curriculum research

curriculum researchCritical educational research |

CHAPTER 2 |

This chapter sets out key features of critical theory as they apply to educational research, and then it links these to:

curriculum research

curriculum research

participatory action research

participatory action research

feminist theory

feminist theory

It recognizes that other approaches can be included under the umbrella of critical theory (e.g. post-colonial theory, queer theory), and, whilst the chapter includes a note on these, it does not develop them here. Indeed critical theory embraces a range of other theories, e.g. critical race theory, critical pedagogy, critical disability theory.

Positivist and interpretive paradigms are essentially concerned with understanding phenomena through two different lenses. Positivism strives for objectivity, measurability, predictability, controllability, patterning, the construction of laws and rules of behaviour, and the ascription of causality; the interpretive paradigms strive to understand and interpret the world in terms of its actors. In the former, observed phenomena are important; in the latter, meanings and interpretations are paramount. Habermas (1984: 109–10), echoing Giddens (1976), describes this latter as a ‘double hermeneutic’, where people strive to interpret and operate in an already interpreted world; researchers have their own values, views and interpretations, and these affect their research, and, indeed that which they are researching is a world in which other people act on their own interpretations and views.

It was suggested earlier that mixed methods research has an affinity with equity, social justice and a ‘transformative paradigm’ (Mertens, 2007), and it is to this that we turn now. An emerging approach to educational research is the paradigm of critical educational research. This regards the two previous paradigms of positivism and interpretivism as presenting incomplete accounts of social behaviour by their neglect of the political and ideological contexts of much educational research. Positivistic and interpretive paradigms are seen as preoccupied with technical and hermeneutic knowledge respectively (Gage, 1989). The paradigm of critical educational research is heavily influenced by the early work of Habermas and, to a lesser extent, his predecessors in the Frankfurt School, most notably Adorno, Marcuse, Horkheimer and Fromm. Here the expressed intention is deliberately political – the emancipation of individuals and groups in an egalitarian society.

Critical theory is explicitly prescriptive and normative, entailing a view of what behaviour in a social democracy should entail (Fay, 1987; Morrison, 1995a). Its intention is not merely to give an account of society and behaviour but to realize a society that is based on equality and democracy for all its members. Its purpose is not merely to understand situations and phenomena but to change them. In particular it seeks to emancipate the disempowered, to redress inequality and to promote individual freedoms within a democratic society.

In this enterprise critical theory identifies the ‘false’ or ‘fragmented’ consciousness (Eagleton, 1991) that has brought an individual or social group to relative powerlessness or, indeed, to power, and it questions the legitimacy of this. It holds up to the lights of legitimacy and equality issues of repression, voice, ideology, power, participation, representation, inclusion and interests. It argues that much behaviour (including research behaviour) is the outcome of particular illegitimate, dominatory and repressive factors; illegitimate in the sense that they do not operate in the general interest – one person’s or group’s freedom and power is bought at the price of another’s freedom and power. Hence critical theory seeks to uncover the interests at work in particular situations and to interrogate the legitimacy of those interests, identifying the extent to which they are legitimate in their service of equality and democracy. Its intention is transformative: to change society and individuals to social democracy. In this respect the purpose of critical educational research is intensely practical and political, to bring about a more just, egalitarian society in which individual and collective freedoms are practised, and to eradicate the exercise and effects of illegitimate power. The pedigree of critical theory in Marxism, thus, is not difficult to discern. For critical theorists, researchers can no longer claim neutrality and ideological or political innocence.

Critical theory and critical educational research, then, have their substantive agenda – for example by examining and interrogating the relationships between school and society: how schools perpetuate or reduce inequality; the social construction of knowledge and curricula – who defines worthwhile knowledge, what ideological interests this serves, and how this reproduces inequality in society; how power is produced and reproduced through education; whose interests are served by education and how legitimate these are (e.g. rich, white, middle-class males rather than poor, non-white, females).

The significance of critical theory for research is immense, for it suggests that much social research is comparatively trivial in that it accepts rather than questions given agendas for research, compounded by the funding for research, which underlines the political dimension of research sponsorship (discussed later) (Norris, 1990). Critical theorists would argue that the positivist and interpretive paradigms are essentially technicist, seeking to understand and render more efficient an existing situation, rather than to question or transform it.

Habermas’s early work (1972) offers a useful tripartite conceptualization of interests that catches three of the paradigms of research in this chapter. He suggests that knowledge – and hence research knowledge – serves different interests. Interests, he argues, are socially constructed, and are ‘knowledge-constitutive’, because they shape and determine what counts as the objects and types of knowledge. Interests have an ideological function (Morrison, 1995a), for example, a ‘technical interest’ (discussed below) can have the effect of keeping the empowered in their empowered position and the disempowered in their powerlessness – i.e. reinforcing and perpetuating the status quo. An ‘emancipatory interest’ (discussed below) threatens the status quo. In this view knowledge – and research knowledge – is not neutral (see also Mannheim, 1936). What counts as worthwhile knowledge is determined by the social and positional power of the advocates of that knowledge. The link here between objects of study and communities of scholars echoes Kuhn’s (1962) notions of paradigms and paradigm shifts, discussed earlier. Knowledge and definitions of knowledge reflect the interests of the community of scholars who operate in particular paradigms. Habermas (1972) constructs the definition of worthwhile knowledge and modes of understanding around three cognitive interests:

i prediction and control;

ii understanding and interpretation;

iii emancipation and freedom.

He names these the ‘technical’, ‘practical’ and ‘emancipatory’ interests respectively. The technical interest characterizes the scientific, positivist method outlined earlier, with its emphasis on laws, rules, prediction and control of behaviour, with passive research objects – instrumental knowledge. The practical interest, an attenuation of the positivism of the scientific method, is exemplified in the hermeneutic, interpretive methodologies outlined in the qualitative approaches earlier (e.g. symbolic interactionism). Here research methodologies seek to clarify, understand and interpret the communications of ‘speaking and acting subjects’ (Habermas, 1974: 8).

Hermeneutics focuses on interaction and language; it seeks to understand situations through the eyes of the participants, echoing the verstehen approaches of Weber (Ringer, 1997) and premised on the view that reality is socially constructed (Berger and Luckmann, 1967). Indeed Habermas (1988: 12) suggests that sociology must understand social facts in their cultural significance and as socially determined. Hermeneutics involves recapturing the meanings of interacting others, recovering and reconstructing the intentions of the other actors in a situation. Such an enterprise involves the analysis of meaning in a social context (Held, 1980). Gadamer (1975: 273) argues that the hermeneutic sciences (e.g. qualitative approaches) involve the fusion of horizons between participants. Meanings rather than phenomena take on significance here.

The emancipatory interest subsumes the previous two paradigms; it requires them but goes beyond them (Habermas, 1972: 211). It is concerned with praxis – action that is informed by reflection with the aim to emancipate (Kincheloe, 1991: 177). The twin intentions of this interest are to expose the operation of power and to bring about social justice as domination and repression act to prevent the full existential realization of individual and social freedoms (Habermas, 1979: 14). The task of this knowledge-constitutive interest, indeed of critical theory itself, is to restore to consciousness those suppressed, repressed and submerged determinants of unfree behaviour with a view to their dissolution (Habermas, 1984: 194–5). This is a transformative agenda, concerned to move from oppression and in equality in society to the bringing about of social justice, equity and equality. These concern fairness in the egalitarian distribution of opportunities for, uptake of, processes in, participation in and outcomes of education and its impact on society, together with distributive justice, social justice and equality.

