What Is a Community and Why Do You Need to Build One?

If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

—African proverb

In 2006, at the tender age of twenty-six, I started a new job at a British company called Canonical. Founded by newly minted South African millionaire Mark Shuttleworth, the company was focused on building a competitor to Microsoft’s Windows operating system monopoly. The twist was that this new operating system, Ubuntu, was created by a globally connected network of volunteers who freely shared the open-source code. My role was to turn a small set of contributors into an international movement.

Less than a year into my new gig I got an enthusiastic email from a kid called Abayomi. Little did I realize this message would have a transformative impact not just on my career but on the rest of my life.

Abayomi lived in a rural village in Africa. Like many young people, his email was disjointed, yet sweet. He talked about how he discovered Ubuntu, how he tried to explain it to his parents, and how he struggled to participate in the community due to not having a computer at home. His family lived a frugal life, but his interest in technology was something his parents wanted to support, despite their limited means.

He told me how he would perform chores around his village all week to earn as much money as he could. He would then walk two hours to his local town and use the money he earned to buy time at an Internet cafe to participate in the Ubuntu community.

This Internet time was usually short, often less than an hour. He would answer questions from users, write documentation and help guides, translate Ubuntu into his local language, and more. Then he would walk the two hours back home. He didn’t complain; he didn’t whine. Quite the opposite—he gushed with enthusiasm about how he felt energized that he, a kid in rural Africa, could play a role in a global project making a real difference. I was stunned at not just his commitment but his humility.

Back then, in 2007 in England, Abayomi’s email was yet another example of a rebellion against what I was seeing where I lived. People often complained about their communities withering and dying. It was the same scripture churned out each time: “People don’t know their neighbors anymore,” and “People spend all their time buried in movies, video games, and the Internet.” Lather, rinse, and repeat.

Yet here I saw people such as Abayomi joining and thriving in communities that had an impact. These were communities that were both global and local at the same time. They delivered swathes of meaning, not just to the participants, but also to the organizations that facilitated them. Our friend in Africa was just one cog in a machine that was growing around the world.

His email made two things clear to me. First, human beings are naturally social animals. We have been for hundreds of thousands of years. Yet something magical was happening. This delicious cocktail of technology, connectivity, and people was creating the ability for thousands around the world to come together as a well-oiled (and often rather caffeinated) machine to generate incredible value, far beyond the capabilities of any individual. Abayomi’s passion for the Ubuntu community wasn’t just that he could make an impact; his impact was amplified when combined with other people in the community.

I knew then and there that my life’s work would be to understand every damn nuance of how this cocktail works. I wanted to understand not only the tech but also the people, the psychology, the emotional driving forces . . . anything that could help me to understand how these pieces worked together and what makes the people involved tick. I wasn’t interested in shortcuts. I was interested in understanding how all the pieces click together.

Second, I knew that my responsibility as a community leader was to make sure that Abayomi got the maximum value out of his hour at that Internet cafe. If he went above and beyond to get there, I needed to go above and beyond to make it as rewarding as possible. He, and thousands of others, deserved it.

A QUIET REVOLUTION

The scripture about communities dying was not entirely generational grumblings about the young guns.

Historically, communities used to be distinctly local in nature: they existed in your region, in your town, and potentially even on your street. They manifested in local book clubs, knitting circles, political meetings, gaming clubs, and more. They took place in church halls, schools, and coffee shops. They were often attended by enthusiasts and sometimes by nosy busybodies. New members were typically recruited by bringing friends, word of mouth, posters displayed in businesses, and free ads in the local paper.

These communities were engaging, high-touch, and meaningful, but they had their limitations. There was a limited audience available to attract, and even if you did get people through the door, there were only so many that you could fit into the physical venue.

Not only this, but joining these groups required quite a leap for newcomers. You were asking people to take time away from their families, friends, and colleagues to show up and talk to a bunch of people they didn’t know. This was a tough pill to swallow for many, particularly those who were anxious meeting new people or those in underrepresented groups.

Even if you did pluck up the courage to go to one of these community meetings, there was no guarantee it would be fun or interesting. While some were a fun, dynamic meeting of minds (such as sports fans getting together), some were dry, awkward discussions. These groups often reflected the personality of their founders. The fun ones were generally founded by fun people.

If you made it to the end, after the meeting there would often be no continuation until the next time everyone was back together in person. People would go home and there would be little-to-no communication until they reconvened in the same building the next week or month. It didn’t feel like a community as much as a series of events that tended to attract the same crowd over and over again.

This blend of limitations often nixed the potential of many of these local communities. They were often local curiosities that served a niche audience. Unsurprisingly, some of these communities started to die out, likely contributing to the grumbling from the elder generations about how community wasn’t a thing anymore. Oh, and to get those damn kids off their carefully manicured lawns.

THE MICROCHIP AND THE MODEM: THEY FIGHT CRIME

Aside from the ’90s bringing us hammer pants, bleached spiky haircuts, and awful skateboard movies, we also started seeing the world become more connected.

While the Internet was forged in universities and research campuses in the ’80s and ’90s, it was far too expensive and technical for the general public to use. As the tech became simpler, it became more pervasive.

