CHAPTER 8

WORKPLACE SAVINGS, CAPITAL MARKETS, AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

Economists of every school have always recognized savings as the source of investment that fuels an economy’s long-term growth. Nations that have acted on this insight have gained powerful competitive advantage over time.

For most of this book, we’ve talked about workplace retirement savings as a vehicle for producing reliable income for life. And while America does have substantial shortfalls to address, what we’ve just seen in the previous chapter shows that we are actually much better positioned than many other nations to reach this goal.

That’s partly because our defined contribution workplace savings and IRAs are so huge—over $15 trillion and growing rapidly, notwithstanding ongoing cash-outs. But just as important as the volume of these assets is the nature of their ownership and how well they are allocated. And in all three of these respects, the United States is unique.

Defined benefit pension funds are owned by sponsoring entities and managed by fund trustees. Unless workers take lump-sum payouts instead of annuitized income (severing ties to the fund), all they really own in a DB plan is access to a promised income stream, not to the underlying assets that generate the wealth. And when pension funds find that they cannot meet their liabilities, as has too often been the case around the world in recent years, workers discover that the benefits they had expected to receive may not be there for them.

Workers in DC plans, by contrast, personally own the capital that they (or their advisors) can allocate into myriad investments, convert to annuitized income streams, or preserve to be passed on to their heirs or to charity. This is real ownership, a qualitatively different thing than a claim to a share of a traditional pension entitlement.

In terms of asset allocation, we have noted that most global pension funds are characterized by substantial fixed-income risk concentration, which, in an era of zero and even negative interest rates, raises any number of questions about retirement finance stability.

DC savings plans in the United States, however, are allocated to a wide variety of securities, which in part accounts for the speed with which they recovered in the post-financial crisis period. U.S. retirement assets fell sharply—by 22 percent—in the market dislocation of 2008. But they regained their 2007 peak by the end of 2010 and have been steadily increasing ever since.

U.S. workplace savings plans allow investors to directly participate in ownership of the private economy—through company stock, bonds, and other financial instruments. This may not be the “Pension Fund Socialism” that Peter Drucker forecast in the 1970s, but it is mass capitalism and worker ownership of the means of production, a new development that puts an interesting twist on the old idea of “class struggle.”

In this chapter, I’d like to step back to see the issue of retirement finance in a much broader context than we typically do. That means looking deeper into the catalytic role that rising workplace savings have played in growing America’s capital markets and the national economy.

Clearly, our capital markets generate returns that benefit workers in defined contribution plans. But this support system actually creates a virtuous circle. By providing vast, steady liquidity for stock and bond markets, 401(k)s, IRAs, and other retirement savings vehicles have become an essential source for American capital formation and helped the United States create a market-centered financing system that supplements, and surpasses, traditional commercial banking.

The Capital Markets System

Parallel with the rise of DC savings in recent decades, the United States has evolved a national financial system in which securities markets play a much larger role than traditional banks. We can see this by comparing U.S. and European financial models. In the European Union (for example, Britain), roughly 80 percent of corporate debt takes the form of bank loans, with just 20 percent of company finance coming from bond markets. In the United States, those proportions are reversed.

But nothing illustrates the difference in philosophy and financial architecture between the United States and other countries better than a comparison of equity markets and banks. While there are several individual countries around the world with robust stock exchanges, they are mostly outliers. In general, American companies are much more inclined to issue stock to secure a major share of their capital needs.

