MERRIVALE Alt Names: The Plague Market, The Potato Market

Megalithic Complex | Nearest Village: Princetown

Map: SX 5548 7477 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.55477N | Long: 4.0415W

Sandy Gerrard, archaeologist and author of the English Heritage Book of Dartmoor

It is currently thought there are around 295 surviving prehistoric stone rows in Britain, with at least a further 30 known from documentary sources but now completely destroyed. The densest concentration of rows is on Dartmoor, where about 86 have been identified, the shortest (currently thought to be Merrivale’s Row 4, see page 63) measuring a mere 2.97m (9ft 9in), while the longest, Upper Erme (see page 56), extends for 3,386m (just over 2 miles).

Stone rows are notoriously difficult to date. Radiocarbon-dating of a stone in the row at Cut Hill indicates that it had perhaps been erected and toppled some time before 2360BC. This date is consistent with field evidence elsewhere on the moor demonstrating that the rows at Assycombe, Hook Lake, Hurston Ridge, Leeden Tor, Yar Tor and at least one of the rows at Shovel Down are all earlier than middle Bronze Age fields and enclosures that partly overlie them.

The form of these rows varies considerably and their identification is often complicated by their similarity to field boundaries, natural outcrops or lines of stones raised in historic times. Some include only three stones, while others are formed by hundreds. Some are exclusively large uprights, others a mixture of stone sizes, and still others very small stones that barely protrude through the turf. All the long rows (more than 200m/650ft long) are sinuous in form and even some of the shorter rows are far from straight. The spacing of stones varies considerably, though this may sometimes be a result of later damage, and there is no dominant orientation or altitude.

The purpose of stone rows remains enigmatic. Many, as at Merrivale, are directly associated with funerary monuments, which implies they may have been the focus for ritual activity. The evidence suggests that the rows are earlier than the terminal cairns; the upper end of Merrivale’s Row 3, for example, is incorporated into a later cairn. The fact that so many cairns are not in perfect alignment with the rows may also indicate that they are not precisely contemporary with each other and were generally built in two stages.

Recent work has indicated that many rows were carefully positioned to provide particular definable visual links with the landscape. Various features in the surrounding hillsides may have been significant to the builders of Conies Down row, for example. If you walk south down the row, the five distinct tors visible on the horizon to the southwest are hidden one by one, with Great Mis Tor only disappearing as the end of the row is reached. Observations about the rows’ placement in the landscape, as well as their positioning in relation to contemporary routes (as at Lakehead Hill), may provide vital clues to their purpose.

If we accept that the reason why so many stone rows have survived on Dartmoor is because of the difficult terrain here, then we must also conclude that there were originally thousands throughout Britain and we are left with just a tiny fraction. Certainly the rows of smaller stones would not have survived in areas that were more intensively farmed.

Find out more about stone rows at: stonerows.wordpress.com

MERRIVALE Alt Names: The Plague Market, The Potato Market

Megalithic Complex | Nearest Village: Princetown

Map: SX 5548 7477 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.55477N | Long: 4.0415W

In a stunning setting above the River Walkham, Merrivale lives up to its name (“pleasant valley”), and, for Dartmoor, is pretty accessible. This complex prehistoric landscape, includes multiple stone rows, a stone circle, a large standing stone, many burial cairns and cists, and a prehistoric settlement. It’s also known as the Plague Market, this name deriving from the story that provisions were left here for the people of Tavistock when the town was isolated during an outbreak of plague in 1625. If you park by the B3357 and walk up, you’ll pass through part of the Bronze Age settlement (there are more huts on the other side of the road). There are around 36 huts altogether, and the settlement is thought to have been in use for some 1,500 years. There is also evidence of medieval and post-medieval activity here, such as a large, flat apple-crusher stone, used in cider-making.

