In this chapter, we focus on judicial recess appointments in the modern era. We noted in Chapter Two that the unavailability of data back to the beginning of the Republic make it impossible to include ideological distance measures between the president and Senate, public approval scores, and other useful factors in a study. The difficulty of disaggregating appointment data over such a lengthy period also limited our analysis. Closer study of judicial recess appointments confined to the modern era could take into account these additional factors and possibly find other ways in which the exercise of unilateral presidential power has been complicated since the institutionalization of the American presidency.

By focusing on modern appointments, we are able to use contemporary measures of ideology and determine how significant ideological compatibility between the president and Senate is to the recess appointment process. Similar to Chapter Two, we explore under what political and institutional circumstances a president is likely to make a judicial recess appointment and our analysis confirms much of what we learned in Chapter Two.

Earlier we noted significant differences in the use of judicial recess appointments between older and modern eras. In the early days of the Republic through the nineteenth century, president’s used the judicial recess appointment power primarily for efficiency reasons. Poor communications and travel and long congressional recesses dictated the need for action by the executive to keep the operations of government going. The judiciary for much of the nineteenth century was severely hampered by shortages and this was especially acute as the size of the nation grew rapidly (Wheeler and Harrison 2005). Thus the use of the recess power to fill vacancies was a commonsensical and presumably non-controversial, non-strategic approach to governing.

In the modern era, judicial recess appointments are different and while conventional wisdom holds that a politically weak president is more likely to use the recess power to avoid the necessity of Senate approval, we again find to the contrary in the modern era. We argue that politically strong presidents are more likely than weaker presidents to make judicial recess appointments. Our ideological measures from this analysis support the conclusions from the partisan strength measures in the earlier chapter. In a Separation of Powers system the recess appointment power allows a president to move the judiciary ideologically closer to his preferences, but this opportunity carries risks that legislative support can relieve. To demonstrate this, we assess the literature on judicial appointments and judicial recess appointments. Next we offer a brief review of previous scholarship of presidential power. Then we present our data, methodology, and results of our study. Finally we offer our conclusions and suggestions for future research.

For the current chapter, we designate the modern era a bit differently than in Chapter Two, wherein we dated it from the beginning of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency. Here, we begin with the advent of the presidency of Harry S. Truman. We do so because only from this point forward do we have cardinal measures of ideology—the Common Space scores. Our dataset uses all appellate court judicial nominations from 1945 through 2006 and includes 17 recess appointees. We model the likelihood of a recess appointment measured as the time until a judicial vacancy is filled with a judicial recess appointment. In this manner, we show what factors lead to a decrease in time before a recess appointment and what circumstances lead to longer durations to a recess appointment.

As previously noted, recess appointments have become the focus of contention and negotiation between presidents and the Senate. Following several non-judicial uses of the recess appointment by President Ronald Reagan, including one to the independent Federal Reserve Board of Governors, then-Senate Minority Leader Robert Byrd placed a hold on seventy other pending nominations, “touching virtually every area of the executive branch,” according to the White House, as well as including federal judges (Fisher 2001, 11). Reagan’s standoff with Byrd ended with the development of procedures for recess appointments, including notice prior to the beginning of the recess. Violation of this agreement became one of the issues surrounding President Clinton’s controversial recess appointment of Roger Gregory to a seat on the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals. After the Democrats regained control of the Senate in the 1986 election, Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole (R-KS), a potential candidate for the presidency, raised the possibility of giving a recess appointment to Robert Bork in response to delay in Bork’s confirmation hearings, a suggestion dismissed by a Senate Democrat as “playing politics” (Walsh 1987).

While there is a relationship to population growth and the expansion of the judiciary (Wheeler and Harrison 2005) scholars have begun to find that partisanship and partisan alignments can both trigger and deter needed growth of federal judicial positions (de Figueiredo et al. 2001; de Figueiredo and Tiller 1996). Judicial growth is much more likely under unified government (de Figueiredo and Tiller 1996) than under divided government. Politics and partisanship dominated decision to create judicial positions. Presidents and home state senators nominate judges to lower federal court positions because the nominee shares the party preferences of the nominating president and senator. If judicial expansion occurs it means that whoever is president will get to nominate several judges to lifetime positions and those judges are likely to have the same ideological preferences as the president.

