CHAPTER 5

GELL’S DUCHAMP/DUCHAMP’S GELL

Simon Dell

That Marcel Duchamp should have been of interest to Alfred Gell is unsurprising. Artist and anthropologist shared a measure of contempt for the European tradition of aesthetics, and both opposed this tradition through sometimes abstract and indeed sometimes abstruse theorizing. Gell’s engagement is evident in his account of Duchamp’s work in the conclusion of Art and Agency and is nicely indicated by the choice of Network of Stoppages as the illustration for the book’s cover. Yet this work by Duchamp was also the subject of another essay by Gell, published in the present volume for the first time; this text is the occasion for my own.

Gell presents his essay on Duchamp as an attempt to address two related issues: the representation of time and continuity in the artist’s work and the larger and no less thorny question of how anthropologists might account for change and historical transformation. As Gell notes at the outset: ‘We still continually hear this or that anthropological theory lambasted on the grounds that it “cannot handle change”. But where does one look for a coherent account of what might be meant by “change”?’1 Gell was certainly prepared to look in all sorts of places and retracing his itinerary will therefore sometimes be tortuous. Yet this path does lead to what I regard as his larger anthropological project, one developed in The Anthropology of Time (Gell 1992) as well as in Art and Agency (Gell 1998). From the perspective of an art historian, examining this project through the essay on Duchamp has two advantages, and these are as intertwined as the issues Gell confronts.

First, Gell’s account of an artist working within and against the twentieth-century avant-garde is an example of his theorizing applied to material which falls squarely within the domain of art history, as it is conventionally defined. Second, the approach to Duchamp casts light on Gell’s model of temporality, and it will be my contention that this reveals much about both the benefits and the limitations of his anthropological theory of art. For Gell, Duchamp’s oeuvre is important as ‘an exceptionally coherent and codified instance of the phenomenon of temporal transformation’ and because ‘it points us in a specific direction in the search for solutions’ to the problem of temporal order and its transformations. The shape of Duchamp’s oeuvre permitted Gell to construct a novel and striking argument; yet the very manner in which the oeuvre was shaped also represents a challenge to Gell’s account. This is because Duchamp’s oeuvre was decisively marked by institutional forces which Gell was reluctant to acknowledge. However, before addressing the limits of Gell’s theory I need to show how the anthropologist applied it to Duchamp’s work.2

Gell’s Duchamp

Gell’s essay on Duchamp is related to the account of the artist offered in Art and Agency while amplifying it in significant ways, a fact which itself demands brief explication. In his book, Gell uses Duchamp’s oeuvre to illustrate his thesis concerning the extended mind; according to Gell, Duchamp’s consciousness as a distributed object is concretely instantiated in his artworks. The example of Duchamp thus serves as one conclusion to the book’s larger argument concerning the agency of artworks. Yet in Art and Agency Duchamp’s work also serves a more immediate purpose, as an example of the oeuvre as temporal object. It is this aspect of Gell’s account which is given more extended treatment in the essay and which requires attention here.

In developing his model of temporality, Gell draws directly on the work of Edmund Husserl, and he cheerfully acknowledges that he is cheating in selecting Duchamp’s oeuvre to illustrate his model. This is because ‘Duchamp was probably to some extent aware, even if only indirectly . . . of the James-Bergson-Husserl conception of temporal flux or the “stream of consciousness” ’ (Gell 1998: 243, ellipsis added). So as Gell concedes in his book, ‘there might be an element of tautology involved in using Duchamp to illustrate a “Husserlian” model of art history, when, in fact, Duchamp may actually have set out to illustrate it’ (Gell 1998: 243, emphasis retained). This tautology is approached in a different way in the essay on Duchamp, where it is presented as a matter of historical juncture. For Gell, ‘the formative period of 20th century art (i.e. 1890–1925) coincides exactly with the formative period of our own subject’, that is, anthropology. This juncture enables what is to be Gell’s principal labour in the essay, a ‘lateral’ excavation of the foundations of anthropology which he hopes will reveal new ways of addressing the pressing problems of the discipline, including the anthropological theorization of ‘change’. In this context, Gell’s tautology becomes a heuristic device; he hopes to show that Duchamp’s struggle to represent duration and continuity involved ‘certain conceptual strategies which are just as applicable in anthropological contexts as they are in pictorial ones’. Thus Duchamp’s work moves from being a mere example to becoming something closer to generative of a theory.