People want to engage and connect with each other. We want to build relationships. We want to share ideas, information, and creativity. Unsurprisingly, early communities started forming like clustered amoebas in this rudimentary online pond.

In the ’80s, early message boards formed on bulletin board systems such as CompuServe and distributed discussion systems such as Usenet, covering a raft of primarily academic and rather nerdy pursuits.1 People produced and shared text files containing anything from scientific research, to technology guides, to various acts of anarchy (such as making backyard explosives and pranking your local burger joint).2

This fascinated the early digital explorers. For those technically inclined enough to get connected (often at universities), this global network provided a way to communicate with people on the other side of the country or world. You could discover information that would never be in your local library. It made information and those who produced it powerful.

Given that the early Internet pipes were thin enough to only exchange small chunks of text, these early communities optimized for the best kind of text. One kind was source code, the building blocks and recipe of software.

Back in those early days, software was a closed-off world. Large companies such as IBM, Apple, and Microsoft produced software and kept their code such a carefully guarded secret that the fried-chicken Colonel would be jealous. While this was the norm, one person—Richard Stallman, furious that he couldn’t fix his printer software (because the code wasn’t available)—believed that all software code should be free for people to share and improve.

Stallman kicked off the GNU community, who started making free software and sharing the code on the Internet.3 It was a magical combination: most of the people online back then were techies and programmers. People started to download this code, which was simply digital text, improve it, and share their results with others of a nerdy persuasion. A small library of free tools started to build. This jump-started other communities such as Linux, Apache, Debian, and more.

The Internet became a place where people didn’t just consume knowledge and have discussions; it was also a place where people could build things together. This set off a chain reaction. People built software, shared knowledge, produced educational materials, started websites, and more. Just like Abayomi would experience years later, for every person who contributed, it made the global community even more powerful. The power of the group was getting stronger and stronger.

While the tech was interesting, it was the people and communities that powered this creation that fascinated me. We were getting a taste of what was possible when people connected together digitally, accessed the same tools, and participated in a central community that generated meaningful value for everyone involved.

FIVE FOUNDATIONAL COMMUNITY TRENDS

If we were to slide any of those early communities under a microscope, we would see five important trends. These underscore everything you are going to read throughout this book, and they are the foundation for the incredible value that can be driven by businesses, organizations, and individuals who want to harness them.

1. Access to a Growing, Globally Connected Audience

Unlike the local church group, today we have the opportunity to access a truly global audience. If there are people out there who share your interest, you can build a community. Cheap marketers simply spam this audience, but we are smarter than that. We are going to engage with them, build relationships, and generate and share value together.

2. Cheap Commodity Tools for Providing Access

You can access and harness this global audience with readily available, affordable tools. Heck, you could start a community with free web hosting, a free forum, and free social media networks. The tools are not the most interesting part of the community equation; it is how we weave them into the ways people share and collaborate.

3. Immediate Delivery of Broad Information and Expertise

Unlike the old weekly meeting at the local community center, this global audience is immediately addressable. We can share news, information, education, and more. We can get the word out more quickly and easily than ever before, stay in touch, and build relationships electronically and in person.

4. Diversified Methods of Online Collaboration

As technology (and our broader understanding of it) evolves, we are figuring out new and interesting ways to work together. In days of old we simply shared content. Today we can work together and collaborate around content and education, be it coding software, building hardware, writing books, making music, creating art, and more.

5. Most Important: A Growing Desire for Meaningful, Connected Work

This is the core of why communities tick. Spin all the way back to the very first page of this, the very first chapter of this book. Do you know why Abayomi walked for hours to his local Internet café? It was because the work was meaningful for him. He could have an impact. While physically he was a kid in the middle of Africa, digitally he was a global player in a movement for a greater good. Abayomi is not alone. This desire is intrinsic to the human condition, and we can harness it in our communities.

A LOUDER REVOLUTION

These five trends have been the foundation behind some impressive communities in recent years, many of which are from recognized brands such as Salesforce, Lego, Procter & Gamble, and Nintendo.

These communities include users coming together to share information and guidance for others using a product, champions who actively create and consume content that promotes the success of the product or organization, and even groups of producers and creators who collaborate independently (often in conjunction with an organization’s employees) to build real, measurable value via derivative products and services.

In all of these cases, these communities are comprised of bright-eyed, enthusiastic volunteers who really care about those brands and products. No one is on the payroll, yet they do amazing work, consistently building broader brand awareness, creating content, and providing a home for likeminded users and customers. This includes:

• Random House, who built the 300,000-member-strong Figment community, which shares, creates, moderates, and recommends content related to Random House products.4

• Lego Ideas, an official community from the Lego Group, in which nearly 1 million members have submitted ideas for new Lego sets (many of which get produced and sold), provided support, and participated in contests.5

• XBOX Live, in which its 59 million active members play, chat, and collaborate together around their favorite video games.6

• The SAP Community Network, in which their 2.5 million membership advocate, support, and integrate SAP products.7

• Procter & Gamble, who launched a community for teenage girls to get answers to their (at times awkward to ask) questions, which has expanded across twenty-four countries.8

• Wikipedia, entirely built by a community of writers, which has created more than 22 million articles across 285 languages (and is valued at $6.6 billion by the Smithsonian).9

• The broader Open Source community, which has built technology that powers the majority of consumer devices, data centers, the cloud, and the Internet itself.10

While Emmy Award–winner Joseph Gordon-Levitt is known to many as an actor in movies and shows such as Looper, Snowden, Lincoln, Inception, (500) Days of Summer, 50/50, and 3rd Rock from the Sun, he is also the founder of HITRECORD—an online creative platform he started with his brother, Dan, in 2005.

