A car drawn by a blind man

The mind gathers up relations and differences from the light the eye catches, referring them to its understanding of forms – that is, of the shapes of solid bodies. That, in essence, was how I described observation in the last chapter. Light – which is what pictures offer the eye – is not form, not three-dimensional shape, but we habitually interpret it in terms of form. In a comparable way, I want to argue, we tend to refer pictures to our understanding of time, the other axis on which our experience of the physical world is organized. Pictures, flat and static things, may thus represent solidity and change. Both form and time, however – especially the latter – make the business of pictorial representation inherently unstable, because there is a multiplicity of ways to infer them from a flat and static surface. I want to explore some of that instability of representation, particularly as it has concerned the recent history of painting.

Form and Bodies

A striking result of research into the psychology of representation has been John M. Kennedy’s demonstration that the totally blind can recognize, and can themselves produce, drawings of familiar objects. People who have no recollection of vision whatever are able, with the aid of upraised lines, to make use of flat representations of the sort we usually call ‘visual’. The man who has drawn the car on page 82 has discovered with his fingers how its surfaces hang together, setting together in a single organization his experiences of touch. That is, he has collated, in a set named ‘car’, some habits of expectation: ‘this will go here, that will go there; when you get to that edge, there will be a gap then something that is evenly curved’; and so on. He has learnt to expect these features through sequences, paths across the object for the fingers to follow; but insofar as cars have a regular design, the features in these sequences all interrelate in a predictable way. The blind man can, if called upon to ‘draw a car’, translate this set of interrelations between edges, protrusions and hollows into tangible markings; markings that the sighted can connect with their vision of a car. The evidence of the eyes is, in effect, simply another way of arriving at this internal model, this configuration of sensations, this idea of the car.

A car drawn by a blind man

Idea = form: the traditional translation used for Plato’s concept, as discussed in chapter 1. Whether we think of form as solid shape, external to us, or as our internal concept of it, it remains something that is opposed to passing sensations, to particles of experience. It is one, they are many. For its part, this passage of sensations is our most immediate experience of time. We are able to think of our bodies as forms because they hold themselves together in a distinctive way against the various sensations we experience. Equally, we can only speak meaningfully of a sequence of sensations because there is a persistent presence against which to set it. Time and form, in fact, emerge together.

They emerge for us from what, on one level, we might term chaos; on another, undifferentiated matter; and on the level that concerns us here, unsorted light – the light, for instance, that enters our eyes the first time we open them in a strange place. An unfamiliar picture – a spread of light before the eyes – can be just such a strange place. We look for clues that will relate what we see to our experience of form and time. As picture-making develops in various traditions, it builds distinctive ways of using marks to suggest these matters. The question of pictorial style is, to a large extent, a question of what methods are used to notate and communicate form and time.

In thinking about form, as I have already suggested, the most familiar unit we refer to is a ‘body’ – a cohesive quantity of matter, whether that matter be animal, vegetable or mineral. One method has been used virtually universally to communicate the presence of bodies: the kind of enclosing line known as a ‘contour’, which suggests the limits within which something extends in 3D. It is what the blind man used for the body of the car, just as any untrained person called upon to draw something would. When a line closes on itself, it defines part of the marked surface as a ‘shape’, something we can think about as a self-contained unit. We thus deal with flat shapes, as well as with the solid forms which they may represent. These flat forms may relate or repeat in patterns or ‘rhythms’ as we scan the surface, and one aspect of painting may be arranging them to do so. If they differ in colour, our eyes may be disposed to see one as standing ‘before’ another, and thus, in many pictorial traditions, scenes featuring bodies will rely entirely on interrelations of line and colour.

Yet since Giotto’s innovations encouraged European painters to simulate the visible world, the contour line and colours that relate flat patterns to solid bodies have regularly been supplemented by shading. Shade, or tonal modelling, firstly confirms and corroborates the sense the contour gives of the body’s volume; the more it is pursued, however, the more it threatens that communication. Chiaroscuro – the concentration on patterns of light and dark at the expense of linear definition, as explored by Caravaggio and Rembrandt – can return vision to formlessness, of the kind, for instance, that seems to loom in the paintings of the 18th-century Austrian Franz Anton Maulbertsch.

There has been one further complication to the European tradition since the 15th century: that the most versatile and subtle tool for simulating visibility was the viscous, varyingly translucent, pressure-registering medium of oil paint. Within the window where the world was to be re-formed, a continuous spread of this sensitive ooze would show itself; and what that spread suggested, as much as it suggested form, were the gestures and exertions of the painter holding the brush. In paintings such as that of Frans Hals, a notation for the form of the represented body is equally a record of the time of the painter’s action. But time is far more inherently unstable, as a matter of visual representation, than form.

Frans Hals, Boy with Skull (detail), c. 1627

Time and Stories

We live with the experience of form and time. But it is much easier to find ways to tell you about the latter than to find ways to show you it. Words, spoken or written, follow one another, and through this coming and going we get some feeling for an order that is not spatial. With conjunctions and past tenses we represent sequence and change.

It is worth noting, however, that we assume that showing is stronger than telling. ‘So you tell me: but how can you show it?’ is the question behind every cross-examination. What is shown will be true, goes the assumption; what is merely told may be false. ‘Evidence’ is etymologically ‘what comes from seeing’, as opposed to mere ‘hearsay’.

A picture or a sculpture, representing a body or several bodies, has a certain enduring form of its own. To accept it as a representation is to accept that this stretch of space has that sort of character. Likewise, we represent time in shapes that have some kind of persistence: stories. To listen to a story is to accept that there was, is, or could be a stretch of time that has a certain character. Changes happened thus. In effect, a story stands to time as a body stands to form: a cohesive unit, grasped from the unrepresentable flux.

While words give shape to stories, it is not only words that bring them to mind. Say we catch sight of some depicted figure – a ‘portrayal’, as defined in chapter 2. Probably most of these that we encounter in daily life, we recognize through their attributes. Attributes – the crown on the monarch, the blue skin of Krishna, the quiff on Tintin – are add-ons to the human form that are literally tell-tale. They key those portrayals into certain familiar narratives. A figure thus becomes a dependable sign pointing to a set of connotations that belong, for instance, to politics, religion or entertainment. Smart cartoonists and designers may strip this sign to a bare minimum: painters may visually enrich it; either way, its connection to story remains structural.

Or say we see a figure depicted on a surface that lacks quite such definite attributes. A child’s drawing on paper, perhaps, or a prehistoric animal charcoaled on a rock. The more that this drawn body turns away from the static, the vertical and symmetrical, the more the paper or rockface starts to become – in the viewer’s imagination and equally, presumably, in the painter’s – a potential space that the figure might inhabit. We begin to imagine what that figure is doing; we reach for some story in our memory with which it might connect. The child prattles some tale about the stick figure, the archaeologist some tale about palaeolithic magic.

