Trans-Seasonality, Talismans, and Landscape

Japanese poetry displays extreme sensitivity to the transience of nature and the passing of the seasons. This might be attributed to the rainy climate and the quick growth of vegetation; for example, the reed (ashi), which became a symbol of Japan in the ancient period, is one of the fastest-growing plants in the world. A more convincing explanation, however, is that natural change came to be a metaphor for the transience of life and the uncertainties of this world, a view that was reinforced by the Buddhist belief in the evanescence of all things. This perspective became particularly prominent from the Heian period (794–1185) and permeates poetic representations of both nature and human life, as exemplified by such a seasonal topic as cherry blossoms, which scatter as soon as they bloom.

The notion of nature as constant transformation was also accompanied by either talismanic or trans-seasonal representations of nature, which sought to counter ephemerality. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “talisman” as “a stone, ring, or other object engraven with figures or characters, to which are attributed occult powers of the planetary influences and celestial configurations under which it was made; usually worn as an amulet to avert evil from or bring fortune to the wearer; also medicinally used to impart healing virtue; hence, any object held to be endowed with magic virtue; a charm.”1 These talismanic functions, whose power in Japan is generally drawn from different aspects of the natural world, are a recurrent feature of textual, visual, and dramatic representations of nature. A close examination of the history of culturally prominent plants reveals three fundamental types:

• Those such as the cherry blossom, bush clover, and yellow valerian, which embody impermanence, fragility, and vulnerability

• Those such as the plum, mandarin orange, wisteria, and chrysanthemum, which are associated with a specific season but sometimes also have auspicious and talismanic functions

• Those such as the pine and bamboo, which transcend the seasons and have very strong talismanic functions

The talismanic powers of natural motifs emerged in the ancient period, played an important role in the court culture of the Heian period, and continued to be of major importance in the medieval period (1185–1599). In noh plays of the Muromachi period (1392–1573), this function was carried out by the deity- or god-noh (waki-nō) plays, which came at the beginning of a day of performances. The most famous of these dramas are Takasago, Kiku jidō (Chrysanthemum Child), and Tsurukame (Crane and Turtle), which use icons of nature as a means to pray for long life and happiness. This talismanic function also appears in a wide range of Muromachi popular tales (otogi-zōshi), including “Urashima Tarō” (Urashima’s Eldest Son), “Sazareishi” (Small Stones), and “Suehiro monogatari” (Tale of the Open Fan).2 In the early Edo period (1600–1867), such stories were read by young women at the beginning of the New Year to bring good luck and were given as bridal gifts (yomeiri-bon). These auspicious narratives (shūgi-mono) represent prayers for happiness in marriage, birth of children, achievement of wealth, promotion in rank, and other forms of worldly success, but the most frequent prayer is for longevity and rejuvenation. In all these texts, trans-seasonal or talismanic icons of nature play a major role, as do such utopian spaces as the Buddhist Pure Land (Jōdo), Mount Hōrai (Jp. Hōrai-san, Ch. Penglai), and the Dragon Palace (Ryūgū), where old age and death are suspended. These idealized other worlds, which are represented not only in Muromachi tales but in Japanese gardens, were derived from Indian, Chinese, and Japanese myths and often fused various mythic elements. Perhaps the most frequently used natural symbols are pine and bamboo, crane and turtle, and the seven herbs (nanakusa), which are also the main ingredients of New Year annual observances. “Nanakusa sōshi” (The Tale of Seven Herbs), a Muromachi tale set in China, tells how the seven herbs acquired felicitous value. A number of talismanic stories, like their noh counterparts, are set in the ancient period, describing emperors who lived for an extremely long time—an image that was also thought to be felicitous. Reading a tale, such as “Bunshō sōshi” (The Tale of Bunshō) or “Issun bōshi” (Little One-Inch), about a commoner of low birth rising to great social heights, a miraculous happening that would have been attractive to commoner audiences, was also thought to bring good luck. As Ichiko Teiji has noted, the popularity of these kinds of tales in the Muromachi period may be attributed to a general sense of impermanence caused by the chaos of war, the instability of society, and the uncertainty of everyday life.3 The desire for talismanic protection extended from the lowest levels to the highest reaches of Heian court and medieval elite samurai society, where it was represented in the most lavish attention to screen paintings, design, and dress.

The Power of Green

In the ancient period, the green leaves and colorful flowers that appear in spring were believed to be full of a life force. Songs describing the thickening of the tree leaves and the blooming of the flowers were a means to praise and tap into that life force. Flowers, leaves, and branches of trees were broken off and placed in the hair (an action called kazasu) so that the life force could be transferred to the body. This early belief eventually led, in the eighth century, to the custom at banquets of decorating hair with a branch or flower—usually that of willow, plum, bush clover, or pink.

