defining action research

defining action researchAction research |

CHAPTER 18 |

Action research is a popular way in which teachers research their own institutions, staff development facilitators bring about change, and groups and communities undertake research. This chapter introduces key issues in the planning, conduct and reporting of action research, including:

defining action research

defining action research

principles and characteristics of action research

principles and characteristics of action research

participatory action research

participatory action research

action research as critical praxis

action research as critical praxis

action research and complexity theory

action research and complexity theory

procedures for action research

procedures for action research

reporting action research

reporting action research

reflexivity in action research

reflexivity in action research

some practical and theoretical matters

some practical and theoretical matters

The chapter draws links between action research and critical theory, in particular in respect of participatory action research. It also notes the connections between action research and complexity theory.

Action research, sometimes called practitioner based research (McNiff, 2002a: 6) is a powerful tool for change and improvement at the local level. Indeed, Kurt Lewin’s own work (one of action research’s founding fathers) was deliberately intended to change the life chances of disadvantaged groups in terms of housing, employment, prejudice, socialization and training. Its combination of action and research has contributed to its attraction to researchers, teachers and the academic and educational community alike.

The scope of action research as a method is impressive. It can be used in almost any setting where a problem involving people, tasks and procedures cries out for solution, or where some change of feature results in a more desirable outcome (cf. Bassey, 1998). It can be undertaken by the individual teacher, a group of teachers working cooperatively within one school, or a teacher or teachers working alongside a researcher or researchers in a sustained relationship, possibly with other interested parties like advisers, university departments and sponsors on the periphery (Holly and Whitehead, 1986). Action research can be used in a variety of areas, for example:

teaching methods – replacing a traditional method by a discovery method;

teaching methods – replacing a traditional method by a discovery method;

learning strategies – adopting an integrated approach to learning in preference to a single-subject style of teaching and learning;

learning strategies – adopting an integrated approach to learning in preference to a single-subject style of teaching and learning;

evaluative procedures – improving one’s methods of continuous assessment;

evaluative procedures – improving one’s methods of continuous assessment;

attitudes and values – encouraging more positive attitudes to work, or modifying pupils’ value systems with regard to some aspect of life;

attitudes and values – encouraging more positive attitudes to work, or modifying pupils’ value systems with regard to some aspect of life;

continuing professional development of teachers -improving teaching skills, developing new methods of learning, increasing powers of analysis, of heightening self-awareness;

continuing professional development of teachers -improving teaching skills, developing new methods of learning, increasing powers of analysis, of heightening self-awareness;

management and control – the gradual introduction of the techniques of behaviour modification;

management and control – the gradual introduction of the techniques of behaviour modification;

administration – increasing the efficiency of some aspect of the administrative side of school life.

administration – increasing the efficiency of some aspect of the administrative side of school life.

These examples do not mean, however, that action research can be typified straightforwardly; that is to distort its complex and multifaceted nature. Indeed Kemmis (1997) suggests that there are several schools of action research. That said, what unites different conceptions of action research is the desire for improvement to practice, based on a rigorous evidential trail of data and research.

Ferrance (2000: 1) argues that a powerful justification for action research is that teachers:

work best on problems that they have identified for themselves;

work best on problems that they have identified for themselves;

become more effective when they are encouraged to examine and assess their own work and then consider ways of working differently;

become more effective when they are encouraged to examine and assess their own work and then consider ways of working differently;

help each other by working collaboratively;

help each other by working collaboratively;

can help each other in their professional development by working together.

can help each other in their professional development by working together.

She suggests that action research builds on, and builds in, these principles. Indeed action research is a powerful form of participatory research, as discussed in Chapter 2 (see also Kapoor and Jordan, 2009). ‘Commitment’ is a feature of participatory research (see Chapter 2), and participatory action research both requires and builds commitment (David, 2002). Participatory research breaks the separation of the researcher and the participants; power is equalized and, indeed, they may all be part of the same community (ibid). The research becomes a collective and shared enterprise, in many spheres, including: the research interests, agendas and problems; the generation and analysis of data; the equalization of power and control over the research outcomes, products and uses; the development of participant voice, authorship and ownership; a process-oriented and problem-solving approach; emancipatory agendas and political goals; and ethical responsibility and behaviour. We refer the reader to Chapter 2 for a fuller discussion of this.

The different conceptions of action research can be revealed in some typical definitions of action research, for example Hopkins (1985: 32) suggests that the combination of action and research renders that action a form of disciplined, rigorous enquiry, in which a personal attempt is made to understand, improve and reform practice. Ebbutt (1985: 156), too, regards action research as a systematic study that combines action and reflection with the intention of improving practice. Cohen and Manion (1994: 186) define it as ‘a small-scale intervention in the functioning of the real world and a close examination of the effects of such an intervention’. The rigour of action research is attested by another of its founding fathers, Corey (1953: 6), who argues that it is a process in which practitioners study problems scientifically (our italics) so that they can evaluate, improve and steer decision making and practice. Indeed Kemmis and McTaggart (1992: 10) argue that ‘to do action research is to plan, act, observe and reflect more carefully, more systematically, and more rigorously than one usually does in everyday life’.

A more philosophical stance on action research, that echoes the work of Habermas, is taken by Carr and Kemmis (1986: 162), who regard it as a form of ‘self-reflective enquiry’ by participants, which is undertaken in order to improve their understanding of their practices in context with a view to maximizing social justice. McNiff (2002: 17) suggests that action researchers support the view that people can ‘create their own identities’ and that they should allow others to do the same. Grundy (1987: 142) regards action research as concerned with improving the ‘social conditions of existence’. Kemmis and McTaggart (1992) suggest that:

Action research is concerned equally with changing individuals, on the one hand, and, on the other, the culture of the groups, institutions and societies to which they belong. The culture of a group can be defined in terms of the characteristic substance and forms of the language and discourses, activities and practices, and social relationships and organization which constitute the interactions of the group.

(Kemmis and McTaggart, 1992: 16)

Action research is designed to bridge the gap between research and practice (Somekh, 1995: 340), thereby striving to overcome the perceived persistent failure of research to impact on, or improve, practice (see also Rapoport, 1970: 499 and McCormick and James, 1988: 339). Stenhouse (1979) suggests that action research should contribute not only to practice but to a theory of education and teaching which is accessible to other teachers, making educational practice more reflective (Elliott, 1991:54).

Action research combines diagnosis, action and reflection (McNiff 2002: 15), focusing on practical issues that have been identified by participants and which are somehow both problematic yet capable of being changed (Elliott, 1978: 355–6). McNiff (2002: 6) places self-reflection at the heart of action research, suggesting that whereas in some forms of research the researcher ‘does research on other people’, in action research the researcher does it to herself/himself Zuber-Skerritt (1996b: 83) suggests that ‘the aims of any action research project or program are to bring about practical improvement, innovation, change or development of social practice, and the practitioners’ better understanding of their practices’.

The several strands of action research are drawn together by Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) in their all-encompassing definition:

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of the own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of these practices and the situations in which these practices are carried out.... The approach is only action research when it is collaborative, though it is important to realize that the action research of the group is achieved through the critically examined action of individual group members.