For example, a bill with bipartisan sponsorship introduced in the Senate in 2008 calls for the creation of fifty additions to the Court of Appeals and District Courts (Leahy Senate press release 2008). Twelve new Courts of Appeals positions would be created and 38 Federal District Court judgeships will also come into being. Undoubtedly Senators Hatch and Leahy both sponsored the bill assuming that their preferred presidential candidate would win, thereby hoping to fill fifty conservative or fifty liberal positions.

Because of this, a Congress with one or more branches in control of the opposition party is far less likely to approve new judicial seats than under unified government. Conversely, a unified government will be far more inclined to create new judicial seats in order to achieve some ideological control over federal judicial rulings.

If Congress does create new judicial seats, then recess appointments can be particularly appealing to the president. As noted, a recess appointment to an Article III court allows the president to fill a vacancy with a favored candidate quickly, without the obstruction or rejection the confirmation process might produce. Such appointments are temporary, but an intrasession recess commission can last for nearly two years, if the recess falls early in the congressional session (Carrier 1994). This allows the president to appoint an ideologically compatible judge to serve on an Article III court producing rulings that the president favors for a significant period of time. Of course the president always has to be careful in the use of the recess appointment. As Gerhardt notes, “senators have invariably used their other powers, particularly oversight and appropriations, to put pressure on those choices” (2000, 174). Furthermore, the ability of a president to extend his influence beyond his terms of office by reshaping the federal judiciary through life-term appointments is not served, and may be frustrated, by the injudicious use of unilateral authority like the recess appointment power.

Strong presidents, those with strong partisan or ideologically compatible majorities in the Senate are well equipped to use the recess power and this power should also be used when there are new judicial seats to fill. Those are the presidents who can weather the controversy and potential harmful tactics of the Senate upset by intrusions on its institutional power and domain. Conversely weaker presidents would have to use such power sparingly and be more aware of intruding on Senate prerogatives. Thus a president with a Senate controlled by the opposition, or one with low approval or one in the fourth year of office, traditional measures of a constrained presidency (Segal, Timpone, and Howard 2000), might find it very difficult to justify or contemplate any sort of strategic use of the judicial recess power.

All of this leads us to believe that strong presidents and presidents with newly created, vacant judicial positions are going to be the most likely to use the recess power. In the next section we offer our data, models used and analysis.

Our interests lie in the likelihood of a specific appellate judicial vacancy being filled by a recess appointment and the political, institutional, and temporal factors affecting that likelihood. We restrict our present analysis to the post-war period for several reasons. First, although there had been circuit courts and appellate judges previously, the modern U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals took shape only after the Act of 1891 drafted for that purpose. Also, our previous analysis indicates that the factors influencing use of recess appointments have different effects in the years before the onset of the “modern” presidency and afterward. Thus, any conclusions drawn from analyzing vacancies before the modern era may not be generalizable to the subsequent period. Accurate data on vacancies and appointments in the modern era are also considerably more accessible. Ideology scores for the president and the Senate and public approval data on the president’s performance, of which we make use in our analysis, are only available for the modern era.

The term of the study for our analysis extends from the beginning of the Truman administration in 1945 to the end of the 109th Congress in the first days of 2007. During this period, seventeen judges were appointed by the president during Senate recesses to fill vacancies on the Circuit Courts of Appeals. We make use of the rich and extensive data available in the Multi-User Database on the Attributes of U.S. Appeals Court Judges, often referred to as the “Auburn” database. This database, as updated, provides background information about every judge serving on the courts of appeals from 1801 to 2000. For our purposes, the data also report characteristics of the seats and vacancies on the Circuit Courts of Appeal. We also coded data on Senate recesses and political control, much of it used in previous chapters, as well. Because our term of study is confined to recent decades, we can make use of the Basic Space preference scores described previously in Chapter Four that place federal government actors in ideological space comparable across institutions and time (Poole 1998). Thus, changes in the ideological distances between actors across time are reflective of genuine changes in relative ideological positions. Finally, we collected data on the collective yearly caseload of the circuit courts from reports of the Administrative Office of the Courts.