The leaves of evergreen trees such as mistletoe (hoyo or yadorigi), mandarin orange (tachibana), Japanese cedar (sugi), and pine (matsu) were thought to have particular vitality. In a poem in the Man’yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, ca. 759) composed by Ōtomo no Yakamochi (717?–785) at a banquet in the spring, on the second day of the First Month of 750, the poet decorates his hair with mistletoe, which remains green throughout the winter: “Taking the mistletoe from the top of the mountain and placing it in my hair, wanting to celebrate a thousand years” (Ashihiki no yama no konure no hoyo torite kazashitsuraku wa chitose hoku to so [18:4136]). A similar belief lies behind the use of branches of the sakaki (a kind of camellia) in Shinto ceremonies and the shikimi (Japanese anise tree) in Buddhist rituals. The arrival of spring was marked by a series of rites such as flower viewing (hana-mi), originally thought to transfer the life force of the flowers to the participants. In no-asobi (prayers in the moor), one of the most important spring observances, grasses were gathered, boiled, and eaten so that their fresh life force could be absorbed into the body.

The belief in the magico-religious power of flowers and plants is also evident in the flower-grass designs that were brought to Japan from Tang China (618–907), became popular among Japanese aristocrats in the seventh and eighth centuries, and are preserved in the Shōsōin, in the Tōdaiji temple, in Nara. The most popular of these symmetrical designs were of the lotus (hasu); palmette (parumetto), which looks like an open fan and resembles a palm leaf; hōsōge (literally, “treasury flower”); and karakusa (literally, “Chinese grass”), a pattern of vines—plants or flowers that were thought never to fade. The hōsōge figure combines the peony, lotus, pomegranate, and other flowers to create a single beautiful flower in an arabesque pattern; in China, it was thought to bloom in Buddhist Heaven and the land of the immortals and is represented on Japanese sutra containers.

The most important and by far the most popular of the trans-seasonal trees is the pine (matsu), an evergreen with needle-shaped leaves. Of the many types of pine native to Japan, the red pine (akamatsu) and the black pine (kuromatsu) are the best known. The red pine grows in mountains and fields, where it was cultivated, and the black pine flourishes on the seacoast. From the ancient period, pine was used for lumber and for pine torches (taimatsu), but culturally it was known for its long life and unchanging green color and consequently became a sacred tree associated with longevity, as in this poem by Ki no Asomi Kahito: “The pine, the tree that waits for a thousand reigns, that flourishes and stands godly at Shigeoka, knows no year” (Shigeoka ni kamusabitachite sakaetaru chiyo matsu no ki no toshi no shiranaku [Man’yōshū, 6:990]).

In another poem, Ōtomo no Yakamochi contrasts flowers, which fade and wither, with the pine, which remains unchanged: “As the eight thousand flowers fade, let us tie the branch of the unchanging pine” (Yachikusa no hana wa utsurou tokiwa naru matsu no saeda wo ware wa musubana [Man’yōshū, 20:4501]). In the ancient period, tying a ribbon to a branch of the pine was an act of prayer for safety and long life. The root of the pine was thought to have no end (tayuru koto naku), as in a poem written by a woman who was confident that her lover would remain true to her: “Like the root of the pine that grows god-like on the crags, your heart will not forget me” (Kamusabite iwao ni ouru matsu ga ne no kimi ga kpkpro wa wasurekane-tsumo [Man’yōshū, 12:3047]). The pine also functioned as a yorishiro, a place for a god to rest or descend to the Earth. The gate pine (kadomatsu) set out for the New Year, the three pines placed on the bridge (hashigakari) of the noh stage, and the old pine (oimatsu) depicted on the backs of mirrors—all derive from the belief in the pine as a talisman. In the Heian period, the rite of “pulling up the small pine” (kpmatsu-hiki), performed on the first Day of the Rat (Nenohi) in the First Month, was similarly a prayer for long life. The pine was the main tree in the palace-style (shinden-zukuri) garden of the Heian period, and the reflection of the pine in the lake was taken as an image of the prosperity of the owner of the residence. The pine also became an indispensable element in Heian-period screen paintings (byōbu-e) commissioned for celebratory occasions.

In waka (classical poetry), the pine has specific homophonic associations, especially with the verb matsu (to wait) and with the emotions of waiting for a lover: “If the flower of the plum tree blooms and scatters, I will be the pine that waits, wondering if my beloved will come or not come” (Ume no hana sakite chirinaba wagimoko wo komu ka koji ka to aga matsu no ki so [Man’yōshū, 10:1922]).4 Indeed, the association of the pine with waiting grew so strong that by the mid-tenth century, more than half the poems that feature the image of the pine appear in the love books of the Gosenshū (Later Collection, 951). Like many other natural images, the pine had multiple purposes, depending on the topic, context, and genre.

Another major talismanic plant is bamboo (take), a perennial grass that multiplies through its underground stems.5 Like China, Japan depended heavily on bamboo for everyday life; it was used for food, building material, brush handles, flutes, bows, arrows, umbrellas, fans, brooms, and lamp shades. The young buds or shoots (takenoko; literally, “children of bamboo”), which emerge underground, were also valued as food. In all probability, the fast growth of bamboo was considered auspicious, and the bamboo epithet implied long life and prosperity. Bamboo also became associated with immortality as a result of its evergreen leaves, and it appears frequently in the celebration (ga) books of the imperial waka anthologies from the Go-senshū onward, as in this poem from the Shūishū (Collection of Gleanings, 1005–1007), composed for a screen painting made in 934 to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of an empress: “Only you will see which lasts longer—the bamboo or the pine, both of unchanging color” (Iro kaenu matsu to take to no sue no yo wo izure hisashi to kimi nomi zo mimu [Celebration, no. 275]). Bamboo also came to be identified with long life because of the numerous “joints” (fushi) in the stem, as in this poem from the Senzaishū (Collection of a Thousand Years) 1183): “Above all, you compare to the thousand years packed in the many joints of the bamboo that I planted and view in the brushwood fence” (Uete miru magaki no take no fushigoto ni komoreru chiyo wa kimi zo yosoen [Celebration, no. 607]). In China, bamboo forests were associated with the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (Ch. Zhu lin qi xian, Jp. Chikurin no shichiken), who turned their backs on the world and enjoyed themselves in a bamboo forest—a painting topic that became very popular in Japan in the Edo period. Since bamboo is an evergreen and grows straight, it also became a symbol of fidelity and chastity.