HITRECORD provides a place where artists of all kinds can create art together, emphasizing collaboration over self-promotion. Projects are started by members of HITRECORD’s worldwide community of seven hundred thousand artists creating pieces such as short films, songs, and books together.11 Anyone can participate by remixing and building upon each other’s contributions bit-by-bit. HITRECORD’s unique collaborative process has yielded a wide range of partnerships with top-tier brands, multiple publishing deals, screenings at international film festivals, and an Emmy-winning television series.12

Joseph shared with me how the community has evolved:13

Back in 2005, HITRECORD was never contemplated as a collaborative platform. It started out as a simple message board, but as people used it, we realized people didn’t only want to watch my stuff, they wanted to make stuff together. When we saw that happening, my brother and I thought that was so cool. He was the coder, and started building more features on top of this message board to encourage the collaborative process. Then, slowly, the community grew, and after a few years I started working with a couple friends of mine to turn this community into a production company.

Joe and his brother tapped into two key drivers of artists: the desire to collaborate and to have their art recognized. HITRECORD doesn’t just provide a rewarding way to make art with others, but everyone whose contribution is included in a final funded HITRECORD production is compensated (to date, nearly $3 million has been paid to the community).14 The value was clear.

New businesses often see particularly interesting value in community. As an example, Star Citizen, a popular multiplayer space combat game used Kickstarter to raise $500,000 to build their game and have subsequently raised $150,000,000 in crowd-funded donations and have built a community of 1.8 million players.15

Other companies have used community growth as an opportunity to build market relevance, such as the cloud infrastructure company, Docker, who started out life relatively unknown, but built a passionate community around its technology that helped them to subsequently become a staple in the technology infrastructure industry. They are now valued at $1 billion.16

This is an enormous opportunity, particularly for new businesses. A well-designed and run community can generate an army of ground troops that will help you pierce through the noise into relevance.

The inverse of these community opportunities are of course, community threats, and many companies who have not taken a strategic approach to community have struggled with ecosystem growth and engagement. This has included the troubled relationship Uber has faced with their driver community, challenges that United has faced with customer satisfaction and engagement, and the exodus of community members from MySpace and Digg, partially due to changing fashions, but also due to a lack of incentivization and engagement.17 Sadly, it also includes difficulties faced by popular video games with abusive behavior from participants in online games.18

Effective community strategy is not merely an antidote to these difficulties, it is preventative medicine. It provides a structured way in which to define your audience, understand how to serve them efficiently and effectively, deliver the right tools to help them succeed, better support them, channel their feedback to improve your product, and thus reduce the risk of frustration and people leaving.

Now, the psychological and behavioral drivers that generate this value are not unique to public communities. More and more companies, particularly large-scale businesses, have been building internal communities within the walls of their organization to drive efficiencies in product development, reduce team silos, improve communication, provide collaboration and career opportunities, expand recruiting, and to support happier, more fulfilled employees. This has included PayPal, Facebook, Bosch, Microsoft, Capital One, and Google. Similarly, everything you read in this book can be applied to both public and private communities.

Let’s start at the beginning and look at what communities are and why they are interesting.

WHAT ARE COMMUNITIES?

OK, let’s hit reverse a little. There is clearly a bunch of opportunity buried in your common or garden-variety community, but . . . well . . . what exactly is a community?

Fundamentally, they are groups of people united by a common interest. They can be as small as a local book club that meets in a coffee shop on Tuesday evenings, or as big as a global community comprised of millions of users spread all over the world. They can be online, in-person, or a mixture of both. They can be formal and focused or loose and ad hoc.

Unlike other groups of people who gather together, such as audiences watching a rock concert, employees commuting to a large organization’s campus, or customers standing in line for the latest gizmo on launch day, communities have a greater degree of permanence between participants and activities they engage in.

When the rock concert ends, the show is over. Communities are different. They provide a place where people can get together to repeatedly engage and possibly collaborate with each other. This forms a connective tissue between those people and the broader community. In much the same way muscle is formed when you repeat the same motions, community is formed when people engage together more and more.

Fractal Audio Systems, based in New Hampshire, builds a range of equipment designed for guitarists. They are known for their high-quality emulation of analog tube amplifiers, and they have developed a considerable community around their products.19

Arguably, a typical Fractal Audio Systems customer could buy their products, download a few sound patches and updates, and be on their way. Instead, their forty-thousand-strong community discusses and supports each other extensively on their forum, produces sounds that others can download (via their Axe Change service), and has produced a raft of documentation, videos, tutorials, and more for how to use the products as effectively as possible.20

Fractal Audio Systems doesn’t just have a customer-base; they have a rapidly evolving and growing community whose members keep coming back to the well. This is not just because they get more out of the products, but because they love the sense of belonging the community provides. I am one of those members.

