Smith's Wealth of Nations was part of a much broader inquiry into the foundations of society. It was inseparable from moral philosophy from the project of seeking to find a basis on which people could live together when the Church no longer provided an unquestioned set of answers to questions about how society should be organized. Smith's economics should therefore be seen as a response to Mandeville, and before him Hobbes, as much as to the Physiocrats or the mercantilist writers. In the half-century or so after Smith's death, however, political economy, though dominated by the framework set out in the Wealth of Nations, became independent of moral philosophy. It acquired a more ‘scientific' character that appealed to a class of radicals, many of whom wanted to explain social phenomena without reference to a deity.

To understand this transition, it is important to remember that the discipline was thoroughly involved with politics, and that the political context changed dramatically during this period. Among the political-economic issues facing Smith were the relationship between Britain and the American colonies (especially trade and tax policies), restrictions on both domestic and foreign trade caused by the creation of monopolies, and the appropriateness of intervention in the market for food in order to prevent famine. In the 1780s and 1790s, as the growth rate of the population increased, the problem of poverty and its alleviation increased, with the phrase ‘the labouring poor' coming into widespread use to describe a supposedly new category of workers who were unable to achieve a decent standard of living even though they were able-bodied and had work. (The need for public support for the old, the sick and children was never questioned.) The ‘Speenhamland System’, introduced in the 1790s, involved the payment of allowances linked to the price of bread to men earning low wages. These payments were financed from local taxation, and aroused great controversy. Some people argued that the system depressed wages, exacerbating the position of the poor instead of relieving it.

The French Revolution in 1789 and the ensuing wars (1793–1815) had a profound effect on economic thought. The Revolution raised the spectre of republicanism, and popular unrest was a constant worry for the ruling classes in Britain, especially after the outbreak of war in 1793. The war also created acute economic problems. A financial crisis in 1797 led to the suspension of the convertibility of sterling into gold, and Britain remained on a paper currency until 1819. During the decade and a half after the suspension, the number of banknotes issued by the Bank of England increased and prices rose. A particular problem was the rise in the price of grain, which raised agricultural rents and caused an expansion in the amount of cultivated land. Farmers and landlords prospered. At the same time, people were becoming aware that the ‘manufacturing system' was growing rapidly. Steam power, though still used only on a small scale, was spreading, and mechanization was rapidly transforming the long-established woollen industry and making possible the dramatic growth of the newer cotton industry. The mix of social unrest caused by high food prices and the social dislocation caused by industrial change was a potent one, especially when combined with fear of French republicanism.

A key figure in the transition from the moral philosophy of Hume and Smith to classical political economy was Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834). In the 1790s, radicals, of whom William Godwin (1756-1836) and the Marquis de Condorcet (1743–94) were most prominent, argued that private property was the root of social ills and that resources should be distributed more equally so as to provide everyone with a decent standard of living. Given Condorcet's links with the policies that developed in France, under Robespierre, into the Terror (in which Condorcet was killed), this was regarded as a seditious doctrine by much of the British Establishment. Malthus, a clergyman in the Church of England, responded to such arguments with his Essay on the Principle of Population. This was published as a small, anonymous, tract in 1798, then considerably expanded and published under his name in the second edition of 1803. In it, Malthus offered a series of related arguments against utopian views, focusing in particular on Godwin. Far from being a source of harm, Malthus argued, private property was essential, for otherwise self-love would fail to have the beneficial effects that Smith had pointed out. Giving money to the poor would not improve their condition unless someone else was prepared to consume less, for it would have no effect on the quantity of resources available. Furthermore, any extension of poor relief would increase the dependence of the poor on the state – something Malthus viewed with apprehension. Under the Poor Laws, the poor were ‘subjected to a set of grating, inconvenient, and tyrannical laws, totally inconsistent with the genuine spirit of the constitution… utterly contradictory to all ideas of freedom… [and adding] to the difficulty of those struggling to support themselves without assistance’.1

Though it was only one among many ideas presented in the Essay, Malthus has become most widely associated with the argument that there is a continual tendency for population to outstrip resources. He expressed this by claiming that, if unchecked, population would grow according to a geometric progression (1, 2, 4, 8, 16,…), whereas food supply could grow only in an arithmetic progression (1, 2, 3, 4, 5,…). Population was held down by two types of check: preventive checks, which served to lower the birth rate, and positive checks, which raised the death rate. These two types of check fell into two categories: misery (war, famine) and vice (war, infanticide, prostitution, contraception). In the second edition of the Essay he added a third category, moral restraint, which covered postponement of marriage not accompanied by ‘irregular gratification’. This third category enabled him to reconcile his theory with the evidence he had collected, between 1798 and 1803, that his original theory was not supported by the facts. Moral restraint was very important because it opened up the possibility of progress. However, although Malthus softened the hard line taken in the original Essay, he never shared Godwin's or Condorcet's optimism, for he did not share their belief in the goodness of human nature. Men required moral guidance, and Malthus sought to provide it. The term ‘moral' restraint was carefully chosen.

Malthus, therefore, was operating within the sphere of eighteenth-century moral philosophy. He based his case against the utopians on laws of society – the security of property and the institution of marriage. Socialism was at fault because it violated natural laws. In arguing along these lines, Malthus was arguing that Christianity, properly interpreted, was consistent with the Enlightenment – indeed, that it was the highest form of enlightenment. Though he disagreed with Godwin's and Condorcet's conclusions, he shared with them a belief in reason, presenting himself as applying Newtonian principles to the art of politics. He criticized them for endangering the enlightened, Newtonian, view of science by fostering hopes of progress that could never be realized.

This belief in the power of reason was not shared by Malthus's ‘Romantic' critics, Robert Southey (1774–1843), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) and the other ‘Lake poets’. During his own lifetime, the term ‘Malthusian' came to be used as a term of abuse, referring to the materialistic, spiritually impoverished outlook of what was also called ‘modern political economy’. This was a reaction that continued throughout the nineteenth century, notably with Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), who coined the phrase ‘the Dismal Science’, and John Ruskin (1819–1900). The term ‘economist' came to denote someone with an identifiable approach to politics and a congenitally hard heart.

The Wealth of Nations, with its optimism about the prospects for growth, offered little guidance to politicians facing the problems of wartime. Malthus reoriented political economy so as to respond to these problems, and in doing this he helped lay the foundations for classical political economy. However, he continued to work within the eighteenth-century tradition in which political economy was closely linked to the science of morals and politics. Other economists, though they acknowledged an equally great debt to the Wealth of Nations, did not share this perspective and sought to turn political economy into a secular science.

After Adam Smith, the main influence on the classical economists was Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), a man idolized by his followers. His utilitarianism arose out of the natural-law tradition, though Bentham rejected the idea of natural law. Moral codes did not reflect natural laws, but arose to serve the needs of society. Civil laws, needed to provide rules by which conduct was to be governed, should be based on moral codes, but both might become outdated and need to be changed. The standard by which moral rules and civil laws should be judged was ‘the principle of utility' – the maximization of the sum of the happiness of the individuals that make up a society. This was also the standard that should be used to judge government actions.

