Appendix G: Risk Assessment

Introduction

Risk management is the process of selecting and implementing countermeasures to achieve an acceptable level of risk at an acceptable cost; beyond the cost–benefit analysis discussed previously in chapter “Understanding Forensic Readiness.” By examining in depth the potential threats faced by an organization, a better understanding of business risk can be gained that subsequently leads to identifying strategies, techniques, approaches, or countermeasures that reduce or mitigate impact. At a high level, this can be achieved by asking three basic questions:

• What can go wrong?

• What will we do?

• If something happens, how will we pay for it?

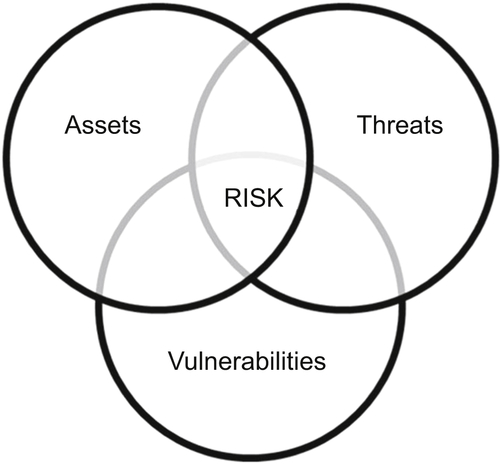

Thinking about these questions in context of a particular organization, it might become clear that there are some areas where risk management could be applied, such as weaknesses in the software development life cycle or manual processes that are prone to human error. Since the potential damage or loss to an asset exists, the level of risk is based on the value given to it by its owner and the consequential impact. Additionally, the probability and likelihood of a vulnerability to be exploited must also be taken into consideration. Therefore, as illustrated in Figure G.1, risk cannot exist without the intersection of three variables: assets, threats, and vulnerabilities.

What Is a Risk Assessment?

A risk assessment is simply a thorough examination of what could cause harm to assets so that an accurate decision of how to manage the risk can be made. Risk assessments do not require an overengineered approach of new processes, methodologies, or loads of paperwork. There are several industry-recognized methodologies available to use during the analysis stage of the risk management program.

Depending on the type of business offered by an organization, one methodology may be preferred over another; while others may be mandated through regulations to use a particular methodology or a decision is made to develop one that meets their specific business needs. Generally, organizations have the option of conducting a risk assessment by following one of these two approaches.

Qualitative Assessments

Qualitative assessments are focused on results that are descriptive as opposed to measurable; where there is no direct monetary value assigned to the assets and its importance is based on a hypothetical value. Organizations should typically look to conduct a qualitative assessment when the:

• assessors have limited expertise

• time frame allocated for the assessment is short

• organization does not have data readily available to accommodate trending

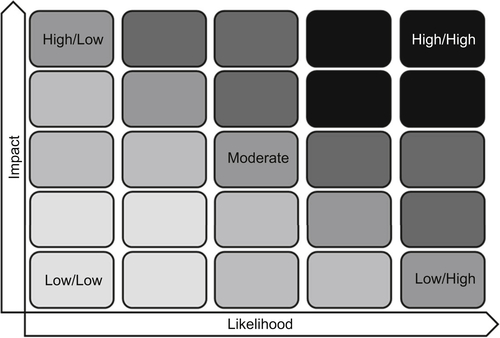

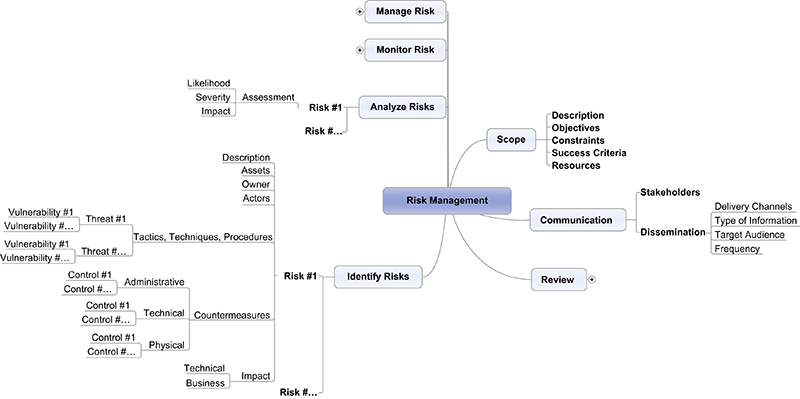

Analysis commonly performed in this type of assessment can include several layers of determining how assets are susceptible to risks. This includes the correlation of both assets to threats and threats to vulnerabilities, as described further in Appendix H: Threat Modeling, as well as the determination of likelihood and the level of impact that an exploited vulnerability will create, as illustrated in Figure G.2.

In a qualitative assessment, the output generated from the comparison of likelihood and the level of impact is the severity the risk has on assets. Generally, the higher the risk level the greater the priority on the organization to manage the risk and protect its assets from potential harm.

Quantitative Assessments

The primary characteristic of a quantitative assessment is its numerical nature. Use of variables, such as frequency, probability, impact, or other aspects of a risk assessment are not easily measured against mathematical properties like monetary value. Quantitative assessments allow organizations to determine whether the cost of a risk outweighs the cost of managing a risk based on mathematics instead of descriptive terms.

Organizations that have invested in gathering and preserving information, combined with the enhanced knowledge and experience of staff, are better equipped to conduct this type of assessment. For this reason, getting to end of job requires a larger investment in resource knowledge and experience, time, and effort.

Knowing that quantitative assessments follow a mathematical basis, organizations that decide to conduct this type of analysis should consider performing the following series of calculations.

Single Loss Expectancy

The first calculation to be completed is the single loss expectancy (SLE). The SLE is the difference between the original and remaining monetary value of an asset that is expected after a single occurrence of a risk against an asset. The SLE is calculated as

where AV is the monetary value assigned to an asset, and EF is an percentage representing the amount of loss to an asset.

For example, if the AV has been identified as $5000 and the EF is 40%, then the SLE would be calculate as

Annual Rate of Occurrence

Following the SLE, the next calculation to be completed is the annual rate of occurrence (ARO). The ARO is a representation of how often an identified threat will successfully exploit a vulnerability and generate some level of business impact within the period of a year. The ARO is calculated as

For example, if trending data suggest that a specific threat is likely to generate business impact one time over four periods, then the ARO would be calculated as

Annualized Loss Expectancy

Having values for both SLE and ARO, the next calculation to be completed is the annualized loss expectancy (ALE). The ALE is the expected monetary loss of an asset that can be realized as a result of actual business impact over a 1-year period. The ALE is calculated as

For example, if the ARO is 0.25 and the SLE is 2000, then the ALE would be calculated as

With the ALE completed, organizations can use the resulting value directly in a cost–benefit analysis as described in, Appendix E: Cost–Benefit Analysis. For example, where a threat or risk has an ALE of $500, then the cost–benefit analysis would identify that investing $5000 per year on a countermeasure would not be recommended.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Depending on the goals for performing an assessment, both the qualitative and quantitative approach present its own benefits. Neither approach should be overlooked as a tool for performing risk assessment because they are unique in how they demonstrate risk to stakeholders.

With qualitative assessments, the approach is simpler because it does not require the in-depth analysis of numerical values through formulas and calculations. Analysis results are simpler for stakeholders to understand because it leverages business terms to communicate the level of risk involved. However, there is no escaping the fact that qualitative assessments are more subjective because they are based on the organization’s experience and judgment which makes it more difficult to defend. The ability to monitor the implementation of countermeasures using labels and terms is difficult because it cannot be measured.

On the other hand, a quantitative assessment is considered objective because it is not influenced by subjective experience or judgment. It relies on predetermined formulas and calculations to arrive at the valuation of a risk decision based on numerical measurements. However, this approach requires organizations to have existing data, more experience, and be willing to invest more time because it is based on factual numbers and predetermined formulas.