The Fundamentals

Now, as we are starting to get to know each other, I need to make two things clear to you.

First, I am going to be bluntly honest with you all. There is no silver bullet or guarantee that your community is going to succeed. Building communities is hard. A major risk of failure exists if you are not integrating community development skills into your teams and thus getting inconsistent, lumpy execution. This book presents my approach and method, which is a pragmatic, practical approach. While it is designed to help mitigate these risks, it is critical that you focus heavily in baking these skills into your organization to help you and your teams succeed.

Second, this is complex work. There is a lot of detail and as such a high risk of distraction and chasing after shiny things. We need to stay focused on the right things but always ensure they are connected to our broader objectives.

When I learn any discipline, I zoom all the way out first to see the broader picture we want to paint and then gradually zoom in and fill in the details. This is going to be the approach I take throughout this book. So, let’s zoom out and first take a look at the social dynamics of how communities work.

If you want to build a great piece of software, you need to understand the hardware it is running on. If you want to be a professional athlete, you need to understand the rules of your game. If you want to be a world-class BBQ cook, you need to understand how your grill works. Similarly, if you want to build a community, you need to understand the psychology of people and how they engage with each other.

The Heart of the Human Condition

When you take away the computers, screens, cell phones, and cars, it is easy to forget that we are actually animals.

Just like animals in natural habitats, there are drivers that influence our behavior and how we think and approach the world. These drivers happen deep in our subconscious, but understanding them can provide a psychological blueprint for how we approach building communities that map effectively to the natural human condition.

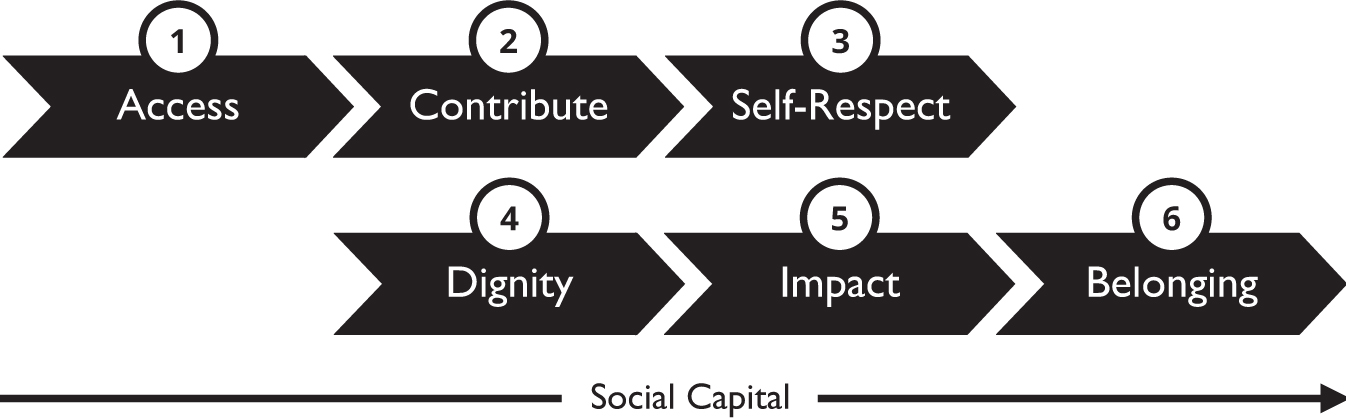

This is reflected in my Community Belonging Path (Fig. 1.1):

Fig. 1.1: Community Belonging Path

All community success stories start with someone having access to the information, tools, permission, and guidance needed to help them contribute something as a newcomer to the community. This contribution can come in the form of answering a question, producing content, sharing insight, producing software, or myriad other things. Simple, available, and intuitive access is essential for a community to succeed. It is the gateway for everything that follows.

When new contributions offer value to the community (and are generally appreciated), it typically builds a sense of self-respect in the individual. They feel they are doing good work that is validated by others, and confidence starts to form. This confidence helps them to more proactively and logically solve problems and foster better social cohesion in the group.

As self-respect grows and they continue to contribute, a sense of dignity forms. Dignity is an important psychological sensation. It gives us pride, peace, social acceptance, and an intrinsic sense of value. It continues to build confidence in ourselves and our capabilities. It feels bloody good, and for good reason.

A key input in building a sense of dignity is that the work we do has meaning. As a professor of psychology and economics at Duke University, Dan Ariely has studied how meaning plays an essential role in our lives.21 He uses an example of a banker who produced an extensive PowerPoint presentation that was central to a merger in his bank. While the banker worked on the presentation, he enjoyed his work and was quite happy to work late into the night to perfect it. When the merger was canceled, he felt deflated. He had still done good work that his manager appreciated, but because no one would see it and it wouldn’t play a role in the desired merger, it was enormously depressing to him. He felt his work didn’t have meaning.

