In a world in which extraordinary competition exists everywhere you look, doing what you can to give yourself an advantage is not a bad idea. That said, think about modern human sexuality and its impact on the nature of the social world. Mating-relevant factors are arguably responsible for some of the world’s greatest creations (e.g., the song “Let it Be”) as well as some of the social world’s notable disasters (e.g., Ted Bundy’s murderous rampage). The motivations to mate can even affect levels of physical injury by leading to risk-taking behavior and physical conflict during courtship.1 And recent research shows that being shut out of a local mating market has potential to lead to behavior that can be detrimental to oneself or to others—specifically, males who are at risk for being shut out of mating are at increased risk for both suicide and homicide.2

Mating systems drive the nature of the local economy.3 Mating patterns may well hold the secret to the origins of war in our species—with the idea that men form all-male coalitions to launch wars—and that women are often “the spoils of war.” This depiction of war is remarkably consistent across human history and human cultures.4 In short, mating matters. And in a world in which mating matters, improved mating intelligence can help us better understand ourselves and others in our social worlds. Perhaps, for instance, understanding mating’s role in war can help us better understand the roots of war—and how to circumvent war in the future.

A current line of research into mating intelligence pertains to a potential overhaul of modern sex education in the United States. To date, sex education in public schools has focused on details regarding reproductive anatomy, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).5 Without question, these are important issues that need to be taken seriously. However, we believe that current curricula on these topics fall short in terms of context. Sure, it’s important to know how to put a condom on a penis, and it’s important to know why doing so is likely to reduce the probability of unwanted pregnancy and the probability of contracting chronic disease. But shouldn’t there be some context?

In an early interview regarding mating intelligence, Geoffrey Miller6 spoke of an important implication of mating intelligence. To the extent that increasing mating intelligence is beneficial for life as an adult, Miller said, people should be schooled in the skills that make up mating intelligence. Sex education in schools should not be exclusively about the details of copulation. At the end of the day, that’s actually quite boring. What’s exciting, interesting, and important is the fact that human sexuality comprises a set of physiological and behavioral processes that sit at the heart of our nature as evolved organisms. Understanding sex without understanding human mating, along with its social and evolutionary origins, is comparable to understanding how a bicycle tire works without realizing why a bike was made and what its ultimate purpose is (to get people from here to there, if you’re curious).

Given the centrality of mating from an evolutionary perspective in all aspects of human life,7 we believe that sex education for adolescents should shift to mating education. A curriculum for such an educational experience could—and should—include the same elements that typify current sex education curricula—including information on anatomy, contraception, and STDs. However, we believe that it would be beneficial to add content to the curriculum to address such issues as the following:

1. The distinction between long-term and short-term mating

2. Factors sought in potential mates

3. Mating qualities desired by both men and women

4. Mating features that are particularly important to men

5. Mating features that are particularly important to women

6. Personality trade-offs in the mating domain

7. The relevance of paternal uncertainty in driving several elements of the mating process

8. The importance of female choice—and sexual selection generally—to human mating

9. The interface of the mating domain with the parenting domain

10. Sex-differentiated mating processes—including the use of relatively risky strategies by males during courtship

11. The importance and nature of courtship in human mating

12. The importance of kindness and love as central to mating preferences across cultures and sexes

13. Cross-sex mind-reading—parameters of accuracy and biases

14. The evolutionary psychology of sexual harassment and rape—why these processes exert such high evolutionary costs on females and what can be done to prevent these acts

With the help of funding from the National Science Foundation, we are in the process of conducting a study that will develop, implement, and test a newly created sex education curriculum designed with this very reasoning in mind. This mating-relevant curriculum will include the standard features of the New York State sex educational experience along with content that addresses the mating-relevant issues described herein. This curriculum is designed with the following goals:

1. To put sex education in the broader context of evolved human mating psychology

2. To make high school students aware of similarities between the sexes in terms of many features of mating psychology

3. To inform high school students about important psychological differences between the sexes in the area of mating psychology

4. To provide context for understanding issues such as contraception and STDs

5. To develop awareness of gender-specific mating psychology with the goals of creating empathy in mating—which we believe should be a key feature in reducing such adverse outcomes as sexual harassment and rape.

This research will succeed to the extent that we can demonstrate significant effects of the curriculum on important outcomes. The specific outcomes we are studying include: (a) standard measures of knowledge of sexuality, (b) measures of understanding details of human mating psychology and its broad, evolutionary context, and (c) measures of social attitudinal variables such as the “attitude toward women” scale8 and measures of the “sexual objectification” that women often experience.9 Finally, (d) we are including a modified version of the Mating Intelligence Scale10 (see the Epilogue) designed to be appropriate for an adolescent audience.