The psychology of depiction, therefore, readily interlocks with the psychology of narration. At the same time, these are two differing types of mental activity that overlap. When designers so reduce figures-with-attributes that these become mere ciphers, bearing a meaning that is sequential and interdependent, they create script: that, at any rate, is the gist of many accounts of the origin of writing. Writing and reading, however, depend on mental ordering principles which may not come into play if we are simply staring at a picture, letting our attention linger and rove however we wish.

This reciprocity that is also a tension has been important in shaping the painting tradition we now deal with. Should pictures parallel verbal narratives, or should they attempt clean separation? The question is implicit, I shall argue, whenever people talking about art have used those time-dependent words ‘modernity’ and ‘modernism’ – or for that matter ‘postmodernism’. But to argue this, and to define what it is that the ‘modern’ departs from, I need firstly to analyse more closely the nature of stories.

Relations between marks, things, words and sounds (drawn by the author)

History Painting’s History

Stories, these shapes for time that we put forward, make various sorts of claim on the attention of their recipients. One story, for instance, might state that ‘such and such happened to me yesterday’, or another that ‘these events occurred in this period of time’. Definite, tied-down stories such as these we could describe as reports. Alternately, there are less closely tethered stories which propose that ‘such and such happened to someone once upon a time’, and these we might – using the term as neutrally as possible – describe as myths.

‘Myth’, like ‘story’ itself, always sounds inherently untrustworthy: ‘mere myth’, ‘just a story’. But reports, for that matter, might likewise turn out to be false, when checked against the evidence. And yet it is not only evidence that makes us reach for the word ‘true’. Sometimes we find ourselves agreeing that a myth conveys in metaphorical fashion some general truth about the way things are. There are many possible combinations of these claims about truth and falsity. And this has relevance for the painting of stories in Christendom – the tradition from which the Western fine art tradition very largely sprang.

Master of the Treasure, St Francis and Four Posthumous Miracles, 13th century

The Gospel texts themselves, written a generation or so after Jesus’s lifetime, made report-style claims: ‘It is this disciple who testifies to these things and has written them.’ Such specific reports contributed to creating a story accepted as truthful for humanity in general. By the year 599, when Pope Gregory I defended church images, arguing that ‘what writing provides for readers, a picture provides for the unlettered’, what mattered was painting’s power to convey a mythic truth that Christianity was claiming.

The centrepiece in the ‘gospel for the unlettered’ that Gregory was advocating might be an icon – a portrayal of some holy person, a crucifix or a madonna, on which the worshipper’s eyes might fix. This icon, asking for contemplative attention, might present a figure with attributes within a more or less static, self-enclosed design. But complementing the icon were subordinate pictures that got the eyes shuttling left and right, because they represented the action sequences of the Gospels – the stories, typically, of Jesus’s birth, passion, death and resurrection.

Giotto, Resurrection (Noli me tangere), 1306

It was Giotto, more than anyone, who demonstrated the huge emotional dynamism these narrative pictures could have, when he frescoed the Arena Chapel in Padua between 1303 and 1306 with thirty-seven episodes in the stories of Mary and Jesus. Each of these dramatizes a particular, crucial moment while suggesting what led up to and away from it. The general truth of myth is reinvigorated by a quality of immediate report: while the protagonists may be dignified by grand sweeping robes rather than everyday dress, their gestures and stances feel directly witnessed. Writing a century onwards from Giotto, Alberti took the story painting – the historia – to have become the most challenging task a painter could face, since it demanded expertise in representing all manner of things and in organizing them all into a readable storytelling design. Following literary prototypes, he termed this a ‘composition’.

The more that discussion turned on painters and their art, rather than on religious worship per se, the more it turned on the historia. In the course of the Renaissance this representation of persons dramatically interacting became the most ambition-laden of pictorial genres. It became a secondary question, therefore, whether the contents of painted stories were the permanent essential truths of Christianity or the fictions of pagan classical ‘mythology’. Occasionally pagan mythologies might approach the status of myths – that is to say, of narrative reflections on the forces that govern the world. For instance Titian in his 1550s Diana and Actaeon paintings pondered sexual division, imagining a female otherness that excites yet endangers males. Calling such canvases poesie, Titian was again conforming to literary models. The motto of the ancient Roman poet Horace, ut pictura poesis (‘as in painting so in poetry’), had become a catchphrase for both arts, defining each reciprocally.

Titian, Diana and Actaeon, 1556–9

But whether mythologies or Christian stories were to carry a status of eyewitness report became more or less a matter of discretion for the artist and patron. Titian’s paintings demonstrate the attractions of once-upon-a-time-ishness – his figures, whether Jesus, Adonis, Mary Magdalen or Venus, belong to an indefinite antiquity which licensed liberally bared flesh and gorgeously coloured robes. Around 1600, Caravaggio resuscitated the claim that ‘I saw it happen with my own eyes: these people in the Gospels could be the very people living on my street today.’ A generation later, Poussin, by contrast, began to be interested in what we would now call historical accuracy. He told Gospel stories in costumes and in settings that he believed might be plausible for the ancient Roman imperial provinces of Palestine and Egypt.

Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family in Egypt, 1655–7

As of the mid-17th century, this attention to period detail was a relatively refined side issue for aspirants to ‘history painting’, as English writers termed the art of the historia. Scientific attitudes as we know them now were only just emerging. But move to 1770 and values are seen to change. That year a row broke out in London over Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe, painted to glorify an episode in the British conquest of Quebec in 1759. What Joshua Reynolds, as President of the Royal Academy, objected to was West’s introduction of contemporary costumes into a story of edifying heroism. Reynolds argued that history painting’s strength lay in its ability to tell morally encouraging stories without the limitations of language. It could speak to the eyes universally across the barriers of dialect, if it kept to the natural language of nudity and the general language of classical drapery. Contemporary meant specific and local, and therefore resulted in a loss of painting’s inherent advantages over verbal communication.

Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe, 1770

West replied that no one had ever been seen wearing togas in Canada, and that ‘the same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil [that is, the brush] of the painter’. History painting, in other words, was to be governed by history writing. The world, through the efforts of 18th-century historians, scientists and encyclopaedists, could be thought of, as never before, as a seamless structure of ascertainable fact. If everything in the world could take its place as a fact in an encyclopaedia, it followed that every detail had its own appointed period identity. The proper place of the toga was in classical Rome, and the proper details for Canada in 1759 were redjacket uniforms and redskin feathers.

