5

5

A thousand suppliants stand around thy throne,

Stricken with love for thee, O Poesy.

I stand among them, and with them I groan,

And stretch my arms for help. Oh, pity me!

—Wilfred Owen, “To Poesy” (1909)

Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War

and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.

—Wilfred Owen, unpublished “Preface” (probably May 1918)

The above epigraphs, written nine years apart, demonstrate a transition between Edwardian and Georgian poetics. Wilfred Owen, son of a stationmaster and early “supplicant” to poetry, did not attend any of England’s great public schools. He is, rather, a success story of the military metrical complex of England’s state-funded school’s national curriculum. In Owen’s 1906 copy of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury, he scribbled a circle around the word “Paeon” in dark ink, writing out the definition in an adolescent scrawl: “A song in honor of Appollo [sic] — a song of triumph.” English poetry had triumphed over the classics as representative of the nation’s greatness for Owen and many other poets of his generation. Classical meters were English meters and English poetry was the highest form of the country’s literature—a triumph, mostly, of Edwardian education.

The story of the “Georgian Revolt” runs parallel to the story of the rise of experimental Modernism in poetry. Robert Ross asserts that Georgian poetry was part of the “larger twentieth-century revolt against Humanism; … the poetic phase of a widespread revolt against Academism among all the arts; and, specifically in the field of poetry, a reaction against the dead hand of the Romantic-Victorian tradition.”1 Critics who work on the coteries of the period (the poets publishing in Edward Marsh’s wildly popular Georgian Poetry series, the Imagists, the Futurists, and the Vorticists) tend to use “meter” as a stand-in for convention and tradition in verse. But as we have seen, both mass and elite cultures were invested in a concept of English meter that stood for an idealized “Englishness.” Pitting “Romantic-Victorian tradition” against “free verse” skims over the ways that the Edwardian era specifically contributed to both of those discourses. Owen, Robert Graves, and Siegfried Sassoon are poets and soldiers whose work benefits from reevaluation in the dynamic context of metrical culture in England before and during the First World War. In the first section of this chapter, I discuss how Owen and Graves were “supplicants” to the Edwardian concept of English poetry in the early stages of the war. Their transition to being “less concerned with poetry” has everything to do with the way that English meter shaped how these soldiers approached their service and how their ideas were changed by the pressures of modern warfare. More specifically, their ideas about the communities of English meter were both affirmed and complicated by the chaos of battle and neurasthenic trauma. In this chapter, I read the trauma of soldiers’ experiences as a synecdoche for the dissolution of broader concepts about English national culture during and after the First World War. The disciplining and ordering intention that English meter accrues before the war becomes at once horrifying and comforting during and after the war. The trauma of meter, for both soldier-poets and early twentieth-century readers, was the realization that meter as a stable category was illusory. To recover from trauma, through a method of therapy provided by the very idea of “meter” that had betrayed them, was to acknowledge the collective agreement—sometimes manifest as an individual desperate need—to believe in meter’s stability anyway.2

The phenomenon of wartime neuroses during the First World War forced psychologists to fashion theories that grasped the centrality of practice to psychic healing. In instances of neurasthenic trauma, often psychologists were charged with the task of realigning linguistic ruptures, manifested by expressive stammers or even complete aphasia. Owen was hospitalized for shell shock and Graves was also prevented from returning to the front because of his mental state. In the second section of this chapter, I juxtapose the interdisciplinary techniques employed by Owen’s doctor, Captain Arthur J. Brock, a classicist and sociologist on staff at Craiglockhart War Hospital, with the methods of Dr. W.H.R. Rivers, an anthropologist fascinated by the theories of Freud. For Brock’s patients, ordered activities provided a lifeline to the unique social world of the hospital and surrounding town, forming a method of healing through which shell-shocked officers were efficiently “cured” so that they could return to the front. The success of these “ordered activities” was particularly remarkable for linguistic disorders. Rhythmically controlled time became an empowering practice for patients adept at composing metrical verses; composing in meter, for many patients trained in poetic craft, was a new kind of therapeutic activity that coupled the expressive aspects of Freudian psychotherapy practiced by Dr. Rivers (narrating traumatic experiences in order to “move through” them) with sociological ergo-therapy, or, “cure by functioning” promoted by Captain Brock. Brock’s method also promoted a different kind of metrical culture—which we could call “metrical” insofar as temporal and spatial ordering become more important than narrative and/or expressive models.

Ordering time and prosodic ordering at Craiglockhart illustrate, in microcosm, many wartime and postwar anxieties about poetic form. Soldiers at the hospital were reeducated to embrace forms and orders that had become meaningless to them while at the same time they were encouraged to express their mistrust of all forms and orders. That is, while soldiers participated in ordered activities designed to help them reintegrate into the social world, they were also encouraged to express their emotions and feelings freely through Freudian talk-therapy. Sassoon and Owen, who were patients of Dr. Rivers and Captain Brock, respectively, both composed poems at the hospital that deserve rethinking within these new psychotherapeutic models of poetic production: specifically, through the continuous supplementary aspect of Freudian narration, on the one hand, and the active metrical exercise of fitting fragments of experience into a predetermined order, on the other. This metrical writing under the auspices of rehabilitation promised to reintroduce the writer to the social world through the history of form.

As I have discussed in the preceding chapters, poetic meter was increasingly seen as a symbol of English national culture in this period. However, until recently, poetic meter has seldom been considered a historically significant connection to the social world. Indeed, meter is rarely discussed in detail in the many classic texts about First World War poetry. Paul Fussell, author of the two monumental texts Poetic Meter and Poetic Form (1965) and The Great War and Modern Memory (1975), was close to connecting soldier-poetry to English national meter, but read tropes and myth making in soldier-poetry as preconditions of the ironic modern age. In a discussion of Cowper’s “The Castaway” in relation to Edmund Blunden’s “Rural Economy,” Fussell acknowledges “an English reader would find it hard to experience that stanza form without recalling at least bits of Cowper’s poem.”3 What Fussell means is “an English reader” who had read a good deal of Cowper and knew his particular poetic form. Fussell is mainly interested in intertextual images, symbols, and pastoral allusions, but he acknowledges that Blunden may be aware of the “artistic shape in which he has lodged” his “concern,” tracing the “semblance” between himself, Cowper, and the men who appear in his poem. It is surprising that Fussell uses the verb “lodged” for Blunden’s choice of form, as if Blunden had Cowper’s poetic form in mind and either moved his sentiment inside the intact meter or stuck it there by force. The semblance at which Fussell hints, however, is precisely the substance of intertextual meter; it ties Blunden to his distinctively English past, and writes him into the history of “immortalizing” the dead who may or may not be redeemed. Cowper’s “Castaway” would have been a useful reference for Fussell: “tears by bards or heroes shed / Alike immortalize the dead” (219). Fussell’s dismissal of Cowper’s meter misses the way that Blunden’s meter references the social world and comments on how the soldier’s relationship to those communities beyond the war (the prewar schoolroom, hearth, and home) will be irrevocably altered. “What husbandry could outdo this? / With flesh and blood he fed / The planted iron that nought amiss / Grew thick and swift and red, / And in a night though ne’er so cold / Those acres bristled a hundredfold” (205). An expansion of hymn meter, the final two lines of the sestet stanza are a repeated third rhyme (ababcc); Blunden’s poem subverts the pastoral into a harvested graveyard, and Cowper’s heroic poem becomes a plot, too, out of which Blunden can dredge poetic tradition in order to make it morbidly his own.