Our expectation is that students who are exposed to the mating-relevant curriculum will score as well as students who take the standard curriculum on standard measures of knowledge of sexual issues such as STDs and contraception, but should score higher in knowledge of mating psychology and mating intelligence. Further, we expect that students given the enhanced curriculum should demonstrate relatively positive attitudes toward women, less likelihood to objectify women, less likelihood to hold sex-based stereotypes, and less likelihood to hold attitudes that would predispose one toward sexual harassment (these final predictions are particularly relevant for males in the sample).

Although this research on the beneficial effects of a mating intelligence-based sex education curriculum is ongoing, think about the possibilities. This applied research may well improve dramatically the understanding of the social world that young adults find themselves immersed in. Armed with the unmatched explanatory power of evolutionary theory as a set of basic principles, we hope that young adults who learn this curriculum will develop clearer and more informed perspectives on who they are, what their goals are, why sexuality exists, why competition in so many domains exists, why being “nice” has both long-term and short-term benefits, and why long-term mating is the dominant form of mating in our species. Students given standard sex education curricula today simply do not get this experience.

Psychology applied in educational settings, in terms of our current research on a high school health curriculum based on mating intelligence theory, exemplifies scholarship in action that is of broad social value. In fact, applied psychology has many faces beyond educational psychology. Other applied fields of psychology include health psychology (psychology applied to health and medical settings), industrial and organizational psychology (psychology applied to the work world), and sports psychology (psychology applied to issues of athletics and recreation). That said, the most conspicuous form of applied psychology—applied psychology sine qua none—is psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy (a term used here to subsume both clinical and counseling psychology) is pretty much what most people think of when they think of psychology writ large. Sometimes people develop major pathologies that interfere with functioning at all levels, and sometimes people develop anxieties or stress responses that are specific to some particular situation. Everyone has problems at some point.

Can the idea of mating intelligence help lead to improvements in the field of psychotherapy? Before asking this question, it’s useful to think of a more general question: Can evolutionary psychology lead to improvements in psychotherapy? A large and growing group of scholars believe the answer to this broader question is a resounding “YES.” The recently formed Applied Evolutionary Psychology Society (AEPS—yes, from APES TO AEPS!) takes this charge seriously—and is based on the idea that evolutionary psychology is crucial to understanding all aspects of human behavior and is, accordingly, crucial to coming up with solutions to personal and social problems.

To think about how evolutionary psychology can lead to fresh and useful new approaches to psychotherapy, consider the following example: Michael is a young male in his senior year of college. He’s majoring in history and, like many 22-year-olds, has little idea where his career (specifically) and life (generally) are headed. He’s also someone who’s always felt uncomfortable in social situations and who has a difficult time dealing with ambiguity of any sort. Michael is finding this particular life stage extremely stressful.

Always nervous to venture into unchartered territory, Michael has lived at home during college and hasn’t developed much of a social network as a young adult. In regard to romance—forget it—Michael, who is sure of his heterosexuality, has never been with a woman in an intimate way.

Michael’s parents are encouraging him to move out on his own, to start a career, and to go ahead and make something of himself. Michael hasn’t the foggiest idea where to start—the stress of the situation has led him to finally seek out therapy for guidance.

Several fields of psychotherapy have been honed over the past several decades to address Michael’s issues, and there is clearly some merit to the different approaches that are out there. A cognitive behavioristically trained therapist might get Michael to develop a list of specific stimuli that make him feel stressed and develop responses to these stimuli that are incompatible with stress. A humanistic therapist might work with Michael over several sessions, getting him to develop a self-identity that is positive and optimistic in scope. A psychoanalyst trained in the Freudian tradition might work with Michael to delve deeply into his past to find how early experiences with his parents are at the core of his current state of stress. The point of this section is not to disparage existing approaches to therapy—when done with high-quality training, existing approaches can have positive effects.11 Rather, the point here is to present the fresh angle on therapy offered by an approach that’s informed by evolutionary psychology—and rooted in the ideas of mating intelligence.

A therapist taking the mating intelligence approach considers Michael’s situation in evolutionary context. Michael is a young adult male. He exists because his ancestors possessed a battery of adaptations that facilitated reproductive success. Ultimately, Michael is stressed out by the lack of mating success to this point. He has yet to succeed in the following mating-relevant domains:

• Courtship

• Infatuation

• Love

• Foreplay

• Copulation

• Dating

• Having someone commit to being with him for the long-term

Not only has Michael failed as of yet to succeed in these clearly relevant mating domains, but he also has yet to succeed in many crucial life domains that surround mating.

• Become a core member of an all-male coalition

• Develop a reliable and broad social network beyond his kin network

• Dazzle anyone—demonstrating some outstanding abilities in some behavioral area (e.g., artistic ability, musical ability, oratory skills)

• Develop an opportunity to demonstrate to others that he is a kind, other-oriented, good soul

That’s okay—Michael’s 22—he’s young yet! Michael’s highly skilled and evolutionarily oriented therapist sees the problem and the solution. She realizes that stress responses are usually not a mark of psychopathology. Rather, Michael’s stress response here seems like an adaptive response to a situation that is evolutionarily threatening. From this perspective, the human emotion system was shaped by millennia of selection forces to send signals to individuals when it would be adaptive to alter their situations.12 Male ancestors of Michael who were in circumstances similar to his but who were perfectly content in such circumstances likely failed to reproduce, and failed to pass on genes coding for a lack of emotional reactivity during mating-shutout conditions.

