Introduction: The Failure of Meter

1. The records to which I refer here were destroyed in the Second World War and not the First World War.

2. Versification, according to its bibliographic record, was “a monthly magazine of measure and metre.” Only two issues are now listed in the online catalog and both are missing. In The Western Antiquary: Or, Devon and Cornwall notebook, vol. 11, the editor records, “We have received several numbers of a little serial called ‘Versification,’ edited by Alfred Nutting. Its chief feature is the publication of original poems by amateur authors, to which the editor appends critical notes as to the style and quality of compositions.” (“Current Literature,” The Western Antiquary, 30).

3. Bradbury and McFarlane, “The Name and Nature of Modernism,” 21.

4. Nadel, Cambridge Introduction to Ezra Pound, 26.

5. Cavitch, “Stephen Crane’s Refrain,” 33.

6. Beasley, Theorists of Modernist Poetry, 1.

7. Lewis, Cambridge Introduction to Modernism, 4, 3.

8. Herbert Read, in 1933, writes: “it is not so much a revolution, which implies a turning over, even a turning back, but rather a break-up, a devolution, some would say a dissolution. Its character is catastrophic” (Art Now, 58–59); C. S. Lewis, in 1954, writes: “I do not see how anyone can doubt that modern poetry is not only a greater novelty than any other ‘new poetry’ but new in a new way, almost a new dimension.” (De Descriptione Temporum: An Inaugural Lecture, 13).

9. Bradbury and McFarlane, Modernism, 21.

10. Cavitch writes: “the perpetuation of such liberation narratives is powerfully motivated, and deeply inscribed in our scholarship, our course syllabi, and our anthologies and editions” (“Stephen Crane’s Refrain,” 33).

11. This literary historical narrative, I am arguing, is largely based on reactions to the poetry of the movements associated with the modernist avant-garde as well as reviews of these poems by the scholars now known as the “New Critics.” For “difficulty” in modern poetry, see Steiner, “On Difficulty,” 263–76; Christie, “A Recent History of Poetic Difficulty,” 539–64.

12. Pound, The Pisan Cantos.

13. Prins, “Nineteenth-Century Homers and the Hexameter Mania,” 229–56.

14. For recent exciting work in Victorian prosody, see Hughes et al., in the “Victorian Prosody” special issue of Victorian Poetry, edited by Meredith Martin and Yisrael Levin.

15. This patriotic narrative of curricular reform in the English education system was often figured as an issue that pertained only to the men who would grow up to become soldiers and, indeed, the masculine aspects of English rhythm’s march through time was certainly a trope that appeared again and again. But I want to signal that this narrative was promoted and disseminated by schoolmistresses in the classroom and by the female authors who wrote the majority of English grammar books in the nineteenth century. Poets like Alice Meynell, Mary Coleridge, and Jessie Pope also participated in a discourse that promoted the concept of English meter’s preexistence in the heartbeats and footsteps of particularly English bodies, a discourse, I argue, that escalates and is articulated in a particularly nationalistic way at the turn of the twentieth century.

16. Doyle, English and Englishness, 19.

17. Beer, Open Fields; Dowling, Language and Decadence in the Victorian Fin de Siècle; Mugglestone, Lost for Words.

18. Hugh Blair, Lectures on Belles Lettres and Rhetoric, 227.

19. Fussell, Theory of Prosody in Eighteenth-Century England, 3.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Abbott, ed., The Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges, 231.

23. See Armstrong, Victorian Poetry; Prins, “Victorian Meters,” 89–113; Cavitch, “Stephen Crane’s Refrain,” 33–54; Hughes The Cambridge Introduction to Victorian Poetry; and especially Jamison, Poetics en Passant.

24. Levine, “Formal Pasts and Formal Possibilities in English Studies,” 1241–56.

25. In Hardy’s Metres and Victorian Prosody, Taylor begins to reveal the complexity of Victorian metrical criticism. Though focused primarily on Hardy’s verse forms, the early chapters argue for the “abstraction” of meter into a system or “law” against which the “freedom” of spoken language, with its various unmeasured quantities, was in tension. Markley’s Stateliest Measures reveals Tennyson’s classical metrical experiments in English were meant to evoke a kind of national Hellenism.

Chapter 1: The History of Meter

1. Enfield, The Speaker.

2. Guillory, “Mute Inglorious Miltons,” 100.

3. Ibid., 101.

4. Nonconforming Protestants, but also Quakers, Catholics, and Jews.

5. Rule V, Enfield, The Speaker, 7.

6. Walker, Elements of Elocution, 263.

7. “Prosodic regularity forces the ordering of the perceiver’s mind so that it may be in a condition to receive the ordered moral matter of the poem, just as, in ethics and religion, a conscious regularizing of principles and even of daily habits is the necessary condition for the growth of piety” (Fussell, Theory of Prosody in Eighteenth-Century England, 43).

8. Burt, A Metrical Epitome of the History of England Prior to the Reign of George the First, vii.

9. It is distinct, too from the “metrical romances” of earlier centuries, romances that were being translated and circulated in the nineteenth century. For more on the popularity of the metrical romance in the early nineteenth century, see St. Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period.

10. Cf. Prins, “Metrical Translation: Nineteenth-Century Homers and the Hexameter Mania.”

11. Eighteen thousand copies sold in ten years; 100,000 by 1875 (from Cunningham, The Victorians: An Anthology of Poetry and Poetics, 72).

12. Published in 1587 and reprinted in 1815 (this is the edition I am quoting), the Mirror for Magistrates, edited by Joseph Haselwood was included in the eighteenth century in Elizabeth Cooper’s The Muses Library (1737) and Edward Capell’s Prolusions (1760) before Thomas Warton’s A History of English Poetry (1781) popularized it once more. John Haselwood edited an edition in 1815 for Longman and based his on the 1587 edition. The Mirror was also reprinted in the series Cassell’s Library of English Literature in the volume Shorter English Poems, selected, edited and arranged by Henry Morley (1883).

13. De Sackville, surely the most famous author of The Mirror, writes how he was inspired much like Caedmon: awakened from sleep, or in a sleepy dream, he is visited by spirits who force him to write: “one after one, they came in strange attire / but some with wounds and blood were so disguised / you scarcely could by reason’s aid aspire / to know what war such sundry death’s devised” (Cassell’s Library, 183).

14. A three-part series in English, Roman, and Hellenic history was written “after the method of Dr. Grey” at midcentury: Grey, Wilcongsau, or, Mnemonic hexameters: after the method of the Memoria Technica of Dr. Grey: English History; First Thebaloi, or, Mnemonic Hexameters, after the method of the Memoria Technica of Dr. Grey: Hellenic History; and Regdol or Mnemonic Hexameters after the method of the Memoria Technica of Dr. Grey: Roman History.

15. Grey, Memoria Technica, vii–viii.

16. He admits that he lifted the ancient history from “Mr. Hooke, the Roman Historian” and took parts of A Poetical Chronology of the Kings of England from The Gentleman’s Magazine. Valpy, A Poetical Chronology of the Kings of England, 4.

17. “Poetical Chronology of the Kings of England,” T. M. Esq. in “Poetical Essays,” Gentleman’s Magazine printed in serial, monthly between September 1773–January 1774, 454–55, 511, 571, 613, 655.

18. Ibid., 5, 6.

19. Metrical histories of Charles the Great and the War of the Roses, for example, focused on specific events in English history.

20. There were easily three times as many metrical histories, epitomes, and chronicles published in the nineteenth century as in the eighteenth century.

21. Poor Edward the Fifth was young killed in his bed

By his uncle, Richard, who was knocked on the head

By Henry the Seventh, who in fame grew big

And Henry the Eighth, who was fat as a pig! (Collins, Chapter of Kings)

22. See Strabone, “Samuel Johnson Standardizer of English, Preserver of Gaelic”; Strabone, Grammarians and Barbarians: How the vernacular revival transformed British literature and identity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, 69; and Elfenbein, Romanticism and the Rise of English.

23. Dibdin. A Metrical History of England; or, Recollections in Rhyme of some of the most prominent Features in our National Chronology, from the Landing of Julius Caesar to the Commencement of the Regency in 1812 in two volumes. Although a review in The Monthly Catalogue faults the compilation as being “an amplification of the well-known ‘Chapter of Kings,’” it admits that it is “something more” (Francis Hodgson, Review of Dibdin, 437).

24. A clever idea in theory, but in practice his narrative vacillates between heroic couplets and ballad meter. Herbert F. Tucker, in Epic: Britain’s Heroic Muse 1790– 1910 writes, “one hardly knows what to call” Dibdin’s history (150) and concludes that the poem displays “a nationalism secure enough to make fun of itself ” (151).

25. Hall, “At Home With History: Macaulay and The History of England,” At Home with Empire, 32–52, as well as Hall, McClelland, and Rendall, Defining the Victorian Nation.