Bentham's interpretation of utilitarianism rested on some clear-cut value judgements. (1) Society's interest is the sum of the interests of the members of society. (2) Every man is the best judge of his own interests. (3) Every man's capacity for happiness is as great as any other's. These resulted in a philosophy that was both egalitarian and individualist and served as the foundation for Bentham's elaborate schemes for legal and penal reform. For Bentham, however, the principle of utility did not reduce policy-making to a simple rule. Utility had several dimensions (intensity, duration, certainty, and nearness), and it was necessary to balance these against each other. The utilitarian principle nonetheless provided a rough guide that policy-makers could follow.

Bentham wrote on economic questions, acknowledging his debt to Smith, but his major influence was indirect, through his followers, the Philosophic Radicals. Among these, the most eminent were James Mill (1773–1836), Mill's intellectual protégé, David Ricardo (1772–1823), and John Stuart Mill (1806–73). James Mill studied divinity in Edinburgh and briefly became a Presbyterian preacher before turning to teaching. In 1802 he moved to London to pursue a career as a journalist and writer. His major work was A History of British India (1818), after which he obtained a post in the India Office, rising to the position of Chief Examiner, the senior permanent post in the government of India. In London he became a close associate of Bentham. Ricardo, the son of a stockbroker, came from a Jewish family. He married a Quaker and was subsequently disowned by his father. At Mill's instigation, he became a Member of Parliament. John Stuart Mill was the son of James Mill and received a very rigorous education from his father. At three he started Greek, and at eight Latin, algebra, geometry and differential calculus. Political economy and logic came at twelve. He spent many years working at the India Office, rising to the same position as his father, and in 1865 he became a Member of Parliament.

The Philosophic Radicals were actively engaged in politics, using utilitarianism as the basis for criticizing the institutions of society and advocating policies of reform. By the standards of the day they were genuine radicals, even though their schemes were far removed from the socialism of Godwin and Condorcet or of some of their contemporaries such as Robert Owen (1771–1858), author of the New Lanark socialist experiment. They remained, like Malthus, Whigs. However, though James Mill and Ricardo were close to Malthus on many issues (Ricardo and Malthus were close friends, constantly debating economic issues), they did not share his commitment to economics remaining a moral science. For them economics was political economy, but they sought to make it a rigorous discipline offering conclusions as certain as those offered by Euclidean geometry. This resulted in the subject becoming, in Ricardo's hands, more abstract and less inductive than in the hands of either Smith or Malthus.

Ricardian economics was a response to the situation in Britain during the Napoleonic Wars (1804–15), when the price of corn (wheat) and agricultural rents rose dramatically and the margin of cultivation was extended. Ricardo sought to demonstrate two propositions: that, contrary to what Smith had argued, the interests of the landlords were opposed to the interests of the rest of society, and that the only cause of a declining rate of profit was a shortage of cultivable land. It is easy to see how such a perspective arose from Britain's wartime experience. Influenced by James Mill, with his desire to make political economy as rigorous as Euclidean geometry, in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (published in three editions, 1817–23) Ricardo constructed a system that was unprecedented in the analytical rigour with which it was developed.

Ricardo's system rested on three pillars: a Smithian perspective on the link between capital accumulation and growth, the Malthusian theory of population, and the theory of differential rent. The last of these was worked out, apparently independently, by Malthus, Ricardo, Edward West (1782–1828) and Robert Torrens (1780–1864), in 1815. The theory rested on two assumptions: that different plots of land were of different fertility, with the result that applying the same labour and capital to them would yield different quantities of corn, and that agricultural land had no alternative use. Competition would ensure that the least fertile plots of land under cultivation would earn no rent: the corn produced would sell for just enough revenue to cover production costs, with the result that there would be nothing left for the landlord. If there were a surplus, more land would be brought under cultivation; if costs were not covered, the land would not be cultivated. All other plots of land, however, because they must by definition be more fertile, would yield a surplus. Being the owner of the land, the landlord would be able to demand this surplus as rent. The result was that rent emerged as the surplus earned by land that was more fertile than the least fertile land under cultivation.

The theory of differential rent explained the share of national income that was received by landlords. The Malthusian population theory was then used to explain the share of income received by workers. While wages might rise above or fall below this level if the population were growing or declining, they were linked, in the long run, to the subsistence wage rate. The residual after deducting rent and wages was profit, the share of income accruing to capitalists. From there it was a short step to a theory of economic growth. High profits would encourage capitalists to invest, raising the capital stock. This would raise the demand for labour, keeping wages high and causing population growth. However, as the population grew, so too would the price of corn, the result being that the margin of cultivation would be extended: more land would be cultivated, and plots already under cultivation would be cultivated more intensively. As this happened, rents would rise, eating away at profits (wages could not fall, at least for very long, below subsistence, so could not be reduced). This fall in profits would cause the rate of capital accumulation, and hence the rate of growth, to fall.

It was thus apparently a short step to Ricardo's two key propositions. As capital accumulated, rents rose but profits fell. Given that capital created employment, this was bad for the workers too. In addition, Ricardo had shown that falling productivity in agriculture, caused by the need to bring decreasingly fertile land into cultivation, was the cause of a declining profit rate. There were complications, however. The first was that, as growth took place and demand for food increased, it might be possible to import food, thus removing the necessity to extend the margin of cultivation. These imports would have to be paid for through exports of manufactured goods. In itself this caused no analytical problems: capitalists would invest in either agriculture or manufacturing, depending on the rate of profit available in each, so, if agriculture could not be expanded without lower profits, capital would move into manufacturing, creating the necessary exports.

However, the introduction of a manufacturing sector into Ricardo's model raised major theoretical problems. The first was that, if there were two goods (food and manufactures), Ricardo needed to explain their relative price: he needed a theory of value. For this he turned to the labour theory of value – the theory that prices of commodities will be proportional to the labour required to produce them. The problem here, cutting through an immensely technical issue, is that, under competition, prices will be proportional to production costs and production costs will depend on the amount of capital used, not just the quantity of labour. It follows that the ratio of price to labour cost will vary according to the ratio of capital to labour in an industry. The labour theory of value will not hold. Ricardo struggled to find a way out of this problem, but in the end he had to resort to an act of faith – he used a numerical example to argue that, in practice, variations in labour time explained virtually all variations in relative prices (93 per cent in his example).

The existence of manufactured goods also created problems for Ricardo's claim that diminishing agricultural productivity was the only cause of a declining profit rate. If workers consumed only corn, this would be true. Agriculture would be self-contained (corn would be the only output and the only input), and the rate of profit would not depend on conditions in manufacturing. Competition would ensure that the rate of profit earned in manufacturing, and hence in the whole economy, would equal that earned in agriculture. On the other hand, if workers' subsistence were to include, say, clothing as well as food, then the subsistence wage would depend on the cost of producing clothing as well as the cost of producing food. Agriculture would not be self-contained. The result would be that the rate of profit would depend on conditions in manufacturing as well as on those in agriculture. Ricardo's theorem that agricultural productivity was the only determinant of the profit rate would be undermined.