In the essay on Duchamp, the discussion of duration begins with Henri Bergson. In Bergson’s philosophy an opposition was established between the order of conceptual thought oriented towards action, and the continuous, ‘self-transforming order of durée’ which ‘tends towards understanding and transcendence, rather than action’. The crucial question is the extent to which these ideas were formative for the first generation of Cubist painters.3 Here Gell navigates between the competing claims of art historians. In doing so, he suggests that Duchamp’s early works, such as the Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 of 1912, were satirical in intent; if artists such as Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger had taken it upon themselves to picture the Bergsonian problem of continuity, Duchamp was present ‘to demonstrate the nullity’ of the project.4

These manoeuvres bring Gell to the centre of his argument, and to the collage of quotations which also features, albeit in a different form, in the account of Duchamp in Art and Agency. Having prescribed Bergson’s role, Gell proceeds to the philosophy of William James and his description of the stream of consciousness as ‘an alternation of flights and perchings’. Whilst the resting places or perches are occupied by sensorial imaginings, the places of flight are more dynamic. Thus James suggests: ‘Let us call the resting places the “substantive parts” and the places of flight the “transitive parts” of thought’. After this, Gell alights on the Dakota wise man as cited by Durkheim: ‘The bird as it flies stops in one place to make its nest, and in another to rest in its flight . . . So the God has stopped . . . The trees, the animals, are all where he has stopped’. And from here it is but a hop to Claude Lévi-Strauss, who uses the Dakota wise man in his discussion of Bergson and cites the latter to this effect: ‘A great current of creative energy gushes forth through matter, to obtain from it what it can. At most points it is stopped; these stops are transmuted, in our eyes, into the appearance of so many living species’.

If this flight seems to have carried the reader some distance from the work of Duchamp, this is not in fact the case. Gell now turns to Duchamp’s Network of Stoppages of 1914 and observes how the work is composed of three elements; a ‘background’ which is a version of the 1911 painting Young Man and Girl in Spring, a squared-up sketch for the later Large Glass, and, most prominently, a network of lines and ‘stops’ radiating from the lower-right corner of the work (Figure 4.2). With a characteristic combination of elegance and audacity, Gell states: ‘The superimposed paintings correspond to what James called, in the passage I have cited, the “substantive parts of thought”, while the conceptual spaces which separate the paintings, the dimension in which they are separated, corresponds to the “transitory parts of thought” ’. The network of stoppages referred to in the work’s title is not simply the collection of radiating lines, it is also the ‘layer-cake’ of elements comprising the painting (Gell 1998: 249).

So, for Gell, Duchamp’s Network of Stoppages can be read as a ‘painterly autobiography’. Yet he swiftly qualifies this reading by noting that whilst autobiography is retrospective, Duchamp’s painting may be read in the other direction, ‘representing the future seen from its past’, adumbrating as it does the Large Glass. It is at this point that Gell shifts the focus of his argument, to introduce Husserl’s model of time-consciousness as the means of grasping the temporal relations he sees in Duchamp’s work.

In briefest summary, Husserl’s model is of an extended present, one understood not as a knife-edge between past and future but embracing both ‘retentions’ of recent experiences and ‘protentions’ of the proximate future (see Figure 4.3). The utility of this model for approaching Network of Stoppages should be immediately apparent; it permits Gell to characterize the work as showing ‘a protentional-retentional field of a few years, between, say, 1910 and 1918, focussed on the “now” moment of the actual making of the image, in 1914’. Yet not content with this, Gell wishes to draw a further conclusion: ‘that the method of superimposition, clearly indicated in this painting of Duchamp’s, is in fact the method which is characteristic of his artistic production as a whole’. To demonstrate this he constructs a model of Duchamp’s entire oeuvre drawn from Arturo Schwarz’s catalogue raisonné (Figure 4.4). The diagram serves to reveal the oeuvre as a network of stops. Therefore, in the final analysis, ‘the significance of any Duchamp work is never anything but relative, because it is never in the individual works, the “stops”, that meaning resides, but only in the gaps which lie between them’.

By this point the reader familiar with Art and Agency will have noted the congruence between Gell’s account of Duchamp and the anthropologist’s general account of the art nexus; in both cases ‘work’ is construed as ‘network’. In the present context this prompts questions. Is Duchamp’s oeuvre merely an instantiation of Gell’s theory? Or has the oeuvre exerted its own agency over Gell? To answer these questions it is necessary to turn both to Gell’s broader project and to aspects of Duchamp’s career which Gell neglects.

