INTRODUCTION TO

STILL LIFES

Study your subject closely, and lightly sketch the simple shapes. (Notice, for example, that the pear is made up of two circles—one large and one small.) Once the basic shapes are drawn, begin shading with strokes that are consistent with the subjects’ rounded forms, as shown in the final drawings.

Pear

Drawing the Pear Start with two circles for the pear; next place the stem and the water drop. Begin shading with smooth, curving lines, leaving the highlighted areas untouched. Then finish shading and refine the details.

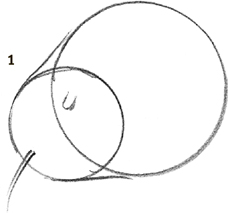

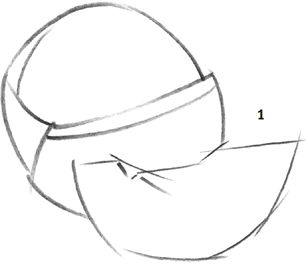

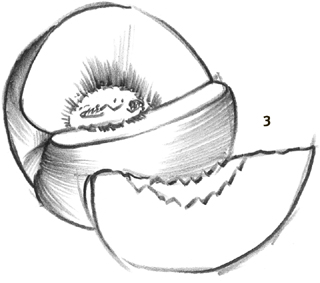

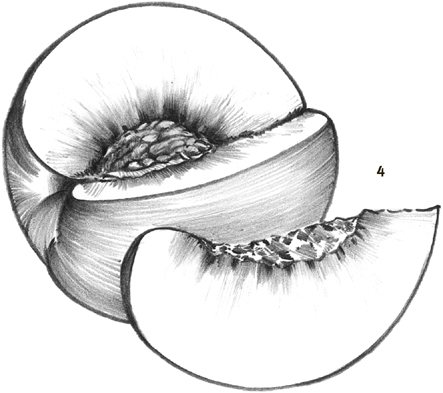

Peach

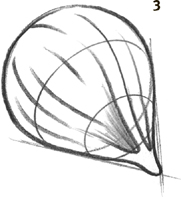

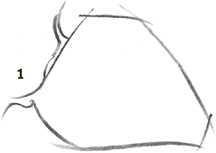

Drawing the Peach First draw the general shapes in step 1. Then, in step 2, place guidelines for the texture of the pit and the cavity on the slice. Begin shading the skin of the peach with long, smooth strokes to bring out its curved surface in step 3. Use a sharp 2B pencil to create the dark grooves on the pit and the irregular texture on the slice. Finish with lines radiating outward from the seed and the top of the slice.

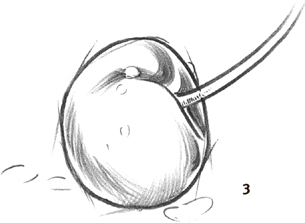

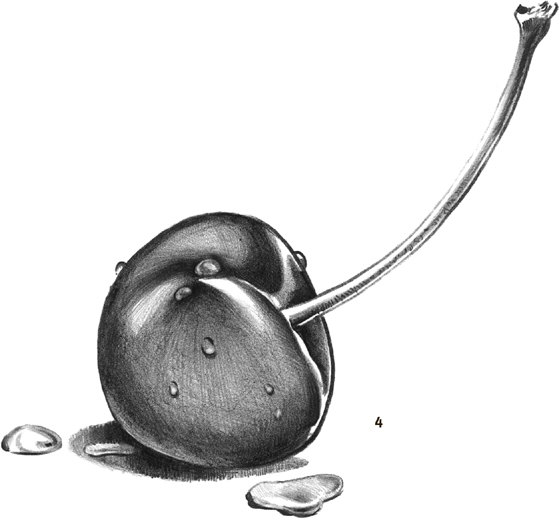

Cherry

Drawing the Cherry To start the cherry, lightly block in the round shape and the stem, using a combination of short sketch lines. Smooth the sketch lines into curves, and add the indentation for the stem. Then begin light shading in step 3. Continue shading until the cherry appears smooth. Use the tip of a kneaded eraser to remove any shading or smears that might have gotten into the highlights. Then fill in the darker areas using overlapping strokes, changing stroke direction slightly to give the illusion of three-dimensional form to the shiny surface.

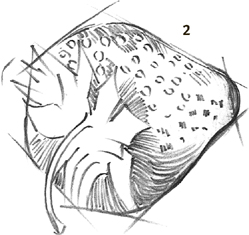

Chestnuts

Rendering the Chestnuts To draw these chestnuts, use a circle and two intersecting lines to make a cone shape in steps 1 and 2. Then place some guidelines for ridges in step 3. Shade the chestnuts using smooth, even strokes that run the length of the objects. These strokes bring out form and glossiness. Finally add tiny dots on the surface. Make the cast shadow the darkest part of the drawing.

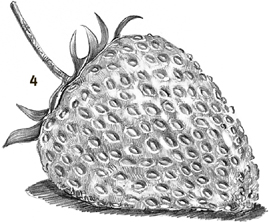

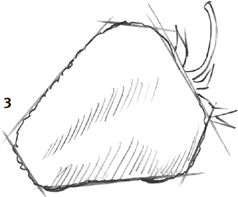

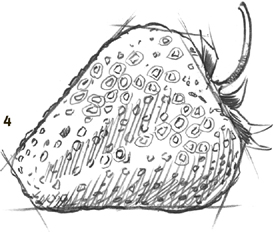

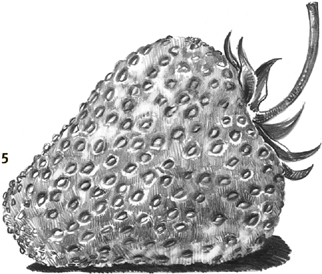

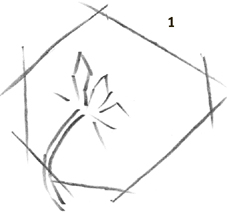

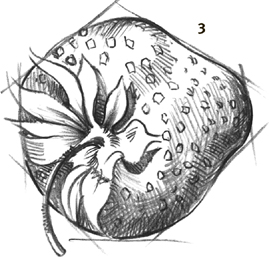

These strawberries were drawn on plate-finish Bristol board using only an HB pencil. Block in the berry’s overall shape in steps 1 and 2. Then lightly shade the middle and bottom in step 3, and scatter a seed pattern over the berry’s surface in step 4. Once the seeds are in, shade around them.

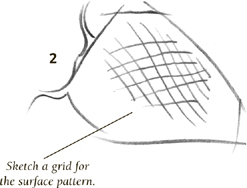

Drawing Guidelines Draw a grid on the strawberry; it appears to wrap around the berry, helping to establish its seed pattern and three-dimensional form.

Developing Highlights and Shadows It’s important to shade properly around the seeds, creating small circular areas that contain both light and dark. Also develop highlights and shadows on the overall berry to present a realistic, uneven surface.

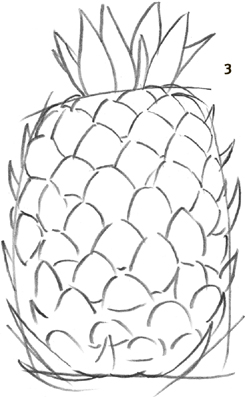

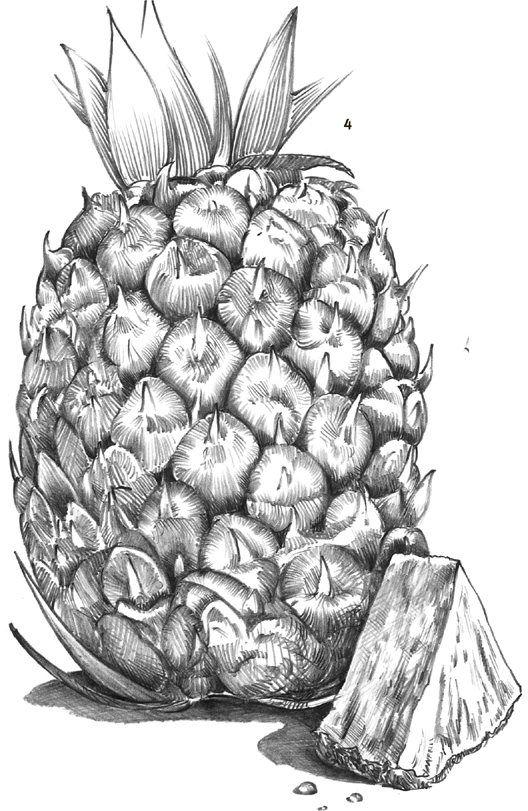

Like the strawberry, a prickly pineapple has an involved surface pattern. The pineapple below was done on plate-finish Bristol board using an HB pencil for the main layout and light shading, as well as a 2B for darker areas.