To become less stressed about his lot, Michael needs to take steps that will increase mating prospects. Increasing the cognitive skills that underlie the mating domain should go a long way toward helping Michael in his situation.

Michael needs to develop some kind of courtship-display abilities by demonstrating expertise in some area. As shown earlier in this book and in other recent books,13 courtship display in humans can take many forms. Michael did well as a history student in college. He can join one of the many history-related social groups out there—demonstrating his skills to interested others—and expand his social group, an outcome that always correlates positively with mating-relevant outcomes. Michael also can work on his personality. He can work on his humor, work on his social skills, work on things that will make him more exciting and interesting to potential mates.

Thinking about Michael’s situation in terms of mating intelligence has two beneficial qualities. First, this approach places Michael and his emotional state squarely in an evolutionary context, allowing the light of evolutionary theory, which sheds on phenomena across all academic areas,14 to illuminate Michael’s world and possible futures. Further, mating intelligence theory has a clear set of concepts, such as mental courtship display, attractive personality traits, and optimistic attitudes about oneself, that provide a clear toolbox for a therapist working with clients across demographic groups. To the extent that mating is relevant to an individual (and it always is), mating intelligence theory provides a useful set of solutions. Just ask Michael, whose future could hold in store presidency of the Podunk Historical Society and a happy marriage to another quirky history buff!

In this chapter, we are exploring the ways mating intelligence theory can be used to solve practical social and personal problems. Here, we discuss six broad-scale societal problems that can be informed by mating intelligence. Specifically, we’ll focus on:

1. Violence toward women

2. Hooking-up miscommunication

3. Runaway spending

4. Young male syndrome15

5. Social class and mortality

6. Educational disparities

The literature in evolutionary psychology is clear: violence toward women is a subset of relational and familial violence, the most species-typical form of human violence, and one that can be illuminated with an understanding of evolutionary psychology.

The most common forms of violence toward women are highly related to mating, including reactions to suspected infidelity,16 reactions to relationship breakups,17 reactions to the withholding of sex within the confines of an intimate relationship,18 and reactions that take place when paternity is in question.19 Violence toward women is related to our evolutionary heritage. Understanding our evolutionary origins, thus, holds a key to helping solve this important social problem.

High mating intelligence is partly characterized as accurately knowing the mating psychology of the opposite sex. Helping individuals of both genders to increase this skill will help them better empathize with members of the other sex. Sexual harassment and aggression, both core elements of violence toward women, are seen as stressful by both sexes—but males consistently underestimate how costly such actions are in the eyes of women.20 Increasing awareness of this kind of issue (through such programs as the health education initiative, outlined in a prior section of this chapter) should help males to become better able to empathize with female psychology and less likely to engage in violent acts toward women.

High levels of mating intelligence correspond to high levels of empathy toward the opposite sex. We predict that future research will demonstrate that males high in mating intelligence are less likely to engage in sexually harassing behaviors, less likely to rape women, and less likely to engage in violence toward women. This prediction rests on two ideas. First, males high in mating intelligence should, by definition, empathize with women better than other males do. Second, being high in mating intelligence is attractive. As such, men high in mating intelligence should more easily start relationships with women and should find relationships relatively smooth—thus facing less mating-relevant conflict compared with men who are low in mating intelligence.

Imagine a guy who is out on the dating scene armed with a clear awareness of the evolutionary psychology of sex differences in sexual harassment. And, as a bonus, he’s been educated both implicitly and explicitly on the importance of keeping a reputation as a good, helpful guy who’s always a plus in the community. Now picture him out on a date with a woman who’s just not as interested in the same things he is interested in. Armed with his education on issues tied to mating, and resultant high mating intelligence, he’s going to be much more likely to treat her respectfully and move on compared with a similar guy who just doesn’t have the skills or education in this area.

Further, in terms of courtship signaling, mating intelligence theory tells us that behaviors that reveal relatively high levels of creativity and particularly high levels of other-oriented behavior are attractive to potential mates. Although aggression and violence do have their attractive sides under some rare mating contexts,21 creative, funny, and kind eventually win the race (see Chapter 8).

Increasing awareness of these facts may well go a long way toward reducing a culture of violence. Educational programs such as the health education program described earlier have potential to educate adolescents on these issues early in their mating-relevant years. Increasing mating intelligence in such individuals early on should serve as a key to reducing so many social problems, such as violence toward women, that have issues of human mating at their core.

