of poetry in the twentieth century? What other assumptions might we call to question? This book has started to bring to light many competing nineteenth-century prosodic theories and, more importantly, to show what was at stake for the poets and prosodists who attempted, and often failed, to institute these new and various English meters. I realize, as I hope you do as well, that I cannot account for all varieties of metrical discourse in the nineteenth century. Rather, I am learning to ask, when poets were inventing or experimenting with prosodic systems, with what else, in addition to the measure of the line, were they wrestling? Why was the question of English meter even a question? How did meter permeate discussions of religion, education, psychology, and disciplinary formation in general? What does “meter” mean if we refuse to take for granted that our traditional understanding of iambs and trochees is an artificial, cultural construct? The “rise and fall” of meter I narrate here certainly shows the broad sweep of excitement about defining English meter in a time of disciplinary formation and change (the decline of classics, the rise of “English”), but as these disciplines were also calling up metrical narratives in new ways at different moments, what meter “means” changes from one community to the next at each moment. “Meter” and metrical discourse is constantly rising and falling; that is, its status can be “on the rise” in one community just as it is falling out of favor in another, depending on what associations these communities are making, and what battles are being played out and for what reasons. But just because forms or conventions might be best understood as unstable, it does not mean that we should not honor them anyway; realizing and gesturing to an inherent instability at the heart of “formal” discourse does not close the aesthetic possibilities of a poem, shuttling it into cultural studies and considerations of material culture. Rather, considering the political and aesthetic dimensions of poetry’s instability might allow us to look closely at the places where forms seem “fixed,” asking why that is the case. Paying attention to the historical contingencies of poetic form at the same time that we attend to the poem both broadens and deepens our engagement with poems in/and history and also gives us the opportunity to question the assumptions that we make as readers when we encounter texts.

All of this is to say, my historical approach to prosody is to provide a more nuanced picture of the formal contingencies of the poem at a specific moment, while also remaining aware of why we are invested in this particular practice. The narrative of competing metrical forms has multiple strands that apply to a variety of cultural domains: our associations between certain metrical forms and certain social classes, between metrical tropes and gender, and between perceived metrical stability and perceived institutional or ideologically complex hierarchies of power (the church, the domestic sphere). Providing concurrent formal histories—incomplete though they may be—to these generative allegorical readings of prosodic form, are important parts of the practice of historical prosody. Historical prosody is by no means limited to meter; meter is just one part of it, and much work needs to be done on pronunciation, rhyme, rhythm, alliteration,21 and so on. Likewise, work beyond the prosody of the poem toward the history of formal circulation can, should, and has recently begun to extend beyond England and into the colonial world, as well as more deeply into the interiors of domestic spaces and concepts of gendered poetics.22 This book focuses on meter because meter is where we have stabilized these concepts—twentieth-century poetic criticism has, largely, relied on concepts of genre and form in order to narrate the nineteenth century as a foil to the twentieth. The abstraction of meter, its lack of historical specificity in mid-twentieth-century criticism, I argue, is due to these disorganized, multiple, and competing narratives. It is this failure to achieve a definitive reading— despite the desire to achieve it—that I find heartening about the project of historical prosody. That is, even in a text as didactic as the prosody handbook or an author’s notes on how to read a poem, I find the struggle to instruct the reader, and the inherent acknowledgment that the metrical structure of the poem will not successfully transfer across readers and across time, expressive of the many ways English national identity—and stable “identity” in general— was and is fundamentally in flux.23

Rather than collapse the metrical history into a simple opposition of Anglo-Saxon or classical ideologies, I have read these myths of origin as two of many that come into play when poets approach metrical form. Beyond the history of the language, the development of industrial culture, mechanization, changes in musical culture, different approaches to the body, to performance, to all kinds of systems and orders, played some role in a poet’s thinking about poetic form. All of these influences—transatlantic and cross-channel poetics, translations and foreign travel—might be important and generative considerations for poets experimenting with English poetic form. That many poets were attracted to a stable metrical system is clear, and their attempts to achieve and define these systems and what those attempts teach us is the subject of this study. But the very unfixed nature of many metrical conventions, on the one hand, and the too-fixed nature of their abstract definitions that then inspired a model for endless critical discourse, on the other hand—created anxiety for poetry readers of every class and educational background. And this anxiety about form still pervades the discipline of English literary studies, where “poetic form” appears as that last bastion of elite training, the one place where we have a right to a “right” answer, the place where a poem’s meaning might be explained, once and for all, with the help of a teacher trained in the system that will demystify it. And yet, as I have been arguing, the very poets with whom we have charged the responsibility of fixing these conventions and metrical systems doubted the sustainability of conventional forms, doubted their security for the future of the English language and English culture. They knew, or were beginning to realize, that many systems were possible for English verse but the contingencies of pedagogy meant that these various possibilities— those that would, perhaps, reveal the hybrid nature of the English language— might create insecurity in the young student/subject, and so that is not how we have been teaching English meter. And even this realization—that one model would prevail and be called quintessentially “English” at the expense of other possible ways of reading both “poetry” and “verse,” of identifying “Englishness” within literary studies—was figured metrically, formally, in the early twentieth century by the poets who Modernism has buried. It is up to us to exhume these multitudinous metrical narratives so that we might further understand our own unstable relationship to poetic form and culture and to generate new ways of thinking about poetic form’s historical contingencies as well as the contingencies of our own contemporary reading practices.