Fortune befriends the bold.

—Emily Dickinson

Societies are fascinating to me. Just think about it: we as the human race, composed of more than 7 billion people, have become surprisingly organized in how we live. We have cordoned off the world into continents, then into countries, and further into local municipalities. We have wired up our communities with plumbing, electricity, and sanitation, which is becoming increasingly available around the world.

We have formed into governments, who have levied taxes and laws to fund and bring order to societies. While of course many of these governments and laws are imperfect, many work well. This has produced the opportunity for people to have a global footprint, to travel, to trade, and to understand the cultures of people on the other side of the planet.

Let us not forget, though, that we are animals. The animal kingdom isn’t like Winnie the Pooh. It is a brutal, violent, kill-or-be-killed world. We have created these societies because humans have figured out how to produce a powerful mix of incentives and rewards, and these incentives have a fundamental impact on human behavior.

In a nutshell: when we map the right rewards to the right incentives, they can generate desirable human behavior, which in turn generates value. Fortunately, human beings respond well to incentives. We receive a salary for going to work, we shop at the same stores when we receive gifts for regular custom, we love to collect trophies in video games, and we respond well to cash bonuses, overtime pay, and other ways of getting something for giving something.

We are incentivized by status, such as being at the top of a leaderboard in a live spin class, speaking at a TEDx event, or getting the next job title up the chain. We are incentivized by clear rewards, great experiences, working with smart people, and accomplishing new or novel outcomes.

Here’s the tricky thing though: crafting incentives is hard. While coming up with ideas for incentives can be a fun exercise for you and your team, wiring them up to work predictably is complicated. This can often result in expensive experiments that deliver limited results.

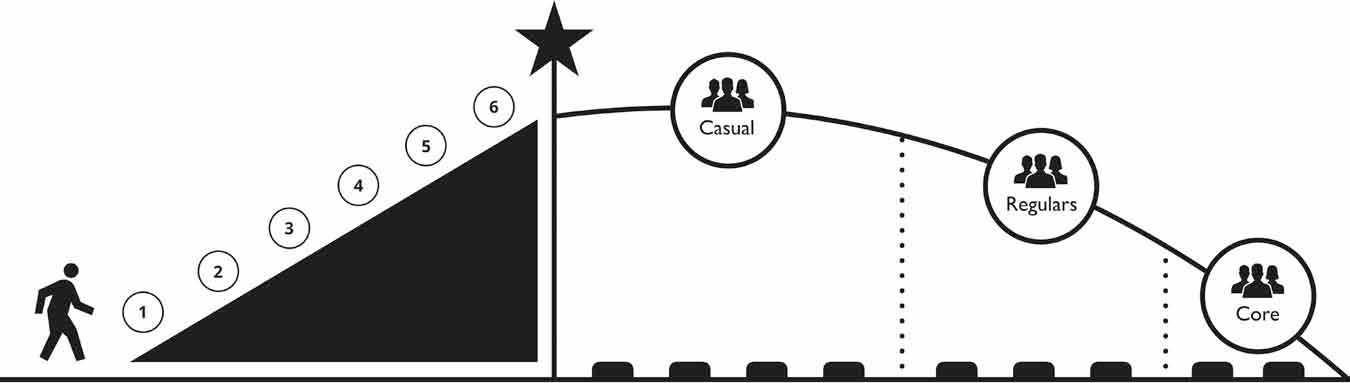

Let’s go back to our familiar Community Participation Framework. It incorporates my approach to how we decide on and deliver these incentives.

As you know by now, our goal is to keep our audience members progressing from the left to the right.

Incentives are the little dots at the bottom that present opportunities and rewards to the members who generate the desired behavior. You can look at each phase (Casual, Regulars, and Core) and design which types of incentives you need at that point in the journey to continue their growth and momentum.

These incentives should spur your members to produce tangible content, material, and skills. Importantly though, you shouldn’t just incentivize the things you can measure with computers but also the things you can measure only with judgement and observation from your community team, such as good conduct, being trustworthy, providing care, and building belonging. In this chapter we get into what these incentives are, how we create them, and the value they can generate.