Several methods could be used to analyze presidents’ decisions to fill existing judicial vacancies with recess appointees. We could treat each vacancy as an observation to be filled either by the conventional nomination and confirmation process or by recess appointment (Corley 2006). However, this approach neglects the effect that varying circumstances can have on the incidence of recess appointments. Conditions that make recess appointments unlikely at the time a vacancy is created could change as the vacancy persists. Another approach would be to follow the strategy used in chapter 2, examining the number of recess appointments made in a given year. This approach served well for our analysis of the full history of judicial appointments, but limiting our study to the modern era as we do in this chapter permits a more nuanced investigation of the qualities of individual vacancies and their effects on incidences of recess appointment.

The approach we take accounts for both the incidence and timing of recess appointments to court of appeals vacancies. Our data disaggregates judicial vacancies to days vacant so that we can assess the impact of varying conditions on a president’s decision to fill a judicial position during a Senate recess. We estimate an event history model, which considers the timing of events as well as their occurrence. Event history models are often referred to as “duration”, “survival” or “hazard” models, depending on the interest of the researcher. Such models have been used in political science for some time now to study subjects as wide-ranging as policy diffusion (Berry and Berry 1990; Volden 2006), government duration (King, Alt, Burns, and Laver 1990; Strøm and Swindle 2002), democratization (Hannan and Carroll 1981; Lai and Melkonian-Hoover 2005), and international conflict (Bennett and Stam 1996; Regan 2002). Event history methods have been applied to various questions in judicial politics, including legal change (Benesh and Reddick 2002; Spriggs and Hansford 2002), judicial confirmation (Binder and Maltzman 2002; Shipan and Shannon 2003), and retirement (Zorn and Van Winkle 2000).

Applications of event history analysis typically model the “hazard rate” of a unit of analysis over a period of observation. The hazard rate can be conceived of as the “risk” or likelihood that a given unit of analysis experiences an event in a particular interval of time given that the event has not occurred at the beginning of that interval (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). We are interested in the risk that a judicial vacancy will be filled via recess appointment conditional on the fact that it has not previously been filled by Senate confirmation of a nominee. Event history analysis assumes that during the time intervals being studied, the units are “at risk” of experiencing the event. At the beginning of the observation period, a unit must be within the “risk set”—units eligible to experience the event—and when the event can no longer occur, the unit exits the risk set.

To conduct proper event history analysis of judicial recesses, we must structure our data in order to study judicial vacancies only when the likelihood of a judicial recess appointment taking place is greater than zero. The risk of a judicial recess appointment when the Senate is in session, for instance, is zero. Individual judicial vacancies also exit the risk set when the vacancy is filled otherwise. Thus, our data consist of every day in which a judicial vacancy existed and the Senate was in recess during our term of study from 1945 to 2007. The resulting dataset consists of 475 judicial vacancies observed over a total of 79,739 vacancy-recess days.

We model variation in the hazard rate from one vacancy-recess day to another as a function of covariates. Factors or conditions that we hypothesize will make recess appointments more likely will cause the hazard rate to increase, while factors or conditions that we expect to deter use of recess appointments will lead to a decline in the hazard rate. Our covariates reflect the hypotheses specified in the previous section. The independent variables in the duration model can be divided into characteristics of the Senate recesses, the judicial vacancies, and the political-institutional context of a given vacancy-recess day. They can also be characterized as a class of fairly constant circumstances or qualities and temporal qualities, or indicators of “political time.”

