The central figure in early-twentieth-century work on money and the business cycle was the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell. In Interest and Prices (1898) and his Lectures on Political Economy (1906) he developed a theory of the relationship between money, credit and prices – his so-called ‘cumulative process’. Wicksell's theory was based on the theory of capital developed by the Austrian economist (and student of Menger) Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1914), in which the rate of interest is essentially the price of time. There are two sides to this coin. If someone is receiving an income, she has a choice to make. She can spend it on consuming goods and services immediately, or she can save it in order to be able to consume goods at a future date. The way people save is to buy financial assets, thereby lending income to someone else, and in return for this they receive interest. The higher the rate of interest, the more future consumption can be ‘bought' by deciding to save rather than to consume now. If the rate of interest rises, people have a greater incentive to postpone their consumption by saving part of their income.

The other side of the coin is investment. Businesses have to choose between investing in production processes that yield revenues very quickly and investing in other processes that are more productive but take longer to yield revenue. For example, the owner of a vineyard can choose whether to sell grapes immediately after the harvest or to ferment them and produce wine. Having produced the wine, there is then a choice of how long to store it. If the wine is allowed to mature, it will become more valuable. Wicksell followed Böhm-Bawerk in assuming that ‘long' processes of production (ones which take a long time to yield a revenue) will be more productive than ‘short' processes. However, because resources are committed for longer, such processes will require more capital. This means that, if the rate of interest rises, long processes of production will become more expensive relative to shorter ones.

The rate of interest, therefore, influences consumers' decisions about whether to consume goods now (using short processes) or in the future (using long processes), and also influences producers' decisions about whether to invest in processes that will produce goods now or in the future. A rise in the rate of interest will cause a rise in saving, as consumers decide it is worth postponing more consumption, and a fall in investment, as producers move towards shorter production processes. Wicksell argued that there will be some rate of interest at which these two types of decision are balanced. This is his ‘natural' rate of interest. At the natural rate of interest, the amount that consumers wish to lend is exactly equal to the amount that producers wish to borrow in order to finance their investment: there is inter-temporal equilibrium.

This part of Wicksell's theory drew on Böhm-Bawerk. The next stage was to introduce a banking system that created credit. The rate at which banks lent money was the ‘market' or ‘money' rate of interest. The cumulative process arose when the market rate of interest, for some reason, fell below the natural rate. Businesses would increase their investment, borrowing from the banking system the funds that they could not obtain from savers. The increase in investment would cause an increase in demand for resources, with the result that prices would be bid up. At the same time, the increased supply of credit would enable purchasers to pay these higher prices. Wicksell went on to show that, in what he called a pure credit economy, where goods were bought and sold using only bank money, not gold and silver, this process could continue indefinitely. As long as the market rate of interest was lower than the natural rate, prices would continue to rise. (Conversely, if it were higher than the natural rate, prices would fall indefinitely.) This was his cumulative process. If the country concerned were on a gold standard, the process would be brought to an end when the banks began to run out of gold reserves. This would force them to raise interest rates and cut back their lending, bringing the process to a halt.

Wicksell held a ‘real' theory of the business cycle, in the sense that he believed that the cycle arose because of changes in the natural rate. For example, inventions that raised productivity would cause the natural rate to rise, as would wars that destroyed resources. But the interest rate would not respond immediately to such changes, the result being that cumulative rises and falls in prices would be initiated. Furthermore, the quantity of currency (gold) played a purely passive role in the process. The active element in the system was the banking system. There was no fixed link between the volume of credit and the supply of currency. Despite this, however, Wicksell did not consider himself as a critic of the quantity theory but as elaborating on it, showing how changes in the quantity of money changed prices.

Though the basic theory was simple, there were several serious problems with it. Two of these were particularly important for subsequent developments. The first concerned the use of the Austrian theory of capital to determine the natural rate of interest. Though the notion of a period of production is an appealing one, capturing the insight that capital is associated with taking time to produce goods, it is riddled with technical problems. There may be no clear link between the period of production and the rate of interest. A fall in the rate of interest may cause the period of production to rise or fall, with damaging consequences for the notion of inter-temporal equilibrium. The second major problem can be explained by noting that the natural rate of interest is the rate of interest at which (i) savings equal investment, (2) there is no new credit being created, and (3) prices are constant. In general, however, it is not clear that all three conditions will be satisfied at the same rate of interest. For example, in a growing economy, stable prices will require an increasing quantity of credit to finance the growing volume of transactions. This means that some credit creation, resulting in an inequality of saving and investment, may be compatible with price stability. In addition, if productivity is rising, equality of the money and real rates of interest will lead to falling prices.

Wicksell was aware of these problems, and carefully made assumptions that avoided them. His successors, however, responded to them in very different ways and, as a result, developed very different theories. To understand these, it is necessary to understand some of the economic events of the inter-war period.

The inter-war period was one of unprecedented economic instability. By the end of the First World War the dominant country in the world economy was clearly the United States. Like much of the world, it experienced a brief boom in 1920, followed by a very sharp depression, when prices fell and unemployment rose, in 1921. For the rest of the 1920s, however, the country experienced unparalleled industrial growth and prosperity. Unemployment remained low, electricity spread throughout the country, with profound effects for industry and domestic life, the number of cars registered rose from 8 million to 23 million, and there was an enormous amount of new building. At the end of the decade, Herbert Hoover, as a presidential candidate, claimed that the country was close to triumphing over poverty. The stock market boomed, and investors thought that prosperity would continue indefinitely. Few other countries fared as well as the United States (Japan and Italy were unusual in growing faster), but most countries prospered during the 1920s. Countries that stagnated included many in eastern Europe (including the newly formed Soviet Union), Germany and Britain.