THE POWER OF INCENTIVIZATION

Incentives often appear simple on the surface, but there can be a lot of complexity under the covers. Let’s first explore the anatomy of an incentive and then cover how to produce and distribute them.

The Anatomy of an Incentive

There are thousands of potential incentives you can apply to your community. It could be celebrating people who have participated regularly with public recognition and adoration. It could be sending someone a customized mug the first time they submit a new contribution to your knowledge base. It could be inviting someone to your office to participate in a leadership meeting.

Every incentive has three fundamental ingredients encased inside it.

1. The Goal: First, what is the desired behavior you want to incentivize? Do you want people to answer questions, write code, run events, or something else?

Look at your audience personas, your Big Rocks, and what you want members to accomplish. Prioritize the most critical types of participation. This will provide a list of the goals for each incentive you create.

As you think about each goal, think about how you measure if it has been accomplished. Kick ambiguity to the curb. Be specific: what measurable outcome signals that the goal has been achieved?

2. The Reward. Go back to your audience personas and look at the Motivations section. What kind of rewards and recognition motivates them? This will vary tremendously depending on your personas.

There are two broad categories of rewards to consider here.

Extrinsic. These are material things we know and love such as T-shirts, stickers, and gadgets. Think outside the box and be thoughtful. HackerOne made superhero comic book covers of their top contributors.1 Mattermost gave their Regular community members customized mugs.2 Buffer would tune their swag to the individual (such as sending dog chew sticks and a note to a known canine fan).3

Intrinsic. These rewards thank someone for doing great work and gives them a sense of personal satisfaction and belonging. Celebrate great work from your members on websites, blogs, and social media. Invite Regular and Core members to dinners with your team. Provide Core members with a direct line to your leadership.

When designing your rewards, always start with intrinsic rewards first. This may seem counterintuitive, but intrinsic rewards will almost always have a positive impact whereas extrinsic rewards run the risk of having a moment of novelty value that is then forgotten. We will cover this more later in the chapter.

Intrinsic rewards build satisfaction and belonging. Think carefully about how you can beef up someone’s self-confidence and satisfaction in the community. It is incredible the impact a simple personal email thanking someone can have, as well as recognizing them in a public place such as a blog, video, or event.

Be careful with extrinsic rewards. It is easy to default to the tried-and-tested extrinsic rewards, and company after company schleps T-shirts, stickers, and other tat to their community members. Most critically, make your swag meaningful and personal. Include a personal, handwritten note as a bare minimum.