26. London University’s matriculation examination made history compulsory from the start (1838), and it was included in examination requirements of the Civil Service (1854–55, 1870) and the Army (1870). The Schools Inquiry Commission and publishing house data shows that the four most popular books were Mangnall’s Historical and Miscellaneous Questions for the use of young people, reprinted many times between 1804 and 1891; Gleig’s School History of England;, W. F. Collier’s History of the British Empire; and Ince’s An Outline of English History. From Howat, “The Nineteenth-Century History Textbook,” 147–58.

27. “In committing the fibre of a material so raw to the metrical loom, a coarse tissue must necessarily be worked out—coarse but genuine—a greater regard having been paid to its durability than its appearance” (Raymond, Chronicles of England, xvii).

28. Rossendale, History of the Kings and Queens of England from King Egbert to Queen Victoria, preface, no page number.

29. Montefiore, The History of England in Verse (London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, 1876), 2.

30. Robson, “Standing on the Burning Deck: Poetry, Performance, History,” 148–62.

31. Other books with mnemonic ciphers include Feinaigle, The New Art of Memory Founded on the Principles Taught by Gregor von Feinaigle; Fauvel-Gouraud and Miles Phreno-mnemotechny; and Fuller, The Art of Memory: In Byron’s Don Juan, he jokes about Donna Inez’s perfect memory, which did not need the aid of Feinaigle the hack:

—memory was a mine; she knew by heart

All Calderon and the greater part of Lopé

So that if any actor missed his part

She could have served him for the prompter’s copy;

For her Feinaigle’s were an useless art,

And he himself obliged to shut up shop, — he

Could never make a memory so fine as

That which adorned the brain of Donna Inez.

(Don Juan, I, xi, 1818)

Lewis Carroll’s Memoria Technica (s.n.), which was a numerical cipher but certainly influenced by the new memorization techniques, wasn’t published widely until 1888 (though there was a small 1877 edition).

32. Bourne, Granny’s History of England in Rhyme, 1.

33. Mann, School Recreations and Amusements, Being a Companion Volume to King’s School Interests and Duties, Prepared Especially for Teachers’ Reading Circles, 175–76.

34. Stray and Sutherland, “Mass Markets: Education,” 359–81, 359, 360.

35. I am moving quickly through the period leading up to the 1860 education reforms; Richardson’s Literature, Education, and Romanticism: Reading as Social Practice 1780–1832 provides an excellent survey of broad educational movements in the period.

36. See Mugglestone, Lost for Words; Dowling, Language and Decadence in the Victorian Fin de Siècle; Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture in Britain 1750–1914; and Strabone, Grammarians and Barbarians. Also, Tony Crowley Standard English and the Politics of Language; St. Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period; Cohen, “Whittier, Ballad Reading, and the Culture of Nineteenth–Century Poetry.”

37. Cf. Cureton, “A Disciplinary Map for Verse Study.”

38. I have benefited from the work of English language historians Manfred Görlach and Ian Michael, especially, as guides to the development of grammar teaching in nineteenth-century England. See Görlach, English in Nineteenth-Century England: An Introduction and Michael, The Teaching of English from the Sixteenth Century to 1870.

39. See Spoel, “Rereading the Elocutionists: The Rhetoric of Thomas Sheridan’s ‘A Course of Lectures on Elocution’ and John Walker’s ‘Elements of Elocution.’”

40. See Woods, “The Cultural Tradition of Nineteenth-Century ‘Traditional’ Grammar Teaching”; Fries, “The Rules of Common School Grammars.”

41. Though Elfenbein’s recent Romanticism and the Rise of English takes into account grammatical debates about usage in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, prosody has received little attention.

42. Strabone, “Samuel Johnson: Standardizer of English, Preserver of Gaelic.”

43. Johnson, Dictionary; Fussell, Theory of Prosody in Eighteenth Century England, 25–26. Fussell speculates that “an acquaintance with John Rice’s Introductions to the Art of Reading with Energy and Propriety” (London, 1765) may have caused Johnson to add the new sentence to his revision of The Dictionary” (26, n.116).

44. Percy, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry: Consisting of Old Heroic Ballads, Songs, and other Pieces of our earlier Poets, (Chiefly of the Lyric kind.) Together with some few of later Date.

45. Strabone, Barbarians and Grammarians, 283.

46. Percy, Reliques, 261.

47. Review of King Alfred’s Anglo-Saxon Version of the Metres of Boethius, with an English translation and notes, in A Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. 158: 49.

48. Turner, History of England, 264–65.

49. Some important early nineteenth-century publications in Anglo-Saxon studies were Thomas Whitaker’s 1813 version of Piers Plowman; John J. Conybeare’s 1814 “English Paraphrase” of Beowulf contained in Observations on the metre of the Anglo-Saxon poetry; further observations on the poetry of our Anglo-Saxon ancestors (London: Archaeologia, 1814); Conybeare, Illustrations of Anglo-Saxon Poetry; Joseph Bosworth’s Elements of Anglo-Saxon Grammar; and Kemble, A Translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf. Versions of Beowulf appeared in nearly every decade of the nineteenth century thereafter (A. D. Wackerbarth, 1849; Benhamin Thorpe, 1865; Thomas Arnold, 1876; James M. Garnett, 1882; H. W. Lumsden, 1883; John Gibb, 1884; G. Cox, E. H. Jones, 1886; John Earl, 1892; Leslie Hall, 1892; William Morris and A. J. Wyatt, 1898).

50. Murray, Grammar, 207.

51. Sheridan, A Course of Lectures on Elocution Together with Two Dissertations on Language and A General Dictionary of the English Language . . . to which is prefixed A Rhetorical Grammar (London: J. Dodsley, Pall-Mall, C. Dilly, and J. Wilkie, 1780).

52. Coote, Elements of English Grammar, 278–83.

53. Woods, “The Cultural Tradition of Nineteenth-Century ‘Traditional’ Grammar Teaching,” 8.

54. On Murray, see Read, “The Motivation of Lindley Murray’s Grammatical Work.”

55. Murray, English Grammar, 146.

56. Ibid., 1839, 71.

57. Ibid., 1867, 224.

58. This wholesale lifting of Sheridan’s text only appears in the 4th edition of Murray’s English Grammar, in 1798, and is not in the first three editions (1795, 1796, 1797).

59. Ibid., 1798, 203.

60. This allegory of walking, predating the Wordsworthian walking composition, will be taken up in Coventry Patmore’s theory of isochronous intervals, though Patmore’s pace does not come from footsteps themselves but from the regular appearance of an accompanying fence-post—the mind, for Patmore, must perceive the metrical grid for the body to follow.

61. Murray, English Grammar Adapted to the Different Classes of Learners, 203. This text is identical in all editions following; it appears on p. 252 of the sixth American edition, English Grammar Comprehending the Principles and Rules of the Language (New York: Collins & Co., 1829), and the fifty-eighth edition, (London: Longman, Hurst, 1867), 203.

62. Sheridan, The Art of Reading, 27.

63. Murray, Grammar, 190.

64. Ibid., 203.

65. Murray and Flint, Abridged Grammar, 78.

66. Saintsbury gives only passing notice to Murray in his History of English Prosody, stopping to reprimand him for relying too much on accent and not enough on quantity, but admits that his doctrine that “we have all that the ancients had, and something they had not” is “uncommonly near the truth, though I dare say he did not know how true it was. For the fact of the matter is that we have the full quantitative scansion by feet, which is the franchise and privilege of classical verse, without the limitations of quantitative syllabisation with which that verse was hampered. We have their Order and our own Freedom besides” (156).

67. Guest, A History of English Rhythms, 111.

68. There is no record in the history of linguistics for the study of prosody, nor is there a survey like Fussell’s extremely useful Theory of Prosody in Eighteenth Century England. For useful histories of language study in nineteenth-century England, see Anna Morpurgo Davies, History of Linguistics and Aarsleff, The Study of Language in England 1780–1860.

69. Potter, The Muse in Chains.

70. Prins, “Victorian Meters,” 93.

71. Hollander, Vision and Resonance: Two Senses of Poetic Form, 19.

72. Prins, “Victorian Meters,” 90–91.

73. Goold Brown, The Grammar of English Grammars, 827, 828.

74. As evidence of the necessity for simplifying and abstracting metrical rules for pedagogical purposes, the section on “versification” that appears in Goold Brown’s often reprinted First Lines of Grammar reads: “Versification is the art of arranging words into lines of correspondent length, so as to produce harmony by the regular alternation of syllables differing in quantity” (Brown, The First Lines of Grammar, 145).

75. Patmore’s article, “English Metrical Critics,” appeared in issue XXVII, 127–61, 1857 of the North British Review in 1857 as “an article ostensibly reviewing George Vandenhoff ’s The Art of Elocution, Edwin Guest’s A History of English Rhythms, and William O’Brien’s The Ancient Rhythmical Art Recovered.” Sister Mary Augustine Roth’s reproduction of Patmore’s Essay on English Metrical Law includes an introduction in which she expertly traces the influences of Patmore’s predecessors Joshua Steele, Hegel (“whose Aesthetics provided the philosophical basis for an “organic” theory of prosody unifying ‘life’ and ‘law,’ meanings and versification,” ix), Daniel, Foster, Mitford, and Dallas. Patmore revised the essay and printed it as a “Prefatory Study on English Metrical Law” in the 1878 edition of Amelia, Tamerton Church Tower, Etc., which was again reprinted in the 1879 four-volume edition of Patmore’s collected Poems (in volume 2).

