Chapter 9

National humor styles: Humor styles, joke telling and social background in the United States

In 2003, five years after I conducted my interviews in the Netherlands, I carried out a similar, though much smaller, study in the United States. This study involved a survey among 143 persons in the Philadelphia area, and twenty-eight in-depth interviews with Americans of various backgrounds about their sense of humor. This enabled me to compare Dutch patterns of humor styles and social background with American humor styles: do Americans have humor styles similar to the Dutch, or are there national differences in sense of humor? Are American humor styles connected with social background in ways similar to what I found in the Netherlands? The American study also functioned as a cross-cultural validation of the approach to humor I had developed in the Dutch study: do the approach and the concepts described in previous chapters still work in a different cultural context, where social distinctions and classifications may be markedly different?

Before embarking on the American study, I was aware that joke telling did not have the strong lower-class connotation in the United States that it has in the Netherlands. For instance, American academics (not just humor scholars) had regularly told me jokes - something Dutch, or European, academics would be highly unlikely to do. When, during presentations at international meetings, I said that jokes were not considered particularly intellectual and were, in fact, “not done” in academic circles, Europeans would usually nod, while Americans would be surprised, or misunderstand me, thinking I meant that highly educated Dutch people didn’t have much of a sense of humor.

This made me expect that jokes would not be the strong social marker they were in the Netherlands. The aim of this American study, therefore, was not only to compare opinions on joke telling, but, more generally, to detect social patterns in the use and appreciation of humor. Therefore, I broadened the scope of my research. I included cartoons as well as jokes in the questionnaire, and in both interviews and questionnaire focused more on television comedy and other forms of standardized humor.

Even though I expected humor to demarcate symbolic boundaries between social groups, I wasn’t completely sure which boundaries would be most prominent in the United States. Comparative sociological studies, such as those of Michele Lamont and her collaborators (1992, 2000; Lamont and Thévenot 2000) that compare the US and France, show that the dynamics of social distinctions differ significantly between countries.37 If the strong high-low distinctions had been something of a surprise in the Netherlands, in the US, I expected class differences to be even less marked (cf. Levine 1985; Holt 1997; Lamont 1992; 2000; Peterson 1997; Janssen et al. 2011). On the other hand, I expected ethnic differences to be more pronounced. I was not sure what roles age and gender would play in American humor styles.

It is not possible to discuss all the results of this American study in a single chapter. Therefore I start once more with the genre of the joke, asking three related questions. First: to what extent do patterns of appreciation of the joke in the United States resemble patterns of appreciation of this genre in the Netherlands? Second, I look at the social status of the joke in the United States: does it have the same gender-related and low-class connotations it has in the Netherlands? Finally, I explore how jokes relate to broader humor styles in the United States by looking at the way American interviewees define and describe “a good sense of humor”.

This comparison of opinions about joke telling and sense of humor almost automatically leads to more general differences in how Americans and the Dutch think about humor. Dutch opinions of humor revolve around notions of sociability and intellect while Americans see humor in a greater variety of ways. Most notably, Americans tend to talk of humor more in terms of morality and playfulness. This leads to different views about joke telling and humorous communication, and also to different processes of inclusion and distinction through humor.

Researching humor styles in America

The American study was smaller than the Dutch one, consisting of twenty-eight interviews and a survey involving 143 Americans in the Philadelphia area. The first twenty-four interviewees were selected to represent maximum spread in terms of age, gender, education, and humor appreciation. Four additional interviews with African-Americans were carried out because of the low response from minority groups.38

The American survey was designed in a similar way to the Dutch one, but adapted to the American situation. This implied more than just translating questions and jokes. Quite a few jokes could not be translated because they were based on wordplay or specific Dutch references, for instance to the royal family. Also, I included not only jokes but also a number of cartoons, in order to allow a wider variation in humor styles to emerge from the survey. In terms of content, however, I had to settle for less variation although the jokes in the American survey were more varied in form and genre. A number of the ethnic and sexual jokes I had previously used in the Dutch questionnaire could not be used in the American study due to restrictions imposed by the University of Pennsylvania’s Internal Review Board.

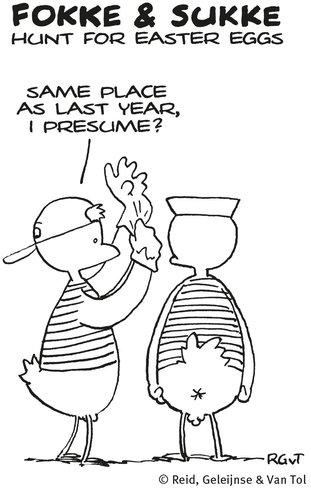

This means that the American study is not a replication of the Dutch study. Ten of the jokes in the questionnaire were translations or adaptations of jokes in the Dutch questionnaire.39 The rest were American jokes, cartoons from the New Yorker magazine, political cartoons from the International Herald Tribune and Dutch cartoons about a duck and canary called Fokke and Sukke (less offensive in Dutch than in English, but with sexual connotations in both languages). These cartoons appear daily in the Netherlands’ most prestigious newspaper NRC Handelsblad. They are very popular in the Netherlands (but, it turned out, less so in the US), and are typical of the Dutch highbrow humor style. Thus, this survey does not enable the strict cross-cultural comparison favored by psychologists. However, because of the adaptation to local repertoires, it does constitute a research instrument that is more sensitive to cultural specificities in humor styles.

It is also more difficult in the US than it is in the Netherlands to measure educational or class differences. The formal structure of American education is not as stratified as the Netherlands.40 In America, the main high-low distinction does not lie in whether one has a college or university education, but in which college one attended. While in the Netherlands most highly educated people will have (upper) middle-class jobs, in the US I interviewed to a bank teller and an emergency dispatcher - jobs I would describe as lower middle class - with college degrees. At the same time, upwards mobility during the career is more common. Educational level is therefore not the clear-cut predictor of job type or class position that it is in the Netherlands. Thus, in analyzing the interviews, I have focused on both on education and, whenever possible, on class position, distinguishing between upper middle class (professionals or higher, white-collar work), lower middle class (routine white-collar work), and working class (manual labor).

Jokes and humor styles in the United States: Survey results

The survey is once more the starting point for this exploration of American humor styles and joke telling. In contrast with the Dutch results, the American survey does not suggest as strongly that the joke is evaluated or appreciated as a genre. There is no relation between the overall liking for the jokes in the questionnaire and age, class, educational level, or income. Even the gender difference is marginal: women liked the jokes slightly less overall, but this difference is barely significant (p = .058).

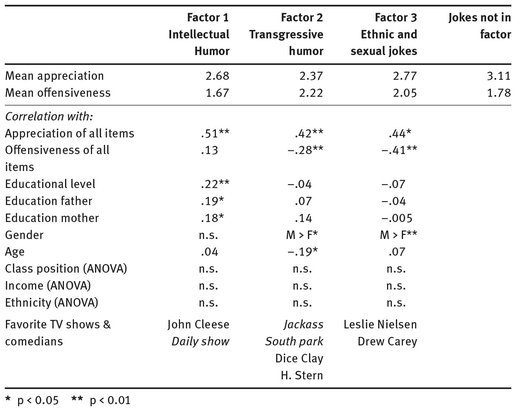

As in the Dutch research, I subjected the ratings of the 37 jokes and cartoons to a factor analysis. As Table 6 shows, this this resulted in a three-factor solution, showing a relationship between educational background, gender, and humor. Given my expectation that class would not be as important as in the Netherlands, it was something of a surprise that the simple measure of educational background used - the highest level of education completed41 - resulted in an analysis showing a relationship between humor and social background. Neither income nor class position was significantly related to any of the factors. Ethnicity was not significantly related either, but this is more likely the consequence of the sample. 92 percent of the respondents were white, which indicates an unfortunately very high non-response among other ethnicities. In contrast with the Netherlands, gender was more significant than age in the evaluation (or rejection) of offensive humor.

