Chapter 6. Java’s Approach to Memory and Concurrency

This chapter is an introduction to the handling of concurrency (multithreading) and memory in the Java platform. These topics are inherently intertwined, so it makes sense to treat them together. We will cover:

-

Introduction to Java’s memory management

-

The basic mark-and-sweep Garbage Collection (GC) algorithm

-

How the HotSpot JVM optimizes GC according to the lifetime of the object

-

Java’s concurrency primitives

-

Data visibility and mutability

Basic Concepts of Java Memory Management

In Java, the memory occupied by an object is automatically reclaimed

when the object is no longer needed. This is done through a process

known as garbage collection (or automatic memory management). Garbage

collection is a technique that has been around for years in languages

such as Lisp. It takes some getting used to for programmers accustomed

to languages such as C and C++, in which you must call the free()

function or the delete operator to reclaim memory.

Note

The fact that you don’t need to remember to destroy every object you create is one of the features that makes Java a pleasant language to work with. It is also one of the features that makes programs written in Java less prone to bugs than those written in languages that don’t support automatic garbage collection.

Different VM implementations handle garbage collection in different ways, and the specifications do not impose very stringent restrictions on how GC must be implemented. Later in this chapter, we will discuss the HotSpot JVM (which is the basis of both the Oracle and OpenJDK implementations of Java). Although this is not the only JVM that you may encounter, it is the most common among server-side deployments, and provides a good example of a modern production JVM.

Memory Leaks in Java

The fact that Java supports garbage collection dramatically reduces the incidence of memory leaks. A memory leak occurs when memory is allocated and never reclaimed. At first glance, it might seem that garbage collection prevents all memory leaks because it reclaims all unused objects.

A memory leak can still occur in Java, however, if a valid (but unused) reference to an unused object is left hanging around. For example, when a method runs for a long time (or forever), the local variables in that method can retain object references much longer than they are actually required. The following code illustrates:

publicstaticvoidmain(Stringargs[]){intbigArray[]=newint[100000];// Do some computations with bigArray and get a result.intresult=compute(bigArray);// We no longer need bigArray. It will get garbage collected when// there are no more references to it. Because bigArray is a local// variable, it refers to the array until this method returns. But// this method doesn't return. So we've got to explicitly get rid// of the reference ourselves, so the garbage collector knows it can// reclaim the array.bigArray=null;// Loop forever, handling the user's inputfor(;;)handle_input(result);}

Memory leaks can also occur when you use a HashMap or similar data

structure to associate one object with another. Even when neither

object is required anymore, the association remains in the hash table,

preventing the objects from being reclaimed until the hash table itself

is reclaimed. If the hash table has a substantially longer lifetime than

the objects it holds, this can cause memory leaks.

Introducing Mark-and-Sweep

To explain a basic form of the mark-and-sweep algorithm that appears in the JVM, let’s assume that there are two basic data structures that the JVM maintains. These are:

- Allocation table

-

Stores references to all objects (and arrays) that have been allocated and not yet collected

- Free list

-

Holds a list of blocks of memory that are free and available for allocation

Note

This is a simplified mental model that is purely intended to help the newcomer start thinking about garbage collection. Real production collectors actually work somewhat differently.

With these definitions it is now obvious when GC must occur; it is required when a Java thread tries to allocate an object (via the new operator) and the free list does not contain a block of sufficient size.

Also note that the JVM keeps track of type information about all allocations and so can figure out which local variables in each stack frame refer to which objects and arrays in the heap.

By following references held by objects and arrays in the heap, the JVM can trace through and find all objects and arrays are still referred to, no matter how indirectly.

Thus, the runtime is able to determine when an allocated object is no longer referred to by any other active object or variable. When the interpreter finds such an object, it knows it can safely reclaim the object’s memory and does so. Note that the garbage collector can also detect and reclaim cycles of objects that refer to each other, but are not referenced by any other active objects.

We define a reachable object to be an object that can be reached by starting from some local variable in one of the methods in the stack trace of some application thread, and following references until we reach the object. Objects of this type are also said to be live.1

Note

There are a couple other possibilities for where the chain of references can start, apart from local variables. The general name for the root of a reference chain leading to a reachable object is a GC root.

With these simple definitions, let’s look at a simple method for performing garbage collection based on these principles.

The Basic Mark-and-Sweep Algorithm

The usual (and simplest) algorithm for the collection process is called mark-and-sweep. This occurs in three phases:

-

Iterate through the allocation table, marking each object as dead.

-

Starting from the local variables that point into the heap, follow all references from all objects we reach. Every time we reach an object or array we haven’t seen yet, mark it as live. Keep going until we’ve fully explored all references we can reach from the local variables.

-

Sweep across the allocation table again. For each object not marked as live, reclaim the memory in heap and place it back on the free list. Remove the object from the allocation table.

Note

The form of mark-and-sweep just outlined is the usual simplest theoretical form of the algorithm. As we will see in the following sections, real garbage collectors do more work than this. Instead, this description is grounded in basic theory and is designed for easy understanding.

As all objects are allocated from the allocation table, GC will trigger before the heap gets full. In this description of mark-and-sweep, GC requires exclusive access to the entire heap. This is because application code is constantly running, creating, and changing objects, which could corrupt the results.

