ORGANIZATIONS FIND MANY ways to be ordinary. Despite the incessant rhetoric of attracting and retaining the best, organizations often stuff their offices with mediocre performers. The reason is simple. The decisions of these organizations regarding hiring, pay, promotions, and retention are based on factors other than merit: factors that intrude on skill-based considerations, such as friendship ties, tenure, favoritism, politics, and discrimination. The people who would be best at doing the work are not the ones doing it. The consequences to organizations are obvious.

In this chapter, we explore the prerequisite of merit in creating high-performance organizations. Although the concept of merit is straightforward, we discuss the several ways that companies subvert its use and impair organizations’ long-term health. Conversely, we discuss ways to ensure that merit-based decisions are appropriately made and applied.

Merit presumes that decisions regarding the way rewards are distributed are grounded on abilities and contributions. The idea that people who contribute more should get more in return relative to others is a principle that children as young as thirty-six months grasp. For example, preschoolers who observe two people baking cookies divide the spoils according to the amount of work each performs.1 In fact, most social mammals have a keen sense of distributive fairness. Capuchin monkeys that feel cheated through an unfair distribution of rewards will refuse to continue with an experimental task or will throw their miserly reward at the experimenter in protest.2 Humans behave similarly. In ultimatum games in which one player recommends a distribution of rewards that another player can accept or reject, players tend to reject unfair offers even though that player receives nothing as a result and is worse off for it (the distributing player also suffers a loss in ultimatum games; however, players will still reject offers even if the allocator is unaffected by the decision, albeit rejection occurs to a lesser degree).3 Therefore, clearly fairness entails more than pure, rational economics.

Fairness is culturally ubiquitous, and theorists believe that it is evolutionarily rooted in social societies to promote cooperation. When something seems unfair, our brains send us emotional signals to inform us that something is amiss that must be rectified. Thus, feelings of injustice serve as warnings that the quality of our relationships are endangered and that some form of remedial action is required.

Justice can be restored in several ways, some of which mend relationships and some which irrevocably sours them. If a person feels slighted, the most straightforward repair is for the person to point out the iniquity in the hope of eliciting due compensation or an acceptable apology. If the injustice persists and an individual believes they are under-rewarded, they may take several actions—none of which is particularly good for organizations. First, they may lower the time and effort they devote to their job or reduce their collegiality and helpfulness toward others as a way to realign their contributions to the perceived rewards they receive. Second, if the organization through the actions of management is viewed as the begetter of injustice, then an employee may get even with the organization through theft, sabotage, reputational damage, or other retributive actions designed to lower the outcomes of the institution. For example, a disgruntled employee at Tesla in information technology recently altered the code used in the Tesla Manufacturing Operating System, causing extensive damage.4 This employee is a modern-age variant of a long line of production saboteurs that include luddites (who broke knitting frames) and chartists (who pulled plugs on steam engines that fueled factories). And, third, the employee can terminate the relationship by exiting the organization with the associated cost of replacement estimated to be approximately the same as the departing employee’s annual salary.

When executed well, merit-based pay for performance plans increase job satisfaction and motivate action.5 Indeed, contingent pay is part of a complex of practices that together form high-performance work systems. These systems are made up of rigorous recruitment and selection procedures, liberal allowances for training and development, employee participation and decentralized decision-making, flexible work arrangements, performance management programs, and pay for performance and incentive compensation plans. High-performance work practices collectively affect organizational performance by enhancing the capabilities of the workforce, increasing commitment to the organization, empowering and motivating employees, and promoting cross-functional relationships and information sharing. These composite programs have been reliably associated with higher productivity, profitability, growth, innovation, and service.6

The effects of the incentivizing elements of rewards are well known and codified as The Law of Effect: people will enact behaviors for which they anticipate a valued reward and will continue to exhibit those behaviors for as long as the reward is expected. The figurative carrot, however, is not universally appealing or effective. In practice, the link between reward and performance is not straightforward. The association is complicated by the many different kinds of rewards, different kinds of performances, and different kinds of motivational states, and these interact in countless ways.

Given the volumes written on the topic of why people do what they do, this chapter will not settle the matter of motivation. Indeed, just about anything declarative about motivation will be controversial. Even the seminal, often-cited thesis of Frederick Hertzberg, which today seems tame, created a stir following the 1959 publication of The Motivation to Work. Hertzberg claimed that motivators fall into two classes that he referred to as hygiene factors and motivating factors. The latter roughly describes intrinsically appealing aspects of tasks, such as feelings of achievement. The former identifies external or extrinsic factors, such as money, that, if amply provided, eliminate dissatisfaction but do not substantively contribute to satisfaction. At the time of his thesis, the claim that extrinsic motivators are not as potent to satisfaction as intrinsic factors was viewed skeptically. Since then, however, we can say that Hertzberg’s claims mostly have been supported.