Drawing the Pineapple Sketch the primary shape in step 1, and add block-in lines for the pineapple’s surface pattern in steps 2 and 3. Use a sharp 2B to draw subtle texture lines at various angles on each pineapple “section,” using the stroke and lift technique; begin at the edge, stroke toward the middle, and lift the pencil at the end of the stroke. Finally shade the cast shadow smoother and darker than the fruit surfaces, and add drops of juice for an appealing effect.

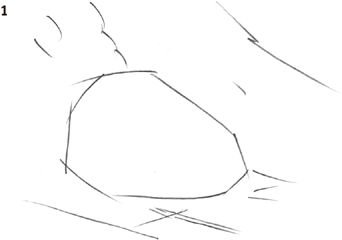

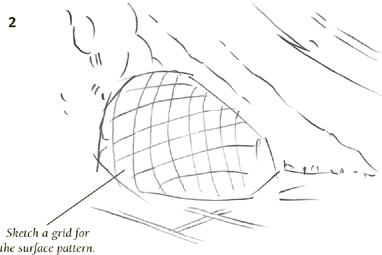

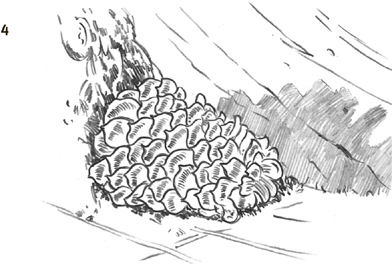

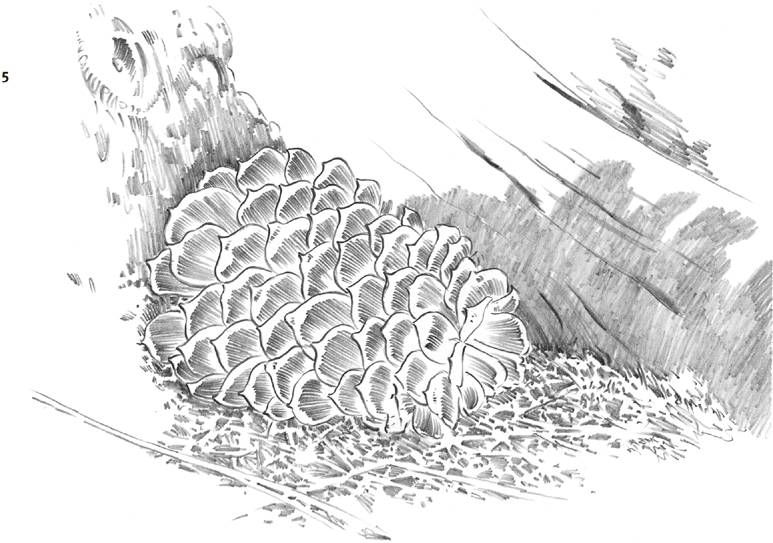

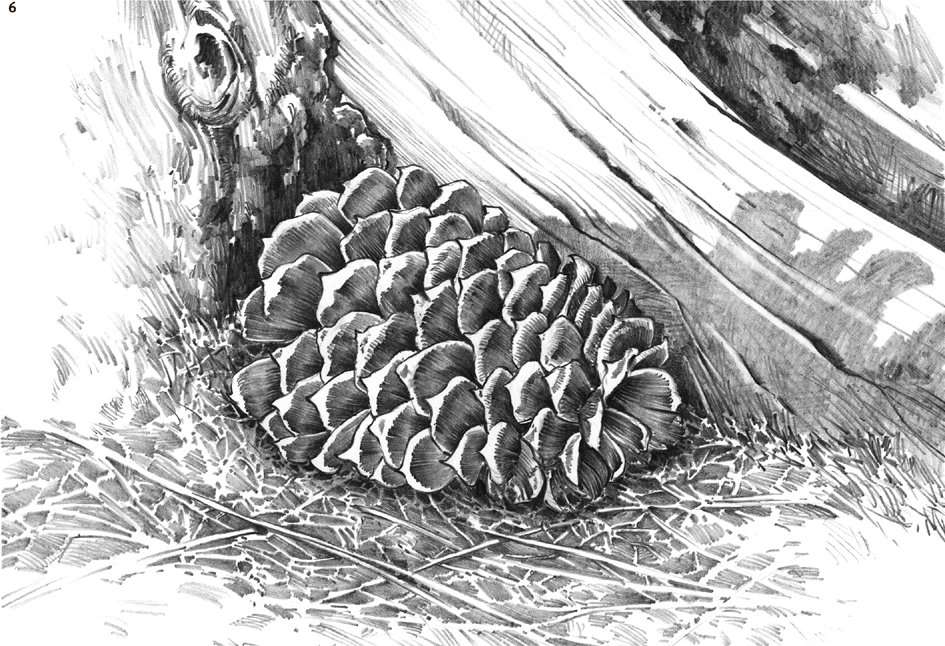

Compare the highly textured surface pattern of the pinecone with the strawberry and pineapple on pages 24–25. Using an HB pencil, position the pinecone with light guidelines in step 1. Then indicate the tree trunk and pine needles in step 2, and add a grid for the pattern on the pinecone.

Establishing Detail Draw the shapes of the spiked scales, which change in size from one end of the cone to the other. In step 4, begin shading the cone and surrounding objects. Make the cast shadow appear to follow the curve of the tree root.

Working with Negative Space Develop the grass in step 5 by drawing the negative spaces; instead of drawing individual pine needles and blades of grass, fill in the shadows between them. By shading around the negative spaces, the grass shapes will automatically emerge from the white of the paper. (See page 13 for more on negative space.)