Mertens (2007: 213) argues that a transformative paradigm enters into every stage of the research process, because it concerns an interrogation of power. A transformative paradigm, she avers (pp. 216 and 224) has several ‘basic beliefs’:

Ontology (the nature of reality or of a phenomenon): politics and interests shape multiple beliefs and values, as these beliefs and values are socially constructed, privileging some views of reality and under-representing others.

Epistemology (how we come to know these multiple realities): influenced by communities of practice who define what counts as acceptable ways of knowing, and affecting the relationships between the researcher and the communities who are being researched, such that partnerships are formed that are based on equality of power and esteem.

Methodology (how we research complex, multiple realities): influenced by communities of practice who define what counts as acceptable ways of researching, and in which mixed methods have a significant role to play, as they enable a qualitative dialogue to be established between the participants in the research.

Axiology (principles and meanings in conducting research, and the ethics that govern these): beneficence, respect and the promotion of social justice (see Chapter 5).

Mertens argues (2007: 220) for mixed methods in a transformative paradigm, as they reduce the privileging of only powerful voices in society, and she suggests that participatory action research is a necessary, if not sufficient, element of a transformative paradigm, as it involves people as equals. This is introduced later in the chapter.

In Habermas’s early work we attempt to conceptualize three research styles: the scientific, positivist style; the interpretive style; and the emancipatory, ideology critical style. Not only does critical theory have its own research agenda, but it also has its own research methodologies, in particular ideology critique and action research. The three methodologies, then, aligned to Habermas’s knowledge-constitutive interests, are shown in Table 2.1.

With regard to ideology critique, a particular reading of ideology is being adopted here: the suppression of generalizable interests (Habermas, 1976: 113), where systems, groups and individuals operate in rationally indefensible ways because their power to act relies on the disempowering of other groups, i.e. that their principles of behaviour cannot be generalized.

Ideology – the values and practices emanating from particular dominant groups – is the means by which powerful groups promote and legitimate their particular – sectoral – interests at the expense of disempowered groups. Ideology critique exposes the operation of ideology in many spheres of education, the working out of vested interests under the mantle of the general good. The task of ideology critique is to uncover the vested interests at work which may be occurring consciously or subliminally, revealing to participants how they may be acting to perpetuate a system which keeps them either empowered or disempowered (Geuss, 1981), i.e. which suppresses a generalizable interest. Explanations for situations might be other than those ‘natural’, taken-for-granted, explanations that the participants might offer or accept. Situations are not natural but problematic (Carr and Kemmis, 1986). They are the outcomes or processes wherein interests and powers are protected and suppressed, and one task of ideology critique is to expose this (Grundy, 1987). The interests at work are uncovered by ideology critique, which, itself, is premised on reflective practice (Morrison, 1995a, 1995b, 1996a). Habermas (1972: 230) suggests that ideology critique through reflective practice can be addressed in four stages:

TABLE 2.1 HABERMAS’S KNOWLEDGE-CONSTITUTIVE INTERESTS AND THE NATURE OF RESEARCH

Interest |

Methodology |

Characteristics |

Technical interest |

Scientific testing and proof |

Scientific methodology; positivist (e.g. surveys, experiments); hypothesis testing; quantitative. |

Practical interest |

Hermeneutic; interpretive, understanding |

Interactionist; phenomenological; humanistic; ethnographic; existential; anthropological; naturalistic; narratives; qualitative. |

Emancipatory interest |

Ideology critique |

Political agenda, interrogation of power, transformative potential: people gaining control over their own lives; concern for social justice and freedom from oppression and from the suppression of generalizable interests; research to change society and to promote democracy. |

Stage 1: a description and interpretation of the existing situation – a hermeneutic exercise that identifies and attempts to make sense of the current situation (echoing the verstehen approaches of the interpretive paradigm).

Stage 2: a presentation of the reasons that brought the existing situation to the form that it takes – the causes and purposes of a situation and an evaluation of their legitimacy, involving an analysis of interests and ideologies at work in a situation, their power and legitimacy (both in micro-and macro-sociological terms). Habermas’s early work (1972) likens this to psychoanalysis as a means for bringing into the consciousness of ‘patients’ those repressed, distorted and oppressive conditions, experiences and factors that have prevented them from a full, complete and accurate understanding of their conditions, situations and behaviour, and that, on such exposure and examination, will be liberatory and emancipatory. Critique here reveals to individuals and groups how their views and practices might be ideological distortions that, in their effects, perpetuate a social order or situation that works against their democratic freedoms, interests and empowerment (see also Carr and Kemmis, 1986: 138–9).

Stage 3: an agenda for altering the situation – in order for moves to an egalitarian society to be furthered (the ‘transformative paradigm’ mentioned earlier).

Stage 4: an evaluation of the achievement of the situation in practice.

In the world of education Habermas’s stages are paralleled by Smyth (1989) who, too, denotes a four-stage process: description (what am I doing?); information (what does it mean?); confrontation (how did I come to be like this?); and reconstruction (how might I do things differently?). It can be seen that ideology critique here has both a reflective, theoretical and a practical side to it; without reflection it is hollow and without practice it is empty.

As ideology is not mere theory but impacts directly on practice (Eagleton, 1991) there is a strongly practical methodology implied by critical theory, which articulates with action research (Callawaert, 1999). Action research (discussed in Chapter 18), as its name suggests, is about research that impacts on, and focuses on, practice. In its espousal of practitioner research, for example teachers in schools, participant observers and curriculum developers, action research recognizes the significance of contexts for practice – locational, ideological, historical, managerial, social. Furthermore it accords power to those who are operating in those contexts, for they are both the engines of research and of practice. In that sense the claim is made that action research is strongly empowering and emancipatory in that it gives practitioners a ‘voice’ (Carr and Kemmis, 1986; Grundy, 1987), participation in decision making, and control over their environment and professional lives. Whether the strength of the claims for empowerment are as strong as their proponents would hold is another matter, for action research might be relatively powerless in the face of mandated changes in education. Here action research might be more concerned with intervening in existing practice to ensure that mandated change is addressed efficiently and effectively.

Morrison (1995a) suggests that critical theory, because it has a practical intent to transform and empower, can – and should – be examined and perhaps tested empirically. For example, critical theory claims to be empowering; that is a testable proposition. Indeed, in a departure from some of his earlier writing, Habermas (1990) acknowledges this; he argues for the need to find ‘counter examples’ (p. 6), to ‘critical testing’ (p. 7) and empirical verification (p. 117). He acknowledges that his views have only ‘hypothetical status’ (p. 32) that need to be checked against specific cases (p. 9). One could suggest, for instance, that the effectiveness of his critical theory can be examined by charting the extent to which equality, freedom, democracy, emancipation, empowerment have been realized by dint of his theory; the extent to which transformative practices have been addressed or occurred as a result of his theory; the extent to which subscribers to his theory have been able to assert their agency; the extent to which his theories have broken down the barriers of instrumental rationality. The operationalization and testing (or empirical investigation) of his theories clearly is a major undertaking, and one which Habermas has not done. In this respect critical theory, a theory that strives to improve practical living, runs the risk of becoming merely contemplative.