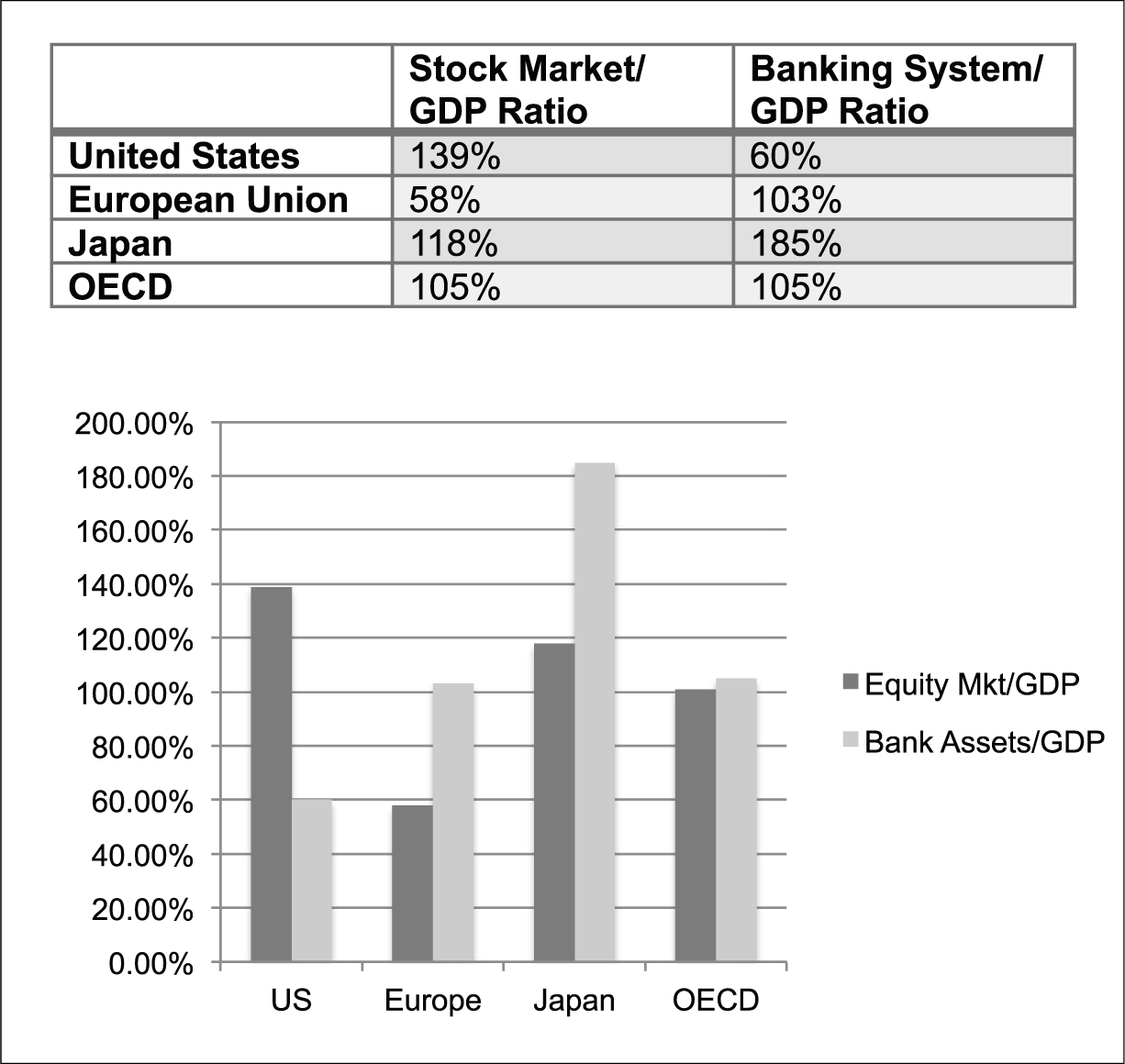

Comparing stock market capitalization and bank assets as a proportion of GDP shows that the United States is well over twice as “stock-intensive” as Europe, and that Japan is three times as “bank-intensive” as the United States (Figure 8.1). This discrepancy between stock market and bank intermediation also holds true when comparing the United States with the countries of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental body encompassing 35 of the world’s largest economies with an aggregate GDP of $51 trillion. The United States is 40 percent more equity-intensive than the OECD; the OECD is 40 percent more bank-intensive than the United States.

FIGURE 8.1 Stock markets vs. banks: the U.S., EU, Japan, and OECD

Source: Federal Reserve economic data.

The United States has vastly expanded all dimensions of its financial industry over recent decades, with this expansion paralleling the rise of funded pensions and workplace retirement savings. While the United States and the European Union are roughly the same size as economic entities (U.S. GDP is $18 trillion; the European Union’s GDP is $19 trillion), U.S. stock and bond markets are nearly twice as large as their European counterparts: $62 trillion as compared with $35 trillion in Europe. United States banking assets are likewise much larger—$60 trillion as compared with $34 trillion in the European Union.