Britain, like the United States, shared in the immediate post-war boom and the depression that followed. Prices rose by 24 per cent in 1920, and then fell by 26 per cent in 1921. Unemployment rose to 15 per cent of the workforce in 1921, and remained around 10 per cent for the rest of the decade. Prices fell, and industry stagnated. In 1925 – by which time US industrial production had risen to 48 per cent above its 1913 level – British industrial production was still 14 per cent below its level in 1913. The British economy had not recovered from the effects of the war.

However, the most spectacular examples of instability in the 1920s were in central Europe. In Germany, prices nearly doubled in 1919, and then more than trebled in 1920. After a brief respite in 1921, they then rose by over 1,600 per cent in 1922. In 1923 the currency completely collapsed. Prices rose by 486 million per cent – true hyperinflation. The value of the mark fell so far that the exchange rate, which had been US$I = 4.2 marks in 1913, fell to US$I = 4.2 billion marks. At the same time, unemployment rose to almost 10 per cent of the workforce. At the end of the year a new currency was issued, and prices rose gently for the rest of the decade. However, unemployment remained high, averaging over 10 per cent.

The Great Crash came in October 1929. In the United States, the downturn which had begun earlier that summer developed into an enormous slump in which industrial production, agricultural prices and world trade collapsed. Unemployment rose dramatically. In the next few years US industrial production fell to a little over half of its 1929 level, and unemployment rose to over 25 per cent of the labour force. It was not until 1937 that unemployment fell below 15 per cent, and then a further slump pushed it back up to 19 per cent. Similar levels of unemployment were recorded in many other countries. In 1933, unemployment was 26 per cent in Germany, 27 per cent in the Netherlands, 24 per cent in Sweden, 33 per cent in Norway, and 21 per cent in Britain. It was a problem affecting the entire capitalist world, and it persisted throughout the 1930s. In some countries, such as the Netherlands, unemployment remained at similar levels right up to 1939. In others, such as Britain and Sweden, unemployment recovered slowly to just over 10 per cent by the end of the decade. Only in Germany, under the Nazi regime brought to power by the crisis in 1933, was unemployment brought down to low levels (2 per cent by 1938).

Almost inevitably, these events attracted the attention of the world's economists. Though the underlying causes of the period's economic instability remained controversial, it became clear to most economists that the dominant theories of the pre-war period were inadequate to explain what was going on. Most important, it became clear that it was necessary to be able to offer a coherent theory of the level of economic activity. Changes in the level of industrial production and unemployment, on both of which statistics were beginning to be calculated during the 1920s, had become too important to be regarded as a secondary phenomenon. It was also clear that, in some way, changes in the level of economic activity were linked to money and finance. The German case, where hyperinflation completely destroyed the value of the currency and rendered normal economic activity virtually impossible, may have been an extreme example, but it was a very important and salutary one. It was also hard not to look for a connection between the financial activities that caused boom and bust in the US stock market and the unprecedented depth of the following depression.

In addition, behind all this was a world economy that was very different from before the war. In particular, intergovernmental debts, almost unknown before 1914, were a major problem. European governments had borrowed heavily from each other and, in particular, from the United States. They sought to recover these costs from Germany through extracting reparations. There was, and is, scope for disagreement over the role played by reparations in the German hyperinflation, or how far the causes of the Crash and the Depression should be sought in Germany and eastern Europe. There was, however, no doubt that the new situation in international finance was an integral part of the world trading system that, after 1929, proved to be so fragile.

The different experiences of the European countries and the United States meant that, though the economists involved formed a single community in the sense that Europeans drew on American literature, and vice versa, their perspectives were different. In the United States it was natural throughout the 1920s to be optimistic about the prospects for the long-term stability of the economy. When the Great Depression came, it was natural to see it, at least at first, as an unusually bad cyclical downturn. In contrast, by the end of the 1920s British economists had come to see unemployment as a structural problem, not a cyclical one. There was a further difference in that, whereas Britain had not experienced financial panic and bank failures since the 1860s, these were still regular events in the United States. The Federal Reserve System, established in 1913, had yet to establish a reputation as lender of last resort comparable with that of the Bank of England. The result was that Americans were much more interested in finding policy rules that would alleviate the cycle. The situation was different again on the Continent. In Germany, for example, memories of the hyperinflation of 1922–3 remained long after the event.

The main proponents of the Austrian theory of the business cycle were Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) and Friedrich von Hayek (1899–1992). Both were from Vienna, but Hayek moved to the London School of Economics in 1931. Mises's main ideas were set out in The Theory of Money and Credit, first published in 1912, but they came into their own only in the 1920s and early 1930s. They were apparently vindicated by the German hyperinflation and the sudden collapse of the American economy after the greatest boom in its history.