Human mating operates on a continuum, from “hook-ups” and “booty-calls” on one end22 to “open relationships” and committed sexual relationships on the other. Hooking-up behaviors, in particular, have become widespread across college campuses throughout North America, replacing the traditional “dating scene” of prior generations.23 Studies show that 65% to 80% of undergraduates report engaging in hook-up behaviors at least once in their college careers.24 What is causing such an increase?

Garcia and Reiber25 make a compelling case that pluralistic ignorance (PI) plays an important role. PI happens when people behave in accordance with perceived beliefs about their own groups while ignoring their own beliefs. Unfortunately, PI can lead people to act in ways that they aren’t really comfortable with. To test how PI may play a role in the prevalence of hook-up behaviors, Garcia and Reiber administered a variety of survey questions to 507 undergraduate students (55% female, 45% male) at a mid-sized public university. They found that 81% of their participants reported having engaged in some form of sexual hook-up behavior, and consistent with prior research, men reported higher comfort levels engaging in all sexual behaviors compared with women. Men also overestimated women’s comfort levels with oral sex and intercourse, behaviors that potentially pose higher physical and mental health risks, such as STDs, unintended pregnancy, and psychological injury.

The researchers also found PI effects. For all sexual behaviors, both genders attributed to others of the same gender higher comfort levels than they, themselves, felt. Although women reported moderate discomfort with intercourse during a hook-up, 32% of women and 35% of men reported having engaged in intercourse during a hook-up. Over one third of the women reported engaging in oral sex even though their comfort levels were generally negative about engaging in this act. The researchers suggest that:

The pressure to act in accordance with these false perceived norms may be leading people to engage in behaviors in which they are uncomfortable, a state of affairs that poses potential risks in terms of sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy, and psychological trauma. (Garcia & Reiber, 2010, p. 399)

As the researchers note, these three factors—men’s higher comfort, men’s overestimation of women’s comfort, and women’s overestimation of other women’s comfort—may work together and increase the chances for sexual assault. As we discussed in Chapter 6, men in general tend to overperceive a women’s sexual intent. This effect, paired with the PI effect, can lead to dangerous sexual activity in which partners have differing and misinformed perceptions of their engagement.

Women also were found to attribute higher comfort levels to other women than they themselves felt. This suggests that women were viewing other women as competitors for mates and is consistent with Garcia and Reiber’s earlier study,26 which found that more than half of both men and women did not hold out any expectations that the hook-up would lead to a relationship, whereas 51% of men and women reported that the desire to engage in a relationship did motivate their choice to engage in a hook-up. Clearly, individual differences play a role here. “String-free” hooking up may not be as string free for everyone.

So, what can be done to reduce potential for misunderstanding between men and women? Garcia and Reiber suggest adopting social norms marketing—or the idea that people can benefit from knowing what other people really do (as opposed to what they are led to think that others do by media and other biased forms of communication). Such techniques have been useful in dealing with alcohol use on campuses. The authors propose applying the same technique to hook-up behaviors by continuing to survey trends on an ongoing basis and developing and implementing an educational campaign that, in collaboration with the campus counseling center, the student life office, and the student health service, will disseminate accurate information about hook-up attitudes and behavior on campus. It is hoped that such techniques will prove useful in reducing negative outcomes. We think their conclusion is very sensible and worthy:

We neither condemn nor condone sexual activity, but rather, we endorse the need for young adults to be aware of, honestly communicate, and act in accordance with, their own comfort levels and those of their partner(s) during engagement in sexual activity. (Garcia & Reiber, 2010 p. 401)

In case you haven’t noticed, the United States has a problem. People spend more than they can afford. This trend has increased rapidly in the past few decades and has come to a head with the recent mortgage meltdown that has ravaged our nation’s economy.

Budgeting is really not that complicated. If someone has $100 and a pair of shoes costs $120 plus tax—the shoes are out of budget. But given the full range of personal finance in modern societies (such as credit cards), this simple reasoning is lost on millions. The lifeblood of the financial credit industry, which is foundational in countries such as the United States, is helping people purchase things they cannot afford. In fact, to own a house, purchasing something that you cannot afford is usually the only possible means.

Spending more than you can afford allows you to appear to have all kinds of qualities that you may not actually have. In a recent study on the evolutionary psychology of credit card debt, Kruger27 found that, controlling for income levels, males who were more likely to overspend and build up balances that they could not afford were more likely than other males to have multiple sex partners. Overspending may act as a false signal of wealth, and although it is a false signal, sometimes this deception is effective. In fact, given how core deception is in human mating, it seems clear that overspending has become a modern form of false signaling, or mating deception.

In his recent book on the evolutionary psychology of modern spending patterns and consumerism, Spent, Geoffrey Miller28 argues that modern-day materialism is the result of runaway selection and false courtship signaling. If every other guy is driving a Mercedes and I’m on a scooter, I must not have something that they all have. And the “thing” that they all “have” may be more than just a better vehicle. In making social judgments of others, we infer all kinds of things from people’s belongings. We infer personality traits, social status, familial background, and intelligence levels, and ultimately, Miller argues, we unconsciously infer genetic quality. And this analysis is fully consistent with Gad Saad and John Vongas’s29 analysis of young adult males whose testosterone levels increase as a function of driving a Porsche downtown.

