Chapter 4

The humor divide: Class, age and humor styles

“Jokes, that’s not humor”, said Bart Winia, a 33-year-old graphic designer, when I interviewed him. “That’s why I thought it was awful back then when your letter came saying you were doing research on humor, and based it on jokes.” For Winia, and many like him, the telling of jokes has nothing to do with humor.

The joke tellers I spoke to all found that telling jokes was almost identical with a good sense of humor. When I asked one of them, 25-year-old technical installer Richard Westbroek: “Do your friends have the same sense of humor as you?” he answered: “Yeah, you could say they tell the same types of jokes.” And Christiaan van der Linden, a 35-year-old administrator described himself: “I think that I’m pretty down-to-earth but I have a good sense of humor. Actually I can really tell jokes well but can’t laugh very hard at them. You’ve got people who can’t tell jokes but laugh up a storm when they hear them.” Note how van der Linden equates sense of humor with telling jokes (his own) and laughing at jokes (by others).

“Sense of humor” is a term that, just like “style”, “taste” and “class”, is used in both the descriptive and the appreciative sense. When someone is said to have a sense of humor, this means: a good sense of humor. The next chapter will explore what people mean by this. But people also speak of an unusual, special, nice, original, irritating, revolting, coarse, absurd or refined sense of humor. “Sense of humor” then indicates a certain style or taste in the area of humor. People have widely divergent ideas about what nice, good, funny or rather irritating, uninteresting, unfunny humor is. They have different tastes as far as humor goes, different humor styles.

Some people have a humor style that includes a preference for jokes - for them a joke teller is someone with a sense of humor. But there are also tastes in the area of humor that exclude jokes. In the preceding chapter, people were quoted who did not like jokes, but did like irony or humorous anecdotes about actual experiences. A shared humor style - a shared interpretation of a good sense of humor - is crucial to a successful humorous exchange. If people differ too much from each other in this, a joke can almost not succeed.

This chapter describes Dutch humor styles and their relationship to the joke. Like communication styles, these humor styles are connected with social and cultural distinctions. The thrust of this chapter, like the preceding one, is style difference: a broader preference for a certain type of humor, a certain style or atmosphere that can be found in divergent jokes, performances, humorists and situations. I will begin my exploration of this style difference with examples of standardized humor, including comedians, writers, and television programs.

Humor styles: High and low, old and young

The results of the questionnaire are the starting point for my exploration of Dutch humor styles and their relationship to the joke. By looking at the patterns in the survey responses, we can identify humor styles. In the questionnaire I not only asked people to judge a list of jokes, but also asked how humorous they found certain television programs, comedians and writer. Not all these persons and programs were exclusively humorous. I included, for example, Gerard Reve, who is primarily a writer. Ron Brandsteder, the presenter of Moppentoppers, was added because he was emphatically put forward as the humorous face of commercial television station RTL4. All persons and TV programs mentioned here are described in Appendix 2 at the end of this book.

These judgments I analyzed with statistical techniques for tracking down correspondences in groups of data: if people like a certain comedian, which comedians or television programs does they like as well? Different analytical methods ultimately gave more or less the same - simple - answer: the analysis turned up four distinct groups of humorists and television programs.

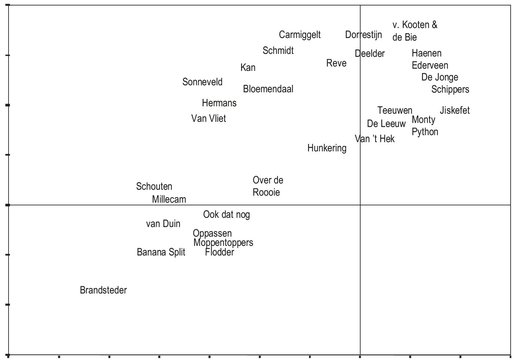

A graphical representation of these groups can be found in Figure 1. In this figure, three partially overlapping groups can be recognized. The first group I call veterans, represented in the top left quadrant. This consists of older writers, comedians and comics. Some of them were deceased at the time of the survey: Simon Carmiggelt, Wim Kan, Annie M.G. Schmidt, Wim Sonneveld and Max Tailleur. The people in this cluster who were still alive had been comedians for a long time, and mostly have a rather traditional style: Toon Hermans, Paul van Vliet, Adele Bloemendaal and Tineke Schouten. The appreciation for this cluster is connected with age: the older one was, the funnier one found them. There is no relation with the average appreciation of the jokes in the questionnaire.

A second cluster, the celebrities, is not clear in Figure 1 but apparent from the factor analysis shown in Table 3. Appreciation for this cluster was also connected with age but inversely: the younger, the funnier. This group includes three very well-known comedians, Freek de Jonge, Youp van ’t Hek and Paul de Leeuw. This cluster was appreciated slightly more by men than by women and is the only cluster to show a gender effect. While men and women appreciated de Leeuw equally, van ’t Hek en de Jonge are considerably more popular with men. Again, the appreciation of these humorists was unrelated to the mean evalution of the jokes.

In addition to these two clusters connected with age, I found two groups connected with educational level. The first of these tastes includes comedians/actors André van Duin, Sylvia Millecam, Ron Brandsteder, Tineke Schouten, Max Tailleur and the TV programs Banana Split, Flodder, Moppentoppers, Ook dat nog, Over de roooie and Oppassen! This cluster overlaps with the veteran cluster to some extent. These humorists and programs are found in the lower left of the figure. The lower their level of education, the funnier respondents found the humorists and television programs in this group. The appreciation of this group is strongly connected with the appreciation of the jokes in the questionnaire. The humor of the people and shows in this group often has to do with jokes: Moppentoppers, Brandsteder and Tailleur are all about jokes; whereas comedians van Duin and Schouten often tell jokes disguised as a sketch, or included in a monologue.

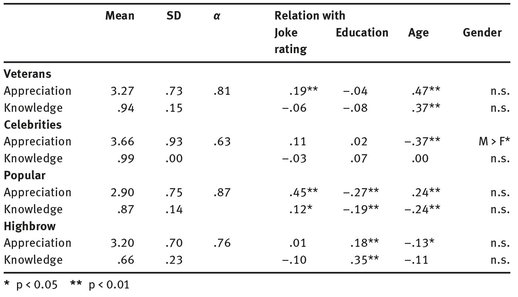

Table 3: Humor styles, social background, and joke appreciation.17

Appreciation was judged on a 5-point scale. Knowledge of items in a taste is represented as a scale from 0 (knows none) to 1 (knows all).

The final taste is connected more indirectly with educational level. This cluster, in the upper right quadrant in the figure, contains six television programs of which five were (predominantly) screened by the public VPRO broadcasting corporation: Jiskefet, Haenen voor de nacht, Van Kooten en de Bie, Monty Python and Absolutely Fabulous. The last television program in this group is De hunkering [The Yearning], a rather unempathetic dating show presented by Theo van Gogh that was aired only in 1997, the year I sent out the questionnaire. This group also includes the following cabaret artists/poets/writers (some are difficult to classify): Jules Deelder, Hans Dorrestijn, Arjen Ederveen, Wim T. Schippers, Freek de Jonge, Annie M. G. Schmidt and Gerard Reve. Hans Teeuwen belongs to this group as well. Relatively unknown at the time of the research, he went on to become one of the most popular comedians of the Netherlands. This rising popularity has diminished the rather exclusive aura he still had in 1997, and in later years he would likely have joined the celebrities.

The appreciation of this fourth group is somewhat related to educational level. The influence of education lies not so much in appreciation as in renown: the percentage of humorists and programs respondents said they knew, irrespective of what they thought of them, was connected with education. Many of the less educated group did not know the items in this cluster and thus had no opinion about them. This connection exists too for the individual items: the appreciation of none of the humorists/television programs in this cluster correlated with educational level. However, with the exception of de Jonge (whom everyone knew) and De hunkering (that almost no one knew), the respondents who did know the humorist or the program were significantly more educated than the respondents who did not know them.

