Lighthouse Avenue, Pacific Grove, circa 1910–15.

After months of living hand-to-mouth as newlyweds in Eagle Rock, John and Carol headed north to familiar Pacific Grove, where they would live for six years. Steinbeck’s parents gave them twenty-five dollars a month and the family’s three-room summer cottage that his father had built early in the century.

While Carol combed the peninsula for jobs, John wrote daily—determined, as he had been since he was a teenager, to find an audience for his prose. “I expect to give myself until I’m forty,” he wrote a friend. “That will be twenty-five years of trying.” In Carol, he found a woman who endorsed his steely determination. Throughout the Pacific Grove years, she was his ready companion, muse, editor, and typist. Theirs was a collaborative marriage, happy, stormy, and committed.

During the Great Depression, Pacific Grove was an ideal spot for an artist or a visionary. Founded as a Methodist retreat in 1875, the town was quiet, affordable, often surprisingly progressive, and dry—alcohol consumption was banned until 1969. Steinbeck needed solitude; he needed Carol to buffer him from the world; he needed a familiar setting, a tiny workroom, friends and family close by, a garden, and a dog. During the six years in Pacific Grove, Steinbeck went from being an unknown writer with one book to his name—Cup of Gold, which appeared in 1929 to scant reviews—to an accomplished author with five published works of fiction.

In Pacific Grove, John Steinbeck found his authorial voice. “I must have at least one book a year from now on if I can manage it,” he wrote in 1930, shortly before moving to Pacific Grove. During the 1930s, he almost reached his target.

Pacific Grove Cottage, circa 1908.

“Such a nice little place. And once there were good times there.”

In their tiny cottage two blocks from Monterey Bay, John and Carol Steinbeck were as financially and ideologically detached from the Pacific Improvement Company and Del Monte revelers as Steinbeck had been from the growers of the Salinas Valley. During their Pacific Grove years, John and Carol were comrades, a team, themselves against the world. They were unconventional, plucky, and resolute. Both delighted in the unexpected: Once they took friend Ed Ricketts’s iguana, strapped it to a roller skate, hooked a leash to the skate, and walked nonchalantly down Cannery Row. Like Ernest and Hadley Hemingway in 1920s Paris, John and Carol dressed alike, both in rough garb, pants, and slouchy jackets. Together they caught fish in the bay in their small boat—rockfish and salmon. “Sometimes I catch eels and sea trout and the Italian fishermen take us fishing in their boats,” he wrote a friend. At times, they got their food from the welfare office—two cans of peaches, one pound of cheese, and a can of corned beef, according to Carol. And they both loved their large backyard garden. At one low point in 1931, starved for amusement, John and Carol bought two ducks for the garden pond and named them Aqua and Vita. (The birds proved to be too expensive and too noisy, however, and had to go after a couple of weeks.) Neither John nor Carol was afraid of hard work. What sustained Steinbeck during those rocky years in Pacific Grove, when he had so little money or critical acclaim, was the writing itself and a wife who shared his passion for language and believed with unswerving conviction in his ultimate success.

Carol Henning Steinbeck shared her husband’s Bohemian tastes. Like Grampa and Granma Joad, John and Carol “fought over everything, and loved and needed the fighting.” Carol was Steinbeck’s unflinching critic. She was also creative and iconoclastic herself—not a fan of the ladies who stayed at the Hotel Del Monte. She sketched a series of pink nude sportswomen. She wrote “feelty verse,” as she told a reporter. She gave her self-published 1933 volume, A Slim Volume to End Slim Volumes, to John for Christmas. Here is one of her poems:

I Don’t Like Mr. Hearst

Mr. Hearst has no soul

I hope he falls down into a hole

I wouldn’t touch Mr. Hearst with a ten-foot pole.

He makes me sick. I’ve got no use for this cheap skater

I hope he breaks his neck on a potater,

And nobody finds it out until nine months later,

Or never.

From Carol’s series on nude sportswomen.

John and Carol with duck in photo booth.

Steinbeck in the 1930s.

Joseph Campbell, who came to the peninsula in 1932, thought Carol got a raw deal in this marriage contract: no children, a preoccupied husband. But Carol was committed to John. “Nothing mattered but John,” she would say later, “I put all there was of me into his life.”

Carol worked at odd jobs on the peninsula. In 1931, shortly after arriving, she and a friend created the first directory of Carmel residents; she worked as Ricketts’s secretary; and she worked for State Employment Relief. For his part, Steinbeck wrote daily, usually until late afternoon. He mentally composed stories, seemingly, and wrote out clean copies rapidly, often in his father’s used ledger books in order to save money on paper. The act of writing obsessed and haunted him, consumed and transformed him. As completely as was possible, he merged self with work. To write, he went into a trance of sorts—a “work dream” he called it in a 1948 ledger: “almost an unconscious state when one feels the story all over one’s body and the details come flooding in like water and the story trudges by like many children.” There is a physicality to his discussions of work that testify to its hold on him: “when there is no writing in progress, I feel like an uninhabited body,” he wrote to one friend. Creative products became offspring. He described one work as a “literary foetus.” Characters, he said, “are my own children.” Writing books gave him “satisfaction … much like that of a father who sees his son succeed where he has failed.” Letters repeat this refrain—books, not children, were his progeny, his destiny. Carol may well have wanted children—she probably was pregnant and had an abortion at some point in the 1930s—but she knew that he didn’t and wouldn’t.

