ethical issues

ethical issuesQuestionnaires |

CHAPTER 20 |

The field of questionnaire design is vast. This chapter provides a straightforward introduction to its key elements, indicating the main issues to be addressed, some important problematical considerations and how they can be resolved. It follows a sequence in designing a questionnaire that, it is hoped, will be useful for researchers, thus:

ethical issues

ethical issues

approaching the planning of a questionnaire

approaching the planning of a questionnaire

operationalizing the questionnaire

operationalizing the questionnaire

structured, semi-structured and unstructured questionnaires

structured, semi-structured and unstructured questionnaires

types of questionnaire items

types of questionnaire items

closed and open questions compared

closed and open questions compared

scales of data

scales of data

the dangers of assuming knowledge

the dangers of assuming knowledge

dichotomous questions

dichotomous questions

multiple choice questions

multiple choice questions

rank ordering

rank ordering

rating scales

rating scales

constant sum questions

constant sum questions

ratio data questions

ratio data questions

open-ended questions

open-ended questions

matrix questions

matrix questions

contingency questions, filters and branches

contingency questions, filters and branches

asking sensitive questions

asking sensitive questions

avoiding pitfalls in question writing

avoiding pitfalls in question writing

sequencing questions

sequencing questions

questionnaires containing few verbal items

questionnaires containing few verbal items

the layout of the questionnaire

the layout of the questionnaire

covering letters/sheets and follow-up letters

covering letters/sheets and follow-up letters

piloting the questionnaire

piloting the questionnaire

practical considerations in questionnaire design

practical considerations in questionnaire design

administering questionnaires

administering questionnaires

self-administered questionnaires

self-administered questionnaires

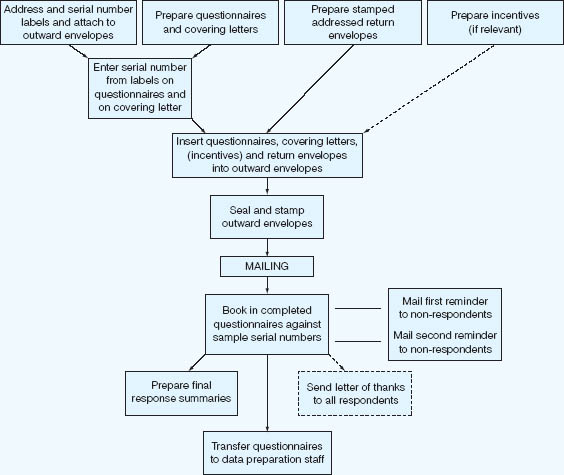

postal questionnaires

postal questionnaires

processing questionnaire data

processing questionnaire data

It is suggested that researchers may find it useful to work through these issues in sequence, though, clearly, a degree of recursion is desirable.

We advise readers to take this chapter together with the other chapters in this book on surveys, sampling and interviewing. Indeed Chapter 13 (Surveys) addresses important materials on online questionnaires, and we advise readers to consult that in detail. Part 5 concerns data analysis, and this can include analysis of quantitative and qualitative data.

The questionnaire is a widely used and useful instrument for collecting survey information, providing structured, often numerical data, being able to be administered without the presence of the researcher, and often being comparatively straightforward to analyse (Wilson and McLean, 1994). These attractions have to be counterbalanced by the time taken to develop, pilot and refine the questionnaire, by the possible unsophistication and limited scope of the data that are collected, and from the likely limited flexibility of response (though, as Wilson and McLean (1994: 3) observe, this can frequently be an attraction). The researcher will have to judge the appropriateness of using a questionnaire for data collection, and, if so, what kind of questionnaire it should be.

The questionnaire will always be an intrusion into the life of the respondent, be it in terms of time taken to complete the instrument, the level of threat or sensitivity of the questions, or the possible invasion of privacy. Questionnaire respondents are not passive data providers for researchers; they are subjects not objects of research. There are several sequiturs that flow from this.

Respondents cannot be coerced into completing a questionnaire. They might be strongly encouraged, but the decision whether to become involved and when to withdraw from the research is entirely theirs. Their involvement in the research is likely to be a function of:

a their informed consent (see Chapter 5 on the ethics of educational research);

b their rights to withdraw at any stage or not to complete particular items in the questionnaire;

c the potential of the research to improve their situation (the issue of beneficence);

d the guarantees that the research will not harm them (the issue of non-maleficence);

e the guarantees of confidentiality, anonymity and non-traceability in the research;

f the degree of threat or sensitivity of the questions (which may lead to respondents’ over-reporting or under-reporting (Sudman and Bradburn, 1982: 32 and Chapter 3));

g factors in the questionnaire itself (e.g. its coverage of issues, its ability to catch what respondents want to say rather than to promote the researcher’s agenda), i.e. the avoidance of bias and the assurance of validity and reliability in the questionnaire – the issues of methodological rigour and fairness. Methodological rigour is an ethical not simply a technical matter (Morrison, 1996b), and respondents have a right to expect reliability and validity;

h the reactions of the respondent, for example, respondents will react if they consider an item to be offensive, intrusive, misleading, biased, misguided, irritating, inconsiderate, impertinent or abstruse.

These factors impact on every stage of the use of a questionnaire, to suggest that attention has to be given to the questionnaire itself, the approaches that are made to the respondents, the explanations that are given to the respondents, the data analysis and the data reporting.

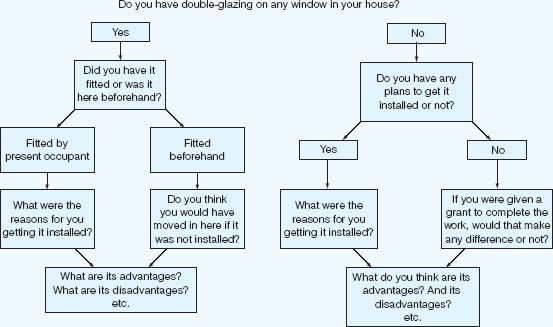

At this preliminary stage of design, it can sometimes be helpful to use a flow chart technique to plan the sequencing of questions. In this way, researchers are able to anticipate the type and range of responses that their questions are likely to elicit. In Figure 20.1 we illustrate a flow chart employed in a commercial survey based upon an interview schedule, though the application of the method to a self-completion questionnaire is self-evident.

On a more positive note, Sellitz and her associates (1976) have provided a fairly exhaustive guide to researchers in constructing their questionnaires which we summarize in Box 20.1.

These are introductory issues, and the remainder of this chapter takes each of these and unpacks them in greater detail. Additionally, one can set out a staged sequence for planning a questionnaire, thus:

FIGURE 20.1 A flow chart technique for question planning

Source: Social and Community Planning Research, 1972

1 Decide the purposes/objectives of the questionnaire.

2 Decide the population and the sample (as questions about their characteristics will need to be included on the questionnaire under ‘personal details’).

3 Generate the topics/constructs/concepts/issues to be addressed and data required in order to meet the objectives of the research (this can be done from literature, or a pre-pilot, for example, focus groups and semi-structured interviews).

4 Decide the kinds of measures/scales/questions/responses required.

5 Write the questionnaire items.

6 Check that each issue from (3) has been addressed, using several items for each issue.

7 Pilot the questionnaire and refine items as a consequence.

8 Administer the final questionnaire.

Within these stages there are several sub-components, and this chapter addresses these.

The process of operationalizing a questionnaire is to take a general purpose or set of purposes and turn these into concrete, researchable fields about which actual data can be gathered. First, a questionnaire’s general purposes must be clarified and then translated into a specific, concrete aim or set of aims. Thus, ‘to explore teachers’ views about in-service work’ is somewhat nebulous, whereas ‘to obtain a detailed description of primary and secondary teachers’ priorities in the provision of in-service education courses’ is reasonably specific.