76. Patmore, “Essay on English Metrical Law,” Poems Volume 2, 217. I am using the fourth edition of the second volume of Poems, which was printed (and reprinted) in 1886, 1887, and 1890, attesting to its popularity as well as the potential readership of the essay, which appeared in the appendix. Despite the importance that Dennis Taylor has given to this essay (as the harbinger of the “New Prosody”), few of Patmore's obituaries mention the essay, and a long Atheneaum piece (1896: Dec. 5, 797) only states: “a thoughtful essay, marked by fresh study, and displaying the genius of the poet in a very distinct and startling light.” Saintsbury discards Patmore's metrical interventions in a June 15, 1878 Athenaeum review (757) [see chapter 3]. A long review in The Examiner ( June 29, 1878) summarizes:

it is ingenious and scrupulously exact in expression, and is conceived in a dignified spirit, but errs in recording as legitimate canons of rythmic (sic) art irregularities that are only to be pardoned in genius, not recommended to immaturity. For instance, it is dangerous to attempt, by any public recognition of time, to regulate the varied pauses that enliven and illuminate the best English verse. If once we drop the jog-trot measurement of lines by feet, on the ground that, what we call an iambus has, in fact, by an irregularity, become a trochee, we open the door to every sort of extravagance. By all means, let young people continue to be taught to scan in the old mechanical way. If they are poets, they will learn intuitively to arrange their time. . . . The whole of this study on metre, in short, is highly interesting, whether the reader agrees with it in detail or not. It is singular to find a poet defending with such dignity the theory of an art that he seems, in practice, so often to defy. (821–22)

Patmore himself asserts “I have seen with pleasure that, since then [1856], its main principles have been quietly adopted by most writers on the subject in periodicals and elsewhere” (“Essay on English Metrical Law,” 215).

77. Vandenhoff and Poe, A Plain System of Elocution; Vandenhoff, The Art of Elocution as an Essential Part of Rhetoric: with instructions in gesture and an appendix of oratorical, poetical, and dramatic extracts.

78. Milton’s Prosody was first published in 1887 as part of Henry Beeching’s school edition of Paradise Lost as “On the Elements of Blank Verse,” and it was reprinted in 1894 as a pamphlet all its own (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894), reprinted again in 1901 alongside Stone’s treatise, and printed in final revised form in 1921.

79. Stone had published On the Use of Classical Metres in English in 1899 and it was reprinted alongside Bridges’s Milton’s Prosody in 1901.

80. Schipper, Englische Metrik. Translated into English in 1910 as A History of English Versification, trans. Jakob Schipper, the book was reviewed alongside Saintsbury’s three volumes.

81. Omond, English Metrists and A Study of Metre were revised and reprinted. Omond was a frequent interlocutor with Mayor, Bridges, and Saintsbury.

82. I note the various editions of Patmore’s text to point to the way that scholars were constantly revising and reprinting their work on meter, adding appendixes, rejoinders, responses, and clarifications based on the proliferation of discourse on the matter. On the proliferation of writing about meter in the nineteenth century, see the next section of this chapter, then Taylor, Hardy’s Metres and Victorian Prosody and Prins, “Victorian Meters.” On the rise of mass literacy, see St. Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period and Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture in Britain 1750–1914 and The Rise of Mass Literacy: Reading and Writing in Modern Europe.

83. See Taylor and Prins, also, more recently, Hall, “Popular Prosody: Spectacle and the Politics of Victorian Versification,” or Pinch, “Love Thinking.”

84. Trench, On the Study of Words, 64.

Chapter 2: The Stigma of Meter

1. Thomas Sheridan’s third edition of A General Dictionary of the English Language revises “rhetorical grammar” to “prosodial grammar” and emphasizes that the grammar he wishes to provide therein refers only to oratory (lxxx).

2. Norman MacKenzie, “Introduction to the Fourth Edition,” The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, xiii.

3. Abbott, Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges (LI in-text citation), 231; Abbott, Further Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins (LII in-text citation); Abbott, The Correspondence of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Richard Watson Dixon (LIII in-text citation); House, The Journals and Papers of Gerard Manley Hopkins (JP in-text citation); Devlin, Sermons: The Sermons and Devotional Writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins; Hopkins, Author’s Note on “The Wreck of the Deutschland” (AN in-text citation).

4. Miles, “Gerard Hopkins,” 164.

5. “From the consequent miseries, the insensate and interminable slaughter, the hate and filth, we can turn to seek comfort only in the quiet confidence of our souls; and we look instinctively to the seers and poets of mankind, whose sayings are the oracles and prophecies of loveliness and lovingkindness.” From Bridges, “Preface,” The Spirit of Man. Hopkins’s poems in The Spirit of Man include “Spring and Fall” (9), reprinted from Miles, ed., Poets and Poetry of the Century, vol. viii; the first stanza of “The Wreck of the Deutschland” (53); “The Candle Indoors” (269); “In the Valley of the Elwy” (including Hopkins’s note about the poem, 358); “The Handsome Heart” (along with the note that “the author was a Jesuit priest, and Father in line 2 is the spiritual title,” 369); “The Habit of Perfection” (the first two stanzas; written when an undergraduate at Oxford, 385).

6. Most of Hopkins’s poems prior to The Spirit of Man appeared in small publications, and though the notice they attracted came mostly from his Catholic audience, early twentieth-century readers were intrigued by his innovations. George Saintsbury reported of Hopkins’s poems in 1910 that “it is quite clear they were all experiments,” and that the lines, “of the anti-foot and pro-stress division” seemed to have syllables “thrust in out of pure mischief ” (Saintsbury, A History of English Prosody from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day, 3:391).

7. Maynard, “The Artist as Hero,” 259–60.

8. Clutton-Brock, unsigned review, 19.

9. Richards, “Gerard Hopkins,” 195.

10. Hopkins also felt distress when faced with the physical form of the metrical mark.

11. Norman MacKenzie traces Hopkins’s addition of the accent marks on lines 9 and 14 on Bridges’s transcription from Manuscript A to Manuscript B. Variants in the manuscripts include “will” in italics from Manuscript A to “wíll.” MacKenzie notes that this is “probably GMH’s stress.” In Mackenzie’s Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, he keeps the marks on the rest of the poem but chooses to italicize will (Richards, Practical Criticism).

12. Richards, Practical Criticism, 83.

13. William Empson takes issue with Richards’s removal of the mark in Seven Types of Ambiguity, 148:

Mr. Richards, from whom I copy this, considers that the ambiguity of will is removed by the accent which Hopkins placed upon it; it seems to me rather that it is intensified. Certainly, with the accent on weep and and, will can only be an auxiliary verb, and with the accent on will its main meaning is “insist upon.” But the future meaning also can be imposed upon this latter way of reading the line if it is the tense which is being stressed, if it insists on the contrast between the two sorts of weeping, or, including know with weep, between the two sorts of knowledge. Now it is useful that the tense should be stressed at this crucial point, because it is these two contrasts and their unity which make the point of the poem.

Despite Empson’s acceptance of the ambiguity on “will,” he continues that “[i]t seems difficult to enjoy the accent on are, which the poet has inserted; I take it to mean: ‘Sorrow’s springs, always the same, independent of our attitude to them, exist,” permanently and as it were absolutely’” (149). In both instances, whether it is the two contrasts and their unity or the permanence of spring, Empson resolves Hopkins’s use of metrical marks into an absolute intention that tends toward a reading that erases the possibility that the meter could mean something other than an indication of stability.

14. In a discussion of “Easter Communion,” Griffiths writes, “two claims are made on the voice, claims which it can with difficulty meet simultaneously; it must hark back from ‘shakes’ to ‘brakes’ so that the rhyme may sound out and it must press on from ‘shakes’ to ‘them’ so that the syntax may flow” (The Printed Voice of Victorian Poetry, 273).

15. Cf. Richards, Basic English and Its Uses; So Much Nearer: Essays Towards a World English. A few canonical “sound” focused studies of Hopkins’s meter include J. Hillis Miller, “The Univocal Chiming,” 89–116; Susan Stewart, “Letter on Sound,” 29–52; James I. Wimsatt, Hopkins’s Poetics of Speech Sound: Sprung Rhythm, Lettering, Inscape.

16. Earle, The Philology of the English Tongue, 585–620.

17. Abbott, LII, 218–19.

18. Cf. Plotkin, The Tenth Muse; Dowling, Language and Decadence in the Victorian Fin de Siècle.

19. Plotkin, The Tenth Muse, 37–38.

20. Müller, Lectures on the Science of Language, 384.

21. Trench, On the Study of Words (1851) and English Past and Present (1855), 117. Further references are given parenthetically in the text.

22. House, JP, 269.

23. Ibid., 127; Higgins, The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Volume IV: Oxford Essays and Notes, 306–7.

24. For an intricate reading of Hopkins’s “Word” and “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” see Daniel Brown, Hopkins’ Idealism, 278–326.