Fussell, Samuel Hynes, and Jay Winter have shown how the “literariness” of the First World War promoted the use of typical romantic images in soldier poetry, with each critic careful to point out the privileged class education available to the officer-poets who produced the now famous poetic images of the Great War. In the classic The Great War and Modern Memory, Fussell argues that pastoral tropes and intertextual references to the great works of English literature “signal a constant reaching out towards traditional significance … an attempt to make some sense of the war in relation to inherited tradition” (57). He cites specific symbols to make his point: “Intact and generative are the traditional values associated with traditional symbols—white blossoms, stars, the moon, the nightingale, the heroes of the Iliad, pastoral flowers” (61). Indeed, Fussell’s influential assertion that soldiers were not “merely literate” but were “vigorously literary” (157), is reinforced by Samuel Hynes’s A War Imagined. Hynes writes that, “it was clear by the end of 1914 that this war would be different—it would be the most literary and the most poetical war in English history.”4 Fussell and Hynes agree that English literature gave soldiers a sense of pride, purpose, and value; the heroic themes of their literary traditions provided a justification for their activities. Jay Winter, in Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning, is dismissive of any poetic function of war poetry save the tropological: “[s]ome poems were experimental; others were written in conventional forms. Much of it arose out of the perceived need not to reject out of hand traditional languages about the dead, but rather to reformulate and reinvigorate older tropes about loss of life in wartime.”5 Both Winter and Fussell briefly acknowledge the consolatory function of hymns, but their main points relate to remembered Biblical imagery that the hymns conjure, evoking familiarity and comfort. These scholars show us how English and classical literary education influenced officers and provided comfort for them; I hope to build on their work and complicate it by showing how actively soldier-poets recognized their relationship to poetry and poetic form as equivocal, volatile, and distressing.

Though critical discourses about First World War poetry showed how popular anthologies like Palgrave’s Golden Treasury and the Oxford Anthology of English Poetry provided comfort for soldiers on the front, they neglected to discuss how soldier-poets had been trained, prewar, in the particularities of English poetic craft. Soldier-poets were conditioned by the martial meters of patriotic verses in schoolbooks and the public press before and during the war to see themselves as part of a collective English culture, bound to defend the language of Shakespeare. Heroic patriotism had been portrayed through a particular kind of English metrical poetry that was often directly allied to military service. Military and metrical drill, as I explored in the previous chapter, relied on similar ideologies of discipline and protecting the “mother country.” Though these poetic practices provided comfort for soldiers on the front, there is also evidence that many soldier-poets were already questioning the rhetoric of formal Englishness that prewar poetry promoted. In No More Parades (1925), Ford Madox Ford presents a fictionalized account of how English poetic forms were used to counter the effects of mental crises. The protagonist, Tietjens, attempts to write his way out of a nervous breakdown by speedily composing a sonnet: “He said to himself that by God he must take himself in hand. He grabbed with his heavy hands at a piece of buff paper and wrote on it in a column of fat, wet letters:

a

b

b

a

a

b

b

a, and so on.”6

Tietjens writes the sonnet in “two minutes and eleven seconds” on “buff” paper with “fat,” “wet” letters, the upright letters taking on the traits of a healthy body. Immediately after, the broken-down bodies of soldiers enter the room, returning from battle: “[t]heir feet shuffled desultorily; they … held in unliterary hands small open books that they dropped from time to time.” Tietjens’s empowered “literary” hands act of their own volition, writing the sonnet as he barks orders simultaneously to men around him, careful “never to think on the subject of a shock at the moment of a shock.”7 Captain Tietjens’s hands, in their practiced exercise of writing in English meter, order his mind so that he can continue to give orders to the men around him—“unliterary” men whose own “feet” shuffle aimlessly. Predicated by the national curriculum and by the resulting inundation of popular war poems in the public press, military feet and metrical feet are joined here—not to inspire a patriotic collective, but rather to allow for the automatic composition of a line meant to discipline and protect an individual officer and then his company.

Ford’s fictional account renders all the more illuminating the fact that in addition to poetry anthologies, Wilfred Owen owned the 1908 reprint of R. F. Brewer’s popular manual, Orthometry, or, The Art of Versification and the Technicalities of Poetry.8 This handbook encourages poets to understand metrical laws so as to “at least accustom the beginner to the proper use of his feet before trusting him to untried wings,” and praises how English poetic forms have become successfully imprinted in the minds of all Englishmen. Brewer’s manual declared that

[t]he study of our poets has now happily attained a footing in the curriculum of nearly all our public schools and colleges; while the millions who attend our elementary schools have suitable poetic passages indelibly impressed upon their memory in youth. All but pessimists anticipate good results of this early training upon the tastes and re-creative pleasures of young England of the twentieth century. (ix–x)

Ford, Owen, Graves, and Sassoon were all products of an education system that “impressed upon their memory in youth” memorable passages from English poetry. In a wartime context, memorized poetic forms took on new meaning. It is not only the “re-creative” pleasure of writing poetry (read both as “recreation” and that which can be created again and again), but also the importance of training that emerges when these prosodic discourses are considered in light of actual military operations. The idea of using writing as a form of mental ordering relied on the assumption that education had done its work before the war; traditional poetic forms had to have been successfully inscribed into an officer’s memory for them to be used as aids in his rehabilitation. Even to the nonofficer class, marching songs and other forms of patriotic narratives had been passed down by the school system wherein military drill and metrical drill had been established as counterparts in the late nineteenth century.9 How did the war refashion the disciplinary and therapeutic aspects of metrical writing?

In 1913, Owen wrote to his mother that he was leaving the Vicarage at Dunsden, escaping the “hotbed of religion” and murdering his “false creed,” that is, leaving the Church of England. He imagines how poetry will now become his religion:

It has just struck me that one of the occult Powers that Be may have overheard the ancient desire of my heart to be like the immortals, the immortals of earthly Fame, I mean, and is now on a fair way to granting it…. Only where in me is the mighty power of Verse that covered the multitude of their sins…. I still find great comfort in scribbling; but lately I am deadening to all poetic impulses, save those due to the pressure of Problems pushing me to seek relief in unstopping my mouth.10

The ability to express himself freely in poetry gives Owen “relief” despite a lack of “poetic impulse.” Though this is hardly a depiction of metrical order, Owen admits that the expressive aspect of writing is a comfort to him. In the same letter, he includes an early draft of the poem, “On My Songs” (inspired by James Russell Lowell’s sonnet, “To the Spirit of Keats”),11 which shows his assumption of and equivocation over the poetic legacy he hopes to continue:

Though unseen poets, many and many a time,

Have answered me as if they knew my woe,

And it might seem have fashioned so their rime

To be my own soul’s cry; easing the flow

Of my dumb tears with language sweet as sobs, 5

Yet are there days when all these hoards of thought

Hold nothing for me. Not one verse that throbs

Throbs with my heart, or as my brain is fraught.

‘Tis then I voice mine own weird reveries:

Low croonings of a motherless child, in gloom 10

Singing his frightened self to sleep, are these.

One night, if thou shouldst live in this Sick Room,

Dreading the Dark thou darest not illume,

Listen; my voice may haply lend thee ease.12

When the poetry of other “unknown” or “distant” poets ceases to comfort Owen, he turns to writing his own verses. Here, Owen imagines writing verses as a way of healing himself and then, potentially, lending a healing verse to others. Verses metrically “throbbing” that do not “throb” with his heart are artificial, external, and are not guaranteed to provide comfort. The line: “Yet are there days when all these hoards of thought / Hold nothing for me. Not one verse that throbs / Throbs with my heart, or as my brain is fraught” shows that the perceived physiological comfort of a meter “throbbing” in time with a heart cannot “hold” a thought that will soothe the poet’s fraught “brain.” Though “throbs” / “throbs” does seem to evoke a steady beat, its placement at the end of line 7 and the beginning of line 8 creates a palpitation, as it were, set up by the caesura of “me. Not” in the middle of line 7. That is, the phenomenological aspects of meter, so willingly believed by many generations of poets so as to become part of the tradition, fail Owen when he needs it most, when he himself is ill. It is not physical, but mental comfort that he requires from this tradition, which he recognizes is something of a fantasy of youth, akin to a “low crooning,” a meaningless comfort. His poem is made of “weird reveries” and the metrical “throb” of his own composition might translate his “sob” into a “song” that he will call “his,” and the poem, though it hopes to “lend ease” to a future reader, enacts its own potential inability to comfort an audience.13 Though Owen subtly considers the difference between reading and writing poetry here, he finds diversion, at least, in composing a poem in a traditional metrical form. After writing a roundel about Hercules in 1914, he explains to his cousin Leslie Gunston that “I find it exceedingly easy to write one without having either emotion or ideas.”14 We can trace how Owen clearly values poetry as a means of uncensored expression at the same time as he finds it delightful that he can compose easily in a fixed form—a dual awareness that predates his enlistment.

