The Scrolls and Christianity

CHAPTER 4

The Dead Sea Scrolls made available for the first time a corpus of literature in Hebrew and Aramaic from Judea around the turn of the era—from the time of Jesus of Nazareth. Much of the fascination that the Scrolls have held for the general public has arisen from the possibility that they might contain information pertinent to the career of Jesus that had been hidden, or perhaps suppressed, for nearly two thousand years. In the first decade or so after the discovery, scholarship on the Scrolls was preoccupied with their relevance to the New Testament. The exclusion of Jewish scholars from the official editorial team undoubtedly contributed to the imbalance of scholarship in this period, but it was inevitable that there would be great interest in whatever light these texts might shed on the origins of what would become the dominant religion of the Western world.

The stakes in the scholarly debate were construed in various ways. Scholarship on the New Testament had tended to view Christianity as a movement that took its decisive form when it moved beyond Judaism, into the Gentile, Hellenistic world. So, for example, it was thought that the belief that Jesus was the Son of God, or even God in some sense, could not have arisen in a Jewish context, but only in a pagan environment. Christian scholars often emphasized the novelty and even uniqueness of Christianity, and the boldness of its departure from Jewish precedents. The Scrolls provided an opportunity to test these assumptions against a substantial body of primary evidence from the Judaism of the time.

It was obvious from an early point that there were some significant analogies between the sectarian movement described in the Scrolls and the early church. Both were associations, with provision for admission and expulsion of members. Both practiced ritual washing in some form. Both had common meals and, at least in some cases, common possessions. Both had strong eschatological beliefs that the end of history was at hand, and expected the coming of a messiah or messiahs.

Some scholars tended to exaggerate these analogies. In extreme cases, a few scholars have even claimed that the Scrolls provide “nothing less than a picture of the movement from which Christianity sprang in Palestine,” or rather “a picture of what Christianity actually was in Palestine.”1 Most were more moderate than that, but still there was endless fascination with the possibility that Jesus, or John the Baptist, might have known the Scrolls or the people they describe, and been influenced by them. Some pounced gleefully on similarities between the Scrolls and the New Testament, and inferred that Christianity was a derivative phenomenon, whose main insights were anticipated by another Jewish sect a century earlier. Others saw the points of continuity with the Scrolls as evidence that Christianity was indeed rooted in the Judaism of its day, and not a product of Hellenistic syncretism. It could therefore be viewed as an integral part of a tradition of divine revelation, going back to Mount Sinai, and as an authentic continuation of biblical tradition. In fact, it is difficult to say that the Scrolls have any bearing on the legitimacy or authenticity of Christianity, which depends on the acceptance of, or faith in, certain claims about Jesus (that he rose from the dead, and was Son of God in a unique sense) that cannot be either verified or falsified historically. Scholars have always known that Christianity began as a Jewish sect, and was influenced by Jewish traditions in manifold ways. But while the arguments about the authenticity and originality of Christianity may not have much rational force, they carry emotional power, and so the Scrolls have often been invested with theological importance that goes beyond logic and rationality.

Jesus and the Teacher, Phase One

The first scholar to argue for far-reaching analogies between the Scrolls and the New Testament was André Dupont-Sommer, a prominent French expert in semitic languages, who was also an early champion of the Essene hypothesis. In a communication to the Académie des Inscriptions in Paris on May 26, 1950, he invoked Renan’s famous statement that Christianity was an Essenism that largely succeeded, and Essenism a foretaste of Christianity. He continued: “Today, thanks to the new texts, connections spring up from every side between the Jewish New Covenant, sealed in the blood of the Teacher of Righteousness in 63 BC and the Christian New Covenant, sealed in the blood of the Galilean Master around A. D. 30. Unforeseen lights are shed on the history of the Christian origins.”2

Dupont-Sommer’s view depended in large part on his interpretation of the Pesher or Commentary on the prophet Habakkuk, which was one of the first Dead Sea Scrolls to come to light in 1947. This commentary interpreted the prophecies of Habakkuk with reference to events in Judean history in the first century BCE, culminating in the Roman conquest of Jerusalem under Pompey. It must have been written around the middle of the first century BCE, or a little later. It also refers repeatedly to a figure called “the Teacher of Righteousness,” who also appears in the Damascus Document. The righteous had been wandering like blind men until God raised up the Teacher to guide them in the way of his heart. In the Pesher on Habakkuk, the Teacher appears as a prophetic figure, to whom the true meaning of prophecy was revealed and whose words were from the mouth of God. He was not accepted, however, by the High Priest of the time, who is called “the Wicked Priest” in the Pesher.

The confrontation between the Teacher and the Wicked Priest is described in a controversial passage in column 11. The passage begins by quoting Hab 2:15:

Woe to him who causes his neighbor to drink, who pours out his fury (upon him) till he is drunk, that they may gaze on their feasts!

The commentary follows:

The explanation of this concerns the Wicked Priest who persecuted the Teacher of Righteousness, swallowing him up in the anger of his fury in his place of exile. But at the time of the feast of rest of the Day of Atonement he appeared before them to swallow them up and to cause them to stumble on the Day of Fasting, their Sabbath of rest.

Dupont-Sommer insisted that the verb “to swallow” meant, in this instance, “to kill.” He also argued that the Teacher then appeared, after his death, to swallow the Wicked Priest. In this way, he saw a parallel between the Teacher and Jesus, who had also been subjected to a violent death and who was expected to return to destroy the wicked.

“Everything in the Jewish New Covenant,” wrote Dupont-Sommer, “heralds and prepares the way for the Christian New Covenant. The Galilean Master, as He is presented to us in the writings of the New Testament, appears in many respects as an astonishing reincarnation of the Teacher of Righteousness.”3 The Teacher, like Jesus, was the Messiah. He had been condemned and put to death, but he would return as the supreme judge. In the meantime, he too left a “church,” supervised by an overseer or “bishop,” and whose essential rite was the sacred meal.

Few scholars, either then or later, saw the similarities between Jesus and the Teacher as being as extensive as did Dupont-Sommer. The evidence that the Teacher was condemned and put to death, or that he was expected to come again, is extremely dubious, to say the least. It is not clear that “swallowing” means “killing,” and nearly all scholars agree that it was the Wicked Priest who “appeared” before the Teacher, disrupting his observance of the Day of Atonement. Dupont-Sommer defended, but also qualified, his views in several publications over the following decade. He insisted that he had never dreamt of denying the existence or the originality of Jesus. But the publicity surrounding his initial lecture and subsequent publications came at a price. Neither he nor any of his students was invited to join the international editorial team organized by Roland de Vaux, although he was eminently qualified. Moreover, his idiosyncratic reconstruction of the Teacher’s death and supposed resurrection would reverberate through later scholarship for decades to come.

