1

1

When this, this little group their country calls

From academic shades and learned halls,

To fix her laws, her spirit to sustain,

And light up glory through her wide domain;

Their various tastes in different arts display’d

Like temper’d harmony of light and shade,

With friendly union in one mass shall blend,

And thus adorn the state, and that defend.

— Anna Laetitia Barbauld, “The Invitation: To Miss B*****”

Upon few other subjects has so much been written with so little tangible result.

—Coventry Patmore, “Prefatory Study on English Metrical Law”

When you are at school and learn grammar grammar is very exciting.

— Gertrude Stein, Poetry and Grammar

With the above lines from “The Invitation” by “Our Poetess” (Anna Laetitia Barbauld), William Enfield begins his 1774 The Speaker, an elocutionary handbook that was intended for use in classrooms at the moment when vernacular literature was beginning to displace classical literature in private grammar schools.1 Enfield was a schoolmaster at the dissenting Warrington Academy, and both he and Anna Laetitia Barbauld (daughter of schoolmaster John Aiken, also of Warrington Academy, and author of The Female Speaker [1811]) were invested in the cultural capital of English literature. As John Guillory describes it, “by the time Thomas Sheridan published British Education: Or the Source of the Disorders of Great Britain (1756), the connection between vernacular linguistic refinement and a progressive political agenda was firmly entrenched.”2 Urging English literature as “models of style,” Sheridan expressed “anxiety . . . that in the absence of an institutional form of dissemination, literary culture [could] not be entrusted to preserve English works of the past.3 It is in this climate that Barbauld imagines a collective classroom community in which (as the epigraph to this chapter states) “academic shades and learned halls” will “fix the laws” of the English language and do their duty: “with friendly union in one mass shall blend / And thus adorn the state, and that defend.” Barbauld hints at the act of friendly union between England and Scotland in 1707 in her imagined classroom, a classroom in which the potential differences in English pronunciation might blend into an English language that “adorns” England with its greatness. By bringing together students to practice reciting English literature and learning English grammar, education would inspire all students subject to the English language to defend Britain.

In the late eighteenth century, this classroom community was limited. Dissenting academies (schools, colleges, and nonconforming seminaries) like Warrington provided an education for those who did not agree with the tenants of the Church of England,4 which had a stronghold at Oxbridge. Those who could pass the entrance exams to the old universities (Oxford and Cambridge) were educated in grammar schools or by schoolmasters or schoolmistresses in the ancient languages. Elocutionary guides, grammar books, and other pedagogical literature rushed to fill the void created by England’s express desire, after the publication of Johnson’s Dictionary in 1755, for a unified linguistic and literary culture at a time when it lacked any organized national school system to support it. Intended to provide a “proper course of instruction,” Enfield’s Speaker and John Walker’s Elements of Elocution (1781) were two of the most popular guides to the proper performance of speech for those aspiring to the upper classes as well as for those already in the upper classes who wanted to supplement their classical educations with a working knowledge of English literature. “By a steady attention to discipline,” Enfield’s speaker promised the literate, who were willing to practice, the ability to pass as aristocracy. Here was no course of study for the mere hedge school or church school, though that was exactly the sort of community that would find these lessons useful. For both Enfield and Walker, “accent” should follow the abstract “laws of harmony,” “general custom,” and “a good ear.”5 Though the Scots dialect was everywhere present in eighteenth-century discussions of “proper” English speech accent, the hope of these and other late eighteenth-century textbooks was for a national unity that could be achieved through linguistic unity. But linguistic unity, for these popular elocutionists, also meant a unified approach to the measure of English speech in poems (ever popular for recitation) and therefore a unified approach to English meter.

Though Fussell has argued that the idea of classical quantity in English was practically irrelevant in eighteenth-century English verse, supplanted by “conservative” syllabic and stress regularity (the number of syllables and stresses per line), the dream of establishing universal and standard pronunciation was nonetheless evident in discussions of versification. Prior to phonetic science, authors like Enfield and Walker often took for granted the ideal of sameness in “English” quantity (the short “e” versus the long “e” for instance) and therefore in pronunciation. Because their idea of proper speech was so ingrained, Enfield and Walker eschewed a system for measuring meter through quantity at all, as a student of the classics would have, precisely because “quantity” would have been associated with classical languages and literature, on the one hand and, on the other, actually providing rules for quantity in English would mean securing, standardizing, and fixing pronunciation in a concrete way that neither Enflield nor Walker was yet able to imagine. That is, the abstract notion of “speech accent” (or emphasis, or just “accent”) is paramount to the proper measure of an English verse line, quite beyond the rules for pronunciation that nineteenth-century grammar books would establish. In fact, as if to preclude any disagreement, Walker writes “it is accent, or emphasis, and these only, and not any length of openness of the vowels, that forms English metre,”6 Both writers are invested in speech accent as the only ruling constituent of the English verse line. By erasing questions of English quantity, Enfield and Walker effaced the very differentiation of speakers from different regions of the country. If accent is the only measure of English meter (rather than the time it would take to pronounce the words, or the different ways the vowels might sound), then all Englishmen (irrespective of their Scottish origin) can access it. An idealized and yet-still-unestablished “English” accent, when properly learned and performed, would not, according to these rules, differentiate speakers; rather it would blend them into the “one mass” of the English nation.

With the expansion of the franchise, the growth of the linguistic sciences, and the rise of a state-controlled and somewhat regulated education system, English would haltingly replace the classics as the language and literature of the educated elite in Victorian England. But before the anxieties later in the century about the adequacy of English literature’s role as a civilizing force, the study and attainment of “proper” English pronunciation and usage was already associated with upward mobility and national stability. Within the narrative of the “rise of English,” (which begins even before the eighteenth century) we also find the “rise of meter” in popular pedagogical textbooks in English history and grammar. English “meter” emerges as an important yet still hotly contested and unstable medium for the transmission of English values.7 Despite what Fussell argues are the widely held beliefs of the eighteenth century, that “prosodic regularity forces the ordering of the perceiver’s mind so that it may be in a condition to receive the ordered moral matter of the poem,” the desire for a stable and regular prosody was often complicated by the unstable ways that these terms (“prosody,” “meter,” “versification”) circulated. The apparently specialized terms “prosody,” “meter,” and “versification” enjoyed a surprising prominence in English national life, in unexpected arenas. “Syntax” and “prosody” circulated not only in grammar books, but also as cartoon characters, even popular racehorse names. School stories (popular “boy’s tales from school,” such as Tom Brown’s School Days [1857]) often included stories about Latin exercises as punishment and bemoaned the rigors of scansion, yet the bout-rimé was a popular pastime throughout the Victorian era. Mnemonic jingles were used to teach a variety of different school subjects. From the middle of the eighteenth century onward, the terms “prosody” and “meter” mediated between elite and mass cultures, Latin and English, speech and text, classical and “native” pasts, “England” and its others.

Nineteenth-century poetics developed via a vast, unruly array of handbooks, manuals, periodical articles and reviews, memoirs, grammar books, philological tracts, essays, letters, and histories, all with something to say about English meter. Prosodic discourse extended into multiple disciplines, each with different disciplinary practices, expectations and, importantly, different audiences. These diverse methodologies and disciplines, however, came together to lay the groundwork for English literary studies as we now know it—a product of this cross-disciplinary project of nation making. To illustrate the centrality of meter to this nation-making project, the first part of this chapter studies nineteenth-century English history teaching, which employed various concepts of English “meter” to solidify a stable concept of England’s regal past. I then turn to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century grammar books to show how, despite the hopes of grammarians to stabilize all aspects of “English grammar,” English meter continued to evolve and change, playing a liminal and shifting role in the evolution of English grammatical study. The delineation of English meter in Victorian grammar books exposes many facets of the controversies that erupted in the later nineteenth-century “prosody wars.” Grounded in Latin grammatical and metrical theory (about which scholars disagreed), but grappling with broadening cultural and historical contexts, grammar books reveal an oft-neglected ambivalence about English meter as grammar. Late nineteenth-century conflicts about meter are rooted in the disciplines of rhetoric and elocution, and even a subtle tension between classical and Anglo-Saxon meters. Through the study and investigation of both Anglo-Saxon and classical meters—and also of Anglo-Saxonism and classicism—historians, grammarians, and prosodists attempted to define concepts of English national identity that were often redefined radically by the century’s end. The final section of this chapter broadly outlines the contours of prosody debates throughout the century, arguing that prosodic discourse was founded on disagreement and discord, and that the dream of a system for English prosody was also a dream of a stable national identity that was, perhaps, unattainable.