There are several criticisms that have been voiced against critical approaches. Morrison (1995a) suggests that there is an artificial separation between Habermas’s three interests – they are drawn far more sharply (Hesse, 1982; Bernstein, 1983: 33). For example, one has to bring hermeneutic knowledge to bear on positivist science and vice versa in order to make meaning of each other and in order to judge their own status. Further, the link between ideology critique and emancipation is neither clear nor proven, nor a logical necessity (Morrison, 1995a: 67) – whether a person or society can become emancipated simply by the exercise of ideology critique or action research is an empirical rather than a logical matter (Morrison, 1995a; Wardekker and Miedama, 1997). Indeed one can become emancipated by means other than ideology critique; emancipated societies do not necessarily demonstrate or require an awareness of ideology critique. Moreover it could be argued that the rationalistic appeal of ideology critique actually obstructs action designed to bring about emancipation. Roderick (1986: 65), for example, questions whether the espousal of ideology critique is itself as ideological as the approaches that it proscribes. Habermas, in his allegiance to the view of the social construction of knowledge through ‘interests’, is inviting the charge of relativism.

Whilst the claim to there being three forms of knowledge has the epistemological attraction of simplicity, one has to question this very simplicity (e.g. Keat, 1981: 67); there are a multitude of interests and ways of understanding the world and it is simply artificial to reduce these to three. Indeed it is unclear whether Habermas, in his three knowledge-constitutive interests, is dealing with a conceptual model, a political analysis, a set of generalities, a set of transhistorical principles, a set of temporally specific observations or a set of loosely defined slogans (Morrison, 1995a: 71) that survive only by dint of their ambiguity (Kolakowsi, 1978). Lakomski (1999) questions the acceptability of the consensus theory of truth on which Habermas’s work is premised (pp. 179–82); she argues that Habermas’s work is silent on social change, and is little more than speculation, a view echoed by Fendler’s (1999) criticism of critical theory as inadequately problematizing subjectivity and ahistoricity.

More fundamental to a critique of this approach is the view that critical theory has a deliberate political agenda, and that the task of the researcher is not to be an ideologue or to have an agenda, but to be dispassionate, disinterested and objective (Morrison, 1995a). Of course, critical theorists would argue that the call for researchers to be ideologically neutral is itself ideologically saturated with laissez-faire values which allow the status quo to be reproduced, i.e. that the call for researchers to be neutral and disinterested is just as value-laden as is the call for them to intrude their own perspectives. The rights of the researcher to move beyond disinterestedness are clearly contentious, though the safeguard here is that the researcher’s is only one voice in the community of scholars (Kemmis, 1982). Critical theorists as researchers have been hoisted by their own petard, for if they are to become more than merely negative Jeremiahs and sceptics, berating a particular social order that is dominated by scientism and instrumental rationality (Eagleton, 1991; Wardekker and Miedama, 1997), then they have to generate a positive agenda, but in so doing they are violating the traditional objectivity of researchers. Because their focus is on an ideological agenda, they themselves cannot avoid acting ideologically (Morrison, 1995a).

Claims have been made for the power of action research to empower participants as researchers (e.g. Carr and Kemmis, 1986; Grundy, 1987). This might be over-optimistic in a world in which power is often through statute; the reality of political power seldom extends to teachers. That teachers might be able to exercise some power in schools but that this has little effect on the workings of society at large was caught in Bernstein’s (1970) famous comment that ‘education cannot compensate for society’. Giving action researchers a small degree of power (to research their own situations) has little effect on the real locus of power and decision making, which often lies outside the control of action researchers. Is action research genuinely and full-bloodedly empowering and emancipatory? Where is the evidence?

For research methods, the tenets of critical theory suggest their own substantive fields of enquiry and their own methods (e.g. ideology critique and action research). Beyond that the contribution to this text on empirical research methods is perhaps limited by the fact that the agenda of critical theory is highly particularistic, prescriptive and, as has been seen, problematical. Though it is an influential paradigm, it is influential in certain fields rather than in others. For example its impact on curriculum research has been far-reaching.

It has been argued for many years that the most satisfactory account of the curriculum is given by a modernist, positivist reading of the development of education and society. This has its curricular expression in Tyler’s (1949) famous and influential rationale for the curriculum in terms of four questions:

1 What educational purposes should the school seek to attain?

2 What educational experiences can be provided that are likely to attain these purposes?

3 How can these educational experiences be effectively organized?

4 How can we determine whether these purposes are being attained?

Underlying this rationale is a view that the curriculum is controlled (and controllable), ordered, predetermined, uniform, predictable and largely behaviourist in outcome – all elements of the positivist mentality that critical theory eschews. Tyler’s rationale resonates sympathetically with a modernist, scientific, managerialist mentality of society and education that regards ideology and power as unproblematic, indeed it claims the putative political neutrality and objectivity of positivism (Doll, 1993); it ignores the advances in psychology and psychopedagogy made by constructivism.

However, this view has been criticized for precisely these sympathies. Doll (1993) argues that it represents a closed system of planning and practice that sits uncomfortably with the notion of education as an opening process and with the view of postmodern society as open and diverse, multidimensional, fluid and with power less monolithic and more problematical. This view takes seriously the impact of chaos and complexity theory and derives from them some important features for contemporary curricula. These are incorporated into a view of curricula as being rich, relational, recursive and rigorous (Doll, 1993) with an emphasis on emergence, process epistemology and constructivist psychology.

Not all knowledge can be included in the curriculum; the curriculum is a selection of what is deemed to be worthwhile knowledge. The justification for that selection reveals the ideologies and power in decision making in society and through the curriculum. Curriculum is an ideological selection from a range of possible knowledge. This resonates with Habermas’s (1972) view that knowledge and its selection is neither neutral nor innocent.

Ideologies can be treated unpejoratively as sets of beliefs or, more sharply, as sets of beliefs emanating from powerful groups in society, designed to protect the interests of the dominant. If curricula are value-based then why is it that some values hold more sway than others? The link between values and power is strong. This theme asks not only what knowledge is important but whose knowledge is important in curricula, what and whose interests such knowledge serves, and how the curriculum and pedagogy serve (or do not serve) differing interests. Knowledge is not neutral (as was the tacit view in modernist curricula). The curriculum is ideologically contestable terrain.

The study of the sociology of knowledge indicates how the powerful might retain their power through curricula and how knowledge and power are legitimated in curricula. The study of the sociology of knowledge suggests that the curriculum should be both subject to ideology critique and itself promote ideology critique in students. A research agenda for critical theorists, then, is how the curriculum perpetuates the societal status quo and how can it (and should it) promote equality in society.

The notion of ideology critique engages the early writings of Habermas (1972), in particular his theory of three knowledge-constitutive interests. His technical interest (in control and predictability) resonates with Tyler’s model of the curriculum and reveals itself in technicist, instrumentalist and scientistic views of curricula that are to be ‘delivered’ to passive recipients – the curriculum is simply another commodity in a consumer society in which differential cultural capital is inevitable. Habermas’s hermeneutic interest (in understanding others’ perspectives and views) resonates with a process view of the curriculum. His emancipatory interest (in promoting social emancipation, equality, democracy, freedoms and individual and collective empowerment) requires an exposure of the ideological interests at work in curricula in order that teachers and students can take control of their own lives for the collective, egalitarian good. Habermas’s emancipatory interest denotes an inescapably political reading of the curriculum and the purposes of education – the movement away from authoritarianism and elitism and towards social democracy.