These last two tastes are best described as highbrow or intellectual and popular or lowbrow humor. I am aware that these are not neutral designations. This problem of loaded terms is inherent in research into taste. Taste difference is by definition not neutral, because it is connected with social status. The associations - both positive and negative - called up by these terms are largely the same as those called up by the type of humor in these styles. These are precisely the associations and distinctions that form the heart of this chapter, maybe even this whole book: distinctions having to do with taste, class and other social differences.

The most problematic concepts are the terms having to do with low taste. While “highbrow” sounds quite elitist, this concept has social hierarchy on its side. Referring to tastes as lowbrow or popular quickly reeks of snobbery, and its Dutch equivalent, volks (literally: popular, common, working class, of the people), is even more dubious. However in the field of humor people often see these terms as positive. A Moppentoppers editor told me that they produced “real popular humor” [echte volkse humor], for “the man in the street” - and he was clearly proud of this. Toon Hermans has always preferred to advertise himself as a “comedian for the common man” [volkskomiek]. Shortly before he died, Hermans proudly described himself as someone who was definitely not a cabaretier. Instead, he said: “My humor is meant for the common man and will always stay that way” (van Bilsen 1999).

Several interviewees stressed the positive affinity between humor and lower class, often using the word volks to describe both themselves and their humor. Four of the joke tellers proudly said that they were “real boys of the common folk” [volksjongens]. Others told stories filled with nostalgia about the “working-class neighborhood” [volksbuurt] they came from. In these stories featuring neighborhoods and common folk, humor played a large role: the word volks evokes a good sense of humor.

As longshoreman Albert Reiziger said: “Crooswijk is Rotterdam’s salt-of-the-earth neighborhood and that’s where I come from. I think Crooswijk, being the working-class district it is, has more humor than the gentlemen’s hangouts on the canals, don’t you? A neighborhood like that, just like in Amsterdam, most humor comes from there, I think.” Common neighborhoods [volksbuurten], common men [gewone mensen] and working-class pubs [volkskroegen] – all these call up associations with jokes, laughing and a sociable atmosphere.

The feeling that humor is connected with common people was regularly expressed in the interviews. It was behind the words of Jaap van Noord, cited in the previous chapter, “that at the University a bit more laughter could be a good thing”. It played a role too in the words of the 52-year-old shipwright at a wharf who talked about “a yearning at the top for diversion”:

We’ve all got nicknames [at work], Tough Tony, Wild Woody, that sort of thing. Yeah, that’s what we call each other. You probably don’t do that at the university. I was on the works council for a while and got to talking to the director and well, I couldn’t really avoid the nicknames, could I? He got curious and wanted to know all about it. He thought they were really funny and ended up asking me for a list. Well, I didn’t mind, did I? Just goes to show you that there’s a yearning at the top for diversion.

This sentiment was most clearly put into words by graphic designer Bart Winia, one of the upwardly mobile group from, in his own words, “a working-class background”:

I noticed it at the art academy too, you know: people often see humor as something for the lower classes. I think I’d never have been able to finish university and then I’m only talking about the atmosphere there. Yeah, it’s not a big thing if you feel good in a bit of a sterile atmosphere - it seems sterile to me anyway - if you feel okay with that then there’s no problem. But I’m glad to go off with some friends on my motorcycle now and then, that’s a different atmosphere altogether. And I’ve trained in gyms and trained others too and that’s another kettle of fish entirely, isn’t it? And the guys behind the stalls on the market, they’re a real laugh.

But my question is, and maybe this is what your research is all about: what happens to the ones that went off to college, what’s the psychology behind the fact that they treat humor the way they do? Listen, I’m not saying they’ve got to go around telling jokes all day long, but I think they’re awfully inhibited when it comes to a good laugh. Because I’ve been to parties on account of my girlfriend [university graduate, GK] and, well, you’d be hard put to detect any humor going on at them. That’s so strange to me because it’s such an easy way to get to know each other.

(Bart Winia, 33, graphic designer)

Popular, lowbrow, and common are therefore not exclusively condescending terms, particularly where humor is concerned. They call up a mixture of positive and negative associations that penetrate to the essence of what I hope to discuss here: the relations between style and class background.

The evaluation of humorists and television programs is connected with two social divisions: highly and less highly educated (meaning college education or higher versus no college-level education), and old and young. Gender differences played a surprisingly small role. As is apparent from the figure, the oppositions intersect: in a diminished way, the high-low educational level is seen again in the veteran cluster. The two mainstream cabaretiers Wim Sonneveld and Wim Kan occupy a central position in this cluster, between the highbrow writers Schmidt and Carmiggelt and the more popular performers Hermans, van Vliet, Tailleur and Schouten.

Preference for and aversion to veterans and celebrities are primarily connected with humorous content and in particular moral boundaries. Many older people reject de Jonge, de Leeuw and van ’t Hek because they find them crude, while younger generations cannot appreciate the older humorists because they don’t understand their references, or because they find them corny, slow or sanctimonious. Thus, age differences have to do with differing “thresholds of embarrasment” (Elias 2012; Wouters 2007) Additionally, many young people don’t even know these humorists because they are from “before their time”.

However, style and content cannot be easily separated. The coarseness so often complained of by those who are older is not only a question of differing pain thresholds, but also has to do with pursuing shock effects: a humorous style that became popular in the 1970s. This humor style - a preference for a specifc humorous technique or effect - determines expectations of content.

The high-low distinction is the result of a more fundamental difference in humor style: it points directly to different understandings of what good humor is or should be. The unfamiliarity with the elite cluster is not as easy to explain as the unfamiliarity with older humorists, for whom some people are simply too young. The humorists and television programs in both clusters are available, in principle, to everyone; after all they all are shown on television. The difference between these two types of humor lies not in content but sooner in tone, approach, design, presentation and more generally, in the atmosphere it exudes: in style.

Not all humor allows itself be sociologized easily: approximately a quarter of comedians, comics and television programs on the list fell outside the four humor tastes. That is not to say that they were not valued, only that there is question of more specific taste variations that cannot be connected with a broader taste or social background. This is true, strikingly enough, of almost all non-Dutch television programs. Programs as diverse as Cheers, Friends, Laurel & Hardy, Married with Children or Tom & Jerry, all of which have been successful on Dutch TV, could not be connected with the appreciation of other programs or with social background. A number of Dutch humorists did not fit one single taste either: popular comics such as Harry Jekkers, Brigitte Kaandorp and Herman Finkers placed neither in the old-young nor the high-low category.

Sociologists and laypersons alike have stated that tastes are becoming more and more diffuse in these “postmodern” times, that people have lots of space from which to choose their own style, that social background no longer has such an impact, and particularly that classical contrasts between high and low culture are increasingly disappearing. Marketing and promotional research switched some time ago to a much more intricate partitioning into lifestyle and “orientation” that have little to do with simple sociological background variables.18 In various corners of sociology, the death knell has been sounded for class as a useful theoretical concept (e.g. Pakulski and Waters 1996; Beck 2002). From this perspective, the (double) dichotomy I found was surprisingly simple: apparently, simple sociological background variables go a long way in explaining something as “personal” as sense of humor.

Style, status, and knowledge

The double taste division apparent from the questionnaire points to the existence of class cultures and age cultures, with accompanying taste and style differences. Class cultures, however, have to do with status: highly educated people reject the taste of those without a college education, while their own style of humor remains inaccessible for those with a lower status. The highly educated group even manages to keep its judgment of others’ humor styles outside the other group’s reach. Lovers of popular humor are as little aware of the status of this humor in the eyes of those who love highbrow humor as they are of the fact that the joke is so little known in highrow circles. This pattern of rejecting the other and making one’s own taste inaccessible typifies elite taste. It is evident also in classical music and literature. High taste is exclusive in the literal sense of the word: it excludes people (Bourdieu 1984; Bryson 1996; Gans 1999).

