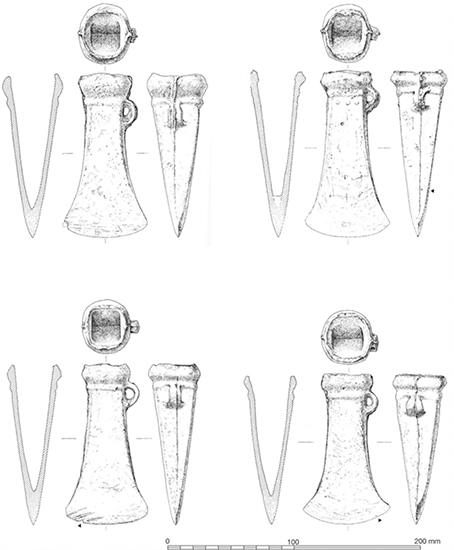

2.1 Bronze Age socketed axes from the late Bronze Age site at Tower Hill, Oxfordshire.

Art and Agency can be seen as an exploration of the manner in which the qualities of people are brought out by objects and how objects are given power and salience by people. The key questions asked in the latter part of the book concern both the problem of order and of intelligibility: how are artefacts ordered through evolving styles, how do such styles link to the broader ordering of culture, and in what ways do both the ordering of material things and of culture provide the grounds for the intelligibility of the world? Gell critically discusses Hanson’s (1983) work on Maori style, where Hanson makes a connection between the generally balanced symmetry of Maori carving and an ethic of balanced reciprocity found in social dealings more generally. All pattern will have some symmetrical features, Gell argues (1998: 160) because that is what pattern is – a play on symmetry. However, Gell does applaud the general direction of the argument – ‘I believe that the intuition that there is a linkage between the concept of style (as a configuration of stylistic attributes) and the concept of culture (as a configuration of intersubjective understandings) is well founded’ (ibid.: 156). Such a statement holds out an exciting prospect for any student of material culture, in the possibility that one can move from an analysis of the qualities of objects to the understandings people had of the world and of each other. Artefacts do not reflect intellectual schemes, but help to create and shape them. For the archaeologist, dealing with scant historical records or with none, the possibility of moving from form and decoration to broader understandings of society is seductive and increasingly popular (e.g. Malafouris and Renfrew 2010). In Art and Agency Gell was not explicitly concerned with history, but felt that his analysis could potentially be extended to embrace historical change. What he did provide was a set of analytical approaches to style and form which can be usefully extended to historical periods. In what follows, I would like to explore work which takes a historical perspective on material culture and especially that which tries to make a link between understandings of the world, social relations and material things. What Art and Agency can add to such work is a key question.

In his book Money and the Early Greek Mind, Richard Seaford (2004) charts the development of classical Greek society, with individuals and money, from a more communal, aristocratic and gift-giving society of the Bronze Age. Money, or rather its emergence, is key to Seaford’s argument. Money is a quantified measure of value operating on a scale which has no theoretical upper limit, it is generally acceptable within the area of its currency, helping to meet various forms of social obligation, but in an impersonal manner. Money depends also on systems of number and account; it requires extensive trust (ibid.: 16–20). Seaford sees money to be an important precondition for the emergence of a particularly individualized society, which created an ‘impersonal cosmology’ and forms of tragedy which focus ‘on the extreme isolation of the individual from the gods and from his own kin’ (ibid.: 316–17). This is a society in many ways similar to our own and quite different from previous Bronze Age forms in which the gods were directly interested in the world of people and people were much more imbricated in each other’s affairs.

At the heart of Seaford’s argument is a link between forms of material culture, such as coins, which were multiple copies of the same thing and forms of personhood, where individuals lived in an impersonal cosmos. Homer brings to life an aristocratic, feuding and heroic world of reciprocity and redistribution, in which obligations to kin and to the gods outweighed a notion of self or self interest. It is also a world in which objects were individualized, having their own known biographies. ‘The silver mixing-bowl, for instance, made by the Sidonians, given to Thoas, then to Patroclus as ransom to Lycaon, then by Achilles as a prize in the funeral-games, is said to be the most beautiful in the world’ (Seaford 2004: 46–47). Exchanges were also varied, lacking standardized exchange equivalents or anything analogous to price. There is an inverse relationship between an earlier individuality of objects and commonality of persons and a later serial reproduction of objects as against the rationalized individuality of people.