Habermas’s work underpins and informs much curriculum theory (e.g. Grundy, 1987; Apple, 1990; UNESCO, 1996) and is a useful heuristic device for understanding the motives behind the heavy prescription of curriculum content in, for example, the UK, New Zealand, Hong Kong and France. For instance, one can argue that the National Curriculum of England and Wales is heavy on the technical and hermeneutic interests but very light on the emancipatory interest (Morrison, 1995a), and that this (either deliberately or in its effects) supports – if not contributes to – the reproduction of social inequality. As Bernstein (1971: 47) argues: ‘how a society selects, classifies, distributes, transmits and evaluates the educational knowledge it considers to be public, reflects both the distribution of power and the principles of social control’.

Several writers on curriculum theory (e.g. McLaren, 1995; Leistyna et al., 1996) argue that power is a central, defining concept in matters of the curriculum. Here considerable importance is accorded to the political agenda of the curriculum, and the empowerment of individuals and societies is an inescapable consideration in the curriculum. One means of developing student and societal empowerment finds its expression in Habermas’s (1972) emancipatory interest and critical pedagogy.

In the field of critical pedagogy the argument is advanced that educators must work with, and on, the lived experience that students bring to the pedagogical encounter rather than imposing a dominatory curriculum that reproduces social inequality. In this enterprise teachers are to transform the experience of domination in students and empower them to become ‘emancipated’ in a full democracy. Students’ everyday experiences of oppression, of being ‘silenced’, of having their cultures and ‘voices’ excluded from curricula and decision making are to be examined for the ideological messages that are contained in such acts. Raising awareness of such inequalities is an important step to overcoming them. Teachers and students together move forward in the progress towards ‘individual autonomy within a just society’ (Masschelein, 1991: 97). In place of centrally prescribed and culturally biased curricula that students simply receive, critical pedagogy regards the curriculum as a form of cultural politics in which participants in (rather than recipients of ) curricula question the cultural and dominatory messages contained in curricula and replace them with a ‘language of possibility’ and empowering, often community-related curricula. In this way curricula serve the ‘socially critical’ rather than the culturally and ideologically passive school.

One can discern a utopian and generalized tenor in some of this work, and applying critical theory to education can be criticized for its limited comments on practice. Indeed Miedama and Wardekker (1999: 68) go so far as to suggest that critical pedagogy has had its day, that it was a stillborn child and that critical theory is a philosophy of science without a science (p. 75)! Nevertheless it is an important field for it recognizes and makes much of the fact that curricula and pedagogy are problematical and political.

The call to action in research, particularly in terms of participatory action, and particularly in respect of oppressed, disempowered, underprivileged and exploited groups finds its research voice in terms of participatory research (PR) (e.g. Freire, 1972; Giroux, 1989). Here the groups (e.g. community groups) themselves establish and implement interventions to bring about change, development and improvement to their lives, acting collectively rather than individually.

Participatory research, an instance of critical theory in research, breaks with conventional ways of construing research, as it concerns doing research with people and communities rather than doing research to or for people and communities. It is premised on the view that research can be conducted by everyday people rather than an elite group of researchers; that ordinary people are entirely capable of reflective and critical analysis of their situation (Pinto, 2000: 7). It is profoundly democratic, with all participants as equals; it strives for a participatory rather than a representative democracy (Giroux, 1983, 1989). PR regards power as shared and equalized, rather than as the property of an elite, and the researcher shares his or her humanity with the participants (Tandon, 2005a: 23). In PR, the emphasis is on research for change and development of communities rather than for its own sake, i.e. emphasis is placed on knowledge that is useful in improving lives rather than for the interests and under the control of the academic or the researcher. It is research with a practical intent, for the transformation of lives and communities; it makes the practical more political and the political more practical (cf. Giroux, 1983). As Tandon (2005a: 23) writes: ‘the very act of inquiry tends to have some impact on the social system under study’.

Campbell (2002: 20) suggests that participatory research arose in the 1970s, as a reaction to those western researchers and developers who adopted a ‘top-down’ approach to working with local communities, neglecting and relegating their local knowledge and neglecting their empowerment and improvement. Rather, PR is emancipatory (p. 20), eclectic and, like mixed methods research, adopts whatever research methodology will deliver the results that will enable action and local development to follow. As with mixed methods research and action research, it is pragmatic, and, if necessary, sacrifices ‘rigorous control, for the sake of “pragmatic utility”’ (Brown, 2005a: 92). PR challenges the conventional distance between researchers and participants; together they work for local development. It has as its focus micro-development rather than macro-development, using knowledge to pursue well-being rather than truth (Tandon, 2005b: ix; Brown, 2005a: 98).

Participatory research respects the indigenous, popular knowledge that resides in members of communities, rather than the relatively antiseptic world and knowledge of the expert researcher. Indeed it is, like Freire’s work, itself educative. Local community knowledge is legitimized and re-legimitized in PR (Pinto, 2000: 21), and participants are active and powerful in the research rather than passive subjects. Local people can transform their lives through knowledge and their use of that knowledge; knowledge is power, with local members of the community collectively being active and in control. Researchers are facilitators, catalysts and change agents rather than assuming dominatory or controlling positions (Pinto, 2000: 13). The agenda of PR is empowerment of all and liberation from oppression, exploitation and poverty. Research here promotes both understanding and also change. As one of its proponents, Lewin (1946: 34) wrote: ‘if you want truly to understand something, try to change it’. PR blends knowledge and action (Tandon, 2005c: 49).

Participatory research recognizes the centrality of power in research and everyday life, and has an explicit agenda of wresting power from those elites who hold it, and returning it to the grassroots, the communities, the mainstream citizenry. As Pinto (2000: 13) remarks, a core feature that runs right through all stages of PR is the nagging question of ‘who controls?’.

Participatory research has as its object the betterment of communities, societies and groups, often the disempowered, oppressed, impoverished and exploited communities, groups and societies, the poor, the ‘have-nots’ (Hall, 2005: 10; Tandon, 2005c:50). Its principles concern improvement, group decision-making, the need for research to have a practical outcome that benefits communities and in which participants are agents of their own decisions (Hall, 2005: 10; INCITE, 2010). It starts with problems as experienced in the local communities or workplace, and brings together into an ongoing working relationship both researchers and participants. As Bryceson et al. (2005: 183) remark, PR is a ‘three-pronged activity: an approach to social investigation with the full and active participation of the community in the entire research process; a means of taking action for development; and an educational process of mobilization for development, all of which are closely interwoven with each other’.

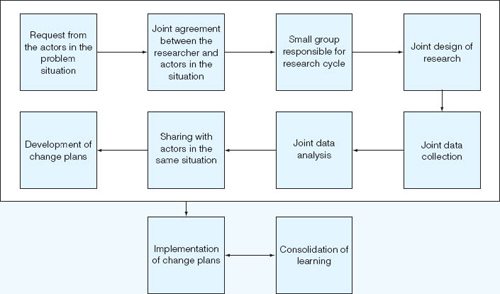

The essence of participatory research, as its name suggests, is participation, the equal control of the research by both participants and researchers and the movement towards change through empowerment. These features enter all stages of the research, from identification of problems to the design of the research, the implementation of the research, the data analysis, the reporting, and catalysed changes and developments in the community. Empowerment and development are both the medium and the outcome of the research. Tandon (2005c: 30) sets out a sequence for PR as shown in Figure 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1 Steps in an ‘ideal’ participatory research approach

Source: Tandon, 2005c: 30. reproduced with permission of Mosaic Books, new Delhi

Whilst conventional approaches to data collection may have their value (e.g. surveys, interviews), too often these are instruments that regard people solely as sources of information rather than as participants in their own community development (Hall, 2005: 13). Indeed Tandon (2005d: 106) reports that, in many cases, surveys are entirely irrelevant to the communities involved in the research, and alternative forms of collecting data have to be used (e.g. dialogue (Tandon, 2005e); enumeration such as census data (though, clearly these are used in conventional research) (Batliwala and Patel, 2005); and popular theatre for consciousness-raising (Khot, 2005)). Hall cites the example of the UNESCO evaluation of the Experimental World Literacy Programme, in which local expertise was neglected, which oversimplified the phenomena under investigation, and disempowered the very communities under review. Such research is alienating rather than empowering. Rather, Hall avers, each should respect, and take seriously, resident knowledge (he gives the example of adult learning).