Tools, Methodologies, and Techniques

Organizations will select their risk assessment tools, methodology, and techniques based on what works best for their specific needs, capabilities, budget, and timelines.

Tools

Given the availability of industry resources, completing a risk assessment does not need to be an overly complicated process. Several tools are readily accessible to make the risk assessment tasks easier; including software, checklists, and templates.

Depending on volumes, gathering and processing data can be demanding and require significant efforts. Organizations should look to invest in automated tools that can alleviate the time needed to complete these tasks. Regardless of whether the organization plans on purchasing or building tools, this decision should be based on aspects such as appropriate timelines, skill sets, and the need to follow a proper system development life cycle (SDLC).

As organizations perform more risk assessments, they will begin to identify patterns where there are similarities in tasks being completed, such as cataloging threat agents and threats. In these situations, the use of checklists may be beneficial to ensure that the risk assessment considers all relevant information even if it may not apply in each instance.

Reviewing existing policies and procedures for relevant security gaps can be a complex and time-consuming task. When used properly, templates can be effective in improving operational efficiencies and accuracy of the risk assessment results.

Methodologies and Techniques

Generally, all risk assessments follow a similar methodology consisting of the same techniques to arriving at a final risk decision, including analyzing threats and vulnerabilities, asset valuation, and risk evaluation.

However, there is no single risk assessment methodology that meets the needs of every organization because they were not designed to be “one-size-fits-all.” Ultimately, each organization is unique in its own respect and has their own reasons for why they would complete risk assessments. Therefore, a variety of industry-recognized risk assessment methodologies have been developed to address the varying needs and requirements.

Contained in the “Resources” section of this chapter, a series of different risk assessment methodologies have been provided as references. It is important to note that inclusion of a methodology below does not suggest that these are better or recommended over other models that were not included.

Risk Life Cycle Workflow

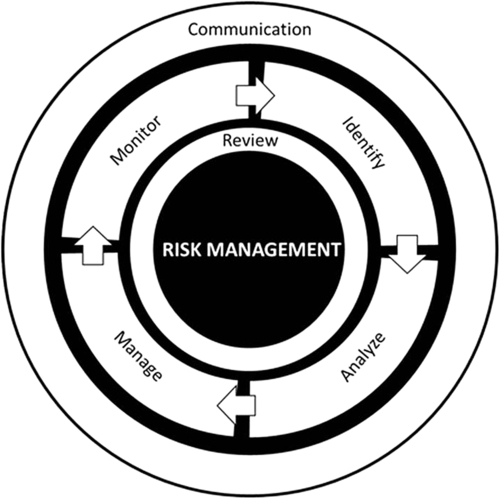

An assessment of risk at any given time will naturally evolve over time and the exposure to the organization will either increase or decrease accordingly. Supporting constant changes in business risk requires that the risk management process is performed regularly; not as a one-time exercise.

Effectively managing risk should be shared between multiple stakeholders because the responsibility and accountability of doing so cannot generally be placed on a single party. For example, while information security is responsible for providing guidance and oversight, accountability for implementing recommendations is with the business line that owns the risk.