Although different in many respects, the works of Seaford and Gell share in common the idea that artefacts en masse are part of our joint intelligence, helping to make sense of the world and the people in it in particular ways. In fact Seaford’s broadest point is that by creating a universal notion of value and a link to substance in general, money opens up the possibility of generalized substance, of which individual things are detailed manifestations. Notions such as substance become key to philosophy from the pre-Socratics period onwards. The issue of substance is also important to current social sciences concerned with materials. Seaford’s work helps us to see and understand a key shift in Gell’s discussion in Art and Agency. In the early chapters of the book Gell’s concentration is on the relationship between individual people and individual objects, discussing the agency of both people and things. The relationship between the agent and the patient is laid out, along with the possibility that things can be agents as well as people. A key example, discussed relatively briefly in the book, is the Trobriand canoe prow board, which when carved and painted with skill becomes an object of enchantment, able to overwhelm the senses and the will of those looking at it. Such a work exists as an index of the artist’s skill, which in turn derives from broader cosmological forces. At the end of chapter 7 the book takes a sharp turn. To that point Gell has considered rather individual links between an artist, a work and its impact on a viewer. ‘However, art works are never just singular entities, they are members of categories of art works, and their significance is crucially affected by the relations that exist between them, as individuals, and other members of the same category of artworks, and the relationships that exist between this category and other categories of artwork within a stylistic whole – a culturally or historically specific art-production system’ (Gell 1998: 153). From here Gell moves into a consideration of style and what he calls ‘the inter-artefactual domain’.

For me, probably because I am an archaeologist and am interested in objects en masse, it is this last aspect of the book that has always been most interesting and persuasive. It is also partly that the Peircean language of index and patient has never really resonated with me. Taken together, Gell’s work and that of Seaford resonate with each other and the contrasts between them are also instructive. Seaford provides considerable historical and cultural depth in discussing early classical Greece, which is possible in a book-length treatment. He is less concerned to analyse the styles that money takes and does not get into any details of numismatics; and it is striking that the book lacks a single illustration. Gell’s book is composed as much of pictures as of words, carrying and illustrating much of the analysis. Necessarily in a general work of this kind there is little space to go into deep cultural analyses of the art objects discussed.

Looked at from the perspective of Seaford’s work, Gell’s analysis in the two parts of the book can help us to understand different moments in our relationships with art objects, from the individual encounter of one person and one object to broader relations between masses of objects and of people. In the first case, objects of wonder do strike and change us, making us feel differently about our relationships with the world and the people in it, and acting differently towards both. Relationships between masses of people and masses of objects do not need to be routinized and in many cultural forms are not. However, in Europe – from the middle of the last millennium in the eastern Mediterranean, to Britain five centuries later – more routinized forms of artefacts and human actions emerge in ways that create profound social change. Attending to the details of changes in artefacts can allow us real insights into the material nature of this process.

In the rest of this chapter I shall look at fine metalwork of the first millennium BC in Britain and the varied effects it might have had on people over time. In brief, I argue that metal artefacts passed from an emphasis on quantity, to quality and back to emphasize quantity again, with commensurate effects on people.

My main case study is drawn from late Iron Age and early Roman fine metalwork in Britain, known as Celtic art.1 Celtic art fits well within the notion of a technology of enchantment as outlined by Gell. It requires virtuosity and skill on the part of the maker. Considerable powers of appreciation and discrimination are demanded of the viewer, for whom the variety of decoration within and between artefacts means that no settled or fixed understanding is ever possible. Surprise, shock or ambiguity of reaction are all common today in encounters with Celtic art, especially when new pieces are discovered. We cannot know past reactions, but it is likely that such responses were hoped for, otherwise the sheer complexity and variability of decoration and form would have been redundant. Gell’s work highlights the power objects had to take people aback, partly due to their impact on the human senses, but also because items produced through a virtuoso display of skill were seen as an indication that the maker had a generally good standing with the generative powers of the universe. Before and after so-called Celtic art, were sets of objects that were more standardized and possibly routinized in Seaford’s terms. Here the later chapters of Gell are of use in helping us to understand links of form and decoration.

In dealing with prehistoric periods, such as the late Bronze Age (1100–800 BC) and Iron Age (800 BC–AD 43) in Britain, archaeologists are forced to concentrate on material remains, including the layout of landscapes, evidence of settlements, the remains of plants and animals eaten as food, indications of burials and information on artefacts, principally pottery, metalwork and stone tools, with occasional organic remains. In many of the humanities and social sciences, words – either written or spoken – are the primary forms of evidence. Things are often rather belatedly attached to such testimonies, leading to an obscuring of the role of material things. Prehistoric archaeologists lack written or spoken words by definition, and concentrate hard on materials as a result.