Hall (2005: 17–19) sets out several principles for participatory research:

1 A research project – both process and results – can be of immediate and direct benefit to a community (as opposed to serving merely as the basis of an academic paper of obscure policy analysis).

2 A research project should involve the community in the entire research project, from the formulation of the problem and the interpretation of the findings to planning corrective action based upon them.

3 The research process should be seen as part of a total educational experience which serves to determine community needs, and to increase awareness of problems and commitment to solutions within the community.

4 Research should be viewed as a dialectic process, a dialogue over time, and not a static picture of reality at one point in time.

5 The object of research, like the object of education, should be the liberation of human creative potential and the mobilization of human resources for the solution of social problems.

6 Research has ideological implications. . . . First is the re-affirmation of the political nature of all we do. . . . Research that allows for popular involvement and increased capacities of analysis will also make conflictual action possible, or necessary.

(Hall, 2005: 17–19)

In participatory research the problem to be investigated originates in, and is defined by, the community or workplace. The members of that community or workplace are involved in the research and have control over it, and the research leads to development and improvement of their lives and communities (Brown and Tandon, 2005: 55). Brown and Tandon (p. 60) recognize the challenge (and likely resistance) that these principles might pose for the powerful, specific dominant interest groups, but they argue that this is unavoidable, as the researcher typically mobilizes community groups to action (p. 61). Hence PR has to consider the likely responses of the researchers, the participants and their possible opponents (p. 62); as Giroux (1983) avers, knowledge is not only powerful, but dangerous, and participants may run substantial risks (Brown and Tandon, 2005: 65) in conducting this type of research, for it upsets existing power structures in society and the workplace.

As can be seen, participatory research has some affinity to action research (INCITE, 2010), though it is intensely more political than action research. It is not without its critics. For example Brown (2005b) argues that participatory action research is ambiguous about:

a its research objectives (e.g. social change, raising awareness, development work, challenging conventional research paradigms);

b the relationships between the researcher and participants (e.g. overemphasizing similarities and neglecting differences between them);

c the methods and technologies that it uses (e.g. being overcritical of conventional approaches which might serve the interests of participatory research, and the lack of a clear method for data collection); and

d the outcomes of participatory research (e.g. what these are, when these are decided, and who decides).

These notwithstanding, however, PR has much to commend it in the everyday sphere of education, and it is a clear instance of the tenets of critical theory, transformative action and empowerment put into practice.

It is perhaps no mere coincidence that feminist research should surface as a serious issue at the same time as ideology-critical paradigms for research; they are closely connected. Usher (1996), although criticizing Habermas (p. 124) for his faith in family life as a haven from a heartless, exploitative world, nevertheless sets out several principles of feminist research that resonate with the ideology critique of the Frankfurt School:

1 The acknowledgement of the pervasive influence of gender as a category of analysis and organization.

2 The deconstruction of traditional commitments to truth, objectivity and neutrality.

3 The adoption of an approach to knowledge creation which recognizes that all theories are perspectival.

4 The utilization of a multiplicity of research methods.

5 The interdisciplinary nature of feminist research.

6 Involvement of the researcher and the people being researched.

7 The deconstruction of the theory/practice relationship.

Her suggestions build on earlier recognition of the significance of addressing the ‘power issue’ in research (‘whose research’, ‘research for whom’, ‘research in whose interests’) and the need to address the emancipatory element of educational research – that research should be empowering to all participants. The paradigm of critical theory questioned the putative objective, neutral, value-free, positivist, ‘scientific’ paradigm for the splitting of theory and practice and for its reproduction of asymmetries of power (reproducing power differentials in the research community and for treating participants/respondents instrumentally – as objects).

Robson (1993: 64) suggests seven sources of sexism in research:

androcentricity: seeing the world through male eyes and applying male research paradigms to females;

overgeneralization: when a study generalizes from males to females;

gender insensitivity: ignoring sex as a possible variable;

double standards: using male criteria, measures and standards to judge the behaviour of women and vice versa (e.g. in terms of social status);

sex appropriateness: e.g. that child-rearing is women’s responsibility;

familism: treating the family, rather than the individual, as the unit of analysis;

sexual dichotomism: treating the sexes as distinct social groups when, in fact, they may share characteristics.

Feminist research, too, challenges the legitimacy of research that does not empower oppressed and otherwise invisible groups – women. Ezzy (2002: 20) writes of the need to replace a traditional masculine picture of science with an emancipatory commitment to knowledge that stems from a feminist perspective, since, ‘if women’s experience is analyzed using only theories and observations from the standpoint of men, the resulting theories oppress women’ (p. 23). Gender, as Ezzy writes (p. 43), is ‘a category of experience’.

Positivist research served a given set of power relations, typically empowering the white, male-dominated research community at the expense of other groups whose voices were silenced. Feminist research seeks to demolish and replace this with a different substantive agenda – of empowerment, voice, emancipation, equality and representation for oppressed groups. In doing so, it recognizes the necessity for foregrounding issues of power, silencing and voicing, ideology critique and a questioning of the legitimacy of research that does not emancipate hitherto disempowered groups. In feminist research, women’s consciousness of oppression, exploitation and disempowerment becomes a focus for research – the paradigm of ideology critique.

Far from treating educational research as objective and value-free, feminists argue that this is merely a smokescreen that serves the existing, disempowering status quo, and that the subject and value-laden nature of research must be surfaced, exposed and engaged (Haig, 1999: 223). Supposedly value-free, neutral research perpetuates power differentials. Indeed Jayaratne and Stewart (1991) question the traditional, exploitative nature of much research in which the researchers receive all the rewards whilst the participants remain in their – typically powerless – situation, i.e. in which the status quo of oppression, underprivilege and inequality remain undisturbed. As Scott (1985: 80) writes: ‘we may simply use other women’s experiences to further our own aims and careers’. Creswell (1998: 83), too, suggests that feminist research strives to establish collaborative and non-exploitative relationships. Indeed Scott (1985) questions how ethical it is for a woman researcher to interview those who are less privileged and more exploited than she herself is.

Changing this situation entails taking seriously issues of reflexivity, the effects of the research on the researched and the researchers, the breakdown of the positivist paradigm, and the raising of consciousness of the purposes and effects of the research. Ezzy (2002: 153) writes that ‘the personal experience of the researcher is an integral part of the research process’, and reinforces the point that objectivity is a false claim by researchers.