“I think flowers’ colors are brighter here than any place on earth and I don’t know whether it is the light that makes them seem so or whether they really are.”

Wall opposite fireplace at 147 11th Street.

In those Pacific Grove years, secure in familiar surroundings and married to a supportive woman, Steinbeck contracted both his penmanship and his world to the demands of his own imagination. Moods blended with the foggy coastal weather, as he wrote a friend: “It is a gloomy day; low gray fog and a wet wind contribute to my own gloominess. Whether the fog has escaped from my soul like ectoplasm to envelop the peninsula, or whether it has seeped in through my nose and eyes to create the gloom, I don’t know.” Many of the stories he wrote during those first raw years in Pacific Grove (published in 1938 in The Long Valley) are about people living sheltered, often desperate, and lonely lives. Steinbeck, unhappy in his own fictional progress, struck tones of defeat and ostracism and rejection, emotions he knew so intimately. In Pacific Grove, this intensely private, unsettled young man, familiar with the demons of loneliness and despair, created fictions that reflect his own psychic complexity.

The loneliness of unsheathed self is one fictional chord struck by this burgeoning writer in his beloved Pacific Grove retreat. Home as a haven is another.

The unassuming red cottage at  147 11th Street, where John and Carol Steinbeck came to live in the fall of 1930, represents something essential to both of them, something at the core of Steinbeck’s fictional vision. Steinbeck made simple living his personal and fictional terrain. Throughout his life, he wrote about ordinary people; he, for the most part, had Spartan tastes. Even when fame came to him in the 1940s and 1950s, he never purchased houses that flaunted wealth. His house in Sag Harbor, where he spent summers from 1955 to 1968, was an East Coast version of the 11th Street home, a tiny cottage perched near the sea. Travels with Charley is a narrative about his own traveling house—a compact and simple camper on top of a pickup truck that protected his anonymity as he drove across America. He wanted the same in 1930s Pacific Grove: “Must have anonymity…. Unless I can stand in a crowd without any self-consciousness and watch things from an uneditorialized point of view, I’m going to have a hell of a hard time,” he wrote his agents in 1937. The Pacific Grove cottage sheltered his identity and his spirit.

147 11th Street, where John and Carol Steinbeck came to live in the fall of 1930, represents something essential to both of them, something at the core of Steinbeck’s fictional vision. Steinbeck made simple living his personal and fictional terrain. Throughout his life, he wrote about ordinary people; he, for the most part, had Spartan tastes. Even when fame came to him in the 1940s and 1950s, he never purchased houses that flaunted wealth. His house in Sag Harbor, where he spent summers from 1955 to 1968, was an East Coast version of the 11th Street home, a tiny cottage perched near the sea. Travels with Charley is a narrative about his own traveling house—a compact and simple camper on top of a pickup truck that protected his anonymity as he drove across America. He wanted the same in 1930s Pacific Grove: “Must have anonymity…. Unless I can stand in a crowd without any self-consciousness and watch things from an uneditorialized point of view, I’m going to have a hell of a hard time,” he wrote his agents in 1937. The Pacific Grove cottage sheltered his identity and his spirit.

John built the fireplace at the 11th Street house in 1930; the turtle is probably from the Sea of Cortez trip.

“We went to PG and closed the little house for the duration of the war. Wish we could have stayed. It was so pleasant and quiet. I would have liked to just sink into it. The garden was so quiet and nice and the ocean just the same as always.”

“The White Quail,” a 1933 story, begins with a description of a view similar to that out of Steinbeck’s Pacific Grove window: “small diamond panes set in lead. From the window … you could see across the garden.”

Steinbeck’s lineage was in the soil. Grandfather Sam Hamilton was a rancher. Grandfather Steinbeck dried and shipped apricots and plums from his Hollister orchard. At age 90, Grandmother Steinbeck was still making jams and jellies from their fruit. At the Pacific Grove cottage, Mr. Steinbeck cultivated vines and flowers in the yard as early as 1905 and worried often about the upkeep of the flowers in later years.

John Steinbeck carried the hoe, so to speak. At age three, he made a garden for Grandmother Steinbeck, “and planted me radishes and lettuce,” wrote a delighted grandmother. He dug in the wet soil at Lake Tahoe in the mid-1920s and sent his parents a box of scarlet snowflower sprouts by mail, with detailed instructions for their propagation; they, in turn, sent him nasturtium seeds. And he shared with his father a warm connection to the Pacific Grove lot, the “wonderful” garden, “very wild and full of weeds and the flowers bloom among the weeds. I detest formal gardens.” He would write about that garden often: “My garden is so lovely that I shall hate ever to leave it,” he wrote a friend in 1931. “I have turtles in the pond now and water grasses. You would love the yard. We have a vine house in back with ferns and tuberous begonias. We have a large cineraria bed in bloom and the whole yard is alive with nasturtiums.”

Site of the pond in the garden of the 11th Street house.

Pacific Grove and Monterey sit side by side on a hill bordering the bay. The two towns touch shoulders but they are not alike. Whereas Monterey was founded a long time ago by foreigners, Indians and Spaniards and such, and the town grew up higgledy-piggledy without plan or purpose, Pacific Grove sprang full blown from the iron heart of a psycho-ideo-legal religion.