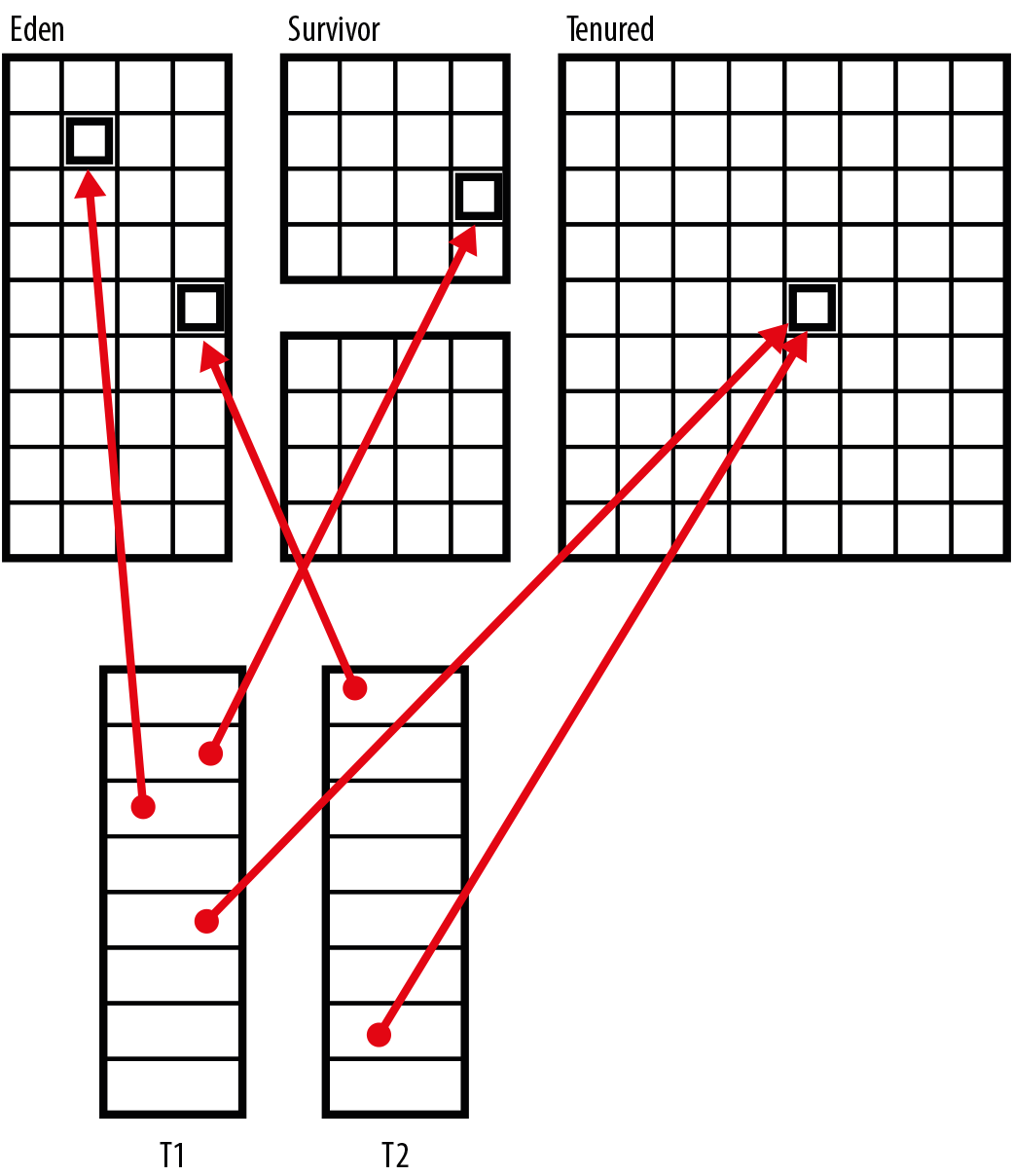

In a real JVM, there will very likely be different areas of heap memory and real programs will make use of all of them in normal operation. In Figure 6-1 we show a typical layout of the heap, with two threads (T1 and T2) holding references that point into the heap.

Figure 6-1. Heap structure

This shows that it would be dangerous to move objects that application threads have references to while the program is running.

To avoid this, a simple GC like the one just shown will cause a stop-the-world (STW) pause when it runs—because all application threads are stopped, then GC occurs, and finally application threads are started up again. The runtime takes care of this by halting application threads as they reach a safepoint—for example, the start of a loop or just before a method call. At these execution points, the runtime knows that it can stop an application thread without a problem.

These pauses sometimes worry developers, but for most mainstream usages, Java is running on top of an operating system that is constantly swapping processes on and off processor cores, so this slight additional stoppage is usually not a concern. In the HotSpot case, a large amount of work has been done to optimize GC and to reduce STW times, for those cases where it is important to an application’s workload. We will discuss some of those optimizations in the next section.

How the JVM Optimizes Garbage Collection

The weak generational hypothesis (WGH) is a great example of one of the runtime facts about software that we introduced in Chapter 1. Simply put, it is that objects tend to have one of a small number of possible life expectancies (referred to as generations).

Usually objects are alive for a very short amount of time (sometimes called transient objects), and then become eligible for garbage collection. However, some small fraction of objects live for longer, and are destined to become part of the longer-term state of the program (sometimes referred to as the working set of the program). This can be seen in Figure 6-2 where we see volume of memory (or number of objects created) plotted against expected lifetime.

Figure 6-2. Weak generational hypothesis

This fact is not deducible from static analysis, and yet when we measure the runtime behavior of software, we see that it is broadly true across a wide range of workloads.

The HotSpot JVM has a garbage collection subsystem that is designed specifically to take advantage of the weak generational hypothesis, and in this section, we will discuss how these techniques apply to short-lived objects (which is the majority case). This discussion is directly applicable to HotSpot, but other server-class JVMs often employ similar or related techniques.

In its simplest form, a generational garbage collector is simply one that takes notice of the WGH. They take the position that some extra bookkeeping to monitor memory will be more than paid for by gains obtained by being friendly to the WGH. In the simplest forms of generational collector, there are usually just two generations—usually referred to as young and old generation.

Evacuation

In our original formulation of mark-and-sweep, during the cleanup phase, we reclaimed individual objects, and returned their space to the free list. However, if the WGH is true, and on any given GC cycle most objects are dead, then it may make sense to use an alternative approach to reclaiming space.

This works by dividing the heap up into separate memory spaces. Then, on each GC run, we locate only the live objects and move them to a different space, in a process called evacuation. Collectors that do this are referred to as evacuating collectors, and they have the property that the entire memory space can be wiped at the end of the collection, to be reused again and again.

Figure 6-3 shows an evacuating collector in action, with solid blocks representing surviving objects, and hatched boxes representing allocated, but now dead (and unreachable) objects.

Figure 6-3. Evacuating collectors

This is potentially much more efficient than the naive collection approach, because the dead objects are never touched. GC cycle length is proportional to the number of live objects, rather than the number of allocated objects. The only downside is slightly more bookkeeping—we have to pay the cost of copying the live objects, but this is almost always a very small price compared to the huge gains realized by evacuation strategies.