Ribbens and Edwards (1997) suggest that it is important to ask how researchers can produce work with reference to theoretical perspectives and formal traditions and requirements of public, academic knowledge whilst still remaining faithful to the experiences and accounts of research participants. Denzin (1989), Mies (1993), Haig (1999) and De Laine (2000) argue for several principles in feminist research:

the asymmetry of gender relations and representation must be studied reflexively as constituting a fundamental aspect of social life (which includes educational research);

the asymmetry of gender relations and representation must be studied reflexively as constituting a fundamental aspect of social life (which includes educational research);

women’s issues, their history, biography and biology, feature as a substantive agenda/focus in research – moving beyond mere perspectival/methodological issues to setting a research agenda;

women’s issues, their history, biography and biology, feature as a substantive agenda/focus in research – moving beyond mere perspectival/methodological issues to setting a research agenda;

the raising of consciousness of oppression, exploitation, empowerment, equality, voice and representation is a methodological tool;

the raising of consciousness of oppression, exploitation, empowerment, equality, voice and representation is a methodological tool;

the acceptability and notion of objectivity and objective research must be challenged;

the acceptability and notion of objectivity and objective research must be challenged;

the substantive, value-laden dimensions and purposes of feminist research must be paramount;

the substantive, value-laden dimensions and purposes of feminist research must be paramount;

research must empower women;

research must empower women;

research need not only be undertaken by academic experts;

research need not only be undertaken by academic experts;

collective research is necessary – women need to collectivize their own individual histories if they are to appropriate these histories for emancipation;

collective research is necessary – women need to collectivize their own individual histories if they are to appropriate these histories for emancipation;

there is a commitment to revealing core processes and recurring features of women’s oppression

there is a commitment to revealing core processes and recurring features of women’s oppression

an insistence on the inseparability of theory and practice;

an insistence on the inseparability of theory and practice;

an insistence on the connections between the private and the public, between the domestic and the political;

an insistence on the connections between the private and the public, between the domestic and the political;

a concern with the construction and reproduction of gender and sexual difference;

a concern with the construction and reproduction of gender and sexual difference;

a rejection of narrow disciplinary boundaries;

a rejection of narrow disciplinary boundaries;

a rejection of the artificial subject/researcher dualism;

a rejection of the artificial subject/researcher dualism;

a rejection of positivism and objectivity as male mythology;

a rejection of positivism and objectivity as male mythology;

the increased use of qualitative, introspective biographical research techniques;

the increased use of qualitative, introspective biographical research techniques;

a recognition of the gendered nature of social research and the development of anti-sexist research strategies;

a recognition of the gendered nature of social research and the development of anti-sexist research strategies;

a review of the research process as consciousness-and awareness-raising and as fundamentally participatory;

a review of the research process as consciousness-and awareness-raising and as fundamentally participatory;

the primacy of women’s personal subjective experience;

the primacy of women’s personal subjective experience;

the rejection of hierarchies in social research;

the rejection of hierarchies in social research;

the vertical, hierarchical relationships of researchers/research community and research objects, in which the research itself can become an instrument of domination and the reproduction and legitimation of power elites has to be replaced by research that promotes the interests of dominated, oppressed, exploited groups;

the vertical, hierarchical relationships of researchers/research community and research objects, in which the research itself can become an instrument of domination and the reproduction and legitimation of power elites has to be replaced by research that promotes the interests of dominated, oppressed, exploited groups;

the recognition of equal status and reciprocal relationships between subjects and researchers;

the recognition of equal status and reciprocal relationships between subjects and researchers;

there is a need to change the status quo, not merely to understand or interpret it;

there is a need to change the status quo, not merely to understand or interpret it;

the research must be a process of conscientization, not research solely by experts for experts, but to empower oppressed participants.

the research must be a process of conscientization, not research solely by experts for experts, but to empower oppressed participants.

Indeed Webb et al. (2004) set out six principles for a feminist pedagogy in the teaching of research methodology:

1 Reformulation of the professor–student relationship (from hierarchy to equality and sharing).

2 Empowerment (for a participatory democracy).

3 Building community (through collaborative learning).

4 Privileging the individual voice (not only the lecturer’s).

5 Respect for diversity of personal experience (rooted, for example, in gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexual preference).

6 Challenging traditional views (e.g. the sociology of knowledge).

Gender shapes research agendas, the choice of topics and foci, the choice of data collection techniques and the relationships between researchers and researched. Several methodological principles flow from a ‘rationale’ for feminist research (Denzin, 1989; Mies, 1993; Haig, 1997; 1999; De Laine, 2000):

the replacement of quantitative, positivist, objective research with qualitative, interpretive, ethnographic reflexive research, as objectivity in quantitative research is a smokescreen for masculine interests and agendas;

the replacement of quantitative, positivist, objective research with qualitative, interpretive, ethnographic reflexive research, as objectivity in quantitative research is a smokescreen for masculine interests and agendas;

collaborative, collectivist research undertaken by collectives – often of women – combining researchers and researched in order to break subject/object and hierarchical, non-reciprocal relationships;

collaborative, collectivist research undertaken by collectives – often of women – combining researchers and researched in order to break subject/object and hierarchical, non-reciprocal relationships;

the appeal to alleged value-free, neutral, indifferent and impartial research has to be replaced by conscious, deliberate partiality – through researchers identifying with participants;

the appeal to alleged value-free, neutral, indifferent and impartial research has to be replaced by conscious, deliberate partiality – through researchers identifying with participants;

the use of ideology-critical approaches and paradigms for research;

the use of ideology-critical approaches and paradigms for research;

the spectator theory or contemplative theory of knowledge in which researchers research from ivory towers has to be replaced by a participatory approach – perhaps action research – in which all participants (including researchers) engage in the struggle for women’s emancipation – a liberatory methodology;

the spectator theory or contemplative theory of knowledge in which researchers research from ivory towers has to be replaced by a participatory approach – perhaps action research – in which all participants (including researchers) engage in the struggle for women’s emancipation – a liberatory methodology;

the need to change the status quo is the starting point for social research – if we want to know something we change it. (Mies (1993) cites the Chinese saying that if you want to know a pear then you must chew it!);

the need to change the status quo is the starting point for social research – if we want to know something we change it. (Mies (1993) cites the Chinese saying that if you want to know a pear then you must chew it!);

the extended use of triangulation and multiple methods (including visual techniques such as video, photograph and film);

the extended use of triangulation and multiple methods (including visual techniques such as video, photograph and film);

the use of linguistic techniques such as conversational analysis;

the use of linguistic techniques such as conversational analysis;

the use of textual analysis such as deconstruction of documents and texts about women;

the use of textual analysis such as deconstruction of documents and texts about women;

the use of meta-analysis to synthesize findings from individual studies (see Chapter 17);

the use of meta-analysis to synthesize findings from individual studies (see Chapter 17);

a move away from numerical surveys and a critical evaluation of them, including a critique of question wording.

a move away from numerical surveys and a critical evaluation of them, including a critique of question wording.

Edwards and Mauthner (2002: 15, 27) characterize feminist research as that which concerns a critique of dominatory and value-free research, the surfacing and rejection of exploitative power hierarchies between the researcher and the participants, and the espousal of close – even intimate – relationships between the researcher and the researched. Positivist research is rejected as per se oppressive (Gillies and Alldred, 2002: 34) and inherently unable to abide by its own principle of objectivity; it is a flawed epistemology. Research, and its underpinning epistemologies, are rooted in, and inseparable from, interests (Habermas, 1972).