We need our work to have meaning, and the communities that succeed the most are clearly able to draw a connection between the work of their members and the broader mission of the overall community. This is why activist groups such as Amnesty International, the Sierra Club, and Black Lives Matter generate so much devotion: their members feel their work has much broader meaning.

Somewhat magically, when we do feel our work has meaning, it gives us a turbo boost of confidence to step up and have impact. This is where the big, brave ideas come from, emboldened by the respect we now have in the community. This is often where we challenge our assumptions and norms and sail into new territory. Truly world-changing communities are powered by people who feel they have the ability and respect to go out and do something bold because they have both their personal confidence and the shared confidence of the group.

When this pathway is followed successfully, it generates the ultimate psychological treasure in communities: belonging. A sense of belonging makes us feel part of something. We feel validated by our social group (the community) that we are needed, respected, and part of the familial unit. We feel we would be missed if we left or even went on vacation. Dignity provides personal satisfaction and peace in the individual. Belonging provides satisfaction and peace within that individual’s social circle.

As your members flow through the Community Belonging Path and repeatedly contribute value into the shared community, social capital is generated. This is an unspoken, unseen value that is attached to each contribution a community member makes. There is no formal number for social capital and there is no platform that counts it. Social capital manifests as the respect the group has for the individual based on their aggregate contributions and the tenor in which they engage.

Just like in an economy where money can buy goods and services, social capital is a key currency in communities. It is forged from respect, which in turn generates influence. This is how people become leaders in communities: they repeatedly do great work, develop enormous amounts of respect, and as such are trusted by the community to make decisions.

Importantly, social capital isn’t just generated by contributing something worthwhile to the community, but in how you produce it. If you are kind, respectful, collaborative, and produce great work, you will ooze social capital. If you are an asshole and produce great work, your social capital will be far more limited. The social in social capital is the magic word.

This Community Belonging Path is what powered Abayomi to walk so far every week and demonstrate such devotion to the Ubuntu community. Wiring up your community to provide clear, simple access, the ability to contribute effectively, and a sense of dignity and belonging builds success. It won’t just build retention; it will create an infectious level of enthusiasm and commitment that will shape a mature, valuable community.

As you read this book and as we explore the different elements of making communities that tick, always focus on these three key ingredients:

1. How can you make it easy for people to contribute and produce value?

2. How can you help them contribute over and over again and build up their social capital?

3. How can you make them feel welcome and intrinsic to the community while building a sense of belonging?

If you get the human ingredients right, the rest is gravy.

VALUE AND OPPORTUNITY

One of the aspects that fascinates me about community strategy is that everything is different and everything is the same. While many of these deep-rooted psychological and social ingredients are floating around in our brains, communities can manifest and deliver vastly different types of value.

If you are like anyone else with a pulse and an idea, you are reading all of this through your own lens. What kind of value can communities offer to you? How can you harness all of this to further your goals?

Let’s start with value. There are five major categories of value that most communities tend to generate.

1. Customer and User Engagement

You would have to have a screw loose to not want a close, trusting relationship with your customers and users. These customers and users are the lifeblood that not only put food on the table but bring meaning to your work.

Customer success and delight builds retention and brand loyalty, and it is a critical way to separate yourself from those wannabes who call themselves your competitors. Sadly, this is an area where many businesses struggle, but we can turn this into our own opportunity.

Communities have proven to be a fantastic vessel for building a closer relationship between businesses and customers. A community provides a shared environment where members can build relationships with the company, consume and contribute additional value, and see this value being consumed by other members. This builds goodwill. It creates trust. It builds brand loyalty.

One example is Salesforce. Their Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system is big business, providing a central database platform where businesses track customers, clients, partners, and more. As I scribble these words down, Salesforce is arguably the most popular CRM system in the world. Boasting 150,000 customers and an estimated 3.75 million subscribers, Salesforce has an enormous customer base across a broad range of industries.22

The product itself is very comprehensive (some may argue a little too comprehensive), with a number of integrated services bolted in. As such, understanding these different services, using the right features, and making it work for the customer can be a steep hill to climb.

To address this, in 2005 the Salesforce Success Community was formed (which was later renamed the Salesforce Trailblazer Community). Initially it provided access to documentation and guidance, but it started steadily mixing a broader range of features into the community mixing bowl to connect with members.23

The community featured online help and documentation and showcased new functionality and features in each new release. It provided the go-to resource for customers to stay up to date on the products and how to harness those features. It provided a warm blanket wrapped around the product, which helped customers succeed in using it.

As the community continued to grow, in 2007 they integrated discussion forums and the ability to propose new ideas for features. Power users emerged in the forum and started to break out and form user groups. This success continued into 2008, when community content and features were integrated into their flagship Dreamforce conference (an event that almost brings San Francisco to a standstill due to its size). The community hit its one-million-members mark in 2014.

Since then the Salesforce Trailblazer Community, as it is now known, has provided additional structured methods of tapping into existing expertise as well as engaging with the community around new topics. There is little doubt that the community has played a significant role in the success of Salesforce.