Talismanic Birds and Fish

The foremost example of a celebratory, trans-seasonal bird in Japanese culture is the crane (tsuru). The word tsuru usually refers to the modern tanchō tsuru, a large bird with a long neck and beak, big wings, long legs, and a relatively short tail. These cranes congregate near rivers, swamps, and the ocean, where they eat fish. The crane appears in forty-six poems in the Man’yōshū, coming in fourth in frequency among birds after the small cuckoo, wild goose, and bush warbler. Almost all the early crane poems were composed by aristocrats while traveling along the coast, where the crying crane (tazu) became an implicit metaphor for the loneliness of the traveler.6 Since the crane was thought to be happily mated and to care for its young, the crying of the crane was believed to express longing for its mate or its chicks.7 These associations—longing for home and for the family—continued into the Heian period, as in this poem from the Shikashū (Collection of Poetic Flowers, 1151–1154): “Separated from its young in the capital, the evening crane longs for its children, crying until dawn” (Yoru no tsuru miyako no uchi ni hanatarete ko wo koitsutsu mo nakiakasu kana [Miscellaneous 1, no. 340]). In the succeeding Kamakura period (1185–1333), the nun and poet Abutsu (d. 1283) wrote Yoru no tsuru (Evening Crane, ca. 1276), a poetry treatise, out of concern for the future of her son Reizei Tamesuke.

In the Heian period, the crane was also transformed into a symbol of long life. This shift of the crane from a flying bird to an auspicious bird, like the emergence of the auspicious chrysanthemum, probably reflects Chinese influence during the reign of Emperor Saga (786–842, r. 809–823). It is referred to as tsuru and often is combined with the turtle or the pine in celebratory poems (figure 18). In a poem by Kiyohara no Motosuke–“When winter comes to the crane that lives in the pine at Takasago, the frost on the hilltop no doubt becomes whiter than ever” (Takasago no matsu ni sumu tsuru fuyu kureba onoe no shimo ya okimasaruran [Shūishū, Winter, no. 237])—since the white crane roosts in the pine, the frost at the top of the hill becomes even whiter, enhancing the eternal life of the pine. (Like red, white was considered a talismanic color.) In his twelve-month bird-and-flower waka, which became popular among almost all Edo-period painting schools, Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241) placed the crane in the Tenth Month. As a consequence, the crane is depicted in the Tenth Month in twelve-month bird-and-flower screen paintings (jūnikagetsu kachōzu), including those by Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743)8 and Kanō Eikei (1662–1702).9 In short, the crane came to function as both a seasonal and a talismanic image.

In the Tenpyō era (729–749), decorative objects—many of which had originated in ancient Assyria and Egypt and in Persia—were brought to Japan from the continent by emissaries to Tang China and by visitors from Shiragi (in present-day Korea). A number of these objects were decorated with images of auspicious and magical birds, including the phoenix (hōō), kalavinka (karyōbinka), parrot (ōmu), mandarin duck (oshidori), peacock (kujaku), and flying bird with a flower in its beak (hana kui dori).10

In China, the phoenix was one of the four sacred animals, along with the kylin (kirin), dragon, and turtle. The Engishiki (Ceremonial Procedures of the Engi Era, 927) describes the phoenix as resembling a crane, having the head of a chicken (or rooster), the beak of a swallow, the neck of a snake, and the body of a dragon. In the section “Ko no hana wa” (As for Tree Flowers) in Makura no sōshi (The Pillow Book) ca. 1000), Sei Shōnagon notes that the lavender flowers of the paulownia are very attractive, that the leaves are broad and distinctive, and that in China the legendary phoenix selects the paulownia tree to roost in. In both China and Japan, the phoenix became a sign of peace and sage rule, and the emperor’s outer robe (hou) featured a paulownia, bamboo, and phoenix design. In Japan, the phoenix first appeared in handiwork and crafts of the Asuka period (late sixth—mid-seventh century) and became a major topic and motif in painting, architecture (such as the Byōdō-in at Uji, where the Amida Hall became known as the Phoenix Hall), and design of the Heian period.11 In the Momoyama period (1568–1615), the phoenix was very popular among warlords, who had it portrayed in screen paintings, a practice that continued into the Edo period, as exemplified by Phoenixes and Paulownia, a screen painting attributed to Tosa Mitsuyoshi (1539–1613).12 In the Edo period, bed covers were decorated with images of the paulownia and phoenix to ward off evil spirits at night.13