Two months after the declaration of war, Owen was in France working his way toward rationalizing a reason to enlist. Though he wouldn’t join the Artists’ Rifles until November 1915, he was indecisive about his “duty” to defend England and its language versus his “duty” toward writing poetry. On November 6, 1914 he wrote to his mother: “Now I may be led into enlisting when I get home: so familiarize yourself with the idea! It is a sad sign if I do: for it means that I shall consider the continuation of my life of no use to England. And if once my fears are roused for the perpetuity and supremacy of my mother-tongue, in the world — I would not hesitate, as I hesitate now — to enlist” (295).

Owen considers his sacrifice particularly great in the context of language and poetry, since it is possible that the “continuation” of his life might lead to important poetic contributions to the mother tongue. The idea of a “mother” country and “mother tongue” surfaces in a letter to his own mother—who was far away when he was living in France and working as a tutor in Bordeaux— and carries multiple ties to the communities of home: national, literary, and familial. Nearly a month later, he honed his argument, seeing himself as Keats’s direct disciple, one in a long line of important poets:

The Daily Mail speaks very movingly about the ‘duties shirked’ by English young men. I suffer a good deal of shame. But while those ten thousand lusty louts go on playing football I shall go on playing with my little axiom: — that my life is worth more than my death to Englishmen.

Do you know what would hold me together on a battlefield? The sense that I was perpetuating the language in which Keats and the rest of them wrote! I do not know in what else England is greatly superior, or dearer to me, than another land and people. (300)

Owen’s idea of what could “hold him together” in combat is shaped by his relation to the community of “English poets,” of which he sees himself a part.15 By 1915, he was reading Servitude et Grandeur Militaires by Alfred de Vigny and quoting this line to his mother: “If any man despairs of becoming a Poet, let him carry his pack and march in the ranks.” He continued, “I don’t despair of becoming a Poet…. Will you set about finding the address of the ‘Artists’ Rifles’ as this is the Corps which offers commissions to ‘gentlemen returning from abroad’ ”(342). Artists’ Rifles interested Owen because Lord Leighton (1830–96, president of the Royal Academy 1878–96), Millais (1829–96, Pre-Raphaelite cofounder), and Forbes Robertson (1853–1937, actor and theater manager), were all members, as he exclaimed to his mother in a letter two weeks later. Once Owen enlisted and had begun his military training, however, he complained to his brother Harold that his poetic training was woefully inept in the face of his new duties: “What does Keats have to teach me of rifle and machine-gun drill, how will my pass in Botany teach me to lunge a bayonet, how will Shelley show me how to hate or any poet teach me the trajectory of the bullet?”16 Owen may not have realized, at this stage, how much poetry would help to keep him together on the battlefield, in the Casualty Clearing Station, and at the War Hospital.

Apparently free of such hesitations, Robert Graves enlisted almost immediately after the outbreak of war. His first book of poems, Over the Brazier, however, “also contains poems in which he imagines his work’s reception and questions his relationship to the poetry he was taught to value. The book is divided into three parts. The first part, “Charterhouse,” is the name of Graves’s public school, where he encountered poetry for the first time; in his memoir, he records: “I found a book that had the ballads of ‘Chevy Chase’ and ‘Sir Andrew Barton’ in it; these were the first two real poems I remember reading. I saw how good they were.”17 The poems in “Charterhouse” show an admiration for “anthems, stately, thunderous” (“Ghost Music”) but also show Graves’s playful and irreverent attitude toward the constraints of English meter. His long poem titled “Free Verse” (reprinted as the final poem in his 1917 Fairies and Fusiliers), begins:

I now delight

In spite

Of the might

And the right

Of classic tradition 5

In writing

And reciting

Straight ahead

Without let or omission

Just any little rhyme 10

In any little time

That runs in my head:

Because, I’ve said,

My rhymes no longer stand arrayed

Like Prussian soldiers on parade 15

That march,

Stiff as starch,

Foot to foot,

Boot to boot,

Blade to blade, 20

Button to button,

Cheeks and chops and chins like mutton.18

Graves’s poem is regulated by “any little rhyme” without any regular time, performing its own delusion with traditional verse forms,19 and seeing what happens when he puts them into “uniform.” The lines, “My rhymes no longer stand arrayed / Like Prussian soldiers on parade” are the most metrically regular lines of the poem, and directly link metrical form to military form. “Foot to foot” becomes “boot to boot,” and then, dangerously, “blade to blade.” Military discipline is preceded by the disciplines of “classical tradition.” Graves accuses poets, who attempt to artificially arrange their poems into “meaningless conceits,” of being “petty.” The action of “disciplining” language into poetic form is allegorized as violent, and the verbs Graves uses to describe the desecration of language allude to both violence during wartime and that of English ideas of propriety:

How petty

To take

A merry little rhyme

In a jolly little time 35

And poke it

And choke it

Change it, arrange it

Straight-lace it, deface it,

Pleat it with pleats, 40

Sheet it with sheets,

Of empty meaningless conceits,

And chop and chew

And hack and hew

And weld it into a uniform stanza, 45

And evolve a neat

Complacent, complete,

Academic extravaganza!20

The “rhymes,” like Saintsbury’s armies of soldierly feet, are welded “into a uniform stanza,” “button to button,” “neat” and “complacent,” “complete.” And yet Graves, himself a captain, participates in this “academic extravaganza” in his loosely formed “free verse,” which is, with its odd “straight-laced” rhyme, anything but “free.” Like Owen’s lament that the “throb” of metrical beats does not align with his heartbeat, Graves makes the act of aligning metrical feet menacingly corporeal. The verses are chopped, chewed, hacked, and hewed like mutton. The “might and right” of classical and military tradition are made ironic; Owen’s later allusion to Horace’s “sweet and meet,” becomes, for Graves, “sweet” and “meat”: the coming butchery of the soldierly bodies can be read as powerfully foreshadowed by the complacency with which soldierly feet are hacked into Graves’s Skeltonic lines.

Despite the chilling collision of military and metrical form in “Free Verse,” (later titled, provocatively, “In Spite,” in 1927), the second section of Over the Brazier titled “La Bassée” (referring to the Battle of La Bassée in the fall of 1914) considers the familiar themes of military and poetic glory. “The Shadow of Death” laments (like Owen’s prewar letter) that dying young for Graves would also mean the end of his poetic gift. “Here’s an end to my art! / I must die and I know it, / With battle murder at my heart — / Sad death for a poet! // Oh my songs never sung, / And my plays to darkness blown! / I am still so young, so young, / And my life was my own.” Graves’s unwritten poems are mourned like dead soldiers or his dead children: “song, / I may father no longer” (19). In the sonnet, “The Morning Before Battle,” Graves contrasts how he “carelessly sang, pinned roses on my breast” in the octave, to the stark final three lines of the sestet that anticipate the now famous image from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land: “the pale rose / Smelt sickly, till it seemed through a swift tear-flood / That dead men blossomed in the garden close” (21). Though war and poetry seem incommensurate in these two poems, Graves comments on how the war inspires less macabre transformations. “A Renascence” describes the “white flabbiness” of arms turning into “brown and lean … brass bars,” men who have “steeled a tender, girlish heart, / Tempered it with a man’s pride, / Learning to play the butcher’s part / Though the woman screams inside” (13). The inherent chauvinism of these lines is amplified by the fact that metrical poetry must be made into a manly art. The men are taught to “leap the parapet” and “stab the stark bayonet” but the rebirth is not their transformation from effeminate bystanders into hardened heroes, rather it is the transformation of this military world—and the misery it brings with it—into poetry. Graves performs the transformation of brute action into the potentially more redemptive act of writing poems, thus enacting the rebirth of the title: “of their travailings and groans / Poetry is born again.”21

Graves refused to reprint many of these early war poems in later volumes, though he continued to elaborate on the problems of military and musical form in his memoir Goodbye to All That (1929). “La Bassée” is where Graves questions the innocence of marching songs and demonstrates how these take on a maddening repetition and murderous connotations:

“[t]hat night we marched back again…. The men were singing. Being mostly from the Midlands, they sang comic songs … : Slippery Sam, When we’ve Wound up the Watch on the Rhine, and I do like a S’nice S’mince Pie, to a concertina accompaniment. The tune of S’nice S’mince Pie ran in my head all next day, and for the week following I couldn’t get rid of it.”22

In the ten pages after his first introduction of this song, Graves describes in vivid detail a brutal disaster of communication, resulting in thousands of casualties: “the barbed-wire entanglements protecting [the old front line] had not been removed, so that the Highlanders got caught and machine-gunned between their own assault and support lines” (129); “We went up to the corpsestrewn front line” (132); “I was surprised at some of the attitudes in which the dead stiffened—bandaging friends’ wounds, crawling, cutting wire” (134). The survivors eat meat pie and deaden their nerves with whiskey before they line up to wait for the next stage of attack, and the menacing song about meat pie returns:

We waited on the fire-step from four to nine o’clock, with fixed bayonets, for the order to go over. My mind was a blank, except for the recurrence of S’nice S’mince S’pie, S’nice S’mince S’pie … I don’t like ham, lamb or jam, and I don’t like roley-poley …

The men laughed at my singing. The acting C.S.M. said: “It’s murder, sir.”