Dupont-Sommer also advanced another thesis that would continue to engage scholars more than half a century later. He held that both the Teacher and Jesus were modeled on the figure of the Suffering Servant, as found especially in the book of Isaiah, chapter 53. Of this figure it is said:

Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases …

He was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the punishment that made us whole,

and by his bruises we are healed. (Isaiah 53:4–5)

“Defining the mission of Jesus as prophet and savior,” wrote Dupont-Sommer, “the primitive Christian Church explicitly applied these Songs of the Servant of the Lord to him; about a century earlier, the Teacher of Righteousness applied them to himself.”4 In this case, he could point to several passages in the Hodayot, or Thanksgiving Hymns, in which the speaker refers to himself as “thy servant.” Many scholars have assumed that these hymns, or at least a cluster of them, were composed by the Teacher. In any case, even if the Hymns do model the Teacher on the Servant, it is not clear just what that entails. In Christian tradition, to say that Jesus is the Servant means not only that he suffered and was exalted but that he died for the sins of others. It is not at all clear that the “servant” in the Hodayot is thought to suffer vicariously in this way, or that he undergoes a sacrificial death. Nonetheless, the influence of the “Servant” passages in Isaiah remains a controversial issue.

Dupont-Sommer’s views were taken up a few years later by the literary critic Edmund Wilson in a best-selling book, which originated in articles in the New Yorker magazine. Wilson was a perceptive observer, and one of the pleasures of his book lies in the sketches he provides of the leading characters. (He noted that de Vaux “does not in the least resemble any of the conventional conceptions of a typical French priest,” and had “style, even dash.”)5 He recognized that the views of Dupont-Sommer were overstated. Nonetheless, he wrote, “if we look now at Jesus in the perspective supplied by the scrolls, we can trace a new continuity and, at last, get some sense of the drama that culminated in Christianity … The monastery [of Qumran] … is, perhaps, more than Bethlehem or Nazareth, the cradle of Christianity.”6 Wilson suggested that the scholars working on the Scrolls were “somewhat inhibited in dealing with such questions by their various religious commitments.” He was not speaking only of the official editorial team, several of whom were Catholic priests. He suggested that there could be found among Jewish scholars “a resistance to admitting that the religion of Jesus could have grown in an organic way … out of one branch of Judaism,” while among Christians there was fear “that the uniqueness of Christ is at stake.”7

The fire of this controversy was fanned by three short radio broadcasts on the BBC Northern Home Service, in January 1956, by John Marco Allegro, a member of the editorial team. Allegro claimed that “recent study of my fragments has convinced me that Dupont-Sommer was more right than he knew.”8 Allegro pointed to another biblical commentary from Qumran, on the prophet Nahum, which was assigned to his lot. The commentary, or pesher, refers to a “lion of wrath” who “hangs men alive.” This is usually taken as a reference to the Jewish king Alexander Jannaeus, who crucified hundreds of his enemies in the early first century BCE (Josephus, Ant 13.380; Jewish War 1.97). Allegro identified Jannaeus as the Wicked Priest, the adversary of the Teacher of Righteousness. He then inferred that the Teacher was one of the people crucified. “Most remarkable of all,” he said, “is the manner of his death, and the significance attributed by his disciples to its consequences.” He continued:

Probably hardly a decade after they had established themselves in their simple buildings at Qumran, the terrible Jannaeus, the Wicked Priest as they called him, stormed down to their new home, dragged forth the Teacher, and as now seems probable, gave him into the hands of his Gentile troops to be crucified. Already in Jerusalem this Jewish tyrant had displayed his bestiality by inflicting the same awful death on eight hundred rebels, and a Qumran Manuscript speaks in shocked tones of the enormity of this crime. For to a Jew, this death was the most accursed of all, since the body normally found no resting place but was left to moulder on the cross.

But when the Jewish king had left, (the sectarians) took down the broken body of their Master to stand guard over it until Judgment Day … In that glorious day, they believed their Master would rise again and lead his faithful flock (the people of the new testament, as they called themselves) to a new and purified Jerusalem.9

This broadcast caused an uproar. The New York Times published his views on February 5, 1956, under the heading “Christian Bases Seen in Scrolls.” Time magazine followed on February 6 with an article entitled “Crucifixion before Christ.” Allegro’s colleagues on the editorial team were moved to respond. On March 16, 1956, a letter appeared in the Times of London signed by de Vaux, Milik, Skehan, Starcky, and Strugnell (all but the latter of whom were Catholic priests). They wrote:

We are unable to see in the texts the “findings” of Mr. Allegro. We find no crucifixion of the “teacher,” no deposition from the cross, and no “broken body of their Master” to be stood guard over until Judgment Day. Therefore there is no “well-defined Essenic pattern into which Jesus of Nazareth fits,” as Mr. Allegro is alleged in one report to have said. It is our conviction that either he has misread the texts or he has built up a chain of conjectures which the materials do not support.10

Frank Moore Cross’s name did not appear in the list of signatories, but he wrote privately to Allegro:

Unless you have new data, which I have not seen in the pNah [pesher or commentary on Nahum], and which I am told via Jerusalem is not in the infamous Copper Document, you will have one hell of a time convincing me. If you have new data, I’ll convince in a minute.11

Allegro did not have new data, and most scholars found his interpretation of Pesher Nahum unconvincing. He seems to have convinced himself, however, that he was being victimized by a conspiracy of Catholic clerics, intent on hiding the truth, despite the fact that Cross and Strugnell were Presbyterians. The controversy subsided. Allegro went on to commit definitive academic suicide by publishing a “grand, unifying theory of religion” called The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross: A Study of the Nature and Origins of Christianity within the Fertility Cults of the Ancient Near East (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970). He argued that Christianity was a variant of a kind of fertility cult common in the ancient Near East, involving sacred mushrooms, but that all explicit reference to these had been deceitfully suppressed. The word Boanerges, for example, the name given by Jesus to James and John, the sons of Zebedee in Mark 3:17, was supposedly the name of a sacred fungus. Even Allegro’s most persistent (and unscholarly) defenders, such as the sensationalist British authors Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, and Allegro’s daughter Judith Anne Brown, could not accept this theory. For any educated student of religion it was simply ludicrous. As his daughter put it simply: “The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross ruined John’s career.”12

The Son of God

In a letter to de Vaux dated September 16, 1956, at the height of the controversy, Allegro wrote:

As for Jesus as a “son of God” and “Messiah” – I don’t dispute it for a moment; we now know from Qumran that their own Davidic Messiah was reckoned a “son of God”, “begotten” of God – but that doesn’t prove the Church’s fantastic claim for Jesus that he was God Himself. There’s no “contrast” in their terminology at all – the contrast is in its interpretation.13

He was referring here to two texts, the Rule of the Congregation (1QSa), and the “Son of God” text (4Q246).