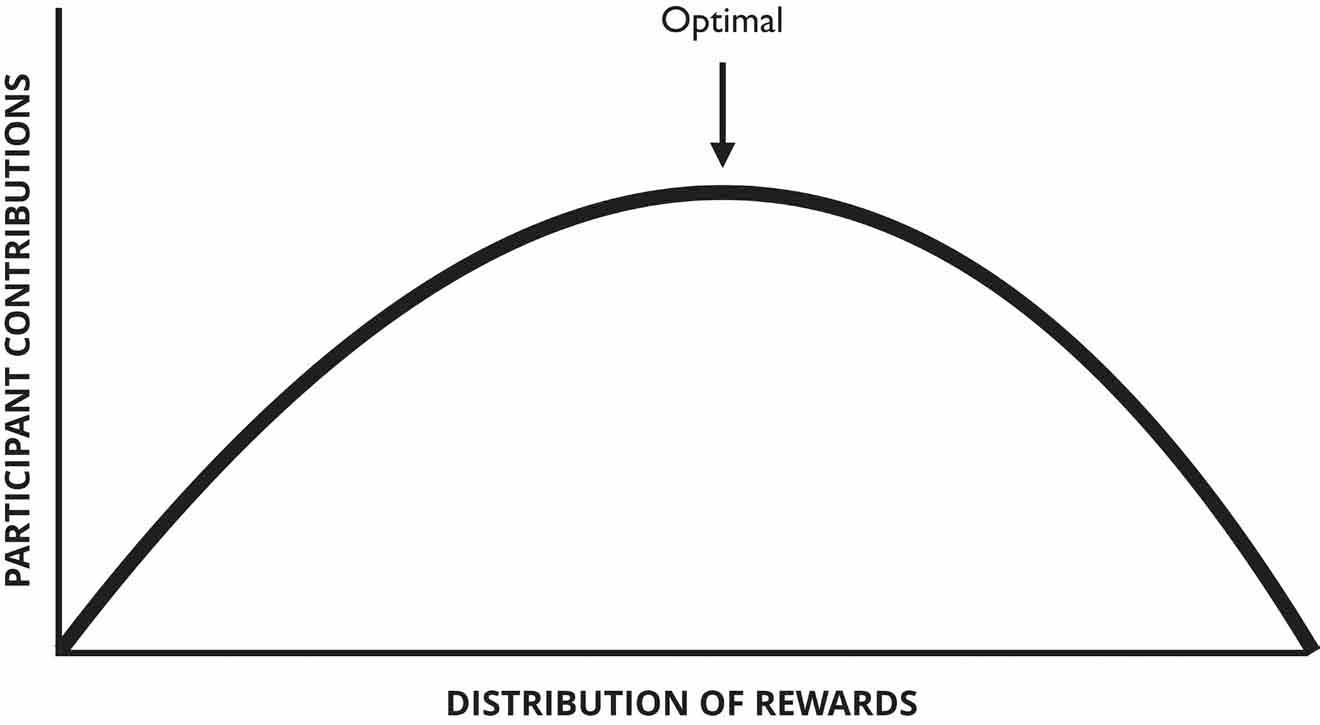

Also, be careful with how much you reward people. Inspired by the Yerkes Dodson scale, which covers the link between arousal and performance,4 I have noticed a similar trend between performance of participants in communities and the distribution of rewards, as outlined by my Participant Rewards Peak shown in figure 8.1:

Fig. 8.1: Participant Rewards Peak

In a nutshell, if you distribute the right balance of rewards based on performance you can incentivize peak results. There is a risk though of oversupplying rewards to the point where the participant is so focused on getting the rewards that their priority becomes the rewards and not doing great work. Be careful not to overdo the extrinsic rewards and always monitor the balance of performance compared to the rewards you provide to see if this is happening.

3. The Condition: The final piece of the puzzle is the condition. That is, what measurable criteria needs to be met to accomplish the reward?

The idea is simple: we want to plumb this criterion into our community so that when it is triggered, it generates the reward with the most limited amount of manual attention.

There are four considerations in deciding on your condition:

1. Be Measurable. First, as a general rule the condition needs to be objectively measurable. Can you assess whether the condition was accomplished with a “yes” or “no”? Again, there are no “maybes” in our lexicon here. “Answer twenty questions” is measurable, but “Be a devoted question-answerer” is not. Get specific. Stay specific.

The exception here is with rewarding general human behavior (e.g., mentorship, insight, kindness, and support). In these cases, you need to observe this behavior, so be clear on what you want to measure and ensure others share your definition of what “good” is.

2. Be Representative. Does this condition represent the behavior you want to see? For example, if you want to encourage your community to provide help, merely posting to a forum isn’t necessarily a good measure of quality. What we really want to see is high-quality content, so maybe an approval (or even a simple “like”) is a better way of judging this behavior. As we discussed earlier, when you lay out incentives, it will change behavior, and some folks will abuse the system to accomplish the reward. Ensure your condition can avoid these bottom-dwellers by providing safeguards to reduce abuse (such as entrance criteria or requiring approval/validation).

3. Be Varied in Difficulty. You should gauge how difficult it is to accomplish this condition. Your incentives shouldn’t all be SEAL team training missions; they should provide a wide range of incentives at different difficulties. Fortunately, we can use our Casual, Regular, and Core segments to guide us. We will cover this more a little later in this chapter.

4. (Where Possible) Be Automated. Where possible, measure your condition with a computer and react to those measurements. This can be a single metric or combination of metrics. Always be clear what these measurements should identify. For example, detecting when a code submission has been approved, a question has been answered, or a member has answered their tenth question in one month (to detect consistent participation).

As I mentioned earlier, some behaviors are difficult to measure with a computer, such as social development and interaction. In those cases, ensure that your team is clear on what success looks like, and depend on them to observe and react when they see it.