According to Robert Frank,30 people also seem to spend a lot of money on positional goods, goods that have little utilitarian impact on survival but that signal our relative position in our local social circle. How many square feet is your house? Oh, you live on how many acres? How many cars fit in your garage? What kind of wood is your deck made out of? Which landscape company did your landscaping? Granite counters, of course, I assume?

Sound like a conversation you might have in modern America?

It truly is nicer to chop onions on a granite counter than on a laminate counter. But let us ask you this: Don’t you chop your onions on a cutting board anyway? Oh, did you get that cutting board from France when you were in Europe? … but we digress.

Positional goods abound. The proportion of money that Americans spend on positional goods so as to (usually unconsciously) keep up with or beat out the Joneses is in the billions of dollars each year.31 Welcome to America.

Using the evolutionary perspective on mating, spending is a form of courtship signaling. Not rich? But want to appear rich to potential mates? Get a credit card! (And watch MTV to know what to wear.) Then go to the mall with a smile and inhibit your mathematical skills.

But mating does not end after courtship. And mating does not end after the initial formation of a long-term mateship. We’re pretty monogamous as a species (see Chapter 3).

As relationships progress toward long-term mateship, there are still plenty of bad reasons to spend money on stuff you don’t need. For the sake of your relationship and your family, you may find yourself spending money on items that, on superficial reflection, are luxuries—commodities that come with mating-relevant signals. Yes, the kids each have their own Nintendo DSi. Yes, they each have two pairs of Crocs. Of course the boy has a Star Wars lunchbox—and we might get a separate one for the little one’s snacks. Oh, we don’t mind you asking at all, the paved driveway cost $6,000—but you know he went with the best pavers in town. Positional goods. A high proportion of our dialog with one another is all about positional goods.

Working to keep your status at levels that are acceptable or above seems a basic part of human nature.32 And any mating psychologist will tell you that status and mating success are inextricably linked.

But as Geoffrey Miller tells us, even though commodities that signal quality and status of individuals do serve mating functions, these signals are often false signals. And someone with high mating intelligence should be better able than others to pick this out. Sure, Joe may have a BMW, but this is not because he’s a higher-quality person than Tom (who drives a Kia). In fact, they make the same salary. Joe is simply more willing to utilize false signaling in his courtship strategy compared with Tom. Oh, that’s not really very attractive when you put it that way!

An understanding of mating intelligence has a lot to offer in our attempts to understand broad spending patterns, especially in modern societies. And high levels of mating intelligence should go a long way in helping people tease apart genuine from false courtship signals.

One of the largest, most socially relevant, and thought-provoking areas of research to be illuminated by modern evolutionary psychology context pertains to male-female differences in the domain of death and injury. Think that evolutionary psychology somehow presents a biased view of the social world that favors men? Apparently, a lot of people do hold this opinion.33 Well, think again. First off, evolutionary psychology is a scientific explanatory framework, rather than a moral code replete with oughts.34 Regardless, even the most cursory look at the research on sex differences in injury and death paint a clear picture that is not particularly warming to hearts of men like ourselves.

In short, compared with females, males are more likely to:

• Die as a result of spontaneous abortion in utero35

• Die of some accident in the first year of life36

• Die of an accident in childhood—including falling, bicycle accidents, and even automobile accidents37

• Die of a wound as a function of a physical altercation38

• Die as a result of adverse effects of drugs and alcohol misuse39

• Die during midlife at the hands of other males during postmarriage reentry into the mating market40

• Suffer injuries during childhood that are likely to lead to concussion, stitches, casts, and hospital visits41

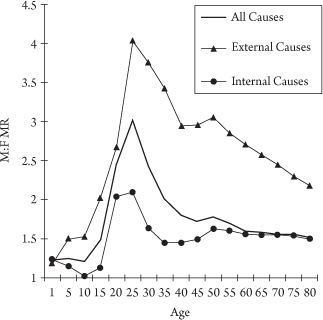

Is this portrait of a relatively difficult male world not clear enough? Then you should consider the fact that in virtually every culture that’s ever been studied, males have significantly lower life expectancies than females. Further, consider the male-to-female mortality ratio. This ratio (see Fig. 9.1) speaks to how much more likely males are to die (at a given age) than females (of that same age group). If the male-to-female mortality ratio = 1.0, that means that the proportion of males who die at a given age in life equals the proportion for females. As the number increases (e.g., male-to-female mortality ratio = 2.0), males are more likely than females to die at a particular life stage.

Figure 9.1: 2001 U.S. male-to-female mortality ratio for all causes, external causes, and internal causes of death. (Kruger & Nesse, 2007).