Every image, then, must first of all be circumstantial and local – a report. Classical Roman dress and architecture became archaeologically specific, as never before, in the ‘neoclassical’ paintings of the later 18th century – culminating in David’s Oath of the Horatii of 1784. Yet the way that that violent image inspired copycat poses and costumes during the soon-to-follow French Revolution showed how then and now might interact, generating larger resonances. From an art world point of view, Christianity was becoming then. Much as the grouping of the expiring General Wolfe and his grief-stricken comrades was meant to remind viewers of a traditional Lamentation, martyr imagery from former centuries was deliberately evoked in the most powerful painted reports of recent events during the revolutionary era – David’s Death of Marat, Goya’s 3 May 1808. Painting another news story in 1819, Géricault brought Michelangelo and Rubens on board his Raft of the Medusa, the extreme conditions and near-nudity experienced by its crew allowing him to reanimate the figure language of their visions of damnation. But back on dry land, the Renaissance had become a period apart: a foreign country.

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1819

Beauty and Modernity

While ‘historical painting’ – history painting overseen by period consciousness – was thus emerging, the foregoing high tradition was also subjected to a more radical reappraisal. In his 1766 essay Laocoon, the German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing analysed the relationship of painting and poetry, taking it back to first principles:

Objects which exist side by side, or whose parts so exist, are called bodies. It follows that bodies with their visible properties are the proper subjects of painting.

Objects which succeed each other, or whose parts succeed each other in time, are called actions. It follows that actions are the proper subjects of poetry.

Lessing went on to speculate that ‘The true end of a fine art can only be that which it is capable of arriving at without the help of any other. In painting, this is bodily beauty.’ History painting had come into being, Lessing argued, not in order to tell stories but simply as a way of creating ‘variegated beauty’.

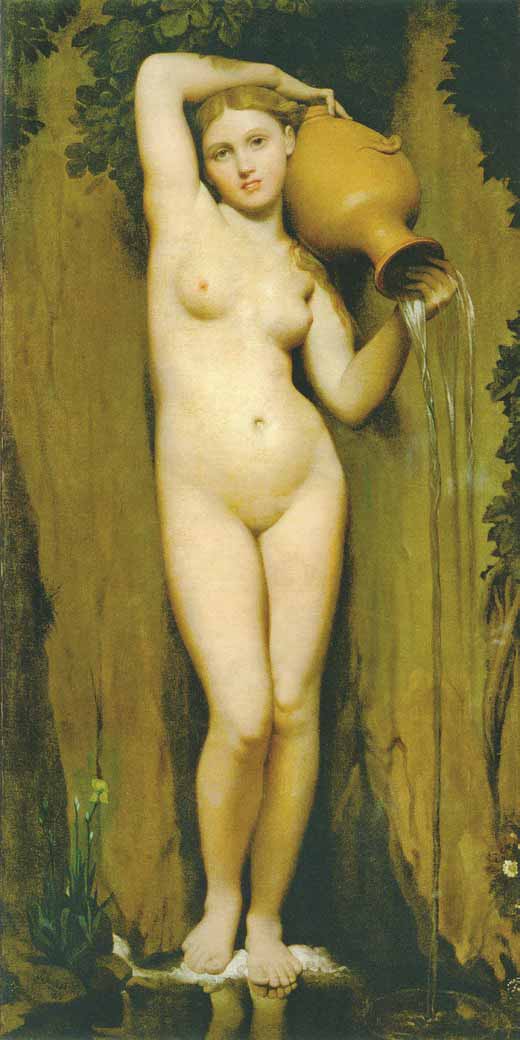

Within Lessing’s new framework of values, the painter’s quest for beauty might be just as well served by a genre such as still life: or it might be demonstrated by an image as semi-detached from narrative as Ingres’s The Source. Like a medieval madonna, The Source stills your roving attention and invites your gaze to linger – but on bodily perfection, rather than on heavenly mercy. Maybe we could call this latter-day variant on an icon an ‘eye-rest’.

Paintings of this kind became the 19th century’s idea of ‘classicism’: a cult of self-contained, self-involved beauty given subsequent inflections by ‘Aesthetic Movement’ artists such as Frederic Leighton or James Whistler. Eye-rests shared gallery space with the busy pictorial dynamos known as grandes machines – vehicles for 19th-century ambitions to deliver narrative. By 1856, when Ingres exhibited The Source, this latter genre of painting was dominated by the primacy of fact. In the ‘licked surface’ of Paul Delaroche’s historical melodramas, or in the exhaustive exactitude of William Holman Hunt’s biblical scenes, past worlds were reconstructed punctiliously, and as far as possible flawlessly: seamless detail matched by seamless brushwork. ‘The historical sense dates from only yesterday, and it may well be the best thing the 19th century has to offer,’ wrote Gustave Flaubert in 1860.

Historical paintings could certainly claim to stand as reports – as research reports, at least. How far could they lay claim to poetic, general truths? Delacroix, defiantly preferring older ideas of history painting, was dismayed by his contemporaries’ ‘attempt to render everything’ so that ‘the ensemble disappears, drowned in the details’, leaving the imagination deprived. But perhaps hopes of mythic generality had to be abandoned. ‘I hold the artists of one century basically incapable of reproducing the aspect of a past or future century,’ Courbet told some of his would-be disciples. ‘Each epoch must have its artists who express it and reproduce it for the future.’

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Source, 1856

Invoking the ‘epoch’ in this way, Courbet was falling in with the prevailing ‘historicism’ – the attitude that sets historical context over and above any permanent human condition. He did so as a positivist who believed that ‘painting can only consist of the representation of real and existing things’ and that his still lives and nudes, being painted from life, could speak as well for the age as his Stonebreakers. But when Courbet voiced these opinions in 1861, his former friend Baudelaire had just drafted an argument about painting and temporality that would have an impact on the art world at least the equal of Lessing’s.

The Painter of Modern Life (composed in 1859) starts with Baudelaire paying respect to the principle of ideal beauty. Traditionally, as we have seen in chapter 1, artists reached for the ideal by means of imitating nature. But inventively and provocatively, Baudelaire now made nature the villain of his argument. Nature ‘teaches us nothing’, for whatever is animal in us is dumb and rapacious. ‘Virtue, on the other hand, is artificial.’ The ideal, the imaginative and the rational (qualities Baudelaire aligned together) thrive the more that art and civilization are able to overcome nature. In fact they throve most of all, Baudelaire posited, in the modern metropolis: in the Paris immediately around him.

Yes, that city was a delirium of crowds, carriages, gaslight, parks, cafés, brothels and extravagant and fast-changing female fashions. All these presented exactly the conditions in which beauty was to be sought, for Baudelaire argued that the eternal and ideal must always have one foot in the ephemeral. And setting out to find that beauty, Baudelaire introduced a character that he named as ‘the painter of modern life’. This individual was ‘strange’ and ‘original’, yet purposeful: a master of ‘being sincere without being absurd’. More than a mere stroller (flâneur), he registered the crowd passing around him on the boulevard and ‘wanted to marry’ it through the art he would create. By the same token, he was not of that crowd. He was its ‘mirror’: ‘an “I” with an insatiable appetite for the “non-I”’. Detached and singular, his consciousness complemented ‘the fugitive, fleeting beauty of present-day life…that quality which you must allow me to call “modernity”’.