2. Awareness, Marketing, and Customer/User Success

“Eyeballs.” That was the answer a friend of mine gave when I asked about her number one goal for the year. Every business needs to grow, and this doesn’t just drive the marketing department but also sales, product, partnerships, and more. Communities can provide a powerful vehicle for building buzz and awareness about your product, service, and brand.

The idea is simple: if you don’t have a community, you are fully dependent on your marketing and PR teams, which might be just a handful of people. They may be great, but there are only so many hours in the day. If you build an energetic army of fans, when they are harnessed well, they can be dependable ground troops in getting the message out.

These members won’t just support and promote your brand, they can generate content that will increase your search engine performance, increase your social media presence, promote the community at local events and global conferences, and open up opportunities with future potential customers, partners, and other engagements. Yep, this all results in the eyeballs my ex-colleague wanted to see.

As an example, back in the early 2000s and early days of the web, a war was brewing. Microsoft had produced the ubiquitous Internet Explorer web browser, but there were concerns that Microsoft would try to lock down the open standards of the web so many sites would not work in other browsers.

The new Mozilla community, forged from the ashes of Netscape, kicked off the GetFirefox community. They advocated for an open web and open standards. They fervently advocated Firefox as a solution for this freer and more-open Internet. As the global community grew, they promoted this message online and in local communities. They were incredibly creative in how they attracted eyeballs. They produced swag, did online promotion, and even produced crop circles and generated enough money to put a full-page ad in the New York Times.24 There is little doubt that this community had a profound impact in the growth of Firefox and, subsequently, an open web.

With the birth of crowdfunding on platforms such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo, community advocacy and promotion has similarly played a pivotal role. Some of the most funded campaigns, such as the Pebble Smartwatch (raising $20 million for their $500k goal) and Exploding Kittens game (raising nearly $9 million for their $10k goal), used community advocacy as a means to reach these goals.25

This all results in not just awareness of your product but also of your brand. Your community can be an amplifier that transmits your brand to a broader set of people. This has happened with brands such as GitHub, Reddit, Battlefield, Facebook, and more.

3. Education and Support

Products are tricky beasts. You can have the glitziest of glitzy marketing and sales materials in the world, but if your customers and users can’t figure out how to use your product, you will lose them. The time between product discovery and clear experienced value has to be short, and the experience has to be simple and pragmatic.

Anyone who has built a product has to deal with how to effectively deliver education and support. The more complex your product gets, the more complex it is to ensure your customers and users are able to understand it and get a good solid chunk of value out of it.

Delivering this education and support can be expensive and time consuming, with most companies producing a library of documentation and videos and providing a support email address. This immediately becomes a cost center, and companies tend to reluctantly invest in it, despite the importance in security for customers.

Communities can be a godsend here. Enthusiastic users of your product or service will often produce guides, documentation, videos, how-tos, and more, all which help to seal this education gap. Not only this, community members will often provide on-tap help and support where prospective and existing customers can ask questions and get help. For example, the game Minecraft has 90 million active monthly users.26 Many of these players learn the game and how to master it from the Minecraft Forum and Minecraft Wiki, the latter of which has more than forty-five-hundred articles, entirely produced by the community.27

If people love your product or service, and it is something that they want to master, it is ripe for this kind of content. All of this taps into a person’s natural urge to teach and experience satisfaction when that teaching helps someone to accomplish great results. If we can incentivize and harness this education and support, you will have an incredibly powerful resource on tap for your customers and users.

4. Product and Technology Development

Red Hat is one of the most successful open-source organizations in the world. They were acquired in 2018 by IBM for $34 billion.28 Since 1993 Red Hat has been actively launching and participating in hundreds of open-source software communities across the cloud, infrastructure, devices, and beyond.

Their CEO, Jim Whitehurst, who is one of the most talented execs I know, firmly sees the importance of community as a catalyst for their innovation. “Our method of working across multiple open-source communities hasn’t just allowed us to survive; it’s enabled us to actually thrive as new technological shifts have occurred. Our innovative technologies are an output of our organizational culture—our people—who give us the ability to adapt and rebound in the wake of disruptive change.”29

Red Hat doesn’t operate alone. The global open-source community has produced tools such as Linux, Kubernetes, OpenStack, Apache, Debian, Jenkins, GNOME, and others that have had a profound impact on various industries, powering clouds, devices, vehicles, space shuttles, and more.

Why do these companies invest in creating code that is shared freely? There are many reasons. Open code means you can attract new contributors who produce features, fix bugs, and improve the overall security of a product. Freely available access makes it easier for people to try technologies, and many companies run a successful open-core model where they have the free open-source version (the gateway drug) and an enterprise version with additional paid features. Throughout all of this, your brand, technology, and team has a much broader potential audience due to the lower barrier to entry.

All of this can generate significant financial value. As one example, the Linux Foundation, a trade organization focused on open source, determined that to rebuild an open-source operating system using proprietary methodologies would cost $10.8 billion.30

Other communities have also formed to create additions that sit on top of existing platforms. The Wordpress content management platform, which is available freely, has developed a passionate community that has built more than thirty-nine thousand plugins and extensions that extend what Wordpress can do. This has resulted in just under a billion downloads and Wordpress running 30 percent of the web.31

There are also other types of product development that communities can help with beyond code. Massive online games and environments such as SecondLife and Star Citizen (the latter of which reached $200 million in their crowdfunding campaign) have made content development a central theme.32 Players can create items, buildings, storylines, and more, many which are intricate and take months of development.