1QSa is an appendix to 1QS, the Community Rule or Manual of Discipline. It had not yet been identified when the “Manual” was first published in 1951, but it was published by Dominique Barthélemy in the first volume of the Discoveries in the Judaean Desert series in 1955.14 It is a rule for the end of days. In the second column, lines 11–12, it prescribes the order for a banquet “when God begets the messiah with them.” The reading of the word “begets” (yolid) is very difficult; the published photo is practically illegible at this point. The editor noted that after careful study with a transparency, the reading seemed practically certain, but in view of the awkward preposition “with them” he accepted a suggestion of Milik that the word was a scribal error, for yolik, brought or caused to go. Other readings would later be suggested. The scholars who examined the text in the 1950s, however, agreed that it read “will beget,” whether this was a mistake or not. This reading has also been affirmed more recently on the basis of computer enhancement. The idea that God would beget the messiah has a clear basis in Psalm 2:7 and Psalm 110:3 (LXX) and so it is not especially surprising. While the reading is admittedly difficult, there are some grounds for suspecting that scholars, Jewish and Christian alike, were eager to emend it for theological reasons, because it seemed too similar to Christian ideas.

The second text to which Allegro alluded had not yet been published in 1956, although it had evidently been noted. This is an Aramaic text, 4Q246, officially called “Aramaic Apocalypse,” but better known as “the Son of God” text. This was not made known to a wider public until December 1972, when J. T. Milik presented a lecture on the topic at Harvard University. It aroused great interest because some of its language is closely paralleled in the Gospel of Luke.

The text consists of two columns. The first is torn down the middle, so that only the second half of the lines survives. Someone is said to fall before a throne, and there is mention of a vision. The fragmentary text continues:

affliction will come on earth … and great carnage in the provinces … the king of Assyria and [E]gypt … shall be great on earth … and all will serve … he shall be called, and by his name he shall be named.

The second column continues:

Son of God he shall be called, and they will name him “Son of the Most High.” Like shooting stars which you saw, so will their kingdom be. For years they will rule on earth, and they will trample all. People will trample on people and city on city until the people of God arises and all rest from the sword. His (or its) kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and all his ways truth. He will judge the earth with truth, and all will make peace. The sword will cease from the earth, and all cities will pay him homage. The great God will be his strength. He will make war on his behalf, give nations into his hand and cast them all down before him. His sovereignty is everlasting sovereignty, and all the depths …

This text immediately brings to mind the story of the Annunciation in the Gospel of Luke. There the angel Gabriel tells Mary:

And now you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David. He will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end. Mary said to the angel, “How can this be, since I am a virgin?” The angel said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God.

While the Gospel is in Greek and the new text is in Aramaic, the correspondence of several phrases is striking: “will be great,” “Son of the Most High,” “Son of God.” Both texts speak of everlasting dominion.

Allegro evidently assumed that the Aramaic text referred to the Davidic messiah, a position that Frank Moore Cross is also known to have shared from an early point. Milik, however, argued that the figure who is called Son of God was not a Jewish messiah, but rather a Syrian king, probably Alexander Balas, a second-century BCE ruler who referred to himself on his coins as theopator, divinely begotten. The idea that the king was a negative figure relied on the assumption that a blank space before “until the people of God arises” marked a transition point in the text. Since the “Son of God” appears before this transition point, the argument goes, he is grouped with the enemies of God. In fact, apocalyptic texts seldom proceed in a simple unilinear manner, and so this argument is dubious. In any case, it must be weighed against the clear messianic usage of the titles Son of God and Son of the Most High in the Gospels. Milik’s interpretation was not well received by the Harvard audience. Perhaps for this reason, he never published the text. Part of the text was published on the basis of Milik’s handout, by Joseph Fitzmyer S. J., in 1974.15 (Fitzmyer, a Jesuit priest, was evidently not suppressing the text for doctrinal reasons!) The official publication, by Émile Puech, did not follow until 1992.16 Only at that point was it picked up by the popular media. Newspapers from London to Los Angeles trumpeted: “Son of God among the Dead Sea Scrolls!” suggesting that this had grave implications for Christianity.

The interpretation of this text has remained controversial. While Milik may not have won a following at Harvard, he has not lacked supporters, although some of them favor a different king (Antiochus Epiphanes, or even the Roman emperor Augustus, who was proclaimed divi filius, Son of God). Scholarship has been fairly evenly divided between those who favor the messianic interpretation and those who see this Son of God as a negative figure, even as an Antichrist. I would not want to suggest that resistance to recognizing this figure as the messiah is entirely due to theological considerations, but they have not been entirely absent. For example, Fitzmyer takes the text to be speaking positively of a coming Jewish ruler, possibly an heir to the Davidic throne, but he insists that he is not a messiah, even though he admits that a successor to the Davidic throne in an eschatological context is by definition a messiah.17 Some light may be shed on this paradoxical position by Fitzmyer’s commentary on the parallel passage in Luke. He insists that the title “Son of God” is not used of a person who is called “messiah” in the Qumran text, and therefore does not have “a messianic nuance.” He then goes on to insist that in the Gospel, “Son of God” attributes to Jesus a unique relationship with Yahweh, the God of Israel.18 In this case, at least, the uniqueness of Jesus appears to be the issue at stake.

A Dying Messiah?

When the hitherto unpublished Dead Sea Scrolls became generally available in the early 1990s, a number of other texts attracted attention. One fragmentary text related to the war in the end-time was taken to predict the death of the messiah: “and they will kill the prince of the congregation, the Branch of David.” The idea that the messiah would be put to death in the final war is attested in later Judaism, probably because of the fact that the messianic leader known as Bar Kochba was killed in the war against Rome of 132–135 CE. In the New Testament, however, it is clear that the death of Jesus came as a great shock to his followers, not as something that had been predicted. On inspection, however, this interpretation of the fragment proved to be improbable. The word translated as “they will kill” (hmytw) can also be rendered as “he will kill him,” taking the Branch of David as the subject. Since the other messianic texts from Qumran uniformly present the Davidic or royal messiah as a mighty warrior who defeats the enemy, this interpretation is to be preferred.

A Prophetic Messiah?

A better parallel to the New Testament, however, is provided by a larger Hebrew fragment designated 4Q521 and sometimes dubbed “the messianic apocalypse,” which begins: “heaven and earth will obey his messiah.” The passage goes on to say:

The glorious things that have not taken place the Lord will do as he s[aid] for he will heal the wounded, give life to the dead and preach good news to the poor.

This text brings to mind a passage in the Gospel of Matthew 11:

When John heard in prison what the Messiah was doing, he sent word by his disciples and said to him, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” Jesus answered them, “Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them.

Both the Qumran text and the Gospel draw on Isaiah 61:1, where the prophet says:

The spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me; he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives and release to the prisoners.

(This text is famously read by Jesus in the Capernaum synagogue, in Luke 4:18.) The Isaianic text does not mention raising the dead, and this suggests that the Gospel and the Qumran text had at least a further tradition in common.