CRANE, PINE, AND RISING SUN

The rising sun (hinode), now used on the national flag, was considered an auspicious sight, particularly at the beginning of the year, and the crane and pine were associated with long life. This woodblock print (ca. 1852–1853) by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) is typical of a broader tradition of using such talismanic natural motifs. (Color woodblock print [signed Ichiryūsai]; vertical ōban, 28.4 × 9.8 inches. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William and John Spaulding Collection, 1921, no. 21.68888)

The kalavinka, an imaginary Buddhist bird with a bodhisattva for its upper body and a bird for its lower body, was believed to live in snowy mountains or a Buddhist heaven and to have a voice like that of the Buddha. The parrot, which also became an auspicious motif in Japanese painting and design, usually is depicted in pairs, with the two parrots facing each other. The mandarin duck, the male and female always swimming or sleeping together, similarly figures on Japanese ceramics, paintings, mirrors, noh robes, wedding furniture, and clothing as an auspicious symbol of fidelity and marital harmony. A flying bird with a flower or branch in its beak was believed to bring good fortune from the heavens. This image, which was very popular in the Tenpyō era, evolved into a flying crane with a pine branch in its beak, thus combining three symbols of longevity: the crane, the pine, and the bird with a flower in its beak. This triad appears widely on mirrors, lacquer-ware, and dyed cloth produced in the Heian and medieval periods.14

Almost all these exotic or magical birds were popular subjects for bird-and-flower paintings (kachōga), which emerged in the Northern and Southern Courts period (1336–1392) and flourished in the Edo period.15 These paintings, particularly those by the Kanō and Tosa schools—which were patronized by the military government (bakufu) and the imperial court, respectively—often were given as gifts on important occasions to high-ranking or powerful individuals. They had the ritualistic function of conferring good fortune on or acknowledging the virtue or authority of the recipient. If given as a wedding present, the painting was a good-luck charm, meant to ensure a harmonious and long-lasting relationship. These talismanic birds were frequently combined with auspicious trees and other plants (such as pines and bamboo) in designs to decorate clothing, furniture, and other objects.

As did certain plants and birds, some fish—notably the carp (koi) and the sea bream (tai)—became auspicious signs. In China, the word for “fish” (yu  ) was homophonous with the words for “extra” (yu

) was homophonous with the words for “extra” (yu  ) and “jewel” (yu

) and “jewel” (yu  ) and, as a consequence, came to mean “good fortune” and “the flourishing of descendents.” Since they produce many eggs, fish became a symbol of fertility and were a popular design motif in Japan from the ancient period. Shrimp (ebi), written with the characters

) and, as a consequence, came to mean “good fortune” and “the flourishing of descendents.” Since they produce many eggs, fish became a symbol of fertility and were a popular design motif in Japan from the ancient period. Shrimp (ebi), written with the characters  (Ch. hailao; literally, “elder of the sea”), came to connote long life. Katsuo (bonito) was regarded as auspicious among samurai because of the word’s homophony with katsu (to win), much as kuromame (black beans) were eaten at the New Year because they implied mame (good health or a strong body).

(Ch. hailao; literally, “elder of the sea”), came to connote long life. Katsuo (bonito) was regarded as auspicious among samurai because of the word’s homophony with katsu (to win), much as kuromame (black beans) were eaten at the New Year because they implied mame (good health or a strong body).

In the medieval period, the carp was considered the king of freshwater fish, and in section 118 of Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness, 1310–1331?), Priest Kenkō (ca. 1283?–1352?) refers to carp as the fish of all fish (figure 19). In China, the carp was thought to climb the rapids called Dragon Gate (Ryūmon) and become a dragon, and as a consequence it was valued as a symbol of social ascent or success; in Japan, it was served at a samurai’s coming-of-age ceremony (genpuku). The raising of carp streamers (koinobori) on poles at the Tango Festival (now Boy’s Day) is a continuation of this tradition.

In the Edo period, with the shift of political and economic power to major port cities, the sea bream, considered the best of the sea fish (being tasty, attractive in form, and auspicious), replaced the carp as the king of fish. In the famous opening line of “Hyakugyo no fu” (Ode to a Hundred Fish), the haikai poet Yokoi Yayū (1702–1783) writes: “Among humans, [the best] is the samurai; among pillars, the best is cypress; and among fish, it’s the sea bream” (Hito wa bushi, hashira wa hinoki, sakana wa tai to yomikeru).16 When the sea bream comes to the Inland Sea to spawn, its red color becomes even brighter than usual, due to hormones, and as a result it is called sakuradai (literally, “cherry-blossom sea bream”) or hanami-dai (cherry-blossom-viewing sea bream), both of which are seasonal words for spring. Before its spawning run, the sea bream eats a large quantity of shrimp, which was thought to intensify the fish’s red color. Because of its auspicious color and its phonic associations with the adjective medetai (auspicious), the tai came to be associated with Ebisu, one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune (Shichifukujin), who is depicted carrying a sea bream and who became a god of business for merchants. Merchant houses celebrated Ebisukō (Ebisu Festival) on the twentieth day of the Tenth Month with unlimited eating and drinking for employees, relatives, friends, and guests. Samurai, who sought to avoid being “cut” in battle, served the fish whole on celebratory occasions.