Mises and Hayek started from Wicksell's theory, but developed it into a monetary theory of the cycle. They placed great stress on the Austrian theory of capital underlying Wicksell's natural rate of interest, and argued that monetary policy was liable to interfere in the normal working of credit markets. In a credit economy, not constrained by the gold standard, bankers would be under pressure to keep interest rates low. If they yielded to this pressure, and the market interest rate fell below the natural rate, this not only would cause inflation but would also interfere with the inter-temporal allocation of resources. What would happen was that low interest rates would cause entrepreneurs to invest in production processes that were too long – too capital-intensive – compared with what was appropriate given the level of saving. Because investment in capital goods was too high, capital-goods prices would rise relative to the prices of consumer goods. This would cause a problem because, although producers were shifting resources into processes that would yield returns only in the future, consumers were given no incentive to postpone their consumption. The result would be excessive demand for consumer goods.

As long as credit continued to expand, such a situation might continue for a long time, but eventually the credit expansion would have to end. When the credit expansion ended, interest rates would rise and the result would be a fall in output and a rise in unemployment. The reason would be that the long, capital-intensive production processes that were started when interest rates were low would suddenly become unprofitable and be closed down. The resources put into them (embodied in stocks of unfinished goods, equipment and so on) would typically be unsuitable for the newly profitable shorter processes, and would lie idle.

Mises and Hayek used this theory to condemn the use of expansionary monetary policy as a means of raising the level of economic activity. It might be possible, they argued, to use credit expansion to sustain a boom, but the result would be that, when it came, the eventual collapse would be greater. This fitted the American experience of the 1920s. An exceptionally long boom, sustained by massive credit expansion, had been followed by an equally massive depression. According to Mises and Hayek, this was inevitable. They advocated non-intervention and a policy of ‘neutral' money whereby the rate of interest would be set so as to keep the level of money income constant. Even in a depression as severe as that of 1929–32, it would be foolish to lower interest rates and expand the money supply, for it was important that the structure of production be allowed to adjust.

In contrast, the Stockholm school – Erik Lindahl (1891–1960), Erik Lundberg (1907–89), Gunnar Myrdal (1898–1987) and Bertil Ohlin (1899–1979) – developed Wicksell's theory in a completely different way. They argued that technical problems with Austrian theory of capital meant that it was impossible to argue that the natural rate of interest was determined by the productivity of capital. Such a concept was impossible to define. Instead, they took up the idea, previously developed by Irving Fisher, that capital should be understood as the value of an expected stream of income. The demand for loans would depend on expectations about the future. This perspective led them to take issue with the idea of neutral money, claiming that equilibrium between saving and investment was compatible with any rate of inflation. The reason was that, so long as it was correctly anticipated, the rate of inflation could be taken into account in all contracts for the future and therefore need not have any effect. It was unexpected changes in prices that would disrupt the relationship between saving and investment.

Members of the Stockholm school were therefore led to abandon two of the ways in which Wicksell defined the natural rate of interest and to focus on the relationship between saving and investment. They analysed this through investigating dynamic processes, tracing the interaction of incomes, spending, prices and so on from one period to the next. Among other problems, they analysed how it was that a discrepancy between savers' and investors' plans (termed an ex ante imbalance between saving and investment) could be turned, by the end of the relevant period (ex post), into an equality. For the most part the processes they analysed started from a situation of full employment, with the result that they analysed cumulative processes similar to Wicksell's. However, they took very seriously the idea that prices and wages might be very slow to change, with resulting consequences for output. They also investigated processes that started with a situation of unemployment, and were able to show how lowering interest rates might lead to a prolonged increase in production.

One reason why the Swedish economists did not reach a more definite view of the cycle was that their theory was very open-ended. They explored a series of related models, showing that a wide range of outcomes was possible. This fitted in with their very pragmatic attitude towards policy. They were open to the idea of using not only monetary policy but also government spending to reduce unemployment. This was in marked contrast to the rigid liberalism of the Austrians.

Leaving aside Hayek and his followers at LSE, British thinking on money and the business cycle had its roots in the work of Alfred Marshall. His first work on the problem was in The Economics of Industry (1879), written jointly with Mary Paley Marshall and strongly influenced by J. S. Mill. In a period of rising demand, confidence is high, the level of borrowing increases, and prices rise. At some point, however, lenders reassess the situation and start to cut back on their loans, with the result that interest rates rise. This precipitates a fall in prices as confidence falls. Businesses are forced to sell their stocks of goods, causing further falls in prices. The reason why this leads to fluctuations in output is that prices fluctuate more than costs, in particular wages and fixed costs. In the boom, prices rise faster than costs, causing firms to increase their production. After the crisis, prices fall more rapidly than costs, causing businesses to reduce output.

The main factor underlying this account of fluctuations in economic activity is confidence. Referring to the depression stage, Marshall and Marshall wrote:

The chief cause of the evil is want of confidence. The greater part of it could be removed almost in an instant if confidence could return, touch all industries with her magic wand, and make them continue their production and their demand for the wares of others… [The revival of industry] begins as soon as traders think that prices will not continue to fall: and with a revival of industry prices rise.1

Crises occur because businessmen, including those who supply credit, become overconfident, causing expansions to go on too long.

Over the following forty years, Marshall integrated into his account of the cycle a clear statement of the quantity theory of money and the distinction between real and nominal interest rates. However, the essentials of the theory remained unchanged. In particular he continued to argue that fluctuations in demand caused prices to fluctuate. Output changed only when prices and costs moved in such a way as to raise or lower profits. This was the framework underlying the work of his followers. The most important of these were Arthur Cecil Pigou, Marshall's successor as professor at Cambridge, Dennis Robertson (1890–1963), Ralph Hawtrey (1879–1975) and John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946). The theories they developed were all firmly rooted in the Marshallian tradition, emphasizing the role of expectations and errors made by businessmen in explaining the cycle. However, this tradition encompassed a great variety of views.