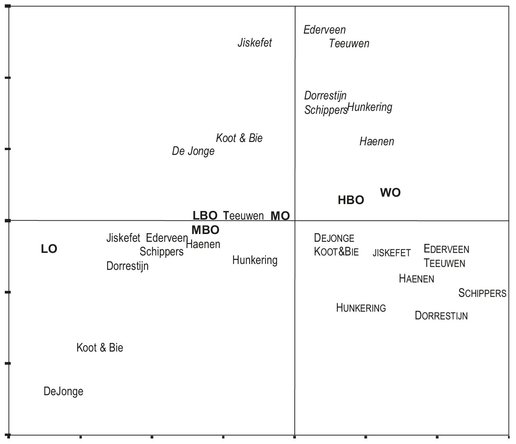

The less highly educated respondents often didn’t know the humorists and the television programs in the highbrow cluster. The relationship between knowledge and appreciation is asymmetrical: the highly educated group do not like the humor of the less highly educated group; but the less highly educated group do not even know highbrow humor. Although highly educated people are not always completely aware of lowbrow humor, this effect is much less pronounced. How this works is can be seen in Figure 2, showing the appreciation of and familiarity with highbrow humorists and television programs. Familiarity with highbrow humor is connected with education; within the highly educated group, part does and part does not appreciate such humor. One could say that a high educational level is a prerequisite for coming into contact with highbrow humor, and from that point on people can decide whether they like it or not. A comparable figure for popular humor (not included in the book) shows a much less ambiguous relationship between educational level and appreciation. The “not knowing” is in any case much rarer, since practically everyone knows the humorists and the programs in this cluster.

A question that may sound like a tangent: how do people move through the media? This is a broader question than that of how people make choices from available television shows. It is about the way social position influences how people become aware of the existence of cultural phenomena, from Moppentoppers or Hans Teeuwen to the newest joke. In the case of jokes, the acquisition pattern can be understood as a direct result of social networks. If you are in the wrong social environment, you seldom hear jokes. But for humorists and television programs, this is more difficult to imagine. Everyone in the Netherlands gets the same television programs beamed into their living rooms. Apparently people are only aware of a portion of what the television brings in.

Before I go further into the question of why people find something funny, the question of how certain types of humor enter a person’s field of vision must therefore be asked. A useful example to consider is that of TV maker/actor Arjan Ederveen. Shortly before my first interviews, he had caused a sensation in my social surroundings (mostly university people) with Dertig Minuten [Thirty Minutes], a series of slow, carefully acted, fake documentaries (“mockumentaries”), for which he won various awards. The most famous episode is probably “Born in the wrong body” [Geboren in het verkeerde lichaam], about a farmer in the rural province of Groningen who submits to a race-change operation: he is surgically reshaped into an African. Parody would hardly be adequate to describe this episode, which carefully sustains the tone of a documentary about a radical psychic and physical transformation. The program itself provided no hints of fictitiousness, making it difficult to tell whether this was intended humorously.

The questionnaire shows that only 51 percent knew Ederveen. Among the joke tellers almost no one knew him and the few who did were simply not interested: “Once, long ago, I saw the program”, said Gerrit Helman, one of the joke tellers, 26 and working in logistics, “after that I never watched it again. I don’t really know it at all. It doesn’t do anything for me.” Comparable uninterested comments were made about other people and programs in this cluster, such as this one by Kees van Dokkum (52, doctor) about Hans Dorrestijn: “It doesn’t do anything for me. He stands there crooning on television and then I go yeah, could be, but it’s simply not for me. Not even the character because I just don’t care at all, but no, it doesn’t do a thing for me. I don’t have the antennae, I guess.” This is how highbrow humor stays outside someone’s field of vision: a program or a humorist leaves someone unamused, untouched but not irritated or angered either. There is no specific objection to content, or to the comedian or humorist. Often the program simply doesn’t register: one doesn’t even remember having seen it. It doesn’t “do anything” for people - the humor doesn’t, and neither does the person, the story, the theme or the style. Better known humorists and programs from the highbrow cluster were often rejected on similar grounds: not based on concrete objections but because they “didn’t do anything” for people. The tone here was often somewhat hesitant: “I don’t know, maybe I don’t like their faces or something”, said Claudia van Leer (62, homemaker, married to a truck driver) about the satirists van Kooten en de Bie. Even more vacillating, by Ton Linge (61, retired editor): “van Kooten en de Bie. Yes. No, it could be that it was too highbrow for me, I don’t know. Or they’re too sharp or something. I didn’t like them”. People rarely have an argument or even words to explain what they don’t like: they see it and nothing happens.

What they do see, if they happen to watch by accident, is often surprisingly different from what I have always thought I saw (and what I am rather sure was the authors’ intention). On the topic of van Kooten en de Bie, 60-year-old sales representative Ivo Engelsman said: “If they’re both dressed as women, well, someone else might like that but it doesn’t say anything to me. It strikes me as a bit strange. But someone else could be lying on the floor, hahaha [fake laughter] really funny.” He is talking here about van Kooten and de Bie’s impersonation of two snooty ladies with pearl necklaces, in whom I had always seen very convincing personages. Engelsman sees a cheap humorous trick: a man in women’s clothes - a pretty banal form of humor, indeed.

A remarkable exclusion mechanism is at work here: people look at the same thing but see something completely different. Or, more accurately: they see nothing in it. Apparently there is something about the humor in the highbrow cluster that makes a great number of people, including a portion of the highly educated, lose interest acutely. This disinterest is a spontaneous reaction, almost as direct as laughter or indignation. It is, indeed, as van Dokkum said, a question of “antennae”. This comes close to what Bourdieu (1990) calls habitus: the embodied tastes and disposition that reflect social position and trajectory. Elsewhere, I have described these disinterested and puzzled reactions as “despondent readings”. This was intended as a critique of the cultural studies tradition that tends to look for agency and resistance in marginalized people’s readings of mainstream culture (Kuipers 2006a). Instead, highbrow comedy at times does not even provide enough clues to enable resinstance among those not “in” on the joke.

To be able to appreciate highbrow humor, one needs a habitus that not everyone has and that is connected with educational level. The appreciation of this highbrow humor calls for a certain distance comparable to the “aesthetic disposition” (Bourdieu 1984): the basic aesthetic attitude also necessary to appreciating modern and abstract art. Just like the highbrow humor habitus, this aesthetic disposition is related to cultural capital: a way of looking, reasoning, reflecting and communicating that people learn at home but that is acquired (or reinforced) to a large extent through education. This disposition is characterized by a distant way of viewing arts and culture: not the directly accessible pleasure of something that is at the first glance attractive, beautiful or pleasant, but a pleasure at a greater remove, derived from things you “acquire a taste for”. Literature, abstract art and contemporary classical music are not beautiful or pleasant on first acquaintance. Something similar applies to highbrow humor: at first sight it is not immediately funny, sometimes it can even be unpleasant. Ederveen at first sight is slow, de Jonge seems in the first instance mainly busy and chaotic, and Jiskefet, De Hunkering or Hans Teeuwen are sometimes distinctly disturbing.

In practice, this habitus is exclusive but it does not arise purely from snobbery. Laughing at Ederveen is, for people with this habitus and humor style, just as much a reflex reaction as the disinterest of the joke tellers. For the producers of this humor too, this appreciation is automatic. Highbrow comedians like Dorrestijn or Ederveen are not “being difficult” on purpose. They are so schooled in a certain idiom that it is no longer difficult for them. The lovers of highbrow humor have other ideas about good and bad humor; this is why they see in this humor something that others do not.

This also works vice versa: lovers of popular humor also see something that others do not see. The difference is that the others do not see nothing there, but something they reject: vulgarity, corniness, inanity, maybe they just think it’s boring. However, popular humor is not inaccessible in the same way: it can evoke rejection, boredom or annoyance, but never this disinterest, born of lack of understanding and almost impossible to put into words. As Egbert van Kaam (34, funfair worker), one of the joke tellers, aptly remarked: “André van Duin, now that’s someone everyone can listen to, one person thinks it’s corny, the next person is laughing till his stomach hurts, but it’s accessible to everyone” (for Kaam, incidentally, this was a good thing). Concerning André van Duin, then, everyone sees something about which they can have an opinion and about which they feel justified in having an opinion. But this is much less the case when it comes to highbrow comedians, the appreciation of whom often depends on a higher level of “inside knowledge”, that is strongly related to education. In this, we see the social advantage of cultural capital: it gives you more to appreciate, but also more to reject and more to look down upon.