It is clear, even from this account, that in Ricardo's economics we are dealing with a level of analytical rigour that is to be found in few, if any, of his predecessors. Ricardo simplified the world he was analysing to the point where he was able to show with strict logic that his conclusions followed. When account is taken of the aspects of his system that are not discussed here (notably his theories of international trade and money) these remarks apply a fortiori.

Ricardo's two propositions, though rooted in wartime conditions, had clear political implications in the nineteenth-century post-war world. After the war, corn prices remained high because of the Corn Laws, which prevented a price fall by severely restricting imports. His message that the interests of the landlords were opposed to the interests of the rest of society resonated with many political agitators: workers wanted cheaper corn so that their wages would buy more, and manufacturers wanted cheaper corn in the belief that it would reduce wages. Furthermore, Ricardo's theory argued that, unless the Corn Laws were repealed, profits would fall and growth would come to a halt. However, even if the Corn Laws were repealed, there would still be problems, the reason being that, if Ricardo's theory were correct, growth would involve the progressive expansion of manufacturing relative to agriculture. Britain would become the workshop of the world, exporting manufactured goods and importing corn. This was unacceptable to conservatives such as Malthus.

One of the most significant points about Ricardo's predictions is that they were based on a fallacy in his reasoning. He argued that it would not be in the interest of landlords to undertake improvements. Rises in productivity would simply cause the margin of cultivation to contract, with the result that rents would not rise. This, however, refers to rents in the economy as a whole. What Ricardo failed to see is that, even if aggregate rents do not rise, it will still be in the interests of individual producers to make improvements. This means that improvements will be introduced. If improvements are made, his predictions about the falling rate of profit and class conflict are undermined. The reason why this apparently small technical detail is so important is that Ricardo's mistake followed directly from his method. He theorized about aggregates, viewing agriculture as one giant farm. This approach allowed him to reach striking conclusions, but was potentially misleading.

Ricardian economics made a deep impression. In the words of one commentator, it ‘burnt deep scars on to the classical-economic consciousness’.2 It was also the origin of Marx's economic theory and of many concepts that were used in more orthodox economics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The idea that the rate of profit depended on the marginal cost of growing corn (the cost of growing an additional unit of corn, which would typically be higher than the unit cost of the corn that was already being grown) – arguably the defining theme in Ricardian economics – persisted throughout English economics up to the 1880s. In this sense, Ricardo had a lasting influence. However, Ricardian economics in its purest form (including the labour theory of value, Ricardo's deductive method and the theory of population) dominated the subject for only a brief period in the early 1820s.

The labour theory of value was strongly criticized by Samuel Bailey (1791–1870) in 1825. Bailey argued for a subjective theory of value in which value depended, not on costs, but on ‘the esteem in which an object is held’.3 Nassau Senior (1790–1864), appointed to the first chair of Political Economy at Oxford, moved away from both the Malthusian population doctrine and the labour theory of value. He introduced the idea that profits were not a surplus but a reward to capitalists for abstaining from consuming their wealth. He also formulated the idea that the value of an additional unit of a good (the concept that, in the 1870s, came to be called marginal utility) declined as more of the good was consumed. John Ramsay McCulloch (1789–1864), Professor of Political Economy at University College London from 1828 to 1837 and the most prolific economic writer in the Whig Edinburgh Review, was at one time a staunch Ricardian. However, he substantially modified his views, placing a much greater emphasis on history and inductive research than did Ricardo. He rejected Ricardo's view of class conflict. He considered it fallacious on the grounds that individual landlords would always have an incentive to introduce improvements. This would raise the productivity of land and would offset the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

In short, English classical economics was not purely Ricardian. It reflected the work of a variety of individuals, and encompassed a plurality of views on most questions. If one work dominated, it was not Ricardo's Principles but Smith's Wealth of Nations, with its more catholic blending of theory and history. Even in 1900 there were still textbooks organized on Smithian lines.

Outside England, the influence of Ricardian economics was even less strong. In France, Smith's main interpreter was Jean Baptiste Say (1767–1832), a member of the Tribunate under Napoleon, and later an academic economist. Say was widely considered the leading French economist of his generation. Though a supporter of Smithian ideas, he advocated a subjective theory of value, consistent with a long-standing French tradition going back at least to Condillac. He also developed the law of markets. This was the proposition, previously put forward by Bentham and James Mill, and accepted by Ricardo, that there could never be a shortage of demand in general: that supply creates its own demand. Depressions arise not from a shortage of demand in the aggregate, but from shortages of demand for particular commodities.

Equally important, there developed in France a long tradition of applying mathematical analysis to economic problems. Condorcet had paved the way with his analysis of voting theory. He had shown, for example, that if there were three or more candidates in an election, majority voting might result in the election of a candidate who would lose in all two-candidate contests. However, the person who made what to modern economists is the most remarkable contribution was Antoine Augustin Cournot (1801–77). Cournot was briefly Professor of Mathematics at Lyon, but spent most of his career as a university administrator. Making the assumption that each producer maximized profit, and that sales in the market were constrained by demand, he derived equations to describe the output that would result if there were different numbers of firms in an industry. Starting with a single producer (a monopolist) he showed how output would change as the number of firms rose, first to two, and then towards infinity. For Cournot, competition was the limiting situation as the number of firms approached infinity. In a competitive market, no firm could affect the price it received for its product.

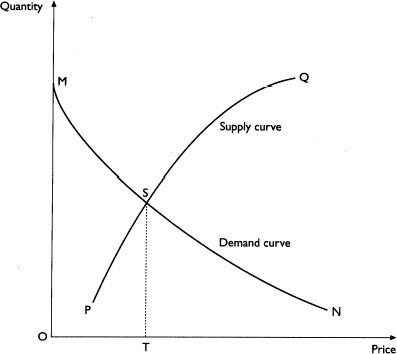

Cournot is also considered to have been the first economist to use a diagram to explain how supply and demand determine price in a competitive market. The demand curve (MN in Cournot's diagram below) shows that the amount that people wish to buy falls as price rises. The supply curve (PQ) shows that the amount that producers wish to sell increases as price rises. The market price (OT) is the price at which supply and demand are equal. Cournot went on to show how the diagram could be used to show how market price would change in response to events such as the imposition of a tax on the commodity.

An emphasis on demand for goods was also characteristic of the work undertaken by engineers at the École des Ponts et Chaussées (School of Bridges and Highways). Their work was prompted by the need to find a basis for deciding the merits of civil-engineering projects. In the 1820s, the conventional view was that such projects should be self-liquidating – that they should completely cover their costs. Claude Louis Marie Henri Navier (1785–1836), well known to engineers for his work on mechanics, challenged this in an article, published in 1830 in Le Génie civil (a civil-engineering journal) and in 1832 in the Annales des ponts et chaussées. His argument was that a public work, such as a canal or a bridge, could raise public welfare. Taxpayers would get goods more cheaply, and the expansion in trade caused by the

Fig. 1 Supply and demand curves

project would increase tax revenues in general. He estimated benefits derived from a project by multiplying the quantity of goods carried using the canal or bridge by the reduction in transport cost produced. If these benefits were greater than the ongoing annual cost of the project, the construction cost should be financed out of taxation. Navier thought that tolls should be zero, but if they had to be levied they should cover only interest payments and regular maintenance. He extended these ideas in later articles and in his lectures at the École des Ponts et Chaussées, taking account of such things as the relation between costs and the length of a railway line. He also considered whether public works should be provided by the state or franchised to private firms, and the type of regulation that should be imposed.