The first factor can best be described as “intellectual” humor. However, the nature of American intellectual humor is rather different from the Dutch version. It seems to be more a matter of content than form: this factor includes all the political jokes on the list. The most popular of these was:

A woman in a hot air balloon realizes she’s lost. She lowers altitude and spots a man below. She shouts to him, “Excuse me, can you help me? I promised a friend I would meet him an hour ago, but I don’t know where I am.” The man consults his portable GPS and replies, “You’re in a hot air balloon approximately 30 feet above a ground elevation of 2346 feet above sea level. You are at 31 degrees, 14.97 minutes north latitude and 100 degrees, 49.09 minutes west longitude.”

She rolls her eyes and says, “You must be a Republican.” “I am”, replies the man. “How did you know?” “Well”, answers the balloonist, “everything you told me is technically correct, but I have no idea what to make of your information, and I’m still lost. Frankly, you’ve not been much help to me.”

The man smiles and responds, “You must be a Democrat.” “I am”, replies the balloonist. “But, how did you know?” “Well”, says the man, “you don’t know where you are or where you’re going. You’ve risen to where you are due to a large quantity of hot air. You made a promise that you have no idea how to keep, and you expect ME to solve your problem. You’re in EXACTLY the same position you were in before we met, but somehow now, it’s MY fault.”

Table 7: Humor appreciation and social background in the United States Factor analysis of 37 items in survey, ratings on a scale from 1 to 542

I found this joke on the website of Rush Limbaugh, a controversial (though witty) right-wing radio host. It ranked sixth in overall appreciation and also loaded highly on the first factor. In the interviews, too, political humor came up time and again as the clearest, and most conscious, distinction between the sense of humor of more or less highly educated people.

This factor is characterized also by a liking for “clever” jokes, based on wordplay or complex references like the following:

What do you call an insomniac dyslexic agnostic? Someone who stays up all night wondering if there is a dog.

“Clever”, incidentally, was a word that many of the more highly educated interviewees used to describe good humor.

The second factor I have dubbed “transgressive” humor. This factor included several ethnic and sexual jokes such as two jokes included in the Dutch survey: the blonde with two brain cells and the racist driver. It also included a cartoon about the attacks on the World Trade Center on 9/11. The attacks had taken place about a year before the survey and this topic was still felt to be too serious to joke about. This cartoon was considered most offensive overall.

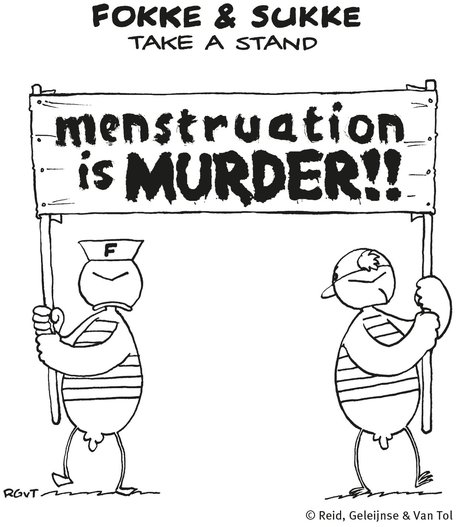

All but one of the Fokke and Sukke cartoons loaded highly on this factor. These cartoons, with their combination of shock effect and intellectual complexity, are typical of the Dutch highbrow humor style described in earlier chapters. Examples can be seen in Figure 3 and 4. American respondents generally considered these jokes offensive and not particularly funny. Figure 3 is especially interesting, because it could be read as referring to debates about abortion, a topic that carries very different associations in the US and the Netherlands. While in the Netherlands, it is relatively uncontroversial, in the US it is at the heart of some of the most heated and polarized public debates (Schalet 2011). Presumably, this cartoon is therefore more emotionally charged in the American context. While this may have raised its humorous appeal for some people, for the majority it probably reduced its funniness.

Only one of the Fokke and Sukke cartoons loaded on the intellectual factor in the US. This cartoon was relatively inoffensive and contained an explicit reference to intelligence: “Fokke and Sukke are card-carrying Mensa Members. Fokke: ‘Ordinary men think of sex every six seconds.’ Sukke: ‘We think of it once every three and a half.’”

All jokes and cartoons loading on the second factor were judged on average as being less humorous and more offensive than other items in the survey. Men and younger people liked these items better than women and older people. The scale was also correlated with a liking for American comics using shock effects, such as “shock jock” Howard Stern or the controversial comedian Andrew Dice Clay.

This factor represents the sort of humor that most Americans reject: explicit sexual humor, strong language, and violent ethnic jokes. Most interviewees denounced this as “bad humor”: offensive, demeaning, hurtful, lacking empathy, “gross”, and far removed from the American mainstream. It was often referred to as “adolescent”, something that seems to be corroborated by the correlation with age and gender. This factor highlights the distance between Dutch and American conceptions of good humor. Fokke and Sukke, a typical example of Dutch highbrow “hard humor”, were lumped together with the humor highly educated Dutch are most likely to reject: attitude jokes about racist murder.

Figure 3: Failed humor import; Average rating for funniness on a scale of 1 to 5: 1.94 (35th out of 37 items); Average rating for offensiveness 2.16 (eighth out of 37)

The third factor, which I have named “ethnic and sexual jokes” is also related to gender, but the items loading on this factor were much better liked. These were more mainstream ethnic and sexual jokes: the sort for which parents might admonish their children, but still jokes that could be aired on a late-night talk show, such as these:

A German, an American, and a Polack are travelling in the Amazon, and they get captured by some natives. The head of the tribe says to the German: “What do you want on your back before you’re whipped?” The German responds, “I’ll take oil!” So they put oil on his back, and a large Amazon whips him 10 times. When he’s finished, the German has these huge welts on his back, and he can hardly move.

The Amazons haul the German away, and say to the Polack, “What do you want on your back?” “I’ll take nothing!” says the Polack, and he stands there straight and takes his 10 lashes without a single flinch. “What do you want on your back?” the Amazons ask the American. He responds, “I’ll take the Polack!”

Another joke loading on the sexual and ethnic jokes factor was:

Guy takes his wife to the doctor...

The Doc says, “Well, it’s either Alzheimer’s disease or AIDS.”

“What do you mean”, the guy says, “you can’t tell the difference?”

“Yeah, the two look a lot alike in the early stages... Tell you what. Drive her way out into the country, kick her out of the car, and if she finds her way back, don’t have sex with her.”

As Table 6 shows, appreciation of jokes loading on this factor is related to gender. Age is not related to the appreciation of this mainstream form of transgression, meaning that the relationship between age and offensiveness, so clear in the Netherlands, was not very apparent in the US. Instead, American women seem to have a lower threshold for offensiveness than men, a distinction less clear in the Netherlands.

The third factor has to do with morality and offensiveness. Even though patterns of joke appreciation were linked with morality in the Netherlands, this theme was much more prominent in American interviews. The American discourse on humor is suffused with morality: I could easily get my interviewees to talk at length about the humor they would allow their children to watch, the humor they refused to watch themselves, and the humor that ought not to be allowed in public at all. As in the Netherlands, many interviewees expressed the belief that women were, on the whole, more sensitive to offensive humor than men. In the US, this was corroborated by both the interview and the survey results. Women generally expressed more concern about, and less appreciation of, ethnic and sexual jokes as well as profane language in jokes.

Finally, some items in the American survey did not load on any of the factors. These were jokes that were most liked overall. They were narrative jokes clearly following the conventions of the joke genre, and they were rather long. I will return to these long and successful jokes later in this chapter.

The logic underlying this factor analysis differs from the logic underlying Dutch patterns of humor appreciation. The first two factors both combine items that would be on opposite extremes of a scale in the Netherlands. Factor one includes jokes and clever political cartoons; factor two lumps together offensive jokes and intellectual cartoons using shock effects. Compared to the Dutch highbrow-lowbrow and old-young pattern, the American pattern seems more complicated: it shows three factors, and a number of jokes falling outside these.