Highbrow and lowbrow humor styles

What ensures that humor “does something” for people? What do people see in the humor that they find humorous? The questionnaire describes this but doesn’t provide an explanation. Thus, following the questionnaire, I talked extensively to 32 people who had filled the list in about what they think is funny, what they appreciate in their favorite humorists and what they saw when they watched humorous television programs. From this it became apparent that people have different criteria for good and bad humor.

Three of the four humor styles from the questionnaire were confirmed in the interviews: the popular style, the highbrow style and the veterans. The “mainstream” cluster with the celebrities was less visible. It appears this cluster reflects fame rather than a specific taste: renown leads to increased appreciation. There is also an element of social desirability here. Eleven interviewees had an above-average appreciation for and knowledge of the veterans, but this style always appeared in the interviews in combination with either a popular or a highbrow style. During the interviews people often turned out to have a preference for either the more intellectual humorists in this cluster (Wim Kan, Annie Schmidt), or the more popular, like Toon Hermans and Max Tailleur.

The majority of the interviewees matched either the highbrow of the popular style. Of the 32 interviewees in the sample, eight had a popular taste; twelve had a higher than average appreciation for and awareness of the highbrow humor style. There were hardly any “omnivores”19 who combined highbrow and popular styles. Only four combined these two tastes, but these four, all men, had distinctly broad taste: they liked all types of humor equally well, including the forms of humor that did not fit in any of the styles, such as American comedies and British TV series. Eight of the interviewees fell outside every style. I will deal later with these respondents and their tastes, preferences and objections. Before doing so, I will discuss the arguments of those who liked the highbrow and the popular styles. Why did they find humorists and television programs humorous?

Arguments for lowbrow humor

Eight of the interviewees from the sample (25%) fit the lowbrow cluster. These people were predominantly educated at primary or secondary level and they all had an above-average appreciation for the jokes. The majority of the joke tellers also had a lowbrow humor style: sorting their interviews retroactively, I grouped 25 of the 34 in this style. The remaining nine preferred the older humorists, particularly Toon Hermans and Tom Manders (Dorus). André van Duin was the favorite among the joke tellers, and Moppentoppers the favorite TV program - the latter not surprisingly, since I met most of them during the selection process for this show.

Lovers of lowbrow humor often formulated their preference for and aversion to humorists in terms of the person: Tineke Schouten “comes across really hilariously”; Freek de Jonge is a “strange man”; Ron Brandsteder “makes a pleasant impression”; Silvia Millecam is a “wonderful person”. The biggest compliment that was given here was usually for André van Duin: “You only have to see his face to start laughing”. This was also said of Silvia Millecam and Toon Hermans: “Just the way they look. You’ve just got to laugh” said 35-year-old army cook Patrick Kok. Only people with a popular humor style gave compliments equating person and humor. Objections against people whom they didn’t find funny were often directly aimed at the person: “Their faces just don’t appeal to me”. “Youp van ’t Hek just doesn’t come across agreeably.” “Spontaneity” was highly appreciated in humorists and television programs: most of the comedians in this cluster were spoken of highly for their “spontaneous humor”. This is also a characteristic of a person, not only of his humor.

If I’m watching André van Duin, then it’s just as if he’s making up what’s happening right on the spot, you know. He presents so all of a sudden as if it just occurred to him. I know for sure that that’s not the way it is. It’s rehearsed. But your feeling is: that comedian’s spontaneous. He’s not telling that in order to tell a joke but to make people happy.

(Jan Jurriaans, 73, retired director of sports organization)

“Spontaneity” thus means not only artlessness, that someone comes across naturally. It is mentioned here in one breath with “sociability” [gezelligheid].

The need for sociability is connected with anoter important consideration: that good humor is not hurtful. A funny joke, a good humorist and an amusing program may never “offend” or “insult”. One more compliment for André van Duin by Jurriaans: “The way he tells something and the jokes too, he’s never ever irritating. He doesn’t make jokes at someone else’s expense, you know.” Hurtful humorists and programs are disapproved of. Thus, Ivo Engelsman said of Wim Kan: “Doesn’t appeal to me because he quite regularly offends people in politics and, well, I don’t think that’s very sociable. I really love pleasant humor without anybody getting hurt. I think that’s nice.”

“Hurtful” [kwetsend] emerged during the interviews as a central but slippery concept: objected to by all, but defined in many different ways. This man objected to Wim Kan who used to offend politicians, while these politicians themselves often went to Kan’s shows, sitting in the front row laughing heartily at the jokes at their expense. On the other hand, Engelsman, like many others with a popular taste, liked ethnic and racist jokes as long as no one belonging to the targeted group was present. He didn’t like Paul de Leeuw because he publicly ridicules people, Freek de Jonge because he goes too far, but he enjoyed candid camera shows, especially “if they take the mickey out of someone who thinks he knows everything so well and thinks nothing can get to him, and then they’ve cut another one down to size, I really like that.” Being hurtful does not include all humor at the expense of other people. It is allowable as long as certain boundaries are respected. Engelsman formulated the golden rule here: it’s not allowed if the targets are present - except when they deserve it.

More important than what exactly counts as hurtful - that will be dealt with later - is the general statement Engelsman makes about humor: he wants “pleasant humor”. It has to remain sociable. Sociable, spontaneous, not hurtful, pleasant, “as soon as I see him I have to laugh” - here we have a description of a person as well as an atmosphere. The image of good humor that emerges from these descriptions is the sociable evening: good company, pleasant atmosphere, and nice people.

Other compliments have to do with the type of humor, apart from atmosphere or personal presentation. One big compliment was simplicity. Almost all lovers of lowbrow humor mentioned this: they liked “simple humor”, humor “that you don’t have to think about”, that is “just plain funny”. As Kees van Dokkum said of André van Duin, the most characteristic representative of the lowbrow humor style: “André van Duin is straight from the shoulder, you don’t really have to think about it, it is just plain pleasant”. A sitcom like Flodder shouldn’t be too difficult either: “It has to be really relaxed. If I want to go to the kitchen then I can just go to the kitchen. And when I get back, I haven’t missed anything [laughs]. It still just as funny” (Frouke Huizinga, 29, assistant teacher at primary school).

If people appreciate simplicity, “difficult” is naturally an objection. Intellectual humorists like a Freek de Jonge, but also Herman Finkers and Youp van ’t Hek are disliked for being too difficult, or because you “really have to pay attention”.

Freek de Jonge. I can’t follow him at all. It goes too fast and then I haven’t even heard half of it and then I don’t even go to the trouble to keep on following it anymore, because by then it’s not even interesting to me. If it starts costing too much to I think like: what’s all that he’s saying? Not that I really hate him or anything.

(Claire van Kampen, 37, assistant accountant)

I don’t like Freek de Jonge. I think that humor should be easy. He makes a joke and then a half-hour later he comes back to it and I can’t even keep track of that - at least I don’t feel like bothering. Then I’m sitting there in the theater and I should be just relaxing, boom direct humor, not having to think back a half-hour, like “oh yeah!” It’s not for me.

(Gerrit Helman, 26, logistics worker)

This reminds us of the lack of “antennae” described above: these people see it, don’t know what to do with it and give quickly.

Almost all people with the lowbrow style declared their love for impersonations; they found this “real humor”, “lovely humor”. Almost all the humor in this style is (partially) based on types: van Duin, Schouten, Millecam, van Vliet, Ook dat nog, and Flodder, they all include stereotyped characterizations, with accents, costumes, and standardized phrases. Jewish joke teller Max Tailleur did his best to turn himself into a type, complete with painstakingly emphasized external characteristics such as a heavy Amsterdam-Jewish accent, and, in the pictures on the covers of his joke books, a large nose with a moustache (similar to Groucho Marx’ trademark moustache and glasses). The other sitcom in this cluster, Oppassen! is somewhat less accentuated but does follow, as do all sitcoms, the pattern of character-driven humor: every personage is in essence a cliche. Types are often spoken highly of for representing craftsmanship and “professionality” - something said particularly of women. Frouke Huizinga said of Millecam: “Well, she plays a lot of different types, but very, very expertly. I think she’s extremely funny too. How she presents it.”