Few places in California could have better sustained this young writer than the conservative, neatly planned enclave of Pacific Grove—quiet, orderly, a “city of homes,” declared promotional brochures, with “saloonless streets.” From its inception, Pacific Grove was the most subdued of the three peninsula towns, the starchiest, a place of “deep quiet,” wrote Steinbeck. The location of Pacific Grove was “so healthy that doctors scarcely make a living,” promised an 1875 pamphlet. Summer fogs keep Pacific Grove cool. It was a town perfect for a writer who craved solitude.

The town’s moral sensibility was set by Methodists, who in 1875 announced plans to found a seaside retreat in Pacific Grove. The Pacific Grove Retreat Association formed an agreement with wily David Jacks for the “purchase, improvement and control” of 100 acres of beachside property. Lots were drawn out—thirty-by-sixty-foot “tenting lots”—to accommodate some four hundred people, and on August 9, 1876, the first camp meeting was held at the Grand Avenue open air temple, lasting three weeks.

To attract additional visitors, an Assembly and Summer School of Science was instituted in 1879 under the umbrella of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle. Summer residents from the hot Central Valley were promised a series of edifying lectures and courses. Across America, Chautauqua Circles were popular for nearly half a century, offering adult education for the masses. By the 1890s, more than fifty such summer assemblies could be found in the United States, five on the West Coast. “It took the whole intellectual product of the period, decanted and distributed it with sincerity and skill,” wrote Mary Austin in a 1926 issue of the Carmel Cymbal. She added, “There can be no doubt that a vast majority of Americans, particularly American women, sincerely suppose that ‘culture’ is generated in ‘courses,’ and proceeds as by nature from the lecture platform.” Indeed, Austen’s assessment has merit. But, for nearly fifty years in Pacific Grove, many families found the sea and intellectual dabbling a fine mix. A 1,500-seat  Chautauqua Hall was built in 1881 and still stands. Here, attendees listened to lectures by ministers, scholars, and scientists or attended talks on cooking, music, and art. The 1892 session promised, for example, David Starr Jordan, then president of Stanford University, lecturing on the “Passion Play at Oberammergau” with stereopticon illustrations, as well as a “charming astronomical” lecture. A season pass that year cost three dollars, and daily tickets cost fifty cents. The Chautauqua was a profoundly egalitarian movement.

Chautauqua Hall was built in 1881 and still stands. Here, attendees listened to lectures by ministers, scholars, and scientists or attended talks on cooking, music, and art. The 1892 session promised, for example, David Starr Jordan, then president of Stanford University, lecturing on the “Passion Play at Oberammergau” with stereopticon illustrations, as well as a “charming astronomical” lecture. A season pass that year cost three dollars, and daily tickets cost fifty cents. The Chautauqua was a profoundly egalitarian movement.

Cover of 1892 Chautauqua program.

All his life, Steinbeck needed a garden and a dog, sources of creative fulfillment. After all, without ambassador Charley, what spark would his travels have ignited? A dog was family. When he lived alone at Tahoe, he shared the cabin with Airedales Omar and Jerry.

When they were first married, John and Carol rented and fixed up a house in Eagle Rock and bought their first family dog, Bruga, a “Belgian shepherd puppy, pure black, which is going to be a monster.” A few months later, in May 1930, Bruga “died in convulsions which seemed to be the result of poison.” Steinbeck wrote, “Carol is well but very much broken up about Bruga. She never had a dog of her own before and she had become horribly fond of the little wretch.” Dogs were emotional outlets for both of them, sources of humor and despair. In Carol’s 1930s scrapbooks, photos of dogs are carefully labeled. People are rarely identified.

“Joggi, 14 months.”

An Airedale named Tillie replaced Bruga in 1931, and she had puppies, “as sinful a crew as ever ruined rugs…. At present they are out eating each other…. They are eating the fence now. The appetite of a puppy ranks with the Grand Canyon for pure stupendousness.” Alas, Tillie got distemper, and Steinbeck—in a fit of odd temper himself—pulled out the dog’s whiskers “to strengthen their growth.” Tillie, “who had the most poignant capacity for interest and enjoyment in the world,” lived only eighteen months with the Steinbecks and then died, leaving Steinbeck bereft: “I need a dog pretty badly,” he wrote to his publisher a few weeks later. “I dreamed of dogs last night. They sat in a circle and looked at me and I wanted all of them.” In Tortilla Flat, Pirate’s dogs also sit in a circle and gaze at him with devotion. The dog Darling in Cannery Row is undoubtedly as spoiled as Steinbeck’s many pooches were.

“It wasn’t all fun and parties,” Steinbeck wrote in an essay about the 1930s. “When my Airedale got sick, the veterinary said she could be cured and it would cost twenty-five dollars. We just couldn’t raise it, and Tillie took about two weeks to die. If people sitting up with her and holding her head could have saved her, she would have got well. Things like that made us feel angry and helpless.” Helplessness was always, for Steinbeck, leavened by a quirky humor that never failed him: he rounds this paragraph with a characteristic grace note: “When WPA came, we were delighted because it offered work. There were even writers’ projects. I couldn’t get on one, but a lot of very fine people did. I was given the project of taking a census of all the dogs on the Monterey Peninsula, their breeds, weight and characters.” (That was not his job but it was Frances Whitaker’s, who took a census of dogs and cats in Carmel for the WPA, a short-lived position.)