“Of course it’s murder, you bloody fool,” I agreed, “But there’s nothing else for it, is there?” It was still raining. But when I sees a s’nice s’mince s’pie, I asks for a helping twice… (137)

Amid descriptions of corpses souring on the front—“I vomited more than once while superintending the carrying…. The colour of the dead faces changed from white to yellow-grey, to red, to purple, to green, to black, to slimy” (137)—the song manically repeating in the officer’s head takes on the connotation of murder, the soldiers’ decomposing bodies in direct contrast to the whiskey and meat pie that the survivors eat. The joking expression, “it’s murder, sir,” expresses what they have just carried out, and are about to repeat. The expression also proves that the song, on endless repetition in their minds, is agitating rather than calming or ordering. Graves’s character dismisses the complaint by continuing to sing, and as such, anticipates that this song and this war will continue by the refrain, “I ask for a helping twice.” The irony of this passage is that the officer has assimilated the view of the troops; even the simplest forms of comfort have lost meaning here and have come to symbolize the brutal and empty goals of battle. The endless repetition, both of the tune’s recurrence in his mind and his performance of it, signifies form’s inability to console or even distract the soldier from his circumstances. Repetition appears again in the wake of inconsolability through the popular First World War marching song, “We’re Here Because We’re Here.” The song is an example of the foot-beat rhythm growing almost maddeningly repetitive, to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”—a song about past joyous times that ironically refers to those times being brought back into the present again and again, as well as the tune to which popular histories of England were sung (as I discussed in chapter 1). Here, “let auld acquaintance be forgot,” becomes a more apt subtext for the song’s proliferation of nonmovement. There is no mention of “there,” the home where old acquaintances await, and sung on the march, the song erases each new place the soldier lays his feet; he is at once ‘here’ and ‘here’ and ‘here,’ a veritable nowhere. The song: “We’re here / Because / We’re here / Because / We’re here / Because we’re here” enacts the trap of progression within no progression as well as the feeling of being “nowhere” at all on the larger scale of the theater of war. The war is “here” and “everywhere,” just as the soldier’s tune demands no beginning or past, and no end or future.23

Though both Owen and Graves considered their poetry to be a patriotic contribution to the national language, Graves’s early poem comments on meter and militaristic discipline and violence, and his prose about war comments on the way sing-song verse meant to comfort can quickly turn sinister. Owen’s letters foreshadow his breakdown when he imagines that an idea of Keats could “hold him together” on the battlefield and his subtle awareness in the poem “On my Songs” that the “throb” of poetry, at times, “holds nothing” for him is evidence of a latent disillusionment that would become manifest in the Craiglockhart War Hospital. There is much in both Owen’s letters and poems and Graves’s poems and memoir about the intermingling of military forms and musical and metrical forms. On a typewritten copy of Graves’s poem “Free Verse,” Owen copied out another poem from Over the Brazier: “Sorley’s Weather”:

When outside the icy rain

Comes leaping helter-skelter,

Shall I tie my restive brain

Snugly under shelter?

Shall I make a gentle song,

Here in my firelit study? 5

When outside the winds blow strong

And the lanes are muddy?

With old wine and drowsy meats

Am I to fill my belly? 10

Shall I glutton here with Keats?

Shall I drink with Shelley?

Tobacco’s pleasant, firelight’s good

Poetry makes both better.

Clay is wet and so is mud, 15

Winter rains are wetter.

Yet rest there Shelley, on the sill,

For though the winds come frorely,

I’m away to the rain-blown hill

And the ghost of Sorley.24

Both poems were ostensibly from Graves’s manuscript pages; war poet Charles Sorley was killed in action in October 1915 and his collection Marlborough and Other Poems was published posthumously in 1916. Here, Owen and Graves agree that Shelley and Keats are not useful in the current storm, but Owen is still thinking about how poetry might make things better. In a poem Owen wrote at Craiglockhart, called “The Poet in Pain,” he criticizes those who would write of the horrors of war without experiencing it: “Some men sing songs of Pain and scarcely guess / Their import, for they never knew her stress.”25 It is his task, still imagining the representation of the nation’s greatness in its poetry, “to write of health with shaking hands, bone-pale, / Of pleasure, having hell in every vein” (ll. 11–12). We could read “to write of health with shaking hands” as “to write to health”—no longer the health of the larger nation, but the health of the smaller community of officers who found themselves cut off from the poetic and national ideals that led them to enlist in the first place. Like Tietjens imagining the healthy bodies of his fat, wet letters, the responsibility to preserve and protect English poetry, and the figure of the English poet, shifted so that the writing of English poetry became part of the process of healing the psyches of wounded soldier poets.

W.H.R. Rivers was among the many medical officers interested in new treatments for neurasthenia or, as Rivers preferred to call it, anxiety and substitution neurosis. Anxiety neurosis interested Rivers because it required that the patient attempt to “lift” the repression in his mind through a process of confronting, narrating, and therefore “metabolizing” the memory that, by his methods, had been “thrust out of [the patient’s] consciousness.”26 This ability to renarrate an event in order to recontextualize it was the unique ability of officers; Rivers expressed boredom with the men of the ranks he had treated at Maghull War Hospital, recording that “the characteristic of the uneducated person is that the mental outlook of adult life does not differ appreciably from that of childhood.”27 Rivers believed that officers possessed a higher faculty for expression in general due to their education, but also understood that their upbringing formed part of a culture of repression in British society that required men to “move on” from difficult memories without confronting or expressing them, especially officers who were expected to repress fear in order to lead a regiment confidently into battle. This culture of repression, for Rivers, was the root cause of many nervous disorders—repression that had “germinated in the nursery and [been] perfected in the English public school.”28 Though Rivers criticizes this tendency in English society, it is this very ability to express traumatic memories in well-crafted English narratives that attracted him to the highly educated officer-patients at Craiglockhart.

Before transferring to Craiglockhart, Rivers worked closely with Dr. William Brown at Maghull, where both doctors developed their therapeutic methods. Brown’s idea, autognosis, largely adapted from Freud, was based on the new belief that anxiety neuroses were based in pathogenic associations between past and recent events and the resulting confusions over meaning. In “W.H. R. Rivers and the War Neuroses,” Allan Young explains that the job of therapy was to expose these links and clarify these misunderstandings (369). Brown emphasized “long talks between the physician and the patient.” The physician’s task, among others, was to help the patient sort out any temporal dislocation between past and current events through redirecting the patient’s attention toward “a neglected aspect of his experience,”29 in an attempt to transform traumatic memories into tolerable, and even pleasant, images. Rivers gives the example of a patient who witnessed the violent death of his friend; a shell had blown apart the man’s body. The doctor points out that quick death of his patient’s friend, though gruesome, was painless, and that this friend is now free from harm, thus allowing the patient to “dwell upon his painful memories” by casting them in a new (albeit grimly positive) light. Dr. Rivers’s patient, Sassoon, published four poems in the hospital literary magazine The Hydra in 1917.30 “Repression of War Experience” (the title of a 1917 lecture and 1918 Lancet article by Rivers) was not among the poems Sassoon published at Craiglockhart, perhaps to protect Dr. Rivers from thinking his nerves were out of order. The poem illustrates what Sassoon thought of Rivers’s methods and of the process of therapy in general:

it’s bad to think of war,

when thoughts you’ve gagged all day come back to scare you;

and it’s been proved that soldiers don’t go mad

Unless they lose control of ugly thoughts

That drive them out to jabber among the trees. 5

Now light your pipe; look, what a steady hand.