In the Qumran text, it is God who is said to heal the wounded, give life to the dead, and preach good news to the poor. It is very odd, however, to have God preaching the good news: that was the work of a prophet or herald. Moreover, neither Isaiah 61 nor Matthew 11 has God as the subject. In Isaiah, the agent is an anointed prophet. The suspicion arises, then, that God is also thought to act through an agent in 4Q521, specifically, the “messiah” or anointed one whom heaven and earth obey. This messiah, however, is not a warrior king, but rather a prophetic “messiah” whose actions resemble those of Elijah and Elisha, both of whom were said to have raised dead people to life. If this is correct, then this Qumran text throws some genuine light on the career of Jesus, who certainly resembled Elijah more than a warrior king.

The expectation of a prophetic messiah appears only as a minor tradition in the Dead Sea Scrolls. 1QS 9:11 refers to “the coming of the prophet and the messiahs of Aaron and Israel,” but most of the messianic references in the Scrolls concern the Branch of David, the messianic king. (4Q521 does not appear to be a sectarian text, but may have been part of the wider Jewish literature preserved in the Scrolls.) Jesus, however, does not seem well qualified for the role of warrior king in his earthly career. The possibility that he may first have come to be regarded as a messiah in the role of messianic prophet is intriguing. There are in fact indications in the Gospels that some people, at least, associated Jesus with Elijah. In Mark 6:14–15 various people identify Jesus to Herod as John raised from the dead, Elijah, or “a prophet.” Again in Mark 8:28, when Jesus asks “who do people say that I am?” he is told: “John the Baptist, and others, Elijah, and still others, one of the prophets.”

Jesus and the Teacher, Phase Two?

The idea that the Teacher of Righteousness had applied to himself the passages about the suffering servant of the Lord in the Book of Isaiah, and thereby anticipated Jesus, was put forward in the early days of Scrolls research by Dupont-Sommer. It was revived in 1999 by Michael Wise, in a book entitled The First Messiah. Investigating the Savior Before Christ (San Francisco: Harper). In this case, the argument did not depend on newly published texts, but on the Hodayot, or Thanksgiving Hymns, which were among the first batch of Scrolls acquired by Sukenik in 1948. In the time between the work of Dupont-Sommer and that of Wise, the study of these hymns had been refined, by a distinction between Hymns of the Teacher and Hymns of the Community. In the Hymns of the Teacher, the speaker claims to be a mediator of revelation for others. He speaks of betrayal and rejection, and of his confidence that he will be vindicated. At least eight hymns of this type are clustered together in columns 10–17 of the Hodayot Scroll. (There is some disagreement about the precise delineation of the corpus.) These hymns have often been taken as the work of the Teacher of Righteousness, on the grounds that the sect can hardly have had more than one powerful personality of this type. Some scholars hesitate to accept this inference, and say that the hymns are formulaic, and could be applied to any member of the community. There is no doubt, however, that the speaking voice in these hymns is distinct from the rest of the Hodayot. It may never be possible to prove the authorship of these hymns without doubt, but “Teacher” here may serve as a designation for the speaker, whoever he actually was.

Wise claims that toward the end of the Teacher Hymns the Teacher came to speak of himself as the servant of the Lord in concentrated fashion, by alluding to the “servant” passages in Isaiah. He describes himself as stricken with afflictions, and forsaken, and repeatedly complains that people do not “esteem” him, using a Hebrew verb that is also used in Isaiah 53:3. He also claims to be endowed with the spirit. This claim recalls Isaiah 61: “The spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me. He has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed.” We have seen allusions to that passage also in 4Q521, which we discussed earlier.

The allusion to Isaiah 61 raises the question whether the Teacher may have been considered a messiah, perhaps the “prophetic messiah” envisioned in 4Q521. He was the one to whom God had made known all the mysteries revealed to the prophets, which the prophets themselves did not understand (Pesher on Habakkuk, col. 7). The coming of the Teacher was clearly thought to be an eschatological event, in the sense that he was ushering in the last phase of history. Neither in the hymns nor in the commentaries, however, is he ever called a messiah. Some scholars have pointed to a passage in the great Isaiah Scroll from Qumran Cave 1 (1QIsaa), to argue that the “servant” of Isaiah 53 was understood as a messianic figure at Qumran. In Isaiah 52:4, where the traditional (Masoretic) text reads, “so his appearance was destroyed (moshchath) beyond that of a man,” the Isaiah Scroll reads, “so I have anointed (mashachti) his appearance.” The difference only involves the addition of one Hebrew letter at the end of the disputed word. It must be admitted that the traditional text makes much better sense in the context, and most scholars think the reading of the Qumran text is a simple scribal mistake. It opens up the possibility, however, that someone who read the Isaiah scroll from Qumran might well have inferred that the servant was anointed, and so a messiah. But nonetheless, the fact remains that the Teacher is never called a messiah explicitly.

Even if the Teacher was understood in terms of the suffering servant, however, and even understood as a messiah, how far could he be said to have anticipated Jesus? The Teacher was understood to have undergone suffering in the course of his mission. That mission was for the benefit of others. While the servant, in Isaiah 53:11, was said to make many righteous, the Teacher claims, “through me you have enlightened the face of the many” (1QHa 12:27). But the Teacher is not said to offer his life as a ransom for many, or to suffer vicariously on their behalf. In contrast, in the New Testament we are told that “the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45), and in the epistle to the Romans 4:25 we are told that Jesus “was handed over to death for our trespasses and was raised for our justification.” The servant of Isaiah 53 was usually understood in Judaism around the turn of the era as a paradigmatic case of humiliation followed by exaltation. (There is no clear allusion before the New Testament to the idea that his death would atone for others.) Both the Teacher and Jesus were afflicted and humiliated, and would be exalted. But the most novel aspect of the use of Isaiah 53 in the New Testament, which focused on the death of the servant as atonement for the sins of others, is not anticipated in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The suffering servant appears again in a book by the Israeli scholar Israel Knohl, The Messiah before Jesus. The Suffering Servant of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). Knohl’s thesis is more far-reaching than that of Wise, and is based on a different text. This is the so-called Self-Exaltation Hymn, a fragmentary composition that survives in several copies, one of which is in a manuscript of the Hodayot. The speaker in this text also suffers contempt and rejection, but the emphasis is on his exaltation. The speaker boasts: “I am reckoned with the gods, and my dwelling is in the holy congregation,” and that “there is no teaching comparable [to my teaching].” He speaks of a mighty throne in the council of the gods, and says that he has taken his seat in heaven. He boasts that his glory is with the sons of the king (= God), that he is a companion of the holy ones, and he even asks “who is like me among the gods?”

There is no agreement among scholars as to who the speaker in this text might be. Suggestions range from the Teacher of Righteousness to the eschatological High Priest. None of the Teacher Hymns makes such exalted claims for the speaker. In contrast, they have an acute sense of human unworthiness that is lacking in this composition. Another suggestion, that this hymn was put on the lips of the Teacher after his death, might allay this problem somewhat. The suggestion that the speaker is an eschatological figure is also hypothetical. We have no parallel for such claims by a messianic figure.