These problems were also tackled, independently of Navier, by Joseph Minard (1781–1870), another engineer, who wrote what he viewed as a practical manual to guide civil engineers involved in public-works projects. He used the idea of a downward-sloping demand curve to argue that Navier's method (quantity of goods carried times the cost saving) would overstate the benefit derived from a project. The reason is that some of the people using the canal or bridge would not have made their journeys had it not been built, which means that the benefit they get from it will be less than the cost saving. He used arguments about the distribution of income between those who use the canal and those who do not to propose that tolls should be charged to cover annual costs. He also produced a formula (involving interest and inflation rates) to calculate the benefits from a project that took time to build, would not last for ever, and had an annual maintenance cost. However, though Minard wrote his manuscript in 1831, the course for which he planned to use it was not approved for many years, with the result that he did not publish his work until 1850. By that time, other articles on the subject had appeared.

Jules Dupuit (1804–66), another engineer concerned with methods by which the benefits of public-works projects could be estimated, also argued, in a series of articles in the 1840s and 1850s, that Navier's method overestimated the benefits. First, what mattered was not the reduction in transport costs but the reduction in the price of products. When production rose following the construction of a new bridge or canal, goods would be transported over longer distances. The result was that production costs would not fall as much as the cost of transport over a given distance. Second (and here he was making a point similar to Minard's) Dupuit argued that the utility of an additional unit of a good could be measured by the price the consumer was willing to pay for it. This price would fall as consumption rose. Dupuit went on to argue that the benefit obtained from building a canal or bridge could be measured by subtracting the cost of the project from the area under the demand curve. The demand curve, used by Cournot simply to analyse behaviour, could be used as a measure of welfare.

The three engineers discussed here form part of a long, well-established tradition at the École des Ponts et Chaussées in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Starting with the practical problem of evaluating civil-engineering projects, they developed an alternative to the orthodox theory of value associated with Smith and Say. Some of Dupuit's later articles were published in the Journal des économistes, but much of the engineers' work was published in journals where economists would not see it. Say did express an interest in Minard's work in 1831, but he died a year later.

Another tradition, owing little to Ricardo, is found in the writers of economics textbooks in Germany, notably Karl Heinrich Rau (1792-1870), Friedrich Hermann (1795–1868), Hans von Mangoldt (1824–68) and Wilhelm Roscher (1817–94). These were Smithian in that they accepted Smith's ideas about the importance of saving and division of labour for economic growth. However, they rejected the labour theory of value. Instead, they took from Steuart the idea that prices are determined by supply and demand. Unlike most of the English classical economists, they attached great importance to demand. Hermann, for example, wrote explicitly about how changes in demand can cause changes in costs. Their textbooks discussed demand before supply, and explored the connections between demand and human needs. The result was a subjective theory of value in which the value of a good depended on what other goods people were prepared to forgo in order to obtain it – subsequently known as an opportunity-cost theory.

As in the French engineering tradition, supply and demand were represented graphically. Independently of Cournot, Rau used a supply-and-demand diagram in the fourth edition (1841) of his textbook. (He began the convention, followed in most of the modern literature, of putting quantity on the horizontal axis and price on the vertical axis.) Unlike Cournot, he analysed not only the equilibrium (where demand and supply are equal) but also the stability of this equilibrium. If price were too high, supply would exceed demand, pushing price down; if price were too low, demand would exceed supply, pushing price up. These ideas were taken further by Mangoldt in his textbook (1863). He argued that the shape of the supply curve would depend on the behaviour of costs as output increased and he used his curves to see how prices would change in response to changes in supply or demand.

For most of the nineteenth century, Germany was not a single country but a mosaic of small states. It is thus not surprising that different approaches to economics could coexist alongside each other. One such tradition is represented by Johann Heinrich von Thünen (1783–1850). Thünen was a farmer who became, by 1827, an internationally known authority on agriculture. His main work, Der isolierte Staat (The Isolated State), was published in three instalments between 1826 and 1863. It is best known for its analysis of location, in which the profitability of agriculture (and hence the level of rent and the type of agriculture that will be undertaken) depends on how far farms are from the city. He took as his starting point a city located in the centre of a large, fertile plain in which there were no rivers or other natural factors affecting transport costs. On such a plain, farming would be organized in a series of concentric circles. Closest to the city would be horticulture and market gardening, the produce of which cannot be transported far. Furthest away would be hunting, for which large tracts of land were needed and where transport costs were not a problem. In between would be various types of forestry, arable farming and pasture.

Perhaps as significant as Thünen's theory of location was his method. He tackled the question of how much capital and labour to use by regarding it as a maximization problem. Farmers use the quantities of capital and labour that will maximize their profits. Thünen formulated this problem using algebra, and solved it using differential calculus. By these methods he obtained the result that the wage paid will equal the contribution to output made by the last worker to be employed – the marginal-productivity theory of distribution. These methods also led him to see the problem of forest management as one involving time and the rate of interest. If the essence of capital is seen as being that it allows production to take place over time (a view later developed by Austrian economists), this can be seen as a marginal-productivity theory of the rate of interest.

The British classical economists wrote during the period when economics was only just beginning to become institutionalized as an academic discipline. They were linked by organizations such as the Political Economy Club (a group, founded in 1821, that met each month to discuss economic questions), the Royal Society, the Royal Statistical Society and the British Association. The journals in which their ideas were published did not specialize in economics, but addressed the educated classes in general and were frequently identified by their political leanings, not by their disciplinary coverage. The Edinburgh Review was Whig, the Westminster Review was Benthamite, and the Quarterly Review was Tory. Some economists held academic posts (often for short periods, not as a lifelong career), but most did not. For example, Ricardo was a stockbroker; Torrens had served in the army and was a newspaper proprietor, West and Mountifort Longfield (1802–84) were lawyers, and McCulloch (a professor for a brief period) was a civil servant and for a short time editor of the Scotsman. Many had a legal training, and many held government appointments at some stage in their careers. However, though abstract issues were discussed, political economy was never far from questions of economic policy. Many economists and many members of the Political Economy Club were Members of Parliament. Even when they were not involved in policy-making, however, almost all the economists formed part of the circles in which policy-makers moved, and they played an active role in discussions of economic policy. In the 1830s, after the Reform Act of 1832 (which extended the franchise to most of the propertied classes), the Philosophic Radicals formed an identifiable group in Parliament.