A Decisions about question content

1 Is the question necessary? Just how will it be useful?

2 Are several questions needed on the subject matter of this question?

3 Do respondents have the information necessary to answer the question?

4 Does the question need to be more concrete, specific and closely related to the respondent’s personal experience?

5 Is the question content sufficiently general and free from spurious concreteness and specificity?

6 Do the replies express general attitudes and only seem to be as specific as they sound?

7 Is the question content biased or loaded in one direction, without accompanying questions to balance the emphasis?

8 Will the respondents give the information that is asked for?

B Decisions about question wording

1 Can the question be misunderstood? Does it contain difficult or unclear phraseology?

2 Does the question adequately express the alternative with respect to the point?

3 Is the question misleading because of unstated assumptions or unseen implications?

4 Is the wording biased? Is it emotionally loaded or slanted towards a particular kind of answer?

5 Is the question wording likely to be objectionable to the respondent in any way?

6 Would a more personalized wording of the question produce better results?

7 Can the question be better asked in a more direct or a more indirect form?

C Decisions about form of response to the question

1 Can the question best be asked in a form calling for check answer (or short answer of a word or two, or a number), free answer or check answer with follow-up answer?

2 If a check answer is used, which is the best type for this question – dichotomous, multiple choice (‘cafeteria’ question), or scale?

3 If a checklist is used, does it cover adequately all the significant alternatives without overlapping and in a defensible order? Is it of reasonable length? Is the wording of items impartial and balanced?

4 Is the form of response easy, definite, uniform and adequate for the purpose?

D Decisions about the place of the question in the sequence

1 Is the answer to the question likely to be influenced by the content of preceding questions?

2 Is the question led up to in a natural way? Is it in correct psychological order?

3 Does the question come too early or too late from the point of view of arousing interest and receiving sufficient attention, avoiding resistance, and so on?

Source: Adapted from Sellitz et al, 1976

Having decided upon and specified the primary objective of the questionnaire, the second phase of the planning involves the identification and itemizing of subsidiary topics that relate to its central purpose. In our example, subsidiary issues might well include: the types of courses required; the content of courses; the location of courses; the timing of courses; the design of courses; and the financing of courses.

The third phase follows the identification and itemization of subsidiary topics and involves formulating specific information requirements relating to each of these issues. For example, with respect to the type of courses required, detailed information would be needed about the duration of courses (one meeting, several meetings, a week, a month, a term or a year), the status of courses (non-award bearing, award bearing, with certificate, diploma, degree granted by college or university), the orientation of courses (theoretically oriented involving lectures, readings, etc., or practically oriented involving workshops and the production of curriculum materials).

What we have in the example, then, is a move from a generalized area of interest or purpose to a very specific set of features about which direct data can be gathered. Wilson and McLean (1994: 8–9) suggest an alternative approach which is to identify the research problem, then to clarify the relevant concepts or constructs, then to identify what kinds of measures (if appropriate) or empirical indicators there are of these, i.e. the kinds of data required to give the researcher relevant evidence about the concepts or constructs, e.g. their presence, their intensity, their main features and dimensions, their key elements, etc.

What unites these two approaches is their recognition of the need to ensure that the questionnaire: (a) is clear on its purposes; (b) is clear on what needs to be included or covered in the questionnaire in order to meet the purposes; (c) is exhaustive in its coverage of the elements of inclusion; (d) asks the most appropriate kinds of question (discussed below); (e) elicits the most appropriate kinds of data to answer the research purposes and sub-questions; (f) asks for empirical data.

When planning a questionnaire it is important to plan so that the questionnaire is set up – structured – in such a way that the data analysis can proceed as planned. So, for example, if the researcher wishes to conduct multiple regression (e.g. to find out the relative weights of a range of independents variables on a dependent variable, for example the relative strength of three independent variables – teaching preparation, teacher/student relationships and subject knowledge – on the dependent variable of teaching effectiveness) then both the independent and dependent variables must be included in the questionnaire. This might appear thus (though the questions below may appear to be leading questions, the student is given the option of scoring a zero, i.e. ‘not at all’):

A general question (dependent variable): ‘Overall, how effective do you think the teaching is in this Mathematics department?’

A general question (dependent variable): ‘Overall, how effective do you think the teaching is in this Mathematics department?’

A specific question (independent variable): ‘How well prepared for her/his teaching is the Mathematics teacher?’

A specific question (independent variable): ‘How well prepared for her/his teaching is the Mathematics teacher?’

A specific question (independent variable): ‘How positive are the teacher/student relationships in the Mathematics department?’

A specific question (independent variable): ‘How positive are the teacher/student relationships in the Mathematics department?’

A specific question (independent variable): ‘How well do you think that the teacher knows his/her subject in the Mathematics department?’

A specific question (independent variable): ‘How well do you think that the teacher knows his/her subject in the Mathematics department?’

Let us imagine that there is an 11-point scale, where zero (‘0’) means ‘not at all’ and 10 means ‘very much’. Here the scales are the same (11 points), the dependent variable is included, and each independent variable is included. Whilst this sounds like common sense, our experience has led to us make this point, as too many times students omit the dependent variable.

As a second example, let us imagine that the researcher is investigating the reason why undergraduate students take part-time jobs (cf. Morrison and Tam, 2005). She asks the general question (dependent variable): ‘What are your main reasons for taking part-time jobs? Please indicate the level of importance of each of the following reasons by encircling the appropriate rating (0–10), where 0=“Of no importance” and 10=“of very great importance”‘. She then asks respondents to give a score out of 10 for the importance of each of several possible reasons for taking a part-time job (independent variables), for example:

meet necessary study expenses

meet necessary study expenses

meet living expenses

meet living expenses

purchase better consumer products

purchase better consumer products

support entertainment expenses

support entertainment expenses

for extra money to spend

for extra money to spend

support family expenses

support family expenses

gain job experience

gain job experience

fill-in spare time

fill-in spare time

affected by peer group.

affected by peer group.

She can then conduct a multiple regression to see the relative importance of each of these independent variables on the dependent variables (e.g. using standardized beta values, discussed in Part 5 of this book).

If the researcher wishes to conduct factor analysis then the variables must be at the ratio level of data (discussed below). If structural equation modelling is required then both variables and factors have to be calculated, and these have to be able to be calculated in the questionnaire. If simple frequencies, percentages and correlations are to be calculated then the questions must be framed in such a way that they can be calculated. This is a statement of the obvious, but, in our experience, too many students neglect the obvious.

A researcher may not wish to conduct such high-level data analysis, and often simple frequencies will suffice and will be very persuasive. This, too, can suggest causality (though not prove it – see Chapter 4), or, at least correlation. Let us imagine that the researcher is looking into the effects of communication on leadership in a very large secondary school (160 teachers). She asks three simple questions:

1 Generally, how effective is the overall leadership in the school (tick one only):

Good

Good  Not Good

Not Good

2 Generally, how effective is the principal’s communication in the school (tick one only):

Good

Good  Not Good

Not Good

3 Generally, how willing to communicate is the school principal (tick one only):

Good

Good  Not Good

Not Good

These simple dichotomous questions require respondents to come to a judgement; they are not permitted to ‘sit on the fence’, they have to make up their minds. In tabular form, the results could be presented as shown in Table 20.1 (fictitious figures). In Table 20.1 ‘effective leadership’ is reported by 82 respondents (51.2 per cent) (45 + 15 + 10 + 12); ‘not good’ leadership is reported by 78 respondents (48.8 per cent) (3 + 12+5+58). Table 20.1 indicates that, for ‘good’ leadership to be present in its strongest form requires the factors ‘principal’s communication’ and ‘willingness to communicate’ to be present and ‘good’, and that if either or both of these factors is ‘not good’ then ‘good’ knowledge management drops dramatically.