Several covariates are qualities of the Senate recesses within which individual vacancy-recess days fall. We include a variable indicating whether a particular recess occurred intrasession. Another covariate measures the length of the instant recess. Finally, we coded a variable that measures the number of days from the vacancy-recess day in question to the end of the next congressional session, similar to the variable we used in Chapter Two as a measure of how long a temporary commission issued during the current recess would last. Because the unit of analysis for this model is the recess day, rather than the recess, this covariate decreases by one with every subsequent day within a Senate recess. The first two of these variables are comparatively constant qualities, while the third measures a particular, institutionally relevant understanding of time.

The next group of covariates for the duration model reflects features of the judicial vacancies, the actual units of our analysis. We code an indicator distinguishing judicial vacancies newly created by legislation from those that result from a judge vacating a previously existing seat. Another variable counts the length of the spell, or the number of recess days elapsed since the vacancy occurred. This variable serves to capture a form of “duration dependence,” indicating how much time the Senate has spent in recess while the vacancy goes unfilled. Another form of time dependence is reflected in the next variable, which measures the number of days for each observation until Senate confirmation. For vacancies that are not filled by recess appointment, this is the number of days remaining until the vacancy is filled, but for seats filled by recess appointment, this quantity is the number of days until the vacancy is filled added to the number of days from the recess appointment to the day a nominee is confirmed permanently to the seat. The difference between the two measures the gain in days a recess appointee would be active on the bench over the conventional confirmation process. The first of these variables is constant across a vacancy spell, while the other two are, of course, time-varying.

The remaining variables capture political and institutional circumstances that are qualities of neither the Senate recesses or of the specific vacancies that constitute our data. The first of these is a measure of the executive activity of the president in office at the time. We use the same measure for this that we used in our complete history analysis in Chapter Two, the number of executive orders issued by the president during the current term. Although this quantity will change slowly, a number of vacancies span more than one presidential administration, even across different presidencies. We also include a measure of the public’s approval of the president’s performance in office, produced from the Gallup survey data made available by the Roper Center and transformed into a monthly series using the dyad ratios algorithm developed by James Stimson (1999). This algorithm produces a measure of the covariance of different series of data from survey marginals, recursively averaging ratios of different series of survey responses as indicators of the same underlying concept and placing the aggregate measures on a common metric.

Three more variables are included to capture conditions not specific to the vacancy or the recess. We coded a variable measuring the absolute distance between the Common Space ideology scores of the current president and the median of the Senate. This variable reflects the policy division between the president and Senate with more accuracy than the proportion of Senators of the president’s party, given the heterogeneity of American political parties and especially the divisions over judicial nominations within parties that have arisen in decades past. The yearly circuit caseload variable, the number of appeals filed per year as reported by the Administrative Office of the Courts, is also included. Finally, the event history model has a time counter indicating the number of days from the beginning of our period of observation, roughly the beginning of the Truman administration. This variable measures the passage of time, rather than the duration of a spell or time until some point. Thus, it will capture any secular trend in the incidence of recess appointments over the course of the six decades of our study.

A complication of the event history approach is that standard models of this type assume that all observations in the dataset will eventually experience the event, even if the period of study does not last long enough to observe it. For our purposes, this means that every vacancy will eventually be filled by a recess appointment. Obviously, this is an unreasonable assumption. In fact, the duration of a judicial vacancy is a result of two processes, the conventional confirmation process and the president’s choice to fill the seat via recess appointment. Either of these processes can end the vacancy. Failure to take into account the fact that most vacancies are not filled by recess appointment can introduce heterogeneity into the model and lead to incorrect estimates of the influence of the covariates on the phenomenon.

One way to address this problem is to model the observed duration as a result of two separate processes, the recess-vacancy duration and the exit of spells from the risk set by Senate confirmation. As constituted, the duration is equal to the number of days that the vacancy persists and the Senate is in recess. While the vacancy is potentially eligible to be filled by recess appointment on those days, it is not simultaneously at risk of being filled by confirmation on those days. Rather, confirmation ends the spell, but occurs during the “gap time” between recesses. Our solution is to model the observed duration to recess appointments conditional on the probability that the vacancy does not exit the risk set—is not filled—by confirmation before that day.