Steinbeck had to rewrite Of Mice and Men, the last book started in the Pacific Grove house, because a ravenous young Toby, their new puppy in early 1936, ate the first part of the manuscript. “John went completely berserk and had to be locked up,” said friend Marjory Lloyd. In a more temperate mood a few days later he wrote, “Minor tragedy stalked. I don’t know whether I told you. My setter pup, left alone one night, made confetti of about half my ms. book. Two months work to do over again. It sets me back. There was no other draft. I was pretty mad but the poor little fellow may have been acting critically. I didn’t want to ruin a good dog for a ms.”

Tent cabins in Pacific Grove, circa 1882.

Pacific Grove houses today.

In 1880, David Jacks sold his ranchos, including the retreat land, to the Pacific Improvement Company, which had a greater interest in selling lots quickly than the Methodists had. Even after the Methodists lost control of land sales, the retreat association continued to guard the Pacific Grove image zealously. It was one of the first gated communities in the state; the gates closed at 9:00 every evening. The governing body, “patriarchal and unique,” according to the association, kept “without the borders of the town all disreputable, unruly and boisterous characters, and all unwholesome and demoralizing sports and pastimes.”

Undoubtedly it was climate, location, and moral uplift that drew the Steinbeck family to the town in the early twentieth century. Mr. Steinbeck’s deed, like all in Pacific Grove, included a clause prohibiting the sale of liquor on the premises—a fact Steinbeck notes in Sweet Thursday. Well into the twentieth century, moral living was Pacific Grove’s iron core, and it remained a “unique resort where culture, refinement, and morality are the prevailing attributes,” as a 1928 pamphlet declared.

When Steinbeck moved to Pacific Grove in 1930, the hot local topics were paving and widening the streets and opening a road between Pacific Grove and Carmel, which became the Holman Highway. After forty years of business, Holman’s Department Store was adding another story. The city council was trying to condemn the popular but decrepit bathhouse at Lovers Point (the city putting a value of $30,000 on the land, the owner $175,000). The paper noted regular lapses during Prohibition: “Abbott nabs brewery at Local ranch: Sheriff Seeks Salinas’ ‘Al Capone’ With his Gang fellows.” On the first page of the paper was a little column devoted to “brief items of things that make Pacific Grove a brighter and better place in which to live.” On the second page ran a “Come to Church” section. In 1932, a front page article sternly noted a man’s twin lapses: “D. A. Florey of Pacific Grove, said to be a communist organizer, is in the Monterey county jail in Salinas today pending his hearing on charges of wifely non-support.” It was a very small town.

The “city of homes” has remained just that—a pleasant community. The nineteenth-century sense of purpose, orderliness, and uplift is evident in contemporary Pacific Grove—streets numbered, the town in a grid, Victorian houses tidy, many still framed by board-andbatten construction. On little lots that once sold for fifty dollars, tiny houses—some tent structures later framed—have been restored, many decorated with monarch butterflies (Pacific Grove is “Butterfly Town USA”) or strung with Chinese lanterns in mid-July.

John and Mary. A neighbor recalled, “A man came every summer and rented a donkey cart for 25 cents per hour. On 17th and 18th streets. The block was all wooded at that time. Tents went up every summer.”

Environmental awareness came early to Pacific Grove. The yearly migration of butterflies to trees off Lighthouse Road was sharply watched, and in 1938, a fine of $500 was imposed for harm to any butterfly. Each October, butterflies from northern climes fly forty to fifty miles a day to arrive by the thousands, pile on branches, and settle in for the winter. In Sweet Thursday, Steinbeck has them as spring butterflies, “like twinkling aery fields of flowers” landing on pine branches, getting drunk on “thick resinous” pine juice, falling to the ground and “waving their inebriate legs in the air and giving off butterfly shouts of celebration, while their places on the twigs are taken by new, thirsty millions.” If not quite accurate, this is certainly a lovely notion and a nice way to perceive butterflies. Each year, as Steinbeck notes, the town does indeed host butterfly festivities.

In time, Steinbeck would own two homes in Pacific Grove; Grandmother Hamilton briefly lived in another; and John stayed for a few weeks at his sister’s cottage at Asilomar, writing Sea of Cortez. All of these homes still stand and are relatively unchanged. In a short drive around Pacific Grove, one can visit each little house—respecting, as Steinbeck fiercely guarded for himself, residents’ privacy.

In 1941, shortly before their marriage ended, John and Carol purchased a small house with a large garden at  425 Eardley Street. This was an odd little house—haunted, John would claim—with a living room ceiling curved like a tent and carved birds perched around the ceiling. Rooms in the house were lined up like a freight train, his second wife Gwyn, would complain. When he lived there, a Mexican bell hung at the gate. This house is the scene for what is, perhaps, his worst recorded moment, that of a man torn between two women—Carol, his wife of eleven years, and, Gwyn, whom he’d met shortly after publication of The Grapes of Wrath. When Gwyn came to visit in 1941, he left Gwyn and Carol alone in the house, saying on the way out that he couldn’t decide between them, that “the one who feels she really wants me the most, gets me.” Although Carol won that round—Gwyn left that day—Gwyn captured the man in the end. In April 1941 John and Carol separated.