INCENTIVES: TWO GREAT FLAVORS

OK, we have a good idea of the value of incentives and the constituent parts. How do you produce an incentive strategy?

Our fundamental goal is to plot a series of incentives that keep people transitioning forward, first to the on-ramp, then to Casual, on to Regular, and then to Core. Strategically, you should build your first set of incentives at the transition points between these phases, illustrated by my Incentive Transition Points in figure 8.2:

Fig. 8.2: Incentive Transition Points

These transition points are when community members are at the greatest risk of getting distracted by that new Netflix show and falling away. For example, how do you incentivize someone to get on the on-ramp for the first time? A simple solution here could be rewarding them when they produce that first piece of value at the end of the on-ramp (many organizations reward this accomplishment with validation and/or a gift).

How do you transition this first accomplishment into Casual participation? Here you should incentivize repeated participation, such as rewards for developing new skills, producing new material, and supporting the success of others.

For the transition to the Regular phase, incentivize and reward when people step up to the plate with additional responsibility. Importantly, in this phase you should explore ways community members can take the initiative and play more and more of a leadership role.

In chapter 1, I quoted Emmy Award–winner Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who shared with me the importance of leadership, not just in the creative process but in the formation of his HITRECORD community. “An open collaborative process really needs leadership. This is a big part of how we’ve built our platform and community. At first it was always me leading our collaborative projects, but over the years, it’s been great to see members of the community step into those leadership roles themselves.”5

The Regular phase is an opportunity to identify these leaders. Provide lightweight opportunities for members to lead, mentor, and use their initiative.

Finally, for the transition to the Core phase, produce a narrower but deeply valuable set of personal incentives for particularly outstanding leadership and devotion. Incentivize them for helping to shape new initiatives, solve tough problems, improve key elements of the community, etc.

To design and deliver these kinds of incentives, I break them down into two primary categories.

Stated incentives are clearly communicated opportunities for community members to participate in. They are published and have clear criteria and rewards. Stated incentives include gamification badges, competitions, hackathons, and contests. They are similar to quests in video games: if you accomplish an outcome, you receive some kind of reward, even if it is just a badge or virtual trophy.

Submarine incentives are the sneaky cousin to stated incentives. They are preprogrammed ways in which we can detect great community participation and then validate and reward it in a human, personal way. They appear like seemingly random acts of kindness—the random gifts you receive for doing something, the kind email from the founder of a project supporting your recent work, and the opportunities that open up the more you participate.

Both of these types of incentives are enormously valuable in a community. Let’s delve into each in more detail and how we produce them.

Stated Incentives

If you peel open any modern video game, particularly multiplayer and open-world games, you find a delicately crafted set of incentives. For example, many first-person-shooters award points at the end of each round, which can then be spent on equipment, weapons, and more. These points are distributed based on how well you played, and it incentivizes players to improve their skills.

Stated incentives are clearly communicated up front. You can window-shop for rewards and get them if you accomplish the stated goal.

Take a look at the transition points in figure 8.2 and produce five to ten incentives spread across these transition points. Here are some examples (each of these would be promoted openly as incentives and their associated rewards):

On-Ramp

• If a member answers their first question in a support forum, they receive a badge that is visible in their member profile.

• If a member contributes their first piece of (approved) content to a blog, they earn a free e-book with writing best practices (useful for future work).

• If the member gets their first app approved for a platform they get a “care kit” with T-shirt, cap, free training materials, and the name of the app etched into a statue outside the company office.

On-Ramp → Casual

• If a member has ten of their responses to other members’ questions accepted as answers, they are sent a personal note and a ten-dollar gift card to an online store.

• If the member has five of their code contributions reviewed and approved, they get highlighted in a blog post in the community.

Casual → Regular

• Launch an online hackathon to see who can fix the greatest number of bugs in the community project in one week. The first-, second-, and third-place winners will receive prizes, and everyone who submits a bug that is fixed will be highlighted in an article and on the website.

• A content contest is launched to produce the best tutorial videos for a product. The top three videos (based on a judging panel’s votes) win a specific set of prizes.