(Kemmis and McTaggart, 1988: 5)

Kemmis and McTaggart (1992: 21–2) distinguish action research from the everyday actions of teachers:

It is not the usual thinking teachers do when they think about their teaching. Action research is more systematic and collaborative in collecting evidence on which to base rigorous group reflection.

It is not the usual thinking teachers do when they think about their teaching. Action research is more systematic and collaborative in collecting evidence on which to base rigorous group reflection.

It is not simply problem-solving. Action research involves problem-posing, not just problem-solving. It does not start from a view of ‘problems’ as pathologies. It is motivated by a quest to improve and understand the world by changing it and learning how to improve it from the effects of the changes made.

It is not simply problem-solving. Action research involves problem-posing, not just problem-solving. It does not start from a view of ‘problems’ as pathologies. It is motivated by a quest to improve and understand the world by changing it and learning how to improve it from the effects of the changes made.

It is not research done on other people. Action research is research by particular people on their own work, to help them improve what they do, including how they work with and for others.

It is not research done on other people. Action research is research by particular people on their own work, to help them improve what they do, including how they work with and for others.

Action research is not ‘the scientific method’ applied to teaching. There is not just one view of ‘the scientific method’; there are many.

Action research is not ‘the scientific method’ applied to teaching. There is not just one view of ‘the scientific method’; there are many.

Noffke and Zeichner (1987) make several claims for action research with teachers, namely that it:

brings about changes in their definitions of their professional skills and roles;

brings about changes in their definitions of their professional skills and roles;

increases their feelings of self-worth and confidence;

increases their feelings of self-worth and confidence;

increases their awareness of classroom issues;

increases their awareness of classroom issues;

improves their dispositions toward reflection;

improves their dispositions toward reflection;

changes their values and beliefs;

changes their values and beliefs;

improves the congruence between practical theories and practices;

improves the congruence between practical theories and practices;

broadens their views on teaching, schooling and society.

broadens their views on teaching, schooling and society.

A significant feature here is that action research lays claim to the professional development of teachers; action research for professional development is a frequently heard maxim (e.g. Nixon, 1981; Oja and Smulyan, 1989; Somekh, 1995: 343; Winter, 1996). It is ‘situated learning’; learning in the workplace and about the workplace (Collins and Duguid, 1989). The claims for action research, then, are several. Arising from these claims and definitions are several principles.

Hult and Lennung (1980: 241–50) and McKernan (1991: 32–3) suggest that action research:

makes for practical problem-solving as well as expanding scientific knowledge;

makes for practical problem-solving as well as expanding scientific knowledge;

enhances the competencies of participants;

enhances the competencies of participants;

is collaborative;

is collaborative;

is undertaken directly in situ;

is undertaken directly in situ;

uses feedback from data in an ongoing cyclical process;

uses feedback from data in an ongoing cyclical process;

seeks to understand particular complex social situations;

seeks to understand particular complex social situations;

seeks to understand the processes of change within social systems;

seeks to understand the processes of change within social systems;

is undertaken within an agreed framework of ethics;

is undertaken within an agreed framework of ethics;

seeks to improve the quality of human actions;

seeks to improve the quality of human actions;

focuses on those problems that are of immediate concern to practitioners;

focuses on those problems that are of immediate concern to practitioners;

is participatory;

is participatory;

frequently uses case study;

frequently uses case study;

tends to avoid the paradigm of research that isolates and controls variables;

tends to avoid the paradigm of research that isolates and controls variables;

is formative, such that the definition of the problem, the aims and methodology may alter during the process of action research;

is formative, such that the definition of the problem, the aims and methodology may alter during the process of action research;

includes evaluation and reflection;

includes evaluation and reflection;

is methodologically eclectic;

is methodologically eclectic;

contributes to a science of education;

contributes to a science of education;

strives to render the research usable and shareable by participants;

strives to render the research usable and shareable by participants;

is dialogical and celebrates discourse;

is dialogical and celebrates discourse;

has a critical purpose in some forms;

has a critical purpose in some forms;

strives to be emancipatory.

strives to be emancipatory.

Zuber-Skerritt (1996b: 85) suggests that action research is:

critical (and self-critical) collaborative enquiry by reflective practitioners being accountable and making results of their enquiry public self-evaluating their practice and engaged in participatory problem-solving and continuing professional development.

This latter view is echoed in Winter’s (1996: 13–14) six key principles of action research:

reflexive critique, which is the process of becoming aware of our own perceptual biases;

reflexive critique, which is the process of becoming aware of our own perceptual biases;

dialectical critique, which is a way of understanding the relationships between the elements that make up various phenomena in our context;

dialectical critique, which is a way of understanding the relationships between the elements that make up various phenomena in our context;

collaboration, which is intended to mean that everyone’s view is taken as a contribution to understanding the situation;

collaboration, which is intended to mean that everyone’s view is taken as a contribution to understanding the situation;

risking disturbance, which is an understanding of our own taken-for-granted processes and willingness to submit them to critique;

risking disturbance, which is an understanding of our own taken-for-granted processes and willingness to submit them to critique;

creating plural structures, which involves developing various accounts and critiques, rather than a single authoritative interpretation;

creating plural structures, which involves developing various accounts and critiques, rather than a single authoritative interpretation;

theory and practice internalized, which is seeing theory and practice as two interdependent yet complementary phases of the change process.

theory and practice internalized, which is seeing theory and practice as two interdependent yet complementary phases of the change process.

The several features that the definitions at the start of this chapter have in common suggest that action research has key principles. These are summarized by Kemmis and McTaggart (1992: 22–5):

Action research is an approach to improving education by changing it and learning from the consequences of changes.

Action research is an approach to improving education by changing it and learning from the consequences of changes.

Action research is participatory: it is research through which people work towards the improvement of their own practices (and only secondarily on other people’s practices).

Action research is participatory: it is research through which people work towards the improvement of their own practices (and only secondarily on other people’s practices).

Action research develops through the self-reflective spiral: a spiral of cycles of planning, acting (implementing plans), observing (systematically), reflecting ... and then re-planning, further implementation, observing and reflecting.

Action research develops through the self-reflective spiral: a spiral of cycles of planning, acting (implementing plans), observing (systematically), reflecting ... and then re-planning, further implementation, observing and reflecting.

Action research is collaborative: it involves those responsible for action in improving it.

Action research is collaborative: it involves those responsible for action in improving it.

Action research establishes self-critical communities of people participating and collaborating in all phases of the research process: the planning, the action, the observation and the reflection; it aims to build communities of people committed to enlightening themselves about the relationship between circumstance, action and consequence in their own situation, and emancipating themselves from the institutional and personal constraints which limit their power to live their own legitimate educational and social values.

Action research establishes self-critical communities of people participating and collaborating in all phases of the research process: the planning, the action, the observation and the reflection; it aims to build communities of people committed to enlightening themselves about the relationship between circumstance, action and consequence in their own situation, and emancipating themselves from the institutional and personal constraints which limit their power to live their own legitimate educational and social values.

Action research is a systematic learning process in which people act deliberately, though remaining open to surprises and responsive to opportunities.