Duchamp’s Gell

In the introduction to Art and Agency, Gell offers a provisional definition of the anthropology of art as the study of ‘social relations in the vicinity of objects mediating social agency’ (Gell 1998: 7). Art is thus construed as a system of action; and one of the fundamental conditions for action is time. Other conditions also obtain, of course, but for Gell, time is the most salient, for several reasons. Gell wishes to analyse not simply action but social agency. This he holds to be the central task of the anthropologist, who works ‘by locating, or contextualising behaviour not so much in “culture” (which is an abstraction) as in the dynamics of social interaction, which may indeed be conditioned by “culture” but which is better seen as a real process, or dialectic, unfolding in time’ (ibid.: 10). Such a view of anthropology lends the discipline what Gell describes as ‘a particular depth of focus’ (ibid., emphasis retained). Anthropology ‘tends to focus on the “act” in the context of the “life” – or more precisely the stage of life – of the agent’ (ibid.). This focus has profound consequences, both positive and negative, for an anthropological theory of art and also for the relationship of that theory to art history.

The consequences become apparent as the argument of Art and Agency unfolds. Gell’s definition of anthropology and his fidelity to the biographical oblige him to develop an account of the abduction of agency. It is in this context that the subtitling of the book as ‘an anthropological theory’ takes on its full significance; Gell’s definition of anthropology in fact generates his theory of art. He proposes ‘that “art-like situations” can be discriminated as those in which the material “index” (the visible, physical “thing”) permits a particular cognitive operation’, an operation Gell identifies as the abduction of agency, that is, one in which the ‘index is itself seen as the outcome, and/or the instrument of, social agency’ (Gell 1998: 13, 15, emphasis retained). This theory of abduction is richly and provocatively developed over the course of Gell’s book; here I cannot attempt to do justice to all his arguments, and will confine myself to their potential contribution to art history.

What Gell offers to the art historian is a properly dynamic account of artworks. As a generalization, though not, I think, a gross one, it could be stated that most art historians subscribe to one of two views, accenting either the production or the consumption of works of art. Certainly many have attempted to embrace both these processes, most frequently through the simple expedient of working consecutively from one to the other. To take one of the more celebrated formulations of the problem: the work of art is ‘the deposit of a social relationship’ (Baxandall 1974: 1). Thus in the case of, say, painting: ‘On the one side there was a painter who made the picture, or at least supervised its making. On the other there was somebody else who asked him to make it, provided funds for him to make it and, after he had made it, reckoned on using it in some way or other’ (ibid.). In the present context the difficulty with this formulation is obvious. The account of the process is restricted to flesh-and-blood actors; the artwork itself does not have agency.

A similar difficulty is confronted in numerous other art-historical accounts (even when they might otherwise seem quite distinct from the above). Arguably even the most engaged art historians, who view the sign as a site of contest, still see the artwork as the occasion for struggle rather than as a protagonist. By way of contrast, Gell offers a theoretical model in which the artwork can participate; he thereby offers new ways of considering the relationship between the artwork and its ‘context’, ways in which the artwork is not a passive ‘deposit’ but is made active. The various diagrams in Art and Agency suggest as much; and in this they are relatively straightforward (that some have found them captivating is principally a demonstration of Gell’s own skill with technologies of enchantment).

I should emphasize that a signal virtue of Gell’s dynamic account is that it is not simply a contribution to the study of the artefactual but could also be an important contribution to a critical art history, if that project is understood to address art as ‘both context-bound and yet irreducible to its contextual conditions’ (Podro 1982: xviii–xx). Undertaking such a project requires navigation between formalism and a merely documentary approach; thus a critical art history must address matters of fact concerning the circumstances of an artwork whilst not reducing the work to those circumstances. This critical project has several points of contact with Gell’s, which firmly rejects formalism yet nevertheless seeks to discriminate between ‘art-like situations’ and a broader artefactual record. Gell’s response to the problem of the specific status of artworks (or ‘art-like situations’) was of course shaped by his conception of time, and whilst he is concerned with continuity and duration he does not attempt to dissolve the artwork in a temporal flow, nor even fully submerge it. The work is a ‘stop’. Thus the obdurate materiality of the artwork is acknowledged yet also recognized as more than material, precisely because the artwork continues to act. In this way Gell’s theory of agency gives some purchase on the problem of duration and what it means for an artwork to continue to compel our attention even when separated from its original context. Thus from the perspective of a critical art history one could describe the contribution of Art and Agency as the attempt to overcome materiality as durability, or, better, to reveal more clearly what durability is.