And thus Baudelaire settled on what would become the most heavily laden of all words in art discourse between his time and the present. The term ‘modern’ is itself hardly modern: Dante could speak of ‘modern’ styles in poetry, way back in Giotto’s day. A certain proportion of paintings in any historical period has inevitably recorded the style of other artefacts – clothes, buildings, devices – during that period, often with a will to celebrate it, and in that broad sense, there has always been ‘modern’ painting. In Baudelaire’s century, James Nasmyth’s 1871 painting of the ‘the steam hammer’, the invention he himself patented in 1842, was just such an image. From his own personal experience, Nasmyth found a new pictorial charge in the anonymity, the stark geometry and the sharp dazzle of the industrial forge.

Here was a Scottish engineer celebrating his own part in the transformation of material conditions, devising a machine that would speed the construction of other mighty machines such as steamboats. Almost everyone across the globe, as of the mid-19th century, could agree that Nasmyth’s achievement was characteristic of the current age. Those who were optimists could also hail this as ‘progress’: scientific technology lifting humanity from naked dependence on the soil to a more efficient and rational mode of existence. That much was a creed accepted both by Marx and Engels and by the capitalists described in their 1848 Communist Manifesto. It was the two revolutionaries who coined the most memorable image for this modernity’s constantly accelerating transformations: ‘All that is solid melts into air.’

James Nasmyth, Nasmyth’s Steam Hammer at Work, 1871

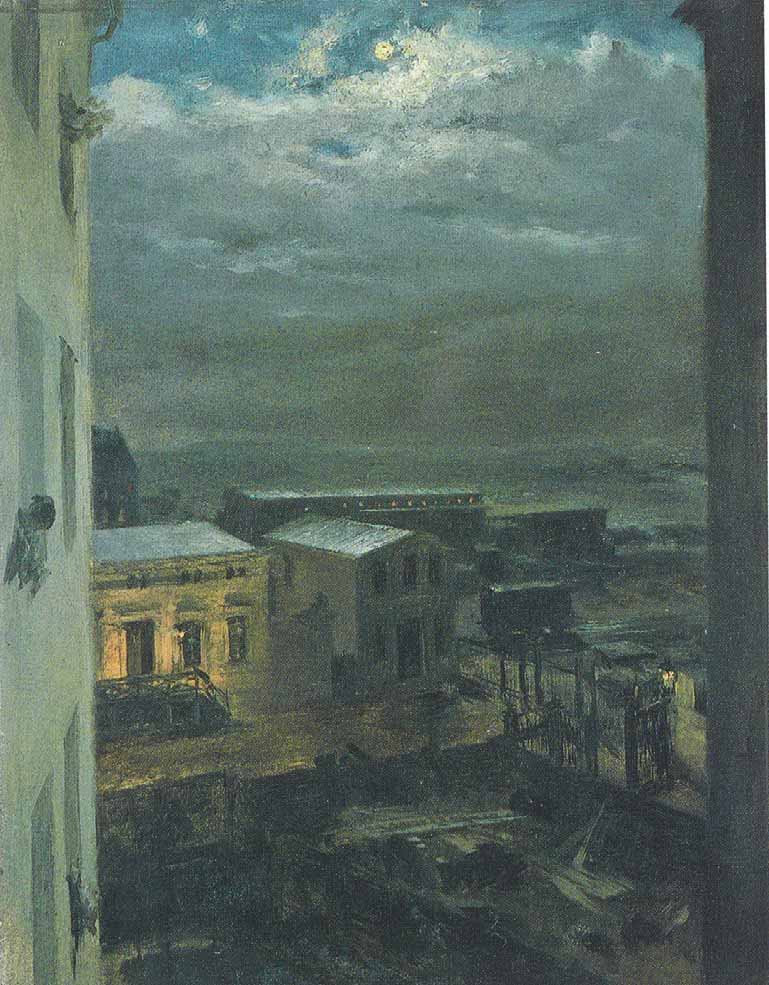

It might also be said that Adolph Menzel, painting the Berlin railway station at night in 1846, was finding a ‘modern’ pictorial poetry. But there is a rather different sense in which Menzel ‘feels modern’ here. It is the eccentricity, the originality of his viewpoint; he has not fallen in with the angles of approach expected by the designers of these buildings, or by the traditions of townscape painting – he has seen for himself. If we call this ‘modern’ today, it is because we associate the modern with a detachment from all fore-ordained ties. To look down, floating and apart, like a bird, from a high window – the experience of the city high-rise, and later of the aeroplane – is one of the freedoms that have made up our image of ‘modernity’.

Adolph Menzel, View over Anhalt Station by Moonlight, c. 1846

These connotations arise out of a tangle of meanings in which many of the threads are Baudelaire’s. Nominally, his essay’s protagonist was the Parisian illustrator Constantin Guys, whose pen-and-wash sketches now seem frail vessels for such forceful thought; but by 1863, when The Painter of Modern Life got published, art world attention was settling on another acquaintance of Baudelaire’s, Edouard Manet. It was Manet above all who became associated with that titular identity. 1863 was the year in which his Déjeuner sur l’herbe was exhibited in Paris, to be followed two years later by the still more controversial Olympia. These two, the most talked about paintings of the 19th century, were each at once confrontationally powerful and laconically indefinite in intention.

Manet had been reading Baudelaire on the modern beauty of brothels, in which, ‘quite by chance’, the girls ‘achieve poses of a daring and nobility to enchant the most sensitive of sculptors’, and he conceived canvases in which prostitutes would replicate Renaissance compositions. But going beyond this, he fixed on Victorine Meurent – the young woman he hired to pose in both – an attention that was urgent and empathetic, and this empathy became a kind of complicity. Meurent’s bold challenge – ‘Who is looking at me? For whom am I doing what?’ – became a questioning that ran through the brushwork, with its disconcerting veers from luxuriant to brusque to dismissive.

The crowds visiting the 1860s exhibitions were thrown by the results on all levels. If prostitution was to be depicted at all, feelings ran, it should not be this way. Manet, though himself full of ‘daring’ and determined to be ‘sincere’, had not positively wished to offend, and the reactions puzzled him. But for fellow independent artists, they cemented his status as that loner, opposed to the crowd, whom Baudelaire had commended as modernity’s interpreter. And while Baudelaire himself, with his sceptical view of human nature, was no believer in progress, a ‘painter of modern life’ must surely be culturally positioned adjacently to ‘the avant-garde’, that self-appointed small band of enlightened agents that was just starting to shape up, the artistic front-runners of humanity’s progress towards a better future.

Here, then, is the knot of meanings that entwined itself in the later 19th century around the word ‘modern’. There were at least two accounts of modern content for paintings:

the look of the industrial and mechanical;

the look distinctive to artifice, entertainment and transience;

and at least two accounts of a modern attitude in painting:

to engage ever more rationally with fact and concrete reality;

to stand detached, observing an unreal and transient environment.