Action research is a systematic learning process in which people act deliberately, though remaining open to surprises and responsive to opportunities.

Action research involves people in theorizing about their practices – being inquisitive about circumstances, action and consequences and coming to understand the relationships between circumstances, actions and consequences in their own lives.

Action research involves people in theorizing about their practices – being inquisitive about circumstances, action and consequences and coming to understand the relationships between circumstances, actions and consequences in their own lives.

Action research requires that people put their practices, ideas and assumptions about institutions to the test by gathering compelling evidence which could convince them that their previous practices, ideas and assumptions were wrong or wrong-headed.

Action research requires that people put their practices, ideas and assumptions about institutions to the test by gathering compelling evidence which could convince them that their previous practices, ideas and assumptions were wrong or wrong-headed.

Action research is open-minded about what counts as evidence (or data) – it involves not only keeping records which describe what is happening as accurately as possible ... but also collecting and analysing our own judgements, reactions and impressions about what is going on.

Action research is open-minded about what counts as evidence (or data) – it involves not only keeping records which describe what is happening as accurately as possible ... but also collecting and analysing our own judgements, reactions and impressions about what is going on.

Action research involves keeping a personal journal in which we record our progress and our reflections about two parallel sets of learning: our learnings about the practices we are studying ... and our learnings about the process (the practice) of studying them.

Action research involves keeping a personal journal in which we record our progress and our reflections about two parallel sets of learning: our learnings about the practices we are studying ... and our learnings about the process (the practice) of studying them.

Action research is a political process because it involves us in making changes that will affect others.

Action research is a political process because it involves us in making changes that will affect others.

Action research involves people in making critical analyses of the situations (classrooms, schools, systems) in which they work: these situations are structured institutionally.

Action research involves people in making critical analyses of the situations (classrooms, schools, systems) in which they work: these situations are structured institutionally.

Action research starts small, by working through changes which even a single person (myself) can try, and works towards extensive changes – even critiques of ideas or institutions which in turn might lead to more general reforms of classroom, school or system-wide policies and practices.

Action research starts small, by working through changes which even a single person (myself) can try, and works towards extensive changes – even critiques of ideas or institutions which in turn might lead to more general reforms of classroom, school or system-wide policies and practices.

Action research starts with small cycles of planning, acting, observing and reflecting which can help to define issues, ideas and assumptions more clearly so that those involved can define more power questions for themselves as their work progresses.

Action research starts with small cycles of planning, acting, observing and reflecting which can help to define issues, ideas and assumptions more clearly so that those involved can define more power questions for themselves as their work progresses.

Action research starts with small groups of collaborators, but widens the community of participating action researchers so that it gradually includes more and more of those involved and affected by the practices in question.

Action research starts with small groups of collaborators, but widens the community of participating action researchers so that it gradually includes more and more of those involved and affected by the practices in question.

Action research allows us to build records of our improvements: (a) records of our changing activities and practices, (b) records of the changes in the language and discourse in which we describe, explain and justify our practices, (c) records of the changes in the social relationships and forms of organization which characterize and constrain our practices, and (d) records of the development in mastery of action research.

Action research allows us to build records of our improvements: (a) records of our changing activities and practices, (b) records of the changes in the language and discourse in which we describe, explain and justify our practices, (c) records of the changes in the social relationships and forms of organization which characterize and constrain our practices, and (d) records of the development in mastery of action research.

Action research allows us to give a reasoned justification of our educational work to others because we can show how the evidence we have gathered and the critical reflection we have done have helped us to create a developed, tested and critically examined rationale for what we are doing.

Action research allows us to give a reasoned justification of our educational work to others because we can show how the evidence we have gathered and the critical reflection we have done have helped us to create a developed, tested and critically examined rationale for what we are doing.

Though these principles find widespread support in the literature on action research, they require some comment. For example, there is a strong emphasis in these principles on action research as a cooperative, collaborative activity (e.g. Hill and Kerber, 1967). Kemmis and McTaggart (1992) locate this in the work of Lewin himself, commenting on his commitment to group decision making (p. 6). They argue, for example, that ‘those affected by planned changes have the primary responsibility for deciding on courses of critically informed action which seem likely to lead to improvement, and for evaluating the results of strategies tried out in practice ... action research is a group activity [and] action research is not individualistic’. To Tapse into individualism is to destroy the critical dynamic of the group’ (p. 15) (italics in original).

The view of action research solely as a group activity, however, might be too restricting. It is possible for action research to be an individualistic matter as well, relating action research to the ‘teacher-as-researcher’ movement (Stenhouse, 1975). Whitehead (1985: 98) explicitly writes about action research in individualistic terms, and we can take this to suggest that a teacher can ask herself or himself: ‘what do I see as my problem?’ ‘What do I see as a possible solution?’ ‘How can I direct the solution?’ ‘How can I evaluate the outcomes and take subsequent action?’

The adherence to action research as a group activity derives from several sources. Pragmatically, Oja and Smulyan (1989: 14), in arguing for collaborative action research, suggest that teachers are more likely to change their behaviours and attitudes if they have been involved in the research that demonstrates not only the need for such change but that it can be done – the issue of ‘ownership’ and ‘involvement’ that finds its parallel in management literature that suggests that those closest to the problem are in the best position to identify it and work towards its solution (e.g. Morrison, 1998).

Ideologically, there is a view that those experiencing the issue should be involved in decision making, itself hardly surprising given Lewin’s own work with disadvantaged and marginalized groups, i.e. those groups with little voice (cf David, 2002).

Politics and ideology are brought together in action research in participatory action research and action research as critical praxis, and it is to this that we turn.

Participatory action research has attracted attention across the world, in its advocacy of empowerment and emancipation. McTaggart (1989) suggests 16 tenets of participatory action research, indicating that it:

seeks to improve social practice by changing it;

seeks to improve social practice by changing it;

requires authentic participation;

requires authentic participation;

is collaborative;

is collaborative;

establishes self-critical communities;

establishes self-critical communities;

is a systematic process of learning;

is a systematic process of learning;

involves people in theorizing about their own practices and values;

involves people in theorizing about their own practices and values;

requires people to test their own assumptions, values, ideas and practices in real-life practice;

requires people to test their own assumptions, values, ideas and practices in real-life practice;

requires records to be kept;

requires records to be kept;

requires participants to look at their own experiences objectively;

requires participants to look at their own experiences objectively;

is part of a political process (e.g. towards democracy);

is part of a political process (e.g. towards democracy);

involves people in making critical analyses of a situation, research and practice;

involves people in making critical analyses of a situation, research and practice;

starts small;

starts small;

starts in small cycles;

starts in small cycles;

starts with small groups of people;

starts with small groups of people;

requires and allows participants to build evidential records of practice, theory and reflection;

requires and allows participants to build evidential records of practice, theory and reflection;

requires and allows participants to provide a reasoned justification to others for their work.

requires and allows participants to provide a reasoned justification to others for their work.