Though the use of versification to teach history might not seem all that different from using versification to teach other subjects, “metricality” in history teaching sometimes called upon a “natural” and emphatic rhythm that was distinct from subtly modulated rhythms of more “refined” poetry and the technical vocabularies that were being developed for these. Simple rhythms, called “meter,” made it easier for the student-subject to memorize historical chronology. Hundreds of “metrical histories” appeared in the nineteenth century. These “metrical histories”were associated with progress in two respects: first, this somehow more natural “meter” was seen to aid the natural development of mental order and discipline; second, the periodicity and seeming inevitability of the succession of regents aligned meter with the development of the English nation. The pedagogic use of versification in teaching history promoted an understanding of English verse form as an emblem of order itself, applied to, but also derived from, a progressive and dynastic English past. English metricality, rather than English poetry or versification, was a popular vehicle for knowledge that skirted aesthetic questions and raised ideological questions instead. The “metrical histories” of England, then, can be read as the union of a particular idea about English meter with a particular idea of English national culture—orderly and falling into a natural line that should be easy to remember. At the same time, while this kind of “meter” may be easy for some to remember, the idea that “meter” could create mental discipline was derived from the traditions of memorization in classical education. Some metrical histories included an ironic subtext for more educated readers, employing subtler metrical systems but marketing their texts to the lay reader, who may not have any idea of what metrical forms were being employed. In that way some “metrical histories” spoke to more than one metrical community. Others were careful to separate their method of “versification” from a perceived aesthetic category of higher “poetry” with standards against which they did not wish to be judged. In all of these texts, however, even those that promote ease and pleasure in memorizing verses, there is a hint of the inherent difficulty and artificiality of meter—a meter that is not natural, that is not, in fact rhythm, which is what these texts mean when they say “metrical” in the first place. That is, while the ideologies of history pedagogy and mental ordering for the masses relied on metrical order, we find, especially toward the end of the nineteenth century, a suspicion about a form that could control you without your knowledge, an issue that was central to the teaching of poetry and the approaches to poetic education promoted by scholars like Matthew Arnold and Henry Newbolt at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries.

Reading these histories in meter, and the meters of these histories, shows the tangled metrical and historical genealogy of England’s classical and Anglo-Saxon pasts. For instance, we find what may be an entirely accidental line of dactylic hexameter (a meter associated with England’s history only explicitly through translations) in the subtitle of Seymour Burt’s 1852 Metrical Epitome of the History of England: “A Metrical List of the Sovereigns of England: // The Angles and Saxons.” These hexameter lines reveal that English metrical history is more complicated than even the most straightforward-seeming metrical list of the earliest leaders of England. Though Burt writes the text of his metrical history in the more accepted Anglo-Saxon four-beat line (complete with alliteration on either side of the caesura), the dactyls of the subtitle regulate the following alliterated lines:

Egbert and Ethelwolf, Ethelbald, Ethelbert

Ethelred, Alfred, and Edward and Athelston

Edmund and Edrid, and Edwy and Edgar

Edward and Ethelred, “Ironside” Edmund.8

Though these alliterative four-beat lines hint toward the dactylic pattern of the title, they seem to Anglo-Saxonize the possibility of dactylic hexameter, so that the subtitle reads, in retrospect, as a preview of the list to come—“A Metrical List of the Sovereigns of England” and then another subtitle: “The Angles and Saxons.” Rather than civilize the Anglo-Saxon names into classical feet, the accents of the subtitle stand out prominently. But Burt does not attempt to make his metrical list imitate Anglo-Saxon meter so much as he uses the naturally alliterating names of the sovereigns to hint at the common Anglo-Saxon metrical patterns of two beats on either side of the caesura. At the same time, Burt was conforming to a classical standard; dactylic hexameter was widely known as the heroic classical meter of both Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid. Though the title is certainly not signaling the classical nature of England’s history, the gesture to an epic meter with the Anglo-Saxon beats inside it makes the names of England’s earliest leaders seem appropriately epic themselves. That is, the only appropriate meter for naming the founders of the English nation might be this hybrid of classical and ancient English patterning. Burt adds the word “and” to make the verse even more dactylic when a regent’s name comes up one unstressed syllable short: “Edward and Athelston,” the “and” a conjunction that ties the rulers to one another, echoing the “d” ends of their names, and filling the dactylic line.

Despite Burt’s metrical performance, joining the alliterative Anglo-Saxon, four-beat line to the dactylic pattern, he states early on that his primary goal is a proficiency in pedagogical transmission of historical fact. In the preface, Burt offers his Metrical Epitome to the British public with “extreme diffidence” and “fears . . . of [his] skill in versification” (iii). Yet he has assurance, despite these fears, that the details and facts of the Epitome “may be looked upon with all confidence.” From diffidence in versification to confidence in the presented facts, Burt prefers to bolster the historical accuracy of his account as the most valuable feature of his Epitome and downplay the potential faults in the verse form. He assures the reader that he has included all “leading features” of England’s history but purposefully excluded any reference to the “more poetical incidents” (iii) in the record, thus protecting the reader from unnecessary (and potentially un-heroic) distraction. The “students of our History” (iii) who are his hoped-for audience should not be concerned with aesthetics, but should find the verses in which the facts are delivered to be simply the most effective vessels for transmission. With pedagogic simplicity at the forefront, Burt advertises that in a mere hour, his metrical epitome can provide the amount of information that a week’s reading “in the ordinary [prose] manner” (iv) would require. Burt’s use of the term “metrical” here means “narrative” or “vehicle for transmission and retention of a narrative pertaining to England” particularly. We can also read, in his reluctance to claim responsibility for his meter, that “meter” was also associated with a kind of potentially measurable accuracy, which his “epitome” would like to sidestep, or perhaps replace with the measurable accuracy of its historical account. What Burt takes for granted is that the regularity and familiarity of a dactylic tetrameter will only help the foreign-sounding Saxon names to become part of the English historical record.

Why would Burt need to fix these Anglo-Saxon names into the more familiar dactylic meter rather than into an Anglo-Saxon meter? The “metrical” of Burt’s Metrical Epitome is distinct from the varieties of English meters with which Victorian poets were experimenting and to which he himself alludes; it is also distinct from the rigorous classical meters of the public school and Oxbridge,9 not participating in any of the discord about translations into English from classical meters that took place at midcentury (translating the quantitative dactylic hexameter into a six-beat line.)10 Burt avoids explicit discussion of versification and begins his history with only these names, which call attention to their own, seemingly inherent strong-stresses—through the very Anglo -Saxon alliteration and mid-line caesura—while at the same time making them conform to a familiar dactylic pattern. Burt begins English history here, in a subtly hybrid past in which alliterative, stressed Englishness seems to overtake the familiar conventional dactylic tetrameter. As we will see, linguistic and metrical forms are often conceived as part of a series of narratives of conquest and submission, and even in this proclaimed non-poetic English history, we may read subtle tensions between national and metrical pasts.