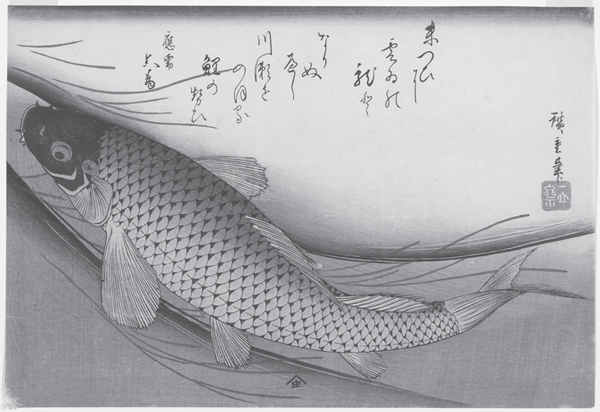

CARP WITH KYŌKA POETRY

This woodblock print (ca. 1840–1842) in Utagawa Hiroshige’s (1797–1858) “Fish Series” (Sakana-zukushi) has three major features: the talismanic function of the carp climbing the rapids; the realistic depiction of the fish; and the inscribed kyōka, which reinforces the talismanic theme of the dragon in the clouds: “In the end, it no doubt becomes a dragon in the clouds of the palace—the force of the carp climbing the river rapids” (Sue tsui ni kumoi no ryū to narinubeshi kawase wo noboru koi no ikioi). (Color woodblock print, 9.8 × 14.4 inches. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William and John Spaulding Collection, 1921, no. 21.9616)

Auspicious Topography

Both Heijō (Nara) and Heian (Kyoto), the capitals during the Nara (710–784) and Heian periods, sit in basins with mountains to the north, east, and west. In the seasonal poems of the Man’yōshū) spring first appears as mist over the mountains; the small cuckoo (hototogisu), the harbinger of summer, arrives from the other side of the mountains; the autumn deer live in the mountains; and the wild geese fly over the mountains. In other words, the mountains became the dominant landscape on which the four seasons unfold, as is evident in such poetic words as “autumn mountain” (aki-yama), which refers to bright foliage, and “summer mountain” (natsu-yama), which implies the deep green and dense vegetation caused by the long summer rains (samidare). At the same time, from as early as the Nara period, in the Kaifūsō (Nostalgic Recollections of Literature, 751), the first major anthology of kanshi (Chinese-style poetry), mountains were treated as a place of the immortals. In the sphere of Buddhist and folk religion, large mountains, particularly those with high and sharp peaks, were regarded as sacred and became the sites of annual pilgrimages.17

There were also talismanic landscapes, which were thought to bring good fortune and protection to their owners or creators. The most prominent example is the lake island (nakajima), a major feature of the palace-style (shinden-zukuri) garden of the Heian period (see figure 13). The lake with an island, which also appears in the gardens of temples and shrines, can be traced back to ancient beliefs about the Eternal Land (Tokoyo or Tokoyo no kuni), thought to be an island or a string of islands inhabited by gods.18 By building “isles of eternity” in their garden lakes, Japanese aristocrats in the Nara and subsequent periods sought to bring the power of those gods within their reach. The southern side of the palace-style residence is centered on a small lake with one or two of these islands. The edge of the island was often constructed to look like a rough seashore (araiso), a windswept beach lined with irregular boulders.19 The sea could also be evoked by a cove beach (suhama) or a series of deeply indented coves, which were created by laying out pebbles to look like a shoreline after the tide recedes.

Both the lake island and the cove beach became auspicious talismanic images in a wide range of Japanese traditional arts, from poetry to kimono, lacquerware (figure 20), mirrors, and furniture.20 For Heian-period poetry contests (uta-awase) and on celebratory occasions such as the New Year and weddings, a portable island stand (shima-dai), also referred to as a cove beach stand (suhama-dai), was placed in the central hall (shinden) of a palace-style residence. Figurines representing a small mountain; pines, bamboo, and plum; a crane and turtle; and/or an old man and old woman were placed on a miniature cove beach to create the felicitous image of Mount Hōrai (Jp. Hōrai-san, Ch. Penglai),21 a tradition that has continued to the present day.

From the late sixth century, Chinese beliefs about the three islands of immortals–Hōrai, Hōjō (Ch. Fangzhang), and Eishū (Ch. Yingzhou)—entered Japan and were fused with the indigenous belief in the Eternal Land.22 It was thought that when mortals approached Mount Hōrai, the wind would blow them away, not allowing them to step on the island. In the Heian period, the three mythic islands were combined with or transformed into Crane Island and Turtle Island, which had been familiar symbols of immortality and good fortune. Crane and Turtle islands made of rock became particularly popular in the Muromachi period and appeared in symbolic form in rock-and-sand gardens (kare-sansui).23 In the large gardens built by provincial warlords (daimyo) in the Momoyama and Edo periods, visitors were able to cross bridges and walk to the felicitous islands in the lakes.