That there is a coupling of the ideological and political debate here has been brought into focus with the work of Freire (1972) and Torres (1992: 56) in Latin America, the latter setting out several principles of participatory action research:

it commences with explicit social and political intentions that articulate with the dominated and poor classes and groups in society;

it commences with explicit social and political intentions that articulate with the dominated and poor classes and groups in society;

it must involve popular participation in the research process, i.e. it must have a social basis;

it must involve popular participation in the research process, i.e. it must have a social basis;

it regards knowledge as an agent of social transformation as a whole, thereby constituting a powerful critique of those views of knowledge (theory) as somehow separate from practice;

it regards knowledge as an agent of social transformation as a whole, thereby constituting a powerful critique of those views of knowledge (theory) as somehow separate from practice;

its epistemological base is rooted in critical theory and its critique of the subject/object relations in research;

its epistemological base is rooted in critical theory and its critique of the subject/object relations in research;

it must raise the consciousness of individuals, groups and nations.

it must raise the consciousness of individuals, groups and nations.

Participatory action research does not mean that all participants need be doing the same. This recognizes a role for the researcher as facilitator, guide, formulator and summarizer of knowledge, raiser of issues (e.g. the possible consequences of actions, the awareness of structural conditions) (Weiskopf and Laske, 1996: 132–3).

Participatory action research is distinguished not only by its methodology (collective participation) and its outcomes (democracy, voice, emancipation) but by its areas of focus (inequalities of power, grassroots agendas for change and development, e.g. educational inequality, social exclusion, sexism and racism in education, powerlessness in decision making, student disaffection with a socially reproductive curriculum, elitism in education (cf. Wadsworth, 1998; Fine, 2010; INCITE, 2010)). Importantly here, the agendas and areas of focus are identified by the participants themselves, so they are rooted in reality, are authentic, and are ‘owned’ by the participants and communities themselves.

What is being argued here is that participatory action research – people acting and researching on, by, with and for themselves – is a democratic activity (Grundy, 1987: 142). This form of democracy is participatory (rather than, for example, representative), a key feature of critical theory (discussed below, see also Aronowitz and Giroux, 1986; Giroux, 1989). It is not merely a form of change theory, but addresses fundamental issues of power and power relationships, for, in according power to participants, action research is seen as an empowering activity (David, 2002). Elliott (1991: 54) argues that such empowerment has to be at a collective rather than individual level as individuals do not operate is isolation from each other, but they are shaped by organizational and structural forces.

The issue is important, for it begins to separate action research into different camps (Kemmis, 1997: 177). On the one hand are long-time advocates of action research such as Elliott (e.g. 1978, 1991) who are in the tradition of Schwab and Schön and who emphasize reflective practice; this is a particularly powerful field of curriculum research with notions of the ‘teacher-as-researcher’ (Stenhouse, 1975) and the reflective practitioner (Schoö, 1983, 1987). On the other are advocates in the ‘critical’ action research model, e.g. Carr and Kemmis (1986).

Much of the writing in this field of action research draws on the Frankfurt School of critical theory (discussed in Chapter 2), in particular the work of Haber-mas. Indeed Weiskopf and Laske (1996: 123) locate action research, in the German tradition, squarely as a ‘critical social science’. Using Habermas’s early writing on knowledge-constitutive interests (1972, 1974) a threefold typology of action research can be constructed; the classification was set out in Chapter 2.

Grundy (1987: 154) argues that ‘technical’ action research is designed to render an existing situation more efficient and effective. In this respect it is akin to Argyris’s (1990) notion of ‘single-loop learning’, being functional, often short term and technical. It is akin to Schön’s (1987) notion of ‘reflection-in-action’ (Morrison, 1995a). Elliott (1991: 55) suggests that this view is limiting for action research since it is too individualistic and neglects wider curriculum structures, regarding teachers in isolation from wider factors.

By contrast, ‘practical’ action research is designed to promote teachers’ professionalism by drawing on their informed judgement (Grundy, 1987: 154). This underpins the ‘teacher-as-researcher’ movement, inspired by Stenhouse. It is akin to Schon’s ‘reflection-on-action’ and is a hermeneutic activity of understanding and interpreting social situations with a view to their improvement. Echoing this, Kincheloe (2003: 42) suggests that action research rejects positivistic views of rationality, objectivity, truth and methodology, preferring hermeneutic understanding and emancipatory practice. As he says (p. 108) the teacher-as-researcher movement is a political enterprise rather than the accretion of trivial cookbook remedies – a technical exercise.

Emancipatory action research has an explicit agenda which is as political as it is educational. Grundy (1987) provides a useful introduction to this view. She argues (pp. 146–7) that emancipatory action research seeks to develop in participants their understandings of illegitimate structural and interpersonal constraints that are preventing the exercise of their autonomy and freedom. These constraints, she argues, are based on illegitimate repression, domination and control. When participants develop a consciousness of these constraints, she suggests, they begin to move from unfreedom and constraint to freedom, autonomy and social justice.

Kincheloe (2003: 138–9) suggests a seven-step process of emancipatory action research:

Constructing a system of meaning.

Constructing a system of meaning.

Understanding dominant research methods and their effects.

Understanding dominant research methods and their effects.

Selecting what to study.

Selecting what to study.

Acquiring a variety of research strategies.

Acquiring a variety of research strategies.

Making sense of information collected.

Making sense of information collected.

Gaining awareness of the tacit theories and assumptions which guide practice.

Gaining awareness of the tacit theories and assumptions which guide practice.

Viewing teaching as an emancipatory, praxis-based act.

Viewing teaching as an emancipatory, praxis-based act.

‘Praxis’ here is defined as action informed through reflection, and with emancipation as its goal.

Action research, then, empowers individuals and social groups to take control over their lives within a framework of the promotion, rather than the suppression of, generalizable interests (Habermas, 1976). It commences with a challenge to the illegitimate operation of power, hence in some respects (albeit more politicized because it embraces the dimension of power) it is akin to Argyris’s (1990) notion of ‘double-loop learning’ in that it requires participants to question and challenge given value systems. For Grundy, praxis fuses theory and practice within an egalitarian social order, and action research is designed with the political agenda of improvement towards a more just, egalitarian society. This accords to some extent with Lewin’s view that action research leads to equality and cooperation, an end to exploitation and the furtherance of democracy (see also Hopkins, 1985: 32; Carr and Kemmis, 1986: 163). Zuber-Skerritt suggests that:

emancipatory action research ... is collaborative, critical and self-critical inquiry by practitioners ... into a major problem or issue or concern in their own practice. They own the problem and feel responsible and accountable for solving it through teamwork and through following a cyclical process of:

1 strategic planning;

2 action, i.e. implementing the plan;

3 observation, evaluation and self-evaluation;

4 critical and self-critical reflection on the results of points 1–3 and making decisions for the next cycle of action research.

(Zuber-Skerritt, 1996a: 3)

Action research, she argues,

is emancipatory when it aims not only at technical and practical improvement and the participants’ better understanding, along with transformation and change within the existing boundaries and conditions, but also at changing the system itself or those conditions which impede desired improvement in the system/organization.....There is no hierarchy, but open and ‘symmetrical communication’.