It is not likely that this more complex pattern merely results from including a wider variety of humor in the questionnaire than jokes alone. For one thing, there is no indication that American respondents evaluate the joke as a genre. Social distinctions cut through genre boundaries, combining political cartoons and jokes, but separating jokes of various degrees of hurtfulness. Among American respondents, differences in humor appreciation are related to content rather than form or genre. These results not only contradict Dutch findings but also pose a cross-cultural challenge to the psychological studies by Ruch and Hehl (1998), who concluded that in humor appreciation, form was more important than content.

Based on the survey, we may conclude that humorous distinction in American seems more a matter of content than of form. Therefore, the strict separation of appreciation of the genre and individual jokes, which worked well in the Dutch study, seems less valid for the American situation. Therefore, I now first turn to patterns and mechanisms in the appreciation of individual jokes before moving on to broader humor styles.

Transgression and identification in American jokes

Looking exclusively at the jokes that both American and Dutch informants were asked to rank, the agreement on likes and dislikes is quite striking (see note 39). The highest ranking jokes in the Netherlands were also among the American favorites: the priest in the flood, the stupid soccer players (“It’s not your brother but your father’s son”), adapted to an American setting, the vacuum salesman, and the more risque jokes about Johnny and his teacher, and the Bible salesman. The average ratings of these jokes were similar in both countries, too. These very popular jokes happen to be the jokes that did not load on any of the three factors in Table 6.

The most popular items were all long jokes with a strong narrative structure. They were judged to be moderately offensive, ranking somewhere in the middle in terms of offensiveness. The Dutch finding of the effect of the number of words in a joke was replicated: correlation between the average appreciation of a joke and the number of words was even higher than in the Netherlands: .669 (p < .01), against .55 in the Netherlands. Thus, criteria for good joke form seem to be similar in the two countries. Indeed, this supports the conclusion of Chapter 7, that the joke genre has inherent standards for good quality, based mostly on joke form, which are not only similar across social groups, but also across nations.

Although the most offensive jokes could not be included in the American survey, Americans and Dutch also agreed which jokes they liked least. The joke about the racist driver, who in the American version runs over blacks instead of Turks, was ranked most offensive. The Turkish woman who was spat at became an Italian (this was an existing American joke), and ranked second highest in offensiveness. Both these jokes ranked low in humorousness: the racist driver ranked eighth lowest, the Italian woman eleventh. However, this was not as low as most of the Fokke and Sukke cartoons, and three of the political cartoons dealing with sensitive topics: the war in Iraq and the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

The overall relation between funniness and offensiveness of jokes was less strongly negative in the US than in the Netherlands: -.29 (against -.44 in the Netherlands). In contrast with the Dutch findings, relations between appreciation and offensiveness for each individual joke and cartoon tended to be stronger. Thus: if Americans found a joke offensive, this was much more likely to negatively affect their appreciation. In this respect, Americans are most similar to the older respondents in the Dutch survey. Or perhaps, they are most dissimilar from the younger Dutch, for whom, as we saw in Chapter 7, offensiveness and joke quality are virtually unrelated.

American respondents liked some of the items quite a lot even when though they found them quite offensive. This was the case, for instance, for the joke about Johnny and his teacher. There were also many jokes are cartoons they did not like even though they were inoffensive. Items judged both inoffensive and funny were most notably the “intellectual” cartoons, such as the less offensive political cartoons and the New Yorker cartoons.

One of these unfunny, inoffensive cartoons was based on a reference to the beginning of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. It showed a publisher saying to a bearded man: “I wish you would make up your mind, Mr. Dickens. Was it the best of times or was it the worst of times? It could scarcely have been both.” The attraction of this cartoon is definitely not its transgressiveness. Like most American-style intellectual humor, its funniness is based on clever findings and witty references rather than boundary transgression or shock effects. However, this joke draws a clear symbolic boundary, excluding those who are not familiar with the first lines of a 150-year old book.

The correlation between humorousness and offensiveness for solely verbal jokes was -.47 (p < .05), markedly higher than for jokes and cartoons together. Thus, the difference between overall correlation in the Dutch and American studies is mainly due to the presence of other genres, which rely less on boundary transgression for their effect than jokes do.

Within the genre of the joke, the dynamics of joke work and transgression seem quite similar in the Netherlands and the United States. All people prefer long jokes, with moderate transgressiveness and a clear build-up. Differences in joke appreciation, as in the Netherlands, are easily traced back to differences in sensitivities. Even the themes that work best are similar in the two studies: religious jokes, stupidity jokes (especially if they are not ethnic but about blondes or politicians) and mildly sexual jokes. However, the findings indicate that different genres, such as cartoons, may have different dynamics.

While the dynamics of appreciation are similar, the relation between appreciation and social background in the United States differs from the Dutch pattern. As Table 6 shows, age differences were less pronounced than gender differences. While gender affected the appreciation of the genre as a whole in the Netherlands, American women objected to specific types of jokes: they found both ethnic and sexual humor significantly more offensive than men, and tended to rate jokes and cartoons about these themes significantly lower.

American humorous identifications

Identification may mediate, enforce or mitigate the appreciation of jokes. I will not explore this extensively here, since the mechanisms and dynamics mostly corroborate the Dutch results. Also, I did not analyze the full American joke repertoire, nor did I interview joke tellers, which makes it harder to explore how the joke culture would provide identification opportunities for various groups.43

Generally the strongest identification affecting humor appreciation in the United States is gender, as it was in the Netherlands. The American joke repertoire is as masculine as the Dutch one, and many female interviewees commented on how jokes demeaned women. It is likely that the male perspective in jokes negatively affected women’s liking for jokes and cartoons, and especially for sexual humor.44

Three group identifications affect humor appreciation in the US much more than in the Netherlands: politics, ethnicity, and religion. The effect of political affiliation on humor is clearest in the appreciation of political humor. The joke cited above about the woman in the hot air balloon was liked significantly less by Democrats than by Republicans (p < .01). In America, politics, which hardly had any effect in the Dutch study, affected not only the appreciation of political cartoons, but also of ethnic humor, which Democrats found more offensive and less humorous.

Religion was another clearly-pronounced group identification. The effect of religion was much stronger in the United States than in the more secularized Netherlands. The religious jokes, on average, were liked very much: the priest in the flood (“God will save me”) was liked best overall. The joke about the stammering Bible salesman, and another that contained a reference to Jesus’ resurrection were highly appreciated. Christians liked these jokes significantly more than non-Christians. This effect was clearest for the joke about the Bible salesman, which Protestants liked better than non-believers, and Catholics liked even better than Protestants (p < .05). However, Christian background generally negatively affected the enjoyment of sexual humor, which Christians, as a rule, found more offensive. Jewish respondents were not opposed to sexual humor, instead objecting more to ethnic humor.

Ethnicity was a final identification that strongly influenced humor appreciation. Sadly, this cannot be analyzed properly using the survey results: there was not enough variety in ethnic background in the sample, due to the high non-response among non-Caucausians. Respondents from ethnic minorities tended to dislike ethnic jokes, but because of the low percentage of non-white respondents, this was hardly ever significant. Interestingly, white respondents rarely knew comedians or TV shows featuring people with different ethnicities. I included African-American and Latino comedies and comedians in the questionnaire, but white respondents generally only knew the very famous comedians Bill Cosby and Chris Rock. Most interviewees also mentioned spontaneously that they were not interested in “black comedy”, which is clearly identified as a separate domain (cf. Coleman 2000; Watkins 1994).