“How he/she presents it” was a much-used phrase in these interviews. As in the case of jokes (or at least, jokes that fit the “lowbrow” taste identified here), presentation often trumps content. This also explains the marked preference for types (and sketches): this is the most emphatic form of humorous performance. This love of performance also determines expectations people have of humor: message or meaning, and deeper or more extensive intentions are only mildly appreciated. People are not receptive to morals, which they tend to find irritating, pedantic or even crude. As Claudia van Leer said: “Well, a comedian doesn’t have to have a message as far as I’m concerned. They’re there are to amuse you, they don’t have to give you a message”.

Arguments for highbrow humor

Lovers of highbrow humor use different arguments to lovers of lowbrow humor. In the sample, these accounted for twelve (37.5%) persons who looked differently at humor to the lovers of lowbrow humor. They were less focused on craftsmanship, presentation or “how they present it”. Only once was a judgment about a humorist also a judgment about a person. Vincent Zwagerman, a 37-year-old man who quit university to become a carpenter, said of Paul Haenen:

He doesn’t make himself anything more than he is. He stays very close to himself. He simply adopts a weak position. And I think that is also the foundation of humor, that you adopt a vulnerable position. Once it starts to be always about someone else, then it becomes in a way less funny.

While this respondent also suggests that good humor should not be hurtful, the tone here is noticeably different from the previous quotes. The humorist is not regarded in the light of the “sociable atmosphere” but judged in terms of personal integrity and authenticty. The jargon used is almost that of therapy or social work, of “good talks” about relationships and not, as above, the language of the “relaxed” evening with “sociable” people.

The interviews with lovers of highbrow humor usually went more smoothly than those with the lovers of lowbrow humor. This is partly connected with educational level: the motivating and explaining of taste is an (essentially useless) skill mainly cultivated at colleges and universities. It can also be explained in terms of social interaction, since I could talk more easily even with the less highly educated respondents in this group. My own experience during interviews supports my thesis that a shared sense of humor is the best foundation for a good conversation.

Arguments for highbrow humor were often formulated in the idiom of art and literary criticism and High Culture. In these talks, the word “artist” appeared regularly and often people used an almost literary terminology. As Marijke van der Moer (34, high school teacher) said about author Gerard Reve:

He can formulate it stylistically in such a way that it is precisely that and not anything else. You can say something in a great number of ways and he makes a comparison at the right moment or uses a certain word combination, thus rendering the image with a fine precision. And that wins a laugh. A little while ago I read that thin booklet [by Reve], containing short stories or short essays. Well, I was doubled up laughing.

Striking here is the mix of literary idiom (“stylistic”, “image”) with the vocabulary of humor “doubled up”. Vincent Zwagerman called Paul Haenen an “artist in the area of communication”; Louis Balde thought Ederveen to be an “original artist”; Roos Schuurman praised de Jonge for the “layered quality” of his stories. It is “more than humor” (Louis Balde), “beautiful and funny” (Marijke van der Moer, Roos Schuurman). These people speak of humor in terms of style, aesthetic appeal and originality. In their eyes, aesthetics and humor must reinforce each other: “If it’s embedded in a whole story then the jokes stay with me longer. You can recall them. So you can keep on enjoying them after the fact” (Marijke van der Moer).

The most important criterion for good humor in this group is “sharpness”: humor has to cause a certain shock. This shock effect may not be “noncommittal” (Louis Balde, 50, high school teacher) or “superficial” (Bart Winia, 33, graphic designer). In the following quote, Corine Steen (40, marketing researcher) explains the difference between the right and the wrong sort of coarseness:

With Freek de Jonge at that time, then he went like “arrggg, along came the yellow car. And at that precise moment grandma decided to cross the street in her wheelchair.” Naturally, at that time there was no doubt about that being coarse humor too, but with that sort of thing [laughs] yeah, with that sort of thing I have a bit less of a problem. Yes, well, now why would that be less problematic? Of course, it’s super crude. But for some reason it has been made so much part of the story that you think, wow, how did he ever manage it, how did he manage to return to the thread of the conversation or to the theme with that bit of humor, and then it turns out to be humorous in spite of everything. Whereas, if someone just goes on spurting filth, then that’s not my sense of humor at all.

This example shows how shock effect is perceived as a style technique, used not only by de Jonge but also by other humorists in this cluster. Used in clever and “interesting” ways, this technique is central to the “highbrow” humor style. To illustrate the sort of shock effects common in Dutch cabaret, a quote from Hard and zielig [Hard and pathetic, 1994] the first show by Hans Teeuwen, a true master of this technique: “I went to the cinema recently and saw this beautiful film called Schindler’s List. Yes it was so beautiful! That was a very beautiful important film, cause, see, the people always talk about the Jews and all, while, er, these Germans weren’t cuties either.”

The framing in this technique is distinctly important, as is also apparent from the long quote above: just plain shocking is not good enough. “It has to be part of a story” (Louis Balde), it must have a certain function. As 27-year-old architect Maria Romein said of Teeuwen: “He can be extremely coarse, but he does manage exactly to hit a very sensitive spot”.

In contrast with the lovers of popular humor, lovers of the highbrow style want humor to be more than just amusement. However, the old-fashioned “socially critical” humor is not much appreciated and people abhor “moralism”. The humor has to “hold up a mirror”, but the humorist should not too emphatically announce his opinion. The meaning and intention must instead lie in bringing about this shock effect:

I still think that one of the best characteristics a cabaret artist must have is that he can sometimes hold up a mirror to his audience. We can all make jokes but if you do it as your profession, you should be willing to hurt a bit.

(Sybren Boonstra, 36, lawyer)

In this view, humor does not have to be sociable or pleasant. The humorists who belong to this style do not do their best to be liked; and the interviewees did not seem to find this question interesting. In highbrow humor, one is not concerned with simply pleasing one’s public. It has to “hurt a bit.”

The persons who appreciate this style often love absurdism, as is apparent from the presence of Jiskefet and Monty Python in this cluster. Roos Schuurman (30, high school teacher) made an attempt to explain the appeal of absurd humor:

Can you tell me why that absurdity appeals to you?

Yes, that is really difficult to say. Because there are also certain convoluted thoughts that are funny. What I really like about Monty Python is that an absolutely ordinary situation can get so carried away. And then you go and invert it. You don’t think that a realistic situation is being acted out but it goes a step further: it’s carried to such extreme lengths that you start thinking to yourself in certain realistic situations: what would happen if that were pushed to extreme lengths? And then it becomes funny. You get a sort of collision, people talking at cross-purposes and you often see that but then in a less extreme form. I don’t know exactly what it is, but I still find it really amusing.

However, like all humor, absurdism has to be “interesting” and “more than just funny”:

I feel like that with someone like Bert Visscher. That’s an absurdism that makes me think: yes [raspberry sound] search me. It’s too easy or too close. Too simple, but then I’m also saying that humor should be complicated sometimes. It’s just too easy. It’s too obvious. Just like André van Duin.

(Marijke van der Moer, 34, high school teacher)

Here van der Moer provides the last argument for highbrow humor: sometimes humor has to be complicated. This is a direct mirror image of the arguments for popular humor: there, “simple” was a compliment and “difficult” an objection. Van der Moer uses this as an argument against van Duin. It is the only argument that people were furtive about, because it implies the direct rejection of another type of humor and quickly leads to making a high-low division:

Take Freek de Jonge, for instance, well I tend to think that it’s usually reasonably well educated people who like him. With André van Duin, I guess I feel pretty sure that the people who like him are sort of not educated or only a little. I think that that could be said pretty clearly of a number of people, yes.

But do you also tend to make a high-low distinction in the humor?

[snickers]

Sounds a bit like it...