(Zuber-Skerritt, 1996a: 5)

The emancipatory interest takes very seriously the notion of action researchers as participants in a community of equals. This, in turn is premised on the later work of Habermas in his notion of the ‘ideal speech situation’. Here:

action research is construed as reflective practice with a political agenda;

action research is construed as reflective practice with a political agenda;

all participants (and action research is participatory) are equal ‘players’;

all participants (and action research is participatory) are equal ‘players’;

action research is necessarily dialogical – interpersonal – rather than monological (individual); and

action research is necessarily dialogical – interpersonal – rather than monological (individual); and

communication is an intrinsic element, with communication being amongst the community of equals (Grundy and Kemmis, 1988: 87, term this ‘symmetrical communication’);

communication is an intrinsic element, with communication being amongst the community of equals (Grundy and Kemmis, 1988: 87, term this ‘symmetrical communication’);

because it is a community of equals, action research is necessarily democratic and promotes democracy;

because it is a community of equals, action research is necessarily democratic and promotes democracy;

the search is for consensus (and consensus requires more than one participant), hence it requires collaboration and participation.

the search is for consensus (and consensus requires more than one participant), hence it requires collaboration and participation.

In this sense emancipatory action research fulfils the requirements of action research set out by Kemmis and McTaggart above; indeed it could be argued that only emancipatory action research (in the threefold typology) has the potential to do this.

Kemmis (1997: 177) suggests that the distinction between the two camps (the reflective practitioners and the critical theorists) lies in their interpretation of action research. For the former, action research is an improvement to professional practice at the local, perhaps classroom level, within the capacities of individuals and the situations in which they are working; for the latter, action research is part of a broader agenda of changing education, changing schooling and changing society.

A key term in action research is ‘empowerment’; for the former camp, empowerment is largely a matter of the professional sphere of operations, achieving professional autonomy through professional development. For the latter, empowerment concerns taking control over one’s life within a just, egalitarian, democratic society. Whether the latter is realizable or utopian is a matter of critique of this view. Where is the evidence that critical action research either empowers groups or alters the macro-structures of society? Is critical action research socially transformative? At best the jury is out; at worst the jury simply has gone away as capitalism overrides egalitarianism worldwide. The point at issue here is the extent to which the notion of emancipatory action research has attempted to hijack the action research agenda, and whether, in so doing (if it has), it has wrested action research away from practitioners and into the hands of theorists and the academic research community only.

More specifically, several criticisms have been levelled at this interpretation of emancipatory action research (Gibson, 1985; Morrison, 1995a, 1995b; Somekh, 1995; Melrose, 1996; Grundy, 1996; Weiskopf and Laske, 1996; Webb, 1996; McTaggart, 1996; Kemmis, 1997), including the views that:

it is utopian and unrealizable;

it is utopian and unrealizable;

it is too controlling and prescriptive, seeking to capture and contain action research within a particular mould – it moves towards conformity;

it is too controlling and prescriptive, seeking to capture and contain action research within a particular mould – it moves towards conformity;

it adopts a narrow and particularistic view of emancipation and action research, and how to undertake the latter;

it adopts a narrow and particularistic view of emancipation and action research, and how to undertake the latter;

it undermines the significance of the individual teacher-as-researcher in favour of self-critical communities. (Kemmis and McTaggart (1992: 152) pose the question ‘why must action research consist of a group process?’);

it undermines the significance of the individual teacher-as-researcher in favour of self-critical communities. (Kemmis and McTaggart (1992: 152) pose the question ‘why must action research consist of a group process?’);

the threefold typification of action research is untenable;

the threefold typification of action research is untenable;

it assumes that rational consensus is achievable, that rational debate will empower all participants (i.e. it understates the issue of power, wherein the most informed are already the most powerful – Grundy (1996: 111) argues that the better argument derives from the one with the most evidence and reasons, and that these are more available to the powerful, thereby rendering the conditions of equality suspect);

it assumes that rational consensus is achievable, that rational debate will empower all participants (i.e. it understates the issue of power, wherein the most informed are already the most powerful – Grundy (1996: 111) argues that the better argument derives from the one with the most evidence and reasons, and that these are more available to the powerful, thereby rendering the conditions of equality suspect);

it overstates the desirability of consensus-oriented research (which neglects the complexity of power);

it overstates the desirability of consensus-oriented research (which neglects the complexity of power);

power cannot be dispersed or rearranged simply by rationality;

power cannot be dispersed or rearranged simply by rationality;

action research as critical theory reduces its practical impact and confines it to the commodification of knowledge in the academy;

action research as critical theory reduces its practical impact and confines it to the commodification of knowledge in the academy;

it is uncritical and self-contradicting;

it is uncritical and self-contradicting;

will promote conformity through slavish adherence to its orthodoxies;

will promote conformity through slavish adherence to its orthodoxies;

is naive in its understanding of groups and celebrates groups over individuals, particularly the ‘in-groups’ rather than the ‘out-groups’;

is naive in its understanding of groups and celebrates groups over individuals, particularly the ‘in-groups’ rather than the ‘out-groups’;

privileges its own view of science (rejecting objectivity) and lacks modesty;

privileges its own view of science (rejecting objectivity) and lacks modesty;

privileges the authority of critical theory;

privileges the authority of critical theory;

is elitist whilst purporting to serve egalitarianism;

is elitist whilst purporting to serve egalitarianism;

assumes an undifferentiated view of action research;

assumes an undifferentiated view of action research;

is attempting to colonize and redirect action research.

is attempting to colonize and redirect action research.

This seemingly devastating critique serves to remind the reader that critical action research, even though it has caught the high ground of recent coverage, is highly problematical. It is just as controlling as those controlling agendas that it seeks to attack (Morrison, 1995b). Indeed Melrose (1996: 52) suggests that, because critical research is, itself, value-laden, it abandons neutrality; it has an explicit social agenda that, under the guise of examining values, ethics, morals and politics that are operating in a particular situation, is actually aimed at transforming the status quo.

For a simple introductory exercise for understanding action research see the accompanying website.

Not only does action research link with participatory research, but affinities have been drawn between action research and complexity theory. Phelps and Graham (2010: 184) argue that action research ‘can readily accommodate the key tenets of complexity theory’ and that there is a ‘deep complementarity’ between them. For example they note (p. 187) that action research:

accepts that systems are unpredictable, open and non-linear;

accepts that systems are unpredictable, open and non-linear;

resonates with issues of adaptation to environment;

resonates with issues of adaptation to environment;

can lead to bifurcation (see Chapter 1) (i.e. when a system moves from one ‘point of stability to another’ (p. 190));

can lead to bifurcation (see Chapter 1) (i.e. when a system moves from one ‘point of stability to another’ (p. 190));

celebrates the interaction of participants;

celebrates the interaction of participants;

requires both feedback and feed forward;

requires both feedback and feed forward;

is reflective;

is reflective;

shows an interests in ‘exceptions’ or outliers (which can lead to major change (p. 194));

shows an interests in ‘exceptions’ or outliers (which can lead to major change (p. 194));

is not concerned with controlling variables;

is not concerned with controlling variables;

accepts that the systems in which it takes place are complex and dynamic.

accepts that the systems in which it takes place are complex and dynamic.

This is reinforced by Davis and Sumara (2005: 455) in their comments that ‘coherent collective behaviours and characters emerge in the activities and interactivities of individual agents’, not least in the context of self-organization. Phelps and Graham (2010: 195) are concerned to show that action research, like complexity theory, has some aversion to positivism.