25. Both White’s Hopkins: A Literary Biography and Phillips’s Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Victorian Visual World note the influence of Ruskin on Hopkins’s philosophy of inscape in the visual world. It is no accident that “blood is red” so closely resembles Ruskin’s meditation on perception in Modern Painters, especially the chapter, “Of the Pathetic Fallacy”: “be it observed that the word blue does not mean the sensation caused by a gentian on the human eye; but it means the power of producing that sensation” (157).

26. House, JP, 129; Higgins, Oxford Essays and Notes, 312.

27. Bloom, Gerard Manley Hopkins: Modern Critical Views, 3, 2.

28. House, JP, 139.

29. Hopkins had used a grave accent as early as 1864 in his draft of “Floris in Italy.” That mark occurs in a line that instructs us about how to use meter as a visual guide: “Beauty it may be is the meet of lines / Or careful-spacèd sequences of sound.” In the “mete” or measure of lines, sound—an imprecise science—must be sequenced and spaced onto the page. The grave mark, promoting the normally unpronounced “ed,” as is typical in poetic practice, spaces the line out to give it ten syllables.

30. Abbott, LI, 24.

31. Norman MacKenzie, Poetical Works, 56.

32. House, JP, 136. “Beating the bounds” of the Parish is an Ascension Day tradition. The priest would walk the grounds to show its boundary, saying a blessing at certain points. Boys with white birch rods would then rhythmically beat the spot until the priest moved on to the next boundary. Though parish maps have supplanted this tradition from some churchyards, Hopkins’s observation of this event gives another meaning to his use of “white birch” in his poems. “This ancient method of impressing the parish’s boundaries on the children’s memory on Ascension day is still preserved by three Oxford parishes: St. Michael’s at the North Gate, All Saints, and Saint Mary the Virgin’s. The bounds of St. Michael’s pass through the old St. Peter’s Rectory in New Inn Hall Street, where GMH then lodged” (n.1, 136, 348).

33. Norman MacKenzie, Poetical Works, ll. 3–5, 58.

34. Devlin, Sermons, 129.

35. House, JP, 195.

36. July 8, 1871: “I noticed two kinds of flash but I am not sure that sometimes there were not the two together from different points of the same cloud or starting from the same point different ways—one a straight stroke, broad like a stroke with chalk and liquid, as if the blade of an oar just stripped open a ribbon scar in smooth water and it caught the light; the other narrow and wire-like, like the splitting of a rock and danced down-along in a thousand jags” (House, JP, 212).

37. Hopkins, AN.

38. Abbott, LIII, 14–15.

39. Hopkins gladly erased the marks in order to try to assure the poem’s publication, but The Month rejected it even without marks.

40. Abbott, LI, 51–52.

41. See MacKenzie, The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, 319–20. An interesting phenomenological reading of “The Wreck” is offered by William A. Cohen in Embodied: Victorian Literature and the Senses, 125–27.

42. The numbers in the left column record the distance from the left edge of the page for each line. The distance is equivalent for each line, so that in line 1, the eye has to wander past 4 spaces (tabs, when we type) before the supposed two beats of the line. The right column records the number of stresses in the line according to the “Author’s Note.” I have reproduced this spacing—as all editors perhaps should—because the absence of words is part of the metrical pattern. The stanza itself leans to the right, like a stroke for stress when viewed from far away:

43. Arsis means the act a raising or lifting the foot and thesis to the stamping down of the foot, corresponding in Greek quantitative meter to the short and long part of the metrical foot. In Latin accentual verse, the meaning was reversed: arsis came to mean the long part of the foot and thesis the shorter. This misinterpretation held when English accentual verse translated short and long feet into unaccented and accented syllables. Hopkins explains this to Patmore in an 1883:

Perhaps you do not know that the Latin writers exchanged and misapplied the Greek words arsis and thesis. Arsis is properly the rise of the foot in dancing or of the conductor’s arm in beating time, thesis the fall of the same. Arsis therefore is the light part of the foot, I call it the ‘slack’; thesis is the heavy or strong, the stress. For this reason some writers now refuse to say arsis and thesis and use ictus only. It is clear the Latin writers thought of arsis as effort, thesis as the fall to rest after effort. (Abbott, LII, 185)

44. Saville, A Queer Chivalry, 83.

45. In Dublin in 1885, a series of three meditation points—titled “Lance and Nails,” “The Transfiguration,” and “The Five Wounds”—elaborates this early metaphor of the stigmata to attaching your will completely to God’s will: “Seeing Christ’s body nailed consider the attachment of his will to God’s will. Wish to be as bound to God’s will in all things, in the attachment of your mind and attention to prayer and the duty in hand; the attachment of your affections to Christ our Lord and his wounds instead of any earthly object” (Devlin, Sermons, 255).

46. Cf. MacKenzie, “Spelt from Sybil’s Leaves,” Poetical Works.

47. MacKenzie notices the pattern of 5s: 5x2 stanzas in part one and 5x5 stanzas in part two. He also refers to Hopkins’s early notebooks, “On the Origin of Beauty,” in which a character asks the professor: “Out of five dots arranged in a particular way you make a cross, may you not?” (House, JP, 103; Higgins, The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, 155).

48.. An earlier version of this line reads, “O rose but thy crimson, the gashes in thee / They came at thy nailing against the cross-tree” (ll. 33–24).

49.. “Rosa Mystica” was first published in The Irish Monthly, 26. 299 (May 1898): 234–35 and it was reprinted in Shipley’s Carmina Mariana.

50. Hopkins, considering Christ’s passion in early 1870, describes the wellspring of his emotion as a pressure like that of a knife:

But neither the weight nor the stress of sorrow, by themselves move us or bring the tears as a sharp knife does not cut for being pressed as long as it is pressed without any shaking of the hand but there is always one touch, something striking sideways and unlooked for, which in both cases undoes resistance and pierces, and this may be so delicate that the pathos seems to have gone directly to the body and cleared the understanding of its passage. On the other hand the pathetic touch by itself, as in dramatic pathos, will only draw slight tears if its matter is not important or not of import to us, the strong emotion coming from a force which was gathered before it was discharged: in this way a knife may pierce the flesh which it had happened only to graze and the grazing will go no deeper. (House, JP, 195)

51. Ibid., 11.

52. From Devlin, The Sermons: “the touch which only god can apply” (158).

53. Hartman, The Unmediated Vision, 49–67.

54. Miller, The Linguistic Moment, 260.

55. Hopkins’s journal entry from August 29, 1867 recounts a meeting with a Miss Warren (whose nephew was a Fellow at St. John’s Oxford); they took a walk (this episode is recounted in MacKenzie, Poetical Works, 149). Hopkins records:

Miss Warren told me that she had heard the following vision of an old woman. She saw, she said, white doves flying about her room and drops of blood falling from their “nibs” — that is their beaks. The story comes in Henderson’s book of Folklore. The woman was a good old woman. . . . The room was full of bright light, the “nibs” bathed in blood, and the drops fell on her. Then the light became dazzling and painful, the doves were gone, and our Lord appeared displaying His five wounds. (House, JP, 153–54)

The ability of the beak to “mark” as a pen nib would mark on a page would not have been lost on Hopkins, here. MacKenzie notes that Hopkins used the word “nibs” four days later in his description of the Dartmoor furze.

56. As Hopkins prepared to revise “The Wreck of the Deutschland” to send to Patmore in 1883, he found out that he had been appointed as a Fellow in Classics of the Royal University of Ireland (Abbott, LI, 263), a post that took him off English soil and away from the salvation of English souls altogether. This is, perhaps, another reason for his increasing interest in English soil, and the actual border of English and England. From his isolated vantage point in Dublin, his late poetry configures and reconfigures the multiple possibilities of connecting to God and to England.

57. Hopkins is writing about his rejection in The Month to his mother (LII, 138).

58. Abbott, LI, 46. Bridges famously despised “The Wreck of the Deutschland.” As he was preparing the first edition of Hopkins’s poems, in 1918, he wrote to Kate Hopkins: “That terrible ‘Deutschland’ looks and reads much better in type — you will be glad to hear. But I wish those nuns had stayed at home” (Stanford, Selected Letters of Robert Bridges, 726).

59. Abbott, LI, 46. By January 1879, Hopkins was explicit about his wish to convert Bridges. He writes: “You understand of course that I desire to see you a Catholic or, if not that, a Christian or, if not that, at least a believer in the true God (for you told me something of your views about the deity, which were not as they should be)” (60).

60. Hopkins’s family called him “the Crow of Maenefa” because of the similarity between black-gowned priests and crowish birds, and because of the crow’s nests, seats atop trees near St. Bueno’s College, where Hopkins studied in Wales (White, “Hopkins as the Crow of Maenefa,” 113–20).