Such a bias in our evidence can be seen as a lack or a deficit, but it does have methodological advantages. Much archaeology over the last two centuries has concentrated on typology: the definition of types of artefacts and their ordering, usually to create a chronology. This mass of thick description of artefacts has often become an end in itself and hence an embarrassment to the more theoretically oriented. But now the emphasis on material things and the realization that things can help to shape people has given this huge descriptive enterprise new point and purpose. Gell echoed some aspects of the typological approach in his discussion of the inter-artefactual domain, when he said that artefacts with strong stylistic similarities, such as Maori meeting houses, set up a series of rules of form and decoration that human craftworkers needed to abide by when making a new addition to the corpus (Gell 1998: Chap. 9). In some sense, human muscles and skills are being used to reproduce artefacts, reversing what we would normally see as the arrows of cause between active human creators and the acted-upon passive materials of their creations. Not only do artefacts channel human productive action, they also attune the senses and the emotions, becoming part of the human ‘extended mind’. Things help to make the world intelligible in many ways, through actions of production, everyday patterns of use and of discard. When looking at relatively long time periods we can see that the plasticity of the human sensorium, brain and body, as opposed to the slower sweeps of change of artefacts, can mean that the body is very much attuned by things. Such ideas are implicit in Gell’s treatment of the inter-artefactual domain, where he looks at the long-term development of style on the basis on Maori meeting houses, drawing on Roger Neich’s work (Gell 1998: 251–58; Neich 1996). Timescale is crucial here in that human lives unfold on a biographical scale which is part of longer, slower flows of artefactual change, and the mutual effects of different timescales could be explored much more fully than they have been and than Gell was able to do, as the point about scale was made right at the end of the book. This key issue is one I shall return to once we have looked at some artefacts and their changes.

The late Bronze Age in Britain is characterized partly by large hoards of similar or identical artefacts, particularly socketed bronze axes. For instance, a relatively modest hoard from Tower Hill, Oxfordshire, contained twenty-two complete socketed axes, twenty-four fragments of axe, and other miscellaneous bronze items such as rings, bracelets, a pin and a partial rod, as well as metalworking evidence such as casting jets, scrap and slag (Coombs et al. 2003). The axes were of Sompting type, named after the Sompting hoard from Sussex. These axes have a body of rectangular section, broad above the blade and narrowing at the top, where there is a heavy collar. The blade is much wider than the socket, flaring out from the rectangular body. They have small loops near the mouth to attach binding. They generally have rib and pellet decoration of a relatively simple type (Figure 2.1). The Tower Hill axes were probably found in a ditch surrounding a house. The axes were as-cast, through the lost-wax method, having not been polished or finished. They varied to a minor degree in size, but were all almost identical in form. Their metal composition was low in tin, making them somewhat soft as working implements.

The Tower Hill hoard is typical of many found in the late Bronze Age, and many larger accumulations of axes are known. Hoards are characterized by large numbers of similar or identical axes, sometimes made of alloys too soft to provide a cutting edge, leading to speculation that these were standardized exchange items. They are found widely in southern Britain and northern France, indicating cross-channel links. The fact that so many axes were buried shows that they were also powerful when taken out of circulation, perhaps as offerings of some kind.

Standardized artefacts indicate standardized relations, both between people and between people and cosmological forces. Many of the axes of the late Bronze Age emerged from the same mould, making them identical. A key aspect of bronze and hence the Bronze Age was the need for trade. The main components of bronze – copper, tin and lead – are almost never found in the same areas and must be brought together. The extensive use of bronze necessitated exchange relations that reached across large areas of Europe, and through which many materials must have passed. The Bronze Age world was one in which far-flung contacts were regular, necessitating dealing with strangers. If artefacts were part of a technology to produce relations, then the standardization of artefacts could have been useful in reducing the uncertainty of a spatially extensive world. People’s status, and relations between regions, were influenced greatly by such exchanges. It is no surprise that attempts to standardize relations were made. These included not just gifts between people, but also to the gods, possibly seen as the sources of beneficial materials.