Though there were enormous differences between economists, it is a fairly safe generalization to say that they were in general pragmatic reformers. Like Smith, they opposed mercantilism. In so far as there was an ideological dimension to this, it stemmed from opposition to the corruption associated with mercantilism rather than any commitment to non-intervention. It was generally accepted that government had an important but limited role to play in economic life. Even the Philosophic Radicals, who favoured more radical reforms than most economists, were utilitarian – adhering to a philosophy that placed utility above freedom. They were quite willing to see the government regulate, provided that legislation did not undermine the security of private property, an institution they regarded as crucial in stimulating economic growth. Their attitudes and the changes that took place in the political context are best illustrated by considering some of the major questions that arose in the first three-quarters of the century: trade policy, poor relief, and labour-market policies.

The classical economists were basically free-traders, and produced a wide range of arguments to support their stance. Not only was there the ‘invisible hand' argument found in the Wealth of Nations, they also pointed to the opportunities that protection provided for corruption and the distortion of domestic industry in favour of powerful groups. There were debates over whether free trade should be imposed unilaterally or on the basis of commercial treaties, but on the whole they supported unilateral free trade. The most contentious issue in trade policy, however, concerned the Corn Laws. Ricardo's theory was aimed at precisely this issue and provided a strong case for repeal, but this was not the ground on which most economists argued. They were influenced more by Smith. Thus McCulloch and Senior rejected Ricardo's arguments that the interests of the landlords differed from those of other classes in society. Some economists even supported the levying of tariffs to raise revenue, provided that these were not sufficiently high to distort trade flows.

The Poor Law was an issue for which the Malthusian theory had direct implications. Malthus and Ricardo favoured the abolition of the Poor Law, though both wanted this to be done gradually. Others thought this solution impracticable and favoured radical reform. Senior, for example, argued for the policy embodied in the Poor Law Amendment Act (1834), under which relief for the able-bodied poor was confined to those living in workhouses and which tried, in vain, to enforce the principle of less eligibility (that those out of work should be worse off than anyone in work). Most of the classical economists, however, were more relaxed about the provision of poor relief, being sceptical about the Malthusian argument that it would inevitably stimulate growth in the number of paupers. They wanted to continue ‘outdoor' relief, and were not insistent on enforcing the principle of less eligibility.

Industrialization was changing dramatically the conditions under which an increasing proportion of people worked, and there was pressure for government regulation. In addition, trade unions began to be formed after the repeal of the Combination Laws (under which the formation of unions was illegal) in 1824. On neither issue did the economists adopt a doctrinaire position. The first act regulating factory conditions had been passed in 1802, and during the following decades a series of acts was passed increasing the degree of regulation. In much of this legislation the main target was children's and women's hours and conditions of work, but legislation here inevitably affected men too. There was a tendency to refrain from regulating adult men's hours, on the grounds that this would interfere with the principle of freedom of contract, but in general the economists were pragmatic and responded to events. They kept up with public opinion rather than leading it. On trade unions, the economists' position was generally to favour high wages and to view unions as counterbalancing employers' higher bargaining power.

The classical economists accepted the Smithian case for free enterprise, and many of them viewed the encroachments of the state on individual liberty with great suspicion. On neither, however, were they doctrinaire. They judged particular cases according to the principle of utility. The result was a pragmatic outlook in which the role for laissez-faire was severely circumscribed.

Monetary policy was a major concern of the classical economists from the 1790s onwards. In 1793 and 1797 serious financial crises took place against the background of a banking system that had changed significantly since Hume's work on the subject. These formed the background to An Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain (1802) by a banker, Henry Thornton (1760-1815). Thornton viewed banknotes and bills of exchange as assets that people hold, with the result that he placed great emphasis on confidence. If people became uncertain about the value of the assets they were holding (whether bills of exchange or notes issued by banks outside London), they would increase their holdings of the more secure asset. In Thornton's day this meant notes issued by the Bank of England. Thornton thus perceived that there was a hierarchy within the banking system. In times of crisis, when they experienced a run on their reserves, the country banks (outside London and generally small) would turn to their correspondents in London for support. These in turn would turn to the Bank of England for liquidity. The Bank of England thus stood at the apex of a pyramid of credit.

This had enormous implications for the policy that the Bank of England should pursue. The normal practice for a bank facing a loss of reserves was to cut back on its lending. However, Thornton argued that this was exactly the wrong policy for the Bank of England, which should increase its lending when it experienced a loss of reserves to the country banks. The reason was that, if there were a crisis of confidence, an increase in the availability of credit from the Bank of England would serve to restore confidence and provide reserves that the rest of the banking system required. This was different from the case of the country banks – an increase in their note issue would reduce confidence in their ability to redeem their notes. In other words, the Bank of England, Thornton argued, should be acting as a central bank, taking responsibility for the financial system as a whole.

After 1804 the price of gold bullion rose significantly above its par value, established by Newton at £3 17s. 10½d. per ounce. In other words, the value of the Bank of England's notes had fallen. Ricardo, in 1810, argued that the rise in the price of bullion reflected the overissue of notes by the Bank of England. He argued that the directors of the Bank could not be trusted to manage the issue of notes, and that convertibility should be restored – albeit gradually. This was the strict bullionist position – that notes should be convertible into bullion. This was also Thornton's position, though unlike Ricardo he accepted that the link between note issue and the price of bullion might be weak in the short run. In the short run it was possible for factors that affected the balance of payments – such as bad harvests (which caused an increase in imports of corn), subsidies to foreign governments, or overseas military expenditure – to raise the price of bullion independently of the note issue.

The anti-bullionist position can be found in the writings of the directors of the Bank of England. They denied that the quantity of banknotes in circulation bore any relationship to the price of bullion. Their argument was the so-called ‘real-bills doctrine’. This was the theory that, provided a bank lent money against ‘real bills' (bills issued to finance genuine commercial transactions, not to finance speculation), the bills would automatically be repaid when the transaction was complete. The amount of currency in circulation would therefore exactly equal the demand for it. It was assumed that no one would borrow money and pay interest if they did not need to. The answer to this was offered in Thornton's Paper Credit. Thornton pointed out that the decision on whether to borrow money from a bank would depend on how the interest rate on the loan compared with the rate of profit that could be obtained through investing the money. If the interest rate were below the profit rate, people would have an incentive to increase their borrowing, the circulation of banknotes would increase, and prices would rise. This process would continue for as long as the interest rate was below the profit rate. Conversely, if the interest rate exceeded the profit rate, the quantity of notes issued and the price level would fall. The real-bills doctrine, with its assumption that no one would borrow money unnecessarily if interest had to be paid on it, was thus flawed.

A parliamentary report into the currency in 1810, largely drafted by Thornton, supported the bullionist case, and as a result the government took the decision to return to convertibility, this being achieved in 1819. However, this did not end discussions of monetary policy. The period after 1815 was one of severe deflation – of depression and falling prices. Although the policy of maintaining convertibility of sterling into gold was not questioned, it became clear that this in itself was not enough. The Bank of England's policy had to be organized so as to ensure that its bullion reserves were always sufficient for convertibility to be maintained. This led into a debate over what would nowadays be termed counter-cyclical policy: economists debated the merits of alternative ways of coping with fluctuations in the demand for credit.