In Knohl’s view, the speaker was a leader of the Qumran sect who saw himself as the messiah, and was recognized as such by his followers. Specifically, he identifies the sectarian leader as Menahem the Essene, who is said to have ingratiated himself to Herod by predicting that he would become king when he was still a boy. (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 15.372–79.) While Knohl recognizes that “friend of the king” means “friend of God” in the hymn, he thinks that the choice of this language suggests that the speaker was also a friend of the human king of the day. He infers that he is the messiah, because in Psalm 110 the king messiah is invited to sit at the right hand of God. The references to suffering suggest that he is also the suffering servant. Since the Damascus Document says that the messiah of Aaron and Israel will atone for the sins of Israel, Knohl infers that the speaker in this hymn believed that his sufferings had atoning power. It is already obvious that this argument involves several intuitive leaps that are not required by the fragmentary evidence. Whether the figure in question is either messiah or servant is not beyond dispute. For Knohl, however, this text is evidence that the association of the messiah with the suffering servant was not an innovation of early Christianity, but had already been made by this Jewish “messiah” a generation or so before the time of Jesus.

Knohl, however, goes further. In the Book of Revelation, chapter 11, John of Patmos has a vision in which two “witnesses” prophesy. They are identified as the two olive trees mentioned in a prophecy of Zechariah (chapter 4), and can therefore arguably be called “messiahs” (evidently, prophetic messiahs rather than royal ones). In the vision, they are killed by a beast that comes up from the bottomless pit. Their bodies lie in the street for three and a half days. Then the breath of life enters into them, they come back to life and are taken up to heaven. The Book of Revelation is a Christian composition, written toward the end of the first century CE. The death and resurrection of the witnesses is usually thought to be modeled on that of Jesus. Knohl argues, however, that it reflects an historical incident in 4 BCE, when Roman soldiers suppressed a revolt after the death of King Herod. (At the beginning of the vision, John is told to measure the temple but not the outside court, “for it is given over to the nations.” The Roman soldiers in 4 BCE penetrated the courtyard of the temple but not the temple itself.) Since the copies of the “self-exaltation hymn” all date from the time of Herod, Knohl infers: “One can therefore assume that one of the two Messiahs killed in 4 BCE was the hero of the messianic hymns from Qumran.”19 So, he concludes, not only was the idea of a messianic suffering servant current before Jesus, but so was the belief that a messiah was raised after three days and exalted to heaven.

All of this argument involves huge intuitive leaps that go far beyond the available evidence. Knohl subsequently claimed to find confirmation of his theory in another controversial text, The Vision of Gabriel. This is a Hebrew text of some eighty-seven lines, written in ink on a slab of grey limestone. How exactly it was found is unknown, but it is alleged to come from the area east of the Dead Sea, and to have been discovered about the year 2000. It has sometimes been called “a Dead Sea Scroll on stone,” but it is not part of the corpus of manuscripts found near Qumran. Its authenticity has not been challenged, although some doubts are inevitable in view of the uncertainty of its provenance. On the basis of the writing and the Hebrew it is thought to date from around the turn of the era.

The fragmentary text seems to be a speech of the angel Gabriel, promising imminent deliverance. It refers to David, at least twice. As Knohl reads it, it also refers to Ephraim, whom he takes to be another messianic figure known from later Jewish tradition. Other scholars read a different word instead of Ephraim. Crucial to Knohl’s interpretation is another line, which he reads as “after three days, live.” He infers that the messiah Ephraim would die and be raised after three days. The spelling of the word “live” is admittedly unusual:  (the word “live” does not normally have an aleph in the middle). Other scholars suggest that the word should be read as

(the word “live” does not normally have an aleph in the middle). Other scholars suggest that the word should be read as  , “the sign” (a word that occurs elsewhere in the text). So it is, to say the least, very uncertain that this text refers to resurrection, or indeed to a messiah Ephraim. Here again Knohl makes imaginative leaps to reach provocative conclusions, but very few scholars find his work persuasive.

, “the sign” (a word that occurs elsewhere in the text). So it is, to say the least, very uncertain that this text refers to resurrection, or indeed to a messiah Ephraim. Here again Knohl makes imaginative leaps to reach provocative conclusions, but very few scholars find his work persuasive.

What is at stake in this debate? It is, of course, entirely possible in principle that central affirmations of Christianity were derived from earlier Jewish ideas. The idea of a messiah is unequivocally Jewish. So is the idea that the messiah can be called “Son of God,” despite the evident discomfort of some scholars on this point. The poems of the suffering servant in Isaiah were known, and used in various ways to express the experience of the suffering righteous, before the time of Jesus. Even the idea of resurrection after three days may have been prompted by a passage in the prophet Hosea, where certain Israelites in a time of distress express the hope that “after two days he will revive us; on the third day he will raise us up that we may live before him” (Hosea 6:2). But the evidence that a messianic figure before Jesus was construed as the suffering servant, and believed to have been raised from the dead after three days, is flimsy at best. Yet the attempt to find an exact prototype for Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls has fascinated people repeatedly for more than sixty years. The fascination of this mirage is obviously theological or ideological, but its implications are not at all clear: if Knohl were right, would this undermine the credibility of Christianity? or enhance it by showing that such ideas were grounded in Judaism? would it redound to the glory of Judaism, by showing the Jewish origin of influential ideas? or would it tarnish that glory by showing that some of the more “mythological” aspects of Christianity were at home in Judaism too? Or should it have any bearing on our judgments about Judaism or Christianity at all? What is clear is that the desire to prove, or disprove, claims that are thought to be fraught with theological significance can only distort the work of the historian.

John the Baptist

Not all debates about the Scrolls and early Christianity concern Jesus. The question whether John the Baptist was a member of “the Qumran community” has proven to be a hardy perennial in this regard. The area where John had performed his baptisms was within walking distance of Qumran. The Essenes too had attached great importance to ritual washing. Even Joseph Fitzmyer, a scholar noted for his hard-headed sobriety and stern critiques of sensationalism, has held that the idea that John was a member of the Qumran community is “a plausible hypothesis,” granted that “one can neither prove nor disprove it.”20 Fitzmyer even speculates that after the death of his elderly parents, John may have been adopted by the Essenes. Further, he claims that John’s baptism may be seen as a development of the ritual washings of the Essenes, although it has a different character in the Gospels. More recently, the association of the Baptist with the sect has been argued by James Charlesworth. Charlesworth grants that the Baptist cannot have been a member of the Essenes in the phase of his career described in the New Testament, but supposes that he had gone through much of the initiation process and then withdrawn. This thesis, claims Charlesworth, “helps us comprehend the Baptizer’s choice and interpretation of Scripture, especially Isaiah 40:3, his location in the wilderness not far from Qumran, his apocalyptic eschatology, and his use of water in preparing for the day of judgment.”21 In this case, however, the debate has not been fueled by any new texts. The basic arguments had already been refuted by Millar Burrows and Frank Cross in the 1950s. While the Baptist was surely aware of the sectarian settlement near the Dead Sea, he would hardly have been attracted to the regimented life of the community. As Burrows put it in 1955: “if John the Baptist had ever been an Essene, he must have withdrawn from the sect and entered upon an independent prophetic ministry. This is not impossible, but the connection is not so close as to make it seem very probable.”22

Structural Comparisons

The Teacher’s movement and the Jesus movement are both reasonably described as Jewish sects. The former entailed a new covenant, with a clear distinction between those who were in and those who remained outside. The Jesus movement does not seem to have been so clearly defined in the lifetime of the leader, but it was gradually institutionalized after his death. It was inevitable, then, that people would ask how the two movements might be compared.