61. Abbott, LIII, 27.

62. Patmore’s article “English Metrical Critics” appeared in issue 27, 127–61 of the North British Review as “an article ostensibly reviewing George Vandenhoff ’s The Art of Elocution, Edwin Guest’s A History of English Rhythms, and William O’Brien’s The Ancient Rhythmical Art Recovered.” Sister Mary Augustine Roth’s reproduction of Patmore’s Essay on English Metrical Law includes an introduction in which she expertly traces the influences of Patmore’s predecessors Joshua Steele, Hegel (“whose Aesthetics provided the philosophical basis for an ‘organic’ theory of prosody unifying ‘life’ and ‘law,’ meanings and versification,” ix), Daniel, Foster, Mitford, and Dallas. Patmore revised the essay and printed it as a “Prefatory Study on English Metrical Law” in the 1878 edition of Amelia, Tamerton Church Tower, Etc., and it was again reprinted in the 1879 four-volume edition of Patmore’s collected Poems. It is the correspondence between Hopkins and Patmore following this 1878 edition that is of interest to me here.

63. Abbott, LI, 119.

64. Though we cannot read the letter to which Hopkins is responding (Bridges destroyed his half of the correspondence), we can read that there was competition between Bridges and Patmore; Hopkins ends his discussion of Patmore’s theories in the January 1881 letter with “[b]ut about Patmore you are in the gall of bitterness.” Recall that, two years later, Bridges approached Patmore about the possibility of mentioning in print the “new prosody” that Bridges and Hopkins had devised (it was also Bridges who let slip that Hopkins was not only an astute reader of poems but a poet in his own right—and Hopkins’s employment of his own theories may have been cause for Patmore to misunderstand and resist Hopkins’s poems). Thus, amid the praise and niceties the two poets-critics exchanged, we sense a larger tension between Patmore, whose perceived expertise in matters of versification had only grown with the reissue of his treatise, and Hopkins, who speaks with an authority as assured as his poetic criticism. In the 1886 edition, the small “note” from the author states: “This Essay was first printed, almost as it now stands, in the year 1856. I have seen with pleasure that, since then, its main principles have been quietly adopted by most writers on the subject in periodicals and elsewhere.” It was precisely “in periodicals” where Bridges’s debates about classical meters were playing out concurrently, and where, as Patmore states in his essay, “a vast mass of nondescript matter has been brought up from the recesses visited, but no one has succeeded in rendering any sufficient amount of this secret of the intellectual deep,” concluding “upon few other subjects has so much been written with so little tangible result” (Coventry Patmore’s “Essay on English Metrical Law,” 3–4). Patmore never adopted any of Hopkins’s suggested revisions, though he assured Hopkins that he would give his suggestions “my best consideration . . . before I reprint that Essay, which I propose to do . . . meantime I will only say that much of the substance of your very valuable notes will come rather as a development than as a correction of the ideas which I have endeavoured—with too much levity perhaps—to express” (Abbott, LII, 186).

65. Ibid., 152–58, 177.

66. Ibid., 166–71. Abbott MS. 185a Durham University Library. This is also the case for Hopkins’s comments on The Unknown Eros Dec. 6, 1993, Abbott MS. 193a.

67. Ibid., 178–81, Abbott MS 190a 2–3.

68. Patmore, “Prefatory Study on English Metrical Law,” 15.

69. Abbott, LII, 179.

70. Hopkins continues: “Also what we emphasize we say clearer, more distinctly, and in fact to this is due the slurring, in English, of unaccented syllables; which is the beauty of the language, so that only misguided people say Dev-il, six-pence distinctly” (Abbott, LII, 179).

71. Ibid., 183.

72. Hopkins went over Bridges’s fair copy of his manuscript (MS B) over Christmas of 1883 as he was preparing to move to Dublin as a Fellow in Classics of the Royal University in Ireland (Abbott, LI, 263). Hopkins reached Dublin on February 18, 1884 and did not send his manuscript to Patmore until early March.

73. Though the “Author’s Note” shows a confidence about the poet trusting the reader’s performance, guided by the always subjective ear, Hopkins’s correspondence with Bridges proves that Hopkins had not resolved the issue of using marks for accent in his own poems, and continued, in fact, to trust the eye over the ear. Because Bridges made fair copies of all of Hopkins’s poems, Bridges could choose whether to leave the accent marks on or off. In this way, Hopkins could see his poems in a different handwriting with the original metrical marks erased and then, “make a few corrections,” which often meant reluctantly returning his accent marks to his poems.

74. Devlin, Sermons, 127.

75. Rask, Grammar, 114.

76. Of course this, too, was at issue: Anglo-Saxonism created the myth of that national border. Anglo-Saxon has just as often been claimed as the ancestral heritage of Denmark.

77. Abbot, LI, 87.

78. William Quinn, “Hopkins’s Anglo-Saxon,” 25–32.

79. The history of philology reveals a great deal about the disappearance of the “mark” for accent on English writing. When Old English texts were translated into modern English, the modernized editions “changed the accentuation” of the Old English texts or deleted the accent marks altogether. Edwin Guest, in his 1838 History of English Rhythms, writes “they change the accents, which in certain cases are used to distinguish the long vowels; they compound and resolve words; and they alter the stops and pauses — or in other words the punctuation and versification — at their pleasure” (9). Guest brings up OE accent again on page 16: “there can be little doubt that modern accentuation in our language is mainly built on that of its earliest dialect; and that we must investigate the latter before we can arrive at any satisfactory arrangement of the former.” And again, on page 277: “of all meters known to our poetry, that which has best succeed in reconciling the poet’s freedom with the demands of science, is the alliterative system of our Anglo-Saxon ancestors.” In a review of an Anglo-Saxon dictionary, Henry Sweet proclaimed: “A serious fault of these two editors is that they both deliberately suppress the accents of the MSS in their texts” (Sweet, Transactions, 119).

80. A typical (and relatively easy) line from a poem by Barnes: “An ‘zoo they toddled hwome to rest, / Lik’ doves a-vlee-en to their nest, / in leafy boughs a-swäyen” (Barnes, Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, 51.

81. Abbott, LI, 162.

82. Abbott, LII, 222.

83. Barnes, An Outline of English Speech-Craft, iii.

84. Abbott, LI, 163.

85. Ibid., 246.

86. Ibid., 231.

Chapter 3: The Institution of Meter

1. Perkins, History of Modern Poetry, 41.

2. “A Poet of Content,” rev. of Shorter Poems by Robert Bridges (454–55).

3. Green, “Robert Bridges: Studies in His Work and Thought to 1904,” 93.

4. Bridges published this poem multiple times, as XXIV Sonnets, Ed. Bumpus, 1876; LXXIX Sonnets, Daniel Press, 1889; LXIX Sonnets, Smith, Elder & Co. Vol 1., 1898, and in The Poetical Works of Robert Bridges, 187.

5. Norman MacKenzie, commentary, The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, 470–71. MacKenzie notes that Hopkins suggests revisions to l. 3, “’Tis the joy the foldings of her dress to view” in Abbott, LI 35, 89, 141, and 243. Hopkins took such issue with the line that he omitted it from his translation.

6. Abbott, LI, April 3, 1877, 35. He goes on to say that Bridges has not reached “finality in point of execution, words may be chosen with more point and propriety, images might be more brilliant etc.”

7. Symonds, “The Blank Verse of Milton,” 767–81, reprinted in Blank Verse, 73– 113; Symonds, appendix, Sketches and Studies of Italy, 411–28; and Symonds, appendix, Sketches and Studies of the Southern Europe, 325–84.

8. Stanford, Selected Letters of Robert Bridges, vol. 1, 127.

9. Ibid., 128.

10. The preface was included with the poem before Hopkins sent the poem to Coventry Patmore in 1884. Norman MacKenzie, Complete Poems and Manuscripts, 314.

11. Ibid., 118

12. Abbott, LIII, 14.

13. The sonnet became, initially, the twenty-third sonnet in his 1889 version of The Growth of Love and the twenty-second sonnet in all other editions. Cf. Holmes, “The Growth of The Growth of Love,” 583–97; 55, 221.

14. Stanford, In The Classic Mode, 86. He lists “A Passer-by,” “The Downs,” and “Early Autumn Sonnet — So hot the noon” as the three additional poems in accentual meter.

15. See MacKenzie, Poetical Works, 376–77, for a detailed discussion of the manuscripts, and 144–46 for a copy of the earliest surviving autograph copy of the poem.

16. For a summary of readings of “The Windhover,” by far the most discussed of Hopkins’s poems, see ibid., 378.

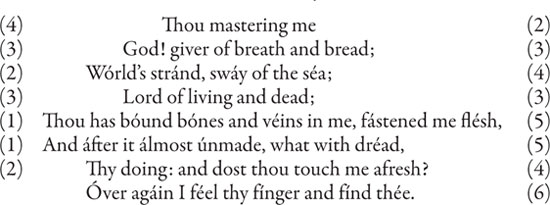

17. “Mastery” has a sforzando sign above it, indicating slightly stronger stress and greater emphasis (ibid., 144).

18. Abbott, LI, 85.

19. Cf. Harrison, “The Birds of Gerard Manley Hopkins,” 448–63; also, August, “The Growth of ‘The Windhover,’” 465–68.

20. Abbott, LI, 71.

21. September 28, 1883, in Derek Patmore, “Three Poets Discuss New Verse Forms: The Correspondence of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Robert Bridges, and Coventry Patmore,” 69–78.