Four Seasons in Four Directions

Another type of talismanic landscape was the four-seasons—four-directions garden, which appeared as early as the Heian period and is extremely prominent in Muromachi tales (otogi-zōshi). The notion of four seasons in four directions can be traced in part to fūsui (Ch. feng shui) geomancy, which was imported from China and Korea and which lay behind Nara-and Heian-period urban planning. Fūsui (literally, “wind and water”) was based on the belief that the land contained vital forces that had to be secured for the prosperity of the residents. The ideal terrain had a mountain to the north, hills to the east and west, and a plain facing the sea or a river to the south. The imperial capitals of Fujiwara (694–710), Heijō (Nara [710–784]), and Heian (Kyoto [794–1868]) and the first shogunate capital of Kamakura (1192–1333) were constructed to meet these requirements.24

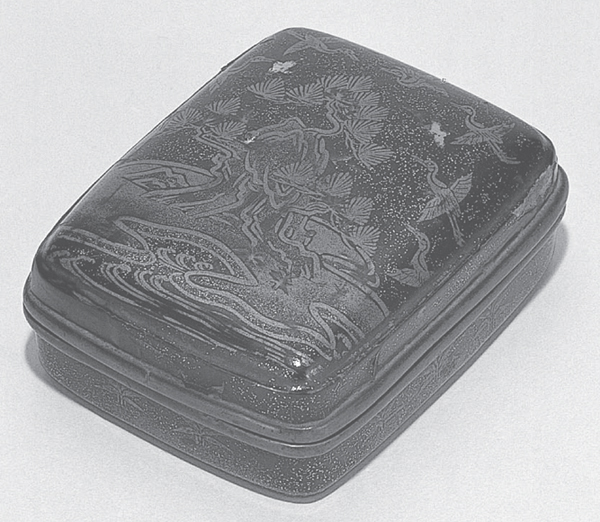

MOUNT HŌRAI WITH COVES, CRANES, AND PINES

The design on this black lacquer incense container (thirteenth or fourteenth century) depicts Mount Hōrai—the legendary island in the sea where immortals live—surrounded by a winding cove beach, covered with pines, and populated by cranes. Similar talismanic configurations appear in Heian-period island stands, in medieval rock-and-sand gardens, and in medieval and Edo-period screen paintings. (Black lacquer, with mother-of-pearl inlay and gold flakes; 3.1 × 2.4 × 1.2 inches. Courtesy of the Suntory Museum of Art, Tokyo)

The practice of fūsui revolved around four guardian gods (shijin sōō), who stood in the four directions and corresponded to the four seasons:25

Black Tortoise / North / Winter

| White Tiger / West / Autumn |  | Blue Dragon / East / Spring |

Scarlet Bird / South / Summer

According to the Sakuteiki (Record of Garden Construction, 1040), attributed to Tachibana Toshitsuna (1028–1094), the water that comes from the house and flows east is called the Blue Dragon (Seiryū).26 The road that goes west is called the White Tiger (Byakko). The lake to the south is called the Scarlet Bird (Shujaku). The hill to the north is called the Black Tortoise (Genbu). In the Heian capital, the water to the east was the Kamo River, the large road to the west was San’indō, the lake to the south was Lake Ogura, and the mountain to the north was Kitayama (Northern Hills).

In the ancient period, autumn was believed to arrive from the west. Significantly, the Tatsuta River, at the foot of a canyon pass in the northwestern corner of Heijō, was the most notable autumnal poetic place (utamakura). Tatsuta’s association with autumn probably derives from the Tatsuta Shrine, whose god ruled over the wind and was thought to foster or destroy the harvest. In similar fashion Mount Sao (Saho), in the northeastern corner of Heijō, was the home of the goddess of spring, Saohime (Princess Sao), who was worshipped at Sao Shrine at the foot of Mount Sao. In short, the gods of autumn and spring stood at the western and eastern sides of the capital, which eventually became the poetic places for these seasons.

The fūsui-based garden design of spring in the east, summer in the south, autumn in the west, and winter in the north became a cultural ideal, as suggested by court tales such as Utsuho monogatari (The Tale of the Hollow Tree, 980), The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari, early eleventh century), and Eiga monogatari (Tales of Splendor and Glory, ca. 1028–1092?). The “Koma kurabe” (Comparing Horses) chapter of Eiga monogatari, a historical narrative of the life of the regent Fujiwara no Michinaga, describes the garden of the Kaya-no-in Palace, which was reconstructed in 1019 by Fujiwara no Yorimichi. The garden is laid out “so that one can see the four seasons in four directions.”27 The “Fukiage” chapter of Utsuho monogatari similarly describes a mansion constructed by Tanematsu of Kaminabi-in with gardens in four quarters: the spring garden (east) has hillocks, the summer garden (south) has shade, the autumn garden (west) has thickets of trees, and the winter garden (north) has a pine forest.28 The most famous variation on the fūsui model is the Rokujō-in in The Tale of Genji, the grand residence built by the Shining Genji at his political apex to house his most important women: Lady Murasaki (Lavender), who was discovered by Genji in the spring, is placed in the spring quarters (to the southeast); Akikonomu (One Who Loves Autumn) lives in the autumn quarters (to the southwest); Hanachirusato (Village of Scattered Flowers) resides in the summer quarters (to the northeast); and the Akashi lady inhabits the winter quarters (to the northwest). Genji’s most treasured woman (Murasaki) occupies the spring quarters, and the most publicly important woman (Akikonomu) occupies the autumn quarters. The Rokujō-in does not strictly follow the seasonal-directional correspondences found in the Sakuteiki and other fūsui-based models, but it is close: the summer garden is shifted one and a half quarters and the three other seasons deviate by only half a quarter.