In the final episode of the Bronze Age, the so-called Ewart Park phase, deposition of axes in hoards reached very high levels. At the start of the Iron Age, around 800 BC, deposition drops dramatically. An older explanation for this was framed in terms of technological advance: the new superiority of iron rendered bronze obsolete and it was disposed of in large quantities. This explanation is now inadequate for a number of reasons. It does not explain why the deposition of bronze was regularly in the very specific form of axes, often new and unused rather than old and worn out. As bronze declined in use it is now clear that iron did not take over in any obvious way. It was not until 400 or 300 BC (the middle Iron Age) that iron supplies really took off, as can be seen from sites like Danebury hillfort which had a long settlement from the early to late Iron Age (Cunliffe 1995; Sharples 2010). New dates are now showing, somewhat confusingly, that iron was produced in the Bronze Age, from around 1000 BC (Collard et al. 2006).

Putting together the early production of iron and the fact that it only became popular after 400 BC, we can see iron as a reluctant technology slowly coming into wide use. There are a number of possible reasons for this reluctance, chief of which might be a key difference between bronze and iron. While the former metal can be melted and cast using the pyrotechnologies then available, iron could only be wrought. While bronze can be taken from a solid to a liquid and back to a solid, iron can only be worked hot in a solid state. It may be, conceptually at least, that iron was not enough like bronze to replace it. Materials shape concepts concerning form and transformation which can be hard to shift.

We can now see that between 800 and 400–300 BC there was a dearth of both bronze and iron. From the latter date onwards both make a come back, as metals were revalued. When bronze and iron reappear in quantity it is in quite different forms to those of the late Bronze Age. In the middle Iron Age a great range of metal forms appear, including saws, hammers, chisels and other wood-working tools and agricultural implements of various types. Most importantly for our present purposes is the set of artefacts known as Celtic art. Celtic art is a polymorphous set including armrings, torcs, horse gear, mirrors, swords and scabbards, shields, tankards, buckets and figurines (Garrow 2008). In the history of scholarship on the Iron Age it has been linked to the ethnogenesis of the so-called Celtic peoples, a link many would now find dubious and not an issue I want to address here.

My key point is that for the first few centuries of its production and use, roughly 400 to 60 BC, Celtic art shows a regard for quality not quantity, in considerable contrast to late Bronze Age metalwork. Items of Celtic art exhibit variety of form and decoration. Let us look briefly at a hoard, comparable to those of the late Bronze Age in being an accumulation of artefacts, but in all other ways different. The hoards of gold torcs from Snettisham, Norfolk, represent some of the most famous prehistoric artefacts from Britain – famous for their number, quality of workmanship and the fact that many are made of gold. They also manifest great variety.

Three hoards were found in 1948 with a further series excavated by Ian Stead of the British Museum in 1990. In total, seventy-five complete torcs and fragments of a hundred more have been found. Torcs are a relatively infrequent find in later Iron Age Europe, but exhibit variety disproportionate to their number. The bodies of torcs are made from wire, rods or tubular sheet with connections that vary from loop to ring to buffer, cage or spool, with the uncommon tubular torcs having complex fixing mechanisms hidden inside their buffer ends. Torcs are mainly made in gold, silver or electrum, but are occasionally found in bronze or iron. There are three areas of torc finds in Europe: a dispersed region from northern France through central Europe to Bulgaria; a concentrated density in the so-called ‘castros’ of northern Portugal and north-western Spain; and in the British Isles and Ireland (Hautenauve 2005). The latter two areas show internal typological similarities, while the broader continental region has a variety of torc types and periods. Not all artefacts labelled as such are strictly speaking torcs – only those with a twist demonstrate ‘torque’, having a springiness that tubular torcs and other neckrings do not possess, the latter having more in common with armrings made of sheet metal.

Torcs represent an important phase in the intermittent history of what we would call ‘precious metals’, that is, gold and silver. In Britain these disappear from the record by the eighth century BC to reappear probably in the third century in the form of personal ornaments, mainly torcs and armrings. This pattern of disappearing and reappearing mirrors that of bronze and iron, being part of the general revaluing of metals from around 400 BC onwards. The working of gold and silver, through the making of sheet metal and decorating it with engraved or repoussé decoration, shares techniques with bronze working, as in the drawing of wire or casting. Similarly, engraving, basketry hatching or casting on are all means of surface alteration which remove or add metal to a surface, which are found in gold work and shared with bronze. Hot soldering of joints is known from the seventh century BC onwards (Hautenauve 2005: 172) and this may have an Etruscan origin. Techniques found in most developed forms on torcs, such as granulation and filigree, may also have an ultimate source in Etruscan workshops, but one deployed in specific ways in places like Britain. From as early as the third century BC, torcs are joined by coins of gold (and later silver), with which they seem to have a close relationship.