The sheer scale of America’s financial system, and the fact that most world financial assets are priced and exchanged in U.S. dollars, provides deeper capital resources than most nations can imagine; it also allows for tremendous flexibility in times of systemic financial stress.

Following the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, for example, U.S. securities markets were buttressed by unprecedented central bank intervention when the Federal Reserve generated new liquidity, flattened interest rates, and quadrupled its balance sheet from $900 billion in the fall of 2008 to $3 trillion five years later, mostly by buying up fixed-income instruments and securitized debt.

This was clearly an extraordinary intervention, the reverberations of which are sure to play out over many years. We’ve already seen how the public-private hybrid structure of America’s retirement finance—Social Security plus workplace savings—helps diversify risk. Similarly, our financial system as a whole benefits from a fairly well balanced twin-engine structure of its own, combining vast commercial and savings bank assets with even larger equity and bond markets.

After the 2008–2009 crisis, it took several years for the American financial system to stabilize and recover. But our stock of total retirement assets bounded back to their precrisis level by 2010. Today, our $26 trillion stock of retirement assets continues to grow by about 5 percent a year and our economy, employment, and wage growth are recovering more rapidly and on a more secure financial base than those of many key global rivals. The capital markets-driven U.S. economy was clearly gathering steam by the mid 2010s. But as of year-end 2016, the more heavily bank-centric financial systems of Europe and Asia were growing more slowly, and their traditional pension systems remained very much under a cloud.

This differential in recovery and economic growth can be credited largely to the extraordinary flexibility, dynamism, and sensitivity of America’s capital market system, fueled as it is by steady flows of patient long-term capital from our workplace savings system.

Capital Markets and Banks

In any economic system, overall savings provide the funds to finance new business and real estate investments. But not all financial systems or forms of saving are created equal. The American capital market system, for example, has proven highly adept at capital formation generally, most especially in channeling capital into mechanisms that foster start-ups, innovation, and entrepreneurship such as angel investing, venture capital, and private equity.

These risk-seeking investors typically spread their bets among multiple ventures and entrepreneurial firms aiming to secure outsized returns from a standout success or two, while being able to wait out, or write off, multiple nonperformers. Every Google, Facebook, or Amazon emerges alongside hundreds of other start-ups that succeed on a more modest scale, get acquired by other firms, pivot to other strategies, or simply fail.

Unlike the capital markets, commercial banks can’t play much of a role in financing start-up companies. By law, they must restrict their lending to well-established, creditworthy customers and avoid unproven, high-risk ventures. Banks can’t collect outsized returns from successful clients. They are, however, very much exposed to the possible failure of any firm to which they lend money. But the ability to offset multiple losses with just a few outsized gains is the key to financing entrepreneurship in America.

American retirement savers provide the market liquidity that enables entrepreneurs and their backers to incubate and launch new ideas. That’s because when venture investors finance a start-up, they are looking forward to the day they can take that firm public with an initial public offering (IPO). And even if few retirement investors directly buy IPOs, U.S. equity markets are primed to embrace these new companies precisely because of the trillions of dollars in retirement savings that flow through them every year.

That’s one reason why America’s IPO market, while highly variable year to year, has averaged some $150 billion a year since the dawn of this new century. This influx of disruptive new competitors is, in large measure, why the lists of leading firms on the NYSE or NASDAQ change so much from decade to decade, while in Europe and Asia, established corporate brands dominate industry sectors for generations.

Even the failures among new businesses in the United States keep our economic system nimble. By introducing new ideas and business practices (such as online brokerage, alternative energy, mobile computing, and driverless vehicles), start-ups often force “incumbents” to stay sharp and innovate, or fade.

Many an S&P 500 company has opted to, in effect, “disrupt” itself by closing down mature, high-margin business lines in favor of emerging (and potentially larger) narrow-margin markets, all to avoid being pushed out of the way by energetic and well-funded start-ups. This has happened in wealth management and retirement savings throughout my career, where this process of industry reinvention is—if anything—accelerating.