In addition to these relatively inconspicuous details, however, Burt’s “metricality” was meant to counterbalance the supposed dryness of historical facts, to dress them up, organize, and stabilize them so that they could be more easily retained by the memory. “Versified” history organized the facts of England’s past so that the younger generation could remember it; just as the regents themselves provide an “order” to the epochs of history, so too did nineteenth-century meter, broadly conceived as part of English history, provide an “order” for the overwhelmed mind of the young student. This “metricality,” therefore, did not allude to the more complicated dactyls of the public schoolboy’s exercise in translating from Greek and Latin hexameters, though that exercise was intended to provide a similar kind of mental discipline. The intended audience for metrical histories needed historical knowledge first, with the verse forms, never named or discussed, securing that knowledge in a student’s memory. Like Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome, published ten years earlier in 1842 to astonishing success,11 these were histories first, and poems second, if at all. The very fact of historical fact absolved the verses of any poetic responsibility. Though the exact choice of meter in the metrical histories may not have carried a specific message, they were nonetheless influenced by the way that each author wanted his or her “English history” to be received. The fact that the often unnamed meters were simple, emphatic, and recognizable—ballad meters, double dactyls (common in nursery rhymes), and pentameters—nonetheless expressed a sense of community and connection. English meter in its various unnamed forms was familiar enough to make English history easier, and English history, in turn, joined English meter (or at least the adjective “metrical”) to a progressive national narrative.

The late nineteenth century saw the growth of “History” and “English” as disciplines that would eventually rival the classical curriculum, and both amateur and specialized metrical histories of England circulated widely in the period. The phenomenon of the metrical history, however, was not unique to the nineteenth century; many of the earliest histories of England were metrical, and many of the earliest poems in English were about the history of England. Layamon’s Brut, (or “A Chronicle of Britain, a poetical Semi-Saxon paraphrase”) written in the first part of the thirteenth century, tells the history of the Britons from the fall of Troy to the fall of King Arthur, and was published by the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1847. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the six editions of the progressive, cumulative, and multiauthor collection of poems The Mirror for Magistrates12 told verse stories of the lives of ancient Romans, ancient Britons, and even Queen Elizabeth and her immediate predecessors.13 Part ghost story, part national history, the Mirror for Magistrates participated in a pattern that continued in Spenser and throughout the eighteenth century of tacking ancient and contemporary English history onto the history of ancient Rome. The Mirror for Magistrates was a poem that told a story, or many stories, but seemed less concerned with whether or not the story was going to be repeated verbatim. In the eighteenth century, the metrical history begins to concern specifically English history and eschews the common myth of Roman origins, no longer recruiting these in the service of legitimizing a succession. Rather, the “metrical histories” become explicitly concerned with the successful transmission of English history and English values into the minds of its readers in a time of nation building and imperial expansion.

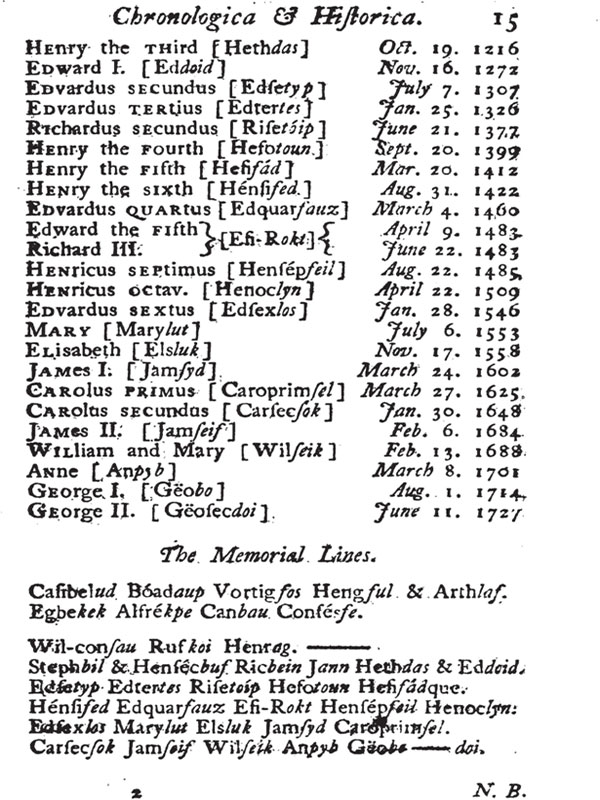

Scholars who wanted to teach a more “native” ancient English history in the eighteenth century turned to “artificial memory” methods, of which Richard Grey’s 1737 Memoria Technica is the predecessor. His “new method of artificial memory” was, as stated on the title page, “applied to and exemplified in chronology, history, geography, astronomy, and also Jewish, Grecian and Roman Coins, Weights, and Measures” and its methodology consisted of assigning sections of made-up words to events in history, so that syllables, or rather, phonemes, stand for numbers which, in turn, make up dates in a historical chronology. Grey’s Memoria Technica was written in barely perceptible hexameters, which are only evident if you read his preface, since the “memorial lines” read as a kind of Latinate gibberish, complete with entirely useless accent marks in superscript (see figure 1).

Despite their surreal quality, the metrics of Grey’s memorial lines nonetheless inspired later histories in so-called “mnemonic hexameters.”14 But beyond the epic nature of its rough meter, Grey’s Memoria Technica was concerned with measure to such a degree that the epochs of history, cycles of the moon, and ancient weights and measures all appeared reduced into one, albeit extremely complicated, system of assigning each historical figure his own letter—a mnemonic cipher. He admits that the verse structure is not as important as the cipher, writing,

to make this even easier to be remember’d, the Technical words are thrown into the Form of common Latin Verse, or at least of something like it. For as there was no Necessity to confine my self to any Rules of Quantity or Position, I hope I need make no Apology for the Liberty I have taken in having, without Regard to either, and perhaps now and then without so much as a Regard to the just Number of Feet, only placed the Words in such Order as to make them run most easily off the Tongue, and succeed each other in the most natural Manner.15

Since Gray’s “Technical Words” consist of such inventions as “Casibelud Bóadaup Vortigfos Hengsul & Arthlaf” (14), it is quite astonishing that he would be concerned with the “natural” manner that these words would be pronounced out loud. Bringing a whole new level of pedagogical and cultural meaning to the idea of poetic “numbers,” which usually refer, as above, to the number of feet, syllables per a line of verse, or the quantity of time it might take to pronounce a line of verse, Grey’s “artificial memory” valued arithmetic over language and, indeed, subdued the idea of a dactylic hexameter to that arithmetic, shrugging off the obligations of Latin hexameter while at the same time admitting it may be helpful.

Despite its various contradictions and complications, the “artificial memory” system took hold and Grey’s odd volume went into eight editions. Richard Valpy took up the idea of Grey’s “artificial memory” but lamented that Grey’s verses were too difficult to memorize. In his A Poetic Chronology of Ancient and English History (1794), Valpy discards the complicated mnemonic cipher and happily hopes that a poetic form will simplify the method of memorizing history: “if the knowledge of dates, which is happily connected with that of facts, could be reduced to a poetical form, to a series of English verses, which might be learnt on account of their simplicity, and remembered without disgust, a benefit of some importance would be conferred on the rising age.”16

Figure 1. Illustration of the “artificial memory” method, applied to the regents of England. Richard Grey. Memoria Technica; or, a new method of artificial memory, applied to, and exemplified in chronology, history, geography, astronomy. Also Jewish, Grecian, and Roman coins, weights, and measures, &c. With tables proper to the respective sciences, and memorial lines adapted to each table. London: Printed for John Stagg in Westminster Hall, 1737, p. 15.