The point to be made here is that the questionnaire is designed – set up – with the analysis in mind; the researcher knows in advance how she wants to analyse the data, and the structure and contents of the questionnaire follow from this.

Though there is a large range of types of questionnaire, there is a simple rule of thumb: the larger the size of the sample, the more structured, closed and numerical the questionnaire may have to be, and the smaller the size of the sample, the less structured, more open and word-based the questionnaire may be.

The researcher can select several types of questionnaire, from highly structured to unstructured. If a closed and structured questionnaire is used, enabling patterns to be observed and comparisons to be made, then the questionnaire will need to be piloted and refined so that the final version contains as full a range of possible responses as can be reasonably foreseen. Such a questionnaire is heavy on time early in the research; however, once the questionnaire has been ‘set up’ then the mode of analysis might be comparatively rapid. For example, it may take two or three months to devise a survey questionnaire, pilot it, refine it and set it out in a format that will enable the data to be processed and statistics to be calculated. However, the ‘trade-off’ from this is that the data analysis can be undertaken fairly rapidly – we already know the response categories, the nature of the data and the statistics to be used; it is simply a matter of processing the data – often using computer analysis.

TABLE 20.1 CROSSTABULATION OF RESPONSES TO TWO KEY FACTORS IN EFFECTIVE LEADERSHIP

Effective leadership |

Principal’s communication |

Willingness to communicate |

Frequency (% rounded) |

Good |

Good |

Good |

45(28.1%) |

Good |

Good |

Not good |

15(9.4%) |

Good |

Not good |

Good |

10(6.2%) |

Good |

Not good |

Not good |

12(7.5%) |

Not good |

Good |

Good |

3(1.9%) |

Not good |

Good |

Not good |

12(7.5%) |

Not good |

Not good |

Good |

5(3.1%) |

Not good |

Not good |

Not good |

58 (36.3%) |

Total |

|

|

160(100%) |

It is perhaps misleading to describe a questionnaire as being ‘unstructured’, as the whole devising of a questionnaire requires respondents to adhere to some form of given structure. That said, between a completely open questionnaire that is akin to an open invitation to ‘write what one wants’ and a completely closed, completely structured questionnaire, there is the powerful tool of the semi-structured questionnaire. Here a series of questions, statements or items are presented and the respondents are asked to answer, respond to or comment on them in a way that they think best. There is a clear structure, sequence, focus, but the format is open-ended, enabling respondents to reply in their own terms. The semi-structured questionnaire sets the agenda but does not presuppose the nature of the response.

There are several kinds of question and response modes in questionnaires, including, for example: dichotomous questions; multiple choice questions; rating scales; constant sum questions; ratio data and open-ended questions. These are considered below (see also Wilson, 1996). Closed questions prescribe the range of responses from which the respondent may choose. Highly structured, closed questions are useful in that they can generate frequencies of response amenable to statistical treatment and analysis. They also enable comparisons to be made across groups in the sample (Oppenheim, 1992: 115). They are quicker to code up and analyse than word-based data (Bailey, 1994: 118), and, often, they are directly to the point and deliberately more focused than open-ended questions. Indeed it would be almost impossible, as well as unnecessary, to try to process vast quantities of word-based data in a short time frame.

If a site-specific case study is required, then qualitative, less structured, word-based and open-ended questionnaires may be more appropriate as they can capture the specificity of a particular situation. Where measurement is sought then a quantitative approach is required; where rich and personal data are sought, then a word-based qualitative approach might be more suitable. Open-ended questions are useful if the possible answers are unknown or the questionnaire is exploratory (Bailey, 1994: 120), or if there are so many possible categories of response that a closed question would contain an extremely long list of options. They also enable respondents to answer as much as they wish, and are particularly suitable for investigating complex issues, to which simple answers cannot be provided. Open questions may be useful for generating items that will subsequently become the stuff of closed questions in a subsequent questionnaire (i.e. a pre-pilot).

In general closed questions (dichotomous, multiple choice, constant sum and rating scales) are quick to complete and straightforward to code (e.g. for computer analysis), and do not discriminate unduly on the basis of how articulate respondents are (Wilson and McLean, 1994: 21). On the other hand they do not enable respondents to add any remarks, qualifications and explanations to the categories, and there is a risk that the categories might not be exhaustive and that there might be bias in them (Oppenheim, 1992: 115).

Open questions enable participants to write a free account in their own terms, to explain and qualify their responses and avoid the limitations of pre-set categories of response. On the other hand open questions can lead to irrelevant and redundant information; they may be too open-ended for the respondent to know what kind of information is being sought; they may require much more time from the respondent to enter a response (thereby leading to refusal to complete the item), and they may make the questionnaire appear long and discouraging. With regard to analysis, the data are not easily compared across participants, and the responses are difficult to code and to classify.

We consider in more detail below the different kinds of closed and open questions.

The questionnaire designer will need to choose the metric – the scale of data – to be adopted. This concerns numerical data, and we advise readers to turn to Part 5 for an analysis of the different scales of data that can be gathered (nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio), and the different statistics that can be used for analysis. Nominal data indicate categories; ordinal data indicate order (‘high’ to low’, ‘first’ to ‘last’, ‘smallest’ to ‘largest’, ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, ‘not at all’ to ‘a very great deal’); ratio data indicate continuous values and a true zero (e.g. marks in a test, number of attendances per year, hours spent on study). These are presented thus:

QUESTION TYPE |

LEVEL OF DATA |

Dichotomous questions |

Nominal |

Multiple choice questions |

Nominal |

Rank ordering |

Ordinal |

Rating scales |

Ordinal |

Constant sum questions |

Ordinal |

Ratio data questions |

Ratio |

Open-ended questions |

Word-based data |

There is often an assumption that respondents will have the information or have an opinion about the matters in which researchers are interested. This is a dangerous assumption. It is particularly a problem when administering questionnaires to children, who may write anything rather than nothing. This means that the opportunity should be provided for respondents to indicate that they have no opinion, or that they don’t know the answer to a particular question, or to state that that they feel the question does not apply to them. This is frequently a matter in surveys of customer satisfaction in social science, where respondents are asked, for example, to answer a host of questions about the services provided by utility companies (electricity, gas, water, telephone) about which they have no strong feelings, and, in fact, they are only interested in whether the service is uninterrupted, reliable, cheap, easy to pay for, and that their complaints are solved.

There is also the issue of choice of vocabulary and the concepts and information behind them. It is essential that, regardless of the type of question asked, the language and the concepts behind the language should be within the grasp of the respondents. Simply because the researcher is interested in, and has a background in, a particular topic is no guarantee that the respondents will be like-minded. The effect of the questionnaire on the respondent has to be considered carefully.

A highly structured questionnaire will ask closed questions. These can take several forms. Dichotomous questions require a ‘yes’/‘no’ response, e.g. ‘have you ever had to appear in court?’, ‘do you prefer didactic methods to child-centred methods?’. The layout of a dichotomous question can be thus:

Sex (please tick): Male  Female

Female

The dichotomous question is useful, for it compels respondents to ‘come off the fence’ on an issue. It provides a clear, unequivocal response. Further, it is possible to code responses quickly, there being only two categories of response. A dichotomous question is also useful as a funnelling or sorting device for subsequent questions, for example: ‘if you answered “yes” to question X, please go to question Y; if you answered “no” to question X, please go to question Z’ (see the section below on contingency questions). Sudman and Bradburn (1982: 89) suggest that if dichotomous questions are being used, then it is desirable to use several to gain data on the same topic, in order to reduce the problems of respondents ‘guessing’ answers.