The “split-population” or “cure” model relaxes the assumption that all observations will eventually observe the event. The set of observations are a combination of two “populations”: those that eventually experience the event and those which do not (these observations are referred to as “cured,” reflecting the root of models such as this in biostatistics). The split-population model mixes the unconditional density of the hazard function with the probability that the unit is among the observations that will experience the event. This probability is typically estimated as a function of covariates using a standard dichotomous dependent variable model such as logit or probit.

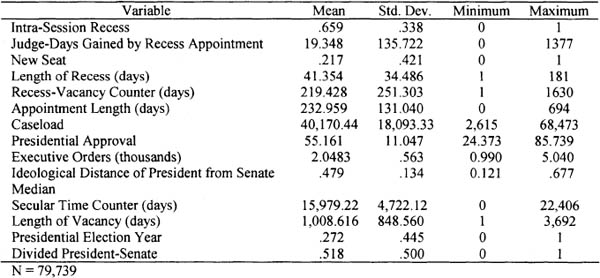

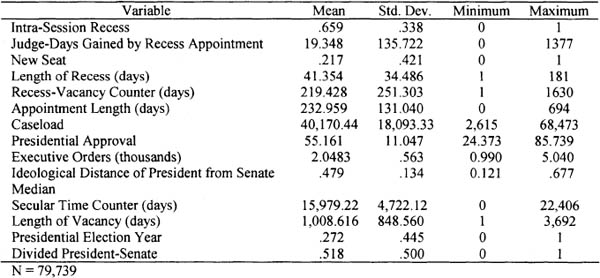

Following this estimation strategy, we specify a split population duration model with the duration equation specified as above and a probit model predicting the likelihood that the vacancy will be filled by Senate confirmation without a recess appointment. The variables in this equation are the overall length of the vacancy in days, the indicator variable of whether the seat is a newly created vacancy, indicators of whether the vacancy is created in a presidential election year and whether the vacancy occurs during divided party control of the Senate and president, and the caseload variable. Descriptive statistics for our data are presented in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1: Descriptive Statistics

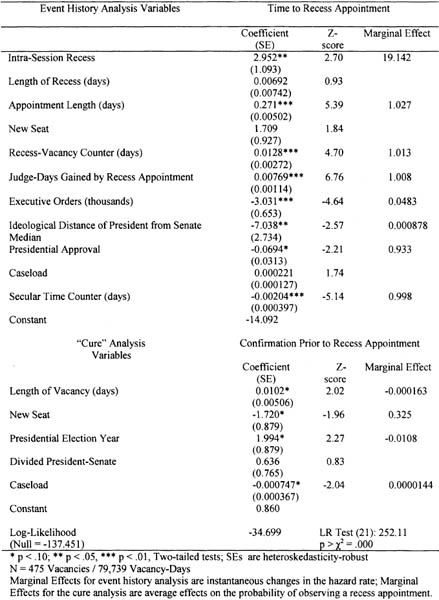

The results of the split-population event history model are reported in Table 5.2. The fully specified model improves the log-likelihood substantially over the null, which results in a very significant likelihood-ratio test and indicates a very good fit to the data. Considering the event history model first, we find many of our covariates to have statistically significant effects on the hazard rate. Positive coefficients reflect increases in the hazard rate, or a greater likelihood of observing a recess appointment, while negative coefficients indicate decreasing likelihood.

We find that intrasession recesses lead to a greater likelihood of a recess appointment in the modern era. Despite the widely held principle that appointments during the typically brief recesses taken within sessions of the Senate are disfavored and should be rare, presidents have been more likely to make such appointments since the end of World War II. This perhaps should not be surprising, since intrasession recesses can last considerably longer than those made after the sine die adjournment of the Senate. Intrasession recess appointments made shortly after the beginning of a session can last nearly two years, giving the appointee considerable time on the bench to conduct work and receive confirmation by the full Senate.