Draw a deep breath; stop thinking, count fifteen,

And you’re as right as rain …31

This ironic narration shows the harm caused by repression, despite the belief that “it’s bad to think of war.” The poem ends with the subject running mad among the trees.

Sassoon describes the order of daytime treatment and “wholesome activities” at the hospital as “elaborately cheerful. Brisk amusements were encouraged, entertainments were got up, and serious cases were seldom seen downstairs” (23), but he later contrasts these organized amusements with the chaotic and uncontrollable aspects of the war neuroses. Day and night are contrasted as interludes controlled by either the medical staff or by the anxiety neuroses, but never by the patient’s own repaired will.

[B]y night [the doctors] lost control and the hospital became sepulchral and oppressive with saturations of war experience…. One became conscious that the place was full of men whose slumbers were morbid and terrifying — men muttering uneasily or suddenly crying out in their sleep…. In the day-time, sitting in a sunny room, a man could discuss his psycho-neurotic symptoms with his doctor, who could diagnose phobias and conflicts and formulate them in scientific terminology. Significant dreams could be noted down, and Rivers could try to remove repressions. (87–88)

“Muttering” or “suddenly crying out” is calmly transcribed into “scientific terminology” that the doctor “notes down,” diagnosing and renarrating the symptoms into a cheerful reinscription of the experience in the patient’s mind. In Sassoon’s description, daytime is unsettling and unsatisfying, as if we could already anticipate the contrast with incommunicable and sudden terror, shouted to the reluctant audience of other sleepless soldiers in the inevitable night. The descent into chaotic memories is described in bracing detail as that which is truly present in the patient’s mind—a place to which the doctor, despite his nodding encouragement, will never have complete access. “[B]y night each man was back in his doomed sector of a horror-stricken front line where the panic and stampede of some ghastly experience was re-enacted among the livid faces of the dead. No doctor could save him then…. Not then was their evil hour, but now; now, in the sweating suffocation of nightmare, in paralysis of limbs, in the stammering of dislocated speech” (87).

Here, Sassoon narrates what will be familiar to us as the definition of trauma: that the moment when the memory occurred is less powerful than its haunting and endless return, mocking the deliberate military march of any disciplined order and seizing the patient’s mind with an unordered “stampede” of nightmare. Sassoon’s dramatization of the doctor’s attempts to “remove repressions” feels ironically inefficient when compared to the patient’s disorienting collapse of past into present and the resulting dislocation of expression manifested bodily by the stammer. Rather than “reenacting” an experience for the listening doctor, experiences are involuntarily “reenacted” for the now livid audience of the dead and are, through their haunting recurrence, performed nightly on the stage of the patient’s neurasthenic psyche.

Time’s collapse was manifest, for many patients, in the inability to control or adequately manipulate speech—what Sassoon calls “the stammering of dislocated speech”; though speech is always located “elsewhere,” the metrical grid provided both spatial and temporal orientation. The metrical aspect of recovery is evident in Sassoon’s 1918 letter to Graves, in which words cram together nonsensically until the appearance of Dr. Rivers soothes the patient into almost mocking, yet ordered, double dactyls: “Sleeplessexasperuicide, O Jesu make it stop! / But yesterday afternoon my reasoning Rivers ran solemnly in, / With peace in the pools of his spectacled eyes and a wisely omnipotent grin.” Not only does Rivers’s appearance coincide with dactylic regularity in this line, but Sassoon, as a patient, transforms his self-loathing into self-appreciation (albeit ironic) through Rivers’s guidance into the patient’s “grey” unconscious: “And I fished in that steady grey stream and decided that I / After all am no longer the Worm that refuses to die. / But a gallant and glorious lyrical soldjer.” A “lyrical soldjer,” however, who resents how his mind is “crammed with village verses about Daffodils and Geese” and begs his doctor to free him of his misery: “O Rivers please take me. And make me / Go back to the war till it break me.”32 This passage is a case study for Captain Brock’s assessment of speech-disruption among sufferers of neurasthenic trauma: “The various affections of speech tend to run into one another; moreover, along with the stammer of the tongue we not infrequently observe a distinct ‘mental stammer.’”33 Here, we see how Sassoon’s writing runs together the unhealthy letters, cramming the dactylic “sleeplessness,” “exasperate,” and “suicide” into a stammering and traumatic metrical and material effect on the page. At once ironic and expressive, the passage consciously or unconsciously plays out the psychic condition Brock describes.

Brock elaborates on the officer’s unique relationship to disrupted time and speech in his 1923 book, Health and Conduct:

The shell-shock patient is out of Time altogether. If a “chronological,” he is at least not a historical being. Except in so far as future or past may contain some memory or prospect definitely gratifying, or morbidly holding him, he dismisses both. He lives for the moment, on the surface of things. His memory is weak (amnesia), his will is weak (aboulia), he is improvident and devoid of foresight. He is out of Space, too; he shrinks from his immediate surroundings (geophobia), or at most he faces only certain aspects of it; he is a specialist à Outrance.34

Brock’s analysis shows how the patient is both immovably moored in time and space—unable to move forward through language, so repeating sounds in a loop—and how the patient somehow unconsciously chooses his extreme detachment from both time and space. His thoughts cannot move forward, nor can his speech. The patient must be reeducated to see himself in time as part of a continuum, and he must reintegrate into the social world and his surroundings to face all aspects of experience. Brock advises treating the whole patient, not merely the symptoms: “[T]he far-seeing doctor will not allow the urgency of the local expression to blind him to the much more important general condition (otherwise — if he confines himself to dealing with symptoms — it will probably be as with the heads of the Hydra — ‘uno avulso, non deficit alter.’”35 Brock’s treatment methods were also Hydra-like in their efficiency— highly coordinated and diverse activities at the hospital were Brock’s solution for treating patient “inco-ordination” (146). The patients’ responsibility to manage their own time—through an endless array of physical and social activities—would, in Brock’s reckoning, force them to actively and metrically order their mental chaos by virtue of thinking through new contexts of time (the five-beat line of a poem, a first-person narrative or short-story, a play) and space (a diagram of the city, a lecture on botany, a description of local museums).

Brock encouraged patients to write metrical poetry but warned against the dangers of “art for art’s sake,” where art became a kind of drug that separated the patient from the social world; art for art’s sake could be seen as an extreme form of outrance. To counter this artistic tendency, artists and writers in the hospital were encouraged, indeed, required, to “produce beautiful objects of immediate and practical utility,” with the hopes that Brock could eventually “orchestrat[e] the work of all our artists towards cooperative programmes of regional or civil scope.”36 Objects of art, then, were subject to discipline just like any other “activity,” though as an exercise, writing was specifically a form of communication with a larger collective—of other patients, possible patrons (hospital magazines raised money for the hospital, and patients were charged for copies), and an imagined community of literary connoisseurs and other publishing poets.

Meter’s role as part of this connective tissue, hearkening back to prewar poetic forms, was perhaps the most important aspect of Brock’s therapy for Owen and other literary-minded patients. The ability to manipulate poetic language into English poetic form linked these soldier-poets to the larger field of English writing and of the country in general. In the hospital, even the poetic self was part of the collective history of the region and country; not isolated, but participating in his heritage, in the preservation of his own past and future, and in his own rehabilitation. Learning these tools relied on discipline and labor; what Brock called “ergo-therapy” reconnected the soldier to the social and physical world—to the structure and communities of language and country—from which he had become severed through the unnatural mechanizations of modern warfare.

On March 22, 1917 Owen quoted from memory a long passage from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh, condemning “many tender hearts” for stringing “their losses on a rhyming thread.” Owen confessed to his sister that he, too, had perhaps “sow[ed] [his] wild oats in tame verse”; he added, “this passage winded me, yea wounded me.”37 In a long letter to his brother one month later, we see Owen’s reliance on rhythmical form despite a reluctance to unconditionally endorse the traditional English poetic form haunting his letters. Owen laments the lack of a drumbeat as he describes to his brother the sensation of “going over the top”:

I kept up a kind of chanting sing-song: Keep the line straight!