Regular → Core

• Members who get voted onto a community leadership board will have direct email access to the company leadership team.

• The top ten ranking members in terms of reputation will be invited out to three days of meetings at the organization’s headquarters, with full travel, board, and meals provided.

Think also about empowering your community members to reward people. A previous client had a system where employees had a limited amount of cash each month (sixty-five dollars) that they could use to reward other employees via spot cash rewards. As an example, a designer did a great job for a product manager, and she gave him ten dollars from her sixty-five-dollar budget. Interestingly, the employees who made the most money were the front desk, receptionist, and admin staff (arguably, the most underappreciated people in a company).

These rewards were popular, not just for those receiving the money but also for how it empowered the staff to distribute them.

Submarine Incentives

As we discussed in the last chapter, one of the major challenges as communities grow is in maintaining a personal touch. For small communities of less than 150 people, this is less of an issue because you and your team can engage with your members directly. As you grow larger though, it can be difficult to maintain this personal touch. There are simply too many people to keep track of.

Submarine incentives are one tool for dealing with this problem. They are preprogrammed incentives and rewards that, when triggered, provide an opportunity for us to engage personally with a member. This allows us to scale up and still be personal.

As one example, a previous client had a web platform. When one of their users submitted content via their platform, we would award points based on the quality of the content. We would then use these reputation points to deliver a series of incentives and rewards.

One such reward was when a user submitted around five pieces of content (which demonstrated a repeated level of participation in the platform). The system would detect the fifth submission, notify us, and we would send them a personal email offering to send them a T-shirt. This wasn’t a published “If you submit five high-quality submissions you get a shirt” incentive. They simply got an email out of the blue from someone saying:

Hi Sarah,

I just noticed you have been doing some really amazing work in our community recently, and I saw the flurry of high-quality submissions. I was particularly impressed with your most recent contribution and how you [. . .]

I would love to send you a T-shirt as a sign of our appreciation. Please go and fill in this form with your shipping address and size.

Also, if you have any questions, or I can help with anything, just let me know; you have my email address now.

Joe

Importantly, this email wasn’t sent from a robotic email address; it was sent from a real person at the company. It was written by a real human being. Sure, the system detected when the incentive was triggered, but the offer of help was very real and tuned to the recipient, and this built a personal connection with the community member.

Again, get creative with this. One community I worked with detected when it was a Regular or Core member’s birthday and sent them a nice note. Another community detected when a community member’s first contribution was not approved, and they would send them some recommendations and a free e-book to help. Use a computer to detect, but ask a person to engage.

Noah Everett is the founder of Twitpic, which at its peak had 30 million users and eighty thousand joining every day.6 He shared with me the importance of this personal touch. “Be very proactive in talking and interacting with those in your community. Try to respond quickly and be sincere. Take the time to craft your response to make it personal (i.e., use their name or reference something they wrote previously) so they know you are actually paying attention and care.” He summarized it simply, “Being authentic is one of, if not the most important, DOs for communicating online.”7

Submarine incentives are particularly powerful for delivering personal validation (an intrinsic reward). In another company, when a member earned their way into the Top 100 users, we would send them an email informing them that they were added to a special category of users and provided with direct access to the executive team via a special email address.

This provided another important psychological function of elevated status and access. While they rarely used this email address, the members appreciated that it was there if needed. Everyone needs a bat phone sometimes.

When considering submarine incentives, there are a few important rules to follow:

1. Make them fair. As with all incentives, you need to make these fair. People will share and discuss them with others, and when they do, you want to ensure that they objectively earned the reward. You should avoid the perception they were rewarded with something when they didn’t really earn it.

2. Keep the recipe secret. While you should keep submarine incentives secret, some people will discover them. In these cases, it is fine to acknowledge that your community is filled with little incentives, but never give the recipe for how to accomplish them away. It will shatter the surprise and people will game the system so they can accomplish the reward.

3. Mix extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. As we discussed earlier, submarine incentives are particularly powerful for providing validation and appreciation. They can be used for delivering extrinsic material rewards such as T-shirts, mugs, trophies, and more. Be careful though in estimating the right number of these rewards so your budgets don’t balloon out of control.