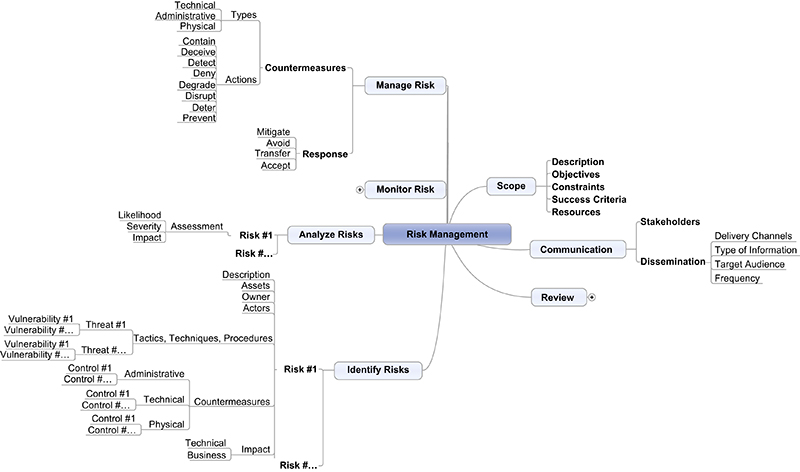

Several well-established risk management frameworks are available that, while slight differences exist in terminology and stages, all use a very similar approach to the risk management life cycle. Described in the following sections, Figure G.3 illustrates the four-stage workflow involved in the risk management life cycle.

