Consumers, Champions, and Collaborators

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

—Leonardo da Vinci

A few years ago, an old friend asked me out one evening to help him prop up our favorite gin bar in San Francisco, Whitechapel. I could tell from the tone of his voice that this was not merely about sneaking back a few G&Ts.

“Jono, I have no idea where to begin,” he blurted out with a whiff of desperation.

My friend had recently moved himself and his family to the San Francisco Bay Area having founded his new company, raised $10 million of venture funding, and now needed to build out a community around his product. This is Silicon Valley, so this was all about building growth, and building it quickly and visibly.

“I was introduced to a few community managers to figure out how this works, but they overloaded me talking about social media, blogging, events, codes of conduct, governance, forums, and a million other things. I am drowning in detail and have no idea how to tie those things to what I actually see in my head.”

His problem is not unique. Almost every client I work with has the same issue. They have an instinct about how a community can provide value, but where on earth do you start?

A further thorn is that communities, and how to build them, seems enormously confusing to most people. While your hunch about the value of a community may seem clear, the reality often looks like an awkward cocktail of people, technology, and processes, all seemingly glued together in some random and unusual way.

This usually results in decision paralysis. Not only are most execs and founders new to understanding how parts of a community strategically click together but, as with my pal, when they seek help from community managers, it seems like they are speaking Greek to them, and—what’s worse—answering questions they didn’t ask. More confusion sets in, and that is when my phone usually rings.

“Jono, I just need a clear place to start. What are my first three steps?” This is how most of these calls begin. Then again, you probably know this—it is probably why you are reading this book in the first place.

Fortunately, there is a clear path and there is a way to make good decisions without getting bogged down in the details. Let’s get started.

“MAKE A PLAN AND STICK TO IT”

I am a firm believer in intentionality. Don’t try to do something. Don’t use half measures. Get in there, roll your sleeves up, quit your excuses, and make it happen. Results are driven not just by determination but also by a clear head and clear strategy.

Strategy doesn’t need to be complicated, but it does need to be consistent. Rod Smallwood, the manager of international rock outfit Iron Maiden, was asked how they pull off such elaborate world tours with complex live sets, carefully aligned with their recording schedule. His answer, “Make a plan and stick to it.”1

Smallwood is right, but it isn’t always quite that simple. Communities are organic, malleable, changing entities. The balance we need to strike is to produce a strategy we are committed to delivering while being reactive to the results and regularly optimizing the strategy based on them. In other words, “Make a plan and stick to it—and regularly make sensible updates to get better and better and better results.” Sure, it is not quite as catchy, but it is critical nonetheless.

This isn’t going to be a walk in the park. As Tom Hanks once memorably uttered in A League of Their Own, “It’s supposed to be hard. If it were easy, everyone would do it.”2 If we have a clear head, shape a powerful vision, and build a realistic-yet-bold strategy, we can get quite remarkable results.

First things first: we need to zoom out. We need to get to the first principles about why we are doing this before we can figure out the what and how.

BUSINESS VISION AND COMMUNITY VISION: SADDLE UP

In 2014 I joined the XPRIZE Foundation as senior director of community. They are one of the most beautifully strange organizations I have ever worked with.

My new boss was the inimitable Dr. Peter Diamandis, a purveyor of boundless energy, who founded XPRIZE to run huge competitions designed to solve major problems in the world. We are not talking about building a better widget; the first XPRIZE was a $10 million competition challenging engineers of the world to build a reusable, commercially viable spacecraft back in 2004 (long before SpaceX and Virgin Galactic).

A significant reason this first XPRIZE succeeded was because Diamandis painted a powerful vision of an ambitious new age of commercial space travel, discovery, and transportation. Equally important was its clear mission: teams were challenged3 to create a “safe, reliable, reusable, privately financed manned space ship to demonstrate that private space travel is commercially viable.”

This mission was brave (“Why can’t we do this?”), bold (“Why should only the government do this?”), and bullish (“Think you can do this? Prove it.”). Frankly, it was nuts, but great missions (and their companion visions) are supposed to be nuts.

A community mission is different than your business vision but tightly wound around it. The vision for your business is the awesome product; the brighter future; the inspirational dream that everyone wants to get behind. The community mission is how the crowd can play a role in making your vision real.

If your business vision is to “Revolutionize how local businesses compete on the global stage,” your community vision could be “To build a global community of passionate local entrepreneurs to help local business owners succeed on the global stage.”

If your business vision is to “Make free legal counsel available to all members of society,” your community vision could be “To build a world-class global community of legal experts focused on meaningful, citizen-focused pro-bono work.”

If your business vision is to “Democratize the Internet with the most powerful cloud platform in the world,” your community vision could be “To build a global community of engineers, authors, and advocates to build the most powerful and extensible cloud platform in history.”

In each of these examples, the community mission provides a clear way in which the community is an engine that powers and accomplishes broader success.

Communities play a valuable role not just in delivering value for your organization but in providing a way for a broader set of people to do meaningful work. Meaning keeps people active and engaged. It generates satisfaction, a sense of belonging, and self-respect. It creates a reservoir of tribal loyalty.

This can build years of dedicated community participation. I have known community volunteers to dedicate forty hours a week of service for more than ten years because of this sense of meaning and belonging. We want this same passion and commitment in your community too. Our mission should inspire this kind of enthusiasm.

MAKE A COMMUNITY MISSION STATEMENT

Sit down with a single piece of paper and write out what you see as your community mission. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Does it grab you?

Think carefully about how your community mission relates to your business vision. Is it clear how the community mission connects the crowd to your broader business vision?

As you work on your community mission, you may be tempted to use a second sheet of paper, start drawing complex diagrams with overlapping circles, or to break your thinking into something that looks more akin to a business plan. Resist that temptation. This isn’t War and Peace; we don’t need to overcomplicate things. Craft a few sentences and make them tight and focused.

Now get others in your organization to feed in and evolve it; their insight will be invaluable. Ask your executives, department leads, product/engineering staff, marketers, and others. Specifically ask them to challenge your thinking, find the flaws, and explore other elements you are missing. Gather their feedback, assess it, and improve your work. Remember, you want everyone to see their reflection—how they move the needle—in your community mission.

Finished with the feedback? Now take a scalpel to it. Cut the fat. Reword your community mission so it is short, memorable, and easy to rattle off at a moment’s notice. Need a few examples? Head to https://www.jonobacon.com and select Resources.