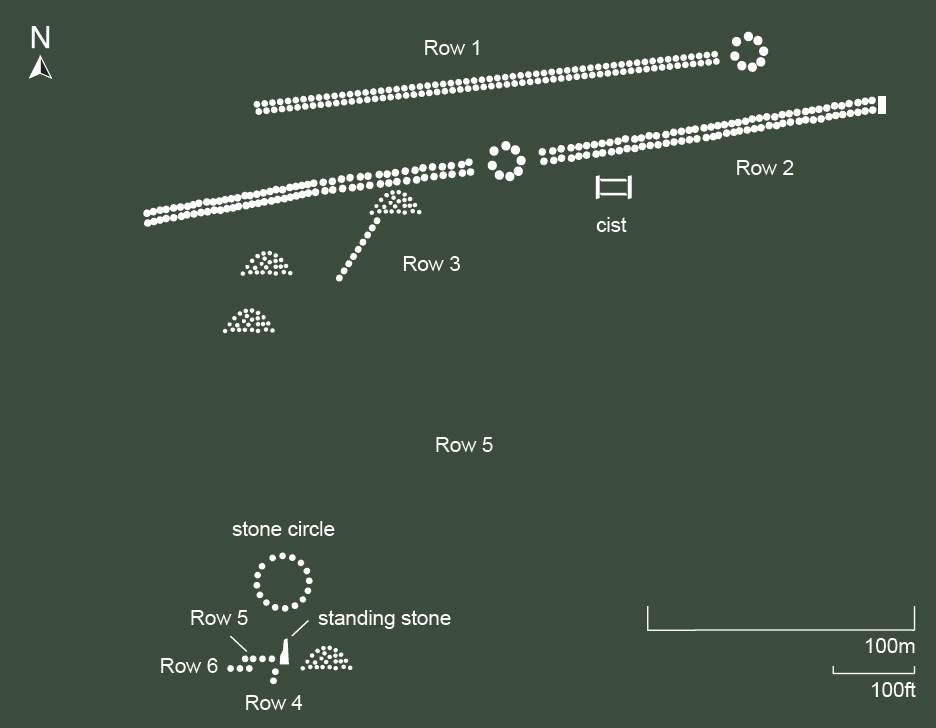

Rows 1 and 2, the two double stone rows, march roughly east to west across the moor and are almost parallel, about 25m (82ft) apart. A 19th-century leat (artificial stream) separates them. Row 1 is now 183m (600ft) long and probably once extended further to the west. There is a blocking stone at its eastern end, as well as the remains of a kerbed cairn. Row 2 is a fine 263.5m (863ft) double row, with blocking stones at both ends; the large, triangular one to the east is particularly impressive. There is a kerbed cairn at its centre, built on top of the row. A fine cist (pictured, left) lies just south of Row 2, close to a single stone row (Row 3) that ends in a small cairn. The terminal slab of the row is set within the south side of the cairn, indicating that the row predates the cairn. This row extends for at least 60m (196ft).

At SX 5535 7463, south of Row 3, is a stone circle with 11 stones no more than 0.5m (1½ft) tall.

At SX 5536 7459, 42m (137ft) SSE of the circle, is a tall, slender stone, 3m (10ft) high. About 10m (33ft) to the east is a fallen slab, 2m (6½ft) in length, which may have been a companion, although there is no evidence it originally stood. Erected in 1895, it fell over not long after.

These are all short rows close to the standing stone. The stones are generally quite small and therefore it can be hard to figure out exactly what’s going on. Row 4 is south of the standing stone and runs northeast–southwest. There are four small stones. Row 5 is west of the standing stone and in line with it, running east–west, so the standing stone appears at the eastern end of the row. There are six stones of various sizes in a 7m (23ft) alignment. Row 6 is south of Row 5 and runs east–west, heading further west than Row 5.

Stone Circle | Nearest Village: Peter Tavy

Map: SX 5563 7822 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.58581N | Long: 4.04072W

Splendidly situated high above the Walkham valley, this circle would once have been an imposing sight on the skyline, but most of the stones were destroyed when they were used for target practice during World War II. The circle is still worth visiting for the views in all directions (including, to the south, to Merrivale). It is in the Merrivale live firing range, so check range opening times beforehand.

Standing Stone | Nearest Village: Peter Tavy

Map: SX 5502 7874 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.59033N | Long: 4.04953W

Peppered with bullet holes during target practice in World War II, this stone has a distinctive lightning-strike shape. It is in the Merrivale live firing range, so check range opening times beforehand. Beware of attempting a direct route from here to the Langstone Moor circle, as a nasty mire lies in between.

Nearby | At SX 5424 7867, 780m (just under ½ mile) west of the Langstone, on top of White Tor, is a fortified enclosure with cairns, huts and other structures dating back to the Neolithic.

Prehistoric Settlement | Nearest Village: Widecombe-in-the-Moor

Map: SX 7007 8090 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.6133N | Long: 3.8378W

Viewed from Hookney Tor or Hameldown, Grimspound is an impressive sight on the moor, enclosed by a wall that averages 3m (10ft) in width. This is an accessible and fascinating Bronze Age settlement with 24 hut circles within the walls, and at least nine more outside, to the southeast. In the southeast there’s a dramatic entrance, with a 2m (6½ft) wide paved passage running between walls that at this point are over 2m (6½ft) high. Excavation here in 1894 unearthed hearths, benches, pottery, cooking stones and other items that evoke the day-to-day experience of domestic life several millennia ago. It’s been suggested that the name Grimspound relates, as with other sites (such as Grim’s Dyke), to the god Woden, but it seems this place name was recorded for the first time in 1797. Some of the reconstruction that took place here in the 1890s is now thought to be inauthentic.

Nearby | At SX 6898 8082, around 1km (0.6 miles) west of Grimspound, Challacombe is an unusual triple stone row, badly damaged at its northern end by tin-mining activity in Chaw Gully. The row has been restored and now stretches for some 160m (528ft). The three rows draw closer together at the southern, uphill end, where there is a large blocking stone. In local legend, Chaw Gully is a dangerous place inhabited by malevolent spirits, where rumours of buried gold have led many greedy treasure hunters to their doom.