African-Americans interviewees were oriented towards black comedy. They showed the typical pattern of a dominant taste group: they were well aware of mainstream comedy, even though they did not like it. White respondents, on the other hand, were only vaguely and imprecisely, though dismissively, aware of the humor of African-American or Latino minorities. In this respect, American white respondents were remarkably similar to the highly educated Dutch, who also dismissed popular humor without knowing much about it (Kuipers 2006a). While Americans were not very willing or likely to reject lowbrow tastes explicitly, they were quite comfortable stating their disinterest in the humor of ethnic groups other than their own. The exception was, perhaps unsurprisingly, Jewish humor, which was often praised by people of various religious and ethnic backgrounds.

My interviews, as well as more general observation of American culture and comedy, made clear to me how important a role humor plays in processes of ethnic distinction in America. Blacks, Latinos, and Jews are all very self-conscious about having their own brand of humor, which outsiders may not always understand. These humorous self-images are often shared outside these groups: there are popular stereotypes of witty Jews, and exuberant, though rather explicit, African-American humor. Other ethnic distinctions also have connotations of specific humor styles: an informant of Italian descent explained to me at length how his humor differed from his wife’s, whose roots were Irish.

However, in these processes of highly self-conscious boundary marking through humor, it is sometimes hard to separate identity politics from “actual” differences. Despite the adamant belief held by many of the Dutch interviewees in regional differences in humor, I could not identify differences in my data, no matter how hard I tried. In a similar vein, processes of ethnic distinction in the US may not always be related to clearly identifiable differences in humor style.

It is hard to tell how ethnic identifications play out in liking jokes, or in broader humor styles, using the data collected for this study. Jewish informants often had a joke repertoire different from other respondents’, and strongly identified with Jewish humor and Jewish comedians. Even based on a few interviews, it is clear that African-American interviewees generally have a style of humor and communication rather unlike most white respondents.45 Both groups have their own comic tradition, and African-American humor even has its own specialized outlet on the black-oriented television network, BET. Such institutionalization of ethnic humorous forms and tradition probably stimulates cultural differentiation and distinction in the domain of humor. A more extensive study may be needed to understand processes of ethnic “humorous distinction” and humorous “boundary work” in American humor. However, even without further analysis, this underlines the central characteristic of the American “humor landscape”: it is considerably more differentiated and fragmented than that in the Netherlands.

The social status of the joke in America

The survey results did not indicate a general liking or dislike of the joke genre. The interviews gave me more opportunity to gauge people’s opinions on jokes and joke telling, and, more generally, on how this genre lived up to the interviewees’ standards for good humor.

More highly educated American interviewees generally did not dismiss jokes as radically as their Dutch counterparts did. Even though they usually professed to like humor that was “clever”, “intelligent” or “meaningful”, they did not link it to form or genre as strictly as my Dutch informants. Thus, a 54-year-old lawyer (Note: if ethnicity is not specified, the interviewee is white) described his sense of humor as “intellectual”. But he also described his friend with a very good sense of humor as someone with an “excellent memory for jokes”, which would amount to a complete disqualification for most Dutch lawyers. He also said he actively told jokes:

I’m not great at jokes so I have to I have to try them out on people and I don’t remember many of them. But you know it’s a useful tool to break the ice with a crowd of strangers, when you’re worried about getting their attention, so you get them to kind of lighten up. Are you a good joke teller?

Not particularly. Only if I’ve told a joke many, many, many times and really rehearsed it. There’s one I’ll tell when we go off tape [he never did, GK].

A college-educated, 56-year-old graphic designer professed a liking for “topical, intelligent humor”, with a preference for political humor. But when asked to describe someone with a good sense of humor, she chose her ex-husband, whom she “admired for his sense of humor”:

He can tell jokes very well. He could not only remember the punch line, which I never could, I can’t even remember the jokes now and won’t even attempt to try to tell them. But he could remember them and tell them and entertain people by telling them. He’s a good speaker and I love that, his timing was fantastic.

In general, highly educated interviewees identified joke telling as part of a sense of humor, one of the things that someone with a good sense of humor was likely to do:

Do you think joke tellers are usually people with a good sense of humor?

Not necessarily. But some are. I think a person with a good sense of humor is more likely to tell a joke well than a person who hasn’t.

(Retired professor of engineering and mathematics, M, 74)

Less educated interviewees were more likely to be true joke enthusiasts. For instance, a 63-year-old building contractor reminded me very much of the Dutch joke tellers. He told me many jokes during the interview, and his speech style and bearing, as well as the constant references to masculinity and gender, made him very similar to Dutch joke lovers. Male respondents with lower middle-class or working-class jobs (e.g. a database programmer, a police officer, a theatre technician, and a casino worker) usually told me at least one or two jokes during their interviews.

Some educated interviewees were more critical of jokes. One remark reminiscent of the Dutch highbrow attitude came from a 46-year-old female bank employee, who was educated at one of the elite colleges in the Philadelphia area. She seemed mainly embarrassed by jokes:

A couple of my friends are joke tellers. But, I always feel very nervous before they – I sometimes feel nervous when they start to joke because I’m afraid I’m not gonna think it’s funny and then they’ll just be there and I really can’t fake the laugh, but I guess if I’ve been drinking, it’s ok because as soon as they start telling me the joke, I’ll start laughing because I just know it’s gonna be good. And I’m usually just laughing so hard before he even gets to the punch line [laughs] and he’s telling me to shut up, you know. But I do feel a little bit of anxiety because, you know, what if it isn’t funny? But it’s great when it is funny. And I’m really not a joke teller myself. I can’t remember them...

This interviewee does, however, say that she has friends who tell jokes, whereas the highly educated Dutch respondents usually said they hardly ever heard jokes in their milieu.

Like in the Netherlands, upper middle-class Americans were more likely to speak of good humor in terms of wit and intellect, whereas those with lower-level jobs would evaluate humor in terms of sociability. However, such differences rarely led them to renounce other people’s sense of humor. The few times this happened, it was a lowbrow dismissal of highbrow humor rather than the reverse. In none of the interviews did class differences in humor style lead to outright dismissal of a genre or social category.

These tendencies to stress intellect versus sociability may be the effect of the working conditions of more and less educated people. Upper middle-class people have not only spent much time in educational institutions devoted to training the intellect, but their jobs also often consist of more intellectual (and more individualized) work. Routine white-collar and working-class jobs involve more team work, more standardization, and more gender separation (cf. Bourdieu 1984; Collins 1992; Erickson 1996; Willis 1977).

Such structural conditions are likely to translate into similar class cultures across different countries. However, such differences in class culture were less marked among Americans. From a Dutch perspective, at least, American (upper) middle-class informants did not behave in as consistently a “highbrow” manner as their Dutch counterparts. They could be very vocal about their enjoyment of popular forms of humor, such as jokes or sitcoms. Moreover, differences that did exist generally were not articulated explicitly as markers of class differences. In other words, humor was less often used to demarcate symbolically or highlight class boundaries.

In the United States as in the Netherlands, joke telling definitely functions as a marker of gender distinctions, both explicitly and implicitly. Both educated women cited above state, in passing, that they cannot tell jokes. Most women I spoke to said something similar: “I can’t remember them”; “I often start with the punch line”. These were exactly the same phrases their Dutch counterparts used. American women also would excuse themselves from telling jokes in a more typically American idiom: “I can’t tell a joke to save my life”. Most of the men I interviewed repeated the notion that joke telling was more of a “man thing”. Two older men, the contractor cited above and a retired police officer, felt it wasn’t “appropriate” for women to tell jokes.

However, unlike many Dutch women, the majority of American women I spoke to did not say they disliked jokes. I even interviewed one woman who, like her Dutch counterparts, had her husband tell her jokes for her: “If I hear a really really good one I’ll tell my husband, and maybe tell him to relay it to someone else. But for me to tell it to anyone, that might have happened twice in my lifetime” (Nurse, F, 32, African-American).