An alternative to an evacuating collector is a compacting collector. The chief defining feature of these is that at the end of the collection cycle, allocated memory (i.e., surviving objects) is arranged as a single contiguous area within the collected region.

The normal case is that all the surviving objects have been “shuffled up” within the memory pool (or region) usually to the start of the memory range and there is now a pointer indicating the start of empty space that is available for objects to be written into once application threads restart.

Compacting collectors will avoid memory fragmentation, but typically are much more expensive in terms of amount of CPU consumed than evacuating collectors. There are design trade-offs between the two algorithms (the details of which are beyond the scope of this book), but both techniques are used in production collectors in Java (and in many other programming languages).

Note

HotSpot manages the JVM heap itself, completely in user space, and does not need to perform system calls to allocate or free memory. The area where objects are initially created is usually called Eden or the Nursery, and most production JVMs (at least in the SE/EE space) will use an evacuating strategy when collecting Eden.

The use of an evacuating collector also allows the use of per-thread allocation. This means that each application thread can be given a contiguous chunk of memory (called a thread-local allocation buffer) for its exclusive use when allocating new objects. When new objects are allocated, this only involves bumping a pointer in the allocation buffer, an extremely cheap operation.

If an object is created just before a collection starts, then it will not have time to fulfill its purpose and die before the GC cycle starts. In a collector with only two generations, this short-lived object will be moved into the long-lived region, almost immediately die, and then stay there until the next full collection. As these are a lot less frequent (and typically a lot more expensive), this seems rather wasteful.

To mitigate this, HotSpot has a concept of a survivor space_an area that is used to house objects that have survived from previous collections of young objects. A surviving object is copied by the evacuating collector between survivor spaces until a _tenuring threshold is reached, when the object will be promoted to the old generation.

A full discussion of survivor spaces and how to tune GC is outside the scope of this book. For production applications, specialist material should be consulted.

The HotSpot Heap

The HotSpot JVM is a relatively complex piece of code, made up of an interpreter and a just-in-time compiler, as well as a user-space memory management subsystem. It is composed of a mixture of C, C++, and a fairly large amount of platform-specific assembly code.

At this point, let’s summarize our description of the HotSpot heap, and recap its basic features. The Java heap is a contiguous block of memory, which is reserved at JVM startup, but only some of the heap is initially allocated to the various memory pools. As the application runs, memory pools are resized as needed. These resizes are performed by the GC subsystem.

When discussing garbage collectors, there is one other important terminology distinction that developers should know:

- Parallel collector

-

A garbage collector that uses multiple threads to perform collection

- Concurrent collector

-

A garbage collector that can run at the same time as application threads are still running

In the discussion so for, the collection algorithms we have been describing have implicitly all been parallel, but not concurrent, collectors.

Note

In modern approaches to GC there is a growing trend toward using partially concurrent algorithms. These types of algorithms are much more elaborate and computationally expensive than STW algorithms and involve trade-offs. However, they are believed to be a better path forward for today’s applications.

Not only that, but in Java version 8 and below, the heap has a simple structure: each memory pool (Eden, survivor spaces, and Tenured) is a contiguous block of memory. The default collector for these older versions is called Parallel. However, with the arrival of Java 9, a new collection algorithm known as G1 becomes the default.

The Garbage First collector (known as G1) is a new garbage collector that was developed during the life of Java 7 (with some preliminary work done in Java 6). It became production quality and officially fully supported with the release of Java 8 Update 40, and is the default from Java 9 onward (although other collectors are still available as an alternative).

Warning

G1 uses a different version of the algorithm in each Java version and there are some important differences in terms of performance and other behavior between versions. It is very important that, when upgrading from Java 8 to a latter version and adopting G1, you undertake a full performance retest.

G1 has a different heap layout and is an example of a region-based collector. A region is an area of memory (usually 1M in size, but larger heaps may have regions of 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32M in size) where all the objects belong to the same memory pool. However, in a regional collector, the different regions that make up a pool are not necessarily located next to each other in memory. This is unlike the Java 8 heap, where each pool is contiguous, although in both cases the entire heap remains contiguous.

G1 focuses its attention on regions that are mostly garbage, as they have the best free memory recovery. It is an evacuating collector, and does incremental compaction when evacuating individual regions.

G1 was orignally designed to take over from a previous collector, CMS, as the low-pause collector, and it allows the user to specify pause goals in terms of how long and how often to pause for when doing GC.

The JVM provides a command-line switch that controls how long the collector will aim to pause for: -XX:MaxGCPauseMillis=200.

This means that the default pause time goal is 200ms, but you can change this value depending on your needs.

There are, of course, limits to how far the collector can be pushed. Java GC is driven by the rate at which new memory is allocated, which can be highly unpredictable for many Java applications. This can limit G1’s ability to meet the user’s pause goals, and in practice, pause times under <100ms are hard to achieve reliably.

As noted, G1 was origially intended to be a replacement low-pause collector. However, the overall characteristics of its behavior have meant that it has actually evolved into a more general-purpose collector (which is why it has now become the default).

Note that the development of a new production-grade collector that is suitable for general use is not a quick process. In the next section, let’s move on to discuss the alternative collectors that are provided by HotSpot (including the parallel collector of Java 8).

Other Collectors

This section is completely HotSpot-specific, and a detailed treatment is outside the scope of the book, but it is worth knowing about the existence of alternate collectors. For non-HotSpot users, you should consult your JVM’s documentation to see what options may be available for you.

ParallelOld

By default, in Java 8 the collector for the old generation is a parallel (but not concurrent) mark-and-sweep collector. It seems, at first glance, to be similar to the collector used for the young generation. However, it differs in one very important respect: it is not an evacuating collector. Instead, the old generation is compacted when collection occurs. This is important so that the memory space does not become fragmented over the course of time.

The ParallelOld collector is very efficient, but it has two properties that make it less desirable for modern applications. It is:

-

Fully STW

-

Linear in pause time with the size of the heap

This means that once GC has started, it cannot be aborted early and the cycle must be allowed to finish.

As heap sizes increase, this makes ParallelOld a less attractive option than G1, which can keep a constant pause time regardless of heap size (assuming the allocation rate is manageable).