In a series of high-profile studies on this topic, Dan Kruger and Randolph Nesse42 have documented that the male-to-female mortality ratio is particularly pronounced between the ages of 15 and 25 years, the years that largely correspond to courtship in our species. Humans are animals, and mate selection is competitive. Further, standard evolutionary biology tells us that if one sex invests a lot into parenting relative to the other sex, that high-investing sex will become relatively choosy in mate selection, and members of the other sex will compete more fiercely for access to mates. In humans, females invest more in offspring, females are more discriminating when it comes to mating,43 and men compete fiercely with one another for access to mates.

We may think that this idea of males competing fiercely with one another characterizes nature documentaries (imagine two bull elk with antlers right about … now …) or non-Western societies, such as the Yanomami of South America, where males engage in public fights trying to injure or kill their opponents with clubs or spears. Yeah, that’s fierce. But head to an emergency room in any North American city late on a Saturday night, and you’ll see that we’re not much different than the Yanomami culture. The proportion of physical injuries as a result of competitive fights at bars and parties is extremely sex biased, with young adult males much more likely than young adult females to show up at the emergency room after a scuffle, often over status or a woman, or something that likely ultimately relates to status or a woman.

Maria Peclet and colleagues44 conducted an analysis of sex differences in injuries in children in a sample of 3,472 cases of Massachusetts residents over a 34-month period. All the individuals in this sample were children. Injuries were coded in terms of several categories—injuries from a fall, automobile crash, and so forth. The sex bias, which parallels the trend found across studies of this kind, is clear. More than 60% of injuries documented were found in boys.

That’s the world we live in—injury and death are integrally tied to whether one is male or female. And an evolutionarily informed perspective tells us why. From our perspective, understanding our behavior in evolutionary context by understanding why injury and death are so strongly connected to biological sex can help reduce risks for premature death and injury from accidents. Understanding our evolutionary roots—and the nature of human mating intelligence and where it comes from—may well help us understand issues such as injury rates in terms of their ultimate causes, thereby allowing us to create better informed solutions to the problems that permeate society.

Throughout this book, we have discussed the important effects of context on mating behaviors (see Chapter 3). Evolutionary psychology and behavioral ecology offer us new ways of understanding and explaining behavioral patterns seen in conditions of low socioeconomic status.45 The combination of these approaches allows us to nonjudgmentally understand the cause of behaviors of people all around the world living under different conditions. The main tenet of behavioral ecology is that all animals exhibit the potential for behavioral flexibility and they use this flexibility to do the best they can in terms of survival and reproductive success given the context in which they find themselves.46

Behavioral ecology has proved quite useful in explaining human behavior. Humans behave very differently depending on their socioeconomic status. To make sense of why people behave the way they do, it’s important to take into account factors that differ widely from one environment to the next. As we mentioned in Chapter 3, one major factor associated with socioeconomic status is the rate of mortality present in the environment. Mortality rates differ quite a bit from one neighborhood to the next and have a dramatic impact on people’s life expectancy.

As one demonstration of this, Madhavi Bajekal,47 head of the United Kingdom government’s Morbidity and Healthcare team, looked at all of the electoral wards in Britain and assessed the relationship between the length of time expected to be alive and healthy and the level of social deprivation. The difference in life expectancy between the most deprived areas of Britain and the least deprived areas is as much as two decades (50 vs. 70 years)!

Such differences in life expectancy can have dramatic effects on people’s psychology and behavior. Daniel Nettle48 examined 8,660 families in Britain and found that in the most deprived neighborhoods, the age at first birth is younger, birth weights are lower, and breastfeeding duration is shorter than in the most affluent neighborhoods. In the poorest areas, women have babies at about the age of 20 years, compared with the age of 30 years in the richest areas. There is also indirect evidence that reproductive rates are higher in the poorest areas. In other words, when people expect to die young, they live fast, adopting a fast life history strategy (see Chapter 3).

This pattern is not just found in Britain. Across a set of small-scale subsistence societies, one study49 found that for every 10% decline in the infant survival rate, there is a 1-year decrease in mothers’ age at first birth, whereas another study50 found that all across the world, the shorter the life expectancy, the earlier women reproduced. This pattern holds not just among humans but also across a large number of mammalian species.51 Both within humans and across species, we tend to find that the higher the mortality rate, the earlier the onset of sexual reproduction in females and among males, the higher the mating effort and male-male competition.

Looking through a mating intelligence lens, informed by evolutionary psychology and behavioral ecology, we can start to make sense of these behaviors. When mortality is low, it would be evolutionarily adaptive for a female to have a small number of offspring and invest in each one. But in ecologies where mortality is high, that same strategy would leave the female with a high probability of having no offspring at all surviving to adulthood. Indeed, Arline Geronimus52 found in Harlem, New York that the infant mortality rate of babies born to teenagers is half as great as the infant mortality rate of babies born to mothers in their 20s. Of course, the term adaptive as used here does not necessarily mean the same thing as socially desirable. Adaptive strictly refers to the likelihood that certain (conscious or unconscious) behaviors maximize survival and reproductive success. Still, the evolutionary approach allows us to explain widespread behavioral patterns that might seem random.