The site of Snettisham is on a low hill, as many finds of torcs are, and is enclosed by a ditch, which might post-date the deposit of the torcs, although this is not certain. I shall pick two hoards, F and L, as they contain a range of material, including torc types, the forms of which, together with their treatment, will illustrate some key aspects of the Snettisham material. Hoard F was found by a metal detectorist, although the pit from which it came was excavated shortly afterwards by Stead (1991: 447, 450) with few additional finds. The hoard consisted of 587 separate items, some strung or fused together and many in a fragmentary state. As well as wire, ring and straight ingots, a range of torc types were found, most of which had wire bodies with variously cage, buffer, reel or ring terminals. Much of the wire work was complex, although the terminals were less so, with the exception of one ring terminal (BM P19915-1.45), a number of buffer terminals and a reel terminal with upstanding cast-on or engraved decoration.

As a nested set of relationships, Hoard F is extremely complex. The creation of different forms of wire by drawing and ingots or terminals by casting, as well as the creation of sheet which was then worked by repoussé decoration, along with the punching, tooling and polishing found on other decorations, made for varied artefacts (Figure 2.2). A number of fragments of tubular torc were found, one of which had been folded over as a container for five coins, and one of which had been halved (Stead 1991: Plate 1). Parts of the tubular torc fragments were repaired in antiquity, so were worn and probably old when deposited (Stead 1991: 454–55). One piece, which was highly decorated, was pierced for threading (Stead 1991: Plate III). A considerable array of objects, including torc terminals and fragments of torc bodies, were threaded onto pieces of wire or bracelet ingots. Some pieces were fused together, but these were unlikely to be part of recycling as they involved objects with varying metallic composition. Hoard F is similar in composition to Hoards B and C at Snettisham, but also shows characteristics (the combination of torcs and coins, as well as the deliberate destruction of objects) with other hoards across Europe, such as those at Beringen, Niederzier, Kegelriss and Netherurd (Fitzpatrick 2005: 168–69).

All these hoards were deposited on land and are complemented by finds from La Tène and Pommeroeul deposited in water (Fitzpatrick 2005: 169). Care was exercised in the making, breaking and curating of objects, some of which might have been old when they entered the ground. Artefacts were transformed from wholes to parts and then combined in new ways. Gell’s work was very much concerned with issues of partibility and synecdoche (Gell 1998: 165–68), and the links between the partibility of artefacts and of people would bear more discussion and analysis.

One possible transformation, for which we have no direct evidence, is from coins to torcs (or torcs to coins). In any case, the partible nature of torcs mean that they could have operated in small units like coins, and in some cases, like the highly decorated tubular torc fragment, they carried complex decorations. To compare torcs and coins positively might be to impute monetary status to the former, but our reading would be that neither were money, in the sense we understand today. Coins and torc fragments helped to create and change social relations, but by virtue of being themselves rather than as tokens of wealth, which would mean they stood for something else. Coins became money after torcs went out of use, a point I shall return to below.

The sheer variety of form and decoration on Snettisham torcs is a clear instance of a broadly occurring aspect of Celtic art. Of the 274 swords known from Iron Age Britain in Stead’s corpus, no two are identical in the characteristics of sword or scabbard or in their mode of decoration, where this is present (Stead 2006). Even within the decoration of a single item, such as the sword from Sutton Reach, Nottinghamshire (Figure 2.3), the details of decoration vary in subtle but definite ways along the length of the scabbard. Such a deliberate choice for variability adds extra challenges both for the maker and the viewer, who need to attend to the details as well as trying to take in the whole. As the Snettisham hoards show, torcs and other objects had complex histories prior to deposition, being broken and recombined in multiple ways. Breaking as well as making was important in Celtic art.

As we have seen, torcs have been found together with a number of other objects at Snettisham, including coins. Coins in Europe have a complex history. The earliest British coins derive from Macedonian prototypes first issued by Philip II (359–336 BC), with the head of Apollo on the obverse and a two-horse chariot on the reverse. Gold coins copying the original Macedonian designs appear sporadically in southern Britain from around 300 BC. Around a century later, Gallo-Belgic coins are being produced in northern France, quite a number of which end up in eastern and southern Britain. Gallo-Belgic coins have been divided into series (A–F), each with their own details of iconography and their own pattern of changes. Gallo-Belgic A coins, for instance, are large coins in which the original Macedonian head of Apollo has been remodelled to emphasize the hair and the wreath. On the reverse, the chariot and horses have become a single horse, which is itself in the process of fragmenting so that body, head and legs come apart into more abstract patterns of lobes and dots (Figure 2.4).