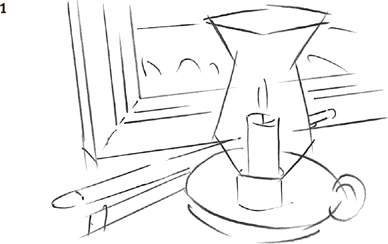

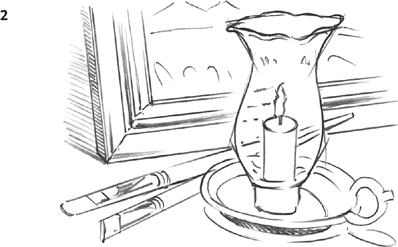

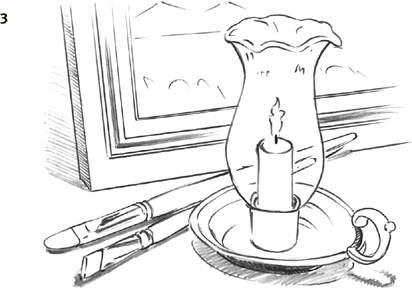

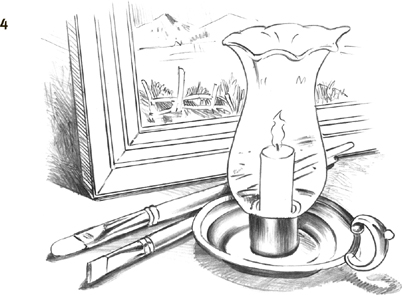

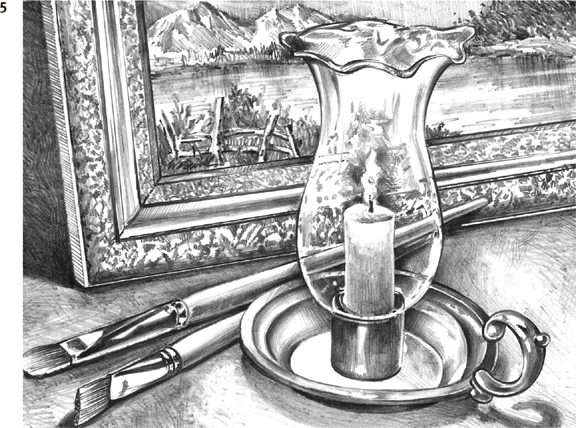

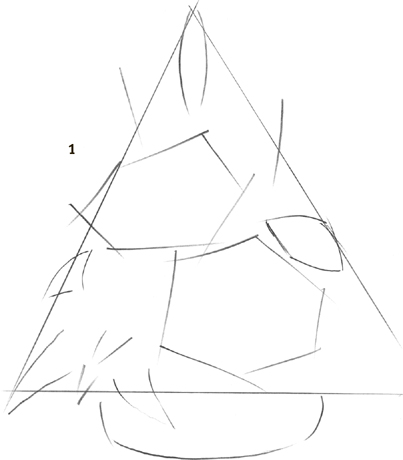

This drawing was done on plate-finish Bristol board with HB and 2B pencils. The pewter-and-glass candlestick, painting, and paintbrushes were arranged on a table; then a quick sketch was made to check the composition, as shown in step 1.

Blocking In the Composition When setting up a still life, keep rearranging the items until the composition suits you. If you’re a beginner, you might want to keep the number of objects to a minimum—three to five elements is a good number to start with.

Developing Shape and Form In step 2, place all the guidelines of your subjects; then begin shading with several layers of soft, overlapping strokes in step 3. Gradually develop the dark areas rather than all at the same time.

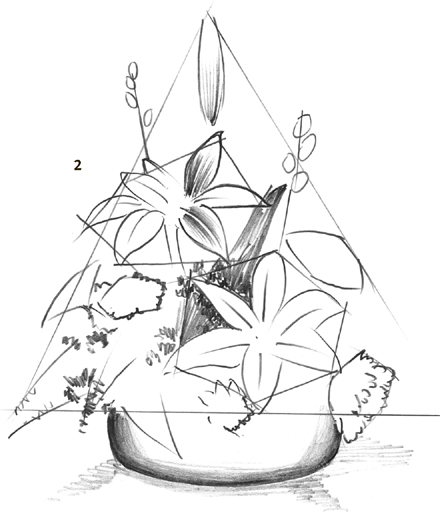

By varying your techniques, you become a more versatile artist. Therefore this drawing was drawn more loosely than the previous one. Begin with an HB pencil, lightly drawing in the basic shapes within the floral arrangement.

Sketching Loosely This rendering was finished using a loose, sketchy technique. Sometimes this type of final can be more pleasing than a highly detailed one.

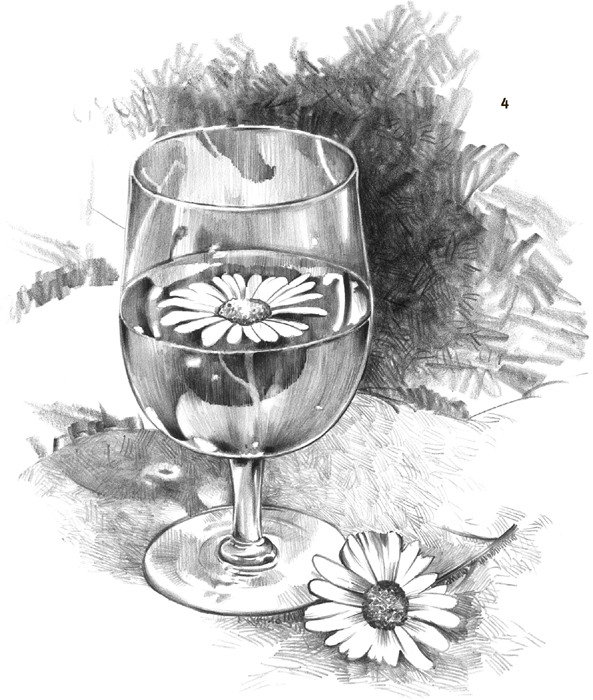

This drawing was done on Bristol board with a plate (smooth) finish. Use an HB pencil for most of the work and a 2B for the dark shadows. A flat sketch pencil is good for creating the background texture.

Starting Out In step 1, sketch the basic shapes of the glass, liquid, and flowers. In step 2, add more details, and begin shading the glass and liquid areas. Take your time, and try to make the edges clean.

Developing the Background Use the flat lead of a sketching pencil for the background, making the background darker than the cast shadows. Note the pattern of lights and darks that can be found in the cast shadow.

Finalizing Highlights and Shadows Use the finished drawing as your guide for completing lights and darks. If pencil smudges accidentally get in the highlights, clean them out with a kneaded eraser. Then use sharp-pointed HB and 2B pencils to add final details.

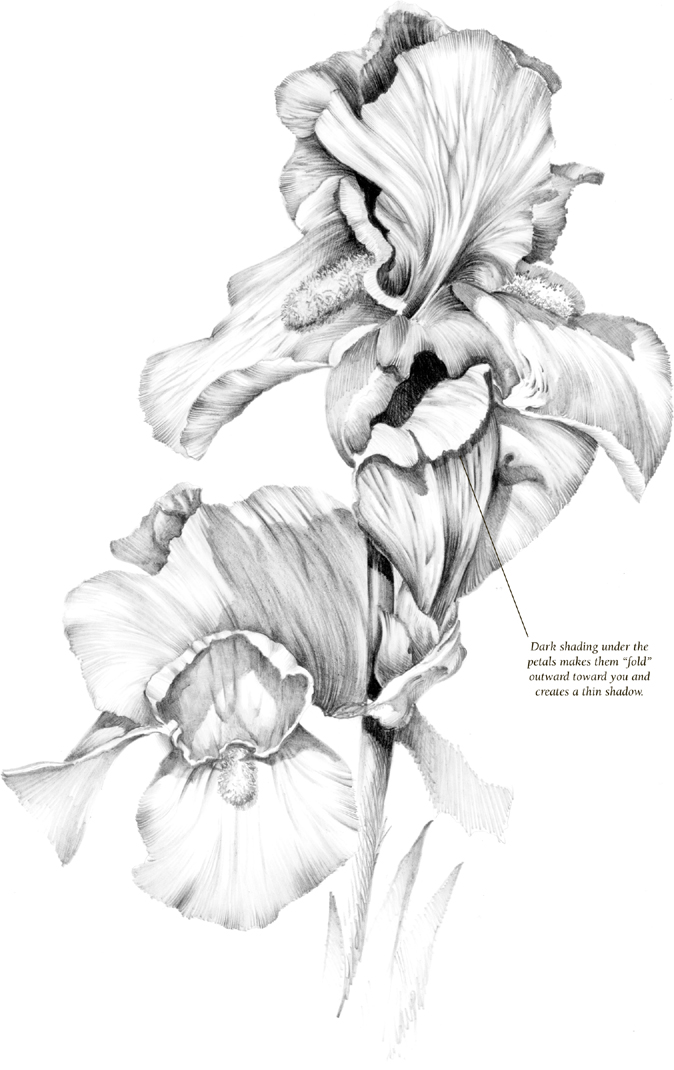

Many beginning artists believe a rose is too difficult to draw and therefore may shy away from it. But, like any other object, a rose can be developed step by step from its most basic shapes.