The move is towards ‘participatory action research’ in which empowerment and emancipation are promoted and which is an involved and collaborative process (e.g. De Laine, 2000: 109ff.). Participation recognizes ‘power imbalances and the need to engage oppressed people as agents of their own change’ (Ezzy, 2002: 44), whilst action research recognizes the value of ‘using research findings to inform intervention decisions’ (p. 44). As De Laine (2000: 16) writes: the call is ‘for more participation and less observation, of being with and for the other, not looking at’, with relations of reciprocity and equality rather than impersonality, exploitation and power/status differentials between researcher and participants.

The relationship between the researcher and participant, De Laine (2000) argues, must break a conventional patriarchy. The emphasis is on partnerships between researchers and participants (p. 107), to the extent that researchers are, themselves participants rather than outsiders and the participants shape the research process as co-researchers (p. 107), defining the problem, the methods, the data collection and analysis, interpretation and dissemination. The relationship between researchers and participants is one of equality, and outsider, objective, distant, positivist research relations are off the agenda; researchers are inextricably bound up in the lives of those they research. That this may bring difficulties in participant and researcher reactivity is a matter to be engaged in rather than built out of the research.

Thapar-Björkert and Henry (2004) argue that the conventional, one-sided and unidirectional view of the researcher as powerful and the research participants as less powerful, with the researcher exploiting and manipulating the researched, could be a construction by western white researchers. They report research that indicates that power is exercised by the researched as well as the researchers, and is a much more fluid, shifting and negotiated matter than conventionally suggested, being dispersed through both the researcher and the researched. Indeed they show how the research participants can, and do, exercise considerable power over the researchers, both before, during and after the research process. They provide a fascinating example of interviewing women in their homes in India, where, far from the home being a location of oppression, was a site of their power and control.

With regard to methods of data collection, Oakley (1981) suggests that ‘interviewing women’ in the standardized, impersonal style which expects a response to a prescribed agenda and set of questions may be a ‘contradiction in terms’, as it implies an exploitative relationship. Rather, the subject/object relationship should be replaced by a guided dialogue. She criticizes the conventional notion of ‘rapport’ in conducting interviews (p. 35), arguing that they are instrumental, non-reciprocal and hierarchical, all of which are masculine traits. Rapport in this sense, she argues, is not genuine in that the researcher is using it for scientific rather than human ends (p. 55). Here researchers are ‘faking friendship’ for their own ends (Duncombe and Jessop, 2002: 108), equating ‘doing rapport’ with trust, and, thereby, operating a very ‘detached’ form of friendship (p. 110). Similarly Thapar-Björkert and Henry (2004) suggest that attempts at friendship between researchers and participants are disingenuous, with ‘purported solidarity’ being a fraud perpetrated by well-intentioned feminists.

Duncombe and Jessop (2002: 111) ask a very searching question when they query whether, if inter viewees are persuaded to take part in an interview by virtue of the researcher’s demonstration of empathy and ‘rapport’, this is really given informed consent. They suggest that informed consent, particularly in exploratory interviews, has to be continually renegotiated and care has to be taken by the interviewer not to be too intrusive. Personal testimonies, oral narratives and long interviews also figure highly in feminist approaches (De Laine, 2000: 110; Thapar-Björkert and Henry, 2004), not least in those that touch on sensitive issues. These, it is argued (Ezzy, 2002: 45), enable women’s voices to be heard, to be close to lived experiences and avoid unwarranted assumptions about people’s experiences.

The drive towards collective, egalitarian and emancipatory qualitative research is seen as necessary if women are to avoid colluding in their own oppression by undertaking positivist, uninvolved, dispassionate, objective research. Mies (1993: 67) argues that for women to undertake this latter form of research puts them into a schizophrenic position of having to adopt methods which contribute to their own subjugation and repression by ignoring their experience (however vicarious) of oppression and by forcing them to abide by the ‘rules of the game’ of the competitive, male-dominated academic world. In this view, argue Roman and Apple (1990: 59), it is not enough for women simply to embrace ethnographic forms of research, as this does not necessarily challenge the existing and constituting forces of oppression or asymmetries of power. Ethnographic research, they argue, has to be accompanied by ideology critique, indeed they argue that the transformative, empowering, emancipatory potential of research is a critical standard for evaluating that piece of research.

This latter point resonates with the call by Lather (1991) for researchers to be concerned with the political consequences of their research (e.g. consequential validity), not only the conduct of the research and data analysis itself. Research must lead to change and improvement, particularly, in this context, for women (Gillies and Alldred, 2002: 32). Research is a political activity with a political agenda (Gillies and Alldred, 2002: 33; see also Lather, 1991). Research and action – praxis – must combine: ‘knowledge for’ as well as ‘knowledge what’ (Ezzy, 2002: 47). As Marx reminds us in his Theses on Feuerbach: ‘the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it’. Gillies and Alldred (2002: 45), however, point out that ‘many feminists have agonized over whether politicizing participants is necessarily helpful’, as it raises awareness of constraints on their actions without being able to offer solutions or to challenge their structural causes. Research, thus politicized but unable to change conditions, may actually be disempowering and, indeed, patronizing in its simplistic call for enlightenment and emancipation. It could render women more vulnerable than before. Emancipation is a struggle.

Several of these views of feminist research and methodology are contested by other feminist researchers. For example Jayaratne (1993: 109) argues for ‘fitness for purpose’, suggesting that exclusive focus on qualitative methodologies might not be appropriate either for the research purposes or, indeed, for advancing the feminist agenda (see also Scott, 1985: 82–3). Jayaratne refutes the argument that quantitative methods are unsuitable for feminists because they neglect the emotions of the people under study. Indeed she argues for beating quantitative research on its own grounds (p. 121), suggesting the need for feminist quantitative data and methodologies in order to counter sexist quantitative data in the social sciences. She suggests that feminist researchers can accomplish this without ‘selling out’ to the positivist, male-dominated academic research community. Indeed Oakley (1998) suggests that the separation of women from quantitative methodology may have the unintended effect of perpetuating women as the ‘other’, and, thereby, discriminating against them, and Finch (2004) argues that, whilst qualitative research might have helped to establish the early feminist movement, it is important to recognize the place of both quantitative and qualitative methods to be the stuff of feminist research.

De Laine (2000: 112) argues that shifting from quantitative to qualitative techniques may not solve many ethical problems in research, as these are endemic in any form of fieldwork. She argues that some feminist researchers may not wish to seek either less participation or more detachment, and that more detachment and less participation are not solutions to ethical dilemmas and ‘morally responsible fieldwork’ as these, too, bring their own ethical dilemmas, e.g. the risk of threat. She reports work (p. 113) that suggests that close relationships between researchers and participants may be construed as just as exploitative, if more disguised, as conventional researcher roles, and that they may bring considerable problems if data that were revealed in an intimate account between friends (researcher and participant) are then used in public research. The researcher is caught in a dilemma: if she is a true friend then this imposes constraints on the researcher, and yet if she is only pretending to be a friend, or limiting that friendship, then this provokes questions of honesty and personal integrity. Are research friendships real, ephemeral or impression management used to gather data?