425 Eardley Street. This was an odd little house—haunted, John would claim—with a living room ceiling curved like a tent and carved birds perched around the ceiling. Rooms in the house were lined up like a freight train, his second wife Gwyn, would complain. When he lived there, a Mexican bell hung at the gate. This house is the scene for what is, perhaps, his worst recorded moment, that of a man torn between two women—Carol, his wife of eleven years, and, Gwyn, whom he’d met shortly after publication of The Grapes of Wrath. When Gwyn came to visit in 1941, he left Gwyn and Carol alone in the house, saying on the way out that he couldn’t decide between them, that “the one who feels she really wants me the most, gets me.” Although Carol won that round—Gwyn left that day—Gwyn captured the man in the end. In April 1941 John and Carol separated.

425 Eardley Street.

The houses around Central and Lighthouse avenues, the main streets in Pacific Grove, are little changed from Steinbeck’s time.

Holman’s Department Store, 542 Lighthouse Avenue.

John’s Grandmother Hamilton—Liza Hamilton in East of Eden—lived at  222 Central Avenue from 1914 to 1918. Steinbeck never lived here; however, Carol’s sister and brother-in-law, Idell and Paul Budd, rented this house while Paul worked briefly at the Hopkins Marine Station. In 1936, Steinbeck and Paul built a small workroom for the house.

222 Central Avenue from 1914 to 1918. Steinbeck never lived here; however, Carol’s sister and brother-in-law, Idell and Paul Budd, rented this house while Paul worked briefly at the Hopkins Marine Station. In 1936, Steinbeck and Paul built a small workroom for the house.

Holman’s Department Store, at 542 Lighthouse Avenue, was founded in 1891 and boasted forty-six departments when Steinbeck moved to the area: “Known far and wide as the biggest small town store in this part of the state,” ads read. It had a grocerteria and a beauty shoppe and sold tires and home furnishings. Ritch Lovejoy, one of Steinbeck’s friends, drew ads for Holman’s. In 1932, Holman’s sponsored a “sky skater,” just like the one mentioned in Cannery Row. The sky skater is a “mysterious marvel who will thrill and entertain spectators,” reported the local paper, “by gyrating on a tiny platform far above the top of Holman’s department store.” A Steinbeck fan wrote in the 1950s asking if his model for old Doctor Merrivale, who shoots at the skater with an air rifle in Cannery Row, might be a Fresno dentist who purchased an air rifle to shoot construction workers. Steinbeck answered,

Holman’s Department Store, at 542 Lighthouse Avenue, was founded in 1891 and boasted forty-six departments when Steinbeck moved to the area: “Known far and wide as the biggest small town store in this part of the state,” ads read. It had a grocerteria and a beauty shoppe and sold tires and home furnishings. Ritch Lovejoy, one of Steinbeck’s friends, drew ads for Holman’s. In 1932, Holman’s sponsored a “sky skater,” just like the one mentioned in Cannery Row. The sky skater is a “mysterious marvel who will thrill and entertain spectators,” reported the local paper, “by gyrating on a tiny platform far above the top of Holman’s department store.” A Steinbeck fan wrote in the 1950s asking if his model for old Doctor Merrivale, who shoots at the skater with an air rifle in Cannery Row, might be a Fresno dentist who purchased an air rifle to shoot construction workers. Steinbeck answered,

No, I’m afraid it wasn’t your man. The prototype of my man was Hudson Maxim, the inventor. When he grew old he took to renting rooms in London near the corner where Salvation Army bands took their station and shooting at the bass drum with a spring gun. Time after time he was apprehended and always promised to reform. But it was a vice with him and he couldn’t give it up. It was a limited vice, however. He only shot at that one thing.

Croquet courts on the grounds of the El Carmelo Hotel, 1890s.

There was no such war, with Greens squaring off against Blues, grumpy elders fiercely defending championship titles on Pacific Grove courts. “The old men got to carrying mallets tied to their wrists by thongs,” writes Steinbeck, “like battle-axes.” No, not quite. But as early as 1900 there were roque courts in Pacific Grove. And in 1932-33 there was a war, of sorts, called in local papers a “showdown fight” or a “battle which cheerfully blazed in the city hall.” Battle lines were drawn after dedication of the splendid Pacific Grove Museum in December 1931: Donor Mrs. Lucie A. Chase, who had lived in Pacific Grove for twenty-nine years, thought it prudent to remove the unsightly roque courts in  Jewel Park, across the street from the museum, when Central Avenue was being widened. The Ancient and Honorable Roque and Horseshoe Club of Pacific Grove, however, had other notions. They had long played their game in Jewel Park and they didn’t opt for change. (Roque is a game much like croquet, but four balls are used, fired in succession, in a game lasting 2-3 hours.) “Why don’t these men put their hands in their pockets and buy a cheap little lot for their court?” Mayor Platt suggested. A hostile councilman said they should stay home and play marbles. But in April 1933 the issue went up for a vote, and the town voted 1,220 to 295 to rebuild the courts in Jewel Park.

Jewel Park, across the street from the museum, when Central Avenue was being widened. The Ancient and Honorable Roque and Horseshoe Club of Pacific Grove, however, had other notions. They had long played their game in Jewel Park and they didn’t opt for change. (Roque is a game much like croquet, but four balls are used, fired in succession, in a game lasting 2-3 hours.) “Why don’t these men put their hands in their pockets and buy a cheap little lot for their court?” Mayor Platt suggested. A hostile councilman said they should stay home and play marbles. But in April 1933 the issue went up for a vote, and the town voted 1,220 to 295 to rebuild the courts in Jewel Park.