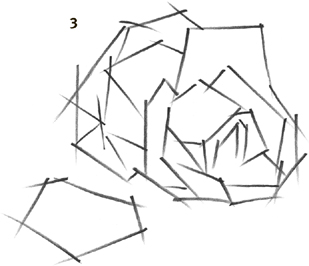

Establishing Guidelines Use an HB pencil to block in the overall shapes of the rose and petal, using a series of angular lines. Make all guidelines light so you won’t have trouble removing or covering them later.

Following Through Continue adding guidelines for the flower’s interior, following the angles of the petal edges.

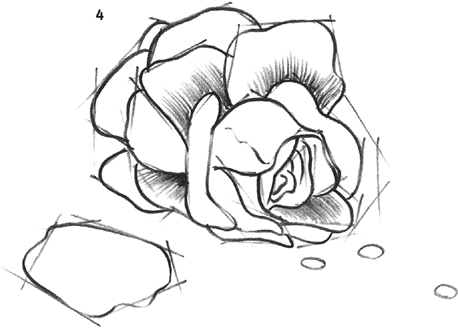

Adding Values Now begin shading. Stroke from inside each petal toward its outer edge.

Developing Shading Shade from the outer edge of each petal, meeting the strokes you drew in the opposite direction. Use what is known as a stroke and lift technique. For this technique, you should draw lines that gently fade at the end. Just press firmly, lifting the pencil as the stroke comes to an end.

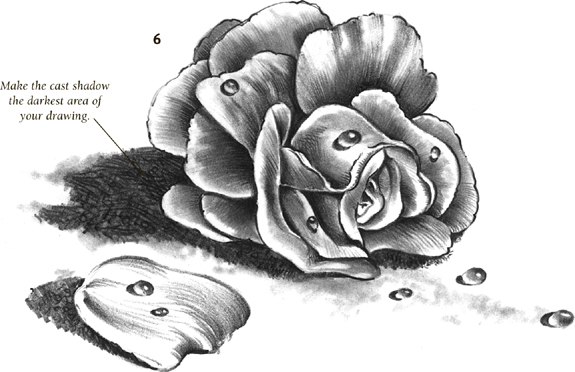

Make the cast shadow the darkest area of your drawing.

This morning glory and gardenia are great flowers for learning a few simple shading techniques called “hatching” and “cross-hatching.” Hatch strokes are parallel diagonal lines; place them close together for dark shadows, and space them farther apart for lighter values. Cross-hatch strokes are made by first drawing hatch strokes and then overlapping them with hatch strokes that are angled in the opposite direction. Examples of both strokes are shown in the box at the bottom of the page.

Morning Glory

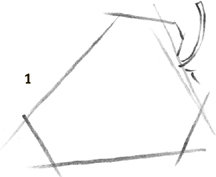

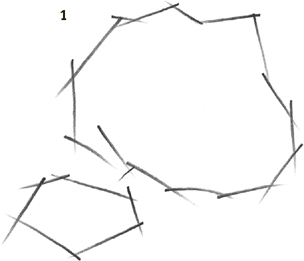

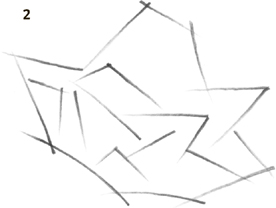

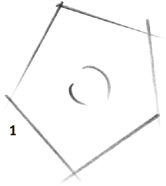

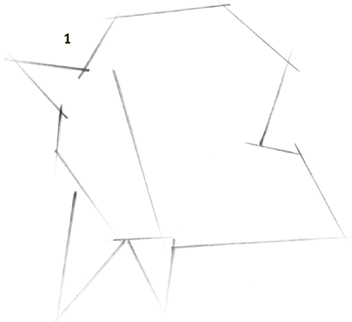

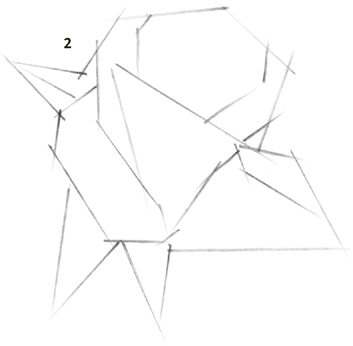

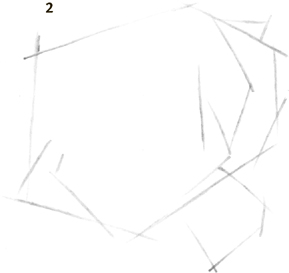

Step One Look carefully at the overall shape of a morning glory and lightly sketch a polygon with the point of an HB pencil. From this three-quarter view, you can see the veins that radiate from the center, so sketch in five curved lines to place them. Then roughly outline the leaves and the flower base.

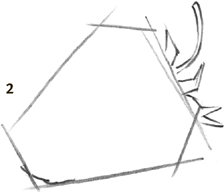

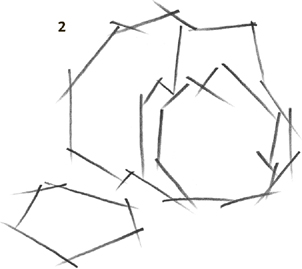

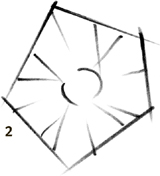

Step Two Next draw the curved outlines of the flower and leaves, using the guidelines for placement. You can also change the pressure of the pencil on the paper to vary the line width, giving it a little personality. Then add the stamens in the center.

Step Three Now you are ready to add the shading. With the rounded point and side of an HB pencil, add a series of hatching strokes, following the shape, curve, and direction of the surfaces of the flower and leaves. For the areas more in shadow, make darker strokes placed closer together, using the point of a soft 2B pencil.

Gardenia

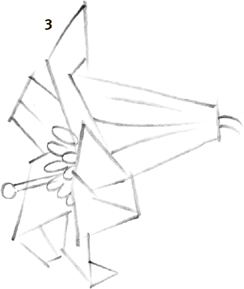

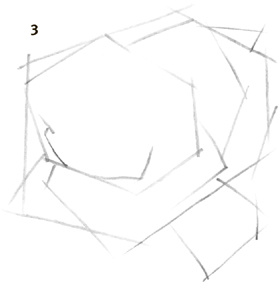

Step One The gardenia is a little more complicated to draw than the morning glory, but you can still start the same way. With straight lines, block in an irregular polygon for the overall flower shape and add partial triangles for leaves. Then determine the basic shape of each petal and begin sketching in each, starting at the center of the gardenia.

Step Two As you draw each of the petal shapes, pay particular attention to where they overlap and to their proportions, or their size relationships—how big each is compared with the others and compared with the flower as a whole. Accurately reproducing the pattern of the petals is one of the most important elements of drawing a flower. Once all the shapes are laid in, refine their outlines.

Step Three Again, using the side and blunt point of an HB pencil, shade the petals and the leaves, making your strokes follow the direction of the curves. Lift the pencil at the end of each petal stroke so the line tapers and lightens, and deepen the shadows with overlapping strokes in the opposite direction (called cross-hatching) with the point of a 2B pencil.

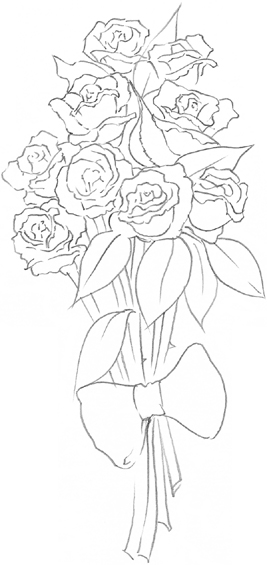

If you look carefully, you will see that although the roses resemble one another, each one has unique features, just as people do. If you make sure your drawing reflects these differences, your roses won’t look like carbon copies of one another.