Yet this contribution remains potential; Gell’s work has not been warmly received by art historians. It seems to me that the reasons for the muted welcome also derive from Gell’s conception of time, and what it excludes. The difficulties here lie with the anthropological ‘depth of focus’. Gell’s concern is with ‘the immediate context of social interactions’ rather than longer time scales; thus his focus is on ‘particular artworks in specific interactive settings’ (Gell 1998: 8, emphasis added). Whilst these interactive settings are the province of anthropology, Gell holds that the ‘particular institutional characteristics of mass societies’ lie beyond these settings and are thus the domain of the sociology of art (ibid.). He concedes that anthropologists cannot ignore institutions, yet also asserts ‘that there are many societies in which the “institutions” which provide the context for the production and circulation of art are not specialized “art” institutions as such, but institutions of a more general scope; for example, cults, exchange systems, etc.’ (ibid.) And for Gell it is the existence of such societies which justifies the ‘relative autonomy of an anthropology of art’ (ibid.: 9).

This simply prompts a question as to the value of such relative autonomy. If the autonomy requires excluding from consideration those societies in which ‘art’ institutions do exist then it might seem that the price is too high. At least, it might seem reasonable to desire of an anthropological theory that it make some address to these societies rather than simply designating them the province of sociology. In the present context this is an important issue because ‘art’ institutions, as I have intimated, shaped Duchamp’s oeuvre in profound ways; perhaps, above all, this was the case for the institution of the art market. Here a seeming paradox needs to be addressed: that the ‘individuality’ of a modern artist such as Duchamp is a product of the operation of the market, which renders labour abstract and anonymous. This is a complex matter and its treatment requires several stages of analysis.

Markets in the first instance may have existed as a means of disposing of surplus, yet they tend to encourage the production of goods for exchange. Marx argues that goods for exchange, that is, commodities, create specific conditions for their producers, who only enter into relation with one another in the act of exchange. As a result ‘the social relations between persons’ appear to them ‘as material relations between persons and social relations between things’ (Marx 1990: 166). In such situations ‘products of labour acquire a socially uniform objectivity as values’ (ibid.). And distinguishing between value and use in a product of labour involves a process of abstraction, as the socially uniform objectivity of value, that is, equality in the full sense between different kinds of labour, can only be arrived at by treating ‘human labour in the abstract’ (ibid.). This abstraction is the difficulty that the market creates for Gell’s theory; the market mediates between producers and consumers in such ways as to inhibit the ‘particular cognitive operation’ which is abductive inference. For Gell, this inference is to result in ‘access to “another mind” ’ (Gell 1998: 15). Yet such access is, by definition, prevented in the production of commodities where it is not the agency of producers which is at issue but the creation of value. For Marx, commodities mediate social relations but they do not mediate social agency. Thus they do not offer mediation in the way Gell describes it in ‘art-like situations’.5

Of course, one could respond that the creative labour of the artist is of a special kind which enables one to continue to make abductive inferences and identify ‘art-like situations’; despite the depredations of the art market, works of art remain in a special category. Yet such a response would not dispense with the fact that, with the rise of the art market, creative labour has been increasingly mediated by dealers, critics and designated exhibition spaces – mediated, that is, by a series of institutions Gell is disinclined to discuss.6 In this respect, appealing to the special character of artistic production will not remove the difficulties confronting Gell’s theory.7 Moreover, the mediation of ‘art’ institutions has progressively reconfigured the character of creative labour. This brings me to the matter of Duchamp’s ‘individuality’.

Duchamp’s work was not merely conditioned by the institutions of the art world, for the artist acknowledged and responded to them in unique ways. In significant part this was a result of Duchamp’s point of entry to the art world. His early works, such as Young Man and Girl in Spring, were created at a moment when the friction between the academic establishment and a network of private dealers had fostered a range of avant-garde strategies. In France, the ‘official’ annual exhibition, the Salon des Artistes Français, had been rivalled by the creation of the Salon des Indépendants (1884) and the Société Nationale des Beaux Arts (1890). The authority of the academy was now weakened and the French art world diversified; in 1903 these developments were pushed further by the establishing of yet another annual exhibition, the Salon d’Automne. These large exhibitions were in turn supported by smaller salonnets. In 1911 the critic Louis Vauxcelles estimated that the major salons had seventeen thousand exhibits and the salonnets a further ten thousand; in this situation, it is easy to see that the market for contemporary art had become saturated.8 Now artists were increasingly obliged to experiment to attract attention and support. Self promotion became vital, yet in the midst of such large displays single works could fail to make an impact; in this situation a successful tactic was the development of a profile at the salons through the coordinated display of different artists working in related styles. Fauvism was thus launched at the Salon d’Automne of 1905 and Cubism at the Salon des Indépendants of 1911.