In general, the behavioral ecology approach views low socioeconomic behaviors as adaptive within harsh and unpredictable environments.53 This approach can explain seeming puzzles, such as why those living in harsh and unpredictable environments, who have the most need to take care of themselves, are the least likely to do so.54 Some of the evolutionary predictions made by behavioral ecologies even go against common intuition. For instance, one might think that low birth weight or early life stress would cause females’ reproductive development to slow down, but instead these factors actually speed up women’s sexual development (see Chapter 3).

Although mortality is a major determinant of the harshness of an environment, there are different types of mortality. Behavioral ecologists differentiate between extrinsic and intrinsic mortality. Extrinsic forms of mortality, such as the level of pollution in the air, is relatively unaffected by people’s behavior. Intrinsic mortality, on the other hand, is affected by people’s decisions, such as ignoring medical advice or choosing foods with poor nutrition. People can make a choice to reduce intrinsic mortality by trying to take care of themselves, but making that choice is a form of investment that takes up time and energy, an investment some people living in harsh environments may not view as worth it. Indeed, as the rate of extrinsic mortality goes up, the return in the investment of taking care of one’s health does go down.55 As Nettle notes,

Who would spend money on regularly servicing a car in an environment where most cars were stolen each year anyway? (2009b, p. 936)

Still, we remain optimistic that we can use our understanding of the deep evolutionary logic of these behaviors to influence public policy and have a real effect on the well-being of those living in the harshest of environments. Certainly, epidemiologists have done a remarkable job describing the extent to which separate behaviors, such as sexual behavior, drugs, and violence, are related to the total rate of mortality in a society. A major limitation of their approach, however, is that they tend to treat these behaviors as unrelated. The evolutionary perspective suggests instead that these behaviors cluster together in non-random ways for evolutionarily adaptive reasons.

Neither biology nor environmental circumstances are destiny. But that does not mean change is going to be easy. Many factors at many different levels play a crucial role in shaping the fast life. A person’s individual traits and the family, neighborhood, peers, and norms of conduct of that society each play crucial roles. To make large-scale changes you can’t just change one particular trait, behavior, or aspect of the environment. Large-scale changes will require large-scale interventions that address many aspects of the system at once. A lot needs to happen in the harshest of environments to convince people and their genes that investing in their health will have a long-term payoff. As Nettle notes,

We should not be surprised that social gradients in diet, breast-feeding or teenage pregnancy have failed to diminish, since the underlying inequality of our society has not diminished either…. Actually reducing poverty in the most deprived areas is far more likely to be influential than superficial education or awareness-raising schemes. (2009b, p. 937)

Against this advice, the U.K. government attempted to reduce the teenage pregnancy rate by educating young people about reproduction and contraception.56 These programs have shown to be ineffective. From an evolutionary perspective, ignorance is not the issue. In fact, it may be ignorant for educators to think ignorance is the issue! Younger women in low socioeconomic status areas tend to reproduce at younger ages owing to the circumstances of their environment. In fact, they are actually taking an informed risk based on their life expectancy. As social scientist Lisa Arai at the University of London argued,

… policymakers find it hard to believe that young women, often in the least auspicious circumstances, might actually want to be mothers (Arai, 2003, p. 212).

As another example, many social interventionists think that adding basketball courts in low-socioeconomic neighborhoods will help redirect aggressive energies into friendly neighborhood games. The thinking is that by diverting such energies away from gang-related violence to cooperative play, gang violence will dissipate. This approach has failed. Increasing the basketball efficiency of inner-city youths has had no observable effect on the rate of violent crime.57 Changing more than just one aspect of the interconnected web of life history factors is required.

Significant changes are possible, though. For example, the royalties that came from building a casino in a poor U.S. neighborhood led to an unexpected reduction in psychopathology and antisocial behaviors.58 Additionally, there was a considerable decline in teenage birth rates in the United States in the 1990s, particularly among African Americans, which was probably owing to a better economy and increase in employment opportunities for black women during this time.59 As the New Scientist reports, however, teen birth rates among African Americans are rising again, most likely a result of the relatively recent economic decline.

There is tremendous potential for the behavioral ecology perspective to inform public policy, but we agree with Nettle60 that there is a great need for social scientists and evolutionary theorists to unite in a common cause and go beyond misconceptions about what it really means for something to have an evolutionary basis: “evolved” is not the opposite of “learned,” and “evolutionary causes” are not the opposite of “social causes.” As Nettle eloquently wrote,

Evolutionary thinking in the human sciences is nothing more or less than the holistic, integrative understanding that we, like other animals, respond to our social and developmental environment in non-arbitrary ways. (2009b, p. 937)

We see opportunity for the mating intelligence perspective to be integrated with educational psychology, particularly when it comes to developing creativity. The mating intelligence framework, informed by life history theory, gives us greater insight into the mechanisms by which students adapt to their environments inside and outside the classroom. Many students with extraordinary potential for making socially valuable contributions see their potential squandered because their energies are directed toward other concerns involving survival and reproduction.