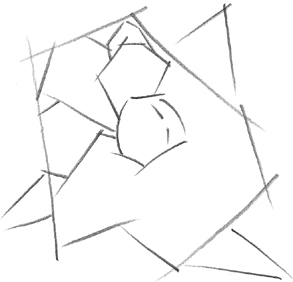

Step One Just as you did for single flowers, begin by drawing the basic shapes of the roses with an HB pencil. Block in only the outlines and a few major petal shapes, without getting involved in the details. Then sketch in the stems and the shape of the ribbon. These first lines are merely guidelines for developing the drawing, so keep the strokes simple and very light.

Step Two Once you’ve established the general outlines, begin developing the secondary shapes of each flower—the curves and indentations of the petals. These are the elements that make each rose unique, so pay careful attention to the shapes at this stage of the drawing.

Step Three Now begin to define the shapes more precisely, adding detail to the innermost petals, refining the stems, and developing the shape of the ribbon. Vary the thickness of each line to give the drawing more character and life. Don’t shade at all in this step; you will want to make sure the drawing is accurate first.

Step Four Sometimes keeping the shading fairly minimal and light shows how effective simple drawings can be. Later in the book, shading will be demonstrated in more detail. Here use hatched strokes and place only enough shading on each flower, leaf, and stem to give it some form.

There are several classes of tulips with differently shaped flowers. The one below, known as a parrot tulip, has less of a cup than the tulip to the right and is more complex to draw. Use the layout steps shown here before drawing the details.

Drawing the Parrot Tulip Begin using straight lines from point to point to capture the major shape of the flower. Add petal angles in step 2. Then draw in actual petal shapes, complete with simple shading.

Creating Form Look for the rhythm of line in this next tulip. It begins with three simple lines in step 1, which set its basic direction. Step 2 demonstrates how to add lines to build the general flower shape. Step 3 adds more to the shape and begins to show the graceful pose of the flower. Step 4 shows more detail and leads to shading, which gives the flower its form.

Just a few shading strokes here enhance the effect of overlapping petals.

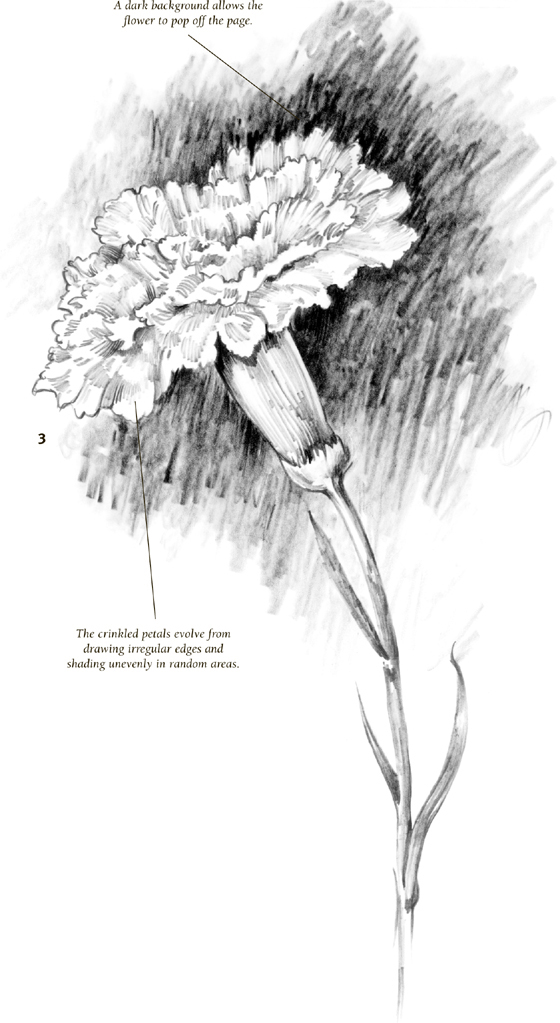

Carnation varieties range from deep red to bicolored to white. They are very showy and easy to grow in most gardens. They are also fun and challenging to draw because of their many overlaying petals. Shade them solid, variegated, or with a light or dark edge at the end of each petal.

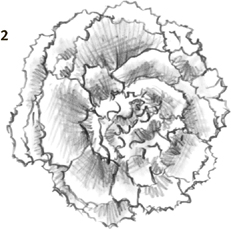

Replicating Patterns and Shapes The front view above shows the complex pattern of this type of carnation. Step 1 places the basic shapes seen within the flower. From here, begin drawing the actual curved petal shapes. Once they are in place, shade the flower.

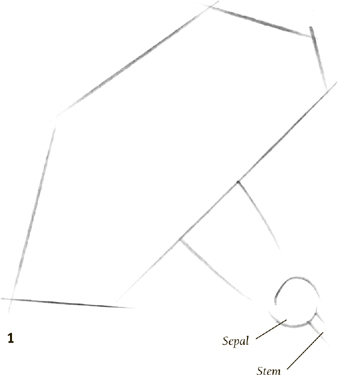

Establishing the Basic Shapes Develop the overall shape of the side view, including the stem and sepal. Begin drawing the intricate flower details in step 2, keeping them light and simple.

Top: A dark background allows the flower to pop off the page.

Bottom: The crinkled petals evolve from drawing irregular edges and shading unevenly in random areas.

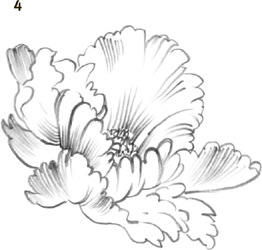

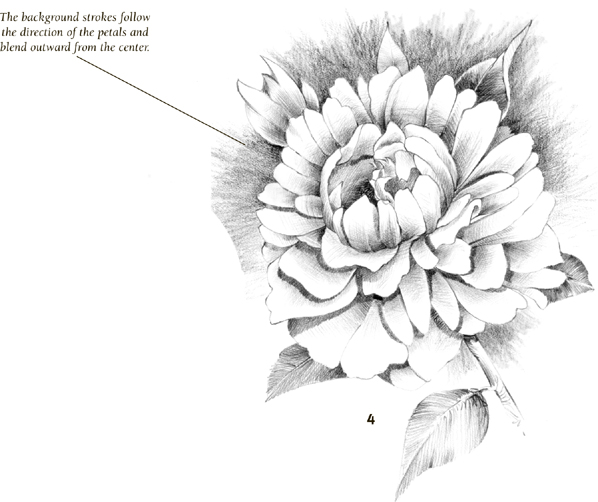

Peonies grow in single- and double-flowered varieties. They are a showy flower and make fine subjects for flower drawings.

Developing the Peony This exercise should be drawn on vellum-finish Bristol board. On this surface, shading produces a bit more texture than the smoother plate finish. Begin the exercise by drawing and positioning the major flower parts in step 1. In step 2, begin shading the petals and surrounding leaves. Start shading in earnest in step 3, and establish the background pattern.

The background strokes follow the direction of the petals and blend outward from the center.

There are different varieties of dogwood. Below is an oriental type called the “kousa dogwood,” and at the right is the American flowering dogwood. Both of their flowers vary from pure white to delicate pink. Follow the steps closely to draw them.

Kousa dogwood

American flowering dogwood

Lilies are very fragrant, and the plants can grow up to 8 feet tall. Use the steps below to develop the flower, which you can attach to the main stem when drawing the entire plant, as shown at the bottom of the page.

Shading lines like these illustrate a technique called cross-hatching and give the petals form.

There are many primrose varieties with a wide range of colors. This exercise demonstrates how to draw a number of flowers and buds together. Take your time when placing them.

Forming the Primrose Blossom Draw a main stem first, and add smaller ones branching outward. Keep them in clusters, curving out in different directions from the same area.

Developing the Leaves These steps show three shading stages of leaves. In step 1 (at the far right), lightly outline leaf shape. Begin shading in step 2, sketching where the leaf veins will be. Then shade around those areas, leaving them white, to bring out the veins. When you reach step 3, clean up the details, and add a few darker areas along some of the veins.

Top: The unopened primrose buds begin with small, egg-like shapes.