When the protagonist of a Muromachi tale visits a utopian world, he or she usually comes to a place where the four seasons exist simultaneously in the four directions, as in the widely disseminated “Urashima Tarō.” In one of the popular versions of this tale, a turtle that Urashima Tarō caught and freed appears to him as a beautiful woman, takes him to the Dragon Palace (Ryūgūjō), and persuades him to become her husband. The Dragon Palace, which is the equivalent of the Eternal Land or Mount Hōrai,29 appears under the sea:

When one opened the door to the east, spring appeared. The plum and cherry trees were blooming in profusion, the branches of the willow tree bent in the spring wind, and from the midst of the spring mist, one could hear the voice of the bush warbler near the eaves. Flowers were blooming everywhere in the trees.

When one looked to the south, summer appeared. In a hedge separated from spring, the deutzia flowers were no doubt blooming. The lotus in the lake was covered with dew, and numerous waterfowl played amid the cool ripples. As the tips of the various trees grew thick, the voice of the cicada cried in the sky, and amid the clouds that followed an evening shower, the small cuckoo sang, announcing summer.

In the west, autumn appeared. Everywhere the leaves of the trees were turning bright colors, and there were white chrysanthemums in the bamboo fence. The bush clover at the edge of the mist-filled meadow parted the dew, and the lonesome voice of the deer told us that this was autumn.

When one gazed to the north, winter appeared. The treetops in all directions had withered in the cold, and there was the first dew on the dried leaves. At the entrance to the valley where the mountains were buried in white snow, the smoke was rising in lonely fashion over the charcoal ovens, clearly revealing the lowly work of the men making charcoal and telling us that this was winter.30

Moving from spring to summer to autumn to winter, each paragraph weaves together the representative poetic topoi for the season in 5 / 7 syllabic waka-esque rhythm. Spring appears in the east, summer in the south, autumn in the west, and winter in the north, with a lake in the south and mountains in the north, as they would at a Heian-period palace-style residence.

Similar scenes appear in other Muromachi tales, such as “Kochō mono-gatari” (Tale of the Butterfly), “Shuten dōi” (Drunken Child), “Shaka no honji” (Story of Buddha), “Jōruri jūnidan sōshi” (Tale of Lady Jōruri), “Suehiro monogatari” (Tale of the Open Fan), “Tanabata” (Star Festival), “Tamura no sōshi” (Tale of Tamura), and “Suwa engi goto” (Divine Origins of the Suwa Shrine).31 In contast to Heian court tales, such as Utsuho monogatari and The Tale of Genji, which describe a kind of ideal on Earth, Muromachi tales offer other worlds (ikyō) in which the four-seasons—four-directions garden or residence signals the cessation or perpetual renewal of time. The garden becomes a utopian world, a poetic variation on the Eternal Land (Tokoyo no kuni), Mount Hōrai (Hōrai-san), Land of the Immortals (Senkyō), Dragon Palace (Ryūgūjō), Pure Land (Jōdo), and/or Tao Yuanming’s Peach Blossom Spring (Ch. Tao hua yuan, Jp. Tōgenkyō).

Tokuda Kazuo has argued that in the Muromachi period, the four-seasons—four-directions theme had a celebratory, supplicatory function. For example, folk dances and songs on the four seasons in the four directions prayed for the prosperity of a residence or family.32 In the sixteenth-century genre of screen painting called rakuchū rakugaizu (scenes in and around Kyoto), the capital is portrayed in a similar, celebratory order: the eastern part in spring, the southern part in summer, the western part in autumn, and the northern part in winter—with annual observances represented to match each season and each place. The Gion Festival, for example, appears in summer in Shimogyō, southern Kyoto. These screen paintings, which fuse the traditions of four-season painting (shiki-e) and famous-place painting (meisho-e), implicitly commemorate the capital as an ideal space.

Similar seasonal-directional paintings appear on the sliding doors in the Daisen’in and Jukōin of the Daitoku-ji monastery. For example, in the “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang” (Shōshō hakkei) panels by Kano Shōei (1519–1591) in the Jukōin, the wintry scene “Evening Snow” is found at the northern end of the room, while “Autumn Moon over Lake Dongting” is set on the western side.33 The prominent Muromachi popular tale “Jōruri jūnidan sōshi” contains a passage describing a four-seasons—four-directions other world represented on a screen painting that is viewed from right to left—from spring to summer to autumn to winter.34 This convention of depicting the otherworld with four simultaneous seasons continued through the Edo period and into the present. For example, Asanoshin, the protagonist of Hiraga Gennai’s novel Furyū shidōken (Modern Life of Shidōken, 1763), goes to a peach-blossom grove and then to a place where the four seasons coexist. In the twenty-first century, a four-season—four-directions garden appears in the Japanese anime film Spirited Away (Sen to chihiro no kamikakushi, 200i) by the director Miyazaki Hayao.