Yes, yes, naturally. Yes. One humor for the happy few and one, er, sort of humor for... Yes, that amounts to making a value judgment, doesn’t it? Let me say it like this: it is naturally awfully difficult to tell someone who’s completely crazy about André van Duin why you don’t like him. And vice versa: why is it now that I think Freek de Jonge is a really good artist? How would I ever be able to explain that to someone who doesn’t see anything in his act and who doesn’t get any further than “all he ever does is shock and it’s just this and it’s just that”. That’s pretty hard to do. And can you really go so far as to say: “Well, you’re too stupid to understand this?” Yes, sometimes I do think that, of course, but it’s not something you come right out and say to people very often, is it? But okay, it’s just a fact of life that some expressions of humor require a fair amount of mental elasticity on the part of the receiver while other forms of humor can be consumed if people are sagging dead tired in their chairs on Friday evening and feeling something like, now I want to be amused. So, okay, yes, I do finally think that it’s a bit like that.

(Louis Balde, 50, high school teacher)

Balde’s discomfort about making a distinction is obvious. It is no coincidence that Balde is more educated than his parents. The upwardly mobile are not only appreciably aware of their own elitism; the comparison with other sorts of humor is more strongly present in them.

What surprised me the most about the arguments for highbrow humor is that the interviewees, in spite of their marked skill in formulating their arguments and objections, rarely mentioned the most obvious characteristic of this humor, that which connects all humor in this cluster. Corine Steen, the marketing researcher quoted earlier, came the closest when she asked herself in the course of the interview with some surprise why she actually liked Jiskefet: “Yes, what can you say about that? Because naturally it’s right in between everything I’ve just been saying. It’s coarse. It’s simple. And still it’s enjoyable. Yes, I think it is the way it’s presented. And the tone, how they put everything into a context.”

What typifies all the humor in this group is the ambiguity of the humor. In highbrow humor, the boundary between humor and seriousness remains unclear; there is always a certain irony in it; there are sudden transitions to other emotions. That is clearest in Dertig Minuten, where no one knew anymore if it was real humor. But with the others too, the framing is unclear. You keep on asking yourself to what extent Gerard Reve is really serious in his exalted praise of Catholicism; whether the permanently depressed comic Dorrestijn is really so unhappy. Thus, you don’t always know why and about whom you are laughing: when watching Wim T. Schippers are you really laughing at farting and burping, or about a world in which people laugh at farting and burping? When Freek de Jonge tells jokes, are you then laughing at the jokes or at the fact that jokes are being told? Or were you not at all meant to think it was funny?

The contrast with the humor of van Duin, Flodder, Banana Split, sitcoms and joke tellers is clearest here. This humor is always emphatically framed as “funny”. Comics and shows in the popular humor style, like jokes, are unambiguously meant as humor. The presentation is either humor or something else: van Duin’s face changes at once if he starts singing serious songs. Should there be any doubt, there are always taped laughter, moustaches, wigs and accents to indicate that we are dealing with humor here.

The best summary of the arguments for highbrow humor is the following phrase that often returned in the interviews: “more than just humor”, “not just funny”. People expect of humor that it means more and appeals to more emotions than only amusement. The agreement with Bourdieu’s aesthetic disposition, that describes how people do not search for directly accessible pleasure in high art, but for “more than just the beautiful”, is striking. The humor in this style is often mixed with other emotions: positive, such as aesthetic appreciation or exhilaration, but often negative: shock, indignation, embarrassment, sadness, uneasiness or confusion. This can make the humor in this genre piercing or disquieting. Lovers of highbrow humor do not want just a sociable evening. They are looking not so much for an atmosphere as for an experience: an intellectual or emotional stimulant.

The eye of the beholder?

The statistics showed that different people find different things funny. The interviews show that behind these differences lies a different understanding of what humor is, and should be. People don’t just have differing ideas of what is funny, they have differing ideas about what is good and bad, amusing and irritating humor. This means that people, even if they laugh about the same things, are perhaps laughing for different reasons.

Sometimes different people find the same thing funny, but consider it from a different style, with a different logic. This happened for instance with Jiskefet, a television show produced by progressive-intellectual broadcaster VPRO that was very popular during my research. At the highest point of its renown, during Debiteuren Crediteuren [Debtors Creditors], a series of sketches in an office, many people watched the show who usually never watched VPRO. These people appreciated Jiskefet, however, for reasons typical of lovers of popular humor. One of the interviewed joke tellers appreciated it, for example, for “how they present it”: “It’s just the way they do it, I really think that’s fantastic. How they think it up. Every time another type” (Jasper Bentinck, 20, secondary vocational school student). Another joke teller appreciated the simplicity: “Yeah, in Debiteuren Crediteuren. Yeah, I really liked that. Oh yes, the stupider the better. That’s always the same. You sat there waiting till Miss Jannie [the depressed coffee lady in the office, GK] came in” (Joost Wiersema, 51, electrician).

Louis Balde, a high school teacher, on the other hand, approached it with highbrow logic: “Jiskefet, yes, I did watch it from time to time and then particularly Debiteuren Crediteuren. Still, I have to admit that after a time it became a bit limited. In the first instance, I thought it was a very original approach, a very original take on humor but at a certain point, after I’d seen it several times, the element of surprise was gone.”

Many people appreciated Debiteuren Crediteuren because in it they recognized their own office. Such “realist” readings of the sketches are also closer to popular than highbrow logic:

I only saw a little bit of Jiskefet when they’re in that office and then she comes along with the coffee, but that’s because, I think, because I work in an office too. That was Debiteuren Crediteuren. But I really, really liked that. But then you saw really ordinary things happening that made me think,

“Yeah, that sort of thing really does happen in an office”. So I think that that was the reason I liked it. Otherwise, I never actually saw anything of theirs.

(Claire van Kampen, 37, assistant accountant)

Finally, some respondents, like carpenter Vincent Zwagerman, offered entirely individual arguments whose style was difficult to capture:

Sometimes you sit watching and you’re thinking, gosh, could it be that you’re still sitting here watching? But when it’s over, that’s what I like about it, when it’s over it is extremely funny [laughs]. Once there was a skit [loud voice] “Peter! Peter! Peter!” [A series of absurdist sketches in which three men in overalls, all called Peter, walk around in woods and supermarkets, continuously calling “Peter”, GK]. And I still remember that I thought: now they’re going too far! That doesn’t make sense at all anymore! But meanwhile everybody is going around calling “Peter!” And then it happens again and I just double up laughing, [laughs]

The example of Debtors Creditors shows that the “humor divide” is not absolute. Some forms of humor are open to different “readings” (Fiske 1989; Hall 1980), and thus can be appreciated for both popular and highbrow reasons. However, only a small proportion of shows and comic are open to such diverse readings, as the tastes often lead to oppoosed judgements. Moreover, it is telling that the makers of Jiskefet were not particularly happy with the overnight mainstream success of their show. They rather self-consciously tried to lose their mainstream audiences by creating new sketches that were considerably less accessible, like the “Peter” skits. A broad popularity may well be a threat to one’s highbrow credentials.

Humor styles and taste variations

Not all humor is so easily connected with age and class. Some forms of comedy cannot be judged by the criteria of highbrow and popular humor styles, and not all humor falls within these styles. Two of the best known humorists of the Netherlands, de Leeuw and van ’t Hek, for instance, do not. Moreover, not all interviewees could be assigned to either the popular or the highbrow style. Persons who fall under a certain humor style do not always have the same judgment about a humorist. Everyone has specific idiosyncrasies, preferences and objections. Added to this is the fact that background variables other than educational level also play a role.

During the interviews, I encountered tastes linked with gender, with identification with a certain region (for instance, the comedian Herman Finkers is associated with Twente, in the east of the Netherlands, and Bert Visscher with the province of Groningen in the north), sexual orientation (gays who were fans of gay comics Paul Haenen, Paul de Leeuw, or André van Duin) or political standpoints (satirists like de Jonge or van Kooten and de Bie were appreciated more by progressive intellectuals). Additionally, I encountered highly personal preferences for the “disgust humor” (Oppliger and Zillman 1997; Saroglou and Anciaux 2004) in American animation films such as Rem & Stimpy, slapstick, nonsense humor, wordplay or the humor of children.

Several interviewees could not be fitted into particular styles. There were four “omnivores”, discussed above, who thought (almost) everything was funny and thus fitted into all styles. In addition, the sense of humor of eight interviewees did not fit into any of the styles. Of these eight people, seven were women. The eighth was a 38-year-old Surinamese doctor, Will Mungra, who thought Dutch humorists irritating and was, in any case, of the opinion that the Dutch have little humor. It is telling that people with an “outside status” like women or ethnic minority groups fall outside the standard styles. Their tastes are not represented very well in professional comedy.