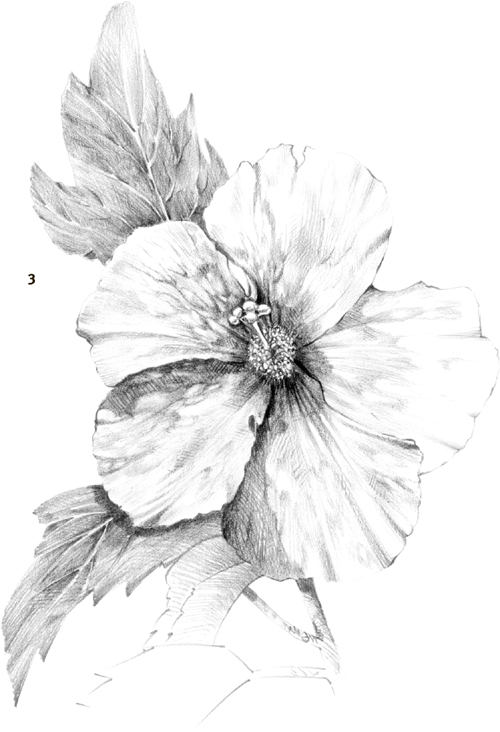

Hibiscus grow in single- and double-flowered varieties, and their colors include whites, oranges, pinks, and reds—even blues and purples. Some are multi- or bicolored. The example here is a single-flowered variety.

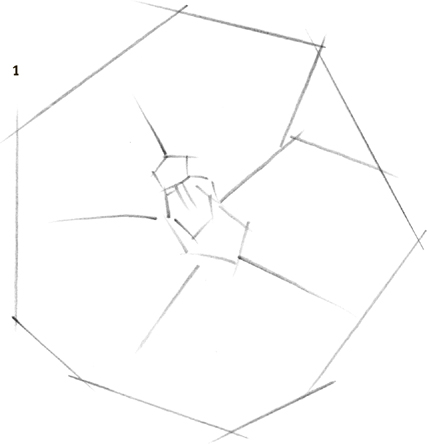

Planning Your Drawing Even though the hibiscus has a lot of detail, it isn’t difficult to draw. Steps leading up to the finished drawing must be followed closely to get the most out of this exercise. Step 1 shows the overall mass, petal direction, and basic center of the flower. Consider the size of each flower part in relation to the whole before attempting to draw it.

Shading Before shading the petals in step 2, study where the shading falls and how it gives the petals a slightly rippled effect. Add the details of the flower center, and block in the stem and leaves.

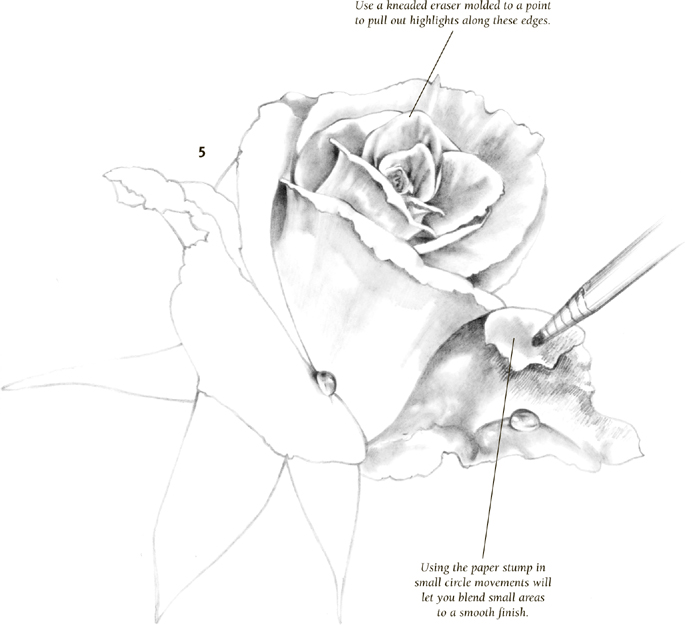

Hybrid tea roses have large blossoms with greatly varying colors. When drawing rose petals, think of each fitting into its own place in the overall shape; this helps position them correctly. Begin lightly with an HB pencil, and use plate-finish Bristol board.

Making Choices The block-in steps are the same no matter how you decide to finish the drawing, whether lightly outlined or completely shaded. For shading, use the side of a 2B pencil and blend with a paper stump.

Top: Use a kneaded eraser molded to a point to pull out highlights along these edges.

Bottom: Using the paper stump in small circle movements will let you blend small areas to a smooth finish.

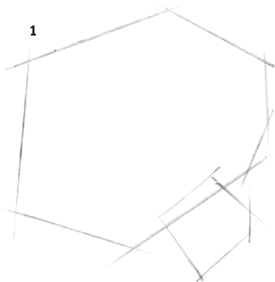

Floribunda roses usually flower more freely than hybrid tea roses and grow in groups of blossoms. The petal arrangement in these roses is involved; but by studying it closely, you’ll see an overlapping, swirling pattern.

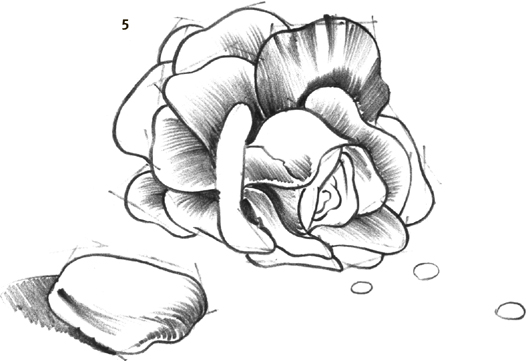

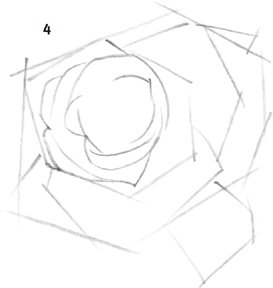

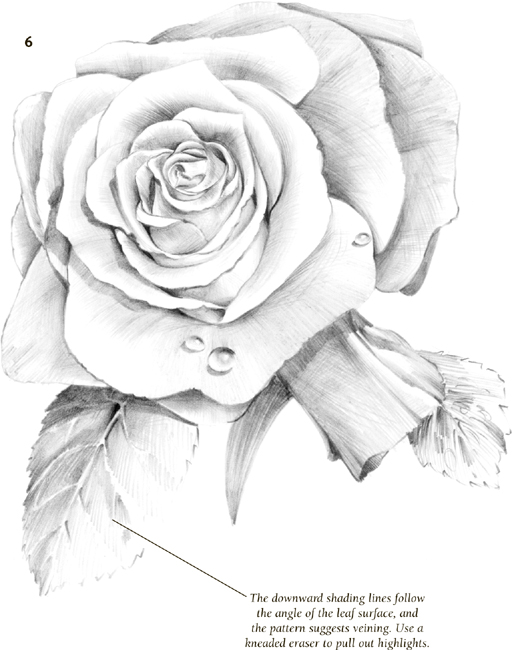

Drawing the Rose Use a blunt-pointed HB pencil lightly on plate-finish Bristol board. Outline the overall area of the rose mass in step 1. Once this is done, draw the swirling petal design as shown in steps 2 and 3. Begin fitting the center petals into place in step 4. Use the side of an HB to shade as in step 5, being careful not to cover the water drops. They should be shaded separately.

The downward shading lines follow the angle of the leaf surface, and the pattern suggests veining. Use a kneaded eraser to pull out highlights.