Workplace Savings: Fuel for Capital Markets

Some believe that economic dynamism and bold innovation are disruptive or destabilizing. And in less flexible, bank-centric financial systems, this may well be the case. But in the American system, while being displaced by upstart competitors isn’t always comfortable for established firms, it is part and parcel of the creative destruction that serially razes and rebuilds corporate America, lifting the efficiency and productivity of the whole economy in the process.

This is how economic dynamism connects to, and depends on, robust workplace savings. In part because we have so many trillions in workplace savings absorbing mainstream equities and bonds, the United States also has the world’s deepest market for alternative investments, with private equity, venture, real estate, and hedge funds worth some $3 trillion—fully half of all the alternative assets under management on earth.

While risk-engaging pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and high-net-worth individuals are out investing in disruption, our workplace retirement system deploys assets in a less glamorous but equally vital way, investing in every corner of our stock and bond markets with long-term patient capital, staying in place for decades and forming the bedrock of America’s capital markets.

This synergy between retirement savings and American capital markets has been growing for decades. By channeling vast sums of money from many millions of workplace savers into our capital markets, America’s workplace saving system has become central to our whole economy’s growth (Figure 8.2).

FIGURE 8.2 Retirement savings can fuel capital market growth in what becomes a virtuous circle

Source: Lenny Glynn.

Decades of Growth

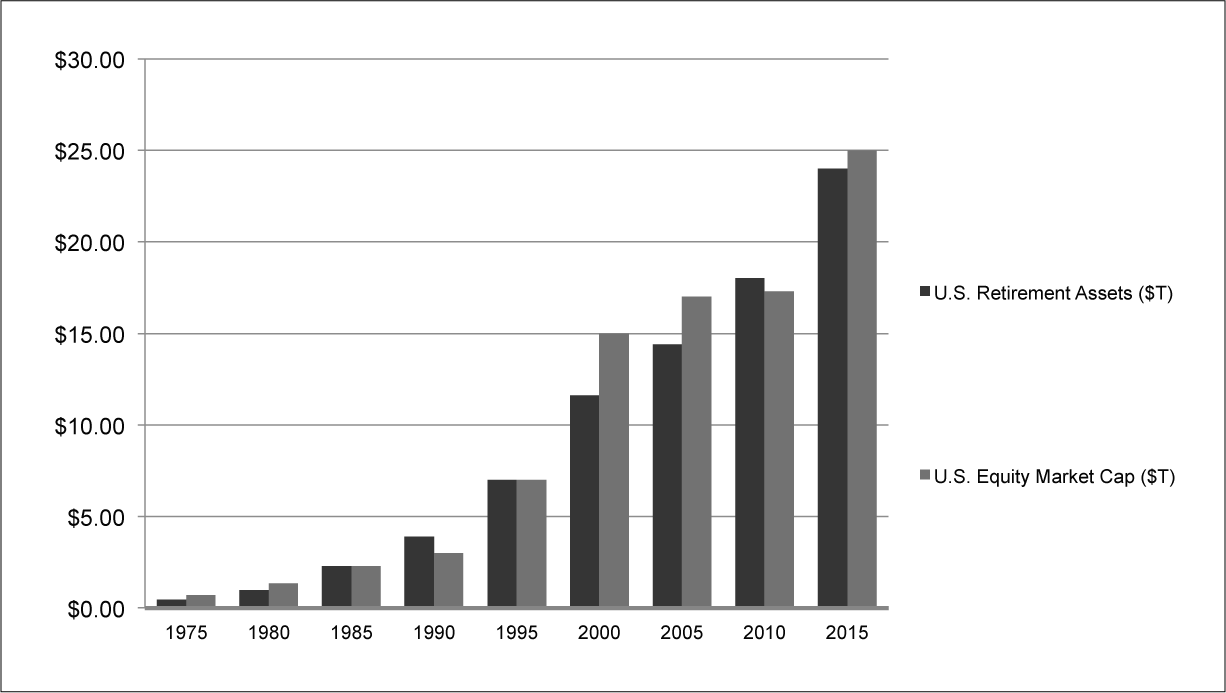

Since the passage of ERISA in 1974, DB pension funds and the newer DC plans that emerged to supplant them have driven wave after wave of savings into U.S. capital markets. America’s total stock market capitalization, for example, has surged from some $700 billion in 1975 to over $25 trillion today. As a share of the overall economy, stock valuation has grown from 40 percent of U.S. GDP to 146 percent of GDP over the same period.