At the time of writing, G1 gives acceptable performance on a large majority of applications that previously used ParallelOld—and in many cases will perform better.

The ParallelOld collector is still available as of Java 11, for those (hopefully few) apps that still need it, but the direction of the platform is clear—and it is toward using G1 wherever possible.

Concurrent Mark-and-Sweep

The most widely used alternate collector in HotSpot is Concurrent Mark-and-Sweep (CMS). This collector is only used to collect the old generation—it is used in conjunction with a parallel collector that is responsible for cleaning up the young generation.

Note

CMS is designed for use only in low-pause applications, those that cannot deal with a stop-the-world pause of more than a few milliseconds. This is a surprisingly small class—very few applications outside of financial trading have a genuine need for this requirement.

CMS is a complex collector, and often difficult to tune effectively. It can be a very useful tool in the developer’s armory, but should not be deployed lightly or blindly. It has the following basic properties that you should be aware of, but a full discussion of CMS is beyond the scope of this book. Interested readers should consult specialist blogs and mailing lists (e.g., the “Friends of jClarity” mailing list quite often deals with GC-performance-related questions).

-

CMS only collects the old generation.

-

CMS runs alongside application threads for most of the GC cycle, reducing pauses.

-

Application threads don’t have to stop for as long.

-

It has six phases, all designed to minimize STW pause times.

-

It replaces main STW pause with two (usually very short) STW pauses.

-

It uses considerably more bookkeeping and lots more CPU time.

-

GC cycles overall take much longer.

-

By default, half of CPUs are used for GC when running concurrently.

-

It should not be used except for low-pause applications.

-

It definitely should not be used for applications with high-throughput requirements.

-

It does not compact, and in cases of high fragmentation will fall back to the default (parallel) collector.

Finally, HotSpot also has a Serial collector (and SerialOld collector) and a collector known as “Incremental CMS.” These collectors are all considered deprecated and should not be used.

Finalization

There is one old technique for resource management known as finalization that the developer should be aware of. However, this technique is extremely heavily deprecated and the vast majority of Java developers should not directly use it under any circumstances.

Note

Finalization has only a very small number of legitimate use cases, and

only a tiny minority of Java developers will ever encounter them. If in any

doubt, do not use finalization—try-with-resources is usually the

correct alternative.

The finalization mechanism was intended to automatically release resources once they are no longer needed. Garbage collection automatically frees up the memory resources used by objects, but objects can hold other kinds of resources, such as open files and network connections. The garbage collector cannot free these additional resources for you, so the finalization mechanism was intended to allow the developer to perform cleanup tasks as closing files, terminating network connections, deleting temporary files, and so on.

The finalization mechanism works as follows: if an object has a

finalize() method (usually called a finalizer), this is invoked

some time after the object becomes unused (or unreachable) but before the

garbage collector reclaims the space allocated to the object. The

finalizer is used to perform resource cleanup for an object.

In Oracle/OpenJDK the technique used is as follows:

-

When a finalizable object is no longer reachable, a reference to it is placed on an internal finalization queue and the object is marked, and considered live for the purposes of the GC run.

-

One by one, objects on the finalization queue are removed and their

finalize()methods are invoked. -

After a finalizer is invoked, the object is not freed right away. This is because a finalizer method could resurrect the object by storing the

thisreference somewhere (for example, in a public static field on some class) so that the object once again has references. -

Therefore, after

finalize()has been called, the garbage collection subsytem must redetermine that the object is unreachable before it can be garbage collected. -

However, even if an object is resurrected, the finalizer method is never invoked more than once.

-

All of this means that objects with a

finalize()will usually survive for (at least) one extra GC cycle (and if they’re long-lived, that means one extra full GC).

The central problem with finalization is that Java makes no guarantees about when garbage collection will occur or in what order objects will be collected. Therefore, the platform can make no guarantees about when (or even whether) a finalizer will be invoked or in what order finalizers will be invoked.

Finalization Details

For the few use cases where finalization is appropriate, we include some additional details and caveats:

-

The JVM can exit without garbage collecting all outstanding objects, so some finalizers may never be invoked. In this case, resources such as network connections are closed and reclaimed by the operating system. Note, however, that if a finalizer that deletes a file does not run, that file will not be deleted by the operating system.

-

To ensure that certain actions are taken before the VM exits, Java provides

Runtime::addShutdownHook—it can safely execute arbitrary code before the JVM exits. -

The

finalize()method is an instance method, and finalizers act on instances. There is no equivalent mechanism for finalizing a class. -

A finalizer is an instance method that takes no arguments and returns no value. There can be only one finalizer per class, and it must be named

finalize(). -

A finalizer can throw any kind of exception or error, but when a finalizer is automatically invoked by the garbage collection subsystem, any exception or error it throws is ignored and serves only to cause the finalizer method to return.

The finalization mechanism is an attempt to implement a similar concept present in other languages and environments.

In particular, C++ has a pattern known as RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization) that provides automatic resource management in a similar way.

In that pattern, a destructor method (which would be called finalize() in Java) is provided by the programmer, to perform cleanup and release of resources when the object is destroyed.

The basic use case for this is fairly simple: when an object is created, it takes ownership of some resource, and the object’s ownership of that resource is tied to the lifetime of the object. When the object dies, the ownership of the resource is automatically relinquished, as the platform calls the destructor without any programmer intervention.

While finalization superficially sounds similar to this mechanism, in reality it is fundamentally different. In fact, the finalization language feature is fatally flawed, due to differences in the memory management schemes of Java versus C++.

In the C++ case, memory is handled manually, with explicit lifetime management of objects under the control of the programmer. This means that the destructor can be called immediately after the object is deleted (the platform guarantees this), and so the acquisition and release of resources is directly tied to the lifetime of the object.

On the other hand, Java’s memory management subsystem is a garbage collector that runs as needed, in response to running out of available memory to allocate.

It therefore runs at variable (and nondeterministic) intervals and so finalize() is run only when the object is collected, and this will be at an unknown time.

If the finalize() mechanism was used to automatically release resources (e.g., filehandles), then there is no guarantee as to when (if ever) those resources will actually become available.

This has the result of making the finalization mechanism fundamentally unsuitable for its stated purpose—automatic resource management.