Not so fast on the left!

Steady on the Left!

Not so fast! (458)

Owen begins “Keep the line straight!” on the same line as the letter, then indents the next three lines into a stanza for a little marching poem. The four lines, read together, each have three strong beats, but each also wavers with extra syllables as if to show how difficult it is to keep this line, or any line, “straight.” He seems to identify corporeally with the rhythmic form, as if by making the drumbeat himself, in his mind and voice, he will encourage his feet and those of his men to move forward. Reading the meter of these four, three-beat lines shows how Owen, himself, broke them as if to indicate how the “chanting sing-song” was, in his mind, charged with the responsibility of keeping him moving forward. It is clear, however, that the only lines that allow the quatrain’s movement are those crammed with syllables around the beat; that is, the iamb and anapest of “Not so fast on the left” lifts the line up and hurries it through the unaccented syllables of the words “on the” so as to keep time with the line, just as “Steady on the Left” slows through “Steady,” shaking the pronunciation of the word so that it becomes unsteady. The three monosyllables that are also, perhaps, three stressed syllables, exclaim “Not so fast!” and show the poet and the soldier’s inhibitions about moving forward, seeming to pull the small poem back into itself—a retreat from metrical feet altogether. Absolving the line from any unstressed syllables, any “sing-song” is a direct confrontation of that standard metrical culture; a retreat from regularity as the soldier-poet approaches that other three-syllable space of “no man’s land.” This small quatrain indicates the simultaneous forward and backward instincts of cresting the top of the trench into no man’s land. But the poet’s employment and manipulation of, as well as his deviation from, metrical forms also shows the poet-soldier’s wavering line; Owen cannot keep the line straight, nor can the (poetic) line keep him (mentally) straight. He composed this particular letter from the casualty clearing station in straight lines following standard issue ruled paper, after suffering the shell blast that would manifest itself as neurasthenia.38

Owen arrived at Craiglockhart on June 23, 1917 and met Dr. Brock in his office for the first time four days later. Brock recognized that Owen was a “devotee” of writing; in the hospital, his poems took up issues of feet, rhythm, music, and sound as primary and secondary themes, especially in the war poems. Three instances show how assignments by Dr. Brock directly influenced Owen to associate survival with his ability to manipulate poetic form, (metrically, as he had been taught). First, Owen was assigned a report on Outlook Tower in Edinburgh—a tall medieval house adapted as a center for sociological studies. On July 14, 1917, Owen read the following notes to his doctor: “I perceived that this Tower was a symbol: an Allegory, not a historic structure but a poetic form. I had supposed it to be a museum, and found it [a] philosophical poem: when I had stood within its walls an hour I became aware of a soul, and the continuity of its idea from room to room, and from storey to storey was an epic.”39 Owen fuses the spatial allegory of poetic form to the temporal allegory of narrative structure—an order for wholeness. He acts out Brock’s desire that the patients participate in the larger community, but through his reconsideration of poetic form he sees himself as part of a specifically literary community; indeed, through Owen’s poems we are able to perceive poetic form as a kind of historic structure.

Brock saw the mechanizations of modern war as inherently unnatural and sought to reunite his patients to their social as well as natural environments. The land, of course, was Britain, and geographic knowledge—an ability to map out one’s surroundings, to navigate—was an important part of “reconnecting to one’s environment” as well. Brock composed an article about the Anteaus myth for The Hydra, noting how “His story is the justification of our activities. When we come here the first thing we do is to get on our legs again…. Thus we come “back to the land” in the most literal, as well as the more metaphorical sense.”40 Like Owen’s assignment to write about Outlook Tower, Brock saw Owen’s concern with poetic form as one way that the neurasthenic soldier could reorder his understanding of himself in time and in the larger context of English writers. Owen simultaneously worked on a presentation for the newly created “Field Club” at the hospital and on his second literary assignment for Dr. Brock, the composition of a poem about the Anteaus myth.41

Owen approached the composition of his Anteaus poem as a spatial problem. He wrote to his mother, “On the Hercules-Anteaus Subject — there are only 3 or 4 lines in the Dictionary. So I shall just do a Sonnet.”42 By the time he wrote to his cousin Leslie Gunston a few days later, the poetic form progressed from the two stanzas or two rooms of a sonnet to a larger blank verse epic, or what Owen calls “a strong bit of Blank.” This lengthening of form from finite to continuous in both the Outlook Tower essay and the Anteaus fragment demonstrates Owen’s consideration of a possible literary, or heroic, future—a perpetuation of life like the perpetuation of the English poetic tradition he imagined for himself as a younger poet. In addition, by sharing the poem with his cousin Leslie, Owen reached out to his prewar poetic community.

… How earth herself empowered him with her touch

Gave him the grip and stringency of Winter,

And all the ardour of th’invincible Spring;

How all the blood of June glutted his heart,

And all the glow of huge autumnal storms

Stirred on his face, and flickered from his eyes. (477)

The sound patterns of this early version of the poem foreshadow Owen’s later mastery of interwoven sound structures. Each season seems to have its own sound sown within the line; the “er” sound of line 1; the soft “i” and “n” of line 2; the “ah” and “er” of line 3.43 These alliterative effects are signaled by metrical stresses as well, alternating within Owen’s stringent blank verse. The “blood of June” that “glutted the heart” of Anteaus can be read as a memory of the blood of June in the battlefield Owen has escaped. These powers, drawn from the seasons of the earth, are only available to Anteaus when his feet are firmly planted on the earth, to the roots of words and to their geographies of phonemes and inner structures, not just the metrical forms imposed on language from without. The “stringency” and discipline of winter must come before the “ardour” and “invincible” spring of the young and hopeful soldier until finally the blood of June battles triumphs. In a letter written the same day to his mother, he quotes a longer excerpt from the beginning of the poem, describing how Hercules was “baffled” by the strength of his opponent, and fixed his feet firmly to the earth. The line, “And yet more firmly fixed his graspèd feet,” shows how the strength of the ten-syllable line is bolstered by the diacritical mark promoting an artificial second syllable in “graspèd” (in a later version, Owen revised this word to “grasping” to keep the two syllables and remove the diacritical mark). The figures in the poem struggle through their feet—Hercules’s feet are “firmly fixed” though the poem’s metrical feet are not, jostling between iambs and trochees. The poem’s feet are more like Anteaus, pulled away from the firm ground of English poetic form: “How, too, Poseidon blessed him fatherly / With wafts of vigor from the keen sea waves, / And with the subtle coil of currents — / Strange underflows” (477). The word “coil” is also promoted to two syllables here, expanding a word that means contraction to arbitrarily lengthen the line to ten syllables. The poet is wrestling with unruly feet themselves, the beginning of a metaphor for time and measure that appears in many of his later war poems and, most significantly, in his substantial writing for The Hydra.

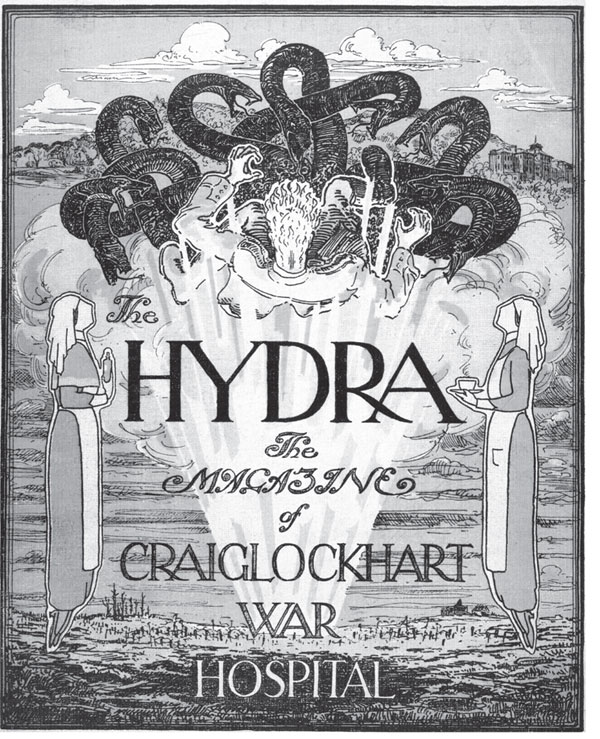

The most notable activity Brock prescribed for Owen was the editorship of The Hydra. Most hospitals that treated shell shock had small papers or gazettes that published hospital activities, though none were quite as literary as The Hydra.44 Not only did The Hydra provide the kind of comradeship between officers that Brock recommended, it specifically demonstrated the indelible forms of education that each officer carried. Through its frequent allusion to literature, classics, and the arts, the magazine allowed the officers to associate with both their social class and with past communities of school and home. The journal was entirely patient-run—evidence of Brock’s influence. Already relying on the forms of classical knowledge shared by most officers, the first editorial states: “The name of the journal will indicate what we wish its character to be: many headed—many sided” (April 28, 1917). The name Hydra was not only a reference to Hercules’s labors, but also referred to the fact that the hospital was a former hydropathic sanitorium, dubbed “the hydro” by its wards. Through the articles published in The Hydra (especially during the four months when Owen was editor), we come to understand how writing at Craiglockhart was a part of the therapeutic process of organizing neurasthenic time.