Once a group of artists had established some reputation by such means they could make the transition from the large salons to the private galleries. The most successful artists would now secure contracts with dealers, which often involved exclusive rights to an artist’s production.9 Yet such contracts shaped production in particular ways. Instead of producing a small number of works for salon submission, artists with contracts tended to work towards ‘one-man shows’ at their dealer’s gallery; thus different works by the same artist came to be viewed together. These viewing conditions encouraged both artist and dealer to consider works in relation to one another, and this tended to have the effect of entrenching an artist’s style. If an artist continued to innovate, the experimentation was now usually undertaken within the parameters of a recognized, individual style. From the point of view of the dealer, this combination of innovation and entrenchment was welcome; innovation maintained the interest of collectors and the entrenchment ensured the continuity and continued value of an individual style, which was what the dealer underwriting production was investing in.10 It was this situation which Duchamp acknowledged and, as it developed, his oeuvre assumed the status of an ironic commentary on the art market.

Duchamp’s Young Man and Girl in Spring was shown at the 1911 Salon d’Automne, within the milieu of salon Cubism. Yet he was to be made acutely aware of the role of exhibition strategies after Gleizes and Metzinger took exception to what they saw as the satirical intent of Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2, and objected to its inclusion in the Salon des Indépendants of 1912. This event seems to have been a significant factor in Duchamp’s ‘retirement’ from painting in that year.11 Yet if Duchamp now seemed to withdraw from the art market he retained an engagement with its mechanisms. He now turned his attention to the production of ‘readymades’, more or less mundane objects simply designated as works of art and signed by the artist. So if the Parisian art market encouraged the cultivation of individual styles, Duchamp took the process to an absurd conclusion by abandoning painting and painterly style whilst preserving the signature, the gesture traditionally used to complete a work and confirm the identity of a style.12 And if in one respect the signing of readymades seems to create diversity within the oeuvre, as any object can be signed and thereby appropriated, the same principle reduces everything to the same status; everything and anything is a potential work by Marcel Duchamp.13

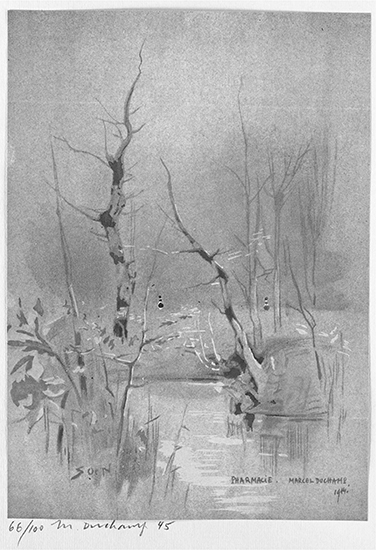

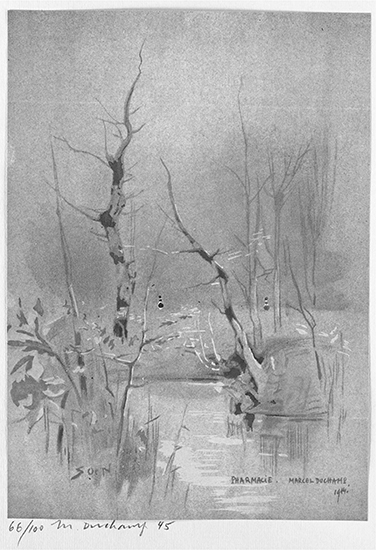

In Art and Agency Gell admits to an imagined interlocutor that the model of the oeuvre he has developed from Husserl seems of limited application and would not serve well for, say, the work of Canaletto. Rather, it ‘best applies to artists whose œuvre embodies a high degree of conscious self-reference’ (Gell 1998: 242). This is indeed the case for Duchamp but perhaps not quite in the way Gell imagined. Self-reference in Duchamp’s oeuvre may include the protention and retention of imagery but it is also a matter of those signs and gestures which constitute artistic identity in the marketplace, including of course the artist’s signature. Network of Stoppages may be a characteristic example of the superimposition of motifs but it is also distinctive in superimposing Duchamp’s own works. Many other forms of superimposition are easily found in the oeuvre; consider for example another important work of early 1914, Pharmacy, produced perhaps as little as a month before Network of Stoppages (Figure 5.1).