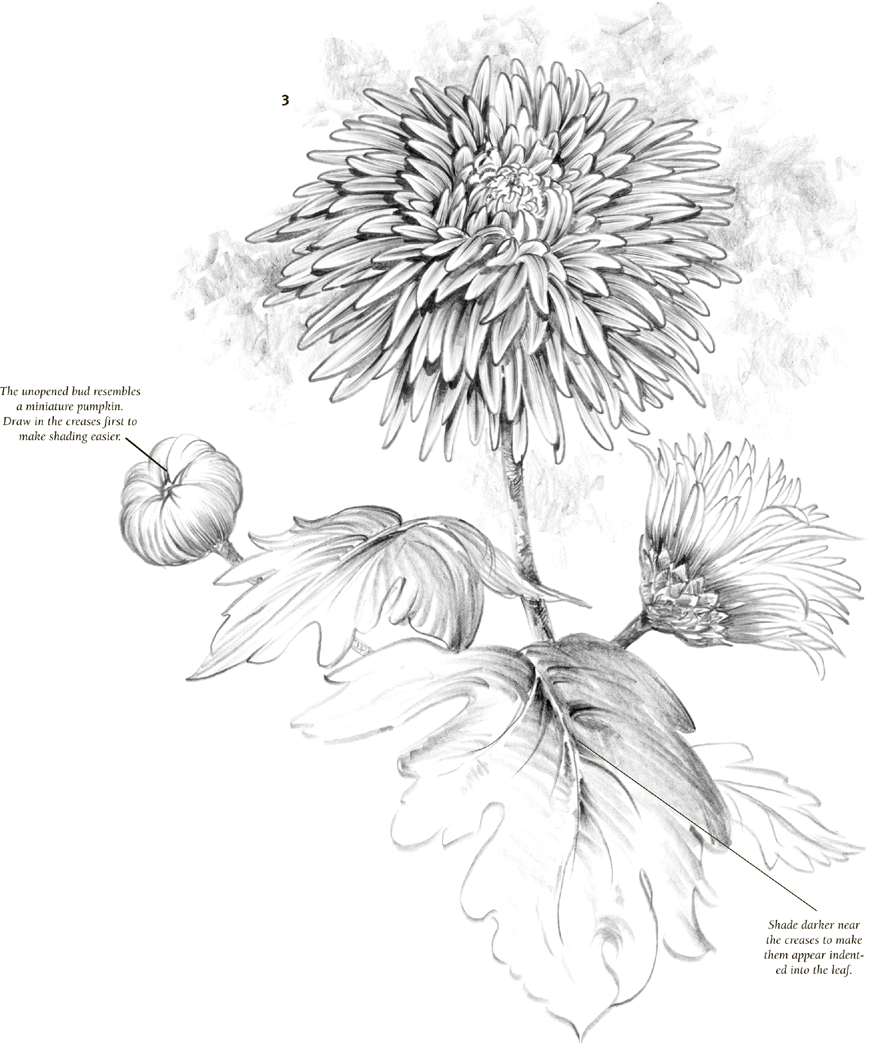

The two varieties of chrysanthemums on this page are the pompon and the Japanese anemone. The pompon chrysanthemum produces flowers one to two inches across that are more buttonlike than the larger, more globular types.

The Japanese anemone grows four inches or more across and produces flowers with irregular outlines that, in some cases, resemble forms of anemone sea life.

Follow the steps for each flower type, trying to capture the attitude and personality of each flower and petal formation. It’s best to draw this exercise on plate-finish Bristol board using both HB and 2B pencils. Smooth bond paper also provides a good drawing surface.

Pompon chrysanthemum

Side view

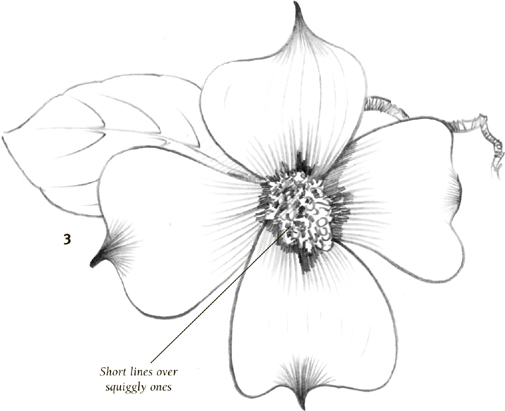

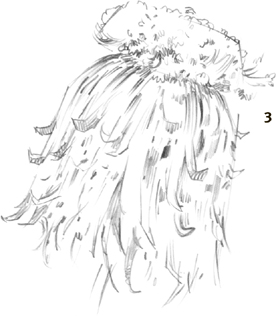

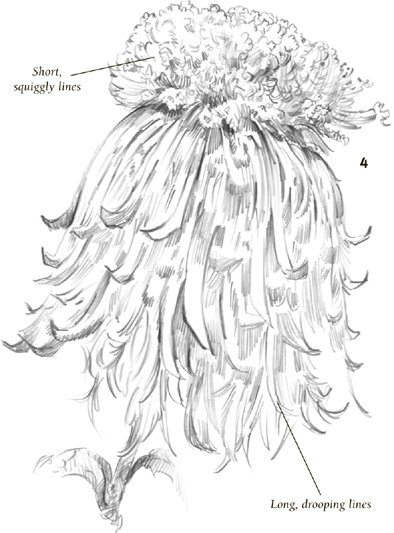

Observe the difference in texture between the top of the Japanese anemone blossom below and its sides. The voluminous, bushy effect is achieved with many short, squiggly lines drawn in random directions, in contrast to the sloping lines of the lower petals.

Japanese anemone chrysanthemum

Drawing Petals Follow the arrows when developing the petals. Work from the center outward, allowing each new petal to be overlapped by the previous one. Step 2 shows most of the petals in place, but notice that changes to their position may occur when you shade.

Applying Shading A flat sketching pencil is best for shading the broad portions of the leaves. Use the corner of the lead to draw the outlines and indicate veining. To create a more interesting “sketchy” look, leave some parts unshaded rather than finishing them off at the edges, as shown above.

Left: The unopened bud resembles a miniature pumpkin. Draw in the creases first to make shading easier.

Right: Shade darker near the creases to make them appear indentedinto the leaf.

Border Chrysanthemum

Seeing the Shapes Border chrysanthemums produce larger, more bulbous flowers. Their petal arrangement is challenging to draw. Develop the drawing outline with a 2B pencil, then add an interesting background using a flat sketch pencil with random strokes and varying pressures.

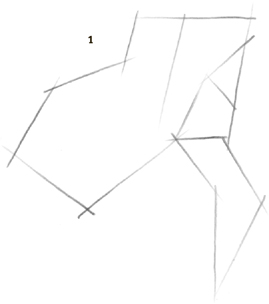

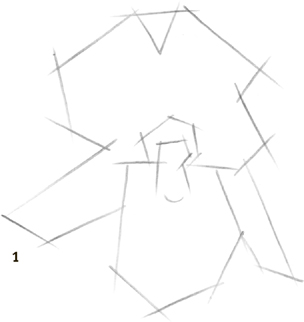

The bearded iris is probably the most beautiful of the iris varieties. Its colors range from deep purples to blues, lavenders, and whites. Some flowers have delicate, lightly colored petals with dark veining. They range in height from less than a foot to over three feet.

Using Guidelines Step 1 (above) shows the block-in lines for a side view of the iris, whereas step 1 (below) shows a frontal view. Whichever you choose to draw, make your initial outline shapes light, and use them as a general guide for drawing the graceful curves of this flower’s petals.

Beginning to Shade Follow the arrow directions in step 3 for blending and shading strokes; these strokes make the petal surfaces appear solid. Darken shadowed areas using the point of a 2B.

Good, clean block-in lines are helpful for shading an involved subject. Take your time, and plan ahead to save correction time.

Dark shading under the petals makes them “fold” outward toward you and creates a thin shadow.

Adding Shading and Highlights This drawing was done on plate-finish Bristol board using HB, 2B, and flat sketching pencils. Create highlights by molding a kneaded eraser into a sharp wedge, “drawing” with it in the same direction as the shading.