4. Make them personal. Never ever have the communication with the member be a prewritten form email or notification. Computers should detect patterns, but humans should do the communicating. If you don’t do this, you run the risk of making your members feel tricked, just like those awful robocalls for Las Vegas getaways that pretend to be a real person.

5. Build in access and engagement. As people go further and further through the phases we discussed earlier (Casual, Regular, and Core), provide them with more and more access to the leadership and company. Use submarine incentives to trigger opportunities for access and influence. For example, with one client I had a submarine incentive trigger when a major contribution was made, and the CEO would personally call the member to thank them. This is remarkably powerful.

6. Start small and build up. Don’t overdo it. Generate five to ten submarine incentives spread across the phases we discussed earlier. See which ones work and which ones don’t. Then build up from there. Here are some examples at our different transition points. Remember these would not be publicly stated. They would trigger and generate surprise rewards for members.

On-Ramp

• If a submitted contribution is accepted (e.g., content, code), they are emailed a personal thank-you from the community leader.

• If a submitted contribution is rejected, an email is sent with recommendations for improvements and next steps with links to articles and support resources.

On-Ramp → Casual

• When a member has submitted five answers to questions that are submitted, they receive a personal email from the community leader, thanking them.

• When a member contributes an article that gets the highest number of hits in a month, they are sent a twenty-five dollar gift voucher to an online store and are highlighted in a monthly blog (about great work and content).

• If 70 percent of the bugs a member has submitted for a product are valid reports, they are invited to join private testing of the software (with early access).

Casual → Regular

• When a member has submitted twenty-five answers that are accepted, they are sent a “community rock star” challenge coin.

• If a member contributes a new feature that is included in the next release, they are highlighted in a blog post and are sent a limited-edition T-shirt that highlights them as a developer.

• When a member has contributed thirty pieces of content (e.g., articles), they are sent a personal email inviting them to the office to have coffee with the team (and get some swag) if they are ever in town.

Regular → Core

• When a member accomplishes a notable milestone (such as their five-hundredth contribution), they get a call from the CEO of your company.

• The top five members in your community (based on reputation) are sent personal invitations to join the leadership team in the community and the company for strategic meetings, dinner, and drinks (with travel and accommodation covered).

DOING “REPUTATION” WELL

Before we get onto how to build our incentives strategy, I want to touch on reputation. Reputation is commonly a numerical representation of an individual member’s participation in your community. It is the shadow of their character and participation. Reddit calls it karma. Nintendo calls it points. Discourse calls it trust levels. Battlefield calls it kills (of course).

As an example, Reddit karma is awarded for popular links and comments shared by their members.8 Like Reddit, most communities keep the algorithm for how they calculate their reputation scores secret, even if the total number itself is public.

One client I worked with would provide ten points for good work submitted, zero points for a terrible piece of work submitted, and a graduation based on this scale. As such, five points was OK, seven was good, and ten was excellent. Of course, the grading on this was subjective, but no reputation system is perfect. You have to design it to be as effective as possible. This score should preferably be calculated automatically.

Importantly, reputation should decay over time. The goal of a reputation score is to not just grade individual contributions, but to provide a total score that reflects which community members are doing great work around this time. If they stop participating, you should decay the score gradually. As an example, you may want to decay 1 percent of the total score every two weeks in which activity falls below a specific threshold.

This will ensure that reputation is a current figure as opposed to an historical one. If you don’t decay reputation, people who join your community earlier will always have an unfair advantage; newcomers won’t be able to catch up. Of course, if you decay your reputation, be sure to do it gradually. For example, don’t penalize mothers who take time off to have a kiddo.

If you do calculate a reputation score, it can be a fantastically useful metric for (a) seeing the spread of the least to most active members, (b) spotting trends in activity, (c) determining how your users are divided across our Casual, Regular, and Core phases, and (d) providing a Condition (that we discussed earlier) for your incentives and rewards.