Stone Rows | Nearest Village: Postbridge

Map: SX 6726 8244 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.62714N | Long: 3.8775W

A rarity for Dartmoor, as this double row is likely to be complete and undamaged, with all 99 stones in 49 pairs (plus one blocking stone) still in place. It’s set in a great location with wonderful views north and east. The rows run from a ruined cairn (where the Hurston Ridge urn was found in 1900) down the ridge for about 150m (492ft) NNE. The end stone of the east row is almost 2m (6½ft) tall, and can be seen for miles around. Many of the pairs are opposing slabs and pillars. A Bronze Age enclosure wall cuts through the avenue about two-thirds of the way down.

“A middle Bronze Age enclosure was built across the row, presumably after it was abandoned. The large recumbent stones form part of the enclosure boundary. Note that these are bigger than the stones used to build the row.” Sandy Gerrard

Stone Circles | Nearest Village: Postbridge

Map: SX 6387 8313 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.63192N | Long: 3.9262W

Climb Sittaford Tor for tremendous views of these two beautiful circles, and look out for skylarks. The circles were restored by Rev Sabine Baring-Gould (who wrote “Onward Christian Soldiers”) in 1909, following excavation toward the end of the 19th century, when a layer of charcoal was discovered to cover the original ground surface. Both circles, one positioned almost due north of the other, are about 33m (108ft) in diameter, and would have consisted of 30 stones; today the southern circle has 29 stones, the northern one 20 stones. You can park at Fernworthy Reservoir and walk through the forest, taking in Fernworthy stone circle before turning left on to moorland to find the Grey Wethers. It’s a long, often wet walk that offers great rewards.

“One of the more common legends (told to me by my father) about Grey Wethers is that the stones were once sold to a drunk farmer as a well-behaved flock of sheep!” Matt Impey

FERNWORTHY Alt Name: Froggymead

Megalithic Complex | Nearest Town: Chagford

Map: SX 6548 8410 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.64101N | Long: 3.9038W

At Fernworthy you’ll find a stone circle and several stone rows with terminal cairns. The setting in a modern plantation clearing is atmospheric but can be very wet and boggy, justifying the site’s alternative name of Froggymead.

Photographs from before the trees were planted show that Fernworthy, like the Grey Wethers, once stood in an open landscape. There are 29 stones in the 19m (62ft) circle (slightly flattened in the north), 26 of which are standing. The largest is about 1.2m (4ft) high. As at Grey Wethers, excavation found charcoal all over the interior of the circle. Several cairns surround the circle, including one some 73m (240ft) to its east, visible as a low mound and originally surrounded by a stone circle, of which only three stones remain. Excavated in 1898, it contained a central pit packed with stones and a bronze spearhead or knife, a flint knife, a button, and a Beaker-type food vessel.

A double row of charmingly petite stones starts 140m (460ft) north of the circle, extending for 101m (331ft) and ending at a cairn (at SX 6554 8433) with a cist and a large stone. Much of the row has been destroyed by tree planting. South of the stone circle are two badly damaged double rows. The southwest row is the better preserved, with a cairn toward the northern end (at SX 6547 8410). The small stones of the southeast row are hard to see among the tree stumps. There’s a terminal cairn at its northern end (at SX 6549 8409).

Nearby | At SX 6690 8400, on the edge of the Fernworthy Reservoir, is Metherall prehistoric settlement, where hut circles and enclosure walls can be seen. Four of the eight huts are now usually underwater but can be seen when the reservoir level falls during prolonged dry weather.

Stone Circle | Nearest Village: Postbridge

Map: SX 6301 8281 | Sheets: OL28 L191 | Lat: 50.62884N | Long: 3.93823W

The first stone circle to be found on the high moor in more than 100 years, Sittaford was discovered by Alan Endacott in 2007. It’s about 300m (985ft) SW of Sittaford Tor, north of the reave which runs along the summit ridge. Follow this wall, and look out for the standing stone built into it; probably originally an outlier for the circle. There are 30 fallen stones in a 30m (98ft) circle. Be aware that it’s always extremely wet and boggy up here, even after weeks of fine weather.

Stone Row | Nearest Village: Postbridge

Map: SX 5992 8275 | Sheets: OL28 L202 | Lat: 50.62757N | Long: 3.98187W

It is hard to get to this fallen stone row, discovered in 2004 by Tom Greeves on Cut Hill, one of the highest and most isolated parts of Dartmoor. Nine fallen stones have been found, some exposed by peat cutting and others still buried. Carbon-dating of peat suggests that at least one of the stones had fallen (or been placed flat) by 3350– 3100BC an earlier date than had previously been suggested for stone rows. The regular placement of the fallen stones, which Greeves compared to railway sleepers, may indicate that they were placed that way, even if at some point they had been standing (as is indicated by packing stones found at the end of at least one stone). Be prepared for a walk of about two hours, whichever direction you approach from.