In the fall of 1927, John wrote to his family from the shores of Lake Tahoe, “Today I have been thinking constantly of Pacific Grove. The morning started it. There was a low lying mist which made the lake look just like Monterey Bay in the morning. And then I could not get away from thoughts of the cottage and the crabs caught with beef steak and of the sand pile, and how you used to drive us to the beach when we were cross and could not think of anything to do to take up our time. The thing prevailed nearly all day.”

From 1934 to 1970, Everett “Red” Williams ran  the Flying A service station, 520 Lighthouse Avenue, across Fountain Street from Holman’s Department Store. Williams sold Steinbeck the “Hansen Sea Cow”—actually a Johnson Sea Horse—that he took with him on the 1940 Sea of Cortez trip.

the Flying A service station, 520 Lighthouse Avenue, across Fountain Street from Holman’s Department Store. Williams sold Steinbeck the “Hansen Sea Cow”—actually a Johnson Sea Horse—that he took with him on the 1940 Sea of Cortez trip.

“It was wartime and I didn’t have a new motor to sell him but I had a used one that I said I’d lend him,” Williams recalled. “That’s the last I saw of it. It didn’t run too good, and when they got down there it ran intermittently.”

Steinbeck mentions  the Scotch Bakery at 545 Lighthouse Avenue in Cannery Row, and probably bought one of their old trucks to use when he went on research trips for The Grapes of Wrath. The sign “Scotch Bakery” was taken down in 2005, after a minor community struggle to keep it up failed.

the Scotch Bakery at 545 Lighthouse Avenue in Cannery Row, and probably bought one of their old trucks to use when he went on research trips for The Grapes of Wrath. The sign “Scotch Bakery” was taken down in 2005, after a minor community struggle to keep it up failed.

Red Williams’s gas station, 520 Lighthouse Avenue.

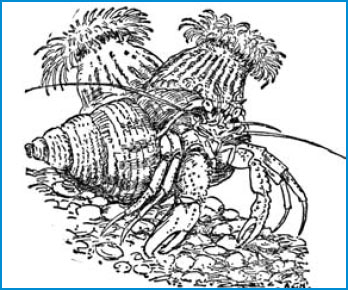

One of Ed Ricketts’s favorite collecting spots was  the Great Tide Pool, located along Ocean View Avenue. In Cannery Row, chapter 6 begins, In Between Pacific Tides, Ricketts describes hermit crabs as “pleasant and absurd” the “clowns of the tidepools”—quite similar to Steinbeck’s description of his fictional ne’er-do-wells Mack and the boys, who “ooze” into the Palace Flophouse and make it their new home.

the Great Tide Pool, located along Ocean View Avenue. In Cannery Row, chapter 6 begins, In Between Pacific Tides, Ricketts describes hermit crabs as “pleasant and absurd” the “clowns of the tidepools”—quite similar to Steinbeck’s description of his fictional ne’er-do-wells Mack and the boys, who “ooze” into the Palace Flophouse and make it their new home.

Doc was collecting marine animals in the Great Tide Pool on the tip of the Peninsula. It is a fabulous place: when the tide is in, a wave-churned basin, creamy with foam, whipped by the combers that roll in from the whistling buoy on the reef. But when the tide goes out the little water world becomes quiet and lovely. The sea is very clear and the bottom becomes fantastic with hurrying, fighting, feeding, breeding animals.

The Great Tide Pool.

“Among themselves, when they are not busy scavenging or love-making, the gregarious ‘hermits’ fight with tireless enthusiasm tempered with caution. Despite the seeming viciousness of their battles, none, apparently, are [sic] ever injured. When the vanquished has been surprised or frightened into withdrawing his soft body from his shell, he is allowed to dart back into it, or at least to snap his hindquarters into the shell discarded by his conqueror.”

People stroll and dogs cavort on lovely Asilomar Beach.  The Asilomar Conference Grounds, the “refuge by the sea,” is across the road. Built in 1913 as a YWCA conference center on land donated by the Pacific Improvement Company, Asilomar’s stately lodge and campus were designed by Julia Morgan, architect of Hearst Castle.

The Asilomar Conference Grounds, the “refuge by the sea,” is across the road. Built in 1913 as a YWCA conference center on land donated by the Pacific Improvement Company, Asilomar’s stately lodge and campus were designed by Julia Morgan, architect of Hearst Castle.

Morgan designed Asilomar in the Arts and Crafts style, using local materials and stressing harmony with the environment. Since 1956, Asilomar has been a state conference center, and rooms are also available to the public. Public wooden walkways wind through the dunes, which have been replanted with native grasses, “little trailing plants which slow up the pace of the walking dunes.” In Sweet Thursday, Ed Ricketts meets the seer near Asilomar Beach (before the dunes were transformed into Spanish Bay resort): “In the dunes there are deep little creases where the wind-crouching pines have made a stand against the moving sand, and in one of these, only a hundred yards back from the beach, the seer had his home.”

Set back in the woods at  800 Asilomar Boulevard is a little house, now on Asilomar grounds called the Guest House. In the late spring of 1941, John Steinbeck, separated from his wife Carol, stayed at his sister Esther’s “house in the woods in P.G.,” as he called it. Here he wrote part of Sea of Cortez.