22. Bridges, Milton, Paradise Lost, Book I, 5. Henry Beeching was one of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s first editors (posthumous), including some of his poems in his turn of the century anthology Lyra Sacra. He also married Robert Bridges’s niece.

23. Symonds, “The Blank Verse of Milton,” 767–81, mentioned by Hopkins to Bridges in letter XXX, April 3, 1877 (Abbott, LI, 32–40).

24. Symonds, Sketches and Studies in Southern Europe, 361–62.

25. Ibid., 352. Blank Verse, which became a more famous volume, was published in 1895 and included the essays first published in the former book.

26. The rules he presented in 1887 included the rule of open vowels (all open vowels may be elided); the second rule of pure R (unstressed vowels separated by “r” may be elided). This rule has an interesting exception in Milton’s use of the word spirit: “Milton uses the word spirit (and thus its derivatives) to fill indifferently one or two places of the ten in his verse). . . . The word is an exception” (22); the third rule of pure L (unstressed vowels before pure L may be elided, and here the exception is on the word “evil”) and finally the fourth rule of the elision of unstressed vowels before N.

27. Bridges, On the Prosody of Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes.

28. Unsigned review, “Mr. Bridges and Metre,” review of Milton’s Prosody, by Robert Bridges, 85. The review begins, “Mr. Robert Bridges’ essay on Milton’s prosody has long been recognized by metrical students as a work of standing value.”

29. His appendices to the 1901 version included: Appendix A, The Extrametrical Syllable; Appendix B, On Elision; Appendix C, Adjectives in able; Appendix D, On Recession of Accent; Appendix E, Pronunciation in Milton; Appendix F, On Metrical Equivalence; Appendix G, On the Use of Greek Terminology in English Prosody; Appendix H, Specimens of Ten-Syllable Verse; (Appendix I is somewhat cleverly elided so we go straight to) Appendix J, Rules of Stress-Rhythms, which includes a second part on Accentual Hexameter.

30. Bridges, Robert Seymour and William Johnson Stone, Milton’s Prosody, 1901,

31. Bridges, Milton’s Prosody, 1921, 94.

32. Stanford, In the Classic Mode, 90.

33. Bridges, Milton’s Prosody, 1921, 113.

34. From the introduction to the Society for the Purification of English, which was founded in 1913 but suspended its proceedings due to the “national distraction” and resumed them again in 1918:

Literary education in England would seem in one grave respect to lack efficiency, for it does not inspire writers with a due sense of responsibility towards their native speech. . . . The ideal of [this] proposed association is both conservative and democratic. It would aim at preserving all the richness of differentiation in our vocabulary, its nice grammatical usages, its traditional idioms, and the music of its inherited pronunciation: it would oppose whatever is slipshod or careless, and all blurring of hard-won distinctions, but it would no less oppose the tyranny of schoolmasters and grammarians, both in their pedantic conservatism, and in their ignorant enforcing of newfangled ‘rules,’ based not on principle, but merely on what has come to be considered ‘correct’ usage. The ideal of the Society is that our language and its future development should be controlled by the forces and processes which have formed it in the past; that it should keep its English character, and that the new elements added to it should be in harmony with the old; for by this means our growing knowledge would be more widely spread, and the whole nation brought into closer touch with the national medium of expression. (SPE Tracts, [London: Clarendon Press, October 1919]), italics mine.

35. Bridges had his own reservations about Skeat’s crusades; in a 1909 letter to Henry Bradley, Bridges writes: “I think Skeat is an ass” and “Skeat is worthless.”

36. Mayor, Chapters on English Metre, 98.

37. (Emphasis mine). This letter and its response are both unpublished. Dep. Bridges 36, folios 16–31, Modern Papers. Bodleian Library, Oxford. Bridges’s letter is dated November 26, 1915 and Mayor’s reply is dated November 19, 1915. Bridges’s letter begins “Dear Sir,” and Mayor’s begins “My Dear Sir,” showing that their relationship was strictly professional and perhaps antagonistic.

38. Ibid., November 29, 1915 response (unpublished):

My Dear Sir, My reason for writing my book on “Modern English Meter” was to see how far the rules laid down by metrists, such as Dr. Guest and, in a lesser degree, by Dr. Abbott, are borne out by facts. For Ch. II and again, in Ch. X, variations from rules are to be found in our best poets from the time of Shakespeare onward, and are felt by the lovers of poetry to enhance its beauty. I have ventured to clarify these under the heads as Feminine Rhythm, Enjambment, Position of Pauses, Interchange of Feet, Special Quality of Vowels and Consonants, Alliteration, Onomatopoea, etc., Believe me. Yours very truly, J. B. Mayor.

39. A 1902 review of both Chapters on English Metre by Joseph Mayor and Milton’s Prosody by Robert Bridges was titled “The Battle of the Scansionists.” “Simple as the matter might seem,” the reviewer summarizes, “the eternal crux of a metrical systemist is to find some scheme by which he can label words as being in such and such a metre” (465).

40. Bridges, Milton’s Prosody, 1921, 114.

41. Saintsbury, Last Vintage, 116; Last Scrap Book, 88–91. Both quoted in Dorothy Richardson Jones, King of Critics: George Saintsbury, 8.

42. Saintsbury, History of Prosody from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day, 3, 575.

43. Patmore published “English Metrical Critics” in the North British Review in 1857, expanding it and revising it as part of his volume of poems, Amelia, & Tamerton Church Tower in 1878.

44. Saintsbury, Atheneaum 2642 ( June 1878), 757. The last line refers to translating Horace’s Odes into English.

45. Saintsbury, A History of Elizabethan Literature, 14. He continues, emphatically, “[e]very English metre since Chaucer at least can be scanned, within the proper limits, according to the strictest rules of classical prosody: and while all good English metre comes out scatheless from the application of those rules nothing exhibits the badness of bad English metre so well as that application.” Saintsbury’s A History of Elizabethan Literature was part of a four-part series that proved extremely popular in the 1890s, with twenty-two reprints in all, and two editions.

46. Guest, A History of English Rhythms, 108.

47. An archeologist and philologist, Guest established the Philological Society in 1842 that eventually began working on the New English Dictionary. An anonymous reviewer notes that “compilers of histories of English language and literature have quarried in Dr. Guest and appropriated his results,” and that Guest refused to reprint the edition in his lifetime (323).

48. Despite Skeat’s efforts, Guest’s A History of English Rhythms was not that influential; it served more as a foil than anything else. The revival in the study of Anglo-Saxon literature, as a whole, was more directly responsible for a revived interest in Anglo-Saxon meter, as well as the influence of philological and metrical accounts of the evolution of English poetry and meter from Germany. A small note in Notes and Queries vol. 101 ( January 20, 1900) responds to “Egeria”’s query regarding “Instruction on the Rules of Poetry”: “There is, as far as we know, no such work as you seek. Dr. Guest on ‘English Rhythm’ is erudite, but scarcely popular,” 60.

49. Saintsbury, A Short History of English Literature, 44.

50. Ibid., 39–47.

51. Loring, The Rhymer’s Lexicon, iv.

52. Ibid., viii.

53. Eric Eaglesham writes that the authors of the Act—Robert Laurie Morant, James Wycliffe Headlam, and John William Mackail (classicists all)—believed that true mental discipline could only be learned through mastery of Latin grammar; English education had grown too quickly and without standards and, after the failures of the Boer War, Latin could help the country get back on track. Eric Eaglesham, “Implementing the Education Act of 1902,” 153–75. Christopher Stray makes a similar assertion: “Underlying the attachment to Latin grammar was a powerful emotional conviction that it was the exemplar of ‘real’ knowledge. . . . The stress on the power of discipline needs to be seen in this context, as a reassertion of permanence and stability” (Stray, Classics Transformed, 258).

54. Cf. Matthew Hendley, “‘Help us to Secure a Strong, Healthy, Prosperous and Peaceful Britain,’” 261–88. See also J. O. Springhall, “Lord Meath, Youth, and Empire,” 97–111, and R.J.Q. Adams, “The National Service League and Mandatory Service in Edwardian Britain,” 53–74.

55. “Of the later generations of phoneticians I know little. Among them towers the Poet Laureate, to whom perhaps Higgins may owe his Miltonic sympathies, though here again I must disclaim all portraiture.” George Bernard Shaw, “Preface: A Professor of Phonetics,” 102.

56. Andrews, The Reading and Writing of Verse, ix.

57. Loring, The Rhymer’s Lexicon, x.

58. Saintsbury, A History of English Prosody, vol. 1, 182.

59. Ibid., vol. 3, 188. Cf. Prins, “Victorian Meters,” The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry, 89–113.

60. Saintsbury, A History of English Prosody, vol. 3, 247.

61. Ibid., vol. 1, 529.

62. Ibid., vol. 3, 522. See Jason Rudy’s excellent discussion of Carlyle’s rhythms in Electric Meters: Victorian Physiological Poetics, 76–77.