KEEP YOUR MISSION RAZOR SHARP AND IN FOCUS

I once coached a company through this exercise with their entire team in Seattle. We got an awesome business vision and community mission that the team was pumped about. A few months later I came back to the office. They had put the vision and mission in a mahogany frame and hung it next to the restroom door. People looked at it only when they were nipping out to perform their ablutions in between meetings.

Don’t do this.

Your goal is to keep the business vision and community mission front and center in people’s minds. Just like company values, vision and missions are like trees: they need oxygen to stay alive, grow, and thrive. They need to play a daily role in your team members’ lives. They should be plastered all over the walls of your office. They should be reinforced in staff meetings and company seminars. They should be the basis of your performance reviews: did the team really have an impact on your broader business vision and (not or) your community mission? How can you integrate your business vision and community mission in the day-to-day business of your organization?

PICK A COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT MODEL

People often make fun of Star Trek for attracting particularly enthusiastic fans, but it is amusingly somewhat true. Fifty years after its debut, people are still as obsessed about the space-faring franchise as ever.

The Trek BBS is a home for many such fans.4 This thriving online fan forum brings together more than twenty-seven-thousand Trekkies, where they discuss every element of the Starship Enterprise, Klingons, and . . . er . . . other Star Trek things. While twenty-seven thousand is a more-than-respectable number of members, even more astonishing is that they have together generated 6.9 million posts in these discussions.

While these are devoted fans, they are purely that—fans. They may keep demand for the Star Trek franchise going, which is hugely valuable, but they don’t editorially contribute to or shape Star Trek movies, books, comic books, or video games. Fans share a common interest and often enjoy sharing it with others in communities.

Contrast this with the Ardour community, which has produced an entire open-source music production software suite.5 Here many community members start using the program to make music, but then they discover limits to what it can do. Those who are technically inclined can create these missing features and improvements, which are then shared and integrated into the main Ardour program. In that community, members can actually shape and change the very thing that brings them together.

These and other communities differ vastly, not just because the means of participating are so different but also because the norms, expectations, culture, experience, and demands differ.

You need to think carefully about what type of community you want to build. Do you want something more like the Trek BBS, something more like Ardour, something in between, or something totally different?

Getting this right will help orientate your understanding and expectations about what is involved in building different communities. A little strategic feng shui if you will.

I have produced three Community Engagement Models to make this easier. You can think of each as a template or blueprint for how different types of communities work. Every community I have ever seen falls under one of these models.

Let’s take a spin through them.

MODEL 1: CONSUMERS

Consumer communities are the foundation of communities just like Trek BBS that pull together people who share a common interest. They are relatively straightforward, with participants typically engaging in discussion around this common interest. Some may also share personal fan creations such as artwork, photography, outfits, or sculptures.

There are hundreds of thousands of these communities all around the world. They cover myriad interests from sports to fashion to movies, games, technology, and any manner of other topics.

They can be as general interest as the Reddit Science community, with its 18 million members, or as strangely specialized as athletic footwear enthusiasts in the Sneakers community, also on Reddit, with 345,000 members.6 Specialization is the rocket fuel that makes consumer communities fly.

But why does this specialization work? It seems counterintuitive to our one-size-fits-all culture of generic blockbuster movies, derivative pop stars, mass-market fast food, and other things that appeal to the average of all our interests. Surely we should be more homogenized, not less?

Back in 2006, my friend Chris Anderson delved into the value of niches in his book, The Long Tail. In it he shared:

The theory of the Long Tail is that our culture and economy is increasingly shifting away from a focus on a relatively small number of ‘hits’ (mainstream products and markets) at the head of the demand curve and toward a huge number of niches in the tail. As the costs of production and distribution fall, especially online, there is now less need to lump products and consumers into one-size-fits-all containers. In an era without the constraints of physical shelf space and other bottlenecks of distribution, narrowly targeted goods and services can be as economically attractive as mainstream fare.7

In other words, the Internet means that no matter how specific or strange your interest, you can find other people just like you and build content and services that serve them. Put it this way: if a video of a slightly pudgy Korean pop star dancing around riding an invisible horse can be watched 3.1 billion times on YouTube in six years and become a global phenomenon, the evidence would suggest niche interests can drum up an audience.8

Chris talks about niches within an economic context but his Long Tail model maps well to communities. What makes all of this tick is that human beings like to spend time with other likeminded human beings. Hang on, but isn’t this surely at odds with the rather romantic notion that “opposites attract”?

Not really. Angela Bahns, associate professor of psychology at Wellesley College, and Christian Crandall, professor of social psychology at the University of Kansas, studied the nature of likeminded interactions. Spoiler alert: we are hardwired to seek out people with shared interests.

“You try to create a social world where you’re comfortable, where you succeed, where you have people you can trust and with whom you can cooperate to meet your goals,” Crandall says. “To create this, similarity is very useful, and people are attracted to it most of the time.” Bahns adds, “We’re arguing that selecting similar others as relationship partners is extremely common—so common and so widespread on so many dimensions that it could be described as a psychological default.”9

Consumer communities are similar to an open, public clubhouse. They provide a place where people can congregate, have discussions, share ideas and opinions, showcase work they may have created, and debate different aspects of that shared interest.

In 2017, the video game industry generated $108.4 billion in revenue.10 IGN (Imagine Games Network) has built a business serving enthusiastic fans of video games with content, communities, and more. A subsidiary of publishing powerhouse Ziff Davis, IGN is the brainchild of a different Chris Anderson, who also founded TED.

The IGN community is a Consumer model community in action. It is primarily a forum that serves as a video game clubhouse, divided into different sections based on types of games and platforms. At the time of writing there have been nearly 6 million discussions on the platform by 1.2 million members.11 They debate the specifics of their favorite games, discuss new technologies, share maps and strategies for completing these games, discuss industry trends, and more.

Part of the simplicity of the Consumer model is that expectations of participation are very low and there is rarely any entrance criteria. Anyone is welcome to join the IGN community: you can participate as much or as little as you like. Live and let live. As such, engagement varies significantly: some people will seem wedded to the community and some will simply watch the discussions from the sidelines while munching on popcorn.