Artists could avail themselves at will of this potent complex of ideas. Menzel in Berlin looked hard at industry while maintaining an off-centre, idiosyncratic detachment; Paris artists revelled in the transient world of leisure, sometimes (witness Seurat) treating it as matter for remorselessly rational analysis. The commercially unsuccessful artist might console himself with the thought that his enforced detachment from public acceptance was a register of his superior grasp of reality. From all kinds of angles, ‘modern’ was becoming a quality to reach for.

Modernist Time

Reaching for the modern, painters dropped storytelling. That has become a consensus view of ‘modernist painting’ – a loose but useful retrospective label to cover a host of artistic developments between the 1880s and the 1960s, when the yearning to be ‘modern’ most distinctly held sway. Before considering if there are limitations to this received wisdom, let us consider the many ways in which it holds true.

‘All that is solid melts into air.’ Firstly, we could extend Marx’s famous image. Modernity, this new-arrived quality of time, was no more to be shaped than vapour. Stories, insofar as they were containers for time, couldn’t possibly satisfy a painter attuned to the modern. Rather, such a painter, gifted with ‘the most advanced eye in human evolution’ would make it his business to render a ‘living atmosphere of forms, decomposed, refracted, reflected by beings and things, in incessant vibration’. The words are Jules Laforgue’s in 1883, formulating what he took to be a rationale for Impressionism and adding a quasi-Darwinian accent to the themes of atmosphere and sensibility already discussed in chapter 2. The mere experience of fifteen minutes of daylight would bombard this painter’s eye with ‘infinite changes’ which he could only interpret through ‘a thousand little dancing strokes in every direction like straws of colour’. (Laforgue had been looking at Monet.) Logically, line and perspective would be superseded, once all was colour vibration. But even if these proved hard to outlaw, the temporal plane of narrative was surely incompatible with that of advanced modern vision.

Secondly, to extend this line of thought: if a quarter of an hour’s vision led to overload, perhaps it was a moment’s glimpse that best gave the measure of modern vapour. Could painters, whose handiwork can rarely be instantaneous, arrive at such a quality of snatched vision? Degas did. His At the Café (c. 1875) doesn’t tell a sad story: it overhears one. The café of the title is, the viewer intuits, a modern metropolitan space, in which private intimacies happen to collide: but it is not presented through a perspectival window. Degas would later speak of depicting women washing themselves ‘as if you looked through a keyhole’.

We might look at such a painting now, or later analogues, say by Toulouse-Lautrec, and think: this cropping has been prompted by snapshots. But it follows from what I have been saying in chapter 2 that photography in the first place was more a symptom than a cause of changes in picture-making. Before the Kodak company mass-marketed cameras in the 1890s, photographers tended to compose their shots like pictorial compositions, so as to present information in an orderly manner; the ‘arbitrary’ look of the snapshot, the grabbed glimpse, had yet to be exploited by them. Degas possessed par excellence the type of ‘strange’ and ‘original’ artistic consciousness that Baudelaire had wished upon the modern painter. Possibly he took note of the work of other experimenters with cropping – Hiroshige, Menzel; possibly not. It is true, however, that from 1900 onwards the camera became an obvious medium for such a take on modernity.

Edgar Degas, At the Café, c. 1877

Multiply momentary glimpses and you get a sequence of images. Degas’s later drawings of dancers are sometimes organized in long strip sequences, so as to create horizontal rhythms in the manner of Chinese handscroll paintings. Meanwhile, Monet, exploring in colour the passage of a day’s sunlight over the façade of Rouen Cathedral, or over haystacks, asked the viewer to scan a multiplicity of canvases. To these artists, the challenge of the grande machine – to compact a passage of time into a single rectangular composition – was no longer interesting. Instead, structured arrays of many images might bring painting closer to music, this being a frequent yearning for artists overawed by Wagner’s vast, engulfing operas.

Edgar Degas, Frieze of Dancers, 1895

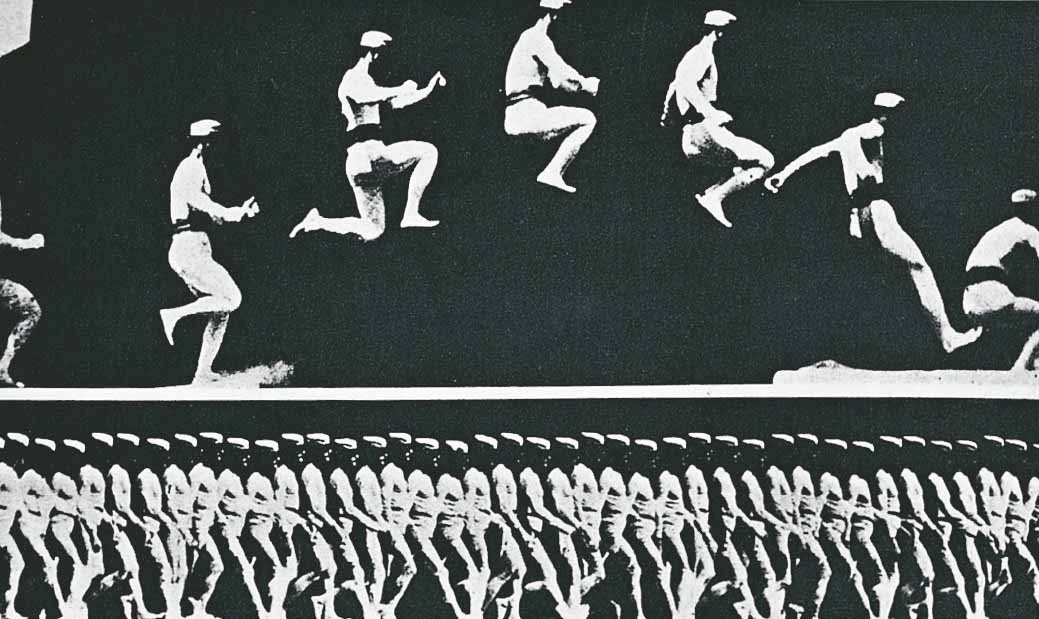

Concurrently, during the 1880s, Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey were demonstrating the remarkable new analyses of bodily movement made possible by sequences of time-lapse photographs. Their high-speed camera mechanisms led the way for the development of simple forms of ‘moving pictures’ during the following decade. By around 1910, the fast-expanding medium of cinema was inviting in all the melodramatic narrative and detail-rich historical scene-setting that had made the grandes machines so popular during the 19th century. Artists in pursuit of the modern doubted that painting had any further place for those ingredients.

Come 1912, however, we find the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla recompressing a time-lapse sequence of body movements into an upright rectangle. Why now, three decades after Marey? As we saw in chapter 2, from the turn of the 20th century, painters increasingly became convinced that the direction for their art had been pioneered by Cézanne. The old Provençal, with his uncompromising interrogation of how objects and marks related, was hailed as an apostle of a rationality fit to steer painting away from Impressionist flux.