Celtic coins are known for their serial imagery (Creighton 2000) in which a sequence of defined steps can be recognized for each series moving towards greater abstraction. In an older literature this was seen as devolution, as the natives were less able to maintain the realistic artistic standards of the Mediterranean world. A glance at the contemporary metallurgy of Celtic art gives the lie to this – metalworkers were in full control of form and decoration, even in the more miniature world of coins. The movement to abstraction in the serial imagery of coins was a deliberate choice. Gallo-Belgic C series coins gave rise to most of the regional series in southern and eastern Britain from 125 BC when coins were produced in some numbers in Britain for the first time (ibid.: Figure 2.3). Coins diversified from this point, with silver becoming common and complementing gold, as well as the cast bronze coins (potins) with rather different iconography. Celtic art provided the iconographic context for the acceptance of coinage, leading one to wonder whether the designs on Celtic art were also arrived at through a process of abstraction.

From around 60 BC coins changed again. The first inscribed coins appear with the names of kings or local rulers in Latin (the first evidence of writing in Britain) and much more Romanized designs. These coinages continued to evolve until the later first century AD, and some of them have names known historically, such as Verica or Cunobelin. At about the same time as the newly Romanized coins appear, Celtic art disappears (Garrow et al. 2010: 110–12). Other changes occur, more or less contemporaneously. Safety pins for holding clothing together, known as fibulae, are found sporadically from the early Iron Age onwards, slowly proliferating into a considerable range of forms with some, such as the involuted brooch series, only known from Britain. In the middle of the last century BC, numbers of brooches rise considerably and their types standardize (Hill 2007). We have little evidence of clothing, but a change in fibulae might also indicate a more standardized form of dress and personal appearance more generally. Also, at around 60 BC, temples and sanctuaries emerged in Britain (echoing earlier versions in northern France) and here large numbers of items, often coins and fibulae, are found deposited in association with circular or rectangular structures. A number of these Iron Age sites were rebuilt in new Romanized forms after the invasion of AD 43.

The co-occurrence of torcs and coins at Snettisham represents the meeting of two different worlds of iconography and design. Unlike Bronze Age metalwork or late Iron Age coins, torcs do not behave typologically in the sense that we cannot form them into series with an obvious direction of change to them. This lack of typological or directional change is characteristic of Celtic art as a whole. It is characterized on the one hand by variety, but on the other it lacks any clear sequence. This is true not just of the form of objects, but of their decorations. Much effort over the years has been spent in devising schemes of decoration which can be sequenced and dated. Much of this work goes back to Jacobsthal (1944) who ordered the continental material, and this was reworked by Stead (1996) into a series of six stages. A recent radiocarbon dating programme, the first on Celtic art, has confirmed earlier suspicions (Macdonald 2007), that Stead’s stages were not successive, but rather that motifs accumulate (Garrow et al. 2010: 110–12). Some motifs are earlier than others, but these are not replaced but supplemented by newer forms of trisceles, trumpet voids and berried rosettes. Celtic art did not subscribe to modernist notions of originality and difference from past forms, but rather appropriated earlier forms, incorporating them, when they worked, into newer designs. This contrasts with the directional movement of coins from complexity to abstraction.

I have presented a complex empirical sequence of changes in metalwork over the last millennium BC, about which much more could be said (see Garrow and Gosden (2012) for an extended version of this argument). Let us draw out the main trends as this will allow us to reflect on people and things, art, aesthetics and personhood. Broadly speaking we can see a shift from an emphasis on quantity in the late Bronze Age, through a period when metalwork was not culturally valued in the early Iron Age, to an emphasis on quality between c.400 and 60 bc, with a return to quantity and standardization in the late Iron Age and early Roman period.

In term’s of Seaford’s argument, with which I started this chapter, there may well have been a move to monetization and greater individuality in southern Britain from around 60 BC. As we have seen, coins existed in Britain from c.300 BC, but for much of this time they were probably not money; that is they did not operate as a standardized means of exchange in a market economy in which a key aim was to make a profit. Early coins were of too high value to play a role in everyday exchanges; most are not found on settlements or in places where everyday life was played out, but occur in hoards or singly in the landscape. High value coins probably facilitated socially charged exchanges, as well as interchanges with spiritual powers. As such, coins were part of an ethic of reciprocity between people and the powers of the cosmos that led to the regular deposit of artefacts on land, and in rivers and bogs. Early coins fitted within a broader set of practices in which Celtic art also played a key role. However, the serial, sequential nature of change in coin designs suggests that they were different from the start, although the full possibilities of this difference were only explored some centuries after their introduction, in the fast-changing world of the late Iron Age. By this time, key individuals were being iconized, most evident through the names on the inscribed coinages. It is significant that the first use of writing in Britain was to propagate and distribute the names of individuals over considerable areas; text was an important aspect of power. Paradoxically, individuality may also have been evident in newly standardized forms of dress and personal ornament. We can see a similar phenomenon today: in a society with a strongly individual ideology and great potential choice in dress styles, many of us look the same.