In Consumer communities, while the means of participation is very simple, the assessment of merit is based on the reputation formed by showing up and taking part. This largely mirrors how we judge others in our normal day-to-day lives at work, home, and in our relationships. How much has the person participated? How skillful are they? How respectful and polite are they? How have they helped other people, particularly weak or vulnerable people, to succeed? Did they use their turn signal when changing lanes in traffic? (Please do this, people. It drives me mad—no pun intended).

Of our three models this is by far the simplest to design and deliver results. It is also the foundation on which the others are built. More complex communities such as our Champion and Collaborator models incorporate the fundamental principles of the Consumer model.

If you want to build a community of customers and fans, this is a good model to start with.

MODEL 2: CHAMPIONS

The Champions model, builds on top of the Consumer model and takes us a step further. Here community members go beyond discussing a shared interest to actively delivering work that champions the success of the community and its members. They can become an army of advocates that support the success of what you and other community members are trying to accomplish.

In the last chapter I touched on Fractal Audio Systems, who produce musical equipment, including the popular Axe-Fx line of guitar processors. They have built an impressive Champion community.

It is not merely a place of shared interest (like the Consumer model) but it has also become a place where customers go to master using the Axe-Fx, whether on the stage or in the studio.

At a simple level, the community is a discussion forum in which people ask questions and get answers. It goes further, though. There is a community wiki (a website that anyone can edit), in which pages and pages of documentation, guidance, tutorials, and reference materials have been added by volunteers across the globe. The community has also generated thousands of videos, demos, sound presets, events, and workshops.

One such community member, Alexander van Engelen, username “Yek,” has written pages of documentation and guidance, and even an entire book about the Axe-Fx, all freely available. He also pours hours of his time each week into helping answer questions, provide guidance, test upcoming products, and more.

Alexander’s motivations are clear: “Some people participate because they want to be part of a group. That’s not my driver. I joined because I wanted to learn. The products have excellent manuals, but there was so much more information scattered around. Everybody had to search individually for answers. I took it upon myself to gather that information and wrote the ‘how-tos’ and book.”12

Let’s not forget: Alexander is a volunteer. He isn’t on the payroll. He generates all of this value focused on the success of Fractal Audio Systems’ products and users, who are a private company he doesn’t actually work for. While you may not be able to fathom why on earth he would do this, thousands of people like him do.

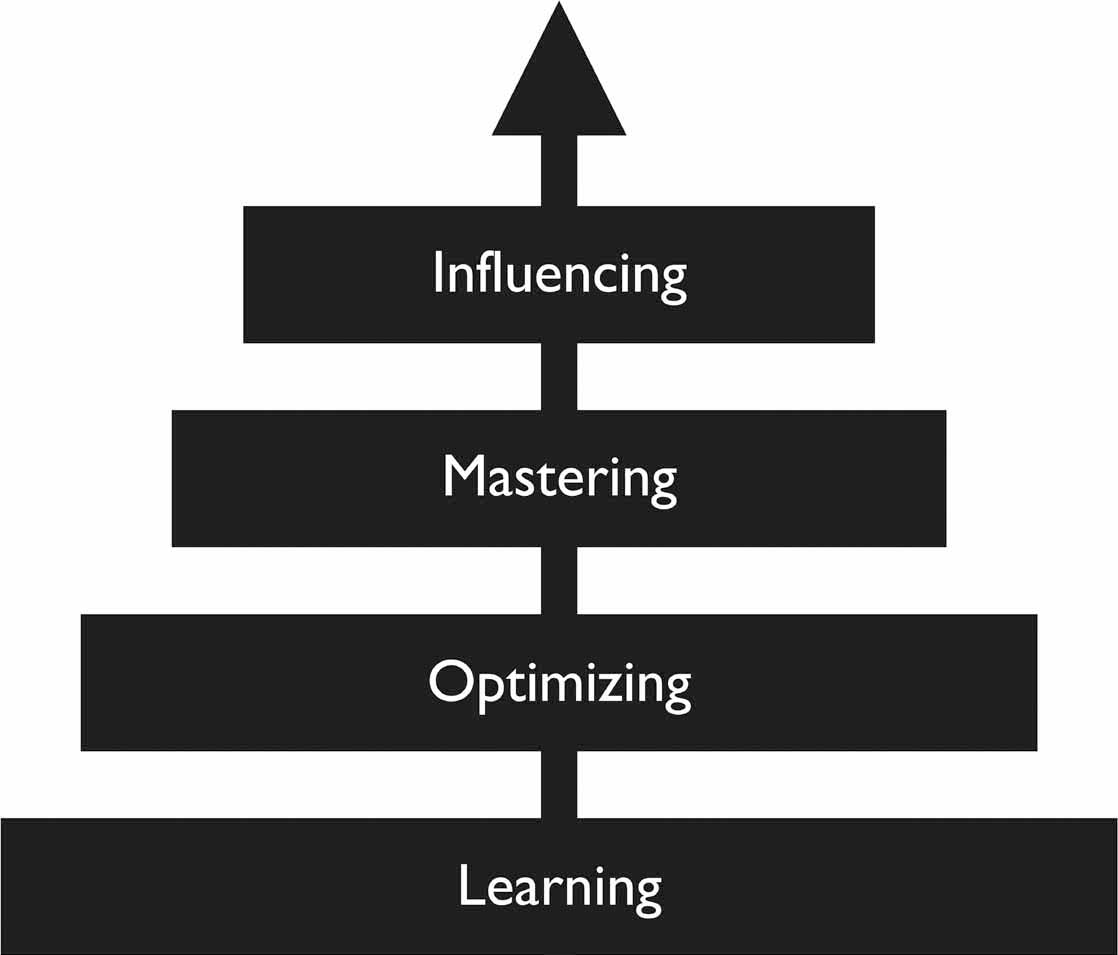

In Champion communities, participants stroll through a progression outlined by my Product Success Model:

Fig. 2.1: Product Success Model

Note: This model does not cover how to “get people into the funnel” and sell people on the value of a given product or service. It presumes they are actual new customers or users. We will cover this onboarding and funnel-filling component in chapters 5 and 8.

Put yourself in a user’s shoes and imagine you just purchased a new software tool for making videos. You have no idea how the darned thing works, but you have a vision of something you want to create in your head: an online video show about how to invest in the stock market like the investing guru you are.

You need to figure out how to use this tool to make this vision in your head real. You see there is a community wrapped around it, so you join.