A classic formulation of the relation between the sect of the Scrolls, identified as the Essenes, and early Christianity was provided by Frank Moore Cross in 1958. Cross maintained that “the Essenes prove to be the bearers, and in no small part the producers of the apocalyptic tradition of Judaism.”23 (They had been so regarded already in the nineteenth century, long before the Scrolls were discovered, although the Greek and Latin accounts of the Essenes give scant indication of this.) “In some sense,” wrote Cross, “the primitive Church is the continuation of this communal and apocalyptic tradition.”24 Like the Essenes, the early Church was distinctive in its consciousness of living already in the end of days. The “eschatological existence” of the early Church, then, its communal life in anticipation of the kingdom, was not a uniquely Christian phenomenon, but had an antecedent in the communities of the Essenes. Both were “apocalyptic communities.”

It is in the context of this common eschatological consciousness that the various analogies between the Scrolls and the New Testament must be seen. Nowhere were these more evident than in the Gospel and Epistles of John, in such phrases as “the spirit of truth and deceit” (1 John 4:6), “sons of light” (John 12:36), or “eternal life” (passim). The affinities of the Johannine literature with the Scrolls had already been noted by Albright, and elaborated by Raymond Brown, who wrote a classic commentary on the Gospel in the Anchor Bible series.25 For Albright and his students (including Cross and Brown) these parallels served to refute the approach of Rudolf Bultmann, who read the New Testament primarily in a Hellenistic context. “These Essene parallels to John and the Johannine Epistles will come as a surprise only to those students of John who have attempted to read John as a work under strong Greek influence,” wrote Cross.26 While he noted that there is no equivalent of the Logos (Word) in the Scrolls, and granted that the Gospel had an elaborate literary history, he concluded: “the point is that John preserves authentic historical material which first took form in an Aramaic or Hebrew milieu where Essene currents still ran strong.”27 Cross was not an especially conservative Christian, although this conclusion, like the positions of the Albright school in general, was attractive to Christians of a conservative bent. More important for Cross was the continuity between early Christianity and Judaism, which was questioned and sometimes denied in German and German-inspired scholarship. Nonetheless, the emphasis on the semitic background of the Johannine literature seems no less one-sided than the alternative Hellenistic approach.

Cross argued that this eschatological consciousness was reflected in the organizational structure of the two movements. He acknowledged from the outset that there is no counterpart in the early Church to the dominance of priests at Qumran, but he regarded the enigmatic “twelve men and three priests” mentioned in 1QS 8:1 as analogous to the twelve apostles. The office of inspector, mebaqqer or paqid, was thought to parallel the Christian episkopos, or bishop.

The boldest analogies drawn by Cross concerned “the central ‘sacraments’ of the Essene community,” baptism and the communal meal. The “baptism of the Essenes” is held to be “like that of John,” indicating repentance of sins and acceptance into the eschatological community. Whether in fact initiatory baptism in the Qumran sect was at all comparable to Christian baptism is open to question. Cross argued that the communal meal of the Essenes must be understood as a liturgical anticipation of the messianic banquet, and as such provides a closer parallel to the Christian Eucharist than the Passover meal. Here again Christian practice is taken as the heuristic key to the significance of what is described in the Scrolls, and, again, the analogy is open to question. One Scroll, 1QSa, the Rule of the Congregation, envisages a banquet when the messiah is present, but it does not necessarily follow that every common meal of the sect had eschatological overtones.

But while Cross may have viewed the Scrolls through Christian lenses in some cases, his treatment is distinguished by its sobriety, when compared with the proposals of Dupont-Sommer or Allegro. The analogies were grounded in the similar eschatological consciousness of the two groups, and in most cases did not require direct Essene influence on early Christianity.

Analogies between the two movements were carried to far greater lengths toward the end of the twentieth century, in the work of maverick scholars, such as Robert Eisenman or the Australian Barbara Thiering. Eisenman contended that the Scrolls provide “nothing less than a picture of the movement from which Christianity sprang in Palestine,” or rather “a picture of what Christianity actually was in Palestine.”28 He acknowledged that this picture is virtually the opposite of Christianity as it has come down to us, but he claimed it was transformed when Christianity spread to the Gentile world. Both stages of Christianity “used the same vocabulary, the same scriptural passages as proof texts, similar conceptual contexts; but the one can be characterized as the mirror reversal of the other. While the Palestinian one was zealot, nationalistic, engagé, xenophobic, and apocalyptic; the overseas one was cosmopolitan, antinomian, pacifistic—in a word ‘Paulinized.’ Equally we can refer to the first as Jamesian.”29 He argued that the Teacher of Righteousness was none other than James, the brother of the Lord. For Eisenman, the key to the Scrolls was provided by the coded use of Damascus in the Damascus Document. This he took as a cryptogram for Qumran. When Paul set out for Damascus to persecute the Christians there, he was really setting out for Qumran. Unfortunately, the rest of the scholarly world continues to remain blind to this insight.

Eisenman’s suggestion that the Teacher of Righteousness was James the brother of Jesus is hardly the most bizarre theory that has been put forward. An Australian scholar, Barbara Thiering, made John the Baptist the Teacher and cast none other than Jesus as the Wicked Priest.30 In fairness to Thiering, she did not suggest that Jesus actually was a “wicked priest,” only that he was so regarded by the sectarians of the Scrolls. A minor obstacle to this theory is the fact that Jesus was not a priest at all. Eisenman cast Saint Paul in this role, although Paul’s priestly credentials are likewise unattested. The theories of Eisenman and Thiering (and a few others) are noted here mainly as curiosities: the strange aberrations to which scholars have been led in their zeal to relate the Scrolls to early Christianity.