63. Saintsbury, A History of English Prosody, vol. 3, 521.

64. Omond, A Study of Metre, xii.

65. Saintsbury, A History of English Prosody, vol. 3.

66. “And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity” (1 Cor 13:13). I am grateful to Liam Corley and Carolyn Williams for this reference.

67. Christopher Stray notes how, well into the twentieth century, “when ciphers were being used in wartime, the classical knowledge which excluded the lower ranks from such communications on one side simultaneously linked the officers and gentlemen on opposing sides” (Stray, Classics Transformed, 127).

68. George Saintsbury studied at Merton College until 1868; Bridges was at Corpus Christi; and Hopkins was at Balliol until 1867.

69. From “Verses Written for Mrs. Daniel,” an unpublished poem written in 1919 publicly printed in facsimile at Oxford in 1932 and printed again in Collected Poems. Notice Bridges’s subtle play on the word “rootlets,” wherein “roots” is the root of the word. Botanical metaphors for metrical and grammatical education abounded in this period, with many calls to rely on proper educational “roots” so that the language student could “blossom” into the right kind of English citizen, quite unlike the earlier insidious grass of metrical form in the metrical histories I discussed in chapter 1.

70. Green, Robert Bridges, 37.

71. Phillips describes Bridges’s education:

Once the basics of Latin and Greek were sufficiently grasped, the boys moved gradually through Horace, Ovid, Livy, Cicero, Catullus, Propertius, Caesar, Greek lyric and elegiac writers, Virgil, Homer, some Thucydides, Herodotus, Demosthenes, Pindar, Plato’s Republic, and aselection of Greek tragedies and comedies. The examinations which Robert took in at Eton in 1863 show clearly the emphasis on parsing, on translation, on being able to write in Greek and Latin.

Phillips also notes how in 1859 Eton became the first of the schools to be caught up in the Rifle Volunteer Movement, which soon spread to the universities and throughout the country. She writes, “by the summer of 1860 nearly half of the upper school boys at Eton (some 300) were enrolled in the Corps, among them Robert and his friend Lionel Muirhead” (Phillips, Robert Bridges: A Biography, 16, 22).

72. Palmer, in The Rise of English Studies, describes the evolving association with the Greek language as “purely literary” rather than “practical” or, as in the case of Latin and English, a method of studying “words as things.” The “thinginess” of Latin and English grammar, and of words as signs (of meaning) in general, is certainly tied to the growing need to define grammar and philology as “scientific” as opposed to literary, a trend which caused divisions in English language departments between the literary and philological camps (Palmer, The Rise of English Studies, 13).

73. James Brinsley Richards, Seven Years at Eton, 17.

74. Harold Monro’s stated aim with the publication he edited in 1912, The Poetry Review, was to make the review “the representative organ chiefly of the younger generation of poets” (10). Monro’s Poetry and Drama was seen as the successor to The Poetry Review after he had a falling out with the society (The Poetry Society) that backed the original review.

75. Bridges, “Flycatchers,” l. 7–8.

76. Bridges scrawled “Free rhythm” next to this poem in the holograph copy of his book manuscript.

77. Bridges, Milton’s Prosody, 1901, v.

78. Bridges, Correspondence of Robert Bridges and Henry Bradley, 59.

Chapter 4: The Discipline of Meter

1. This is a later moment in the history John Guillory describes in his chapter, “Mute Inglorious Miltons,” 85–133: “Coleridge understood very well that the life of this dialect was sustained by the schools, just as it was originally produced by the institutional lag between Latin and vernacular literacy.” This “vernacular poetics” is, in some way, what I am attempting to argue for, here, but with an abstracted concept of “meter” that really means regular rhythm and has little to do with “meter” at all.

2. Cf. Eagleton, “The Rise of English,” 15–46; Graff, Professing Literature: An Institutional History.

3. Baldick, The Social Mission of English Studies 1848–1932, 63.

4. John Churton Collins, The Study of English Literature, 148.

5. On education and English studies, see Eagleton, “The Rise of English,” 15–46; Palmer, The Rise of English Studies; Court, Institutionalizing English Literature; Mathieson, The Preachers of Culture; Soffer, Discipline and Power: The University, History, & the Making of an English Elite, 1870–1930; Shayer, The Teaching of English in Schools. On education in England, see Neuberg, Popular Education in Eighteenth Century England, 93–138; Lawson and Silver, A Social History of Education in England. On the classical ideal of education, see McPherson, Theory of Higher Education in Nineteenth-Century England; Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture; Heathorn, For Home, Country, and Race; John M. Mackenzie, “Imperialism and the School Textbook.” On Matthew Arnold and educational theory, see Wallcott The Origins of Culture and Anarchy: Matthew Arnold and Popular Education in England; J. Dover Wilson, introduction, Culture and Anarchy; Connell, The Educational Thought and Influence of Matthew Arnold.

6. Jakob Schipper published a similar account of English rhythm in 1882, Englische Metrik but it was not translated into English until 1910 as A History of English Versification, where, rather than comparison with Skeat’s 1882 reprint of Guest (which it resembled) it was compared with George Saintsbury’s three volume History of English Prosody, which derided any theory based solely on accent. The tension between “Teutonic” or “Saxon” theories of accent-based English rhythm and Anglo-Norman or hybrid theories markedly increased in the years leading up to the First World War.

7. Cf. Briggs, “Saxons, Normans, and Victorians,” 215–35, and Parker, England’s Darling: The Victorian Cult of Alfred the Great. What Hugh A. MacDougall calls the “racial myth” of origins in English literature (Racial Myth in English History: Trojans, Teutons, and Anglo-Saxons) is traced by Clare Simmons to the educational discourse of both Thomas Arnold and John Petherton. Arnold asserted that despite repeated invasions, English history began “with the coming over of the Saxons. We this great English nation, whose race and language are now overrunning the earth from one end of it to the other, — we were born when the white horse of the Saxons had established his dominion from the Tweed to the Tamar. . . . So far our national identity extends, so far history is modern, for it treats of a life which was then, and is not yet extinguished” (Arnold, Modern History, 30; Simmons, 72); and in an overview of Anglo-Saxon studies published in 1840, John Petheram expressed a hope that “the Anglo-Saxon tongue will, within a few years, form an essential part of a liberal education” (Petheram, Anglo-Saxon Literature, 180; in Simmons, 71). Even Charles Dickens, in his popular A Child’s History of England, evokes the “law, and industry, and safety for life and property, and all great results of steady perseverance” of “the Saxon Blood” (III, Tanchevitz, 1853, 148–49); quoted in Philip Collins, Dickens and Education, 60. Both Thomas Arnold and James Kay-Shuttleworth believed that the lower classes were more likely to understand Saxon vocabulary. Arnold wrote that the distinction between rich and poor was marked in the use of French and Saxon words: “the language of the rich, which is of course that of books also, being so full of French words derived from their Norman ancestors, while that of the poor still retains the pure Saxon character inherited from their Saxon forefathers” (“The Social Condition of the Operative Classes,” [1832], Miscellaneous Works of Thomas Arnold, 407), quoted in Simmons, 71; Kay-Shuttleworth wrote “those who have had close intercourse with the labouring classes well know with what difficulty thy comprehend words not of a Saxon origin, and how frequently addresses to them are unintelligible from the continual use of terms of a Latin or Greek derivation; yet the daily language of the middle and upper classes abounds with such words” (115). Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth on Popular Education; from “First Report on the Training School at Battersea,” 1841.

8. Heathorn, For Home, Country, and Race, 402.

9. Cf. Patmore, “English Metrical Critics,” chapter 3, part 5.

10. Pound, Pisan Cantos (written in military detention).

11. Report of the Commission on the State of Popular Education, 1861, Vol. 1, 120.

12. Baldick, The Social Mission of English Studies 1848–1932, 43.

13. Matthew Arnold, Reports on Elementary Schools General Report 1852–1882, 130.

14. For instance, comparing the 1876 Classified Catalogue of School, College, Classical, Technical, and General Educational Works (Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington) with the 1887 Catalogue is already a daunting task. As stated in the preface to the 1876 edition, the 1871 catalogue was “simply a classified list of eight or nine thousand Educational books now in use in this country, issued by nearly one hundred and fifty publishers.” But by 1876, the number of titles presented to the reader is nearer 15,000. Of these, the 1876 edition contained over 600 titles listed on classical subjects, including individual authors in the original or translation (i.e., Aeschylus, Plato), 212 titles under the heading Greek, and 255 under Latin (including testament studies) for a total of roughly 1,070 classical entries. For English subjects in 1876, authors are listed together under “English ‘classics’” and total only 113, with nearly 1,000 titles listed under English in total (Anglo-Saxon 15; Elocution 36; Grammar and Composition 315; Literature 84; Poetry 54; Primers 89; Pronunciation 7; Readers 190; Spelling and Dictation 93; Rhyming Dictionary 2). Compare these numbers with the 1887 edition, which gives “nearer twenty-five thousand” titles, where there are over 2,445 entries for classical languages (600 in Latin and 345 in Greek) and over 1,700 entries for English (Anglo-Saxon 17; Elocution 48; Grammar, Composition and Dictation [formerly with spelling] 565—a huge increase; Literature 67; Parsing [new category] 21; Poetry 100 [nearly double the number from 1876]; Primers 123; Pronunciation 8; Readers 233; Spelling 109; English “Classics” 300 [more than double the number from 1876], and an additional single author category, Shakespeare 110).