We cannot guarantee that finalization will happen fast enough to prevent us from running out of resources.

Note

An automatic cleanup mechanism for protecting scarce resources (such as filehandles), finalization is broken by design.

The only real use case for a finalizer is the case of a class with native methods, holding open some non-Java resource.

Even here, the block-structured approach of try-with-resources is preferable, but it can make sense to also declare a public native finalize() (which would be called by the close() method); this would release native resources, including off-heap memory that is not under the control of the Java garbage collector.

This would enable the finalization mechanism to act as a “Hail Mary” protection in case a programmer fails to call close().

However, even here, TWR provides a better mechanism and automatic support for block-structured code.

Java’s Support for Concurrency

The idea of a thread is that of a lightweight unit of execution—smaller than a process, but still capable of executing arbitrary Java code. The usual way that this is implemented is for each thread to be a fully fledged unit of execution to the operating system but to belong to a process, with the address space of the process being shared between all threads comprising that process. This means that each thread can be scheduled independently and has its own stack and program counter but shares memory and objects with other threads in the same process.

The Java platform has had support for multithreaded programming from the very first version. The platform exposes the ability to create new threads of execution to the developer.

To understand this, first we must consider what happens in detail when a Java program starts up and the original application thread (usually referred to as main thread) appears:

-

The programmer executes

java Main. -

This causes the Java Virtual Machine, the context within which all Java programs run, to start up.

-

The JVM examines its arguments, and sees that the programmer has requested execution starting at the entry point (the

main()method) ofMain.class. -

Assuming that

Mainpasses classloading checks, a dedicated thread for the execution of the program is started (main thread). -

The JVM bytecode interpreter is started on main thread.

-

Main thread’s interpreter reads the bytecode of

Main::main()and execution begins, one bytecode at a time.

Every Java program starts this way, but this also means that:

-

Every Java program starts as part of a managed model with one interpreter per thread.

-

The JVM has a certain ability to control a Java application thread.

Following on from this, when we create new threads of execution in Java code, this is usually as simple as:

Threadt=newThread(()->{System.out.println("Hello Thread");});t.start();

This small piece of code creates and starts a new thread, which executes the body of the lambda expression and then executes.

Note

For programmers coming from older versions of Java, the lambda is effectively being converted to an instance of the Runnable interface before being passed to the Thread constructor.

The threading mechanism allows new threads to execute concurrently with the original application thread and the threads that the JVM itself starts up for various purposes.

For mainstream implementations of the Java platform, every time we call Thread::start() this call is delegated to the operating system, and a new OS thread is created.

This new OS thread exec()’s a new copy of the JVM bytecode interpreter.

The interpreter starts executing at the run() method (or, equivalently, at the body of the lambda).

This means that application threads have their access to the CPU controlled by the operating system scheduler—a built-in part of the OS that is responsible for managing timeslices of processor time (and that will not allow an application thread to exceed its allocated time).

In more recent versions of Java, an increasing trend toward runtime-managed concurrency has appeared. This is the idea that for many purposes it’s not desirable for developers to explicitly manage threads. Instead, the runtime should provide “fire and forget” capabilities, whereby the program specifies what needs to be done, but the low-level details of how this is to be accomplished are left to the runtime.

This viewpoint can be seen in the concurrency toolkit contained in

java.util.concurrent, a full discussion of which is outside the scope

of this book. The interested reader should refer to Java Concurrency in

Practice by Brian Goetz et al. (Addison-Wesley).

For the remainder of this chapter, we will introduce the low-level concurrency mechanisms that the Java platform provides, and that every Java developer should be aware of.