His achievements prompted Braque and Picasso to focus their enquiries on still-life subjects. Their Cubist art was often keyed to the present day by allusive attributes of the modern such as newspaper headlines, but it wholly conformed to Lessing’s aesthetic logic: it was all bodies, no actions. Meanwhile, Cézanne’s Bathers – groupings of bodies set in a mythic, nonspecific idyll – inspired the Matisse who painted such majestically self-enclosed compositions of the 1900s as Le Bonheur de Vivre and The Dance, and who in 1908 wrote that:

Étienne-Jules Marey, Cinémathèque, 1880s

Giacomo Balla, Girl Running on a Balcony, 1912

What I dream of is an art of balance, purity, tranquillity, without an anxious or disturbing subject, which for anyone doing brain work – the businessman as well as the literary artist – would act as a relaxant, a cerebral balm, something comparable to a good armchair that eases his bodily fatigue.

Matisse’s 20th-century version of the eye-rest had, therefore, an explicit relation to contemporary life – it was meant to act as its counterweight. Modernity accelerated the brain. Modernism, Matisse-style, slowed it down. It did so by concentration on the persistent, underlying factors in vision – powerfully isolated lines and spreads of colour, interlocking to suggest bodies and create resolved visual rhythms. With its toughly argued drawing and its simplifications of body appearance, here was an art par excellence of form.

Balla, at work in Milan, was alert to the turns taken by Paris painting, but at the same time he and his fellow Futurists were devoted to the outward look of modernity – electric lighting, automobiles and film. They wanted to access what moving images had to offer and reclaim it for the still image, compressing new-technology information into a rectangle of paint on which the eye could settle. Girl Running on a Balcony is an awkward trade-off, perhaps, between two contrasting ideas of ‘the modern’, but such trade-offs would reappear regularly in 20th-century painting.

Instant cameras and the movies weren’t the only challenges to painting for artists who aimed to look the 20th century in the eye. For Baudelaire, modernity might have meant passing shows, but from 1914 it meant push-and-shove: the world that artists inhabited was becoming cataclysmically political. Inescapably so, for artists caught up in the Russian Revolution. If, after 1917, the agenda facing all citizens of the emergent Soviet Union was society’s transformation, would painting be able to contribute?

On the one hand, the Russian artist El Lissitzky argued that painting, making use of basic forms, could combine them in fresh ways so as to expand the total public imaginative space. This was the logic of his 1920s series of works acronymically entitled ProUNs – roughly, Projects to Underpin the New. The ‘new’ at the end of the process might be some kind of construction put to people’s service, contributing to a future utopia: thus painting was a speculative stepping stone, on the route to something beyond itself. Another wing of Russia’s Constructivist movement, however, broke as a matter of principle with the practice of painting. For Alexandr Rodchenko and the critic Osip Brik, canvases – flat and static repositories of value – were obsolete. To stand still and look at a painting is not to progress. For Brik:

Henri Matisse, Dance, 1910

All attempts to turn an easel painting into an agitational picture have been fruitless. And this was not because there was no talented artist around, but because this is essentially inconceivable…A subject of short-term efficacy cannot be processed by devices calculated to last a long time. A one-day show cannot be put on for centuries.

Brik wanted to redirect artistic talent towards textile-printing. Likewise, Rodchenko dropped easel portraiture for the camera. Someone criticized him because the latter recorded ‘a chance moment, whereas a painted portrait is the sum total of moments observed’. Exactly, said Rodchenko, a man changes: ‘a man is not just one sum total; he is many, and sometimes they are quite opposed’. Moment and sequence, snapshot and film, were in this light more truthful modes of representation than painting, which is never the work of a moment.

El Lissitzky, ProUN: Interpenetrating Planes, 1919–20

But for many who thought about painting in less politicized contexts, representation was not anyway its objective. Early 20th-century British critics such as Roger Fry and Clive Bell advocated a ‘formalism’ more or less consonant with Matisse’s pronouncements, rejecting any claims that a painting could be valued for its narrative content. The notion that painting might be pure eye-rest, exclusively concerned with and addressed to the sense of sight, became prominent again in mid-20th-century America, promoted by the critic Clement Greenberg (to whom I’ll return in chapter 5). But an ambivalence regularly clung to the work being discussed. If you could make formalist claims for the canvases of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, you might also claim – as a rival critic, Harold Rosenberg, did in 1952 – that these constituted ‘Action Painting’:

Jackson Pollock painting No. 32, 1950

A painting that is an act is inseparable from the biography of the artist. The painting itself is a ‘moment’ in the adulterated mixture of his life – whether ‘moment’ means the actual minutes taken up with spotting the canvas or the entire duration of a lucid drama conducted in sign language. The act-painting is of the same metaphysical substance as the artist’s existence. The new painting has broken down every distinction between art and life.

Here, for an American culture that set much store on ‘drama’ and ‘biography’, was a fresh way to think of paintings as embodiments of time – though in a rhetoric that pointed a way out from painting per se. No distinction between art and life: Robert Rauschenberg took that abolition of boundaries as a cue to expand from 2D work into 3D and dance; Allan Kaprow as a cue to leave painting behind altogether, in favour of the transient, participatory events he called ‘Happenings’. From the 1960s, performance art (and alongside it, video) joined architectural projects, cinema and photography as possibilities beyond painting, enabling ambitious artists to explore time otherwise. Of the onetime standard-bearer for ambitious art, the ‘history painting’, you might think that neither the history nor the painting remained.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937

Postmodernism and Myth

But that would be to distort the record. One of the best known and most widely admired paintings of the entire ‘modernist’ period between 1880 and 1960 is a history painting: Guernica. And when Picasso painted this massive canvas in 1937, he was falling in, at an acutely politicized moment, with broader currents of narrative painting that were coursing between the 1920s and the 1940s. Some familiar examples would be the mural projects started by Diego Rivera in Mexico in 1920, an inspiration to many artists in the United States during the 1930s; the ways that Max Beckmann and Otto Dix responded to Germany’s catharses after World War One; or the highly dramatic narratives imagined in 1940s Australia by Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd.

Guernica is pre-eminent because it hits all buttons at once. It commands respect in purely formal terms for a pictorial structure that is at once rigorous and enormously complex. At the same time it is momentous storytelling. Unveiled at an international exhibition on 12 July 1937, it speaks of what had actually happened to a Basque town when attacked from the air by Fascists on 27 April that year. It does so through imagery that universalizes the atrocity, suggesting that its roots lie deep in human history and psychology. In Guernica, report becomes myth.