You wade knee-deep into the first part of the Product Success Model, the Learning phase. You start asking questions, reading tutorials, and watching instructional videos in the community for how to get started. You notice that some of the same people keep answering your questions, and the place starts to feel more welcoming.

You apply the things you know and release your first stock-market video. Now you want to make your second video even better. You ask more in-depth questions and start Optimizing how you work (the second phase in the Product Success Model). Your expertise is starting to show. Other people start asking questions that you know the answer to, so you respond. You feel good about giving back, particularly as the community has been so helpful to you. You start making friends.

You learn more and are able to answer more questions. You transition into the Mastering phase. You enjoy learning and challenging yourself to make even more incredible videos, but you are also enjoying the validation and respect people in the community give you when you help them. People start referencing you more and more as a “rock star” (if only they knew . . .). It feels good; the community is fun, rewarding, and you are getting a lot out of it.

This personal validation gives you even more of an inclination to give back. You start producing new videos about using the software itself. People love them. So you start a blog where you share more ideas. When other community members come to your local town, you meet them for drinks. You are Influencing and a fully formed champion. You and “Yek” should probably hang out.

This is a powerful model for generating multiple value streams: support, content, relationships, and advocacy. While it is a heavier lift, it can work well for products and services where there is a genuine passion and utility.

MODEL 3: COLLABORATORS

The Collaborators model takes the content-creation aspect of the Champion model, bolts on a jetpack, and presses a big glowing Launch button. Remember when we talked about how people in the Ardour music production suite community would add features to the program itself? That is a Collaborator community.

Here enthusiastic participants don’t just add independent pieces of work to the stockpile; they actively work together as a team on shared projects. This can unlock some quite literally world-changing opportunity.

On June 7, 2014, a new open-source project called Kubernetes was announced. It was a piece of software that could be used for managing how software services run on the cloud. I won’t bore you too much with what Kubernetes does, but safe to say, it rocked the tech and enterprise world.

A critical element of why Kubernetes succeeded is that it is open-source. This means that its code is freely available and when there are gaps in functionality, or bugs that cause problems for users, there is a way in which anyone (who meets certain guidelines) can fill in these gaps and create these additional features or fixes. Importantly, once someone creates a missing feature, it is shared with everyone.

Four years later, more than two thousand developers have contributed improvements to the project, shipping more than 480 releases.13 These developers come from more than fifty companies (many of whom compete with one another) as well as independent volunteers. Welcome to the Collaborator community model in action.

What is neat about this model is that the value of Kubernetes (as one such example) increases as more people roll their sleeves up and get involved. If you spend one hour of your time contributing an improvement to the project and ten other people do the same, your one-hour investment will net ten additional hours of value from other people.

As your community grows, it often offers greater and greater added value. This is one of the major reasons why open source has succeeded and now powers the Internet, businesses, the devices in your home, the electrical grid, and beyond: the community is a fundamental part of the value proposition, arguably as important as the software itself.

Of course, there will always be users who consume the fruits of a community but don’t contribute back (“freeloaders,” as grumpy cynics may say before their morning coffee). This is totally fine though. If your Collaborator community always grows and keeps generating new contributions, everyone involved, freeloaders included, will experience continued—and often significant—benefits.

Interestingly, much like stifled yawns around a boardroom table, collaboration can be infectious. When people work together out in the open, solving common, tangible problems, it generates social capital and respect, and onlookers often want to get in on the action. Sometimes the freeloaders are inspired to contribute too!

When this happens, it creates something psychologists call a diffusion chain, in which people basically mimic the behavior of others.14 This act of mimicking strangely results in people often getting better results more quickly, as there is an intrinsic social desire to be accepted like the person the individual is mimicking.

Collaborator communities need to be wired up carefully so people can contribute and collaborate effectively with others. Decisions need to be made quickly and objectively, and there needs to be a fair playing field for everyone involved. To accomplish this we need to mix together four key ingredients in our Collaborator petri dish.

First, provide clear, open access for collaboration. Everyone needs to be on the same playing field and have access to the same tools, guidance, and other facilities. You can’t build a team unless the team has the same tools and opportunity. If some people can access certain tools and others can’t, you will have problems. The bedrock of these kinds of communities is asynchronous access; you can access any of these tools and facilities from anywhere at any time. This access should be as unlimited and unencumbered as possible.

Second, create a simple and clear peer-review process. This should help you determine quality based on the merit of the individual contribution. There needs to be a way in which anyone can contribute something new but their work is vetted for quality, irrespective of who they are or where they come from. This should be simple, clear, and effective.

Third, your collaborative workflow should be open to change. Just as your desk at work is set up exactly as you like it so you can be comfortable and efficient, your contributors want the same. Don’t create an immutable, solid workflow that never changes. Let the community help to fine-tune and improve how they work together.

The fourth component, and a critical one, is to provide equal opportunity and a level playing field. Everyone needs to have an opportunity to shine. I don’t just mean that we clearly welcome everyone irrespective of gender, color, sexuality, socioeconomic background, or other factors but also that everyone can deliver work that is judged objectively for merit.

This is often described as meritocracy, but be careful. Meritocracy is not a framework that can be followed to get predictable, objective results. It is a North Star, a philosophy, and a value that we should strive for.

I am sure some of you are thinking, “Hold your horses there, Bacon. If I am running a business and building a community around it, surely I shouldn’t be an equal. I should be in a position of authority. Shouldn’t I be in charge?”

Yes and no. As great leaders repeatedly demonstrate, building productive, effective organizations and teams isn’t about putting people into boxes of “managers” and “subordinates.” It is about building a culture where everyone is empowered to be their best.

I used to work with a guy called Colin. He was an engineer. He wasn’t a manger or a particularly visible employee. He was quiet, a little conservative, but a diligent and talented worker. He treated people as equals with courtesy and respect, and he delivered amazing work. While the company had a hierarchy and reporting line, great work could bubble up from anyone, and Colin was seen as a central figure. He developed remarkable respect from his peers, arguably more than some members of the leadership team. The environment supported his success. Great Collaborator communities do the same.

Collaborator communities are by far the most complex of our three models, but they can offer enormous benefits when well run. Many organizations have built successful businesses and global brands based around these kinds of communities, especially in the technology sector. These include our earlier examples of companies such as Docker and Red Hat, with the former valued at $1.3 billion and the latter—at the time of writing having sixty-two straight quarters of revenue growth—with an annual revenue of more than $3 billion.15 The core of their businesses are intentional, open, meritocratic communities; done well, the sky is the limit.