This is not to say that money or other extrinsic factors are unimportant to our satisfaction and welfare. Money affords greater freedom from the mundane; more choices and options; resources that can be deployed to reduce stress or enhance convenience; a sense of security, autonomy, and control; and acquisition of goods that can be applied to meeting personal needs and goals. Given the advantages of income and wealth, it is not surprising that money positively relates to better mental and physical health, and negatively relates to mortality. As Abraham Maslow sagely asserted, money is one of those substances that accommodates basic needs and liberates people to pursue other more fulfilling concerns.7

Debate rages about exactly what those concerns are, but we believe that academic psychologist Carol Ryff has it about right in her articulation of universal needs.8 Ryff originally developed her ideas of well-being—what people need to flourish—by synthesizing accounts of quality of life from philosophy, the humanities, and social sciences. The set of needs she proposes substantially overlaps with, or subsumes, those laid out in other need theories.9 We are confident, therefore, that her list covers needs that generally are agreed on as essential for individuals’ happiness and personal welfare. Additionally, we see no reason why the psychology of different age cohorts (i.e., generations) would differ on Ryff’s proposed conceptualization of needs. People want the same basic things, which does not change with a person’s date of birth. But the weighting of motivations may change with age and experience may inform how personal needs can best be fulfilled.10 For example, millennials seem to think that starting one’s own business may be the best route to autonomy and purpose.11

The results of Ryff’s work yield six needs:

• Positive relations/belonging: Has warm, pleasurable, and trusting relationships with others; feels connected and accepted by others

• Purpose in life/meaning: Believes that one has important aims in life and a clear sense of direction

• Autonomy: Freely acts according to one’s standards, values, and beliefs

• Self-acceptance: Holds a positive evaluation of oneself, accepting of who one is inclusive of strengths and imperfections

• Environmental mastery/confidence: Competently manages one’s life, maintaining personal composure, control, and efficacy in problematic and emotion-infused situations

• Personal growth: Progressively develops expertise and continuously advances toward personal potential

This list highlights rewards that come from within, or that are intrinsic to the person and the activity in which they are engaged. Most people are well-versed on the distinction between external and internal rewards as reasons for action. With external rewards, the locus for behavior is external reward, such as pay. With internal rewards, the activity serves as its own reinforcer. The behavior is repeated because people enjoy engaging in the activity, thereby deriving their own pleasure in the doing. The challenge, purpose, novelty, and engagement of the work provide the rationale for doing the work. Thus, one of the easiest ways to motivate employees is to help them find their calling.

On one hand, people clearly do things because of the extrinsic, or external, rewards they will receive as a result. On the other hand, people also derive pleasure from the actual work they do. These two forms of motivation—extrinsic and intrinsic—interact. For example, research shows that the promise of reward in exchange for performing behaviors that people enjoy diminishes the satisfaction a person takes in that behavior and the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated in the absence of the reward. The seminal studies in this area were conducted with children and replicated on adult populations. For example, Lepper and Greene showed that children who were told that they would be monitored and receive a reward following an activity showed less interest in the activity two weeks later.12 Rewarding activities that people enjoy crowds out the pleasure they derive from the activity by controlling its performance and making the completion of the task the justification for doing it.13 This undermining effect is particularly pronounced when the incentives to act are direct, proximal, and salient: when, in the vernacular of business, employees have a clear line of sight.

Box 10.1 describes a typical case in which an organization ties pay to performance, and it illustrates some of the complexities surrounding pay for performance plans.14 The case shows that express contingencies between pay and performance increase quantitative outcomes, such as productivity. Thus, the company saw increases in tonnage output as a result of the financial incentives it had put in place. The case also shows that quality outcomes decreased, which is consistent with a recent meta-analyses that shows that the effects of financial incentives on task performance is weaker for quality than quantity.15 Quality and creativity tend to be regulated by the inherent interest people have in the work—or by the work’s intrinsic properties. The more pleasurable the work, the higher the quality and creativity of employees.16

Box 10.1 Pay for Performance in a German Steel Company

A German Steel company is a major producer of sheet metal for the auto and beverage industries that employs 2,500 people. The company’s fortunes declined in the 1980s because of errant mergers, new foreign competition, and the privatization of former state-owned enterprises. It experienced its first loss in 1993. Through a secession of remedial actions, however, it was able to correct course and return to profitability. A few of these corrective measures were the establishment of semi-autonomous work teams; an increase in pay 15–20 percent above the market for the metals industry to attract workers to, and retain them within, a rural location; and introduction of a monthly team incentive plan (for twenty-five production teams) based on production unit output. Investigators examined the effects of the plan over a ten-year period in conjunction with the team structure. They found that the incentive increased production by 3.4 percent. These benefits, however, were erased by decreases in quality (scrap waste) and increases in machine down times (the latter occurred because people ran the machines for longer periods without stopping them for scheduled maintenance).

Although it is uncertain if the steel company could improve quantity and quality at the same time, if possible, they could have offered incentives for quality improvements. Research indicates that quality and creativity can be enhanced when specifically set as goals.17 In these instances, the reward directs people’s attention to the intrinsically satisfying aspects of the work: to the challenge of coming up with new ideas or finding better ways of doing things. The financial reward becomes a secondary add-on benefit: the proverbial icing on the cake.

In addition to its direct influence on performance, contingent pay has another, less appreciated, effect on organizational performance through sorting effects. Sorting effects occur when appropriately rewarded high performers stay with organizations and lesser rewarded poor performers self-select out.18 The changing complexion of the workforce induced by successful merit programs can be substantial, with notable results. For example, in one study, researchers looked at productivity gains in an automobile glass installation company before and after pay was more closely connected to productivity. About half of the gains were attributable to the incentive properties of the new pay system. Another half, however, were attributable to changes in the configuration of the workforce as less productive employees dropped out and were replaced by more productive employees.19 Therefore, merit pay programs often serve as filters that strain low performers from the system. Although turnover is inversely related to organizational performance—the higher the turnover, the lower the organizational performance—this association depends not only on the magnitude of departures but also on who is coming and going as well.