Think carefully if you should publish your member reputation scores. If you have a community that is designed to be competitive in nature (such as a game), it might make a lot of sense to publish it. If your community is more collaborative in nature (such as an Inner Collaborator community), you might not want to. While status is a powerful incentive for some, others can feel disillusioned that they “don’t measure up.” Gather feedback from people in your community and organization before you make this decision.

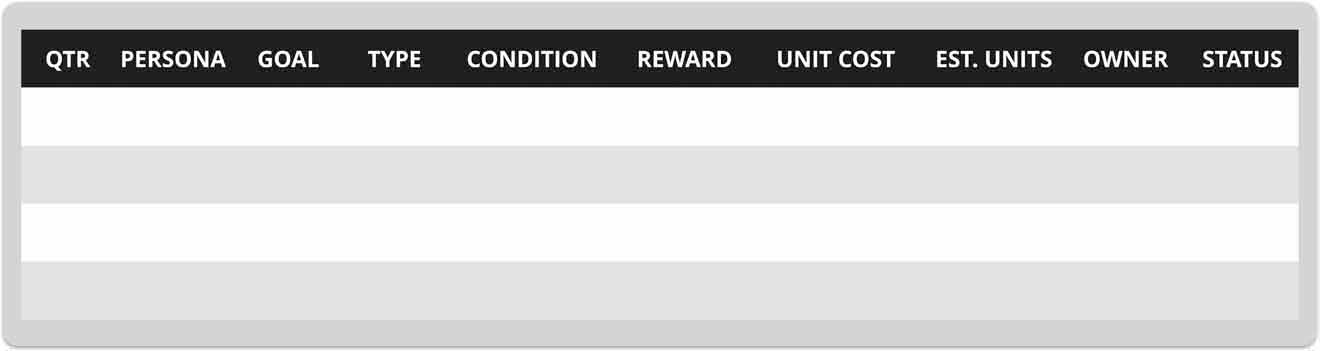

BUILD AN INCENTIVES MAP

An incentives map is a clearly articulated and stated plan for which incentives we are going to plumb into our community throughout the different phases we outlined earlier. It is similar to our Quarterly Delivery Plan but designed to pull together your target incentives. It looks like this:

Fig. 8.3: Incentives Map Template

Here’s how it works:

Quarter: As with the items in our Quarterly Delivery Plan, it is essential that you clearly understand when each of these incentives should be in place and available. Add the target quarter here. For some stated incentives that are individual initiatives (such as a competition), this is particularly important.

Persona: Add which of your target personas this incentive is focused on. Make sure all personas have incentives for every transition point outlined in figure 8.2.

Goal: Now add the behavioral goal you have for this incentive. For example, this could be “Make a first contribution,” or “Providing mentoring to members.”

Type: Add the type of incentive this is (stated or submarine) so you can ensure you have the right balance of both.

Condition: Now add the measurable condition for this incentive. Remember our golden rules earlier: this needs to be measurable, representative, automated, and with a clear level of difficulty represented by the phase it is in (Casual, Regular, or Core).

Reward(s): Now outline the intrinsic (e.g., validation, thanks) and/or extrinsic (e.g., swag, gift cards) reward that will be delivered for this incentive.

Unit Cost. If you are delivering an extrinsic reward, add the individual unit cost for that reward (including average shipping and handling). This will be helpful for calculating budgets.

Estimated Units: Again, for extrinsic rewards, add the estimated number of units you expect to ship each quarter. Again, this is useful for determining overall budgets.

Owner: Just like with our Quarterly Delivery Plan, every incentive needs an owner. This individual is responsible for the overall delivery of the incentive. This includes provisioning the rewards, ensuring the condition can be detected in an automated way, and handling how the member is notified of any rewards they have earned.

Status: Finally, just like our Quarterly Delivery Plan, track the current status of how far along the incentive is going from idea to implementation. I recommend you use the similar statuses we covered in chapter 5: Not Started, In Progress, Under Review, Available To Members, Delayed, Blocked, and Postponed.