Hawtrey, whose most influential book was Currency and Credit (1919, revised in 1927 and 1950), held a purely monetary theory of the cycle. His theory had several distinctive features, but the most important was his emphasis on what he termed ‘effective demand' – the total level of spending, including both consumers' spending and investment. He argued that changes in the money supply would affect the level of effective demand and that, because prices and wages were slow to respond to this, output would change. The existence of time lags in the various processes involved meant that expansions and contractions of credit would go too far, with the result that there would be cycles, not steady growth.

In contrast, Robertson, in his Theory of Industrial Fluctuations (1915), explained the cycle in terms of shocks caused by inventions that raised productivity. Following Aftalion, Robertson used the gestation lag (the time that elapses between undertaking an investment and obtaining the output) and other features of investment to explain why such shocks would produce a cycle. A decade later, in Banking Policy and the Price Level (1926), his emphasis shifted. Though he did not abandon the idea that inventions caused fluctuations in economic activity, he switched to arguing that, because of monetary factors, cyclical fluctuations were much larger than they needed to be. Suitable banking policy could mitigate this, but, unlike the Austrians, he did not believe that this could completely stabilize the economy.

Pigou's work is revealing because it illustrates the way in which British economists reacted to the persistence of high unemployment during the 1920s. He published a theory of the business cycle, first in Wealth and Welfare (1912) and later in A Study of Industrial Fluctuations (1927). Like several of his contemporaries, he emphasized the importance of entrepreneurs' expectations of profit, and, like Hawtrey, he stressed the role of demand. If demand were sufficiently low, there might be no positive wage rate at which entrepreneurs would wish to employ the whole labour force. However, in discussing the cycle, Pigou was thinking primarily of cycles experienced before 1914. He did not think of himself as explaining the unemployment experience of the 1920s, for which a different approach was required. To explain this, he focused much more on wages and the labour market, publishing The Theory of Unemployment in 1933. This was very Marshallian in discussing the problem in terms of supply and demand for labour.

One of the most orthodox Marshallians in the early 1920s was Keynes. He had achieved celebrity status in 1919 when he resigned from the Treasury team at the Versailles peace conference to write his best-selling book The Economic Consequences of the Peace. This provided a devastating critique of the peace treaty and of the way in which the negotiations were conducted. He argued not only that it was immoral for the allied governments to demand high reparations payments from Germany, but also that Germany would not be able to pay what they were demanding. Then, in 1923, he turned his attention to monetary policy and the cycle in his Tract on Monetary Reform. The analytical framework he adopted was Marshall's version of the quantity theory, though, in common with his Cambridge colleagues, he emphasized the role of expectations. Because the demand for cash balances (the key element in Marshall's quantity theory) depended on expectations about the future, it was liable to change at any time. In the absence of suitable changes in the money supply, the result would be fluctuations in the price level. Strict proportionality of the price level to the money supply was true only in the long run. Referring to the notion that doubling the money supply would double the price level, Keynes argued:

Now ‘in the long run' this is probably true. But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean is flat again.2

There were also disturbances caused by changes in foreign prices, which were linked to British prices via the exchange rate.

This posed a dilemma for the monetary authorities. If they stabilized the domestic price level (increasing the supply of money when demand for it rose, and contracting it when demand fell) the result might be changes in the exchange rate. Alternatively, if they chose to stabilize the exchange rate (as Britain was then doing by trying to return to the gold standard) the result would be instability of domestic prices. Keynes argued two things. The first was that the evils of falling prices were worse than the evils of either rising prices or changing exchange rates. In the context of the early 1920s, when prices were being pushed downward as the government sought to raise the exchange rate to its pre-war value, this led Keynes to oppose returning to the gold standard. The second was that the authorities had to make a decision about the exchange rate: it was necessary for them to recognize that the economy had to be managed and that they could not claim that the price level was determined by forces beyond their control:

In truth, the gold standard is already a barbarous relic. All of us… are now primarily interested in preserving the stability of business, prices and employment, and are not likely, when the choice is forced on us, deliberately to sacrifice these to the outworn dogma… of £3.17s 10½d per ounce [the pre-war exchange rate in terms of gold]. Advocates of the ancient standard do not observe how remote it now is from the spirit and the requirements of the age. A regulated non-metallic standard has slipped in un-noticed. It exists. Whilst the economists dozed, the academic dream of a hundred years, doffing its cap and gown, clad in paper rags, has crept into the world by means of the bad fairies – always so much more potent than the good – the wicked ministers of finance.3

He developed this idea, that policy-makers had to take conscious decisions about managing the economy, in The End of Laissez Faire (1926).

During the 1920s Keynes worked closely with Robertson and other Cambridge economists on problems of money and the cycle, and in 1930 he published A Treatise on Money, intended to be his definitive treatment of the problem. The core of his analysis was thoroughly Wicksellian. He defined saving and investment in such a way that they need not be equal. They would be equal only if ‘windfall profits' (profits over and above the normal level of profits necessary to keep firms in business) were zero. He then used the relationship between saving and investment to analyse the impact of monetary policy on the level of activity. For example, a low interest rate would cause a rise in investment and a fall in saving. This would raise prices and windfall profits, causing firms to increase production. Conversely, if the interest rate rose, investment would be less than saving, windfall profits would become negative, the price level would fall, and output would contract. As with his previous work, he emphasized the role of expectations in this process. The link between money and interest rates would depend on the level of ‘bearishness' or the degree to which people were worried about the future. If bearishness were high, for example, people would want to hold more money as a hedge against future uncertainty, with the result that an increase in the money supply would be needed to prevent interest rates from rising.