There are several ways in which the steps of action research have been analysed. Blum (National Education Association of the United States, 1959) casts action research into two simple stages: a diagnostic stage in which the problems are analysed and the hypotheses developed; and a therapeutic stage in which the hypotheses are tested by a consciously directed intervention or experiment in situ. Lewin (1946, 1948) codified the action research process into four main stages: planning, acting, observing and reflecting.

He suggests that action research commences with a general idea and data are sought about the presenting situation. The successful outcome of this examination is the production of a plan of action to reach an identified objective, together with a decision on the first steps to be taken. Lewin acknowledges that this might involve modifying the original plan or idea. The next stage of implementation is accompanied by ongoing fact-finding to monitor and evaluate the intervention, i.e. to act as a formative evaluation. This feeds forward into a revised plan and set of procedures for implementation, themselves accompanied by monitoring and evaluation. Lewin (1948: 205) suggests that such ‘rational social management’ can be conceived of as a spiral of planning, action and fact-finding about the outcomes of the actions taken.

The legacy of Lewin’s work, though contested (e.g. McTaggart, 1996: 248) is powerful in the steps of action research set out by Kemmis and McTaggart:

In practice, the process begins with a general idea that some kind of improvement or change is desirable. In deciding just where to begin in making improvements, one decides on a field of action ... where the battle (not the whole war) should be fought. It is a decision on where it is possible to have an impact. The general idea prompts a ‘reconnaissance’’ of the circumstances of the field, and fact-finding about them. Having decided on the field and made a preliminary reconnaissance, the action researcher decides on a general plan of action. Breaking the general plan down into achievable steps, the action researcher settles on the first action step. Before taking this first step the action researcher becomes more circumspect, and devises a way of monitoring the effects of the first action step. When it is possible to maintain fact-finding by monitoring the action, the first step is taken. As the step is implemented, new data start coming in and the effect of the action can be described and evaluated. The general plan is then revised in the light of the new information about the field of action and the second action step can be planned along with appropriate monitoring procedures. The second step is then implemented, monitored and evaluated; and the spiral of action, monitoring, evaluation and replanning continues.

(Kemmis and McTaggart, 1981: 2)

McKernan (1991: 17) suggests that Lewin’s model of action research is a series of spirals, each of which incorporates a cycle of analysis, reconnaissance, reconceptualization of the problem, planning of the intervention, implementation of the plan, evaluation of the effectiveness of the intervention. Ebbutt (1985) adds to this the view that feedback within and between each cycle is important, facilitating reflection. This is reinforced in the model of action research by Altricher and Gstettner (1993) where, though they have four steps (p. 343): (a) finding a starting point; (b) clarifying the situation;, (c) developing action strategies and putting them into practice; (d) making teachers’ knowledge public -they suggest that steps (b) and (c) need not be sequential, thereby avoiding the artificial divide that might exist between data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Zuber-Skerritt (1996b: 84) sets emancipatory (critical) action research into a cyclical process of: ‘(1) strategic planning, (2) implementing the plan (action), (3) observation, evaluation and self-evaluation, (4) critical and self-critical reflection on the results of (1) – (3) and making decisions for the next cycle of research.’ In an imaginative application of action research to organizational change theory she takes the famous work of Lewin (1952) on forcefield analysis and change theory (unfreezing → moving → refreezing) and the work of Beer et al. (1990) on task alignment, and sets them into an action research sequence that clarifies the steps of action research very usefully (Figure 18.1).

Bassey (1998) sets out eight stages in action research:

Stage 1: Defining the enquiry.

Stage 2: Describing the educational context and situation.

Stage 3: Collecting evaluative data and analysing them.

Stage 4: Reviewing the data and looking for contradictions.

Stage 5: Tackling a contradiction by introducing change.

Stage 6: Monitoring the change.

Stage 7: Analysing evaluative data about the change.

Stage 8: Reviewing the change and deciding what to do next.

McNiff (2002: 71), too, sets out an eight-stage model of the action research process:

review your current practice;

review your current practice;

identify an aspect that you wish to improve;

identify an aspect that you wish to improve;

imagine a way forward in this;

imagine a way forward in this;

try it out;

try it out;

monitor and reflect on what happens;

monitor and reflect on what happens;

modify the plan in the light of what has been found, what has happened, and continue;

modify the plan in the light of what has been found, what has happened, and continue;

evaluate the modified action;

evaluate the modified action;

continue until you are satisfied with that aspect of your work (e.g. repeat the cycle).

continue until you are satisfied with that aspect of your work (e.g. repeat the cycle).

FIGURE 18.1 A model of emancipatory action research for organizational change

Source: Zuber-Skerritt, 1996b: 99

Sagor (2005: 4) sets out a straightforward four-stage model of action research:

Stage 1: Clarify vision and targets.

Stage 2: Articulate appropriate theory.

Stage 3: Implement action and collect data.

Stage 4: Reflect on the data and plan informed action.

Another approach is to set out an eight-stage model:

Stage 1: Decide and agree one common problem that you are experiencing or need that must be addressed.

Stage 2: Identify some causes of the problem (need).

Stage 3: Brainstorm a range of possible practical solutions to the problem, to address the real problem and the real cause(s).

Stage 4: From the range of possible practical solutions decide one of the solutions to the problems, perhaps what you consider to be the most suitable or best solution to the problem. Plan how to put the solution into practice.

Stage 5: Identify some ‘success criteria’ by which you will be able to judge whether the solution has worked to solve the problem, i.e. how will you know whether the proposed solution, when it is put into practice, has been successful. Identify some practical criteria which will tell you how successful the project has been.

Stage 6: Put the plan into action; monitor, adjust and evaluate what is taking place.

Stage 7 Evaluate the outcome to see how well it has addressed and solved the problem or need, using the success criteria identified in Stage 5.

Stage 8: Review and plan what needs to be done in light of the evaluation.

The key features of action research here are:

it works on, and tries to solve, real, practitioner-identified problems of everyday practice;

it works on, and tries to solve, real, practitioner-identified problems of everyday practice;

it is collaborative and builds in teacher involvement;

it is collaborative and builds in teacher involvement;

it seeks causes and tries to work on those causes;

it seeks causes and tries to work on those causes;

the solutions are suggested by the practitioners involved;

the solutions are suggested by the practitioners involved;

it involves a divergent phase and a convergent phase;

it involves a divergent phase and a convergent phase;

it plans an intervention by the practitioners themselves;

it plans an intervention by the practitioners themselves;

it implements the intervention;

it implements the intervention;

it evaluates the success of the intervention in solving the identified problem.

it evaluates the success of the intervention in solving the identified problem.

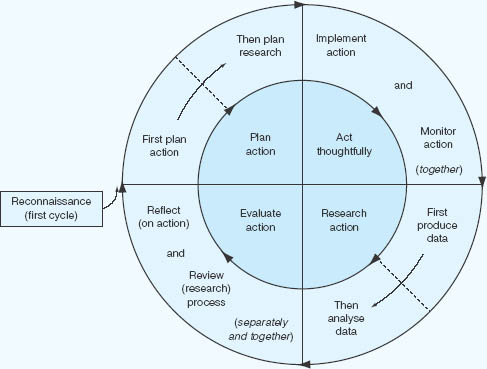

Tripp (2003) sets out a full action research cycle of reconnaissance, planning, acting, researching action, evaluating action, in Figure 18.2.