On the other hand, the researcher must ask, for instance, whether a ‘yes’/‘no’ response actually provides any useful information. Requiring respondents to make a ‘yes’/‘no’ decision may be inappropriate; it might be more appropriate to have a range of responses, for example in a rating scale. There may be comparatively few complex or subtle questions which can be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’. A ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ may be inappropriate for a situation whose complexity is better served by a series of questions which catch that complexity. Further, Youngman (1984: 163) suggests that it is a natural human tendency to agree with a statement rather than to disagree with it; this suggests that a simple dichotomous question might build in respondent bias. Indeed people may be more reluctant to agree with a negative statement than to disagree with a positive question (Weems et al., 2003).

In addition to dichotomous questions (‘yes’/‘no’ questions), a piece of research might ask for information about dichotomous variables, for example gender (male/female), type of school (elementary/secondary), type of course (vocational/non-vocational). In these cases only one of two responses can be selected. This enables nominal data to be gathered, which can then be processed using the chi-square statistic, the binomial test, the G-test, and crosstabulations (see Cohen and Holliday (1996) for examples). Dichotomous questions are treated as nominal data (see Part 5).

To try to gain some purchase on complexity, the researcher can move towards multiple choice questions, where the range of choices is designed to capture the likely range of responses to given statements. For example, the researcher might ask a series of questions about a new chemistry scheme in the school; a statement precedes a set of responses thus:

The New Intermediate Chemistry Education (NICE) is:

(a) a waste of time;

(b) an extra burden on teachers;

(c) not appropriate to our school;

(d) a useful complementary scheme;

(e) a useful core scheme throughout the school;

(f) well-presented and practicable.

The categories would have to be discrete (i.e. having no overlap and being mutually exclusive) and would have to exhaust the possible range of responses. Guidance would have to be given on the completion of the multiple choice, clarifying, for example, whether respondents are able to tick only one response (a single answer mode) or several responses (multiple answer mode) from the list. Like dichotomous questions, multiple choice questions can be quickly coded and quickly aggregated to give frequencies of response. If that is appropriate for the research, then this might be a useful instrument.

The layout of a multiple choice question can be thus:

Number of years in teaching

1–5 |

|

6–14 |

|

15–24 |

|

25+ |

|

Which age group do you teach at present (you may tick more than one)?

Infant |

|

Primary |

|

Secondary (excluding sixth form) |

|

Sixth form only |

|

Just as dichotomous questions have their parallel in dichotomous variables, so multiple choice questions have their parallel in multiple elements of a variable. For example, the researcher may be asking to which form a student belongs – there being up to, say, 40 forms in a large school, or the researcher may be asking which post-16 course a student is following (e.g. academic, vocational, manual, non-manual). In these cases only one response may be selected. As with the dichotomous variable, the listing of several categories or elements of a variable (e.g. form membership and course followed) enables nominal data to be collected and processed using the chi-square statistic, the G-test, and crosstabulations (Cohen and Holliday, 1996). Multiple choice questions are treated as nominal data (see Part 5).

It may be important to include in the multiple choices those that will enable respondents to select the response that most closely represents their view, hence a pilot is needed to ensure that the categories are comprehensive, exhaustive and representative. On the other hand, the researcher may be only interested in certain features, and it is these that would figure in the response categories.

The multiple choice questionnaire seldom gives more than a crude statistic, for words are inherently ambiguous. In the example above of chemistry, the notion of ‘useful’ is unclear, as are ‘appropriate’, ‘practicable’ and ‘burden’. Respondents could interpret these words differently in their own contexts, thereby rendering the data ambiguous. One respondent might see the utility of the chemistry scheme in one area and thereby say that it is useful – ticking (d). Another respondent might see the same utility in that same one area but because it is only useful in that single area may see this as a flaw and therefore not tick category (d). With an anonymous questionnaire this difference would be impossible to detect.

This is the heart of the problem of questionnaires – that different respondents interpret the same words differently. ‘Anchor statements’ can be provided to allow a degree of discrimination in response (e.g. ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, etc.) but there is no guarantee that respondents will always interpret them in the way that is intended. In the example above this might not be a problem as the researcher might only be seeking an index of utility – without wishing to know the areas of utility or the reasons for that utility. The evaluator might be wishing only for a crude statistic (which might be very useful statistically in making a decisive judgement about a programme). In this case this rough and ready statistic might be perfectly acceptable.

One can see in the example of chemistry above not only ambiguity in the wording but a very incomplete set of response categories which is hardly capable of representing all aspects of the chemistry scheme. That this might be politically expedient cannot be overlooked, for if the choice of responses is limited, then those responses might enable bias to be built into the research. For example, if the responses were limited to statements about the utility of the chemistry scheme, then the evaluator would have little difficulty in establishing that the scheme was useful. By avoiding the inclusion of negative statements or the opportunity to record a negative response the research will surely be biased. The issue of the wording of questions has been discussed earlier.

Multiple choice items are also prone to problems of word order and statement order. For example, Dillman et al. (2003: 6) report a study of sports, in which tennis was found to be less exciting than football when the tennis option was presented before the football option, and more exciting when the football option was placed before the tennis option. This suggests that respondents tend to judge later items in terms of the earlier items, rather than vice versa and that they overlook features specific to later items if these are not contained in the earlier items. This is an instance of the ‘primacy effect’ or ‘order effect’, wherein items earlier in a list are given greater weight than items lower in the list. Order effects are resilient to efforts to minimize them, and primacy effects are particularly strong in internet questionnaires (Dillman et al., 2003: 22). Preceding questions and the answers given may influence responses to subsequent questions (Schwartz et al., 1998: 177).

Order effects and the primacy effects are examples of context effects, in which some questions in the questionnaire (sometimes coming later in the questionnaire, as respondents do not always answer questions in the given sequence, and may scan the whole questionnaire before answering specific items) may effect the responses given to other questions in the questionnaire (Friedman and Amoo, 1999: 122), biasing the responses by creating a specific mindset, i.e. a predisposition to answering questions in a particular way.

The rank order question is akin to the multiple choice question in that it identifies options from which respondents can choose, yet it moves beyond multiple choice items in that it asks respondents to identify priorities. This enables a relative degree of preference, priority, intensity, etc. to be charted. Rank ordering requires respondents to compare values across variables; in this respect they are unlike rating scales in which the values are entered independently of each other (Ovadia, 2004: 404), i.e. the category ‘strongly agree’ can be applied to a single variable without any regard to what one enters for any other variable. In a ranking exercise the respondent is required to take account of the other variables, because he/she is being asked to see their relative value, weighting or importance. This means that, in a ranking exercise, the task is fair, i.e. the variables are truly able to be compared and placed in a rank order, they lie on the same scale and/or can be judged on the same criteria.

In the rank ordering exercise a list of factors is set out and the respondent is required to place them in a rank order, for example:

Please indicate your priorities by placing numbers in the boxes to indicate the ordering of your views, 1 =the highest priority, 2 =the second highest, and so on.