Clearly, the complexion of the workforce affects organizational performance. We recently saw a question posted on LinkedIn in which the inquirer asked for ways to hire the best people. Had we responded, we would have said that to attract and hire the best talent, a company should already have the best and should actively promote that fact. There is truth to the old saw that the people make the place. It simply is easier to recruit people into groups that have reputations for excellence. High performers are more likely to want to join and remain with companies with other high performers who can make them better and more successful through the instrumental and social support they receive.20

Joining talent-rich organizations makes a difference. A study of sell-side security analysts in investment banks found that independent rankings of these analysts were higher when they were surrounded by similarly high-ranking analysts and better performing colleagues in related departments.21 The same results occur in the arts and sports. For example, actors who are surrounded by a better cast and production crew are more likely to be recognized for their roles.22 High-quality teams not only aid the best on the group. The analysts who benefited the most from high-performing coworkers were those who were recognized for their excellence but not at the top of the rankings.

Indeed, it is common in teams that the top members will lift the performances of good, but less capable, members. In a simple example using motor persistence, Otto Kohler showed that collective performances can exceed the sum of what people can do individually (i.e., the Kohler effect). He asked individuals to hold a bar out in front of them for as long as possible. Those same people were then asked to repeat the task, but this time in a group and with their arms stretched out over a rope so that when the arm of any individual gave out and hit the rope, a timer was stopped and the performance for the group was recorded. (This is a conjunctive task in which the group’s performance is as good as the worst performer.) The greatest increases in times occurred with individuals who had the lowest individual results.23 The Kohler effect is readily seen in naturalistic settings. In relay races, for example, inferior swimmers record faster times than they do in individual contests.24 The times of the slowest swimmers when measured individually increase in the group setting.

Extrapolating to working groups, we can see several possible reasons for this effect and the principles that leaders may want to keep in mind when managing teams. First, people are interdependent in that they share a common goal. Second, each member is indispensable to goal success. Third, every member has a vested interest in each other’s success and they are depending on each other to do their best. Fourth, the observation of others performing well stimulates upward comparisons and healthy internal competition: the mere comparison with another who is performing well facilitates performance. This latter effect is longstanding in the scientific literature. In the late 1890s, Triplett showed that children wound a fishing reel faster when paired with another child than when alone. This everyday phenomenon of social facilitation can be experienced, say, at the gym when running alongside another on the treadmill. The mere presence of another runner may be enough to spur you on to exhausting, heart-palpitating speeds.25

Remaining Organizationally Fit

Remaining organizationally fit is like exercise. It unfortunately takes our bodies a long time to build strength and endurance, but no time at all to lose them. Thus, once the executional abilities of the workforce are weakened, building up capabilities again requires more effort than the managerial neglect it took to tear them down. The erosion of organizational abilities occurs in four easy steps:

Abandon Merit

Most organizations say they have merit programs in place. These programs, however, often are so horribly misshapen and riddled with bias that these may be described as false meritocracies. They are merit programs in theory but not in substance. The companies go through the laborious, time-consuming motions only to yield dubious, often counterproductive, outcomes. As the causal connection between performance and pay and promotions are severed, those who are most able to leave the organization for more hospitable places, do.26 The futility in advancement and growth in compensation based on factors under one’s direct control, in addition to the specter of undeserved accommodations for lackluster performers, are too much for superior performers to take.27 Consequently, mediocre performers become cemented in place and crowd out high potential newcomers who rapidly see their futures curtailed by less ambitious and less talented employees.28

Employees are most satisfied with their compensation when certain conditions are met.29

• Equitable: The company has a pay-for-performance organizational charter and expressed desire to reward the most deserving.

• Accurate: Efforts are made to mitigate false assessments and suppress bias (see box 10.2 for common rating biases).

• Reflective of contributions: The nature and size of rewards are commensurate with the magnitude of the contributions.

• Consistent: The same standards are applied evenhandedly across the organization.

• Correctable: Each person has an opportunity to describe their accomplishments and to appeal decisions that seem wrong.

• Representative: Evaluations consider the totality of performance and are not isolated incidences or behavioral slices of a much larger performance domain.

Box 10.2

Common Performance Biases

• Centrality: The Lake Wobegon effect—raters view everyone as average to slightly above average

• Range Restriction: Raters tend to make very small discriminations among people and, thus, use only a small portion of the rating scale in their evaluations

• Leniency: The inclination to rate people higher than actual performance would warrant

• Severity: The inclination to rate people lower than actual performance would warrant

• Selective Recall: In attempting to reconstruct a year of performance, the most recent events will be the most salient

• Halo (Horns): The tendency for favorable (unfavorable) impressions and general likability (unlikability) to color judgments about performance

• Attributional (The Fundamental Attribution Error): Actors view their behaviors as occurring in a situational context (as affected by external events such as luck) and observers see that same behavior as motivated by personal traits (e.g., ability): self-raters, then, tend to be more forgiving of performance problems than supervisory raters, and evaluate themselves more highly

• Perspective: High performers tend to rate themselves more harshly, and lower, than poor performers rate themselves