Note that although life history strategy is directly related to brain-based executive functions that may get in the way of school performance (e.g., emotional regulation skills), life history strategy is not directly related to IQ. The processes evoked when taking an IQ test are related but are not exactly the same as the processes evoked on tests of executive functioning, and not all executive functions are equally related to intelligence.61 Life history strategy is less directly tied to IQ and more related to the self-control and emotional self-regulation executive functions, skills that have a significant impact in a classroom environment.62 It is important to keep in mind that fast life strategists are not stupid. In fact, if you define intelligence as the ability to adapt to the environment (as many intelligence researchers define the term), then fast-life strategists are, in certain environments, very intelligent from an evolutionary perspective.

Many fast-life strategists are reprimanded in school for displaying social problems that are adaptive in their environment outside the classroom but may not be adaptive inside the classroom. Indeed, Robert J. Sternberg has long-argued that “practical intelligence” is a form of intelligence just as important as the type of analytical skills measured by IQ tests.63

Although intelligence theorists rarely peer through an evolutionary lens (a state of affairs we find unfortunate), we think that looking at the entire suite of human strategies from an evolutionarily informed perspective offers potential for helping teachers better understand the evolutionary logic behind many of the traits and behaviors they see in their classrooms. We think teachers may get more out of their students by really getting into their students’ heads and attempting to understand the evolutionary logic behind many of their students’ classroom behaviors. Such an understanding can potentially help students boost their self-regulation skills64 and channel their life history strategies toward socially acceptable creative and productive pursuits, which in the long run is conducive to mating success much more so than aggression and dominance.

In our view, there is no need to throw out the baby with the bathwater; some fast life traits such as risk-taking, questioning of authority, and rebelliousness can be quite conducive to creativity. Don’t we want to teach our students to question authority, and not blindly follow other people’s rules? Unfortunately, most displays of creativity and spontaneity are not highly valued in most classrooms—even though recent research has found that creative activities improve the brain’s ability to process information.65

Thankfully, there’s some exciting work being done looking at education from an evolutionarily informed perspective. We highly recommend checking out Peter Gray’s work on the topic.66 At the end of the day, the key to dealing with life’s many demands seems to be the ability to strategically activate or deactivate executive functions depending on the context. This kind of flexibility is not taught in schools, but why not?

Another key to educating those in the fast lane is to convince them that there is a reason for them to invest in creativity—that their investments will pay off. Many living the fast life really do perceive their future as dire. The life history framework predicts that in order to have long-lasting changes on students who are living the fast life, you have to change their harsh and unpredictable contexts. This is the most likely way their strategies will change from seeking short-term gains to seeing a purpose for longer-term planning (see previous section).

Although the mating intelligence perspective, informed by life history theory, certainly does not explain everything, we think there is a lot of untapped potential to inform educational structure and practices. Many students may not be well adapted to a structured classroom environment, but that does not mean they cannot harness their particular way of thinking and behaving in a way that that is highly innovative as well as socially and culturally valued.

Throughout this book, we have presented the new idea of mating intelligence. Rooted in an evolutionary perspective on human nature, Mating Intelligence Theory has the capacity to illuminate many areas of human life. Both inside and outside the walls of academia, scholars are often asked how their ideas are useful. What are the practical applications? How can this all benefit society? Why should I care?

In this chapter, we discussed several ways that mating intelligence has the capacity to help people at the individual and societal levels. The sex education approach described here has the capacity to help educate adolescents by putting sexuality in the contexts of society and human evolution. This approach, rooted in the core ideas of Mating Intelligence Theory, has potential to help young adults better understand why sexuality is so central to human social behaviors and how to make informed, adaptive, and other-oriented decisions regarding sex.

The applications to psychotherapy described in this chapter have the capacity to revolutionize psychotherapy writ large. Whether people like it or not, evolutionary psychology is seeping into all aspects of the behavioral sciences.67 Evolutionary psychology is shedding light on all aspects of humanity as a result. Using the insights of evolutionary psychology to inform approaches to psychotherapy seems, to us, to be the only reasonable way for therapists to progress in their efforts to help others. Mating Intelligence Theory is a specific set of ideas, informed both by evolutionary psychology and individual differences research on intelligence and personality, with the potential to help therapists get to core issues of human mating that lead to such psychological issues as stress and depression.

This chapter also addressed the major societal problems of violence toward women, runaway spending, male injury, mortality, and implications of mating intelligence in the classroom. Future work in the area of applied psychology will benefit from the insights of Mating Intelligence Theory as social scientists and policy makers battle these important social issues.

Life is not easy. And mating is not easy. An understanding of mating intelligence, the cognitive processes that underlie human mating, can help.