Although jokes are not similarly low in status, gender patterns in the use and evaluation of the genre are remarkably similar on both sides of the Atlantic: women may like jokes, but as spectators rather than performers. However, few of the interviewees spontaneously expressed particularly strong opinions about the genre as a whole. It was not as easy for me to provoke the rejections of the entire genre I had heard in the Netherlands (“spiritual poverty”, “jokes - those aren’t humor”), even from female interviewees. Clearly, in the United States, the joke does not conjure up the same connotations of boisterous men, working-class bars, and loud fun, an atmosphere excluding - or abhorring - both women and members of the upper middle classes.

American arguments against the joke

To understand this national difference in the status of the joke, I explore how Americans perceive the genre by comparing Dutch views on the joke: to what extent are these shared by the Americans? Or do Americans use other arguments against the joke?

Chapter 3 dealt with Dutch arguments against the joke, which can be summarized into the following, slightly overlapping, objections. First, jokes are too impersonal. This point was made mainly by women. Second, a joke teller is inauthentic because he is “merely passing something on”. A third objection was the “attention seeking” and dominance implicit in joke telling. Fourth, joke telling is too explicitly funny, too clearly framed as humorous. This explicit framing also makes joke telling too loud, too exuberant; it shows a lack of restraint and control.

Several American interviews objected to the impersonal character of jokes; most of these were highly educated women. A 43-year-old male biochemist came closest to the Dutch highbrow style in explicitly describing his humor as:

Like, kind of more, not jokes. Not somebody who’s going to go up there and just say, you know, a guy walked into a bar kind of a joke, just more somebody who can tell a story and, kind of be creative and make it funny.

This is a clear echo of the educated Dutch joke hater: he prefers creative story-telling to jokes. However, no other interviewee explicitly rejected the joke because it lacked creativity.

Women, especially, objected to the inauthentic nature of joke telling and framed this in terms of lack of personal involvement. This could be seen when I asked the nurse who relayed jokes to her husband:

Do you think telling jokes is a sign of a good sense of humor?

No, it is a sign of a lot of time on your hands [laugh]. I don’t know – I don’t think the funniest people I know are joke tellers, I think that they are more just naturally, you know, funny. They can find fun, you know, something humorous, in the environment or just anywhere.

A 53-year-old woman working in a food co-op described her friend with a good sense of humor:

She has a real good sense of the absurd. She can kind of hone in on like, the major personality characteristics of a person and exaggerate them a little bit to make a wonderful story or instructive story. Which also means that if she’s aggravated, it can be kind of edgy and meanspirited. And she has a wonderful sense of exaggeration... For example, she has a dog. And she’s pretty, she’s not ridiculous about this dog. And, then, sometimes she’ll talk about the dog, like, that the dog’s misbehaving and she’s thinking of sending her to a boarding school in Connecticut. And then, you’ll look at the dog and the dog’s got like, staring off into space and she’ll say, “Well, she’s thinking about what to pack for boarding school” or, you know. Just kind of silly, exaggerated stuff like that. [silence] It’s not a joke telling...

So, you don’t like the joke telling sense of humor?

[silence] I like, I like jokes. But that’s probably not my favorite sense of humor. I find it a little off-putting in terms of relating to people, you know, if what they want to do is tell me jokes. I like more contextual humor. So I don’t think I have any friends who mostly tell jokes as a way of having a sense of humor.

This is a typical example of the “shared humorous fantasies” (see Chapter 3) found among many female Dutch respondents. Many of the American women I interviewed, of various ethnicities and class backgrounds, described this form of humorous storytelling. Clearly, this focus on personal and contextual humor does not combine well with joke telling, which is neither personal nor very contextual.

Objections against the impersonal nature of the joke were by far the most prominent. One other argument that came up, mostly in interviews with women, was the attention seeking and dominance implied in joke telling. The latter argument can be discerned in the bank employee’s comments cited above: “I sometimes feel nervous when they start to joke.” Another woman told me, when I asked her whether she liked jokes:

It’s ok, I mean some people really have a talent for it and they can do it, they can tell a joke with the best of them and you will sit and laugh at it even if you’ve heard it 20 times before. But other ones it is, oh, they just don’t quite get the same spin on it so it is not clever when they do it. They just sort of hit you over the head with it, and if it is not funny, they just sort of pound you with it somehow.

(Retired emergency dispatcher, F, 75)

This woman, too, stressed how the conversational event or “interaction ritual” of telling a joke would make her feel uncomfortable.

A final objection, prominent in the Netherlands and shared by some Americans, was the way joke telling tends to affect the atmosphere:

Working in a restaurant or a bar, youd actually hear quite a lot of jokes like that?

I would probably just walk away from them, even when they try and tell jokes or whatever. There’s a few people that just have to get on with the jokes you know. Plus if you tell jokes then you always get a joke in response, you know. And then it just becomes one-upman kind of thing so I kind of, try and I try to avoid that and whatever.

(Hotel owner, M, 43)

However, neither the explicit humorous framing nor the loudness and exuberance of telling jokes was mentioned as a problem in American interviews. In general, Americans communicate more explicitly than the Dutch. In everyday life, as in standardized humor, ironical, deadpan presentation is not as highly valued in the US as it is in the Netherlands (and other European countries). Americans tend to be more outspoken both in their attempts to be humorous and in their appreciation of such attempts; they will often verbally acknowledge a joke, saying “That’s so funny”. Even when Americans are ironic or (more frequently) sarcastic, both forms of humor for which the framing may be rather vague, often the delivery is be quite explicit.46 Possibly, this is related to the greater social diversity in the US and its history as an immigrant society. In a more homogeneous nation-state, communication can be more implicit, and humor can be signaled in more subtle (and exclusive) ways (cf. Hall 1969).

Dislike of loudness and exuberance is a strong marker of class difference in the Netherlands. Traditionally, restraint and self-control are at the center of class distinction (Elias 2012; Wouters 2004, 2007). Controlled body language and speech styles were among the main differences between joke tellers and Dutch interviewees with a highbrow style. In contrast, American educated interviewees did not seem very concerned with this sort of cultivated self-restraint (cf. Schalet 2011). In the United States, cultural refinement is much less a marker of status. Even upper middle-class professionals tend towards informality (Collins 2004: 258-296; Kalberg 2000) and “cultural laissez-faire” (Lamont 1992: 100-110).

Most American respondents seemed to feel that “letting go” was one of the good things about humor, rather than a risky enterprise leading to potential status loss. Respondents of all social backgrounds linked humor with positive notions of release and the removal of self-restraint. They would comment how good humor not only provokes smiles and laughter but “belly laughs”. Tellingly, in American English “hysterical” is a positive qualification in the context of humor, as is “crazy”. The exuberance and physicality, which, as discussed in Chapter 2, has been one of the main European objections to humor and laughter since early modernity, has gained a positive connotation in the late Modern American context. As Lewis (2006) illustrated, this release function of humor is even hailed by many Americans as contributing to medical and physical health.

American views on the joke genre differ from Dutch views in two other important ways. First, objections to joke telling were, more so than in the Netherlands, directly connected with interpersonal relations. For instance, the woman cited above felt that jokes are “off-putting in terms of relating to people”. Another interviewee explained:

My oldest brother always has a joke and personality-wise we are very different. I kind of think I’m offended by a lot of his jokes.

Offended in what way?

I don’t know – I guess I’ll find them racist or sexist or I guess they are dirty jokes. It is funny cause I don’t think, if I read something I am not offended by it, again, it is like if you have a personal relationship with someone and I will think in some subliminal way he is, like, my oldest brother, he is not supposed to be telling me these, you know, jokes... He is a joke teller but he is not the joke teller of the family. I think he just knows how to get behind people’s defences and make them, you know, disarm. He is a really really good salesman like he has broken records and won awards and makes a lot of money and everything and I think he is just very talented at making people disarm and getting them to trust him. And I think it is more in that than in like, I mean he does tell good jokes but I don’t think of him as like a jokester.

(Marketing consultant, F, 39, Latina)

Note how joke telling is connected here with sales, as in the Netherlands. For this woman, however, her brother’s use of humor in sales is almost a form of manipulation, a lack of authenticity in dealing with other people.