Pharmacy is amongst the artist’s earliest readymades, made by adding touches of colour to a commercial print of a winter landscape, along with a prominent new title and signature. The touches of red and yellow are placed so as to suggest two figures, perhaps about to encounter each other on a woodland path. Yet the title would direct a viewer with knowledge of French urban culture to a different interpretation, as the touches of colour could also suggest the bottles placed in the windows of French pharmacies. So, as with Network of Stoppages, there are (at least) three layers in Pharmacy. Yet in the readymade the layers are not all Duchamp’s; one belongs to the author of the original print, one belongs to Duchamp as the ‘producer’ of the readymade, and one arguably belongs to whichever pharmacist first thought to devise a window display with coloured bottles. If Pharmacy may be described as a network of stoppages, that network seems designed to extend beyond the artist. The very act of producing readymades demonstrates this; for each readymade is the appropriation of the work of another as much as it is the creation of ‘a new thought for the object’, even though Duchamp placed the emphasis on the latter part of the process when describing it in 1917 (Duchamp [1917] 1992: 248). As an appropriation, in which a new work is produced by mere designation, the readymade is simultaneously an exalting and undermining of the creative act. So if there is self-reference in Duchamp’s oeuvre it involves as much address to the cultural and institutional position of the artist as it does allusion to the artist’s other works.14 Duchamp would carry this process to a logical conclusion by the ironic institutionalization of his own work.

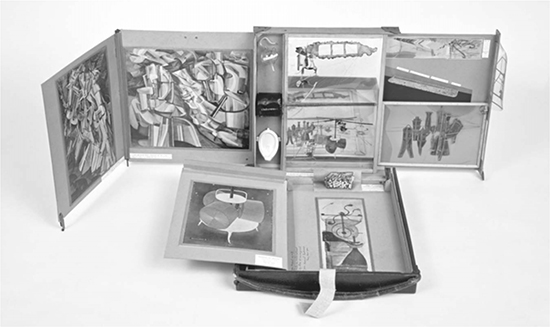

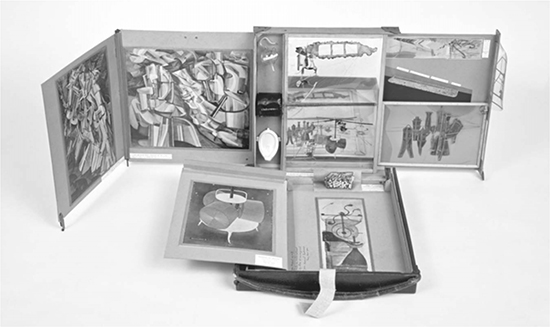

In 1940 a subscription bulletin announced the appearance of a ‘work’ which had occupied Duchamp since 1935. This was in fact a series of works, miniature colour reproductions and replicas of Duchamp’s own paintings and readymades, issued in cloth-covered boxes sometimes enclosed in leather valises, each example referred to as The Box in a Valise (Figure 5.2). This series itself went through a number of editions, with the final one assembled between 1955 and 1968. This latter series incorporated additional colour and black-and-white reproductions, including one of the Network of Stoppages. Of course, this significantly extended the protentional-retentional field of the 1914 work. Yet Gell does not refer to this modification of the oeuvre in his essay or in Art and Agency. And this despite the fact that The Box in a Valise is amply documented in Schwarz’s catalogue raisonné, the volume which Gell consulted in constructing his own model of the artist’s oeuvre (Schwarz 1969: 511–13). This is not a trivial point, for if The Box in a Valise does underline the coherence of the artist’s oeuvre by carrying self-reference to a new level, it does so in a manner which is problematic for Gell’s anthropological theory.

5.1 Marcel Duchamp, Pharmacy, from View, New York, magazine containing a rectified readymade after the original of 1914, various authors, 1945 (lithograph), Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images / The Bridgeman Art Library, © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2012.

5.2 Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise 1935–1941 (leather-covered case containing miniature replicas and photographs), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art/Photo © Scottish National Galleries, © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2012.