Of these seven women, three appeared not to like any form of humor, whereas four had distinct, but uncategorizable tastes. It is tempting to search for the background of these individual tastes in gender. All four liked female comics like Brigitte Kaandorp and Adele Bloemendaal. Outside of that there were few similarities. One of them was close to the preference of many young people as far as taste went: she liked what she called the “hard, cynical humor” of van ’t Hek, Jiskefet and Over de roooie. The second had a style close to highbrow humor, but as a consequence of her age (84), did not know many of the humorists in this group.

Sofie Gooijer (37, homemaker with part-time adminstrative work) is interesting because she personifies a pattern present as an undercurrent in many of the women I interviewed. Her style is perhaps best described as a mixture of recognizability, absurdism and exaggeration. This can be seen readily in Absolutely Fabulous and Brigitte Kaandorp, identified as this woman’s favorite because of “those really silly things. The way she ridicules Libelle [women’s magazine] with the anemone wall hanging, that’s just great: nobody knows what you’re supposed to do with a thing like that but you get an anemone wall hanging. And later on she tells how she has a baby, it’s just really simple. That a baby like that has an entrance and an exit and it will become obvious all on its own what everything is for. Baby gets hungry, you start to react “pop!”; baby’s still screaming, you fasten it to you and soon everything’s quiet. I think that’s really marvelous.”

This is reminiscent of the “shared humorous fantasies” of Anke Vermeer (52, freelance writer) in the previous chapter. It is linked with homely sort of absurdism. Sofie Gooijer was one of the few who preferred the absurd sketches of Jiskefet to Debiteuren Crediteuren. Characteristic is what she remembers of the “Heeren van de Bruyne Ster” [Gentlemen of the Browne Starre, with a made-up spelling that suggests the 17th century], Jiskefet’s series of sketches on an Dutch East Indies Company Ship (the ship’s name is also a reference to homosexuality). With these sketches, they forfeited the audience they had built up with Debiteuren Crediteuren. However, Gooijer much preferred it to the willfully offensive realism of other sketches: “That the French were shooting at them with French bread. Now I think that’s wonderful.” Hers is an absurdism lacking hardness or shock effect - more nonsense than surrealism.

There were also three women, all three with low education, who did not fit the styles but who also did not have a recognizable individual style. These women thought very little was funny. They also made remarks about their own lack of humor: “Maybe I’m too stiff for that”, “I don’t think I find very much funny, I guess”. Sometimes this was quite painful:

Do you think you have the same sense of humor as your parents or one of your parents?

My father didn’t have any sense of humor at all. My mother did, she could really laugh. She would even be laughing while she was reading a book. And then there she was laughing and then she started to read it out loud to us. We had to laugh too. My mother had much more humor that I do.

And your other sisters?

Well, my younger sister laughs all the time. She really goes through life laughing, likes everything, finds everything funny, and then my other sister now and then says: “She’s got it so easy, she laughs about everything.” Yeah, not everything of course but as a way of speaking... Yeah, my mother was laughing all the time.

And your father?

No, my father was somber. I think I might have got that from him.

(Geertje Talma, 52, part-time nurse)

These interviews were awkward sometimes. The humorists and television programs that I asked about elicited hardly any reaction. These women were hardly interested in what appears on the television in the way of humor. Two of them could not name any acquaintances who had a good sense of humor (a question I asked everyone and that I will address in the next chapter). I suspect that these women had not only few humorous acquaintances but also few acquaintances altogether: they seemed to have a limited social network.

What the causal relationship with humor is here is difficult to say; it would seem peculiar to suggest that people start finding sitcoms more irritating because of a lack of social contacts. Perhaps there really are people who don’t find anything funny. Perhaps a lack of interest in humor quickly leads to social isolation. However, it seems more likely that the connection is the reverse: people who have few bonds with other people gradually lose their “antennae” for humor. In any case, these interviews showed me how intensely humor is connected with being embedded in a social network.

The connection with gender is intriguing. The cliche has it that women have less interest in humor; but these three women were exceptional. One factor that stands out here is the isolation of middle-aged home-makers. With their children grown up, these women were left with a small network and much time. I had the impression that this had affected their zest for life. During those interviews, I was struck by the connection between humor and social behavior, and between humor and zest for life. These three women, who saw little humor in their lives and in the world around them, seemed not only quite devoid of humor but the totality of their lives also seemed fairly cheerless to me.

In sharp contrast with this were the four omnivore respondents: all men, who thought everything was funny. They liked the humor belonging to all the styles: they liked both candid camera shows and intellectual fake documentaries like Thirty Minutes, they liked jokes and they also liked highbrow comic writers. Of course, sometimes there was something that they didn’t like (for some reason they all disliked Ron Brandsteder), but their taste was broad. The jargon they used was that of the “popular” humor; they were also less highly educated. These interviews actually went very smoothly. They were all jovial people, quick to laugh, and appeared to have a flourishing social network in addition to their jobs. One of them was constantly waving at all the passing neighbors during the interview; the other had his whole family living around the corner. Three of them also worked in traditional men’s worlds: the criminal investigation department, the army and the shipyard.

This is a mirror image of the women with a small network, no job, and little humor. These images may represent the extremes of a more general pattern, occurring among the working and lower middle classes, involving largely separate men’s and women’s worlds: women in the private domain, men in the public domain; men taking care of humor, women whispering jokes into their husband’s ear so that he can tell them. For the respondents above, this pattern is magnified: the men are social, funny, and appreciate all sorts of humor. The women inhabit an inside world quite separate from the men’s, with not much affinity for humor.

Cosers’ classical division of roles seems to apply here: men make jokes; women laugh at the jokes that men make. In this respect, it is interesting that one of the women said that her father never laughed and her mother always did. This suggests an explanation based in family dynamics. I will hazard a speculation here about the psychogenesis of humor. The development of a good sense of humor is also an individual psychological process, in which relationships within the family play an important role in addition to social relationships. The descriptions of the joke tellers have shown that humor in the family plays an important role in the development of a joke teller. There was often mention of mothers fond of laughing. The joke tellers often also mentioned joke telling grandfathers on their mother’s side. Here a pattern is visible through which mothers stimulate their sons to be funny; and fathers teach their daughters to laugh at their jokes.

Thus I have once more managed to sociologize the individual variations almost completely: that people didn’t like anything, liked everything, liked something intractable, all seems to be linked with gender. There is, however another important category that still has to be discussed: age.

Older and younger lovers of humor are divided on one issue: the funniness of boundary transgressions and shock effects. The young (approximately, respondents under forty) often have a preference for “hard jokes”, while those who are older object to the “coarsening” of humor. The preference for “hard” humor runs through all the styles and layers. We see it in the young woman architect who is a fan of Hans Teeuwen and the women with a degree in Dutch literature who likes transgressive comics Waardenberg and de Jong; in the joke teller who complained that his jokes about incest and people in wheelchairs were not accepted by Moppentoppers and who liked Eddie Murphy: “There’s a whole lot of cursing and swearing in it, but that’s a matter of choice. You know ahead of time that he’s got a foul mouth. The thing I really like the best is gross, dirty humor” (Jelmer de Moor, a 22 year-old gym instructor). Something similar was said by the joke teller who liked Waardenberg and de Jong, because: “It’s quite coarse. It happens instantly and is sometimes so coarse that I just have to laugh. They call a spade a fucking shovel. They don’t mess around, it’s just simply humor” (Gerrit Helman, 26, logistics worker).

“Hard humor” [harde humor] is usually a positive qualification for younger Dutch: a “hard joke” is a good joke. Older people often have difficulty with this. This has to do with differences in pain thresholds, but also with pursuing shock effects as a stylistic device, to which elderly respondents were less accustomed. Shock was not the primary aim of the generation of the “great three” Dutch humorists of the 1960s, Kan, Sonneveld and Hermans, no matter how diverse their humor may have been. Whether humorists of this generation only wanted to amuse or also to moralize, to satirize or to create something artistic, transgressing boundaries for humorous purposes was not the aim. Instead, they tried to to keep things civilized. This goes for everyone from this period, from political comedian Kan to lowbrow variety shows. This changed quickly after the late 1960s, when the country was shocked by a number of humor scandals involving jokes about religion, sex and nudity, and the Royal Family.