The second and main difference, however, was that Americans often addressed the content of jokes in the course of denouncing them. Chapter 3 shows that Dutch people who disliked jokes never objected to subject matter; rather, they objected to jokes in terms of communication style. Only people who liked jokes referred to content, in order to distinguish within the genre. In the American interviews, comments about communication styles were interspersed with comments about vulgar language, offensivenesss, or jokes demeaning to women:

Do you like jokes?

I try to keep an open mind, and people say well it is just a joke, don’t take it seriously, so I take that into account. But in general I don’t like racist, sexist, um, where the insult is demeaning a group of people [... ] You had [in the survey] some jokes that bordered on violence, I don’t like anything with like children being demeaned, or anything violent, pornographic. Free society, but I don’t want to hear it.

(Freelance writer, F, 42)

The comparison between the Dutch and American objections to jokes suggests a divergence between the two countries. The more intellectual or elite arguments against the genre, such as limited creativity in joke telling, lack of restraint, and emphatic humorousness, were mainly absent in American interviews. On the other hand, objections having to do with interpersonal relations and personal authenticity - that is, the more “feminine” objections - were voiced by various American interviewees, male and female, and in some respects more emphatically than by Dutch respondents.

American views on a good sense of humor

The joke is not as fruitful a starting point for exploring American humor styles as it was in the Netherlands. As a genre, it is nowhere near as contested as it is in the Netherlands. Neither is it as strongly connected with social categories. Therefore, I now turn to broader American humor styles, in order to ask: what is the cultural logic underlying American conceptualizations of good humor and bad taste? What sort of criteria do Americans use to distinguish good humor from bad? How is this related to social background? Why do opinions about the joke not function as a basis for social distinction?

As in the Dutch interviews, I asked all interviewees to describe someone they knew with a good sense of humor. American answers were much more diverse than the straightforward intellect-versus-sociability pattern found in the Netherlands. However, in the midst of this variety, there was one constant: a similarity in the way all American informants, regardless of education, ethnicity, gender or age, spoke about a good sense of humor. They spoke of humor in very moral terms. In the following sections, I first explore the diversity, and then turn to this very American constant.

One social background factor came, again, to the fore: gender. While most Dutch interviewees chose to describe a man with a very good sense of humor, this was more evenly divided in the American sample. Of the thirteen male respondents, only two named a woman as someone with a good sense of humor. But out of fifteen women, eight described a man, and seven a woman. Thus, even though the sense of humor is more associated with men in the US, too, American women are oriented more towards other women. One might say that, whereas in the Netherlands I found what looks like a sexual division of labor, what we see here is more like a case of separate worlds: men joking primarily with men, but women joking with men and other women.

Women’s descriptions of someone with a good sense of humor were quite similar. Of the fifteen women, eight used the same word, which only one of the male interviewees used: “silly”.

I guess that’s where I get the goofiness from... She [mother] just, I don’t know, all of a sudden does something just goofy, just a weird position or says something silly.

(Special education teacher, F, 47)

Kind of silly, clumsy you know like cutting up. Yeah, silly is a good way to put it: not afraid to embarrass herself by doing something kind of silly, kind of self-deprecating.

(Freelance writer, F, 42)

He [boyfriend] is just so silly that you just want to look at him and laugh... I think we are both silly. And we must, he makes me laugh all the time, I mean we laugh at each other... like giggling, like laughing a lot in situations that I wouldn’t. But when I am with him I am giggling too. It is almost like you know when you’re a kid with your friends, like stealing your brother’s underpants and putting them in the tree and like hahaha. I feel like I have that sense of humor with him but it’s like I think I have to have, like, a certain level of personal intimacy with someone before I can be silly.

(Marketing consultant, F, 39, Latina)

Almost all female interviewees gave similar answers. I discovered a rich American vocabulary for humorous craziness: silly, goofy, off the wall, zany, kooky, loopy. The freelance writer cited earlier described herself (positively): “My kids think I am crazy, wacky, funny, childish.”

These descriptions place humor firmly in the domain of playfulness and non-seriousness: humor as “sweet madness” (Fry 1963), associated with childishness and release. In this conception, humor is contrasted with seriousness and the domain of work. The nurse cited earlier:

As far as black men are in everyday life, I don’t think they are humorous, I think that they are faced with so much that the humor goes right out the door. And for me to tell my husband’s colleagues at work that “he’s funny” and they are like “no, Eric, no”. And for me I am like, yeah, and you know he’s a really silly guy, but you know the people at work would never know it. Because he has, I guess, a standard to look up to and he doesn’t have time to, you know, to be humorous.

Thus, “silly” humor is located in the private domain, of the home, the children and the family, traditionally the domain of women.

These descriptions of silly humor often were combined with humor described earlier (in Chapter 3) as prevalent among Dutch women: shared humorous fantasies and funny stories about personal experiences. One example of this was cited earlier: the friend who wanted to send her dog to boarding school. Such stories fit well with this description of silliness: a combination of non-seriousness, exaggeration, and self-deprecation, often closely connected with specific relationships.

Men’s descriptions of good humor revolved more around having fun and creating a good atmosphere. The building contractor described “a super joke teller”. A database programmer characterized his co-worker as: “one of those brash, you know like, life-of-the-party kind of guys, warm and outgoing.” The hotel owner mentioned his bartender because “he can make anybody laugh”. And an architect lauded his wife’s sense of humor: “She loves to have fun. Good clean fun, where nobody gets hurt or feels bad.”

Prominent in male interviewees’ descriptions of a good sense of humor were descriptions of insulting and transgressive humor. “Joking around, insulting each other all the time, always poking fun at others”, as the biochemist describes his co-worker. “We’ll be sitting at the bar, and treat the waitresses abruptly, and anyone who comes in. Some of the guys are very witty, very fast. It’s great fun but you have to be able to take it”, as a 73-year old retired police officer explained. A 28-year-old African-American who worked in a customer service department (and occasionally as a model) described a friend with an excellent sense of humor: “A real idiot! He is such a sarcastic idiot. This guy, he is just so out there, things he finds funny are so ridiculous. He will watch an action movie and somebody will die and it will be really serious, and he will start laughing, and then I will laugh too. He has a sick sense of humor.”

What these men describe is reminiscent of the “tiny conspiracy” of sharing transgressive humor, described in Chapter 8 as a pleasure appealing more to men. The factor analysis, too, indicates that men enjoy such (mildly) offensive humor better. However, most of the male informants expressed reservations about truly transgressive humor. Only three men professed to like the really “sharp” jokes comparable to Dutch “hard humor”. The first was 43-year-old man working in a casino, a great admirer of Andrew Dice Clay. He also commented that Michael Moore, the satirical filmmaker who has just attracted a lot of attention with this documentary Bowling for Columbine (2002) “did not have enough viciousness”. The others were the black customer service worker cited above, and the biochemist who disliked jokes, but preferred African-American humor for its “edginess”. Generally, African-American humor seems sharper and more transgressive than mainstream American humor. However, there are not enough African-Americans in my sample to truly corroborate this.

The casino worker’s perspective on humor, which he likened it to some sort of guerilla technique, illustrates the appeal of transgressive humor but also the importance of being “able to take it”:

If I hear a joke, I love to retell it, yes. Usually my mother-in-law, of all people, I share a lot of the jokes with. She’s a good joke teller too. She’s in her mid 60s. And, you really gotta go a ways before you can offend her too. You really can’t be inhibited when you tell a joke, you gotta be able to fire it off to where you catch the people off guard. You know, when the punch line comes up, they gotta be astonished. They can’t know it’s coming at you. I think that’s very, very important in how you tell a joke. Presentation is a hundred percent.

So, what makes your mother-in-law a good joke teller?