For instance, the September 15, 1917 issue, under Owen’s editorship, includes an eerie cartoon of Captain Rivers, drawn by “one who has not seen him.” Rivers is dressed as an Oxford tutor and stands on a pedestal of books while four officers sit in the background passively waiting for the wand-bearing wizard to cure them. (From the Casualty Clearing Station, Owen wrote to his sister Mary on May 8, 1917: “The Nerve Specialist is a kind of wizard, who mesmerizes when he likes: a famous man.”45 The soldiers in the drawing show no sign of functioning or taking control of their own activities; they sit slumped in chairs as if in a trance. A scroll in Latin swirls above Rivers’s head: “Styx Acheron Phlegethon Lethe Cytis Avernus,” but upon closer examination we see that the doctor is reciting, the scroll leading ominously back to his mouth. The pun on “rivers” is clear in the translation from the Latin; these are the names of “rivers” Virgil and Dante encounter in The Inferno. Rivers stands on the stage of literature with a book ignited in flame in his left hand, asking his charges to confront their own personal hell of traumatic memories, as if to show how despite all the discipline and authority in their education and military training, there will always be a chaos threatening to ignite at any moment. There is, in the postures of the slumped men, the sense of complete passivity; despite the mesmerism of the “wizard” doctor, there seems a distinct possibility that these men are broken beyond repair. In this way, the cartoon offers another subtle questioning of the military and therapeutic orders the men are expected to follow in the hospital. The cartoon, then, shows how education and psychotherapy are perhaps inadequate forms of discipline and self-preservation in the face of neurasthenic “hell.” This scene replicates and mocks the forms of classical education to which the officers were privileged, while at the same time showing how they are dependent on these same forms in the hospital.

Figure 4. Cartoon of Captain Rivers, anonymous, published in The Hydra on September 15, 1917. Copyright Jon Stallworthy, Wilfred Owen Estate. Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, OEF Wilfred Owen Collection, Box 37.

The Hydra received enough financial support by September 1917 that the editorial committee pleaded for more submissions and a different cover for what was to be the “new series” in November 1917 (the month of Owen’s discharge). “We make a last appeal for an attractive cover design—a promising futurist thing, if you will; anything but a future promise” (September 29, 1917). We may read a grim humor in his phrase, “future promise.” In the fantastic new cover (see figure 5), the rigid military forms of the original cover picture (with its austere-looking officer standing in front of the square hospital building) are blasted away by the fluid drawing of a soldier propelled backwards by a shell blast shaped like the multi-headed hydra, both a classical reference and a gesture to the former use of the hospital. The hospital is barely visible, perched up on a hill in the far right corner, and the scorched earth below resembles the pocked moonscape of Owen’s 1917 poem, “The Show”: “a sad land, weak with sweats of dirth, / Grey, cratered like the moon with hollow woe” (155). The soldier has lost hold of a book; in both this drawing and the cartoon about Rivers, literature’s ability to heal is dramatized and, ultimately, questioned. It is as if, in some small way, these artists demonstrate that literary form cannot possibly contain the horrific and fantastical visions of a world blown apart and scorched by war.

Owen attempted to steer the magazine toward his own literary aspirations by begging for more verse submissions in every editorial. Though Owen printed two of his own poems in the magazine (anonymously), his editorials provide indirect mediation on coming to terms with the different requirements of therapy at Craiglockhart, and show how his own poetic writing might be read for “marks” of neurasthenic disconnection from time’s proper marching. In many places in the magazine we see the contrast between Brock’s methods, geared toward work and activity, and Rivers’s, geared toward expression of repressed experiences. Unlike Sassoon’s characterization of Rivers’s methods, in which the doctor asserts control over a passive patient’s chaotic psyche, Brock’s patients are hyperaware of their own active attempts at control. Brock writes:

In the act of normal individual functioning … all the elements of time are involved. [The subject’s] present action bears relation not only to his actual circumstances but is based on his past experience … and reaches forward into his future. The action of a neurasthenic does not show this equilibrium, this evenly-balanced flow … the attention of the neurasthenic may become temporarily arrested upon some element of his past or future experience, and he develops a worry or definite phobia.46

Figure 5. New Series. Cover design by Mr. Adrian Berrington, published in The Hydra, November 1917. Mr. Adrian Berrington is credited by A. J. Brock in the May 1918 editorial of The Hydra. Copyright Jon Stallworthy, Wilfred Owen Estate. Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, OEF Wilfred Owen Collection, Box 38.

Brock called the fear of properly functioning in linear time, “ergophobia.” The magazine takes on “ergophobia” as a leitmotif, spoofing one officer who cannot think of a useful hobby and begins to have nightmares about his inability to occupy himself, and scolding patients who do not submit writing to the magazine as sufferers of “hydra-phobia.”

In homage to and mockery of Dr. Brock’s goals of adherence to linear time, Owen’s August 18, 1917 editorial recounts the misadventures of “Private Time,” condemned by “Colonel Eternity” to Eternal Field Punishment for “refusing to stand still on parade.”47 The soldier is ordered to “Mark Time.” Though “Marking Time” is a military command requiring that the soldier lift each foot six inches off the ground without moving forward, here it stands in evocatively for shell shock—the patients are unable to move forward in time and are thus mentally marching in place. For officers like Owen, trained in classical and English verse writing, “marking time” would also be familiar as a method for scanning classical quantitative verse (dividing it into “feet”). Like Owen working out his metrical feet in lines of verse while recovering from trauma in the hospital, the character of Private Time is compelled to “mark time” strapped to the earth on eternal march. He eventually grows weary, but a policeman, aptly named “Private Watch,” is hired to make sure “Private Time” does not “stand still.” Of course, the officer’s body is never moving forward because it is the earth that moves beneath his feet; “marking time” is merely “putting down the feet” without making progress, as arbitrary as any order. Metrical exercises are made arbitrary, just like precise military footwork that, in this instance, prevents the soldier from moving forward. Both Private Time and the policeman grow weary after so much work: “It was, and is, called ‘the Small Hours,’ and is open from 1:30am to 4:30am.” Private Watch steals into these hours and “Time, in his absence, stands still, and has a rest. And hence arise many of our troubles” (emphasis Owen’s). Owen’s piece ends:

But a way has been found. Knights of the Bedchamber, your vigils are at an end! Not long ago a magazine called The Hydra came into being. Its main idea was to contain things written while the policeman was in “The Small Hours.” Then others started to read what had been written, and immediately fell asleep. Forgotten were the maladies, even to the very worst, which, in our opinion, is Hydra-phobia. When men lay out a golf-course, buy a pipe, or engage a cook, they do so with a purpose. When men start a magazine they do so because — because — we offer a “ticket” for the answer. (7)

The stammer of “because — because” could show the writer’s doubt as to what the true purpose of The Hydra is, but, referring to the paper on which the magazine is printed, the “ticket” of writing and reading is seen as a way out of malady. In the magazine, writing is considered part of the cure—both because the writing is so poor it causes one to fall sleep, but also because the fact of writing might help the process of expressing the repressed memories that cause the nightmares. The impossible ticket, the dream of every soldier, was the “ticket” that meant official discharge from the army, especially for medical reasons, before the full period of service was up. To “work one’s ticket” was to attempt, through scheming, bribing, or malingering, to get out of the army, and came to be known as a genial and facetious suggestion that a man was mentally defective. Despite the jovial tone, we see Owen’s interpretation of the intolerability of waiting until dawn, of the dreams that double-back to memories, of the trap of trauma. In this article, we see the physical staggering of the tired soldier forced to march transformed into a soldier whose symptoms prevent him from moving forward in time. The arbitrariness of the military exercise is also a sly reference to the arbitrariness of writing under the auspices of rehabilitation.