Most older Netherlanders grew up expecting “civilized humor”. Consequently, they see coarseness in a different light. My oldest informant, the 84-year-old lawyer Lotte van de Lans, who definitely did not seem easy to shock, was not so much indignant about the coarseness of Paul de Leeuw orvan’t Hek, as somewhat puzzled:

Van ’t Hek can be enjoyable too but I still think him too coarse now and then. Something like Paul de Leeuw. I have sometimes watched him and liked him. But the language they use. What does it add! But further away from the present day, you fall back on the oldies pretty quickly. Wim Sonneveld was a big favorite of mine. Wim Kan as well. But what’s on offer today: Freek de Jonge, his tempo is frequently so fast. I frequently can’t keep up with it. Maybe I’m too old for the mental leaps, too old I think to be able to follow it all so quickly. I do frequently think it’s too difficult or something like that, but he is certainly witty.

She points here as well to another stylistic difference between the generations from before and after 1970: the pace or tempo. In addition to becoming coarser, increased tempo is a noticeable development in Dutch cabaret during the last fifty years. In old recordings of Kan or Sonneveld, the pace at with the comedians speak and the number of jokes per given time period seems excruciatingly slow, the length of sketches and monologues extremely lenthy. This is connected with a more general (and possibly worldwide) development in the areas of media and the arts. Meanwhile a counter-movement has arisen too: highbrow comic artists like Ederveen and Jiskefet are sometimes exasperatingly slow.20

A lack of appreciation for shock effects is more troublesome for people like van der Lans, who otherwise has a highbrow style, than for people with a popular taste. Popular humor is generally more friendly and preferably not shocking, while the highbrow style is dominated by this shock effect. Young people with a popular style often like de Leeuw or van ’t Hek, who both have this hardness. Highbrow humor, through its emphasis on hardness and pointedness, is more inaccessible to elderly people. Civilized humor for the highly educated barely exists anymore in the Netherlands. Only few comics, like Martine Bijl or Hans Liberg come close: stylish, sophisticated, well-crafted, not aimed at shocking the audience and still not too easy. This seems to be an objective few humorists have.

With this we arrive at a question that, until now, has remained underexposed: what do more highly educated people like when they do not like highbrow humor? Figure 2 showed that both preference for and objection to this humor is connected with educational level. This means that there are highly educated people who are aware of highbrow humor but do not appreciate it. Bourdieu, in Distinction, distinguished “progressive” and “conservative” elite tastes, connected with cultural and economical capital, respectively. Highbrow humor has avant-garde features. According to the questionnaire, the highly educated respondents who love highbrow humor are, politically speaking, more left-wing and less religious than persons who are aware of this humor but do not appreciate it, and they often live in one of the four large cities (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Utrecht). They are, in other words, likely to have more cultural than economic capital.

Figure 2: Education and appreciation and knowledge of highbrow humor (PRINCALS-analysis).

CAPITAL font = preference for (choice 4 or 5 on a five-point scale); italic = dislike of (choice 1, 2 or 3 on a five-point scale); ordinary font = no knowledge of it.

LO, LBO, MBO, MO, HBO, WO: Dutch educational levels ranked from lowest (LO) to highest (WO) level. For explanation of educational levels, see Table 2.

Among the interviewees with a highbrow style, a distinction can also be made between the hyper-intellectuals, who saw van ’t Hek and even de Jonge as too “mainstream”; and a milder, less outspoken highbrow style. The litmus test for the distinction between the highbrow humor lovers and the somewhat looser highly educated group appears to be their opinion of the celebrity comic Youp van ’t Hek: in spite of his column in the Netherlands’ most prestigious newspaper NRC Handelsblad, highly cultured humor lovers think of him as somewhat coarse. Van ’t Hek marks the boundary between highbrow intellectuals and the more conservative highly educated group. He is thus also judged using changeable arguments: he is described as be both difficult and simple, both vulgar and deep. He was praised by interviewees for his “deep insight”, cursed for his high tempo, appreciated for his simplicity and held in contempt for his “so-called morality”.

What, then, do the more highly educated respondents who do not like avant-garde intellectual highbrow humor consider funny? The questionnaire shows that these people show a preference for non-popular humor that avoids shock effects: civilized humor. While they are on average not any older than the people who love highbrow humor, they appreciate the veterans more. In addition, they like English comedies like Keeping up appearances, Allo Allo or Mr Bean, and prefer Brigitte Kaandorp and Herman Finkers, humorists who fell outside all the clusters and whose humor is absurdist. As their favorite humorist, they name Youp van ’t Hek, Herman Finkers, and sometimes van Duin. Highly educated lovers of highbrow humor also sometimes mention van ’t Hek, but tend to prefer de Jonge, and seldom mentioned Finkers.

The clearest demarcation of the boundary between progressive and conservative highbrow humor is Herman Finkers. Of all the humorists, none escapes every classification to the extent he does. 15.9 percent of survey respondents mentioned him as their favorite comedian, second only to van ’t Hek (23.8%) and before Freek de Jonge (12.6%) and André van Duin (11.2%). Just as for van ’t Hek and Debiteuren Crediteuren, Finkers is someone who is appreciated for very diverse reasons. He is amusing for people with a popular humor style because his humor has no sharp edges, but also for people with a highbrow style on account of his curious, absurdist, convoluted thoughts. He manages to win over a lot of people with his accent and his references to his regional origin, but also with his linguistic jokes. Also, many people are taken by his determined non-urbanity. However, Finkers does not use shock effects, ambiguity, or any of the other characteristics typical of highbrow comics such as de Jonge. Absurd humor escapes the logic of both the highbrow and the popular humor style.

Conclusion: Humor styles beyond standardized Dutch humor?

This chapter describes Dutch humor styles, as they emerged from an analysis of people’s evaluations of standardized humor and professional humorists. The analysis of the survey results yielded a remarkably simple division in humor styles, related to class position and age. Although these styles do not capture all humor preferences, they represent a large proportion both of informants, and of the humor available in the Dutch public sphere of the late 1990s.

The strongest divide was between “popular” and “highbrow” humor. The popular humor style is most common among people of working and lower middle class background, and favors comedians and television programs that are exuberantly and emphatically funny. People who like this type of humor usually also like jokes. Lovers of highbrow humor are generally highly educated, and they like more ambiguous, ironical humor, that is sharp and sometimes unpleasant. These styles are generally mutually exclusive, in an asymmetric way: people who like popular humor are generally puzzled by highbrow comedy, whereas people who favor intellectual humor look down upon popular humor.

In addition, I found a strong age divide. Whereas younger people expressed a preference for “hard”, transgressive humorists, older people preferred more “civilized” humor. Older people generally disliked the mainstream comedy preferred by younger respondents, younger respondents often did not know the favorite comedians of older informants. Again, these tastes were mutually exclusive, and there was asymmetry in the judgment of others’ tastes.

The interview materials were used to trace the underlying taste patterns or “aesthetic logics”: the criteria for good humor, and objections against bad humor, that inform these humor styles. A distinct logic underpins each of these humor styles: it is expected of humor that it be sociable or confrontational, hard or civilized, artistic or relaxed, that the tempo be high or, on the contrary, conspiciously low, that the content be central or “how people present it”, that it be absurd or recognizable, exaggerated or non-committal, ambiguous or unequivocal, simple or complicated. These expectations and ideas determine not only what people see as good or bad humor, but also what people “see” in a joke or a joke maker.

In other words: these humor styles do not only determine appreciation or rejection of a particular instance of humor. They also provide the cultural knowledge and the “framework” needed to be able to recognize something as humor, and thus to evaluate and enjoy something as humorous, or not (cf. Kuipers 2009). To a certain extent, a humorist and their audience must share a humor style: they must (partly) share an understanding of “what good humor is” in order to make a joke work.