Rather than rely on artificial memory, the English verses (as opposed to Grey’s hexameters of invented Latinesque words) are memorable for their simplicity:

When years one thousand and threescore and six

Had pass’d, since Christ in Bethlem’s manger lay,

Then the stern Norman, red from Hastings’ field,

Bruis’d Anglia’s realm beneath his iron sway. (26)

Though these lines are syllabic (each containing ten syllables with the aid of elision) they are neither regularly nor emphatically accentual; they seem, rather, to be syllabic on the French model. There are, throughout, more emphatically regular lines, as the final stanza shows:

In sev’nteen hundred sixty, George the Third,

In Britain born, his people’s dear delight,

Receiv’d the scepter twin’d with laurel round,

And with fresh force renew’d the thicken’d fight. (52)

Just as we move closer to the present day, so too does Valpy grow more confident in his pentameters. But the pentameters were not really his; Valpy admits that his chronology was inspired by an anonymous Poetical Chronology of the Kings of England that appeared in The Gentleman’s Magazine17 over several months in late 1793 and early 1794, and that he had to perform “alterations . . . from a sense of moral and political propriety” on his source text. He explains:

It is the duty of a teacher to instill into the minds of youth the purest constitutional principles. He must have the care to reconcile the lofty sentiments of Republican liberty which occur in the perusal of the Greek and Latin writers, with a loyal submission to that form of Monarchy, which the experience of ages has proved to be the best calculated to insure private security, and to promote public happiness, in this country. (5–6)

Valpy admits that he rewrote lines from the prior chronology so as to save England’s princes from “unmerited obloquy” and “cruel invective.”18 It is no surprise that history writing is ideological and political; here, the loyal submission to the ten-syllable lines, often (but not always) rhymed abab, is also, explicitly, submission to that form of monarchy to which the “rising age” should pledge unequivocal allegiance (both accounts are written in pentameter, and Valpy only makes subtle changes to the original text). Valpy was a schoolmaster (he had already attempted to simplify Latin grammar and would later go on to simplify Greek grammar) and he intended his work to be used primarily in his own school, but the book went through sixteen reprints and was absorbed as the appendix to Putnam’s more historical, non-poetic chronology in 1833. If facts can be reduced to a simple poetic form, then the student might easily recall them, without the “harshness of measure” (4) to which we are subjected in Grey’s Memoria Technica.

Metrical histories that abandoned the “artificial memory” method, and abandoned “ancient history,” (meaning Roman history) began to appear in 1812, along with a revival of ancient ballads and translations from Alfred.19 Rather than focus on learning a new system, the majority of nineteenth-century metrical histories emphasized the ease with which verses could be remembered and the connective tissue to a metrical and national community that the meter provided.20 The wider historical context of a revived interest in all things Anglo-Saxon is important as a possible reason why many of the nineteenth-century histories, though they tended to be shorter and easier to memorize, began before 1066, returning to a pre-Norman past, rewriting the Battle of Hastings as “the Norman yoke,” as well as appealing to vernacular and less complicated verse structures, mostly ballads and tetrameters. Pedagogically, these metrical histories tended to emphasize that poetic learning could be pleasurable and, just as Anglo-Saxon was being rewritten as a native and natural form in English, so too did the nineteenth-century metrical histories tend to emphasize ease and instinct in memorizing verses. For instance, we can immediately sense the appeal of the popular late eighteenth-century song, the “Chapter of Kings”: “The Romans in England they once did sway, / And the Saxons they after them led the way, / And they tugg’d with the Danes ‘til an Overthrow, / They both of them got by the Norman Bow. / Yet barring all Pother, / the one and the other / Were all of them kings in their turn.” The song, by Irish schoolmaster John Collins,21 was printed in a slightly less vernacular form in 1818, changing “butchering Dick” back to “Richard” (but keeping the line that calls Henry the Eighth “fat as a pig”). Reducing the complexities of English history to a schoolroom song created communities of subjects who could easily imagine becoming “kings in their turn,” no matter their background. The refrain of “the one and the other” is particularly evocative at a moment when grammarians and rhetoricians, as scholars like Strabone and Elfenbein have noted, were attempting to suppress the internal “others” of Saxon-derived dialects in the process of standardizing English grammar.22 The fact that the song was originally composed by an Irish schoolmaster gestures to the way that nineteenth-century England often derived its native “authenticity” from linguistic communities that it had attempted to erase or eradicate.

The wide circulation of popular songs and ballads about English history promoted and sustained the perceived connection between England’s regal rulers, its folk communities, and vernacular poetic forms. But the trend to versify England’s history appealed to authors who were cannily aware of the way that the idea of “meter” would speak differently to differently educated readers and relied, therefore, on a common “history” to unify them. The popularity of the “Chapter of Kings” inspired Thomas Dibdin to “attempt versifying . . . the leading points of our history” in 1813.23 Though Dibdin wanted his verses to be entertaining, he also wanted them to be historically and poetically accurate. That is, rather than provide a history connected by the sameness of meter, he varies the form of the verse, or “the style of the narrative” as he calls it, “as the colour of circumstances to be depicted in each Reign might seem to require” (vi). He tries to make his account more historically accurate—and more entertaining—by matching different poetic genres such as “a Comic Song, a Tragic Tale, or an irregular Poem” to different eras of English history. The very variety of poetic genres within the already versified narrative might provide “relief” from the imagined rigor of so much history but, more importantly, might “impress on some juvenile memories a species of Index to the voluminous labours of genuine Historians” (vi–vii). In Dibdin’s index, then, the shifting style of meter signals a historical shift—the changing meters providing yet another level of organization.24 In Dibdin’s index, among other instances, a “history of meter” and a “metrical history” are one and the same.

Dibdin sought to appeal to two audiences with his versified histories: first, the readers trained at “Cam and Isis” (Cambridge and Oxford) who might still find his “insignificant” poem entertaining, and second, the younger generation of scholars who needed to get their history right. Dibdin plays on a theme that continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: meter was both a way to convey information to a specialized class of people and a way to help people learn and organize information, and thus help them advance through life.

Though the author confesses that he himself was not privileged to attend Oxford or Cambridge, he appeals to the first audience by admiring their collections of comic verse, the Oxford Sausage and the Cambridge Butter, and therefore signals that his verses are humorous and should not be judged by regular critical standards:

Yet deem not CAM, that ig’rance quite pervades

My brain, tho’never in thy halls refined;

Nor Isis, think thine academic shades,

Tho’out of sight, were always out of mind;

Thoughts of ye both, to neither tho’consigned, 5

Wou’d put my infant bosom in a flutter;

For oft my taste was seriously inclined,

With how much goût I’m half ashamed to utter,

To Oxford sausage rich; and curious Cambridge butter. (xiv)

The humorous magazines of Cambridge and Oxford provided Dibdin with the early training necessary to compose his own humorous verses, and as such to bridge the gap between high and low audiences. He provides a list of imaginary critical commentaries from such invented publications as “The Pedantic Exterminator” and “The Scalping Knife” to emphasize that his position as a “vociferous ballad singer” is not supposed to be taken seriously. But at the same time, he is careful to portray himself as highly educated, acknowledging his debt to no fewer than five authoritative histories. This claim to erudition also aids his appeal to the second audience, which needs assistance in receiving the correct history; he insists that “the dates of every incident occurring in the History, were correctly and progressively placed opposite the relation of them” (16). He proves his literary interest and expertise by his “miniature attempts to point out, by abridged examples, the progress of English Poetry,” which “necessarily cease at the period of Charles the Second’s Restoration, the Works of most Authors of that and subsequent periods being generally known.” Dibdin’s second audience, therefore, is a society that was beginning to believe in the value of English literature and the importance of English history, the “juvenile” mind that, increasingly toward the end of the century, required historical facts to be impressed upon it efficiently, naturally, and easily, by the pressures of the fledgling national school system. Though many of these texts were responses to the midcentury national obsession with history that Catherine Hall has noted,25 most of the late nineteenth-century histories described the necessity of memorizing facts for eventual examination.26