Most of these conditions can be satisfied through internal reviews called calibration sessions and the use of a senior-level, cross-functional rewards oversight committee. This committee reviews evaluations and pay decisions throughout the organization and has the power to make adjustments if needed. This committee also generates reports of results that it disseminates to key managers so that they can see the decisions and supporting rationales that were made throughout the organization. The calibration sessions are meetings that occur at each level of management. Managers review employees: evaluations and recommended pay increases, abilities and aspirations, and developmental opportunities outside of employees’ immediate areas. In general, the calibration process ensures that performance standards are uniformly applied and that people are in the right roles, are doing the work they enjoy, and are growing. Indeed, juxtaposing tangible standards with levels of performance is an effective means of improving the validity of performance estimates.30

Compromise Performance Standards

As organizations are overtaken by poor to middling performers, correcting a culture of mediocrity becomes increasingly difficult. For starters, poorer performers have mistaken perspectives of their true abilities. They evaluate their abilities as higher than the facts admit. Because they do not have the appropriate professional and vocational norms to hold up as standards of excellence, they falsely believe they are better than they are. (This is called the Dunning-Kruger effect.)31 Indeed, research has shown that high versus low performers are better able to calibrate their performances to valid cues and standards because they have better metacognitions about what they know and do not know.32

The Dunning-Kruger effect has two negative consequences. For one, it breeds complacency. Employees’ inflated sense of aptitude and accomplishment gives them little incentive to work at improving. Thus, they remain moribund in their self-satisfaction. Their performance is arrested with their delusional security that they have done everything within their power to make things better.33 This has been called the “double curse of incompetence.”34

Second, as good as they think they may be, they nevertheless are able to recognize people who are better. Moved by feelings of inferiority, hostility, envy, and resentment, and believing that they may lose their privileged access to power, status, and money to high performers, they make sure that high performers are never hired or are able to prove their mettle by undermining their work by withholding critical information and resources; spreading rumors, demeaning, excluding, criticizing, dismissing, and abusing; assigning superfluous work or work overloads; and using other subversive means to cut others down to size.

The victimization of high performers is a well-established finding in field and lab investigations. The research evidentially supports what we have popularly recognized for some time. The Japanese have a saying, “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down.” Scandinavian countries have the concept of Jante law: a set of rules that maintain that people should not stand out above others.35 Other Western cultures have the tall poppy syndrome that involves the idea of eliminating conspicuous rivals.36 The idea of extinguishing worthy competitors may date back to Herodotus (see box 10.3).37

Periander, the Tyrant of Corinth, sends a messenger to Thrasybulus, the Tyrant of Myletus, for advice on how to rule. Without saying a word, Thrasybulus walks the messenger into a field of wheat and annihilates the tallest stocks, destroying the choice parts of the wheat. The messenger returns to Periander with this vivid description of Thrasybulus obliterating the most prominent wheat in a field. Periander got the message: cut down anything that rises above one’s own stature. He decapitated the best people around him.

Source: Herodotus, The Histories, Book 5, 92e-g.

These negative effects are most acute in competitive environments that are conceived as zero-sum games in which one person’s gain is perceived as another’s loss. These conditions can be tempered by workgroup identification and abundance mindsets (e.g., manifold career opportunities).38 The formation of a workgroup identity and a strong sense of team suggests that all individuals are working in behalf of the group. One individual’s success is viewed in the context of the team: as elevating the entire group as opposed to raising one’s personal status. Thus, people can excel if the superlatives attached to performers are traceable to the idea that the team made the exemplary performance possible. No one stands apart from, or above, the interests of the group.

Fail to Act on Personnel Issues

One of the most common regrets expressed to us by senior managers over the years is that they did not act on personnel issues swiftly enough—or at all. In general, executives need to address two types of personnel matters. One concerns cultural fit. A person may be a superb performer but imposes costs on the organization because their style does not mesh with the values of the organization. The paradigm cases are (1) the high-performing yet egocentric, self-aggrandizing, uncooperative person—the narcissist, for example—who only does what is in their own interest and gives nothing back to the institution; and (2) the micromanager who, for well- or poorly intentioned reasons, continuously inserts themself into projects and never allows others to grow and thrive. Like helicopter, or bulldozer, parents (in parts of Europe, they are called, “curling parents” who sweep the path clear for their little stones), they intervene at every hint of trouble, protecting their young wards from error, tribulation, and distress. Unredeemable versions of these managers must go.

The other problematic person is one who is not fully competent to perform the expected array of duties, including the people who have been “doing the job for years.” They are not, however, working to the extent and quality desired. As difficult as dismissal may be, if success is the goal, it cannot be secured handily without the right people in place. Keeping them where they are or sequestering them in marginal roles are not the answers. Business has the reputation of interpersonal brutality by displacing people with or without cause. Because decisions to terminate are hard for most executives, many adopt a prolonged wait and see attitude that they later regret.

Separations do not have to be angst ridden; they can be handled empathically. Health Catalyst, a health analytics company, for example, considers separations a no-fault incident for reasons resulting from poor performance or cultural incompatibilities. Both parties were mistaken about the relationship and, consequently, the company allots a minimum of three months of severance pay to employees so that life may go on for the employee without putting him or her in financial peril. Additionally, companies such as PURE Insurance, a premium property and casualty company, offers employees a host of career transition options: PURE extends benefits coverages, assists with resume preparation, facilitates networking, provides coaching and advisory services, and covers relocation costs. These practices support honest communications between employees and their employers, ease tensions that may arise during separations, and promote a content league of alumni.