DIGGING DEEPER: INNER OR OUTER COLLABORATION

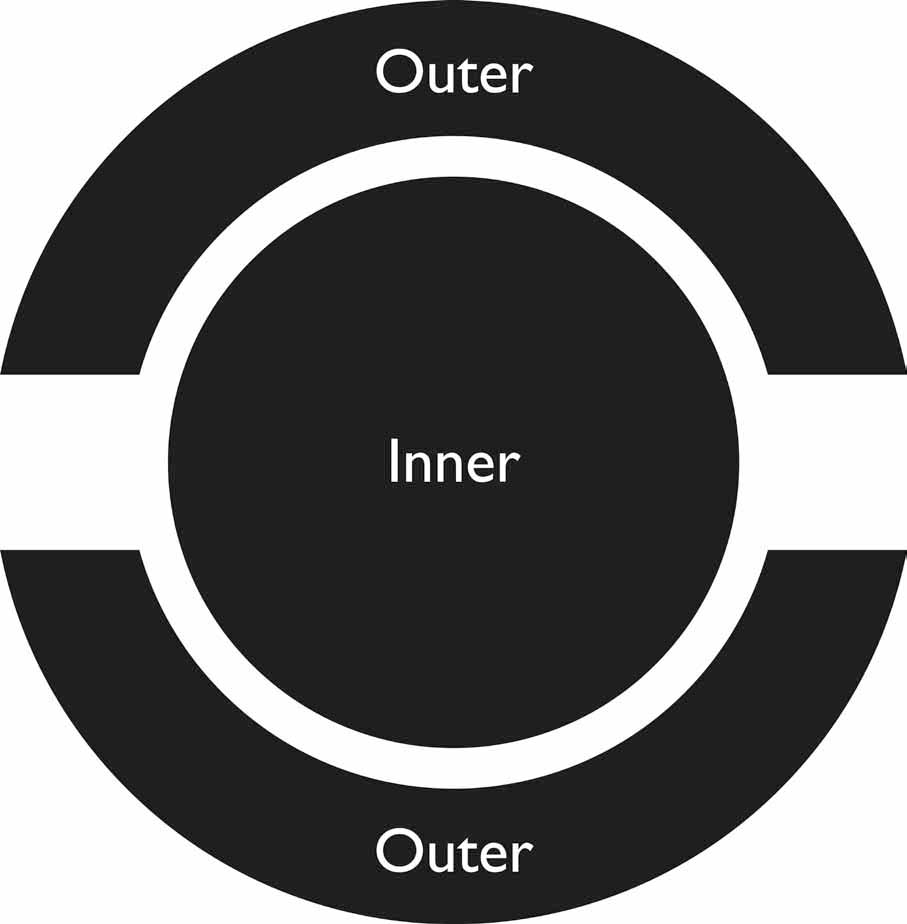

Before we go on, I want to touch on an important subtlety in Collaborator communities. They actually come in two great-tasting flavors. I call them Inner and Outer.

Fig. 2.2: Inner and Outer Collaborator Communities

In the majority of open-source communities that I have worked with, people participate in the same core product the company works on. They add code, documentation, translations, and more.

An example of this is TensorFlow. Originally started by Google in 2015, this open-source, machine-learning project has attracted more than seventeen hundred contributors.16 Not only is the code open, but discussion of the project, working groups that define direction and focus, and issue and bug reports are all open too. This has resulted in TensorFlow being used by companies such as Coca-Cola, Airbnb, Swisscom, Intel, PayPal, Twitter, Lenovo, and many others.17

Their success and ability to solicit so many contributions would be significantly reduced without such a strong community backbone and an environment where everyone plays on the same playing field. Although volunteers, they are effectively members of the team, and as such expect to be treated as members of the team. They care deeply about how decisions are made (such as in the working groups in the TensorFlow example), how people work together, when and where meetings are held, how trademarks can be used by the community, how the community is governed, and other related topics. I call these Inner types of community.

Contrast this with Apple’s and Google’s mobile platforms. App developers build on top of those platforms. They care deeply that the platform works, has great resources for how to use it, and gets exposure for their apps in the broader market. Because they consume the platform, they don’t feel as much ownership over how it is created; they mainly care that they can use it. This is an Outer type of community.

Speaking of which, ownership is a key distinction between Inner and Outer communities. In an Inner community the member feels a shared sense of responsibility and ownership in the project (hence wanting to be treated as a team member). In an Outer community members feel ownership of their app/product but not of the platform they are building it on. Think carefully about this relationship with ownership and how it affects your community.

Unsurprisingly, the care and feeding of these communities requires quite different approaches. The Inner needs to be carefully managed to create a team environment where everyone is treated equally in how they collaborate and work. Reduce the gaps between your staff and community members as best you can. You can never make everyone completely equal, as there will be certain business dynamics that make this more complicated (confidential contracts, security issues, etc.), but this is another North Star to aim for.

The Outer is about delivering a world-class platform that gets people up and running quickly and easily and where they are taken care of as content creators. Your primary goal should be an end-to-end experience with all the different pieces available and within easy reach.

CREATE A PEOPLE-POWERED MARKETING MACHINE

Unsurprisingly, all of these models have a remarkable domino effect on the marketing and awareness of your product or service.