But if verses are meant to take the place of more difficult lessons, what does that imply for the study of metrical form itself ? These histories purvey a metrical language that is natural and simple, but also insidiously easy. George Raymond’s 1842 Chronicles of England: A Metrical History believed that “no fact in the world is better known than that metre, or rhythmical construction, is that form of language which is the first beloved of memory in its dawn, and the latest which attends it in its journey in decline” (viii). But Raymond warns that versified language, “[l]ike bearded grass . . . has crept up the sleeve of fancy, whence no power can dislodge it—it has attained its place with but little solicitation, and holds it with obstinacy—indeed, such is the nature of metrical language . . . no effort in acquisition; and almost appearing of spontaneous existence” (viii). With a gesture to Robert of Gloucester, Raymond recommended that his book be used as a study guide, not as a replacement “for such a study in its ampler and more venerable garb.” The student must first digest the “sober prose narration” and, “by means of this thread of rhyme,” “tie up the bulk of the weighty historic yarn, which laborious hands have wove, that the fibres may not unravel, and its continuity and purpose perish together” (xii).27 Like Dibdin’s hope that the varied metrical forms might provide an index to the various epochs in English history, Raymond wants the sameness of his verse form, a rather choppy pentameter that is held together mostly by its couplets, to connect the phases of England’s history to one another: “Thus Smithfield flames, as equal victims mix, / Both martyred Lutherans and Catholics. / Now sacrificed is Anna Boleyn’s life, / That Seymour may become the tyrant’s wife” (78) to the broader imperial history “[a]gainst the convoys of Columbian Spain, / The British projects terminate in vain; / But in a brighter expedition, foil / Her native efforts on Gibraltar’s soil” (195), and connect the student to the bounded whole. But the connective tissue of the poem’s meter doesn’t lodge itself into the student’s memory like a flowering plant—it is a weed, and it is an obstinate one. The verse form itself, then, emblematizes the history’s inevitable forward movement, and the rhyme’s chime at the end reminds the reader that it all, eventually, holds together. But the thread of rhyme is also the threat of rhyme; if rhyme is holding together the ample and venerable garb of prose narration, where the real history lies, then we also must take pains to not notice it, to have it work on us rather than have us work on it. The phases of England’s history and its progression must appear seamless just as the student citizen must be seamlessly absorbed into the larger nation—lest the nation’s continuity and purpose perish together. The measured verses in which Raymond delivers his history should help the student remember with little regard for his or her will. He ends his Chronicle with the hope that it will succeed in being “felt, own’d, and understood”:

Thus in our record we have nearly ran

Through half the era of the Christian span;

Attested kings and kingdoms in their range—

Dearth, in the proudest—in the happiest, change;

Have watched their rise, the progress, and the wane—

The “Imperial,” trodden—and th’ ”Eternal” vain:

Vain for that cause which still shall overthrow

Systems to come, as those already low;

Till it be felt, and own’d and understood,

The “Social Contract” is the Common Good. (270)

And so, too, is the kind of metrical contract that Raymond imagines, binding together his history in rhyme in the text of the long metrical history, while his more extensive prose notes populate the bottom of the manuscript.

And perhaps this insidious, spontaneous, obstinate metrical form might need an even more powerful method of securing its place in the student’s mind. Perhaps, as Rossendale writes in his 1846 History of the Kings and Queens of England in Verse: from King Egbert to Queen Victoria, the student might need “a kind of walking-stick for the memory; and if sung, (which may easily be managed) a musical one!”28 Rossendale describes his history as a series of invasions—from “Julius Caesar’s invasion, down to the period of the invasion of England by Railroads in the nineteenth century,” the “Roman yoke” and the railways both invading a more natural England, one that would require a walking stick. Like Collins’s song “Chapter of Kings,” Rossendale provides the musical score for Robert Burns’s “Auld Lang Syne,” whose original lyrics are, of course, all about remembering and forgetting:

About two thousand years ago,

Came Julius Caesar here;

And brought with him the Roman foe

With bright and glitt’ring spear

The natives that in England dwelt,

Were wild and cruel too;

And they—the pow’r of Druids felt, —

A tyrannizing crew.

These stanzas, and the book as a whole, are easily sung; and, like the lyrics of “Auld Lang Syne,” they adhere easily to the pattern of ballad meter. I imagine students sitting in public examinations and humming under their breath the entirety of English history as we might hum our ABCs. But whose ABCs are these? The familiar form of this popular schoolroom history was written by the Scottish National poet Robert Burns, who gets no mention here—he is forgotten, like the original words of “Auld Lang Syne”—just as the revised “Chapter of Kings” makes no mention of the Irish schoolmaster John Collins. The history of England and the shapes through which it is transmitted are composed and carved by writers from communities whose dialects complicate the dream of “standard” English, and whose imaginary “native” origins have been co-opted as England’s own.

The “metrical” in English metrical histories refers at various times to simple and pleasurable pedagogical methods, to artificial memory, to nation building, and to nature itself (as in the case of Raymond), and touches on issues of education, racial origins, national identification, and class. Following the Revised Code of 1861–62 and the examinations that these imposed on a new generation of schoolchildren, shorter metrical histories appeared so that they could be “learned completely by heart by any student of ordinary capacity,”29 as Montefiore’s 1876 The History of England in Verse promises. Catherine Robson usefully summarizes the implications of the Revised Code (and its “payment by results” scheme) on pedagogical methods: “[i]n consequence of the financial pressure [The Revised Code] exerted on over-extended educators, the code . . . plays a significant role in the history of memorization: because schools and teachers were subject to monetary penalties if their pupils did not satisfy visiting examiners, rote learning, particularly in reading, became the norm.”30 Though there was a revival in the artificial memory method around this time, with Lewis Carroll as a famous experimenter,31 mnemonic systems were largely outnumbered by the more approachable and teachable metrical histories in the late nineteenth century. One popular short version was called Granny’s History of England in Rhyme (1871), which began with a dedication that encapsulates the use of versification (as well as the generic shifts by late century between poetry and the novel) in many late Victorian classrooms: “A rhyme may glide into the mind / Like wedge into the oak, / Op’ning a broad, marked path for prose.”32 By 1896, educational theorists were assessing the success of versified histories. Charles Wesley Mann explained in “School Recreations and Amusements,” “without orderly arrangement in the mind, history becomes a chaos of heterogeneous and isolated facts. For this reason, various mnemonic jingles have been utilized as a means of fixing in the minds of pupils, in regular order, the names of dynasties and sovereigns.”33 What was “metrical” at midcentury changed, significantly, after the Revised Code: no longer “metrical,” these histories were now “in verse” or “in rhyme,” “versification” or “versifying,” as we shall see, replacing “meter” or “metrical” as the purely technical, non-poetic aspect of poem making. Just as poets, educators, and prosodists were defining and redefining “verse” and “poetry” in the late nineteenth century, so too were they defining and redefining, with a great deal of fervor, “meter,” “prosody,” and “versification.”

The history of English language and literature as a discipline is bound to the way that “history” was taught through these metrically mnemonic methodologies. English history, language study, and literary study all relied on the possibility that meter could help students remember—could be a signifier for—their role as subjects of the nation. “Meter” for the nation was orderly, regal, and signified a long line of battles won; “meter” for the growing middle class could be accessible and an easy to remember layperson’s tool—“meter” could also hint at a level of technicality that would only be perceptible to someone properly trained. ”Meter,” in the histories, was not referring to the shifting terms of cadence, accent, and tone discussed in grammar books and prosodic treatises. A popular concept of “meter” and “English national identity” emerged in these metrical histories: progressive, chronological, and tied to a glorious past of either classical or ancient English origin. “Meter” for these histories, except in the case of Dibdin, had more to do with memorization and rhythm than with what became known as the study of verse-measure. But despite the way that “verse” and “rhyme” began to replace “meter” as signifiers of mental and national order and accessible, even vernacular knowledge, “meter” as a term is still haunted by its simplification in the service of English history teaching. At the same time, there is, even within the discourse of memorization and rhythm, a hint of a more complicated knowledge—an erudite, elite knowledge of verse form to which these histories do not aspire, as if to approach the frightening study of verse form might alienate the student altogether and undermine the more important English history lesson. “English meter” is at once used in the service of a vernacular, popular tradition and also connected to higher learning, even if many of the histories go to great pains to avoid the judgment that they imagine an “actual” poem about history would attract.

A Grammatical History of England

In the same classrooms where history teaching was changing, the teaching of English grammar also shifted radically over the course of the nineteenth century. Though I focus on the period after the second reform bill in 1867, I want to turn for a moment to the one hundred preceding years to briefly outline the ways that the expansion of the franchise and the empire of English letters were intertwined. When, in 1833, the Factory Act limited child labor and prevented children under age nine from legally working, two hours of schooling became compulsory for all children up until the age of nine. This minimal educational standard followed on the heels of the Reform Bill of 1832, which extended the franchise to one in every five voters in England. Passed only with considerable controversy, the 1832 Bill resulted in insecurity about the prevalence of church-run schools as the sole basis of education among the newly empowered voting classes. Concurrent with the subsequent increase in grammar schools, Christopher Stray and Gillian Sutherland note that the first of two “surges” in book publishing began in 1830 and continued until roughly midcentury. Called the “distribution revolution,” and underpinned by the impact of the Fourtinier paper-making machine, steam-driven presses, case binding, and the progressive abolition of the taxes on knowledge, these market developments corresponded with the rise of formal schooling and the rise of public examinations in England. Formal schooling had begun to play a more central role in the socialization of children from the latter half of the eighteenth century. The expansion of the franchise in 1832 only accelerated the push toward national education. Stray and Sutherland note that “the sons of elite families and those whose parents had aspired to gentility were increasingly being sent to school,” and “the idea of a textbook in the modern sense of the word solidified around 1830.”34 The elocution handbooks of Enfield and Walker were just two examples of a number of new English schoolbooks that were printed and circulated informally in the scattershot early days of compulsory education. Education was conducted in various church schools (which mostly relied on the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer), hedge schools, charity schools, dame schools, grammar schools for the upper classes, and by schoolmasters and schoolmistresses in addition to the traditional “public” schools and each of these may have used different grammar books, standards, or anthologies. The English grammar book attempted to provide a unifying linguistic authority in the subject of the English language for a nation that had no centralized educational authority over its young subjects. Just as the school histories consolidated England’s past in the service of nation building, so too did the English grammar book attempt to consolidate English usage in order to organize an idea of the English empire of letters.35

“Meter,” as we have seen, carried connotations of national and mental order, hinting at a more technical and elite classical knowledge that might distract some students from the process of becoming proper English subjects through memorizing the historical facts of England’s origin. But what was this erudite, elite knowledge of English verse form, and where could the non–classically educated but still literate English person, looking to better him or herself, find out about it? Prosody, as a subset of the evolving field of “English grammar” at the turn of the nineteenth century, registered the broader expectations of “grammar” as a prescriptive, unchanging system of rules at the same time that it registered the resistance to these rules by approaching the study of versification differently from one grammar book to the next.36 The metrical discourses one finds in early grammar books are haunted by the same aspirations toward standard English pronunciation as the elocution manual, as well as the desire for a stable system of grammar based on the authority of Latin. However much English grammar books wanted to provide prescriptive rules, the “prosody” sections of these books heralded the advent of a more descriptive linguistic model. While providing external rules and conventional models for verse form, many grammar books also hinted at the inherent freedoms of English meter, so that English meter used what it wanted from the Latin model but also surpassed it.

Even before the critical events of the 1830s and 1860s expanded the franchise and slowly nationalized the education system, before the conception and execution of the New English Dictionary, the idea of “standards” for English usage was already influencing the study and understanding of English meter. Looking at the late eighteenth century and Victorian grammar books reveals the ways that the debates about accent, quantity, and the terms that make up verse study were simplified or abstracted for the sake of an imagined grammar student, a student whose need for a stable system of English prosody (as standardized pronunciation) and a stable explanation of English meter (as the representation of English literature’s parallel greatness to the classics) expanded with each expansion of the franchise.

In grammar books, “prosody” referred to both pronunciation and the study of English versification. Over the course of the nineteenth century, uncertainty about prosody and versification often mapped onto uncertainty about standards for pronunciation and ideas about poetic form. For both standardized pronunciation and poetic form, at stake was an appeal to a unified, broad national public as well as an appeal to the preservation of individuality and personal freedoms in dialect and metrical (or artistic) choice. While there seemed to be a move to standardize both English meter and English grammar, there was an equally strong desire to preserve the freedom of poetry to be individual—at once appealing to the collective but also intensely personal. Some of this uncertainty was evident in the construction of grammar books and the place of prosody, meter, and versification within them. Commonly, historical grammars were divided into four sections: orthography, etymology, syntax, and prosody (perhaps moving down the scale of most easily standardized to least). In many nineteenth-century grammars, “prosody” was further divided into “pronunciation, utterance, figures, and versification.” Doubly marginalized, “prosody” was the last part of the traditional grammar book, and “versification,” which literary scholars often (and some would argue confusedly37) equate with “prosody,” was the fourth and final definition of that word.38 The relegation of “prosody” to the end of grammar books from the late eighteenth century through the beginning of the nineteenth shows that, despite, or perhaps because of, the nervousness about standard pronunciation that accelerated toward the end of the century, the study of spelling, history, and ordering of words took precedence over their pronunciation. Or rather, “grammar books” were prescriptive, whereas the quite distinct guides to elocution and rhetoric were meant as aids to individual performance, and “prosody” bore traces of both of those fields, as well as the quite distinct model of the “poet’s handbook.”39 This tension between allowing or eliminating individuation in performance often lurked behind the prosody wars in the late nineteenth century, and is the root of our contemporary inability to decide whether meter is essentially a textual form or a guide to vocal performance.

Within the section “prosody,” the subsection “versification” is nearly an appendix, evidence of the way that versification, as a field, was either so simplified as to provide only the rudiments of verse form (and even these were different from book to book) or so technical that it required a treatise or manual all to itself.40 The uncertain and marginalized status of meter and versification in the study of grammar is an important reason why so many scholars of poetics found themselves with differing opinions on the matter—the simple fact is that the authors of grammar books not only did not know what to do with versification as a subsection of grammar, but that in attempting to find a way to turn the study of versification into a kind of grammar, and thus provide it with rules and standards, they presented the topic as if it were a discipline. Though prosody and versification appeared as an afterthought in these books and eventually disappeared entirely, the tensions and disagreements over their aims and uses were evident in the way that a single grammar book changed its approach to them over the course of the nineteenth century.41 In attempting to standardize and simplify the rules of English versification and meter, these grammar books prove the desire for a stable system at the same time that their constant revisions belie the instability of “prosody” as a subject. Could “prosody” at once provide a certain amount of discipline (like a grammar and within the grammar book), while at the same time reaching the status of a “grammar” with standards all its own?

The standardizing projects of the eighteenth century and the conservatism and classicism that we associate with the century in general do not apply neatly in the case of prosody. Jeff Strabone has recently outlined the way that Samuel Johnson’s standardizing project in The Dictionary (1755) was ambivalent about its own cultural-imperialist aims,42 and Paul Fussell has noted that Johnson’s own revisions to the fourth edition of The Dictionary (1773) added to the generalization, “every line considered by itself is more harmonious, as this rule is more strictly observed,” the warning, “[t]he variations necessary to pleasure belong to the art of poetry, not the rules of grammar.”43 As Strabone argues elsewhere, the national myths of England’s classical origins were being revised long before the study of language in England was crucially influenced by Danish and German philological study. Dialect poems, a renewed interest in ballads, and the collection of folk forms from rural Scotland competed with the standardization and Latinization of English language and grammar. Strabone suggests that Reliques of Ancient Poetry: Consisting of Old Heroic Ballads, Songs, and other Pieces of our earlier Poets44 contained a kind of metrical discourse that rivaled the standardizing impulses of the prescriptive grammars, especially in Percy’s long headnote, “On the Metre of Pierce Plowman’s Visions.”45 Part of a general interest in pre-Chaucerian meters as unifying, folk-meters of the people, Percy notes the division of Langland’s meter into lines of two parts, or “distichs” each, measured by alliteration. Percy writes, “the author of this poem will not be found to have invented any new mode of versification, as some have supposed, but only to have retained that of the old Saxon and Gothic poets.”46 A resurgent interest in “folk” forms, more purely “English” in some ways than the Latin forms imposed on English verse, both anticipated and was concurrent with the renewed interest in Anglo-Saxon at the turn of the nineteenth century.

In an 1835 review in The Gentleman’s Magazine of Rev. Samuel Fox’s King Alfred’s Anglo-Saxon Version of the Metres of Boethius, with an English translation and notes (translator of the poetical calendar of the Anglo-Saxons), the reviewer notes that “A taste for Anglo-Saxon literature is still increasing. The most unequivocal proof of this is, the constant demand for standard Anglo-Saxon books.”47 The reviewer notes “Mr. Fox properly states that ‘[i]t is now ascertained beyond all doubt that alliteration is the chief characteristic of Anglo-Saxon verse; and this is also accompanied with a rhythm which clearly distinguishes it from prose.’” The histories of England and the history of English meter are intertwined into one volume. England’s history is given a different kind of authority because it is not only about King Alfred but is actually written by him; the Reverend Samuel Fox has also translated the “poetical calendar” of the Anglo-Saxons and has clearly distinguished alliteration as the principle by which Anglo-Saxon meters are distinguished from prose. By 1807, Sharon Turner’s History of England: The History of Anglo-Saxons from the Earliest Period to the Norman Conquest, alludes to the already extant controversies over Anglo-Saxon meter and also foreshadows the ways that Anglo-Saxon “rhythm” would be revived institutionally at the turn of the twentieth century in the name of stable English national culture. Turner explains (quoting liberally from Bede):

The style of their poetry was as peculiar. It has been much disputed by what rules or laws the Saxons arranged their poetical phrases. I have observed a passage in the general works of Bede which may end the controversy, by showing that they used no rules at all, but adopted the simpler principle of consulting only the natural love of melody, of which the human organs of hearing have been made susceptible; and of using that easy allocation of syllables which pleased the musical ear. In defining rhythmus Bede says, “It is a modulated composition of words, not according to the laws of metre, but adapted in the number of its syllables to the judgment of the ear, as are the verses of our vulgar (or native) poets. Rhythm may exist without metre, but there cannot be metre without rhythm, which is thus more clearly defined. Metre is an artificial rule with modulation; rhythmus is the modulation without the rule. Yet, for the most part, you may find, by a sort of chance, some rule in rhythm; but this is not from an artificial government of syllables. It arises because the sound and the modulation lead to it. The vulgar poets effect this rustically; the skilful attain it by their skill.” From this passage it is obvious that Bede’s poetical countrymen wrote their vernacular verses without any other rule than that of pleasing the ear.48

The first thing to observe here is that the definition of Anglo-Saxon meter was already a controversy. The rules of even the most native rhythms were not easily definable, and despite attempts to turn “meter” into a grammar, scholars disagreed about the best way to read, teach, and analyze English meter. Though Turner concludes that “pleasing the ear” (Bede’s “musical” ear) was the only rule, the surge of interest in Anglo-Saxon poetry and grammar in the early nineteenth century meant that more readers would have been listening to and perhaps accustoming their own ears to the particular imagined sounds of Anglo-Saxon accentual-alliterative meters.49

Though the status of prosody in the grammar book seems far afield of our more traditional concept of poetics, it has, nonetheless, influenced how we think about the authority of English versification in the nineteenth century. The simplification of prosodic discourse and the limitation of complex discussions of prosodic controversies tended to collapse the concept of English prosody into its two most basic parts: an ordering system that had certain laws, and a system of English laws that are better than classical meter because they give the poet more freedom and are therefore proudly and identifiably English. Though most of the prominent English grammarians, or “New Rhetoricians”—Joseph Priestley, William Ward, Charles Coote, and Lindley Murray—adopt the Latin model for grammar, their disagreement about how to graphically represent accent anticipates broader disagreements in the nineteenth-century about scansion but also about the representation of sound in text. Priestley and Murray used the Latin macron ( ˉ ) and breve ( ˘ ), which correspond to the measure of quantities (the macron for a long vowel and the breve for a short), when they discuss versification. These signs would be familiar to students of Latin who would use them to translate into a metrical grid; they signified the imagined pronunciation of a dead language based on a system of rules of position. Murray, however, used the acute accent when discussing emphasis in pronunciation. He thus distinguished the vocal performance of English from its arrangement in the metrical grid and implied that accent was linked to pronunciation in English more than to a metrical system. Though the substitution of “accent” for “quantity” in English verse was not new, the move away from the older macron and breve does indicate that English meter, at least for Murray, would follow a more accentual model. Murray, Priestley, and Ward also characterized the metrical feet according to the classical names, and Murray went so far as to give the measures particular characters (on “trochaic” meter: “[t]his measure is defective in dignity, and can seldom be used on serious occasions”50). Though Thomas Sheridan was aware of the disagreements about the various models for English prosody and said as much in his Rhetorical Grammar (printed with the A Course of Lectures on Elocution in 1762 and the Dictionary in 1780),51 popular grammars nonetheless continued to print their various approaches to the measure of English verse, more or less modeled on Latin grammars, with an increasing emphasis on examples from English poetry as descriptive proof of their seemingly prescriptive models.

And as English versification became more descriptive it also, at times, departed from the Latin model and gestured to alternative histories. In 1788, Charles Coote introduced the “Anglo-Saxon” along with the “Old English” alphabet in his grammar (the “Old English” alphabet actually referring to a font style), which, significantly, contained “notes critical and etymological.” Coote’s grammar foreshadowed the inadequacy of the Latin model to account for English versification, even in a simplified grammar. In a subtle move away from classical meter, Coote used the acute accent to indicate stress rather than resorting to the classical macron and breve; pronunciation and not the classical rubric thus subtly appeared as the proper way to scan a line of English verse. Though Coote wrote, “a foot is a particular division of a line, consisting (in English verse) of two or three syllables,”52 he did not name those feet according to any Latin model but rather explained verse forms or “species of metre” by the placement of accent only. For instance, “[t]he heroic metre, so called from its being principally used in heroic poetry, is composed of lines of ten syllables, the accent being placed on the second, fourth, sixth, eighth, and tenth.” After describing “heroic metre,” “blank verse” (“destitute of rhyme”), “Alexandrine verse” (“usually used in heroic poetry intermixed with lines of ten syllables”), and “elegiac” (which could be “appropriate for elegies” but is also “a common metre for poems of a lighter cast”), Coote seems to throw up his hands at “lyric”: “[i]n lyric poetry, or that which comprehends odes, sonnets, songs, &c. various measures are adopted.” Though he goes on to name a few possibilities for rhyme schemes and accents, he ends his discussion by admitting “the measure of odes is so variable and irregular, that no determinate rules can be given for them.” Coote’s “Laws of Verse” only followed the Latin model by using the word “feet,” but he departed from the standard set forth by the other grammars in favor of attempting to describe English meters based on English poems themselves. There is a hint, here, with his inclusion of the Anglo-Saxon alphabet and his avoidance of the classical names for the metrical feet that Coote was leaning toward a potentially more autonomous possibility for English versification.