In 1931 Hayek arrived at LSE, and he and Keynes clashed over the theory of the cycle. Their theories were both in the Wicksellian tradition, but they reached diametrically opposed conclusions about the role of monetary policy. They completely failed to understand each other in what was a heated dispute.

For reasons mentioned earlier, there arose a distinctive American tradition in monetary economics. The 1920s were a time of immense prosperity, and the Federal Reserve System was only beginning to work out how it should conduct its operations. The result was that, unlike in Europe, American economists paid great attention to the question of designing rules to govern the conduct of monetary policy. However, although there was widespread support for using monetary and fiscal expansion to combat the depression after 1929, without the strong opposition to such policies associated with Mises and Hayek, there was no consensus on any underlying theory. In the words of a recent commentator:

It is difficult to think of any explanation for the event itself [the Great Depression], or any policy position regarding how to cope with it, that did not have its adherents. Moreover, virtually every theme appearing in the European debates… found an echo somewhere in American discussions.4

The variety of ideas discussed means that it is possible to do no more than outline a few of them.

The most prominent exponent of the quantity theory throughout this period was Irving Fisher. He expressed great scepticism about the existence of anything that deserved to be termed a business cycle. Prices fluctuated, which meant that sometimes they would be high and sometimes low (he used the phrase ‘the dance of the dollar’). That was not enough to make a cycle, which implied a regular pattern of cause and effect. What was needed was to stabilize prices, which was why he was active in organizing the Stable Money League in 1921 (which subsequently developed into the National Monetary Association and the Stable Money Association). He was also influential, during the 1920s, in promoting legislation to require the Federal Reserve System to use all its powers to promote a stable price level. Consistent with this, in the early 1930s he argued for a series of schemes to raise the price level, thereby helping to restore stability. He continued to argue that the idea of a cycle was a myth, but he produced several theories that might explain how a recession could be so severe. The most prominent was his debt-deflation theory. According to this, falling prices raised the real value of debts, forcing debtors to cut back on their spending, which forced prices still lower, worsening the situation.

At the other extreme were those who argued that there was no link between monetary policy and the price level, justifying this with a version of the real-bills doctrine. They argued that prices normally changed for non-monetary reasons, and that, if the money supply was not allowed to expand to accommodate this, the velocity of circulation would rise instead. Provided the banking system lent money only for proper commercial transactions, the result would not be inflationary. When the Great Crash came, such economists argued that credit had been overextended (a view not unlike that of the Austrians) and that no useful purpose would be served by monetary expansion. Thus Benjamin Anderson (1886–1949) wrote, ‘it is definitely undesirable that we should employ this costly [cheap money] method of buying temporary prosperity again. The world's business is not a moribund invalid that needs galvanizing by an artificial stimulant.’5

Austrian views were represented in America, but few economists took them up. Gottfried Haberler (1900–1997), who arrived in 1936, used Hayekian arguments about capital to explain why the Depression was more than a monetary phenomenon and would last a long time. Schumpeter, who went to Harvard in 1932, did not adopt a Hayekian approach. His explanation of the Depression was that it was so severe because it marked the coincidence of a number of cycles, all of different length. There was the Kondratiev long cycle (around forty years long), the Juglar cycle (around ten years long) and the Mitchell–Persons short cycle (around forty months long). These were cycles for which previous economists claimed to have found statistical evidence, and all of them turned down in 1930–31. This perspective was shared by Alvin Hansen (1887–1975). Hansen added the hypothesis that this coincidence of the three cycles came on top of a long-term decline in prices caused by a world shortage of gold and an accumulation of gold stocks in France and the United States. Both Schumpeter and Hansen were sceptical about the possibility of using monetary expansion to get out of the Depression. The Depression might be painful, but it paved the way for improved production methods and higher standards of living.

Another strongly anti-quantity-theory position was that of the underconsumptionists, most prominent of whom were William Truffant Foster (1879–1950) and Waddil Catchings (1879–1967). Foster and Catchings argued that monetary expansion would stimulate activity only if it stimulated consumers' spending. Any other form of monetary expansion, even if linked to rises in government spending, would have no effect. J. A. Hobson (1858–1940), a British economist who had first put forward underconsumptionist theories in 1889, and who had coined the term ‘unemployment' in 1896, was widely read.

Other economists adopted a more moderate position. One of the most influential of these was Allyn Young (who had many students while at Harvard), who was in turn strongly influenced by Hawtrey's Currency and Credit. Young argued that monetary policy was needed to stabilize business, but that this required the establishing of sound traditions, not the imposition of a simple rule such as Fisher and others were proposing. He also supported the use of government spending to alleviate the cycle. He was able to show, through a detailed statistical analysis, that bank reserve ratios fluctuated greatly with seasonal movements of funds between New York and the rest of the country. Following Hawtrey, he emphasized the instability of credit – something that a strict quantity theorist would not accept. Young died in 1929, but one of his students, Laughlin Currie (1902–93), applied Hawtrey's theory to the Depression, finding evidence that monetary factors were important. He used statistics on the behaviour of a range of measures of the money supply to argue that the Federal Reserve System could have prevented much of the collapse had it chosen to do so. The claim that it was powerless was not borne out by the evidence.