A Common Context

While the more ambitious attempts to find in the Scrolls an exact prototype of early Christianity have proved delusional, there is no doubt that the Scrolls shed light on the New Testament in many ways. The two movements overlapped in time, in the same cultural context. They used the same scriptures, and often used them in similar ways. The Scrolls provide a context for debates about such matters as divorce and Sabbath observance, which were of concern to all Jews at the time. Sapiential texts found at Qumran contrast flesh and spirit in ways similar to what we find in the Pauline letters. Another wisdom text contains a list of Beatitudes, which is similar at least in form to the Sermon on the Mount, although the details are quite different. 4QMMT, the treatise on “some of the works of the Law” that sets out the points on which the sect differed from other Jews has been invoked as a parallel for what Paul means by “works of the Law.” A document about a heavenly figure named Melchizedek provides a possible background for enigmatic references to Melchizedek in the Epistle to the Hebrews. Examples could be multiplied. Very seldom is it possible to argue that a New Testament writer was influenced by a specific text found at Qumran. The point is rather that both movements drew on the same cultural and religious tradition, and often understood their sacred texts in similar ways, or raised similar questions about them.

If we look at the Gestalt of the two movements, however, the differences are at least as striking as the similarities. As Cross argued, both movements expected the coming (or second coming) of a messiah (or messiahs) and believed that actions in this life would determine salvation or damnation in the next. The scenario envisioned in the War Scroll is not so far removed from that of the Book of Revelation. Both envisage a violent confrontation between the forces of good and those of evil, and the eventual destruction of the latter. But the kind of conduct that is thought to lead to salvation in the two movements is fundamentally different. In the Scrolls, the emphasis is on attaining and maintaining a state of purity, and this is achieved by separating from “the men of the pit,” which is to say from the rest of society. Jesus, and even more so Paul, in contrast, downplayed the importance of the ritual laws. According to Jesus, it is not what goes into a man that makes him unclean, but what comes out of his mouth. So far from separating from the world of impurity, Paul launched a mission to the Gentiles. Essenism and Christianity were different movements, with different values, even though they arose in essentially the same environment.

Further Reading

An entertaining though sensational account of the controversies surrounding the work of Dupont-Sommer and Allegro can be found in Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, The Dead Sea Scrolls Deception (London: Jonathan Cape, 1991). Allegro’s daughter, Judith Anne Brown, has written a sympathetic account of her father’s career in John Marco Allegro. The Maverick of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005). On the career of Dupont-Sommer see also André Lemaire, “Qumran Research in France,” in Devorah Dimant, ed., The Dead Sea Scrolls in Scholarly Perspective: A History of Research (STDJ 99; Leiden: Brill 2012)433–47.

The more recent controversies have surrounded the books of Michael Wise, The First Messiah. Investigating the Savior Before Christ (San Francisco: Harper, 1999) and Israel Knohl, The Messiah before Jesus. The Suffering Servant of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). For an assessment of their theories, see John J. Collins and Craig A. Evans, eds., Christian Beginnings and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2006), 15–44. See also John J. Collins, “The Scrolls and Christianity in American Scholarship,” in Dimant, ed., The Dead Sea Scrolls in Scholarly Perspective, 197–215. On the Vision of Gabriel, see now Matthias Henze, ed., Hazon Gabriel. New Readings of the Gabriel Revelation (SBLEJL 29; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011). For a comprehensive discussion of the messianic texts from Qumran see John J. Collins, The Scepter and the Star. Messianism in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls (2nd ed.: Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010).

Incisive critiques of the books of Eisenman, Thiering, and Baigent and Leigh can be found in Otto Betz and Rainer Riesner, Jesus, Qumran and the Vatican. Clarifications (New York: Crossroad, 1994) and Klaus Berger, The Truth under Lock and Key? Jesus and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 1995). Betz and Riesner also debunk the short-lived theory of José O’Callaghan that a fragment of the Gospel of Mark was found at Qumran. The fragment in question contained only one complete word (kai = “and”).

For a sober, scholarly, overview of the Scrolls and the New Testament, see Jörg Frey, “Critical Issues in the Investigation of the Scrolls and the New Testament,” in Timothy H. Lim and John J. Collins, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 517–45.

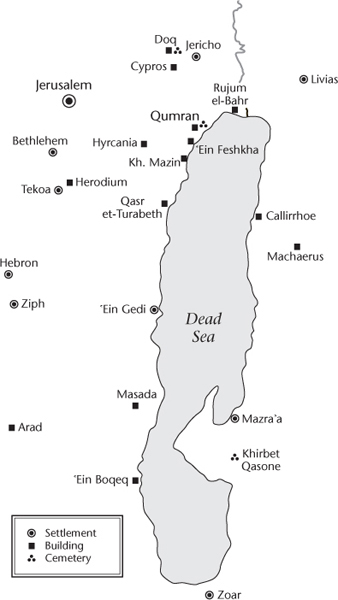

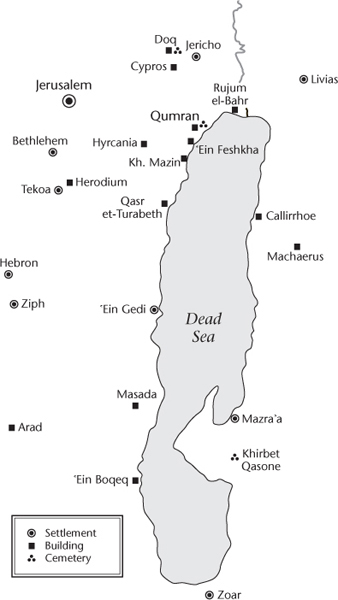

Map of the Dead Sea Region.

Redrawn from Beyond the Qumran Community,

Eerdmans Publishers.

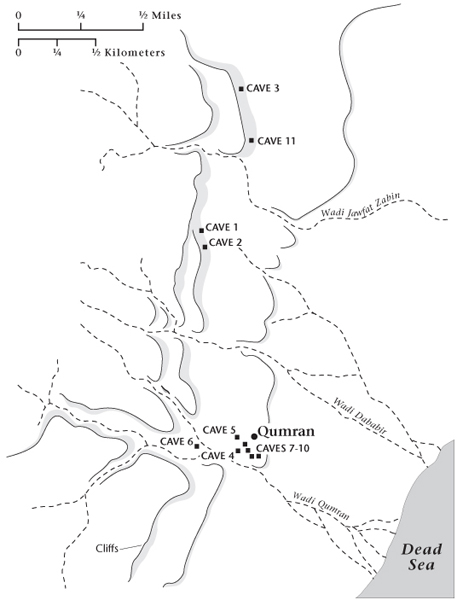

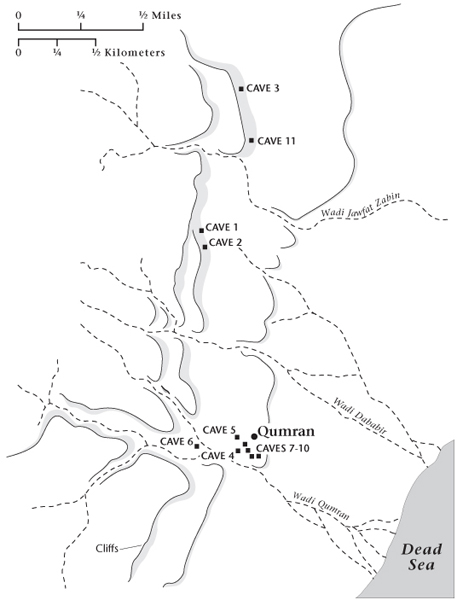

Map showing the location of Qumran Caves.