The proposed amendments to the mathematics scheme might be successful if the following factors are addressed:

|

the appropriate material resources are in school; |

|

|

the amendments are made clear to all teachers; |

|

|

the amendments are supported by the mathematics team; |

|

|

the necessary staff development is assured; |

|

|

there are subsequent improvements to student achievement; |

|

|

the proposals have the agreement of all teachers; |

|

|

they improve student motivation; |

|

|

parents approve of the amendments; |

|

|

they will raise the achievements of the brighter students; |

|

|

the work becomes more geared to problem-solving. |

|

In this example ten items are listed. Whilst this might be enticing for the researcher, enabling fine distinctions possibly to be made in priorities, it might be asking too much of the respondents to make such distinctions. They genuinely might not be able to differentiate their responses, or they simply might not feel strongly enough to make such distinctions. The inclusion of too long a list might be overwhelming. Indeed Wilson and McLean (1994: 26) suggest that it is unrealistic to ask respondents to arrange priorities where there are more than five ranks that have been requested. In the case of the list of ten points above, the researcher might approach this problem in one of two ways. The list in the questionnaire item can be reduced to five items only, in which case the range and comprehensiveness of responses that fairly catches what the respondent feels is significantly reduced. Alternatively, the list of ten items can be retained, but the request can be made to the respondents only to rank their first five priorities, in which case the range is retained and the task is not overwhelming (though the problem of sorting the data for analysis is increased).

An example of a shorter list might be:

Please place these in rank order of the most to the least important, by putting the position (1–5) against each of the following statements, number one being the most important and number 5 being the least important:

Students should enjoy school |

[ ] |

Teachers should set less homework |

[ ] |

Students should have more choice of subjects in school |

[ ] |

Teachers should use more collaborative methods |

[ ] |

Students should be tested more, so that they work harder |

[ ] |

Rankings may also assume that the different items can truly be placed on a single scale. Consider the example above, where the respondent is required to place five items on a single scale of importance. Can these items really be differentiated according to the single criterion of ‘importance’? Surely ‘fitness for purpose’ and context would suggest that a fairer answer is that ‘it all depends’ on what is happening in a specific context, i.e. even though one could place items in a rank order, in fact it may be meaningless to do so. The items may truly not be comparable (Ovadia, 2004: 405). As Ovadia (2004: 407) reports, valuing justice may say nothing about valuing love, so to place them in a single ranking scale of importance may be meaningless.

Rankings are useful in indicating degrees of response. In this respect they are like rating scales, discussed below. Ranking questions are treated as ordinal data (see Part 5 for a discussion of ordinal data). However, rankings do not enable sophisticated statistical analysis to be conducted (Ovadia, 2004: 405), as the ranks are interdependent rather than independent, and these vary for each respondent, i.e. not only does the rank ‘1st’ mean different things to different respondents, but there are no equal intervals between each rank, and the rank of, say, ‘3rd’ has a different meaning for different respondents, which is relative to their idea of what constitutes ‘2nd’ and ‘4th’, i.e. the rankings are interdependent; there is no truly common metric here. Further, because rankings force a respondent to place items in a rank order, differences between values may be overstated.

Rankings operate on a zero-sum model (Ovadia, 2004: 406), i.e. if one places an item in the 1st position then this means that another item drops in the ranking; this may or may not be desirable, depending on what the researcher wishes to find out. Researchers using rankings will need to consider whether it is fair to ask respondents really to compare items and to judge one item in relation to another; to ask ‘are they really commensurable?’ (able to be measured by the same single standard or criterion).

One way in which degrees of response, intensity of response and the move away from dichotomous questions have been managed can be seen in the notion of rating scales – Likert scales, semantic differential scales, Thurstone scales and Guttman scaling. These are very useful devices for the researcher, as they build in a degree of sensitivity and differentiation of response whilst still generating numbers. This chapter will focus on the first two of these, though readers will find the others discussed in Oppenheim (1992). A Likert scale (named after its deviser, Rensis Likert, 1932) provides a range of responses to a given question or statement, for example:

How important do you consider work placements to be for secondary school students?

1 = not at all

2 = very little

3 = a little

4 = quite a lot

5 = a very great deal

All students should have access to free higher education.

1 = strongly disagree

2 = disagree

3 = neither agree nor disagree

4 = agree

5 = strongly agree

Such a scale could be set out thus:

Please complete the following by placing a tick in one space only, as follows:

1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree;

3 = neither agree nor disagree;

4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree

Senior school staff should teach more

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

In these examples the categories need to be discrete and to exhaust the range of possible responses which respondents may wish to give. Notwithstanding the problems of interpretation which arise as in the previous example – one respondent’s ‘agree’ may be another’s ‘strongly agree’, one respondent’s ‘very little’ might be another’s ‘a little’ – the greater subtlety of response which is built into a rating scale renders this a very attractive and widely used instrument in research.

These two examples both indicate an important feature of an attitude scaling instrument, namely the assumption of unidimensionality in the scale; the scale should only be measuring one thing at a time (Oppenheim, 1992: 187–8). Indeed this is a cornerstone of Likert’s own thinking (1932).

It is a very straightforward matter to convert a dichotomous question into a multiple choice question. For example, instead of asking the ‘do you?’, ‘have you?’, ‘are you?’, ‘can you?’ type questions in a dichotomous format, a simple addition to wording will convert it into a much more subtle rating scale, by substituting the words ‘to what extent?’, ‘how far?’, ‘how much?’, ‘how often?’, etc.

A semantic differential is a variation of a rating scale which operates by putting an adjective at one end of a scale and its opposite at the other, for example:

How informative do you consider the new set of history textbooks to be?

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

useful |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

useless |

Respondents indicate their opinion by circling or putting a mark on that position on the scale which most represents what they feel. Researchers devise their own terms and their polar opposites, for example:

Approachable |

... |

Unapproachable |

Generous |

... |

Mean |

Friendly |

... |

Hostile |

Caring |

... |

Uncaring |

Attentive |

... |

Inattentive |

Hard-working |

... |

Lazy |

Osgood et al. (1957), the pioneers of this technique, suggest that semantic differential scales are useful in three contexts: evaluative (e.g. valuable–valueless, useful–useless, good–bad); potency (e.g. large–small, weak–strong, light–heavy); and activity (e.g. quick–slow; active–passive, dynamic–lethargic).

There are several commonly used categories in rating scales, for example:

Strongly disagree/disagree/neither agree nor disagree/agree/strongly agree

Strongly disagree/disagree/neither agree nor disagree/agree/strongly agree

Very seldom/occasionally/quite often/very often

Very seldom/occasionally/quite often/very often

Very little/a little/somewhat/a lot/a very great deal

Very little/a little/somewhat/a lot/a very great deal

Never/almost never/sometimes/often/very often

Never/almost never/sometimes/often/very often

Not at all important/unimportant/neither important nor unimportant/important/very important

Not at all important/unimportant/neither important nor unimportant/important/very important

Very true of me/a little bit true of me/don’t know/not really true of me/very untrue of me

Very true of me/a little bit true of me/don’t know/not really true of me/very untrue of me

Strongly agree /agree /uncertain /disagree /strongly disagree.

Strongly agree /agree /uncertain /disagree /strongly disagree.

To these could be added the category ‘don’t know’ or ‘have no opinion’. Rating scales are widely used in research, and rightly so, for they combine the opportunity for a flexible response with the ability to determine frequencies, correlations and other forms of quantitative analysis. They afford the researcher the freedom to fuse measurement with opinion, quantity and quality.

Though rating scales are powerful and useful in research, the investigator, nevertheless, needs to be aware of their limitations. For example, the researcher may infer a degree of sensitivity and subtlety from the data that they cannot bear. There are other cautionary factors about rating scales, be they Likert scales or semantic differential scales:

1 There is no assumption of equal intervals between the categories, hence a rating of 4 indicates neither that it is twice as powerful as 2 nor that it is twice as strongly felt; one cannot infer that the intensity of feeling in the Likert scale between ‘strongly agree’ and ‘disagree’ somehow matches the intensity of feeling between ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘agree’. These are illegitimate inferences. The problem of equal intervals has been addressed in Thurstone scales (Thurstone and Chave, 1929; Oppenheim, 1992: 190–5). Friedman and Amoo (1999: 115) suggest that if the researcher wishes to assume equal intervals (‘equal-sized gradations’) between points in the rating scale, then he or she must ensure that the category descriptors are genuinely equal interval. Take, for example, the scale ‘not at all’, ‘very little’, ‘a little’, ‘quite a lot’, ‘a very great deal’. Here the conceptual distance between ‘a little’ and ‘quite a lot’ is much greater than between ‘very little’ and ‘a little’, i.e. there are not equal intervals.