Loosen Hiring Practices

An executive once said to us, “If you don’t want performance problems, don’t hire them.” He well understood how quickly an organization can be compromised by relaxing hiring standards. The counterpoint is clear. Have well-articulated selection criteria for each position, train hiring personnel on interviewing techniques, and rigidly stick to established hiring and selection protocols. Having well-thought-out hiring procedures minimizes the insidious ways that low-caliber applicants may infiltrate organizations. For example, roughly 70 percent of companies have employee referral plans. In general, these are cost-effective means of hiring people who tend to perform better and stay longer than those who enter through external avenues.39 A prototypical program is one in which employees can recommend candidates for employment and, if the person is selected and remains with the company for 45 days to six months, the referring employee receives a cash bonus. People who are concerned about their careers, however, may have an incentive to refer less-qualified candidates into one’s own area. Additionally, people who are not especially committed to the organization or who are self-interested actors may refer others simply for the money or to advance candidates who will be beholden loyal supporters.40 These adverse results would be hard to obtain with thorough hiring procedures in place. Some companies take extra precautions by entertaining only those referrals that come from outside the referrer’s immediate area and only after employees have been in the organization for a minimum amount of time and are confident of their place in the organization.

Most companies are not strictly meritocracies. This is a good thing. As Michael Young’s satirical sociological novel, The Rise of the Meritocracy, suggests, merit can be overdone.41 At the extreme, merit can have a Hunger Games–like quality in which some people acquire more than they need through their talents and others have barely enough to survive. The exaggerated meritocracies in which the most able parlay their reputations and capabilities into greater rewards such that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer is called the Mathew effect (see box 10.4).42 Given the biblical overtones, it is unsurprising that talent and rewards have a moral nexus that finds expression in the Protestant ethic.43 The Protestant ethic encompasses a composite set of beliefs that through dedication, hard work, and a degree of asceticism, one will find fulfillment and reward. Those who exercise God-given gifts will be blessed and rewarded and those who do not, the idle, condemned. Unfortunately, in real life, we often make the logical fallacy of affirming the consequence. If people get what they deserve, we also tend to believe they deserve what they get—an economic morality play of sorts that provides a hardy defense for the status quo.44

Box 10.4

Parable of the Talents

In the parable of the talents, a magister entrusts eight talents to three servants while he travels: five talents for one servant, two for another, and one talent for the third. A talent originally was a unit of weight (25.86 kg) associated with the content of silver and gold in coins. A talent was a lot of money: at 0.46 per gram of silver in 2018, one talent today would be worth $11,896. Thus, a talent was exclusive to the wealthy and represented a unit of high inherent value. The two servants with more talents invest the money and produce a handsome return for the magister. The third servant safeguards his talent by burying it and is rebuked for not making more of his talent.

In organizations, merit, or the principle of equity, is not the only distributive rule that is used. The values organizations wish to inculcate are inadequately supported through merit alone. The social ideal of semimeritocratic organizations is to balance equity with allocations based on equality and need.45 On certain occasions, each distributive rule makes sense to implement in organizations. For example, a company may decide to pay people a living wage regardless of abilities or market circumstances. Patagonia, the socially responsible retailer for outdoor enthusiasts, pays a living wage using one of the several available calculators. The company believes that providing a minimum quality of life supersedes other considerations in the distribution of resources. Similarly, many benefits, such as health and welfare plans, serve the same function. These benefits provide minimum safeguards for employees’ well-being that frees them from the insecurity that can intrude on performance and undermine personal welfare. Some companies also maintain significant reserves to assist employees when they have emergencies. Relieving employees from worry and providing greater surety that their basic needs will be met fosters higher levels of organizational commitment and performance.46

As with most allocation rules, there are appropriate and inappropriate applications. For example, during our lengthy time in consulting, we have heard of circumstances in which employees (mostly men) were given pay increases following the birth of a child to lend financial assistance to the growing family. As it happens, this practice is common enough that it has a name and a tangible consequence: the so-called fatherhood wage premium has been estimated to account for 3 percent to 10 percent in salary above singles and childless couples.47 Therefore, in situations in which a baby blanket or gift card would do, these companies blemish a system that ostensibly was reserved for merit. Employees’ needs could easily be handled through other mechanisms as opposed to using reward outlets that were never intended for these purposes.

Equality is simply a rule that recommends that people share in the bounty of one’s efforts equally. It makes sense to treat people equally when either their individual contributions or the outcomes of their efforts cannot be carved up. For example, a win or loss in sports cannot be divided among members of the team. Similarly, system-wide profits or credits for a videogame product cannot easily be parsed and traced to the contributions of each person. Consequently, organizations often share a percentage of the profits equally among employees and include all contributors on the credit roll.

It is possible to recognize team and individual performance at once. A company may recognize a team as an entity while recognizing particular members for their specific achievements. For example, a company can celebrate team wins but also call out individuals for personal accomplishments, creativity, and exemplification of cultural values. Many corporate incentive plans have these mixed components in which a portion of a pot of funds are distributed among members equally and a portion is distributed to members based on individual performance.