Thread Lifecycle

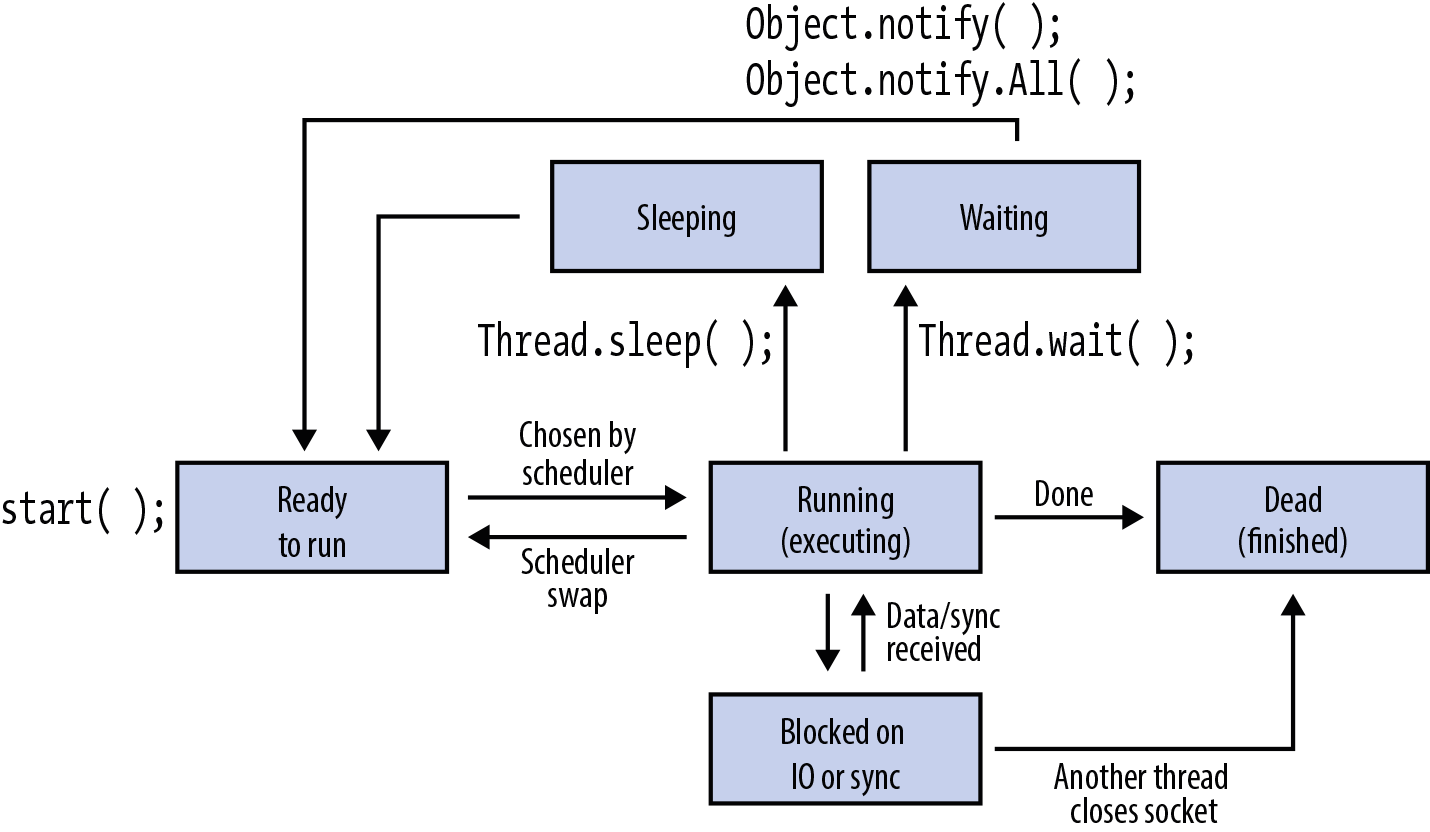

Let’s start by looking at the lifecycle of an application thread.

Every operating system has a view of threads that can differ in the

details (but in most cases is broadly similar at a high level). Java

tries hard to abstract these details away, and has an enum called

Thread.State, which wrappers over the operating system’s view of the

thread’s state. The values of Thread.State provide an overview of the

lifecycle of a thread:

NEW-

The thread has been created, but its

start()method has not yet been called. All threads start in this state. RUNNABLE-

The thread is running or is available to run when the operating system schedules it.

BLOCKED-

The thread is not running because it is waiting to acquire a lock so that it can enter a

synchronizedmethod or block. We’ll see more aboutsynchronizedmethods and blocks later in this section. WAITING-

The thread is not running because it has called

Object.wait()orThread.join(). TIMED_WAITING-

The thread is not running because it has called

Thread.sleep()or has calledObject.wait()orThread.join()with a timeout value. TERMINATED-

The thread has completed execution. Its

run()method has exited normally or by throwing an exception.

These states represent the view of a thread that is common (at least across mainstream operating systems), leading to a view like that in Figure 6-4.

Figure 6-4. Thread lifecycle

Threads can also be made to sleep, by using the Thread.sleep()

method. This takes an argument in milliseconds, which indicates how

long the thread would like to sleep for, like this:

try{Thread.sleep(2000);}catch(InterruptedExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}

Note

The argument to sleep is a request to the operating system, not a demand. For example, your program may sleep for longer than requested, depending on load and other factors specific to the runtime environment.

We will discuss the other methods of Thread later in this chapter, but

first we need to cover some important theory that deals with how threads

access memory, and that is fundamental to understanding why

multithreaded programming is hard and can cause developers a lot of

problems.

Visibility and Mutability

In mainstream Java implementations, all Java application threads in a process have their own call stacks (and local variables) but share a single heap. This makes it very easy to share objects between threads, as all that is required is to pass a reference from one thread to another. This is illustrated in Figure 6-5.

This leads to a general design principle of Java—that objects are visible by default. If I have a reference to an object, I can copy it and hand it off to another thread with no restrictions. A Java reference is essentially a typed pointer to a location in memory—and threads share the same address space, so visible by default is a natural model.

In addition to visible by default, Java has another property that is

important to fully understand concurrency, which is that objects are

mutable—the contents of an object instance’s fields can usually be

changed. We can make individual variables or references constant by

using the final keyword, but this does not apply to the contents of

the object.

As we will see throughout the rest of this chapter, the combination of these two properties—visibility across threads and object mutability—gives rise to a great many complexities when trying to reason about concurrent Java programs.

Figure 6-5. Shared memory between threads

Concurrent safety

If we’re to write correct multithreaded code, then we want our programs to satisfy a certain important property.

In Chapter 5, we defined a safe object-oriented program to be one where we move objects from legal state to legal state by calling their accessible methods. This definition works well for single-threaded code. However, there is a particular difficulty that comes about when we try to extend it to concurrent programs.

Tip

A safe multithreaded program is one in which it is impossible for any object to be seen in an illegal or inconsistent state by any another object, no matter what methods are called, and no matter in what order the application threads are scheduled by the operating system.

For most mainstream cases, the operating system will schedule threads to run on particular processor cores at seemingly random times, depending on load and what else is running in the system. If load is high, then there may be other processes that also need to run.

The operating system will forcibly remove a Java thread from a CPU core if it needs to. The thread is suspended immediately, no matter what it’s doing—including being partway through a method. However, as we discussed in Chapter 5, a method can temporarily put an object into an illegal state while it is working on it, providing it corrects it before the method exits.

This means that if a thread is swapped off before it has completed a long-running method, it may leave an object in an inconsistent state, even if the program follows the safety rules. Another way of saying this is that even data types that have been correctly modeled for the single-threaded case still need to protect against the effects of concurrency. Code that adds on this extra layer of protection is called concurrently safe, or (more informally) threadsafe.

In the next section, we’ll discuss the primary means of achieving this safety, and at the end of the chapter, we’ll meet some other mechanisms that can also be useful under some circumstances.

Exclusion and Protecting State

Any code that modifies or reads state that can become inconsistent must be protected. To achieve this, the Java platform provides only one mechanism: exclusion.

Consider a method that contains a sequence of operations that, if interrupted partway through, could leave an object in an inconsistent or illegal state. If this illegal state was visible to another object, incorrect code behavior could occur.

For example, consider an ATM or other cash-dispensing machine:

publicclassAccount{privatedoublebalance=0.0;// Must be >= 0// Assume the existence of other field (e.g., name) and methods// such as deposit(), checkBalance(), and dispenseNotes()publicAccount(doubleopeningBal){balance=openingBal;}publicbooleanwithdraw(doubleamount){if(balance>=amount){try{Thread.sleep(2000);// Simulate risk checks}catch(InterruptedExceptione){returnfalse;}balance=balance-amount;dispenseNotes(amount);returntrue;}returnfalse;}}

The sequence of operations that happens inside withdraw() can leave

the object in an inconsistent state. In particular, after we’ve checked

the balance, a second thread could come in while the first was sleeping

in simulated risk checks, and the account could be overdrawn, in

violation of the constraint that balance >= 0.