The middle Iron Age world in which Celtic art originated was different. Hill (2007) has emphasized the instability of life in the centuries after 400 BC. Some areas of southern Britain were uninhabited at this time, whereas they had been occupied previously, or else were used in such a way (through pastoral economies?) as to leave little archaeological trace. Field systems that were set up in the late Bronze Age may not have been used in the early and middle Iron Ages, indicating a more fluid, less bounded relationship to land. Settlements take a variety of forms. Some site categories, such as hillforts, varied internally, so that Danebury, in Hampshire, was densely occupied over a number of centuries (Cunliffe 1995), but others, such as Segsbury (Lock et al. 2005) had little internal evidence of use and might have been periodic meeting places. Pottery became more decorated in the middle Iron Age and shows more regional differentiation.

In all, the middle Iron Age appears a regionally diverse and unstable world, with mobile populations, less obvious attachment to land in some areas than earlier or later, and varied material culture. Celtic art fits into this world as a means of negotiating power and identity relations in a manner which was open but compelling. The variety of form in Celtic art is complemented by an ambiguity and mobility of decoration. It is possible to glimpse in the tendrils, voids and whirligigs of Celtic art images of people, plants, animals and birds. But rarely is a certain identification possible, making singular or fixed readings of these artefacts hard to sustain. We can imagine story, song and performance around shields, torcs, mirrors or swords, but these would not have been fixed or closed narratives, open instead to debate and exegesis. Such openness was extended through actions of breaking and recombining artefacts prior to burial.

In the late Iron Age the landscape fills up, with areas uninhabited in the previous period often becoming centres of power, with large-scale land divisions, settlements or sanctuaries providing foci for human action. There is more fixity in the relationship to landscape, as late Bronze Age field systems are reused and extended. Considerable numbers of Roman (or Gallo-Roman) imports in settlements and graves indicate new sets of long-distance relationships and modes of personhood at home. The object world sees an excitation, deriving ultimately from the Mediterranean, in terms of forms of pottery, glass and metalwork. Although forms proliferate, they also standardize, so that pottery is more often made on the wheel, for instance. Directional, typological change is general as the coinage demonstrates.

Artefacts and people were changeable and negotiable in the middle Iron Age, and technologies of enchantment played out through metalwork were key to the performative and negotiated nature of social life. By the late Iron Age, material culture had proliferated into a technology of routine, producing more standardized forms of people and relationships with the sacred. In some ways these historical changes parallel those sketched by Seaford (2004) when looking at the loss of magic in the movement from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age world of the polis.

Within the historical changes briefly sketched here, Gell’s work allows us to understand both individualized objects and artefacts more obviously united in a strong canon of style. The late Bronze Age and later Iron Age did not produce enchanting objects sufficiently frequently for these to be central to life in those periods. The middle Iron Age did. The emphasis on art, stronger at the beginning of the book than in the final chapters, focused Gell’s attention on especially powerful artefacts rather than providing a broader account of material culture and its cultural impacts. Concepts of form and style can be applied to all objects, whether they be arresting or not. They are helpful in understanding changes in broader stylistic schemes, which then link to and underpin more general changes in how people acted in and understood the world. The links between the formal qualities of objects and the intelligibility of the world are key to archaeological considerations of material culture, certainly as they have developed over the last few decades.

Our project on Celtic art had the title of ‘A Technology of Enchantment’ so that the influence of Gell has been clear and beneficial (Garrow and Gosden 2012). As the project has gone on, the historical specificity of Celtic art has become clearer and the need for modified sets of theory more apparent. The approach taken by Gell has highlighted that there is a lot at stake in an analysis of material culture: how people present themselves as persons; the manner in which the world is made intelligible and the broader relationships with earthly and cosmic powers all come to the fore. Many of these issues would have been tackled without Art and Agency, but Gell’s approach has brought new forms of analysis to material things in a great range of contexts. Human history derives from varying involvements of people with materials. We live in a world with routinized elements of life and materials, such as money, which are only effective if they are always the same. Creative and varied engagements are also privileged elements of our material-social relations. Gell’s approach looked rather more at creativity than routine, but is a key element in developing theories of changing historical engagements between people and their material worlds.