The complementariness of equity and equality in organizations is critical. Good organizations try to maintain a balance between the two, and with good reason. Egalitarian distributions are designed to promote cooperation and healthy social relations. Equitable distributions recognize personal achievements that tend to foster competition.48 Companies want the best of both worlds. They want people to strive on their own accord while also maintaining quality social relations to minimize the interpersonal conflicts necessary for smooth execution. They want personal excellence without cutthroat competition and want cooperation without social loafing or free riding. In this regard, the divisibility of performance may be essential. Indeed, without distinct responsibilities and ways of telling the contributions of one person apart from another, people are likely to exert less physical and mental effort. In 1913, a French agricultural engineer named Max Ringelmann asked individuals to pull on a rope, and then repeated the exercise with groups of people pulling. In measuring the force of the pull, he observed that group members put in less effort than each person pulling alone. He further noticed that as the group size grew, the loss of individual effort became more marked. Thus, when personal responsibility for results is diffused or when individual efforts are hard to discern or perceived as unimportant, people tend to ease up on the intensity to which they will exert themselves, or socially loaf.49

Some determination of a person’s value has to be made at some time whether as measures of contribution to a team or annual achievements against goals. Yet measurement is a frustrating topic for several organizations that believe it has become a nuisance that is too unpleasant to continue.50 Nevertheless, despite high-profile corporate defections from the end-of-year evaluation rite that include Adobe, Dell, IBM, REI, and Microsoft, the performance appraisal process remains a staple in most organizations.51 Done properly and with conviction, the process can work. Recent studies have shown that evaluation scores are functionally informative and are associated with merit increases, promotions, and other organizational decisions.52 The traditional process, however, has not accomplished its desired ends in all organizations and, therefore, a few companies have chosen to opt out.

The reasons for this abandonment of a formal performance appraisal procedure are threefold. First, the retrospective aspect of the review is superfluous to performance improvement; second, life inside organizations has become more unpredictable and transient, and annual cycles are poorly suited for faster paces and rapid pivots in direction; and, third, work increasingly is performed in teams versus by sole contributors. In general, attention has shifted away from measurement toward ongoing dialogue between managers and employees, continuous feedback, and personal development. Taken together, companies view the performance management process as a lot of work for which they see little return.

We have reservations about total abdication of performance evaluations. We applaud the emphasis on communications and personal growth; nevertheless, companies that have jettisoned formal ratings still must render evaluations about people for myriad reasons at various times. Our fear is that in the absence of a formal process, decision making will be ambiguous and of questionable accuracy—that the appraisal process will go underground and become hidden and prejudicial. We understand the connotations that negative evaluative labels can have. We also understand managers’ fears of damaging employer–employee relations through direct, albeit diplomatic, negative feedback. Furthermore, we recognize that a rigorous process can be highly time-consuming. Nothing says, however, that performance reviews must be conducted with the same intensity on every person every year.

Quite a bit could be said about performance measurement; thus, our comments below are not exhaustive. Instead, we highlight a few items that receive less attention in the business literature.

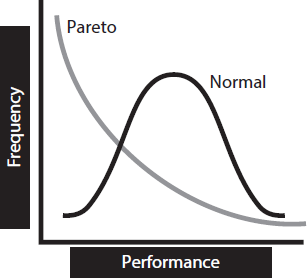

• Performance may not be normally distributed. In a comprehensive study of more than six hundred thousand researchers, entertainers, politicians, and athletes, the paper’s authors found that performance is distributed according to an exponential power law as opposed to the more familiar normal distribution in many circumstances (see figure 10.1).53 The thicker positive tale indicates that there are more high performers than the typical normal distribution credits. Therefore, if companies were to force people into a normal distribution, they would be underestimating the true number of high performers. (The power distribution also suggests that most people are ordinary, at best, but the sample the researchers used would have included only people who met minimum qualifications and, therefore, “average” in that context may be “above average” or “good enough” to be included on a list.)

Figure 10.1 Normal and Pareto distributions.