During this period the economist most firmly associated with empirical research on the business cycle was Wesley Clair Mitchell, director of the National Bureau of Economic Research. He popularized the notion of the cycle, and sought to document, statistically, exactly what happened during cycles. He was sceptical about theories that sought to explain the cycle in terms of a single cause, preferring to analyse individual cycles in detail. However, he was convinced that its causes lay in what Veblen had called the ‘pecuniary' aspects of economic life. The cycle could not be divorced from its monetary aspects, though these were not all that mattered. When the Depression came in 1929, Mitchell argued that the only puzzle was why it was so severe and so prolonged. His explanation was that several shocks happened to occur on top of each other: depression in agriculture, the after-effects of excessive stock-market speculation, political unrest, increased tariff barriers and so on. The effects of these shocks were exacerbated by changes that reduced the powers of the economic system to stabilize itself. People were buying more semi-durable goods (such as cars and electrical appliances), with the result that if incomes fell they could more easily reduce their spending. There was less self-sufficiency in agriculture, and large firms were increasingly reluctant to cut prices when demand fell. Mitchell's response to this was that laissez-faire was proving inadequate and that greater national planning was required. However, beyond supporting public-works policies and the dissemination of information and forecasts, he did not work out plans in any detail.

In the early 1930s a number of economists, with very different theoretical views, endorsed the idea of requiring the banking system to hold 100 per cent reserves. Supporters of such a rule included Currie, Paul Douglas (1892–1976), Fisher, and Henry Simons (1899–1946), all for different reasons. Currie supported the rule on the grounds that, if the government issued the entire money supply, this would provide the government with the best possible control over it. It would be easy to expand or contract the money supply as much as was required. In contrast, Simons supported it because he regarded ‘managed currency without definite, stable, legislative rules [as] one of the most dangerous forms of “planning”’.6 In the ‘Chicago plan' in 1933, Simons argued for 100 per cent reserves combined with a constant growth rate of the money supply and a balanced-budget rule for government spending. This, he believed, would stabilise prices and restrain government spending. However, by 1936 he had come round to the view that this rule would merely lead to variability in the amount of ‘near monies' (assets that do not count as money but which can be used instead of money). As a result, he moved towards setting price stability as the goal of policy.

The history of the support for 100 per cent money illustrates the way in which, even though there was enormous diversity within American monetary economics at this time, there were also great overlaps. Simons moved from a money-growth rule towards Fisher's price-stability rule. At the same time, Fisher took up the Chicago position of 100 per cent money. Though the case for 100 per cent money was based on a monetary interpretation of the Great Depression, later associated with Simons and his fellow Chicago economist Milton Friedman (see pp. 295–7), this interpretation originated with Currie. He worked within the theoretical framework laid down by Hawtrey and developed by Young, his teacher at Harvard. Other overlaps include the views on monetary policy shared with Austrian economists and the advocates of the real-bills doctrine.

In his early work, in the 1920s and before, Keynes was a quantity theorist in the Marshallian tradition. In A Treatise on Money he moved away from this to a perspective closer to Wicksell's, focusing on the links between money, saving, investment and the level of spending. However, he still considered the price level as central to the whole process. Changes in spending led to changes in prices and profits, thereby inducing businesses to change their production plans. This raised a technical problem at the heart of his analysis. He developed a theory to explain changes in prices and profits on the assumption that output did not change. He then used that theory to explain why output would change. This was unsatisfactory, and soon after the book was published he began to rethink the theory with the help of younger colleagues at Cambridge. The results of this process of rethinking were eventually published in 1936 as The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

Perhaps the crucial transition made in the General Theory was towards thinking in terms of an economy where the first thing to change in response to a change in demand was not prices but sales. If demand fell, firms would find that their sales had fallen, and that their inventories of unsold goods were higher than they had anticipated. They would then adjust their production plans. One stimulus to this way of thinking came as a result of discussions on employment policy in the 1920s and early 1930s. It was commonly agreed that public-works expenditure could raise employment, but there was no basis for working out by how much employment would rise. This problem was tackled by Richard Kahn (1905–89), who in an article published in 1931 put forward the idea of the multiplier. (This idea was also found in Hawtrey's work in the 1920s, though not named as such.) The question he asked was the following. If an additional worker is employed on a public-works scheme, and that worker buys goods that need to be produced by other workers, how many additional workers will end up being employed? He found that the mathematics of the problem yielded a clear answer, and that it depended on how much of the newly generated income was spent on consumption goods. In a subsequent article a Danish economist, Jens Warming (1873–1939), pointed out that if a quarter of income were saved, a rise in investment of 100 million would lead to a rise in income of 400 million. Saving would rise by 100 million – exactly enough to finance the initial increase in investment. The size of the multiplier (the ratio of the rise in income to the initial investment) was determined by the fraction of income saved.

The multiplier provided Keynes with a link between investment and the level of demand in the economy. He based this link on the notion of what he called the ‘fundamental psychological law' that, when someone's income rises, his or’ her consumption rises, though by less than the full amount. He labelled the ratio of the rise in consumption to the rise in income the ‘propensity to consume’. He then needed a theory of investment. He adopted an approach similar to Fisher's, arguing that the level of investment depended on the relationship between the expected return on investment (which he termed the ‘marginal efficiency of investment’) and the rate of interest. For a given marginal efficiency of investment, a rise in the interest rate would cause a fall in investment and vice versa. However, although he talked of a negative relationship between investment and the interest rate, Keynes placed equal emphasis on the role of expectations and the importance of uncertainty in influencing investment.