In an interview with James Johnson Sweeney, itself cited in Schwarz’s catalogue, Duchamp explained the genesis of his series:

here, again, a new form of expression was involved. Instead of painting something new, my aim was to reproduce the paintings and objects I liked and collect them in a space as small as possible. I did not know how to go about it. I first thought of a book, but I did not like the idea. Then it occurred to me that it could be a box in which all my works would be collected and mounted like in a small museum, a portable museum, so to speak. (Schwarz 1969: 513)

One could say that Duchamp had reached the ‘stage of life’ where he wanted to curate his own career and that The Box in a Valise was the result. This portable museum is evidently a caricature of an institution, given that it contains reproductions and not ‘original’ works, and indeed once fully unfolded it most closely resembles a salesman’s suitcase of samples. Nevertheless, The Box in a Valise does suggest a ‘depth of focus’ specific to the museum. In Duchamp’s move towards self-memorialization there is an attempt to move beyond ‘the context of the “life” ’, or at least to situate that context in a larger frame. Duchamp thereby made further acknowledgment of the institutional parameters of his work.15 Thus The Box in a Valise removes the artist from the anthropological realm as defined by Gell. In choosing to enshrine his oeuvre in his own museum, Duchamp assigned it to the sociology of art. This decision reveals not just the limits of Gell’s account of Duchamp, it also points towards the limits of his larger anthropological project.

At this juncture, it should be recalled that Gell began his essay on Duchamp by seeking to rebut the charge that anthropology ‘cannot handle change’. Gell’s own solution, as has been shown, was to develop a systematic model from the work of Husserl; for Gell, this simply ‘by-passes, or rather, leap-frogs over, the problem of historical explanation’. However, in the present context one is forced to ask how successful such acrobatics are. Arguably Gell arrived at a model for consciousness of change, which is hardly a model for change itself. Moreover, Gell developed this model with reference to an artist whose portable museum resists the anthropologist’s categorization. Consummate chess player that he was, Duchamp remains one move ahead. The artist consistently anticipated and checked those seeking to interpret his work and, given The Box in a Valise, this would seem to include Gell. The anthropologist perhaps recognized as much in viewing Duchamp’s oeuvre as a network; it is also a net in which he is caught. Given Gell’s delight in traps and trapping, it might not have concerned him too much to be in thrall to the artist. At least in this sense, he was perhaps content to be Duchamp’s Gell.

Notes

1. Unless otherwise indicated, quotations are from the essay by Gell published in this volume.

2. An assessment of Gell’s work from this perspective seems necessary in order to suggest why his theories have not had an impact on art history comparable to that visited on anthropology. So a reading of his essay, to adapt one of the author’s own phrases, has a certain art-historical relevance, quite apart from cultural interest. For cases where art historians have engaged with Gell’s work, see O’Malley (2005), Rampley (2005), Van Eck (2010) and the range of contributions in Osborne and Tanner (2007).

3. No one has done more than Mark Antliff to shed light on Bergson and thereby illuminate this question. See Antliff (1993). For further documentation, see Antliff and Leighten (2008).

4. To reach this conclusion Gell drew on Henderson (1983). His position is also supported by Henderson’s later and more detailed work on Duchamp (Henderson 1998).

5. This position is developed from Marx’s analysis of the production and circulation of commodities, yet in establishing the limits of social agency it raises issues which are directly relevant to the shape of Gell’s argument. Approaching these issues from another direction, Whitney Davis has pointed out that agency should not be limited ‘to the individuated personal identities of patrons, artists or viewers’ and that in principle agency is multiple and ramified (Davis 2007: 210). Yet Gell does not pursue this line of argument, for this account of agency moves analysis away from the domain Gell wishes to inhabit, that of ‘social relations in the vicinity of objects’.

6. This is the bare outline of a long and complicated history. The institutions of the modern ‘art world’ were established in the eighteenth century in Paris with the emergence of regular exhibitions, the ‘salons’, from 1737. These created a new public for art and, in turn, new types of professional and commercial activity in the form of art criticism and art dealing; see Crow (1985) and Wrigley (1993). To argue that certain works of art are commodities and thus do not mediate social agency does not oblige one to level art production with other forms of production. Yet it does seem to require an account of art production which relies less on ‘abductive inference’ than on ‘inferential criticism’. For the definition and practice of such criticism, see Baxandall (1985).