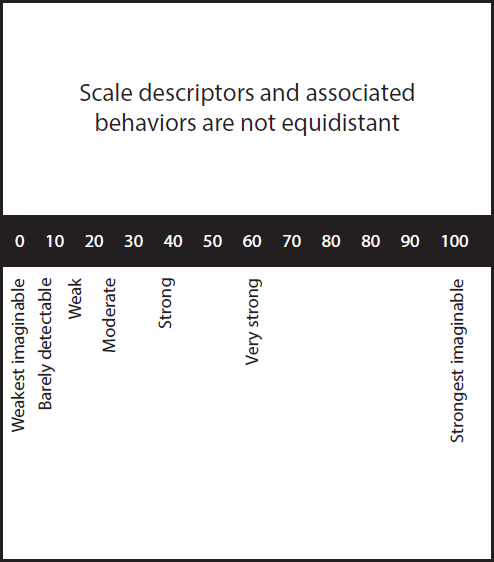

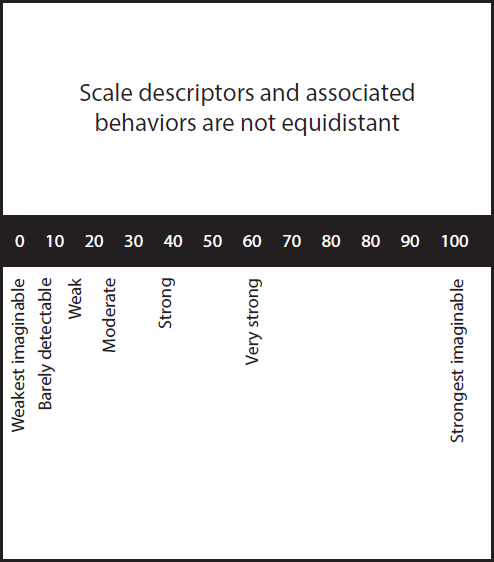

• Performance may be best measured on a ratio scale (known as a general labeled magnitude scale54). A plethora of rating scales exist. We would be hard-pressed to qualify many of these as psychometrically sound to be used in practice as they would not meet minimum standards for reliability and validity. There is much room for improvement. Apart from those problems, most of these measures of performance presume that the distances between ratings are equidistant. For example, the conventional four- or five-point scale that evaluates employees on the extent to which they meet expectations, or adhere to certain, specified behaviors, assumes that the distance between one and two is the same as between a four and a five. Our experiences, however, suggest that performance may be best assessed on ratio scales in which distances between “good” and “very good” and between “bad” and “very bad” are not the same. This corresponds to managers’ frequent requests for more rating room at the top of the scale so they can make finer discriminations in performance. A sample magnitude scale is provided in figure 10.2. As deployed, sample behaviors would be scaled and overlaid onto an instrument such as the one depicted. Furthermore, as a means to square the the lower and upper anchor amongs people, respondents are asked to reflect on the most extreme or intense experiences in any domain that pertain to the attribute being measured; in that way, the scales are similarly calibrated to individuals’ range of experiences.

Figure 10.2 Generalized labeled magnitude scale.

• Managerial performance training helps. Studies indicate that organizations that provide more performance management training have performance systems that deliver more valued outcomes, such as increases in individuals’ performances and greater employee retention.55 Frame of reference training is one aspect of training that is proven effective in producing more accurate evaluations. With this type of training, trainees learn to associate sample behaviors with specific conceptualizations of performance so that people who observe the same behaviors interpret them in the same ways.56

• Assessments are more reliable when made of multiple items, on multiple occasions, by multiple people. Taken together, these “multiples” afford a better sampling of behaviors and a more accurate rendering of performance. These principles are well-supported in the psychometric literature. None of these, however, are used regularly in organizations. The idea behind multiple items is that any concept of performance will be poorly captured, or summarized, through a single item. For example, there are many ways to describe “Provides excellent service.” “Excellence” may be defined as “timeliness,” “courteousness,” and “competence.”

Multiple situations necessitate ongoing communications and feedback. If managers are close enough to the work, they can suitably fill this role. Increasingly, however, organizations have been using recognition programs to gather ongoing feedback to capture and describe the feats of their personnel. Recognition plans come in all shapes and sizes. Discretionary continuous plans are ways for colleagues and customers to spontaneously thank one another for their special efforts through a kind word. Recognition plans also can involve formal criteria and ceremonies in which winners can be:

• Selected by individuals, committees, or all-company votes

• Selected by upward (employees vote on managers) or downward (managers vote on staff) votes: For example, Edmunds, the authoritative source for all things cars, in a highly visible leadership program called Pave the Road, selects the best managers for recognition on standing criteria each year. These criteria include managers’ ability to inspire, develop, and connect employees (e.g., to resources, people, committees), while preserving employees’ welfare (e.g., not burning them out). The ratings are cross-validated by interviews and three winners are selected and announced at the annual all-employee meeting. The company produces videos of employees describing what they have enjoyed about their managers and how these managers changed their lives.

• Awarded to individuals or teams: For example, North Carolina publisher N2 reserves a portion of its monthly meeting to recognize exemplary contributions to the company. We were on premises the day the entire Editorial Department won. Amanda, the head of the department, is a wonderful visual artist. She drew likenesses of each of her staff members wearing Marvel-esque superhero outfits and described each of their super-human powers in a wonderful and moving tribute to the team.

• Recognized with cash or symbols: Sometimes the award can be big. For the super-exceptional performer of the year, Arkadium, a New York–based digital marketer, bestows the Infinite Possibilities Prize. Twenty-five thousand dollars is given to an employee to do anything he or she wants from going on an extended yoga retreat to working with an established novelist on a first work of fiction. Many times, however, the only symbolic show of appreciation that employees want is a thank you.

• Recognized for financial or nonfinancial results: N2 also holds an end-of-year ceremony in which they bestow Lunch Pail Awards. These whimsical, highly sought-after awards go to the outstanding performers or pure exemplars of institutional values. The award is a metal lunch pail from the 1930s with the person’s name etched into the side with car keys.

One interesting facet of recognition plans is that, regardless of their formality and timing, they not only affect the beneficiaries of the awards but also other members of a group. In fact, research shows that team members are positively influenced more than the award recipients. In one study, groups of eight subjects were given a data entry task to perform in two sessions. After the first session, either none, one, three, or all were publicly provided with thank you cards for their performances (correct entries per minute) in session one of the task. On average, people who were thanked did significantly better during the second session. However, people who saw others receive the notes of thanks performed even better.57 Either through want of betterment or greater appreciation, the performances of the unrecognized improve.58

To a large degree, recognition programs provide various perspectives on performance and, therefore, satisfy the condition of having multiple evaluators. Sometimes, however, a company will want to deploy more formal evaluative procedures particularly regarding the quality of management—and deploy 360-degree reviews. These are evaluations of individuals’ performances that use anonymous input from multiple proximal parties as the sources of information. Because correlations between supervisory and employee ratings of performance are small to middling, the added information from coworkers at different organizational levels enhances the width and depth of performance data and increases the reliability and validity of the ratings.59 Once again, the benefits of the 360-degree feedback extend beyond the individual to the system as a whole. For example, a study of 250 firms and ten thousand employees found that the use of multisource feedback was associated with higher sales per employee. These effects are attributed to improvements in employees’ functional abilities and greater knowledge sharing promoted by the feedback.60