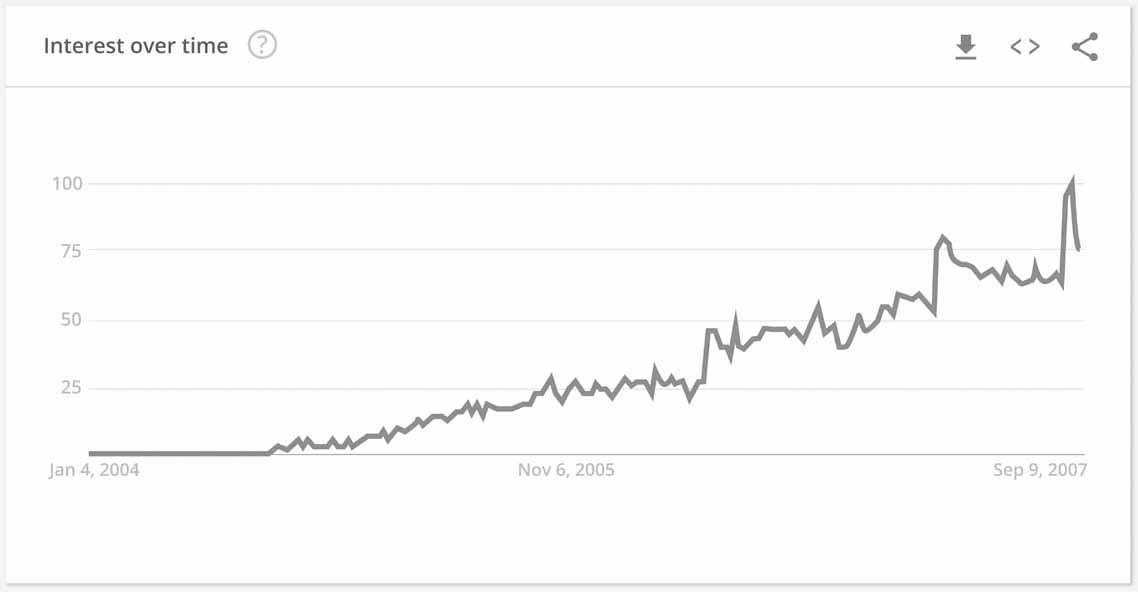

When Ubuntu was started in 2004, it gained initial traction. Then I joined in 2006 and started building out the community. While Ubuntu was a technology project, I didn’t want to merely attract the code-writing neckbeards. I wanted to be more ambitious and encourage different types of contributions, from engineering to support to documentation, as well as advocacy, events, and translations.

This diversity of participation, and therefore content, had a tangible brand impact. As one data point with the following Google Trends graph shows, as the community started kicking into gear, the word “Ubuntu” became more prominently searched for and surfaced in more searches.

Fig. 2.3: The growth of people searching for Ubuntu on Google.18

As the community produced more content and support, it broadened the surface area of material, which helped pull more people in from the outside. The brand was getting stronger.

This didn’t just widen Ubuntu’s reach and brand exposure; it also increased the value of the community itself. In addition to higher search rankings, our community experienced increased traffic, usage, and growth, which in turn generated more value.

Momentum builds momentum. Humans are attracted to things that clearly add value to other humans. Similarly, great service and experiences inspire people to encourage their friends to experience the same. This generates a referral halo.

An example of this is the tile installer who worked on our recent remodel. Danny doesn’t care about having a website or social media presence for his business, and he performs zero advertising. His entire business is fueled by referrals from his excellent work. This works because (a) we often want people who deliver great products and experiences to enjoy continued success, and (b) if we can have our friends enjoy this experience, it puts us in a favorable social position in the eyes of both our friends and the provider of the product/experience.

Now, this referral halo doesn’t just cover the individual experience but also group experiences. If you and a friend are walking down a street on a Saturday night, and you poke your nose into a restaurant where everyone is smiling and having a great time, and there is a table free, you will probably go in. Good experiences, particularly in groups, are infectious. This is how we build growth.

Now, we need to be realistic. If the restauranteur focuses only on good food and not on getting bums on seats, they will still have an empty restaurant. As such, you need to focus on building both meaningful value and driving consumption of it. This will help you to really harness this momentum effect.

HOW TO PICK THE RIGHT COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT MODEL FOR YOU

OK, enough talk about the models. Let’s now zone in on which ones work best for you.

It will come as no surprise that there is no one-size-fits-all solution here. I wish there was, as it would make my job infinitely easier (and cause less heartburn). For some of you, there will be a clear fit, but for others you may have a blend of multiple models in the same community. Blending multiple models is perfectly normal, certainly for larger communities. Either way, great communities start simple and then iterate and evolve.

A few months back I wrapped up an engagement with a company who had started a community the year prior. They initially wanted to go all-in guns blazing. They wanted people to provide support and guidance, provide feature feedback, produce art, deliver events, moderate and maintain forums, provide mentoring and more. In the wise words of AC/DC’s Bon Scott, it was a “touch too much.”19

Don’t do this.

Start simple, pick one model, and get cracking. Build your community based on the guidance I provide throughout this book and when you start seeing sustainable results, expand into other areas. You need to learn to walk before you run and then ultimately sprint.

Why? Two reasons. First, if you overcomplicate your first chunk of community strategy, it can become an unwieldy, wiry mess that is difficult to untangle if you get stuck or overwhelmed. This can be a huge headache, so starting simple reduces this complexity.

Second, the only way to learn this stuff is to roll your sleeves up and get to work. As you are new at this, starting simple gives you and your team time to learn and grow. Don’t overwhelm everyone with too large a plate of things to do. You will get better results if you have time to understand this work, digest how it is received, and be thoughtful in how you improve.

Let’s look at some common scenarios and which models are a good fit. This should give you a general sense of what kind of ingredients you will want to include. How we add those ingredients will be covered throughout the rest of the book.

Scenario 1: I want to build a community . . . where people are fans and users of my product or service.

Use a Consumer model.

Commonly this is delivered as a public discussion forum or channel where people can join, browse previous discussions, share their ideas and opinions, ask questions, and otherwise consumer-related material. This would be similar to our earlier TrekBBS example. You provide a simple, easy-to-navigate, virtual clubhouse for people to have discussions on a range of topics that relate to your product or service.

These kinds of communities are discussion- and content-driven with preproduced material (primarily coming from you) such as articles and videos, as well as targeted discussions. Plan to (a) provide an environment where people can have these discussions, and (b) produce content that will constantly pull people in, such as news, updates, events, and videos. This will keep people coming back for more, and when they do come back you should be engaging, inspirational, and encouraging.

Scenario 2: I want to build a community . . . where people provide help and support.

Use a Champion model.

This can apply to both an official community for a product or service, or an enthusiast-driven, unofficial community. On one hand, you need to provide a place where people can ask and answer questions but where you can also ensure previous questions and answers can be easily found. This then increases the reusable value of those solutions. The more we can reuse content, the greater value it offers. Fortunately, there are lots of ways to do this.

As an example, the Seasoned Advice community provides a place where people can post questions about all manner of different cooking, baking, grilling, and other culinary interests.20 Questions can be submitted, multiple answers are provided by the community, and then the question-submitter picks the right answer. These question-answer combinations provide an incredible archive of reusable questions, making it into a huge FAQ for cooking (and often these questions and answers pop up when people search on Google too!). There are similar communities for mathematics, music theory, homebrewing, and many more.21

You will also need to enable the community to produce precanned material and resources such as tutorials, videos, and online courses. Your members will need to be able to not just create this material but also publish it where other people can find it.