800 Asilomar Boulevard is a little house, now on Asilomar grounds called the Guest House. In the late spring of 1941, John Steinbeck, separated from his wife Carol, stayed at his sister Esther’s “house in the woods in P.G.,” as he called it. Here he wrote part of Sea of Cortez.

Asilomar State Beach.

El Carmelo Cemetery, where Steinbeck’s sister Esther is buried, is at 65 Asilomar Boulevard. This is the “pretty little cemetery where you can hear the waves drumming always” mentioned in Cannery Row. Ed Ricketts’s funeral was held here in the Little Chapel by the Sea on May 12, 1948. (He is buried in El Encinal Cemetery in Monterey.) After the ceremony, the mourners walked to the Point Pinos Lighthouse, located on the northern tip of the peninsula.

El Carmelo Cemetery, where Steinbeck’s sister Esther is buried, is at 65 Asilomar Boulevard. This is the “pretty little cemetery where you can hear the waves drumming always” mentioned in Cannery Row. Ed Ricketts’s funeral was held here in the Little Chapel by the Sea on May 12, 1948. (He is buried in El Encinal Cemetery in Monterey.) After the ceremony, the mourners walked to the Point Pinos Lighthouse, located on the northern tip of the peninsula.

Dating to 1855,  Point Pinos Lighthouse is the oldest continuously working lighthouse on the West Coast. The building, lenses, and prisms are all original. For Steinbeck’s characters, the lighthouse is a somber, contemplative place. Several walk from Pacific Grove out to the lighthouse, among them the bouncer William in Cannery Row, sad and isolated. Suzy in Sweet Thursday, in love with Doc, “mooned away on the path that leads along the sea to the lighthouse on Point Pinos. She looked in the tide pools, and she picked a bunch of the tiny flowers that grow as close to the ocean as they can.” In Sweet Thursday, Doc, working in his lab, hearing voices of loneliness, “would leave his work and walk out to the lighthouse to watch the white flail of light strike at the horizons.”

Point Pinos Lighthouse is the oldest continuously working lighthouse on the West Coast. The building, lenses, and prisms are all original. For Steinbeck’s characters, the lighthouse is a somber, contemplative place. Several walk from Pacific Grove out to the lighthouse, among them the bouncer William in Cannery Row, sad and isolated. Suzy in Sweet Thursday, in love with Doc, “mooned away on the path that leads along the sea to the lighthouse on Point Pinos. She looked in the tide pools, and she picked a bunch of the tiny flowers that grow as close to the ocean as they can.” In Sweet Thursday, Doc, working in his lab, hearing voices of loneliness, “would leave his work and walk out to the lighthouse to watch the white flail of light strike at the horizons.”

Point Pinos Lighthouse.

On any given summer weekend, a wedding is held at  Lovers Point. And who can blame couples for selecting this lovely spot? Some say it was named for its romantic associations, not for the “Lovers of Jesus” who came for outdoor meetings. At one time there was a Japanese tea garden here, serving cakes and tea. From the beach below, tourists could float in glass-bottom boats and gaze at intertidal life. In the 1930s, these boats were still “well patronized,” noted the WPA guidebook.

Lovers Point. And who can blame couples for selecting this lovely spot? Some say it was named for its romantic associations, not for the “Lovers of Jesus” who came for outdoor meetings. At one time there was a Japanese tea garden here, serving cakes and tea. From the beach below, tourists could float in glass-bottom boats and gaze at intertidal life. In the 1930s, these boats were still “well patronized,” noted the WPA guidebook.

Lovers Point, circa 1915.

The Chinese fishing village in the 1890s.

Today, Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station stands where a Chinese fishing village once tipped toward the sea. Some fifty or sixty Chinese men and women came to this beach in the 1850s to harvest abalone. Later, they bleached and sold sea urchins and caught and dried squid. Drying and shipping squid proved to be the most lucrative enterprise, an industry that netted tidy profits at its height in 1930. During his years on the Peninsula, Wing Chong became the local squid boss, his store a clearinghouse for all local fishermen. Drying squid, however, also created a much-noted unpopular odor. One late-nineteenth-century observer described the Chinese squid boats:

They go out at night and burn fagots attached to the sides of their boats. The squids are attracted by the light, and come to the surface and are fairly ladled up by the fishermen. The catches are brought ashore and skillfully and quickly cleaned and put out in large fields to dry. They are packed down in sacks by tramping them with the bare feet, and shipped to China as delicacies.

“Amazing people, the California Chinese,” Steinbeck wrote after he left the state. Steinbeck’s fictional tribute to the Chinese may be philosophic Lee in East of Eden or savvy Lee Chong in Cannery Row or perhaps the mysterious Chinaman in Cannery Row who shuffles to the sea at dusk, returns at dawn, regular as the tides. The Chinese fishing village figures in several of Steinbeck’s recollections, this one in 1948:

The wind is ashore tonight and I can hear the sea lions and the surf and the whistling buoy and the bell buoy at Point Joe and China Point respectively. China Point is now called Cabrillo Point. Phooey—any fool knows it was China Point until certain foreigners became enamored of our almost nonexistent history.

Cabrillo may or may not have first sighted this point, but them [Chinese] raised hell on it for fifty years, yes, and even buried their people there until the meat fell off and they could ship them cheaper to China. Mary and I used to watch them dig up the skeletons and we stole the punks and paper flowers off the new graves too. I used to like that graveyard. It was so rocky that some of the bodies had to be slipped in almost horizontally under the big rocks.