Redrawn from Beyond the Qumran Community.

Eerdmans Publishers.

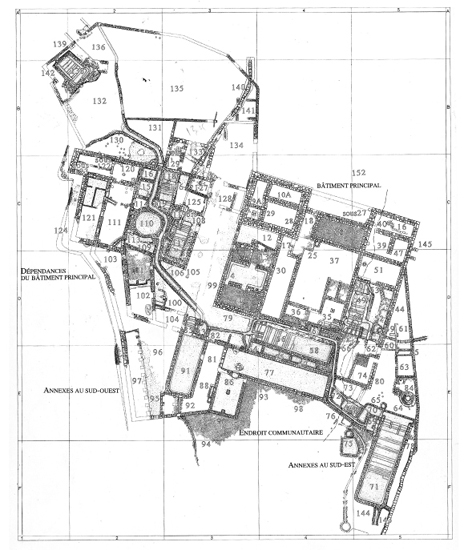

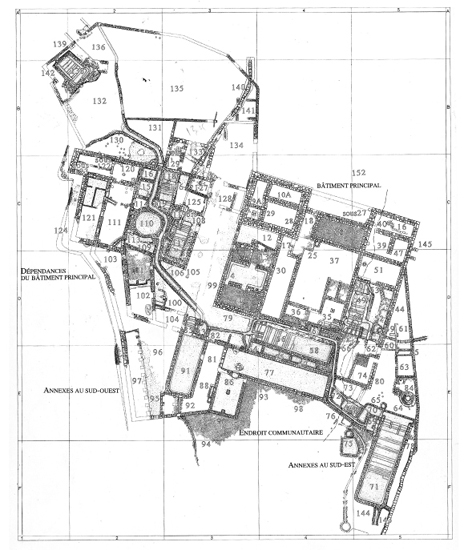

Plan of original fort at Qumran.

Reprinted from Jean-Baptiste Humbert and Alain Chambon, Fouilles de Khirbet Qumrân et de Ain Feshkha (NTOA.SA 1; Fribourg: Editions universitaires, 1994). Courtesy of the École Biblique.

Plan of Khirbet Qumran in period 1b.

Reprinted from Jean-Baptiste Humbert and Alain Chambon, Fouilles de Khirbet Qumrân et de Ain Feshkha (NTOA.SA 1; Fribourg: Editions universitaires, 1994). Courtesy of the École Biblique.

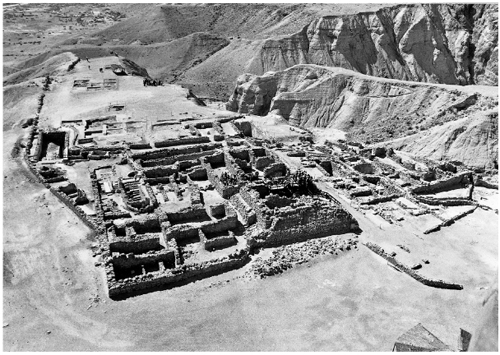

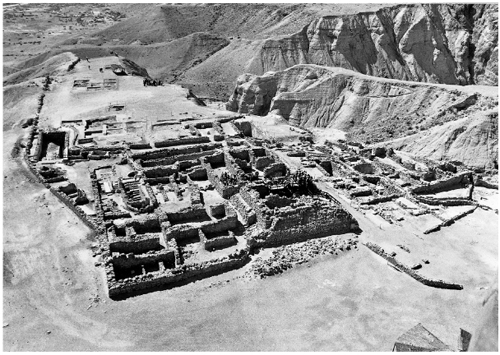

Aerial view of Qumran, looking south.

Reprinted from Y. Hirschfeld, Qumran in Context: Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence (Hendrickson, 2004).

Courtesy of the École Biblique.

Cave 1 exterior.

Courtesy of Todd Bolen/BiblePlaces.com.

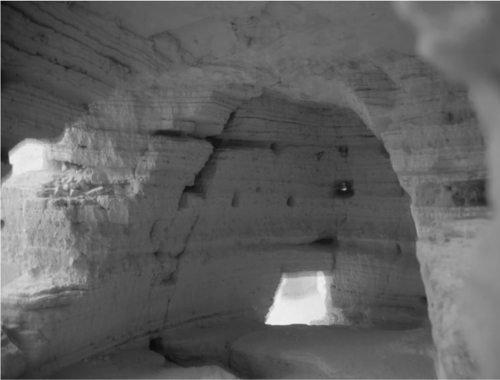

Cave 4 interior.

Courtesy of Todd Bolen/BiblePlaces.com.

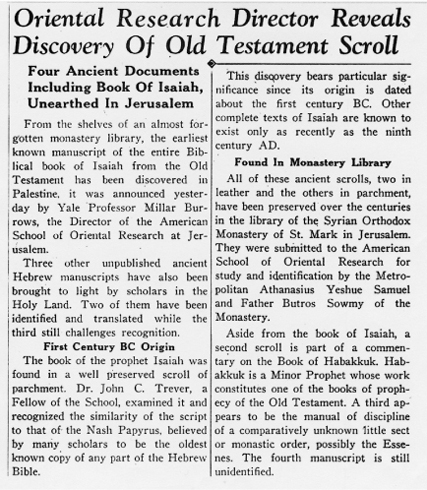

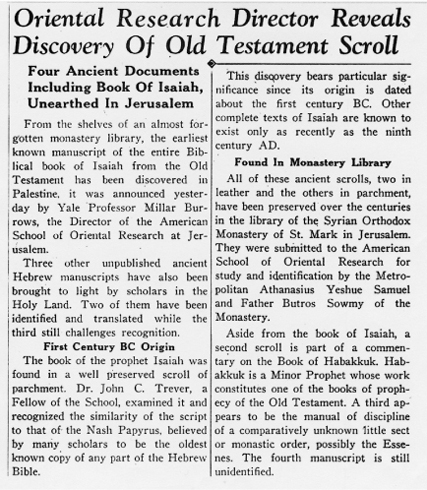

Announcement in the Yale Daily News, April 12, 1948.

(the word “live” does not normally have an aleph in the middle). Other scholars suggest that the word should be read as

(the word “live” does not normally have an aleph in the middle). Other scholars suggest that the word should be read as  , “the sign” (a word that occurs elsewhere in the text). So it is, to say the least, very uncertain that this text refers to resurrection, or indeed to a messiah Ephraim. Here again Knohl makes imaginative leaps to reach provocative conclusions, but very few scholars find his work persuasive.

, “the sign” (a word that occurs elsewhere in the text). So it is, to say the least, very uncertain that this text refers to resurrection, or indeed to a messiah Ephraim. Here again Knohl makes imaginative leaps to reach provocative conclusions, but very few scholars find his work persuasive.