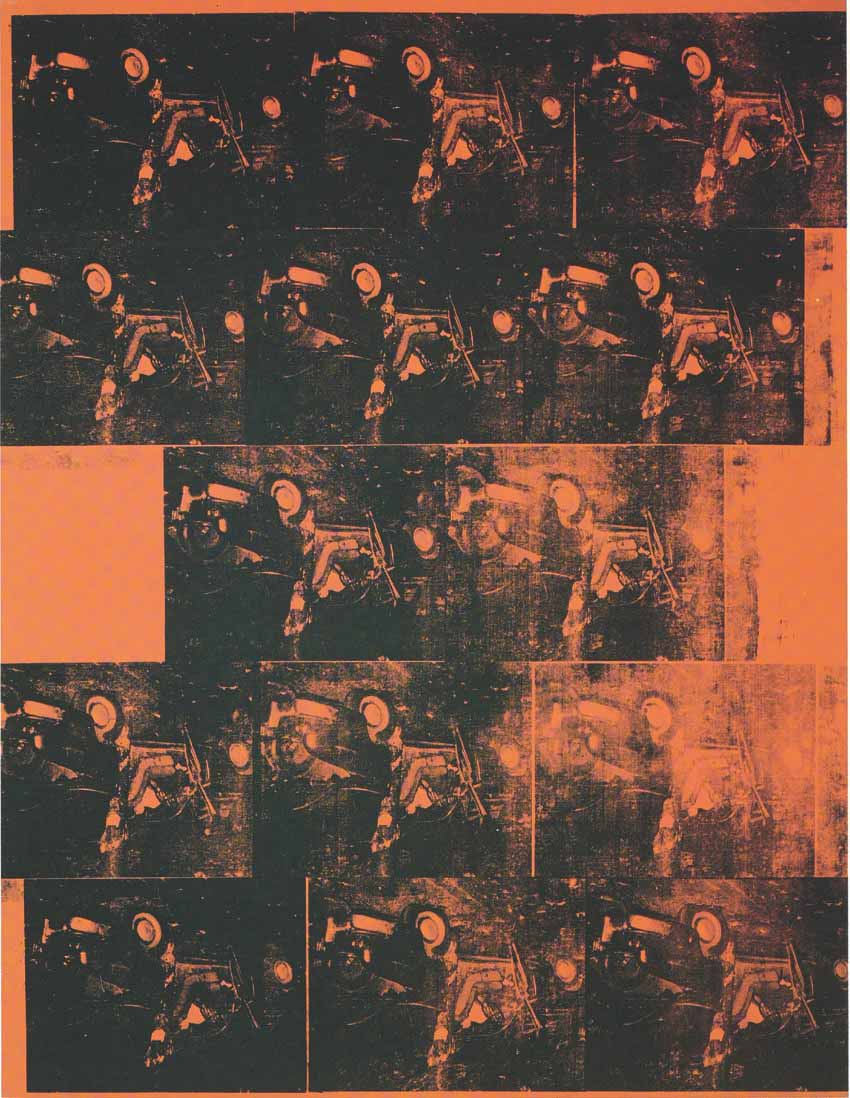

That longstanding interrelation between report and myth can, I would argue, help us understand what was at stake some 25 years onwards, in a very different historical situation. No critical orthodoxy can hold down painters too long, and many began to question, from the early 1960s onwards, the kind of modernism that insisted their art should be concerned with nothing but form. Pop Art, as launched by Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol in 1962, accepted the need to deliver big rectangles of paint that had intuitive sensory impact, just as Matisse’s had: it had learnt its formalist lessons. But tersely, it reintroduced a modicum of content, consisting of a modernity that a broad public would recognize, that of commercial America and its communal dreams. Comic-strip excerpts keyed viewers into the kinds of stories known by everyone. Portrayals with attributes, as I termed them earlier, tapped mass psychology.

Andy Warhol, Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times, 1963

Warhol’s Marilyns – at once icons and eye blasts – made their impact, like his soup cans and Coke bottles, by multiplication. He tried out this strategy also when thinking about communal nightmares. ‘It actually happened. It actually happened. It actually happened,’ his Car Crash and Electric Chair paintings of 1963 keep telling us. The blunt reiteration kicks hard at psychological fault lines, as if to set up the factual report as a sort of myth about mortality in general. Things do happen: people do die, in hideous tangles of machinery and flesh; that’s how it is; a painting can attest to that truth.

Gerhard Richter, Man Shot Down 1, from October 18, 1977 series, 1988

The approach to the medium was inevitably different when it came to another influential figure for late-20th-century painting, Gerhard Richter. Different also was the nature of the communal agony to which Richter referred in his series about the end of the Baader-Meinhof gang, October 18, 1977. Richter liked to dwell on the way that paint itself could be indeterminate, taking away normal significance even from an event as loaded as the deaths in prison of his nation’s most famous terrorists. For both Warhol and Richter, however, photographs taken for the record supplied an emotional hinge. They set us on an edge between witnessing something and never being able to enter the experience – an edge that might run through any representation of death or of how we might feel about it.

This emotional hinge is also a pivot on which image categories are poised. In work such as Richter’s (often hailed as ‘photo-painting’ – not necessarily the same as ‘photo-realist painting’, which might mean photos transcribed for the sheer appeal of their texture), the mechanical image – which, when first invented, seemed to challenge the handmade – eventually lent the latter a kind of legitimacy. A non-artistic snapshot providing not wholly adequate evidence became, once turned into paint, an artistic statement about the limits of art: from ‘you can’t quite see it’ to ‘paint can’t quite show it’. With that proposal, the painter offered a resignation – ‘I’m sorry, but these days paintings can no longer offer what you hoped that paintings would offer’ – that was also a request to stay put – ‘You can trust me though, because I’m frank about it.’

Luc Tuymans, Gaskamer (Gas Chamber), 1986

The paintings of Luc Tuymans, often based on photos obliquely witnessing terrible passages from modern history, performed this kind of balancing act from the 1980s onwards, their wan brushwork and predominantly modest scale exhaling rueful, self-referential sighs. The thought that 20th-century horrors – specifically, the Auschwitz concentration camp – placed all forms of artistic representation in a state of inadequacy had been originally voiced by the philosopher Theodor Adorno in 1949. Painters only began to find a use for the sentiment decades later, at a point when their own medium had been under sustained challenge from the already mentioned alternatives of video and artistic photography, both of which seemed better able to report on the real world.

That tactical pessimism was one possible modus operandi for the ‘postmodernist’ painter – to touch on an epithet that has been tugged in multiple directions. For many commentators, the modernism to which postmodernism was post was the ethos that reigned from the 1860s to the 1960s and that supposedly expelled history painting in favour of formalism. If it was now too late to believe in that scheme of artistic values, it became highly acceptable, from the late 1970s onwards, to return not to factual reporting but to once-upon-a-time-ishness, the other mode in which storytelling occurs. For another thing that postmodernism entailed was a splurge on myth.