2 Numbers have different meanings for different respondents, so one person may use a particular criterion to award a score of ‘6’ on a seven-point scale, whilst another person using exactly the same criterion would award a score of ‘5’ on the same scale. Here ‘6’ and ‘5’ actually mean the same but the numbers are different. Alternatively, one person looking at a score of, say, 7 marks out of 10 on a ten-point scale would consider that to be a high score, whereas another person looking at the same score would consider it to be moderate only. Similarly the same word has a different meaning for different respondents; one teacher may think that ‘very poor’ is a very negative descriptor, whereas another might think less negatively about it, and what one respondent might term ‘poor’, another respondent, using the same criterion, might term ‘very poor’. Friedman and Amoo (1999: 115) report that there was greater consistency between subjects on the meanings of positive words rather than negative words, and they suggest that, therefore, researchers should use descriptors that have lesser strength at the negative pole of a scale (p. 3). Further, they suggest that temporal words (e.g. ‘very often’, ‘seldom’, ‘fairly often’, ‘occasionally’, etc.) are open to great variation in their meanings for respondents (p. 3).

3 Some rating scales are unbalanced, forcing unrealistic choices to be made, for example in the scale ‘very acceptable’, ‘quite acceptable’, ‘a little acceptable’ ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’, or in the scale ‘excellent, ‘very good’, ‘quite good’, ‘good’ and ‘poor’, there are four positive categories and only one negative category (cf. Friedman and Amoo, 1999: 119). This can skew results. Such imbalance could even be called unethical.

4 Respondents are biased towards the left-hand side of a bipolar scale (Friedman and Amoo, 1999: 120; Hartley and Betts, 2010: 25). For example, if the scale ‘extremely good’ to ‘extremely poor’ runs from left to right respectively, then the results will be different if the same scale is reversed (‘extremely poor’ to ‘extremely good’) and runs from left to right (or, for example, ‘strongly agree’ on the left, to ‘strongly disagree’ on the right and vice versa). Typically, the authors report, the categories on the left-hand side of a scale are used more frequently than those on the right-hand side of a scale. Further, Hartley and Betts (2010: 25) found that those scales that had a positive label in the left-hand side would elicit higher scores than other orderings. Hence researchers must be cautious about putting all the positive categories on the left-hand side alone, as this can result in more respondents using those categories than if they were placed at the right-hand side of the scale, i.e. rating scales may want to mix the item scales so that sometimes there are positive scores on the left and sometimes positive scores on the right.

5 The ‘direction of comparison’ (Friedman and Amoo, 1999: 120) also makes a difference to results. The authors cite an example where students were asked how empathetic their male and female teachers were in regard to academic and personal problems. When the question asked ‘would you say that female teachers were more empathetic ... than the male teachers?’, the mean score of the responses on a nine-point scale was different from that when the question was ‘would you say that male teachers were more empathetic ... than the female teachers?’. In the former, 41 per cent of responses indicated that female teachers were more empathetic, whereas in the latter only 9 per cent of responses indicated that female teachers were more empathetic.

6 We have no check on whether respondents are telling the truth. Some may be deliberately falsifying their replies.

7 We have no way of knowing if the respondent wishes to add any other comments about the issue under investigation. It might be the case that there is something far more pressing about the issue than the rating scale includes but which is condemned to silence for want of a category. A straightforward way to circumvent this issue is to run a pilot and also to include a category entitled ‘other (please state)’.

8 Most of us would not wish to be called extremists; we often prefer to appear like each other in many respects. For rating scales this means that we might wish to avoid the two extreme poles at each end of the continuum of the rating scales, reducing the number of positions in the scales to a choice of three (in a five-point scale). That means that in fact there could be very little choice for us. The way round this is to create a larger scale than a five-point scale, for example a seven-point scale. To go beyond a seven-point scale is to invite a degree of detail and precision which might be inappropriate for the item in question, particularly if the argument set out above is accepted, namely that one respondent’s scale point 3 might be another’s scale point 4. Friedman and Amoo (1999: 120) suggest that five-point to 11-point scales might be most useful, whilst Schwartz et al. (1991: 571) suggest that seven-point scales seem to be best in terms of reliability, the ability of respondents to discriminate between the values in the scales, and the percentages of respondents who are ‘undecided’.

9 Schwartz et al. (1991: 571) report that rating scales that have a verbal label for each point in the scale are more reliable than rating scales that provide labels only for the end points of the numerical scales.

10 If the researcher wishes to use ratio data (discussed in Part 5) in order to calculate more sophisticated level statistics (e.g. regressions, factor analysis, structural equation modelling), then a ratio scale must have a true zero (‘0’) and equal intervals. Many rating scales use an 11-point scale here that runs from 0 to 10, with 0 being ‘not at all’ (or something equivalent to this, depending on the question/item) and 10 being the highest score (e.g. ‘completely’ or ‘excellent’).

11 The end-point descriptors on a scale have a significant effect on the responses (Friedman and Amoo, 1999: 117). For example, if the end points of a scale are extreme (e.g. ‘terrible’ and ‘marvellous’) then respondents will avoid these extremes, whereas if the end points are ‘very bad’ and ‘very good’ then more responses in these categories are chosen.

12 The nature of the scaling may affect significantly the responses given and the range of responses actually given (Schwartz and Bienias, 1990: 63). Further, Schwartz et al. (1991) found that if a scale only had positive integers (e.g. 1 to 10) on a scale of ‘extremely successful’ to ‘not at all successful’ then 34 per cent of respondents chose values in the 1–5 categories. However, when the scale was set at –5 for ‘not at all successful’ and +5 for ‘extremely successful’, then only 13 per cent of respondents chose the equivalent lower 5 values (–5 to 0). The authors surmised that the former scale (0–10) was perceived by respondents to indicate degrees of success, whereas the latter scale (–5 to 0) was perceived by respondents to indicate not only the absence of success but the presence of the negative factor of failure (see also Schwartz et al., 1998: 177). Indeed they reported that respondents were reluctant to use negative scores (p. 572) and that responses to a -5 to +5 scale tended to be more extreme than responses to a 0–10 scale, even when they used the same scale verbal labels. They also suggest (p. 577) that, in a –5 to +5 scale, zero (0) indicates absence of an attribute, whereas in a 0–10 scale a zero (0) indicates the presence of the negative end of the bipolar scale, i.e. the zero has two different meanings, depending on the scale used. Hence researchers must be careful not only on the verbal labels that they use, but the scales and scale points that they use with those same descriptors. Kenett (2006: 409) also comments, in this respect, that researchers will need to consider whether they are asking about a bipolar dimension (e.g. ‘very successful’ to ‘very unsuccessful’) where an attribute and its opposite are included, or whether a single pole is being used (e.g. only degrees of positive response or presence of a factor). For a bipolar dimension a combination of negative and positive numbers on a scale may be useful (with the cautions indicated above), whereas for a singly polar dimension then only positive numbers should be used (cf. Schwartz et al., 1991: 577). In other words, if the researcher is looking to discover the intensity of a single attribute then it is better to use positive numbers only (p. 578).