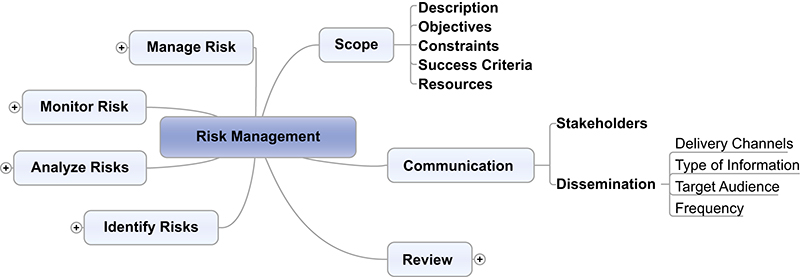

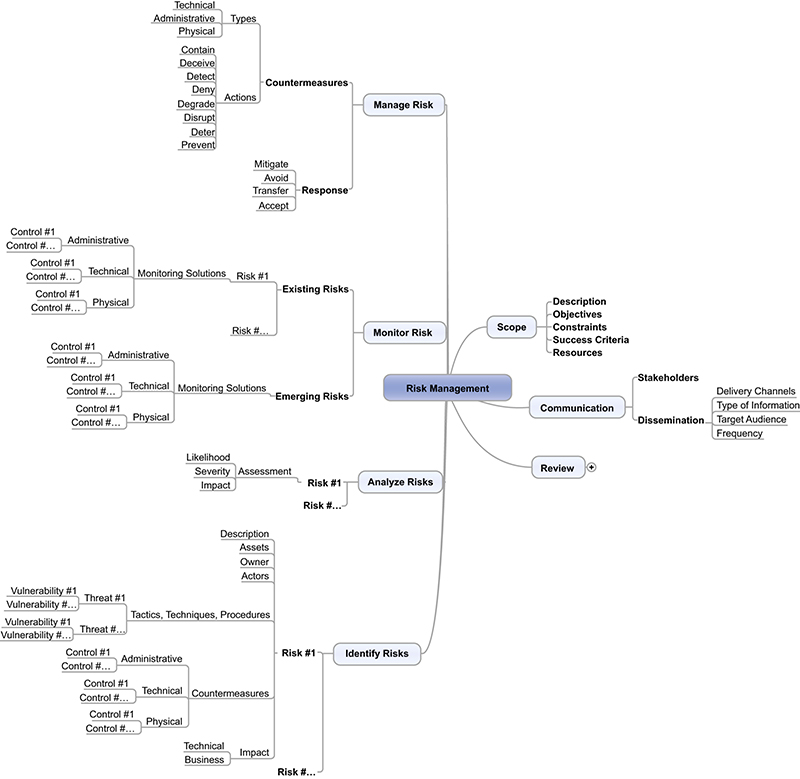

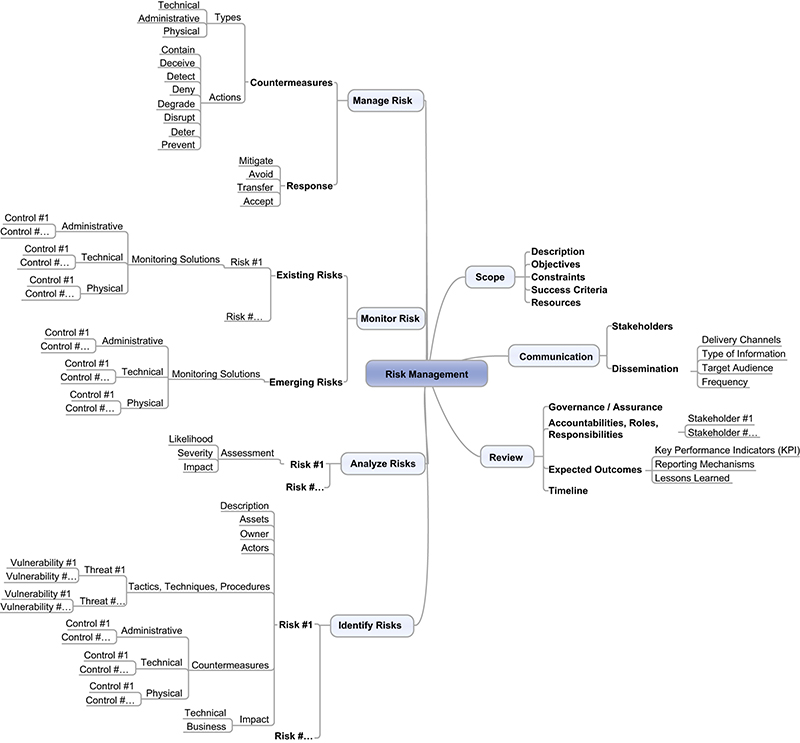

Visualizing Risk

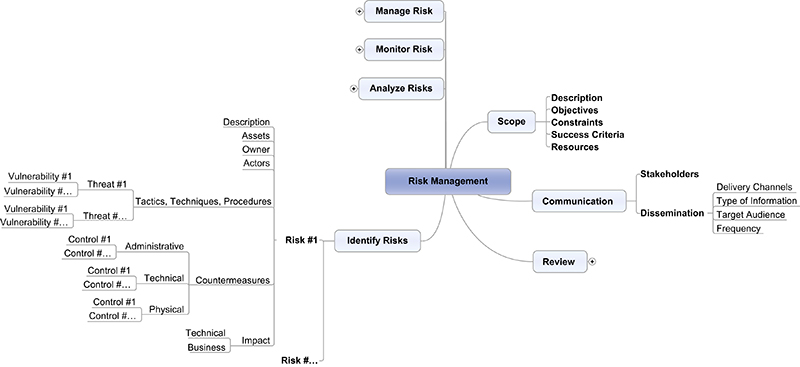

Challenges with demonstrating business risk to stakeholders are largely attributed to delivering information in a format that is difficult to interpret. Illustrated in Figure G.4, a mind map is an excellent tool for conceptually representing risk in a nonlinear format to build out the framework for assessing and managing the risk.

Mind maps are a type of diagram that is based on a centralized concept or subject, such as risk management, with the components revolving around it like a spiderweb. The use of a mind map not only enhances communications through the use of categorized groupings, but also allows the risk management team to quickly record and capture ideas being discussed during meetings.

Communication

Communication is an integral component of risk management. It is essential that the key stakeholders responsible for managing risk throughout the organization, such as upper management, understand the reasons why decisions are being made and why the selected strategies, techniques, approaches, and countermeasures are necessary.For this reason, the communication activities performed in this workflow should not be viewed as a sequential stage, but instead represented as a continuous activity.

By having consistent communication, risk information can be more effectively reused throughout the organization; reducing the need to conduct more than one risk assessment on the same area for different purposes (ie, planning, auditing, resource allocations). When defining communication activities, organizations might include details that provide direction on the:

• types of information that needs to be communicated at various stages (ie, what information do stakeholders need or want)

• target audience for the various types of information (ie, management)

• means used to distribute communication to the target audiences

Stage #1: Identify

Risk cannot be managed without first recognizing, describing, and having a solid understanding of what potential risks can significantly impact an organization. To start, stakeholders (ie, employees, investors, etc.) should be provided with clear direction on what the organization’s expectations are when it comes to identifying risk. Once informed, all stakeholders should be provided with the appropriate tools and techniques—such as training, workshops, checklists, etc.—that will be used to accurately identify risk.