The banking school argued that monetary policy should be conducted according to the needs of the domestic economy. In a depression there was a shortage of credit, and so the note issue should be expanded. If too many notes were issued, they would be returned to the Bank – the so-called ‘doctrine of reflux’. It stressed that notes were merely one among many forms of credit. One of the main supporters of the banking school, Thomas Tooke (1774–1858), countered Thornton's argument that low interest rates led to inflation with extensive statistical evidence to show that inflation typically occurred when interest rates were high. In opposition to this view, the currency school, of which Lord Overstone (1796–1883) was the leading member, advocated the so-called ‘currency principle’, or ‘principle of metallic fluctuation’. This was the principle that a paper currency should be made to behave in the same way as a metallic currency would behave. This meant that, if the Bank of England lost gold, it should reduce its note issue pound for pound. The money supply would thus be linked to the balance of payments. This was, like the banking school's proposal to meet the needs of trade, a counter-cyclical policy, for it was designed to ensure that corrective policies would be implemented before an expansion had gone too far. Without the currency principle, the currency school argued, action would be taken too late. Thus, whereas the banking school focused on policy to alleviate depressions, the currency school sought to design a policy that would make them less likely to occur.

That Ricardian economics exerted an influence beyond the 1820s is due to two people, both major figures in nineteenth-century intellectual history. The first of these was John Stuart Mill. Mill was educated by his father to be a strict disciple of Bentham. In the 1820s and 1830s he was a member of the Philosophic Radicals. Around 1830 he wrote a series of essays on economics in which he built upon the Ricardian approach to economics, but he had problems in finding a publisher and they were not published till 1844, after the great success of his System of Logic (1843). After his father's death in 1836, and influenced by Harriet Taylor (1807–58), whom he married in 1851, Mill moved away from a narrow utilitarian position and became much more sympathetic to socialism – albeit a form of socialism very different from what is now meant by the term, in that he did not advocate state ownership of the means of production. His main contribution to economics was his Principles of Political Economy, published in several editions between 1848 and 1873. This served as the point of departure for most British and many American economists until the publication of Alfred Marshall's Principles of Economics in 1890.

Mill's achievement in the Principles was to retain the Ricardian framework but at the same time to take into account the many points made by Ricardo's critics. Given that Mill did not lay claim to originality and that he claimed to be doing little more than updating Smith's Wealth of Nations, the result was a book that has been dismissed as eclectic. This, however, is to understate Mill's originality and creativity. The basic theory of value, income distribution and growth was Ricardian, but Mill modified it in important ways. He placed much greater emphasis on demand in explaining value, and the way in which he conceived demand (as a schedule of prices and quantities) marked a significant change from the Smithian and Ricardian concept. When applied to international trade (in his theory of reciprocal demand), the result was a theory that went far beyond Ricardo in two ways. It allowed for the possibility that costs might change with output, and it explained the volume of goods traded. He followed Senior in accepting that profits might be necessary to induce capitalists to save.

Perhaps the main significance of Mill's Principles, however, was that, although it retained the basic Ricardian framework, it embodied a radically different social philosophy. Mill wrote of seeking to emancipate political economy from the old school, making it less doctrinaire than it had become in many quarters. In this he was strongly influenced by socialist writers, notably a group known as the Saint-Simonians, named after Claude Henri Saint-Simon (1760–1825), who advocated a form of socialism in which the class structure of society was changed but in which production was controlled by industralists. Mill reconciled his adherence to Ricardian theory with a social outlook that verged on socialism through introducing, at the start of the Principles, a distinction between the laws of production and the laws of distribution. After a survey of the evolution of societies, reminiscent of the Scottish Enlightenment, he argued that the production of wealth depended on factors beyond human control:

The production of wealth… is evidently not an arbitrary thing. It has its necessary conditions. Of these, some are physical, depending on the properties of matter, and on the amount of knowledge of those properties possessed at the particular place and time… Combining these facts of outward nature with truths relating to human nature it [political economy] attempts to trace the secondary or derivative laws, by which the production of wealth is determined.4

These laws of production were based on the physical world, knowledge of that world, and human nature. In contrast, the laws governing the distribution of wealth depended on human institutions:

Unlike the laws of production, those of distribution are partly of human institution: since the manner in which wealth is distributed in any given society, depends on the statutes or usages therein obtaining.

He added, however, the qualification that

though governments have the power of deciding what institutions shall exist, they cannot arbitrarily determine how these institutions shall work.5

Political economy could discern the laws governing economic behaviour, enabling governments to create appropriate institutions. Social reform therefore involved redesigning the institutions of capitalism.

The institutions through which Mill sought to improve society were ones that gave individuals control over their own lives. He supported peasant proprietorship, giving small farmers the incentive to improve their own land and raise their incomes. He advocated producers' cooperatives and industrial partnerships (involving profit-sharing) as institutions that would enable workers to share responsibility for the successful conduct of business. These schemes all had the characteristic that they maintained incentives. He described such schemes as socialist – the difference between socialism and communism, as he used the terms, being that socialism preserved incentives whereas communism destroyed them. He still accepted the Malthusian theory of population growth, but he believed that education of the working classes (including education about birth control) would lead them to see the advantages of limiting family size and that living standards would then be able to rise. This outlook also affected his view of the stationary state. Growth might slow down, but if workers turned to self-improvement there would be no cause for concern.

As his book On Liberty (1859) makes clear, Mill was a liberal in the classical nineteenth-century sense. He believed in individual freedom. He was even prepared to argue that there should be a general presumption in favour of laissez-faire. However, he was far from an unqualified supporter of laissez-faire, going so far as to describe the exceptions as ‘large’. He listed five classes of actions that had to be performed by the state, ranging from cases where individuals were not the best judges of their own interests (including education) to those where individuals would have to take action for the benefit of others (including poor relief) if the state were not involved. He argued that anything that had to be done by joint-stock organizations, where delegated management was required, would often be done as well, if not better, by the state. Even more radically, Mill argued that there might be circumstances in which it became desirable for the state to undertake almost any activity: ‘In the particular circumstances of a given age or nation, there is scarcely anything, really important to the general interest, which it may not be desirable, or necessary, that the government should take upon itself, not because private individuals cannot effectually perform it, but because they will not.’6 Having made the case for laissez-faire, Mill thus qualified it so heavily as to leave open the possibility of a level of state activity that many would regard as socialist.

The other major mid-nineteenth-century economist to build on Ricardo's economics was Karl Marx (1818–83). However, whereas Mill remained within the classical framework laid down by Smith and Ricardo, Marx sought to provide a radical critique of orthodox ‘bourgeois' political economy. His starting point was the study of ancient philosophy at the University of Berlin, then dominated by the ideas of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831). Central to Hegel's work was the idea of dialectics, according to which ideas progressed through the opposition of a thesis and an antithesis, out of which a synthesis emerged. However, whereas Hegelian dialectics applied to the realm of ideas, Marx offered a dialectical analysis of the material world and the evolution of society (historical materialism). Each stage of history produced tensions within itself, the outcome of which was a move to a new, higher, stage of society. Feudalism gave way to capitalism, which in turn would give way to socialism and eventually to communism, the highest stage of society. This dialectical analysis of the material world is Marx's historical dialectics.