You will also want to ensure that you recognize and reward people who provide great support and produce great content. This will keep them coming back and build a sense of belonging (similar to our stock market video project example earlier).

Scenario 3: I want to build a community . . . where people create technology that runs on my platform.

This is the Collaborator model, but as we discussed earlier, it will be of the Outer type.

Your number one goal here is to provide a world-class experience in how new participants can get up and running building their technology on top of your platform. This experience needs to be simple, intuitive, and cover the varying needs of your audience. These developers could use any platform, so presume they have limited patience—get them delivering great results as quickly and easily as possible. As we cover later in chapter 5, it is critical that we test our on-ramps to ensure that they, y’know, actually work.

Simplifying the onboarding of new members requires two key areas of focus.

First, make building on your platform as simple as possible, such as ensuring you have a solid developer kit, documentation, and a place where members can ask questions and get help. Google does a good job here with their Android developer platform.22 They provide a downloadable Software Development Kit (SDK), code samples, testing/quality guidelines, and a library of documentation.

Developers should see results within a short period of time (such as thirty minutes). Ensure the onboarding experience is tight and focused. We will delve into onboarding in more detail in chapter 5.

Second, have a plan to incentivize developers to promote and raise awareness of their applications and working with your platform. Their testimonials of your platform are a good hook to bring other developers in.

Scenario 4: I want to build a community . . . where people create functionality and improvements to my product or service.

Use the Collaborator model and the Inner type within it.

Your core goal here is to create a great team environment for both your staff and community members. The more open you are, and the fewer differences between staff and community members, the easier the community will be to build. Everyone will get on and live in (mostly) perfect harmony.

Our earlier mentions of Ardour and Kubernetes are good examples of this. They provide clear, open collaboration and development. Many other projects, such as Discourse and Fedora, are similarly good examples.23

People need a way to understand what they can do to help, how to submit contributions and have them peer reviewed, where to get help when they need it, how to be involved in reasonable levels of planning and coordination, and other elements. If your staff are able to do this well and out in the open, you will already have a great starting point.

You will also need a clear leadership-and-governance methodology; this is commonplace in similar communities. It doesn’t mean you hand over the reins to the community, but you involve them in leadership where it makes sense (and where they have earned a place at the table). The leadership element is one of the most delicate balances to strike, and we will discuss it throughout this book. It is just like running a business: you want to ensure people feel invested and autonomous.

Scenario 5: I want to build a community . . . inside my company to optimize how people and teams work together.

Internal communities (often as part of digital transformation initiatives) can take a few different approaches. If your primary goal is educating staff to work more effectively and share approaches to solving problems, you should use the Champion model as discussed in scenario 2, but it would obviously be explicitly focused on an internal audience.

If your primary goal is encouraging different teams to collaborate together on shared projects, this will be a Collaborator model (the Inner type), similar in scope to scenario 4.

Ensure you take an extra level of care and attention in matching your community to the corporate culture and obtaining approvals from managers to have their teams participate. A financial services client I worked with on a digital transformation project had great results within a tightly insulated team, but he struggled to broaden out the initiative until all the necessary managers were on board. This required a lot of political maneuvering to build support, but then the work and results flowed much more freely.

You need to treat your internal community as volunteer in nature. Differentiate between requirements and requests. Some companies see an internal community member do good work and then load them up with extra work they have to do. This produces the opposite of your desired effect and can make people reluctant to join.

SIX FOUNDATIONAL KEY PRINCIPLES AND HOW TO APPLY THEM (AND NOT SCREW THEM UP)

At this point in our journey we are laying our foundations. Each Community Engagement Model provides a mold in which we pour a mixture of other ingredients that will help our community to grow.

Before we move on, there are six important principles you should follow, irrespective of which model(s) you are using and what kind of community you are building. Think of these as a tonic for keeping your foundation strong and healthy.

1. Start Simple and Build Valuable Assets

When an unknown filmmaker makes their first movie, it has value to them but it is largely worthless to other people. There are no fans, there is no platform. There is one asset, the film, that is unproven in the broader marketplace.

Communities are the same. Your brand-new community infrastructure and facilities will be unused, your new social accounts will have no followers, and your events will have no RSVPs. We have to start somewhere, and right out of the gate things are pretty barren.

When you build a new community, limit the number of moving pieces. Keep things simple, start small, and build up. Pick a few key components and build significant value around them. Expand later.

One community I inherited originally spent months putting together all manner of tools: a website, blog, six social accounts, wiki, mailing list, and more. If this wasn’t overkill, I don’t know what is. They spent more time discussing how these tools worked than actually doing anything that was constructive. What a waste of time and effort.

Start with a Minimum (read that word again) Viable Product, to provide just enough infrastructure and workflow to allow your members to generate value. Where possible, pick single solutions: one social network, one forum, one collaboration tool. Generate value, and then expand from there.

2. Have Clear and Objective Leadership

There is a cliché about people being either leaders or followers, but it is largely true. What’s more, there are a darn sight more followers than leaders in the world. Your community is going to need clear, decisive, and fair leadership. This will not just help you be successful; importantly, others will be guided by this leadership, often emulating it, and you want this to be driven by the right behavioral patterns and leadership.

This leadership needs to be clear, intentional, approachable, and objective. How you do this depends on your community. It could vary from a single leader right up to a complex set of leadership teams that represent different parts of the community. Again, start small and evolve.

Your leadership needs to be focused but approachable. Mårten Mickos is CEO of HackerOne, a security company in San Francisco. He has put their community of security researchers front and center in how they have built their business, and subsequently value, in the market.

A few years back HackerOne invited some of their most accomplished community members to a lavish-yet-intimate security event in Las Vegas. Mårten made it clear he was in service of their success. He wanted to learn their motivations, interests, and how he could help them; he was passionate about learning from them how he could be a better leader. He even fetched them drinks and snacks while they feverishly worked.

Like Mårten, great leaders listen, learn, and guide. They don’t dominate, keep people down, or control unnecessarily. A great leader is clear in the scope of their leadership and intentions, open and transparent in their actions, but can be private and nuanced when required. A great leader can help your community members to make decisions, resolve conflict, and always provide a calm, steady hand. Think carefully who you can put in place who possesses these attributes.