13 Response alternative may signal the nature of the considerations to be borne in mind by respondents (Gaskell et al., 1994: 243). For example, if one is asking about how often there are incidents of indiscipline in a class, the categories ‘several times each lesson’, ‘several times each morning’, ‘several times each day’ may indicate that a more inclusive, wider definition of ‘indiscipline’ is required than if the categories of ‘several times each week’, ‘several times each month’ or ‘several times each term’ were used. The terms used may frame the nature of the thinking or responses that the respondent uses. The authors suggest that this is particularly the case if some vague phrases are included in the response categories (p. 242). Obtained responses, as Schwartz and Bienias (1990: 62) indicate, are a function of the response alternatives that the researcher has provided. Indeed Bless et al. (1992: 309) indicate that scales which offer higher response categories/values tend to produce higher estimates from the respondents (and that this tendency increases as questions become increasingly difficult (p. 312).

14 There is a tendency for participants to opt for the mid-point of a five- or seven-point scale (the central tendency). This is notably an issue in East Asian respondents, where the ‘doctrine of the mean’ is advocated in Confucian culture. One way to overcome this is to use an even number scaling system, as there is no mid-point. On the other hand, it could be argued that if respondents wish to ‘sit on the fence’ and choose a mid-point, then they should be given the option to do so.

15 Respondents tend to cluster their responses, e.g. around the centre, or around one end or another of the scale, and their responses to one item may affect their responses to another item (e.g. creating a single mindset).

16 Choices may be ‘forced’ by omitting certain categories (e.g. ‘no opinion’, ‘undecided’, ‘don’t know’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’). If the researcher genuinely believes that respondents do, or should, have an opinion then such omissions may be justified. Alternatively, it may be unacceptable to force a choice for want of a category that genuinely lets respondents say what is in their minds, even if their minds are not made up about a factor or if they have a reason for concealing their true feelings. Forcing a choice may lead to respondents having an opinion on matters that they really have no opinion about, or, indeed, on matters that do not exist, e.g. phoney topics (Friedman and Amoo, 1999: 118).

17 On some scales there are mid-points; on the five-point scale it is category three, and on the seven point scale it is category four. The use of an odd number of points on a scale enables this to occur. However, choosing an even number of scale points, for example a six-point scale, might require a decision on rating to be indicated.

For example, suppose a new staffing structure has been introduced into a school and the head teacher is seeking some guidance on its effectiveness. A six-point rating scale might ask respondents to indicate their response to the statement:

The new staffing structure in the school has enabled teamwork to be managed within a clear model of line management.

(Circle one number)

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

strongly agree |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

strongly disagree |

Let us say that one member of staff circled 1, eight staff circled 2, twelve staff circled 3, nine staff circled 4, two staff circled 5, and seven staff circled 6. There being no mid-point on this continuum, the researcher could infer that those respondents who circled 1, 2 or 3 were in some measure of agreement, whilst those respondents who circled 4, 5 or 6 were in some measure of disagreement. That would be very useful for, say, a head teacher, in publicly displaying agreement, there being 21 staff (1+8 + 12) agreeing with the statement and 18 (9+2+7) displaying a measure of disagreement. However, one could point out that the measure of ‘strongly disagree’ attracted seven staff – a very strong feeling – which was not true for the ‘strongly agree’ category, which only attracted one member of staff. The extremity of the voting has been lost in a crude aggregation.

Further, if the researcher were to aggregate the scoring around the two mid-point categories (3 and 4) there would be 21 members of staff represented, leaving nine (1 +8) from categories 1 and 2 and nine (2+7) from categories 5 and 6; adding together categories 1, 2, 5 and 6, a total of 18 is reached, which is less that the 21 total of the two categories 3 and 4. It seems on this scenario that it is far from clear that there was agreement with the statement from the staff; indeed taking the high incidence of ‘strongly disagree’, it could be argued that those staff who were perhaps ambivalent (categories 3 and 4), coupled with those who registered a ‘strongly disagree’ indicate not agreement but disagreement with the statement.

The interpretation of data has to be handled very carefully; ordering them to suit a researcher’s own purposes might be very alluring but quite illegitimate. The golden rule here is that crude data can only yield crude interpretation; subtle statistics require subtle data. The interpretation of data must not distort the data unfairly. Rating scale questions are treated as ordinal data (see Part 5), using modal scores and non-parametric data analysis, though one can find very many examples where this rule has been violated, and non-parametric data have been treated as parametric data. This is unacceptable.

It has been suggested that the attraction of rating scales is that they provide more opportunity than dichotomous questions for rendering data more sensitive and responsive to respondents. This makes rating scales particularly useful for tapping attitudes, perceptions and opinions. The need for a pilot study to devise and refine categories, making them exhaustive and discrete, has been suggested as a necessary part of this type of data collection.

Questionnaires that are going to yield numerical or word-based data can be analysed using computer programs (for example SPSS or Ethnograph, SphinxSurvey, N-Vivo respectively). If the researcher intends to process the data using a computer package it is essential that the layout and coding system of the questionnaire is appropriate for that particular computer package. Instructions for layout in order to facilitate data entry are contained in manuals that accompany such packages.

Rating scales are more sensitive instruments than dichotomous scales. Nevertheless they are limited in their usefulness to researchers by their fixity of response caused by the need to select from a given choice. A questionnaire might be tailored even more to respondents by including open-ended questions to which they can reply in their own terms and own opinions. We consider these later. For further reviews of, and references to, rating scales we refer the reader to Hartley and Betts (2010).

If the researcher wishes respondents to compare variables (items) and award scores for items in relation to each other, then rankings are suitable. If the researcher wishes respondents to give a response/score to variables (items) that are independent of the score awarded to any other variables (items), then ratings should be considered. In the latter, the score that one awards to one variable has no bearing or effect on the score that one awards to another. In practice, the results of many rating scales may enable the researcher to place items in a rank order (Ovadia, 2004: 405), but rating scales may also result in many variables having ties (the same score) in the values given, which may be coincidental or, indeed, the ‘result of indifference’ (Ovadia, 2004: 405) on the part of the respondent to the variable in question (e.g. respondents simply and quickly tick the middle box (e.g. ‘3’ in a five-point scale) going down a list of items).

Rankings force the respondent to use the full range of the scale (the scale here being the number of items included, e.g. if there are ten items then ten rankings must be given). By contrast, ratings do not have such a stringent requirement; respondents may cluster their responses to all the items around one end of a scale (e.g. points ‘5’, ‘6’ and ‘7’ in a seven-point scale, or point ‘3’ in a five-point scale).

Let us imagine that a researcher asked respondents to indicate the importance of three items in respect of student success, and that the scale used was to award points out of ten. Here are the results for respondent A and respondent B (cf. Ovadia, 2004: 407):

Respondent A: working hard (9 points); family pressure (6 points); enjoyment of the subject (5 points).

Respondent B: working hard (6 points); family pressure (4 points); enjoyment of the subject (2 points).

A ranking exercise would accord the same positioning of the items on these two scores: in first place comes ‘working hard’, then ‘family pressure’ and in the lowest position, ‘enjoyment of the subject’. However, as we can see, the actual scores are very different, and respondent A awards much higher scores than respondent B, i.e. for respondent A these items are much more important than for respondent B, and any single item is much more important for respondent A than for respondent B. Whilst rankings and ratings here will yield equally valid results, the issue is one of ‘fitness for purpose’: if the researcher wishes to compare then rankings might be useful, whereas if the researcher wishes to examine actual values then ratings might be more useful.

Further, let us imagine that for respondent A in this example, the score for ‘working hard’ drops by two points over time, the score for ‘family pressure’ drops by one point, and the score for ‘enjoyment of the subject’; drops by three points over time. The result of the ranking, however, remains the same, i.e. even though the level of importance has dropped for these three items; the ranking is insensitive to these changes.