15. Michael, The Teaching of English from the Sixteenth Century to 1870; Görlach, An Annotated Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century Grammars of English. As I discussed in chapter 1, there is much work to be done in evaluating how often these books were used, and by what classes.

16. Arnold, 120.

17. The Chambers’s series was reprinted in 1870, 1871, 1873, 1880, and 1887, supplementing this selection, in 1879 and 1894, with a series of National Reading Books. Chambers also published a Poetical Reader in 1865.

18. The poem is titled “My Land.” In an 1855 Irish Quarterly Review article by “N.J.G.,” titled “A Quartette of Irish Poets,” that reviewed The Poems of Thomas Davis, Now First Collected. With Notes and Historical Illustrations (Dublin: James Duffy, 1853), the cultivating powers of poetry are directed particularly toward Irish writers:

If, by proper training or natural inclination, Irishmen would direct their intellectual powers to the cultivation of literature . . . it is not difficult to conceive how much brilliant success must attend their efforts. . . . There is nothing that would tend more surely to improve the national mind than a general cultivation of poetry: the more we would see our old traditions enlarged and decked out in poetic dress, the more, naturally, we should value them, and the more strongly attached we should be to the localities which gave them birth. . . . It is needless to say what a beneficial effect this movement would have on the national character: a morally independent feeling would of necessity be inculcated, and everything which we are taught to consider as arising from virtuous principles and elevated views, all the blessings of freedom, in a word, would spring up and bless our people (698–99).

Davis’s poem circulated in many Irish, British, and American anthologies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: from Davis, The Spirit of The Nation, Ballads and Songs by the Writers of “the Nation,” 219; Kennedy, The Universal Irish Song Book, 163; Cooke, The Dublin Book of Irish Verse 1728–1909, 251; Welsh, Golden Treasury of Irish Songs and Lyrics; American Ideals: Selected Patriotic Readings for Seventh and Eighth Grades and Junior High Schools, etc.

19. N.J.G., “A Quartette of Irish Writers,” 697–731.

20. Trilling, Matthew Arnold, 212. Trilling is referring to Arnold’s lectures, On the Study of Celtic Literature. In both Celtic Literature and On Translating Homer, Arnold thinks through various possible origins for English poetry in order to project into the future a stable national culture. Gross, who calls Arnold a snob, explains that “Arnold was deeply committed to the values of his own class, that of the university-educated gentleman — a social stratum lying somewhere between the Barbarians and the Philistines” (Gross, The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters, 59; Arnold, On the Study of Celtic Literature and On Translating Homer).

21. Ward, The English Poets, 1.

22. Arnold, Reports on Elementary Schools, 186.

23. Cf. Robson, “Standing on the Burning Deck: Poetry, Performance, History,” 148–62.

24. Cf. Rudy, Electric Meters: Victorian Physiological Poetics; and Blair, Victorian Poetry and the Culture of the Heart.

25. Arnold, Reports, 1880, 200–01.

26. Antony Harrison, “Victorian Culture Wars: Alexander Smith, Arthur Hugh Clough, and Matthew Arnold in 1853,” argues that Arnold’s concerns about “good poetry” are a “hugely important manifestation of class warfare” and that “everything Arnold has been constructed to cherish by his upper-class breeding and education” would have been threatened by poetry that did not adhere to Arnold’s sense of “culture” (516).

27. Cf. Mangan, Athleticism in the Victorian and Edwardian Public School.

28. Cf. Heathorn, For Home, Country, and Race; Horn, The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild; Norman Mackenzie, Imperialism and Popular Culture; for an Edwardian era text from America on the disciplinary benefits of military drill, see Robert Tait Mackenzie, Exercise in Education and Medicine.

29. Lootens, “Victorian Poetry and Patriotism,” 255–79.

30. Roberts, A Nation in Arms, 86–88..

31. “Kipling’s Tribute to Lord Roberts: reproaches England for Refusing to hear His ‘Pleading in the Marketplace,’” The New York Times, November 19, 1914.

32. Horn (The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild) describes how

the establishment of “Empire Day” owed much to the efforts of the Earl of Meath, who was determined that the nation’s youth should be imbued with feelings of devotion to King and Empire. To this end in 1903, he founded the Empire Day Movement, and by the following year had persuaded a number of local education authorities to adopt 24 May, the anniversary of Queen Victoria’s birth — as a day of celebration in their schools. . . . By 1907, over 12,500 elementary schools in England and Wales (well over 1/2 the total) were participating and the movement continued to expand thereafter (144).

33. Lootens, “Victorian Poetry and Patriotism.” Lootens relies on Parry’s 1992 The Poetry of Rudyard Kipling and Papajewski’s 1983 “The Variety of Kipling,” as her sources. Parry notes that “Recessional” was also performed by some 10,000 British soldiers in a Boer War victory ceremony outside the Parliament of the Transvall.

34. Horn, The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild, 45.

35. Though some reviewers did recognize Kipling’s versification (“No measure is too intricate for him to master,” said one anonymous reviewer in Blackwoods) most did not. But Kipling was aware of the national legacy of his versification. In a 1911 letter to Brander Matthews, who had just sent him his new book, Kipling engages with the prosodist on the subject of his rhymes: “Ever so much thanks for your ‘Study of Versification.’ It’s useful to me in my job — like the rest of your books. . . . There isn’t to my knowledge another set of workman’s books like yours. By the way have you got Hood’s ‘How I taught a youngster to write verse?’ It was written serially ages ago for a boy’s magazine in England and I remember reading it again and again . . . this yere poeting is a strange and baffling business. All the same I’m glad I wasn’t born an Alexandrine Frenchman” (Kipling The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, 33–34).

36. Le Gallienne, Rudyard Kipling: A Criticism, 64.

37. “Kipling: Richard Le Gallienne’s Volume Devoted to a Severe Criticism of Him.”

38. Horn points out that military drill was first introduced in school curriculum as early as 1871, but that after the Boer War the Model Course of Physical Training, based largely on army training methods, was issued by the Board of Education in 1902 with the aim of “promoting discipline among the pupils” (Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild, 56).

39. John Le Vay, “Kipling’s Recessional,” 153–54.

40. Barnett, Teaching and Organisation, 145.

41. In 1899, Edmond Holmes wrote that the main goals of National Education were “preparing children for the battle of life (a battle which will . . . be fought in all parts of the British Empire). Report of the Board of Education for 1899–1900 vol. ix,

42. Newbolt, My World as in My Time, 8.

43. Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory; Eby, The Road to Armageddon.

44. Pericles Lewis, Cambridge Introduction to Modernism; Margot Norris, Writing War in the Twentieth Century.

45. Michael Cohen, “Whittier, Ballad Reading, and the Culture of Nineteenth-Century Poetry”; Marsland, The Nation’s Cause: French, English, and German Poetry of the First World War.

46. Elkin Mathews review of Admirals All by Henry Newbolt, 324.

47. The Scotsman, Poetry section, 3.

48. Cf. Eby, Road to Armageddon; Marsland, The Nation’s Cause; Van Wyk Smith, Drummer Hodge: The Poetry of the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902).

49. Most notably in “Tommy”: “it’s ‘Thin red line of ‘eroes when the drums begin to roll”; “Route Marchin,” in Kipling, Barrack-Room Ballads and Other Verses.

50. R.K.R. Thornton, Poetry of the 1890s, 6.

51. Vanessa Furse Jackson, The Poetry of Henry Newbolt: Patriotism Is Not Enough, 66.

52. In Newbolt’s My World as in My Time he elaborates:

The Kaiser Wilhelm had made a threatening move, and it was announced that as proof of our readiness to meet a serious challenge, a Special Service Squadron would be sent to sea at once. I had in my drawer some verses which I had written with the title Drake’s Drum more than a month before — early December, 1895. I posted them to the Editor, Sidney Low, as possibly appropriate to the present moment. . . . The sense of fatefulness was redoubled the next day, when we read that the Flying Squadron had gone to sea with the Revenge [also the name of Drake’s ship] for flagship and Captain Drake as commander for her marines. (186)

53. See Eby, The Road to Armageddon, 90–106; Jackson, The Poetry of Henry Newbolt, 65–114.

54. See Mangan, Athleticism in the Victorian and Edwardian Public School, 183, 179–206.

55. Alfred Noyes published parts 1–3 of his twelve volume, “Drake: An English Epic” in 1906, and 4–12 in 1908 (see Tucker, Epic: Britain’s Heroic Muse 1750–1910, 560–70). A poem of the same title published in 1918 by Norah Holland rhymes the drum’s beat to “the chime of tramping feet,” evoking not only Drake but Blake and Raleigh, to leave “the ports of Heaven” and join England in its national emergency (Holland, Spun Yarn and Spindrift, 88).

56. “Drake’s Drum Heard in the German Surrender of 1918.” Excerpt from The Outlook, April 26, 1919: