Chapter 16

Great Grooves

IN THIS CHAPTER

Mastering accompaniment patterns for your left hand

Mastering accompaniment patterns for your left hand

Finding new ways to begin and end a masterpiece

Finding new ways to begin and end a masterpiece

Want to make even a simple song like “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” into a showstopper? This is the chapter for you. I help you apply a handful of tricks and techniques to just about any song you encounter in your piano career. Whether it’s an attention-grabbing intro or finale, a cool accompaniment pattern, or just a nice little riff thrown in, the tricks in this chapter help you to spice up your music.

If after you read this chapter you feel like you need even more playing tools and tips, Chapter 17 tells you how to play songs in different styles, including classical, rock, blues, and jazz.

Great Left-Hand Accompaniment Patterns

One of the most important tools for your bag of tricks is a good supply of left-hand accompaniment patterns. Any time you’re faced with playing straight chords or even playing melodies from a fake book, you’re left to your own resources to supply an interesting-sounding bass line. (See Chapter 19 for more on fake books.)

Fret not — I’m here to help. This section gives you excellent and professional-sounding left-hand patterns that you can apply to just about any song you come across. Each of these patterns is versatile — applicable to both 3/4 and 4/4 meters — not to mention user-friendly.

Fixed and broken chords

A chord-based approach, whether played straight or with arpeggios, serves as an excellent introduction to left-hand accompaniment. (Turn to Chapter 14 for more on chords and arpeggios.)

Start with the basic chords and find inversions that work well for you without requiring your left hand to move all over the keyboard. (Chapter 14 tells you all about inversions.) Also experiment with various rhythmic patterns. For example, try playing quarter-note chords instead of whole-note chords. Or try a dotted quarter- and eighth-note pattern.

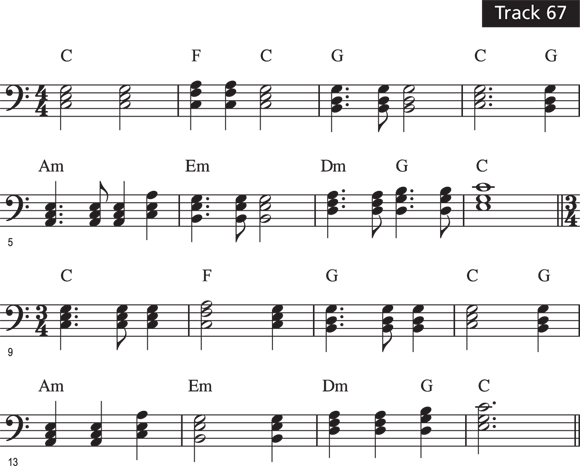

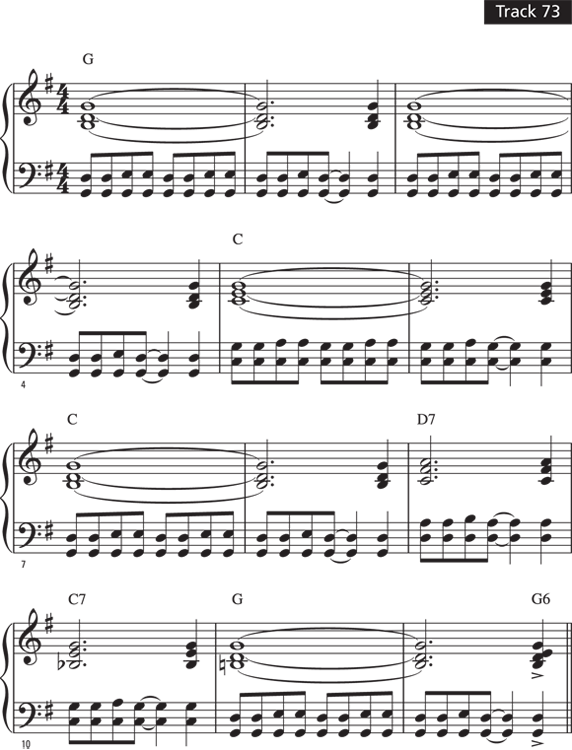

In Figure 16-1, the left hand plays a simple chord progression with several different rhythmic patterns. Run through these a few times and decide which rhythmic pattern works, sounds, and feels best to you.

FIGURE 16-1: Left-hand chords in varied rhythm patterns.

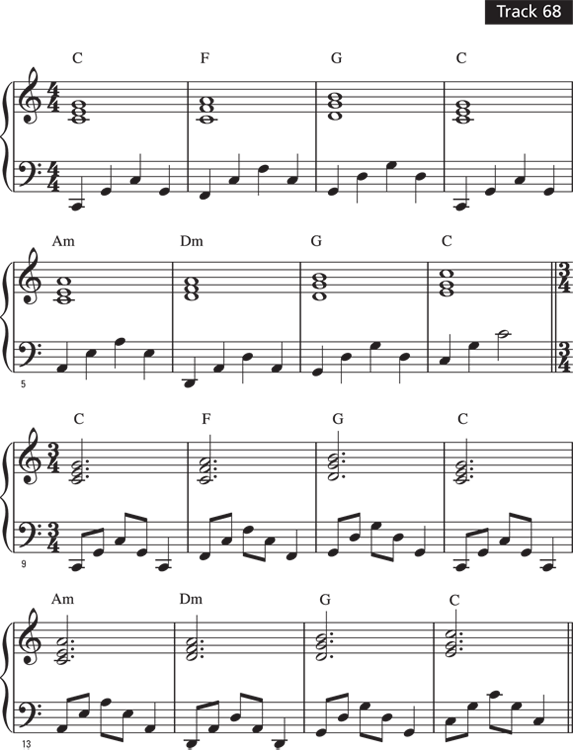

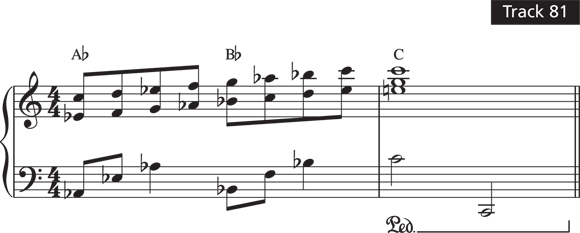

You can change the texture and add some variety with a constant arpeggiated pattern in the left hand. For every chord symbol in Figure 16-2, use the root, fifth, and octave notes of the chord’s scale to form an up-and-down pattern throughout the song. This pattern works for fast or slow songs.

FIGURE 16-2: Root-fifth-octave patterns are easy to play and sound great.

Chord picking

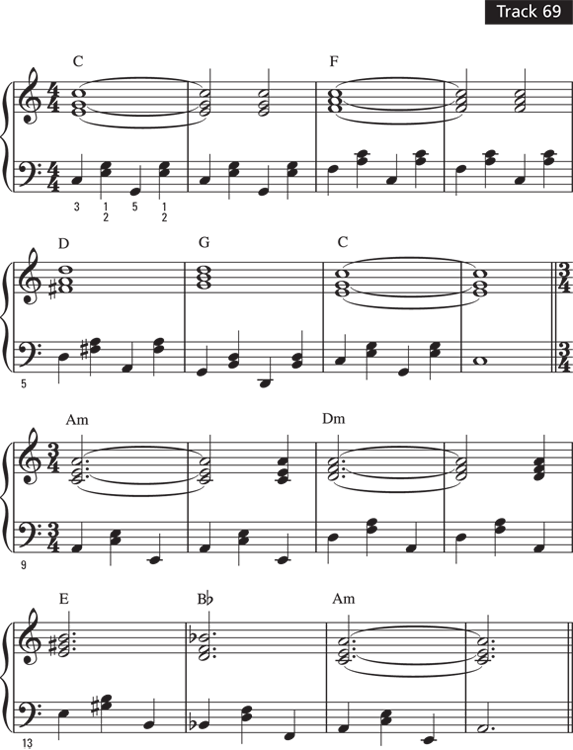

Left-hand chord picking is a style best suited to country music (which you can read more about in Chapter 17). But even if you aren’t a fan of that genre, you can apply this pattern to just about any song you like.

Chapter 14 tells you that most chords are made up of a root, a third, and a fifth. You need to know these three elements to be a successful chord-picker.

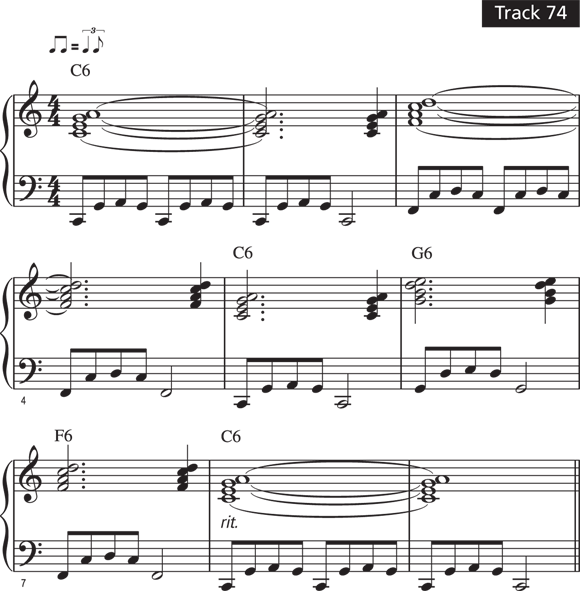

FIGURE 16-3: Practice chord picking with four different chords.

Now try playing this pattern in the piece “Picking and Grinning” (see Figure 16-4). After you get the feel of this bouncy rhythmic pattern, you won’t even need to look at your hands. Your pinky will find the two alternating bass notes because they’re always the same distance from the root note.

Octave hammering

This easy (if tiring) left-handed groove is really fun and easy if your right hand is just playing chords. But if you’re playing a melody or something more complicated than chords with your right hand, this pattern may not be a practical choice.

To hammer out some octaves, you simply prepare your left hand in an open octave position, with your pinky and thumb ready on the two notes, and make sure your wrist is loose enough to bounce a bit with the appropriate rhythm. When the chord changes, keep your hand in octave position as you move directly to the next set of octaves. You can play the octaves using any rhythm that sounds good to you — try whole notes, half notes, even eighth notes, depending on the rhythmic character of the song.

FIGURE 16-4: Left-hand chord picking in “Picking and Grinning.”

“Octaves in the Left” (see Figure 16-5) lets you roll out some octaves.

As you become more familiar with harmony, you can add to these left-hand octave patterns with octaves built on the notes of the chord. For example, the octaves in “Jumping Octaves” (see Figure 16-6) move from the root note to the third interval note to the fifth interval note for each right-hand chord.

FIGURE 16-5: Hammer out octaves in “Octaves in the Left.”

Bouncy rock patterns

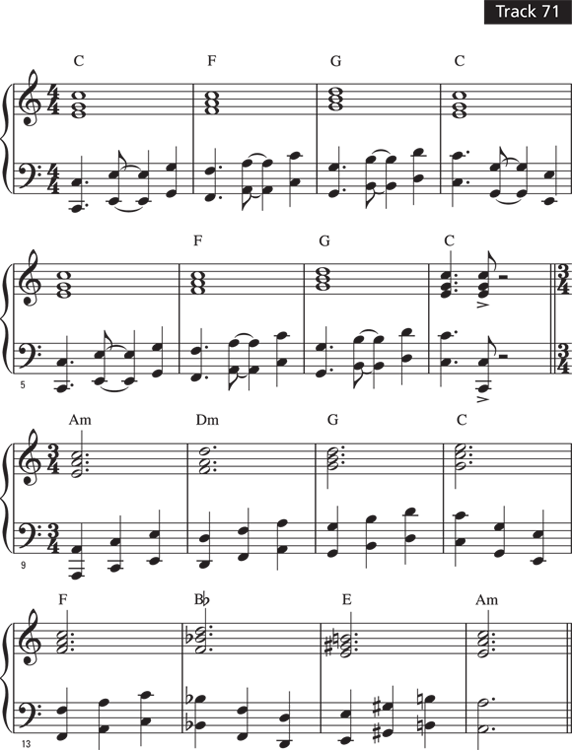

In addition to slamming octaves, a nice rock ’n’ roll-sounding bass pattern may use other intervals drawn from scale notes. (Chapter 12 explains intervals in great detail.)

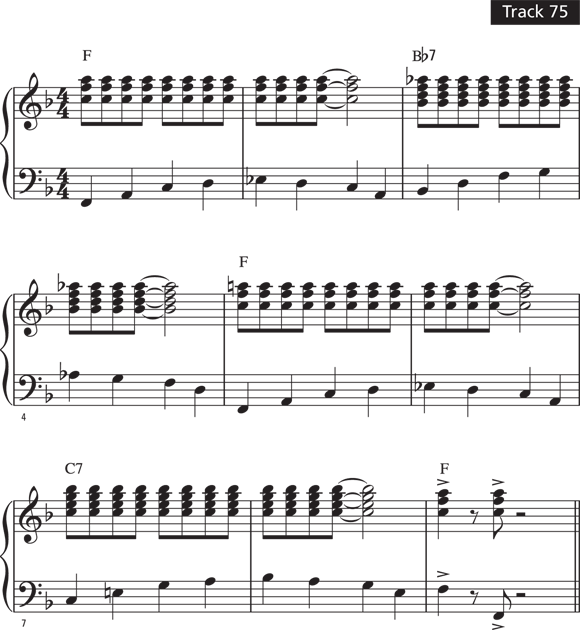

You can create a great bass pattern using the octave, fifth, and sixth of each chord. Try this high-energy accompaniment along with “Rockin’ Intervals” (see Figure 16-7). You can modify the pattern to fit a two- or one-measure pattern in 4/4 meter. After a few times through, your hands will know what to do, and you can apply the pattern to any major chord.

FIGURE 16-6: Build octaves on different chord notes in “Jumping Octaves.”

FIGURE 16-7: A driving left-hand pattern with the octave, fifth, and sixth intervals in “Rockin’ Intervals.”

The great Chuck Berry made the locomotive-sounding pattern demonstrated in “Berry-Style Blues” (see Figure 16-8) very popular on the guitar. It was only a matter of time before some trailblazing pianist adapted this guitar pattern to the piano. All you have to do is alternate between playing an open fifth and an open sixth on every beat.

FIGURE 16-8: Open intervals that chug along in “Berry-Style Blues.”

Melodic bass lines

Some left-hand patterns are so widely used that they’re better known than the melodies they accompany. “Bum-ba-di-da” (see Figure 16-9) is one such pattern that was made famous by Roy Rogers in his show-closing song “Happy Trails.” All you need are three notes from each chord’s scale: the root, fifth, and sixth. Play them back and forth, over and over.

FIGURE 16-9: Mosey along with the bum-ba-di-da bass pattern.

Another melodic left-hand pattern played by every pianist from novice to pro is the “boogie-woogie” bass line. It doesn’t even need a melody. This bass line uses notes from a major scale but lowers the seventh note of the scale a half-step (also called a flatted seventh) to give you that bluesy sound.

For each new chord in the boogie-woogie bass line (see Figure 16-10), you play the following scale notes up the keys and then back down: root, third, fifth, sixth, flatted seventh.

FIGURE 16-10: A boogie-woogie pattern that never goes out of style.

Applying Great Intros and Finales

A good pianist should always be able to begin and end a piece in an interesting way. You can join the ranks by filing away some stock intros and finales (sometimes called outros) you can apply to any piece of music at any given time. An intro or finale is your time to shine, so milk it for all it’s worth.

Few things are more fun than playing a great intro or finale. Heck, some of them sound great alone, without a song attached.

You can add the intros and finales in this section to virtually any piece of music. Just follow these steps:

-

Check the song’s style.

Each intro and finale has a different style or sound. Consider the style of the song you’re playing and choose an intro that works best with it. For example, a rock ’n’ roll intro may not sound very good attached to a soft country ballad. But, then again, anything’s possible in music. (Chapter 17 guides you through many musical styles.)

-

Check the song’s key.

All the intros and finales you find in this book are written in the key of C. If the song you want to play is also in the key of C, you’re ready to go. If not, adjust the notes and chords of the intro and finale you choose to correspond with the song’s key by using the helpful hints shown with each intro and finale.

-

Check the song’s first chord.

All the intros transition easily into the first chords or notes of a song, provided that the song begins with a chord built on the first tone of the scale. (Chapter 14 explains these types of chords.) For example, if the song you’re playing is in the key of C and begins with a C major chord, any of the intros here work perfectly because they’re written in the key of C. If your song starts with a different chord, use the hints provided with each intro to adjust the chord accordingly.

-

Check the song’s last chord.

Like intros, you can tack all these finales onto the end of a song if the song ends with a chord built on the first tone of the scale (and most songs do). For example, if the song you’re playing is in the key of C and ends with a C major chord, you’ll have no problem with one of these finales because they’re written in the key of C. If your song ends with a different chord, you need to adjust the finale to the appropriate key.

The big entrance

When a singer needs a good intro, you need to be able to bring it. The audience has a tendency to talk between songs, so it’s your job to shut ’em up and announce the start of the new song. Playing a few bars of show-stopping, original material really gets things hopping and leaves them begging for more.

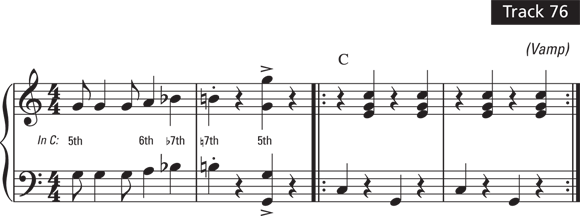

The “Get Ready, Here We Go” intro

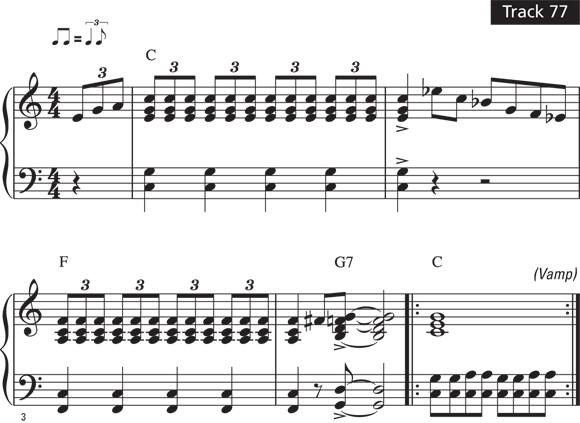

The intro you see in Figure 16-11 is bound to grab the audience’s attention. It has been used in just about every style of music, from vaudeville to ragtime to Broadway. Hear it once and you’ll never forget it. Play it and you’ll be hooked. Just keep repeating the measures between the repeat signs, or vamp, until you’re ready to start the melody. (Chapter 6 talks about repeat signs and what they do.)

FIGURE 16-11: Intro #1.

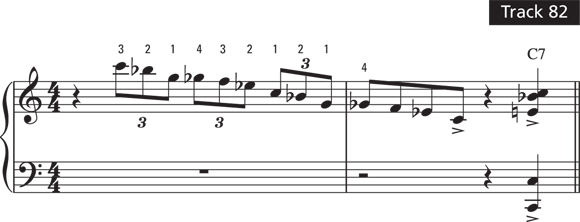

The “Rockin’ Jam” intro

You can knock some socks off with a rock ’n’ roll intro like the one in Figure 16-12. The triplets are tricky, but you can play this one fast or slow. A slower-tempo version works well with a blues song, and a fast version is good for … well, a fast rockin’ song. This intro also contains grace notes, which you can read about in Chapter 15.

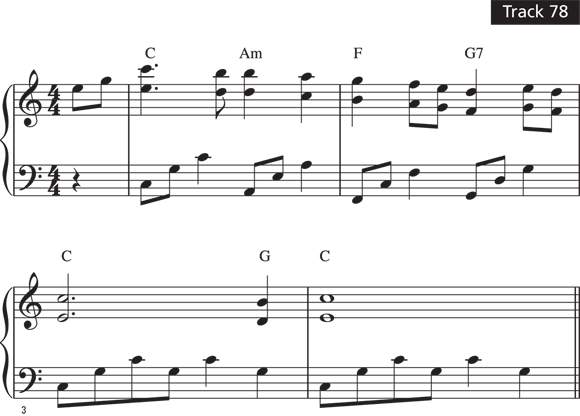

The “Sweet Ballad” intro

When a slow ballad is next on the set list, the intro in Figure 16-13 works well. The left-hand part sets up a root-fifth-octave pattern introduced in the earlier section “Fixed and broken chords.” The right-hand part makes use of parallel sixths, moving sweetly down the scale.

FIGURE 16-12: Intro #2.

FIGURE 16-13: Intro #3.

The “Killing Time” intro

Sometimes you need to repeat an intro over and over. Perhaps you’ve forgotten the melody. Perhaps you’re waiting for divine inspiration. Or maybe you’re waiting for the singer to decide to join you. Whatever the case, you can easily repeat an intro like the one in Figure 16-14 until the time comes to move on. Simply play the first four measures over and over until you’re finally ready. You’re simply vamping on a G7 chord, which leads you (and the preoccupied singer) into the key of C when you’re both ready.

FIGURE 16-14: Intro #4.

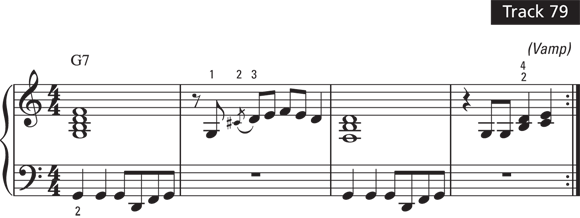

The “Saloon Salutations” intro

When you’re just tinkering around in a piano lounge, perhaps all you need is a few bars of honky-tonk style piano, like the ones in Figure 16-15. Notice how effective the grace notes (measure 1) and tremolos (measure 2) are in this intro. (Chapter 15 tells you more about grace notes and tremolos.)

Exit, stage left

The band is building up to the final chord, and it’s time for the big finish. The singer belts the last lyric, and it’s up to you to drop the curtain. Quick! Grab a handful of these finales and you’re sure to receive an encore request.

The “I Loved You, You Left Me” finale

The finale shown in Figure 16-16 is a simple but effective ending, perhaps even a tear-jerker when played with the right emotion. You certainly wouldn’t want to use this as an end to a rocking song like “Burning Down the House,” but it fits nicely with any major-key ballad (like the one you introduced with Intro #3 in Figure 16-13).

FIGURE 16-15: Intro #5.

FIGURE 16-16: Finale #1.

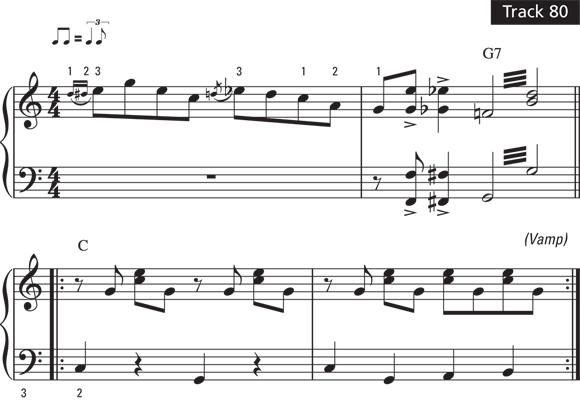

The “Let’s Load Up the Bus” finale

After a classic rock hand-jam, something like the finale in Figure 16-17 finishes the song with the appropriate amount of flair. The triplets take you down the C blues scale. They should be played as smoothly as possible, so feel free to slow down the tempo until you conquer the correct fingering. And make sure to really punch that last chord! (Chapter 8 gives you tips on playing the triplets you find in this finale, and Chapter 10 has more on blues scales.)

FIGURE 16-17: Finale #2.

The “Last Call” finale

The triplets in the finale of Figure 16-18 give this closer a distinctive feel that works best with a blues or jazz piece. It has the sound of winding down to a halt.

FIGURE 16-18: Finale #3.

In this finale, you play the notes of chords C, Cdim., Dm7, and C again. You can easily transpose and attach this finale to a song in any key by applying the correct chord types and breaking them up. For example, in the key of G, the chords are G, Gdim., Am7, and G. (Chapter 14 explains how to build chords.)

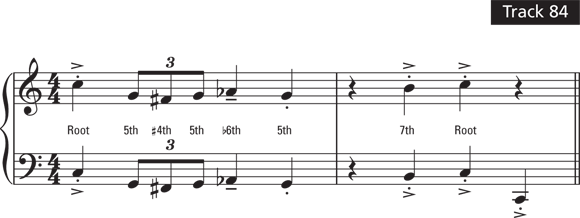

The “Shave and a Haircut” finale

Everyone knows it. Everyone loves it. I’m talking about the ever-famous “Shave and a Haircut” closer. Figure 16-19 shows you this all-time classic in all its glory. You can play this finale with unison octaves, so the name of each scale note is indicated in the middle of the grand staff. With this information, you can have a shave and a haircut in the key of your choice.

FIGURE 16-19: Finale #4.

Playing Songs with Left-Hand Grooves

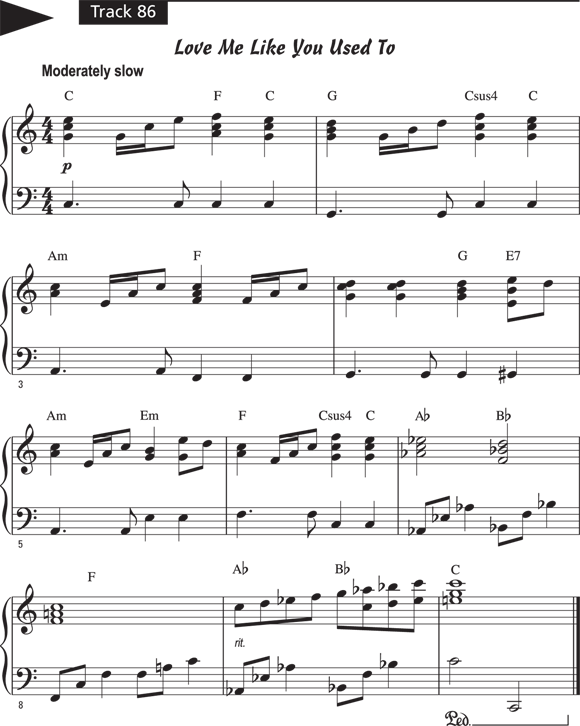

The songs in this section put together the techniques introduced in this chapter: left-hand accompaniment patterns and intros and finales. You can enjoy the songs on their own and also use them as examples of how to apply these tools to your own songs.

- “Country Riffin’”: This little ditty is easy on the fingers but even easier on the ears. The bum-ba-di-da bass line sets the groove and the “Last Call” finale brings the song home. With a sauntering feel that will lighten the mood, it’s sure to be a crowd-pleaser.

- “Love Me Like You Used To”: This song combines a left-hand accompaniment pattern from earlier in this chapter with an intro and finale. The left-hand part sets the root-fifth-octave arpeggiated pattern to a slow-tempo groove that supports the entire song.

Practicing these patterns again and again is important to master the right notes and the way each pattern feels under your fingers. After a while, though, you can ignore the printed music and just try to feel the pattern: the distance between the intervals, the shape of the chord, the rhythm, and so on. The more comfortable you are with the pattern, the more easily you can apply it to any key, any chord, and any scale.

Practicing these patterns again and again is important to master the right notes and the way each pattern feels under your fingers. After a while, though, you can ignore the printed music and just try to feel the pattern: the distance between the intervals, the shape of the chord, the rhythm, and so on. The more comfortable you are with the pattern, the more easily you can apply it to any key, any chord, and any scale. To play a song using the left-hand accompaniment in

To play a song using the left-hand accompaniment in  To check out a good sampling of these great grooves, watch Video Clip 24 at

To check out a good sampling of these great grooves, watch Video Clip 24 at  Most of the intros and finales in this section are geared toward popular music. When it comes to classical music, the composer usually gives you an appropriate beginning and ending. Of course, if you really want to fire up Chopin’s Minute Waltz, you can always add one of these intros.

Most of the intros and finales in this section are geared toward popular music. When it comes to classical music, the composer usually gives you an appropriate beginning and ending. Of course, if you really want to fire up Chopin’s Minute Waltz, you can always add one of these intros.