This is an example of a system where the operations on the objects are

single-threaded safe--(because the objects cannot reach an illegal state

(balance < 0) if called from a single thread)--but not concurrently

safe.

To allow the developer to make code like this concurrently safe, Java

provides the synchronized keyword. This keyword can be applied to a

block or to a method, and when it is used, the platform uses it to

restrict access to the code inside the block or method.

Note

Because synchronized surrounds code, many developers are led to the

conclusion that concurrency in Java is about code. Some texts even refer

to the code that is inside the synchronized block or method as a

critical section and consider that to be the crucial aspect of

concurrency. This is not the case; instead, it is the inconsistency of

data that we must guard against, as we will see.

The Java platform keeps track of a special token, called a monitor,

for every object that it ever creates. These monitors (also called

locks) are used by synchronized to indicate that the following code

could temporarily render the object inconsistent. The sequence of

events for a synchronized block or method is:

-

Thread needs to modify an object and may make it briefly inconsistent as an intermediate step

-

Thread acquires the monitor, indicating it requires temporary exclusive access to the object

-

Thread modifies the object, leaving it in a consistent, legal state when done

-

Thread releases the monitor

If another thread attempts to acquire the lock while the object is being modified, then the attempt to acquire the lock blocks, until the holding thread releases the lock.

Note that you do not have to use the synchronized statement unless

your program creates multiple threads that share data. If only one

thread ever accesses a data structure, there is no need to protect it

with synchronized.

One point is of critical importance—acquiring the monitor does not prevent access to the object. It only prevents any other thread from claiming the lock. Correct concurrently safe code requires developers to ensure that all accesses that might modify or read potentially inconsistent state acquire the object monitor before operating on or reading that state.

Put another way, if a synchronized method is working on an object and

has placed it into an illegal state, and another method (which is not

synchronized) reads from the object, it can still see the inconsistent

state.

Note

Synchronization is a cooperative mechanism for protecting state and it

is very fragile as a result. A single bug (such as missing a single

synchronized keyword from a method it’s required on) can have

catastrophic results for the safety of the system as a whole.

The reason we use the word synchronized as the keyword for “requires

temporary exclusive access” is that in addition to acquiring the

monitor, the JVM also rereads the current state of the object from main

memory when the block is entered. Similarly, when the synchronized

block or method is exited, the JVM flushes any modified state of the

object back to main memory.

Without synchronization, different CPU cores in the system may not see the same view of memory, and memory inconsistencies can damage the state of a running program, as we saw in our ATM example.

The simplest example of this is known as lost update, as demonstrated in the following code:

publicclassCounter{privateinti=0;publicintincrement(){returni=i+1;}}

This can be driven via a simple control program:

Counterc=newCounter();intREPEAT=10_000_000;Runnabler=()->{for(inti=0;i<REPEAT;i++){c.increment();}};Threadt1=newThread(r);Threadt2=newThread(r);t1.start();t2.start();t1.join();t2.join();intanomaly=(2*REPEAT+1)-c.increment();doubleperc=((anomaly+0.0)*100)/(2*REPEAT);System.out.println("Lost updates: "+anomaly+" ; % = "+perc);

If this concurrent program was correct, then the value for lost update should be exactly zero. It is not, and so we may conclude that unsynchronized access is fundamentally unsafe.

By contrast, we also see that the addition of the keyword synchronized to the increment method is sufficient to reduce the lost update anomaly to zero—that is, to make the method correct, even in the presence of multiple threads.

volatile

Java provides another keyword for dealing with concurrent access to

data. This is the volatile keyword, and it indicates that before

being used by application code, the value of the field or variable must

be reread from main memory. Equally, after a volatile value has been

modified, as soon as the write to the variable has completed, it

must be written back to main memory.

One common usage of the volatile keyword is in the

“run-until-shutdown” pattern. This is used in multithreaded programming

where an external user or system needs to signal to a processing thread

that it should finish the current job being worked on and then shut down

gracefully. This is sometimes called the “graceful completion” pattern.

Let’s look at a typical example, supposing that this code for our

processing thread is in a class that implements Runnable:

privatevolatilebooleanshutdown=false;publicvoidshutdown(){shutdown=true;}publicvoidrun(){while(!shutdown){// ... process another task}}

All the time that the shutdown() method is not called by another

thread, the processing thread continues to sequentially process tasks

(this is often combined very usefully with a BlockingQueue to deliver

work). Once shutdown() is called by another thread, the

processing thread immediately sees the shutdown flag change to true.

This does not affect the running job, but once the task finishes, the

processing thread will not accept another task and instead will shut

down gracefully.

However, useful as the volatile keyword is, it does not provide a complete protection of state—as we can see by using it to mark the field in Counter as volatile.

We might naively assume that this would protect the code in Counter.

Unfortunately, the observed value of the anomaly (and therefore, the presence of the lost update problem) indicates that this is not the case.

Useful Methods of Thread

The Thread class has a

number of methods on it to make your life easier when you’re creating new application threads. This is

not an exhaustive list—there are many other methods on Thread, but

this is a description of some of the more common methods.

getPriority() and setPriority()

These methods are used to control the priority of threads. The scheduler decides how to handle thread priorities—for example, one strategy could be to not have any low-priority threads run while there are high-priority threads waiting. In most cases, there is no way to influence how the scheduler will interpret priorities. Thread priorities are represented as an integer between 1 and 10, with 10 being the highest.

setName() and getName()

These methods allow the developer to set or retrieve a name for an individual

thread. Naming threads is good practice, as it can make debugging much

easier, especially when using a tool such as jvisualvm, which we will

discuss in “Introduction to JShell”.

getState()

This returns a Thread.State object that indicates which state this thread

is in, as per the values defined in

“Thread Lifecycle”.

interrupt()

If a thread is blocked in a sleep(), wait(), or join() call, then

calling interrupt() on the Thread object that represents the thread

will cause the thread to be sent an InterruptedException (and to wake

up).