She has no emotion. Like, she won’t start laughing - you know, like some people, they can’t get a joke out without laughing before the punch line’s out. She can sit there with a deadpan face and tell the whole thing and then burst out laughing. Same thing with me. I can do the same thing. You gotta be able to fire it off without any emotion. So they don’t know what’s coming at them. And then, when it hits them in the face, it’s like: wow!

He was one of the two interviewees who enjoyed Fokke and Sukke. He connected his love of offensive humor to his regional background: calling it “Jersey humor”, referring to the urban, hard-hitting, lower-class image of New Jersey. Among American men, descriptions of a good sense of humor seemed more colored by educational, class and ethnic background. The female focus on playfulness and shared storytelling generally overshadowed educational differences, race and ethnicity.

In the US, upper middle-class interviewees were more likely to connect a good sense of humor with intelligence, wit and “clever” jokes. In this sense, they were like Dutch lovers of highbrow humor: they favored complexity and intellectual challenge. However, they did not favor the emotional ambiguity, shock effects, or “hardness” described by Dutch educated informants. To Americans, people with a good sense of humor were always nice, likeable people, whereas in the Dutch highbrow humor style, a person with a good sense of humor might be an unpleasant person. Thus, American criteria for good humor were primarily connected with sociability (and morality), not with the emotional detachment and intellectual stance of the “pure gaze” or a Bourdieusian “aesthetic disposition”.

Characteristic of the interviewees with upper middle-class professions - both men and women - is their focus on “topical” humor, especially political humor. A preference for political humor is probably the strongest, and most conscious, marker of highbrow humor I have encountered in the US. Generally, they expressed a preference for humor “with a meaning”, or “underlying seriousness”:

Well they laugh at themselves, they laugh at issues that other people take gravely serious and at the same time they make you think about the truth underlying the sarcasm. And I think that it takes an intelligent person to be able to make a serious message but at the same time get you to laugh.

(Lawyer, M, 56)

Finally, there was one American way of describing someone with a good sense of humor that I had never heard in the Netherlands. Five interviewees, all under 35, described their friends with a good sense of humor as someone with whom to share references to film and television comedy: “She’s very funny. And she’s got like this intense memory for movie references, comedy references”, a 25-year-old grade-school teacher describing her friend. Similarly, a 28-year-old medical student describing his best friend’s humor: “We watch the same shows, and we will always be referring to it, you know, the Simpsons, Seinfeld... I remember I saw Caddyshack [film] with him and it was so funny for me and I was only like fifteen at the time and it’s just one of those movies where we will just repeat the lines and just laugh.”

Sharing film and TV references is not unlike highbrow snobbery: discussing cultural products, making arcane references. However, the references are transposed to the domain of popular culture, and the group boundaries involved are mostly age-related. These interviewees also flaunted their expertise: “The Simpsons is not as good as it was”. “Everybody loves Raymond is clearly very well written but just not as original.” In effect, this is the most explicit form of cultural (rather than political) distinction based on humor I encountered in the US. It also has the same exclusionary effect, with references self-consciously inaccessible to others.47

To sum up: it was not possible to isolate as clear-cut a pattern as the intellect-sociability pattern found in the Netherlands. Instead, American interviewees have at their disposal a wider variety of “repertoires of evaluation”, to use the term coined by Michele Lamont (1992). Moreover, these repertoires are not strictly separated from one another. In the course of one interview, a single person could talk about humor in a variety of ways. Different criteria could be used to assess a person’s good sense of humor and to describe the humor of a good television show. The same interviewee might speak differently again of using humor in the workplace. In comparison with Dutch informants, I found notably less continuity between standardized humor (television shows and comedians) and the humor of everyday life in American humor styles.

The pattern that emerges here is quite different from the Dutch one. Different social groups in America don’t have the clearly distinguishable humor styles found in the Dutch study, with the clear underlying logic, leading to radically different interpretations and evaluations of the same humor. Instead, Americans of all backgrounds have a variety of criteria for good humor, which differ between domains and types of humor. This greater diversity in American descriptions and evaluations of “good humor” also accounts for the less frequent and less radical denunciations of other people’s humor.

In the few instances that people explicitly rejected humor, this was more likely “upward” rejection:

There’s an intellectual humor, and there’s the totally wacko abandoned kind of humor. Yeah I think there’s different forms of humor, the thinking kind of humor is more satire, I mean you have to work harder to get it, and you gotta have a certain amount of intelligence in order for it to transfer to you or for you to prefer that kind of humor. And I think again that is where political humor falls, it sort of taunts the intellect, humor like M*A*S*H, it’s intellectual. I don’t prefer it as much, I’d rather it hit a funny bone other than up here [taps head], you know? ... I’ll get it. Intellectually I’ll get it, I have enough smarts, I feel manipulated when it’s kind of like given to me as one thing and then it turns out as something else. It is like a bad date.

(Theatre technician, M, 52)

As in the Netherlands, working-class or lower middle-class Americans often expressed the notion that their humor was better than the humor of “uptight” or “stiff” intellectuals with their “complicated” humor. However, in the Netherlands these rejections were symmetrical: educated people also believed their humor to be better. In the US, anti-intellectualist critiques of highbrow snobbery were not counterbalanced by intellectual dismissals of unsophisticated humor and “intellectual poverty”.

This variety in repertoires is greater for men than for women, who have a more strongly delineated understanding of humor as playfulness and silliness. This is a standard for good humor that excludes some forms of humor: transgression, explicit political references, and brash jokes. People with more education also seem to have a wider variety of repertoires at their disposal: they enjoy both the sociable humor of joke telling and clever, topical wit.

Thus, in a roundabout way, this study supports the “omnivore” thesis (Peterson and Kern 1996; Holt 1997; see also Chapter 4) in the American context. People with higher status have neither more specific tastes, nor more exclusively “legitimate” tastes; instead, they have broader tastes, including more inaccessible highbrow and popular tastes. In the domain of humor, American men apparently are more omnivorous than women. This may be related to the fact that omnivorous cultural consumption is a marker of high status, which men are more likely to have than women.

In the US, it is harder than in the Netherlands to pinpoint social distinctions based on someone’s humor. A broad taste implies that high-status people have less to dislike, thus less to look down on and reject. The absence of a strong discontinuity between highbrow and lowbrow humor in the US also means there is no “legitimate” humor taste that is really inaccessible to less educated people.

In general, it was much harder to get Americans to draw explicit boundaries between themselves and people with bad taste in humor. If they expressed dislike of another person’s sense of humor (which eventually most of them did), they did not derive their criteria from the domain of sociability, sophistication, or intellect. All interviewees used the same standard to reject “bad humor”: morality.

“You gotta have a sense of humor”: Humor and the moral self

Despite the variety in American evaluations and descriptions of a good sense of humor, one element returned in most descriptions of someone with a good sense of humor. No matter whether people were talking about someone to share movie references with, whom they could playfully insult, or someone who was “witty”, “kooky” or “the life of the party”, virtually all interviewees also described this person as someone of moral quality: “a good person”.

Specific phrases kept coming up in descriptions of people with a sense of humor. They “can find the humor in everyday life”; “can look at bad things from a humorous perspective”. He or she is “a person who can laugh at him/herself”. Often, people with a good sense of humor were commended for their “self-deprecating humor”, their use of humor to “relax” and “lighten up” themselves and others, their ability to “make light” of bad experiences. People with a sense of humor were not “hurtful” or “offensive”, but used humor “in a positive way”. For instance, the biochemist described someone who liked to tease, but also:

He’s very self-deprecating, where he can make fun of himself, type of thing. He doesn’t take life too seriously. That’s kind of, when I think of somebody who’s funny, that’s kind of what I think of.

So that’s your definition of a good sense of humor. Or are there other ways?

Yeah, I think being able to laugh at yourself. At the very same time, this person is very sensitive to other people. He doesn’t go - doesn’t make fun of other people but yet, only if, he would only do that if he knew you very well. Be joking, in a joking way. Not being mean about it.