Put more skeletally, the action research process is set out in Figure 18.3.

We set out below an eight-stage process of action research that attempts to draw together the several strands and steps of the action research undertaking. The first stage will involve the identification, evaluation and formulation of the problem perceived as critical in an everyday teaching situation. ‘Problem’ should be interpreted loosely here so that it could refer to the need to introduce innovation into some aspect of a school’s established programme.

The second stage involves preliminary discussion and negotiations among the interested parties – teachers, researchers, advisers, sponsors, possibly – which may culminate in a draft proposal. This may include a statement of the questions to be answered (e.g. ‘Under what conditions can curriculum change be best effected?’, ‘What are the limiting factors in bringing about effective curriculum change?’, ‘What strong points of action research can be employed to bring about curriculum change?’). The researchers in their capacity as consultants (or sometimes as programme initiators) may draw upon their expertise to bring the problem more into focus, possibly determining causal factors or recommending alternative lines of approach to established ones. This is often the crucial stage for the venture as it is at this point that the seeds of success or failure are planted, for, generally speaking, unless the objectives, purposes and assumptions are made perfectly clear to all concerned, and unless the role of key concepts is stressed (e.g. feedback), the enterprise can easily miscarry.

FIGURE 18.2 The full action research cycle

Source: Tripp, D. 2003. Action Inquiry. Action Research e-Reports 017. http://www2.fhs.usyd.edu.au/arow/arer/017.htm. Reproduced with permission of David Tripp

The third stage may in some circumstances involve a review of the research literature to find out what can be learned from comparable studies, their objectives, procedures and problems encountered.

The fourth stage may involve a modification or redefinition of the initial statement of the problem at stage one. It may now emerge in the form of a testable hypothesis; or as a set of guiding objectives. Sometimes change agents deliberately decide against the use of objectives on the grounds that they have a constraining effect on the process itself. It is also at this stage that assumptions underlying the project are made explicit (e.g. in order to effect curriculum changes, the attitudes, values, skills and objectives of the teachers involved must be changed).

The fifth stage may be concerned with the selection of research procedures – sampling, administration, choice of materials, methods of teaching and learning, allocation of resources and tasks, deployment of staff and so on. Here it must be stated that embedded within the overall scope of the term ‘action research’ might be a number of different research designs that include different methods of gathering data. A piece of action research might include, for example:

an initial and end-of-intervention survey (a pre- and post-survey);

an initial and end-of-intervention survey (a pre- and post-survey);

an experimental or quasi-experimental design (e.g. where some students/teachers are involved in the intervention and some are not, or where pre- and post-testing of students/teachers is undertaken);

an experimental or quasi-experimental design (e.g. where some students/teachers are involved in the intervention and some are not, or where pre- and post-testing of students/teachers is undertaken);

a longitudinal study (over the duration of the intervention);

a longitudinal study (over the duration of the intervention);

participant and non-participant observation;

participant and non-participant observation;

interviews and field notes;

interviews and field notes;

one or more case studies;

one or more case studies;

documentation from, and about, participants;

documentation from, and about, participants;

questionnaire data.

questionnaire data.

In this respect readers are advised to go to the chapters in this book that deal with these methods, in particular on case study, experiments and quasi-experiments, and observation. Many novice researchers are unsure whether their research is action research or a case study; indeed it may be both, but a distinguishing feature may be whether the research involves action/collective action on the part of the researcher(s), or whether the data are largely only collected. If it is the former – concerning change, development and intervention, then it may be action research, whereas if it is largely the latter then it may be more of a case study; one has to be very cautious in making this distinction because there can be gross overlaps between the two.

As action research is intended to bring about a change, with an intervention involved, then the researcher may wish to use an experimental or quasi-experimental approach in the action research in an attempt to identify causality through a controlled intervention, with control and experimental groups (see Chapter 16).

The sixth stage will be concerned with the choice of the evaluation procedures to be used and will need to take into consideration that evaluation in this context will be continuous.

The seventh stage embraces the implementation of the project itself (over varying periods of time). It will include the conditions and methods of data collection (e.g. fortnightly meetings, the keeping of records, interim reports, final reports, the submission of self-evaluation and group-evaluation reports, etc.); the monitoring of tasks and the transmission of feedback to the research team; and the classification and analysis of data.

The eighth and final stage will involve the interpretation of the data; inferences to be drawn; and overall evaluation of the project (see Woods, 1989). Discussions on the findings will take place in the light of previously agreed evaluative criteria. Errors, mistakes and problems will be considered. A general summing-up may follow this in which the outcomes of the project are reviewed, recommendations made and arrangements for dissemination of results to interested parties decided.

As we stressed, this is a basic framework; much activity of an incidental and possibly ad hoc nature will take place in and around it. This may comprise discussions among teachers, researchers and pupils; regular meetings among teachers or schools to discuss progress and problems, and to exchange information; possibly regional conferences; and related activities, all enhanced by the range of current hardware and software.

Hopkins (1985), McNiff (1988), McNiff et al. (1996) and McNiff and Whitehead (2009) offer much practical advice on the conduct of action research, including ‘getting started’, operationalization, planning, monitoring and documenting the intervention, collecting data and making sense of them, using case studies, evaluating the action research, ethical issues and reporting. We urge readers to go to these helpful sources. These are essentially both introductory sources and manuals for practice. McNiff (2002: 85–91) provides useful advice for novice action researchers:

Stay small, stay focused.

Stay small, stay focused.

Identify a clear research question.

Identify a clear research question.

Be realistic about what you can do; be aware that wider change begins with you.

Be realistic about what you can do; be aware that wider change begins with you.

Plan carefully.

Plan carefully.

Set a realistic timescale.

Set a realistic timescale.

Involve others (as participants, observers, validators – including critical friends – potential researchers).

Involve others (as participants, observers, validators – including critical friends – potential researchers).

Ensure good ethical practice.

Ensure good ethical practice.

Concentrate on learning, not on the outcomes of action.

Concentrate on learning, not on the outcomes of action.

The focus of the research is you, in company with others.

The focus of the research is you, in company with others.

Beware of happy endings.

Beware of happy endings.

Be aware of political issues.

Be aware of political issues.

She makes the point (p. 98) that it is important to set evaluative criteria. Without success criteria it is impossible for the researcher to know whether, or how far, the action research has been successful. Action researchers could ask themselves ‘How will we know whether we have been successful?’

Kemmis and McTaggart (1992: 25–7) offer a useful series of observations for beginning action research:

Get an action research group together and participate yourself – be a model learner about action research.

Get an action research group together and participate yourself – be a model learner about action research.

Be content to start to work with a small group.

Be content to start to work with a small group.

Get organized.

Get organized.

Start small.

Start small.

Establish a time line.

Establish a time line.

Arrange for supportive work-in-progress discussions in the action research group.