3. Clear Culture and Expectations

My wife and I know a couple who for years have argued like cats and dogs. While all marriages can get testy when kids, tiredness, and stress are mixed in, their Achilles heel has always been unclear expectations. “You were supposed to pick the kids up!” “You didn’t tell me I needed to be at the school at that time!”

This problem gets exponentially worse as you chuck more people into the mixing bowl. When people get together, culture forms. Within that culture are social norms that are expected to be adhered to but are largely unspoken. As the group grows, there can be a divergence of what these norms can and should be, which cause a significant amount of the interpersonal problems in communities and businesses.

It is essential to always set clear expectations and cultural norms in a community. There should be no ambiguity about your values and the social fabric of how the community operates. If you think everyone understands this, they probably don’t. You need to define this and constantly remind people of these values on a day-to-day basis.

This isn’t hard: it can be as simple as creating a document with a clear set of values that the community will always adhere to. I often recommend to clients that they create a Community Promise, which contains their core values that may be obvious to us but are important to boldly state. This often includes elements such as:

• We criticize ideas, not people.

• We treat people as equals and everyone is welcome in our community, irrespective of their gender, sexuality, political orientation, or otherwise.

• We judge contributions based on their individual merit.

• The vast majority of collaboration in our community happens openly, with limited exceptions for security or customer reasons.

• We believe in “fail forward.” We don’t demonize people for failure but embrace it to learn and improve.

Documents like this can clarify general principles and values, but it is critical not just that you enforce them (and be seen enforcing them) but also that there is a regular flow of information and updates to underline how the documents are in place and thriving. Remember: a critical part of the community “product” is a healthy, inclusive, engaging culture: you need to market and maintain that culture to keep it thriving. This culture has to be a malleable entity that everyone can positively influence.

I worked with a large financial services client in London last year. Over lunch an employee was bemoaning the indignity of spending every day in a cube, unable to influence the culture of the business. Influence is psychologically important to us, not just to validate our own work, but to build a sense of belonging in a group.

Focus on building a culture with clear expectations but one that is “hackable.” Regularly gather community feedback, learn from it, and refine standards of practice and workflow. Culture is evolved by its participants, not an unchangeable rulebook handed down by the gods.

4. Focus on Relationships, Trust, and Engagement

Life is all about relationships and trust. From our families, to workplaces, to friends: if you don’t cherish and build relationships, you are doing it all wrong. Also, your friends will think you suck.

Trust is the connective tissue in a relationship. You need to create an environment that doesn’t just solve problems but fosters relationships that can grow trust. This will build a skeleton on which everything else will flourish.

Your approach to this will significantly influence the success of your community. Don’t see your community members and teams as pure utility and function; they should be a network of relationships that form a strong human foundation in your community. It is these relationships that will reduce the dependency on your initial guidance and mentorship, and give community members the confidence to innovate and build new value in the community. It is critical you build this autonomy in your members; it is how you grow.

It is simple, really: invest yourself in other people’s success, be interested in their story, and treat them like equals. From there a healthy culture can form.

5. Strive for and Be Reactive to Insight

I am going to annoy a lot of product managers right now.

There is an arrogance in the halls of many businesses that the people sitting around the conference room table have all the answers. Elegantly drawn diagrams on whiteboards, oftreferenced TED talks and books, and other evidence tries to solidify their case.

Here’s the thing: when you build anything for people, including products, services, or communities, the answers to your questions live in the heads of your audience. We just need to tease them out in a form that we can act on.

Throughout this process of building a community you are going to have a lot of questions. As your experience grows, it can be tempting to think you know what the answers are, but you probably have a hunch at best. Your audience is the true source of wisdom, but they may not know it. Ask them questions, probe theories, and make yourself vulnerable to constructive criticism. It will benefit you significantly.

As part of this process, you have to be open to uncomfortable insight. You are going to screw up. Be stoic in the face of difficult-to-swallow feedback. Critical feedback is a good thing: it shines a light on a leaky hole in our sailboat. Doing this well not only plugs the hole but it builds remarkable trust with our community, trust that is often shared with others.

6. Be Surprising

Finally, the very best companies and communities always surprise their audiences (in a good way).

Ted Cruz, a prominent conservative politician, was once a guest on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, where he shared his opposition to a Supreme Court ruling on gay marriage.24 When the audience booed him, Colbert responded with “Guys, guys, however you feel, he’s my guest, so please don’t boo him.” Colbert, while a clear supporter of gay rights, surprised his audience. He felt it important to provide his guests with the ability to share their views unencumbered, even if he and others disagreed with them.

People need to be surprised, inspired, and challenged. This is not about being a cheap provocateur, but instead about always delighting your members and team with your ability to push new boundaries and enforce critical values. My example of Mårten Mickos earlier demonstrates this. Watching such an accomplished CEO take an interest in learning from his community (and grabbing them drinks), really stuck with people. It bucked the trend of how many people saw CEOs.

This is not just a key leadership skill. It will ward off stagnation and boredom as your community ages. Keep them on their toes. The right kinds of positive surprises will continue to build faith in your community’s ability to accomplish its mission, faith in you, and subsequently, faith in your vision.

TOWARD VALUE: ALL KILLER, NO FILLER

Jim Zemlin is the executive director of the Linux Foundation, an organization that facilitates hundreds of technology communities across the cloud, infrastructure, automobile, data, and beyond. In a recent discussion I had with him he touched on an important component of delivering this broader strategy, “A mistake some companies make is an unwillingness to give up any control.”

He continues, “This manifests in different ways, ranging from the community’s governance, funding, the identity of the maintainers (and whether there is a growth path for outside contributors), the openness of the project, transparency of decision making, and more. Companies must be willing to release some control of the project to the community, or they risk ending up with a pseudo-open project.”25

As we have covered so far, the authenticity of your community is critical. Key to that authenticity is building a collaborative environment where your community is empowered to do great work. For this to thrive you need to think carefully about this balance of power between your company and the community.

As Jim says, “Companies can still be leaders of the project without the tight control checks typically exercised in internal projects.”26 He isn’t wrong. The true test of your community strategy is not making people jump through hoops to approve their work, but instead making them want to jump through hoops to help them, you, and the rest of the community be successful.