At Craiglockhart, officers who were unable to imagine themselves outside the traumatic “stopped time” of neurasthenic trauma were sometimes able to piece together a functional relation to time’s movement through writing poetry, though their recovery meant an inevitable return to battle. As Brock’s successful Anteaus, Owen learned to manipulate the complex relationships between his feet and his head, action and expression, and returned willingly to the front where he continued to write with an increased self-awareness. Re-reading Owen within the larger contexts of English national meters and the metricality of therapeutic healing, we can see how his poems try to reconcile the empty patriotic promises of prewar poetry and militarism. Indeed, with this in mind, Owen’s habit of scanning below a poem seems particularly evocative, as if the marks do not need the letters beneath them to provide some form of comfort. His poems often contain metrical marks, and revisions show him trying to think through the complexities of metrical form.48 However, in the poems he writes at Craiglockhart and after, Owen critiques the dangers of following rote militaristic feet and struggles with the question of how poetic form’s future possibilities for meaning might be always determined by its inability to preserve, comfort, or even endure.

Owen composed a fragment in his last months at Craiglockhart (dated August–September 1917) titled, “All Sounds Have Been as Music.” The 18-line poem begins: “All sounds have been as music to my listening: / Pacific lamentation of slow bells, / The crunch of boots on blue snow rosy-glistening, / Shuffle of autumn leaves; and all farewells.” The poem continues on to name country bells clamoring and a host of other traditionally pastoral images, but the fourth stanza includes “startled clarions” and “drums, rumbling and rolling thunderous.” Here, the crunch of boots is swept up in the idealized country life, and he leaves the last stanza unfinished, taking up these images and sounds as part of the betrayal he explores in his most famous war poems, “Anthem for Doomed Youth” and “Dulce et Decorum Est.” In “The Calls,” written in May 1918, some six months after his return to service, he begins each stanza envisioning a world measured by regular sounds, “a dismal fog-hoarse,” “quick treble bells,” “stern bells,” “gongs hum and buzz,” each occurring at a specific hour (much like his descriptions of military time in his letters). The fourth stanza dramatizes the “clumsiness” of soldiers trying to follow along in some sort of forced regularity: “A blatant bugle tears my afternoons. / Out clump the clumsy Tommies by platoons, / Trying to keep in step with ragtime tunes, / But I sit still; I’ve done my drill.”49 The manuscript copy shows that Owen deleted the lines “I’ve had my fill” and “Here I’ve no rime that’s proper.” Regularized external sounds, then, are allegorized in Owen’s poems as disciplines or forms aware of and suspicious of their own value while, at the same time, the internal sounds of the poem, contracting and expanding in his metrical manipulation, simultaneously support and reject this allegory. “The Calls” admits that the sounds and forms of military and literary discipline are necessary, even if he has no “proper” way to express this unfortunate necessity. Other more blatantly antiwar poems violently question the necessity of military and metrical discipline.

There are many examples that demonstrate Owen’s formal reckoning but few are as effective as his now canonized “Dulce et Decorum Est,” which he began writing at Craiglockhart in October of 1917.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots 5

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling,

fitting the clumsy helmets just in time; 10

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime …

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all of my dreams, before my helpless sight, 15

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin; 20

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, —

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest 25

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The form of Owen’s poem is itself “bent double,” like the soldiers it describes. Many critics have noted the poem’s similarity to the Shakespearean sonnet form as well as its implicit reference to Wordsworth’s “Leech-Gatherer”: “Such seemed this Man, not all alive nor dead, / Nor all asleep — in his extreme old age: / His body was bent double, feet and head / Coming together in life’s pilgrimage.”50 The poem is, in fact, two sonnets, bent and doubled in the middle at lines 13 and 14, where the lines that would normally form the final couplet in a Shakespearean sonnet simply begin a new rhyme: “light” and “drowning.” Despite the formal buckling or juxtaposition with the second sonnet, the formless figure of the dying man provides a perfect thematic coda to the first octave, in which the men’s marching is subdued in a sort of sleep. Indeed, in the sestet, the man’s figure is obscured and shapeless as if underwater, his image seen through dim, thick, green light. The verbs and adjectives in the first sonnet—trudge, lame, blind, drunk, deaf—subdue the imagined activity into an embalmed slumber (these verbs reminiscent of what one would witness in the halls of Craiglockhart) Even the flares become part of a hazy backdrop, and the menacing shells drop “softly,” like petals.51 Likewise, the soldier’s movements are calm and imperceptibly shuffling to a failed attempt at iambic pentameter, as if the spondaic opening of “Bént dóuble” and “Knóck knéed” of lines 1 and 2 show the extra step each man must take. When the lines settle into five stresses, in lines 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8, the iambs are consistently irregular, alliterations causing frequent trochaic and spondaic substitutions. The iambic pentameter seems perceptible enough, but the fact that these steps are complicated suggests that Owen, here, is lulling us into an expressive reading of regular accentual-syllabic meter. We might imagine that we think we know what kinds of steps the soldiers should be able to take, but are unable. Only line 4, of these beginning lines, adheres to the perfect five-beat iambic pentameter line: “And towárds our dístant rést begán to trudge.” The meter marches asleep here, stumbling through a rhythm that is ruled by sound patterns rather than any traditional military or literary discipline. Line 6, the longest line of the first octave, is heavy with extra stresses and halts with three pauses—“But límped ón, // blóod-shód. // Áll went láme; // áll blínd”—as if this ten-syllable line could be divided into four, two-beat lines (complete with the pararhyme of “blood” and “blind”). The men’s feet and the metrical feet limp on, shod in no protective form for the rhythmic beats.

Lines 9 through 12 express metrically the gasping repetition of “Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!” Quickly, the soldiers move—fumbling, stumbling, and fitting—as the form performs, back into the traditional ten syllables “just in time.” The stumbling and fumbling of the poem is juxtaposed against the rigidity of lines 11 and 12, which are, like line 4, in exact pentameter, as if tradition somehow regularizes this chaotic moment; that is, Owen flaunts a moment of extreme metrical regularity at the chaotic center of the poem. We hear the iambs again from the middle of line 10—“the clúmsy hélmets júst in tíme; / But sómeone stíll was yélling oút and stúmbling, / And floúnd’ring líke a mán in fíre or líme”—with Owen careful to elide the “e” in floundering to keep the realigned meter regular. The man, “still” in the middle of the chaos, is caught up in the trudging slumber of the traditional iambs. Instead of a calm, sleep-ridden march, the meter of this first sonnet is thrown into suspicion. When called upon, the soldiers who could recover from their stumbling to move “just in time” were saved from the defeat of the trapped soldier, the “someone still” of the sestet. But not only is the iambic pentameter of a traditional sonnet bent and doubled in this poem; the sound structure in the first sonnet also performs a sort of bent doubling. If the meter of the first sonnet stumbles, the sound structure stammers—both the metrical and alliterative effects in the poem manifesting symptoms of trauma in their formal performances. In each line in the first octave, the sounds double on either side of a real or imaginary caesura (bent/beggars, coughed/cursed, til/turned, toward/ trudge, men/many, blood/blind, drunk/deaf). Some of these sounds gesture toward Owen’s experiments in pararhyme, taking out the vowel center of a word and leaving the skeletal structure of the beginning and end consonants, but these stammering sounds also show how subtle repetition, like the stumble of metrical feet, coaxes the poem forward to the sound that occurs in the middle of the line while also demanding that it double back to the sound at the beginning. These effects fade in the would-be sestet: “still” morphs into the sounds of “stumbling” in line 11, and “sea” into “saw” in line 14, neither a true stammer but more a “see-saw” of imbalance to signify the defining feature of the first sonnet’s movement.