Consistent with this finding and our analysis from chapter 2, the length of time a recess commission would last is directly related to the likelihood of a recess appointment. The indicator variable for seats newly created by Congress approaches statistical significance and is positive. The counter of recess-vacancy days is positive and significant, indicating positive duration dependence. The more days the Senate spends in recess without acting on whatever nomination may be pending for a judicial vacancy, the greater the likelihood that the president will act to fill the vacancy unilaterally. Similarly, the difference in days between the confirmation date filling a vacancy permanently and the current day is positively related to recess appointments. Taking this quantity as an indication of the president’s expectations of delay, this suggests that presidents are responsive to perceived gridlock.

Several of our results illustrate the complicated relationship between the president and the Senate with regard to recess appointments. Our finding from chapter 2, that “assertive” presidents as measured by the number of executive orders issued are less likely to make recess appointments in the modern era. Judged by its marginal effect, this variable has a pronounced impact on the hazard, decreasing the hazard rate to 5 percent of its baseline value for every increase of one thousand executive orders. We also discover that the ideological distance of the president from the Senate median, a measure of the president’s shared policy preferences with the chamber, is negatively related to recess appointments. This finding also supports conclusions drawn in chapter 2 that in the modern era Senate party strength is positively related to recess appointments. Contrary to the conventional wisdom that recess appointments are a tool primarily used by presidents without political support in the Senate, presidents with such support are more likely to use recess appointments to fill judicial seats. This suggests that it is minority obstruction, rather than majority opposition, that presidents are overcoming when they bypass the Senate confirmation process. Adding another dimension to this finding, we learn that presidential approval ratings of the public are negatively related to incidents of judicial recess appointment. Lastly, the secular time counter is negative, capturing the easily observable decline in recess appointments to the courts over our period of observation.

Table 5.2: Split-Population Model of Days to Recess Appointment

Turning our attention to the “cure” equation in the model, we observe that most of the variables in the specification are significant and in anticipated directions. The length of a vacancy is positively related to vacancies experiencing the “cure” of Senate confirmation. At least in the modern era, it appears, protracted vacancies are generally resolved not by unilateral action, but by eventual Senate action, despite recent high-profile counterexamples. Perhaps the most interesting finding in this set of covariates, newly created vacancies are substantially less likely to be terminated by Senate confirmation than those in pre-existing judicial seats. This finding suggests that for much of the modern era, judicial recess appointments are a collaborative endeavor between the Senate and the president, rather than a conflictual one. Bearing out conventional wisdom, the Senate is significantly less likely to fill vacancies during presidential election years than otherwise. Finally, we find that caseload significantly decreases the likelihood of a seat being filled by Senate confirmation. Caseload was positively related to recess appointment in the duration equation, but not significant. From this we might infer that as Hamilton suggested in the Federalist Papers, the executive is more responsive to concerns for the efficiency of government than is the legislature.

As noted in the beginning of this chapter, our findings here confirm much of our historical analysis from chapter 2. Here we focused solely on the modern presidents and their appointments and added measures of ideology and measures of judicial vacancy and whether or not legislation created new judicial positions. We also included some additional measures of presidential strength and constraint. Our event history analysis finds that strong presidents are more likely to use the recess power than a constrained weak president. In addition, the creation of new judicial seats will lead to the use of the recess power.

Our results again suggest that contemporary use of the recess appointment power to fill federal judicial seats should be greeted with skepticism. modern presidents make recess appointments in an opportunistic fashion, combined with the legal and political controversy surrounding them, we believe that judicial recess appointments are unjustified. It also leads us to suggest that when resolutions are introduced to increase the size of the judiciary, however pressing the need, from a purely partisan and ideological viewpoint the opposition party is justified in viewing such legislation skeptically. The increase in the judiciary also means a greater likelihood of judicial recess appointment. That is especially so given the power position the president is likely to be in if such legislation passes Congress.