In some of these environments, entire economies are formed from producing and selling this content. In fact, back in 2008 I met a guy in Amsterdam who quit his day job because he ran a number of virtual businesses inside the SecondLife online world. People like him fueled much of the innovation in that community via this economic driver.

If you can think of opportunity, you can probably harness it. In 2007 I wrote an application to help people consume online learning across a range of technology projects. I wrote and released the application, but one limitation was that it was only available in English. I shared it with our community and asked for help to translate it, and within twenty-four hours it was fully translated into eleven languages. Before long, it would be available in forty languages.

Other communities have contributed product feedback and testing, usability, visual design, and more. If you provide a clear way to map a community member’s skills to delivering meaningful work, it is incredible what results you can generate.

5. Business Capabilities

“I just don’t understand why anyone would want to sit in a cube all day and work through a task list,” said a young woman whom I spoke to at a university a few years back. I have to say, I agree with her.

She is growing up in an age where collaboration online is the norm. She has enormous control over her own destiny in her chosen career path, and she understands that she can build her experience and résumé on the Internet and via community groups and meetups.

This poses a threat, or at least an awkward reality, to larger businesses. If you don’t have an environment that shares similar principles to a collaborative community (cross-team collaboration, career development, social engagement, etc.), you are going to struggle to hire. While the free soda and trail mix may woo employees to work with you, a healthy working environment will keep them.

Building and engaging with a community doesn’t just integrate these skills into your organization, it also provides a funnel of potential candidates. Many of my clients hire a significant number of people from their communities. This doesn’t just make recruitment easier, but the employees also come prebaked with relevant experience and context. For many of these members, their dream job is working for the company. It is a win-win situation.

Communities also provide a wealth of user experience and insight. As your community grows and as you build retention in members, they will develop a fantastic corpus of experience and expertise that you should tap into. This expertise and insight can help you with product design, development, and delivery. They can provide insight into how you could continue to grow and optimize the community as well as much-needed honesty (sometimes of the brutal kind). Whenever I have interviewed community members and gathered data, it has consistently netted positive results.

They will also be a powerful source for lead generation and networking. By growing a community of passionate users and customers, you will not just be providing an environment for people to meet and get help but also a place where prospective customers can evaluate your product or service in more detail. This builds brand loyalty and often lead generation.

Now, you need to be careful here. Do not let your sales team treat your community members as a pipeline. This is a surefire way to annoy them. Instead, build your community and let your members naturally bring people to your business. As an example, I have sometimes set up a community concierge, where established community members can reach out to members of the company to introduce prospective customers.

Finally, don’t think of your community as merely a subservient group. Think of them also as a group of potential mentors. As you get to know them, build friendships, and develop trust, reach out to them for guidance. Help them point you in the right direction. Help them to help you see your blind spots. This not only helps you be better at being you but it develops close relationships that will reflect well on the overall community.

IT AIN’T ALL ROSES

This all sounds pretty good, right? It is. There is enormous opportunity wrapped up in communities, but it doesn’t come for free. It requires careful strategic design, organizational alignment, and focus. That is what this book is here to provide.

As with any initiative, there are risks attached. I don’t believe in sticking your head in the sand. Instead, let’s get some of these most critical risks on the table right away, and then we can design around them.

There has to be a need. Communities should be at the epicenter of where people have a shared need or interest. If you have a product or topic that no one cares about, you are going to struggle to build a community. They are not a marketing gimmick for a quick rush of interest.

Now, this doesn’t mean you have to have a mass-market product or service. There are many successful niche communities, but they do need a viable audience with a potential appetite for a community.

There is no silver bullet. There simply isn’t a single recipe or silver bullet for building a community. Every community is different and requires different types of attention and focus to be successful.

The method I share in this book, which I have developed over the last twenty years, is focused on how to build a strategy so the tactics specific to your community will naturally manifest themselves. You can think of this as a lens through which to look at communities and a blueprint in which to approach them. This will give you the foundation of how to predictably build any number of different communities.

There is no guaranteed success. I bet you didn’t want to hear that one, right? There simply is no guarantee you will succeed. “If you build it, they will come,” they say. Well, they are wrong. It should be, “If you build it, take a strategic approach, train and integrate your team tightly, carefully review results, modify your approach, and operate on a clear cadence, they will probably come.” Ugh, what a mouthful, but this is how we will approach this work.

This is a cultural challenge, not a technology one. The first question some of my clients ask is, “Which technology platforms do I need to set up my community?” While this is an important consideration, it is not the first, or even fifth thing we should discuss.

Building a great community is fundamentally about creating an ecosystem in which people produce meaningful work, are able to thrive, are motivated to keep growing, and can help sustain the future success of the community. Doing this well is all about understanding the drivers and motivations of people, and using tech as a means to address and harness those drivers and motivations. Don’t let the tech dominate your thinking.