I am very grateful to a number of people: firstly, to Liana Chua and Mark Elliott for inviting me to take part in the original symposium and to make a contribution to this publication; secondly, to the Celtic art project (Technologies of Enchantment) which was funded by the AHRC (grant number 112199); thirdly, for the collaborative work with Duncan Garrow and J.D. Hill, as much of the content here has been developed through conversations with them; and finally, for the comments of three anonymous reviewers, which have helped to nuance and change some of the arguments made.

1. The work described here derives from an AHRC-funded project on Celtic art in Britain, carried out in collaboration with Duncan Garrow and J.D. Hill.

Beswick, P., R. Megaw, J.V.S. Megaw and P. Northover. 1990. ‘A Decorated Late Iron Age Torc from Dinnington, South Yorkshire’, Antiquaries Journal 70: 16–33.

Collard, M., T. Darvill and M. Watts. 2006. ‘Ironworking in the Bronze Age: Evidence from a 10th Century BC Settlement at Hartshill Copse, Upper Bucklebury, West Berkshire’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 72: 367–421.

Coombs, D., P. Northover and J. Maskall. 2003. ‘The Tower Hill Axe Hoard’, in D. Miles, S. Palmer, G. Lock, C. Gosden and A.M. Cromarty, Uffington White Horse Hill and its Landscape. Investigations at White Horse Hill Uffington, 1989–95 and Tower Hill Ashbury, 1993–4. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology Thames Valley Landscape Monograph 18, pp. 203–23.

Creighton, J. 2000. Coins and Power in Late Iron Age Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cunliffe, B.W. 1995. Danebury. An Iron Age Hillfort in Hampshire. Vol. 6. A Hillfort Community in Perspective. York: Council for British Archaeology (Research Report 102).

Fitzpatrick, A. 2005. ‘Gifts for the Golden Gods: Iron Age Hoards of Torcs and Coins’, in C. Haselgrove and D. Wigg-Wolf (eds), Ritual and Iron Age Coinage. Mainz: Studien zu Fundmunzen der Antike 20, pp. 157–82.

Garrow, D. 2008. ‘The Time and Space of Celtic Art: Interrogating the “Technologies of Enchantment” Database’, in D. Garrow, C. Gosden and J.D. Hill (eds), Rethinking Celtic Art. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 15–39.

Garrow, D. and C. Gosden. 2012. Technologies of Enchantment? Celtic Art in Britain c.400 BC to AD 100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garrow, D., C. Gosden, J.D. Hill and C. Bronk Ramsey. 2010. ‘Dating Celtic Art: A Major Radiocarbon Dating Programme of Iron Age and Early Roman Metalwork in Britain’, Archaeological Journal 166: 79–123.

Gell, A. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hanson, F.A. 1983. ‘When the Map is the Territory: Art in Maori Culture’, in D.K. Washburn (ed.), Structure and Cognition in Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–89.

Hautenauve, H. 2005. Les torques d’or du second Age du fer en Europe. Techniques, typologies et symbolique. Rennes: Travaux du Laboratoire d’Anthropologie, 44.

Hill, J.D. 2007. ‘The Dynamics of Social Change in Later Iron Age Eastern and South-Eastern England c.300 BC – AD 43’, in C. Haselgrove and T. Moore (eds), The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 16–40.

Jacobsthal, P. 1944. Early Celtic Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lock, G., C. Gosden and P. Daly. 2005. Segsbury Camp: Excavations in 1996 and 1997 at an Iron Age Hillfort on the Oxfordshire Ridgeway. Oxford: University of Oxford School of Archaeology Monograph 61.

Macdonald, P. 2007. ‘Perspectives on Insular La Tene Art’, in C. Haselgrove and T. Moore (eds), The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 329–38.

Malafouris, L. and C. Renfrew (eds). 2010. The Cognitive Life of Things: Recasting the Boundaries of the Mind. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Neich, R. 1996. Painted Histories. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Seaford, R. 2004. Money and the Early Greek Mind: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sharples, N. 2010. Social Relations in Later Prehistory. Wessex in the First Millennium BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stead, I. 1991. ‘The Snettisham Treasure: Excavations in 1990’, Antiquity 65: 447–65.

———. 1996. Celtic Art in Britain before the Roman Conquest, 2nd edn. London: British Museum Press.

———. 2006. British Iron Age Swords and Scabbards. London: British Museum Press.