• Performance is multidimensional. Performance can be conceived in different ways. Broadly, performance can be conceived as what gets done and how it gets done. The former concerns outcomes—that is, the things produced or created. The latter pertain to personal qualities that enable people to effectively perform. These are typically thought of as competencies, defined as the knowledge, skills, and abilities that employees possess. Having critical competencies that allow people to succeed across functional areas typically is what we say when an employee has potential. They have capabilities that generalize across situations and, when properly utilized, are instrumental in producing results. Thus, doing well on the current job may or may not be predictive of performance in new roles, but having the requisite competencies should be. Organizations often will merge these two aspects of performance into a three-by-three matrix (a “nine-box”) in which accomplishments (outcomes) form one axis and competencies (potential) form the other and then make pay and development determinations based on where employees fall in the matrix. The integration of information in this way conveys the right messages: that two of a manager’s most important duties are to develop employees’ potential and to help them to succeed.

A summary of many of the ideas used to enhance and reinforce performance discussed in this chapter are summarized in box 10.5. Although we relegate the need for feedback to a single item in the list, this should not understate its importance. Much has been written on the why’s and how’s of feedback, and we need not retrace that ground here. Nevertheless, we will say that the easiest and best way of giving and receiving feedback is naturally—in a manner that is built into the routines of the organization and that is as automatic and effortless as breathing. In this regard, some organizations are adept at creating feedback environments where individuals are comfortable constructively exchanging information of both positive and negative valence.61 For example, at Arkadium, feedback is a continuous, positive, habitual experience. A modest sample of their feedback culture occurs every Monday at the staff meetings that are held without fail. A portion of every meeting is reserved for “Li’l Wins and Big Thank Yous” in which people are able to recognize individuals and teams for special efforts and results. It is a period patterned after a Quaker tradition in which Friends sit silently together and, when moved to share thoughts inspired by a spiritual connection, they stand and do so. The practice gives people a way to be mindful of the efforts of others and to publicly express gratitude for good work. If the research is correct, these feedback practices maintain open lines of communication, clarify task activities and goals, and generate more creative and innovative solutions to problems.62

Box 10.5

Path to Performance

Hire and promote managers who have high standards and understand what great performance looks like.

Gather information about different kinds of performances throughout the year from multiple people at multiple times.

Provide continuous coaching and feedback that is immediate, specific, and actionable (do not mandate dialogue, but recognize managers who do this well).

Clarify what “performance” means and construct the proper scales accordingly.

Calibrate performance ratings and recommended pay increases across the organization to ensure equity; this process has been found to improve accuracy of evaluations.

Train managers on how to equate various performance standards to ratings on a scale (frame of reference training).

Make development a fundamental part of the program; set aside time and resources accordingly.

Make the program matter by paying financial and nonfinancial tribute to the best performers.

Ultimately, when companies become ordinary it is because managers allow it. The decline begins innocently around the edges with a few poor hires and politically motivated pay and promotional decisions. The effects of these decisions slowly encroach on the whole organization. As degeneration accelerates, it becomes increasingly difficult to halt the decline as the oozing body spreads.

In dynamic settings in which the quality of the workforce is subject to change, it is critical to be unyielding on several fronts to keep the company vibrant—to assert positions that are immovable. Thus, we provide our admonitions, the five nevers:

• Never compromise on hiring: In addition, good organizations continuously monitor the hiring process and make refinements as needed. For example, they will collect and analyze information on who succeeds in the organization and modify hiring criteria to be most diagnostic of job performance.

• Never keep people who are unable to perform the work: Nor should you keep people whose actions dismantle operative institutional norms and values. We caution that performance depends on many factors and we have seen countless instances in which a person failed in one role but flourished in another. Therefore, we encourage companies to contemplate whether people who are failing in their current roles might have potential to excel elsewhere. We also recommend that companies not bifurcate the workforce into stars and everyone else, and exclusively attend to the former and forget about the latter. All companies have the all-important, unheralded B-players whose solid performances and dependability constitute a stable core of the organization and further a more ambient enterprise.63 These employees should have equal access to all the developmental and career advancement opportunities that are available to the stars.

• Never allow expedience and politics to intrude upon merit-based decisions: We qualify this statement by reiterating that not all decisions should be merit based and that good companies try to find the right balance of allocations based on different distributive goals. This includes the necessity of balancing merit with need and equality to alleviate anxieties and foster social cohesion.

• Never detach the provision of benefits from the enactment of performance: In organizations, everything given to employees is predicated on the organization’s ability to pay; thus, it is necessary for organizations to maintain a strong sense of reciprocity between staff and themselves—to keep attitudes of excessive entitlement in check (that people have a right to benefits that they do not have to repay in kind).64 Thus, we encourage companies to maintain a persistent, unwavering beat of performance as an organizational backdrop so that mutual expectations between employers and employees are clear.

• Never accept an unqualified manager: Like an orchestra, leadership is a mediated art form. The way leaders get their message across is through the virtuosity of management throughout the organization—poor management, poor musicians, poor music. Indeed, Gilley and colleagues list actions that qualify as managerial malpractice, which include trying to fix the incorrigible and hiring, promoting, and retaining managers who do not have the proficiencies and interpersonal acumen to work with others effectively.65