De Laine (2000: 115) suggests that it may be misguided to privilege qualitative research for its claim to non-exploitative relationships. Whilst she acknowledges that quantitative approaches may perpetuate power differentials and exploitation, there is no guarantee that qualitative research will not do the same, only in a more disguised way. Qualitative approaches too, she suggests, can create and perpetuate unequal relations, not least simply because the researcher is in the field qua researcher rather than a friend; if it were not for the research then the researcher would not be present. Stacey (1988) suggests that the intimacy advocated for feminist ethnography may render exploitative relationships more rather than less likely. We refer readers to Chapter 9 on sensitive educational research for a further discussion of these issues.

Gillies and Alldred (2002: 43–6) suggest that action research, an area strongly supported in some quarters of feminist researchers, is, itself, problematic. It risks being an intervention in people’s lives (i.e. a potential abuse of power), and the researcher typically plays a significant, if not central, role in initiating, facilitating, crystallizing and developing the meanings involved in, or stemming from, the research, i.e. the researcher is the one exercising power and influence.

Ezzy (2002: 44) reports that, just as there is no single feminist methodology, both quantitative and qualitative methods are entirely legitimate. Indeed, Kelly (1978) argues that a feminist commitment should enter research at the stages of formulating the research topic and interpreting the results, but it should be left out during the stages of data collection and conduct of the research.

Thapar-Björkert and Henry (2004) indicate that the researcher being an outsider might bring more advantages than if she were an insider. For example, being a white female researching non-white females may not be a handicap, as many non-white women might disclose information to white women that they would not disclose to a non-white person. Similarly, having interviewers and interviewees of the same racial and ethnic background does not mean that non-hierarchical relationships will still not be present. They also report that the categories of ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ were much more fuzzy than exclusive. Researchers are both ‘subject’ and ‘object’, and those being researched are both ‘observed’ and ‘observers’.

De Laine (2000: 110) suggests that there is a division amongst feminists between those who advocate closeness in relationships between researchers and subjects – a human researching fellow humans – and those who advocate ‘respectful distance’ between researchers and those being studied. Close relationships may turn into quasi-therapeutic situations rather than research (Duncombe and Jessop, 2002: 111), yet it may be important to establish closeness in reaching deeper issues. Further, one has to question how far close relationships lead to reciprocal and mutual disclosure (Duncombe and Jessop, 2002: 120). The debate is open: should the researcher share, be close and be prepared for more intimate social relations – a ‘feminist ethic of care’ (p. 111) – or keep those cool, outsider relations which might objectify those being researched? It is a moral as well as a methodological matter.

The issue runs deep: the suggestion is that emotions and feelings are integral to the research, rather than to be built out of the research in the interests of objectivity (Edwards and Mauthner, 2002: 19). Emotions should not be seen as disruptive of research or as irrelevant (De Laine, 2000: 151–2), but central to it, just as they are central to human life. Indeed emotional responses are essential in establishing the veracity of enquiries and data, and the ‘feminist communitarian model’ which De Laine (2002: 212–13) outlines values connectedness at several levels: emotions, emotionality and personal expressiveness, empathy. The egalitarian feminism that De Laine (2000) and others advocate suggests a community of insiders in the same culture, in which empathy, reciprocity and egalitarianism are hallmarks (p. 108).

Swantz (1996: 134) argues that there may be some self-deception by the researcher in adopting a dual role as a researcher and one who shares the situation and interests of the participants. She questions the extent to which the researcher may be able to be genuinely involved with the participants in other that a peripheral way and whether, simply because the researcher may have ‘superior knowledge’, a covert power differential may exist. De Laine (2000: 114) suggests that such superior knowledge may stem from the researcher’s own background in anthropology or ethnography, or simply more education. The primary purpose of the researcher is research, and that is different from the primary purpose of the participants.

Further, the researcher’s desire for identification and solidarity with her research subjects may be pious but unrealistic optimism, not least because she may not share the same race, ethnicity, background, life chances, experiences or colour as those being researched. Indeed Gillies and Alldred (2002: 39–40) raise the question of how far researchers can, or should, try to represent groups to which they themselves do not belong, not least those groups without power or voice, as this, itself, is a form of colonization and oppression. Affinity, they argue (p. 40), is no authoritative basis for representative research. Even the notion of affinity becomes suspect when it overlooks, or underplays, the significance of difference, thereby homogenizing groups and their particular experiences. In response to this, some feminist researchers (p. 40) suggest that researchers only have the warrant to confine themselves to their own immediate communities, though this is a contentious issue. There is value in speaking for others, not least for those who are silenced and marginalized, and in not speaking for others for fear of oppression and colonization. One has to question the acceptability and appropriateness of, and fidelity to, the feminist ethic, if one represents and uses others’ stories (p. 41).

An example of a feminist approach to research is the Girls Into Science and Technology (GIST) action research project. This took place over three years, involving 2,000 students and their teachers in ten coeducational, comprehensive schools in one area of the UK, eight schools serving as the bases of the ‘action’, the remaining two acting as ‘controls’. Several publications have documented the methodologies and findings of the GIST study (Whyte, 1986; Kelly, 1986, 1989a, 1989b; Kelly and Smail, 1986), described by its co-director as ‘simultaneous-integrated action research’ (Kelly, 1987) (i.e. integrating action and research). Kelly is open about the feminist orientation of the GIST project team, seeking deliberately to change girls’ option choices and career aspirations, because the researchers saw that girls were disadvantaged by traditional sex-stereotypes. The researchers’ actions, she suggests, were a small attempt to ameliorate women’s subordinate social position (Kelly, 1987).

Under the umbrella of critical theory also fall postcolonial theory, queer theory and critical race theory. Whilst this chapter does not unpack these, it notes them as avenues which educational researchers may wish to explore. For example, post-colonial theory, as its name suggests, with an affinity to postmodernism, addresses the experiences (often through film, literature, cultural studies, political and social sciences) of post-colonial societies and the cultural legacies of colonialism. It examines the after-effects, or continuation, of ideologies and discourses of imperialism, domination and repression, value systems (e.g. the domination of western values and the delegitimization of non-western values), their effects on the daily lived experiences of participants, i.e. their materiality, and the regard in which peoples in post-colonial societies are held (e.g. Said’s (1978) ground-breaking work on orientalism and the casting down of non-western groups as the ‘other’). It also discusses the valorization of multiple voices and heterogeneity in post-colonial societies, the resistance to marginalization of groups within them (Babha, 1994: 113) and the construction of identities in a post-colonial world.

Queer theory builds on, but moves beyond, feminist theory and gay/lesbian studies to explore the social construction and privileging or denial of identities, sexual behaviour, deviant behaviour and the categorizations and ideologies involved in such constructions. As Halperin (1997: 62) writes, queer theory ‘acquires its meaning from its oppositional relation to the norm. Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers. It is an identity without an essence. “Queer” then, demarcates not a positivity but a positionality vis-à-vis the normative.’ The task of queer theory, then, is to explore, problematize and interrogate gender, sexuality and also their mediation by other characteristics or forms of oppression, e.g. social class, ethnicity, colour, disability. It rejects simplistic categorization of individuals, and argues for the respect of their individuality and uniqueness.

The two chapters have discussed very different approaches to educational research, that rest on quantitative, qualitative and critical theoretical foundation, or a combination of these. Table 2.2 summarizes some of the broad differences between the three approaches that we have considered so far.

We present the paradigms and their affiliates in Figure 2.2.

Companion Website

Companion WebsiteThe companion website to the book includes PowerPoint slides for this chapter, which list the structure of the chapter and then provide a summary of the key points in each of its sections. This resource can be found online at www.routledge.com/textbooks/cohen7e.