And, in 1957, writing for the Monterey Peninsula Herald, he noted rather cynically that Cannery Row redevelopment might consider re-creating the “old old” on Cannery Row.

I remember it well, shacks built of scraps of wood, matting, pieces of tin. The district known as Chinatown, a street free of sewage disposal and very romantic. In it the Chinese kept alive the arts of gambling, prostitution, and the opium pipe. I remember the night the whole thing burned to the ground. We felt that a way of life was gone forever. The purchasers [of Cannery Row land] could re-create this pylon of the past with the help of Hollywood scene designers.

On the back of the photo is written, “The Chinese fishermen supplied Monterey with freshly caught fish—delivering them while still flapping in baskets slung over the shoulders with bamboo pole.”

With his lifelong passion for science, it’s not surprising that Steinbeck had a close association with  the Hopkins Marine Station. John and his sister Mary attended summer classes here in 1923, both taking general zoology and English composition. Both Steinbeck and Ricketts knew Hopkins scientists. Director W. K. Fisher let John and Carol park their boat overnight at the “no parking” zone and drop nets for fish.

the Hopkins Marine Station. John and his sister Mary attended summer classes here in 1923, both taking general zoology and English composition. Both Steinbeck and Ricketts knew Hopkins scientists. Director W. K. Fisher let John and Carol park their boat overnight at the “no parking” zone and drop nets for fish.

Hopkins is nearly as old as Stanford University. Timothy Hopkins, treasurer of the Southern Pacific Railroad, was on the Stanford University Board of Trustees. A man of vision and scientific curiosity, he had “visited Dohrn’s Marine Station at Naples,” writes David Starr Jordan, the university’s first president, “and was very much impressed.” Hopkins and Jordan wanted a marine station for the newly formed Stanford University, where students could study marine zoology and botany. A site at Point Aulon—now Lovers Point—and $500 were donated by the Pacific Improvement Company; another $300 was given by the town of Pacific Grove; and an additional $1,000 was donated by Hopkins—who later gave more money for buildings, books, and equipment. The Hopkins Seaside Laboratory of Stanford University opened its doors officially in 1892 with thirteen students: “It proves a perfect paradise for the marine biologist,” wrote a founding professor. Many women came to Hopkins in the early years, schoolteachers whose only avenue to biological study was the marine laboratory.

First marine laboratory, 1890s.

When the station moved to its present location in 1917, the remarkable Dr. W. K. Fisher became director, a post he held for twenty-six years. His ecological, holistic approach to marine biology was progressive, and it was perhaps this quality that drew both Steinbeck and Ricketts to the station and to the man in the 1920s and 1930s. Fisher wrote a statement in 1919 that heralds the station’s ecological interests: “It is within the scope of a marine station to find out everything possible about the animals and plants of the ocean, as well as about the physical characteristics of the ocean itself…. One phase of the instruction at the station will cover the relation of all these facts to the welfare of man.”

Certainly this would be the direction that Steinbeck’s and Ricketts’s ecological and holistic thought turned in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1919, Fisher suggested that the sardine population “bears a very definite relation” to plankton levels—another insight that would take decades for scientists and fishermen to fully appreciate. The Monterey Bay sardine, caught directly in front of the station, engaged Hopkins scientists who conducted a “little known research project,” a local paper reported, and concluded in 1941 that sardines in the bay were decreasing in size.

In 1945, Steinbeck struck a deal with Hopkins, and in August, McIntosh & Otis drafted an agreement: John would donate $6,000-$9,000 for a proposed John Steinbeck Aquarium, provided that Hopkins would lease Ricketts, for one dollar a year, about a third of an acre for a new lab. The aquarium, Steinbeck wrote, would be “largely for scientific purposes (research and teaching) and secondarily for public attendance.” Director Lawrence Blinks loved the idea, as did, apparently, Stanford University. Blinks wrote the president, “Quite aside from the aquarium aspect, Ricketts is a good scientific worker and his expeditions with Steinbeck will probably yield many valuable specimens for the Marine Station, so the tie-up would be desirable in any case.” To fund his part of the deal, Ricketts had to sell his Cannery Row lab for at least $18,000 to finance the new lab building; apparently the cannery that had offered to buy his lab, acknowledging the end of sardine runs, backed out of the deal. The John Steinbeck Aquarium never came to be.

Sea otter mural, Pacific Grove bike trail.

For almost a century, the southern sea otter, slaughtered for its thick fur, was thought to be extinct. But in March 1938, a small herd, heretofore known only to locals, was reported in a Big Sur cove. Scientists at Hopkins Marine Station told local papers that only two other herds of sea otters were known to exist at that time: one in the Aleutians and one under Japanese protection in the Kurile Islands.

Due to the remote location of the Big Sur coast, a few otters managed to survive centuries of slaughter—living on the fringe in a de facto refuge. Protected today by the Endangered Species Act, the otter population has recovered, and the plump creatures can readily be seen floating, bellies to the sky, as they crack shellfish, urchins, and abalone along the peninsula shoreline.

Today, in an era of genetic research, the Hopkins Marine Station still funds holistic investigations into tuna and squid as well as interconnections among pelagic creatures and their environment, carrying on the work of Fisher and many other dedicated scientists.