Though the emergent interest in Anglo-Saxon verse forms subtly influenced the versification sections of English grammar books, the authority of classical metrical feet remained prominent in standard grammars until the end of the nineteenth century. Despite the ascendancy of the classical model, however, the terms for prosody, meter, and versification were still unstable even in the most widely circulating and popular grammar textbooks. Lindley Murray’s best-selling English Grammar sold a staggering sixteen million copies in the United States and four million in Great Britain. William Woods asserts that it was Murray’s Grammar that “brought the eighteenth-century emphasis on correctness and rules into the nineteenth century and established it as the reigning tradition.”53 This was, perhaps, the case for the elements of grammar except prosody. In the case of the metrical aspects of prosody, Murray’s Grammar shows both how the poetics of prosody anticipates the descriptive model for grammar adopted later in the nineteenth century and how, despite the descriptive model, the specific terms we use for English meter are historically contingent.54 In 1795, the year of Murray’s first edition, “prosody” had two simple definitions: “the former teaches the true pronunciation of words, comprising accent, quantity, emphasis, and cadence, and the latter the laws of versification.”55 We can sense, already, how these two definitions are intertwined, for the laws of versification depend on the very definitions of accent, quantity, emphasis, and cadence. To give just one example of the volatility of “prosody,” in the 1810, 1828, and 1839 editions of Murray’s Grammar, pronunciation is comprised of “accent, quantity, emphasis, pause, and tone.”56 “Cadence” has been replaced by “pause” and “tone.” In elocutionary terms, emphasis meant raising the voice while cadence meant lowering the voice, but in the later editions the falling voice is replaced by “pause,” which has a spatial counterpart in the caesura, and “tone,” which is increasingly associated with affect. By 1867, the fifty-sixth edition of the Grammar, the editors erase “tone,” leaving only “pause.”57 As the science of linguistics was growing—indeed developing the science of phonetics—the perceived “problems” of pronunciation in prosody that may have required “tone” were, perhaps, no longer necessary.

The section “versification” that follows these revisions to “prosody” may, we might expect, shift away from performance, voice, and affect and, like “prosody” begin to sound more and more like a grammar with applicable and clear rules. And yet if the student must master the proper pronunciation of words (the former definition of prosody) before moving onto their measure (the latter definition, the laws), and if these rules of proper pronunciation are in flux, it follows that the “laws” of versification are also malleable. But though editors did revise the rules of versification from one edition to the next, they did not do so in order to reflect disagreements and dynamism; rather, the history of English versification in the grammar book is a history of repetition and reiteration—often without giving credit where credit is due. For instance, the non-abridged versions of Murray’s Grammar gave a detailed definition of “versification” that reads, in many ways, identically to contemporary accounts of English verse form. Yet Murray borrowed liberally from Thomas Sheridan’s popular eighteenth-century elocutionary manual, The Art of Reading (1775).58 Sheridan’s section, “Of Poetical Feet,” appeared first in the fourth edition (1798) of Murray’s grammar and bore the traces of turn-of-the-century elocutionary and prosodic discourse that was concerned with the rhetorical function of verse, specifically its performance. As if to anticipate a more advanced pupil’s question (“why do we call these line divisions ‘feet?’”), the text explains: “they are called feet because it is by their aid that the voice, as it were, steps along, through the verse, in a measured pace; and it is necessary that the syllables which mark this regular movement of the voice, should, in some manner, be distinguished from the others.”59

In a statement that could as easily refer to quantity (understood here as the length of time it takes to say a syllable) as accent (often understood in the grammars as emphasis), Sheridan’s definition in Murray’s popular grammar allowed the student to believe that by vocal right-reading, the “poetical feet” would distinguish themselves “in some manner.” Or, rather, the poetical feet would be distinguished on or in the syllables by either quantity or accent or both, and the voice would be able to “step along” toward a right reading.60 The voice, here, already displaced onto the feet, is not certain; only “in some manner,” not at all uniform, might the voice distinguish each syllable (a wobbly stone in a river), feeling shakily for the right way to get across the line. Rather than providing his own definition, Murray reprints Sheridan’s abstract definition, a practice I want to highlight as integral to the way that the idea of “English feet” (both in opposition to, and as a natural progression from, classical feet) circulates in the nineteenth century: that is, via the repetition and reprinting of formulations that stress instinct in performance, holding onto the shadow of elocution and projecting forward to Pound’s desire for a “natural rhythm.” The abstraction of “feet” in the English grammar book elided controversies over what went into their composition (accent, quantity, emphasis) and the particular interpretive problems that each of these issues presented.

In another example, Murray’s Grammar included Sheridan’s now familiar definition of English versification translated from Latin quantities into accents: “In English, syllables are divided into accented and unaccented; and the accented syllables being as strongly distinguished from the unaccented, by the peculiar stress of the voice upon them, are equally capable of marking the movement, and pointing out the regular paces of the voice, as the long syllables were, by their quantity, among the Romans.”61 Murray stops there, but Sheridan continues, complaining that “the whole modern theory of quantity will be found a mere chimera.”62 By leaving out what his predecessor knew, that the “theory” of quantity would obscure a student’s eventual understanding of accent, Murray gestures to the Roman genealogy of English verse as if to give it a high-cultural precedent, but does not reprint Sheridan’s warning that a deeper investigation into quantity would produce a “mere chimera.” In fact, Sheridan’s choice of words was incredibly apt for the study of English prosody more generally: the myth of the chimera involved, of course, a monster put together from various animal parts, much the same as late nineteenth-century prosodic historians would argue that English prosody was made up of various linguistic influences. Likewise, a chimera is a something hoped for and dreamed of, but seldom achieved. The hope for and dream of a stable system for English prosody, and the buried fear that it might not be achievable was, as I argue specifically in the following chapters, the engine that drove the study of prosody into a kind of obsolescence.

While Lindley Murray certainly helped popularize and circulate (though he did not originate) the idea that English poetic feet had both accent and quantity, he failed to define either. Versification must follow pronunciation both literally (students must get through accent, quantity, and emphasis in the basic pronunciation of words before they get to “versification” at the end) and metaphorically. The “quantity” of a syllable is defined simply as “the time which is occupied in pronouncing it.”63 Rather than admit that English speakers had no system for quantity, Murray made it seem as if what we did have was far better than what the ancients had. That is, he turned a complicated chimera into a statement of linguistic superiority: the English had “all that the ancients had, and something which they had not.”64 This additional component, Murray asserted, was that we had duplicate feet to match the ancient meters, but “with such a difference, as to fit them for different purposes, to be applied at our pleasure.” Our accent allowed English feet pleasure and freedom, as opposed to those fixed Greek and Latin feet. Further, Murray continued, “[e]very [English] foot has, from nature, powers peculiar to itself; and it is upon the knowledge and right application of these powers, that the pleasure and effect of numbers chiefly depend.” Whereas the terms “cadence,” “pause,” and “tone” are part of the debate, the problem of metrical feet in English concerns those three seemingly nonvariable terms of versification: “accent,” “quantity,” and “emphasis.” The terms themselves appear again and again but, as we can see in Sheridan and Murray, the ways that prosodists and poets defined and used these terms varied widely, and the various ways that English readers and poets understood these prosodic terms was what identified them as English. The English feet, then, to the average student coming across Murray’s best-selling grammar book, had authority from classical meters (not exactly defined, but there nonetheless). Mastery of the peculiar and particular powers of these “feet” would allow us to understand a more specialized kind of “English meter.” We can see how the obfuscating tendency of these constantly revised textbooks created the market for the definitive guide to English meter that emerged toward the end of the nineteenth century.

In addition to the revision and repetition of metrical terms, another of my concerns here is how certain ideas about prosodic form are stabilized by the contingencies of pedagogy. That is, the simplification, for pedagogical purposes, of the historical disagreements about certain aspects of English meter masks the ideologies of improvement within the Latin grammar and presents English meter as a self-evident truth. The self-evidence of English meter’s classical roots took on an even broader ideological meaning at the turn of the twentieth century, as we will see in chapter three. In one early example of what will be promoted as a metrical dogma toward the end of the century, we can see even Murray’s abridged grammar efface and simplify the complex history of English meter. When Murray’s grammar was abridged, as it often was, the “versification” section of “prosody” states the following: “versification is the arrangement of a certain number and variety of syllables, according to certain laws.”65 There was no reference to problematic accent, quantity, or emphasis here; versification was simply “arrangement” according to law. This was from an 1816 edition, intended for a “younger class of learners” who should be protected from the more technical aspects of English versification, a pedagogical impulse that would take root in the late nineteenth century.66 The “certain laws” of versification and meter are English laws, which should be justification enough for following them.