When you compare the rising market capitalization of American stock markets with total U.S. retirement savings over the years, it’s clear that these two systems have been marching in near lockstep in a virtuous circle. This is no coincidence: U.S. retirement assets are fueling the stock market, and a rising stock market is driving up U.S. retirement assets.

This remarkable form of mutually supportive retirement savings capitalism has not yet been achieved in any other country—with the possible exception of Australia, which has a mandatory national savings system to which all workers must contribute at least 9 percent of their salaries. This has given Australia the highest level of per capita managed assets of any country.

The ratio of total stock market value to national GDP is often used as a rough proxy to measure the difference in capital market “intensity” between the United States and the rest of the world. One glance shows that stock markets play a much greater role in the U.S. economy than they do in the world as a whole. This is because U.S. equity markets have been infused with trillions of dollars in savings by tens of millions of working people, while most other developed country retirement systems still rely primarily on tax flows into pay-as-you-go structures that may transfer payments directly to retirees without those funds ever being productively invested. Few other countries have anything remotely comparable to the way American workers’ savings flow into our capital markets and help our economy grow (Figure 8.3).

FIGURE 8.3 U.S. retirement assets and U.S. equity market cap

Sources: Investment Company Institute, Federal Reserve, and World Bank.

Just as U.S. retirement savings and capital markets rose together, the absence of a well-funded retirement system in other developed countries means that their capital markets too remain relatively underdeveloped (Figure 8.4). Without access to the massive investment flows generated by funded pensions and workplace retirement savings, most other countries effectively starve their capital markets of investment liquidity, leaving their economies overwhelmingly dependent on rigid, risk-averse bank lending.

FIGURE 8.4 U.S. and world equity markets/GDP

Sources: Investment Company Institute, Federal Reserve, and World Bank.

Let’s recall that U.S.-funded pension assets account for fully two-thirds of the $36 trillion in retirement assets controlled by the world’s top 22 pension markets. The U.S. system of funded retirement finance, at $26 trillion, is about 10 times the size of Japan’s, the second largest market. And in Japan, as in many other markets, pension assets are primarily invested in government debt, exposing savers to highly concentrated sovereign risk. U.S. retirement assets, on the other hand, are a masterpiece of diversification, with tens of millions of individual portfolios allocated across innumerable stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other instruments.

Expanded Savings and the U.S. Economy

This tight relationship between retirement savings, U.S. capital markets, and economic innovation and growth makes it clear that the Workplace Savings 4.0 reforms we explored in Chapter 6 would do far more than just provide additional financial assets for American retirees. By engaging tens of millions more American workers in capital market investing, these reforms would generate trillions of dollars in new flows into our capital markets and produce strong tailwinds for future economic growth.

According to estimates by EBRI, the Workplace Savings 4.0 reforms we described would inject an additional $700 billion annually into workplace savings plans, accelerating their annual growth by fully 10 percent, from 5 percent to 5.5 percent. By 2025, this would, in turn, inject an extra $5 trillion into overall workplace savings, raising projected assets from $33 to $38 trillion.

To gauge the economic impact that higher savings rates in the United States could have, Putnam Investments, together with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, AARP, the Aspen Institute, the American Society of Pension Professionals & Actuaries (ASPPA), and other financial industry partners, cosponsored a 2014 study by the consultancy Oxford Economics entitled “Another Penny Saved: The Economic Benefits of Higher U.S. Savings.”

As the title of the study suggests, the results showed that even small adjustments in savings behavior by tens of millions of workers across a system as large as the U.S. workplace savings market can have a profound long-term impact.

Using data from EBRI, the report’s authors found that America’s savings gap was centered primarily on lower-income individuals and families, particularly the lowest income quartile, where savings would have to increase by about 21 percent of pretax income to achieve economic and retirement security. This demographic group is made up mainly of people who most often lack access to any form of workplace savings plan. Closing that coverage gap is, of course, Workplace Savings 4.0’s top policy priority.