He analysed the relationship between uncertainty and investment through arguing that the marginal efficiency of capital depended on what he called ‘the state of long-term expectation’. This covered all the factors that were relevant to deciding the profitability of an investment, including the strength of consumer demand, likely change in consumers' tastes, changes in costs, and changes in the types of capital good available. All these had to be evaluated over the entire lifetime of the investment, and were matters about which investors knew little.

The outstanding fact is the extreme precariousness of the basis of knowledge on which our estimates of prospective yield have to be made. Our knowledge of the factors which will govern the yield of an investment some years hence is usually very slight and often negligible. If we speak frankly, we have to admit that our basis of knowledge for estimating the yield ten years hence of a railway, a copper mine, a textile factory, the goodwill of a patent medicine, an Atlantic liner, a building in the City of London amounts to little and sometimes to nothing.7

Faced with this uncertainty, investment would depend not on rational calculation of future returns, but on the state of confidence.

In practice, expectations are governed by conventions – in particular the convention that ‘the existing state of affairs will continue indefinitely, except in so far as we have specific reasons to expect a change’.8 The implication of this is that, because expectations are based on conventions, they are liable to change dramatically in response to apparently minor changes in the news. The situation is made worse in a world, such as Keynes saw around him, where investment policy is dominated by professional speculators. Such people are not trying to make the best long-term decisions but are concerned with working out how the stock market will move, which means they are forever trying to guess how other people will react to news. The result is great instability.

The other determinant of investment is the rate of interest. To explain this, Keynes introduced the idea that money is required not only to finance transactions in goods and services but also as a store of value. People may hold money because they are uncertain about the future and wish to be able to postpone their spending decisions, or because they expect holding money to yield a better return than investing in financial assets. (If the price of bonds or shares falls, the return may be negative – less than the return from holding money.) This was the theory of liquidity preference, which led Keynes to argue that the demand for money would depend on the rate of interest. He even claimed that, under some circumstances, the demand for money might be so sensitive to the rate of interest that it would be impossible for the monetary authorities to lower the rate of interest by increasing the money supply – the liquidity trap.

When put together, these three components – the propensity to consume, the marginal efficiency of investment, and liquidity preference – formed a theory of output and employment. For example, given liquidity preference, a rise in the money supply would cause a fall in the rate of interest. Given the state of long-term expectations, this would cause a rise in investment and hence a rise in output and employment. It was a theory in which output was determined by the level of effective demand, independently of the quantity of goods and services that businesses wished to supply.

Keynes's strategy in developing his theory was to take the wage paid to workers as given. Towards the end of the book he considered what would happen if wages were to change, and advanced a variety of arguments about why changes in wage rates would have no effect on employment. Cutting wages would not raise employment unless doing so raised the level of effective demand. He went through all the ways this might happen, concluding that this was very unlikely.

Keynes presented his book as an assault on an orthodoxy – the ‘classical' theory that, he claimed, had dominated the subject for a hundred years, since the time of Ricardo. According to this orthodoxy, the level of employment was determined by supply and demand for labour, and if there were unemployment it must be because wages were too high. The ‘classical' cure was therefore to cut wages. If wages were flexible, the only unemployment would be frictional (associated with turnover in the labour market) or structural (caused, for example, by the decline of certain industries). The classical theory was also characterized by Say's Law, according to which there could be no general shortage of aggregate demand. Keynes went on to argue that the classical theory was a special case, and that his own theory was more general. ‘Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience.’9

This dramatic claim, together with Keynes's celebrity status, was one reason why the General Theory made such an enormous impact on its publication. It appealed in particular to young economists who relished the prospect of overthrowing the orthodoxy supported by their elders. Paul Samuelson (see pp. 258–9), perhaps the most prominent Keynesian in the early post-war period, and a student at Harvard when the book came out, compared Keynesian economics to a disease that infected everyone under the age of forty, but to which almost everyone over forty was immune. In so far as the reaction of the older generation was generally critical, Samuelson's point appears justified. Older economists found fault with Keynes's logic and took issue with his claim to be revolutionizing the subject. There was, however, much more to the Keynesian revolution than this.

For economists who read the General Theory for the first time in the late 1930s or the early 1940s, it was a difficult book. For some of the older generation, the reason lay in the mathematics – by the standards of the time, it was a mathematical book. There were, however, deeper reasons. The first was that Keynes spoke of a classical orthodoxy, but, as will not be surprising in view of the range of theories surveyed in this chapter, it was not clear just what the classical orthodoxy was. The second difficulty was that the General Theory contained many lines of argument, and it was not clear which ones mattered and which could be left to one side. This was a problem not only for non-economist reviewers, many of whom said that they awaited the judgement of Keynes's professional peers, but also for economists who read the book. Economists, therefore, had to make sense of what Keynes was saying.