Creating a good still life composition is simply arranging the elements of a drawing in such a way that they make an eye-pleasing, harmonious scene. It’s easy to do once you have a few guidelines to follow. The most important things to keep in mind are: (1) choosing a format that fits the subject, (2) establishing a center of interest and a line of direction that carries the viewer’s eye into and around the picture, and (3) creating a sense of depth by overlapping objects, varying the values, and placing elements on different planes. Like everything else, the more you study and practice forming pleasing compositions, the better you’ll become.

ARRANGING A STILL LIFE

Composing still lifes is a great experience because you select the lighting, you place the elements where you like, and the objects don’t move! Begin by choosing the items to include, and then try different groupings, lighting, and backgrounds. Test out the arrangements in small, quick thumbnails, like the ones shown below. These studies are invaluable for working out the best possible composition.

Step One From your thumbnail sketches, choose a horizontal format. Notice that the tureen is set off-center; if the focal point were dead center, your eye wouldn’t be led around the whole drawing, which would make a boring composition. Then lightly block in the basic shapes with mostly loose, circular strokes, using your whole arm to keep the lines free.

Step Two Next refine the shapes of the various elements, still keeping your lines fairly light to avoid creating harsh edges. Then, using the side of an HB pencil, begin indicating the cast shadows, as well as some of the details on the tureen.

Step Three Continue adding details on the tureen and darkening the cast shadows. Then start shading some of the objects to develop their forms. You might want to begin with the bell pepper and the potato, using the point and side of an HB pencil.

Step Four Next build the forms of the other vegetables, using a range of values and shading techniques. To indicate the paper skins of the onion and the garlic, make strokes that curve with their shapes. For the rough texture of the potato, use more random strokes.

Step Five When you are finished developing the light, middle, and dark values, use a 2B pencil for the darkest areas in the cast shadows (the areas closest to the objects casting the shadows).

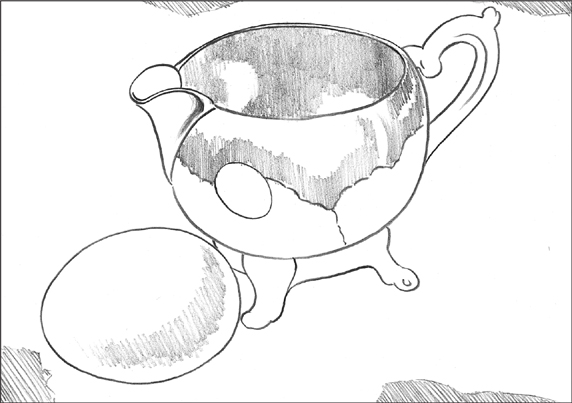

The shiny surface of a highly polished, silver creamer is perfect for learning to render reflective surfaces. For this exercise, use plate-finish Bristol board, HB and 2B pencils, and a kneaded eraser molded into a point. Begin by lightly drawing in the basic shapes of the egg and creamer.

Step One Begin by lightly blocking in the basic shapes of the egg and the creamer. Don’t go on to the next step until you’re happy with the shapes and the composition.

Step Two Once the two central items are in place, establish the area for the lace, and add light shading to the table surface. Next position the reflection of the lace and egg on the creamer’s surface. Begin lightly shading the inside and outside surfaces of the creamer, keeping in mind that the inside is not as reflective or shiny. Then start lightly shading the eggshell.

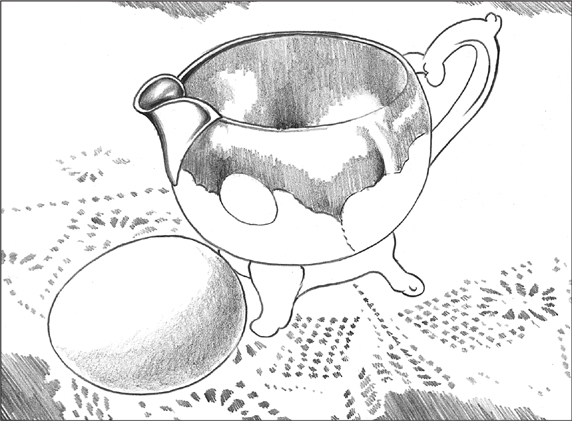

Step Three At this stage, smooth the shading on the egg and creamer with a paper stump. Then study how the holes in the lace change where the lace wrinkles and then settles back into a flat pattern. Begin drawing the lace pattern using one of the methods described on the opposite page.

Step Four In the final drawing, pay close attention to the reflected images because they are key to successfully rendering the objects. Interestingly the egg’s position in the reflection is completely different than its actual position on the table because in the reflection we see the back side of the egg.

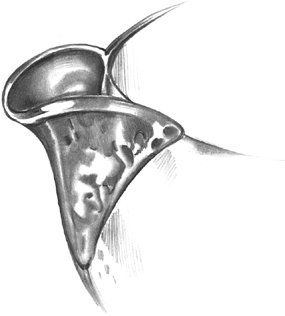

Foot

Spout

Foot and Spout Details These two close-up drawings show detail on the creamer’s spout and feet. These are not as shiny as the rounded bowl. Re-create this matte finish by blending the edges and making the concave shadow patterns darker and sharper.

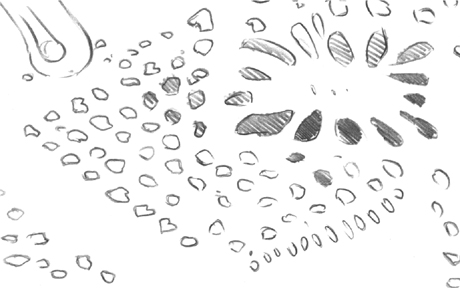

Lace Pattern Detail The drawings above show two approaches for creating the lace pattern. You can draw guidelines for each hole and then shade inside them (left), or you can lightly shade in the shape of each hole (right). Either way, you are drawing the negative shapes. (See page 13.) Once the pattern is established, shade over the areas where you see shadows, along with subtle shadows cast within most of the holes. Make the holes in the foreground darker than those receding into the composition, but keep them lighter than the darkest areas on the creamer. After this preliminary shading is completed, add details of dark and light spots on the lace.

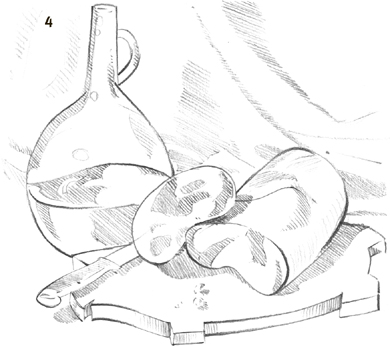

This exercise was drawn on vellum-finish Bristol board with an HB pencil. Vellum finish has a bit more “tooth” than the smoother plate finish does, resulting in darker pencil marks.

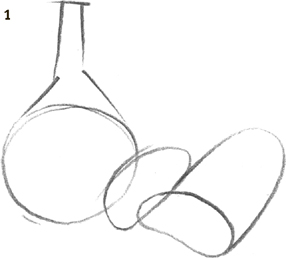

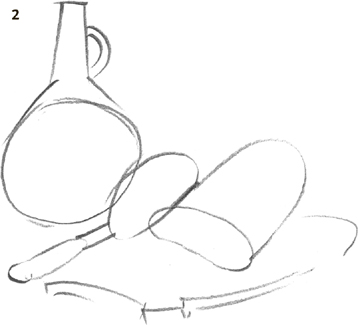

Blocking In the Composition Begin lightly sketching the wine bottle, bread loaf, knife, and cutting board, roughing in the prominent items first, then adding the remaining elements in step 2. Continue refining the shapes in step 3, and then indicate the placement for the backdrop.

Placing Highlights and Shadows Lightly outline where the highlights will be so you don’t accidentally fill them in with pencil. Now add shadows with uniform diagonal strokes. Use vertical strokes on the sides of the cutting board.

Developing Form and Texture To draw the irregular texture of the bread’s interior, make a variety of marks—tiny lines, dots, and smudges—creating a speckled, breadcrumb appearance. For the crust, use longer, flowing strokes that wrap around the bread’s exterior. Finish with angled lines on the crust for additional texture.