Besides extending savings coverage to as many workers as possible, the Oxford study also recommended that all existing savings incentives and vehicles should be preserved and made more effective through the near-universal adoption of fully automatic plan design and significantly higher savings rates.

The report drew a close parallel between long-term individual economic security and long-term national economic prosperity and urged that public policy never pit personal solvency against national solvency in a misguided quest for fiscal savings. This is precisely the counterproductive push-and-pull between governments, corporations, and individuals competing for scarce capital that we mentioned in the last chapter.

Those of us working in the retirement savings industry have always known that retirement savings were a critical source of liquidity for America’s capital markets. With total DC plan and IRA assets worth $15 trillion and expanding, net of redemptions, by more than $850 billion a year, how could this not be the case? But the report confirmed what many of us had long believed—that a strong, steady flow of personal retirement savings plays a vital role in the health of the national economy as a whole.

Mobilizing their working population’s assets to finance investment can thus be a critical source of competitive advantage for any nation that gets savings policy right.

“Another Penny Saved” suggests that the optimal, healthy range of investment for the U.S. economy is in the range of 20 to 25 percent of GDP. But despite the growth we’ve seen in workplace retirement savings plans, Americans’ personal savings rate has slipped from about 14 percent of disposable income in 1980 to about 5 percent today.

So the United States has had to look abroad for much of its economic fuel in recent decades, borrowing extensively from nations with higher savings rates and selling off a substantial share of our own assets to foreign investors. American households’ ownership of nonfinancial capital market assets has declined from over 80 percent in 1970 to 60 percent today. Over the same period, foreign investors’ share rose from 3 percent to 20 percent. (Foreign flows accelerated in the years after the global financial crisis as investors scrambled to acquire safer, U.S.-dollar-denominated assets.)

This means we have some real work to do. But the Oxford study suggests that if we could boost the overall investment level in the economy to an average of 22.5 percent, with that rise funded by higher household savings, we could increase America’s projected 2040 GDP by around 3 percent, a gain equal to an additional net present value of $7 trillion, roughly 40 percent of today’s annual GDP.

This expanded savings would generate greater household wealth, accelerate national economic growth, and, by reducing our dependence on foreign investors, better insulate U.S. capital markets from international capital shocks.

The Ownership Society

American workers already have a significant stake in financial assets, and an interest in public policies that foster economic growth on new business formations. And as the wages-to-wealth mechanism of retirement savings deepens and broadens to cover nearly all American workers, it will take us even further toward becoming an ownership society.

The mere fact of having any savings or real assets at all offers a wide array of positive benefits to individuals, families, and society as a whole. Multiple studies have shown, for example, that ownership of even a small amount of financial assets can have a significant effect. Low- and moderate-income students with even low levels of savings set aside for college are three times more likely to enroll in college and four times more likely to graduate than students with no savings at all. These positive effects work even for families who didn’t send their children to college, but who do have some assets saved.

To link family aspirations to the power of America’s financial markets, elected officials have proposed legislation that would establish universal child savings accounts or “baby accounts” that would set every newborn on the road to a lifetime of savings and asset creation.

We’ve also seen proposals for expanded child tax credits that would incentivize families to save for their children. On reaching age 21, young people could use this money to pay for college, make a down payment on a home, or roll it over into a Roth IRA. Either way, this universal approach would provide every American child a first step down the road toward personal development and financial self-reliance, with important secondary effects for our society.

Wealth inequality is much in the news of late. Many seem to believe that our country is dividing into two Americas, one with financial assets and one without. Worse, the policies used to stabilize financial markets in recent years haven’t directly benefited Americans who don’t own financial assets. And those outside the system are increasingly frustrated by this inequality of financial opportunity.

This is unacceptable. But the most powerful tool that we can deploy to address this wealth disparity isn’t the redistribution of wealth via the tax code, but concerted private/public collaboration in the creation of financial assets for all Americans.

Giving everyone an opportunity to take a personal stake in the continuing growth of U.S. capital markets would be a major economic, social, and political step forward. We need to ensure that all citizens have a real, tangible stake in free enterprise so that they support pro-growth public policies. Then we need the policies to make the growth happen.