To facilitate stakeholder involvement in the process of identifying risk, organizations should provide them with a taxonomy to ensure the use of consistent and common risk terminology and classifications throughout the risk management process. Further details about how to build a taxonomy can be found in, Appendix F: Building a Taxonomy.

Through a series of face-to-face or virtual sessions, stakeholders should contribute to the identification of risks as both collaborative and individual participation. After the collective results have been reviewed, the risk management mind map can be expanded further to include the specific components of the identification stage as illustrated in Figure G.5.

Stage #2: Analyze

Having identified all relevant assets, threats, and vulnerabilities that constitute risk, the next step is to individually analyze and prioritize all risks that have any potential of generating business impact. Analyzing each risk individually helps to prioritize them so that organizations can focus resources and efforts to managing the most appropriate risk first. When defining assessment activities, organizations might include details that provide direction on:

• who should be involved

• the level of detail required

• what type of information needs to be gathered

• how the risk assessment should be documented to deal, for example, with planning activities

As each risk is analyzed, organizations should take into consideration their risk tolerance as a factor in risk scoring. By doing so, organizations will get a better representation of risk by being able to identify the delta between the assessed risk level and what they consider to be an acceptable risk level. Generally, there are several tools and techniques available to analyze and prioritize risks. As illustrated previously in Figure G.2, at a minimum performing a risk assessment involves determining the likelihood of a risk occurring and the level of impact it will generate, ultimately achieving the severity valuation of the risk.

Output from the risk assessment will create an understanding of the nature of the risk and its potential to affect business operations and functions. After determining the impact of each risk, which is the combination of likelihood and severity, the risk management mind map can be expanded further to include the specific components of the identification stage as illustrated in Figure G.6.

Stage #3: Manage

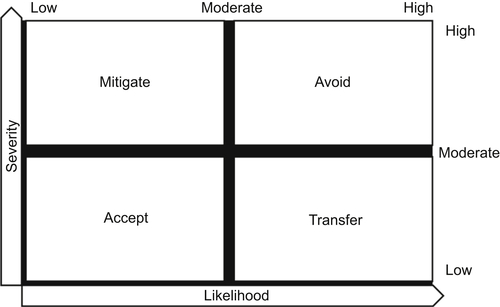

Completion of the preceding assessment has resulted in each risk being assigned a ranking in terms of the level of impact it has on business operations and functions. With this knowledge, the organization must determine how to minimize the probability of negative risks while improving its security posture. This requires that, for each risk, a decision is made on how best to respond and manage the level of impact. Illustrated in Figure G.7, the four responses to risk include:

• Mitigate risk, where likelihood is high but severity is low, through the implementation of countermeasures to reduce the potential for impact

• Transfer risk, where likelihood is low but severity is high, by shifting all—or a portion of—the risk to a third party through insurance, outsourcing, or entering into partnerships.

• Accept risk, where likelihood and severity are low, if the result of a cost–benefit analysis determines that the cost of mitigating the risk is greater than the cost to implement the necessary countermeasures. In this scenario, the best response is to accept the risk and continuously monitor it. Details on how to perform a cost–benefit analysis can be found in, Appendix E: Cost–Benefit Analysis.

Where the organization has determined that the best response to a risk is by implementing countermeasures, it is important to remember that these controls can be applied in the form of administrative, physical, or technical controls. After determining the best response, the risk management mind map can be expanded further to include the specific components of the identification stage as illustrated in Figure G.8.

Stage #4: Monitor

Generally, risk is all about uncertainty. Even though a formalized risk management program has been implemented, and up to this stage has been able to identify and get control over known risks, organizations need to ensure that the process is not performed as a one-time activity. Instead, the need to implement continuous monitoring within the risk management program has two fundamental aspects that are essential to ensuring its effectiveness.