Many of the talismanic and auspicious motifs in early Japanese aristocratic culture came from China. For example, the plum tree, which originated in China, was long admired for its elegant flower and its ability to bloom early, in the cold of winter, showing strength and endurance. In the Song period (960–1279), it was grouped with the pine, which remains green throughout the year, and bamboo, which puts forth leaves even in winter, to form a painting topic dubbed the “Friends of the Cold” (saikan sanyū), which implied fidelity and fortitude. Together with the chrysanthemum, orchid, and bamboo (all of which can survive wind, frost, snow, and ice), the plum was also considered one of the “Four Gentlemen” (Jp. shikunshi) Ch. si junzi), which, from the Song period, were used to represent the purity and nobility of the virtuous (Confucian) scholar-gentleman. In Japan from as early as the time of the Manyōshū, the plum also took on a more characteristically Japanese role as a seasonal marker.35 In this capacity, which came to the fore in Heian-period imperial waka anthologies and scroll paintings, the main function of the plum blossom was as a representative of the late-winter and early-spring landscape, where it was combined with snow and the bush warbler. A broad shift from a Sino-centric view of horticulture to one that was more native in orientation is often seen in the transition from the plum blossom, which was the most popular poetic flower in Japan in the eighth century, to the cherry blossom, which overtook the plum blossom in popularity in the ninth and tenth centuries. But while the cherry blossom surpassed the plum blossom in popularity in Japan, both continued to be regarded as the premier flowers of spring—the former for mid- to late spring and the latter for early spring. In waka and Yamato-e (Japanese-style painting), the plum functions primarily as a seasonal motif, one that often has soft, if not erotic, overtones. But in Chinese-inflected genres such as kanshi, Muromachi-period Chinese-style (kanga) screen painting, and Edo-period literati (bunjin) painting, in which the focus is often on its fortitude or its strong trunk and branches, the plum took on a moral dimension—of strength, resilience, purity, and fidelity—as well as a talismanic role.

Other plants, such as the chrysanthemum (kiku) and mandarin orange (tachibana), also developed multiple dimensions. The chrysanthemum became a major icon of autumn in the Heian period, but it was also closely identified with immortality, purity, and the imperial house. Even the cherry blossom, often used to symbolize ephemerality, could also function as an image of eternal splendor and glory. The ability of flowers and trees to acquire both seasonal and talismanic dimensions was often a key to their role in a wide variety of cultural activities, particularly celebratory and ritual observances. Furthermore, these two qualities were often combined in poetry and traditional arts, such as flower arrangement (ikebana), the tea ceremony (chanoyu), and noh. Standing-flower (rikka) arrangements, for example, typically combined an evergreen, which functioned as the vertical center (shin), with a seasonal flower as the support (tai) or horizontal augmentation (soe). In waka, the image of the wisteria (spring) wrapped around a pine symbolizes the relationship of the Fujiwara (literally, “wisteria fields”) family to the imperial throne (eternal pine).

Buddhist iconography also made use of seasonal, trans-seasonal, and talismanic natural images. The most important of these was the lotus flower, iconographically the seat for the meditating Buddha, which symbolizes enlightenment or purity amid the mud of the surrounding pond or swamp. The peony (botan) was thought appropriate as a flower offering to the Buddha, and the peacock (kujaku) was believed to play in the garden of the Pure Land—two associations probably imported from China. A native set of beliefs emerged in association with cherry blossoms and autumn grasses. Cherry blossoms in full bloom were considered to be intoxicating and to draw the adherent’s spirit into the world of the gods and buddhas. When the cherry blossoms bloomed at Mount Fudaraku (variously thought to exist in southern India; in China; and in Japan, to the south of Mount Nachi, in present-day Wakayama Prefecture), the distance to the Pure Land was believed to disappear, and this world became that world. If the believer also saw autumn grasses, a vivid reminder of the evanescence of this world, his or her spirit could achieve peace and move toward enlightenment and transcendence.36

A key to understanding the talismanic function of nature can be found in the historical roots of ikebana. In Buddhist sutras of the Pure Land, the heavenly sphere is often depicted as a place filled with flowers. The interiors of Buddhist temples were decorated with flowers to replicate the heavenly sphere in this world, and flowers were offered, together with candles and incense, to the image of the Buddha—one practice from which the art of ikebana may have derived.37 At the same time, flowers were believed, from the ancient period in Japan, to embody or transmit the power of the gods (kami), who were thought to reside in nature. In annual observances and festivals, flowers, pines, and their representations were used to celebrate or placate the spirits of local gods.38 The gate pine (kadomatsu), set up at the entrance of a house on New Year’s Day, was originally believed to be the place where a god descended to Earth; it served as a greeting to the god, who was also welcomed in the alcove of the parlor-style (shoin-zukuri) residence. In short, in both Buddhist rituals and the worship of gods, icons of nature, particularly flowers, served not only as a reminder of the ephemerality of the world, but as a medium for the manifestation of the buddhas and gods, who could ward off disease and impermanence. These beliefs coexisted with various Chinese and Japanese talismanic traditions that made the ritualistic representation of nature a widespread and long-lasting cultural phenomenon and that played a major role in annual observances.