Marx's writings fall into several distinct stages. In the early 1840s Marx worked as a journalist in the Rhineland, where he had to tackle economic issues such as free trade and legislation on the theft of wood. The theoretical framework that underlies his later work was completely absent – he considered the notion of surplus value (an idea central to his later work) an ‘economic fantasy’. In 1844, however, Friedrich Engels (1820–95), a cotton manufacturer with interests in Britain and Germany, who became Marx's lifelong friend, supporter and collaborator, introduced him to English classical economics. In an article published the previous year, Engels had argued that the intensity of competition among workers impoverished them. Capitalists could combine to protect their own interests and could augment their industrial incomes with rents and interest, whereas workers could do neither. Marx, in 1844, went on to explain low wages in terms taken straight from Smith. If demand for a product falls, at least one component of price (rent, profits or wages) must fall below its natural rate. He argued that, with division of labour, workers became more specialized and therefore found it harder to move from one occupation to another. The result was that when prices fell it was the workers whose incomes were reduced below the natural rate. Capitalists were able to keep the competitive price of their product above the natural price – to charge more than the value of their produce, and hence to extract a surplus.

In the next three years Marx studied Ricardo further and adopted the labour theory of value. However, whereas Ricardo had used the term ‘value' to mean the price of a commodity, Marx defined value as something that lay beneath price: the labour time required to produce a commodity. Value and price were distinct. The significance of this was that it provided him with a rigorous explanation of how exploitation could arise, even in equilibrium. Exploitation was inherent in the basic relationships of capitalist production.

The year 1848 saw publication of The Communist Manifesto and Marx's involvement in the revolutions that took place (especially the one in Paris), followed by his exile to Britain. In London he turned again to economics and started work on a more systematic, scientific treatment of the subject. The main manuscript dating from this period, the Grundrisse, was never finished for publication (though it was published many years later). By the end of the 1850s all he had published was a short introduction to the subject, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), his first major economic work. In correspondence with Engels, he outlined a project involving six volumes, dealing with capital, landed property, wage labour, the state, international trade, and the world market. His major work, Capital, was thus conceived as the first volume of a much larger study. Capital itself grew to three volumes, only one of which was published in Marx's lifetime, in 1867; the remaining two volumes were published by Engels in 1885 and 1894. (Marx also wrote the material on the history of economic thought later published as Theories of Surplus Value, planned as the fourth volume of Capital.)

Capital is characterized by the method of inquiry (discussed in more detail in the Grundrisse) that some scholars have termed ‘systematic' dialectics. In this method, ideas are criticized from within (as Marx was analysing capitalism from within a capitalist society) in a series of stages that lead from the abstract to the concrete. Because the analysis started with very abstract categories, it could explain only very general phenomena in its early stages. At each stage, it failed to explain more complex empirical phenomena. However, this failure carried the analysis forward to more complex and concrete categories. This movement from the abstract to the concrete is reflected in the organization of the three volumes of Capital. Volume 1 starts with the concept of a commodity and the process of capitalist production. It discusses value and the production of surplus value (explained in the next paragraph), and analyses the antagonism between capital and labour. Volume 2 discusses the circulation of capital and the various forms that capital can take. Volume 3 investigates competition and the antagonism between capitalists. Whereas Marx dealt with capital and surplus value as very abstract concepts in Volume 1, by Volume 3 these categories have become much more complex. The result is that he is able to explain many more empirical features of capitalism, such as the division between interest payments and entrepreneurial profits, and the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

Marx's argument about exploitation rested on the distinction between labour and labour power. The value of an individual's labour power was, like the value of anything else, its cost of production (measured in labour time). If it took, for example, six hours' labour to produce the goods a worker needed in order to subsist and reproduce, the value of his labour power was six hours. However, it might be possible to force the worker to work for ten hours – his labour. The worker produced goods to the value of ten hours' labour, but his wages would be only six hours' labour, for this was the value of his labour power. The result would be the creation of surplus value equal to four hours' labour. This surplus value, Marx contended, was the source of profit. The reason why capitalists could exploit labour in this way was that they owned the means of production. Because capitalists owned the means of production, workers could not undertake production themselves. They were forced to sell their labour power to the capitalists. Exploitation thus lay at the heart of the capitalist system: it was not an accidental feature that could be removed without affecting the entire structure of the system.

The surplus value created by extracting unpaid labour from workers and fixing it in commodities was realized by the capitalist as a sum of money. Capital, however, was not simply money. To function as capital, it had to be transformed first into means of production and labour power, then into capital in the production process, then into stocks of commodities, and finally, once the commodities were sold, into money again. The simplest form of this circuit was summarized by Marx as M–C–M' (money–commodities–more money). He analysed this in two stages. The first was ‘simple reproduction’, in which an economy reproduced itself on an unchanged scale. The second was ‘extended reproduction’, where capital was increasing. He agreed with Smith that capital accumulated not because capitalists hoarded money but because they used money to employ labour productively.

In Volume 2, after an extensive discussion of the circulation of capital and the different forms that capital took in the process of circulation, Marx illustrated the process with some numerical examples – his reproduction schemes – inspired by Quesnay's Tableau. These were based on a division of the economy into two ‘departments' or sectors. Department 1 produced capital goods, and Department 2 produced consumption goods that might be consumed by either capitalists or workers. He also distinguished two of the forms that capital could take: constant capital (machinery etc.) and variable capital (used to employ labour). The economy started with given stocks of constant and variable capital. Simple reproduction occurred when, after capitalists had used their surplus value to purchase consumption goods, the produce of the two departments was exactly sufficient to reproduce the capital used up in production. Extended reproduction occurred when stocks of capital at the end of the process were larger than at the beginning, with capitalists turning part of their surplus into constant and variable capital. Marx was using what would nowadays be called a ‘two-sector' model to analyse the process of capital accumulation.

Volumes 1 and 2 remained at a very abstract level, analysing the movement of capital as a whole. In Volume 3 Marx considered the concrete forms taken by capital – notably costs of production, prices and profits. He analysed the way in which surplus value was converted into various forms of profit and rent. Here he addressed the problems that Ricardo had encountered when working out his labour theory of value. Prices would be higher than values in industries that employed a high proportion of fixed capital, and lower in industries where little fixed capital was used. Prices, therefore, would not be proportional to labour values. For Marx, this arose as the transformation problem – the problem of how values were transformed into prices. As he defined values in terms of labour time, this problem did not undermine his labour theory of value as it did Ricardo's.

Marx's analysis of the dynamics of capitalism went far beyond his reproduction schemes. It is not possible to cover all the details, but several points need to be made. The first is that Marx predicted that capitalist production would become more mechanized and more centralized. Increased mechanization led to what Marx called a rising ‘organic composition of capital' – a rising proportion of capital would take the form of constant (fixed) capital, and a lower proportion would take the form of variable capital. Because surplus value was produced by variable capital (by exploiting living labour), this meant that surplus value per unit of capital would fall and with it the rate of profit. Capitalists would attempt to offset this by increasing the exploitation of workers by means such as increasing the length of the working day and forcing workers to work more intensively.