Even though this is reminiscent of sociable Dutch humor, these phrases and descriptions strike me as much more moral in tone. By showing a good sense of humor, you are not just trying to be nice or create a good atmosphere, you are also showing your moral worth.

Often, humor was connected directly with personal quality. The freelance writer who described herself as “wacky” said:

Yes, I think a sense of humor would make you a good person, because to have a sense of humor you need to be able to relate to others, to empathize, sympathize, understand what it is like to be somebody else. Just relate in general.

And a 39-year-old technical helpdesk operator (F, black/Latina) said:

If you don’t have a sense of humor you are also kind of closed minded, ’cause you are not open to other people’s opinions. You have to have a sense of humor when you are dealing with all types of people. And if you don’t have a sense of humor and you get offended easily then you’re in the wrong job.

Clearly, humor here means more than making sure that people are having a good time, and not taking offense or getting hurt. It is connected explicitly with the way in which you relate to others. It is grounded in personal authenticity.

This moral discourse surrounding humor was present in all interviews but one: the casino worker with the “Jersey humor”. With this one exception, there was not only more talk of morality than in the Netherlands, but also a different sort of moral discourse. While Dutch interviewees focused on negative aspects of humor and morality - how not to go too far, how not to hurt others - the Americans spoke of humor as a positive moral force. I have never heard Dutch people say things like:

I would say that someone that can keep his humor throughout life is, you know, is somebody that is like close to sainthood, because there are so many wrong things going on in the world which you would have to see if your eyes are open and have to talk about, but there is a medicine to, about, how to turn that around and be able to laugh at it. You know it just sort of floats, you float about all the turmoil and all the grief.

(Theatre technician, M, 53)

I guess ’cause I’m very serious about humor. And in my life, my value about humor is to use humor to make people feel better, to bring people closer, to make something very difficult easier to bear, to give an insight or perspective that might be hard to get otherwise. To give a sense of proportion to troubling or difficult events. So it’s sort of entwined with values for me. And there’s no values [laughs] in Seinfeld. So, like, Everybody Loves Raymond, for example... when I come across it, I’ll watch it. There are some significant underlying values being expressed there about family and intimacy and, uh, honesty and so forth. That, I mean, we’re not talking Tolstoy, here, but, but it’s both very funny and not offensive to me. Because there’s something underpinning the humor.

(Works in food co-op, F, 53)

So do you think a sense of humor is important in life?

I mean you can get by without it but, to me personally, I think it’s one of the best things, it helps you to relax, it’s a good thing. I definitely have to have it in my life.

So could you live without humor?

Me personally, no. I’d curl up in a little hole and die somewhere, I think, [laughs] Yeah, yeah, I definitely have to have it in my life. Besides God, that’s one of the things that gets me by, definitely.

(Special education teacher, F, 47)

So, good humor, even in the guise of a sitcom, “expresses values” about things like “intimacy” and “honesty”. Sometimes, this moral discourse on humor borders on the religious (“sainthood”, “Besides God”).

Two things were mentioned as especially important: being able to laugh at yourself, and being able to laugh at bad things. Precisely the two things in life people are most likely to take very seriously. Thus, this view of humor almost implies a moral imperative. Indeed, there is an American phrase, often repeated when I explained my research project, which suggests such an imperative: “You gotta have a sense of humor”.

In this perspective, having a sense of humor means showing a “moral self”. This moral understanding of humor in the United States eclipses all other conceptualizations of humor. Whether people preferred silly or meaningful, transgressive or more innocuous humor, they linked it with these notions of morality, selfhood, and personal authenticity.

However, a moral view sits uneasily with some of the other characteristics of humor, such as a proclivity to touch on moral boundaries. Transgressing boundaries, albeit in jest, is a risky way to express your moral self. As described in Chapter 7, the humorous mode tends to temporarily shut off morality. It was already difficult for Dutch joke tellers to combine good humor with moral requirements; they grappled with the question of how to combine transgressive jokes and “hard humor” with their notion of sociable humor. For American interviewees, the inconsistencies were even greater.

This was a problem particularly for the male informants, who generally preferred more offensive jokes. The female preference for playful humor is more easily combined with morality. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most outspoken “positive moralists” I spoke to were women. Typically, women are the guardians of morality (e.g. Bourdieu 1998). It is not surprising, therefore, that in the American moral conceptualization of humor, gender differences emerge more prominently than in the Netherlands.

The American focus on morality as a means of social distinction has emerged from other comparative studies, mostly comparing the US and France (Heinich 2000; Lamont 1992, 2000; Lamont and Thévenot 2000). Lamont shows extensively how both American upper middle-class men and blue-collar workers are much more likely than their French counterparts to evaluate others in terms of honesty, morality, and personal moral worth than in terms of refinement or financial achievements. She has suggested adding “moral capital” to cultural and economic capital as a third form of symbolic capital, as the basis for drawing “symbolic boundaries”.

In this respect, Lamont’s work is an important addition to, and correction of, Bourdieu’s and other sociologists’ work studying social distinctions through money, education, and lifestyle. In Distinction, Bourdieu writes rather dismissively of morality: as a means of distinction for those who have nothing else to prove their worth. However, within the American context, morality is central to the way people judge themselves and others. Lamont’s insights are confirmed by this study, which shows the important role morality plays in the American discourse on humor - not just in a negative sense, as the outer limit of good humor, but in a more positive sense. To Americans, good humor is moral humor.

The effects of this positive moral discourse on humor are discernable in the American humorous tradition, which is less edgy, transgressive, and controversial than Dutch humor, and European humor generally. American humor tends to be upbeat, inclusive, and often comes with a meaning, or a moral lesson. Even The Simpsons, a quintessentially American show that seems nihilistic and sarcastic at first, is generally recognized as portraying a family that is dysfunctional but nevertheless loving and close.48 Americans who joke at the expense of others, in private and public settings, will generally make sure to joke about themselves first, a tactic especially important for late-night talk show hosts such as Jay Leno and David Letterman. The moral view of humor has also put restrictions on humor in the public domain, especially on television, where certain words and topics are off limits.

In everyday life, too, Americans tend to be stern in judging offensive and transgressive humor. While interviewees were careful when judging the form and style of other people’s humor, they commented explicitly on humor they felt was hurtful or offensive. They also voiced strong dismissals of the people enjoying or creating this humor. Some of these, at times harsh, judgments of others are cited in this chapter, especially in the objections to jokes: “off-putting in terms of relating to others”, “demeaning”, “mean”, “degrading”.

The Dutch rejections are based in cultural and social divides, and rather easily translate into social demarcations and denunciations of specific groups. In contrast, it is less easy to establish exactly who is targeted by these rejections based on morality. On the whole, American moral talk centered more on sexuality, language use, and was more religious in tone than in the Netherlands (cf. Kuipers 2006b). But, even within this small sample, I found a wide variety of moral views, and thus a wide variety of exclusions or judgments that something or someone was morally “bad”, based on their humor.

In the US, differences in moral boundaries did not seem to be related to age differences in humor style; I found almost no rejection by older interviewees of the more offensive humor of the young (or vice versa). The social background factor most strongly connected with morality was gender: women objected more to offensive humor, and tended to engage more in “positive” moral talk. Moral distinctions also translated into distinctions based on politics and religion (which often converge in the United States).

In a more subtle and veiled way, moral boundaries were connected with distinctions based on race, class, and ethnicity. At times, there was a strong moral undercurrent in upward objections to “intellectual” people who were “uptight” or “took themselves too seriously”. Also, intellectual humor was often equated with “sarcasm”, a form of humor frowned upon, which one woman described as being “too much on the negative side”. These American objections to “highbrow” humor are therefore quite different from Dutch objections to highbrow styles, which focused on incomprehensibility, a general lack of humor, excessive emotional restraint and, occasionally, hypocrisy. Most of these objections are stylistic and cultural, and only the last argument could be called moral (cf. Friedman and Kuipers 2013).