7. It should be noted that, with the exception of Duchamp, Gell avoided the problem of institutions by largely avoiding works of art made under the conditions of developed commodity production, that is, the majority of work produced in the West in the last two hundred years. When Gell does discuss such work he tends to concentrate on examples such as Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington where some interaction of minds can be sustained. He acknowledges that he is principally interested in examples of ‘limited circulation’ (Gell 1998: 8).

8. The figures are given in Cottington (1998: 42). This work offers an excellent history of the developments summarized here.

9. For examples of such contracts, see Appendix E of Gee (1981: 10–18).

10. It should be emphasiszed that the use of contracts by dealers such as Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler differed from earlier models of patronage, such as that of Ambroise Vollard, who tended to buy the contents of a studio rather than offer continued support. Kahnweiler’s contracts with Picasso and Braque formed part of the matrix for the development of their Cubism. For the impact of new patterns of dealing, see Cottington (1998).

11. For a cogent summary of Duchamp’s point of entry to this market and his perspective on it, see Cottington (2004: 155–61).

12. Jeffrey Weiss has argued that the ‘commercialism, mediocrity and glut’ of the Parisian art market were crucial factors in the conception of the readymades, and even claims: ‘before it is anything else, the readymade is Duchamp’s answer to overproduction and avantgardism’ (Weiss 1994: 116, 125).

13. John Cage recognized this relationship. ‘The check. The string he dropped. The Mona Lisa. The musical notes taken out of a hat. The glass. The toy shotgun painting. The things he found. Therefore, everything seen – every object, that is, plus the process of looking at it – is a Duchamp’ (Cage [1964] 1973: 188).

14. Davis also makes the point that Duchamp’s oeuvre should be considered as displaying ramified agency rather than being the product of one agent (Davis 2007: 209).

15. The Box in a Valise is the point of departure for Dalia Judovitz’s book-length study of Duchamp (1995). This work develops a number of the arguments concerning institutionalization sketched here.

References

Antliff, M. 1993. Inventing Bergson: Cultural Politics and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

———. and P. Leighten (eds). 2008. A Cubism Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914, trans. J.M. Todd et al. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baxandall, M. 1974. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 1985. Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Cage, J. (1964) 1973. ‘26 Statements re Duchamp’, in Art and Literature, reprinted in A. D’Harnoncourt and K. McShine (eds), Marcel Duchamp. New York: Museum of Modern Art, pp. 188–89.

Cottington, D. 1998. Cubism in the Shadow of War: The Avant-Garde and Politics in Paris 1905–1914. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

———. 2004. Cubism and its Histories. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

Crow, T.E. 1985. Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Davis, W. 2007. ‘Abducting the Agency of Art’, in R. Osborne and J. Tanner (eds), Art’s Agency and Art History. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell, pp. 199–219.

Duchamp, M. (1917) 1992. ‘The Richard Mutt Case’, in The Blind Man, reprinted in C. Harrison and P. Wood (eds), Art in Theory 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, p. 248.

Gee, M. 1981. Dealers, Critics and Collectors of Modern Painting: Aspects of the Parisian Art Market between 1910 and 1930. New York: Garland.

Gell, A. 1992. The Anthropology of Time: Cultural Constructions of Temporal Maps and Images. Oxford: Berg.

———. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Henderson, L.D. 1983. The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

———. 1998. Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Juodovitz, D. 1995. Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit. Berkeley and London: University of California Press.

Marx, K. 1990. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1, trans. B. Fowkes. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

O’Malley, M. 2005. ‘Altarpieces and Agency: The Altarpiece of the Society of the Purification and its “Invisible Skein of Relations” ’, Art History 28(4): 417–41.

Osborne, R. and J. Tanner (eds). 2007. Art’s Agency and Art History. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Podro, M. 1982. The Critical Historians of Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Rampley, M. 2005. ‘Art History and Cultural Difference: Alfred Gell’s Anthropology of Art’, Art History 28(4): 524–51.

Schwarz, A. 1969. The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. London: Thames and Hudson.

Van Eck, C. 2010. ‘Living Statues: Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency, Living Presence Response and the Sublime’, Art History 33(4): 643–59.

Weiss, J. 1994. The Popular Culture of Modern Art: Picasso, Duchamp, and Avant-Gardism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Wrigley, R. 1993. The Origins of French Art Criticism: From the Ancien Régime to the Restoration. Oxford: Clarendon Press.