If the thread was involved in interruptible I/O, then the I/O will

be terminated and the thread will receive a

ClosedByInterruptException. The interrupt status of the thread will be

set to true, even if the thread was not engaged in any activity that

could be interrupted.

setDaemon()

A user thread is a thread that will prevent the process from exiting

if it is still alive—this is the default for threads. Sometimes,

programmers want threads that will not prevent an exit from

occurring—these are called daemon threads. The status of a thread as

a daemon or user thread can be controlled by the setDaemon() method and checked using isDaemon().

setUncaughtExceptionHandler()

When a thread exits by throwing an exception (i.e., one that the program did not catch), the default behavior is to print the name of the thread, the type of the exception, the exception message, and a stack trace. If this isn’t sufficient, you can install a custom handler for uncaught exceptions in a thread. For example:

// This thread just throws an exceptionThreadhandledThread=newThread(()->{thrownewUnsupportedOperationException();});// Giving threads a name helps with debugginghandledThread.setName("My Broken Thread");// Here's a handler for the error.handledThread.setUncaughtExceptionHandler((t,e)->{System.err.printf("Exception in thread %d '%s':"+"%s at line %d of %s%n",t.getId(),// Thread idt.getName(),// Thread namee.toString(),// Exception name and messagee.getStackTrace()[0].getLineNumber(),e.getStackTrace()[0].getFileName());});handledThread.start();

This can be useful in some situations—for example, if one thread is supervising a group of other worker threads, then this pattern can be used to restart any threads that die.

There is also setDefaultUncaughtExceptionHandler(), a static method that sets a backup handler for catching any thread’s uncaught exceptions.

Deprecated Methods of Thread

In addition to the useful methods of Thread, there are a number of

unsafe methods that you should not use. These methods form

part of the original Java thread API, but were quickly found to be not

suitable for developer use. Unfortunately, due to Java’s backward

compatibility requirements, it has not been possible to remove them from

the API. Developers simply need to be aware of them, and to avoid

using them under all circumstances.

stop()

Thread.stop() is almost impossible to use correctly without violating

concurrent safety, as stop() kills the thread immediately, without

giving it any opportunity to recover objects to legal states. This is in

direct opposition to principles such as concurrent safety, and so should

never be used.

suspend(), resume(), and countStackFrames()

The suspend() mechanism does not release any monitors it holds when

it suspends, so any other thread that attempts to access those

monitors will deadlock. In practice, this mechanism produces race

conditions between these deadlocks and resume() that render this

group of methods unusable.

destroy()

This method was never implemented—it would have suffered from the same

race condition issues as suspend() if it had been.

All of these deprecated methods should always be avoided. A set of safe alternative patterns that achieve the same intended aims as the preceding methods have been developed. A good example of one of these patterns is the run-until-shutdown pattern that we have already met.

Working with Threads

In order to work effectively with multithreaded code, it’s important to have the basic facts about monitors and locks at your command. This checklist contains the main facts that you should know:

-

Synchronization is about protecting object state and memory, not code.

-

Synchronization is a cooperative mechanism between threads. One bug can break the cooperative model and have far-reaching consequences.

-

Acquiring a monitor only prevents other threads from acquiring the monitor—it does not protect the object.

-

Unsynchronized methods can see (and modify) inconsistent state, even while the object’s monitor is locked.

-

Locking an

Object[]doesn’t lock the individual objects. -

Primitives are not mutable, so they can’t (and don’t need to) be locked.

-

synchronizedcan’t appear on a method declaration in an interface. -

Inner classes are just syntactic sugar, so locks on inner classes have no effect on the enclosing class (and vice versa).

-

Java’s locks are reentrant. This means that if a thread holding a monitor encounters a synchronized block for the same monitor, it can enter the block.2

We’ve also seen that threads can be asked to sleep for a period of time.

It is also useful to go to sleep for an unspecified amount of time, and

wait until a condition is met. In Java, this is handled by the

wait() and notify() methods that are present on Object.

Just as every Java object has a lock associated with it, every object

maintains a list of waiting threads. When a thread calls the wait()

method of an object, any locks the thread holds are temporarily

released, and the thread is added to the list of waiting threads for

that object and stops running. When another thread calls the

notifyAll() method of the same object, the object wakes up the

waiting threads and allows them to continue running.

For example, let’s look at a simplified version of a queue that is safe for multithreaded use:

/** One thread calls push() to put an object on the queue.* Another calls pop() to get an object off the queue. If there is no* data, pop() waits until there is some, using wait()/notify().*/publicclassWaitingQueue<E>{LinkedList<E>q=newLinkedList<E>();// storagepublicsynchronizedvoidpush(Eo){q.add(o);// Append the object to the end of the listthis.notifyAll();// Tell waiting threads that data is ready}publicsynchronizedEpop(){while(q.size()==0){try{this.wait();}catch(InterruptedExceptionignore){}}returnq.remove();}}

This class uses a wait() on the instance of WaitingQueue if the

queue is empty (which would make the pop() fail). The waiting thread

temporarily releases its monitor, allowing another thread to claim it—a

thread that might push() something new onto the queue. When the

original thread is woken up again, it is restarted where it originally

began to wait—and it will have reacquired its monitor.

Note

wait() and notify() must be used inside a synchronized method or

block, because of the temporary relinquishing of locks that is required

for them to work properly.

In general, most developers shouldn’t roll their own classes like the one in this example—instead, make use of the libraries and components that the Java platform provides for you.

Summary

In this chapter, we’ve discussed Java’s view of memory and concurrency, and seen how these topics are intrinsically linked. As processors develop more and more cores, we will need to use concurrent programming techniques to make effective use of those cores. Concurrency is key to the future of well-performing applications.

Java’s threading model is based on three fundamental concepts:

- Shared, visible-by-default mutable state

-

This means that objects are easily shared between different threads in a process, and that they can be changed (“mutated”) by any thread holding a reference to them.

- Preemptive thread scheduling

-

The OS thread scheduler can swap threads on and off cores at more or less any time.

- Object state can only be protected by locks

-

Locks can be hard to use correctly, and state is quite vulnerable—even in unexpected places such as read operations.

Taken together, these three aspects of Java’s approach to concurrency explain why multithreaded programming can cause so many headaches for developers.