The first aspect is about keeping a close and steady watch on previously identified risks. The advancement in technology evolves the way modern threats, vulnerabilities, and risks can impact business operation. To counterbalance this effect, organizations must be vigilant in how they monitor this anomaly to determine if a previously documented risk has changed. If a change has been detected, the organization has to reassess the original risk to determine if their risk response also needs to be changed.

The second aspect is about identifying any new risks that have emerged. The advancement in technology also introduces new threats, vulnerabilities, and risks that have the potential to generate new kinds of business impact. To counter balance this effect, organizations must implement and diligently follow a proactive management program to identify when new risks surface. Through a proactive approach, there will be greater opportunities to manage risks before they materialize and avoid impulsive risk response decisions.

The best method of risk monitoring comes from the combined implementation of administrative, physical, and technical solutions. After selecting the most appropriate risk monitoring solution(s), the risk management mind map can be expanded further to include the specific components of the monitoring stage as illustrated in Figure G.9.

Review

Activities performed while reviewing the risk management are an important aspect of continuous process improvement. Reviewing the collective risk management approach and process is essential to providing stakeholders (ie, management, investors, etc.) with awareness and assurance that the organization’s overall risk management approach is performing effectively, efficiently, and is still relevant. For this reason, the review activities performed in this workflow should not be viewed as a sequential stage, but instead represented as a continuous activity.

Information gathered during review activities helps organizations to identify opportunities to improve their risk management approach and process to ensure its overall performance remains consistent. To support the activities performed during the review stage, organizations should consider:

• clearly defining the accountabilities, roles, and responsibilities of all stakeholders involved in maintaining the performance of the risk management approach and process

• using existing governance and assurance functions (ie, internal audit) to assess the performance of the risk management approach and process

• documenting the expected outcomes of risk response decisions, such as reducing negative impact or capitalizing on opportunities

• defining key performance indicators (KPI) to measure the performance of the risk management approach and process

• building the necessary systems, processes, etc. to demonstrate the findings relevant to the performance of the risk management approach and process

• establishing a timeline for when and how (1) governance and assurance assessments will be conducted; (2) the outcome decisions will be communicated to stakeholders

Essential to every activity performed during the review stage is the measurement of the overall performance against the overall implementation strategy. Working together with the communication activities, and in parallel to the remaining risk management activities, review activities validate that the risk management approach and process meet the organization’s need by adding value as a contributor to decision-making, business planning, and resource allocation. Where the review activities have identified gaps in the risk management approach and process, such as regulatory compliance or operational efficiencies, actions can be taken to identify opportunities to use more effective approaches, improve processes, or leverage new tools and ideas.

Generally, the documentation and communication of review activities support the organization’s capability to improve its risk management performance through dissemination of best practices and lessons learned. After building the review activities, the risk management mind map can be expanded further to include the specific components of the review stage as illustrated in Figure G.10.

Summary

While there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to performing a risk assessment, the overall goal is to gain a better understanding of the business risk so organizations can identify appropriate strategies, techniques, approaches, or countermeasures to manage the impact. Through the use of any industry-recognized risk assessment methodology, organizations can avoid an overengineered approach of establishing new processes, approaches, or generating loads of paperwork.

Resources

Alberts, C., Dorofee, A., Stevens, J., Woody, C., 2003. Introduction to the OCTAVE Approach. http://resources.sei.cmu.edu/asset_files/UsersGuide/2003_012_001_51556.pdf. Carnegie Mellon University.

Peltier, T.R., 2000. Facilitated Risk Analysis Process (FRAP). http://www.ittoday.info/AIMS/DSM/85-01-21.pdf. CRC Press.

Ionita, D., Hartel, P., 2013. Current Established Risk Assessment Methodologies and Tools. http://doc.utwente.nl/89558/1/%5Btech_report%5D_D_Ionita_-_Current_Established_Risk_Assessment_Methodologies_and_Tools.pdf. University of Twente.