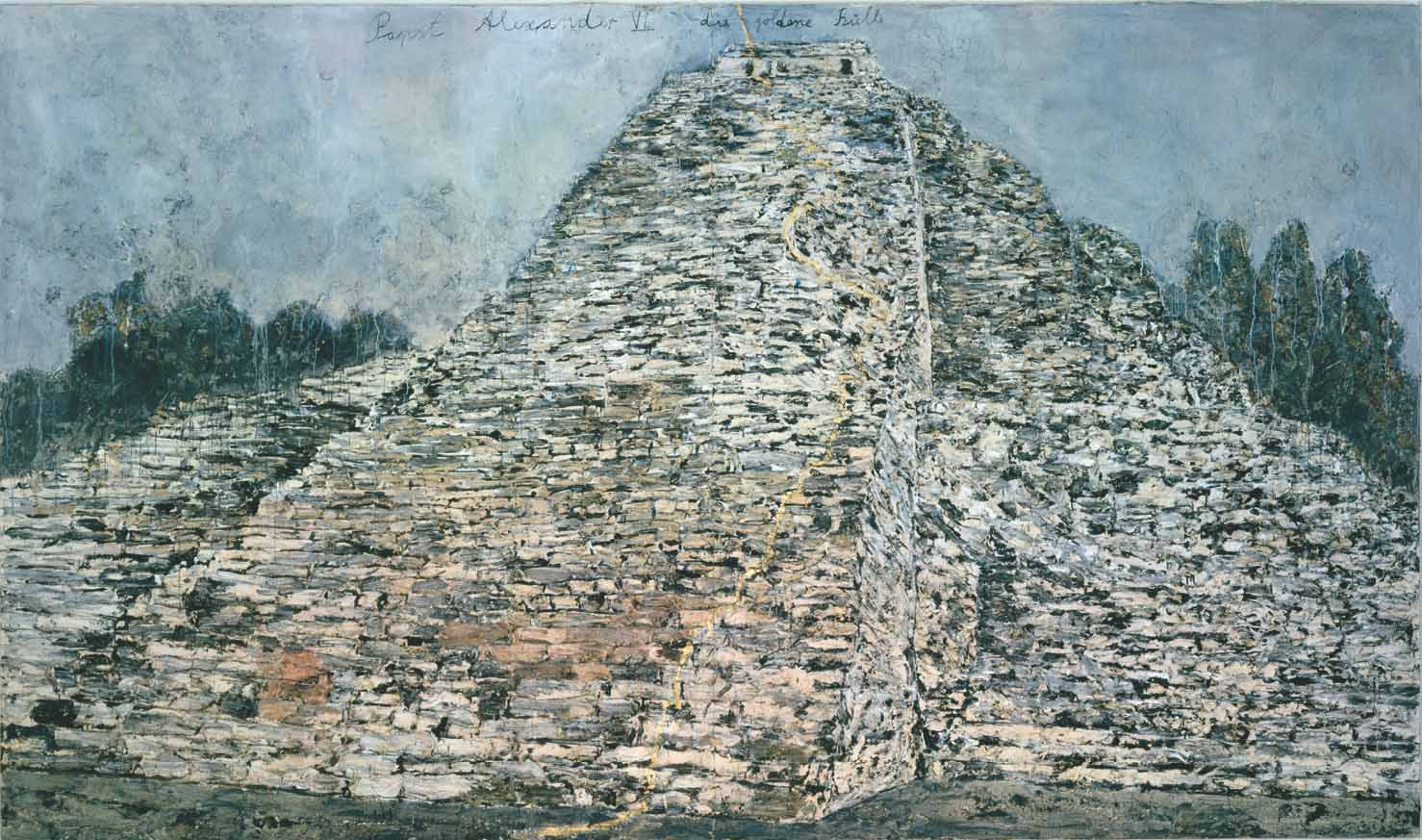

Anselm Kiefer, Alexander VI, 1996

This category of myth is of its nature as capacious as postmodernism itself. Indeed, although the interpreters of Abstract Expressionism, Greenberg and Rosenberg, rather ignored the fact, this group of painters liked to think they were giving voice to ‘myth’ – understood as lofty, metaphorical truths about the human condition. In this regard Anselm Kiefer was the postmodernist heir to their ambitions, much as he inherited the epic scale of Pollock’s and Newman’s canvases: for in Kiefer’s view, ‘Mythology is the only way you can try and understand the connections in the world. Science can’t do that.’ Their paintings deployed gestures on flat planes: Kiefer’s deployed symbols (plants, bricks, artists’ palettes, etc.) in perspectival space; both, though, aimed for a time-transcending generality. Both grandiose and ruinous, Kiefer’s artworks set everything in an eternally recurring past – ‘This is how it forever was’ – even when the pretext happened to be some event in recent history.

The mythologies referred to – kabbalism, for instance – were consciously arcane. Late-20th-century taste revelled in mystification, not only from Kiefer but also when it came to the spectacular novelties produced by Australia’s Aboriginal painters. The acrylic-and-hardboard commodities they started producing from 1971, putting forward symbols formerly meant for esoteric ritual, gained a market niche by underpinning extravagantly rich surfaces with promises of narrative meaning. The pictograms around which Pansy Napangati wove her patterns referred to a story about a dangerous waterhole. However little this story’s contents signified to any purchaser, it was good that there be a story, and its very distance from contemporary relevance lent it charm.

Pansy Napangati, Untitled, 1989

Julie Mehretu, Black City, 2007

Neo Rauch, Heillichtung, 2014

That, no doubt, is one of the ways in which we find ourselves drawn to old pictures. How much does the feeling recur in the case of contemporary ones? For instance, those drawn to the visual language of Julie Mehretu – as enticing and nearly as codified as Napangati’s – may like to hear that it symbolizes certain movements and events in recent history. But is belief in that symbolism perhaps confined to the artist? Neo Rauch, who paints baffling dream narratives featuring ominous excerpts from Middle European melodrama, joins earlier ‘postmodern’ artists (Sigmar Polke, for instance) in being saluted as a mythic prophet of knowledge-saturated world-weariness. The New York critic Peter Schjeldahl has winningly advanced this point of view:

Today, we are flooded with accurate information…and we naturally feel that such clarity must influence events, but it only amplifies our dismay as the world careers from one readily foreseeable disaster to another. Rauch sets us an example of getting used to it…Present-day reality is a lot more like one of his pictures than I wish it were.

You might, though, just as well read Rauch as an aesthete who preserves the integrity of his fantasies by refusing to refer to anything historically specific. I suggest that in the case of many contemporary painters, myth – with its open-as-possible claim on truth – serves as a pretext for essentially formal interests. Which is to say, an ambition to make paintings so radiantly and startlingly complete that they have no need to lean on external claims to truth. But this is an inarticulate ambition. Even abstract painters, as of the 2010s, tend to couch their practice in wry historical self-awareness: for all the internal fascination of Tomma Abts’s little canvases, there is an inbuilt sense that they play out a game that is half-absurd. It is not that beautiful paintings can’t now be made. It is that we’re not sure how to speak of their beauty.

Tomma Abts, Oke, 2013