Marx was also led into analysing economic crises and the business cycle. Capitalists, he argued, were forever striving to accumulate capital. From time to time capital would accumulate so rapidly that they would be unable to sell all the output that they were producing. The result would be a crisis in which they failed to realize their profits. Capital would be liquidated as some businesses failed and others simply failed to replace the capital that was wearing out. Eventually the rate of profit would rise to the point where new investments were started and the system would move from depression into a new period of expansion. Marx therefore saw capitalism as undergoing successive periods of depression, medium activity, rapid expansion, and crisis. There would be a cycle, the period of which depended on the turnover rate or life cycle of capital goods. He assumed that this had increased, and that by the time he was writing it was around ten years in the ‘essential branches of modern industry’.7

It is also important to note that Marx saw capitalism as containing the forces that would lead to its downfall. The main force was the concentration of capitalistic production:

This expropriation is accomplished by the action of the immanent laws of capitalistic production itself, by the centralization of capital. One capitalist always kills many. Hand in hand with this centralization, or this expropriation of many capitalists by few, develop, on an ever-extending scale, the cooperative form of the labour process, the conscious technical application of science, the methodical cultivation of the soil, the transformation of the instruments of labour into instruments of labour only usable in common, the economizing of all means of production by their use as the means of production of combined, socialized labour, the entanglement of all peoples in the net of the world-market, and with this the international character of the capitalistic regime.8

This centralization would at the same time increase the misery of the working class and cause it to become more organized:

Along with the constantly diminishing number of the magnates of capital, who usurp and monopolize all advantages of this process of transformation, grows the mass of misery, oppression, slavery, degradation, exploitation; but with this too grows the revolt of the working class, a class always increasing in numbers, and disciplined, united, organized by the very mechanism of capitalist production itself.9

Eventually capitalism, which up to that point had been a progressive force, would become an impediment to further development and would be overthrown:

The monopoly of capital becomes a fetter upon the mode of production, which has sprung up and flourished along with, and under it. Centralization of the means of production and socialization of labour at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. This integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.10

Marx never finished Capital, let alone the other books that would have filled out his analysis of the capitalist system. After his death, Volumes 2 and 3 of Capital were edited by Engels from his unfinished manuscripts. There were further delays of around twenty years before these volumes were translated into English. His early writings were not published in German until 1932, and the Grundrisse not until 1953, with English translations of these appearing only during the 1970s. The result of the delay in publication was that for many years his work was virtually unknown. Though written much earlier, and reflecting the situation of the 1860s and 1870s, Marx's economics became widely known only in the 1880s and 1890s. During the twentieth century, interpretations of his work changed as new evidence became available. Given that Marx's writings extended far beyond economics, into philosophy and social science, any interpretation of Marx offered here is inevitably very limited: it is one among many different possibilities.

The first point to make about Marx is that his economics is classical in that he built upon the economics of Smith and Ricardo. Marx's labour theory of value clearly owes much to his reading of Ricardo. It is therefore possible to view Marx as a Ricardian. To do this, however, is to miss the point that, though he started with the classical analysis, he transformed it and produced a radically different type of economics. For the classical economists, the laws of production were laws of nature. For Marx, on the other hand, the laws of production were based on the laws and institutions of capitalism, a specific historical stage in history. Capital could exist only because people had the right to own the produce of other people's labour. Wage labour – common in British industry, but in Marx's time far less widespread than it is today – was another institution central to the process of exploitation. Exploitation, the circulation of money and goods, capital, and the institutions of capitalism were therefore intertwined.

Despite its roots in classical economics, Marxist economics developed largely independently of the mainstream in economic thought. Its other roots in Hegelian philosophy were foreign to the Anglo-Saxon traditions that increasingly dominated the economics profession. The association of Marxian economics with socialist political movements – and, after 1917, with Russia and the Soviet Union – provided a further barrier. As economics distanced itself from other branches of social thought, the Marxian amalgam of economic and sociological analysis became remote from the concerns of most economists.

Marx's economics was, however, important even for non-Marxian economists. The obvious reason is that attempts were made by non-Marxian economists to rebut Marx, and Marxists responded. The most notable example was perhaps the debate between the Austrian economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (see p. 211) and the Marxist Rudolf Hilferding (1877–1941) following the publication of Volume 3 of Capital. Much more importantly, however, Marxian ideas fed into non-Marxian thinking – sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly. Marx's analysis of the business cycle in terms of fixed-capital accumulation fed, via the work of the Russian economist Mikhail Ivanovich Tugan-Baranovsky (1865–1919), into twentieth-century business-cycle theory, which came to focus on relations between saving and investment (see Chapter 10). His analysis of the waste caused by competition between capitalist producers was a crucial input into the debates over the possibility of rational socialist calculation in the inter-war period (see pp. 275–9). Marx's vision of the future of capitalism stimulated economists to offer their own alternatives, as in Joseph Alois Schumpeter's Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1943) (see p. 209).

Classical political economy comprised a great variety of theories and ideas. These ideas were held together by their roots in Smith's Wealth of Nations. Ricardo had created a far more rigorous system based on much more abstract reasoning, but his deductive style of argumentation did not win widespread support. Even Mill – responsible for sustaining the Ricardian tradition after interest in it waned in the 1820s – reverted in his Principles to the combination of inductive, historical analysis and deductive reasoning that characterized the Wealth of Nations.

Classical economics was never far from issues of economic policy: academics formed part of the same intellectual community as politicians, journalists and men of letters. At one end of the political spectrum were supporters of doctrinaire laissez-faire, and at the other were the Ricardian socialists. Most economists, however, fell between these two extremes. They succeeded in using the framework laid down by Smith to address first the policy problems arising during the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, and later those arising from industrialization and the immense social changes that accompanied this. In Smith's day Britain was ruled by a narrow oligarchy, whereas by the 1870s, although corruption had not been eliminated, its scope had been very much reduced by reforms such as the extension of the franchise, secret voting and competitive examinations for the civil service. The extension of the franchise to include the working classes a process started in the 1867 Reform Act and extended in 1884 – placed socialism much higher on the political agenda than it could ever have been in the days of Smith and Bentham. Mill and Marx, in radically different ways, showed that the Smithian structure, modified by Ricardo, could still be used in this changed environment.

However, although classical theory proved adaptable, it was becoming outdated. Even Mill had no analytical tools suitable for tackling problems of monopoly. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, problems of big business became more and more prominent, especially in Germany and the United States. Competition between industrial nations meant that free trade could not be taken for granted in the way that it had been as late as the middle of the century. Above all, real wages had, at least since the 1850s, risen substantially, with the result that the Malthusian population theory, which underlay the whole of classical economics, was becoming hard to defend. On top of this, Romantic critics of economics, such as Ruskin, were questioning the value judgements on which the subject was based. Thus by the 1860s the confidence in the subject that had enabled Senior to describe the Great Exhibition of 1851 as a triumph of political economy had dissipated.