Here is an example of a stated and submarine incentive:

Quarter |

Q2 |

Persona |

Support |

Goal |

Providing support to community members |

Type |

Submarine |

Condition |

Member has a registered account on the forum Member answers a question from another user Question submitter marks the answer as solving the problem |

Reward(s) |

Personal email from Head of Community thanking them Copy of an e-book |

Unit Cost |

$2 (e-book) |

Est. Units |

80 |

Owner |

Sarah Jones |

Status |

In Progress |

Quarter |

Q2 |

Persona |

Developer |

Goal |

Contributing first new feature to the project |

Type |

Stated |

Condition |

First code branch is merged into the project |

Reward(s) |

Thanks email from engineering lead |

Unit Cost |

$0 |

Est. Units |

50 |

Owner |

Dave Rogers |

Status |

Available to Members |

GAMIFICATION

A while back I was at an Ubuntu Developer Summit in Europe and a few colleagues and I were bouncing around the idea of some kind of gamification system for Ubuntu. The idea was simple: when people participated in Ubuntu in different ways, we would provide them with badges that they could collect. As with all simple ideas, there was a lot of complexity buried under the surface.

My experiment specifically focused on the development of new skills. It covered a wide range of methods of participation, including engineering, governance, support, documentation, and more. It presented a set of available badges (some of which needed to be earned before others), and community members could discover them, learn how to accomplish them, and then get started.9

My system was popular, but it also made some people nervous; they worried that it would generate “inauthentic participation”—that is, not participating to make Ubuntu better, but instead just to get the badge. This taught me a lot about striking the right balance of incentives and communal collaboration. Out of this work, and studying gamification in other communities (e.g., multiplayer games, exercise groups, and others), I recommend you follow a key set of rules.

1. First, focus on onboarding and skills acquisition. For example, you could gamify setting up a new profile, producing a first piece of content, answering your first question, running your first event, or something else. Don’t gamify based on repetition of activity (e.g., tenth post, one hundredth post, one thousandth post) as this can be easily abused.

2. As you design your gamification platform, discovery is critical. Peloton promotes new challenges when you turn on the screen. Discourse has badges integrated into user profiles. PlayStation has trophies on the main screen. Make it simple for your community members to see what gamification opportunities are available, step-by-step instructions for how to accomplish them, where they can get help in doing so, and any other information.

3. Gamification needs a clear path forward. When you design a gamification system, it is easy to find dependencies. For example, if you want to gamify someone submitting an idea in a community for the first time, you may want to first gamify them registering an account. This way you can only make the idea-filing badge available if the registration badge is already accomplished. This provides a clear, logical path forward for the order these tasks can be accomplished.

4. As you do this work, set clear expectations. Provide simple, step-by-step instructions for what the member needs to do to accomplish the reward.

5. Be sure to protect against “gaming the system.” With every game produced since the beginning of time, there have been people who want to break the rules and find shortcuts. You may not think people in your community will do this, but they will. Ensure that people can’t trick your system into giving them rewards and put in place verification (either automated or manual) to ensure they have properly earned these rewards. Regularly invite people you trust to try gaming the system to see if they can abuse it (so you can fix the flaw).

6. Throughout this, be careful of elevated egos. Some people get crazy when they start collecting lots of rewards (such as badges), especially if those rewards are publicly visible. You should always ensure that your messaging and engagement makes it clear that gamification is one way of participating, but there are many other ways in which people add value. Sometimes you will need to perform an ego calibration, when you sit down with someone privately and ask them to tone it down a little bit. This is rare but sometimes needed.

Which Tech?

There are many different technology platforms and systems out there for accomplishing gamification. I am not highlighting specific ones in this book because (a) your needs may be different, and (b) technology moves faster than books, so the recommendations will be outdated quickly. Do some research, and if you get stuck, drop me an email: jono@jonobacon.com.

MAINTAIN THE PERSONAL TOUCH

Incentives are a powerful way to keep your members interested, engaged, and rewarded. Importantly though, always keep the personal touch front and center as you do this work. Communities thrive on personal relationships. People don’t want to feel they are on a hamster wheel. They don’t want to feel played. Incentives run the risk of coming across as systemic and contrived if you fail to properly use them as a means to foster, recognize, and build these relationships.

Look at your incentives through a cynical eye: have you struck the right balance? If not, refine them until they feel supportive of your members’ success, validation, and relationships.