In this type of question respondents are asked to distribute a given number of marks (points) between a range of items. For example:

‘Please distribute a total of ten points among the sentences that you think most closely describe your behaviour. You may distribute these freely: they may be spread out, or awarded to only a few statements, or all allocated to a single sentence if you wish.’

I can take advantage of new opportunities |

[ ] |

I can work effectively with all kinds of people |

[ ] |

Generating new ideas is one of my strengths |

[ ] |

I can usually tell what is likely to work in practice |

[ ] |

I am able to see tasks through to the very end |

[ ] |

I am prepared to be unpopular for the good of the school |

[ ] |

This enables priorities to be identified, comparing highs and lows, and for equality of choices to be indicated, and, importantly, for this to be done in the respondents’ own terms. It requires respondents to make comparative judgements and choices across a range of items. For example, we may wish to distribute ten points for aspects of an individual’s personality:

Talkative |

[ ] |

Cooperative |

[ ] |

Hard-working |

[ ] |

Lazy |

[ ] |

Motivated |

[ ] |

Attentive |

[ ] |

This means that the respondent has to consider the relative weight of each of the given aspects before coming to a decision about how to award the marks. To accomplish this means that the all-round nature of the person, in the terms provided, has to be considered, to see, on balance, which aspect is stronger when compared to another.1

The difficulty with this approach is to decide how many marks can be distributed (a round number, for example ten makes subsequent calculation easily comprehensible) and how many statements/items to include, e.g. whether to have the same number of statements as there are marks, or more or fewer statements than the total of marks. Having too few statements/items does not do justice to the complexity of the issue, and having too many statements/items may mean that it is difficult for respondents to decide how to distribute their marks. Having too few marks available may be unhelpful, but, by contrast, having too many marks and too many statements/items can lead to simple computational errors by respondents. Our advice is to keep the number of marks to ten and the number of statements to around six to eight. Constant sum data are ordinal, and this means that non-parametric analysis can be performed on the data (see Part 5).

We discuss ratio data in Part 5 and we refer the reader to the discussion and definition there. For our purposes here we suggest that ratio data questions deal with continuous variables where there is a true zero, e.g.

How much money do you have in the bank? |

___ |

How many times have you been late for school? |

___ |

How many marks did you score in the mathematics test? |

___ |

How old are you (in years)? |

___ |

Here no fixed answer or category is provided, and the respondent puts in the numerical answer that fits his/her exact figure, i.e. the accuracy is higher, much higher than in categories of data. This enables averages (means), standard deviations, range, and high-level statistics to be calculated, e.g. regression, factor analysis, structural equation modelling (see Part 5).

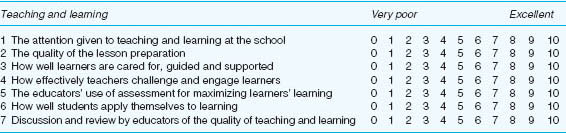

An alternative form of ratio scaling is where the respondent has to award marks out of, say, ten, for a particular item. This is a device that has been used in business and commerce for measuring service quality and customer satisfaction, and is being used in education by Kgaile and Morrison (2006), for example Table 20.2.

This kind of scaling is often used in telephone interviews, as it is easy for respondents to understand. The argument could be advanced that this is a sophisticated form of rating scale, but the terminology used in the instruction clearly suggests that it asks for ratio scale data.

The open-ended question is a very attractive device for smaller scale research or for those sections of a questionnaire that invite an honest, personal comment from respondents in addition to ticking numbers and boxes. The questionnaire simply puts the open-ended questions and leaves a space (or draws lines) for a free response. It is the open-ended responses that might contain the ‘gems’ of information that otherwise might not be caught in the questionnaire. Further, it puts the responsibility for and ownership of the data much more firmly into respondents’ hands.

It is useful for the researcher to provide some support for respondents, so that they know the kind of reply being sought. For example, an open question that includes a prompt could be:

‘Please indicate the most important factors that reduce staff participation in decision making’;

‘Please comment on the strengths and weaknesses of the mathematics course’;

‘Please indicate areas for improvement in the teaching of foreign languages in the school’.

This is not to say that the open-ended question might well not frame the answer, just as the stem of a rating scale question might frame the response given. However, an open-ended question can catch the authenticity, richness, depth of response, honesty and candour which, as is argued elsewhere in this book, are the hallmarks of qualitative data.

TABLE 20.2 A TEN-POINT MARKING SCALE IN A QUESTIONNAIRE

‘Please give a mark from 0 to 10 for the following statements, with 10 being excellent and 0 being very poor. Please circle the appropriate number for each statement.’

Oppenheim (1992: 56–7) suggests that a sentence-completion item is a useful adjunct to an open-ended question, for example:

Please complete the following sentence in your own words:

An effective teacher...

or

The main things that I find annoying with disruptive students are...

Open-endedness also carries problems of data handling. For example, if one tries to convert opinions into numbers (e.g. so many people indicated some degree of satisfaction with the new principal’s management plan), then it could be argued that the questionnaire should have used rating scales in the first place. Further, it might well be that the researcher is in danger of violating one principle of word-based data, which is that they are not validly susceptible to aggregation, i.e. that it is trying to bring to word-based data the principles of numerical data, borrowing from one paradigm (quantitative, positivist methodology) to inform another paradigm (qualitative, interpretive methodology).

Further, if a genuinely open-ended question is being asked, it is perhaps unlikely that responses will bear such a degree of similarity to each other so as to enable them to be aggregated too tightly. Open-ended questions make it difficult for the researcher to make comparisons between respondents, as there may be little in common to compare. Moreover, to complete an open-ended questionnaire takes much longer than placing a tick in a rating scale response box; not only will time be a constraint here, but there is an assumption that respondents will be sufficiently or equally capable of articulating their thoughts and committing them to paper.

In practical terms, Redline et al. (2002) report that using open-ended questions can lead to respondents overlooking instructions, as they are occupied with the more demanding task of writing in their own words than reading instructions.

Despite these cautions, the space provided for an open-ended response is a window of opportunity for the respondent to shed light on an issue or course. Thus, an open-ended questionnaire has much to recommend it.

Matrix questions are not types of questions but concern the layout of questions. Matrix questions enable the same kind of response to be given to several questions, for example ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The matrix layout helps to save space, for example:

Please complete the following by placing a tick in one space only, as follows:

1 =not at all; 2 =very little; 3 =a moderate amount; 4 = quite a lot; 5 = a very great deal

How much do you use the following for assessment purposes?

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

a commercially published tests |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

b your own made-up tests |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

c students’ projects |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

d essays |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

e samples of students’ work |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

[ ] |

Here five questions have been asked in only five lines, excluding, of course, the instructions and explanations of the anchor statements. Such a layout is economical of space.

A second example indicates how a matrix design can save a considerable amount of space in a questionnaire. Here the size of potential problems in conducting a piece of research is asked for, and data on how much these problems were soluble are requested. For the first issue (the size of the problem) 1 = no problem, 2 = a small problem, 3 = a moderate problem, 4 = a large problem, 5 = a very large problem. For the second issue (how much the problem was solved) 1 =not solved at all, 2 = solved only a very little, 3 = solved a moderate amount, 4 = solved a lot, 5 = completely solved. In Table 20.3 30 questions (15 X 2) have been able to be covered in just a short amount of space.

Laying out the questionnaire like this enables the respondent to fill in the questionnaire rapidly. On the other hand, it risks creating a mindset in the respondent (a ‘response set’ (Baker, 1994: 181)) in that the respondent may simply go down the questionnaire columns and write the same number each time (e.g. all number 3) or, in a rating scale, tick all number 3. Such response sets can be detected by looking at patterns of replies and eliminating response sets from subsequent analysis.