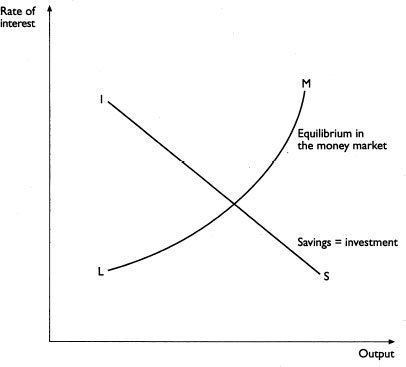

A number of economists tried to make sense of Keynes's central argument by translating it into a system of equations. The first was David Champernowne (1912–2000), who, in an article published in 1936, within months of the General Theory, reduced Keynes's system to three equations. Over the next few months, other economists worked with similar sets of equations, trying to use these to explain what Keynes was saying. The most influential of these was John Hicks (1904–89). Hicks's equations were very similar to those developed by Champernowne and others, but he managed to reduce Keynesian economics to a single, simple diagram showing relationships between output and interest rate. The LM curve showed combinations of output and the rate of interest that gave equilibrium in the money market, and the IS curve showed combinations that made savings equal to investment. Hicks then argued that, if the LM curve were fairly flat, Keynes was right – increases in government spending would shift the IS curve to the right, and output would rise. On the other hand, if the LM curve were vertical, shifts in the IS curve caused by changes in government spending would simply change the rate of interest, leaving output unaffected. Hicks provided a solution to the puzzle about what the differences between Keynes and the classics really were. His diagram also provided a valuable teaching tool, for students could learn how to manipulate the IS and LM curves to show the effects of a wide range of policy changes. The maze of pre-Keynesian business-cycle theory was apparently simplified into a single diagram.

Hicks's diagram was taken up by Hansen, who became the leading exponent of Keynesian ideas in the 1940s. He refined Hicks's diagram into what became known, after the labels attached to its two main

Fig. 4 Hicks's curves showing relationships between output and interest rate

components, as the IS–LM model. At the same time, other economists such as Franco Modigliani (1918–) and Don Patinkin (1922–97) continued the process of making sense of Keynes's theory. They translated it into mathematical models that made microeconomic sense, working out just what had to be assumed in order to get Keynesian results. Keynesian ideas also entered into the elementary textbooks, of which Samuelson's was the most successful. By the end of the 1940s, in a survey of contemporary economics organized by the American Economic Association to help with training returning servicemen, Keynes was far and away the most frequently cited author.

The myth of the Keynesian revolution, which Keynes himself propagated, is that Keynes overthrew something called ‘classical economics’. It is that he showed for the first time how changes in government spending and taxation could be used to stabilize the level of employment, thereby laying the foundations of modern macroeconomics. This, however, is a serious distortion of what happened. The literature of the 1920s and 1930s contained a wide range of approaches to macroeconomic questions by economists working in many countries, notably the United States, Britain and Sweden. That literature paid attention to problems of expectations – the relation between saving, investment and effective demand – and much of it supported the idea that both monetary policy and control of government spending might be needed to alleviate unemployment. The General Theory arose out of that literature and did not mark a complete break with what went before it. This resolves the puzzle of how, if the General Theory was as revolutionary as the myth suggests, Keynesian policies were being employed in several countries long before the book was published. Roosevelt's New Deal, for example, began in 1932.

The main reason why post-war macroeconomics was so different from pre-war monetary economics and business-cycle theory is that, from the late 1930s, macroeconomics began to be based, as never before, on working out the properties of clearly defined mathematical models. These include the mathematical models of Keynesian economics associated with Hicks and Champernowne, as well as the dynamic business-cycle models of Samuelson and Ragnar Frisch (see p. 248). This process affected not just macroeconomics, but also other branches of economics. The reason why Keynesian economics dominated the subject so completely is that it provided a framework that could be translated into a mathematical model that proved extremely versatile. In this sense, therefore, the outcome of the Keynesian revolution was the IS-LM model.10 Having said this, two important qualifications need to be made. The first is that, though it is arguable that the IS–LM model captures the central theoretical core of the General Theory, much is left out. This is an inevitable consequence of formalizing a theory. In the case of the General Theory, what was left out included Keynes's discussions of dynamics and of expectations. As a result, there are many economists who argue that Keynes's most important insights were lost, and that the IS–LM model represents a ‘bastard' Keynesianism, to use Joan Robinson's phrase. If we make the comparison between post-war economics and the entire business-cycle literature of the 1920s and 1930s, the amount that was forgotten appears even greater. One reason for this may be that, by the 1960s, many economists had (mistakenly) come to believe that Keynesian macroeconomic policies had made the business cycle a thing of the past.

The second, and perhaps more important, qualification is that, despite the triumph of Keynesianism (at least in its IS–LM version), the earlier traditions did not die out completely, even though they became marginalized. Hayek, for example, dropped out of mainstream economics, moving into what is usually considered political philosophy. In the 1970s, however, there was a resurgence of interest in his ideas. More significantly, the institutionalist tradition represented by Mitchell left an influential legacy. Hansen, though he presented himself as a Keynesian, was making arguments that can be traced back to what he was doing before the General Theory appeared. Even more significantly, the monetary economics of Milton Friedman lies squarely in the tradition established by Mitchell at the National Bureau, emphasizing the importance of detailed statistical work of a type very different from much modern econometrics. Friedman's influential Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (1963) (see p. 296) is very much in Mitchell's style, and his explanation of the Great Depression is similar to that offered by Currie in the early 1930s. It can also be argued that the ‘Chicago' view of monetary policy, with which Friedman has been so strongly associated, goes back via Simons to Currie, and through him to Hawtrey. Behind all this, however, the influence of Fisher, with his analysis of the rate of interest as the price linking the present and the future, is pervasive.