Communities require discipline and focus. I can tell you right now that a key problem spot, which you are likely to struggle with as you start building your community, is focus. You will work through the method I present in this book, build a comprehensive strategy, and then start rolling it out. As you execute, you and your team will generate a mountain of new ideas and there will be a temptation to change course or get distracted by other things. This will become a particular challenge when you hit some of the bumps in the road with your strategy (which is perfectly normal when learning and delivering anything new).

Building a culture requires discipline and focus. It requires you and your team to show up every day to build engagement, relationships, and value. Many companies I work with struggle to stick to the plan they make, but it is important to see it through.

It will take time (and money). It takes time to put together your initial strategy, load it into a slingshot, and then launch it. It takes more time to attract people, and build clear, consistent, predictable growth and engagement.

As a general rule, building a strategy usually takes around three to six months. Building growth and participation generally takes around a year, possibly longer. Sure, there have been cases where it happens more quickly, but it depends a lot on how you approach the work, how disciplined you and your team are, and the type of community you are building.

THE BACON METHOD

When I was seven, it wasn’t cool having my surname. At school my friends thought it was utterly ridiculous, and they had a point. “Your last name is a meat, you Muppet,” echoed through the halls. The one benefit is that when you come up with a way of working, you can amusingly call it the Bacon Method.

To be honest, I don’t actually call the approach I am sharing in this book the Bacon Method, but it is an approach that I have developed for building communities over the course of my career. I have done a lot of experimentation, have had successes and mistakes, and worked with hundreds of companies, different people, cultures, and goals.

This method is broken into ten steps that we explore throughout the book:

1. Produce Mission and Value Statements. First, in the next chapter we zoom out and think about the bigger picture. What is our broader mission here and what value do we want to deliver in the community—not just for our organization, but also for our prospective members?

2. Choose Your Community Engagement Model. Next, we choose what kind of community we want to build from my three different models (which are also covered in chapter 2), Consumer, Champion, and Creator. This will provide a framework and some reasonable guardrails to help think about what we want to do and what our approach should be.

3. Define What Value You Want to Deliver. Everything has to start with value, and value is an equation with two critical components; the value for you and the value for your members. In chapter 3 we fill our chosen Community Engagement Model(s) with this value.

4. Produce Your Big Rocks. Also in chapter 3, we draft our broad objectives for the next year and ensure they have buy-in and ownership from the different stakeholders and departments in your organization. This is crucial to building a plan that the team can stick to and ensuring your team is fully aligned. Don’t skip this, or heartache (and gas) lie ahead.

5. Know Your Audience, and Build Audience Personas. In chapter 4, we design what our target audience looks like, who they are, what value they bring, what they need to succeed, and which of these different types of audience are most critical. This will be refined into a set of audience personas, which will drive much of our further work—in particular how we find, incentivize, and engage them.

6. Design Your On-Ramp and Engagement Model. With our broader goals and audience clear, in chapter 5 we design the structure of our community. This covers how to build a simple and efficient onboarding experience and how members will transition through three key phases of the community: Casual, Regular, and Core.

7. Build Your Quarterly Plan. With this existing strategy under our belts, the devil now rears its head in the details. We now need to break our Big Rocks down into smaller pebbles: the individual tasks that should be delivered to accomplish these big goals. This is a critical step in chapter 5 and provides the playbook for the team delivering the work.

8. Craft Your Maturity Model and Success Criteria. At this point, we have a firm plan in place. In chapter 7 we examine more closely what success looks like and how we can measure our progress throughout the execution of this work. We do this by using a series of maturity models and modifying them for our own needs.

9. Execute on a Cadence. As we execute this work, we will operate on a cadence. This involves a series of cycles, each of which has a common set of milestones and check-in meetings. This is not just a handy way of producing a manageable set of work but also a proven way of building organizational muscle and capabilities (which, as we will discuss later, is a key goal in this work).

10. Produce Your Incentives Map. We carefully craft a series of initiatives in chapter 8, which help transition our members through our three key community phases. This keeps people engaged and motivated, and it provides an opportunity for our future community leaders to poke their heads above the fold.

ONWARD AND UPWARD

You couldn’t have picked up this book at a more exciting time. We are at this remarkable intersection in which technology, connectivity, and the social norms of a modern society pave the way for us to build powerful, engaging communities. This all provides a remarkable opportunity for businesses to provide and generate enormous value with a community.

Now, you may wonder if community members would be happy for a business to make money partially based around the contributions of all these hardworking volunteer community members. Interestingly, community members are typically happy for the financial success of businesses if they operate their community in an open, honest, and collaborative way. This is where the rubber hits the road and much of the focus of this book.

I started this first chapter with the story of Abayomi walking two hours there and back to contribute to Ubuntu. There was nothing especially unique or distinctive about why Abayomi felt that sense of devotion and commitment. It was what I saw at the time as a rather magical combination of meaning, technology, and access.

Today I understand these drivers much better, and this book will present a methodology that will fill your slingshot with the best possible material. If you are methodical, focused, and disciplined, you could be creating a community that a whole new generation of Abayomis and beyond will feel a similar sense of devotion to. Let’s get to work.