Arrange for supportive work-in-progress discussions in the action research group.

Be tolerant and supportive – expect people to learn from experience.

Be tolerant and supportive – expect people to learn from experience.

Be persistent about monitoring.

Be persistent about monitoring.

Plan for a long haul on the bigger issues of changing classroom practices and school structures.

Plan for a long haul on the bigger issues of changing classroom practices and school structures.

Work to involve (in the research process) those who are involved (in the action), so that they share responsibility for the whole action research process.

Work to involve (in the research process) those who are involved (in the action), so that they share responsibility for the whole action research process.

Remember that how you think about things – the language and understandings that shape your action – may need changing just as much as the specifics of what you do.

Remember that how you think about things – the language and understandings that shape your action – may need changing just as much as the specifics of what you do.

Register progress not only with the participant group but also with the whole staff and other interested people.

Register progress not only with the participant group but also with the whole staff and other interested people.

If necessary arrange legitimizing rituals – involving consultants or other outsiders.

If necessary arrange legitimizing rituals – involving consultants or other outsiders.

Make time to write throughout your project.

Make time to write throughout your project.

Be explicit about what you have achieved by reporting progress.

Be explicit about what you have achieved by reporting progress.

Throughout, keep in mind the distinction between education and schooling.

Throughout, keep in mind the distinction between education and schooling.

Throughout, ask yourself whether your action research project is helping you (and those with whom you work) to improve the extent to which you are living your educational values [italics in original].

Throughout, ask yourself whether your action research project is helping you (and those with whom you work) to improve the extent to which you are living your educational values [italics in original].

It is clear from this list that action research is a blend of practical and theoretical concerns; it is both action and research.

In conducting action research the participants can be both methodologically eclectic and can use a variety of instruments for data collection: questionnaires, diaries, interviews, case studies, observational data, experimental design, field notes, photography, audio and video recording, sociometry, rating scales, biographies and accounts, documents and records, in short the full gamut of techniques (for a discussion of these see Hopkins, 1985; McKernan, 1991, and the chapters in our own book here).

Additionally a useful way of managing to gain a focus within a group of action researchers is through the use of Nominal Group Technique (Morrison, 1993). The administration is straightforward and is useful for gathering information in a single instance. In this approach one member of the group provides the group with a series of questions, statements or issues. A four-stage model can be adopted:

Stage 1: A short time is provided for individuals to write down without interruption or discussion with anybody else their own answers, views, reflections and opinions in response to questions/statements/issues provided by the group leader (e.g. problems of teaching or organizing such-and-such, or an identification of issues in the organization of a piece of the curriculum, etc.).

Stage 2: The responses are entered onto a sheet of paper which is then displayed for others to view. The leader invites individual comments on the displayed responses to the questions/statements/issue, but no group discussion, i.e. the data collection is still at an individual level, and then notes these comments on the display sheet on which the responses have been collected. The process of inviting individual comments/contributions which are then displayed for everyone to see is repeated until no more comments are received.

Stage 3: At this point the leader asks the respondents to identify clusters of displayed comments and responses, i.e. to put some structure, order and priority into the displayed items. It is here that control of proceedings moves from the leader to the participants. A group discussion takes place since a process of clarification of meanings and organizing issues and responses into coherent and cohesive bundles is required which then moves to the identification of priorities.

Stage 4: Finally the leader invites any further group discussion about the material and its organization.

The process of the Nominal Group Technique enables individual responses to be included within a group response, i.e. the individual’s contribution to the group delineation of significant issues is maintained. This technique is very useful in gathering data from individuals and putting them into some order which is shared by the group (and action research is largely, though not exclusively, a group matter), e.g. of priority, of similarity and difference, of generality and specificity. It also enables individual disagreements to be registered and to be built into the group responses and identification of significant issues to emerge. Further, it gives equal status to all respondents in the situation, for example, the voice of the new entrant to the teaching profession is given equal consideration to the voice of the head teacher of several years’ experience. The attraction of this process is that it balances writing with discussion, a divergent phase with a convergent phase, space for individual comments and contributions to group interaction. It is a useful device for developing collegiality. All participants have a voice and are heard.

The written partner to the Nominal Group Technique is the Delphi technique. This has the advantage that it does not require participants to meet together as a whole group. This is particularly useful in institutions where time is precious and where it is difficult to arrange a whole group meeting. The process of data collection resembles that of the Nominal Group Technique in many respects: it can be set out in a three-stage process:

Stage 1: The leader asks participants to respond to a series of questions and statements in writing. This may be done on an individual basis or on a small group basis – which enables it to be used flexibly, e.g. within a department, within an age phase.

Stage 2: The leader collects the written responses and collates them into clusters of issues and responses (maybe providing some numerical data on frequency of response). This analysis is then passed back to the respondents for comment, further discussion and identification of issues, responses and priorities. At this stage the respondents are presented with a group response (which may reflect similarities or record differences) and the respondents are asked to react to this group response. By adopting this procedure the individual has the opportunity to agree with the group response (i.e. to move from a possibly small private individual disagreement to a general group agreement) or to indicate a more substantial disagreement with the group response.

Stage 3: This process is repeated as many times as it is necessary. In saying this, however, the leader will need to identify the most appropriate place to stop the recirculation of responses. This might be done at a group meeting which, it is envisaged, will be the plenary session for the participants, i.e. an endpoint of data collection will be in a whole group forum.

By presenting the group response back to the participants, there is a general progression in the technique towards a polarizing of responses, i.e. a clear identification of areas of consensus and dissensus (and emancipatory action research strives for consensus). The Delphi technique brings advantages of clarity, privacy, voice and collegiality. In doing so it engages the issues of confidentiality, anonymity and disclosure of relevant information whilst protecting participants’ rights to privacy. It is a very useful means of undertaking behind-the-scenes data collection which can then be brought to a whole group meeting; the price that this exacts is that the leader has much more work to do in collecting, synthesizing, collating, summarizing, prioritizing and re-circulating data than in the Nominal Group Technique, which is immediate. As participatory techniques both the Nominal Group Technique and Delphi techniques are valuable for data collection and analysis in action research.

McNiff and Whitehead (2009: 15) argue that, in reporting action research, it is important to note not only the action but the research element, including the rigorous methodology and interpretation of data. They suggest that it is important to state clearly:

The research issue and how it came to become a research issue in the improvement of practice.

The research issue and how it came to become a research issue in the improvement of practice.

The methodology of, and justification for, the intervention, and how it was selected from amongst other possible interventions.

The methodology of, and justification for, the intervention, and how it was selected from amongst other possible interventions.

How the intervention derived from an understanding of the situation.

How the intervention derived from an understanding of the situation.

What data were collected, when and from whom.

What data were collected, when and from whom.

How data were collected, processed and analysed.

How data were collected, processed and analysed.

How the intervention was monitored and reviewed.

How the intervention was monitored and reviewed.

How reflexivity was addressed.

How reflexivity was addressed.

What were the standard and criteria for success, and how these criteria were derived.

What were the standard and criteria for success, and how these criteria were derived.

How conclusions were reached and how these were validated.

How conclusions were reached and how these were validated.